1. Introduction

With the ongoing concerns of climate change, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions has become a top international priority. In particular, methane (CH₄) is approximately as 30 times large as the greenhouse effect of carbon dioxide (CO₂), and its increasing concentration in the atmosphere has a significant impact on climate change. In recent years, it has been reported that CH₄ emissions have continued to increase [

1], and there is an urgent need to reduce the emissions. This has prompted all the countries to intensify their efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, especially for the countries where rice is produced in paddy fields, the proper management of CH₄ is urgent.

In Japan, rice paddies are one of the major sources of CH₄ emissions, accounting for 43.6% of all CH₄ emissions in FY2022 [

2]. In rice paddy fields, CH₄ is produced in the soil by microbial activity such as methanogenic bacteria, which are active under waterlogged conditions [

3]. Water management in rice paddies involves maintaining waterlogged conditions from around May, when rice paddies are being plowed and planted, to around October, when rice is harvested, resulting in anaerobic conditions in the soil for a long period. As a result, anaerobic methanogenic bacteria become active, decomposing organic matter in the soil and producing CH₄ [

4,

5]. Furthermore, in paddy fields, incorporating rice straw into paddy soil after harvest is commonly practiced, which contributes to increasing nutrients in the paddy soil improving soil fertility [

6], and increasing paddy rice yield [

7]. On the other hand, incorporating rice straw into paddy soil promotes CH₄ emissions by providing more organic carbon as a substrate for CH₄ production [

8]. Most of the CH₄ produced under anaerobic conditions is absorbed from the root system of aquatic plants, passed through the stem, and emitted into the atmosphere through the leaves [

9]. In rice, CH₄ is emitted by a similar mechanism [

10].

Considering the CH₄ production and emission processes in paddy soils, it is necessary to alleviate the anaerobic conditions of paddy soils to reduce CH₄ emissions. Water management incorporating drying out and intermittent irrigation, meaning alternate wetting and drying (AWD), has been reported to reduce CH₄ emissions effectively [

11]. Midterm drying, popularly conducted in Japan, is a water management method that aims to expose the soil to the air by lowering the water level in the paddy field for a certain period and temporarily drying the soil surface. The AWD is a water management practice in which water is repeatedly added and removed from the soil to suppress anaerobic conditions by not keeping the paddy soil completely waterlogged. Both water management practices are expected to suppress the activity of CH₄-producing bacteria by increasing the soil's redox potential(ORP)to more positive levels. The ORP indicates the strength of the oxidation-reduction potential of the soil, with lower values indicating anaerobic conditions and higher values approaching aerobic conditions. In particular, when ORP falls below -200 mV, CH₄ emissions increase further [

12], but it has been reported that draining paddy soils increases ORP and shifts to aerobic conditions [

13].

On the other hand, it has been reported that in midterm drying and AWD, surface soils are temporarily dried out, especially in AWD, where repeated wet and dry conditions can cause cracks on the soil surface [

14], and that paddy soils that have been dried out by drainage are more prone to weeds than conventionally waterlogged paddy soils reported to be more prone to weed infestation compared to conventionally watered paddy soils [

15,

16]. Additional labor is required for weeding and soil management, and high-performance drainage systems are required, which may be costly in terms of capital investment and maintenance. In recent years, ecological impacts have also become a growing concern, and draining water from rice paddies, even temporarily, can significantly impact the habitat of aquatic organisms in the paddies [

17]. For example, small crustaceans, aquatic insects, and amphibian larvae depend on the water environment, making their survival difficult.

Given these problems, there is a need to develop methods to reduce CH₄ emissions in areas where midterm drying or AWD cannot be implemented. Exploring new options for aerating the soil while maintaining flooded conditions without drainage is necessary.

One method to supply air to the soil while maintaining waterlogged conditions is the micro-nano bubbles (MNB) treatment, which have very small bubble diameters ranging from a few hundred nm to 10 µm, low buoyancy, and a slow ascent rate in water. These characteristics allow them to remain in the water for long periods [

18]. While common bubbles (centimeter bubbles and millimeter bubbles) rise and burst at the water surface immediately after their generation [

19], MNBs have the property of slowly rising, contracting, and dissolving while partially expelling gas [

18]. Due to these properties, the MNB treatment is expected to supply air to paddy soil without eliminating water from the paddy field, thereby alleviating anaerobic conditions in the soil. Such air supply effects have been confirmed in previous studies and are particularly pronounced in submerged environments. For example, it has been reported that the MNB treatment of lakes has significantly increased oxygen concentrations and improved the anaerobic environment of the bottom layer [

20]. Recently, an increasing number of studies have used MNB to improve water quality and survival rates through air supply, as well as to promote the growth and gigantism of organisms, as they are not sufficient to meet the total demand for oxygen needed in intensive aquaculture, such as shrimp and tuna farming [

21]. In the agricultural field, the effect of air supply to plant roots has been confirmed in greenhouse cultivation for strawberries, and together with salad snaps grown in greenhouses, the crops' growth promotion and yield increase have been confirmed. In addition, improved root health has been reported in tomatoes [

21].

However, most studies have focused on the MNB treatment in water or soil, with limited research examining its treatment in water-saturated soil. Few conclusions have been reached regarding its effectiveness or behavior in this context, and studies remain to assess the relationship between soil redox conditions and methane emissions with the MNB treatment. Optimizing the number and spacing of treatment devices is essential for efficient MNB supply when considering treatment in large paddy fields. Additionally, evaluating the horizontal and vertical movement characteristics of MNB in paddy soils has yet to be discovered.

This study aimed to determine whether MNB treatment in rice paddies enhances the air supply to the soil and assess the extent of horizontal MNB distribution and its impact on CH4 emissions.

2. Materials and Methods

This experiment was conducted over two years, in 2022 and 2023, in a lysimeter plot (gray lowland soil fill, 1 plot: 2 m long x 2 m wide x 2 m deep) on the Ikuta campus of Meiji University (Kawasaki, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan). In 2022, the experiment was conducted in two plots, one where MNB was applied (MNB treatment plot) and the other was a control plot that was constantly flooded (3-5 cm water depth) and no MNB treatment plot was applied. The final waterfall was conducted on October 5. In 2023, in addition to these, an AWD plot with repeated flooding and falling water every three days was added, and experiments were conducted in three plots. The final waterfall was on September 15 in all plots. The cultivar grown was Koshihikari (Oryza sativa L. cv. Koshihikari).

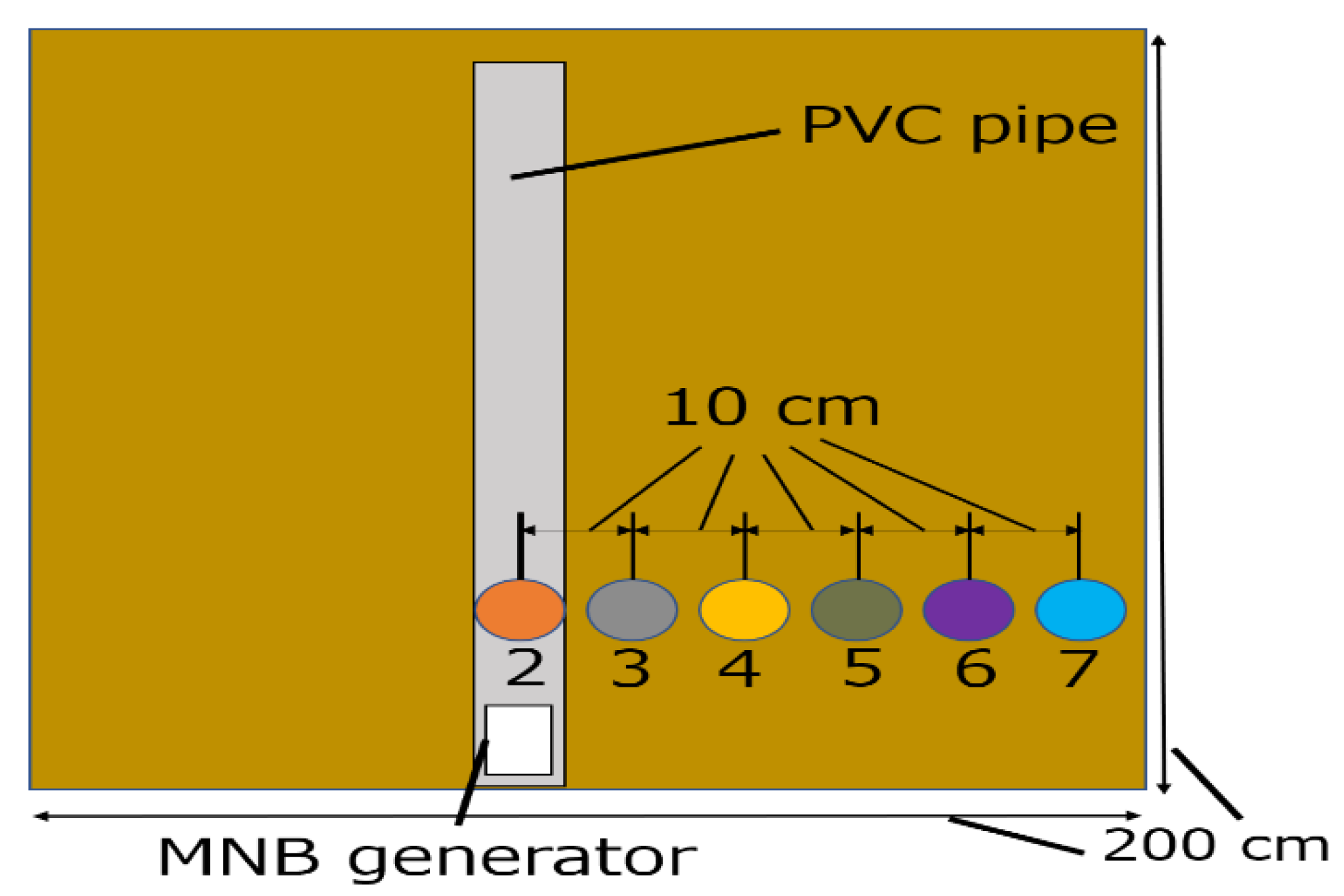

In the MNB treatment plot, PVC pipes 2 m long and 106 mm in diameter were buried to a depth of 30 cm to apply MNB. An elbow was used to connect a rising pipe to one side of the PVC pipe, and the pipe was assembled into an L-shape with 190 cm on the long side and 50 cm on the short side (

Figure 1-a). An MNB generator (Water Navi, Spinol) was inserted into the rising pipe and put into operation.

In 2023, in addition to the MNB treatment plot, similar PVC and rising pipes were buried in the control plot, but the MNB generator was used only in the MNB treatment plot. The particle size of the generated MNBs was tested with a particle size distribution analyzer (Shimadzu, SALD-7500H (WingSALD bubble: Version 3.3.2)) after the experiment, and the average particle size was 2.26 μm. The MNB generated by drilling numerous 12-mm-diameter holes (

Figure 1-b) in the buried PVC pipe was allowed to spread into the paddy soil; MNB application started on June 15 and stopped on October 5 in 2022; in 2023, it started on July 25 and stopped on September 15. In 2022, the equipment was operated 24 hours a day, but it was confirmed that the equipment may have been overheated by the heat generated during MNB production and the outside temperature, which may have interfered with the MNB production. Therefore, in 2023, operation was stopped during the daytime when the temperature was high in order to prevent overheating of the device.

Methane emissions were measured using a closed chamber method. Once a week, gas emitted from the paddy field was collected and analyzed with a gas chromatograph with FID (Agilent 6890N). The temperature inside the chamber was measured at the time of gas collection, and the height of the chamber from the water surface was measured at the end of gas collection. Gas sampling was conducted once a week, starting at 13:00-14:00. The gas concentration in the chamber was determined by the equation (1) [

22]. The surface gas flux Qeffl was calculated according to equation (1) [

23].

Where ρ

g is the gas density under standard conditions, T (°C) is the air temperature inside the chamber, a (m³/m³/s) is the slope of the linear approximation of the relationship between the gas concentration and the gas measurement time, h (m) is the height above the ground of the space inside the chamber after the chamber installation, and b

g is the ratio of the amount of C molecules to the amount of CH₄ molecules. In the first-order approximation of the CH₄ concentration, obvious outliers are excluded. The integrated gas flux was obtained from equation (2) [

24].

Tn is the integrated gas flux (mg m-2 period-1), ti is the time of the i-th gas measurement (h), and fi is the gas flux at the i-th measurement (mg m-2 h-1).

In 2022, auto chambers were installed at three locations in the control plot, three locations directly above the buried PVC pipes in the MNB treatment plot, and three locations 50 cm horizontally away from the PVC pipes, for a total of nine locations. 2023, cylindrical acrylic chambers were used to collect gas at three locations in the control and MNB treatment plots, as well as in the AWD plot for a total of 12 locations for gas sampling.

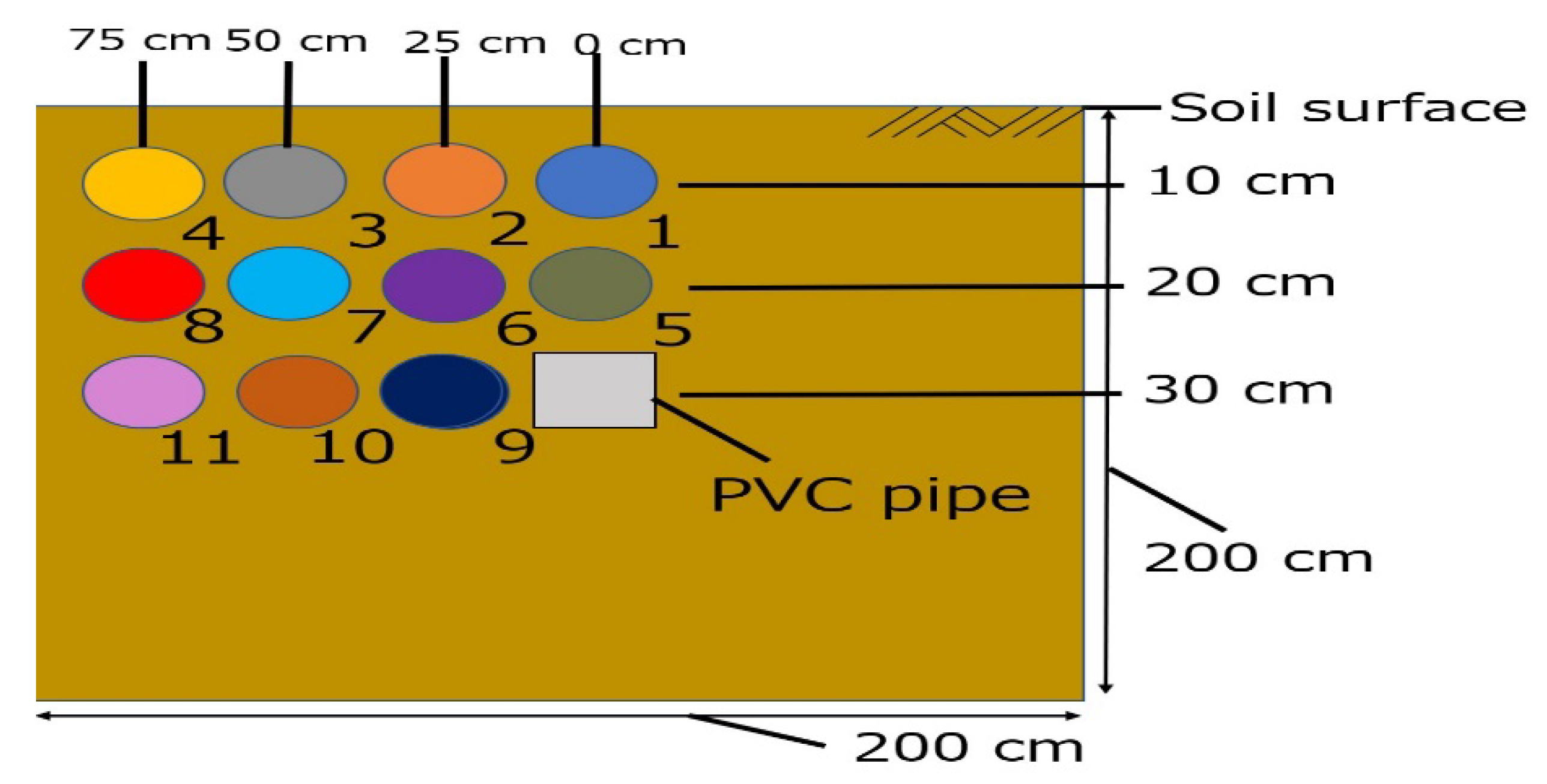

To evaluate the horizontal migration of MNB, redox potentials were measured using platinum electrodes. Using a data logger (Campbell, CR3000), a total of 12 platinum electrodes were installed in 2022, 11 in the MNB treatment plot (

Figure 2) and 1 in the control plot (at the same location as MNB treatment plot #1), and measurements were taken at 1-minute intervals. In 2023, a total of eight MNB treatment plots were installed: one in the control plot, six in the MNB treatment plot (

Figure 3), and one in the AWD plot. We expected the redox potential to change in the direction of oxidation at the MNB treatment sites and used this variation as an indicator to assess the spread of MNB.

3. Results

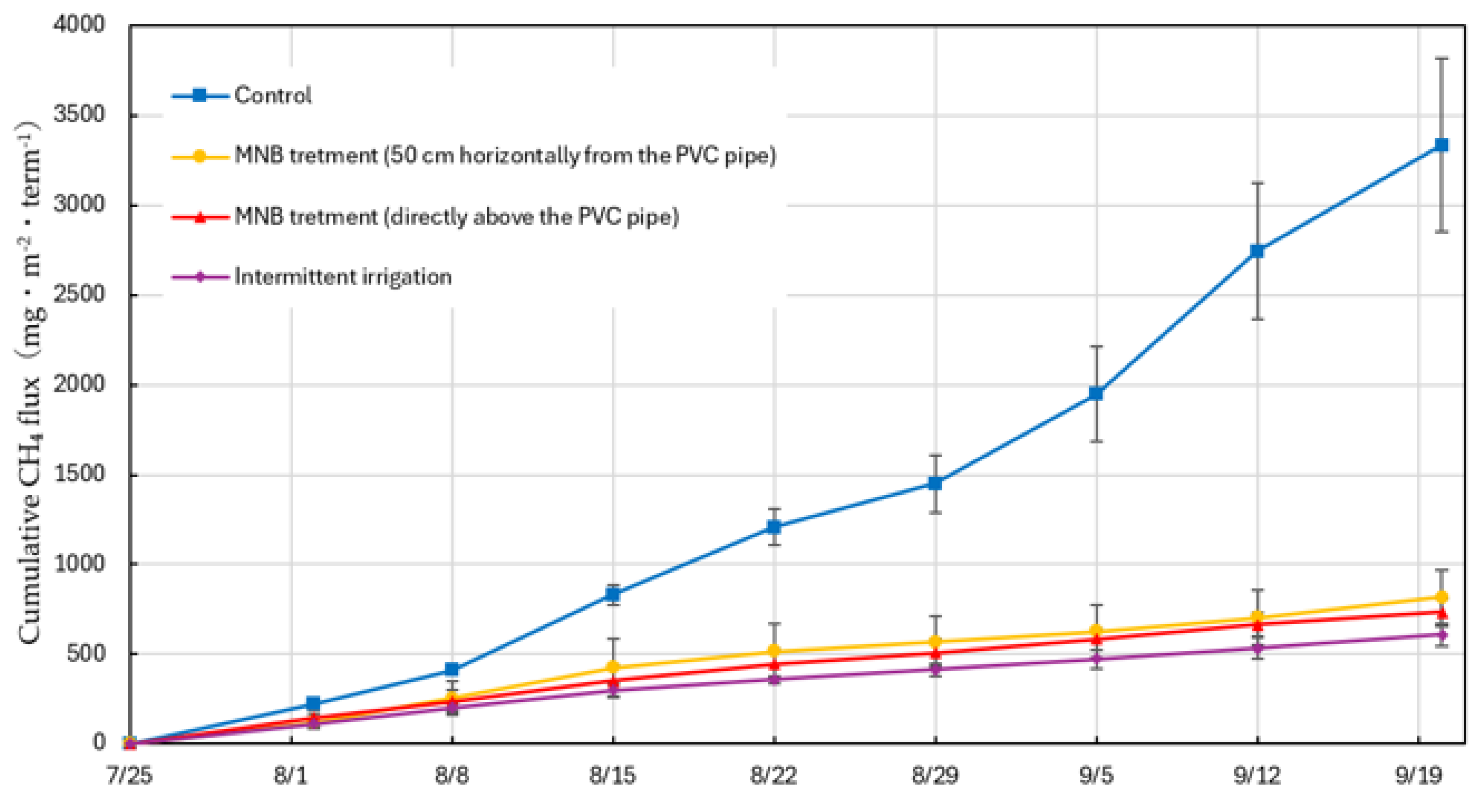

Table 2022 is shown in

Figure 4. These data were obtained from 10 gas sampling events from July 26 to September 27, 2022. At the end of the experiment, the integrated flux directly above the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot was 843.0 mg・m⁻²・term⁻¹, a 27.6% reduction in emissions compared to the 1165.1 mg・m⁻²・term⁻¹ of the control plot. On the other hand, at a distance of 50 cm from the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot, there was no distinctive difference from the control plot.

Next, the integrated CH₄ gas flux in 2023 is shown in

Figure 5. These data are shown for the gas collection period from July 25 to September 20, 2023. At the end of the experiment, the total emissions directly above the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot were 732.1 mg・m⁻²・term⁻¹, a 78.1% reduction compared to 3335.5 mg・m⁻²・term⁻¹ in the control plot. At 50 cm from the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot, emissions were also reduced by 75.5% compared to the control plot, totaling 815.7 mg・m⁻²・term⁻¹. These values were similar to the CH₄ emissions of 608.0 mg・m⁻²・term⁻¹ in the AWD plot, which showed an 81.8% reduction compared to the control plot.

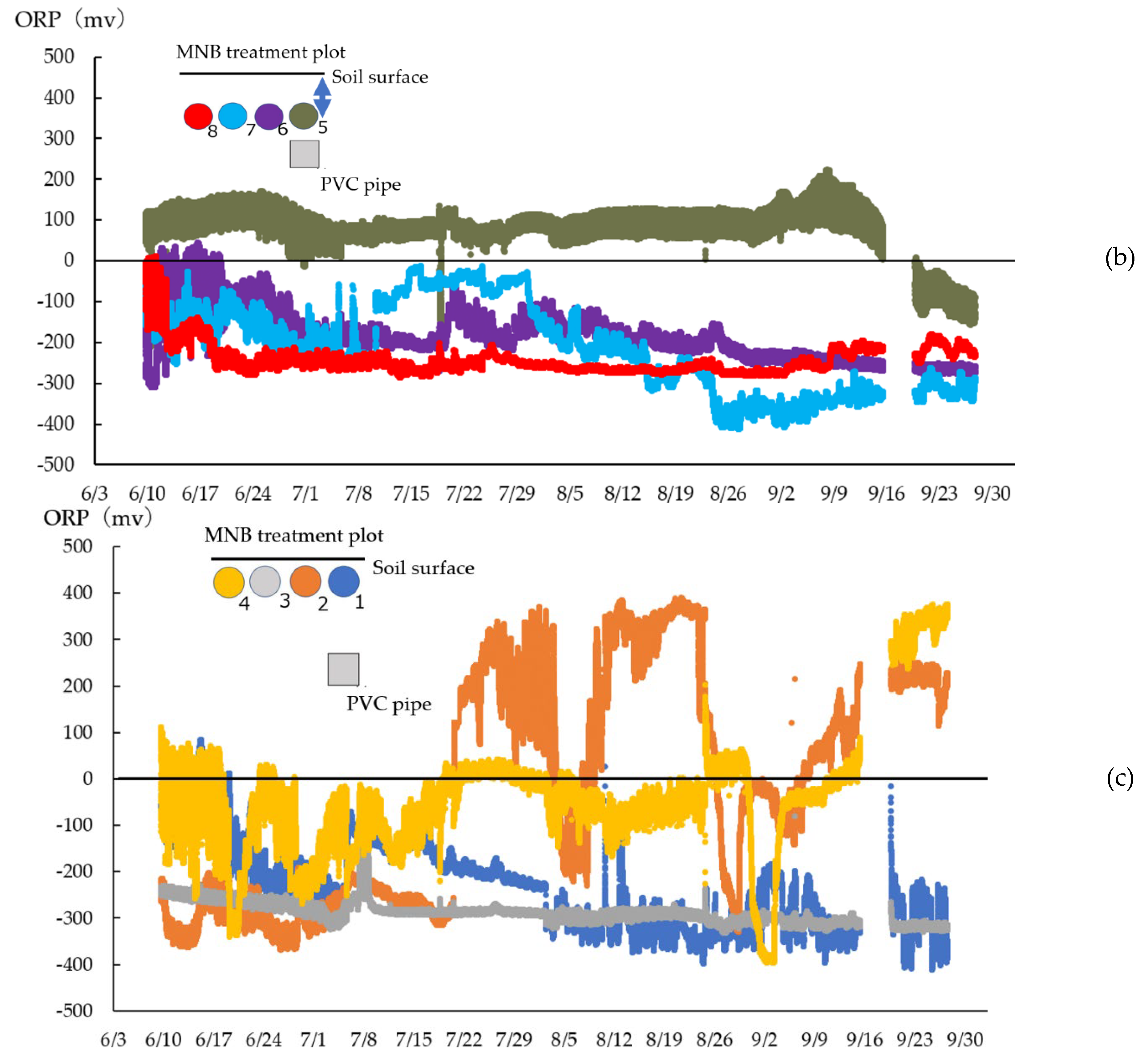

Figure 7 shows the redox potential data for the year 2022. At a depth of 30 cm (

Figure 6-a), the reduction state was maintained at No. 9 (25 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe) and No. 11 (75 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe), and no transition into the oxidized state was observed. At No. 10 (50 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe), the oxidized state alternated with the reduced state. At the 20 cm depth (

Figure 6-b), the oxidation state was last until September 13 at No. 5, just above the PVC pipe, but the redox potential began to decrease from September 14, and the state shifted to the reduced condition. At No. 7 (50 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe), the oxidization started on July 10, and values near 0 mV were recorded for 20 days. At No. 8 (75 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe), the reduction state started on June 17, and the condition remained after that, and no significant change occurred. At a depth of 10 cm (

Figure 6-c), a significant shift toward oxidation was observed at No. 2 (25 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe) and No. 4 (75 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe). In comparison, at No. 3 (50 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe), a shift toward oxidation was observed on July 7, but the reduction state was maintained after that. At No. 1, which was directly above the PVC pipe, a shift toward oxidation was observed in July, and after August 1, it fluctuated slightly but remained reduced.

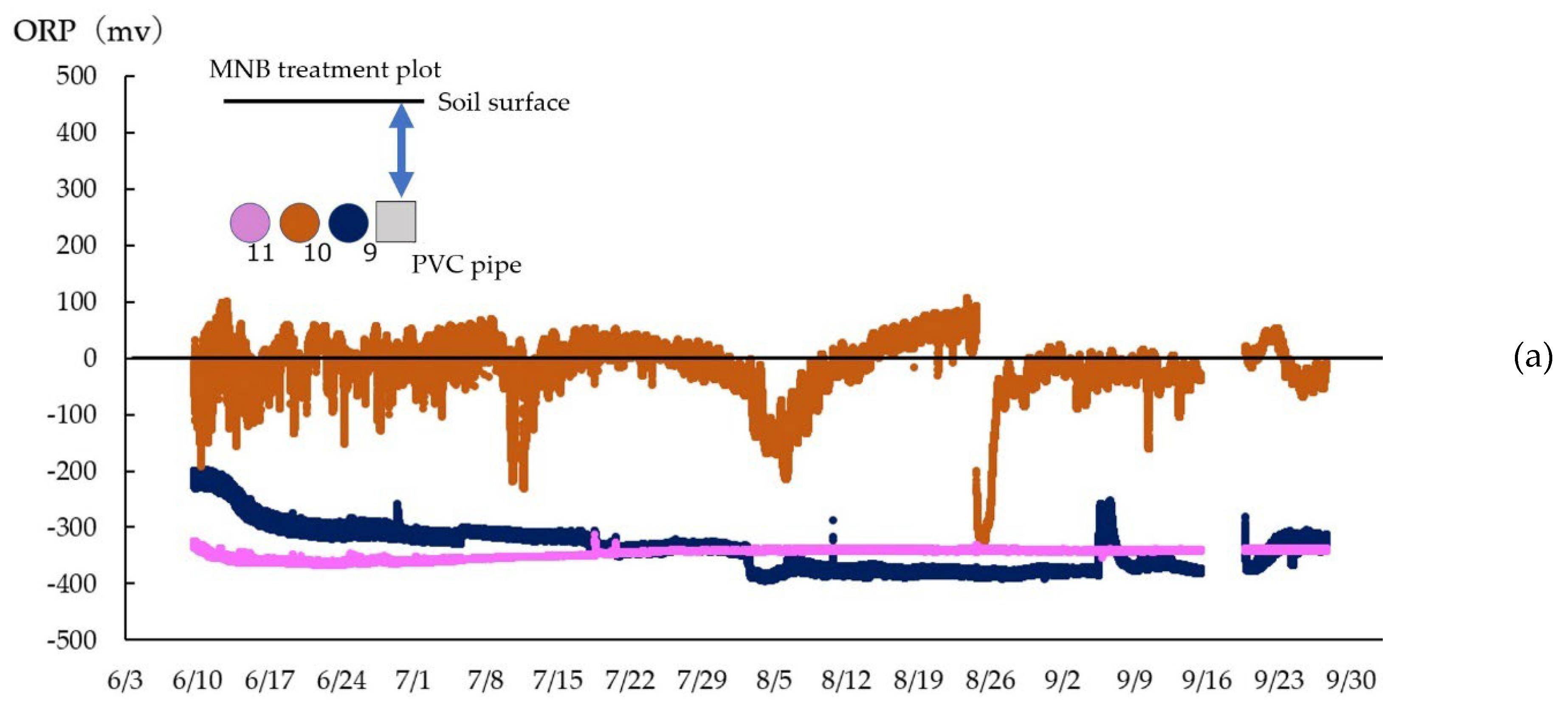

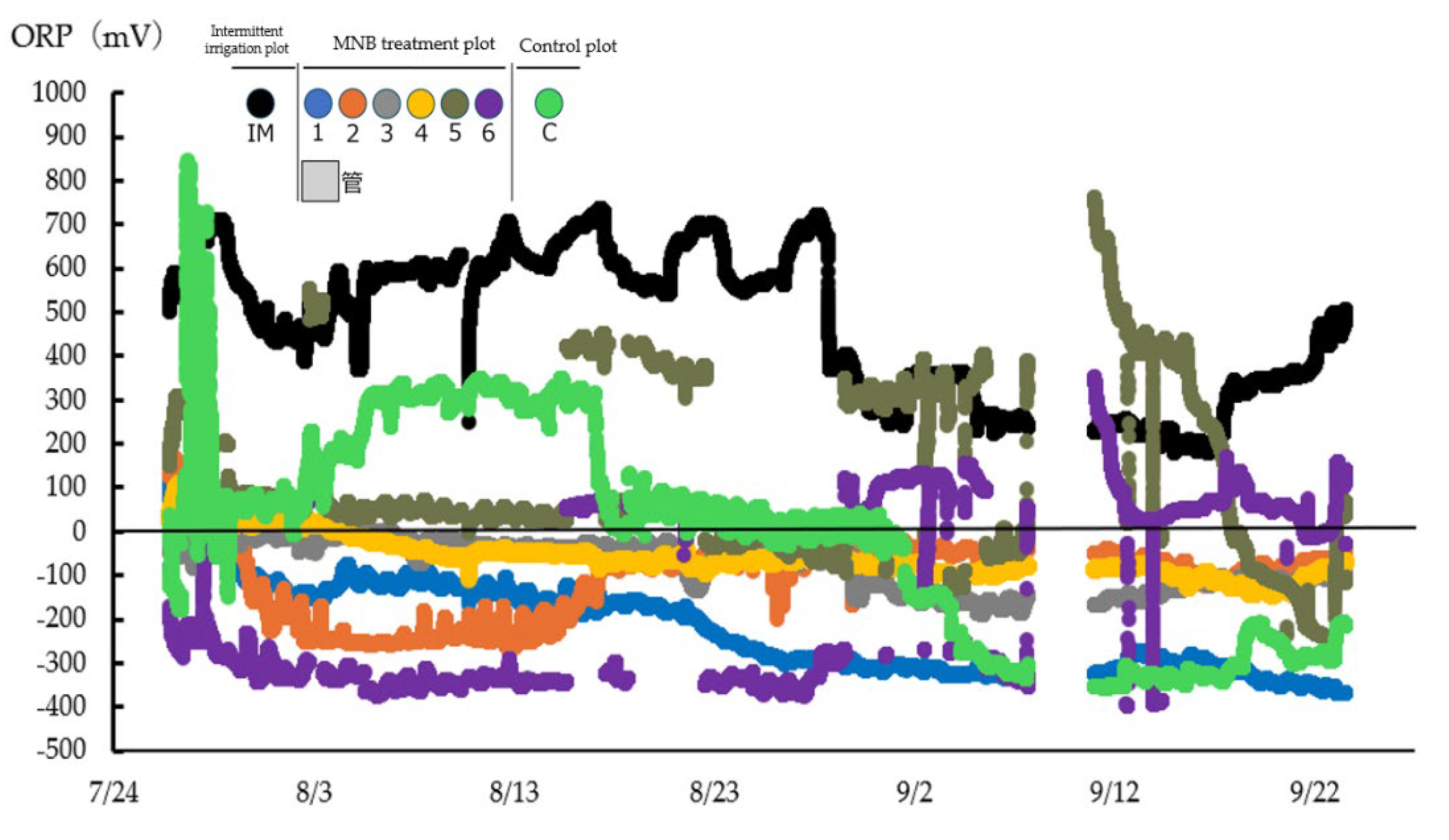

Figure 7. shows temporal changes in the redox potential in 2023. Continuous oxidation was observed at No. 2 (10 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe) and No. 5 (40 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe), and irregular oxidation was also observed at No. 6 (50 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe). On the other hand, no significant change in redox potential was observed at No. 3 (20 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe) and No. 4 (30 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe), and they maintained their reduced state and showed a leveling off trend. At No. 1, which is directly above the PVC pipe, there was a gradual shift toward a reduced state throughout the entire period of the study. In the control site, a pronounced shift toward oxidation occurred from August 3 to 17, and the shift toward reduction continued from August 18 onward.

4. Discussion

The two-year CH₄ gas flux data suggest that supplying MNB through the PVC pipe in the soil under waterlogging conditions would be effective in reducing CH₄ emissions and would be as effective as AWD conditions. The CH

4 flux in the control plot in 2023 was higher than in 2022, presumably because the amount of soil organic matter, which is the substrate for CH₄, was increased in 2023 compared to 2022 due to the straining of rice straw in all plots before the 2023 experiment started, as CH₄ emissions were generally lower in the 2022 experiment [

8].

Based on the results of the redox potential fluctuations of No. 9 and No. 11, which were placed at a depth of 30 cm in 2022, it was suggested that MNB did not spread horizontally from the PVC pipe at a depth of 30 cm. In the lysimeter used in this experiment, the water flow was from the bottom to the top, which made it difficult for MNB to move horizontally from the PVC pipe. Thus, the soil in No. 10 tended to be in an oxidative condition, and it was thought that an air pathway was left behind when the electrodes were installed.

The redox potential data of the No. 5 electrode at 20 cm in depth suggested that strong oxidation occurred just above the PVC pipe at the MNB treatment plot, and the results of the No. 6 and No. 7 electrodes indicated that MNB reached 50 cm horizontally at 10 cm above PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot (20 cm depth from the soil surface). On the other hand, the No. 7 electrode turned to the reduction direction after August, but the rhizosphere of rice blocked the path of MNB, possibly preventing it from reaching. The result of the No. 8 electrode, in which the soil tended to be reduced in June and remained stable, suggests that MNB did not reach a point 10 cm above and 75 cm away horizontally from the PVC pipe.

At a depth of 10 cm, a significant shift in the oxidation direction was observed in plots 2 and 4, but this could be due to soil disturbance by weeding that affected the change in redox potential because the date and time of weeding in the experimental plots coincided with the change in redox potential. Therefore, it was impossible to determine whether the effect was due to weeding or oxidation by MNB. The No. 3 electrode was close to the location of the auto chamber and could not be actively weeded during the experiment. Therefore, it was assumed that the redox potential remained constant because air pathways were not formed by weeding, as with the No. 2 and 4 electrodes. At the No. 1 electrode, a transition in the oxidation direction was observed from July 5 to 6, but after August 4, the transition between oxidized and reduced states was repeated in small increments. Although No. 1 was close to the location where the auto chamber was installed, it was close to the board that was passed to enter the plot when the gas was collected and weeding could be performed, so it was thought to have been affected by soil disturbance caused by weeding. The results from Nos. 1 through 4 electrodes at a depth of 10 cm suggested that MNB did not reach 20 cm above the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot.

The data in 2023 at the No. 2 and No. 5 electrodes for the redox potential suggested that MNB reached a point 40 cm horizontally from and 15 cm above the PVC pipe at the MNB treatment site. The data at No. 6 suggests that MNB reached a point 15 cm above and 50 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe, although not constantly. The results of the 2023 integrated flux also suggested that even at 50 cm away from the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot, the arrival of MNB and the discontinuous supply of MNB effectively reduced CH₄ emissions. On the other hand, the redox potential values remained unchanged at sites 3 and 4, in addition to site 6, in which MNB did not reach the site, which may have inhibited the spread of MNB through the development of the rhizosphere. Unlike the 2022 results, the No. 1 electrode directly above the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot, which showed a tendency to the reduced condition, was the only electrode installed that did not show a tendency to the oxidized condition when all the plots were drained out for harvest in late September. This suggested the erroneous measurement was due to equipment failure at the No. 1 electrode in the MNB treatment plot. In particular, the electrode readings changed to the reduced condition after August 22. They remained in the reduced condition until the end of the experiment, suggesting that the electrode may have malfunctioned after that date at the No. 1 electrode in the MNB treatment plot. However, from August 5 to August 22, the electrode also showed small increments in the oxidative direction, suggesting that the MNB did not reach the electrode sufficiently. In the control plot, after a pronounced oxidative shift in August, the electrode's reading shifted in a reducing direction, suggesting that an air pathway may have remained at the time of electrode installation.

It has been reported that the root system of Koshihikari is shallow, with about 80% of its total root length residing up to 10 cm in depth [

25]. On the other hand, for rush [

26] and lettuce [

27], bubble treatment has been shown to promote root fullness and elongation, and MNB treatment may have moved the rhizosphere deeper than 10 cm depth in this study. In addition, roots may inhibit migration by attaching MNB [

28]. In this study, MNB may have attached to the rhizosphere that developed at a depth deeper than 10 cm, preventing migration to a depth of 15 cm or more. Furthermore, a rhizosphere may have also developed at a 20 cm depth that prevented MNB from reaching the depth of 20 cm. Still, since this depth is below the rhizosphere, it was inferred that the effect of the rhizosphere was more limited than at the 10 cm depth.

5. Conclusions

The MNB treatment reduced CH₄ emissions by 24.9% (2022) and 78.1% (2023), at least in the plot directly above the PVC pipe in the MNB treatment plot, compared to the control plot. In 2023, the irrigated plot was also reduced by 75.5% compared to the control plot at 50 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe. The AWD plot reduced CH₄ emissions by 81.8% compared to the control plot, suggesting that the MNB treatment has a similar effect to supplying air to saturated soil and reducing CH₄ emissions as AWD. Although the MNB spreads up to 15 cm above and 50 cm horizontally from the PVC pipe, its reach may depend on the development of the rhizosphere and the relationship with the root gap created by mortality, and further study is needed. Furthermore, since the lysimeter used in this experiment was a facility where water movement was from bottom to top, verifying whether the same results could be obtained when MNB was treated in an actual paddy field where water moves from top to bottom is necessary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K. and M.T.; Methodology, R.S.; Software, R.S. and T.D.; validation, R.S.; formal analysis, R.S.; investigation, R.S., A.H.M., K.M. and T.D.; resources, T.K. and K.N.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.; writing—review and editing, T.D. and K.N.; visualization, R.S.; supervision, M.T. and K.N.; project administration, M.T.; funding acquisition, M.T and K.N.

Funding

This research was funded by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Budding Researchers), grant number 21K19182 (PI: MT).

Acknowledgments

RS would like to thank my laboratory members for their great.cooperation in gas sampling.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report that this study was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report; IPCC, 2023. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_FullVolume.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- National GHG Inventory Document of JAPAN. Available online: https://www.nies.go.jp/gio/en/archive/nir/pi5dm3000010ii0r-att/NID-JPN-2024-v3.0_gioweb.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Angel, R.; Claus, P.; Conrad, R. Methanogenic archaea are globally ubiquitous in aerated soils and become active under wet anoxic conditions. The ISME Journal. 2012, 6, 847–862. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, H.A.; Buswell, A.M. Biological Formation of Methane. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 1956, 48, 1438-1443.

- Conrad, R. Methane Production in Soil Environments-Anaerobic Biogeochemistry and Microbial Life between Flooding and Desiccation. Microorganisms. 2020, 8, 881. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yuan, G.; Wang, H.; Lu, D.; Chen, X.; Zhou, J. Effects of Full Straw Incorporation on Soil Fertility and Crop Yield in Rice-Wheat Rotation for Silty Clay Loamy Cropland. Agronomy. 2019, 9 133.

- Marumoto, T.; Matuura, K.; Shindo, H.; Higashi, T. Effect of rice straw application on transplanted paddy rice (in Japanese). Academic Report, Faculty of Agriculture, Yamaguchi University. 1982, 33, 49-66.

- Liu, C.; Lu, M.; Cui, J.; Li, B.; Fang, C. Effects of straw carbon input on carbon dynamics in agricultural soils: a meta-analysis. Global Change Biology. 2014, 20, 1366-1381. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacey, J.W.H.; Klug, M.J. Methane Efflux from Lake Sediments Through Water Lilies. Science. 1979, 203, 1253-1255. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Neue, H.U.; Samonte, H.P. Role of rice in mediating methane emission. Plant and Soil. 1997, 189, 107-115.

- Goto, E.; Miyamori, Y.; Hasegawa, S.; Inatsu, O. Methane production reduction by rice straw decomposition promotion and water management in cold-weather rice paddies (in Japanese). Journal of the science of soil and manure, Japan. 2004, 75, 191-201.

- Oishi, O.; Hamamura, K.; Utsunomiya, A.; Murano, K.; Bandow, H. Measurement of Methane Flux from a Rice Paddy. Journal of Air Pollution, Japan. 1994, 29, 145-150.

- Xu, C.; Chen, L.; Chen, S.; Chu, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D. Effects of Soil Microbes on Methane Emissions from Paddy Fields under Varying Soil Oxygen Conditions. Agronomy Journal. 2018, 110, 1738-1747.

- Haque, A.N.A.; Uddin, M.K.; Sulaiman, M.F.; Amin, A.M.; Hossain, M.; Solaiman, Z.M.; Mosharrof, M. Biochar with Alternate Wetting and Drying Irrigation: A Potential Technique for Paddy Soil Management. Agriculture. 2021, 11, 367. [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.M.; Alam, M.S.; Kabir, M.H.; Khan, A.K.; Islam, M.M. Water Saving Irrigation in Rice Cultivation with Particular Reference to Alternate Wetting and Drying Method: An Overview. The Agriculturists. 2010, 7, 128. [CrossRef]

- Suryakala, A.; Sagar, G.K.; Kumar, R.M.; Pratibha, G.; Umamahesh, V.; Murthy, B.R. Impact of irrigation regimes on weed dynamics in various rice establishment methods. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2023, 12, 27-30. [CrossRef]

- Naito, R.; Yamasaki, M.; Imanishi, A.; Natuhara, Y.; Morimoto, Y. Effects of Water Management, Connectivity, and Surrounding Land Use on Habitat Use by Frogs in Rice Paddies in Japan. ZOOLOGICAL SCIENCE. 2012, 29, 577-584. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohnari, H.; Tsunami, Y.; Ohnari, H.; Yamamoto, T. GENERATING MECHANISM AND SHRINKING CHARACTERISTIC OF MICRO BUBBLES. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, Japan. 2006, 50, 1345-1350.

- Takahashi, M. Water Treatment Based on Microbubble Technology. Bulletin of the Society of Sea Water Science, Japan. 2010, 64, 19-23.

- Sasaki, H.; Sasaki, A.; Takeda, M.; Okano, T.; Adachi, Y. Understanding the effect of dissolved oxygen supply using microbubble generators in closed water bodies (in Japanese). Journal of Coastal Engineering, Japan. 2006, 53, 1171-1175.

- Himuro, S. Biological Applications of Fine Bubbles. Japanese Journal of Multiphase Flow. 2016, 30, 10-18. [CrossRef]

- De Mello, W.Z.; Hines, M.E. Application of static and dynamic enclosures for determining dimethyl sulfide and carbonyl sulfide exchange in Sphagnum peatlands: Implications for the magnitude and direction of flux. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 1994, 99, 14601-14607.

- Fujikawa, T.; Takamatsu, R.; Nakamura, M.; Miyazaki, T. Variable system of carbon dioxide gas emission from agricultural soil to the atmosphere and its evaluation (in Japanese). Japanese Society of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2007, 78, 487-495.

- Mori, A.; Hojito, M.; Shimizu, M.; Matsuura, S.; Miyaji, T.; Hatano, R. N2O and CH4 fluxes from a volcanic grassland soil in Nasu, Japan: Comparison between manure plus fertilizer plot and fertilizer-only plot. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition. 2008, 54, 606-617. [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Yamada, S.; Abe, A. Analysis of root system morphology of rice (in Japanese). Crop Science Society of Japan Article. 1995, 64, 58-65.

- Kihara, K.; Yoshida, S. Biomass Evaluation of Agricultural Plants Grown with Intermittent Microbubble Aided Water Irrigation. Kumamoto National College of Technology Research Bulletin. 2017, 9, 25-32.

- Park, J.S.; Kurata, K. Application of Microbubbles to Hydroponics Solution Promotes Lettuce Growth. HortTechnology. 2009, 19, 212-215. [CrossRef]

- Minagawa, H.; Fujiwara, K.; Kurimoto, R.; Yasuda, T.; Harada, E.; Hata, N. Effects of Microbubbles on Germination and Growth of Spinach. Experimental mechanics, Japan. 2016, 16, 77-83.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).