1. Introduction

Northern regions of the planet, including Norway, Finland, northern provinces of Canada, the state of Alaska, and northern regions of Russia, such as Yakutia, Chukotka, etc., are a promising market for electric vehicle manufacturers [

1]. However, promotion of electric vehicles in the markets of the northern regions is currently constrained by a number of factors, including reduction of reliability and safety of EV operation in conditions of low atmospheric temperatures, including extremely low temperatures (down to -45°C) [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Such temperatures are common in these northern regions during the winter season, and winter in the northern regions lasts longer than in other regions of the world and often lasts 5-7 months a year.

The average temperature in the northern regions during the winter season is usually -20...-30 degrees Celsius. At such temperatures the electric vehicle elements experience special stresses that can lead to accelerated malfunctions [

6]. The elements most sensitive to low temperatures are those made of rubber and plastic, the physical properties of which undergo significant changes at low temperatures: they lose their plasticity, become more brittle and unstable to loads. This results in an increase in the number of failures in the on-board electronics of the electric vehicle. Energy consumption of the electric car battery increases both for maintaining the necessary temperature in the battery itself and for heating the EV cab, which leads to accelerated battery discharge and reduction of the total drive range of the electric car. At the same time, the impact of low atmospheric temperatures on electric vehicle components can be further exacerbated by strong winds, which are not uncommon in these latitudes.

Currently, the percentage of EVs in the total number of cars sold in the northern regions differs significantly from the number of EVs sold in regions with temperate and warm climates (

Table 1) [

7]. Data relative to 2023 are compared using two northern regions and two regions with temperate and warm climates located in the Russian Federation.

According to a survey of individual car owners and professional drivers of cab services conducted in the northern regions, four main factors deterring the main potential users from buying and using electric cars were identified (

Table 2).

As is seen from the survey results (

Table 2), two of the five factors relate to EV safety. At the same time, the factor of EV safety in intercity travel in the winter season is specific to the northern regions.

These regions have low territorial population densities, which means that settlements are often located dozens or hundreds of kilometers away from each other. Traffic on the roads between such settlements is very low, again due to the low population density and the small number of businesses in the region. Thus, it is common for only one car to pass along the road in several hours, and in bad weather traffic stops altogether. On such road sections, the emergency stop of an electric vehicle in winter (e.g. in the event of a road accident, electric vehicle breakdown or battery discharge), followed by cessation of heat generation by the regular cabin heater, can lead to frostbite and death of people in the EV cabin from the effects of low atmospheric temperatures. Such an outcome is possible if help for their evacuation does not arrive in time, which is quite likely due to the remoteness of the nearest settlements and sparse traffic. Often in such regions there are heavy snowfalls with blizzards, which may also force the driver to stop the electric car and wait for help, for example, rescue teams or car service. Walking to the nearest settlement is again made impossible by the low atmospheric temperature, at which a person without special protective gear will get critical frostbite after only a few kilometers of travel.

Nowadays, some experienced motorists, take portable autonomous heaters running on gasoline or diesel fuel before driving through such dangerous areas [

8]. But the use of such heaters, in turn, also creates risks for safety, because during their operation they emit carbon monoxide, which can be toxic if the proper venting of exhaust gases into the atmosphere from the cabin is not organized. Moreover, the fuel on which such heaters operate is a flammable substance, and handling it requires special care, otherwise a fire may occur. Often such a portable heater is switched on by drivers in addition to the regular heater of the electric vehicle cabin because the regular heaters do not provide sufficient heat generation, as they are often not designed to heat the EV cabin in conditions when atmospheric temperatures reach -20°С...-45°С.

Various aspects of the theory of ensuring thermal comfort for the driver and passengers in vehicles, including electric vehicles, were previously addressed in works [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], they made a significant contribution to the development of models of thermal comfort in a vehicle, but they did not address the problem of reserving a heat source for the cabins of electric vehicles in case it is not possible to use the standard heating system.

The purpose of this work is to suggest a method of providing additional or alternative heat to the cabin of an electric car, operated in the northern regions of the planet at extremely low atmospheric temperatures (up to -45°C), based on the use of a safe energy source - electricity.

2. Materials and Methods

To solve the problem of providing heat to the cabin of an electric vehicle operated at extremely low outdoor temperatures (down to -45°C), we have developed a backup cabin heater powered by electric energy. Taking into account that connection of the backup heater to the regular battery of the electric vehicle will accelerate the discharge of this battery and reduce the range of the EV [

26,

27,

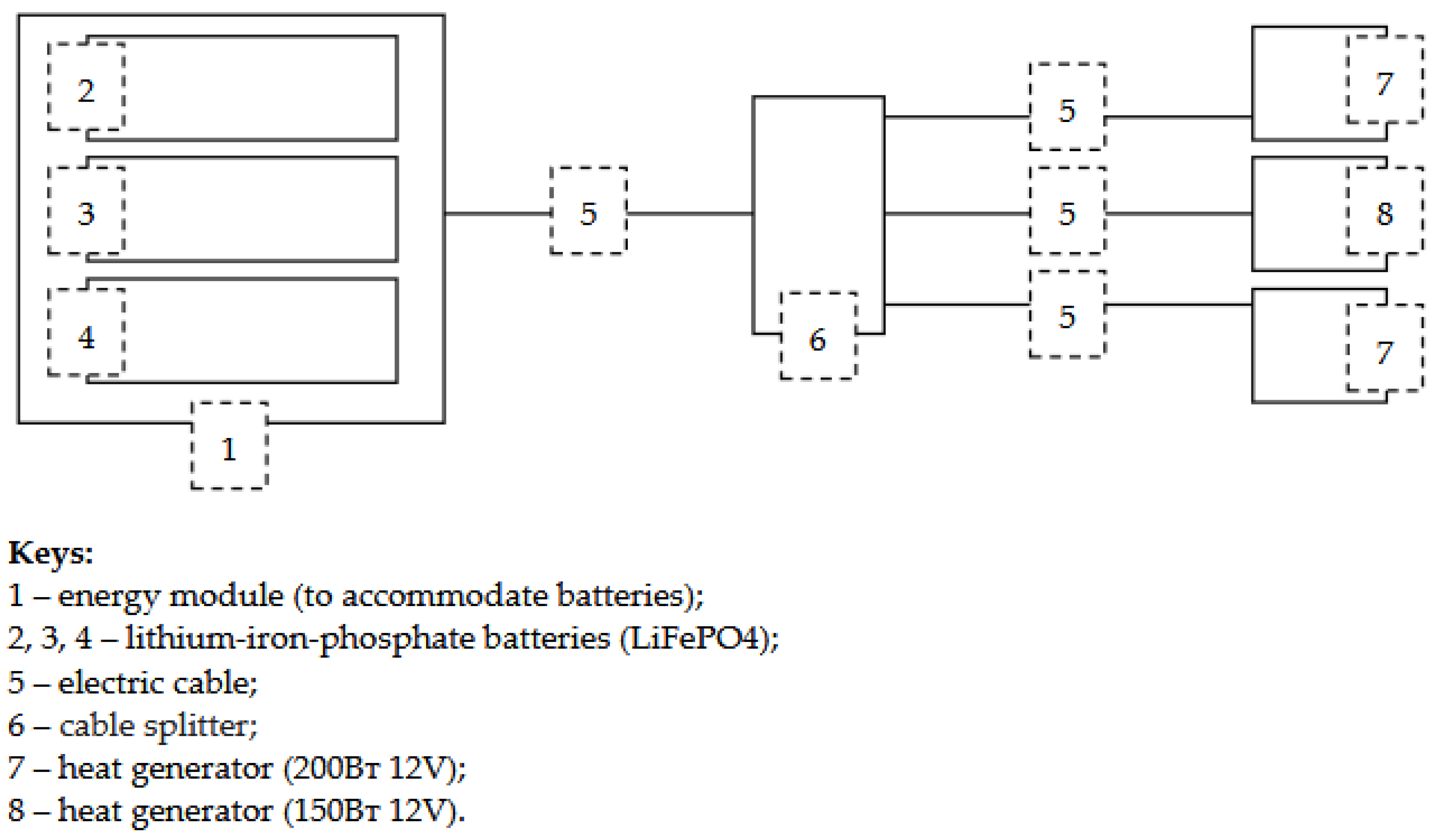

28], we have chosen the option of connecting the backup heater not to the regular battery, but to an independent source of electrical energy. The structure of the backup heater included an energy module containing 3 lithium-iron-phosphate batteries (LiFePO4) with a capacity of 100 Ah each. The total capacity of the module was 300 Ah. Lithium-iron-phosphate batteries were chosen for a number of reasons: non-flammability, durability (service life is >2000 operating cycles), and frost resistance (batteries operate stably at temperatures from -45°C to +45°C).

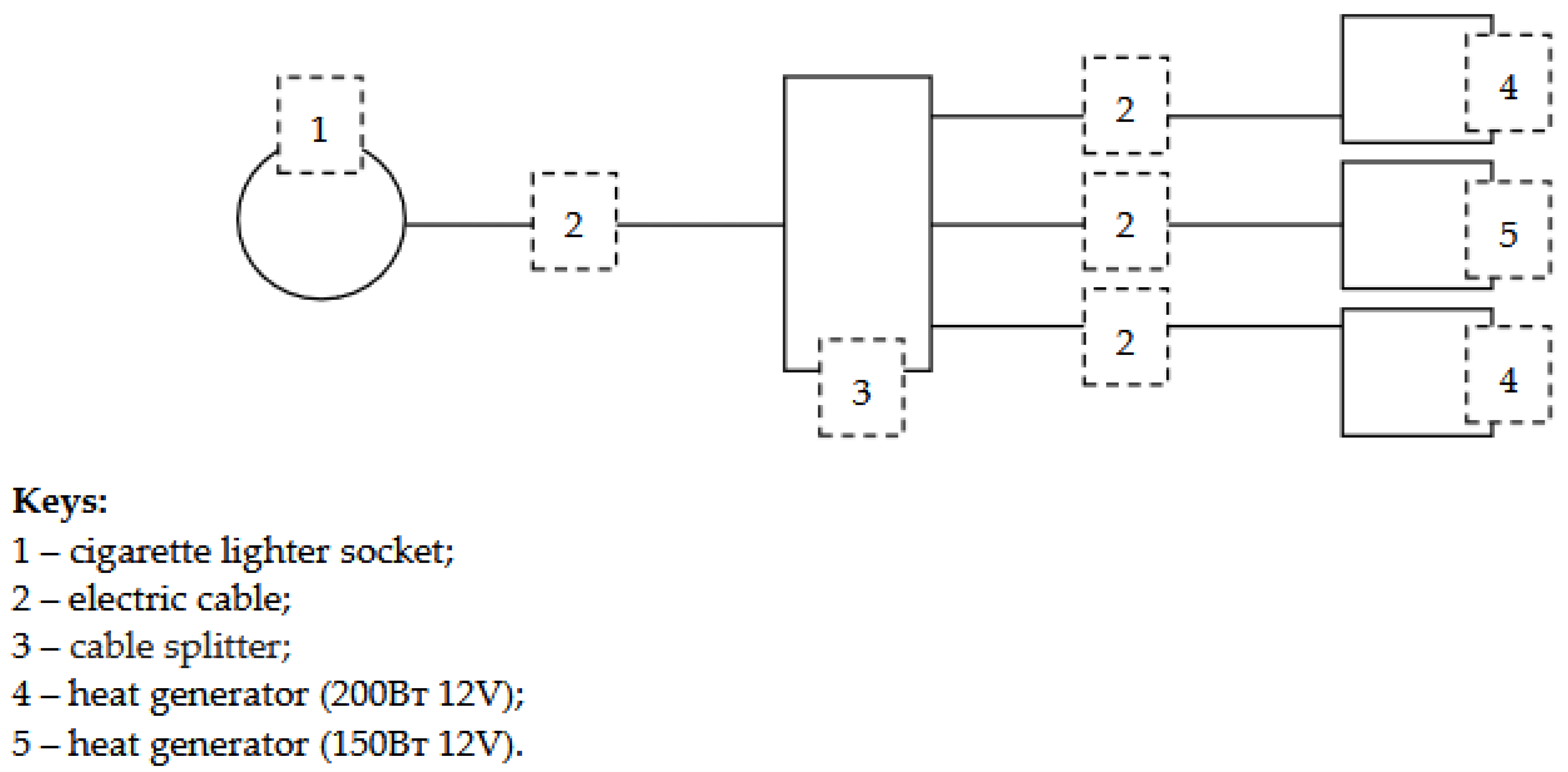

Heat sources in the structure of the backup heater are 3 heat generators: 2 with a capacity of 200W and 1 with a capacity of 150W, operating from a 12V power supply. The principle of operation of the heat generators is as follows: air is heated by electric heating elements, which blow out heated air with the help of built-in fans. Locations for generators in the cabin were chosen based on the analysis of the coldest and most problematic zones, from the point of view of heating in the cabin of an electric car. One zone is the area around the driver's and front passenger's feet, and the second zone is the windshield area. The windshield is particularly susceptible to frosting on the inside due to the constant exposure of the windshield to external low atmospheric temperatures. Frosting-up on the inside of the windshield reduces the driver's visibility significantly and often makes driving an electric vehicle impossible.

As a result, the structure of the developed electric vehicle cabin backup heater included 8 elements (

Figure 1).

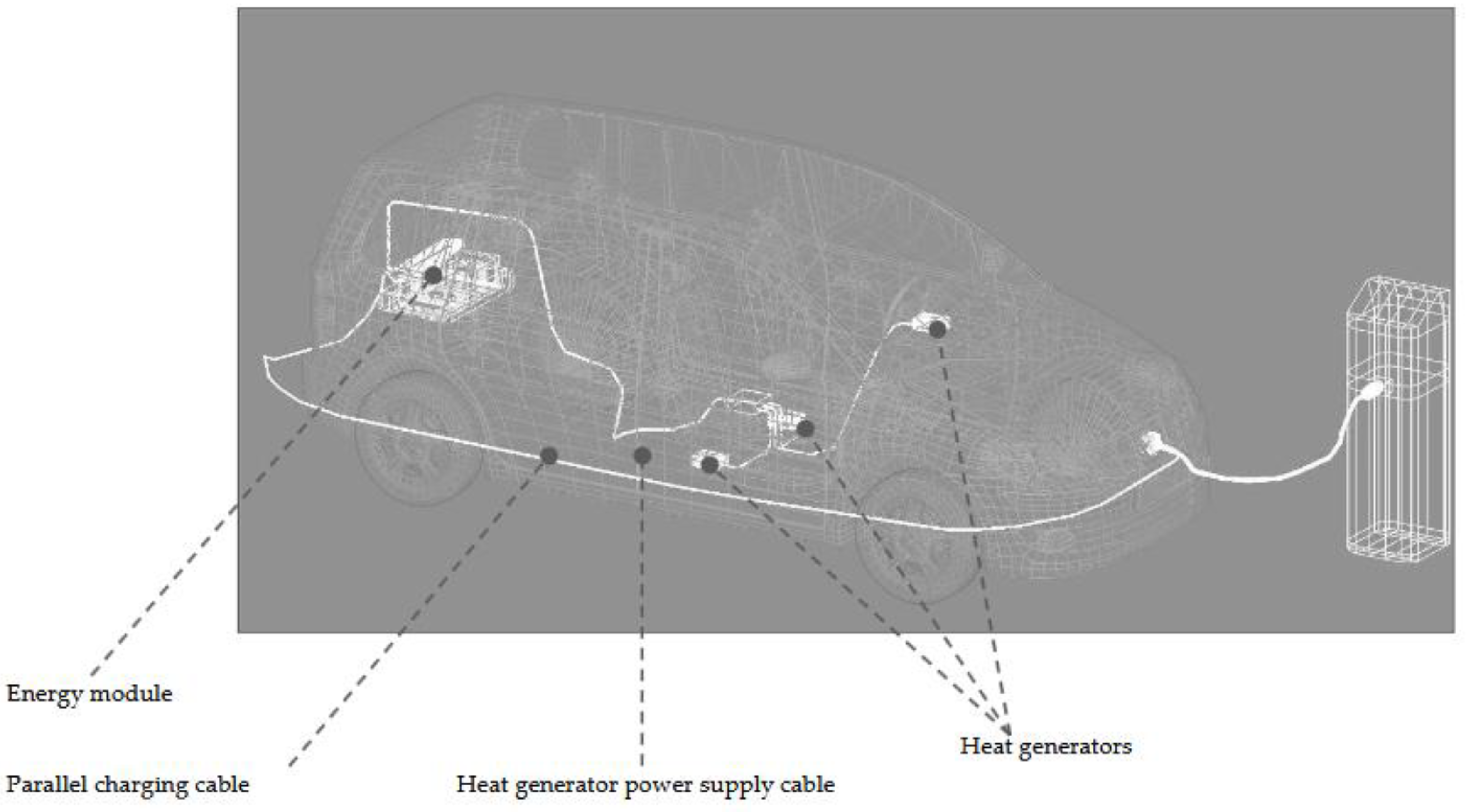

Recharging of batteries located in the energy module can be carried out both from the stationary 220V power supply network and simultaneously with charging of the electric vehicle from the stationary charging station. For this purpose the parallel charging cable is provided in the structure of the backup heater (

Figure 2). Starting the backup heater is carried out by the driver by pressing the starting toggle switches located on the heat generators. The following scheme of arrangement of backup heater elements in an EV is proposed (

Figure 2).

In order to evaluate the extent to which the backup heater solves the specified problem of providing heat to the cabin of an electric vehicle operated at extremely low street temperatures (down to -45°C), the method of field experiment was chosen. The field experiment should provide data on: a) the duration of the backup heater operation; b) the temperature level in the electric vehicle cabin achieved by heat generation by the autonomous heater; c) the dynamics of the temperature drop in the EV cabin to a critically low level of 0°C (after the heat generation source is turned off). The data should be obtained at three ranges of atmospheric temperatures: -20°C to -25°C, -30°C to -35°C, -40° to -45°C.

The experimental application of the backup heater was performed on two electric cars - No. 1 and No. 2 (Nissan Leaf brand). The experiment was conducted at the test site of the North-Eastern Federal University (Yakutsk, Russian Federation), in winter, at three ranges of atmospheric temperatures:

-20°C…-25°С;

-30°C…-35°С;

-40°С…-45°С.

At the first stage of the experiment, the dynamics of the temperature level drop in the electric car cabin after the regular heater is turned off was measured. The measurements were carried out simultaneously on electric cars No. 1 and No. 2, which were in the mode - P. These measurements allow us to obtain information about how much time passes from the moment when the regular heater is switched off to the moment when the air temperature in the EV cabin drops to a critically low level (-0°C), after which it is necessary to have a working source of thermal energy in the cabin to protect people from hypothermia.

At the second stage of the experiment, we made three measurements of the backup heater operation duration at the same three ranges of atmospheric temperatures: -20°C...-25°C, -30°C...-35°C, -40°C...-45°C. Measurements were carried out simultaneously on electric cars No. 1 and No. 2. During the measurement, the electric vehicles were stationary with the regular heater switched off. Before switching on the backup heater, the air temperature in the cabs of electric vehicles was within the range of +10°C to -14°C. Such measurements make it possible to obtain data on the duration of the backup heater operation at different atmospheric temperatures.

In parallel, at the 2nd stage, the air temperature was measured in different points of the electric car cabin to assess the capability of the heater to maintain a sufficient temperature level. Measurements were made in 12 points: points 1-4 - the front part of the headrests of the driver and passengers; points 5-8 - the seat of the driver and passengers in the area of the human pelvis; points 9-12 - in the area of the shins of the driver and passengers, the location of points, clockwise, starting from the driver. Temperature was measured after 30 minutes of uninterrupted operation of the backup heater.

In addition, at stages 1 and 2, wind speed and air humidity were measured in parallel with the main measurements in order to assess the general climatic conditions during the experiment.

To complement the experimentation, a mathematical method can also be used to calculate the operating time of the backup heater at other levels of atmospheric temperatures. For example, when the heat generators and batteries are connected in parallel, their power and capacity are respectively added up, thus obtaining P = 200 + 200 + 200 + 150 = 550 W and C = 100 + 100 + 100 + 100 = 300 a/h. Let us use the formula (1) to find the battery capacity at the temperature of 15°C:

Where: Cf is the value of the capacity of the set discharge mode at the battery temperature at the end of discharge other than t = +20°C;

te is the temperature of the battery electrolyte;

α is the temperature coefficient;

Ce is the actual capacity of the battery at a temperature other than t = +20°C.

After all calculations we have a battery capacity of 273 a/h. Using the formula:

we obtain the result that the backup heater at the air temperature in the place of installation of the power module in the EV cabin of 15°С, will operate for 5.9 hours.

3. Results

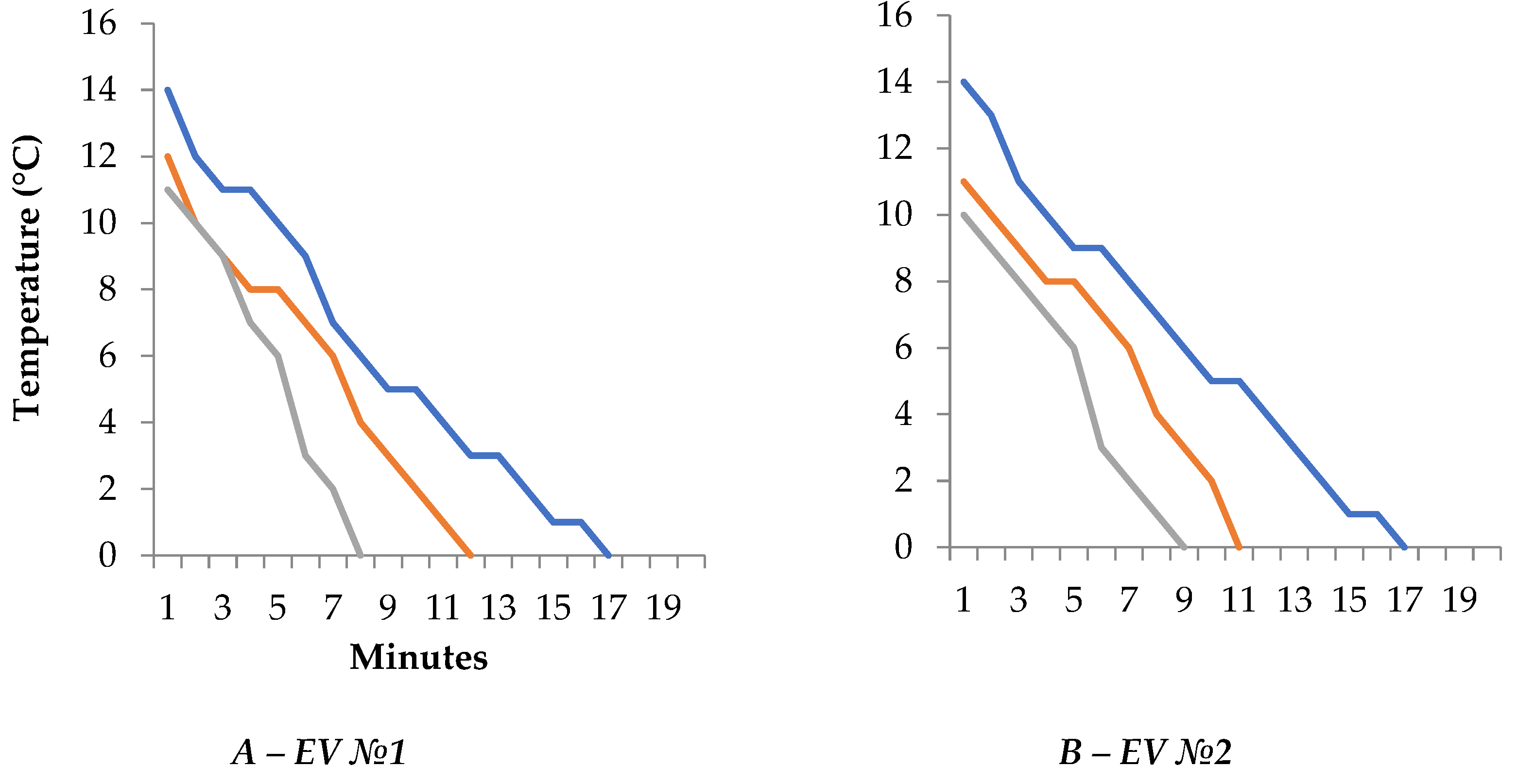

The results of measuring the dynamics of temperature level drop in the cabin of electric cars No. 1 No. 2, after turning off the regular cabin heater, obtained at the first stage of the experiment, are shown in

Figure 3.

Figure 3 shows that the critically low air temperature level (-0°C) in the EV cabin is reached within a time range of 7-17 min (depending on the ambient air temperature), after which the EV cabin needs to resume operation of the thermal energy source to protect people from hypothermia.

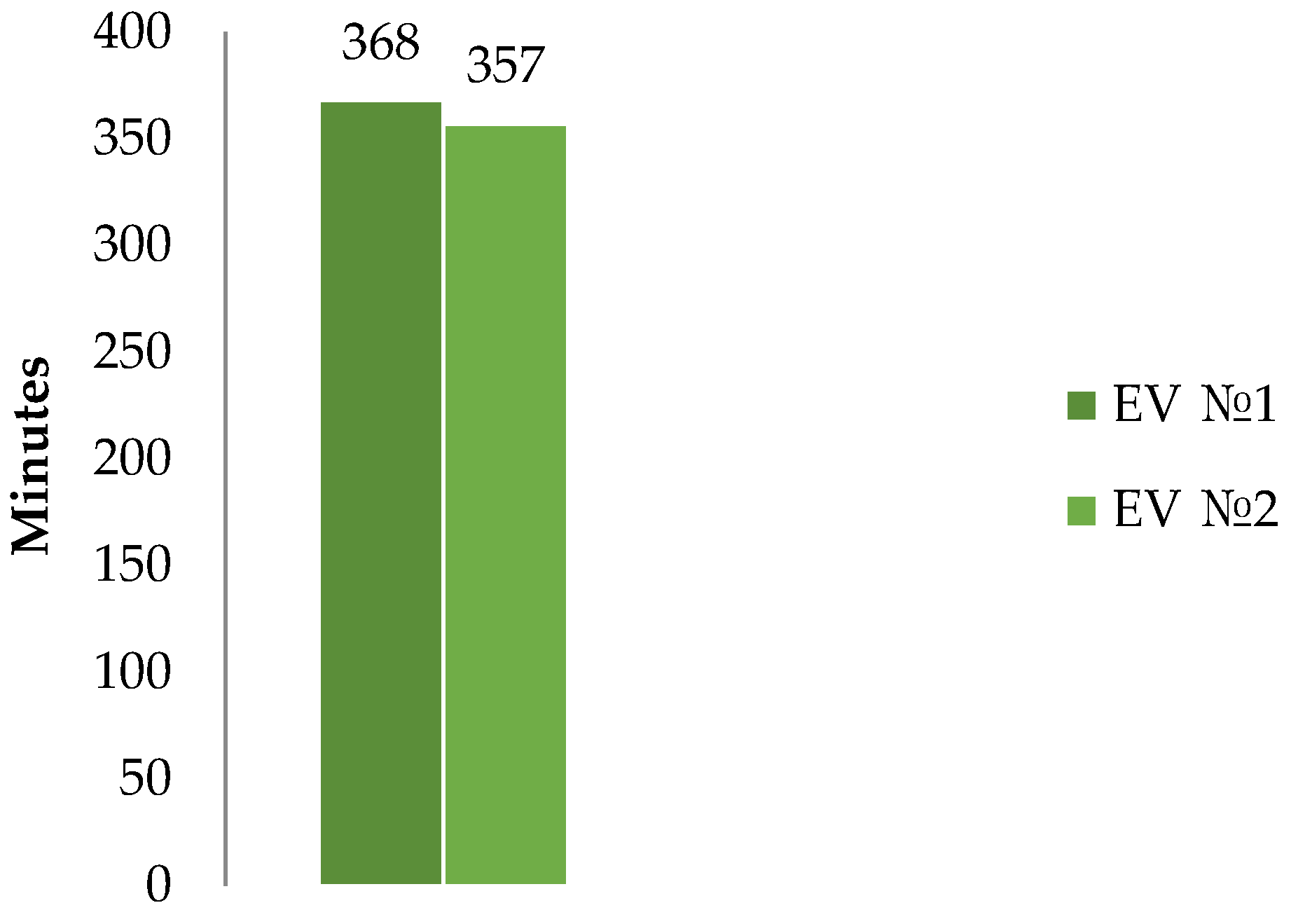

The results of measuring the duration of the backup cabin heater operation obtained at the second stage of the experiment (at atmospheric air temperature of -20°C...-25°C, wind speed of 1-5 m/s and air humidity of 73.9%) are shown in

Figure 4.

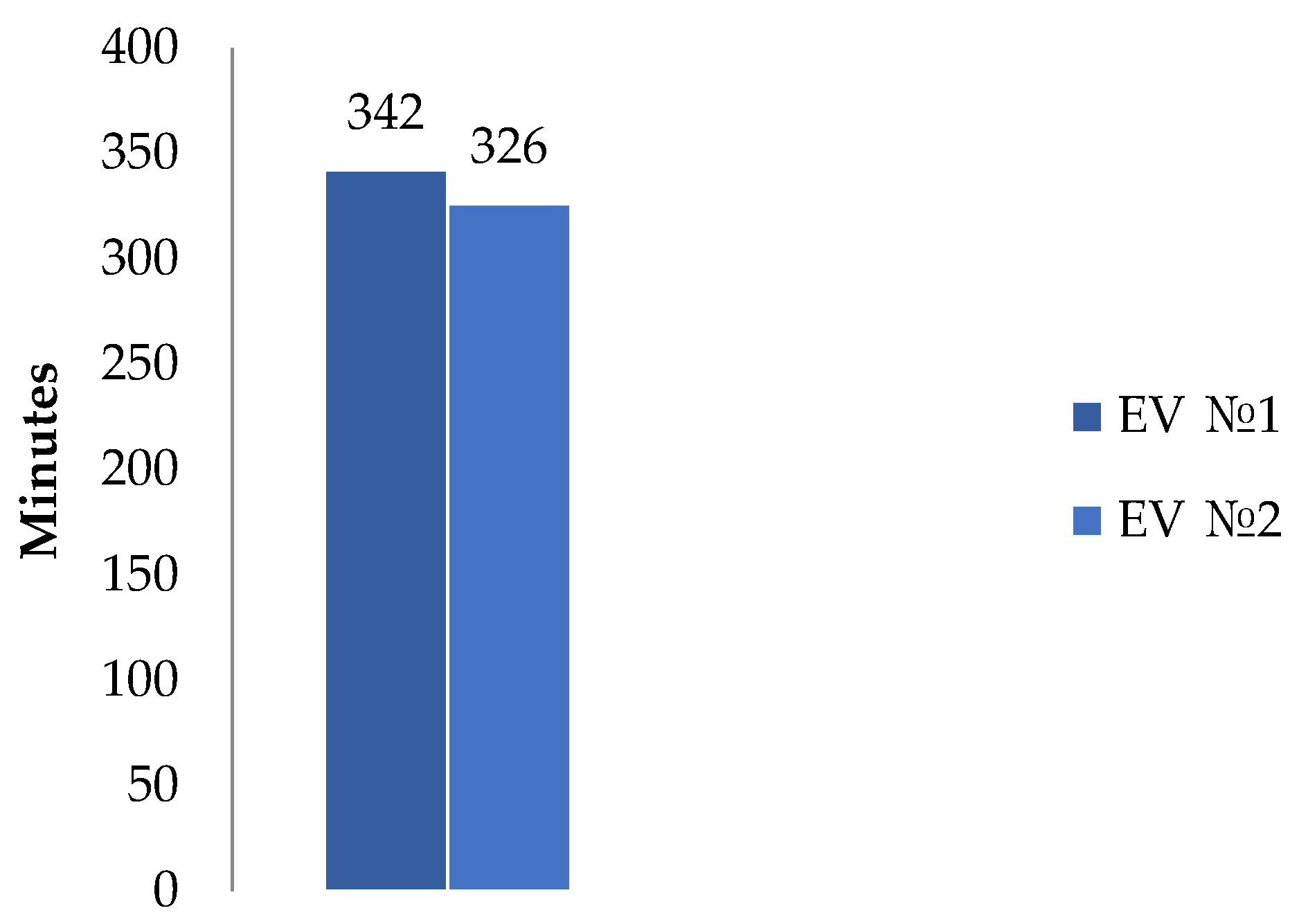

The results of measuring the duration of the backup heater operation, at the atmospheric air temperature of -30°C...-35°C, wind speed of 1-5 m/s and air humidity of 75.2% are shown in

Figure 5.

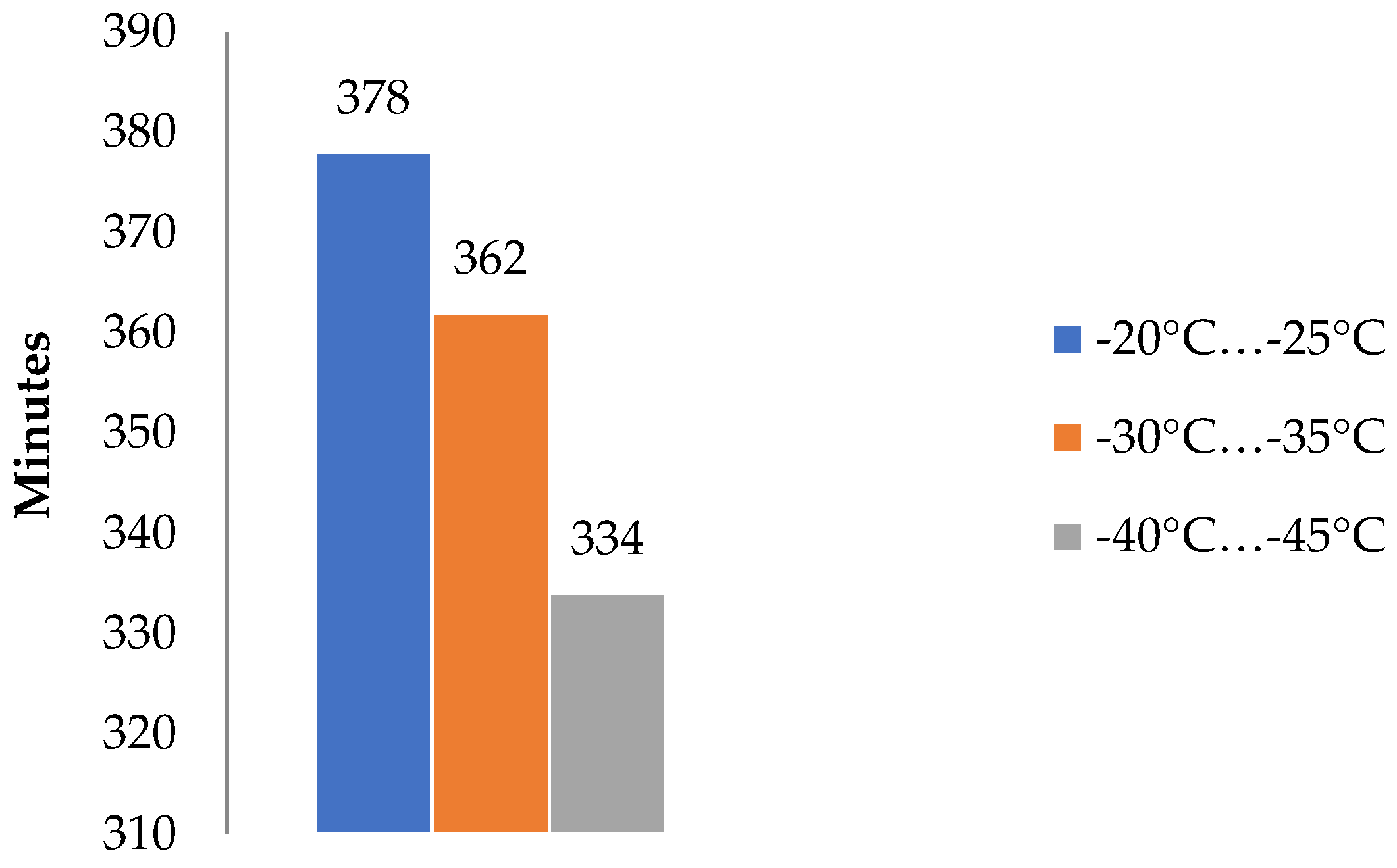

The results of measuring the duration of the backup heater operation, at the atmospheric air temperature of -40°C...-45°C, wind speed of 1-5 m/s and air humidity of 71.6%, are shown in

Figure 6.

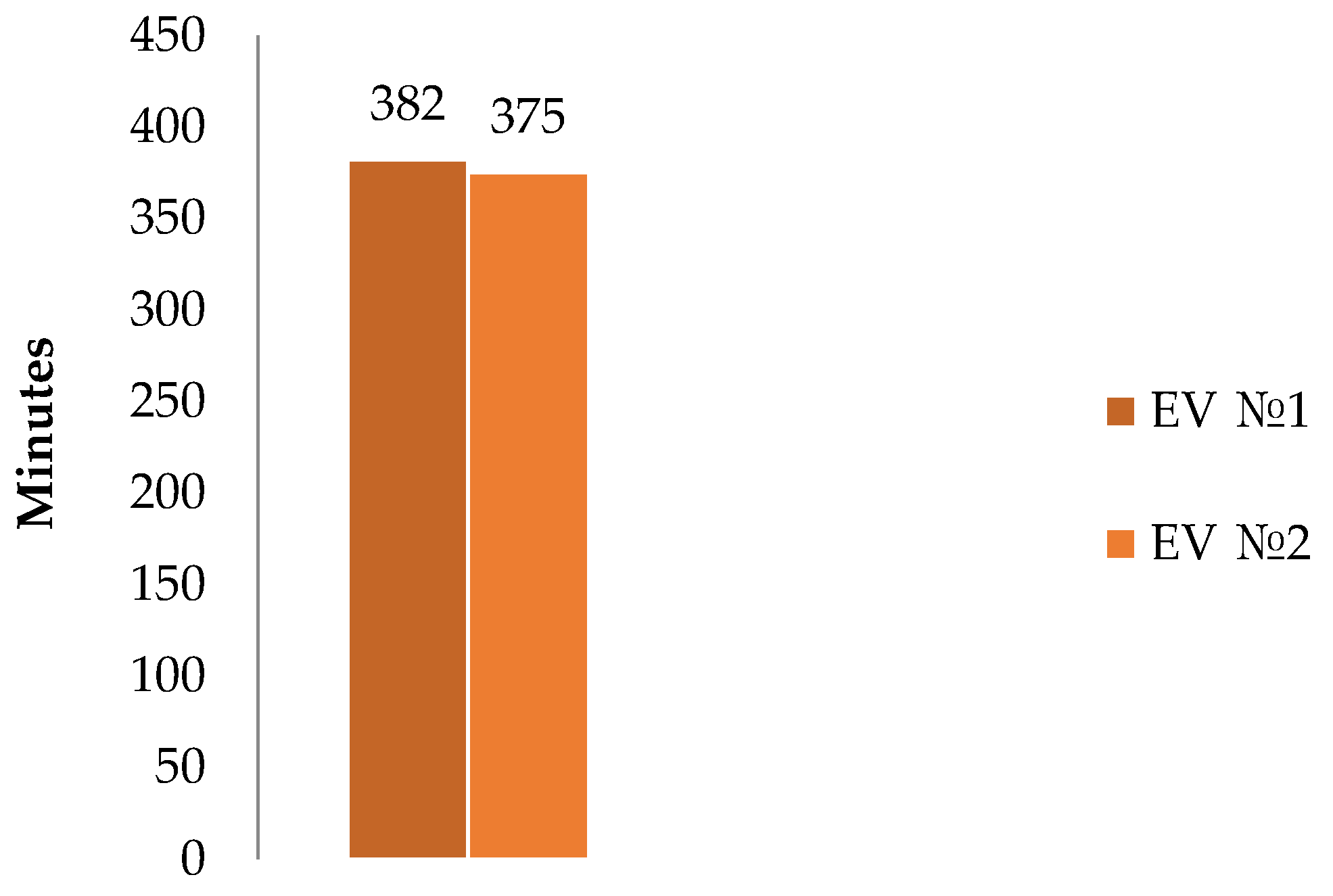

The median operating time of the backup heater at various atmospheric temperatures is shown in

Figure 7.

The results of the second stage of parallel measurement of air temperature at different points in the electric vehicle cabin are presented in

Table 3. The data in

Table 3 includes median values for EV 1 and EV 2. The temperature measurement was started after 30 minutes of continuous operation of the backup heater. Measurements were taken at 12 points: points 1-4 were the front of the driver and passenger head restraints, points 5-8 were the driver and passenger seats around the human pelvis, and points 9-12 were the driver and passenger shins (point locations, clockwise, starting with the driver).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper proposes a method of providing heat to the cabin of an electric vehicle operated in the northern regions of the planet at extremely low atmospheric temperatures (down to -45°C). The method is based on generation of heat by a backup cabin heater. The heater allows the solution of one of the main problems of traffic safety in northern regions - it is the emergency stopping of an electric car on a road section, remote from populated areas, in conditions of low atmospheric temperatures, with the subsequent stoppage of the regular cabin heater, which threatens EV passengers with critical frostbite. As shown by our measurements, the temperature in the cabin of an electric vehicle after switching off the regular heater drops to critically low values (-0°C) in 18 minutes at atmospheric temperatures of -20°C...-25°C, in 12-13 minutes at -30°C...-35°C, and in 9-10 minutes at -40°C...-45°C. After that, the low air temperature leads to hypothermia of people in the EV cabin. The use of an emergency heater will provide the EV passengers with warmth while waiting for help. Under standard weather conditions, the time of arrival of help from a nearby settlement is 60-180 min, and it was experimentally established (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5) that the operation time of the heater is 334-378 minutes depending on the atmospheric air temperature.

The second task that can be solved by the developed backup heater is to maintain a comfortable temperature in the cabin of an electric vehicle when the heat generated by the regular cabin heater is insufficient. In most modern EVs, the heat generated by the regular heater is insufficient at atmospheric temperatures below -25°С. In such conditions, both regular and backup heaters can be used in parallel.

The third task solved by the backup heater is to increase the electric vehicle's drive range, which is realized on the basis of saving the charge of the EV's regular battery. This saving is achieved by using not the regular heater (which is a significant energy consumer of the electric vehicle's regular battery) to heat the EV cabin, but by switching this function to the backup heater.

The structure of the backup heater considered in this paper provides for the use of three batteries and three heat generators in a 3x3 scheme. This structure is designed for an electric car of sedan class. But the structure of the heater is dynamic and can be extended, for example, the structure can be increased to 5X5, in case of using the backup heater on electric vehicles with a larger cabin - vans or off-road vehicles.

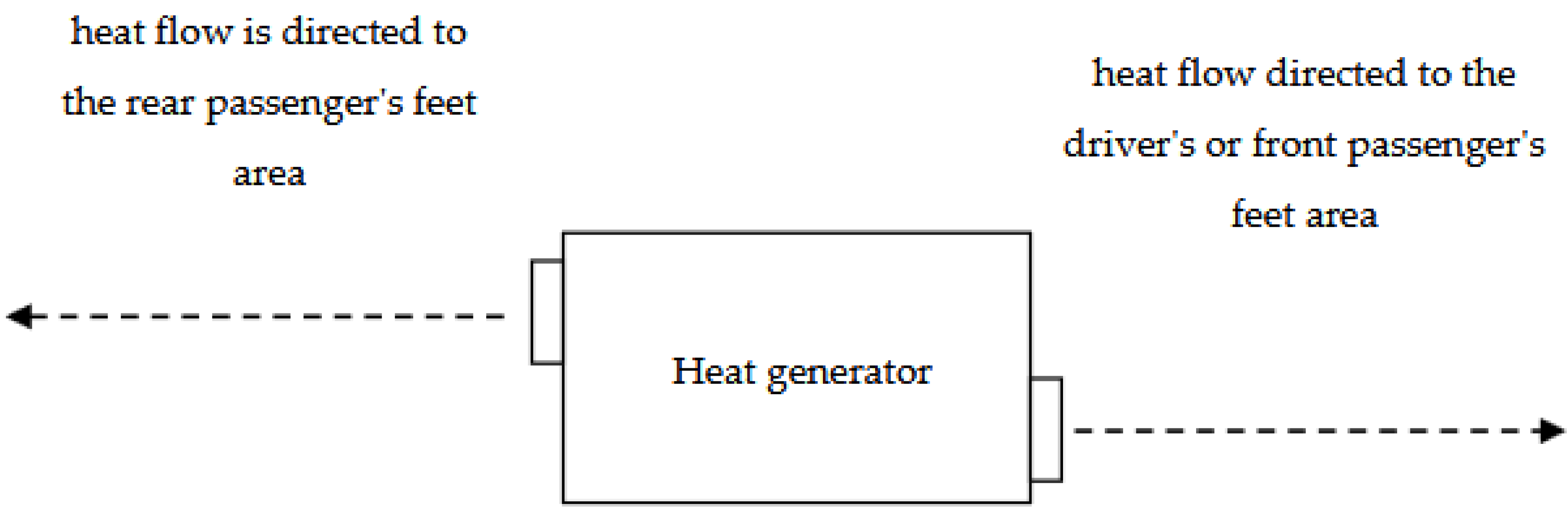

As can be seen from the results of temperature measurements in different points of the EV cabin (

Table 3), the lack of heat when the backup heater is operating is observed in the area of the rear passengers' feet. This problem can be solved by modifying the design of the 200W heat generators. The heat generators have two nozzles each for the heat flow. It would be optimal to change the design to a multi-directional design, so that one heat flow is directed to the driver's or front passenger's feet area and the second heat flow is directed to the rear passenger's feet area (

Figure 8).

The back-up heater is mobile and can be freely moved from one electric vehicle to another. For example, it can be used by different drivers on a “take-away” basis, where the driver takes the heater from a “Rescue Container” installed at the beginning of a dangerous section and returns the heater to a similar container at the end of the dangerous section of road. The rescue services fill the “Rescue container” with food, equipment, etc., i.e. with everything that drivers can take with them before driving along a dangerous road section and that will help them survive in case of a forced stop, including in difficult weather conditions, at extremely low atmospheric temperatures, until help arrives. Rescue containers are becoming increasingly common on road sections in northern regions, where distances between settlements are 30 km or more. Such road sections are subject to heavy snowfalls, blizzards and ice, which can force drivers to stop on the road. Often such roads are in forest or mountainous areas, which can also delay the arrival of rescuers to the stopped vehicles. There is very little car traffic on such sections, and this creates the risk that a broken-down car will not receive help from other drivers traveling on the same road. After passing a dangerous section of road, drivers return the equipment they have taken to the same “rescue container” located at the other end of the road section.

The use of a back-up heater does not involve any modifications to the electric vehicle, which is important to maintain the validity of the manufacturer's warranty and insurance.

In the event that a malfunctioning electric vehicle (with a non-operating heater) is stopped on the road with the regular battery still charged, this charge can also be used to operate the backup heater. The backup heater can be connected to the EV battery via the cigarette lighter socket (

Figure 9). This will increase the amount of time the people in the EV cabin can receive the heat generated by the backup heater.

Equipping an electric vehicle with a backup heater, proposed in this paper, will increase the time during which people can stay in a malfunctioning EV or one blocked by snowfall at below zero temperature waiting for help by 5-7 hours (depending on the atmospheric temperature), when using the battery energy of the backup heater, and for a longer time, when further connecting the heater to the regular battery EV according to the scheme shown in

Figure 9.

A promising direction for the continuation of this work is the development of an electronic unit to control the power of the generated heat flow in order to maintain an optimal level of air temperature in the EV cabin, which will reduce energy consumption and increase the operating time of the backup heater.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, and supervision AVS Authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study is available permitted on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Global EV Outlook 2020—Analysis—IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2020 (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Cvok, I.; Ratković, I.; Deur, J. Multi-Objective Optimisation-Based Design of an Electric Vehicle Cabin Heating Control System for Improved Thermal Comfort and Driving Range. Energies 2021, 14, 1203. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B., Lian, Y., Xu, L., Deng, Z., Zhao, F., Zhang, H., & Liu, S. (2024). State-of-the-art thermal comfort models for car cabin Environment. Building and Environment, 262, 111825. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Gao, C.; Gao, Q.; Wang, G.; Liu, M.H.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, C.; Yan, Y.Y. Status and development of electric vehicle integrated thermal management from BTM to HVAC. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 88, 398–409. [CrossRef]

- Paffumi, E.; Otura, M.; Centurelli, M.; Casellas, R.; Brenner, A.; Jahn, S. Energy consumption, driving range and cabin tem-perature performances at different ambient conditions in support to the design of a user-centric efficient electric vehicle: The QUIET Project. In Proceedings of the 14th SDEWES Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 1–6 October 2019; p. 18.

- Shvetsov, A.V. Change in Fuel Consumption of a Hybrid Vehicle When Operating in the Far North. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 104. [CrossRef]

- Car Sales Database. Available online: https://www.drom.ru/ (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- Karjalainen, P.; Nikka, M.; Olin, M.; Martikainen, S.; Rostedt, A.; Arffman, A.; Mikkonen, S. Fuel-Operated Auxiliary Heaters Are a Major Additional Source of Vehicular Particulate Emissions in Cold Regions. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanparvar, K.; Al Faruque, M.A. Battery lifetime-aware automotive climate control for electric vehicles. In Proceedings of the 52nd ACM/EDAC/IEEE Design Automation Conference (DAC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 8–12 June 2015; pp. 1–6.

- Zhang, T.; Gao, C.; Gao, Q.; Wang, G.; Liu, M.H.; Guo, Y.; Xiao, C.; Yan, Y.Y. Status and development of electric vehicle integrated thermal management from BTM to HVAC. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2015, 88, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paffumi, E.; Otura, M.; Centurelli, M.; Casellas, R.; Brenner, A.; Jahn, S. Energy consumption, driving range and cabin tem-perature performances at different ambient conditions in support to the design of a user-centric efficient electric vehicle: The QUIET Project. In Proceedings of the 14th SDEWES Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 1–6 October 2019; p. 18.

- Park, M.H.; Kim, S.C. Heating Performance Characteristics of High-Voltage PTC Heater for an Electric Vehicle. Energies 2017, 10, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Hrnjak, P. Performance characteristics of a mobile heat pump system at low ambient temperature. In SAE Technical Paper; SAE Interational: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018.

- Jung, H.; Silva, R.; Han, M. Scaling trends of electric vehicle performance: Driving range, fuel economy, peak power output, and temperature effect. World Electr. Veh. J. 2018, 9, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancă, P., Jamin, A., Nastase, I., Janssens, B., Bosschaerts, W., & Coşoiu, C. (2022). Experimental and numerical study of the flow dynamics and thermal behavior inside a car cabin: Innovative air diffusers and human body plumes interactions. Energy Reports, 8, 992–1002. [CrossRef]

- Steiner, A.; Rauch, A.; Larrañaga, J.; Izquierdo, M.; Ferraris, W.; Piovano, A.A.; Gyoeroeg, T.; Huenemoerder, W.; Backes, D.; Trenktrog, M. Energy Efficient and Comfortable Cabin Heating. In Future Interior Concepts; Fuchs, A., Brandstätter, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 89–100.

- Farzaneh, Y.; Tootoonchi, A.A. Controlling automobile thermal comfort using optimized fuzzy controller. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 1906–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Fleming, J.; Lot, R. A/C Energy Management and Vehicle Cabin Thermal Comfort Control. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 11238–11242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, D., Pino, F. J., Bordons, C., & Guerra, J. J. (2014). The development and validation of a thermal model for the cabin of a vehicle. Applied Thermal Engineering, 66(1–2), 646–656. [CrossRef]

- Nastase, I., Danca, P., Bode, F., Croitoru, C., Fechete, L., Sandu, M., & Coşoiu, C. I. (2022). A regard on the thermal comfort theories from the standpoint of Electric Vehicle design — Review and perspectives. Energy Reports, 8, 10501–10517. [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, A., & Kalsia, M. (2023). A Critical Review on Occupant’s Thermal Comfort Inside Electric Vehicle Car Cabin. 2023 2nd Edition of IEEE Delhi Section Flagship Conference (DELCON), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Cvok, I.; Škugor, B.; Deur, J. Control trajectory optimisation and optimal control of an electric vehicle HVAC system for favourable efficiency and thermal comfort. Optim. Eng. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.R.; Wang, H.; Gong, X.; Liao-Mcpherson, D.; Kolmanovsky, I.; Sun, J. Cabin and battery thermal management of connected and automated hevs for improved energy efficiency using hierarchical model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2020, 28, 1711–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaut, S.; Sawodny, O. Thermal Management for the Cabin of a Battery Electric Vehicle Considering Passengers’ Comfort. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2020, 28, 1476–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvok, I.; Ratković, I.; Deur, J. Optimisation of Control Input Allocation Maps for Electric Vehicle Heat Pump-based Cabin Heating Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Bauml, D. Dvorak, A. Frohner and D. Simic, "Simulation and Measurement of an Energy Efficient Infrared Radiation Heating of a Full Electric Vehicle," 2014 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion Conference (VPPC), Coimbra, Portugal, 2014, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Awari, G.K.; Kumbhar, V.S.; Tirpude, R.B. Battery Electric, Hybrid Electric, and Fuel Cell Vehicles; Automotive Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 243–252.

- D. Ramsey, A. Bouscayrol, L. Boulon and A. Vaudrey, "Simulation of an electric vehicle to study the impact of cabin heating on the driving range," 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring), Antwerp, Belgium, 2020, pp. 1-5. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).