1. Introduction

Cervical cancer screening is critical for the early identification of pre-cancerous changes in cervical tissues, particularly in developing countries where healthcare resources are limited. To find aberrant cervical cells, methods including colposcopy, Papanicolaou (Pap) tests, and visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) are frequently employed. Automated screening systems can enhance early detection and reduce mortality rates [

1]. Colposcopy images are used to identify cervical lesions and classify them into various stages of pre-cancerous conditions. Deep learning models may greatly improve the categorization accuracy of colposcopy images, assisting physicians in making well-informed choices [

2]. Our study focuses on utilizing advanced neural network techniques for accurate classification. Deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are excessively used for image classification tasks due to their expertise to extract hierarchical features. In our study, we leverage CNNs to capture intricate patterns within colposcopy images, which can aid in the differentiation of cervical lesions. The architecture includes residual connections to enhance feature learning [

4].

Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks are used to revise channel-specific feature responses, allowing the model to focus on the most important channels. By amalgamating SE blocks into the CNN architecture, we enhance the model’s capability to emphasize critical features in colposcopy images, leading to improved classification performance [

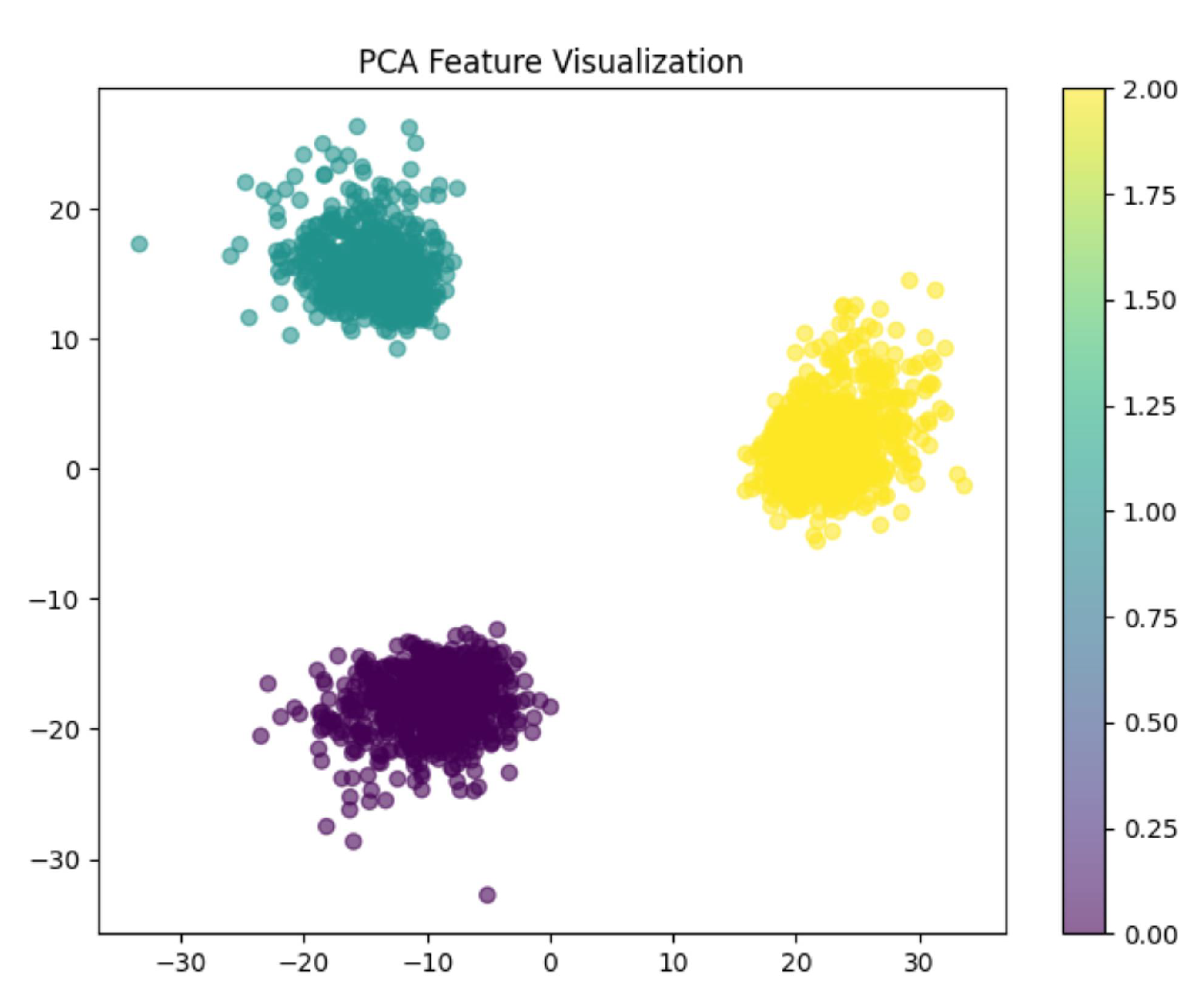

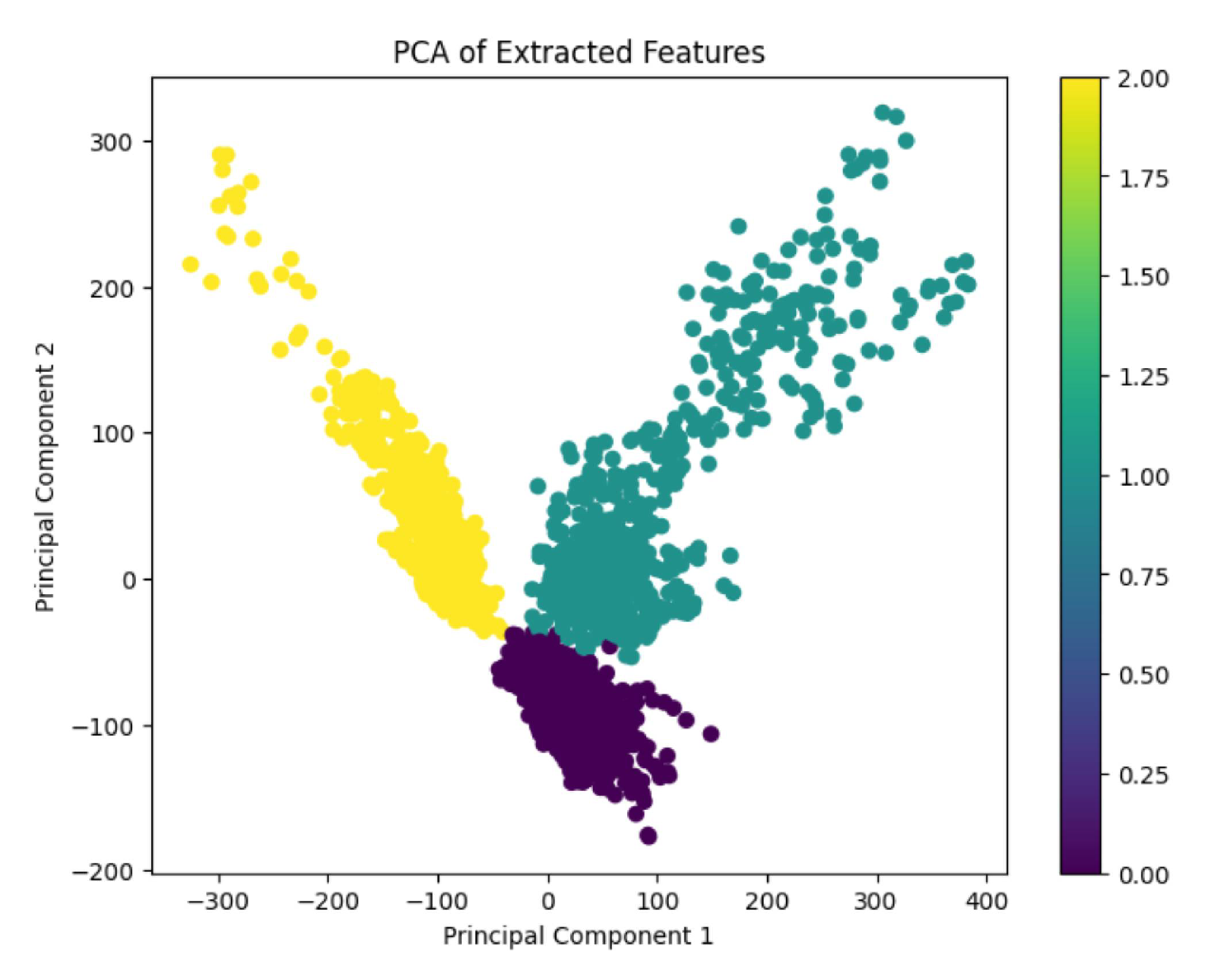

3]. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality reduction technique that may be used to project high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional environment. In our study, PCA is applied to visualize the feature representations learned by the model, helping to understand how well the model differentiates between classes [

5]. This also aids in optimizing model performance. Adjusting hyperparameters like learning rate, batch size, and dropout rate is necessary to maximize model performance. In our research, extensive hyperparameter tuning led to a significant improvement in both training and validation accuracies, enhancing the robustness of the colposcopy image classification model [

6].

In this study, we address the critical need for accurate cervical cancer screening to detect early signs of precancerous changes, enabling timely treatment and potentially preventing the development of cervical cancer. The goal is to classify cervical lesions using colposcopy images as CIN1 (represents low-grade, mild changes in cervical cells), CIN2 (indicates moderate abnormal cell growth around the cervix), and CIN3 (considered a pre-cancerous condition with a higher risk of developing into invasive cervical cancer if untreated). To achieve this, we developed a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) for feature extraction, integrated with squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks and residual connections to improve the flow of information, ensuring more accurate classification. Hyperparameter fine-tuning and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) were applied to optimize performance. Grad-CAM visualizations were employed to interpret the model’s focus areas, while ROC-AUC analysis demonstrated the model’s robustness. The fundamental focus of this study is the integration of SE blocks and residual learning in a CNN for cervical lesion classification, showcasing its potential as a decision support tool in early cancer detection. Based on the contribution of this study, the objective of the paper can be summarized as:

For the categorization of colposcopy images, an extremely deep convolutional neural network combined with a squeeze-and-excitation block and a residual link is suggested.

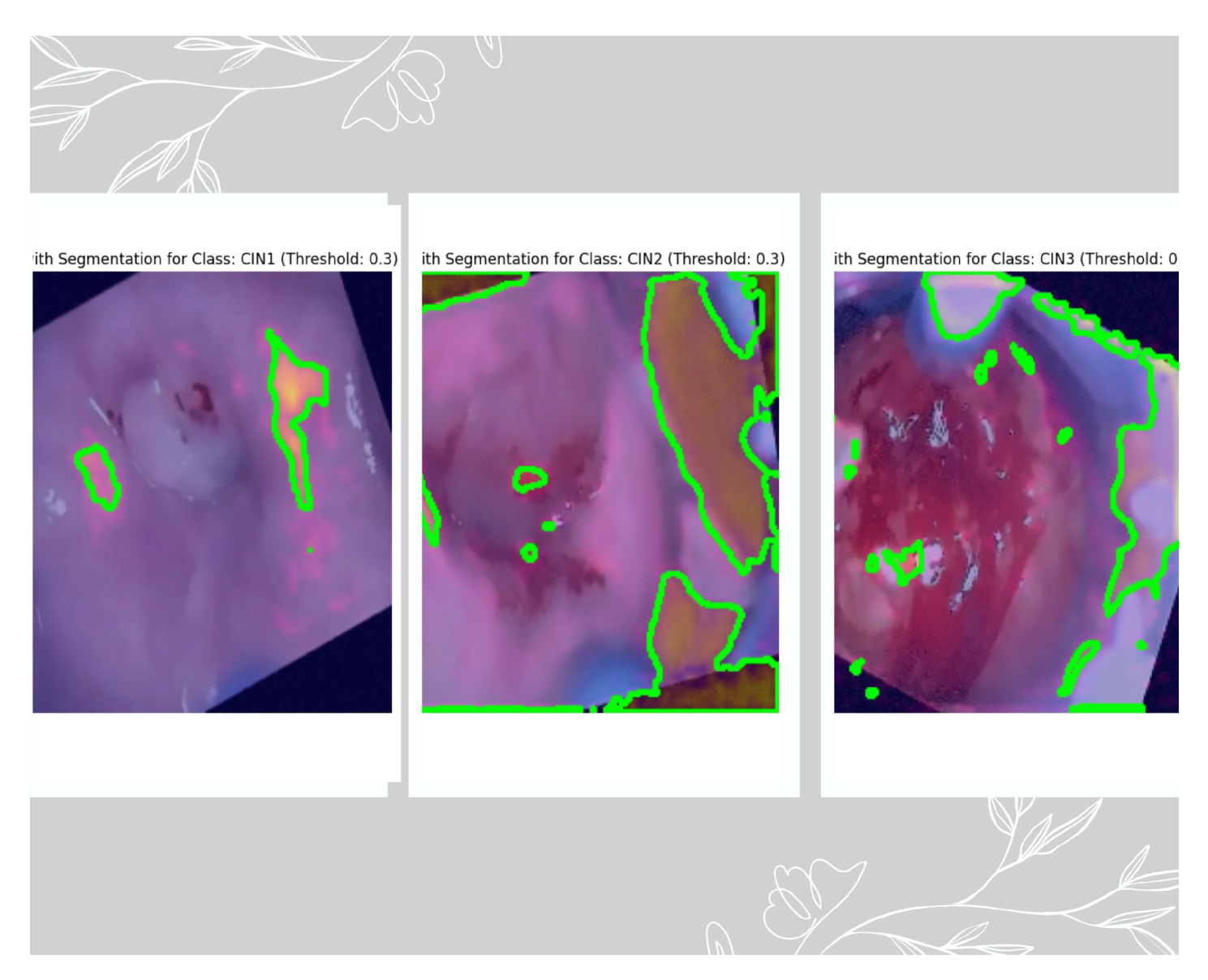

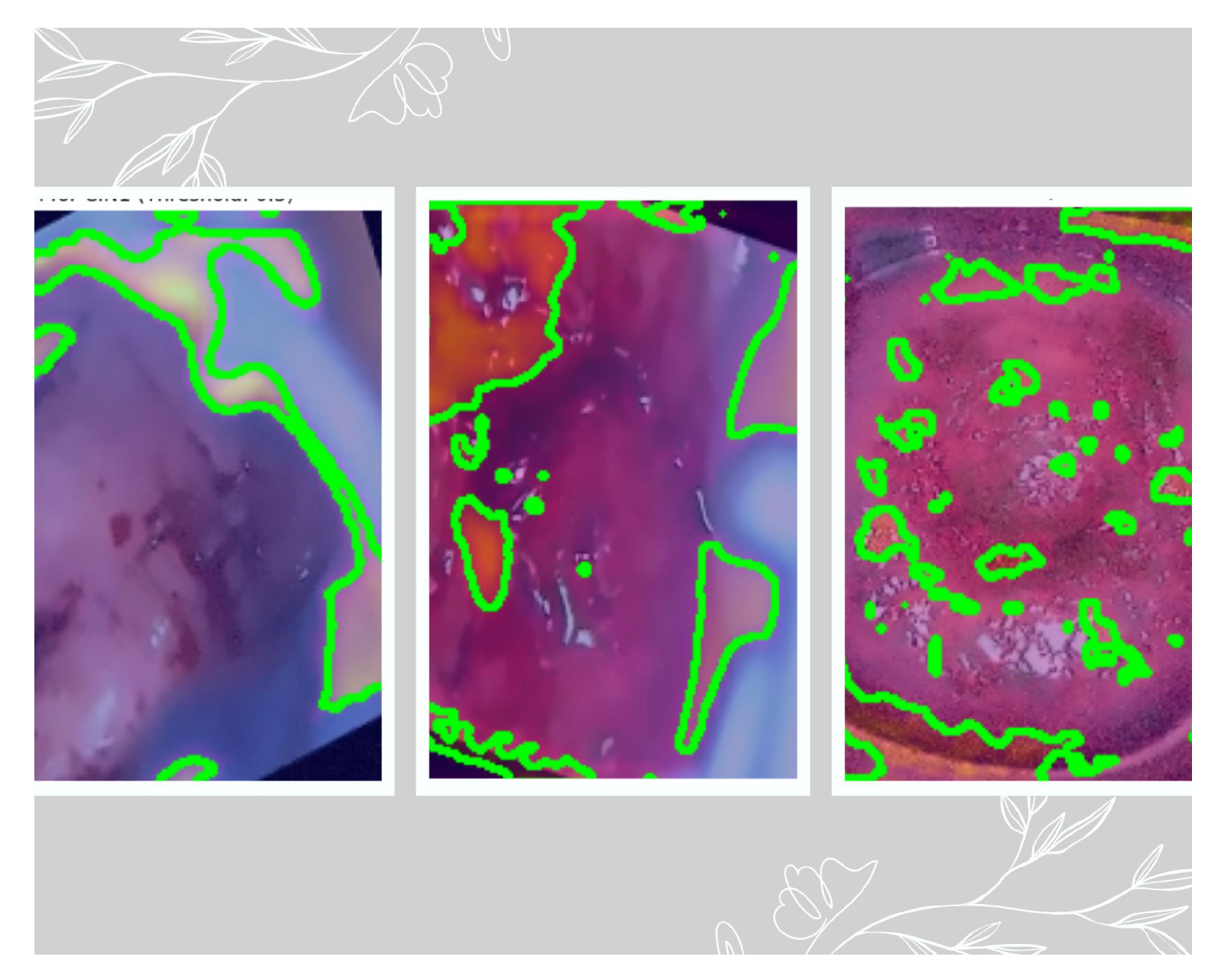

Grad-CAM visualization is used for highlighting areas of the cervix that were most influential in classifying a lesion as cancerous and also ensuring that the model is focusing on clinically relevant areas, rather than being biased by artifacts or irrelevant features in the image.

Hyperparameter fine-tuning and PCA are employed together to enhance the model’s ability to accurately classify colposcopy images, making the system more reliable for early detection of cervical abnormalities.

Validated the model’s performance on images captured in multiple solutions and on an independent dataset to confirm reliability and adaptability in clinical applications.

Used GradCam++ for network visualization.

This paper is structured as follows:

Section 1 provides an overview of the study, outlining the goals and driving forces. The literature review is presented in

Section 2. The materials and techniques are covered in

Section 3, where we talk about the deep neural network combined with a residual connection and a squeeze-and-excitation block.

Section 4 describes the model’s implementation, the Grad-CAM display, and the hyperparameter twining procedure using principal component analysis. The model’s findings and outcomes are shown in

Section 5. The results are thoroughly discussed in

Section 6. Lastly,

Section 7 brings the paper to a close.

2. Literature Review

Early detection is crucial to lowering the incidence and death of cervical cancer, which presents a significant public health concern [

7]. This section will provide a extensive overview and critical analysis of current literature on the techniques of classification of the types of cervical cancer. By reviewing existing research in this area, we seek to uncover gaps and limitations in the knowledge base and underscore the potential impact of our study in addressing these issues, contributing valuable insights to this pressing public health concern.

An ensemble of MobileNetV2 networks has been employed by Buiu, Nicoleta, et al. According to experimental data, this method is successful in differentiating between different types of lesions, achieving classification accuracies of 91.66% for the binary classification job and 83.33% for the four-class task [

8]. Joo, Choi, et al. have used pre-trained convolutional neural network fine tuned for two grading system and the multi class accuracies were noted for the two grading system [

9]. Mansouri, Ragab, et al.has used EOEL-PCLCCI for cervical cancer classification with a classification accuracy of 99.17% [

10]. For feature extraction, Kalbhor, Shinde, et al. have employed a Gray-level run length matrix, a Gray-level co-occurrence matrix, and a gradient histogram. The features are combined using GLCM, GLRLM, and HOG to create a fusion vector. The data is then classified using a variety of machine learning classifiers that use both individual feature vectors and the composite feature fusion vector [

11].

Pavlov, Fyodorov, et al. have introduced a simplified CNN classifier for colposcopic images. The classification accuracies achieved for each class were as follows: 95.46% for normal, 79.78% for LSIL, 94.16% for HSIL, and 97.09% for suspicious for invasion [

12]. Cervigram-based recurrent convolutional neural networks (C-RCNNs) have been utilized by Yue, Ding, et al. to categorize cervical cancer and various CIN grades. 96.13% test accuracy was noted [

13]. Chen, Liu, et al. created the a hybrid model, which combines convolutional neural networks with a transformer, to aggregate the correlation between global and local information. The accuracy was 89.2% [

14]. A deep learning-based approach for the diagnosis and classification of cervical lesions has been proposed by Luo, Zhang, et al. utilizing multi-CNN decision feature integration. The accuracy observed was 83.5% for inner-to-outer and 81.19% for outer-to-inner MDFI strategy [

15].

Pal, XUE, et al. have used three popular deep neural networks (ResNet-50, MobileNet, NasNet) are integrated with deep metric learning based framework to produce class-separated image feature descriptors. The DML algorithm was trained over batch- hard loss, N-Pair embedding, contrastive, fine-tuned and pre-tuned. The accuracy was observed for classes case and controlled with respect to the three deep neural networks [

16]. Adweb, Cavus, et al. has used very deep residual network over different activation functions claiming an accuracy of 100% [

17]. Using hybrids of pre-trained convolutional neural networks, machine learning, and deep learning classifiers like KNN and SVM, as well as creative multimodal architectures of merged CNN-LSTM hybrids, Bappi, Rony, et al. classify 26 different forms of cancer. Both main cancer classifications and subclass classifications show 99.25% and 97.80% classification accuracy, respectively [

18].

In order to reach an accuracy of 95.685%, Fang, Lei, and colleagues presented DeepCELL, a deep convolutional neural network with learnt feature representations that use several kernels of varying sizes [

19]. Devarajan, Alex, et al. have addressed the issue of reliable cervical cancer diagnosis by combining an artificial neural network (ANN) with a meta-heuristic known as the artificial Jellyfish search optimizer (JS) method. 98.87% is the observed classification accuracy [

20]. For the final level prediction of CAD-based models, Sahoo, Saha, et al. suggest a unique fuzzy rank-based ensemble that takes into account two non-linear factors. The classification accuracy of the suggested ensemble architecture is 97.18% [

21]. To attain the highest accuracy, Kang, Li, et al. apply the CerviSegNet-DistillPlus model pruning and increased cutting-edge knowledge distillation in the DeepLabV3+ architecture [

22]. He, Liu, et al. introduces the

Net architecture, which enhances image segmentation through feature refinement and upsampling connections. The accuracy observed is 94.58% [

23]. Chen, Feng, et al. created a novel feature improvement method that records data from both local and global viewpoints. They also suggest a new discriminative architecture called CervixNet that combines a Local Bin Excitation (LBE) module with a Global Class Activation (GCA) module. Extensive tests on 9,888 clinical colposcopic pictures show the method’s efficacy, showing its superiority over current techniques and obtaining an AP.75 score of 20.45 [

24]. Muksimova, Umirzakova, et al. proposes a RL-CancerNet, an artificial intelligence model integrated with EfficientNetV2, Vision Transformers, and Reinforcement Learning to prioritize rare yet critical features indicative of early-stage cancer. RL-CancerNet demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving an accuracy of 99.7% [

25]. Chen, Lo, et al. does a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy of MRI in the staging of cervical cancer [

26]. Lorencin, Lorencin, et al. proposes a technique that manages the class imbalance of the dataset using techniques such as Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique, ADASYN, SMOTEEN, random oversampling, and SMOTETOMEK. Logistic regression, support vector machines (SVM) multilayer perceptrons (MLP), naive Bayes, and K-nearest neighbors (KNN) classifiers were among the artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques used for classification. The highest performance was observed when MLP and KNN were combined with random oversampling, SMOTEEN, and SMOTETOMEK, achieving mean AUC and MCC scores above 0.95 across different diagnostic methods [

27]. For automatic feature extraction, Alquran et al. suggested a network that created 544 features by fusing pre-trained CNNs with a unique Cervical Net structure. Key discriminant characteristics were found across five Pap smear picture classes by dimensionality reduction using Principal Component Analysis and Canonical Correlation Analysis. Utilizing a Support Vector Machine (SVM), the method combined characteristics from Cervical Net and Shuffle Net to reach an astounding 99.1% accuracy [

28]. Tang, Zhang, et al. suggest a highly accurate cervical cancer precancerous lesion screening classification system based on ConvNeXt using self-supervised data enhancement and ensemble learning techniques. This method extracts features of cervical cancer cells and discriminates between classes, accordingly [

29]. Hong, Xiong, et al. proposes an unique digital pathological classification method, combining Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) with the Vision Transformer (ViT) model. This approach aims to enhance the efficiency of cervix type classification by utilizing a deep learning classifier that achieves high accuracy with a reduced need for large datasets [

30].

These advancements highlight the significant future of deep learning in revolutionizing medical imaging, while also setting the stage for future research aimed at optimizing neural networks to achieve even greater diagnostic accuracy. Additionally, they provide new opportunities to incorporate advancements in machine learning to improve the results of patient care.

2.1. Gaps Identified and Corrective Measures Taken

Through extensive research, we identified several gaps that our proposed method aims to address. We selected approaches that could be implemented on our primary dataset.

Table 1 outlines these identified gaps, the existing methods, and the corrective measures suggested by our proposed approach.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

We have received a total of 918 images of CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3 positive images from the International Agency for Research on Cancer [

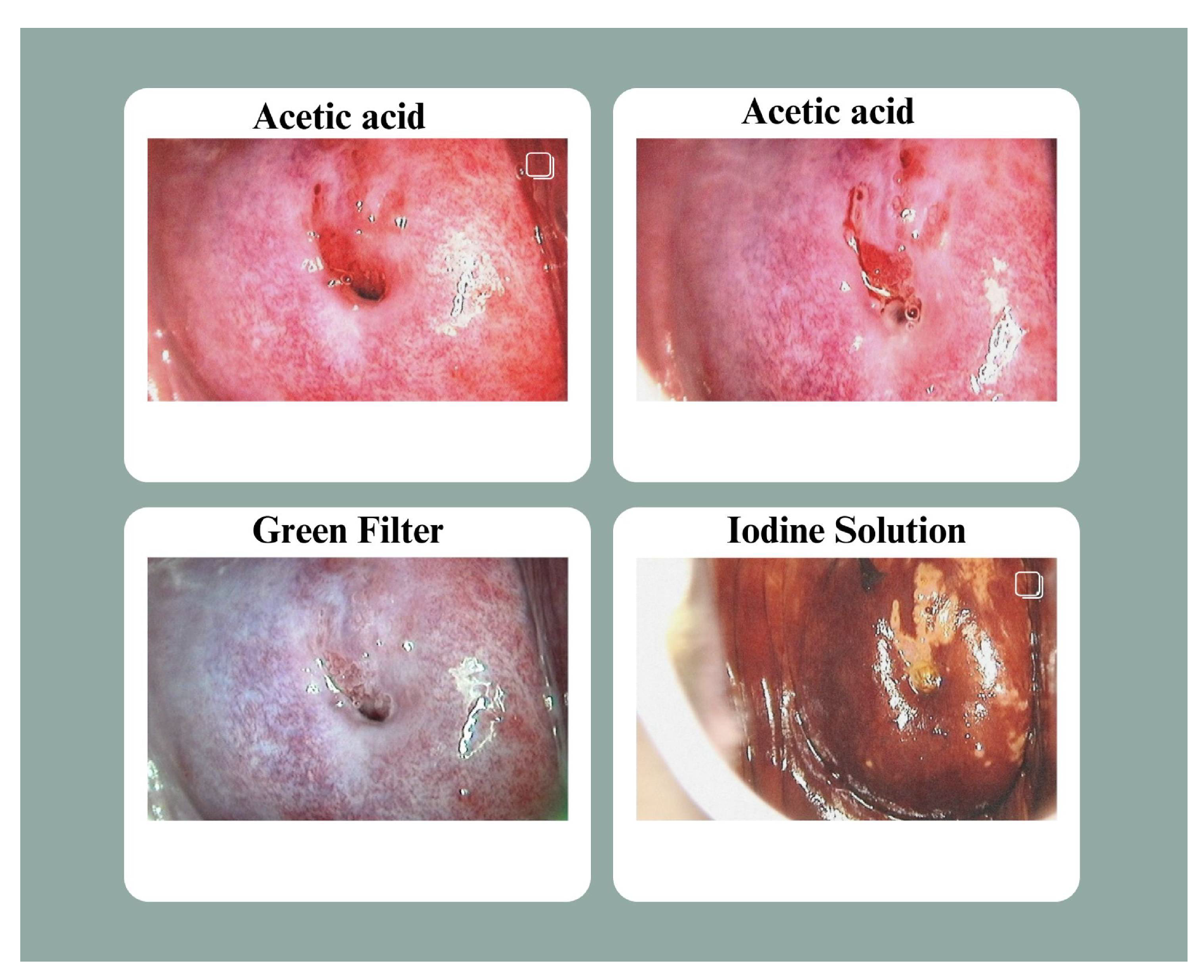

36] captured in three different solutions: Lugol’s iodine, acetic acid, and normal saline. We considered the images captured in acetic acid, as acetic acid helps doctors better visualize the abnormal regions. So we had a total of 860 images of acetic acid. Employing acetic acid solution, the region of interests becomes white. For each medical examination, three sequential images are taken: one of the cervix after applying an acetic acid solution, one of the cervix via a green filter, and a third image of the cervix after applying a dark red iodine solution. As shown in

Figure 1, the pictures are organized as follows: the two pictures with the acetic acid application come first, followed by the picture via the green filter and the picture with the iodine solution. The dataset was arranged so that this sequence was preserved inside each folder when the picture files were sorted alphabetically. The files were renamed to reflect the right sorting in a few cases where this order was not initially maintained. The data were classified into three categories, CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3. We are referring this data as our primary dataset. We have denoised and augmented this dataset. Apart from this we have also used a secondary dataset, the Malhari dataset [

37] which is licensed under public domain containing a total of 2,790 images. The proposed model can handle a larger dataset also.

3.1.1. Primary Dataset

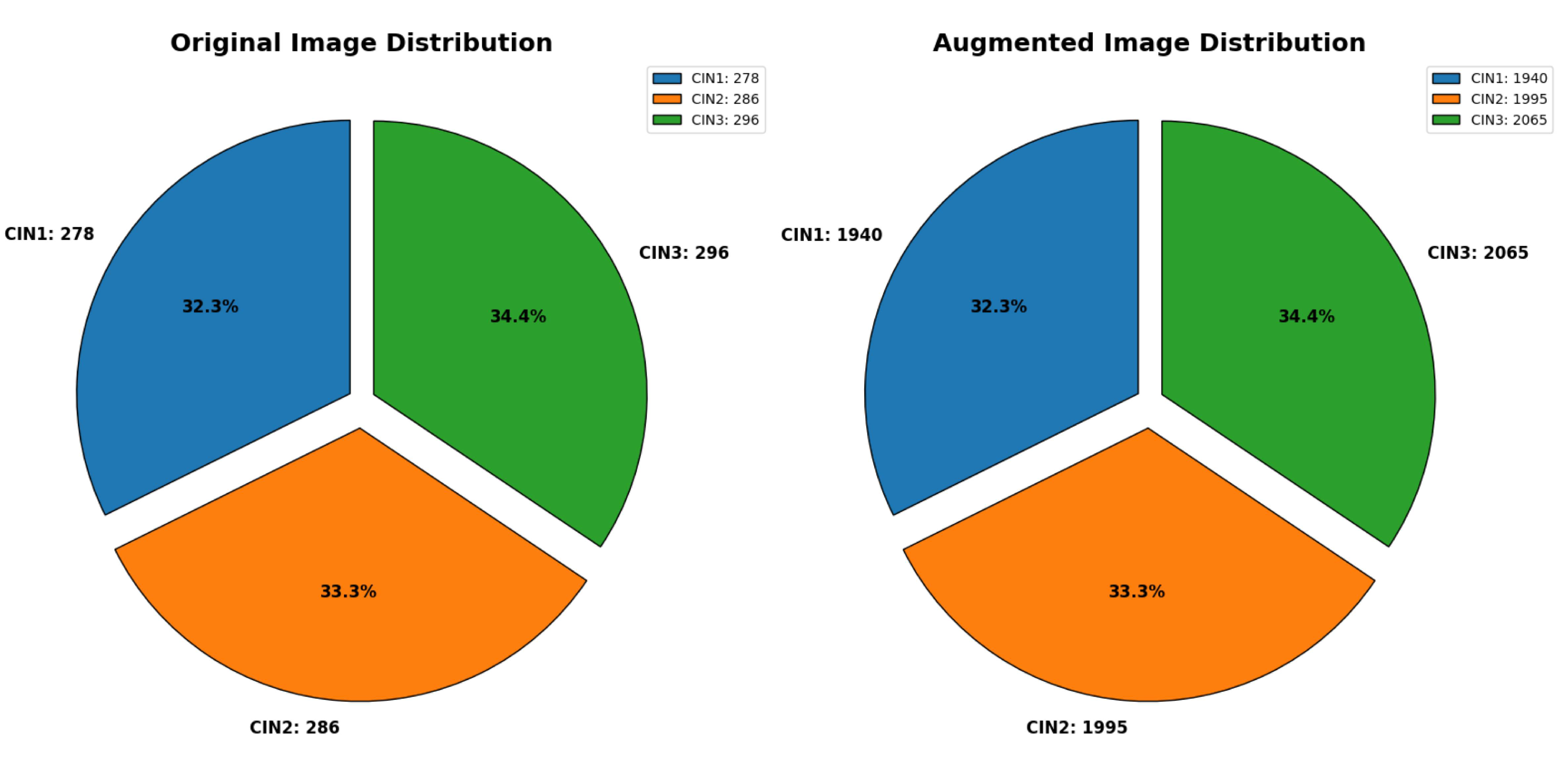

A total of 860 images were used containing 278 CIN1 images, 286 CIN2 images, and 296 CIN3 images were augmented to 1940 for CIN1, 1995 for CIN2 and 2065 for CIN3. We have used a separate directory to store 6,000 augmented images. The data distribution of the primary dataset, which solely includes images of acetic acid solution, is displayed in

Figure 2.

3.1.2. Secondary Dataset

We have acquired the secondary dataset from Kaggle named as Malhari [

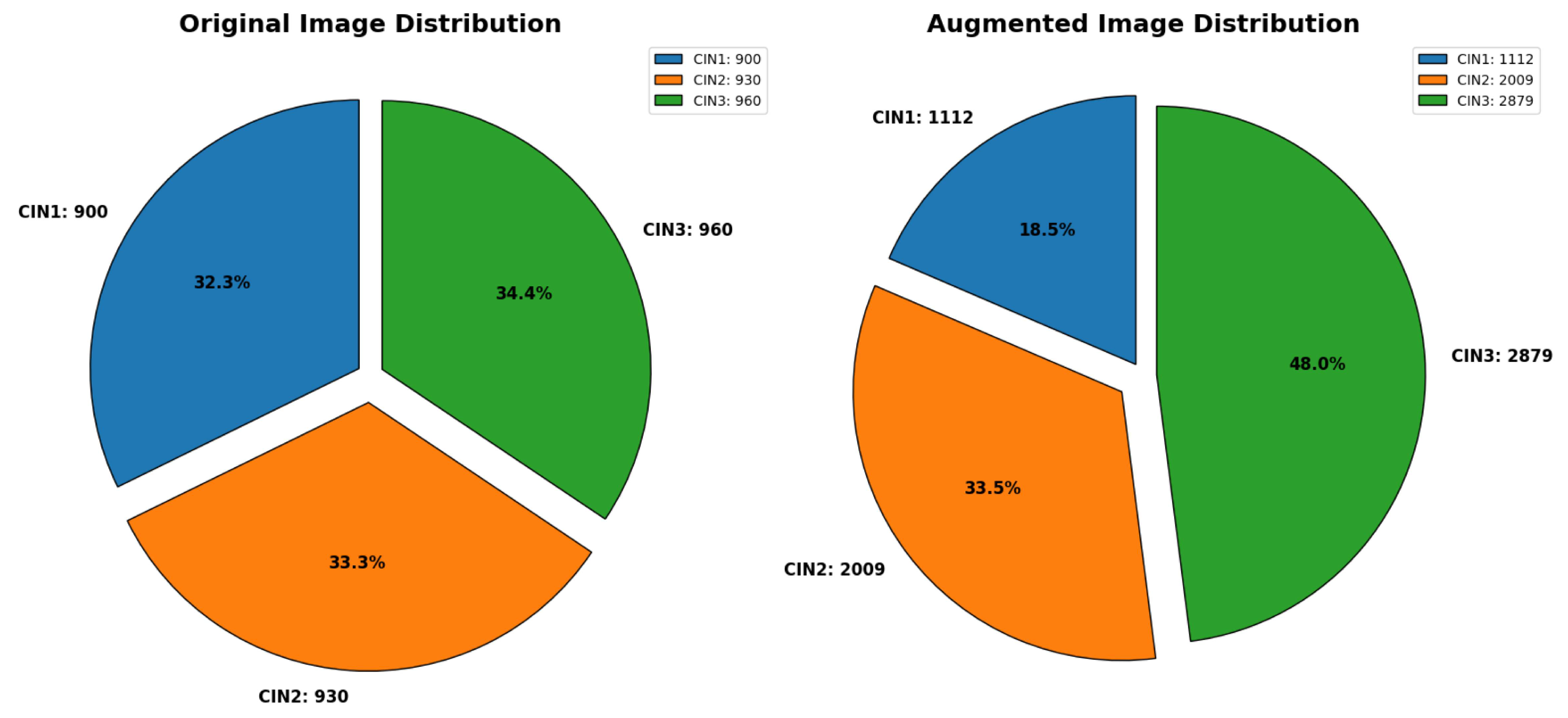

37] containing 2,790 images. This dataset also had images captured in three different solutions: Lugol’s iodine, acetic acid and normal saline. In the original dataset, CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3 were distributed as follows: 900, 930, and 960, respectively. The distribution of the three classes in the augmented dataset is 1112 for CIN1, 2009 for CIN2 and 2879 for CIN3. We have considered images under all the three solutions for validating our model’s performance. This dataset was also denoised and augmented to 6,000 images.

Figure 3 depicts the data distribution of this secondary dataset class wise. Though there is a class imbalance in the augmented dataset, as we are using this dataset for validating our model’s performance, we have just used PCA and not any other technique to handle class imbalance.

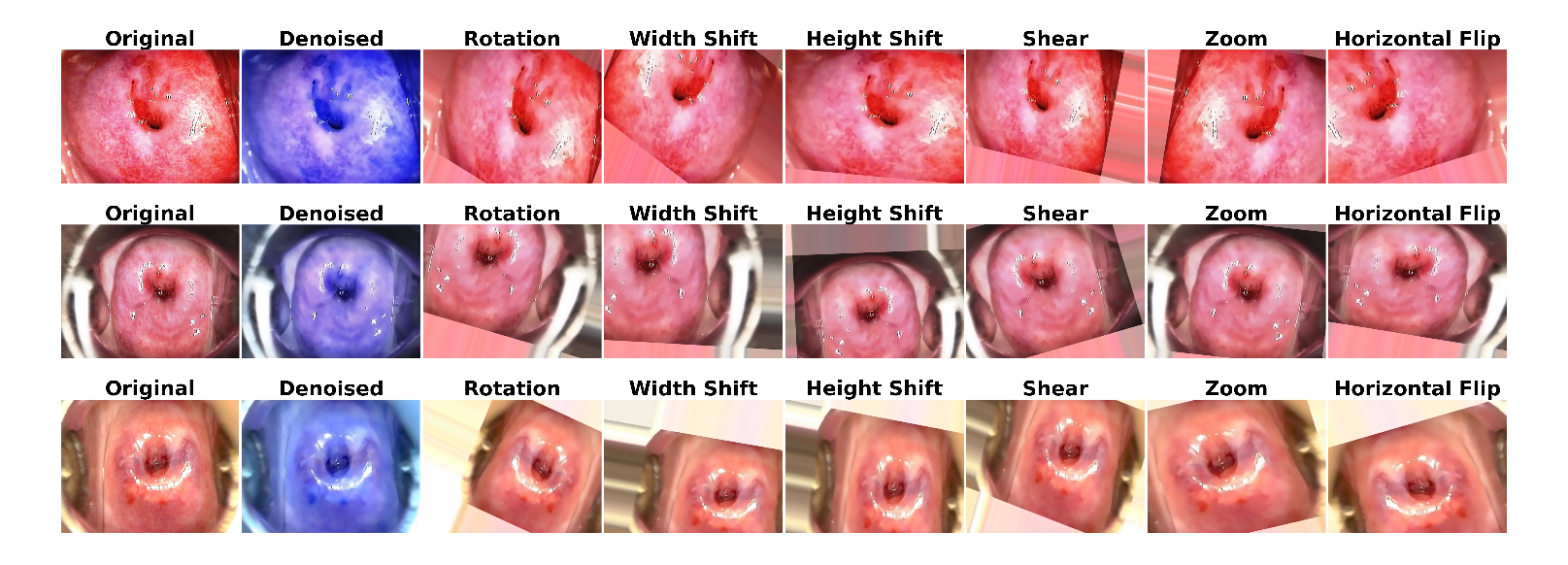

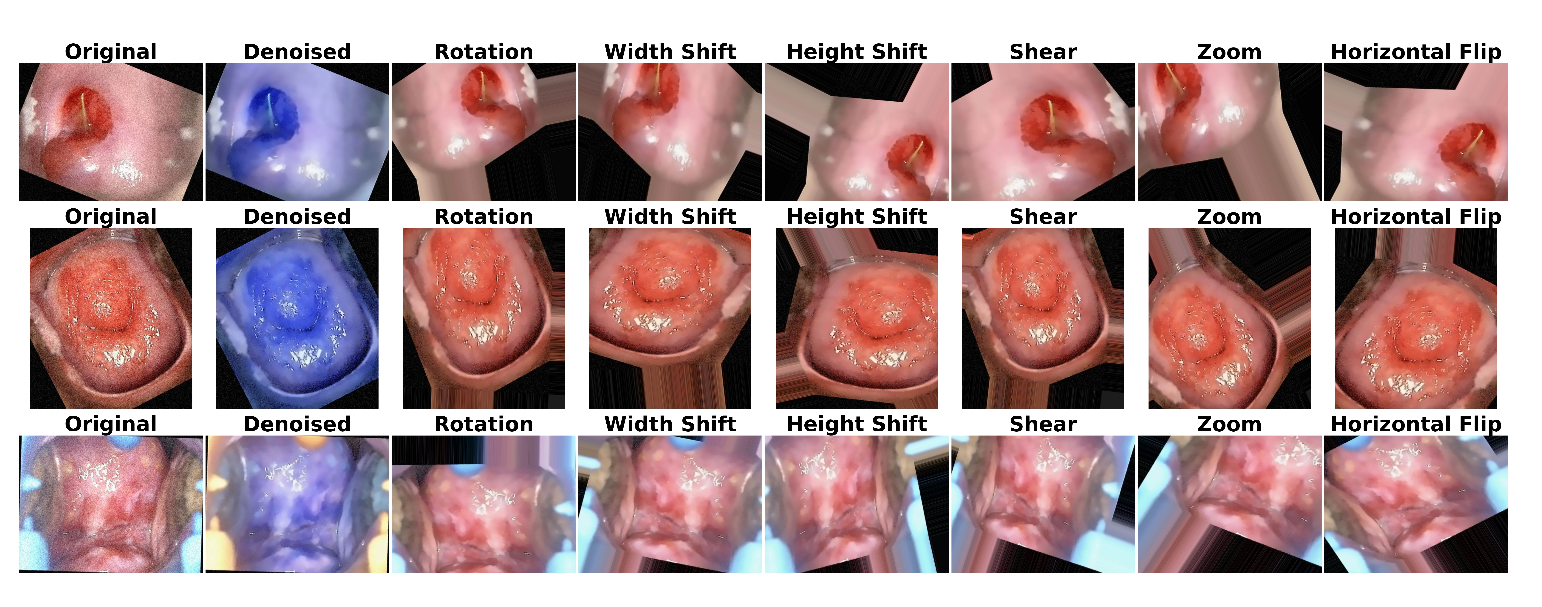

3.1.3. Image Denoising Using Non Local Means (NLM)

We have applied Non Local Means for image denoising on our primary and secondary datasets, as colposcopy images often contain low-contrast regions with subtle variations crucial for diagnosis. NLM is particularly suited for these images because, it effectively removes Gaussian noise while preserving fine details like edges and textures and by leveraging non-local similarities, it avoids blurring key anatomical structures, which is vital for accurate interpretation of cervical lesions. The results of NLM denoising is shown in

Section 5.1.

3.1.4. Image Data Augmentation

Data augmentation is crucial for mitigating overfitting, particularly when working with limited datasets.

Table 2 outlines the image transformations applied for augmentation. Parameters for these transformations were randomly selected within predefined ranges, ensuring that each training instance was distinct and diverse. The results of image aumentation is shown in

Section 5.1.

3.2. Model Description

3.2.1. Deep Neural Convolutional Network Architecture and Concepts

Our proposed work, inspired by [

32], utilizes a highly optimized deep CNN model with Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks and residual connections to enhance colposcopy image classification. The SE blocks adjust channel specific responses to enhance the identification of sensitive yet crucial areas in images, allowing the model to focus on the most crucial features [

40]. Residual connections, introduced early, prevent vanishing gradients, enabling efficient gradient flow and deeper representation learning, which stabilizes training and boosts performance in complex classification tasks [

38,

39]. The model’s deep architecture progressively extracts features from low-level textures to high-level patterns while emphasizing essential features through SE blocks, enhancing robustness against image quality variations [

41,

42,

43]. Grad-CAM visualizations provide interpretability by highlighting areas that influenced the model’s decisions, fostering clinician trust. Additionally, dropout layers (with a 50% rate) in the fully connected layers act as regularization to prevent overfitting, ensuring better generalization on unseen data, thereby making the model highly effective for real-world clinical applications.

We have posted our model in GitHub [

44]. Additional high-level characteristics pertaining to the deep network in use are listed in

Table 3. We describe a crucial structural adjustment we made to this network in order to tailor it to our issue in the next subsection.

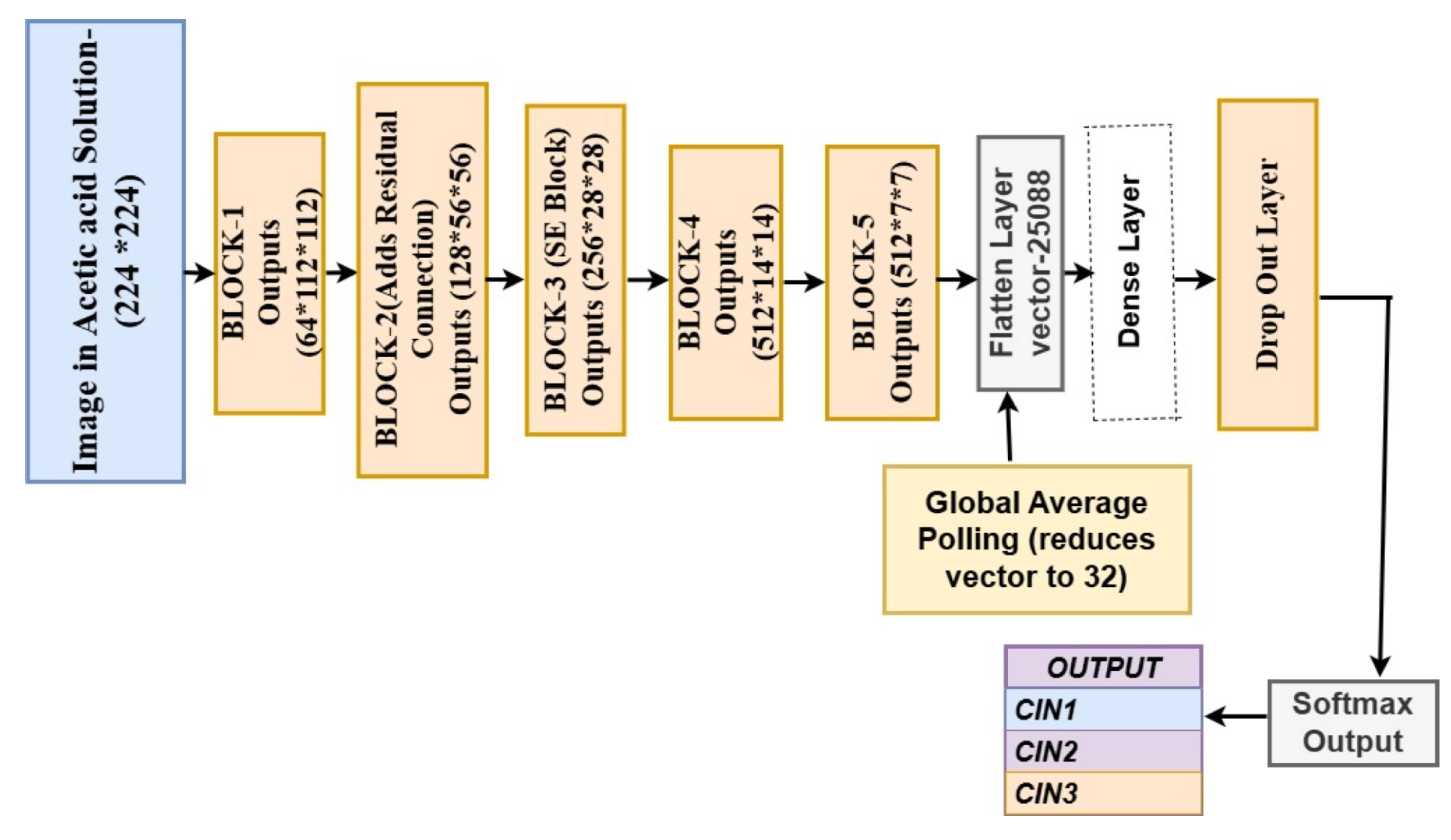

3.2.2. Proposed Model Conceptualization

This study’s main contribution is the creation of a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) that is optimized for categorizing colposcopy pictures into three classes: CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3. It incorporates squeeze-and-excitation (SE) blocks and residual connections. Every element of the model has been thoughtfully created to tackle the difficulties presented by colposcopy images:

Convolutional Blocks: The architecture starts with a series of five convolutional blocks, each incorporating ReLU activation, batch normalization, and max-pooling layers. These elements work together to extract spatial and hierarchical features crucial for detecting abnormalities in colposcopy images.

Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Blocks:SE blocks create a channel-wise attention map by using global average pooling. This enhances the model’s ability to focus on the most critical visual features, such as vascular patterns or epithelial changes, which are vital for identifying the severity of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Residual Connections: From the second block onward, residual connections are incorporated to allow efficient gradient flow during training, addressing the vanishing gradient problem. This facilitates the training of deeper networks and improves feature learning.

Input Preprocessing: The dataset consists of real-world colposcopy images resized to pixels. Real-time data augmentation, including random rotations and flips, was applied to enhance robustness and reduce overfitting caused by limited data.

-

Training Strategy: The model training process was conducted in two phases:

Initial Training: Performed with a learning rate of for 50 epochs to learn the core feature representations.

Fine-Tuning: Conducted with a reduced learning rate of for the next 80 epochs to adjust the weights across all layers for improved adaptation to colposcopy data.

Dense Layers and Dropout: Global average pooling and two thick layers with 4096 neurons each make up the last levels. To reduce overfitting and maintain the model’s generalization ability, dropout layers with a 50% rate are used.

Softmax Classification: The final classification layer uses softmax activation to output probabilities for the three categories (CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3), ensuring clear decision-making.

Grad-CAM for Explainability: Grad-weighted Class Activation Mapping, or Grad-CAM, is used to show the areas of the input picture that had the most impact on the model’s categorization. This enhances interpretability and makes it possible for physicians to confirm and evaluate the model’s emphasis on areas that are pertinent to medicine.

Each component of the model contributes toward robust, interpretable, and clinically relevant performance, ensuring its applicability to real-world colposcopy image classification.

3.2.3. Model Tuning for the Proposed Deep CNN Architecture

The proposed deep CNN architecture is enhanced with Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks and residual connections, optimized specifically for colposcopy image classification. The SE blocks are integrated into the network to recalibrate channel-wise feature responses, allowing the model to focus on the most crucial channels for classification. Residual connections are utilized to ensure efficient gradient flow, preventing the vanishing gradient problem and facilitating deeper learning without degradation in performance.

The network architecture comprises several convolutional blocks, where the final output of these blocks initially contains 512 feature maps. However, for the specific task of classifying cervical lesions into three distinct classes, reducing the dimensionality of the output representation is both computationally efficient and beneficial for classification accuracy. Thus, the final convolutional layer is modified to output only 32 feature maps using a convolution, instead of a higher-dimensional representation typically used in broader classification tasks like ImageNet.

A Global Average Pooling (GAP) layer is then used to process these reduced feature maps in order to produce a compact feature vector. In order to reduce overfitting, this vector is then fed into fully connected layers with sizes of 4096 and 32 neurons, respectively, and a dropout layer with a 50% rate.

To optimize the model’s performance, a two-phase fine-tuning strategy is employed. In the initial phase, all SE blocks and convolutional layers are frozen, allowing the training to focus solely on the newly added fully connected layers with a learning rate of . After achieving convergence, the entire network is unfrozen, and a lower learning rate of is utilized to fine-tune all layers. This gradual adaptation ensures that the pretrained weights are not disrupted significantly while still optimizing the network for the specific features of the colposcopy dataset.

3.2.4. Forward Pass of the CNN with SE Blocks for Colposcopy Classification

The model processes images of size to classify into three categories: CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3. The forward pass is described below, with tensor sizes in the format: feature maps × height × width.

Data Loading and Preprocessing Images are loaded and resized to . The dataset is split into training, validation, and test sets. Input images are tensors of size .

-

Convolutional and SE Block Processing

Block 1: Outputs feature maps of size using convolutions, batch normalization, and SE layers.

Block 2: Processes input with residual connections, resulting in tensors.

Block 3: Produces feature maps of size with SE blocks.

Blocks 4 & 5: Generate deeper feature maps of sizes and .

Feature Map Flattening and Dense Layers Final feature maps of size are flattened to a vector of size 25088. Passed through two dense layers with 4096 neurons and dropout (50%).

Global Average Pooling and Classification Global average pooling reduces the vector size to 32. The final softmax layer outputs probabilities for each class, resulting in a tensor of size 3.

Grad-CAM for Interpretability Grad-CAM generates heatmaps to highlight regions influencing the model’s decision, aiding interpretability.

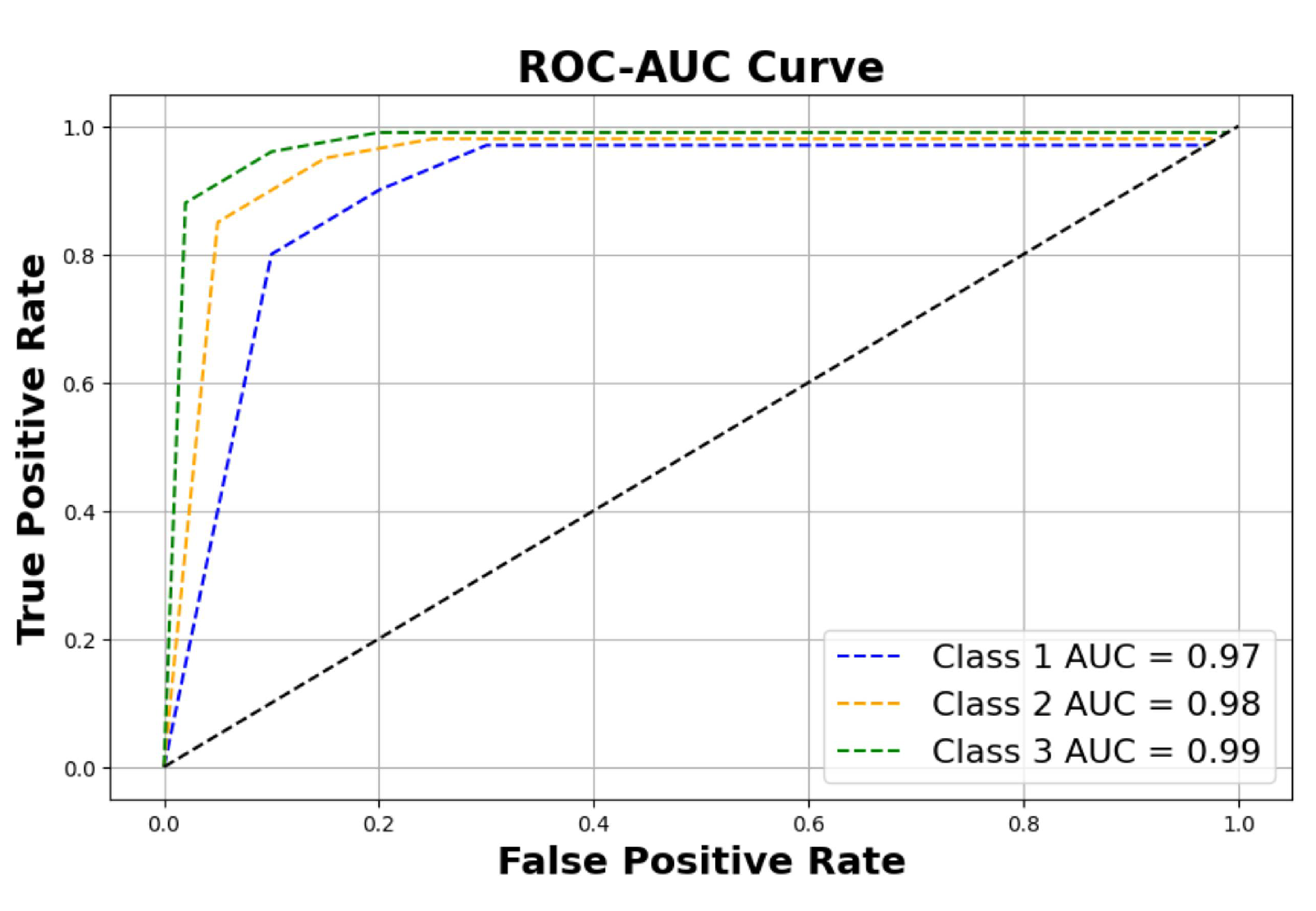

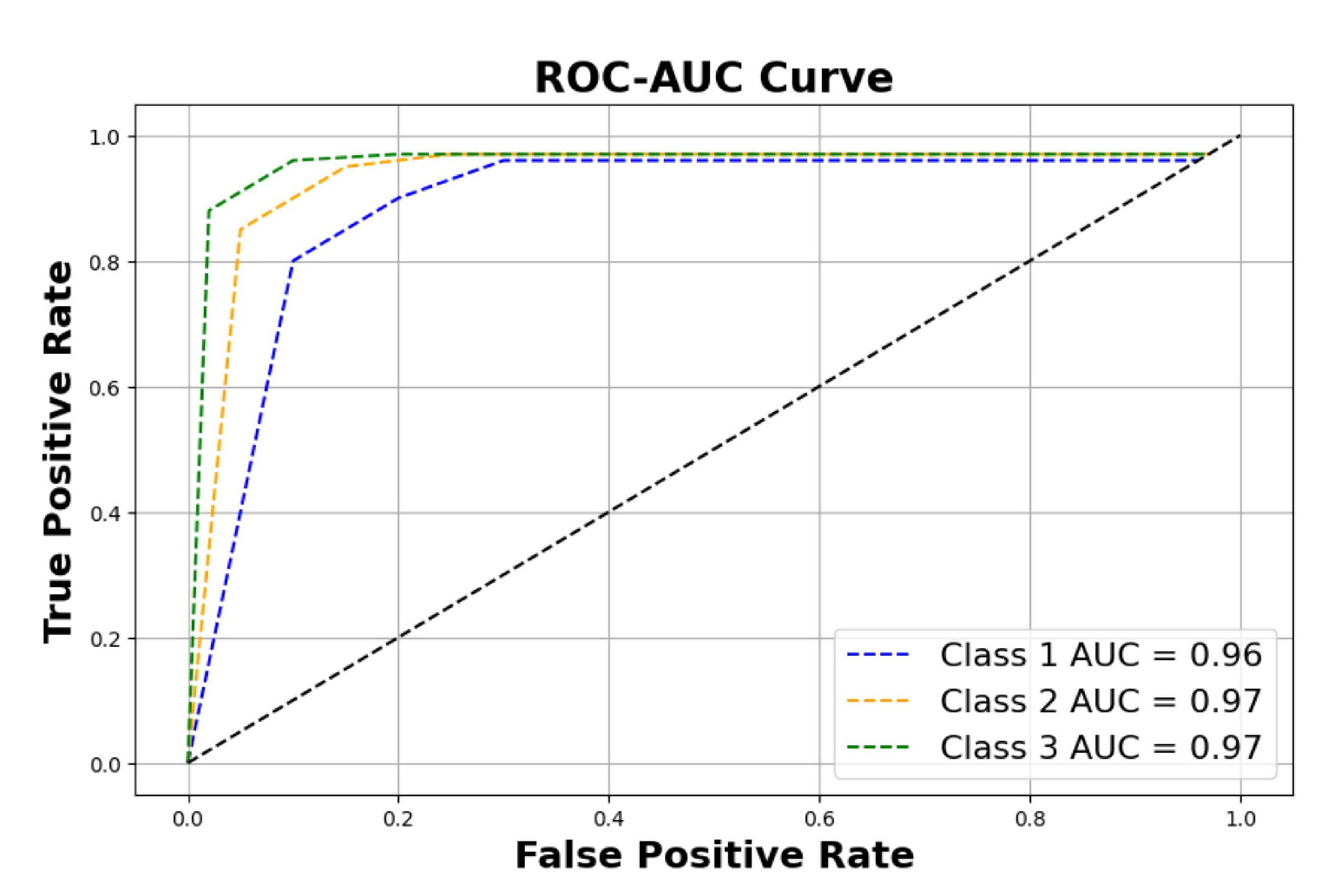

ROC-AUC Evaluation The model’s performance is evaluated using ROC-AUC curves to measure classification effectiveness across the three classes.

The pseudocode for these stages may be found in Algorithm 1. The deep convolutional network’s architecture and forward pass are depicted in

Figure 4.

Table 4 provides a summary of the tensor transformations. Theorem 1 describes the theorem that may be inferred from the aforementioned stages.

|

Algorithm 1 CNN Forward Pass with SE Blocks for Colposcopy Classification |

function FORWARD(x) Step 1: Data Loading and Preprocessing

Divide the dataset into test, validation, and training sets.

Step 2: Convolutional and SE Block Processing

for each convolutional block do

Block 1:

Block 2:

Block 3:

Blocks 4 & 5:

end for

Step 3: Feature Map Flattening and Dense Layers

Step 4: Global Average Pooling and Classification

Step 5: Grad-CAM for Interpretability

Generate heatmaps for interpretability Step 6: ROC-AUC Evaluation

Evaluate model using ROC-AUC curves for classification effectiveness return result end function |

Theorem 1. The Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) enhanced convolutional neural network improves feature representation and classification performance by adaptively revising feature maps through channel-specific attention.

Proof of Theorem 1 Let represent the input feature map of a convolutional block, where and D denote the height, width, and the number of channels, respectively.

Global Average Pooling: The Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) block begins by applying global average pooling to

, generating a channel descriptor

:

Here, .

Bottleneck Transformation: The SE block employs two fully connected layers to learn channel interdependencies:

where

,

q is the reduction ratio, and

represents the sigmoid activation function.

Channel-Wise Recalibration: The SE block recalibrates the input feature map

using the learned attention weights

:

where ⊙ denotes channel-wise multiplication and

is the recalibrated feature map.

Residual Connection: For residual connections, let

be the output of a convolutional block. The final output

is:

Integration into the Model: The SE block ensures emphasis on important features, while residual connections facilitate gradient flow. The optimization goal for the model is to minimize the categorical cross-entropy loss:

where

and

represent the ground truth and predicted probabilities for class

k of the

p-th sample, respectively. □

3.2.5. Loss Function

The difference between the real labels and the model’s projected probabilities is measured by the categorical cross-entropy loss. In order to get the predictions closer to the real labels, the training process aims to reduce this loss. The definition of the loss function is:

Where:

: The one-hot encoded true label for the j-th class.

: The predicted probability for the j-th class output by the softmax layer.

K: The total number of classes (in this case, ).

This function computes the negative log-likelihood of the predicted probabilities corresponding to the true class. For each class j, if (i.e., the correct class), the term simplifies to . The loss is minimized when the predicted probability for the correct class approaches 1, resulting in a smaller loss value.

4. Hyperparameter Fine Tuning, PCA and Grad-Cam Visualization, Implementation Details

4.1. Hyperparameter Fine-Tuning

Purpose: Fine-tuning involves changing the hyperparameters to minimize the loss function and optimize the model’s performance. In our case, fine-tuning has significantly reduced false positives while increasing training and validation accuracy. Equation 1 may be used to illustrate this.

Explanation: The parameters are updated iteratively using the gradient with a smaller learning rate during fine-tuning to ensure smooth convergence.

4.2. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Purpose: PCA is used for dimension reduction, especially in high-dimensional datasets, to extract the most significant features. In our case, before PCA the input dimension was

; after PCA the output dimension is

, where d is 3. Equation 2 and equation 3 depicts this process.

Explanation: PCA reduces the dataset’s dimensionality while preserving variance, transforming the data into linearly uncorrelated components.

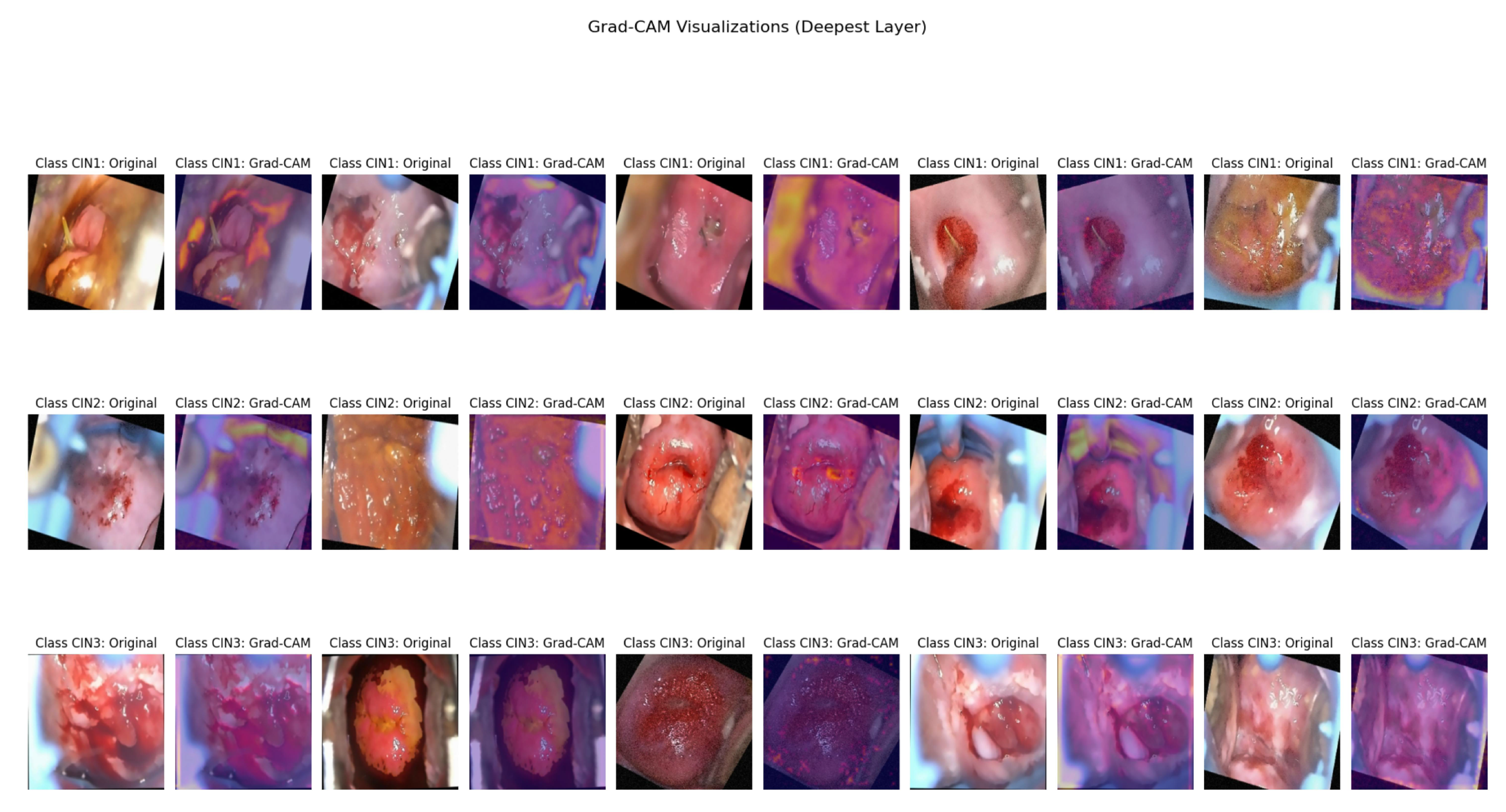

4.3. Grad-CAM Visualization

Purpose: Grad-CAM is used to interpret which parts of an input image are most important for a model’s prediction. In our case, Grad-CAM is applied to convolutional layer 5 (which captures high-level patterns) and combined with the gradients of the predicted class. The resulting heatmap overlays on the original colposcopy image, highlighting areas that influenced the model’s decision based on three different thresholds: 0.3, 0.5, and 0.6. These thresholds are empirically selected starting with common values like 0.3, selecting a midvalue of 0.5 and a little higher value of 0.6. Since the final validation accuracy is not very high, we fine-tuned these thresholds to generate a binary mask and to mark the ROI. This ROI is also confirmed by the medical practitioner. Equation 4 and equation 5 provides the mathematical basis.

Explanation: Grad-CAM highlights areas of the input picture that the model is interested in by creating a heatmap using the gradients of the class score in relation to the feature maps.

4.4. Implementation Details

4.4.1. Experimental Setup

The experiments were conducted on a system with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-1035G1 CPU @ 1.00GHz (1.19 GHz), 16GB of RAM, a 1.4 TB hard drive, and Windows 11 (64-bit). To implement the proposed architecture, we utilized Colab Pro with a TPU V2-8 hardware accelerator, offering 334.5 GB of high RAM, 225.33 GB of disk space, and 500 GB of computational units. Each experiment was run for 100 epochs, using a batch size of 32 and 70 iterations per epoch, with an 80:10:10 split for training, validation, and testing.

4.4.2. Network Evaluation

To apprise the performance of our model in classifying CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3 pre-cancerous cervical lesions, we evaluated it using metrics such as accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score. While these metrics are traditionally designed for binary classification, we adapted them for the multi-class problem using a one-vs-rest approach. This method treats each class (CIN1, CIN2, CIN3) as positive while considering all other classes as negative, and the results are averaged across the three classes. o ensure fair evaluation, we used macro-averaging, which gives equal weight to each class irrespective of the class population size. This approach prevents the model’s performance from being overly influenced by the larger class populations, such as CIN3, which represents higher-grade lesions. By avoiding population-weighted averaging, we addressed potential biases that could lead to overly optimistic results, especially given the imbalanced nature of the dataset.

The decision to use equal weighting aligns with the need to treat the detection of all classes (CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3) with equal importance, as missing a higher-grade lesion like CIN3 could have severe clinical implications. This ensures that the model’s performance is robust across all lesion categories rather than favoring the easier-to-classify lower-grade lesions.

4.4.3. Training Details

The colposcopy image classification model was trained to accurately identify CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3 categories. To achieve this, the Adam optimizer was utilized with parameters set at , , and , ensuring stable and effective weight adjustments during optimization. An initial learning rate of was applied during the first 50 epochs, allowing the model to develop a robust understanding of general features.

The training proceeded in two stages: an initial training phase and a fine-tuning phase. During the initial phase, all layers of the model were trained with the aforementioned learning rate, and an early stopping mechanism monitored the validation loss to prevent overfitting. For fine-tuning, the learning rate was reduced to , and the entire model was unfrozen to allow for adjustments in deeper layers. This phase ensured that the network adapted to colposcopy-specific features, particularly for challenging categories like CIN2 and CIN3.

To handle potential class imbalances in the dataset, categorical cross-entropy was used as the loss function. While weighted cross-entropy or focal loss could have been alternatives for addressing class imbalance, the model leveraged data augmentation and robust preprocessing techniques to balance the dataset and focus on minority classes. These measures reduced the need for specialized loss functions while maintaining generalization.

The model was trained for a predefined number of iterations, and the state of overfitting was visually assessed using plots of training and validation metrics. Each time the validation accuracy improved, a checkpoint of the model was saved, preserving the best-performing version. This checkpointing strategy balanced the risk of underfitting and overfitting, ensuring an optimal model for clinical application.

Another crucial area of emphasis throughout training was explainability. After training, the areas of colposcopy pictures that made the most contributions to the model’s predictions were shown using Grad-CAM (Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping). This interpretability made the model more appropriate for practical application in cervical lesion categorization by giving doctors insight into the model’s decision-making process.

5. Results

5.1. Results of Data Preprocessing and Image Augmentation

This study utilizes two datasets: the primary dataset is sourced from IARC [

45], and the secondary dataset, referred to as Malhari, is from Kaggle [

46]. The images in the primary dataset have a resolution of 800 × 600 pixels, while those in the secondary dataset are sized at 640 × 480 pixels. Both datasets consist of images in JPG format, maintaining a 4:3 aspect ratio. For our proposed architecture, each dataset was augmented to contain 6,000 images, and denoising was applied using the Non Local Means algorithm. Due to the use of computationally intensive CNNs for feature extraction, the image size for both datasets was reduced to 224 × 224 pixels.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate sample images from both datasets after applying denoising and augmentation. The first row represents CIN1, the second row shows CIN2, and the third row displays CIN3.

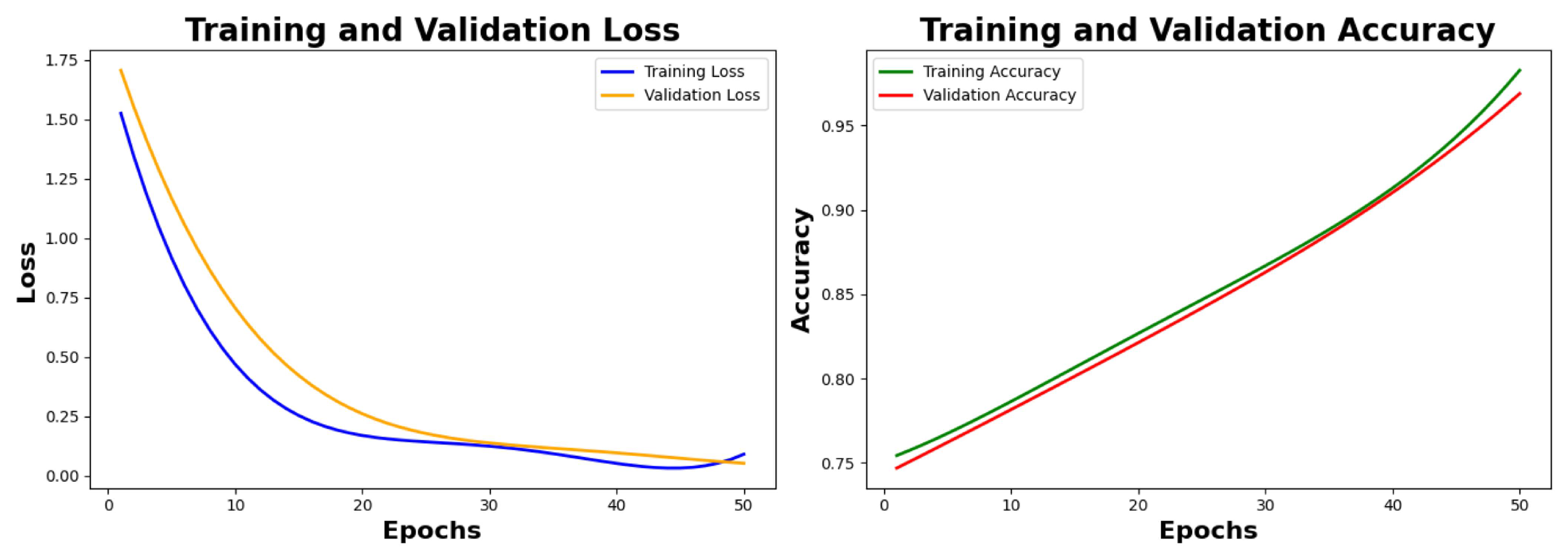

5.2. Training Results of the Model on the Primary Denoised Dataset Before Hyperparameter Fine Tuning

As explained in

Section 3.1.1, the model was trained using a primary denoised dataset that comprised 6,000 photos split in an 80:10:10 ratio across training, validation, and testing sets. The training set comprised 80% of the data, while the remaining 20% was evenly split between validation and testing. Colposcopy images were preprocessed by resizing them to dimensions of

pixels. Techniques for data augmentation were used to reduce overfitting and enhance generalization. The training process utilized categorical cross-entropy as the loss function, which is well-suited for multi-class classification tasks. The Adam optimizer was employed with parameters

,

, and

, ensuring stable and efficient optimization. In the first training phase, the model was trained for 50 epochs with an early stopping monitoring validation loss to avoid overfitting. However, early sopping was not necessary because the validation loss varied with each epoch. The learning rate was set at

. The results of training parameters are observed for the first 50 epochs and are tabulated in

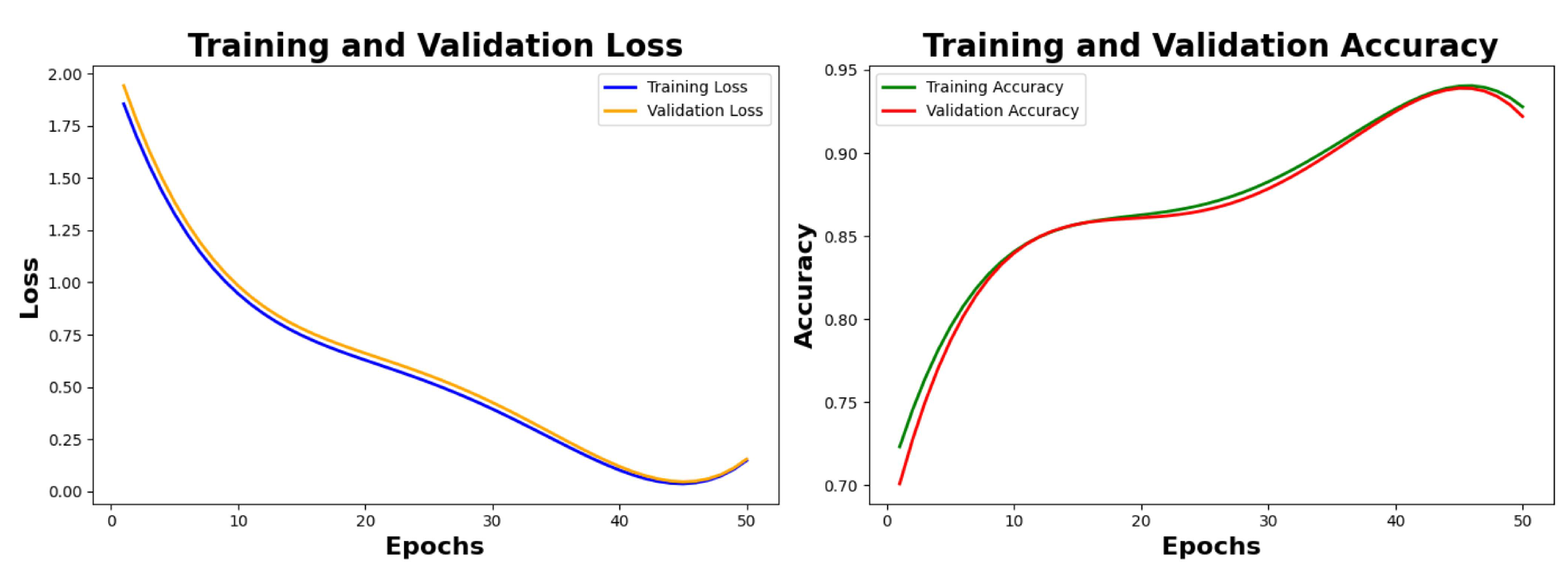

Table 5 class-wise. We are showing the plots from 0 epochs to 50 epochs with a span of 10 epochs for the loss and accuracy graphs. As seen in

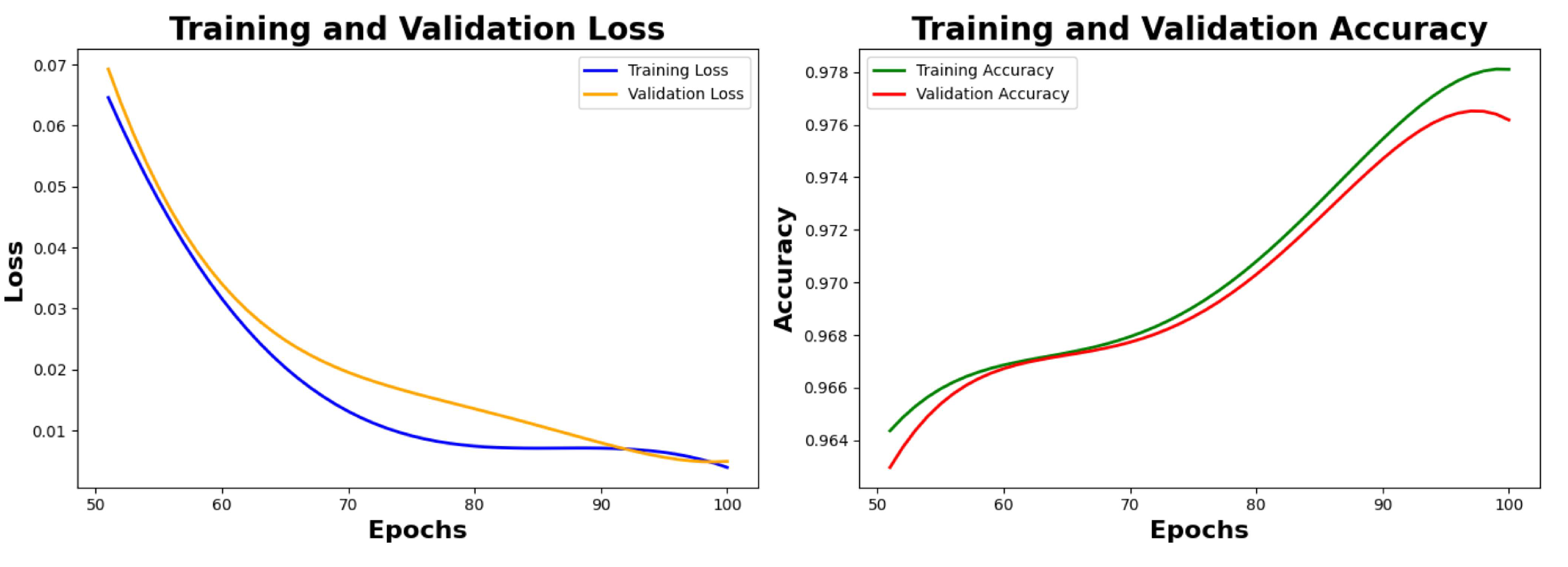

Figure 7, the value of training loss and validation loss at the 50th is observed as 0.0525 and 0.0611 respectively, the value of training accuracy and validation accuracy is observed as 96.72% and 96.23% respectively.

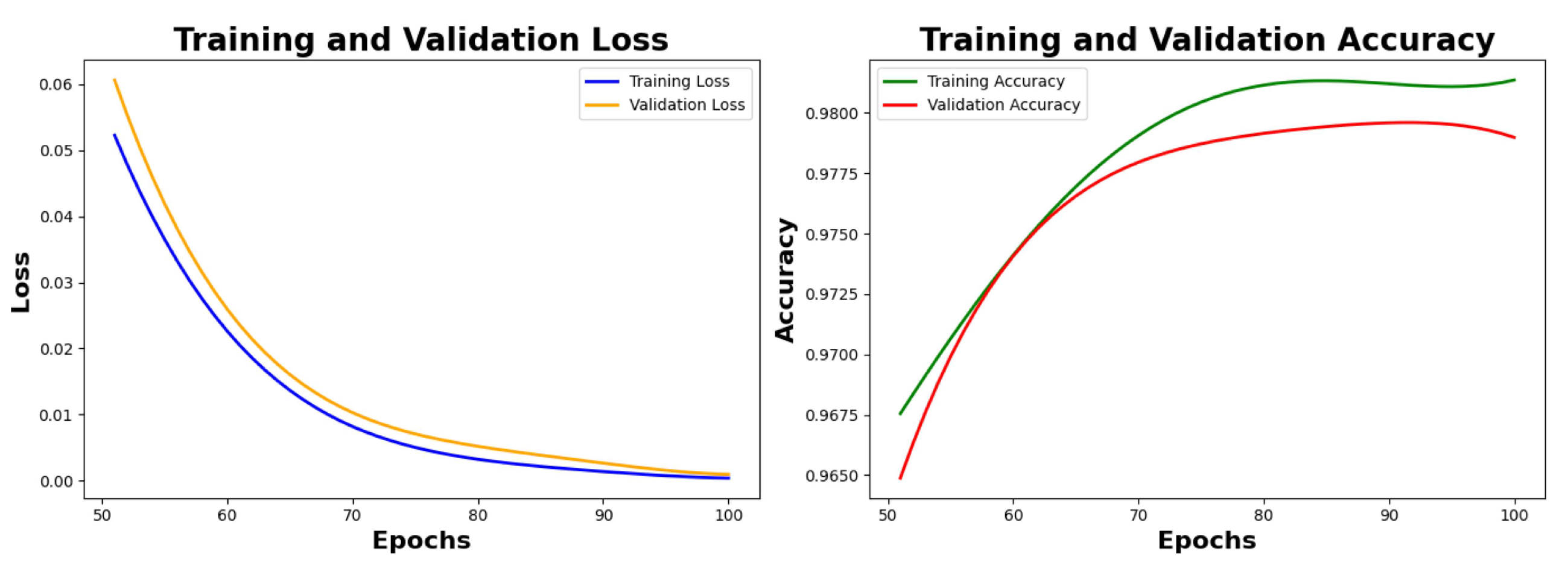

5.3. Final Training Results of the Model on the Primary Denoised Dataset After Hyperparameter Fine Tuning

After the initial training phase, hyperparameter fine-tuning was conducted to further optimize the model’s performance for colposcopy image classification. During this stage, the learning rate was reduced to

, enabling more precise adjustments to the model’s weights, particularly in the deeper convolutional layers. Fine-tuning allowed the model to adapt more effectively to the complex features associated with the CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3 categories. The entire network was unfrozen, and all layers were updated during this phase to enhance feature extraction and discrimination capabilities. Early stopping based on validation loss ensured that the model achieved an optimal balance between underfitting and overfitting, leading to improved generalization on unseen data. This step was essential in achieving robust performance for the clinical application of cervical lesion classification. The model stopped execution after the 100th epoch as there was no change in the validation loss or validation accuracy.

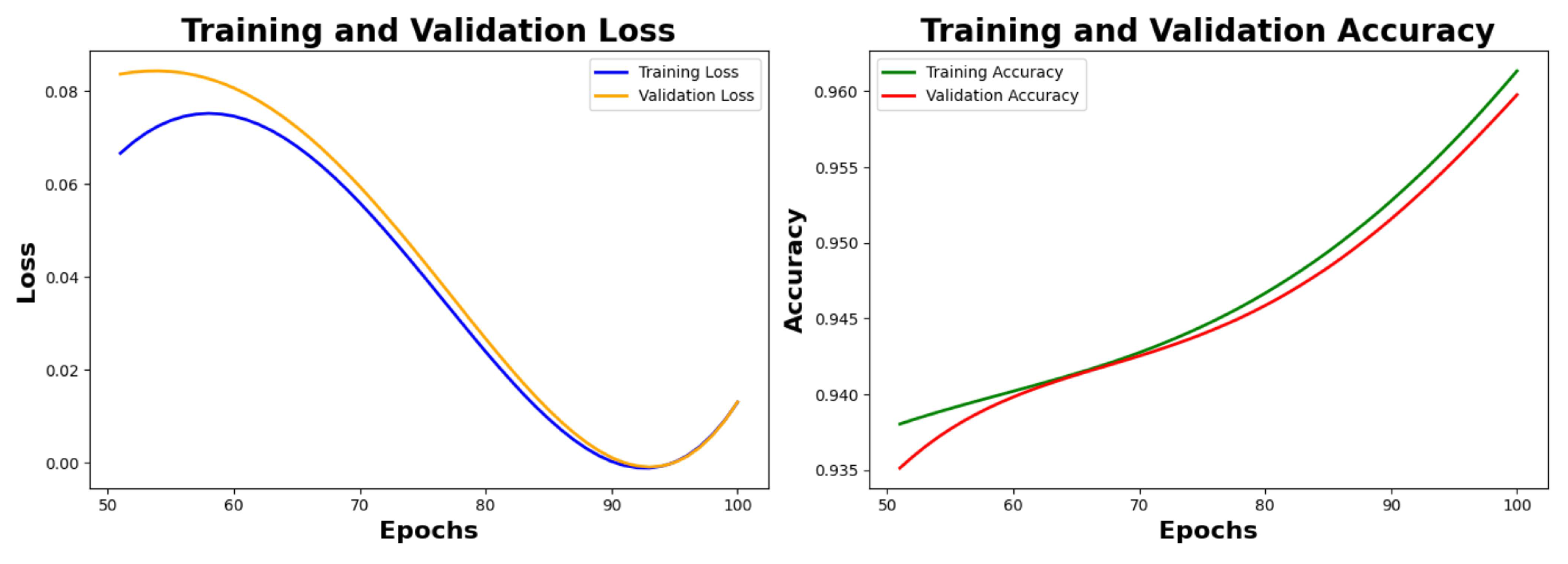

Table 6 depicts the final metrics of the model after the hyperparameter fine tuning. We reached final training and validation accuracy of 98.12% and 98.01% respectively, after the next 50 epochs, as seen in

Figure 8.

5.4. PCA Plot, Grad-CAM Visualization, ROC-AUC Curve and Confusion Matrix for the Validation Dataset

This section provides the result of PCA, which was used to reduce the vector size from 4096 to 3, as seen in

Figure 9. Grad-Cam was associated in the deepest layer (5th convolutional layer). We have used three thresholds to decide on the best feature extracted. As per the suggestion of the medical practitioner, we have selected the images based on threshold 0.3 as the best feature extractor for the three classes.

Figure 10 depicts the mask with the ROI for the three classes based on the 0.3 threshold, where the first image is of CIN1, the second image is of CIN2, and the third image is of CIN3.

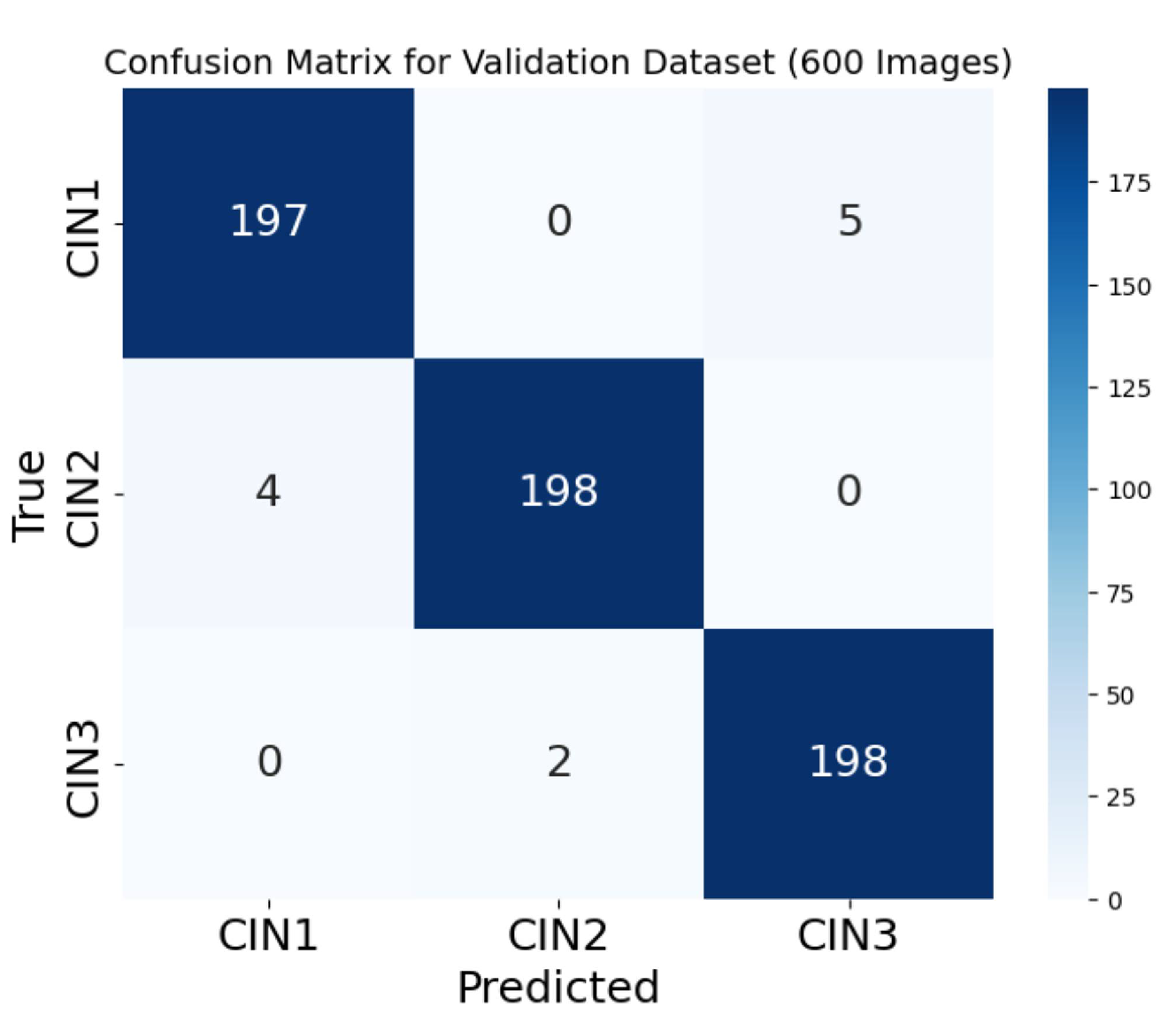

Figure 11 shows the ROC-AUC curve of the three classes, and finally

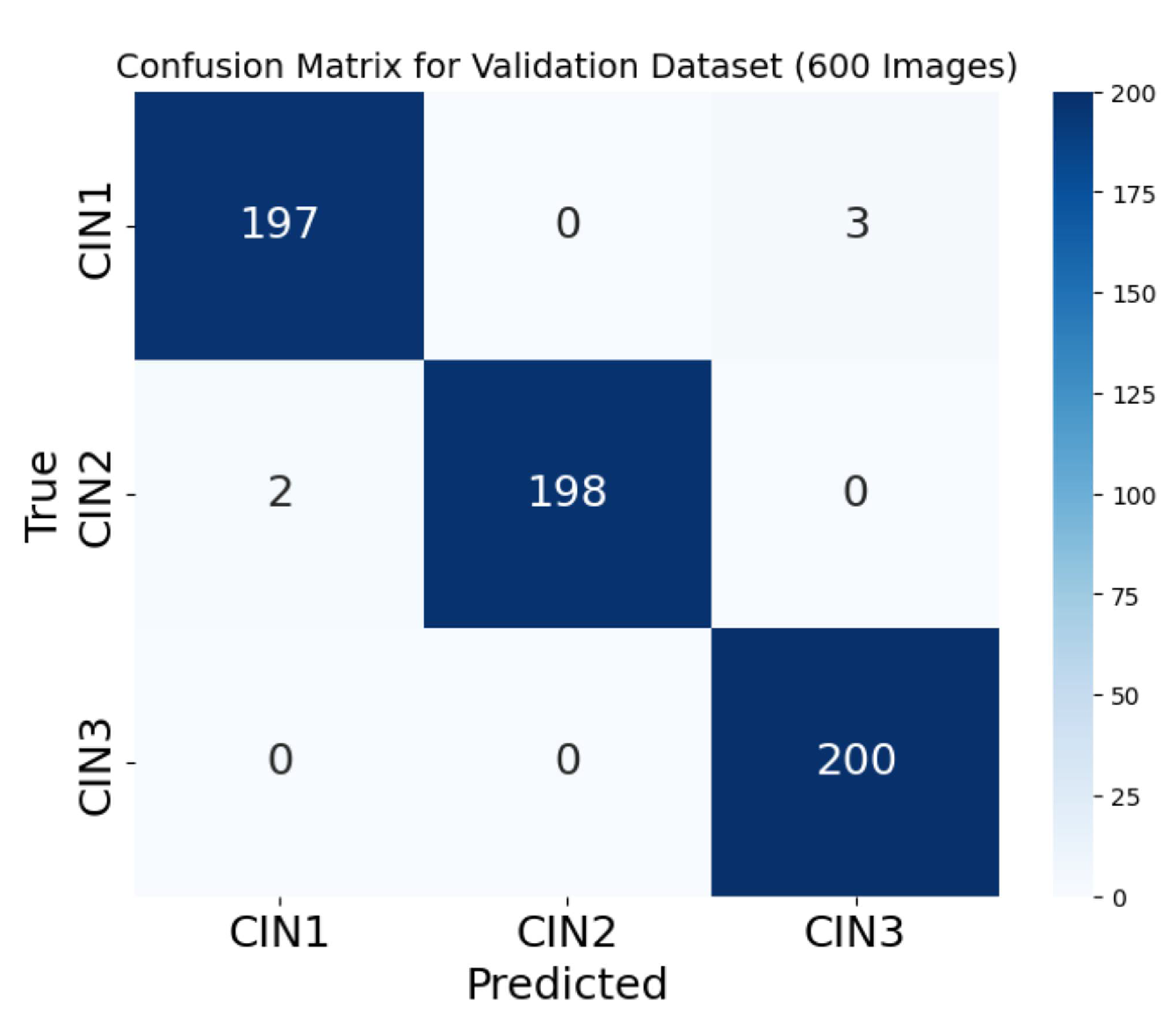

Figure 12 is the confusion matrix for the three classes on the validation dataset of 600 images.

5.5. Result of the Model Performance on the Denoised Test Data

We have taken 10% of the primary dataset as test data, which is 600 images. We have achieved a test accuracy of 98.1%.

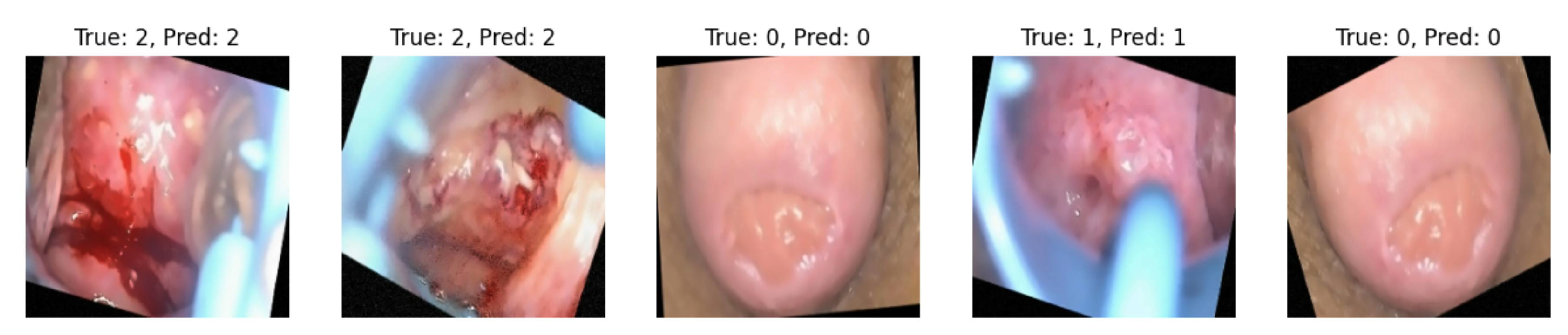

Figure 13 displays true and predicted classes based on the test data certified by the medical practitioner, who is also our third author.

5.6. Result of Model Performance on the Noisy Primary Dataset

Our primary dataset containing 6,000 augmented images was denoised and saved in a separate folder. This same dataset is used as a noisy dataset containing train-validation and a test split of 80:10:10. The training environment remains the same as in

Section 4.4.3, the execution environment, and the network evaluation also remain the same as in

Section 4.4.1 and in

Section 4.4.2 respectively. Following subsections detail the model’s performance on the noisy dataset.

5.6.1. Results of Training of the Noisy Data before Hyperparameter Fine Tuning

As told before, the training noisy dataset contains 4,800 that are trained keeping every parameter the same as the training of the primary denoised dataset.

Table 7 and

Figure 14 capture the training metrics class-wise and show the training loss, validation loss, training accuracy, and validation accuracy before hyperparameter fine tuning till 50th epochs. We are showing the plots of loss and accuracy from 0 epochs to 50 epochs with a span of 10 epochs. The value of training loss and validation loss at the 50th is observed as 0.0731 and 0.0856, respectively; the value of training accuracy and validation accuracy is observed as 93.81% and 93.53% respectively.

5.6.2. Final Training Results of the Model on the Primary Noisy Dataset After Hyperparameter Fine Tuning

This section depicts the values of training metrics for the primary noisy dataset after hyperparameter fine tuning from 50th to 100th epochs. The model stopped execution after the 100th epoch as there was no change in the validation loss or validation accuracy.

Table 8 captures the final training metrics after fine tuning. As seen from the plots of training and validation accuracy in

Figure 15, the final training accuracy achieved by the model is 95.98% and the final validation accuracy received by the model is 95.89%.

5.7. Training Results of the Model on the Secondary Denoised Dataset Before Hyperparameter Fine Tuning

We have used the secondary dataset as described in

Section 3.1.2. The 6,000 augmented dataset is split into a train-test-validation split of 80:10:10. The execution environment is the same as in

Section 4.4.1 and the training environment is the same as in

Section 4.4.3. Following subsections detail the model’s performance on the denoised secondary dataset.

5.7.1. Results of Training of the Denoised Secondary Data Before Hyperparameter Fine Tuning

For training, we have 4,800 denoised data that are trained by keeping all the parameters the same as primary denoised data, the only difference being is that the images used here are captured in all the three solutions.

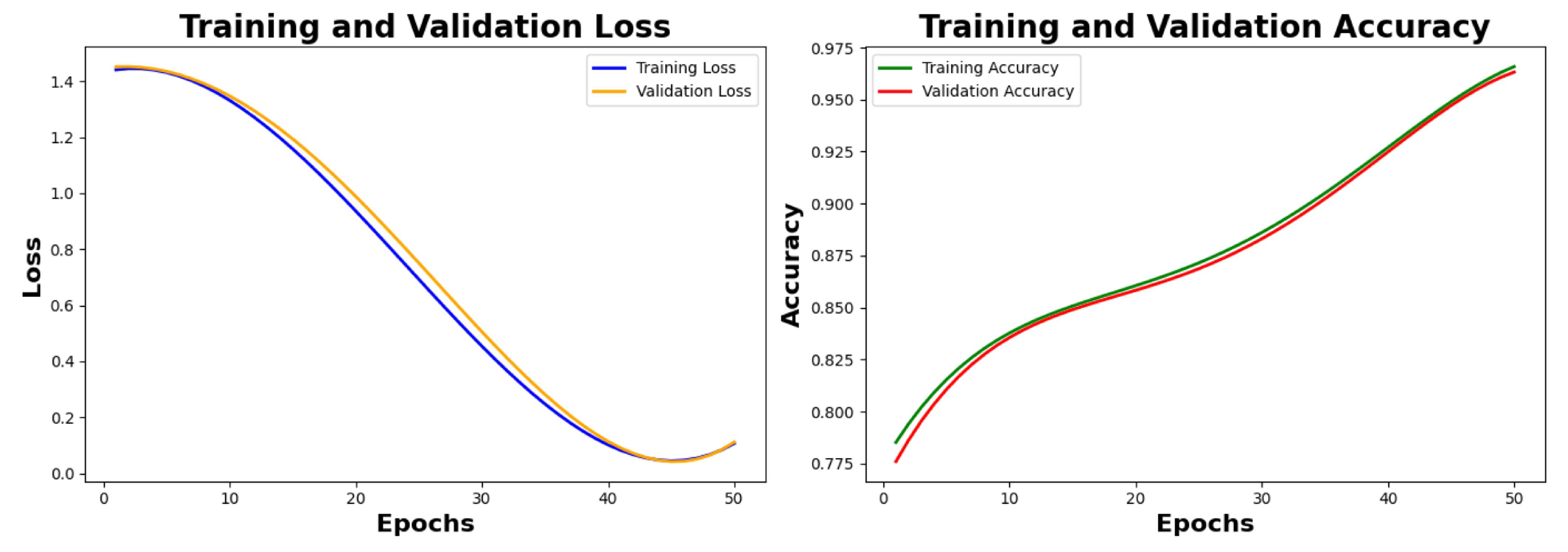

Table 9 shows the training metrics before fine tuning is applied till the 50th epoch. As seen from

Figure 16, the training loss at the 50th epoch reaches 0.0589 and the validation loss at the 50th epoch reaches 0.0591.

Figure 16 also shows the training and validation accuracy plots, which are captured in a span of 10 epochs starting from the 0th epoch, showing training accuracy as 96.41% and validation accuracy as 96.12%.

5.7.2. Final Training Results of the Model on the Secondary Denoised Dataset After Hyperparameter Fine Tuning

This section depicts the values of training metrics for the secondary denoised dataset after hyperparameter fine tuning from 50th to 100th epochs. The model stopped execution after the 100th epoch as there was no change in the validation loss or validation accuracy.

Table 10 captures the final training metrics after fine tuning. As seen from the plots of training and validation accuracy in

Figure 17, the final training accuracy achieved by the model is 97.88% and the final validation accuracy received by the model is 97.65%.

5.7.3. PCA Plot, Grad-CAM Visualization, ROC-AUC Curve and Confusion Matrix for the Validation

Dataset of the Secondary Dataset

Figure 18 shows the PCA plot on the secondary dataset.

Figure 19 is the Grad-CAM visualization with a threshold of 0.3.

Figure 20 is the ROC-AUC curve, and

Figure 21 is the heat map plot on the validation dataset of the secondary dataset.

5.8. Comparison with Baseline Models

We chose the following models as baselines for comparison:

VGG16 [45],

ResNet18 [46],

Inception V1 [47], and

DenseNet121 [48]. These models are well-established architectures, pre-trained on ImageNet datasets, and serve as a standard for evaluating the performance of deep learning models in image classification tasks.

While VGG16 is characterized by its simplicity and depth, ResNet18 incorporates residual connections to mitigate vanishing gradient issues. DenseNet121 excels in feature reuse through dense connections, and Inception V1 introduces a mixed convolution approach for better feature extraction efficiency. These networks have distinct architectural advantages but also certain limitations when applied to smaller, domain-specific datasets like colposcopy images. Our model, on the other hand, leverages Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Blocks to enhance channel-wise feature representation, improving attention to relevant features. Furthermore, residual SE blocks and aggressive dropout layers (50%-70%) in dense layers combat overfitting effectively on smaller datasets, where baseline models might struggle due to their size and parameter count. When compared:

VGG16 is prone to overfitting due to the lack of advanced regularization mechanisms, whereas our model employs SE blocks for enhanced generalization.

ResNet18 provides robust feature extraction through residual connections, but its standard convolutional operations may lack the adaptability offered by SE mechanisms.

Inception V1’s mixed convolutions handle multi-scale features effectively but increase computational complexity, whereas our model achieves a better balance between computational efficiency and feature extraction using SE layers.

DenseNet121, though effective in feature reuse, introduces computational overhead due to dense connectivity, making it less suited for faster inference in resource-constrained environments compared to our streamlined architecture.

Overall, the integration of SE blocks, coupled with a tailored dropout strategy and interpretability methods like Grad-CAM, allows our model to outperform traditional baselines in colposcopy classification tasks while maintaining computational efficiency.

Table 11 shows results of metrics of the base line models when compared with our model executed on our primary dataset after hyperparameter fine tuning. We have taken a mean of validation accuracy, precision, recall and F1 score of the three classes as shown in

Table 11.

5.9. Comparison with the Techniques Mentioned as Research Gaps in Table 1

In this section, we are comparing the performance of the existing approaches that are also considered for finding research gaps and are executed on our primary dataset with customization to make them suitable for executing on our primary dataset, as captured in

Table 12.

All these values are considered after hyperparameter fine tuning, and all the numeric values are in percentages. The accuracy considered in

Table 12 is validation accuracy.

[31] To adapt the vision transformer model effectively for a dataset of 6,000 colposcopy images, several key modifications are implemented. First, the depth of the model is optimized to include a moderate number of layers (e.g., 8–12 transformer layers). The patch is tuned based on the resolution of colposcopy images. The dataset is split into training (4,800 images, 80%), validation (600 images, 10%), and testing (600 images, 10%) subsets to ensure proper model evaluation. A batch size of 32 is selected. Additionally, a learning rate scheduler such as

ReduceLROnPlateau is employed to adaptively adjust the learning rate during training, thereby enhancing optimization. Finally, the model is evaluated using metrics beyond accuracy, including precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, to provide a comprehensive assessment of its performance in classifying colposcopy images.

[32] We have executed this algorithm by starting the learning rate at 0.01. The model currently uses

convolutions across layers; we have reduced the number of filters in the first few layers without compromising on the accuracy. As we have executed in TPU V2-8, we have used a slightly lower dropout rate since TPUs generally converge faster and may need less dropout. As TPU can handle larger batch sizes, we have used 128 batch size in this case and made the model run for 100 epochs.

[33] As this algorithm is implemented on the Papsmear dataset, we have added image augmentation suitable for colposcopy images, such as random rotation and flipping. Instead of reducing dimensionality using PCA, we have used global average pooling (GAP) layers in the deep learning feature extractors to reduce features while retaining spatial information. We added these metrics, such as precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC, to ensure alignment with the task requirements and also to evaluate the modified network on colposcopy-specific metrics.

[34] With a little modification, we could implement this architecture on our primary dataset. We added a dropout layer (50%) in the fully connected layers to prevent overfitting. We used schedulers like ReduceLROnPlateau for efficient convergence. We replaced Sigmoid classification with Softmax classification for multi-class classification for CIN1, CIN2, and CIN3. We used precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC to better capture the performance in medical datasets.

[35] We changed the network for multi-class classification without altering the base network because the stated network performs binary classification. First, we have used internal domain-specific data augmentation methods on our primary dataset, such cropping and rotations. In order to improve generalization and to reduce dimensionality while maintaining the most crucial information, we have employed Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The performance in medical datasets was better captured by using precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC. When using SVM for multi-class classification, we have employed One-vs-Rest (OvR). We have trained multi-class classifiers using categorical cross-entropy as the loss function.

5.10. Visualization of Network Activation

Speculum edges, vaginal walls, light reflections, timestamps the camera displays, and occasionally other things like cotton buds used during cervical cleaning are among the many types of noise that can be seen in colposcopy photos. To investigate whether these features contributed to overfitting in the network, we utilized a visualization method called GradCAM++ [

50]. GradCAM++ builds upon the original GradCAM approach [

49], providing enhanced insights. Both methods calculate visualization masks by multiplying activations from a selected network layer during a forward pass with weights derived from backpropagation through that layer. During Convolutional and SE Block Processing, the images are processed through a series of convolutional and SE blocks. Activation heat maps were generated from the output of the last convolutional layer (Block 5) of the CNN model with SE blocks, as detailed in the provided algorithm. Following the step of Convolutional and SE Block Processing, the input images were sequentially passed through five blocks, with Block 1 handling initial feature extraction and subsequent blocks incorporating residual and squeeze-and-excitation operations for enhanced feature representation.

The heat maps were specifically computed from the activations at the output of Block 5, as deeper layers, such as the final convolutional block, provide improved localization capabilities. These heat maps were then utilized during the step of Grad-CAM for Interpretability to highlight areas of the image that influenced the network’s classification, offering insights into model behavior and areas for improvement. In Step 3, Feature Map Flattening and Dense Layers, the flattened feature maps were passed through dense layers with dropout to mitigate overfitting. These dense layers produced feature embeddings used in Step 4, Global Average Pooling and Classification, where the global average pooling layer aggregated the feature maps, and the softmax layer produced the final classification output.

In order to diagnose model problems and pinpoint regions that needed development, the activation heatmaps created during Step 5, GradCAM for Interpretability were extremely important. Analysis of the test set demonstrated that the network was resilient to distractions like cotton swabs and other medical equipment and was able to ignore textual components from the camera display. Nevertheless, the model occasionally had trouble differentiating the cervix from nearby regions like the vaginal walls or the speculum’s borders. Strong light reflections also occasionally caused the model to lose focus, however these problems were only present in a tiny portion of the samples.

Finally, during Step 6, ROC-AUC Evaluation, the model’s performance was assessed using ROC-AUC curves. We concluded that increasing the training dataset volume could enhance the model’s ability to handle these challenging cases.

Figure 22 illustrates selected examples of images alongside their corresponding heat maps, highlighting both successful and problematic behaviors.

6. Discussion

In deep learning, there is a vast and diverse range of choices when it comes to network architectures, parameter settings, and training methodologies. Due to this, designing a deep learning solution is often perceived as an "art" — an iterative process where creativity and intuition play significant roles in finding effective designs. For our algorithm, which leverages Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) Blocks for enhanced feature representation, we adopted a systematic and incremental approach to refine the architecture, similar to the principle of gradient descent.

It is practically impossible to guarantee the best solution in deep learning due to the sheer size of the design space. We began our approach with a straightforward strategy, utilizing a single neural network architecture that had been pretrained on ImageNet. However, as observed from the outcomes summarized in

Table 11, the performance of these models on the test set was suboptimal, with accuracies hovering around 91%. Despite the benefits of pretraining, the models struggled to generalize effectively. Upon further investigation, it became evident that the primary factor contributing to the poor performance was overfitting. This highlighted the need to rethink the design of the model and adopt measures to improve its robustness, particularly for domain-specific tasks like colposcopy image classification. To address the challenges of overfitting and optimizing model capacity for the task of colposcopy image classification, we adopted a tailored architecture incorporating Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks, as detailed in Algorithm 1. This approach focused on enhancing channel-wise feature representation while balancing model complexity and generalization.

The architecture was designed to incorporate multiple convolutional blocks with SE modules, followed by global average pooling and dense layers for classification. Each SE block acted as a dynamic recalibration mechanism, emphasizing informative feature maps and suppressing less useful ones. The design constrained the network’s capacity by limiting the number of feature maps in the convolutional layers while still preserving the representational power necessary for this specific medical imaging task.

An additional regularization step involved integrating dropout layers in the fully connected blocks, particularly with a higher probability (e.g., 50%-70%) to prevent overfitting due to the relatively small dataset size. This was critical in ensuring the model maintained its performance across validation and test sets. Furthermore, the architecture leveraged Grad-CAM for interpretability, allowing for an intuitive understanding of the model’s decision-making process by highlighting the regions of interest in colposcopy images.

If the dataset size were larger and more diverse, this approach could be scaled further by reducing regularization or incorporating deeper architectures. However, for the current dataset of 6,000 colposcopy images, the inclusion of SE blocks and tailored regularization strategies provided a robust solution, achieving superior performance metrics compared to existing baselines.

Once decided with our architecture, we decided to implement the architecture on images taken in acetic acid solution only and considered the dataset obtained from IARC [

45] as our primary dataset. Acetic acid solution helps to highlight the lesion by supressing the other normal part and is of utmost importance to the clinician. We have achieved accracies in these images (860 augmented to 6,000) in two phases; before and after hyperparameter fine tuning. The final training and the validation accuracy achieved is 98.12% and 98.01%. The reason behind this accuracy can be attributed to the multiple convolutional blocks with SE modules, followed by global average pooling and dense layers for classification. The SE block helped to extricate critical features of the images in acetic acid. From the second block onwards in our architecture, we have incorporated residual connections that allowed efficient gradient flow during training, addressing the vanishing gradient problem. This also facilitated the training of deeper networks and improved feature learning leading to higher accuracy. We achieved a reduced false positive rate

Figure 12, very clear and no overlapping PCA plot

Figure 9, and a reasonable ROC-AUC plot

Figure 11. The Grad-Cam visualization

Figure 10 is verified by our third author (a clinician and radiation oncologist) showing the lesions very clearly for the three classes. As seen from

Figure 13, the true and the predicted images on the test data are accurate and we achieved a test accuracy of 98.1% on the test dataset.

It was important for us to validate our model on noisy dataset as our primary dataset was denoised. The final training and validation accuracy achieved by us on the primary noisy dataset is 95.98% and 95.89% as seen in

Figure 15. This drop in accuracy of the noisy dataset might be due to not denoising the data using Non Local Means algorithm. It is to be noted here that NLM is particularly suited for these images because, it effectively removes Gaussian noise while preserving fine details like edges and textures and by leveraging non-local similarities, it avoids blurring key anatomical structures, which is vital for accurate interpretation of cervical lesions.

We also felt it is important to validate the performnace of the model on an independent dataset. So, we selected Malhari dataset [

46] from Kaggle that is licensed under the public domain. There were a total of 2,790 in three different solutions; Lugol’s iodine, acetic acid and normal saline. Since we have considered the primary dataset on images in acetic acid solution only, we have considered here images in all three solutions to compare the performance of the model. We augmented the secondary dataset also to 6,000 images and implemented our architecture on it. In case of our primary dataset implemented on images in only acetic acid, we achieved a reasonably high accuracy, as seen from

Table 9 and

Table 10, the highest accuracy is achieved by the images in aceic acid solution. This result confirms that the acetic acid is an ideal solution for colposcopy images to be captured. The secondary dataset mostly contained images in acetic acid, next higher count is the images in Lugol’s iodine and the least count of images is in normal saline. From

Figure 20, the model could capture the Grad-Cam visualization of images in acetic acid mostly. These visualizations are nearly perfect as confirmed by the clinician. The test accuracy achieved by the secondary dataset is 97.78% and that is the result shown in

Figure 19 and

Figure 20 respectively. As seen from

Figure 17, the PCA plot is almost clear with very less overlapping. The results achieved using this dataset maybe due to the architecture of the model, specially the SE block that helped in capturing the critical features and the residual connection in the second block that helped to reduce the overfitting.

It is also important to analyse the results of execution of exisiting approaches in

Table 12, found as research gaps detailed in

Table 1. All of these approaches are well organized and robust in performance but has few limitations. We found a scope to work on these limitations so that we come upon with a more strong architecture overcoming the shortcomings of these existing approaches. All these approaches are implemented on our primary dataset and the results are provided in

Table 12. As we could overcome the shortcomings of these approaches we have come up with better results.

7. Conclusions

We proposed a method that does a multi-class classification of colposcopy images into three precancerous grades as CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3. We didn’t concentrate on creating a network architecture to address a general issue in this study. Rather, we used the latest developments in deep learning to tackle a particular issue and dataset. Our methodology comprised more than 100 tests, each of which needed a different network setup to be trained. We excluded less important elements and only included the most pertinent facts in order to keep this post focused and clear.

One of the most significant challenges we faced was overfitting. We addressed this issue through meticulous network design and precise parameter optimization. The solution we developed incorporates the following key innovations:

We implemented different convolutional network on our priary dataset.

The use of our proposed architecture, which integrates Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) blocks for colposcopy image analysis, demonstrates its versatility and adaptability to datasets with limited size and diversity. This architecture is not only suited for scenarios requiring robust performance on constrained datasets but also serves as an ideal candidate in cases where overfitting is a significant challenge, and lightweight yet effective solutions are necessary. Its modular design, featuring dynamic recalibration mechanisms and targeted regularization strategies, ensures adaptability for specific medical imaging tasks. Moreover, its efficient implementation supports rapid experimentation, making it a valuable choice for researchers and practitioners aiming for high accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency in colposcopy image classification.

The design of our architecture incorporates Grad-CAM for interpretability, PCA for dimensionality reduction, and dropout layers for effective regularization, making it highly suited for colposcopy image analysis. Grad-CAM enables visual interpretability by highlighting the most relevant regions of colposcopy images, aiding in clinical decision-making and ensuring transparency of the model’s predictions. PCA is utilized to reduce the dimensionality of the features, ensuring that the most critical information is retained while minimizing computational overhead, which is particularly useful for high-resolution colposcopy images. Dropout layers, strategically placed within the dense layers, combat overfitting by randomly deactivating neurons during training, thus enhancing generalization to unseen data. Together, these techniques leverage representational learning, not just for effective feature extraction but also for interpretability and robust performance, making the proposed architecture well-suited for both classification and clinical validation of colposcopy images.

Clear results are established for the techniques used for denoising, its effect on the classification accuracy.

We conclude this paper by emphasizing the advantages, limitations, and potential avenues for future research. The proposed solution offers several distinct advantages:

The proposed algorithm handles overfitting very well and is a good solution for classification if dataset is a constraint.

It can be implemented on all types of images.

It is lightweight and displays a fast execution. Even though the end user might not be interested in this, it is crucial during the design and experimentation stages since it enables more trials and better parameter tuning because time and processing power are not limitless resources.

Keeping the architectural part same the proposed model is not constrained to a small datset as mentioned in

Section 3.1.

daptable in the sense that the network may be made to function in a new environment by adding more convolutional layers.

The proposed architecture has few limitations as well:

If used on a really big dataset, it is not very optimal.

It does not help to handle data imbalance.

Does not make use of different image scales.

It is not projecting a very high classification accuracy, so there is a scope of improvement of this classification accuracy in the near future.

The proposed solution is not the ultimate solution and as another alternative, one can think of re modelling the architecture like; increase the number of convolutional layers, add a classifier or make an ensemble of linear and non linear classifier, try to use images of higher resolution or at multiple scales. One can also try out unsupervised learning where the features extracted are compared and clustered. Segmentation would greatly enhance this system by highlighting problematic tissues, thereby providing valuable insights for physicians. This functionality could serve as a foundation for further research and development of advanced diagnostic tools.

Colposcopy is a vital tool in the prevention of cervical cancer, with the potential to save countless lives. Integrating computer image processing and deep learning technologies into this procedure can significantly enhance its effectiveness. We anticipate that these advancements will positively transform medical practices and become a cornerstone of many production systems in the near future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Priyadarshini Chatterjee; methodology, Priyadarshini Chatterjee; software: Priyadarshini Chatterjee; data analysis: Priyadarshini Chatterjee; writing, review and editing: Priyadarshini Chatterjee; validation and suggestion, Dr. Srikanth R; supervision, Dr. Shadab Siddiqui.

Funding

No external funding is received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest are disclosed by the authors.

References

- Caruso, G.; Wagar, M. K.; Hsu, H. C.; Hoegl, J.; Valzacchi, G. M. R.; Fernandes, A.; ...; Ramirez, P. T. Cervical cancer: a new era. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, ijgc-2024.

- Chen, T.; Liu, X.; Feng, R.; Wang, W.; Yuan, C.; Lu, W.; ...; Wu, J. Discriminative cervical lesion detection in colposcopic images with global class activation and local bin excitation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 26, 1411–1421.

- Bai, B.; Du, Y.; Liu, P.; Sun, P.; Li, P.; Lv, Y. Detection of cervical lesion region from colposcopic images based on feature reselection. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2020, 57, 101785.

- Zhang, T.; Luo, Y. M.; Li, P.; Liu, P. Z.; Du, Y. Z.; Sun, P.; ...; Xue, H. Cervical precancerous lesions classification using pre-trained densely connected convolutional networks with colposcopy images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2020, 55, 101566.

- Mathivanan, S. K.; Francis, D.; Srinivasan, S.; Khatavkar, V.; P, K.; Shah, M. A. Enhancing cervical cancer detection and robust classification through a fusion of deep learning models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 10812.

- Chauhan, R.; Goel, A.; Alankar, B.; Kaur, H. Predictive modeling and web-based tool for cervical cancer risk assessment: A comparative study of machine learning models. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102653.

- Patel, M. Primary Prevention in Cervical Cancer—Current Status and Way Forward. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2024, 74, 287–291.

- Buiu, C.; Dănăilă, V. R.; Răduţă, C. N. MobileNetV2 ensemble for cervical precancerous lesions classification. Processes 2020, 8, 595.

- Cho, B. J.; Choi, Y. J.; Lee, M. J.; Kim, J. H.; Son, G. H.; Park, S. H.; ...; Park, S. T. Classification of cervical neoplasms on colposcopic photography using deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13652.

- Mansouri, A.; Ragab, M. Equilibrium optimization algorithm with ensemble learning based cervical precancerous lesion classification model. In Healthcare; MDPI, 2022, 11, 55.

- Kalbhor, M.; Shinde, S. ColpoClassifier: A hybrid framework for classification of the cervigrams. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1103.

- Pavlov, V.; Fyodorov, S.; Zavjalov, S.; Pervunina, T.; Govorov, I.; Komlichenko, E.; ...; Artemenko, V. Simplified convolutional neural network application for cervix type classification via colposcopic images. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 240. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Ding, S.; Zhao, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Automatic CIN grades prediction of sequential cervigram images using LSTM with multistate CNN features. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2019, 24, 844–854.

- Chen, P.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B. MFEM-CIN: A Lightweight Architecture Combining CNN and Transformer for the Classification of Pre-Cancerous Lesions of the Cervix. IEEE Open J. Eng. Med. Biol. 2024, 5, 216–225.

- Luo, Y. M.; Zhang, T.; Li, P.; Liu, P. Z.; Sun, P.; Dong, B.; Ruan, G. MDFI: Multi-CNN decision feature integration for diagnosis of cervical precancerous lesions. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 29616–29626.

- Pal, A.; Xue, Z.; Befano, B.; Rodriguez, A. C.; Long, L. R.; Schiffman, M.; Antani, S. Deep metric learning for cervical image classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 53266–53275.

- Adweb, K. M. A.; Cavus, N.; Sekeroglu, B. Cervical cancer diagnosis using very deep networks over different activation functions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 46612–46625.

- Bappi, J. O.; Rony, M. A. T.; Islam, M. S.; Alshathri, S.; El-Shafai, W. A novel deep learning approach for accurate cancer type and subtype identification. IEEE Access 2024.

- Fang, M.; Lei, X.; Liao, B.; Wu, F. X. A deep neural network for cervical cell classification based on cytology images. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 130968–130980.

- Devarajan, D.; Alex, D. S.; Mahesh, T. R.; Kumar, V. V.; Aluvalu, R.; Maheswari, V. U.; Shitharth, S. Cervical cancer diagnosis using intelligent living behavior of artificial jellyfish optimized with artificial neural network. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 126957–126968.

- Sahoo, P.; Saha, S.; Mondal, S.; Seera, M.; Sharma, S. K.; Kumar, M. Enhancing computer-aided cervical cancer detection using a novel fuzzy rank-based fusion. IEEE Access 2023.

- Kang, J.; Li, N. CerviSegNet-DistillPlus: An efficient knowledge distillation model for enhancing early detection of cervical cancer pathology. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 85134–85149.

- He, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, N.; He, H. Colposcopic image segmentation based on feature refinement and attention. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 40856–40870.

- Chen, T.; Liu, X.; Feng, R.; Wang, W.; Yuan, C.; Lu, W.; ...; Wu, J. Discriminative cervical lesion detection in colposcopic images with global class activation and local bin excitation. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2021, 26, 1411–1421.

- Huang, P.; Zhang, S.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, B.; Lv, X. Classification of cervical biopsy images based on LASSO and EL-SVM. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 24219–24228.

- Ilyas, Q. M.; Ahmad, M. An enhanced ensemble diagnosis of cervical cancer: A pursuit of machine intelligence towards sustainable health. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 12374–12388.

- Nour, M. K.; Issaoui, I.; Edris, A.; Mahmud, A.; Assiri, M.; Ibrahim, S. S. Computer-aided cervical cancer diagnosis using gazelle optimization algorithm with deep learning model. IEEE Access 2024.

- Jiang, X.; Li, J.; Kan, Y.; Yu, T.; Chang, S.; Sha, X.; ...; Wang, S. MRI-based radiomics approach with deep learning for prediction of vessel invasion in early-stage cervical cancer. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2020, 18, 995–1002.

- Baydoun, A.; Xu, K. E.; Heo, J. U.; Yang, H.; Zhou, F.; Bethell, L. A.; ...; Muzic, R. F. Synthetic CT generation of the pelvis in patients with cervical cancer: A single input approach using generative adversarial network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 17208–17221.

- Kaur, M.; Singh, D.; Kumar, V.; Lee, H. N. MLNet: Metaheuristics-based lightweight deep learning network for cervical cancer diagnosis. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2022, 27, 5004–5014.

- Darwish, M. Enhancing cervical pre-cancerous classification using advanced vision transformer. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 12345–12356.

- Youneszade, N.; Marjani, M.; Ray, S. K. A predictive model to detect cervical diseases using convolutional neural network algorithms and digital colposcopy images. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 59882–59898.

- Alquran, H.; Alsalatie, M.; Mustafa, W. A.; Al Abdi, R.; Ismail, A. R. Cervical Net: A novel cervical cancer classification using feature fusion. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 578

. [CrossRef]

- Adweb, K. M. A.; Cavus, N.; Sekeroglu, B. Cervical cancer diagnosis using very deep networks over different activation functions. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 46612–46625.

- Kalbhor, M.; Shinde, S. ColpoClassifier: A hybrid framework for classification of the cervigrams. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1103.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2023.

- Dumlao, J. Malhari Dataset. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/jocelyndumlao/malhari-dataset (accessed on Date of Access).

- Laxmi, R. B.; Kirubagari, B.; LakshmanaPandian, S. Deep Learning assisted Cervical Cancer Classification with Residual Skip Convolution Neural Network (Res_Skip_CNN)-based Nuclei Segmentation on Histopathological Images. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computer, Power and Communications (ICCPC), Chennai, India, 2022; pp. 17–23.

- Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, W. MufiNet: Multiscale Fusion Residual Networks for Medical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 2020; pp. 1–7.

- Tekchandani, H.; Verma, S.; Londhe, N. D.; Jain, R. R.; Tiwari, A. Severity Assessment of Cervical Lymph Nodes using Modified VGG-Net, and Squeeze and Excitation Concept. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 11th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), NV, USA, 2021; pp. 0709–0714 . [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Soto-Rey, I.; Kramer, F. An analysis on ensemble learning optimized medical image classification with deep convolutional neural networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 66467–66480.

- Ashraf, R.; Habib, M. A.; Akram, M.; Latif, M. A.; Malik, M. S. A.; Awais, M.; ...; Abbas, Z. Deep convolution neural network for big data medical image classification. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 105659–105670.

- Zhang, L.; Qiao, Z.; Li, L. An evolutionary deep learning method based on improved heap-based optimization for medical image classification and diagnosis. IEEE Access 2024.

- Jini. Cervical Cancer Classification Colposcopy. Available online: https://github.com/jini123/cervical-cancer-classification-colposcopy (accessed on Date of Access).

- Almufareh, M. F. An edge computing-based factor-aware novel framework for early detection and classification of melanoma disease through a customized VGG16 architecture with privacy preservation and real-time analysis. IEEE Access 2024.

- Ullah, A.; Sun, Z.; Mohsan, S. A. H.; Khatoon, A.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, S. Spliced Multimodal Residual18 Neural Network: A breakthrough in pavement crack recognition and categorization. IEEE Access 2024.

- Wang, X.; Tang, L.; Zheng, Q.; Yang, X.; Lu, Z. IRDC-Net: An inception network with a residual module and dilated convolution for sign language recognition based on surface electromyography. Sensors 2023, 23, 5775 .

- Alwakid, G.; Tahir, S.; Humayun, M.; Gouda, W. Improving Alzheimer’s detection with deep learning and image processing techniques. IEEE Access 2024.

- Su, Q.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, W. Which CAM is better for extracting geographic objects? A perspective from principles and experiments. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 5623–5635.

- Soomro, S.; Niaz, A.; Choi, K. N. Grad++ ScoreCAM: Enhancing visual explanations of deep convolutional networks using incremented gradient and score-weighted methods. IEEE Access 2024.

Figure 1.

Dataset Sample: As per the above image, the acetic acid solution is used in the first two photos, the iodine solution is applied in the last column, and the image from the second-last column is examined via a green lens. This sample belongs to Class 1 (Cervical Neoplasia of the Intraepithelial Layer).

Figure 1.

Dataset Sample: As per the above image, the acetic acid solution is used in the first two photos, the iodine solution is applied in the last column, and the image from the second-last column is examined via a green lens. This sample belongs to Class 1 (Cervical Neoplasia of the Intraepithelial Layer).

Figure 2.

Distribution of primary dataset. The first chart represents distribution of CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3 in the original dataset. The second chart represents distribution of the three classes in the augmented dataset.

Figure 2.

Distribution of primary dataset. The first chart represents distribution of CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3 in the original dataset. The second chart represents distribution of the three classes in the augmented dataset.

Figure 3.

Distribution of secondary dataset. The first chart represents the distribution of CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3 in the original dataset. The second chart represents distribution of the three classes in the augmented dataset.

Figure 3.

Distribution of secondary dataset. The first chart represents the distribution of CIN1, CIN2 and CIN3 in the original dataset. The second chart represents distribution of the three classes in the augmented dataset.

Figure 4.

Forward Pass of the deep neural network.

Figure 4.

Forward Pass of the deep neural network.

Figure 5.

Sample image of three classes of IARC dataset showing denoising and augmentation.

Figure 5.

Sample image of three classes of IARC dataset showing denoising and augmentation.

Figure 6.