Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

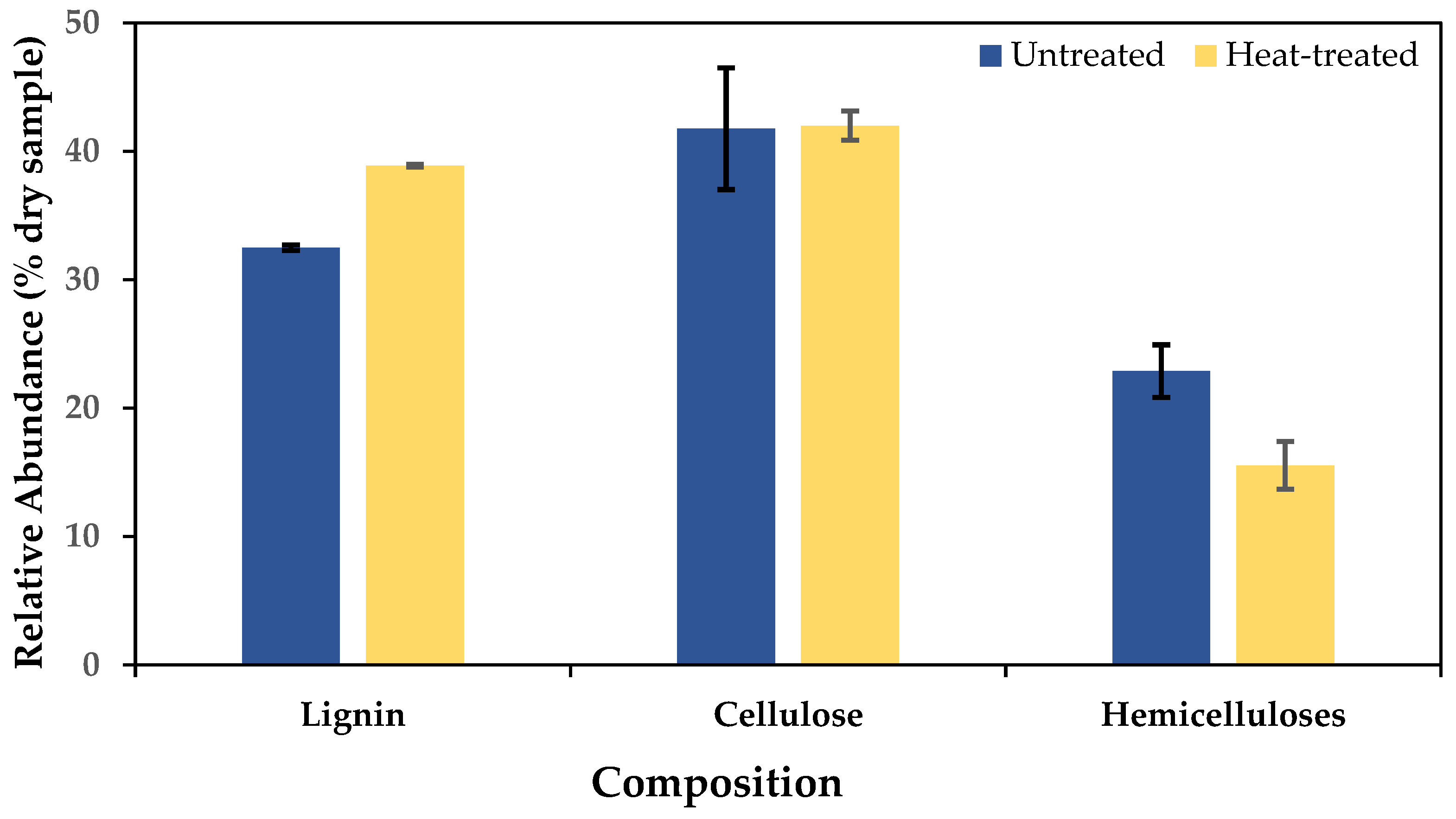

Chemical Composition

Physical and Mechanical Properties

Surface Properties

Termite Durability

3. Results and Discussion

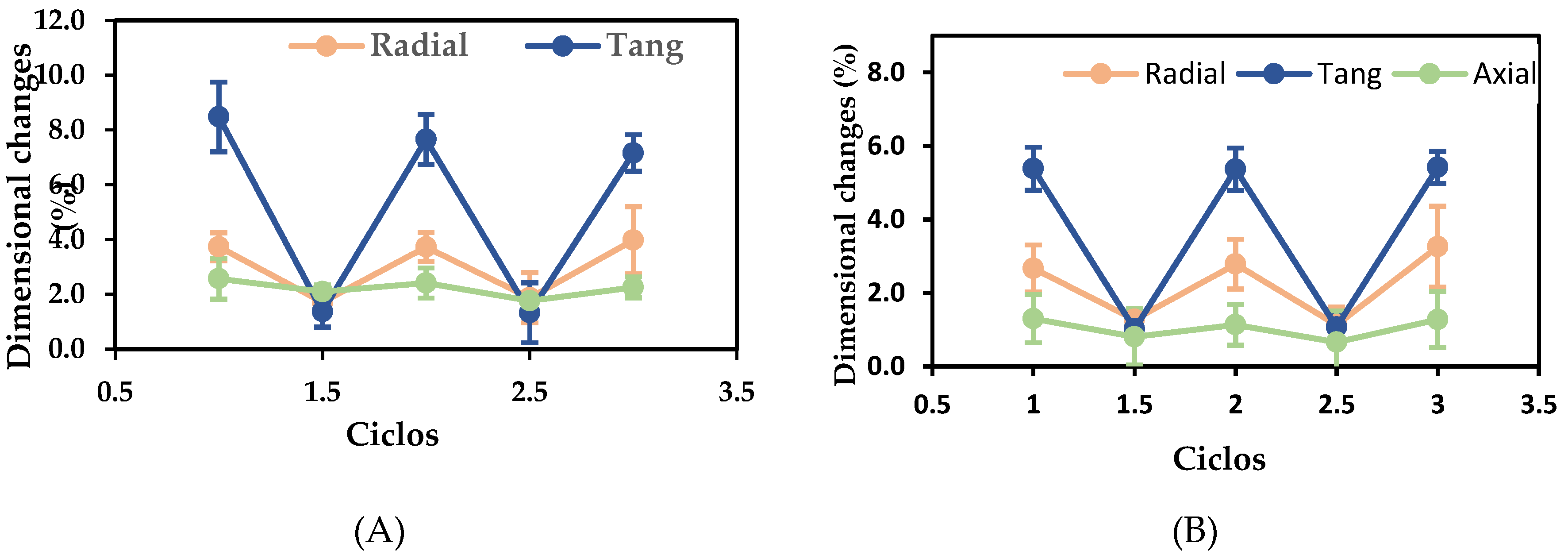

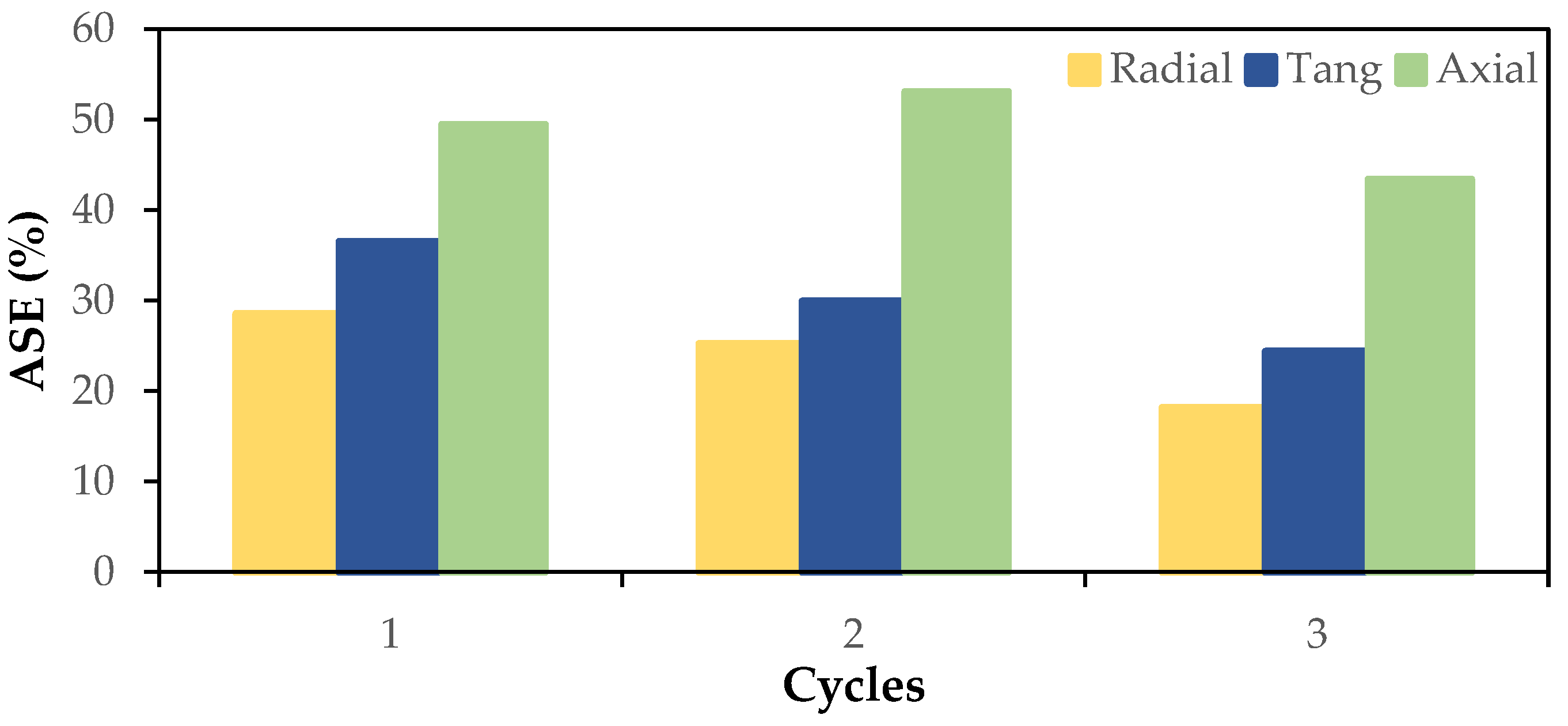

Physical and Mechanical Properties

Termite Durability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- YASUE, M.; OGIYAMA, K.; SUTO, S.; TSUKAHARA, H.; MIYAHARA, F.; OHBA, K. Geogaphical Differentiation of Natural Cryptomeria Stands Analyzed by Diterpene Hydrocarbon Constituents of Individual Trees. Journal of the Japanese Forestry Society 1987, 69, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cryptomeria Japonica (Japanese Cedar, Japanese Cryptomeria) | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox. Available online: https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/cryptomeria-japonica/ (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Pavão, D.C.; Brunner, D.; Resendes, R.; Jevšenak, J.; Borges Silva, L.; Silva, L. Climatic Drivers and Tree Growth in a Key Production Species: The Case of Cryptomeria Japonica (Thunb. Ex L.f.) D.Don in the Azores Archipelago. Dendrochronologia 2024, 85, 126204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, M. Cryptomeria Japonica: Glacial Refugia and Late-Glacial and Postglacial Migration. Ecology 1982, 63, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.H.; Faria, C.; Belerique, J.; Nobrega, C.; Penacho, L.; Rocheta, M. Resultados Preliminares Dos Testes Genéticos Com Cryptomeria Japonica Na Região Autónoma Dos Açores. 2005.

- Cheng, S.-S.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chung, M.-J.; Chang, S.-T. Chemical Composition and Antitermitic Activity against Coptotermes formosanusShiraki of Cryptomeria Japonica Leaf Essential Oil. Chemistry & Biodiversity 2012, 9, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibutani, S.; Takata, K.; Doi, S. Quantitative Comparisons of Antitermite Extractives in Heartwood from the Same Clones of Cryptomeria Japonica Planted at Two Different Sites. J Wood Sci 2007, 53, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Pereira, H. Wood Modification by Heat Treatment: A Review. BioResources 2009, 4, 370–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Şahin, S.; Ayata, U.; Domingos, I.; Ferreira, J.; Gürleyen, L. Effect of Heat Treatment on Shore-D Hardness of Some Wood Species. BioResources 2021, 16, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuopponen, M.; Vuorinen, T.; Jämsä, S.; Viitaniemi, P. Thermal Modifications in Softwood Studied by FT-IR and UV Resonance Raman Spectroscopies. Journal of Wood Chemistry and Technology 2005, 24, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjeerdsma, B.F.; Boonstra, M.; Pizzi, A.; Tekely, P.; Militz, H. Characterisation of Thermally Modified Wood: Molecular Reasons for Wood Performance Improvement. Holz als Roh-und Werkstoff 1998, 56, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, M.J.; Tjeerdsma, B. Chemical Analysis of Heat Treated Softwoods. Holz Roh Werkst 2006, 64, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjeerdsma, B.F.; Stevens, M.; Militz, H.; Van Acker, J. Effect of Process Conditions on Moisture Content and Decay Resistance of Hydro-Thermally Treated Wood. Holzforschung und Holzverwertung 2002, 54, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- TAPPI T 222 Om-02. Acid-Insoluble Lignin in Wood and Pulp. TAPPI: Atlanta, GA, USA 2002.

- Mercado, Y.; Nunes, L.; Cruz Lopes, L.P.; Esteves, B. Heat Treatment of Cryptomeria Japonica from Azores.; n.a.: Firenze, Italy, 2024; Vol. n.a., p. n.a.

- NP 619 Static bending test (in Portuguese). Inspecção Geral dos Produtos Agrícolas e Industriais (IGPAI). Lisbon, Portugal 1973.

- NP EN 310:2002-Placas de Derivados de Madeira – Determinação Do Módulo de Elasticidade Em Flexão e Da Resistência à Flexão. Instituto Português da Qualidade 2002.

- EN 118:2013 - Wood and Wood-Based Products - Determination of the Resistance to Subterranean Termites. EN 118:2013, 2013. European Committee for Standardization (CEN), Brussels, Belgium.

- Fonte, A.P.N.; Trianoski, R.; Iwakiri, S.; dos Anjos, R.A.M. Physical and Chemical Properties of Heartwood and Sapwood of Cryptomeria Japonica. Revista de Ciências Agroveterinárias 2017, 16, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yinodotlgör, N.; Kartal, S.N. Heat Modification of Wood: Chemical Properties and Resistance to Mold and Decay Fungi. Forest Products Journal 2010, 60, 357–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.; Arruda, F.; Janeiro, A.; Medeiros, J.; Baptista, J.; Madruga, J.; Lima, E. Biological Activities of Organic Extracts and Specialized Metabolites from Different Parts of Cryptomeria Japonica (Cupressaceae) – A Critical Review. Phytochemistry 2023, 206, 113520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Ferreira, H.; Viana, H.; Ferreira, J.; Domingos, I.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Jones, D.; Nunes, L. Termite Resistance, Chemical and Mechanical Characterization of Paulownia Tomentosa Wood before and after Heat Treatment. Forests 2021, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Graça, J.; Pereira, H. Extractive Composition and Summative Chemical Analysis of Thermally Treated Eucalypt Wood. Holzforschung 2008, 62, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Videira, R.; Pereira, H. Chemistry and Ecotoxicity of Heat-Treated Pine Wood Extractives. Wood Sci Technol 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.; Ayata, U.; Cruz-Lopes, L.; Brás, I.; Ferreira, J.; Domingos, I. Changes in the Content and Composition of the Extractives in Thermally Modified Tropical Hardwoods. Maderas-Cienc Tecnol 2022, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arihara, S.; Umeyama, A.; Bando, S.; Kobuke, S.; Imoto, S.; Ono, M.; Yoshikawa, K.; Amita, K.; Hashimoto, S. Termiticidal Constituents of the Black-Heart of Cryptomeria Japonica. Journal of the Japan Wood Research Society (Japan) 2004, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Alén, R.; Kotilainen, R.; Zaman, A. Thermochemical Behavior of Norway Spruce (Picea Abies) at 180–225 C. Wood Science and Technology 2002, 36, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windeisen, E.; Strobel, C.; Wegener, G. Chemical Changes during the Production of Thermo-Treated Beech Wood. Wood Sci Technol 2007, 41, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, B.M.; Domingos, I.J.; Pereira, H. Pine Wood Modification by Heat Treatment in Air. BioResources 2008, 3, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.-H.; Chang, F.-R.; Lin, C.-J.; Chang, F.-C. Effects of Temperature and Duration of Heat Treatment on the Physical, Surface, and Mechanical Properties of Japanese Cedar Wood. BioResources 2016, 11, 3947–3963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivas, K.; Pandey, K.K. Effect of Heat Treatment on Color Changes, Dimensional Stability, and Mechanical Properties of Wood. Journal of Wood Chemistry and Technology 2012, 32, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priadi, T.; Sholihah, M.; Karlinasari, L. Water Absorption and Dimensional Stability of Heat-Treated Fast-Growing Hardwoods. Journal of the Korean Wood Science and Technology 2019, 47, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, F. Changes of Water Related Properties in Radiata Pine Wood Due to Heat Treatment. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 227, 116692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsä-Kortelainen, S.; Antikainen, T.; Viitaniemi, P. The Water Absorption of Sapwood and Heartwood of Scots Pine and Norway Spruce Heat-Treated at 170 C, 190 C, 210 C and 230 C. European Journal of Wood and Wood Products 2006, 64, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, K.; Kobayashi, I.; Kuroda, N.; Harada, M.; Noshiro, S. Predicting Oven-Dry Density of Sugi (Cryptomeria Japonica) Using near Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy and Its Effect on Performance of Wood Moisture Meter. J Wood Sci 2012, 58, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubojima, Y.; Okano, T.; Ohta, M. Bending Strength and Toughness of Heat-Treated Wood. Journal of Wood Science 2000, 46, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-H.; Yun, K.-E.; Kim, J.-J. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Decay Resistance and the Bending Properties of Radiata Pine Sapwood. Material und Organismen 1998, 32, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, B.; Ayata, U.; Gurleyen, L. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Colour and Glossiness of Black Locust, Wild Pear, Linden, Alder and Willow Wood. Drewno 2019, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 117 (2012) Wood Preservatives - Determination of Toxic Values against Reticulitermes Species (European Termites) (Laboratory Method). CEN, Brussels.

| Sample | Extractives (%) | |||||||||||

| Dichloromethane | Ethanol | Water | Total | |||||||||

| Untreated | 0.60 | ± | 0.00 | 1.30 | ± | 0.43 | 0.99 | ± | 0.11 | 2.89 | ± | 0.44 |

| Heat-treated | 0.55 | ± | 0.04 | 2.05 | ± | 0.13 | 0.99 | ± | 0.24 | 3.59 | ± | 0.27 |

| Cycle | Treatment | Average | Std |

| 1st cycle | Untreated | 160.409 | 42.202 |

| Heat-treated | 130.439 | 0.0768 | |

| 2nd cycle | Untreated | 160.685 | 31.031 |

| Heat-treated | 113.143 | 22.605 | |

| 3rd cycle | Untreated | 157.167 | 20.274 |

| Heat-treated | 125.148 | 17.336 |

| Sample | MOE (MPa) | Bending strength (MPa) | ||

| Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | |

| Untreated | 7268 | 1194 | 52.6 | 2.4 |

| Heat-treated | 10836 | 771 | 42.5 | 6.0 |

| L* | a* | b* | |||

| Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. | Average | Std. Dev. |

| 67.5 | 1.2 | 13.6 | 0.5 | 24.5 | 0.4 |

| 46.6 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 4.2 | 0.2 |

| Material | Survival rate [%] | Moisture content [%] | Mass loss [%] | Attack level |

| Untreated | 40.60 | 56.89 | 8.82 | 3.8 |

| Heat-treated | 31.30 | 64.42 | 10.48 | 4.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).