An Integrated Method for the Reconstruction of Renaissance Private Exhibition Rooms Camerini Starting from the Ippolito II d’Este’s Cabinet of Paintings at His Tiburtine Villa

This version is not peer-reviewed.

Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

A peer-reviewed article of this preprint also exists.

Abstract

This paper presents a new object of study: the so-called camerini, private rooms for study and reflection in the great stately palaces of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which contained riches and artistic heritage of inestimable value and were characterized by very dim lighting. The analysis of the camerini, true precursors of the modern museum, is not only a specific subject of study but also extremely relevant because it allows us to re-analyze the entire evolution of the museum type and its characteristics: discovering its origins, following its evolution, and critically reviewing its current features. Starting from the case study of the Quarto Camerino of the Villa d'Este in Tivoli, a superset of the specific features of this type of space and the possible problems in its 3D reconstruction, the article presents a method, and a workflow aimed at the reconstruction and visualization with high visual quality of these spaces and their features. Digital surveying technologies are integrated with advanced methods that allow the reproduction of the full optical properties of spatial surfaces and with tools for semantic modelling and visualization to generate a digital artefact that is consistent with the available information and its interpretations and that can be analyzed both perceptually and analytically.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State of the art

2.1. State of the art in the camerini reconstruction

2.2. State of the Art in the Architecture Historical Reconstruction

- -

- historical reconstruction source reliability

- -

- geometric and photometric.

- Historical Reconstruction Source Reliability 3D Model Quality Criteria

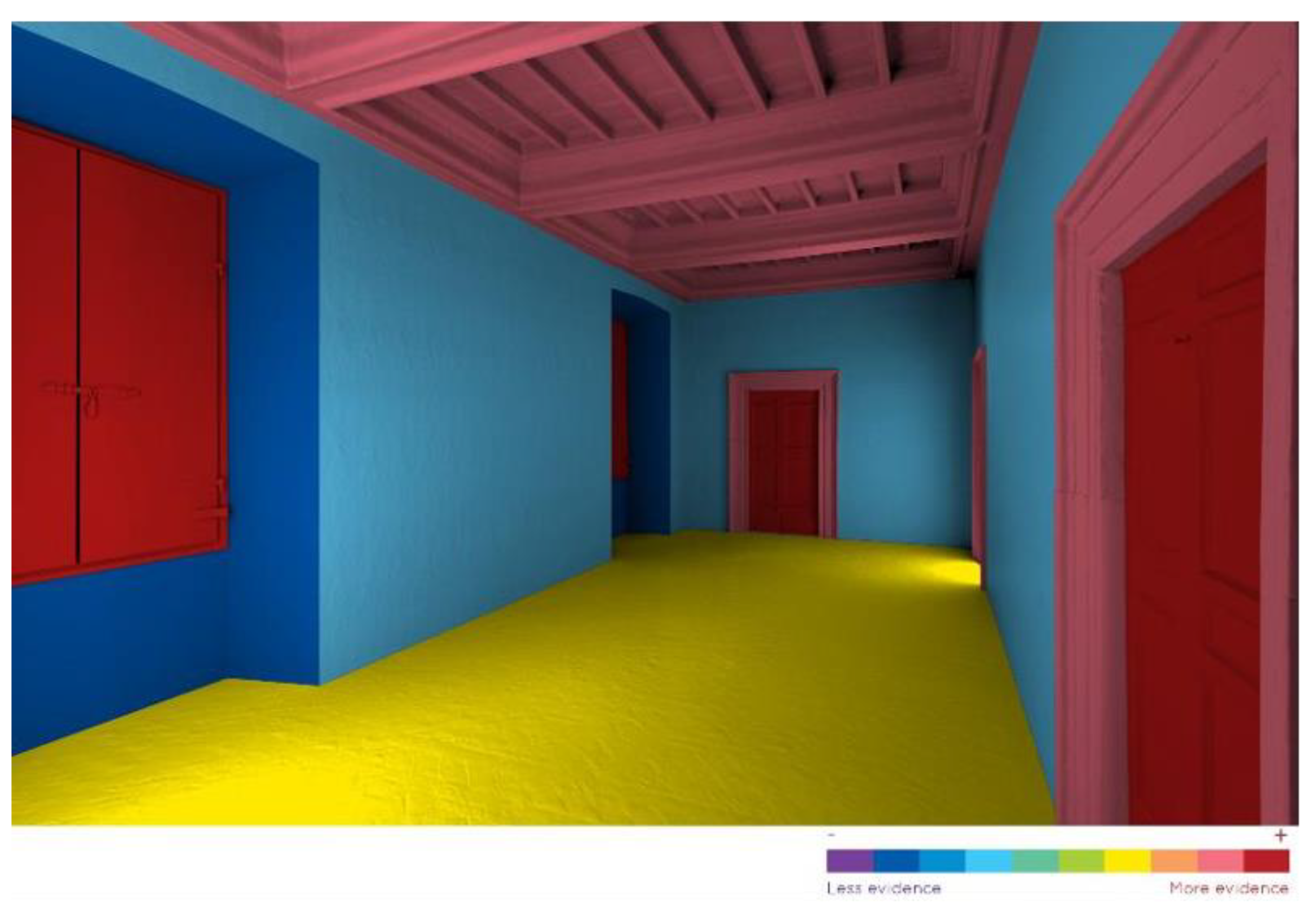

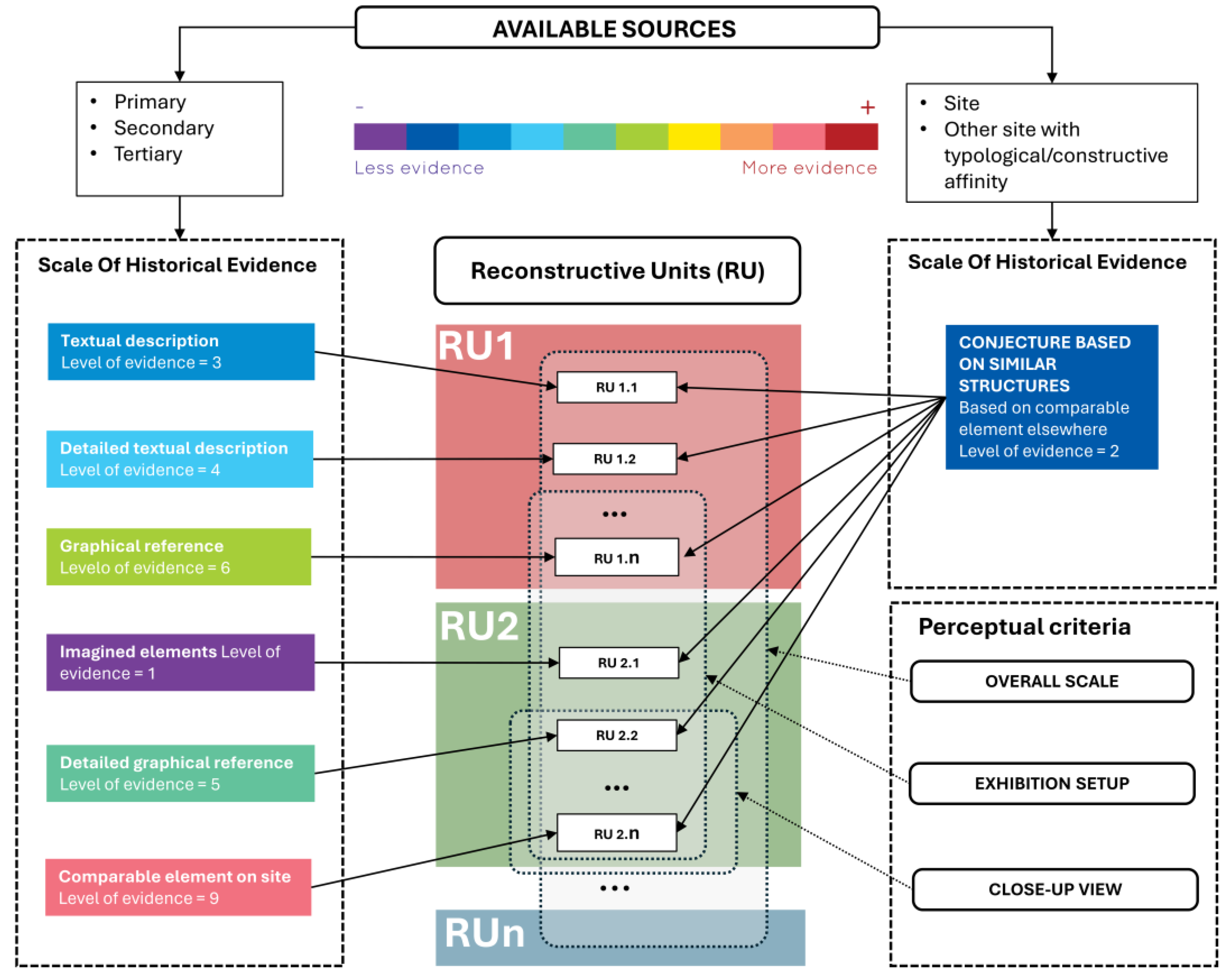

- Red: I am sure it exists because it is preserved;

- Orange: I am sure it existed because there is documentation about it;

- Blue: I am sure something existed, but I only know partial properties;

- Yellow: I am sure it existed, but I am not sure about its original position;

- Dark yellow: I am sure something existed, but I am not sure about its original position;

- Green: I believe it existed. My reconstruction is not based on in situ elements (all those parts for which we have no structural or archaeological evidence, but their reconstruction is entrusted to comparisons or interpreted sources).

- b.

- Geometric and Radiometric 3D Model Quality Criteria

3. Case study

4. Method Developed

5. Results

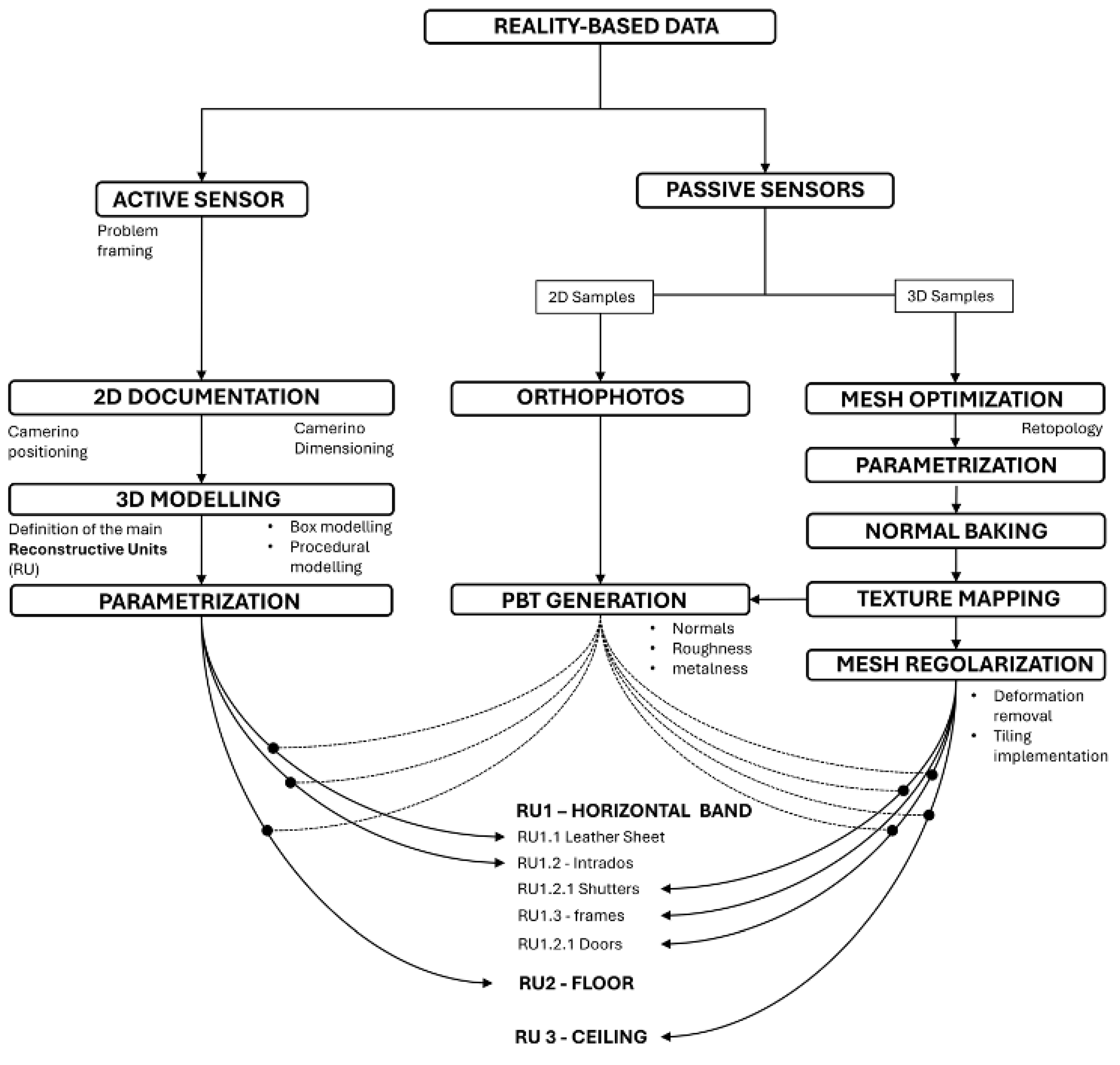

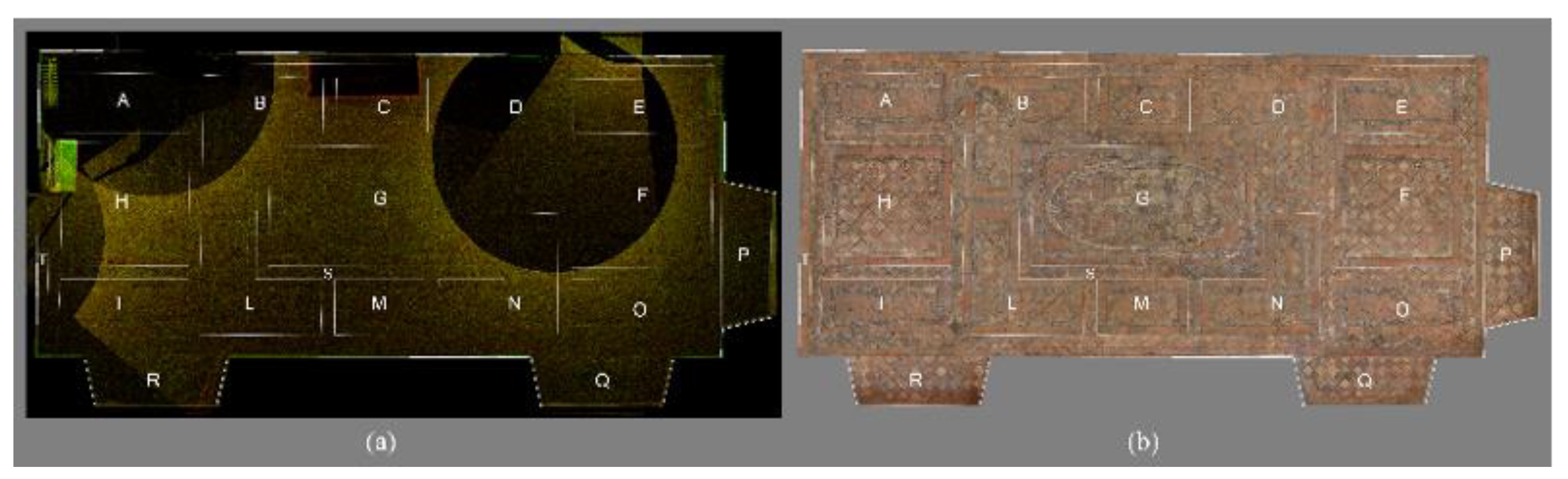

- Finding of the Quarto Camerino within Villa d'Este starting from the description of the goods in the I Inventarium bonorum bonae memoriae Hippoliti Estensis Cardinalis de Ferrara, Roma, 2 dicembre 1572, Archivio di Stato di Roma, Notai del tribunale A. C. , notaio Fausto Pirolo, vol. 6039,cc. 344r-387r. [42] through a joint visit to the site by all the professionals involved (in addition to the authors, the officials of Villa Adriana and Villa d'Este)

- check of the current consistency of spaces, find all spatial documentation related to them, measure them, and analyze transformations over time.

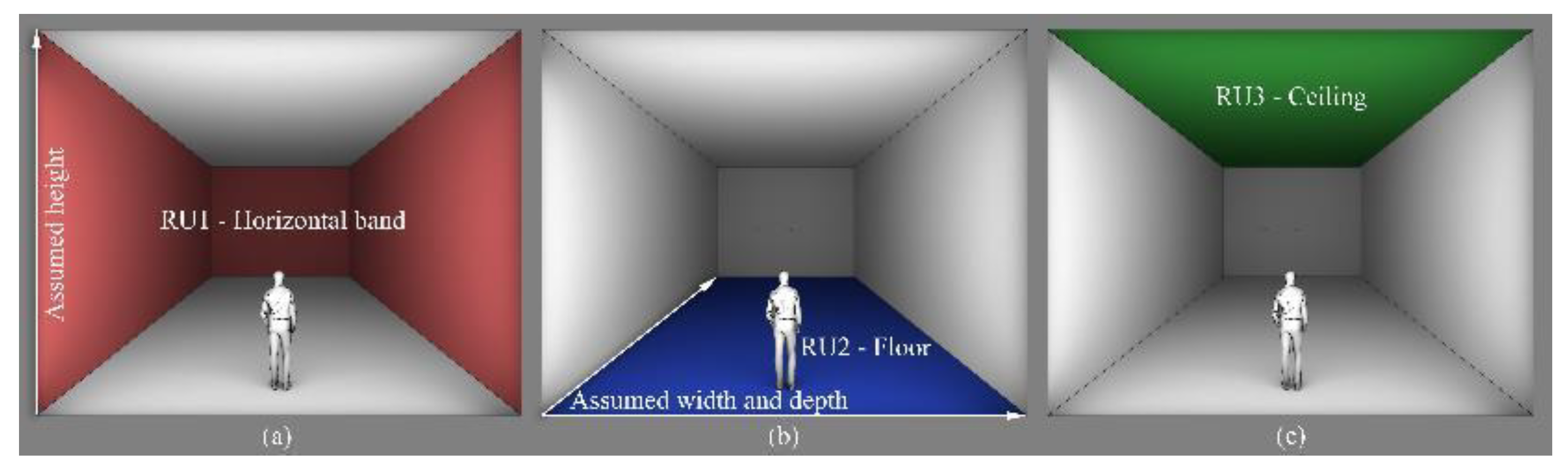

- reconstruction of the current state based on the elements still present, and reconstruction of the missing elements based on their degree of reliability

- geometric reconstruction

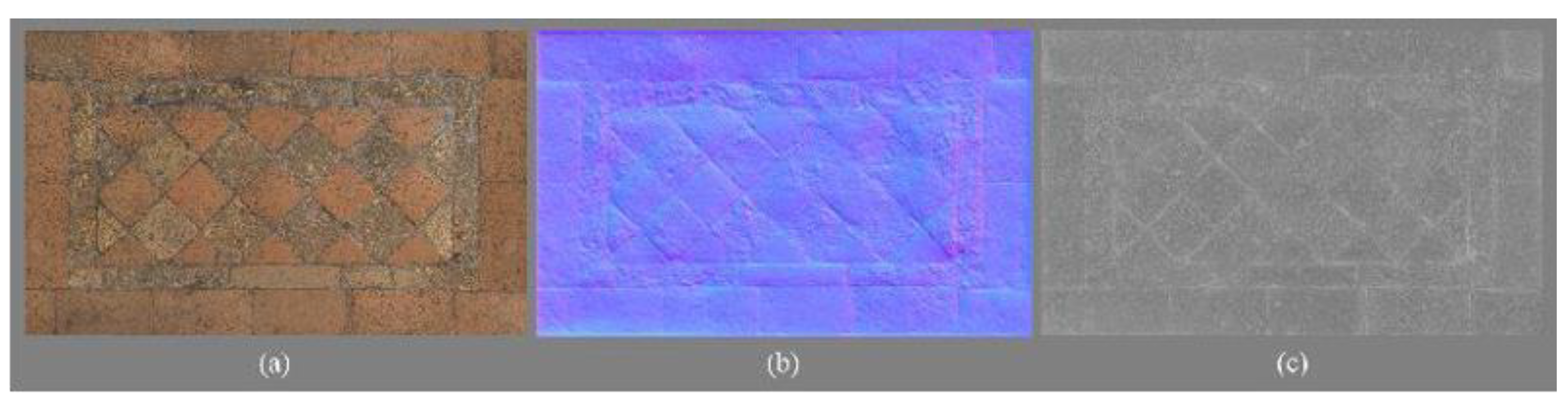

- CG reconstruction of surface properties

- perceptual analysis optimization

- lighting simulation.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Occhipinti, C.; I “camerini” rinascimentali e il progetto PRIN PNRR 2022 “dark vision experience”. Horti Hesperidum. Studi di storia del collezionismo e della storiografia artistica 2023, II.

- Agosti, B. Paolo Giovio. Uno storico lombardo nella cultura artistica del ’500, Olschki: Firenze, Italy, 2008.

- Barocchi P., Gaeta Bertelà P. Collezionismo mediceo e storia artistica, I: Da Cosimo I a Cosimo II, SPES: Firenze, Italy, 2002; pp. 15-16, 92 and passim.

- Longhi, R. Officina ferrarese (1934), Sansoni: Firenze, Italy, 1975; p. 25.

- Gundersheimer W.L. (Ed.), Art and Life at the Court of Ercole I d’Este: The «De Triumphis religionis» of Giovanni Sabadino degli Arienti, Libraire Droz: Ginevra, 1972, p. 72.

- Occhipinti, C. Carteggio d’arte degli ambasciatori estensi in Francia (1536-1553), Edizioni della Normale: Pisa, Italy, 2001; Occhipinti, C. Giardino delle Esperidi. Le tradizioni del mito e la storia della villa d’Este a Tivoli, Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani R; Serafini F. Lo studiolo virtuale di Urbino. In Matematica e Cultura, Hemmer M., Ed.; Springer: Milano, Italy, 2008; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Zambruno, S.; Urcia, A.; De Vivo, M.; Vazzana, A.; Iannucci, A. From Sources to Narratives: The role of Computer Graphics in Communicating Cultural Heritage Information. Journalism and Mass Communication 2017, 7, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo studiolo di Gubbio. Available online: https://framelab.unibo.it/lo-studiolo-di-gubbio/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Lo studiolo di Belfiore. Available online: https://framelab.unibo.it/lo-studiolo-di-belfiore/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Isabella Virtual Studiolo. Available online: https://ideastudiolo.hpc.cineca.it/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Apollonio, F.I. The Three- Dimensional Model as a ‘Scientific Fact’: The Scientific Methodology in Hypothetical Reconstruction. Heritage 2024, 7, 5413–5427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münster, S.; Apollonio, F.I.; Blümel, I.; Fallavollita, F.; Foschi, R.; Grellert, M.; Ioannides, M.; Jahn, P.H.; Kurdiovsky, R.; Kuroczynski, P.; Lutteroth, J.E.; Messemer, H.; Schelbert, G. Handbook of Digital 3D Reconstruction of Historical Architecture; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroczyński, P.; Pfarr-Harfst, M.; Münster, S. (Eds.) Der Modelle Tugend 2.0: Digitale 3D-Rekonstruktion als Virtueller Raum der Architekturhistorischen Forschung; Heidelberg University Press: Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Grellert, M.; Pfarr-Harfst, M. 25 Years of Virtual Reconstructions Project Report of Department Information and Communication Technology in Architecture at Technische Universität Darmstadt. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Cultural Heritage and New Technologies 2013. Available online: https://archiv.chnt.at/wp-content/uploads/Grellert_Pfarr-Harfst_2014.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2024). pp. 13.

- Münster, S. Workflows and the role of images for virtual 3D reconstruction of no longer extant historic objects. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci 2013, II-5/W1, 197–202.

- Rodríguez-Moreno, C. Depicting the Uncertain in Virtual Reconstructions of Architectural Heritage. In Graphic Horizons. EGA 2024; Hermida González, L., Xavier, J.P., Pernas Alonso, I., Losada Pérez, C., Eds, *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 120–127. [Google Scholar]

- Apollonio, F.I.; Fallavollita, F.; Foschi, R. The Critical Digital Model and Two Case Studies: the Churches of Santa Margherita and Santo Spirito in Bologna. Nexus Network Journal 2023, 25, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kensek, K. M.; Swartz Dodd, L.; Cipolla, N. Fantastic reconstructions or reconstructions of the fantastic? Tracking and presenting ambiguity, alternatives, and documentation in virtual worlds. Automation in Construction 2004, 13, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuk, T.; Carpendale, S.; Glanzman, W.D. Visualizing temporal uncertainty in 3D virtual reconstructions. In Proceedings of the 6th International conference on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Intelligent Cultural Heritage (VAST'05). Eurographics Association: Goslar, DEU; 2005; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, R.; Hermon, S. A London Charter's Visualization: The Ancient Hellenistic-Roman Theatre in Paphos. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium on Virtual Reality, Archaeology and Intelligent Cultural Heritage (VAST'11). Eurographics Association: Goslar, DEU; 2011; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Perlinska, M. Palette of possibilities: developing digital tools for displaying the uncertainty in the virtual archaeological “reconstruction” of the house, V 1,7 (Casa del Torello di Bronzo) in Pompeii. Master’s Thesis, in Classical Archeology and Ancient History, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdani, D.; Demetrescu, E.; Cavalieri, M.A.; Pace, G.; Lenzi, S. 3D Modelling and Visualization in Field Archaeology. Groma Documenting archaeology 2017, 4, 1–20, Demetrescu, E.; Fanini, B. A white-box framework to oversee archaeological virtual reconstructions in space and time: Methods and tools. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2017, 14, 500-514.. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio, P.; Figueiredo, C. El grado de evidencia histórico-arqueológica de las reconstrucciones virtuales: hacia una escala de representación gráfica. Revista Otarq: Otras arqueologías 2017, 235–247.

- Cáceres-Criado, I.; García-Molina, D.F.; Mesas-Carrascosa, FJ.; Triviño-Tarradas, P. Graphic representation of the degree of historical-archaeological evidence: the 3D reconstruction of the “Baker’s House”. Heritage Science 2022, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, G.; Russo, M.; Angheleddu, D. 3D survey and virtual reconstruction of archeological sites. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 2014, 1, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, F. I.; Gaiani, M.; Benedetti, B. 3D reality-based artefact models for the management of archaeological sites using 3D Gis: a framework starting from the case study of the Pompeii Archaeological area. Journal of Archaeological Science 2012, 39, 1271–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remondino, F. Heritage Recording and 3D Modeling with Photogrammetry and 3D Scanning. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 1104–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, F. I.; Ballabeni, A.; Gaiani, M.; Remondino, F. Evaluation of feature-based methods for automated network orientation, Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, XL-5, 47–54.

- Lerma, J.L.; Navarro, S.; Cabrelles, M.; Seguí, A.E.; Haddad, N.A.; Akasheh, T.S. Integration of Laser Scanning and Imagery for Photorealistic 3D Architectural Documentation. In Laser Scanning, Theory and Applications; InTech, 2011, 14534, pp. 20.

- Jakob, W.; Tarini, M.; Panozzo, D.; Sorkine-Hornung, O. Instant field-aligned meshes. ACM Trans. Graph. 2015, 34, 189–1-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.K.; Kobbelt, L.; Hu, S.M. Feature Aligned Quad Dominant Remeshing using Iterative Local Updates. Computer-Aided Design 2010, 42, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bent, G.R.; Pfaff, D.; Brooks, M.; Radpour, R.; Delaney, J. A practical workflow for the 3D reconstruction of com-plex historic sites and their decorative interiors: Florence As It Was and the church of Orsanmichele. Heritage Science 2022, 10, 118–1-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, R.; Tomé, A. Finding the Lost 16th-Century Monastery of Madre de Deus: A Pedagogical Approach to Virtual Reconstruction Research. Heritage 2023, 6, 6213–6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabellone, F.; Ferrari, I.; Giuri, F.; Chiffi, M. 3D Technologies for a Critical Reading and Philological Presentation of Ancient Contexts. Archeologia e Calcolatori 2017, 28, 591–595. [Google Scholar]

- Borghini, S.; Carlani, R. Virtual rebuilding of ancient architecture as a researching and communication tool for Cultural Heritage: aesthetic research and source management. DisegnareCon 2011, 4, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, L.; Fantini, F.; Bertacchi, S. El color en las piedras y en los mosaicos de Rávena: nuevas imágenes de los monumentos antiguos a través de la fotogrametría no convencional de última generación. EGA Expresión Gráfica Arquitectónica 2015, 20, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffer, A.; Praun, E.; Rose, K. Mesh Parameterization Methods and Their Applications. Foundations and Trends in Computer Graphics and Vision 2014, 2, 105–171, Cipriani, L.; Fantini, F.; Bertacchi, S. 3D models mapping optimization through an integrated parameterization approach: cases studies from Ravenna. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2014, XL-5; 173–180.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, A.; Policarpo, F. 3D Games: Real-time Rendering and Software Technology. Addison-Wesley: New York, NY, 2001, pp. 315, 346-348.

- Burley, B. Physically-based shading at Disney, course notes. In Proceedings of the SIGGRAPH '12 Courses, ACM: New York, NY, 2012, Article 10, pp. 1-27.

- Georgiev, I.; Portsmouth, J.; Andersson, Z.; Herubel, A.; King, A.; Ogaki, S.; Servant, F. Autodesk Standard Surface: reference implementations, 2019. Available online: https://github.com/Autodesk/standard-surface/blob/master/reference/.

- Occhipinti, C. Giardino delle Esperidi. Le tradizioni del mito e la storia di Villa d'Este a Tivoli, Carocci: Roma, 2009.

- De Luca, L.; Busayarat, C.; Stefani, C.; Véron, P.; Florenzano, M. A semantic-based platform for the digital analysis of architectural heritage. Computers & Graphics 2011, 35, 227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriani, L.; Fantini, F. Digitalization culture vs archaeological visualization: integration of pipelines and open issues, Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2017, XLII-2/W3, 195–202.

- Vaienti, B.; Apollonio, F.I.; Gaiani, M. Analysis of Leonardo da Vinci’s Architecture through Parametric Modeling: A Method for the Digital Reconstruction of the Centrally Planned Churches Depicted in Ms. B. Heritage 2020, 3, 1124–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, F., Gaiani, M., Garagnani, S. Knowledge and documentation of renaissance works of art: the replica of the “Annunciation” by Beato Angelico. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2023, XLVIII-M-2-2023, 527–534.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Downloads

37

Views

40

Comments

0

Subscription

Notify me about updates to this article or when a peer-reviewed version is published.

MDPI Initiatives

Important Links

© 2025 MDPI (Basel, Switzerland) unless otherwise stated