1. Introduction

Poly (methyl methacrylate) or PMMA, is frequently employed as a biomaterial in the construction of both partial and complete dentures. This choice is driven by the material's advantageous physical and mechanical properties, its ease of fabrication, and its cost-effectiveness [

1]. However, PMMA is constrained by its absence of antimicrobial properties causing certain limitations. Consequently, there is a rising interest in enhancing PMMA integrated with antimicrobial characteristics. Methods involve integrating antimicrobial agents like nanoparticles or quaternary ammonium compounds into the PMMA matrix [

2]. Other approaches involve altering the PMMA surface using antimicrobial agents coated to surfaces or grafting techniques. These alterations are designed to inhibit the growth and colonization of bacteria and fungi on the denture surface, thereby mitigating the risk of oral infections and other associated health complications [

3]. In the oral cavity, primary colonizers of hard/enamel surfaces include mostly gram-positive

Streptococcus spp. [

41],

Staphylococcus aureus -commonly

MRSA [

39]

, Escherichia coli [4, 40] and other species including elevated levels of yeasts

(primarily

Candida spp.) [39, 40].

The discovery and development of alternatives to antibiotics are currently critically important. Traditional antimicrobial agents may have a broad spectrum against pathogens but may have significant side effects (e.g., diarrhea, colitis, shortage of commensal bacteria). Non-antibiotic approaches not only bring positive results in pathogen prevention, but also reduce the potential of bacterial resistance [

5]. Choosing an appropriate antibacterial agent is a complex choice that involves effectiveness, economics, human safety, governmental regulations, and, lastly, the likelihood of creating bacterial resistance. National and private scientific funding initiatives are preferring approaches dedicated to alternatives to antibiotics. As numerous countries are beginning to enforce stricter regulations on antibiotics, the need to adopt alternative agents on a commercial scale are becoming important.

Plants and their extracts have natural antibacterial properties and their ability to control oral pathogens has only recently been scientifically confirmed; additionally, they are recognized as promising against antibiotic-resistant bacteria [

5]. Plants are a natural and abundant source of prospective physiologically active compounds. Plants have evolved a variety of intricate mechanisms to counter continuous microbial threats in their environment. Since plants lack cell-based immune responses, they have had to devise alternative strategies for eliminating microorganisms. Plants include various useful components, including polyphenols, phenols, micronutrients, phytochemicals, and essential oils. In [

5], plants based antimicrobial agents have been compared with traditional antibiotics regarding their safety and toxicity profile.

Cannabis sativa L. known as the cannabis plant, produces over 120 different compounds which have relatively unknown pharmacological profiles. The constituents of C. Sativa consist of the psychoactive tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), non-psychoactive cannabidiol (CBD), mildly psychoactive cannabinol (CBN), followed by the parent molecule cannabigerol (CBG), cannabichrom (CBC) and in low amounts psychoactive cannabidiol (CBND) [6, 7]. CBD is a non-psychotropic compound and biocompatible [

8]. The antimicrobial characteristics of CBD have been used against multi-resistant bacterial infections including S. Aureus, S. Epidermidis and other gram-negative bacteria [

7]. The antimicrobial mechanism includes having a resorcinol moiety and a long pentyl tail for disrupting bacterial cytoplasmic cell walls [

7]. CBD provides the potential for various applications in the fields of dentistry and oral medicine. CBD has been used for oral care (e.g., toothpaste, mouthwash, dental floss), tooth whitening ability, injury repair potential, antifungal and anti-inflammatory agents, analgesic effects, and even treatment of viral infections [9 - 21]. CBD has been found to improve the recovery process of ulcers by lowering the number of colony counts of bacterial strains in dental plaque when compared to well-established chemical oral care solutions [

22]. CBD has antibacterial capabilities which may be beneficial in lowering the colony count of bacterial strains in dental plaque, thereby controlling and reducing bacterial-induced inflammatory periodontal infections [

22].

In summary, it appears beneficial to explore the possibility to use CBD as an antimicrobial agent in combination with other materials for dental applications. In this research, we have synthesized an antibiotic free, polymer coatings enriched with CBD for coating surfaces of denture materials. The monomer, methyl methacrylate (MMA), was synthesized under UV irradiation with the addition of CBD, and the necessary UV curing duration was examined. The use of UV radiation in the polymerization of methyl methacrylate (MMA) to polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) has benefits over traditional heat-initiated polymerization. UV curing provides much faster (15 min) polymerization over thermal polymerization which takes around 6h to 10 h [

38]. Heat curing also requires higher temperatures, 60 ˚C to 90˚C to achieve high yields whereas UV curing can be done in lower temperature reducing energy costs in achieving similar yields [

38]. After the spectroscopic, microscopic, and analytical characterization of the coatings, their antibacterial, antibiofilm activities, and drug-release profile were examined to show the utility of this new coating.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Coating Characterization & Analysis

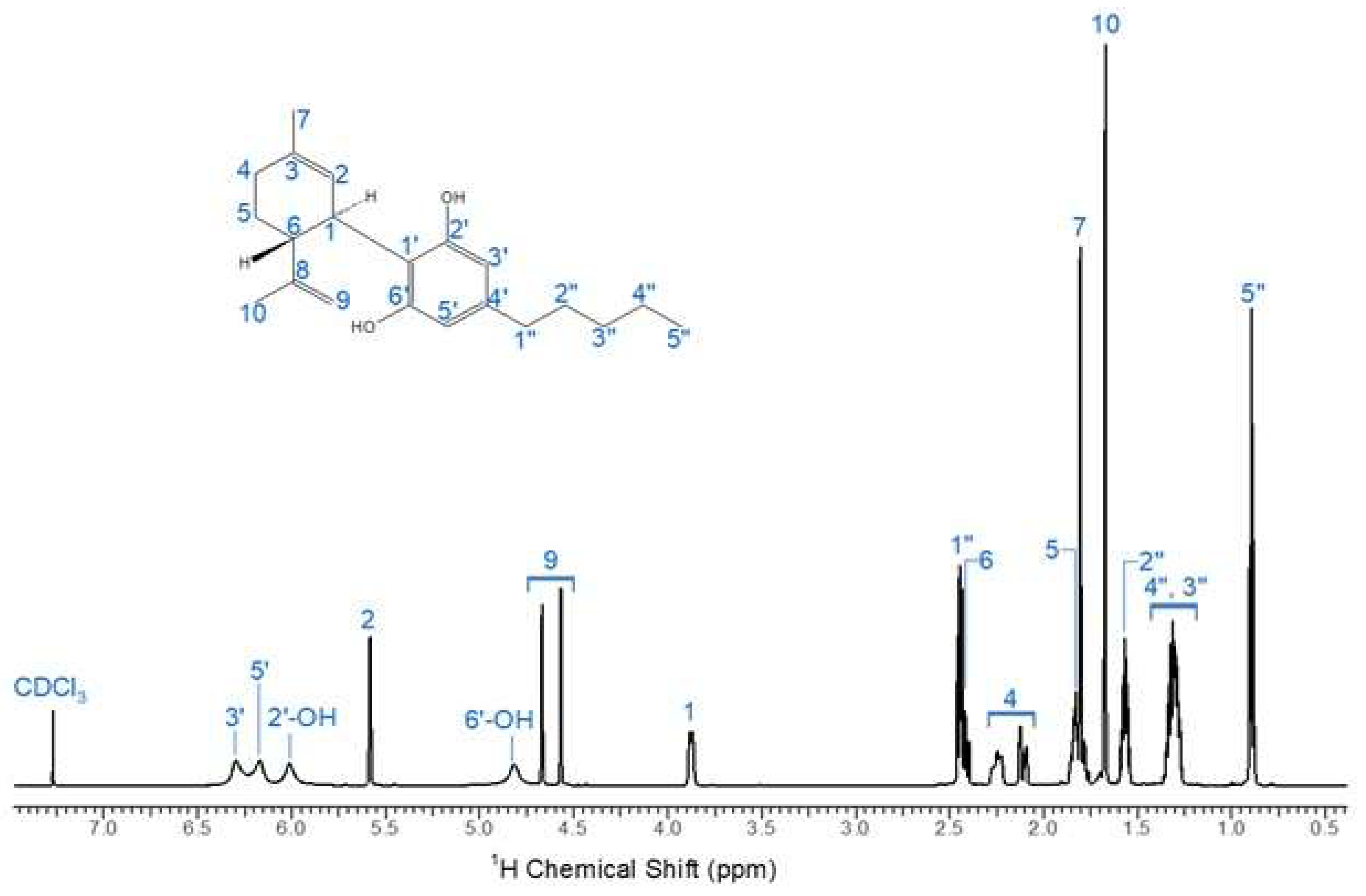

To assess the purity of the industrial CBD crystal samples, CBD fractions were analyzed and characterized using 1H NMR spectroscopy on a Varian Inova – 600 (California, USA). The CBD structure is confirmed demonstrating the absence of any other chemical compounds. The quantification of cannabinoids of interest involved comparing the peak intensity and integration numbers of our CBD sample to those documented in literature [

25]. The unique feature of CBD is that the proton signal of the aromatic protons was about 5.9 - 6.28 (

Fig. 2) clearly broadens in the 1H NMR spectrum in contrast to signals of the other cannabinoids [

25].

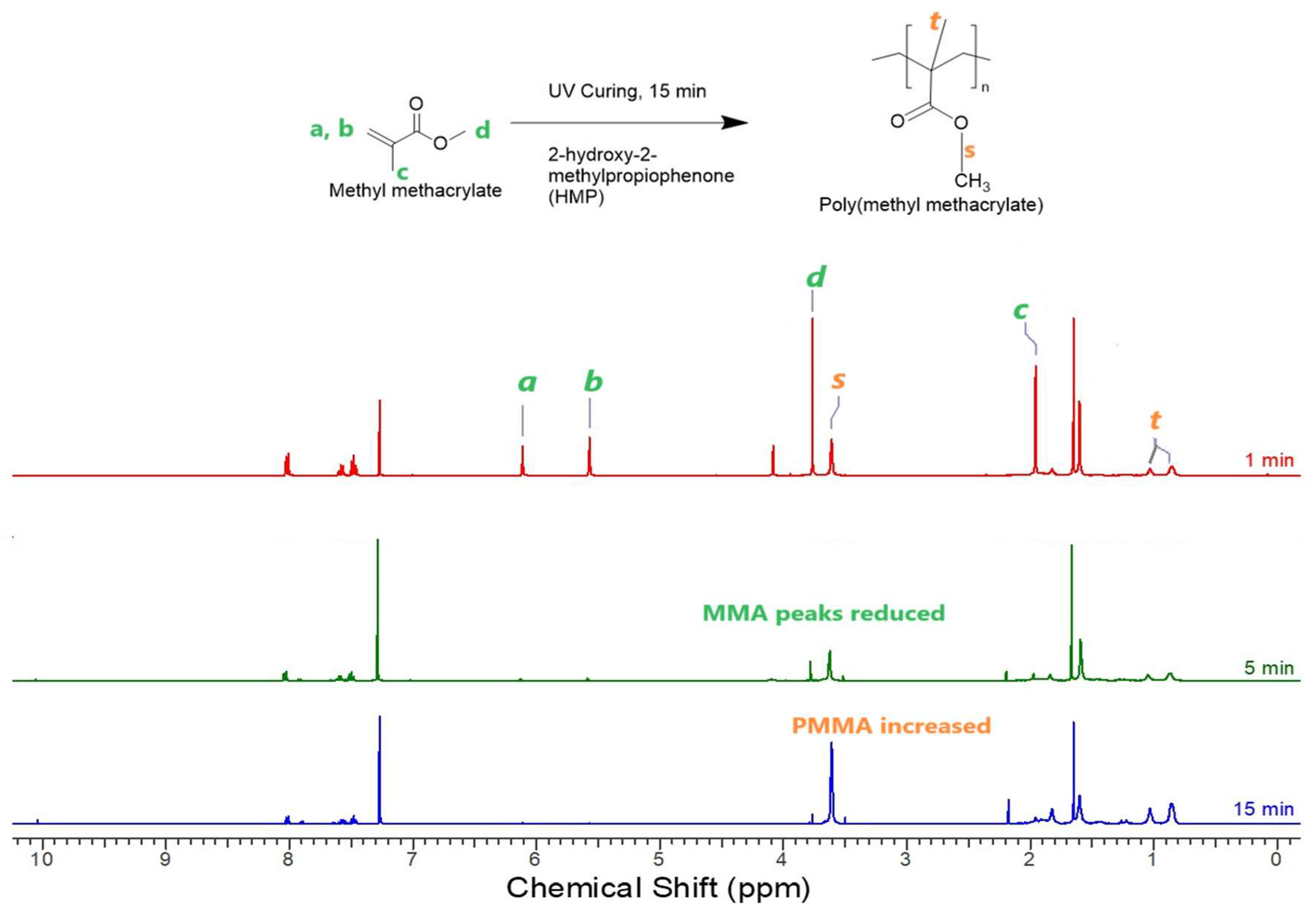

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectrum of PMMA coatings with 1-, 5-, and 15-min UV curing.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectrum of PMMA coatings with 1-, 5-, and 15-min UV curing.

Of interest for polymer synthesis is the available vinyl group on C8-C9 of the CBD structure. The copolymerization process involved the addition of MMA monomer, which was polymerized in the presence of the extracted CBD through a UV curing method using the UV photo initiator HMP. HMP functions by absorbing UV light energy, generating free radicals that initiate the polymerization. In this context, HMP absorbs UV light within the wavelength range of 220 to 390 nm, to initiate synthesis reactions.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum of CBD in Chloroform - d.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectrum of CBD in Chloroform - d.

To determine the necessary UV curing time for polymerization completion, the system comprising MMA, CBD, PMMA, and HMP was explored. PMMA, acting as a thickener, was incorporated at 0.08 mol of MMA. The investigation involved examining the

1H NMR spectra of UV-cured PMMA coating samples with varying UV curing times, as depicted in

Fig. 1. The peaks of 0.80 -1.2 ppm corresponded to the –CH

3 group of PMMA (

t) and other peaks of 6.25 – 5.58 corresponded to MMA peaks (

a, b).

Analysis was done on the UV curing process observing if the characteristic peaks of MMA were still evident at 3.76, 6.11 and 5.57 ppm, which would suggest an incomplete conversion of the MMA monomer. At 5-minute the MMA peaks of 6.11 ppm and 5.57 ppm were still visible, and the curing time was extended until all the MMA peaks disappeared at 15 minutes or beyond, indicating complete polymerization. The –OCH3 peaks of PMMA at 3.6ppm were highest at 15 min in compared to that at 1 and 5 minutes. The C=C bond peaks (a, b) at 6.11 and 5.57 ppm were seen in small amounts at 5 min, but disappeared at 15 minutes, suggesting complete conversion of MMA to PMMA.

2.2. Antimicrobial Studies

2.2.1. MIC Studies:

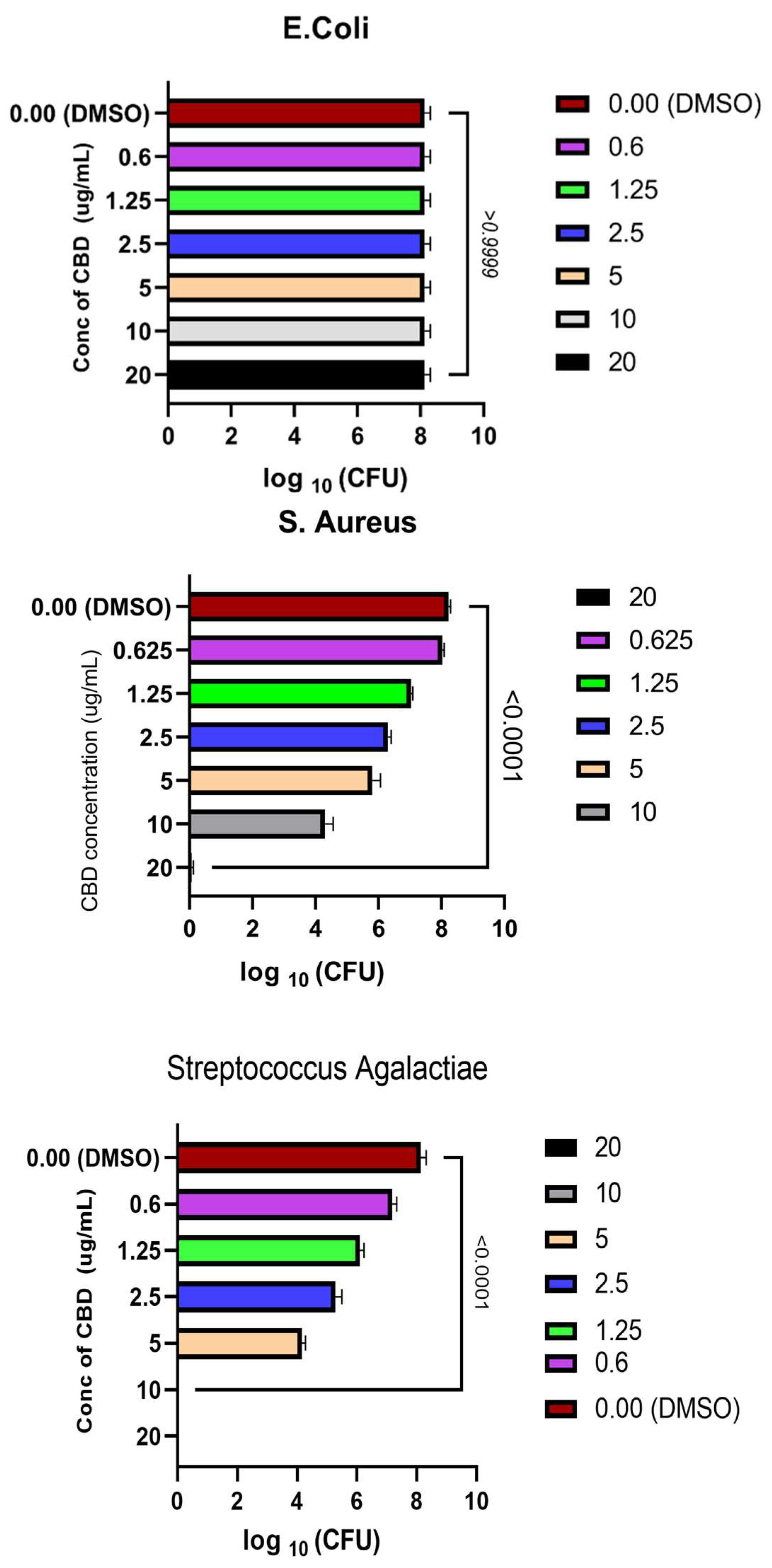

Minimum inhibitory concentration values allow us to obtain satisfactory ideas about the potency of CBD before use as coatings against different pathogenic microorganisms. The results of in vitro effects of CBD dissolved in the solvent DMSO against pathogenic yeast and bacteria are demonstrated in

Table 1. According to the obtained MIC results, the synthesized coating suppressed the growth of

S. agalactiae more effectively than other pathogens. The inhibition effects of CBD coatings on studied pathogens were

S. agalactiae >

S. aureus >

E. coli. CBD was proven to be ineffective against gram-negative bacteria. This type of bacteria contains lipopolysaccharides and proteins with very little phospholipid on the outer leaflet of the outer membrane, which is a critical element in the membrane's effective resistance. PMMA being a large macromolecule, when combined with hydrophobic CBD, the membrane of

E. coli is not permeable to macromolecules and limits diffusion of hydrophobic compounds [

27].

Figure 3.

CBD concentration kill curve against S.agalactiae, E.coli & S. aureus and their respective P-value.

Figure 3.

CBD concentration kill curve against S.agalactiae, E.coli & S. aureus and their respective P-value.

Our research findings are consistent with the MIC values observed for S. aureus and Streptococcus species in [

28], ranging from 1 to 5 µg/mL, which closely resemble our own results. Our results for MIC studies on gram negative bacteria was also consistent with previous reports [

28], where CBD was inactive against 20 species of Gram-negative bacteria (

E. coli,

Klebsiella pneumoniae,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa and

Acinetobacter baumannii).

2.2.2. Zone of Inhibition studies:

The antimicrobial activities of CBD were evaluated against each microbe using the disk diffusion method. The results in

Table 1 show that the solvent DMSO had no significant effect on the antimicrobial activity of the purified CBD. The strongest inhibitory activity was observed by CBD against

S. agalactiae and then

S. aureus. The ZOI studies demonstrated CBD had no effect on gram negative

E. coli, attributed to the fact that these do not have an outer membrane. Gram-positive bacteria lack this important layer, which makes Gram-negative bacteria more resistant to antibiotics than Gram-positive bacteria.

Table 1.

MIC /MBC of CBD and Inhibition Zones of CBD.

Table 1.

MIC /MBC of CBD and Inhibition Zones of CBD.

| Strain |

MIC (µg/mL) |

MBC (µg/mL) |

ZOI(mm) at 20 mg |

ZOI (mm) at 200 mg |

| S. Aureus |

2.5 ± 0.4 |

20 ± 0.5 |

11 ± 1 mm |

20 ± 1 |

| S. agalactiae |

2 ± 0.1 |

10 ± 0.4 |

9 ± 1 mm |

17 ± 2 |

| E.coli |

Resistant |

Resistant |

No Zones |

No zones |

2.3. Bactericidal Studies

The observed MBC of CBD was determined by spot plating the bacterial suspensions from the MIC culture tubes on fresh agar plates for the three microorganisms. The lowest concentration resulting in no viable bacterial colonies was reported as MBC and recorded in

Table 1. MBC represents the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent required to

A one-way ANOVA test by PRSM software was used, to compare the coated MMA with no CBD and the coatings synthesized with different concentrations of CBD (

Fig. 3) for each pathogen. The P- values were noted for each pathogen. There was a significant difference between the values with CBD and the ones treated with only solvent DMSO and their P- value (P < 0.0001 ) was calculated for

S.aureus and

S. agalactiae. This showed that we can accept the hypothesis, that the groups treated with CBD and the ones that had no CBD, were statistically significantly different from each other, and CBD concentration influences the log CFU counts of the cell for gram positive bacteria. According to the obtained MBC outcomes, CBD caused cell death of Streptococcus group B more effectively than Staph. The bactericidal effects of CBD were

S. agalactiae >

S. aureus >

E.coli.

As for gram negative,

E.coli, CBD was ineffective (P > 0.99999 ) and the justification was similar to that given in

Section 2.4.1. No prior studies had cited papers demonstrating bactericidal effects of specific cannabis compounds. However, our research revealed that CBD exhibits potent antimicrobial properties against gram-positive bacteria. Furthermore, our findings demonstrated that pure CBD at certain concentrations effectively eradicated microbial populations, as evidenced by minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) values.

2.3. AntiBiofilm Studies

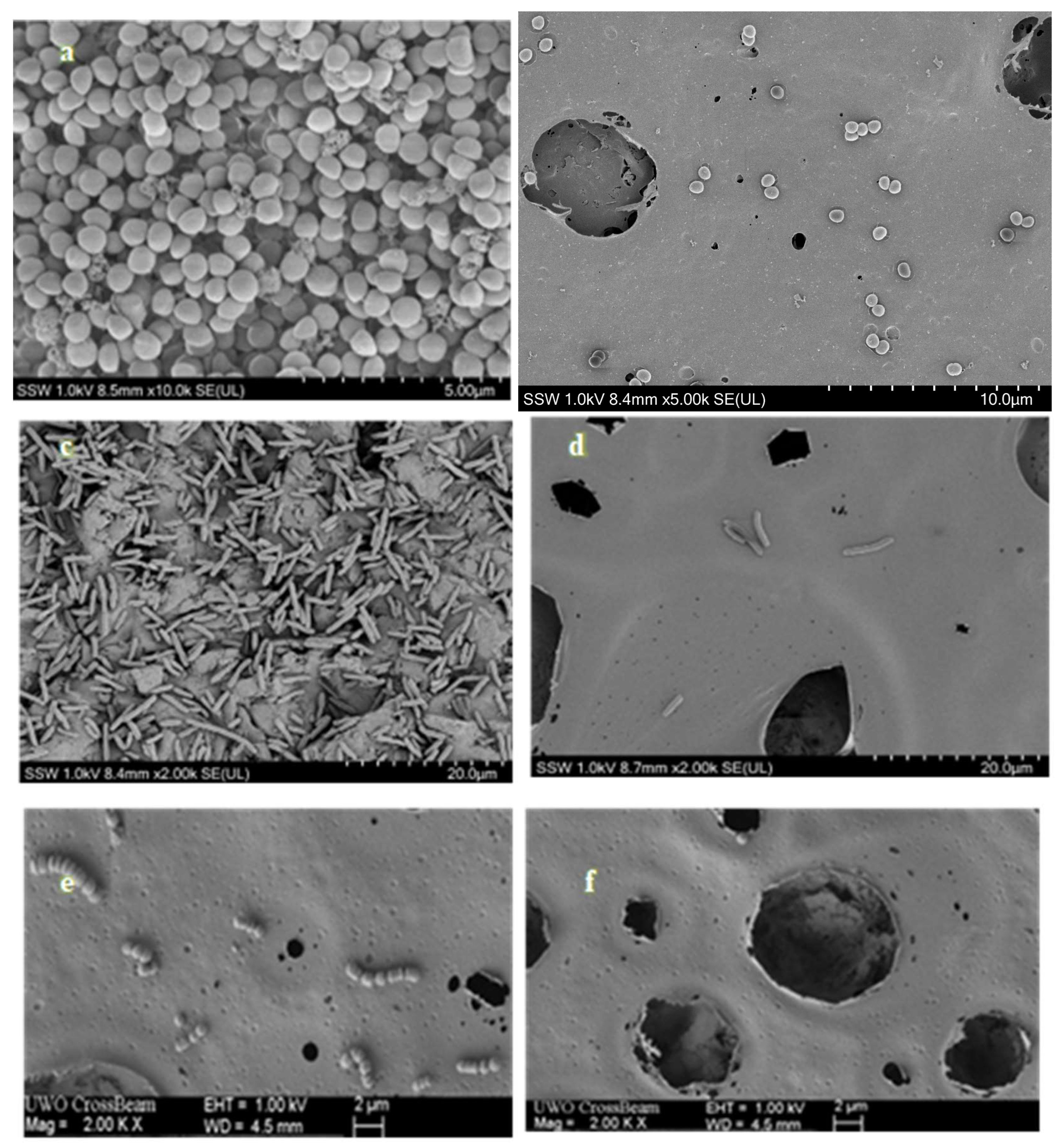

2.3.1. Visual Analysis of Biofilms on Coatings

The SEM images of

Figure 4, depict a representative field of view at magnifications of 10,000× , 2000× , respectively, for each surface treated with

S. agalactiae,

S. aureus and

E. coli. Additionally, within the same figure, we showcase selected representative fields of view for the biofilm formed on both PMMA coated (control) and PMMA/CBD-coated discs after 24 hours of incubation. The contrast in the quantity of biofilm volume between the only PMMA coated and PMMA/CBD coated surfaces is readily apparent and aligns with quantitative data in Section 3.4.2. On surfaces coated with PMMA only, microbial cells were organized in mono- and multi-layered structures, covering most of the surface area, regardless of the type of strain (

FIgure 4(a), 4(c) and 4(e)). Conversely, in CBD /PMMA coated samples, there was rarely a presence of bacterial cells, either singular or forming small clusters on the surface. For surfaces treated with

S. agalactiae, the bacteria were primarily concentrated within the crevices and recesses of the coating (illustrated in

Figure 4 (f)). The least number of microbial cells on the surface was observed on the CBD/PMMA disc surface when incubated with the

E. coli strain (

Figure 4(d)).

Qualitative Evaluation of CBD's Inhibitory Effects on Gram-Negative Biofilms: Biofilms are usually more resistant (resistant (100–1000-fold )fold) to drugs compared to their planktonic counterparts. Biofilm formation in

E. coli is a complex developmental process that occurs in different phases: reversible and irreversible attachment, maturation, and dispersion [

31]. There were no

E. coli biofilms observed on the PMMA/CBD coatings although there was a significant amount of biofilm observed on the media surrounding the disc. This was due to the CBD in the coating, inhibited adhesion properties of the cells, which is the first stage of biofilm formation, is an excellent preventive strategy to control biofilms. CBD has been reported to affect genes expressions involved in biofilm maintenance, development, and maturation of factors associated with exopolysaccharide (EPS) synthesis [

32]. EPSs establish the functional and structural integrity of biofilms, and biofilms and are considered the fundamental component that determines the physicochemical properties of a biofilm. CBD may modify the architecture of

E. coli biofilms as well, by reducing its thickness and exopolysaccharide (EPS) production accompanied by downregulation of genes involved in EPS synthesis. CBD may affect the biosynthesis of fimbriae, surface proteins, virulence factor genes, and other bacterial structures involved in adherence to surfaces. CBD does not inhibit planktonic

E. coli cells as it targets the genes required for synthesizing fimbriae and EPS. Fimbriae are not necessary for planktonic bacteria as planktonic bacteria do not typically require attachment to surfaces or host cells. Planktonic bacteria exist as free-floating individual cells in a liquid medium, where they can move and disperse freely. Both fimbriae and EPS production primarily facilitate adhesion and attachment to surfaces, host tissues, or other cells, which is essential for processes such as biofilm formation and infection. Since planktonic bacteria do not need to adhere to surfaces or host tissues, they do not require these features for their survival or growth in the planktonic state. CBD may target these genes and be effective only for biofilms, it still remains ineffective against planktonic E. coli as they may still possess fimbriae or similar structures, albeit in reduced or modified forms. These structures might serve alternative functions in the planktonic lifestyle, such as facilitating interactions with other bacteria or sensing environmental cues. Nevertheless, since these structures are not typically considered necessary for the planktonic mode of growth – CBD remains ineffective for

E.coli in the planktonic phase as shown in

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4.

Qualitative Evaluation of CBD's Inhibitory Effects on Gram-Positive Biofilms: Gram positive bacteria, bacterial membrane properties, including hydrophobicity, are crucial for initial bacterial adhesion, a critical step in biofilm development. CBD/PMMA coatings have shown to be very hydrophobic and could target bacterial cell-surface hydrophobicity. Recent studies [

33] showed endocannabinoid effectively modified the cell-surface properties of MRSA strains, reducing their hydrophobicity which contributed to antibiofilm activity, as higher cell-surface hydrophobicity has been linked to increased biofilm formation levels. Endocannabinoid and CBD are both cannabinoids, but the production is in different hosts – CBD is plant sourced whereas endocannabinoids are endogenous [

34]. Similarly, CBD must also modify the cell membrane properties of S. agalactiae and S. aureus which reduced their potential to form biofilms. It was already stated in

Section 2.4 that CBD changes the membrane potential, causing membrane depolarization. In this study we propose, the mechanisms of action against planktonic bacteria of the coatings we tested is due to their ability to modify the bacterial membrane potential, which then leads to changes in biofilm-related characteristics of gram-positive bacteria, such as hydrophobicity and cell aggregation.

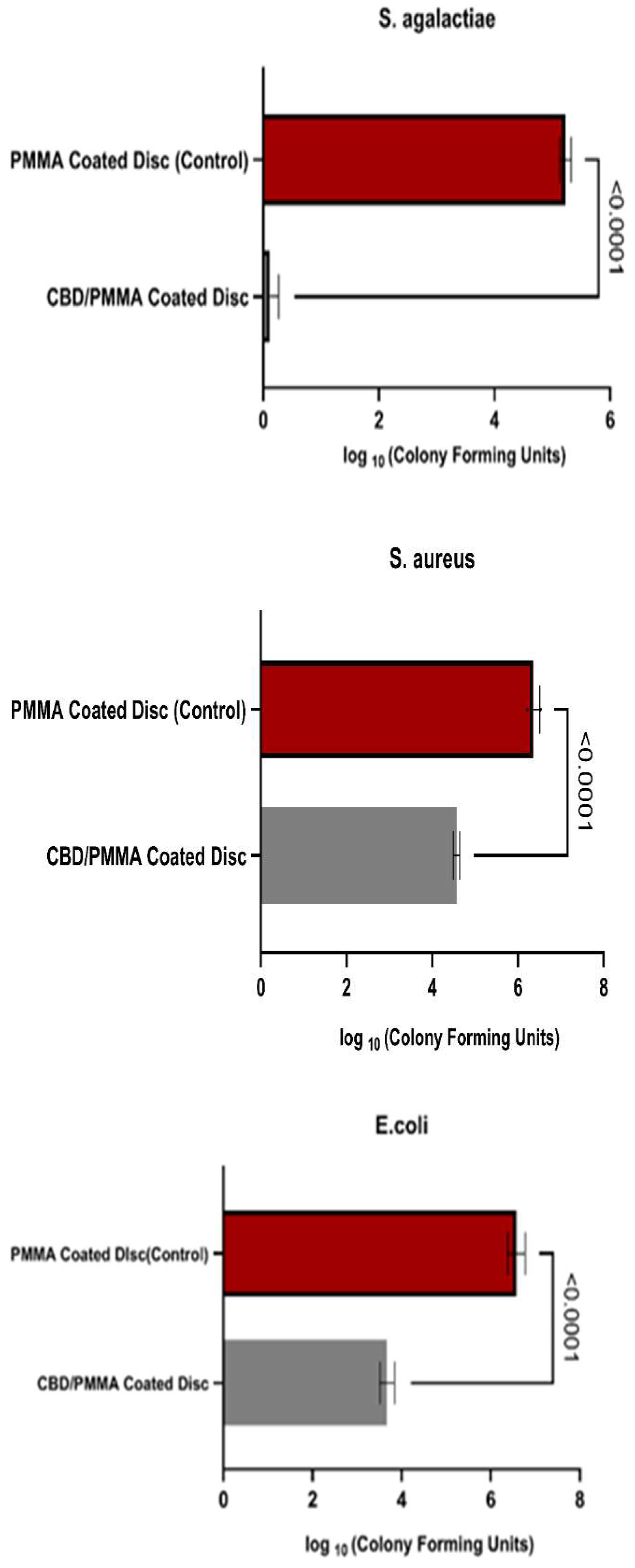

2.3.2. Quantitative Analysis of Biofilms

The results of bacterial biofilm formation experiments are presented in

Fig.6. The largest significant difference in bacterial adhesion and growth between the CBD/PMMA coated disc and PMMA coated disc was on

S. agalactiae biofilms. S. agalactiae growth on the PMMA surface was significantly 10,000 times greater compared with both thethe PMMA/CBD discs. This was confirmed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with

p < 0.0001. CBD enriched coatings in the PMMA reduced Strep biofilms 99.99 %.

Quantitative Evaluation of Inhibition in Gram-Positive Biofilms : In the S. aureus group, their biofilm was reduced 100 times (2 log fold) in PMMA/CBD surfaces as compared to PMMA surfaces. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with p < 0.0001 was used to confirm the results. The addition of CBD in the coatings reduced Strep biofilms by 99 %.

Overall, S. agalactiae had the lowest growth on the synthesized surfaces, bacteria were observed to be formed less on the media surrounding the surface. E. coli showed the least biofilm attached on the surface, although there was significant growth on the media surrounding the disc. The most significant difference between materials was found in S. agalactiae with a reduction of 99.99 % biofilm formation. The results match the SEM images in Section 3.4.1 where there was no S. agalactiae biofilms in the CBD/PMMA coatings although we noticed some growth in PMMA coatings. Equivalent levels of bacterial proliferation were observed in both S. aureus and E. coli in both the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) visuals and quantitative assessments of CBD/PMMA coatings.

Quantitative Evaluation of Inhibition in Gram-Negative Biofilms: As for the gram-negative bacteria, E. coli biofilms had reduced attachment on the PMMA/CBD surface, there remained significant amounts of biofilm attached to the media surrounding the surface. Escherichia biofilms were reduced 100 times (2 log fold) in PMMA/CBD surfaces as compared to PMMA surfaces. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with p < 0.0001 was used to confirm the results. The addition of CBD in the coatings reduced E. coli biofilms from growing and attachment by 99 %.

2.4. CBD Release Profiles

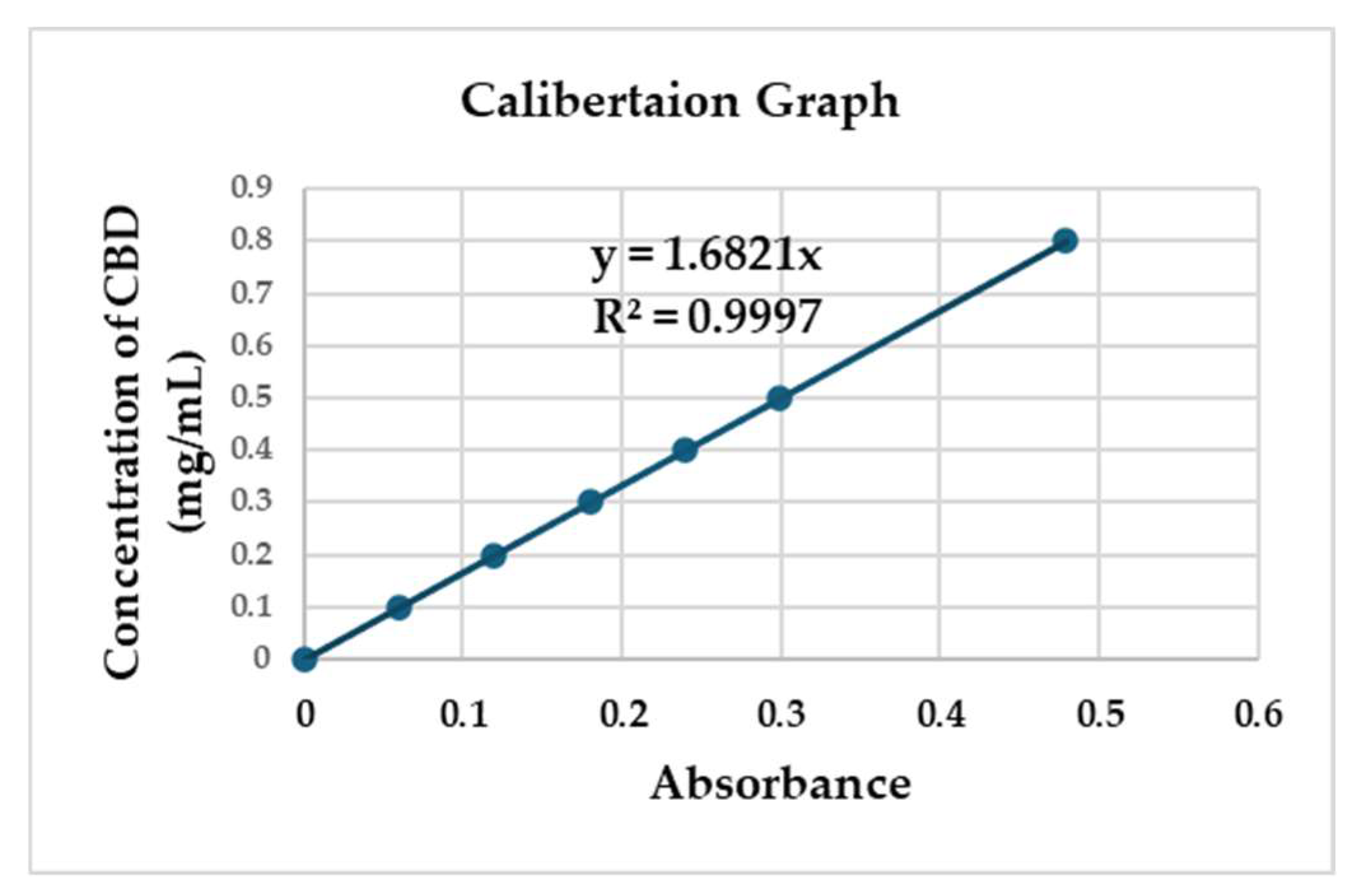

2.4.1. Linear Calibration

Calibration graphs of CBD concentration vs. absorbance were constructed covering a concentration range 0 –800 µg/ml. Three independent determinations were performed of the six concentrations levels. Linear relationships between the absorbance versus the corresponding CBD concentration were observed. It's important to highlight that CBD – absorbance relationships don’t adhere to linear patterns when concentrations surpass 800 µg/ml. This means that increasing the dosage beyond this threshold makes it very difficult to dissolve in water-based solvents due to its fat-soluble nature. The standard deviations of the slope and intercept were low. The determination coefficient (r2) was 0.997(

Fig. 7).

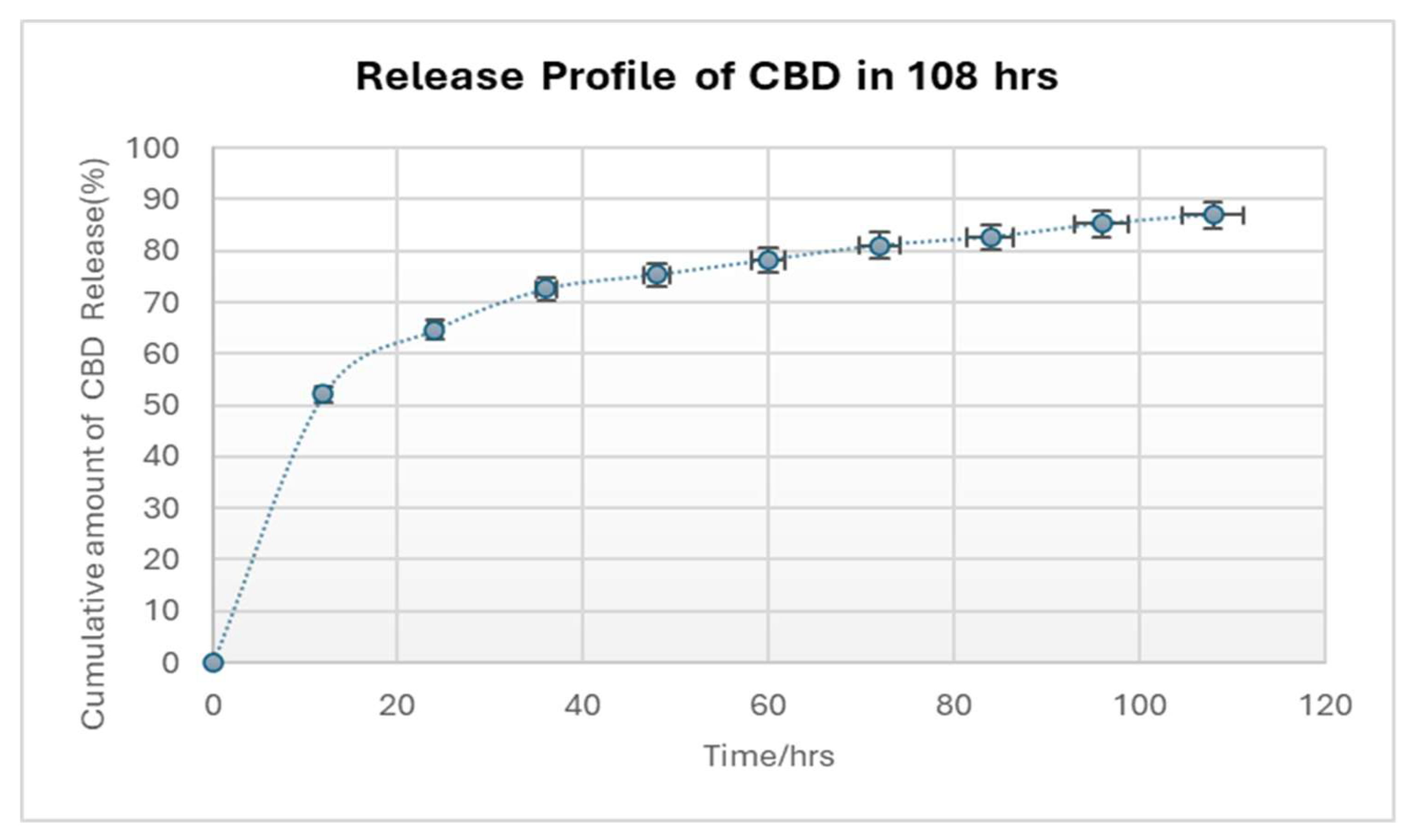

2.4.2. Release Studies and Analysis

The in vitro CBD release characteristics of the CBD/PMMA coatings were studied. Dissolution data for all the experiments were highly reproducible and hence only the average values were plotted. The synthesized coatings were examined for release of CBD as shown in

Fig. 8. The three coated discs of CBD/PMMA were shown to have nearly identical cumulative release profiles; after a high initial release of CBD, a reduced yet constant sustained release was observed. In the first 12h, 50 % of the CBD was released promptly for 1000 mg-loaded CBD coating, which could be attributed to dissolution of the adsorbed particles or to diffusion of CBD located close to the surface of the coating. Since the coating was thin (< 0.5 mm), it is probable that most of the CBD molecules were entrapped close to the surface of the coating. This factor could facilitate the observed initial burst release [

37]. The burst phase, lasted ≈ 12 hours. Another 50 %–80.5% was released in a slow linear-like fashion over the rest of the 2 days, and after 80 h of CBD release, the release rate of became constant. In our system, the CBD released from coatings lasted for almost 108 h. Hence, the coating was found to have the ability to deliver antimicrobial agents in a controlled manner. The observed burst effect is the reason behind the anti-biofilm capacity of the coatings. The interaction between antibiofilm agents and the burst effect of drugs is a critical consideration in combating bacterial infections, particularly those associated with biofilm formation. In the case of antibiofilm CBD, a burst release could potentially lead to a rapid disruption of the biofilm matrix, allowing bacteria to be quickly eradicated.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals,Culture Media and Microorganisms

Cannabidiol (CBD) isolate was supplied by the Mera Cannabis Corp, ON, Canada. Methyl methacrylate (MMA, 99 %) and photo initiator, 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone (HMP, 97 %), poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA, Mw = 350,000 Da), Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA), Tryptic Soy Broth, LB miller’s formulation culture medium, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Canada. Acetonitrile and chloroform were purchased from Caledon Laboratory Ltd, Ontario. Glucose Anhydrous (powder) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and was dissolved in deionized water. Pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (ATCC® 29213™), Escherichia coli (E. coli) (ATCC® 25922™), Streptococcus agalactiae (S. agalactiae) (ATCC® 29213™) were used from Heinrichs Lab stock (Microbiology and Immunology, Western University, London, ON).

3.2. Isolation and Characterization of CBD

CBD samples were purified and characterized as outlined in [

23,

24]. To assess the purity of the obtained CBD crystal samples, samples were conducted using

1H NMR spectroscopy on a Varian Inova – 600 (California).

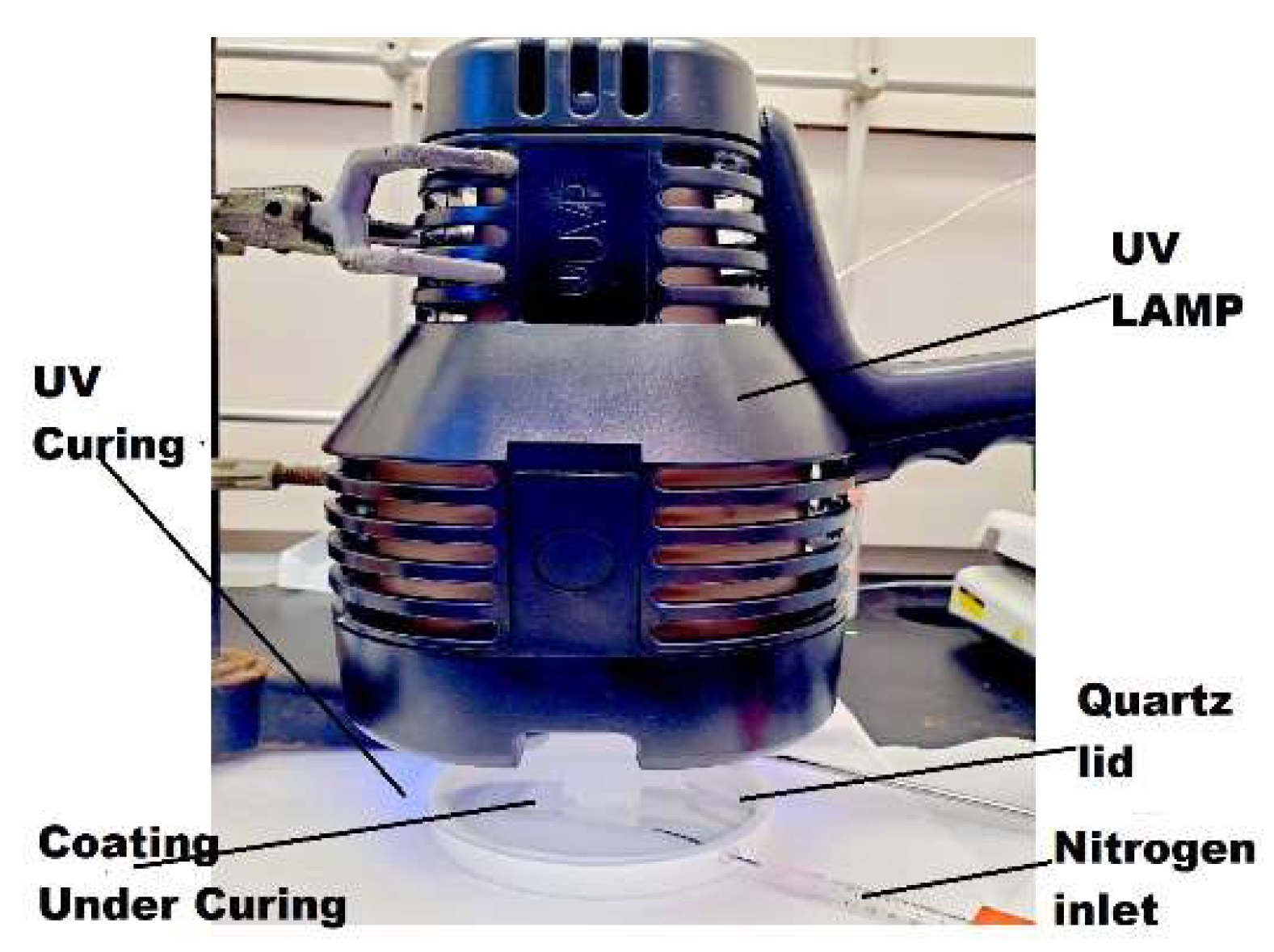

3.3. Synthesis of MMA and CBD Coatings

0.62 g of CBD was dissolved in 1.001 g of MMA, with a molar ratio of 1: 0.2. Then 0.08g of PMMA and 0.0328 g of photo initiator HMP were added. PMMA was used as a thickener to increase the viscosity of the reaction mixture. 0.2 mL of the mixture was dropped and evenly spread onto a 15 mm in diameter and 1 mm in thickness titanium disc, pre-cleaned by sonication in ethanol for 20 min and drying in air. The use of metal discs was to facilitate SEM imaging feasibility. The thin layer of coating on the titanium disc was cured inside a flat-bottom Teflon evaporating dish covered with a quartz lid under UV irradiation (UVP 95-0127-01 Blak-Ray™ B- 100AP lamp, 100 W, 365 nm longwave, USA) for 1 min, 5 min and 15 min time. The evaporating dish was purged with nitrogen gas before and during UV curing by means of a plastic tube. After that, the coated disc was placed in a vacuum oven to remove any remaining VOCs in the coating. In the preparation of all coating samples, the intensity of UV light received by the coating was measured to be 8335 μW/cm2 by a Sper Scientific 850,009 UVA/B light meter. The distance from the UV light source to the coating surface was 4 cm.

3.4. Coating Characterization

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were collected using a Bruker Avance III HD 400 spectrometer. CBD/PMMA coatings were dissolved in deuterated chloroform. The morphologies and surfaces of the coatings particles were tested by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and analysed by ImageJ Software. To determine the best ratio of CBD/PMMA for forming uniform coating SEM images of CBD/PMMA coatings before/after exposure to fluids. To examine the surface morphology following exposure to fluids, assessing whether the leaching of the CBD component occurred for enhanced biofilm efficacy. CBD leaching is necessary for the coating to function in combating pathogenic biofilms.

Figure 9.

Experimental setup for UV curing of coatings.

Figure 9.

Experimental setup for UV curing of coatings.

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity of CBD

3.5.1. Zone of Inhibition Studies:

This approach was used to validate the antimicrobial potential of CBD on the tested pathogens. The agar disk diffusion method [

26] was used to evaluate cannabidiol solutions in DMSO. Agar plates were inoculated with a standardized O.D 1 inoculum of

S. Aureus (ATCC® 29213™), E.

Coli (ATCC® 25922™),

S. Agalactiae (ATCC® 10231™). Filter paper discs (6mm dia.), containing 10 µl CBD solution in DMSO at a concentration of 20 mg/ml and 200 mg/ml (amount like the CBD release studies in Section 2.8) were placed on the agar surface. The petri dishes were incubated overnight in 37 ºC. The antimicrobial CBD diffused into the agar media and inhibited growth of the microorganism which was measured by the diameter of inhibition growth zone and recorded.

The solvents, DMSO was used as control for inhibition zone studies as well

3.5.2. Modified Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC):

This approach was used to assess the efficiency of CBD against Pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC® 29213™), Escherichia coli (ATCC® 25922™) and Streptococcus (ATCC® 10231™) before using it for coating purposes. To determine the MIC for CBD by dissolving in warm DMSO to make concentrations of 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1, 0.6 µg/ mL. The various concentrations of CBD in DMSO solution was added to 1 mL of Tryptic soy broth (TSB) growth media. DMSO was used as control. 10µL of each bacteria at an OD600 1 was added to each sample, reaching a starting OD600 of 0.1, the samples were then incubated at 37 °C with shaking for 24 hours. The OD of the samples were then measured in a 96 well plate using a microplate spectrophotometer from Biotek instruments (USA), and the MIC was determined as the lowest concentration with no discernible growth was recorded. The experiment was repeated in three separate trials and the results were recorded.

3.6. Bactericidal Activity of CBD

Minimum Bactericidal Concentration for CBD was also determined by preparing solutions in DMSO similar to procedure described in

Section 3.5. Prepared CBD samples with concentrations ranged from 20, 10, 5, 2.5, 1 mg/mL were tested against Pathogenic

S. aureus (ATCC® 29213™),

E. coli (ATCC® 25922™) and

S. agalactiae (ATCC® 10231™) were added to each sample at an initial OD

600 0.01. The samples underwent incubation at 37 °C for 24 hours. After incubation the samples were platted and their respective colonies were counted and recorded. The MBC was defined as the least concentration of CBD which eradicated 99.9% of the original inoculum and no colony forming unit was observed when plated. The experiment was replicated in three distinct trials, and the outcomes were graphed using GraphPad Prism (California, USA).

3.7. Biofilm Studies of PMMA/CBD Coatings

Three strains,

Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC® 29213™),

Escherichia coli (ATCC® 25922™) and

S. agalactiae (ATCC® 10231™) , were used in this study, given their ability of producing high amount of slime according to the methods and criteria proposed in [

30]. Strains were stored at − 80 °C (Heinrichs Lab, Western University) and grown on Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) plates at 37 °C for 20 h before experimental assay.

S.aureus and

S. agalactiae suspensions at the concentration of 1 × 10

7 Colony Forming Unit per mL (CFU/mL) were prepared in TSB supplemented with 40 % w/v glucose (Fisher Chemicals) while L.B. was used for

E. coli experiments, to induce slime production [

30].

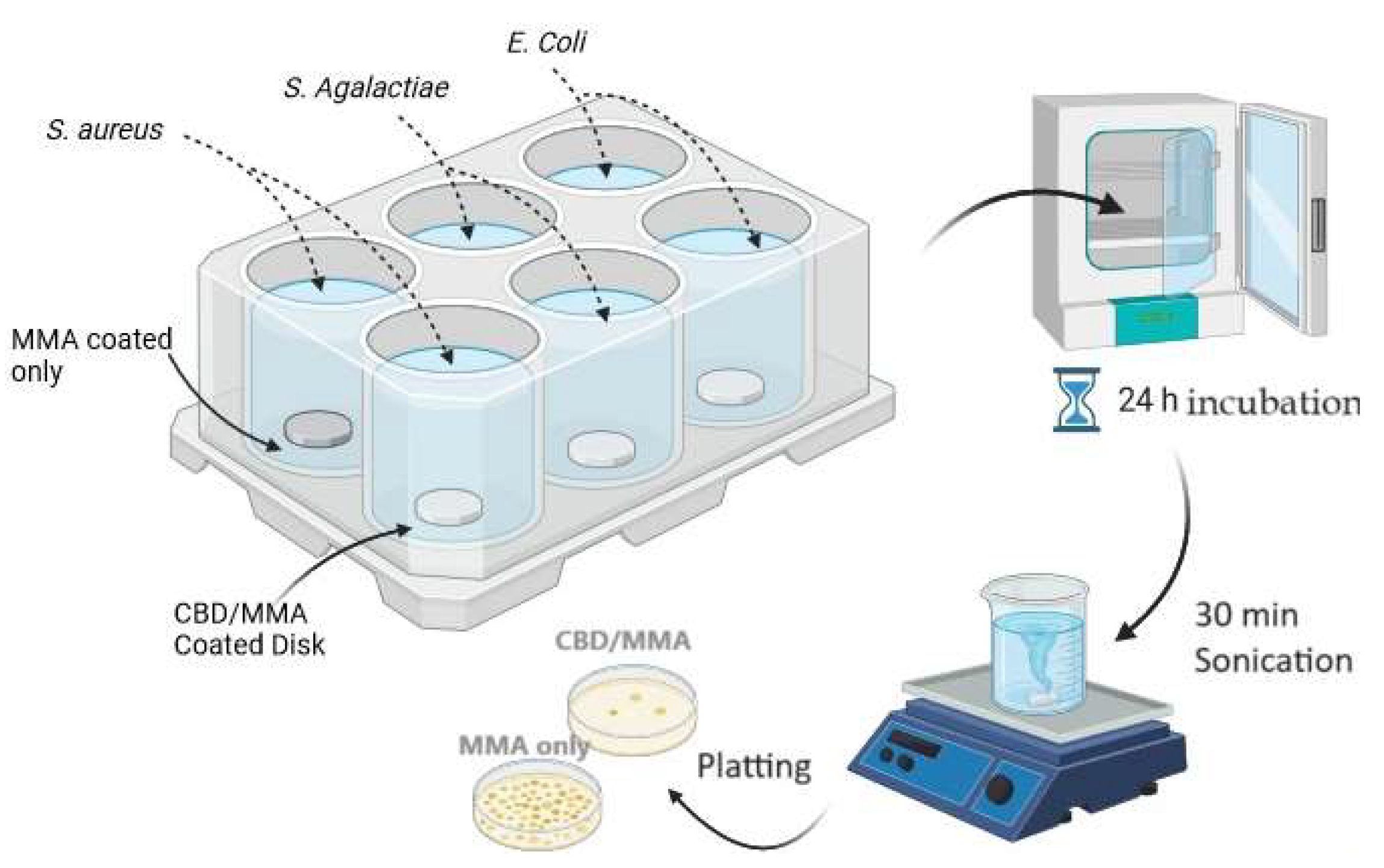

Biofilm formation on the surface of the coated discs (both PMMA/CBD coated and PMMA coated control discs) was obtained in 6-well plates fitting one disc for each well. 20 µL of bacterial suspension, 10 µL of a 40% (v/v) glucose solution, 2 mL broth media, was added to each well, thus guaranteeing submersion of the disc into the medium with bacteria. Plates were then immediately incubated at 37 °C for 24 h under static conditions. Two independent replicate experiments were conducted.

Figure 10 shows the workflow for the biofilm studies.

3.7.1. Visualization of Biofilm Formation by Scanning Electron Microscopy

Biofilm formation on the coated and uncoated surfaces after 24 h of incubation was imaged with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for visual assessment. After incubation, the samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and 2.8% glutaraldehyde for 1 h at room temperature followed by a washing step with 0.1 M HEPES buffer 3 times and slow dehydration using 30 %, 50 %, 70 %, 95 % and 100 % ethanol in series. In order to reduce sample surface tension, samples were immersed in 25 %, 50 %, 75 %, 90 % and 100 % hexamethyldisilizane (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min and evaporated overnight under the fume hood, before mounting on aluminum SEM stubs and sputter-coating with a 10 nm gold-palladium layer, using a Leica EM ACE600 sputter coater (Leica Microsystems). Pictures of experiments with Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli were taken at random locations with various magnifications depending on the bacterial size using scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (SEM/EDX) using a Hitachi SU8230 Regulus ultra-high resolution field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) combined with a Bruker X-Flash 6160 SSD X-ray detector. Pictures of experiments with S. agalactiae were taken with Zeiss 1540XB Cross Beam.

3.7.2. Quantitative Tests for Biofilm Formation

After the 6 well plates were incubated and the biofilms were formed, the samples were gently tilted to remove nonadherent bacteria. For quantitative culture, bacteria were subsequently detached from the coated discs in a sterile tube with 4 mL of PBS by 30 min of sonication (Elma Transsonic T460, 35 kHz; Elma Schmidbauer GmbH, Singen, Germany). This detachment method was highly efficient, resulted in the removal of the vast majority of bacteria attached, and seemed comparable between PMMA/CBD and MMA. Ten-fold serial dilutions of each sonicated solution were made in PBS and triplicate 10 μL aliquots of the sample and the dilutions were spotted on TSA agar plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C and the number of CFU/implant were determined and tables were plotted.

Figure 10.

Diagram of the protocol used to test synthesized coatings on biofilms of S. aureus , E. coli and S. agalactiae.

Figure 10.

Diagram of the protocol used to test synthesized coatings on biofilms of S. aureus , E. coli and S. agalactiae.

3.8. CBD Release Studies

3.8.1. Standard Solutions and Calibration Curves

The protocol mentioned in [

35] was followed to study the drug release of CBD from the coating. Different working standard namely 0.033 mg/ml , 0.10 mg/ml, 0.2 mg/ml, 0.4 mg/ml and 0.6 mg/ml were prepared by appropriate dilutions. Absorbance of those solutions at the λ

max 205 nm was measured which is close to the λ

max for CBD stated in [

36].

For the calibration curve, accurately weighed 3 mg of CBD was transferred to a vial of 1 ml deionized water solution. From this solution, other solutions with concentrations of different mg ml were obtained by diluting adequate amounts in triplicate. Five point’s calibration graphs were constructed covering concentration range of 33 –600 µg/ml. Three independent determinations were performed at each concentration. Linear relationships between the absorbance versus the corresponding drug concentration were observed and the absorbance – concentration equation was noted with determining the coefficient (r2).

3.8.2. In vitro Release Studies

The in vitro dissolution studies of the CBD/PMMA coatings were carried out using protocol mentioned in [

35]. The dissolution medium consisted of 100 ml of deionized water maintained at 25 ± 0.5°C. The CBD released at different time intervals was measured using a UV visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV–Vis 3600 , Columbia, USA). It was made clear that none of the coating compounds (PMMA, unreacted MMA) used in the coating formulations interfered with the absorbance of the CBD in water. The dissolution jars were cleaned with acetone and then rinsed with distilled water and dried to room temperature. 100 mL of dissolution medium (deionized water) was transferred into the dissolution jars and the coated discs were placed in the jars and static position was maintained. 3 mL of each sample was withdrawn at 12-hr intervals such as 0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, 96 and 108 hr using a graduated pipette and transferred to clean, dried and labeled test tubes. All the samples were then measured at 205 nm and their corresponding absorbance was noted. The cumulative percentage of released CBD was calculated using the given formulas as said in [

35]:

3.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with Prism Software version 8.3. The mean number of CFUs recultured from discs of PMMA and PMMA/CBD were compared by one-way ANOVA test. Comparisons between the control/solvent column with the different concentrations of CBD were also done using ANOVA multiple analysis. There was a significant difference between the values with CBD and no and the p- values were shown in the graphs. A p-value of < 0.05 was statistically significant. Graphs were created with GraphPad Prism 8.3.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA).

4. Conclusions

This investigation presents a pioneering approach for the development of antibiotic-free coatings, offering an alternative to conventional methods. Although attempts to copolymerize CBD with MMA have been ineffective, CBD was physically incorporated into PMMA coatings using UV curing. Analysis via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) indicated that, in addition to CBD concentration, reaction duration potentially influences the smoothness of the coating surface. Future research could be explored on the impact of curing time in CBD/PMMA synthesis, surface texture, and regular distribution.

Emphasis should be placed on crafting biofilm coatings capable of sustained release of antibiofilm agents. This sustained release will maintain effective concentrations of the CBD over an extended period, maximizing their ability to disrupt biofilms and eliminate bacteria within them. Future strategies to mitigate the burst effect could be optimizing formulation parameters such as adding modifiers, surfactants, or stabilizers to the formulation can influence the release kinetics by altering the solubility, diffusion, or interactions of CBD within the formulation. Implementing controlled release technologies such as microencapsulation, nanoparticles, liposomes, or hydrogels could be used to regulate the release of the CBD over time. These technologies can provide a barrier to fast diffusion or degradation, resulting in a sustained and controlled release profile. By carefully designing the delivery system, it's possible to minimize the initial burst release and achieve more predictable drug release kinetics.

In summary, biofilm studies showed PMMA/ CBD coatings were effective in eradicating all the pathogens on its surface. Antimicrobial studies showed CBD could not inhibit planktonic E. coli cells but was effective against E. coli biofilms. Further investigations on the genes expressions involved in biofilm maintenance, development, and maturation of factors associated with exopolysaccharide (EPS) synthesis and CBD could be studied to better understand its anti-biofilm mechanism. Other scopes of research could be CBD and its effect on the biosynthesis of fimbriae, surface proteins, virulence factor genes, and other bacterial structures involved in adherence to surfaces.

This study shows a novel pathway to develop an alternative to antibiotic filled coatings. CBD was successfully incorporated into the PMMA coatings using UV radiation and a photo initiator under N2. CBD loaded PMMA coatings showed strong anti- biofilm activities for both gram negative as well as gram positive, as confirmed by SEM and quantitative analyses of the surfaces. The addition of CBD in the coatings provided a 99 % reduction on S. aureus and E. coli biofilms, and a 99.99 % reduction on S. agalactiae biofilms. The CBD release analysis revealed a burst release for the first 12 h and was steady in release into the surrounding environment in vitro. The efficacy of such antimicrobial medicines in coatings is dependent on the antibiotic dissolving in fluids before absorption into the systemic circulation. The rate of CBD dissolution in the coating was consequently critical. In vitro, the data reveal that CBD molecules are released from the coatings quite effectively. This study showed that CBD can be incorporated into materials, enabling antibiotic-free dentures for preventing dental biofilms and reducing dental plaques.

Author Contributions

Kazi. N. Tahsin: Data curation, Writing, Statistical Analysis; William Z. Xu : Project administration, Data Characterization & Validation, Reviewing; David Watson : Microbiological Data Validation, Reviewing; Amin Rizkalla: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Chemical and Synthesis Data and Review; Paul Charpentier: Supervision, Funding acquisition , Resources for Chemical and Synthesis Data and Review.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Heinrichs Lab, Western University for providing us opportunity for collaboration and their support in providing the microbiological resources necessary for this study. We would like to thank Dr. David Heinrichs for his guidance, expertise, and access to laboratory facilities which has played a pivotal role in the successful completion of this work. Thanks to Surface Science Western, Biotron facility at Western University and Western Nano Fabrication facility for providing us the imaging assistance. This research was funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC). K.N.T was funded by Ontario Graduate Scholarships and Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology (QEII-GSST) Program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meirowitz, A.; Rahmanov, A.; Shlomo, E.; Zelikman, H.; Dolev, E.; Sterer, N. Effect of Denture Base Fabrication Technique on Candida Albicans Adhesion in Vitro. Materials 2021, 14, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Baik, A.; Almuzaini, S.A.; Farghal, A.E.; Alnazzawi, A.A.; Borzangy, S.; Aboalrejal, A.N.; AbdElaziz, M.H.; Mahmoud, I.I.; Zafar, M.S. Polymeric Denture Base Materials: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Phillips' science of dental materials; Anusavice, K.J., Shen, C., Rawls, H.R., Eds.; Elsevier Health Sciences, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Redfern, J.; Tosheva, L.; Malic, S.; Butcher, M.; Ramage, G.; Verran, J. The denture microbiome in health and disease: an exploration of a unique community. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2022, 75, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ng, W.-J.; Shit, C.-S.; Ee, K.-Y.; Chai, T.-T. Plant natural products for mitigation of antibiotic resistance. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 49: Mitigation of Antimicrobial Resistance Vol 2. Natural and Synthetic Approaches 2021, 2, 57–91. [Google Scholar]

- ElSohly, M.A.; Slade, D. Chemical Constituents of Marijuana: The Complex Mixture of Natural Cannabinoids. Life Sciences 2005, 78, 539–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathordoobady, F.; Singh, A.; Kitts, D.D.; Singh, A.P. Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L. ) Extract: Anti-Microbial Properties, Methods of Extraction, and Potential Oral Delivery.” Food Reviews International 2019, 35, 664–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.R.; Ali, D.W. Pharmacology of medical cannabis. Recent advances in cannabinoid physiology and pathology 2019, 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Anastassov, G.; Lekhram, C. Oral Care Composition Comprising Cannabinoids. US20190076349, US10172786, EP3233021, EP3233021, WO2016/100516, US20160166498. U.S. Patent 15 December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Xin, T.; Chaohui, Y.; Meng, L.; Tanran, C.; Qian, J. Use of the Tooth Whitening CBD. CN109939012. China Patent 12 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Xin, T.; Chaohui, Y.; Meng, L.; Tanran, C.; Qian, J. Composition Comprising a Cannabinoid Toothpaste and its Preparation Method. CN109939011. China Patent 20 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Curatola, G.P. Oral Care Formulations and Methods for Use. WO2019/055420, US20190076343. U.S. Patent. 14 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, V. Cannabis and Derivatives Thereof for the Treatment of Pain and Inflammation Related with Dental Pulp and Bone Regeneration Related to Dental Jawbone Defects. WO2019030762A2, EP3664795A2, US20200222361A1. U.S. Patent. 361 USA 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Xin, T.; Zhaohui, Y.; Meng, L.; Calm, C.; Qian, J. A kind of Toothpaste and Preparation Method Thereof Containing Cannabinoid. CN109939011A. China Patent 28 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, Z.; Xin, T.; Zhaohui, Y.; Meng, L.; Calm, C.; Qian, J. Application of the Cannabidiol in Tooth Whitening. CN109939012A. China Patent 28 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yunpeng, L.; Shuangqing, Z.; Zhipeng, L. A Kind of Toothpaste and Preparation Method Thereof with Sterilization, Anti-inflammatory and Analgesic Efficacy. CN109925246A. China Patent 25 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tumey, D.M.; Panahi, H. Cannabinoid-Infused Post-Operative Dental Dressing. US20200163746A1. U.S. Patent 6 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitouni, D.B.; Eyal, A.M. Dental Care Cannabis Device and Use Thereof. WO2019239357A1. U.S. Patent 12 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Haiyan, X.; Wei, H.; Meilian, X.; Zhijiang, H.; Xiao, K.; Xiao, H.; Lingyu, X. Cannabinoid-Containing Functional Toothpaste. ChinaPatent. CN111671698A 5 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.; Fengsha, X.; Lianmengm, G.; Tanran, C.; Ruyan, L.; Qingzhong, L. Oral Care Composition and Application Thereof. CN111973480A. China Patent 30 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Crisler, M.; Diponio, E.; Kennedy, P.J. Compositions for Preventing and Treating Viral Infections. WO2020257588A1. U.S. Patent 19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, V.; Vasudevan, K. Comparison of efficacy of cannabinoids versus commercial oral care products in reducing bacterial content from dental plaque: A preliminary observation. Cureus [Preprint] 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskis, P.T. U.S. Patent No. 9,895,404; U.S. Patent and Trademark Office: Washington, DC, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baldino, L.; Scognamiglio, M.; Reverchon, E. Supercritical fluid technologies applied to the extraction of compounds of industrial interest from Cannabis sativa L. and to their pharmaceutical formulations: A review. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2020, 165, 104960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthlott, I.; Scharinger, A.; Golombek, P.; Kuballa, T.; Lachenmeier, D. A Quantitative 1H NMR Method for Screening Cannabinoids in CBD Oils. Toxics 2021, 9, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heatley, N.G. A Method for the Assay of Penicillin. Biochemical Journal 1944, 38, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabski, M.; Węgierek-Ciuk, A.; Czerwonka, G.; Lankoff, A.; Kaca, W. Effects of Saponins against ClinicalE. ColiStrains and Eukaryotic Cell Line. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology 2012, 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Klingeren, B.; Ten Ham, M. Antibacterial activity of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 1976, 42, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskovich, M.A.T.; Kavanagh, A.M.; Elliott, A.G.; et al. The antimicrobial potential of cannabidiol. Commun Biol 2021, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, G.D.; Simpson, W.A.; Bisno, A.L.; Beachey, E.H. Adherence of Slime-Producing Strains of Staphylococcus Epidermidis to Smooth Surfaces. Infection and Immunity 1982, 37, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballén, V.; Cepas, V.; Ratia, C.; Gabasa, Y.; Soto, S.M. Clinical Escherichia Coli: From Biofilm Formation to New Antibiofilm Strategies. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, M.; Sionov, R.V.; Mechoulam, R.; Steinberg, D. Anti-Biofilm Activity of Cannabidiol against Candida Albicans. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.; Smoum, R.; Mechoulam, R.; Steinberg, D. Antimicrobial Potential of Endocannabinoid and Endocannabinoid-like Compounds against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. Scientific Reports 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesseract, A.C. Founder|Anandamide and CBD: The Correlation. Tesseract. Available online: https://insights.tessmed.com/anandamide-cbd-tsr/ (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Chandrasekaran, R.; Jia, C.; Theng, C.; Muniandy, T.; Muralidharan, S.; Dhanaraj, S. Invitro studies and evaluation of metformin marketed tablets-Malaysia. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science 2011, 1, 214–217. Available online: https://japsonline.com/bib_files/abstract.php?article_id=japs115.

- Ryu, B.R.; Islam, M.J.; Azad, M.O.K.; Go, E.-J.; Rahman, M.H.; Rana, M.S.; Lim, Y.-S.; Lim, J.-D. Conversion Characteristics of Some Major Cannabinoids from Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Raw Materials by New Rapid Simultaneous Analysis Method. Molecules 2021, 26, 4113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salarian, M.; Xu, W. Z.; Bohay, R.; Lui, E. M.; Charpentier, P. A. Angiogenic RG1/sr-doped tio2 nanowire/poly (propylene fumarate) bone cement composites. Macromolecular Bioscience 2016, 17, 1600156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming Yuan, Dayun Huang, Zefeng Wang, Xin Chen, Minghua Yang, Synthesis of ultra-high molecular weight poly(methyl methacrylate) with hydrosilane as initiator. Materials Today Communications 2022, 33, 104927. [CrossRef]

- Altieri, K.T.; et al. Effectiveness of two disinfectant solutions and microwave irradiation in disinfecting complete dentures contaminated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2012, 143, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Donnell, L.E.; Smith, K.; Williams, C.; Nile, C.J.; Lappin, D.F.; Bradshaw, D.; Lambert, M.; Robertson, D.P.; Bagg, J.; Hannah, V. , et al. Dentures are a Reservoir for respiratory pathogens. J Prosthodont. 2016, 25, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).