1. Introduction

Enteroviruses are a genus of viruses in the family Picornoviridae, including positively polar single-stranded, single-stranded, non-enveloped RNA viruses with a genome length of about 7500 nt. Enterovirus infections are primarily enteric and cause infections ranging from asymptomatic and mild flu-like colds to serous meningitis and poliomyelitis [

1]. According to modern classification, all viruses belonging to the genus

Enterovirus are divided into nine distinct species:

Enterovirus A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, and J. Additionally, three rhinovirus species were identified:

Rhinovirus A, B, and C [

2].

Small genome of

Enteroviruses encode regulatory proteins that manipulate with are heavily relied on a host factors to entry Different species, serotypes and individual strains of

Enteroviruses can enter cells using a variety of cell surface proteins that act as receptors for viral attachment and subsequent endocytosis [

3,

4]. Polioviruses (PV) (

Enterovirus C) gain entry to cells by binding to the surface protein CD155, a product of the

PVR gene. This protein plays a role in the formation of intercellular adhesion junctions between epithelial cells [

5] and in some intercellular regulatory interactions in immune cells [

6]. Coxsackie B (CVB) and certain echoviruses (E) belonging to

Enterovirus B employ the CAR immunoglobulin superfamily protein, a product of the

CXADR gene [

7,

8]. Some members of Coxsackie A (CVA), including CVA7, CVA14, CVA16, and Enterovirus 71 (EV-A71) (

Enterovirus A), utilize the type B2 scavenger receptor (SCARB2) [

9], also known as lysosomal integral membrane protein II, LIMP-2v or CD36b-like protein-2, which is involved in vesicular transport [

10]. E1 (

Enterovirus B) has been demonstrated to utilize integrin α2β1 (VLA-2; collagen and laminin receptor) [

11,

12], CVA9 (

Enterovirus B) utilizes the αVβ and αVβ6 integrins [

13,

14], CVA21 [

15,

16] and CVA11 [

17] (

Enterovirus C) utilizes an integrin molecule ICAM-1, and many members of the echovirus group (

Enterovirus B) utilize the neonatal Fc receptor FcRn, which consists of two subunits, the

FCGRT gene product and β2-microglobulin [

18]. In addition to these receptors, some enteroviruses may also bind the CD55 co-receptor, or DAF, which normally protects cells from the toxic effects of complement [

15,

19,

20]. The binding of the virus to CD55 does not stimulate the uncoating and release of the viral genome; however, it does promote virion attachment to the cell surface, thereby increasing the likelihood of binding to another receptor on the cell surface [

21].

The RNA genome of enteroviruses is unstable and subject to frequent mutations and recombinations, which occur predominantly among members of the same species and determine their evolution [

22]. Recombinations and mutations can lead to the emergence of new strains [

23] with altered drug resistance, virulence, antigenicity and transmissibility, and in some cases it is associated with changes in the receptor through which the virus enters the cell [

24].

Non-pathogenic and recombinant strains of enteroviruses extensively investigated as potential agents for oncolytic virotherapy [

25,

26] and some strains are approved the for melanoma treatment in Latvia [

27,

28]. The high recombination ability of enteroviruses facilitates the creation of improved oncolytic strains with increased specificity to tumor cells by altering the tropism of the virus [

29]. The efficacy of oncolytic therapy is contingent upon the identification of the receptor utilized by a specific strain and the presence of this receptor on the surface of cancer cells [

30]. It is therefore imperative to develop a rapid and straightforward method for determining the receptor utilized by enteroviruses for cellular entry in order to accelerate the development of effective patient-specific virus-based cancer therapy.

In this study, we have established a panel of cells with knockouts of various receptors employed by enteroviruses for cellular invasion, thereby enabling us to ascertain the receptors essential for enterovirus infection of cells.

2. Results

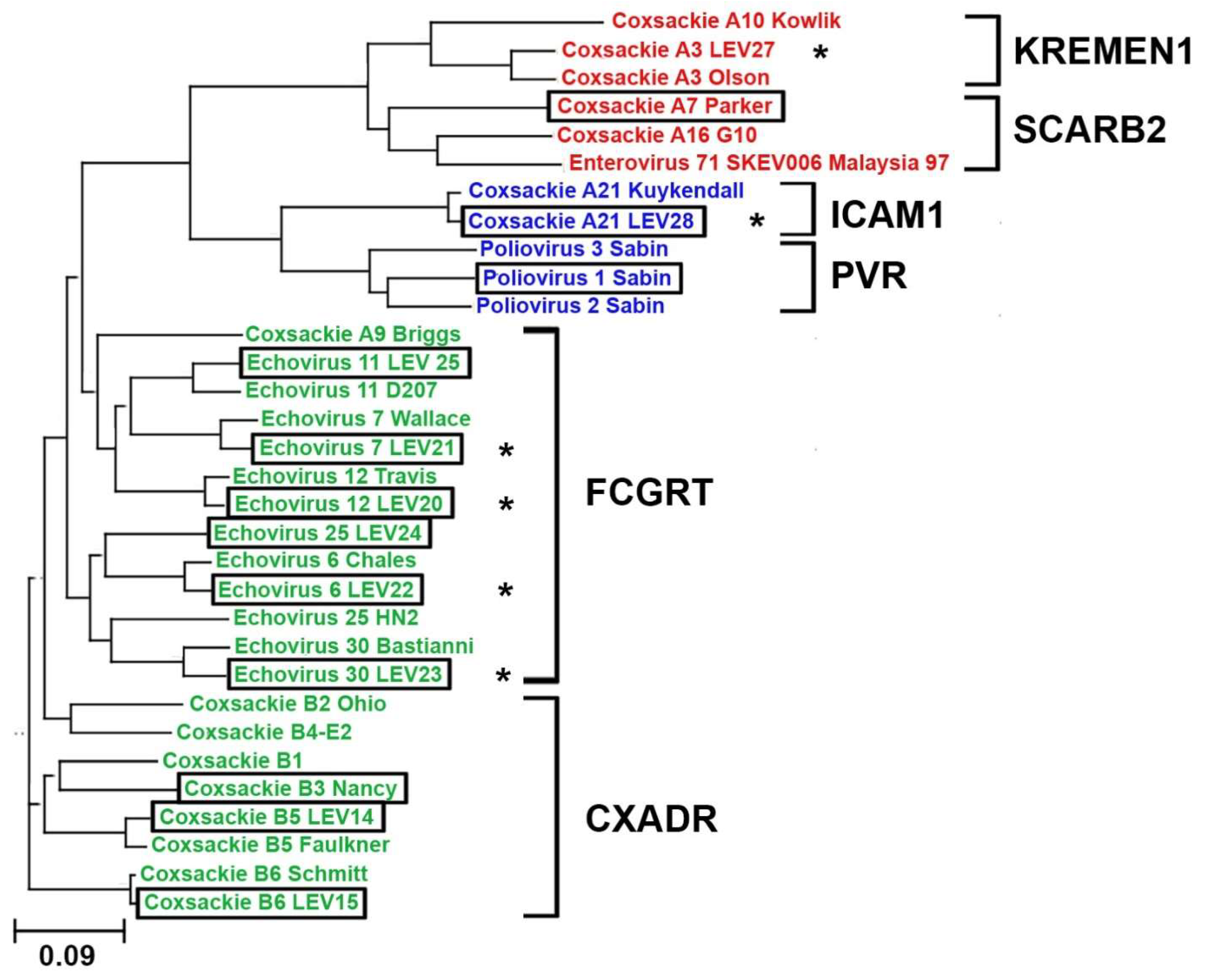

2.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of Enteroviruses

A phylogenetic analysis was conducted on the structural protein sequences of 32 enterovirus strains. The sequences of 22 strains were obtained from the GeneBank database, and the sequences of 10 strains were obtained from the laboratory collection of live vaccine enteroviruses, including six new strains whose genomes were sequenced. It is noteworthy that the novel strains exhibited a high degree of similarity to their respective prototypes, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Moreover, phylogenetic analysis facilitated the prediction of the receptor utilized by the novel viral strain for cellular entry. So, our data suggest that the novel strain Coxsackie A21 (LEV28) strain should interact with ICAM1, and the echovirus strains 7 (LEV21), 12 (LEV20), 6 (LEV22), and 30 (LEV23) should enter cells via interaction with FCGRT. The construction of the phylogenetic tree did not allow for the identification of viruses that utilize CD55 to infect cells in a discrete cluster. This may be attributed to the role of CD55 in cell infection, as it solely facilitates virion attachment to the cell surface [

21].

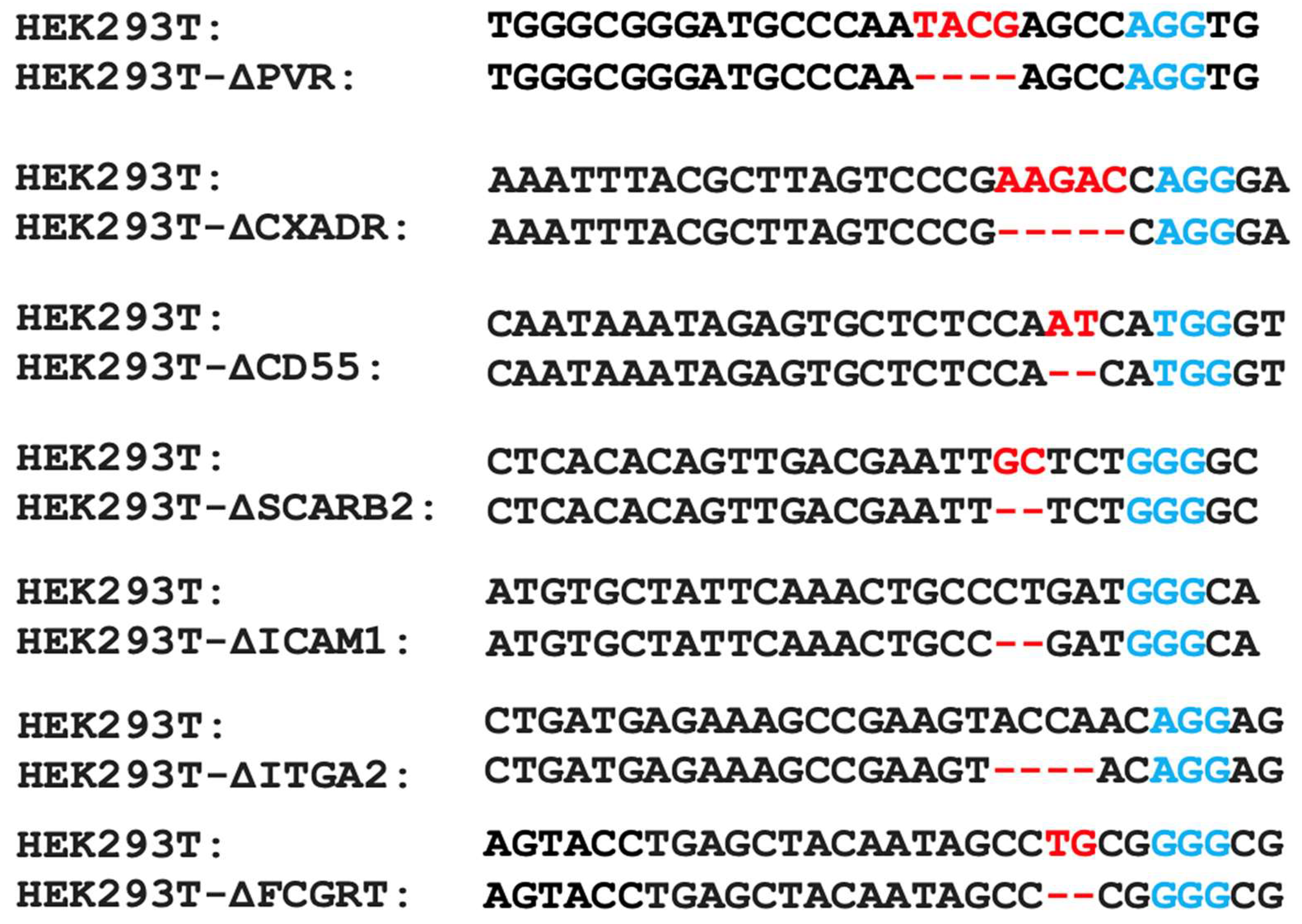

2.2. Obtaining a Panel of Cell Lines with Knockouts of Different Enterovirus Receptors

The results of the phylogenetic analysis need experimental verification. Consequently, we devised an experimental approach for the validation of viral receptors. The experimental approach is based on testing the reproduction of enteroviruses in seven HEK293 lines carrying knockouts of known enteroviral receptors.

To obtain knockout lines, a CRISPR/Cas9 system was employed to target genes encoding seven surface molecules (PVR, CXADR, CD55, SCARB2, ITGA2, ICAM1, and FCGRT) for which a role as an enteroviral receptor or coreceptor has been described. Each gene knockout was introduced into the HEK293T∆IFNAR1 cell line, which had previously been generated by knockout of the IFNAR1 gene encoding the type I interferon receptor subunit [

31]. This cell line, due to its impaired cellular interferon response, is capable of supporting the replication of a large number of enteroviruses, including nonpathogenic ones.

The cells were transfected with the pCas-Guide-P2A-RFP plasmid, which contains inserted sites encoding gRNA spacers targeting the corresponding gene. Following transfection, monoclonal cultures were obtained and subsequently analyzed by sequencing the Cas9-targeted gene region. The most promising clones were then selected based on the results of this sequencing. Consequently, a panel of seven HEK293T cell lines with two gene knockouts (

IFNAR1 and one of the genes encoding receptor proteins for enteroviruses) was obtained (

Figure 2). Knockout cell lines were tested by western-blotting analysis, confirming the absence of the proteins of interest.

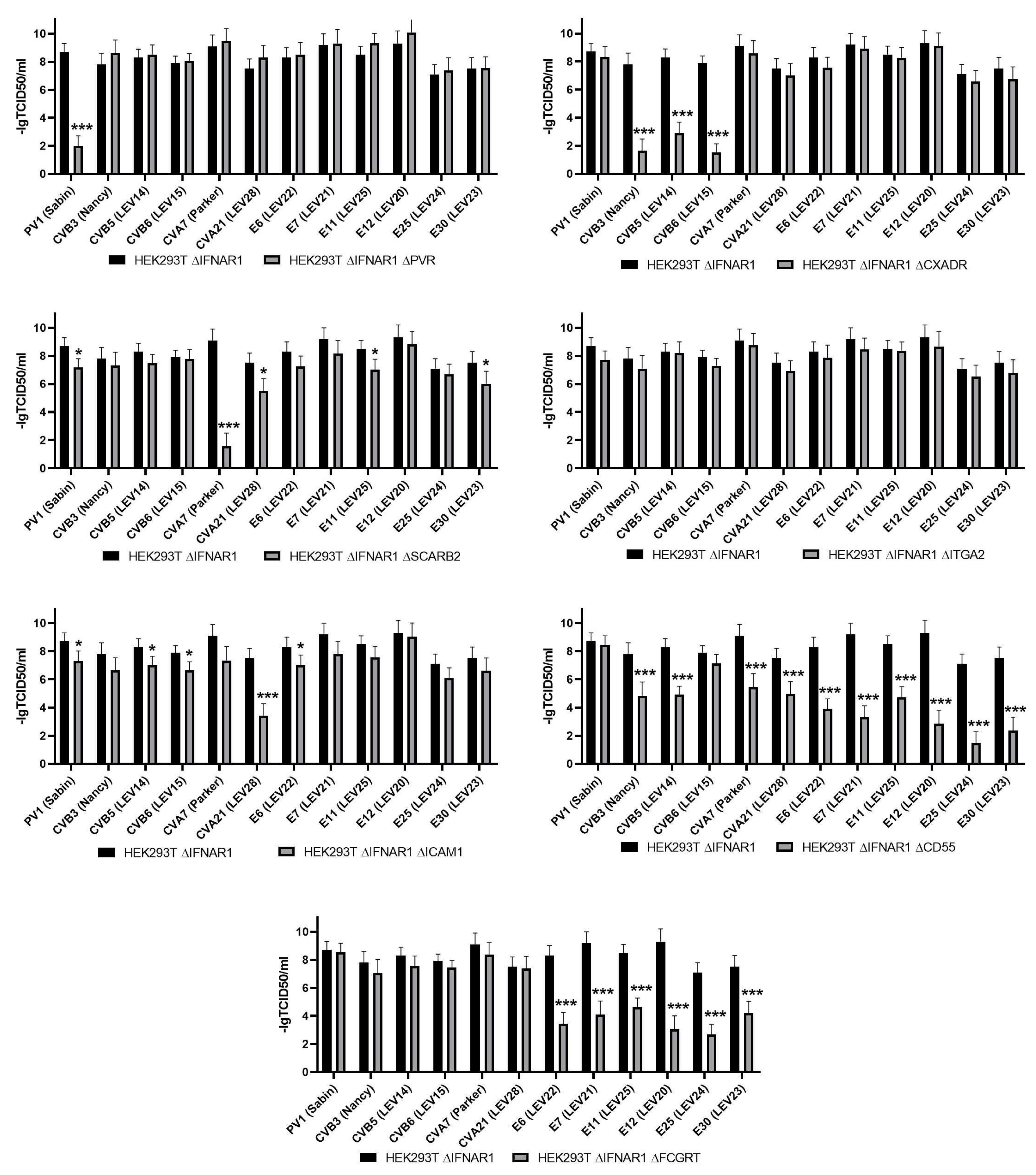

2.3. Evaluation of Enterovirus Reproduction in a Panel of Cells with Viral Receptor Knockouts

The objective of this study was to assess the reproduction of 12 different enteroviruses on the HEK293T∆IFNAR1 cell line and its derivatives with an additional knockout of one of the viral receptors. The results of this assessment are presented in

Figure 3.

As can be observed, the knockout of PVR resulted in a notable reduction in PV1 (Sabin) production. The replication of all other strains remained unimpaired, which is consistent with the data on the receptor properties of PVR [

32].

The inactivation of

CXADR gene expression resulted in the prevention of replication only for coxsackieviruses of group B (CVB3 (Nancy), CVB5 (LEV14), and CVB6 (LEV15)), which is consistent with the available data on the role of the

CXADR gene in the infection of cells with some representatives of coxsackieviruses of group B [

33]. Previously, comparable data were obtained for CVB5 (LEV14) and CVB6 (LEV15) on the HEK293T cell line with CXADR knockout [

34].

The inactivation of the

ICAM1 gene has been demonstrated to significantly reduce the replication of CVA21 (LEV28), a finding that is consistent with the existing literature [

15]. We can also note that a slight effect is observed for PV1 (Sabin), CVB5 (LEV14), CVB6 (LEV15) and E6 (LEV22).

Knockout of the

SCARB2 gene suppressed reproduction of only СVA7 (Parker) reproduction, which is consistent with previously published data [

9]. Nevertheless, it is evident that a slight impact is observed in the reproduction of PV1 (Sabin), CVA21 (LEV28), E11 (LEV25), and E30 (LEV23).

The knockout of ITGA2 did not result in a reduction in reproduction in any of the strains under study, which is also consistent with the findings of previous research.

The inactivation of the

CD55 gene had a negative effect on the reproduction of numerous enteroviruses, albeit to varying degrees. The replication of CVB3 (Nancy) and CVB5 (LEV14) viruses was reduced by three orders of magnitude, while that of CVA7 (Parker) and CVA21 (LEV28) viruses was reduced by two and a half to three orders of magnitude, and that of E6 (LEV22), E7 (LEV21), E11 (LEV25), E12 (LEV20), E25 (LEV24), and E30 (LEV23) was reduced by four orders of magnitude. The replication of E25 (LEV24) was notably diminished, exhibiting a reduction of up to seven orders of magnitude. The broad impact of CD55 on the infection of cells by a range of enterovirus strains has been previously documented, including CVA21 [

15], CVB3 and CVB5 [

15], as well as E6 [

19], E7 [

15], E11 [

35], E12 [

36] and E30 [

37]. The observed effect of CD55 on cell infection with CVA7 or E25 strain has not been previously reported. Furthermore, our findings indicate that CD55 is not a requisite factor for the infection of cells with PV1 (Sabin), and CVB6 (LEV15).

The knockout of

FCGRT resulted in the complete cessation of reproduction of E6 (LEV22), E7 (LEV21), E11 (LEV25), E12 (LEV20), E25 (LEV24), and E30 (LEV23), while no effect was observed on the reproduction of coxsackie and polioviruses. This finding is consistent with the existing literature on the role of the neonatal Fc receptor FCGRT in the infection of cells by certain representatives of species

Enteroviruses B [

18].

3. Discussion

The resulting panel of cells serves as a convenient tool for determining the viral receptor utilized by a specific enterovirus strain for cell entry. Upon verification of the obtained cell panel, the majority of the studied enterovirus strains exhibited results that were consistent with the phylogenetic analysis conducted and with the data previously obtained by other researchers in the field.

The availability of experimental data indicating the use or non-use by viruses of this or that receptor may prove invaluable in the development of oncolytic therapy based on enteroviruses. Due to the inherent instability of the enterovirus genome and the potential for mutation accumulation, the resulting panel of viruses can be employed to generate viruses that utilize alternative receptor molecules to infect cells through a process known as bioselection. For example, evidence suggests that FCGRT may play a role in antitumor immune recognition of tumor cells at an early stage of tumor growth [

38]. Additionally, a decrease in FCGRT expression has been observed to correlate with tumor progression [

39]. Consequently, the search and creation of enteroviruses with FCGRT-independent mechanisms of penetration can be achieved using this panel.

In addition, different levels of suppression of viral reproduction in knockout cell lines may indicate the degree of dependence of a given viral strain on the corresponding receptor for cell entry. We hypothesize that the stronger the level of reproduction suppression of a viral strain in a given knockout line, the stronger the dependence of that strain on a given receptor. This feature of our panel can be used for preliminary analysis of mutant viral strains with altered receptor affinity for subsequent validation by more precise methods.

Consequently, the constructed cell panel may prove advantageous for the isolation of enteroviruses exhibiting heightened oncolytic potency. This may be achieved by identifying more appropriate viruses in accordance with the receptors utilized and by further delineating alterations in the genome that result in modifications to the cell penetration pathway. This can then be employed to generate recombinant strains with defined characteristics.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of the Enteroviruses

The full-genome nucleotide sequences of available enterovirus strains were retrieved from the GenBank database. The genomes of novel strains were sequenced using the Illumina platform. The sequences of structural proteins were obtained and used in a multiple protein sequence alignment, followed by the construction of a phylogenetic tree, which was performed using Clustal Omega [

40] on the EMBL-EBI site (

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/, accessed 21 November, 2024). Visualization of the phylogenetic tree was performed in Phylogenetic tree (newick) viewer [

41] (

http://etetoolkit.org/treeview/, accessed 21 November, 2024).

4.2. Cell Lines and Viral Strains

The human embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (RD) and HEK293T cell lines were procured from the ATCC bank. The IFNAR1-knockout HEK293T cell line was previously established [

31]. The cells were cultured in DMEM medium containing 100 μg/mL penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum in an atmosphere of 5% CO₂ at 37°C.

Sabin vaccine strain of poliovirus type 1 (PV1 (Sabin),); Echovirus type 6, LEV22 (E6 (LEV22); Echovirus type 7, strain LEV21 (E6 (LEV21); Echovirus type 11, strain LEV25 (E6 (LEV25); Echovirus type 12, strain LEV20 (E6 (LEV20); Echovirus type 25, strain LEV24 (E6 (LEV24); Echovirus type 30, strain LEV23 (E6 (LEV23); Coxsackie virus A7, strain Perker (CVA7 (Parker)), Coxsackie A21 virus, LEV28 (CVA21 (LEV28); Coxsackie B3 virus, strain Nancy (CVB3 (Nancy)), Coxsackie B5 virus, strain LEV14 (CVB5 (LEV14)), and Coxsackie B6 virus, strain LEV15 (CVB6 (LEV15) were obtained from the laboratory collection. The enteroviruses were amplified on the RD cell line. The infected cells and culture supernatant were collected within 2–3 days, after which the cells were destroyed by three cycles of freezing and purified by centrifugation at 2000×g for 10 minutes. Virus titers were determined using the standard Reed-Muench method.

4.3. The HEK293T Cell Lines with Viral Receptor Gene Knockouts

The knockout system, based on CRISPR/Cas9 technology, was employed to generate lines of HEK293T∆IFNAR1 cells with an additional knockout of genes encoding receptor proteins for enteroviruses. To this end, plasmid pCas-Guide (Origene, Rockville, MD, USA) was modified by the insertion of the gene encoding red fluorescent protein RFP as the second expressed translation frame, which was placed after the Cas9 gene via element 2A, thereby facilitating polycistronic translation. The pCasGuide-2A-RFP plasmid constructs, which express sgRNA spacers specific to enterovirus receptor gene sites, were obtained by cloning the oligonucleotides from

Table 1 as previously described [

31]. Subsequently, the cells were transfected with calcium phosphate in accordance with the previously described methodology [

42]. Cell clones were subsequently obtained as previously described [

31]. Briefly, genomic DNA of cell clones was isolated using a specialized ExtractDNA Blood & Cells kit (Evrogen, Moscow, Russia) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The presence of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of genes encoding viral receptors was confirmed by PCR with primers indicated in

Table 1, followed by Sanger sequencing.

4.4. Enterovirus RNA Purification and Genome Sequencing

Novel strains of enteroviruses were produced in the RD cell line. The harvested medium was clarified from cell debris by centrifugation at 4 °C, 2500 rpm for 15 minutes. The virus-containing supernatant was stored in 0.5 mL aliquots at –80 °C. Viral RNA was extracted using the GeneJET Viral DNA/RNA Purification Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and quantity of the RNA were evaluated through spectrophotometry and RNA gel electrophoresis. The cDNA synthesis was conducted using reverse transcriptase Mint (Evrogene, Moscow, Russia) with N6 random primers, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Enteroviruses cDNA was used to prepare sequencing library with the Nextera DNA Flex Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Size of the genomic library was analyzed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was about 500 bp. The library was sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq System using the MiSeq Reagent Micro Kit v2 (300 cycles). A draft enteroviral genomes were de novo assembled using the SPAdes assembler [

43] on the Galaxy web service [

44] with automatic k-measure size selection; other parameters were set as default.

4.5. Determination of Enterovirus Reproduction

To determine the rate of reproduction, the double-knockout cell line and the control cell line, HEK293TdIFNAR1, were infected with enteroviruses at MOI of 0.001. After three days, the medium containing the viruses was harvested, cleared by centrifugation for five minutes at 2000 g, and used to determine the titer of the virus using the Reed-Muench method. To this end, RD cells were infected with 10-fold dilutions of the collected medium, and the titer was calculated after three days.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O.S., P.M.C. and A.V.L.; methodology, A.O.S., A.V.L.; investigation, A.O.S., L.T.H., P.O.V., Y.D.G., O.N.A., P.M.C., A.V.L; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.S., D.S.K., A.V.L.; writing—review and editing, A.O.S., D.S.K., L.T.H., P.O.V., P.M.C., A.V.L.; visualization, D.S.K.; supervision, A.V.L.; project administration, P.M.C. and A.V.L.; funding acquisition, P.M.C. and D.S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported financially by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation, grant no. 075-15-2019-1660 (genetic analysis of viruses, their propagation and purification, phylogenetic analysis of the viral panel, Figure 1), the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 23-14-00370 (establishment and characterization of knockout cell lines, Figure 2 and Figure 3) and the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 22-14-00377 (design and obtaining corresponding plasmids of CRISPR/Cas9 system (Table 1)).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Jartti, M.; Flodstrom-Tullberg, M.; Hankaniemi, M.M. Enteroviruses: epidemic potential, challenges and opportunities with vaccines. J Biomed Sci 2024, 31, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikonov, O.S.; Chernykh, E.S.; Garber, M.B.; Nikonova, E.Y. Enteroviruses: Classification, Diseases They Cause, and Approaches to Development of Antiviral Drugs. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2017, 82, 1615–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alekseeva, O.N.; Hoa, L.T.; Vorobyev, P.O.; Kochetkov, D.V.; Gumennaya, Y.D.; Naberezhnaya, E.R.; Chuvashov, D.O.; Ivanov, A.V.; Chumakov, P.M.; Lipatova, A.V. Receptors and Host Factors for Enterovirus Infection: Implications for Cancer Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergelson, J.M.; Coyne, C.B. Picornavirus entry. Adv Exp Med Biol 2013, 790, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, M.K.; Seth, S.; Czeloth, N.; Qiu, Q.; Ravens, I.; Kremmer, E.; Ebel, M.; Muller, W.; Pabst, O.; Forster, R.; et al. The adhesion receptor CD155 determines the magnitude of humoral immune responses against orally ingested antigens. Eur J Immunol 2007, 37, 2214–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, Q.; Xin, N.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C. CD155, an onco-immunologic molecule in human tumors. Cancer Sci 2017, 108, 1934–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergelson, J.M.; Cunningham, J.A.; Droguett, G.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Krithivas, A.; Hong, J.S.; Horwitz, M.S.; Crowell, R.L.; Finberg, R.W. Isolation of a common receptor for Coxsackie B viruses and adenoviruses 2 and 5. Science 1997, 275, 1320–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomko, R.P.; Xu, R.; Philipson, L. HCAR and MCAR: the human and mouse cellular receptors for subgroup C adenoviruses and group B coxsackieviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997, 94, 3352–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamayoshi, S.; Iizuka, S.; Yamashita, T.; Minagawa, H.; Mizuta, K.; Okamoto, M.; Nishimura, H.; Sanjoh, K.; Katsushima, N.; Itagaki, T.; et al. Human SCARB2-dependent infection by coxsackievirus A7, A14, and A16 and enterovirus 71. J Virol 2012, 86, 5686–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Valeiras, M.; Sidransky, E.; Tayebi, N. Lysosomal integral membrane protein-2: a new player in lysosome-related pathology. Mol Genet Metab 2014, 111, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergelson, J.M.; Shepley, M.P.; Chan, B.M.; Hemler, M.E.; Finberg, R.W. Identification of the integrin VLA-2 as a receptor for echovirus 1. Science 1992, 255, 1718–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergelson, J.M.; St John, N.; Kawaguchi, S.; Chan, M.; Stubdal, H.; Modlin, J.; Finberg, R.W. Infection by echoviruses 1 and 8 depends on the alpha 2 subunit of human VLA-2. J Virol 1993, 67, 6847–6852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roivainen, M.; Piirainen, L.; Hovi, T.; Virtanen, I.; Riikonen, T.; Heino, J.; Hyypia, T. Entry of coxsackievirus A9 into host cells: specific interactions with alpha v beta 3 integrin, the vitronectin receptor. Virology 1994, 203, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.H.; Kajander, T.; Hyypia, T.; Jackson, T.; Sheppard, D.; Stanway, G. Integrin alpha v beta 6 is an RGD-dependent receptor for coxsackievirus A9. J Virol 2004, 78, 6967–6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafren, D.R.; Dorahy, D.J.; Ingham, R.A.; Burns, G.F.; Barry, R.D. Coxsackievirus A21 binds to decay-accelerating factor but requires intercellular adhesion molecule 1 for cell entry. J Virol 1997, 71, 4736–4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, C.; Bator, C.M.; Bowman, V.D.; Rieder, E.; He, Y.; Hebert, B.; Bella, J.; Baker, T.S.; Wimmer, E.; Kuhn, R.J.; et al. Interaction of coxsackievirus A21 with its cellular receptor, ICAM-1. J Virol 2001, 75, 2444–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, A.; Inoue, H.; Miyamoto, S.; Ito, S.; Soda, Y.; Tani, K. Coxsackievirus A11 is an immunostimulatory oncolytic virus that induces complete tumor regression in a human non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, G.; Liu, S.; Chen, X.; Peng, R.; Dai, L.; Qu, X.; Li, S.; Song, H.; Gao, Z.; et al. Human Neonatal Fc Receptor Is the Cellular Uncoating Receptor for Enterovirus B. Cell 2019, 177, 1553–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafren, D.R.; Bates, R.C.; Agrez, M.V.; Herd, R.L.; Burns, G.F.; Barry, R.D. Coxsackieviruses B1, B3, and B5 use decay accelerating factor as a receptor for cell attachment. J Virol 1995, 69, 3873–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, T.; Pipkin, P.A.; Clarkson, N.A.; Stone, D.M.; Minor, P.D.; Almond, J.W. Decay-accelerating factor CD55 is identified as the receptor for echovirus 7 using CELICS, a rapid immuno-focal cloning method. EMBO J 1994, 13, 5070–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeel, S.; Seitsonen, J.J.; Kajander, T.; Laurinmaki, P.; Hyypia, T.; Susi, P.; Butcher, S.J. Structural and functional analysis of coxsackievirus A9 integrin alphavbeta6 binding and uncoating. J Virol 2013, 87, 3943–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, M.; Mimouli, K.; Kyriakopoulou, Z.; Tsimpidis, M.; Tsakogiannis, D.; Markoulatos, P.; Amoutzias, G.D. Large-scale genomic analysis reveals recurrent patterns of intertypic recombination in human enteroviruses. Virology 2019, 526, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambaro, F.; Perez, A.B.; Aguera, E.; Prot, M.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Cabrerizo, M.; Simon-Loriere, E.; Fernandez-Garcia, M.D. Genomic surveillance of enterovirus associated with aseptic meningitis cases in southern Spain, 2015-2018. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 21523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyriakopoulou, Z.; Pliaka, V.; Amoutzias, G.D.; Markoulatos, P. Recombination among human non-polio enteroviruses: implications for epidemiology and evolution. Virus Genes 2015, 50, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorobyev, P.O.; Babaeva, F.E.; Panova, A.V.; Shakiba, J.; Kravchenko, S.K.; Soboleva, A.V.; Lipatova, A.V. Oncolytic Viruses in the Therapy of Lymphoproliferative Diseases. Mol Biol 2022, 56, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Shen, Y.; Liang, T. Oncolytic virotherapy: basic principles, recent advances and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donina, S.; Strele, I.; Proboka, G.; Auzinš, J.; Alberts, P.; Jonsson, B.; Venskus, D.; Muceniece, A. Adapted ECHO-7 virus Rigvir immunotherapy (oncolytic virotherapy) prolongs survival in melanoma patients after surgical excision of the tumour in a retrospective study. Melanoma Research 2015, 25, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiker, H.M.; Riaz, I.B.; Husnain, M.; Borad, M.J. Oncolytic virotherapy including Rigvir and standard therapies in malignant melanoma. Oncolytic Virother 2017, 6, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamad, A.; Soboleva, A.V.; Vorobyev, P.O.; Mahmoud, M.; Vasilenko, K.V.; Chumakov, P.M.; Lipatova, A.V. Development of a recombinant oncolytic poliovirus type 3 strain with altered cell tropism. Bulletin of RSMU 2022, 2, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podshivalova, E.S.; Semkina, A.S.; Kravchenko, D.S.; Frolova, E.I.; Chumakov, S.P. Efficient delivery of oncolytic enterovirus by carrier cell line NK-92. Mol Ther Oncolytics 2021, 21, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Lipatova, A.V.; Volskaya, M.A.; Tikhonova, O.A.; Chumakov, P.M. [The State of The Jak/Stat Pathway Affects the Sensitivity of TumorCells to Oncolytic Enteroviruses]. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2020, 54, 634–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendelsohn, C.L.; Wimmer, E.; Racaniello, V.R. Cellular receptor for poliovirus: molecular cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of a new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Cell 1989, 56, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, T.A.; Petric, M.; Weingartl, H.; Bergelson, J.M.; Opavsky, M.A.; Richardson, C.D.; Modlin, J.F.; Finberg, R.W.; Kain, K.C.; Willis, N.; et al. The coxsackie-adenovirus receptor (CAR) is used by reference strains and clinical isolates representing all six serotypes of coxsackievirus group B and by swine vesicular disease virus. Virology 2000, 271, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipatova, A.V.; Le, T.H.; Sosnovtseva, A.O.; Babaeva, F.E.; Kochetkov, D.V.; Chumakov, P.M. Relationship between cell receptors and tumor cell sensitivity to oncolytic enteroviruses. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine 2018, 166, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, S.M.; Powell, R.M.; McKee, T.; Evans, D.J.; Brown, D.; Stuart, D.I.; van der Merwe, P.A. Determination of the affinity and kinetic constants for the interaction between the human virus echovirus 11 and its cellular receptor, CD55. J Biol Chem 1998, 273, 30443–30447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, D.M.; Williams, D.T.; Kerrigan, D.; Evans, D.J.; Lea, S.M.; Bhella, D. Structural and functional insights into the interaction of echoviruses and decay-accelerating factor. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 5169–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandesande, H.; Laajala, M.; Kantoluoto, T.; Ruokolainen, V.; Lindberg, A.M.; Marjomaki, V. Early Entry Events in Echovirus 30 Infection. J Virol 2020, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudnik-Jansen, I.; Howard, K.A. FcRn expression in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic opportunities. J Control Release 2021, 337, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, D.C.; Yang, J.W.; An, H.J.; Na, J.M.; Shin, M.C.; Song, D.H. Fc Receptor Expression as a Prognostic Factor in Patients With Non-small-cell Lung Cancer. In Vivo 2022, 36, 2708–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Higgins, D.G. Clustal Omega for making accurate alignments of many protein sequences. Protein Sci 2018, 27, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Cepas, J.; Serra, F.; Bork, P. ETE 3: Reconstruction, Analysis, and Visualization of Phylogenomic Data. Mol Biol Evol 2016, 33, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyev, P.O.; Kochetkov, D.V.; Vasilenko, K.V.; Lipatova, A.V. Comparative efficiency of accessible transfection methods in model cell lines for biotechnological applications. Bulletin of Russian State Medical University 2022, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaxy, C. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2022 update. Nucleic Acids Res 2022, 50, W345–W351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).