Submitted:

19 December 2024

Posted:

20 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Functional Modelling as an Abstraction Method

2.2. Reverse Engineering as Abstraction Method for Knowledge Transfer

2.3. Functional Feature-Based Modelling as a Shape Abstraction Method for Knowledge Transfer

2.4. “Reverse Biomimetics” – Technical, Biology-Based Reverse Engineering as a Shape Abstraction Method

2.5. Large-Scale Human Skeletal Biological Systems - Skull and Hand

2.5.1. Strategies for Capturing the Nature Design Intents

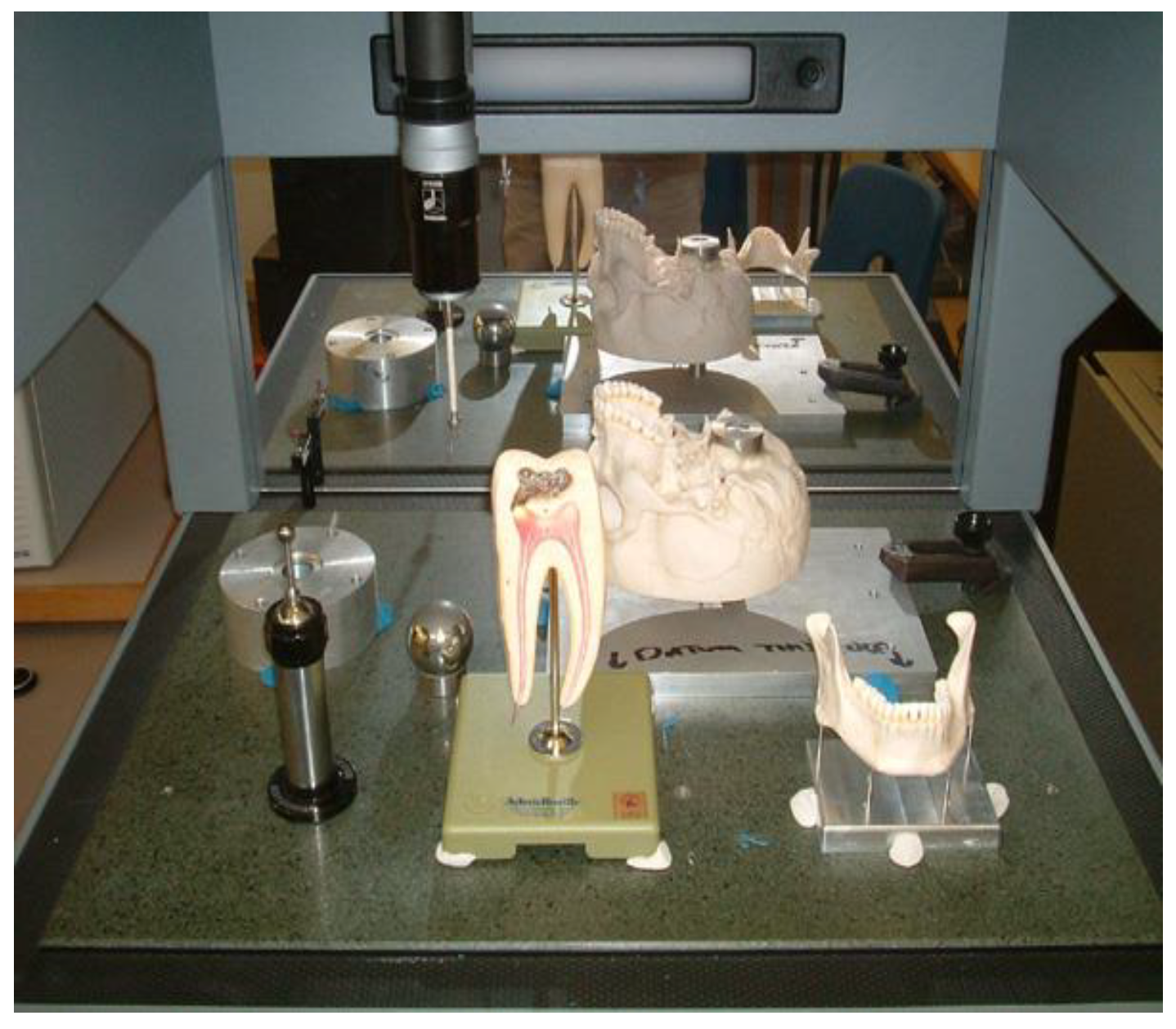

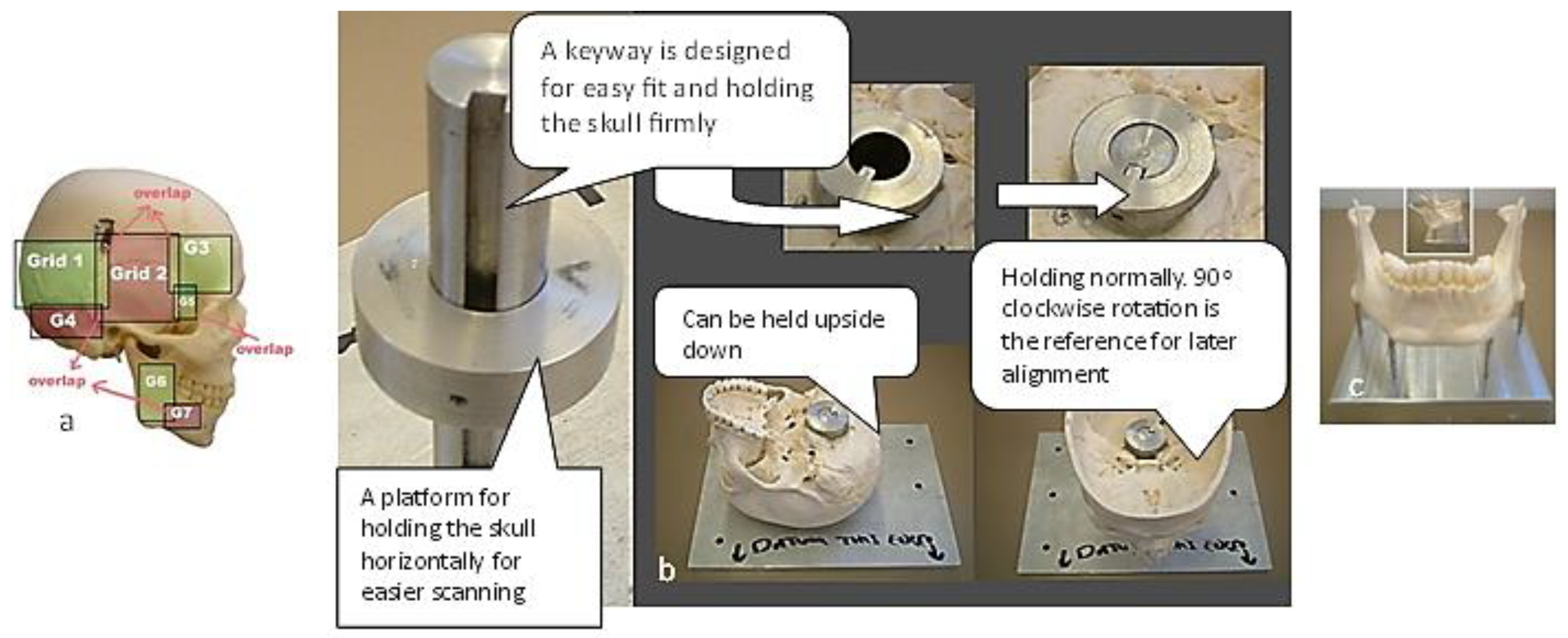

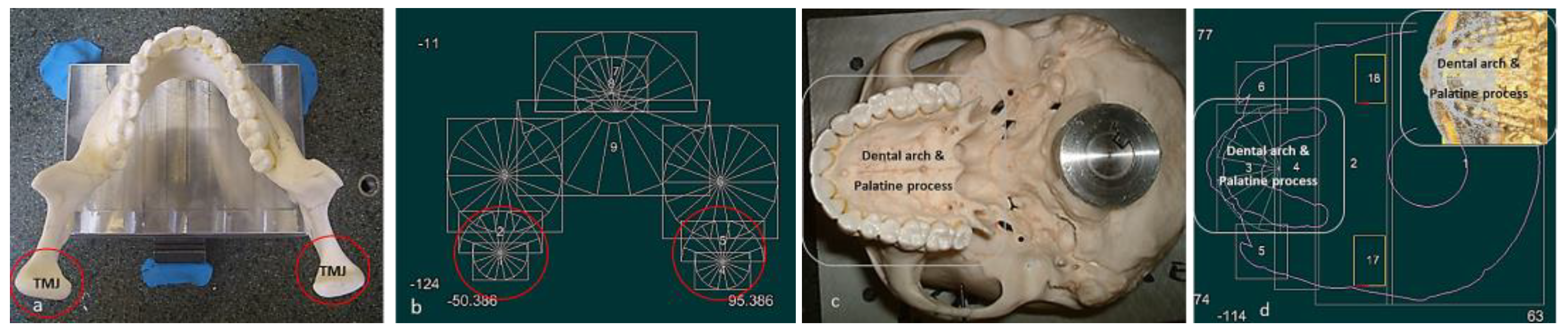

2.5.2. Skull 3D Data Acquisition/Digitisation

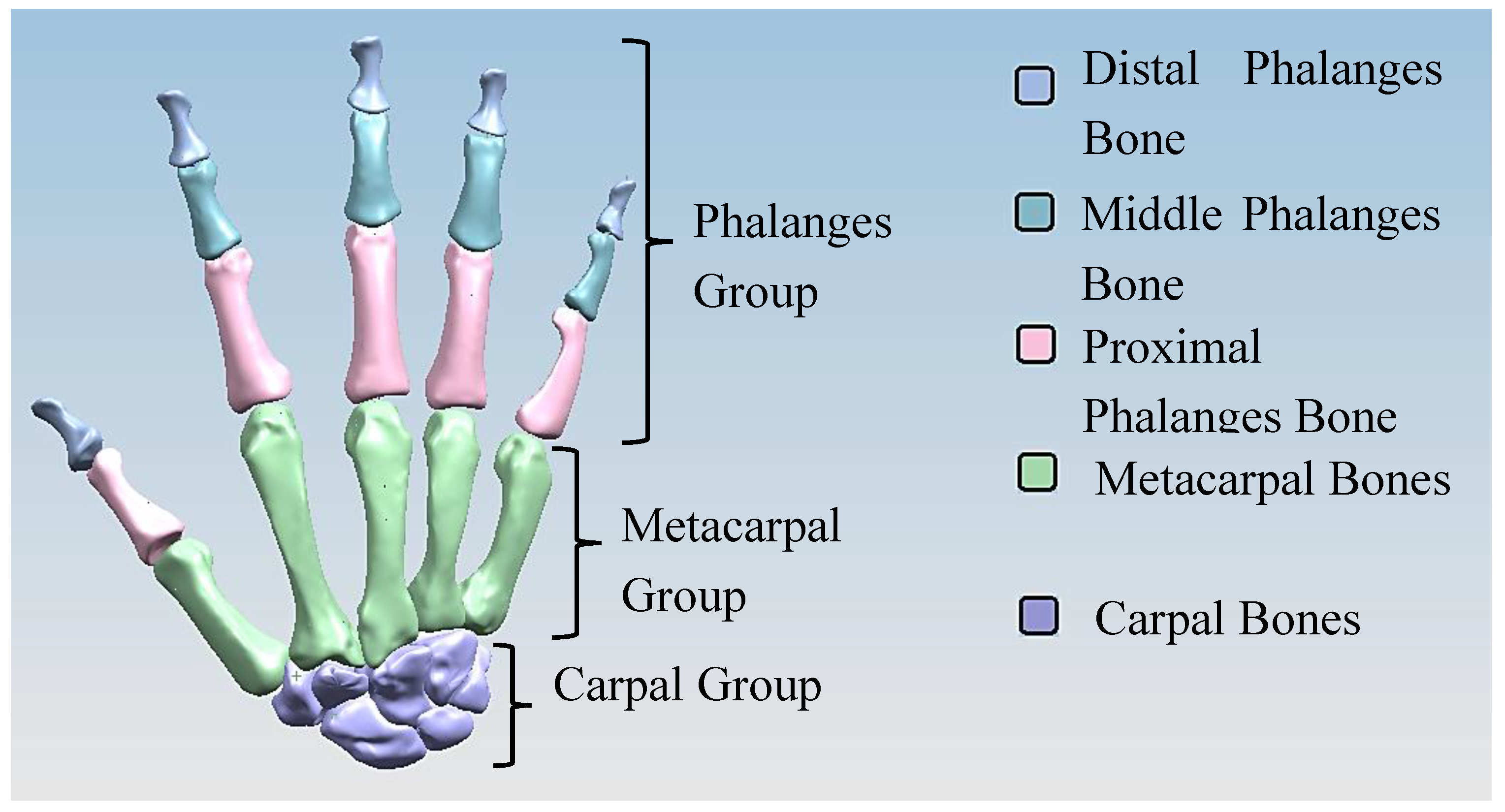

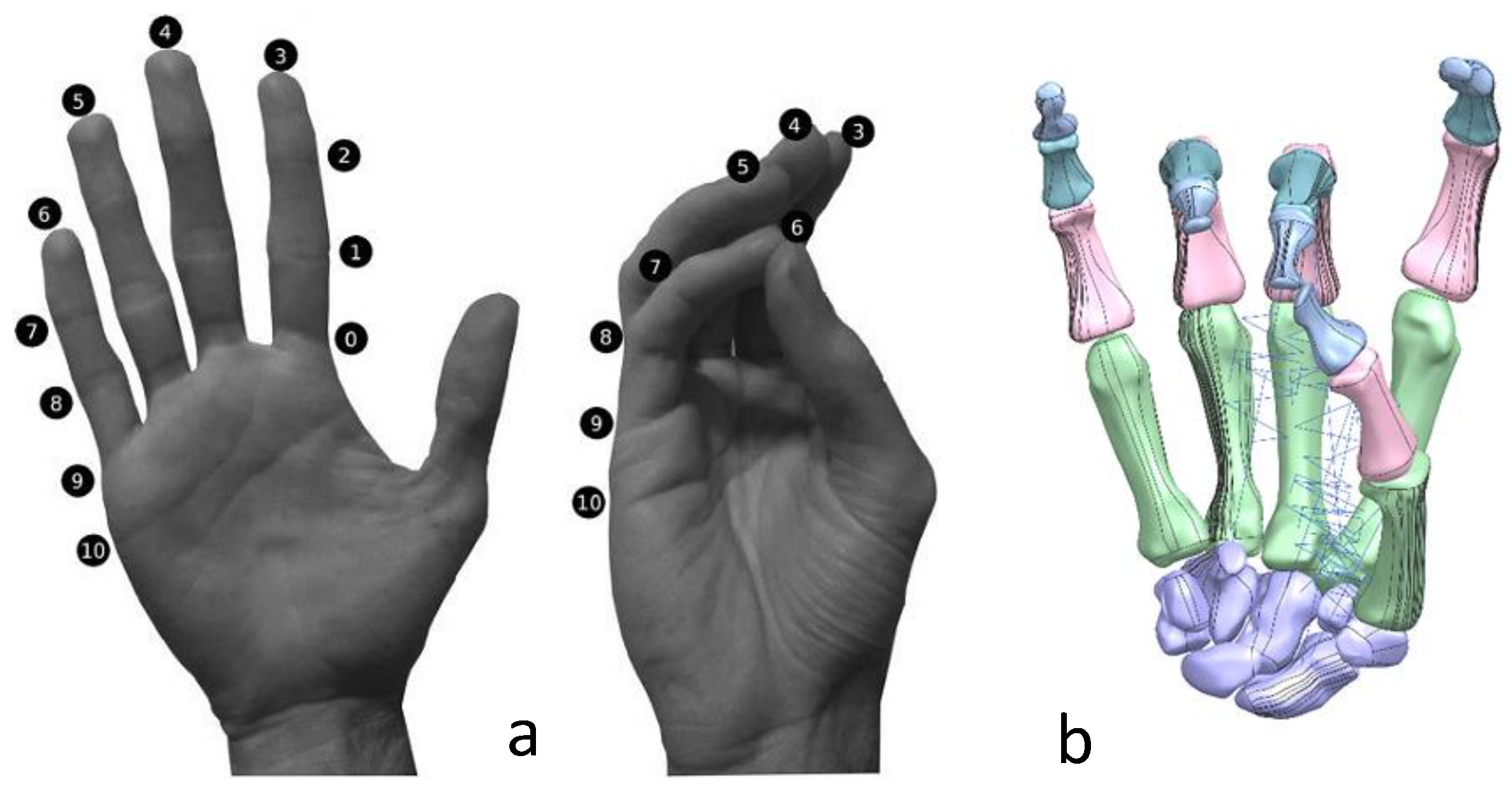

2.5.3. Hand 3D Data Acquisition/Digitisation, RGEs and Segmentation Strategies

2.5.4. Hand Evaluation Strategy – Synergy-Based Approach

3. Results – Innovative, Bio-Inspired Product Development

3.1. Skull 3D Data Acquisition, Biomimetic Modelling and Proof of Concept

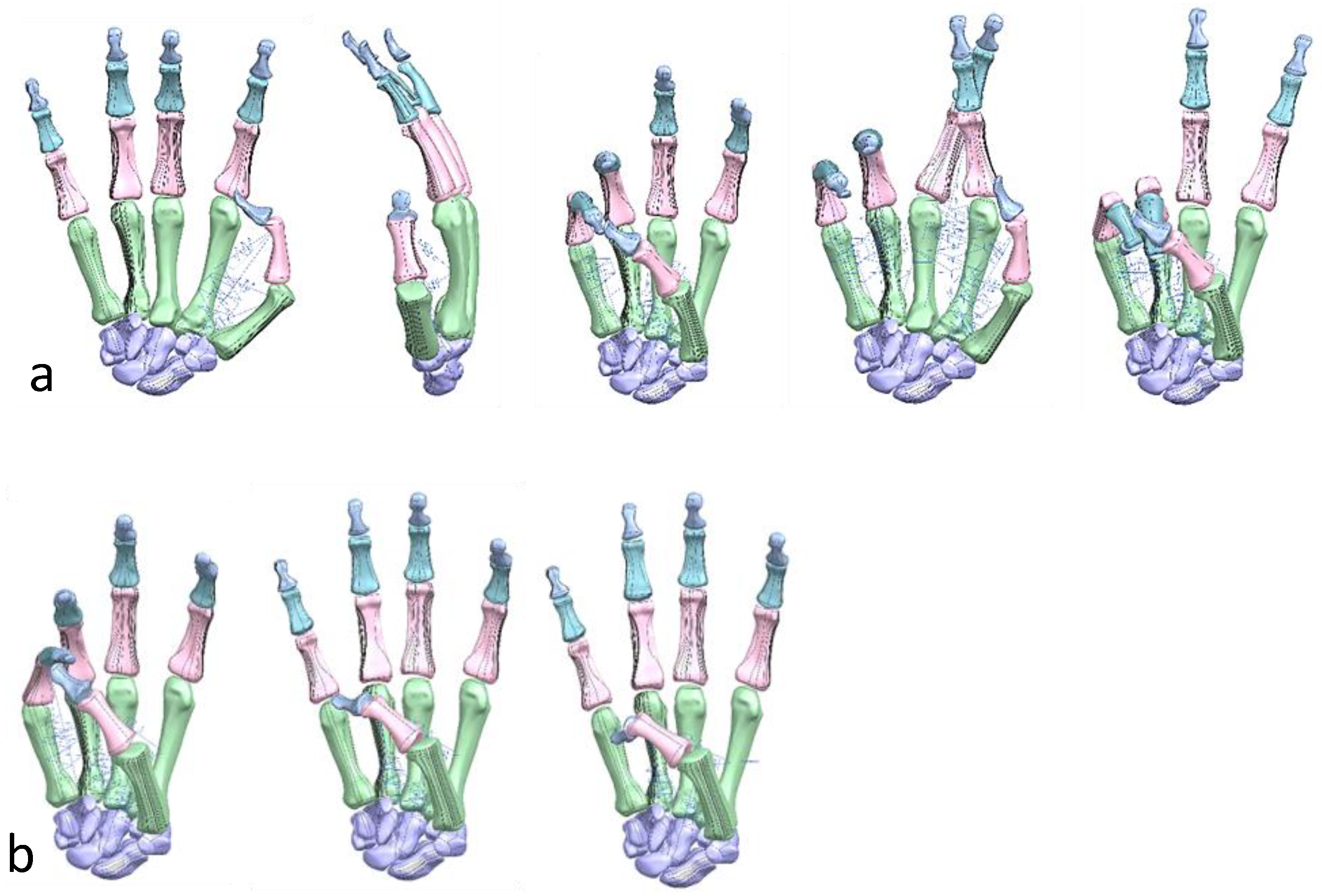

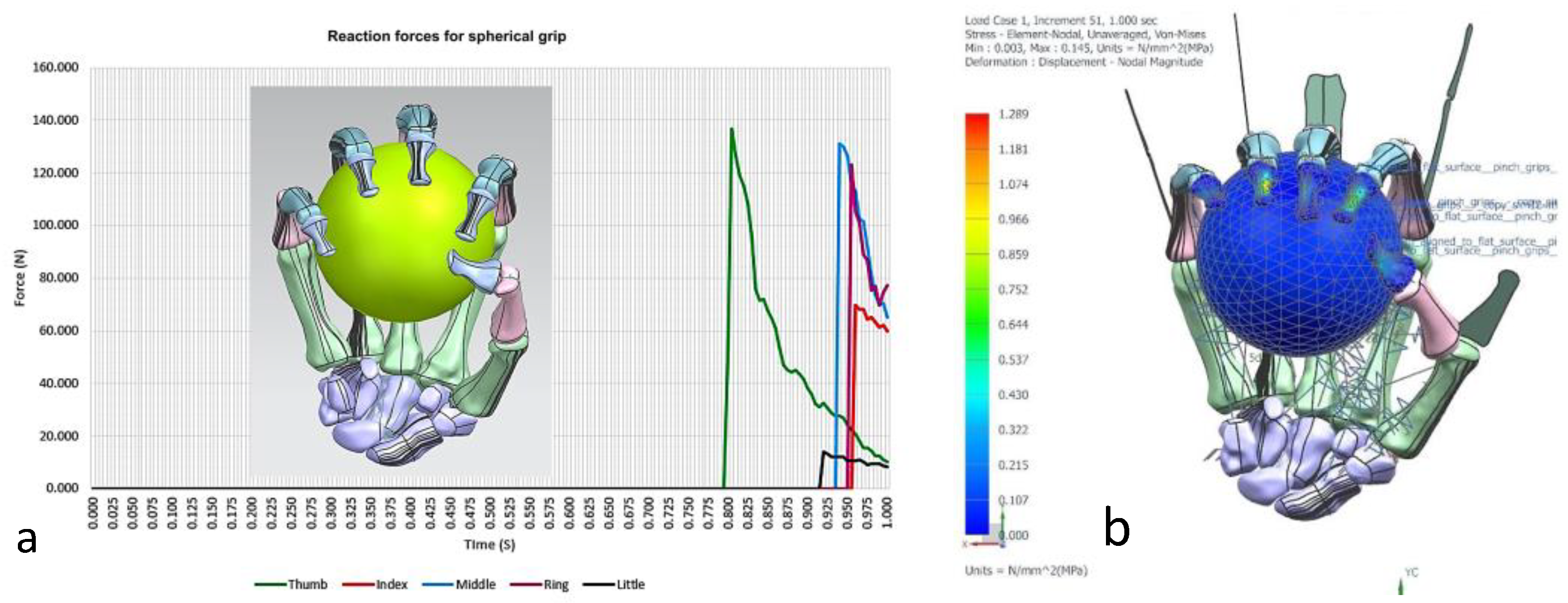

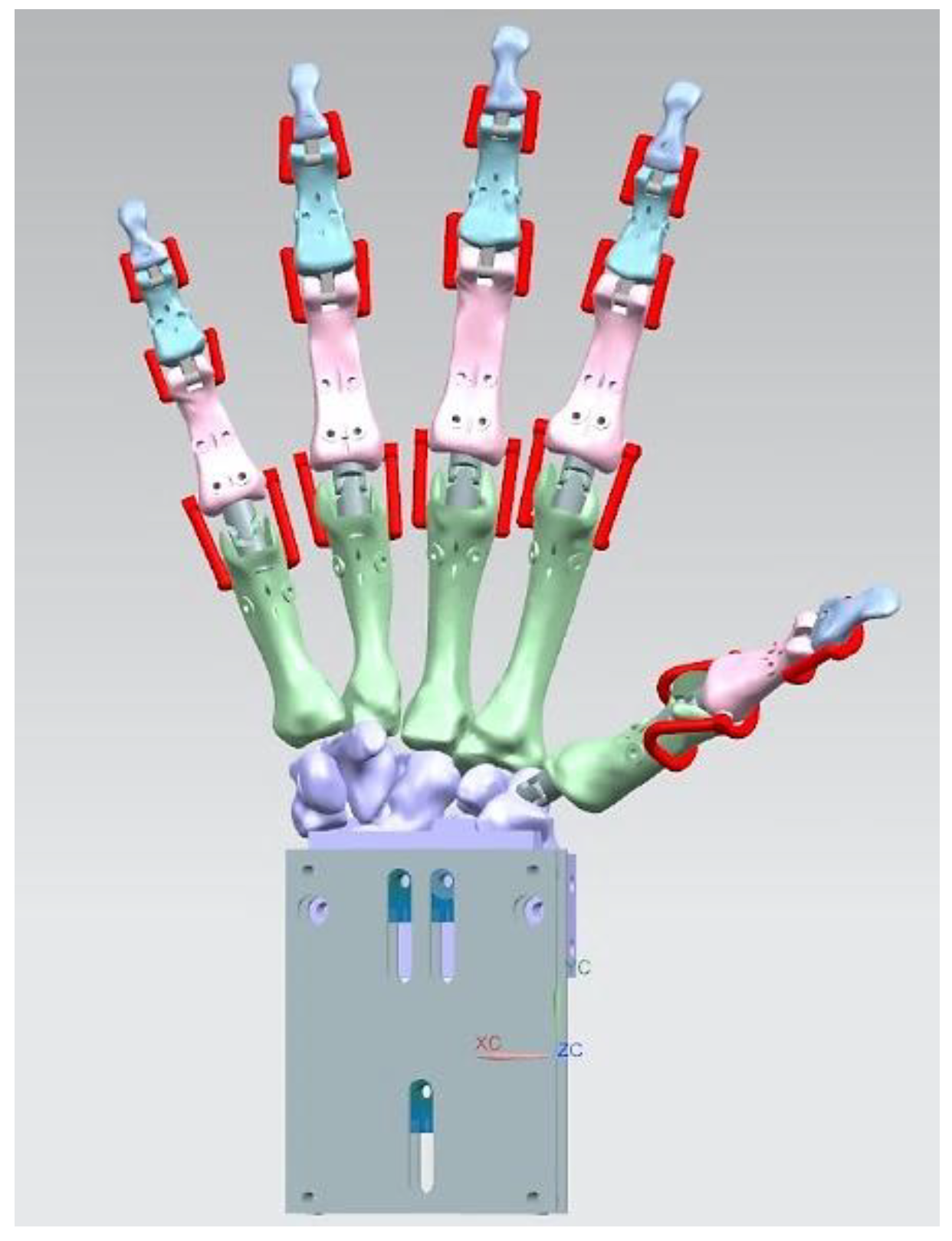

3.2. Hand 3D Data Acquisition, Biomimetic Modelling and Proof of Concept

- Data cleaning of scanned point clouds

- Hand RGEs strategy and segmentation process

- 2.

- Verify the integrity of pre-aligned hand bones solid model

- 3.

- Alignment and functional registration according to RGEs strategy

- 4.

- Numbering Individual Digital Hand Bone

- Identification of centre of joints

- 2.

- Postural synergies simulation and clinical validation

3.2.1. Hand Alignment Evaluation

- Pinch and posing

- 2.

- Grasping various objects

- 3.

- Clinical validation with Fugl-Meyer assessment (FMA) and Kapandji test

- Hand actuation design

- 2.

- Prototyping and concept-proof

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ISO (2015) ISO 18458:2015: Biomimetics – terminology, concepts and methodology. ISO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Hayes, S., Desha, C. and Baumeister, D., 2020. Learning from nature–Biomimicry innovation to support infrastructure sustainability and resilience. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, p.120287. [CrossRef]

- (Benyus, JM. (1997). Biomimicry. New York: William Morrow).

- Wanieck, K., Fayemi, P.E., Maranzana, N., Zollfrank, C. and Jacobs, S., 2017. Biomimetics and its tools. Bioinspired, Biomimetic and Nanobiomaterials, 6(2), pp.53-66.

- Baumeister D, Tocke R, Dwyer J and Ritter S (2013) Biomimicry Resource Handbook: a Seed Bank of Best Practices. Biomimicry 3.8, Missoula, MT, USA.

- McInerney, S.J., Khakipoor, B., Garner, A.M., Houette, T., Unsworth, C.K., Rupp, A., Weiner, N., Vincent, J.F., Nagel, J.K. and Niewiarowski, P.H., 2018. E2BMO: facilitating user interaction with a biomimetic ontology via semantic translation and interface design. Designs, 2(4), p.53. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed-Kristensen, S.; Christensen, B.T.; Lenau, T.A. Naturally original: Stimulating creative design through biological analogies and Random images. In Proceedings of the International Design Conference, DESIGN, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 19–22 May 2014; Volume 2014, pp. 427–436.

- Lenau, T.A.; Pigosso, D.C.A.; McAloone, T.; Lakhtakia, A. Biologically inspired design for environment. In Bioinspiration, Biomimetics, and Bioreplication X; International Society for Optics and Photonics: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; Volume 11374, p. 13.

- Graeff, E., Maranzana, N. and Aoussat, A., 2020. Biological practices and fields, missing pieces of the biomimetics’ methodological puzzle. Biomimetics, 5(4), p.62. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.F.V.; Bogatyreva, O.A.; Bogatyrev, N.R.; Bowyer, A.; Pahl, A.K. Biomimetics: Its practice and theory. J. R. Soc. Interface 2006, 3, 471–482. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J., Y. Jeong, J. W. Hong, and J. Choi. 2015. “Biomimetics: Forecasting the Future of Science, Engineering, and Medicine.” International Journal of Nanomedicine 10: 5701–5713.

- Bar-Cohen, Y. 2006. “Biomimetics - Using Nature to Inspire Human Innovation.” Bioinspiration and Biomimetics 1 (1): P1–P12. doi:10.1088/1748-3182/1/1/P01.

- Fu, K., Moreno, D., Yang, M. and Wood, K.L., 2014. Bio-inspired design: an overview investigating open questions from the broader field of design-by-analogy. Journal of Mechanical Design, 136(11), p.111102.

- Fayemi, P.-E.; Wanieck, K.; Zollfrank, C.; Maranzana, N.; Aoussat, A. Biomimetics: Process, tools and practice. Bioinspir. Biomim. 2017, 12, 011002.

- Velivela, P.T. and Zhao, Y.F., 2022. A comparative analysis of the state-of-the-art methods for multifunctional bio-inspired design and an introduction to domain integrated design (DID). Designs, 6(6), p.120. [CrossRef]

- Lenau, T.A.; Metze, A.-L.; Hesselberg, T. Paradigms for biologically inspired design. In Proceedings of the Bioinspiration, Biomimetics, and Bioreplication VIII, Denver, CO, USA, 4–8 March 2018; p. 1059302.

- Design Spiral. Available online: https://biomimicry.org/biomimicry-design-spiral/ (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Helms, M.; Vattam, S.S.; Goel, A.K. Biologically inspired design: Process and products. Des. Stud. 2009, 30, 606–622. [CrossRef]

- Fayemi, P.-E.; Maranzana, N.; Aoussat, A.; Bersano, G. Bio-inspired design characterisation and its links with problem solving tools. In Proceedings of the DS 77: Proceedings of the DESIGN 2014 13th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 19–22 May 2014; pp. 173–182.

- Lenau, T.A. Do biomimetic students think outside the box? In Proceedings of the DS 87-4 Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 17) Vol 4: Design Methods and Tools, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 21–25 August 2017; pp. 543–552.

- 2: ISO/TC266 2015 Biomimetics—Terminology, Concepts and Methodology (Berlin: Beuth) ISO 18458, 2015.

- Goel AK, Vattam S, Wiltgen B and HelmsM2014 Information processing theories of biologically inspired design Biologically Inspired Design (Berlin: Springer) pp 127–52.

- Lindemann U and Gramann J 2004 Engineering design using biological principles DS 32: Proc. DESIGN 2004, The 8th Int. Design Conf. (Dubrovnik, Croatia).

- 2005; 24. Chakrabarti A, Sarkar P, Leelavathamma B and Nataraju B 2005 A functional representation for aiding biomimetic and artificial inspiration of new ideas AIEEDAM19 113–32.

- Bogatyrev NR and Vincent J F 2008 Microfluidic actuation in living organisms: a biomimetic catalogue Proc. 1st European Conf. on Microfluidics (Bologna) p 175.

- Lenau TA 2009 Biomimetics as a design methodology-possibilities and challenges DS 58-5: Proc. ICED 09, The 17th Int. Conf. on Engineering Vol 5: Design Design Methods and Tools (pt. 1) (Palo Alto, CA, USA, 24–27 August 2009).

- Helms M, Vattam S S and Goel AK2009 Biologically inspired design: process and products Des. Stud. 30 606–22.

- Nagel JK, Nagel R L, Stone R B and McAdams DA 2010a Function based, biologically inspired concept generation Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 24 521–35.

- Sartori, J., Pal, U. and Chakrabarti, A., 2010. A methodology for supporting “transfer” in biomimetic design. AI EDAM, 24(4), pp.483-506.

- Cheong H, Chiu I, Shu L, Stone R and McAdams D 2011 Biologically meaningful keywords for functional terms of the functional basis J. Mech. Des. 133 021007.

- Baumeister D, Tocke R, Dwyer J and Ritter S 2013 Biomimicry resource handbook: a seed bank of best practices Biomimicry 3.

- Badarnah, L.; Kadri, U. A methodology for the generation of biomimetic design concepts. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2015, 58, 120–133. [CrossRef]

- Biomimicry Institute AskNature—Innovation Inspired by Nature. Available online: https://asknature.org/ (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Vattam, S.S.; Wiltgen, B.; Helms, M.E.; Goel, A.K.; Yen, J. DANE: Fostering Creativity in and through Biologically Inspired Design. In Design Creativity 2010; Springer: London, UK, 2011; pp. 115–122.

- Vattam, S.S.; Goel, A.K. Foraging for Inspiration: Understanding and Supporting the Online Information Seeking Practices of Biologically Inspired Designers. In Proceedings of the ASME 2011 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 28–31 August 2011; pp. 177–186.

- Vandevenne, D.; Verhaegen, P.-A.; Dewulf, S.; Duflou, J.R. SEABIRD: Scalable search for systematic biologically inspired design. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. AIEDAM 2016, 30, 78–95. [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.H. A natural-language approach to biomimetic design. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. AIEDAM 2010, 24, 507–519. [CrossRef]

- Kruiper, R.; Vincent, J.F.V.; Chen-Burger, J.; Desmulliez, M.P.Y.; Konstas, I. A Scientific Information Extraction Dataset for Nature Inspired Engineering. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.07753.

- Vincent, J.F.V.; Cavallucci, D. Development of an ontology of biomimetics based on altshuller’s matrix. In International TRIZ Future Conference; IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 541, pp. 14–25.

- Keshwani, S.; Lenau, T.A.; Ahmed-Kristensen, S.; Chakrabarti, A. Comparing novelty of designs from biological-inspiration with those from brainstorming. J. Eng. Des. 2017, 28, 654–680. [CrossRef]

- Grae, E.; Maranzana, N.; Aoussat, A. Engineers’ and Biologists’ Roles during Biomimetic Design Processes, Towards a Methodological Symbiosis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design, ICED, Delft, The Netherlands, 5–8 August 2019; Volume 1, pp. 319–328.

- Graeff, E., Maranzana, N. and Aoussat, A., 2021. A shared framework of reference, a first step toward Engineers’ and Biologists’ Synergic reasoning in biomimetic design teams. Journal of Mechanical Design, 143(4), p.041402.

- Graeff E., Letard, A., Raskin, K., Maranzana, N. and Aoussat, A., 2021. Biomimetics from practical feedback to an interdisciplinary process. Research in Engineering Design, 32, pp.349-375. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, J.K., Schmidt, L. and Born, W., 2015, August. Fostering diverse analogical transfer in bio-inspired design. In International design engineering technical conferences and computers and information in engineering conference (Vol. 57106, p. V003T04A028). American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- Nagel, J.K., Schmidt, L. and Born, W., 2018. Establishing analogy categories for bio-inspired design. Designs, 2(4), p.47. [CrossRef]

- Mak, T.W.; Shu, L.H. Abstraction of biological analogies for design. CIRP Ann. 2004, 531, 117–120. [CrossRef]

- Weidner, B.V., Nagel, J. and Weber, H.J., 2018. Facilitation method for the translation of biological systems to technical design solutions. International Journal of Design Creativity and Innovation, 6(3-4), pp.211-234. [CrossRef]

- Nagel JKS, Nagel RL, Stone RB (2011) Abstracting biology for engineering design. Int J Des Eng 4:23. https ://doi.org/10.1504/ ijde.2011.04140 7.

- Gero JS (1990) Design prototypes: a knowledge representation schema for design. AI Mag 11:26. https ://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v11i4.854.

- Bhasin D, McAdams DA (2018) The characterization of biological organization, abstraction, and novelty in biomimetic design. Designs 2:54. https ://doi.org/10.3390/desig ns204 0054.

- Wanieck, K., Hamann, L., Bartz, M., Uttich, E., Hollermann, M., Drack, M. and Beismann, H., 2022. Biomimetics Linked to Classical Product Development: An Interdisciplinary Endeavor to Develop a Technical Standard. Biomimetics, 7(2), p.36. [CrossRef]

- Wanieck, K. and Beismann, H., 2021. Perception and role of standards in the world of biomimetics. Bioinspired, Biomimetic and Nanobiomaterials, 10(1), pp.8-15. [CrossRef]

- VDI 6220 Blatt 2:2023-07, Biomimetics - Biomimetic design methodology - Products and processes, July 2023.

- Walter, L., Isenmann, R. and Moehrle, M.G., 2011. Bionics in patents–semantic-based analysis for the exploitation of bionic principles in patents. Procedia Engineering, 9, pp.620-632. [CrossRef]

- Roth, R.R., 1983. The foundation of bionics. Perspectives in biology and medicine, 26(2), pp.229-242.

- Bionics Institute https://www.bionicsinstitute.org/ (accessed 23/10/2024).

- Russo, D., Fayemi, P.E., Spreafico, M. and Bersano, G., 2018. Design entity recognition for bio-inspired design supervised state of the art. In Automated Invention for Smart Industries: 18th International TRIZ Future Conference, TFC 2018, Strasbourg, France, October 29–31, 2018, Proceedings (pp. 3-13). Springer International Publishing.

- Nachtigall, W. (2002). Bionik: Grundlagen und Beispiele fu¨r Ingenieure und Naturwissenschaftler. Berlin: Springer.

- Várady , T., Martin, R.R. and Cox, J., 1997. Reverse engineering of geometric models—an introduction. Computer-aided design, 29(4), pp.255-268. [CrossRef]

- Várady T. and Martin R., “Reverse engineering”. In: Handbook of Computer Aided Geometric Design (2002), pp. 651–681.

- Várady, T., Facello, M.A. and Terék, Z., 2007. Automatic extraction of surface structures in digital shape reconstruction. Computer-Aided Design, 39(5), pp.379-388. [CrossRef]

- Várady, T., 2008. Automatic procedures to create CAD models from measured data. Computer-Aided Design and Applications, 5(5), pp.577-588. [CrossRef]

- Speck, O., Speck, D., Horn, R., Gantner, J. and Sedlbauer, K.P., 2017. Biomimetic bio-inspired biomorph sustainable? An attempt to classify and clarify biology-derived technical developments. Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 12(1), p.011004. [CrossRef]

- Möller, M., Speck, T. and Speck, O., 2024. Sustainability assessments inspired by biological concepts. Technology in Society, p.102630. [CrossRef]

- Harthikote Nagaraja, V., 2019. Motion capture and musculoskeletal simulation tools to measure prosthetic arm functionality (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford).

- Hill, B., 2005. Goal Setting Through Contradiction Analysis in the Bionics-Oriented Construction Process. Creativity and Innovation Management, 14(1), pp.59-65. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I., Várady, T. and Salvi, P., 2015. Applying geometric constraints for perfecting CAD models in reverse engineering. Graphical Models, 82, pp.44-57. [CrossRef]

- Kovács, I., 2021. Curves and surfaces determined by geometric constraints (Doctoral dissertation, Budapest University of Technology and Economics (Hungary)).

- Wainwright PC. 1988. Morphology and ecology: the functional basis of feeding constraints in Caribbean labrid fishes. Ecology 69:635–45. [CrossRef]

- Helfman Cohen, Y., Reich, Y. and Greenberg, S., 2014. Biomimetics: structure–function patterns approach. Journal of Mechanical Design, 136(11), p.111108. cited 66. [CrossRef]

- Snell-Rood, E.C. and Smirnoff, D., 2023. Biology for biomimetics I: function as an interdisciplinary bridge in bio-inspired design. Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 18(5), p.052001. [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, K., Jones, S.B., Davies, M. and West, N., 2020. Development of a chewing robot with built-in humanoid jaws to simulate mastication to quantify robotic agents release from chewing gums compared to human participants. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 68(2), pp.492-504. [CrossRef]

- Speck, O. and Speck, T., 2021. Biomimetics and education in Europe: Challenges, opportunities, and variety. Biomimetics, 6(3), p.49. [CrossRef]

- Pahl G., Beitz W., Feldhusen J., Grote K-H., Engineering Design - A Systematic Approach 3rd English edition, Springer 2007. 2nd English edition, Springer 1996. 1st English edition published by The Design Council, London, UK (ISBN 085072239X).

- Chandrasegaran, S.K., Ramani, K., Sriram, R.D., Horváth, I., Bernard, A., Harik, R.F. and Gao, W., 2013. The evolution, challenges, and future of knowledge representation in product design systems. Computer-aided design, 45(2), pp.204-228. [CrossRef]

- Owen R., Horváth I., Towards product-related knowledge asset warehousing in enterprises. In: Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on tools and methods of competitive engineering, TMCE 2002; 2002. p. 155–70.

- Erden, M.S., Komoto, H., Beek, T.J.V., D’Amelio, V., Echavarria, E., & Tomiyama, T. (2008). A review of functional modeling: approaches and applications. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing 22, 147–169. [CrossRef]

- Hirtz, J., Stone, R.B., McAdams, D.A., Szykman, S. and Wood, K.L., 2002. A functional basis for engineering design: reconciling and evolving previous efforts. Research in Engineering Design, 13, pp.65-82. [CrossRef]

- Eisenbart, B., Gericke, K. and Blessing, L., 2011. A framework for comparing design modelling approaches across disciplines. In DS 68-2: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 11), Impacting Society through Engineering Design, Vol. 2: Design Theory and Research Methodology, Lyngby/Copenhagen, Denmark, 15.-19.08. 2011 (pp. 344-355).

- Stone, R.B. and Wood, K.L., 1999, September. Development of a functional basis for design. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (Vol. 19739, pp. 261-275). American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- Miles, L. (1961). Techniques of Value Analysis and Engineering. New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Dieter, G. (1991). Engineering Design: A Materials and Processing Approach. New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Cutherell, D. (1996). Product architecture. In The PDMA Handbook of New Product Development (Rosenau Jr., M., Ed.). New York: Wiley.

- Otto, K.N., & Wood, K.L. (2001). Product Design: Techniques in Reverse Engineering and New Product Development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice–Hall.

- Ulrich, K.T., & Eppinger, S.D. (2004). Product Design and Development. Boston: McGraw–Hill/Irwin.

- Ullman, D.G. (2009). The Mechanical Design Process, 4th ed. New York: McGraw–Hill.

- Sharma, S. and Sarkar, P., 2024. A framework to describe biological entities for bioinspiration. International Journal on Interactive Design and Manufacturing (IJIDeM), 18(8), pp.5681-5700.

- Nagel, J.K., Nagel, R.L., Stone, R.B. and McAdams, D.A., 2010. Function-based, biologically inspired concept generation. Ai Edam, 24(4), pp.521-535. [CrossRef]

- Eisenbart, B., Gericke, K. and Blessing, L., 2013. An analysis of functional modeling approaches across disciplines. Ai Edam, 27(3), pp.281-289. [CrossRef]

- Eisenbart, B., Gericke, K., Blessing, L.T. and McAloone, T.C., 2017. A DSM-based framework for integrated function modelling: concept, application and evaluation. Research in Engineering Design, 28, pp.25-51. [CrossRef]

- Nagel RL, Midha PA, Tinsley A, Stone RB, McAdams D, Shu L (2008) Exploring the use of functional models in biomimetic conceptual design. J Mech Des 130(12):2–13.

- Nagel, J.K., Stone, R.B. and McAdams, D.A., 2014. Function-based biologically inspired design. Biologically Inspired Design: Computational Methods and Tools, pp.95-125.

- Fayemi, P.E., Maranzana, N., Aoussat, A. and Bersano, G., 2015. Assessment of the biomimetic toolset—Design Spiral methodology analysis. In ICoRD’15–Research into Design Across Boundaries Volume 2: Creativity, Sustainability, DfX, Enabling Technologies, Management and Applications (pp. 27-38). Springer India.

- Deldin, J.M. and Schuknecht, M., 2013. The AskNature database: enabling solutions in biomimetic design. In Biologically inspired design: Computational methods and tools (pp. 17-27). London: Springer London.

- Biomimicry Institute (2024) Biomimicry Taxonomy. https://toolbox.biomimicry.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/AN_Biomimicry_Taxonomy.pdf (accessed 23/10/2024).

- Kozaki, K. and Mizoguchi, R., 2014, October. An Ontology Explorer for Biomimetics Database. In ISWC (Posters & Demos) (pp. 469-472).

- Kozaki K (2024) http://biomimetics.hozo.jp/ontology_db.html (accessed 23/10/2024).

- Vandevenne D, Verhaegen PA, Dewulf S and Duflou JR (2012) Automatically populating the biomimicry taxonomy for scalable systematic biologically-inspired design. In Proceedings of ASME 2012 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, August 12–15, Chicago, Illinois, USA. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, New York, NY, USA, pp. 383–391.

- Vincent, J., 2023. Biomimetics with Trade-Offs. Biomimetics, 8(2), p.265. [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.F., 2014. An ontology of biomimetics. Biologically inspired design: Computational methods and tools, pp.269-285.

- Nagel, J.K., Stone, R.B. and McAdams, D.A., 2010, January. An engineering-to-biology thesaurus for engineering design. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (Vol. 44137, pp. 117-128).

- Nagel, J.K., 2014. A thesaurus for bioinspired engineering design. Biologically Inspired Design: Computational Methods and Tools, pp.63-94.

- Belz, A., Terrile, R.J., Zapatero, F., Kawas, M. and Giga, A., 2019. Mapping the “valley of death”: Managing selection and technology advancement in NASA's Small Business Innovation Research program. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(5), pp.1476-1485.

- Chirazi, J., Wanieck, K., Fayemi, P.E., Zollfrank, C. and Jacobs, S., 2019. What do we learn from good practices of biologically inspired design in innovation?. Applied Sciences, 9(4), p.650. [CrossRef]

- Ellwood, P., Williams, C. and Egan, J., 2022. Crossing the valley of death: Five underlying innovation processes. Technovation, 109, p.102162. [CrossRef]

- Kampers, L.F., Asin-Garcia, E., Schaap, P.J., Wagemakers, A. and dos Santos, V.A.M., 2022. Navigating the Valley of Death: perceptions of industry and academia on production platforms and opportunities in biotechnology. EFB Bioeconomy Journal, 2, p.100033. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, J.K. and Stone, R.B., 2011, January. A systematic approach to biologically-inspired engineering design. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (Vol. 54860, pp. 153-164).

- Nagel, J.K., Nagel, R.L. and Stone, R.B., 2011. Abstracting biology for engineering design. International Journal of Design Engineering, 4(1), pp.23-40.

- Voland, G. (2004). Engineering by Design. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice–Hall.

- Henderson, K., 1998. On line and on paper: Visual representations, visual culture, and computer graphics in design engineering. MIT press. [CrossRef]

- Chrysikou, E. G., & Weisberg, R. W. (2005). Following the wrong footsteps: Fixation effects of pictorial examples in a design problem solving task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory & Cognition, 31, 1134–1148. [CrossRef]

- Linsey, J., Murphy, J., Markman, A., Wood, K. L., & Kortoglu, T. (2006). Representing Analogies: Increasing the Probability of Innovation. Proceedings of the ASME International Design Theory and Method Conference, Philadelphia, PA.

- Linsey, J., Tseng, I., Fu, K., Cagan, J., Wood, K., & Schunn, C. (2010). A study of design fixation, its mitigation and perception in engineering design faculty. Journal of Mechanical Design, 132, 1041003-1–12. [CrossRef]

- Chikofsky E, Cross J (1990) Reverse Engineering and Design Recovery: A Taxonomy. IEEE Software 7(1):13–17.

- Anwer, N. and Mathieu, L., 2016. From reverse engineering to shape engineering in mechanical design. CIRP Annals, 65(1), pp.165-168. [CrossRef]

- Raja, V. and Fernandes, K.J. (2007) Reverse Engineering: An Industrial Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media, London, UK.

- Petrovic, V., Vicente Haro Gonzalez, J., Jordá Ferrando, O., Delgado Gordillo, J., Ramón Blasco Puchades, J. and Portolés Griñan, L., 2011. Additive layered manufacturing: sectors of industrial application shown through case studies. International Journal of Production Research, 49(4), pp.1061-1079. [CrossRef]

- Marks, P. “Capturing a competitive edge through digital shape sampling & processing (DSSP)”. In: SME, blue book series (2005).

- Pieraccini, M., Guidi, G. and Atzeni, C., 2001. 3D digitizing of cultural heritage. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2(1), pp.63-70. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Shuman, L., Bidanda, B., Kelley, M., Sochats, K. and Balaban, C. (2008) Agent-based discrete event simulation modeling for disaster responses, in Proceedings of the 2008 Industrial Engineering Research Conference, pp. 1908–1913, Institute of Industrial Engineers, Norcross, GA.

- Bidanda, B., Motavalli, S. and Harding, K. (1991) Reverse engineering: An evaluation of prospective non-contact technologies and applications in manufacturing systems. International Journal of Computer Integrated Manufacturing, 4(3), 145–156. [CrossRef]

- Bidanda, B., Narayanan, V. and Billo, R. (1994) Reverse engineering and rapid prototyping, in Handbook of Design, Manufacturing and Automation, pp. 977–990, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

- Otto K, Wood K (1998) Product Evolution: A reverse Engineering and Redesign Methodology. Research in Product Development 10(4):226–243.

- Geng, Z., Sabbaghi, A. and Bidanda, B., 2023. Reconstructing original design: Process planning for reverse engineering. IISE Transactions, 55(5), pp.509-522. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, D.-J. (2011) Three-dimensional surface reconstruction of human bone using a b-spline based interpolation approach. Computer-Aided Design, 43(8), 934–947.

- VDI 5620. 2017-03. Reverse engineering of geometrical data.

- Cha, B.K., Lee, J.Y., Jost-Brinkmann, P.-G. and Yoshida, N. (2007) Analysis of tooth movement in extraction cases using three-dimensional reverse engineering technology. The European Journal of Orthodontics, 29(4), 325–331. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., & Scott, P. (2020). Advanced Metrology: Freeform Surfaces. (1st ed.) Academic Press Inc. [CrossRef]

- Theologou, P., Pratikakis, I. and Theoharis, T., 2015. A comprehensive overview of methodologies and performance evaluation frameworks in 3D mesh segmentation. Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 135, pp.49-82. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Z. and Bidanda, B. (2017) Review of reverse engineering systems current state of the art. Virtual and Physical Prototyping, 12(2), 161–172.

- Buonamici, F., Carfagni, M., Furferi, R., Governi, L., Lapini, A. and Volpe, Y., 2018. Reverse engineering modeling methods and tools: a survey. Computer-Aided Design and Applications, 15(3), pp.443-464. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.O. and Rosen, D., 2007, January. Systematic reverse engineering of biological systems. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (Vol. 48043, pp. 69-78).

- Yin, C.G. and Ma, Y.S., 2012. Parametric feature constraint modelling and mapping in product development. Advanced Engineering Informatics, 26(3), pp.539-552. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Z., and Ma Y., , A functional feature modelling method, Adv. Eng. Informatics. 33 (2017) 1–15,. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Z., and Ma Y., Explicit function-based design modelling methodology with features, J. Eng. Des. 28 (2017) 205–231,. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Zheng, Y., Yang, M., Leng, J., Cheng, Z., Xie, Y., Jiang, P. and Ma, Y., 2020. A survey of feature modelling methods: Historical evolution and new development. Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, 61, p.101851. [CrossRef]

- Ma YS, Tong T. Associative feature modelling for concurrent engineering integration. Computers in Industry 2003;51(1):51–71. [CrossRef]

- Chen G, Ma YS, Thimm G, Tang SH. Associations in a unified feature modelling scheme. Journal of Information Science in Engineering 2006;6(2):114–26.

- Mingqiang, Y., Kidiyo, K. and Joseph, R., 2008. A survey of shape feature extraction techniques. Pattern recognition, 15(7), pp.43-90.

- Di Angelo, L. and Di Stefano, P., 2015. Geometric segmentation of 3D scanned surfaces. Computer-Aided Design, 62, pp.44-56.

- Yang, X., Han, X., Li, Q., He, L., Pang, M. and Jia, C., 2020. Developing a semantic-driven hybrid segmentation method for point clouds of 3D shapes. IEEE Access, 8, pp.40861-40880. [CrossRef]

- Honti, R., Erdélyi, J. and Kopáčik, A., 2022. Semi-automated segmentation of geometric shapes from point clouds. Remote Sensing, 14(18), p.4591. [CrossRef]

- Besl P.J. and Jain R.C., (1986) Invariant surface characteristics for 3-d object recognition in range images. Comput. Vision Graphics Image Proc., 33:33–80.

- Besl P.J. and Jain R.C., (1988) "Segmentation through variable-order surface fitting," in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 167-192.

- Berger, M., Tagliasacchi, A., Seversky, L.M., Alliez, P., Levine, J.A., Sharf, A. and Silva, C.T., 2014. State of the art in surface reconstruction from point clouds. In 35th Annual Conference of the European Association for Computer Graphics, Eurographics 2014-State of the Art Reports. The Eurographics Association.

- Berger, M., Tagliasacchi, A., Seversky, L.M., Alliez, P., Guennebaud, G., Levine, J.A., Sharf, A. and Silva, C.T., 2017, January. A survey of surface reconstruction from point clouds. In Computer graphics forum (Vol. 36, No. 1, pp. 301-329). [CrossRef]

- Hylander, W.L., 2006. Functional anatomy and biomechanics of the masticatory apparatus. Temporomandibular disorders: an evidenced approach to diagnosis and treatment. New York: Quintessence Pub Co, pp.3-34.

- Artificial Human Skull (Separates Into 3 Parts), https://www.adam-rouilly.co.uk/product/po10-artificial-human-skull-separates-into-3-parts/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Skeleton of the Hand With Base of Forearm (Flexible Mounting) - 29-parts https://www.adam-rouilly.co.uk/product/po45-1-skeleton-of-the-hand-with-base-of-forearm-flexible-mounting/ (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Renishaw plc (2003) Cyclone - the complete scanning system for reverse engineering. Renishaw plc.

- https://www.hand-therapy.co.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/baht_anatomy_handout.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Mostafa, E., Imonugo, O. and Varacallo, M., 2023. Anatomy, shoulder and upper limb, humerus. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Gray, H. and Lewis W.H., Anatomy of the Human Body. 1918: Lea & Febiger.

- Santello, M., Bianchi, M., Gabiccini, M., Ricciardi, E., Salvietti, G., Prattichizzo, D., Ernst, M., Moscatelli, A., Jörntell, H., Kappers, A.M. and Kyriakopoulos, K., 2016. Hand synergies: Integration of robotics and neuroscience for understanding the control of biological and artificial hands. Physics of life reviews, 17, pp.1-23. [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, P., Gupta, A. and SKM, V., 2023. Comparison of synergy patterns between the right and left hand while performing postures and object grasps. Scientific Reports, 13(1), p.20290. [CrossRef]

- Jarque-Bou, N.J., Scano, A., Atzori, M. and Müller, H., 2019. Kinematic synergies of hand grasps: a comprehensive study on a large publicly available dataset. Journal of neuro-engineering and rehabilitation, 16, pp.1-14. [CrossRef]

- Ficuciello, F., 2018. Synergy-based control of underactuated anthropomorphic hands. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 15(2), pp.1144-1152. doi:10.1109/tii.2018.2841043.

- Kragten, G.A. and Herder, J.L., 2010. The ability of underactuated hands to grasp and hold objects. Mechanism and Machine Theory, 45(3), pp.408-425. [CrossRef]

- Gustus, A., Stillfried, G., Visser, J., Jörntell, H. and van der Smagt, P., 2012. Human hand modelling: kinematics, dynamics, applications. Biological cybernetics, 106, pp.741-755. [CrossRef]

- Thakur, P.H., Bastian, A.J. and Hsiao, S.S., 2008. Multidigit movement synergies of the human hand in an unconstrained haptic exploration task. Journal of Neuroscience, 28(6), pp.1271-1281. [CrossRef]

- Khademi, M., Mousavi Hondori, H., McKenzie, A., Dodakian, L., Lopes, C.V. and Cramer, S.C., 2014. Free-hand interaction with leap motion controller for stroke rehabilitation. In CHI'14 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1663-1668).

- Cobos, S., Ferre, M. and Aracil, R., 2010, October. Simplified human hand models based on grasping analysis. In 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (pp. 610-615). IEEE.

- Cobos, S., Ferre, M., Ángel Sánchez-Urán, M., Ortego, J. and Aracil, R., 2010. Human hand descriptions and gesture recognition for object manipulation. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering, 13(3), pp.305-317. [CrossRef]

- Vignais, N. and Marin, F., 2014. Analysis of the musculoskeletal system of the hand and forearm during a cylinder grasping task. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics, 44(4), pp.535-543. [CrossRef]

- Uhlrich, S.D., Uchida, T.K., Lee, M.R. and Delp, S.L., 2023. Ten steps to becoming a musculoskeletal simulation expert: a half-century of progress and outlook for the future. Journal of biomechanics, 154, p.111623. [CrossRef]

- Al Nazer, R., Klodowski, A., Rantalainen, T., Heinonen, A., Sievänen, H. and Mikkola, A., 2011. A full body musculoskeletal model based on flexible multibody simulation approach utilised in bone strain analysis during human locomotion. Computer methods in biomechanics and biomedical engineering, 14(06), pp.573-579. [CrossRef]

- McFarland, D.C., Binder-Markey, B.I., Nichols, J.A., Wohlman, S.J., De Bruin, M. and Murray, W.M., 2022. A musculoskeletal model of the hand and wrist capable of simulating functional tasks. IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, 70(5), pp.1424-1435. [CrossRef]

- Jadelis, C.T., Ellis, B.J., Kamper, D.G. and Saul, K.R., 2023. Cosimulation of the index finger extensor apparatus with finite element and musculoskeletal models. Journal of Biomechanics, 157, p.111725. [CrossRef]

- McErlain-Naylor, S.A., King, M.A. and Felton, P.J., 2021. A review of forward-dynamics simulation models for predicting optimal technique in maximal effort sporting movements. Applied Sciences, 11(4), p.1450. [CrossRef]

- Tsang, W., Singh, K. and Fiume, E., 2005, July. Helping hand: an anatomically accurate inverse dynamics solution for unconstrained hand motion. In Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics symposium on Computer animation (pp. 319-328).

- Komatsu I, et al. 2018 Anatomy and Biomechanics of the Thumb Carpometacarpal Joint, Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics, Volume 28, Issue 1. [CrossRef]

- M. R. Cutkosky, "On grasp choice, grasp models, and the design of hands for manufacturing tasks," in IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 269-279, June 1989. [CrossRef]

- Pylios, T. 2010 A New Metacarpophalangeal Joint Replacement Prosthesis, Biomedical Engineering Research Group School of Mechanical Engineering, University of Birmingham.

- de Carvalho, RM, et al. 2012 Analysis of the reliability and reproducibility of goniometry compared to hand photogrammetry. Acta Ortop Bras.

- Kapandji AI. Clinical evaluation of the thumb’s opposition. Journal of Hand Therapy. 1992 Apr 1;5(2):102–6. [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, K., Hyde, R.A. and Gao, J., 2007. Prototyping a robotic dental testing simulator. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine, 221(4), pp.385-396.

- H. C. Lundeen and C.H.Gibbs, Advances in Occlusion (Dental Practical Handbooks). Boston, MA, USA: J. Wright-PSG, 1982.

- J. Koolstra and T. Van Eijden, “Biomechanical analysis of jaw-closing movements,” J. Dent. Res., vol. 74, pp. 1564–1570, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Majstorovic, V., Trajanovic, M., Vitkovic, N. and Stojkovic, M., 2013. Reverse engineering of human bones by using method of anatomical features. Cirp Annals, 62(1), pp.167-170. [CrossRef]

- Ralphs, J.R. and M. Benjamin, The joint capsule: structure, composition, ageing and disease. Journal of Anatomy, 1994. 184(Pt 3): p. 503-509.

- Ficuciello, F., Palli, G., Melchiorri, C. and Siciliano, B., 2014. Postural synergies of the UB Hand IV for human-like grasping. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 62(4), pp.515-527. [CrossRef]

- Controzzi, M., Cipriani, C., Jehenne, B., Donati, M. and Carrozza, M.C., 2010, August. Bio-inspired mechanical design of a tendon-driven dexterous prosthetic hand. In 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology (pp. 499-502). IEEE.

- Fugl-Meyer, A.R., et al., The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method for evaluation of physical performance. Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine, 1974. 7(1): p. 13-31. [CrossRef]

- Gladstone DJ, Danells CJ, Black SE. The Fugl-Meyer Assessment of Motor Recovery after Stroke: A Critical Review of Its Measurement Properties. Neurorehabil Neural Repair [Internet]. 2002 Sep 1;16(3):232–40. [CrossRef]

- Kapandji A: Clinical test of apposition and counter-apposition of the thumb. Annales de Chirurgie de laMain Organe Officiel des Soc de Chirurgie de la Main 1986, 5(1):67–73.

- Leamy DJ, Kocijan J, Domijan K, Duffin J, Roche RA, Commins SR, et al. An exploration of EEG features during recovery following stroke - Implications for BCI-mediated neurorehabilitation therapy. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2014;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Feix T, Romero J, Schmiedmayer HB, Dollar AM, Kragic D. The GRASP Taxonomy of Human Grasp Types. IEEE Trans Hum Mach Syst. 2016 Feb 1;46(1):66–77. [CrossRef]

- Bretz, K, et al. 2010 Force measurement of hand and fingers. Biomechanica Hungarica. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, AB, et al. 1970 The strength of the hand Bull Prosthet Res.

- Wu, JZ, et al.2018 An evaluation of the contact forces on the fingers when squeezing a spherical rehabilitation ball. Biomed Mater Eng ;29(5):629-639. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Biomechanics in ergonomics. 1999: CRC Press.

- Ahmad Imran Ibrahim. Designing and Prototyping an Anthropomorphic Robotic Hand for Rehabilitation Application. PhD thesis, University of Bristol; 2016.

- Patil, M.S., Patil, S.B. and Acharya, A.B., 2008. Palatine rugae and their significance in clinical dentistry: a review of the literature. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 139(11), pp.1471-1478.

- Simonite T. Robot jaws to get a human bite. NewScienceTech website 2008 January 3. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn13133-robot-jaws-to-get-a-human-bite/.

- Ireland, A.J., McNamara, C., Clover, M.J., House, K., Wenger, N., Barbour, M.E., Alemzadeh, K., Zhang, L. and Sandy, J.R., 2008. 3D surface imaging in dentistry–what we are looking at. British dental journal, 205(7), pp.387-392.

- Alemzadeh, K. and Burgess, S., 2005. A team-based CAD project utilising the latest CAD technique and web-based technologies. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education, 33(4), pp.294-318. [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, K., 2006. A team-based CAM project utilising the latest CAD/CAM and web-based technologies in the concurrent engineering environment. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education, 34(1), pp.48-70. [CrossRef]

- Alemzadeh, K., Wishart, C.L. and Booker, J.D., 2007. The integrated application of microcontrollers in the team-based ‘Design and Make’ Project. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education, 35(3), pp.226-247.

- Hatchuel, A. and Weil, B. C-K design theory: An advanced formulation. Res. Eng. Des. 2009, 19, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Hatchuel, A. and Weil, B. A new approach of innovative design: An introduction to CK theory. In Proceedings of the ICED 03, the 14th International Conference on Engineering Design, Stockholm, Sweden, 19–21 August 2003; pp. 109–110. 17.

- Salgueiredo, C.F., 2013, June. Modeling biological inspiration for innovative design. In i3 conference.

- Freitas Salgueiredo, C. and Hatchuel, A., 2014. Modeling biologically inspired design with the CK design theory. In DS 77: Proceedings of the DESIGN 2014 13th International Design Conference (pp. 23-32).

- Salgueiredo, C.F. and Hatchuel, A., 2016. Beyond analogy: A model of bioinspiration for creative design. Ai Edam, 30(2), pp.159-170. [CrossRef]

- Nagel, J.K. and Pidaparti, R.M., 2016, August. Significance, prevalence and implications for bio-inspired design courses in the undergraduate engineering curriculum. In International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (Vol. 50138, p. V003T04A009). American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- Pidaparti, R.M. and Nagel, J.K., 2018, March. CK Theory based bio-inspired projects in a sophomore design course. In ASEE Southeastern Section Conference (pp. 1-6).

- Pidaparti, R.M., Graceraj, P.P., Nagel, J. and Rose, C.S., 2020. Engineering Design Innovation through CK theory based templates. Journal of STEM Education: Innovations and Research, 21(1).

- Graceraj P, P., Nagel, J.K., Rose, C.S. and Pidaparti, R.M., 2019. Investigation of CK theory based approach for innovative solutions in bioinspired design. Designs, 3(3), p.39.

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).