Submitted:

20 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Alginate Hydrogels

1.2. Simulation/Model of Alginate Hydrogel Formation

1.3. Analysis of Hydrogel Cross-Linking Process

1.4. Alginate Hydrogels in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine

1.5. Rationale Predicting Alginate Hydrogel Gelation

2. Materials and Methods

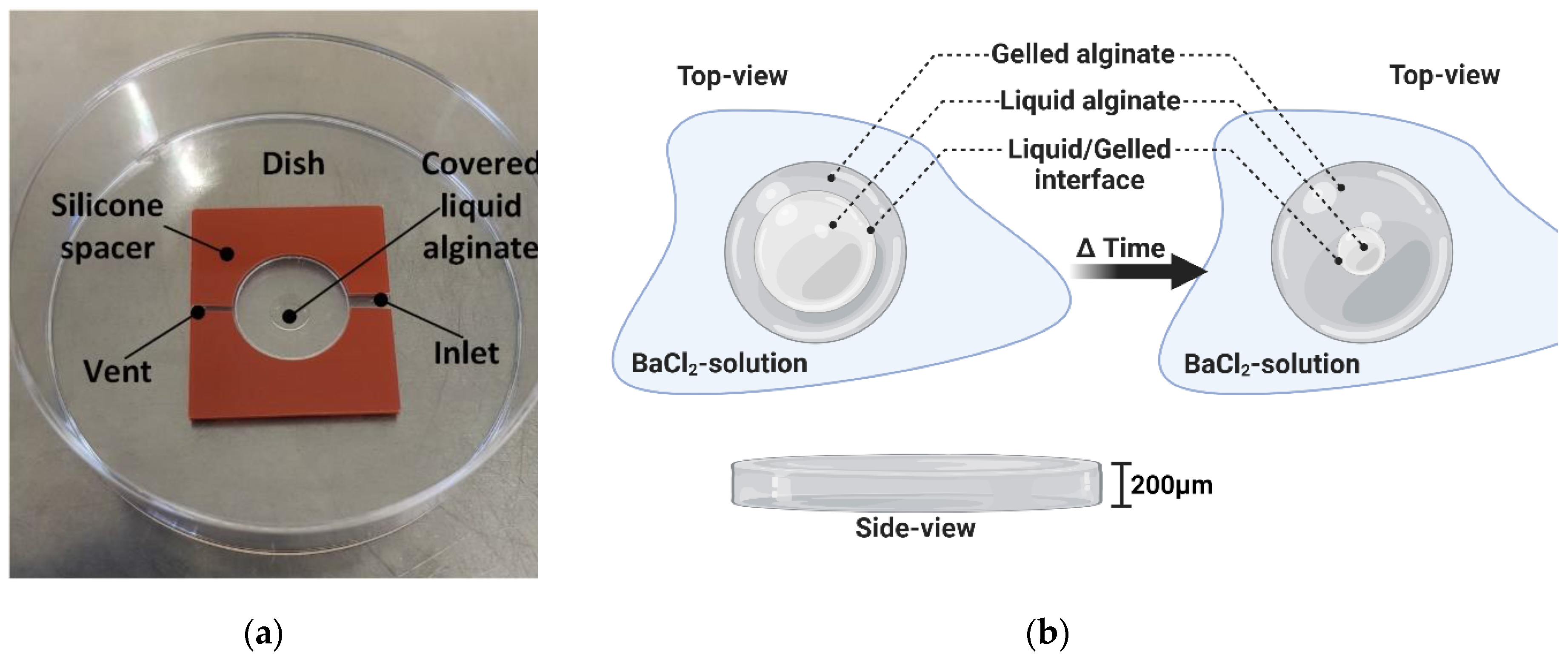

2.1. Disc-Shaped Alginate Gelation Kinetics Study

2.1. Sphere-Shaped Alginate Gelation

2.2. Modelling

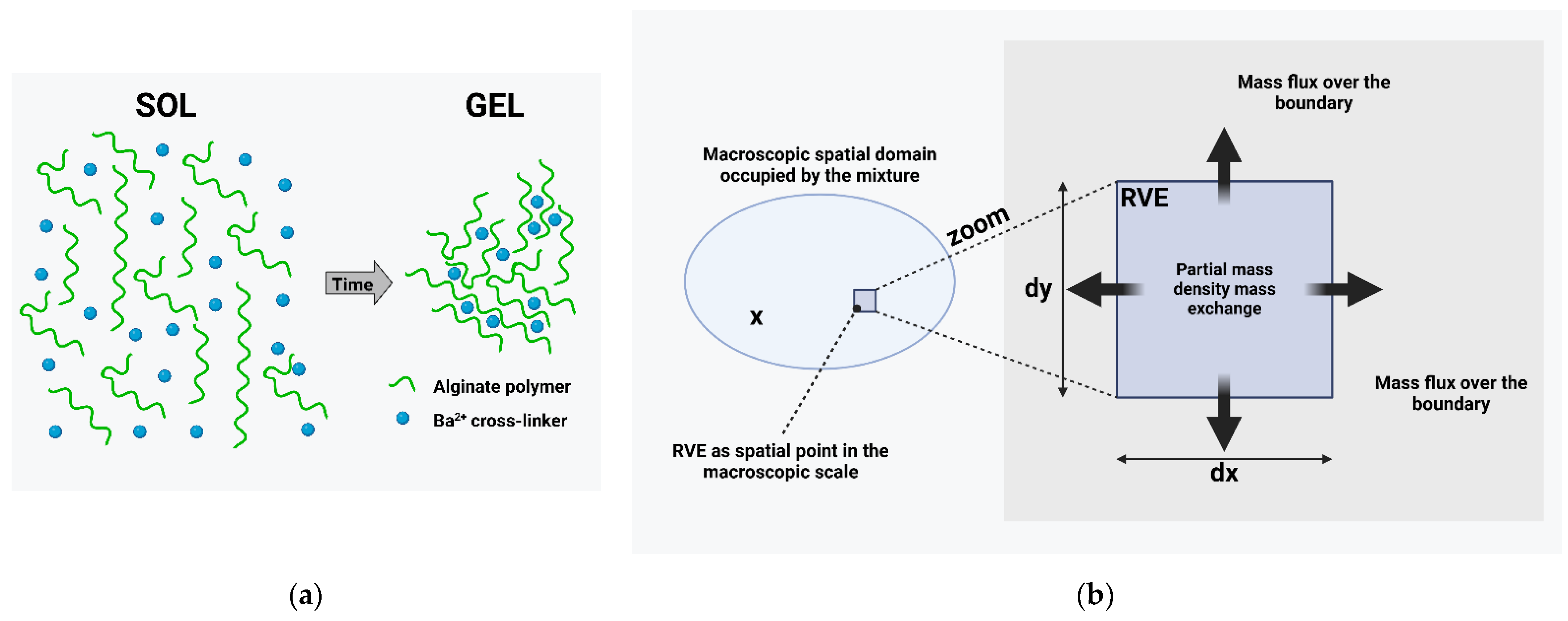

2.2.1. Basic Assumptions

2.2.2. Mixture Theory

2.2.3. Constitutive Equations

2.3. Implementation

3. Results

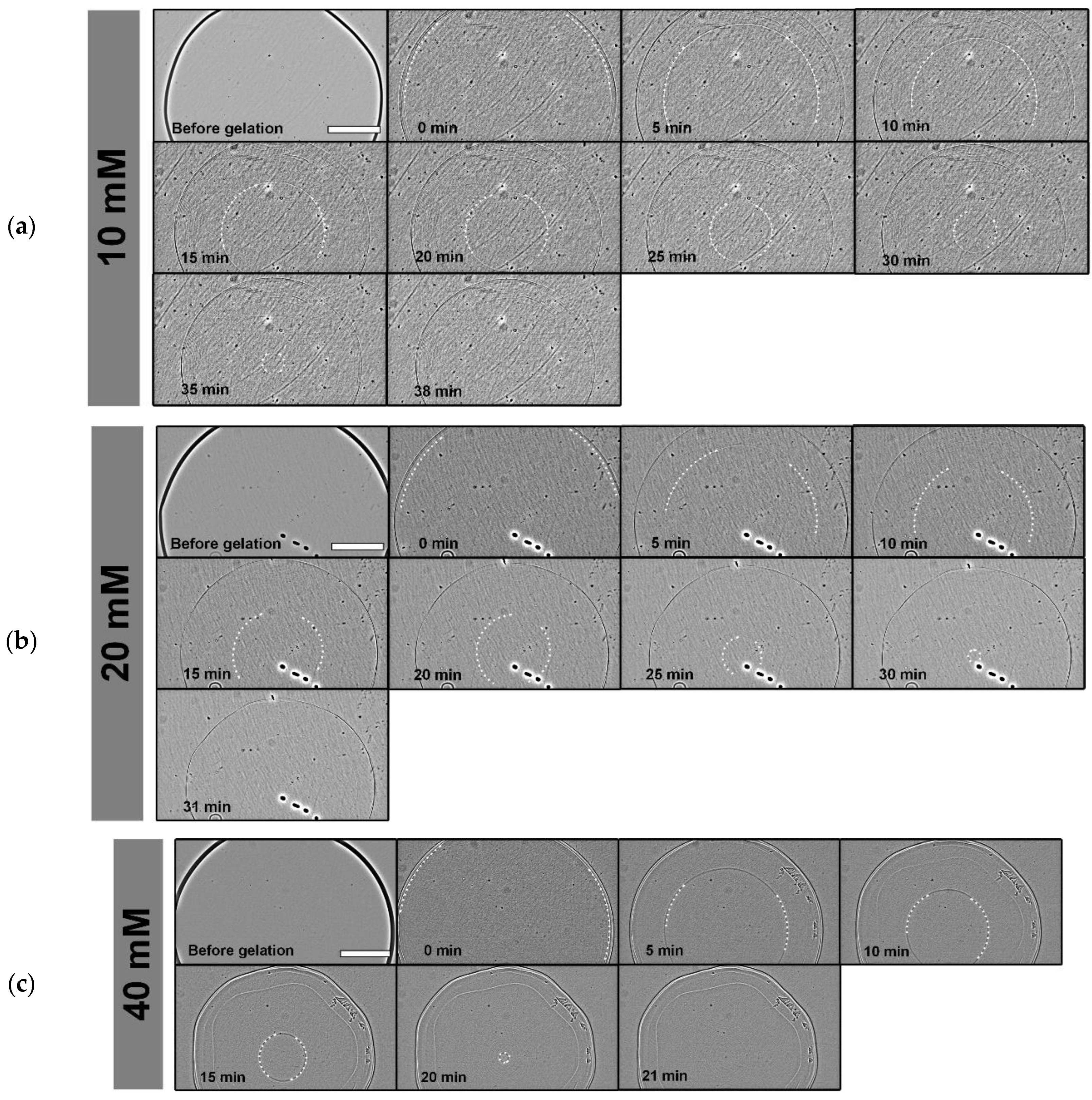

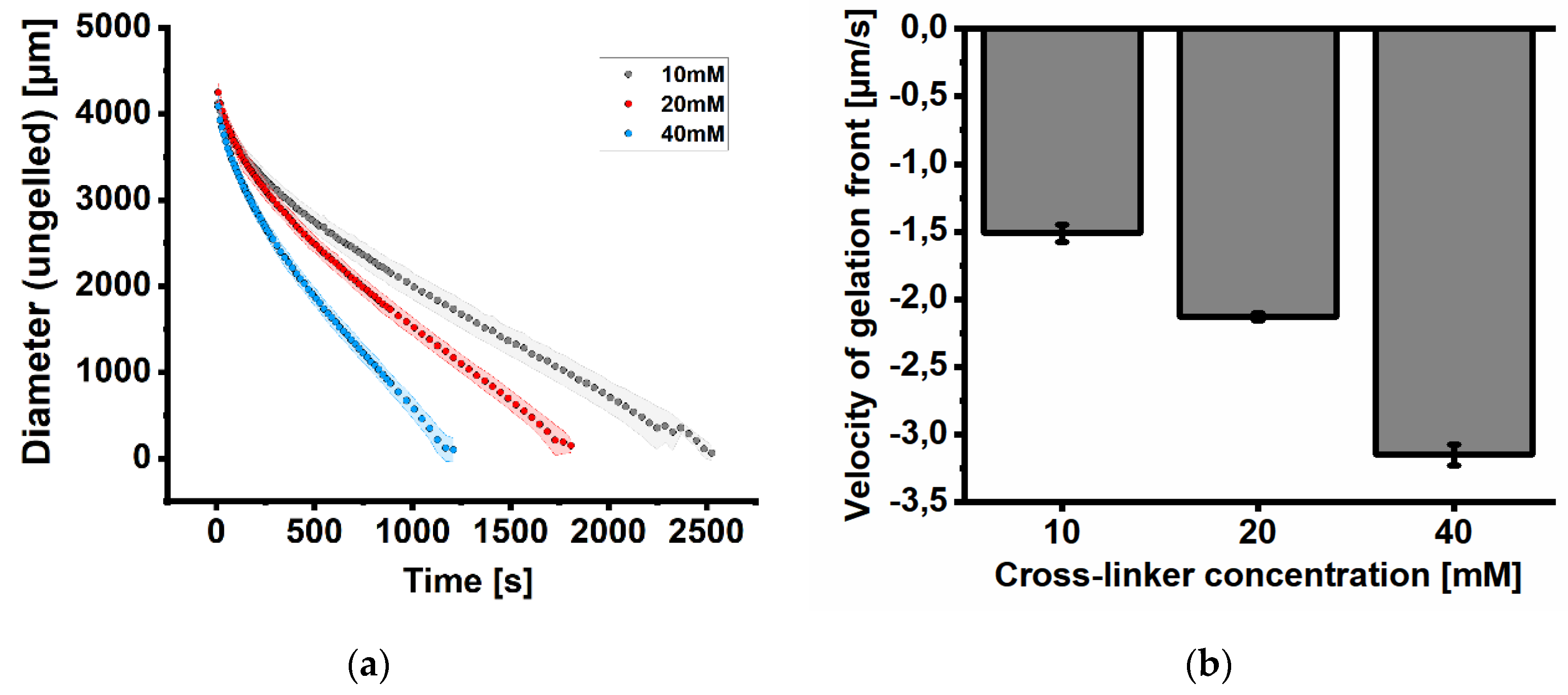

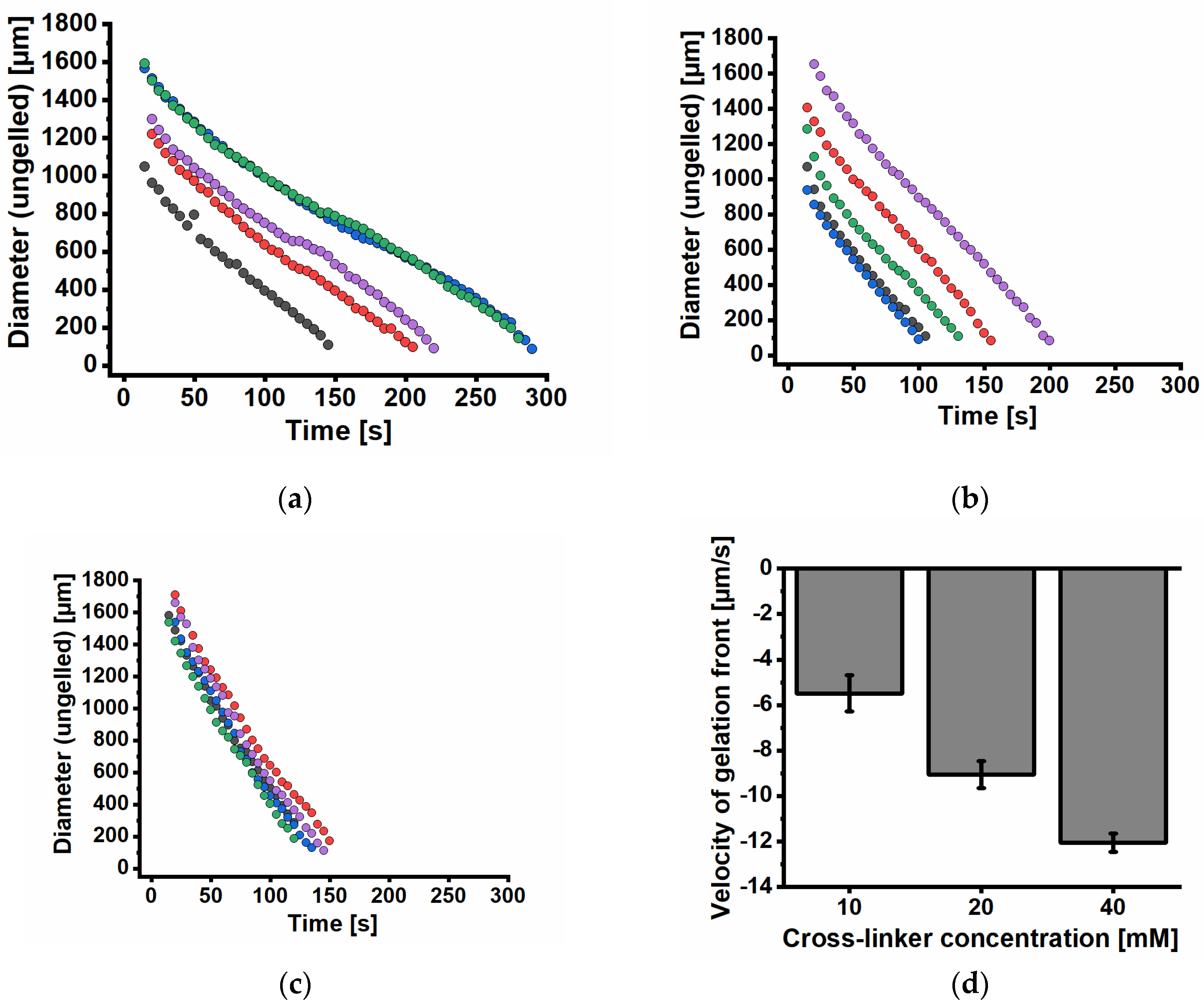

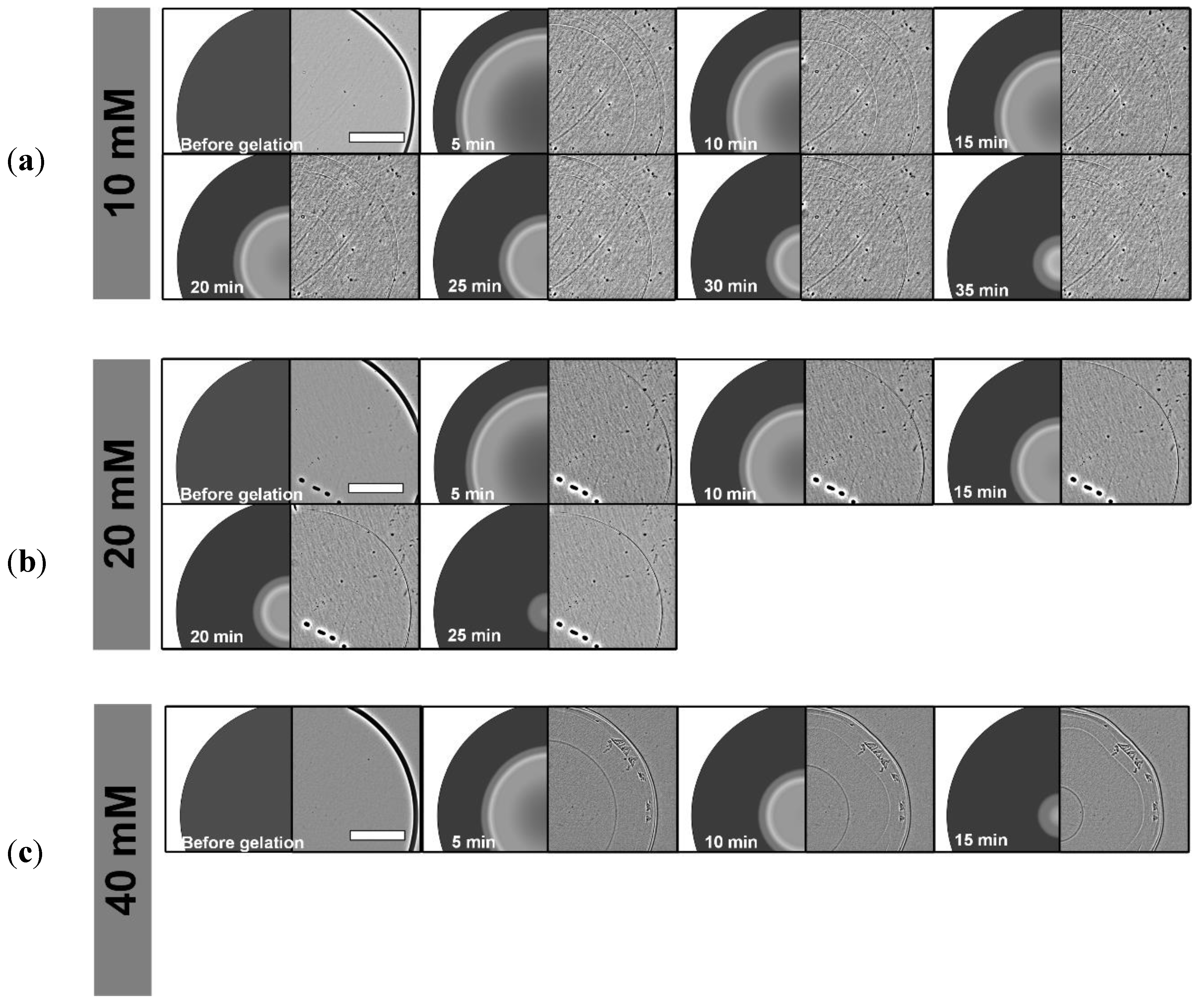

3.1. Alginate Gelation

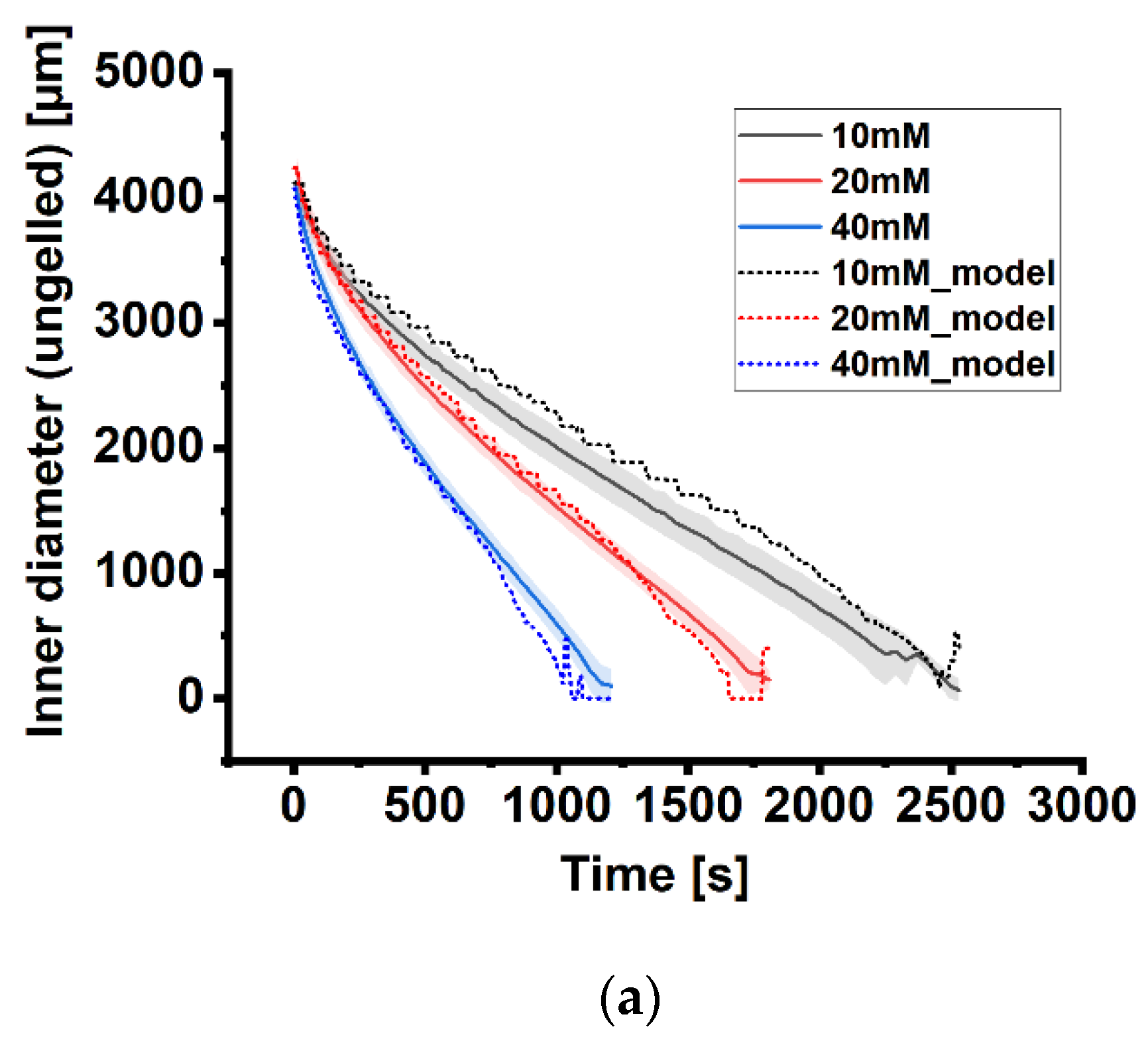

3.2. Numerical Solution

4. Discussion

4.1. Alginate Gelation

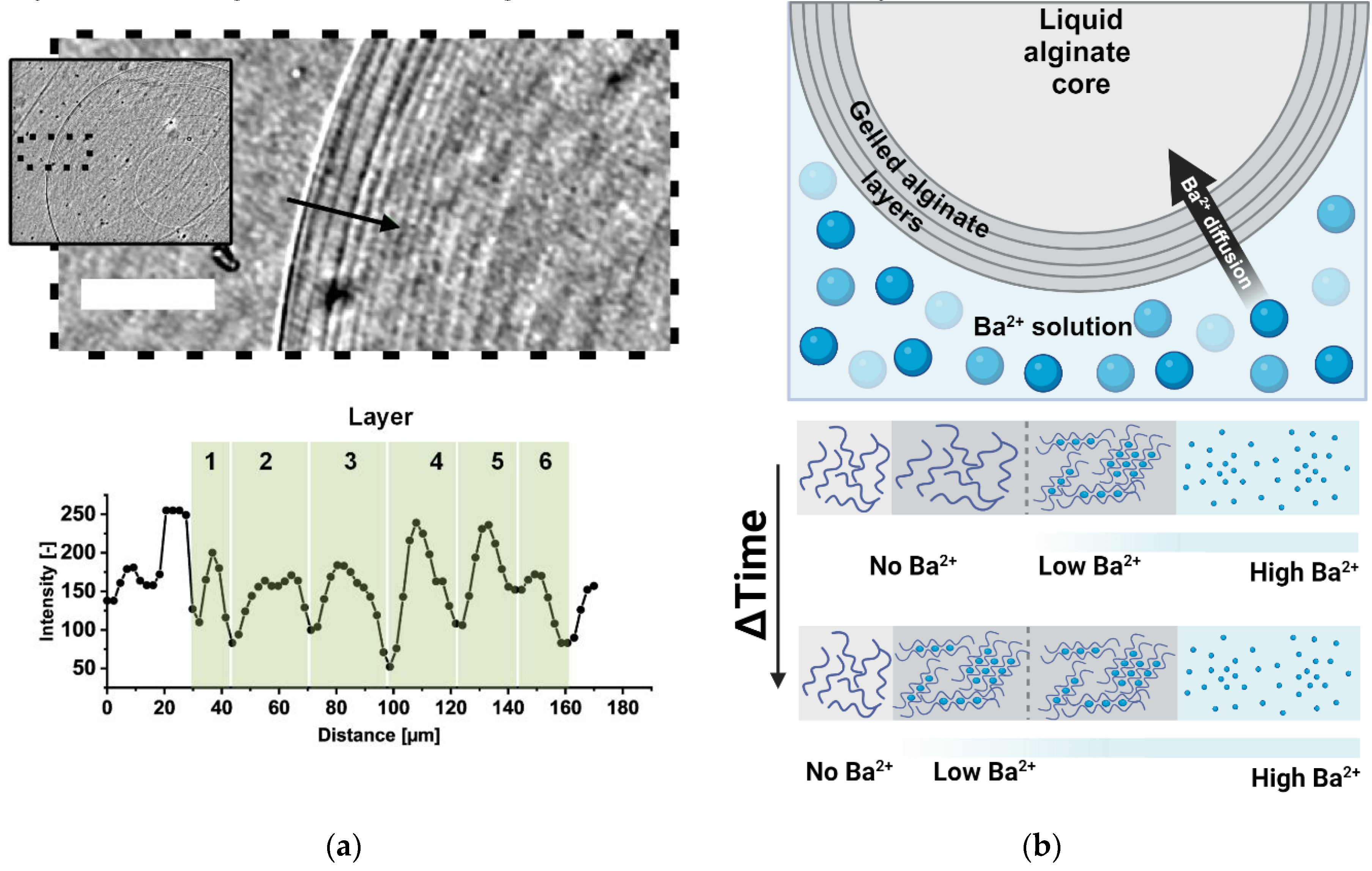

4.2. Layer-Wise Gelation

4.3. Numerical Simulation

5. Conclusion and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schulz, A.; Gepp, M.M.; Stracke, F.; Briesen, H. von; Neubauer, J.C.; Zimmermann, H. Tyramine-conjugated alginate hydrogels as a platform for bioactive scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almari, B.; Brough, D.; Harte, M.; Tirella, A. Fabrication of Amyloid-β-Secreting Alginate Microbeads for Use in Modelling Alzheimer’s Disease. JOVE 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanström, A.; Rosendahl, J.; Salerno, S.; Leiva, M.C.; Gregersson, P.; Berglin, M.; Bogestål, Y.; Lausmaa, J.; Oko, A.; Chinga-Carrasco, G.; et al. Optimized alginate-based 3D printed scaffolds as a model of patient derived breast cancer microenvironments in drug discovery. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 16, 45046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gepp, M.M.; Fischer, B.; Schulz, A.; Dobringer, J.; Gentile, L.; Vásquez, J.A.; Neubauer, J.C.; Zimmermann, H. Bioactive surfaces from seaweed-derived alginates for the cultivation of human stem cells. J. Appl. Phycol. 2017, 29, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, U.; Mimietz, S.; Zimmermann, H.; Hillgärtner, M.; Schneider, H.; Ludwig, J.; Hasse, C.; Haase, A.; Rothmund, M.; Fuhr, G. Hydrogel-based non-autologous cell and tissue therapy. Biotechniques 2000, 29, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storz, H.; Müller, K.J.; Ehrhart, F.; Gómez, I.; Shirley, S.G.; Gessner, P.; Zimmermann, G.; Weyand, E.; Sukhorukov, V.L.; Forst, T.; et al. Physicochemical features of ultra-high viscosity alginates. Carbohydr. Res. 2009, 344, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, H.; Zimmermann, U.; Zimmermann, H.; Kulicke, W.-M. Viscoelastic properties of ultra-high viscosity alginates. Rheol. Acta 2010, 49, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H.; Shirley, S.G.; Zimmermann, U. Alginate-based encapsulation of cells: Past, present, and future. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2007, 7, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, H.; Zimmermann, D.; Reuss, R.; Feilen, P.J.; Manz, B.; Katsen, A.; Weber, M.; Ihmig, F.R.; Ehrhart, F.; Geßner, P.; et al. Towards a medically approved technology for alginate-based microcapsules allowing long-term immunoisolated transplantation. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M.B.; Gray, S.R.; Vasiljevic, T.; Orbell, J.D. The role of poly-M and poly-GM sequences in the metal-mediated assembly of alginate gels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 112, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braccini, I.; Pérez, S. Molecular basis of Ca2+-induced gelation in alginates and pectins: The egg-box model revisited. Biomacromolecules 2001, 2, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Fang, Y.; Vreeker, R.; Appelqvist, I.; Mendes, E. Reexamining the egg-box model in calcium-alginate gels with X-ray diffraction. Biomacromolecules 2007, 8, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plazinski, W. Molecular basis of calcium binding by polyguluronate chains. Revising the egg-box model. J. Computat. Chem. 2011, 32, 2988–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K.; Yan, K.C.; Sun, W. A computational modeling approach for the characterization of mechanical properties of 3D alginate tissue scaffolds. J. Appl. Biomater. Biomech. 2008, 6, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Külcü, İ.D. A Constitutive Model for Alginate-Based Double Network Hydrogels Cross-Linked by Mono-, Di-, and Trivalent Cations. Gels 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arruda, E.M.; Boyce, M.C. A three-dimensional constitutive model for the large stretch behavior of rubber elastic materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1993, 41, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargazany, R.; Itskov, M. A network evolution model for the anisotropic Mullins effect in carbon black filled rubbers. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2009, 46, 2967–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindjee, S.; Simo, J. A micro-mechanically based continuum damage model for carbon black-filled rubbers incorporating Mullins’ effect. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1991, 39, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marckmann, G.; Verron, E.; Gornet, L.; Chagnon, G.; Charrier, P.; Fort, P. A theory of network alteration for the Mullins effect. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2002, 50, 2011–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, A.; Elgsaeter, A. Density distribution of calcium-induced alginate gels. A numerical study. Biopolymers 1995, 36, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thu, B.; Gåserød, O.; Paus, D.; Mikkelsen, A.; Skjåk-Bræk, G.; Toffanin, R.; Vittur, F.; Rizzo, R. Inhomogeneous alginate gel spheres: An assessment of the polymer gradients by synchrotron radiation-induced x-ray emission, magnetic resonance microimaging, and mathematical modeling. Biopolymers 2000, 53, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnøy, S.H.; Mandaric, S.; Bassett, D.C.; Slund, A.K.O.; Ucar, S.; Andreassen, J.-P.; Strand, B.L.; Sikorski, P. Gelling kinetics and in situ mineralization of alginate hydrogels: A correlative spatiotemporal characterization toolbox. Acta Biomater. 2016, 44, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huynh, U.T.; Chambin, O.; Du Poset, A.M.; Assifaoui, A. Insights into gelation kinetics and gel front migration in cation-induced polysaccharide hydrogels by viscoelastic and turbidity measurements: Effect of the nature of divalent cations. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 190, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.-B.; Bhandari, B.R.; Howes, T. Quantification of calcium alginate gel formation during ionic cross-linking by a novel colourimetric technique. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 533, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Luo, X.; Betz, J.; Payne, G.F.; Bentley, W.E.; Rubloff, G.W. Mechanism of anodic electrodeposition of calcium alginate. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 5677–5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, E.; Roversi, T.; Buzzaccaro, S.; Piazza, L.; Piazza, R. Biopolymer gels with “physical” cross-links: gelation kinetics, aging, heterogeneous dynamics, and macroscopic mechanical properties. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajikhani, A.; Scocozza, F.; Conti, M.; Marino, M.; Auricchio, F.; Wriggers, P. Experimental characterization and computational modeling of hydrogel cross-linking for bioprinting applications. IJAO 2019, 42, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajikhani, A.; Marino, M.; Wriggers, P. Computational modeling of hydrogel cross-linking based on reaction-diffusion theory. Proc. Appl. Math. Mech. 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stößlein, S.; Grunwald, I.; Stelten, J.; Hartwig, A. In-situ determination of time-dependent alginate-hydrogel formation by mechanical texture analysis. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 205, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cesewski, E.; Singh, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Haring, A.P.; Johnson, B.N. Real-time monitoring of hydrogel rheological property changes and gelation processes using high-order modes of cantilever sensors. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 174502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, K.; Balcom, B.J.; Carpenter, T.; Hall, L.D. The gelation of sodium alginate with calcium ions studied by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Carbohydr. Res. 1994, 257, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnøy, S.H.; Mandaric, S.; Bassett, D.C.; Slund, A.K.O.; Ucar, S.; Andreassen, J.-P.; Strand, B.L.; Sikorski, P. Gelling kinetics and in situ mineralization of alginate hydrogels: A correlative spatiotemporal characterization toolbox. Acta Biomater. 2016, 44, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, D.; Yu, W. Characterization of the structure and diffusion behavior of calcium alginate gel beads. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; He, J.; Huang, Y. A new insight to the effect of calcium concentration on gelation process and physical properties of alginate films. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 5791–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besiri, I.N.; Goudoulas, T.B.; Fattahi, E.; Becker, T. In situ evaluation of alginate-Ca 2+ gelation kinetics. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidsrød, O.; Skjåk-Bræk, G. Alginate as immobilization matrix for cells. Trends Biotechnol. 1990, 8, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosseva, M.R. Immobilization of Microbial Cells in Food Fermentation Processes. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 1089–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groboillot, A.; Boadi, D.K.; Poncelet, D.; Neufeld, R.J. Immobilization of Cells for Application in the Food Industry. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1994, 14, 75–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraser, J.E.; Bickerstaff, G.F. Entrapment in Calcium Alginate. Immobilization of Enzymes and Cells; Springer, 1997; pp 61–66.

- Takahashi, K.; Tanabe, K.; Ohnuki, M.; Narita, M.; Ichisaka, T.; Tomoda, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 2007, 131, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, K.; Yamanaka, S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 2006, 126, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaicharoenaudomrung, N.; Kunhorm, P.; Noisa, P. Three-dimensional cell culture systems as an in vitro platform for cancer and stem cell modeling. WJSC 2019, 11, 1065–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirbagheri, M.; Adibnia, V.; Hughes, B.R.; Waldman, S.D.; Banquy, X.; Hwang, D.K. Advanced cell culture platforms: a growing quest for emulating natural tissues. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6, 45–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georges, P.C.; Janmey, P.A. Cell type-specific response to growth on soft materials. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985) 2005, 98, 1547–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, C.; Teng, Y. Is It Time to Start Transitioning From 2D to 3D Cell Culture? Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imamura, Y.; Mukohara, T.; Shimono, Y.; Funakoshi, Y.; Chayahara, N.; Toyoda, M.; Kiyota, N.; Takao, S.; Kono, S.; Nakatsura, T.; et al. Comparison of 2D- and 3D-culture models as drug-testing platforms in breast cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1837–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higuchi, A.; Ling, Q.-D.; Chang, Y.; Hsu, S.-T.; Umezawa, A. Physical Cues of Biomaterials Guide Stem Cell Differentiation Fate. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3297–3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Zhou, J.; Chowdhury, F.; Cheng, J.; Wang, N.; Wang, F. Role of mechanical factors in fate decisions of stem cells. Regen. Med. 2011, 6, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, T.; Georges, P.C.; Flanagan, L.A.; Marg, B.; Ortiz, M.; Funaki, M.; Zahir, N.; Ming, W.; Weaver, V.; Janmey, P.A. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 2005, 60, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Yong, K.M.A.; Villa-Diaz, L.G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, W.; Philson, R.; Weng, S.; Xu, H.; Krebsbach, P.H.; Fu, J. Hippo/YAP-mediated rigidity-dependent motor neuron differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirella, A.; Orsini, A.; Vozzi, G.; Ahluwalia, A. A phase diagram for microfabrication of geometrically controlled hydrogel scaffolds. Biofabrication 2009, 1, 45002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holte, O.; Tønnesen, H.H.; Karlsen, J. Measurement of diffusion through calcium alginate gel matrices. Pharmazie 2006, 61, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rui Rodrigues, J.; Lagoa, R. Copper Ions Binding in Cu-Alginate Gelation. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2006, 25, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebels, S.; Gepp, M.M.; Meiser, I.; Roland, M.; Stracke, F.; Zimmermann, H. A multiphase model for the cross-linking of ultra-high viscous alginate hydrogels. Proc. Appl. Math. Mech. 2021, 20, e202000254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draget, K.I.; Gåserød, O.; Aune, I.; Andersen, P.O.; Storbakken, B.; Stokke, B.T.; Smidsrød, O. Effects of molecular weight and elastic segment flexibility on syneresis in Ca-alginate gels. Food Hydrocoll 2001, 15, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, F.; Mettler, E.; Böse, T.; Weber, M.M.; Vásquez, J.A.; Zimmermann, H. Biocompatible coating of encapsulated cells using ionotropic gelation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Y.; Irudayaraj, J. Multi-layered alginate hydrogel structures and bacteria encapsulation. Chem. Commun. (Chemical communications) 2022, 58, 8584–8587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, J.-Y.; Lam, W.-H.; Ho, K.-W.; Voo, W.-P.; Lee, M.F.-X.; Lim, H.-P.; Lim, S.-L.; Tey, B.-T.; Poncelet, D.; Chan, E.-S. Advances in fabricating spherical alginate hydrogels with controlled particle designs by ionotropic gelationas encapsulation systems. Particuology 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voo, W.-P.; Ooi, C.-W.; Islam, A.; Tey, B.-T.; Chan, E.-S. Calcium alginate hydrogel beads with high stiffness and extended dissolution behaviour. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 75, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, F.; Evans, J.J.; Harris, M.T. Study of sol–gel transition in calcium alginate system by population balance model. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2011, 66, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Parameter |

| 6.78E-12 m2/s | |

| 6.78E-9 m2/s | |

| 2.5 | |

| 2.3 | |

| 1.6E-1 | |

| 8.0E-2 | |

| 2.5E-2 | |

| 2.5E-2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).