1. Introduction

The ability of tumors to accumulate and retain the colloidal particles described first by H. Maeda became widely known as the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect and served as the basis for developing nanoformulations of antitumor drugs and theranostics. Indeed, this phenomenon offered a powerful tool for enhancing the selectivity of drugs by encapsulating them in the nanoparticles, thus endowing them with colloidal properties. However, in spite of numerous preclinical data demonstrating the enhanced efficacy of the nanoparticles over free agents only a few nanoformulations were approved for clinical use. These disappointing results could be due to the heterogeneous character of the EPR effect that largely relies on the abnormality of the blood vessels in the tumor and its environment and could considerably vary depending on many factors such as, for example, the type of the tumor and the stage of its development, its localization, etc.[

1,

2] In other words, not all tumors are capable of accumulating nanoparticles and therefore not all of them are suitable for treatment with nanotherapeutics. Many new trends appeared in pharmaceutical nanotechnology in response to these findings starting from optimization of the nanocarriers for better tumor targeting to the use of duet theranostic systems for personalized selection of cancer patients who could benefit by using nanotherapeutics.[

3,

4]

Indeed, our previous intravital microscopy (IVM) study of the fluorescently labeled diagnostic hybrid supermagnetic iron oxide-based nanoparticles (hMNP) and therapeutic doxorubicin-loaded poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles (PLGA NP) (theranostic pair) revealed their considerable and simultaneous accumulation in the 4T1 murine mammary carcinoma. Despite the similarity of their sizes (~100 nm) and negative zeta potentials, the physicochemical properties of the hMNP and PLGA NP were still diverse, i.e. hMNP are apparently more hydrophilic than PLGA NP; however, the areas of their accumulation in the tumor almost overlapped.

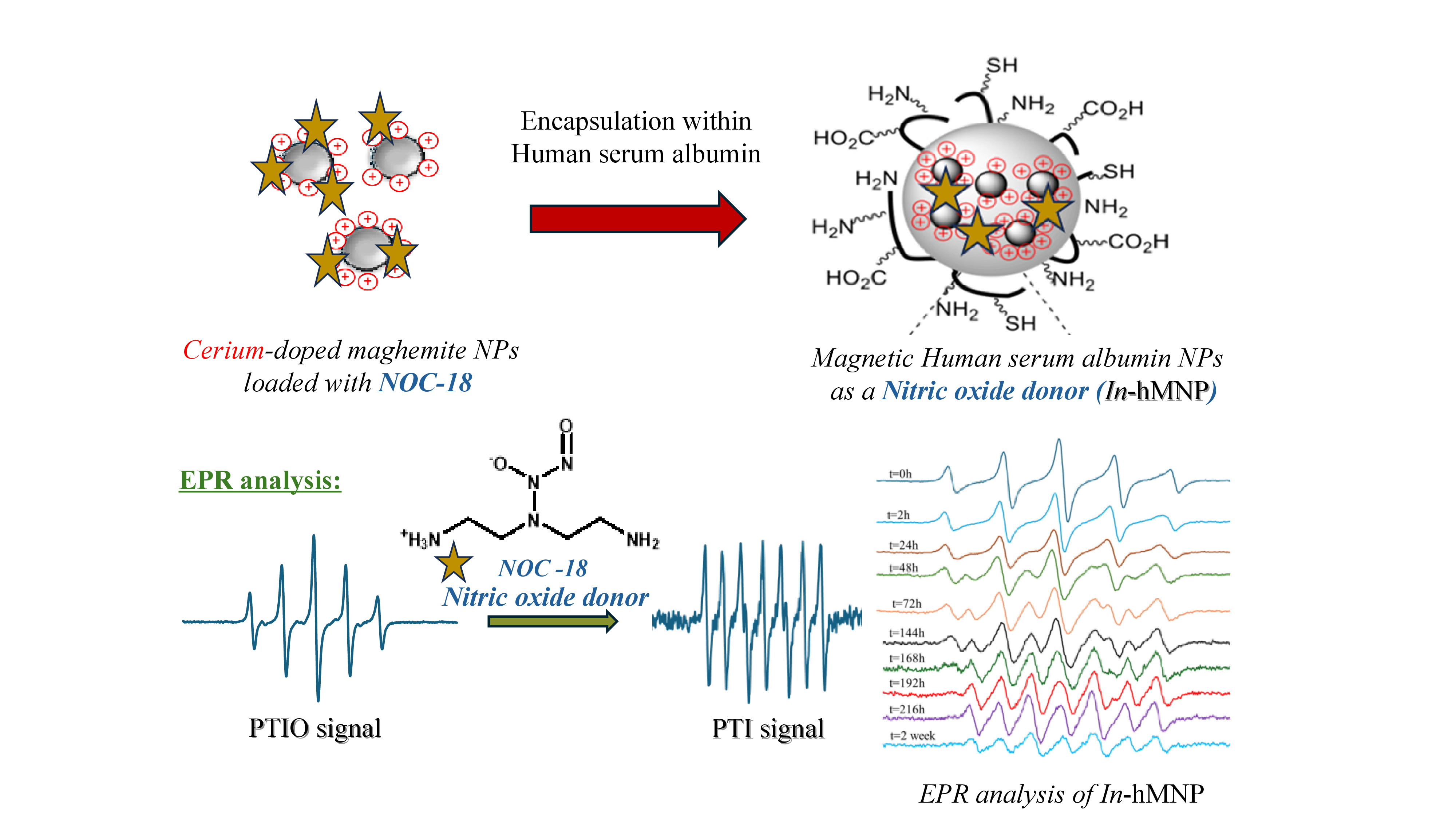

The hMNP used in this study is a novel supermagnetic MRI contrasting agent comprising the hybrid Ce3/4+-doped maghemite nanoparticles encapsulated within the biocompatible human serum albumin (HSA) matrix. Due to the enhanced magnetic properties of the hMNP, the dose required for reliable tumor MRI could be reduced as compared to conventional iron oxide-based contrasting agents. Altogether these results suggest that the hMNP could serve as a potentially suitable and safe diagnostic companion that could help to reveal the tumors potentially responsive to nanotherapeutics.

These important findings inspired us to further improve this approach. Indeed, while most strategies are aimed to improve tumor targeting via optimization of the nanocarriers, there is one remarkable strategy using a totally different approach involving the enhancement of a tumor response via modulation of its characteristics. Thus, it was shown that the EPR effect might be enhanced by administration of specific agents releasing nitric oxide (NO). This phenomenon was first shown for topical nitroglycerin, which releases nitrite. Nitrite is converted to NO more selectively in the tumor tissues, which leads to a significantly increased EPR effect and enhances antitumor drug effects as well[

5,

6]. The mechanism is related to the activation of matrix metalloproteinases that cause disintegration and remodeling of the extracellular matrix, in addition to facilitating vascular permeability via degradation of matrix proteins as a result of collagenolytic action. This approach proved to be useful for macromolecular drugs and pro-drugs

i.e. the increase of the tumor vessel permeability is sufficient to enable the increased tumor uptake of the macromolecules. However, its usefulness for nanoparticle-based delivery has been addressed only marginally so far.

Therefore, the objective of the present study was to develop the method for endowing the hMNP with the NO donor function. Administration of such a dual-function agent prior to the therapeutic nanoparticles could potentially facilitate their access to the tumor.

The well-known NO-releasing compound NOC-18 (2,2ʹ-(hydroxynitrosohydrazino)bis-ethanamine, DETA NONOate) was chosen as a model nitric oxide donor due to its enhanced NO release time (NOC-18, t½ = 20 h; PBS, pH 7.4, 37 °C)[

7,

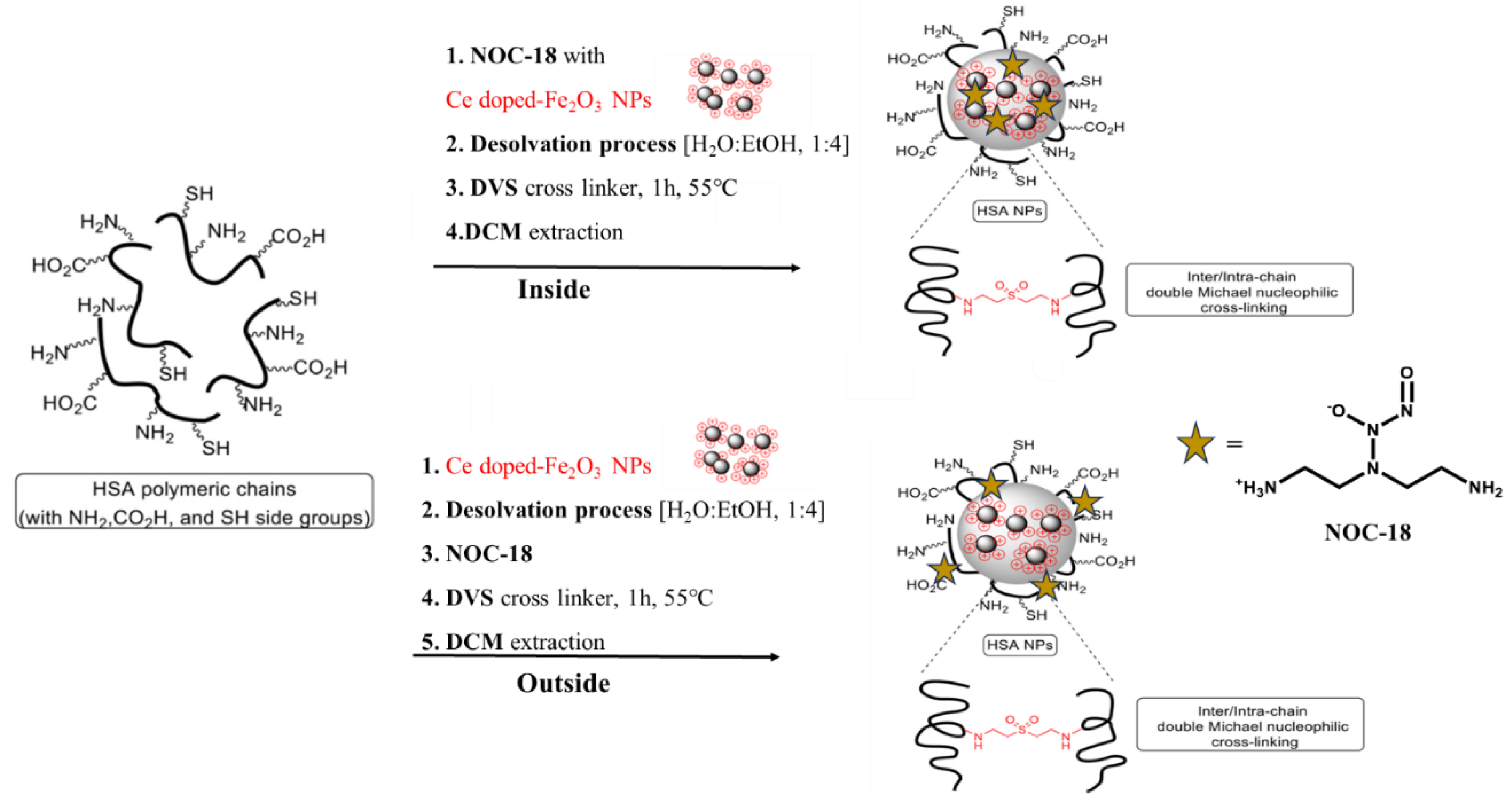

8]. NOC-18 was bonded to hMNP using both an interior and exterior bond as illustrated in

Figure 1. In the

interior bond approach, NOC-18 was bonded coordinatively to the CM NPs before being encapsulated within HSA (

In-hMNP), while in the

exterior bond approach, NOC-18 was bonded covalently to the HSA surface after forming the HSA NPs (

Out-hMNP).

In our extensive investigation of these nanoparticles, we utilized the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) measurements and the Griess assay to meticulously monitor NO release. We monitored the final nanocarriers, as well as their condition during the fabrication steps. Several steps in the original procedure[

4] were identified as degrading NOC-18 and accelerating NO release. Consequently, we have optimized the purification process using dichloromethane (DCM) extraction to prevent the NO release. This process of optimization and purification is crucial for increasing the effectiveness of NOC-18 in targeting tumors by protecting them from external elements. We demonstrate that the resultant

In-hMNP nanoformulation stabilizes the attached NOC-18 and significantly prolongs its half-life compared to the NOC-18 in solution and

Out-hMNP.

3. Results and Discussion

As mentioned above, in our previous study[

4], we synthesized the hybrid magnetic nanoparticles (hMNP) and successfully demonstrated their tumor-targeting capabilities. Building on this foundation, our current research aims to engineer nanoparticles capable of co-delivering nitric oxide (NO) to induce vasodilation in tumor cells and prolong NO half-life. This approach is designed to increase the concentration of NPs in the tumor, thereby improving treatment outcomes.

Before bonding the NO donor to the nanoparticles, one must investigate the sensitivity of the NO donor to various preparation steps to ensure its stability and prolonged release. The previous nanoparticles (NPs) were prepared using the following steps: dissolution, desolvation, heating (1h, 55 °C), purification (using a Vivaspin centrifugal 100 kDa filter, 20 min*3), and an optional step of lyophilization (with sucrose as a lyoprotectant). Some of these steps may potentially accelerate NO release or cause NOC-18 degradation. The first such step is heating, which is essential for cross-linking using DVS. Initially, the HSA-embedded CAN-maghemite NPs were prepared using DVS at room temperature. However, after washing, the DLS measurements revealed an additional free HSA protein peak at 4 nm, indicating that the particles were partially disassembled in the aqueous solution. This suggests that the DVS did not bind as intended, leading to the release of free protein alongside the remaining particles. Reducing the heating time to 30 min led to the formation of bigger nanoparticles with sizes of 233 ± 30.4 nm and a high PDI of 0.36. Thus, the temperature of the reaction is critical for effective cross-linking with DVS. Although there is some loss of NO during this process, still, a small amount is still necessary for its intended activity.

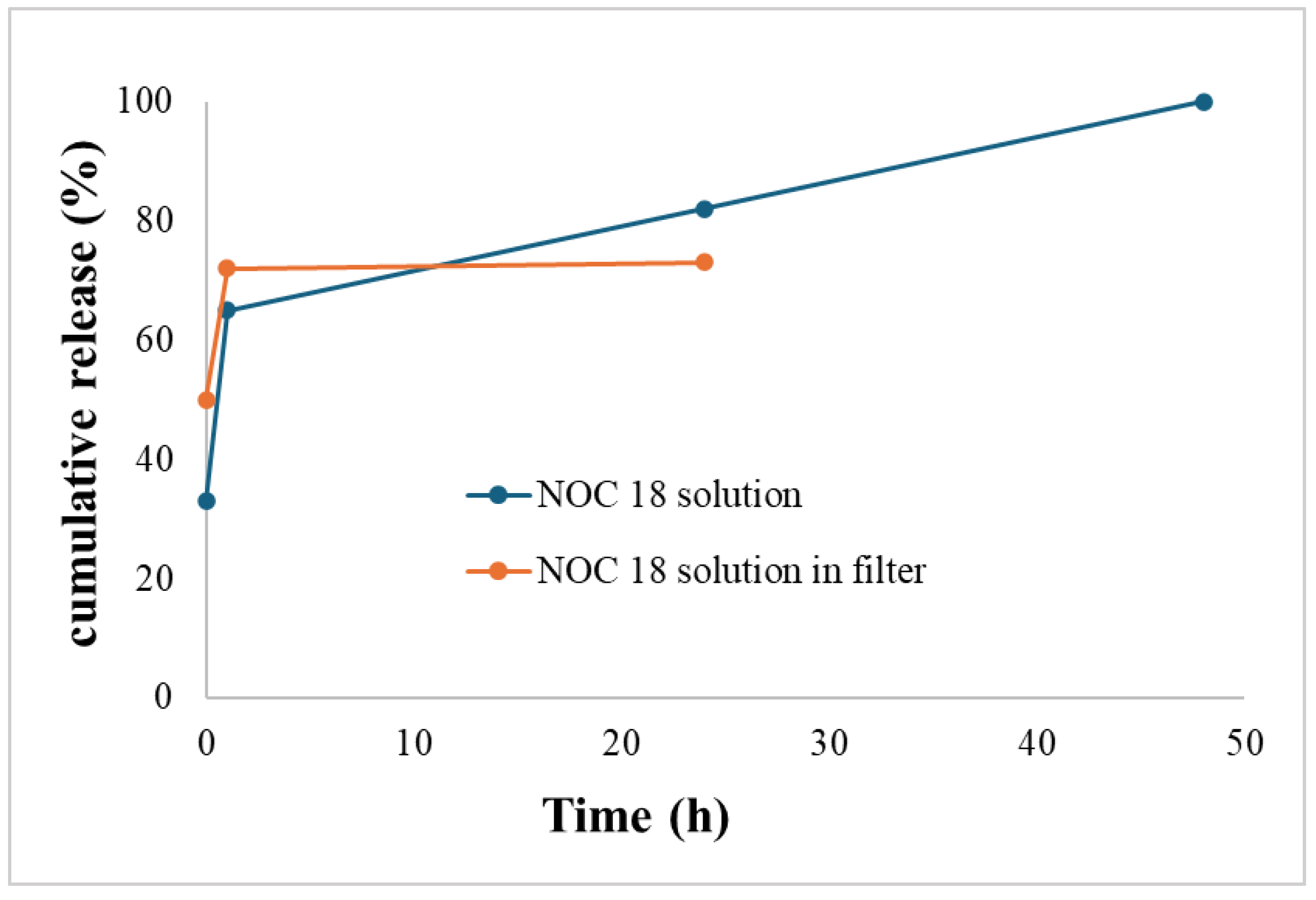

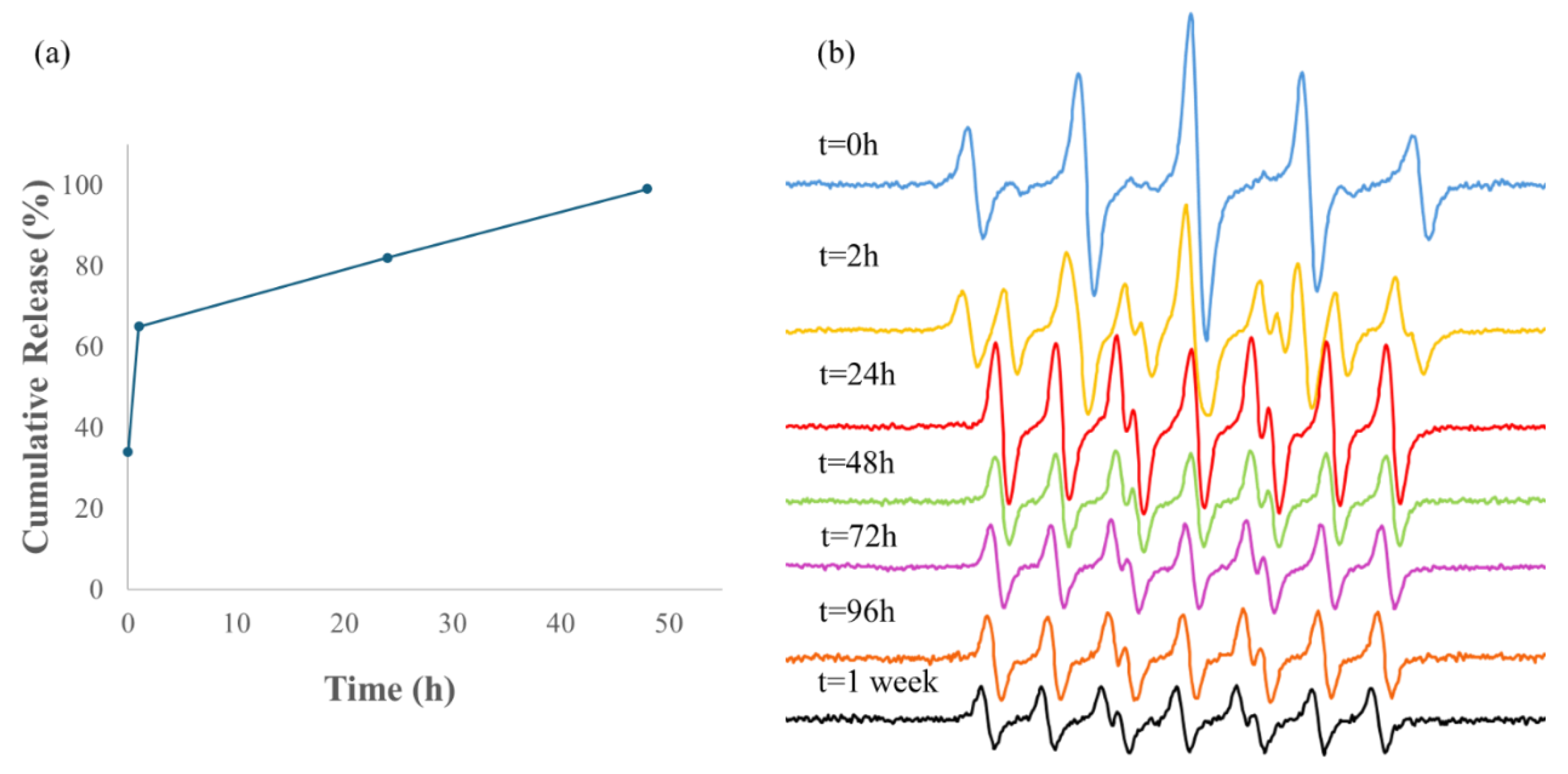

Second, there is also a need to verify the impact of the Vivaspin centrifugal filter device on the stability of the NO donor. Therefore, we conducted an essential experiment, in which a solution of NOC-18 (matching the concentration that will be used in the reaction), was subjected to purification using the Vivaspin centrifugal filter tubes (2 min*3). The solution that passed through the filter was tested using the Griess assay. The results, illustrated in

Figure 2, demonstrated that NOC-18 passing the filter achieved 50% release immediately at t = 0 h, after only 6 min of centrifugation, which is substantially shorter compared to the 60 min typically required for washing hMNP. In contrast, the NOC-18 solution required approximately 30 min to achieve the same level of release. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the NOC-18 within the filter did not reach 100% release, which is probably due to the loss of the NO within the cellulose filter, as will be explained below.

Consequently, and before delving into the chemical explanation, we examined the third step to assess sucrose's impact on the stability of NOC. According to the Griess assay, simple mixing of NOC-18 and sucrose resulted in an 85% release at t = 0 h, indicating an unexpectedly rapid release (data not shown). This observation suggests that the cellulose filter or sucrose may accelerate the release of NO from NOC-18 and may also interact with or degrade the NO donor.[

13,

14] However, we cannot monitor this release during these steps because the entire NO amount has already been released.

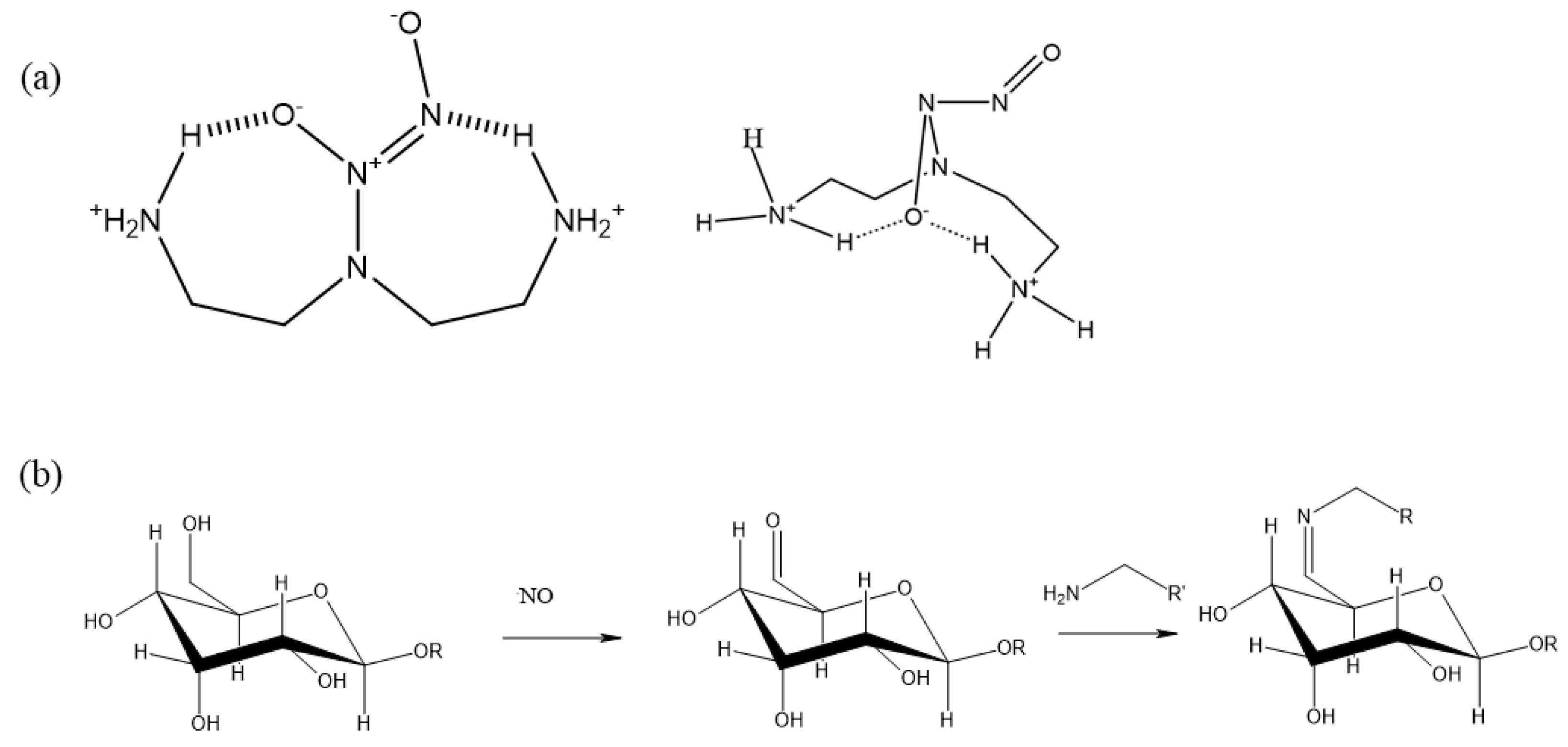

A possible explanation for this phenomenon is interference with the internal hydrogen bonds within the NOC-18 molecule. NOC-18 is a triamine molecule with pKa values ranging from ~9 to 11.[

15] In physiological conditions, most of the molecules are double charged, which means the N-oxide group in NOC-18 can be stabilized by two hydrogen bonds with the ammonium salt hydrogens (

Figure 3). Without these hydrogen bonds, the release of NO is faster. [

16]

Sucrose contains primary hydroxyl groups, which can be radical and can be oxidized to aldehyde groups[

17]. Aldehydes are known to react spontaneously and very fast with primary amine groups. The NOC-18 molecule has two primary amine groups that may produce a Schiff base upon interaction with aldehydes of oxidized sucrose. Therefore, these primary amines are no longer hydrogen bond donors, leading to a higher overall effect on disrupting the internal hydrogen bonds in NOC-18.

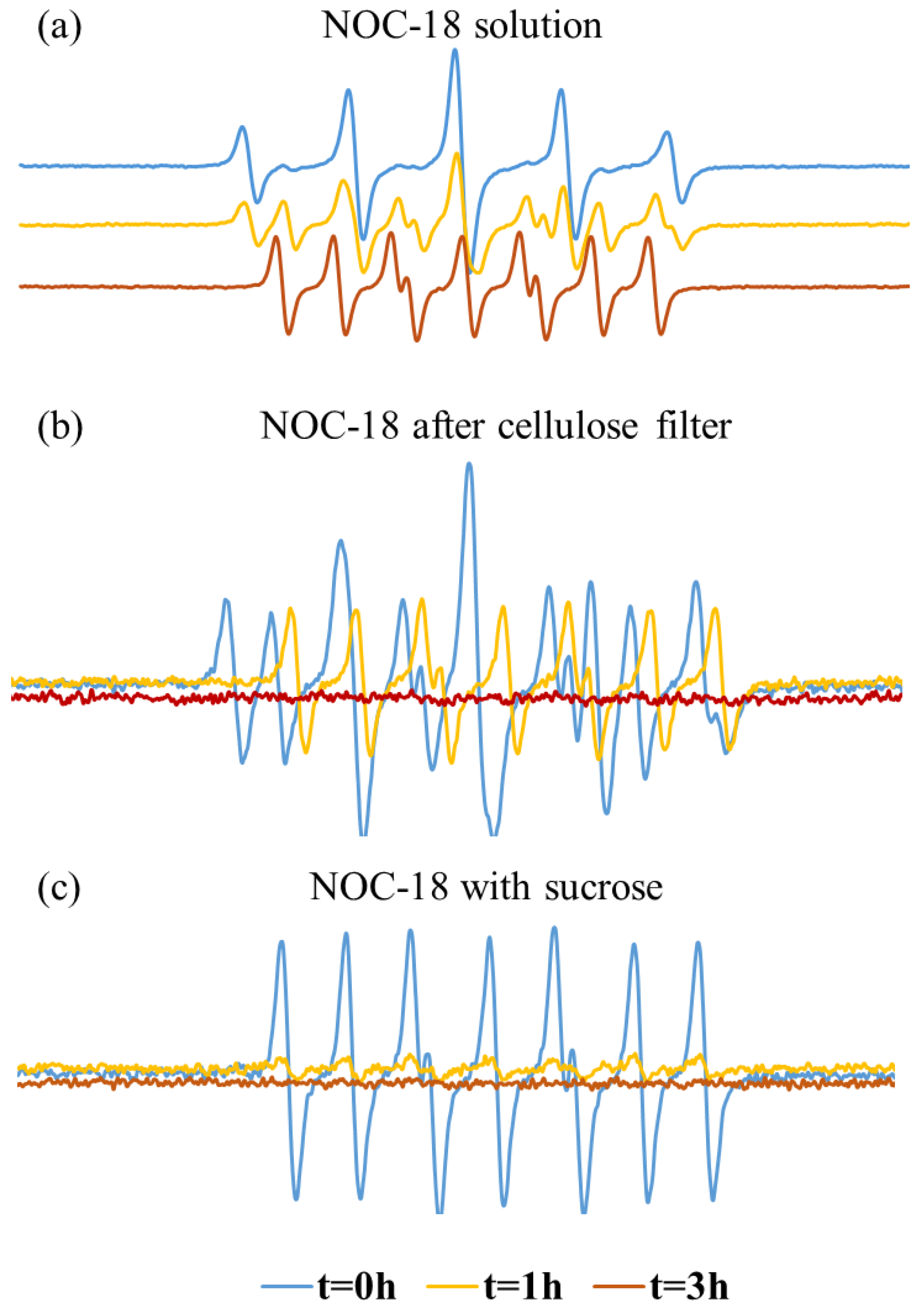

The EPR was also used to follow up on NO-releasing.

Figure 4a shows the EPR of the NOC-18 solution with radical trap (PTIO) initially at t = 0, where there is mainly a PTIO signal. Over time the PTI signal increased and stayed stable up to after 3 h. However, when using a cellulose filter there is a mixed signal of both PTIO and PTI at t = 0 (

Figure 4b), indicating nitric oxide (NO) instant release already at t = 0. After 1 h, the PTI signal becomes clearly visible (with 7 distinct peaks), while the PTIO signal significantly weakens. After 3 h, both signals faded. The presence of the PTI signal at t = 0 suggests that the filtration process likely accelerates NOC-18 degradation. The decline of the PTI signal at t = 3 is likely due to the release of a reductant into the solution, which reduces PTI to its hydroxylamine form, an EPR-silent species, thus causing the PTI signal to diminish (

Figure 4b). When sucrose is mixed with NOC-18 solution, at t = 0 there are mainly PTI signals (

Figure 4c); however, after 1 h the signal is declined (

Figure 4c). We suspect that also here sucrose enhanced NOC-18 degradation leading to a reduction of PTIO and PTI to their EPR silent signal by degraded products. The faster degradation of NOC-18 when mixed with sucrose, compared to its slower release using a cellulose filter, is due to immediate and uniform contact in solution, while the filter limits interaction, resulting in a more gradual release.

These results emphasize the need to optimize the purification process to ensure its compatibility with the intended therapeutic application. Addressing these concerns is essential for preserving the integrity and functionality of the nanoparticles and their associated therapeutic payloads, thereby enhancing the overall success of the delivery system. Following these findings, we decided to purify the NPs and to wash out the unbound DVS by extraction with dichloromethane (DCM). To confirm that the unbound DVS was thoroughly washed away with the DCM we performed GC-MS (7890B gas chromatograph/5977B mass detector (Agilent) equipped with a RXI-624 SIL-ms Fused Silica Capillary Column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 1.4 μm film thickness, Restek 13868)) analysis, ensuring there was no free DVS or only a negligible amount in the suspension. Additionally, we exclude the option that DCM influences NO release from NOC-18 before the fabrication of the hMNP inside and outside NPs. (

Figure 3a,b). As shown in

Figure 5a,b, the NOC-18 purified with DCM did not exhibit any changes compared to the NOC-18 solution, it behaved similarly to the NOC-18 solution in both the Greiss assay and EPR measurement, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4c, respectively. Hence, considering the above results, we found that the optimal purifying process is via extraction.

Binding NOC-18 to hMNP offers significant advantages. The NPs enable targeted NO delivery through the EPR effect and allow for further surface engineering to achieve specific tumor targeting. This strategy enhances therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects.[

2,

18] Additionally, the prolonged circulation time of nanoparticles[

19,

20] ensures sustained NO release, extending the therapeutic window compared to free NOC-18. [

21]

,[

22]

Several strategies were explored to bind NOC-18 to hMNP and identified two promising approaches:

1. Final Step Addition Strategy: In this strategy, NOC-18 is added during the final step of NPs fabrication. This approach minimizes NO release and utilizes the presence of DVS in the final step to covalently bind NOC-18 to the hMNP surface. This type of particle is referred to as "Out-hMNP."

2. Cerium Coordination Strategy: Here, NOC-18 is first coordinated with the CM NPs due to cerium's strong affinity for amine. Subsequently, the NOC-18-loaded CM NPs are encapsulated within the HSA matrix. This encapsulation not only protects NOC-18 from external conditions but also potentially prolongs its half-life, thereby improving the prolonged release of NO. This type of particle is referred to as "In-hMNP"

Both

Out-hMNP and

In-hMNP were characterized by DLS, surface zeta potentials, TEM, Griess assay, and EPR analysis. In contrast to the positively charged CM NPs (+40–50 mV), the

In &

Out-hMNP had negative charges in the range of −(36-44) mV (

Table 1), which is due to the negative HSA charge (isoelectric point at physiological pH is ~5). The hydrodynamic diameters of both hMNP types were found to be 139 nm for the

In-hMNP-and 114 nm for the

Out-hMNP with PDI values below 0.2, indicating their narrow size distribution (

Table 1). The difference in hydrodynamic diameters between

In-hMNP and

Out-hMNP can be attributed to the distinct loading processes of NOC-18. In the

In-hMNP, NOC-18 binds to the coordination sites on the CM NPs, which reduces the number of available sites for HSA binding. This decreased interaction allows for a less tightly packed encapsulation, resulting in larger particle sizes. In contrast, for the

Out-hMNP, NOC-18 is added at the final step and is attached covalently to the surface of the pre-formed HSA NPs; since the NOC-18 does not contribute much to the overall size of the nanoparticles, they have a similar hydrodynamic diameter as the non-loaded hMNPs.

The stability of both types of nanoparticles under simulated biological conditions was assessed upon their incubation in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and serum-free RPMI cell medium. Following incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, both nanoparticles initial size and polydispersity index maintained their stability in both mediums, reaffirming their suitability for biological applications.

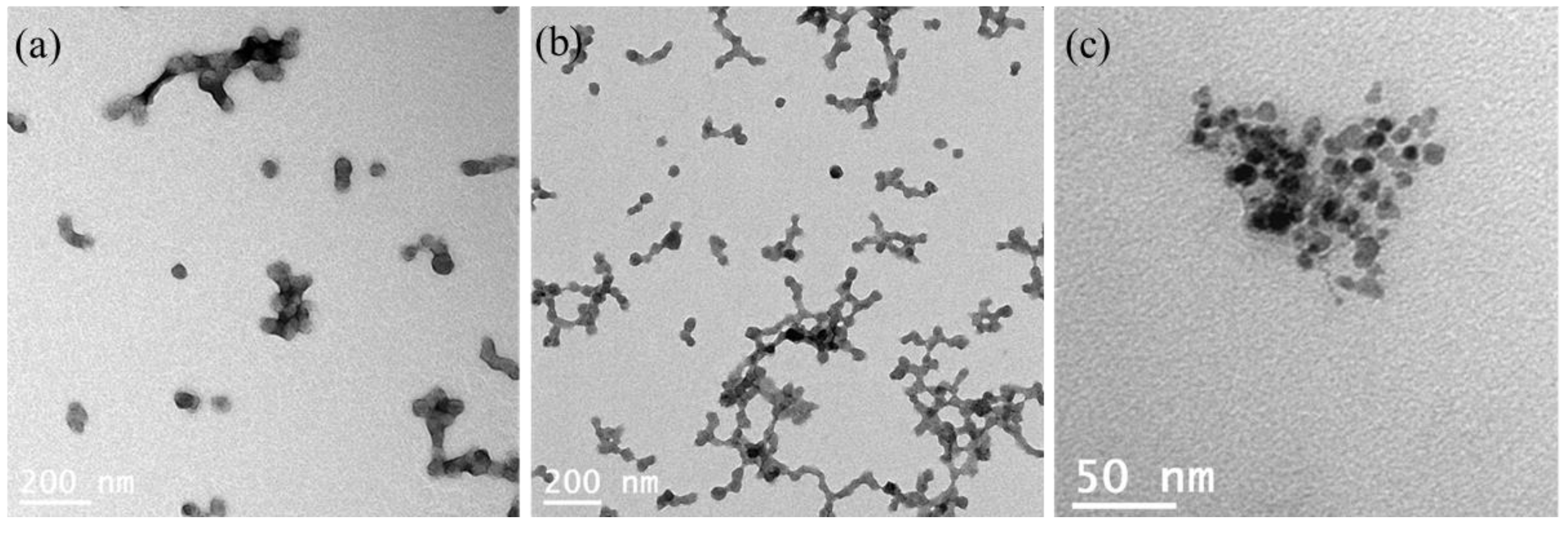

As shown by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the

In &

Out-hMNP were spherical and practically monodispersed with a size range of 35–50 nm (

Figure 6a,b). This size range is smaller compared to their size in DLS, which was measured to be >100 nm (

Table 1). The DLS measures the hydrodynamic diameter that includes the electric dipole layer adheres/solvent adsorption onto the NPs surface, and therefore the NPs size is larger. Additionally, the presence of some aggregates within the sample could potentially distort the light scattering intensity towards larger size values during DLS analysis.[

23] However, when defining DLS by “number”, the average size was 60-80 nm which is much closer to the TEM results.[

24]

Figure 6c presents aggregated hMNP. This image was obtained without uranyl acetate staining (grid preparation step); therefore, the CM NPs appear more contrasted whereas the organic phase is blurred. It is worth noting that the size of the cerium oxide NPs (CM NPs) encapsulated within the HSA matrix was found to be approximately 8 nm. This result underscores the effectiveness of the encapsulation process in confining the size of the nanoparticles within the HSA matrix.

The NO release quantification from both composites and compared to the free NOC18 molecule was determined using a standard Griess reagent kit (G-7921, Molecular Probes). The Griess assay allows an indirect measurement of NO by quantifying nitrite at specified time intervals. It is crucial to highlight that the tested NO maintains an equivalent concentration to that present during the reaction, having undergone identical reaction conditions. The reference point, denoted as t = 0 h, occurs immediately after the end of the reaction and after 30 min of incubation with the Griess reagent.

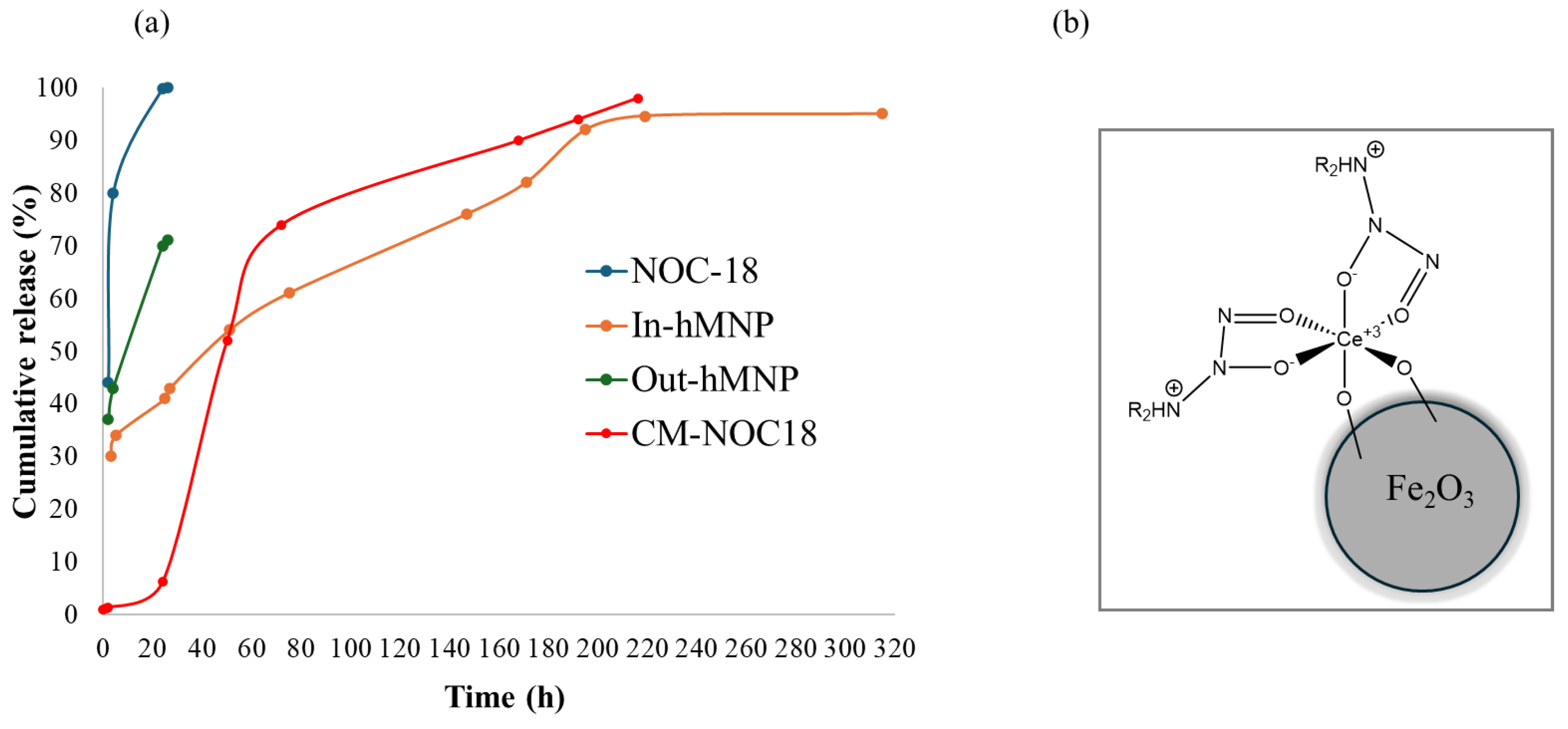

As depicted in

Figure 7 (blue curve), the unbound NOC-18 demonstrated a burst release of NO (approximately 50%) within the initial 30 min. Approximately 80% of NO was released within 2 h, followed by nearly 100% release within 22 h. This behavior aligns with the findings reported by Meller et al.[

25] The NO release from

Out-hMNP exhibited a first-order kinetic profile, with a half-life of approximately 2 h; over 70% of NO was released by 22 h (gray curve). Notably, relative to the theoretical concentration of NOC-18 the

Out-hMNPs did not achieve complete NO release. This incomplete release may be due to the interaction of NO with the functional groups of HSA, particularly with the thiol groups.[

26] The evidence for this hypothesis will be presented in the next section using EPR analysis.

Interestingly, the

In-hMNP remarkably prolonged the NO release profile. Based on the Griess assay (

Figure 7, orange curve), only after 50 h, over 50% of NO was released. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that NO was released from the

In-hMNP sustainably over 10 days without any burst release.

To prove that this prolonged release is due to the CM NPs, we conducted another experiment using CM particles with an NOC-18 solution. The results showed that the CM NPs released 50% of their NOC-18 content after 50 h (

Figure 7, red curve), like the release profile of the

In-hMNP. This indicates that the strong binding between NOC-18 and CM particles extends the release time of the first NO equivalent by restricting spontaneous degradation of the NONOate group, resulting in prolonged release and protection from external conditions. Overall, the strategy of integrating NOC-18 into the CM NPs matrix is crucial for modulating NO release kinetics and optimizing its therapeutic performance.

As shown in

Figure 7,

In-hMNP and CM-NOC18, it is evident that there are two distinct increases in the measured release. The primary release phase, occurring around t = 50 h, may occur from NO that is less strongly bound, whereas in than the secondary release phase at 160h.

One could assume that since each NOC-18 molecule releases two molecules on NO, the molecule is released at 50h, and the 2

nd one is released at 160h. However, it is known[

27] that one molecule of NOC-18 decomposes to release two molecules of NO simultaneously or nearly so. Thus, it seems that the first release refers to NOC-18 attached to more exposed sites on the surface of the particle such as carboxyl and hydroxyl groups. In these regions, NO may be released relatively quickly due to weaker chemical bonds or easier access to the surface.

The secondary release, around t = 160 h, is associated with NOC-18 which is more strongly bound, particularly with cerium. Cerium can form strong coordinate bonds with NO [

28], which makes rapid release more difficult and requires a longer time. In contrast, the bonding of NOC-18 to the matrix in

Out-hMNP may not be strong enough to slow the release, leading to a rapid, less prolonged release profile without a distinct secondary phase, as seen with the NOC-18 molecule.

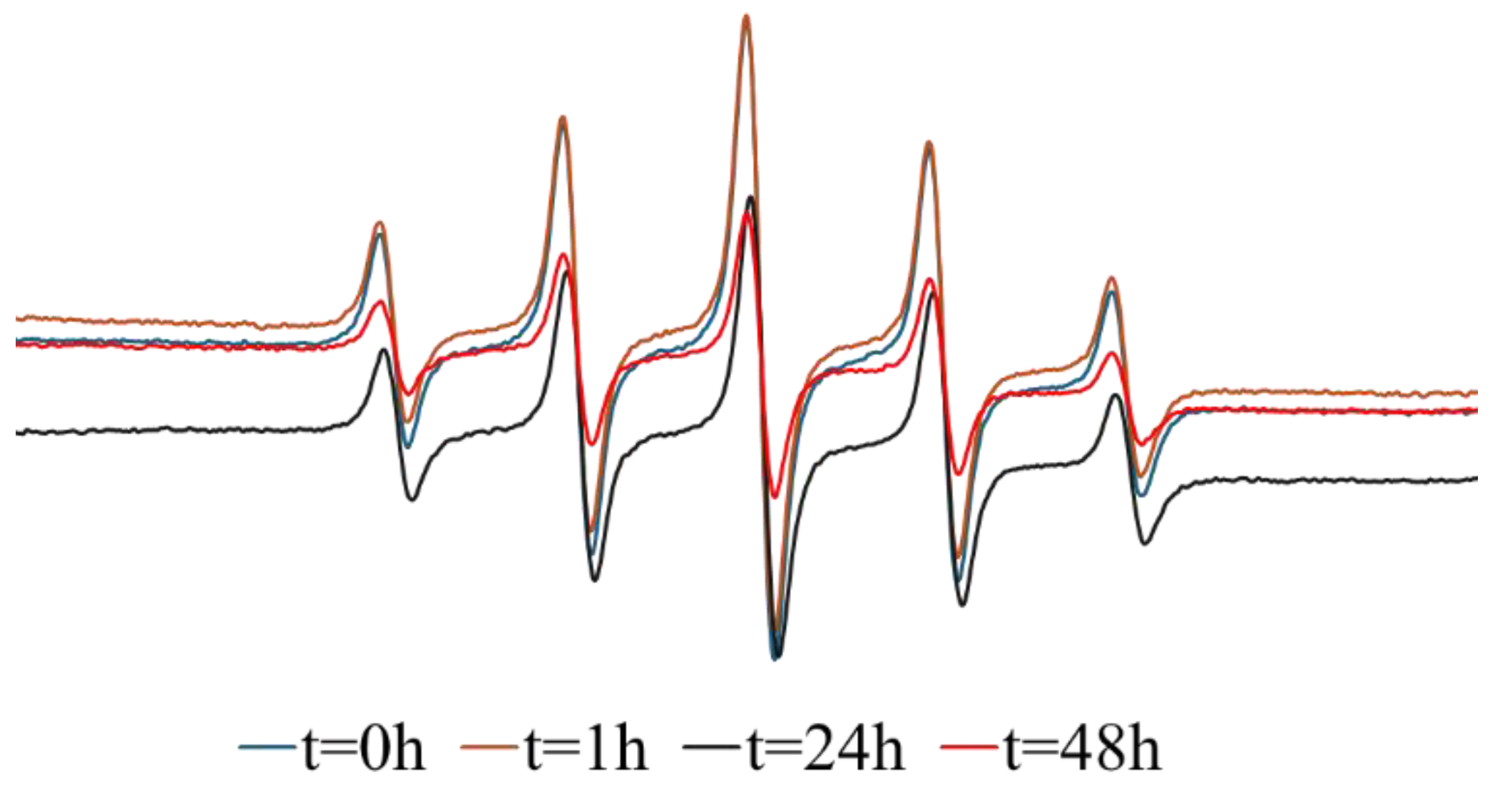

Next, the NO release was investigated by EPR spectroscopy to support the Griess results. The EPR measurement for both types of composites

Out &

In-hMNP are shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 10, respectively. For the

Out-hMNP (

Figure 8), there were no observable changes in the spectrum over time, and only the PTIO signal is present. The distinction between the Griess Assay and EPR, aside from the lower sensitivity of the latter, is that in EPR measurements, PTIO traps the NO radicals released during the measurement, while the Griess assay captures all the NO that was released before and during the measurement and has already been converted to nitrite. Based on that, the absence of a PTI signal does not necessarily imply a lack of NO release, but rather that it may have been released before the EPR measurement and/or that NO release could be occurring at very low concentrations during the measurement. The question arises is why? Especially since the addition of the NOC18 was at the final fabrication step. The EPR measurement supports the explanation provided earlier in

Figure 7, suggesting that

Out-hMNP may react with or degrade by the functional groups of HSA, particularly thiols. Consequently, the absence of the PTI signal can be attributed to these interactions, as the majority of NOC18 may have undergone degradation or reacted with HSA, thereby hindering the detection of PTI.

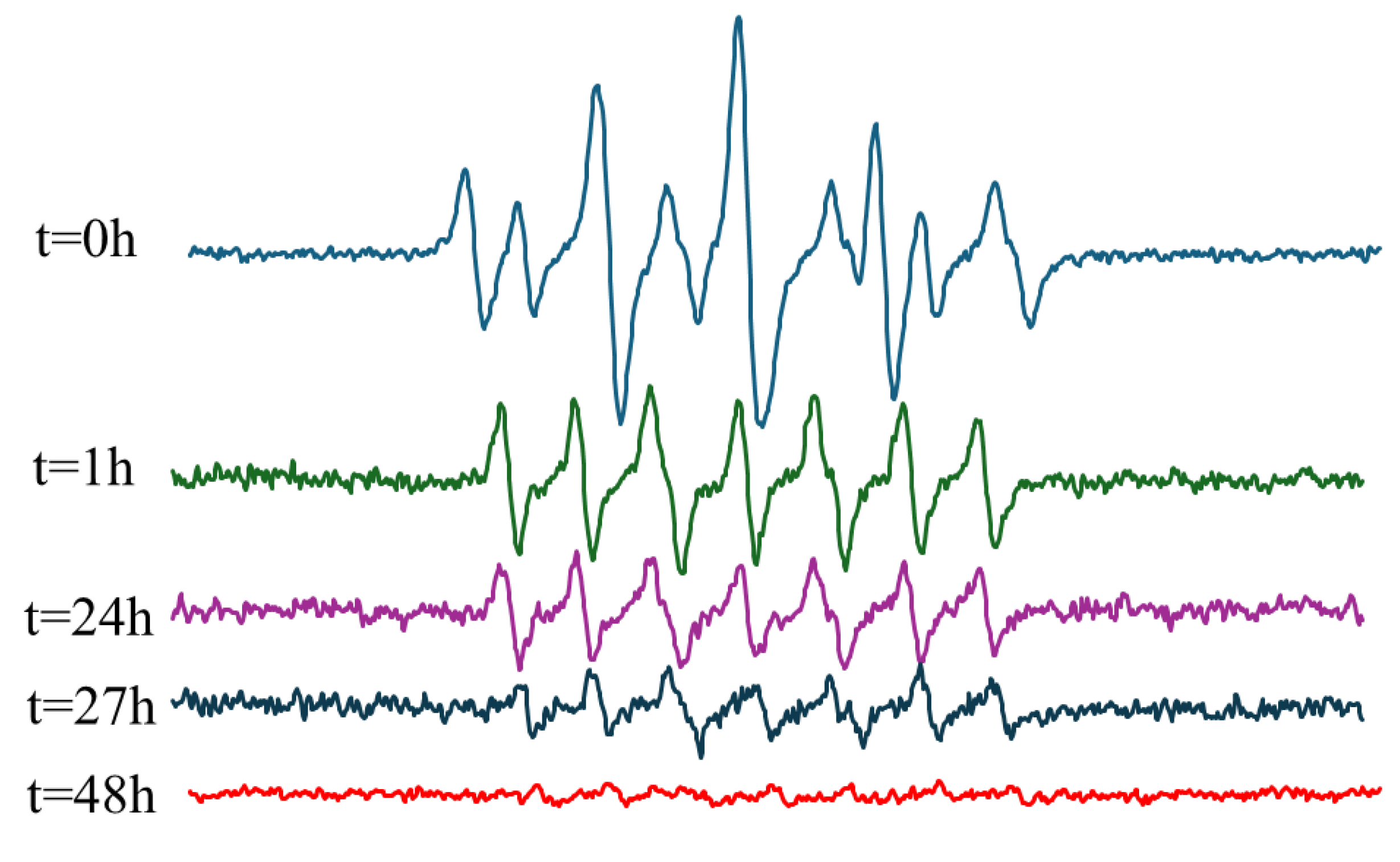

To further validate our hypothesis, we mixed the HSA NPs with NOC18 and conducted another EPR measurement (

Figure 9). Compared to the NOC18 solution (

Figure 4a), where NO release is detected only after 1 h, the simple mixing of the HSA NPs with NOC18 caused the release of NO already at t = 0 h, as indicated by a mixed signal of PTI and PTIO. This result supports our hypothesis that the interaction between HSA NPs and NOC18 causes an initial release of NO. The rapid NO release is likely due to the HSA protein, especially its thiol groups.[

29] Although a clear PTI signal is observed at 1 h and even at 24 h, no PTI signal was detected in the EPR spectrum of

Out-hMNPs. This can be explained by the 1-h heating step during the cross-linking process, which accelerates NO release, along with the interaction with HSA that initiates the NO release.

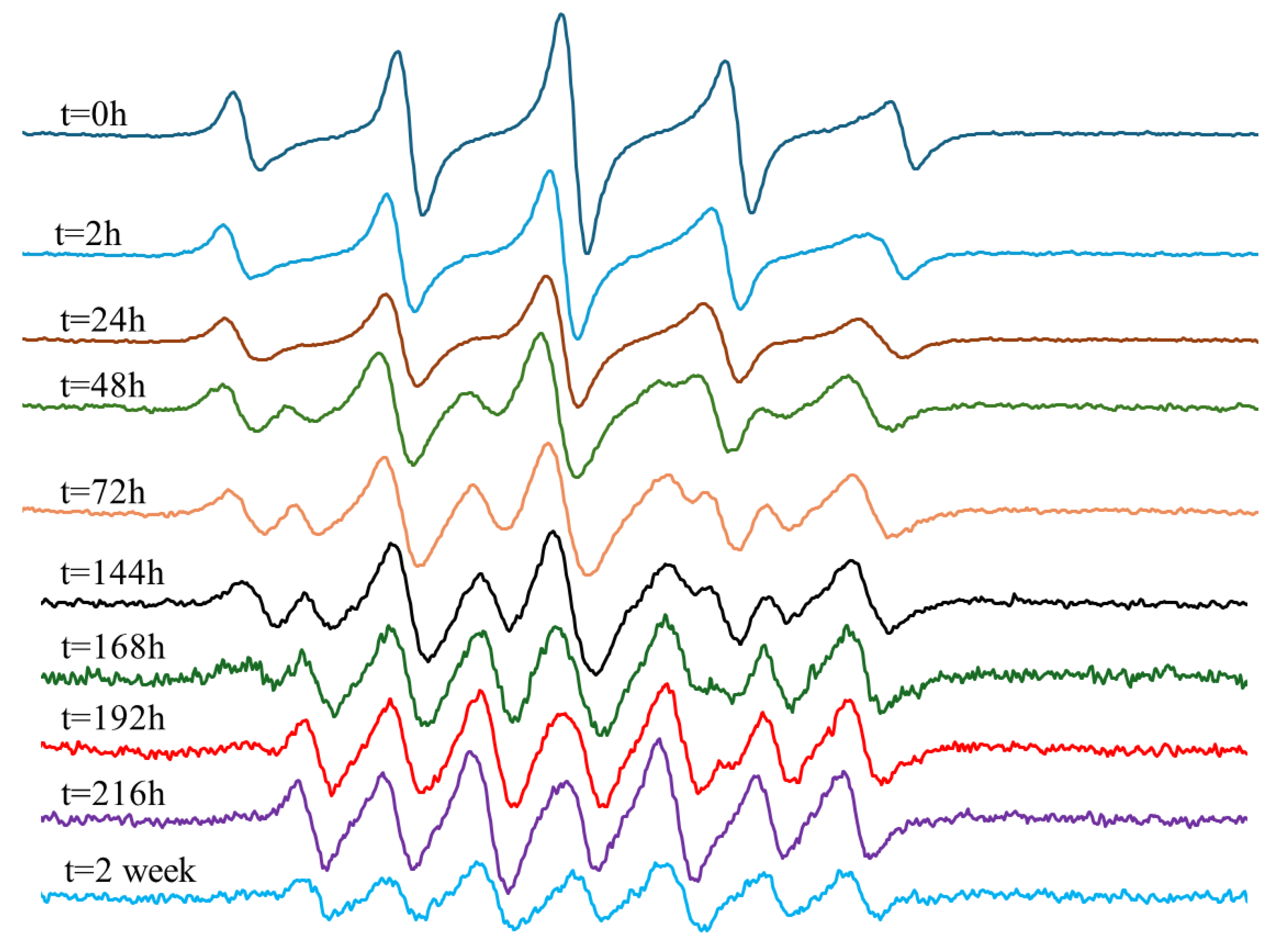

In contrast, the EPR measurement for

In-hMNP (

Figure 10) indicates that at t = 0 the predominant signal observed is PTIO (five peaks), suggesting minimal or no release of NO. However, after 24 h, the initiation of NO release was identified by the signal of PTI, although the PTIO signal remained dominant. Over time, the signal of PTI increased while the signals of PTIO decreased. By t = 144 h, there was a mixture of PTI and PTIO signals. Subsequently, at t = 168 h, there was almost no PTIO signal, with all signals being attributed to PTI (seven peaks). This PTI signal remained stable until t = 216 h, indicating continued NO release which is correlated with the Griess assay result (

Figure 7). At t=2 weeks, the signal began to decrease, possibly due to the cessation of NO release, leading to the oxidation of PTIO and PTI by nitrite, a product of the reduction reaction as explained above in the experimental section. The results presented demonstrate the

In-hMNP ability to release nitric oxide over up to two weeks, highlighting their potential to improve treatment outcomes.

Figure 8.

EPR measurement of Out-hMNP purified with DCM.

Figure 8.

EPR measurement of Out-hMNP purified with DCM.

Figure 9.

EPR measurement of HSA NPs solution with NOC18.

Figure 9.

EPR measurement of HSA NPs solution with NOC18.

Figure 10.

EPR measurement of In-hMNP purified with DCM.

Figure 10.

EPR measurement of In-hMNP purified with DCM.

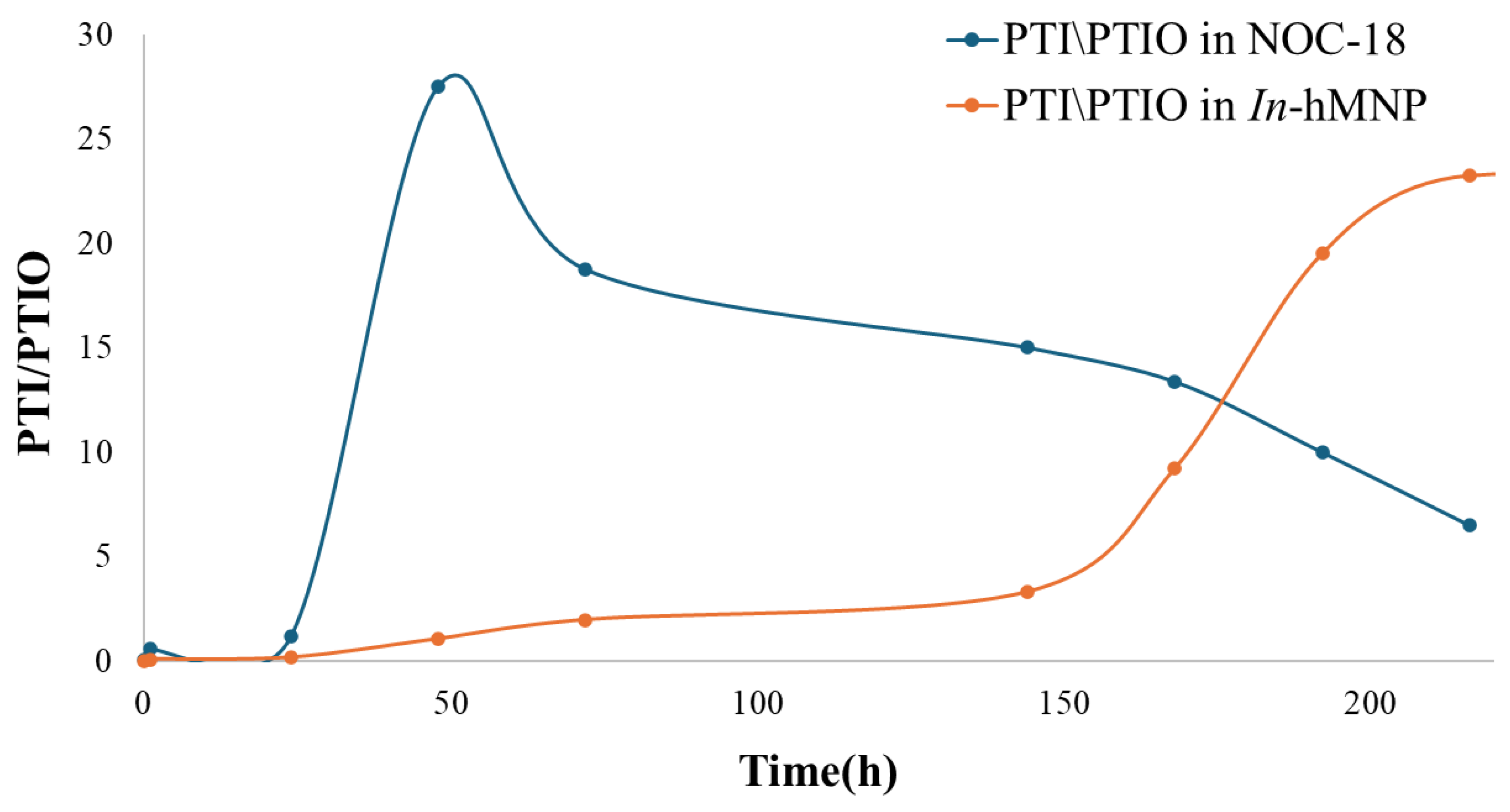

To have some quantitative information on the NO concentration in the solution we used the PTI/PTIO ratio. This ratio of the EPR's peaks height is proportional to the solution NO concentration (equations 4-6) reflecting NO concentration at a given time. Therefore, we calculated this ratio from the EPR spectra (

Figure 2) as a function of time following the preparation of NOC-18 or NOC-18-loaded nanoparticle samples.

As shown in

Figure 11, the peak for NO release is 48 h in the NOC-18 solution and 200 h for the

In-hMNP solution (

Figure 11). In NOC-18, we observed an increase in the signal of PTI till t=24 h, where this increase is followed by a subsequent decline in the ratio. This decline suggests that there is no further NO release after 24 h.

In-hMNP there is a gradual increase in the ratio reaching a maximum after 200 h indicating a slow release of NO from the nanoparticles to the solution. A decline in the ratio was observed after 200 h of incubation when most of the NO was released.

These results indicate that the optimal candidate for NO delivery to the tumor is the In-hMNP. This composite exhibits a prolonged and stable release of NO with a half-life of 200 h according to the EPR data. Moreover, the CM NPs offer the NOC-18 protection from any undesirable reactions. These combined benefits of sustained NO release and the protection from the unfavorable environment imparted by CM NPs, suggest that these nanoparticles could be a useful tool for augmentation of the EPR effect in the tumor.