Submitted:

21 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

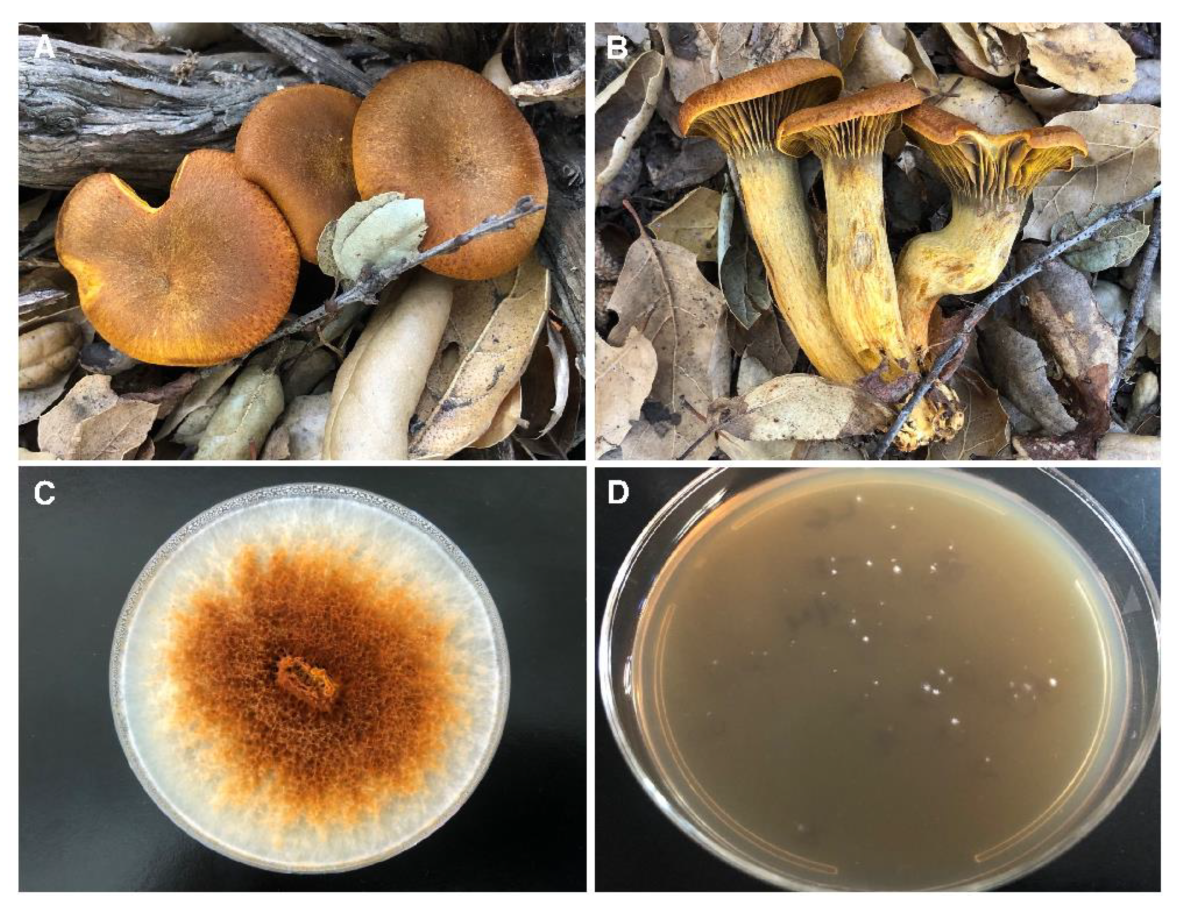

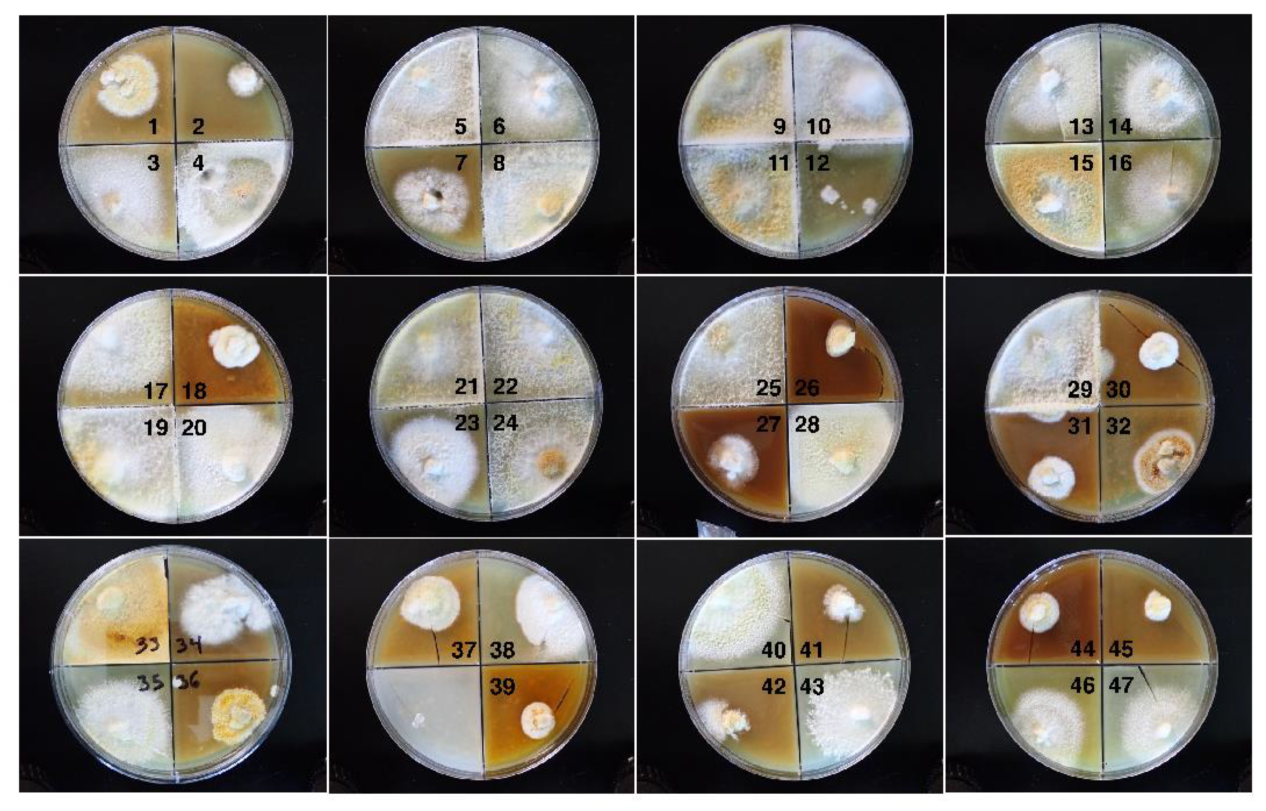

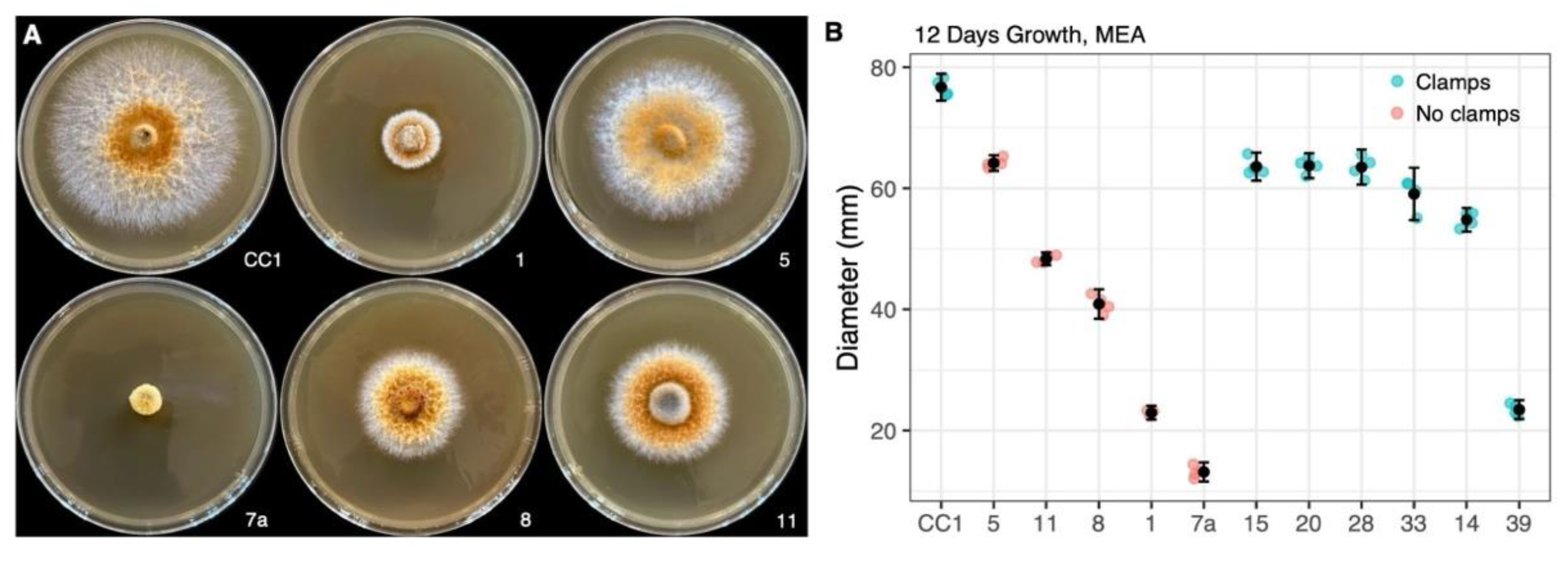

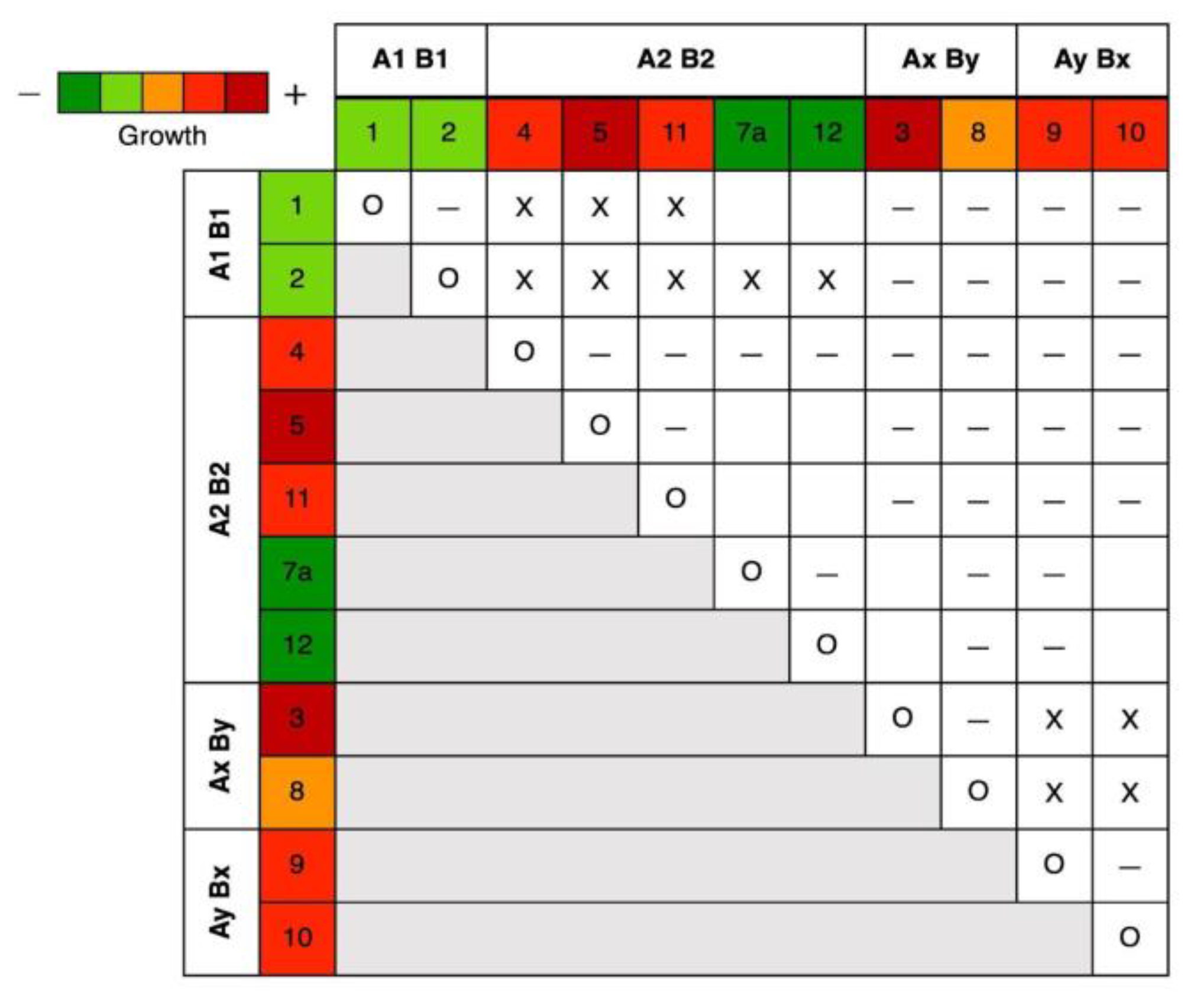

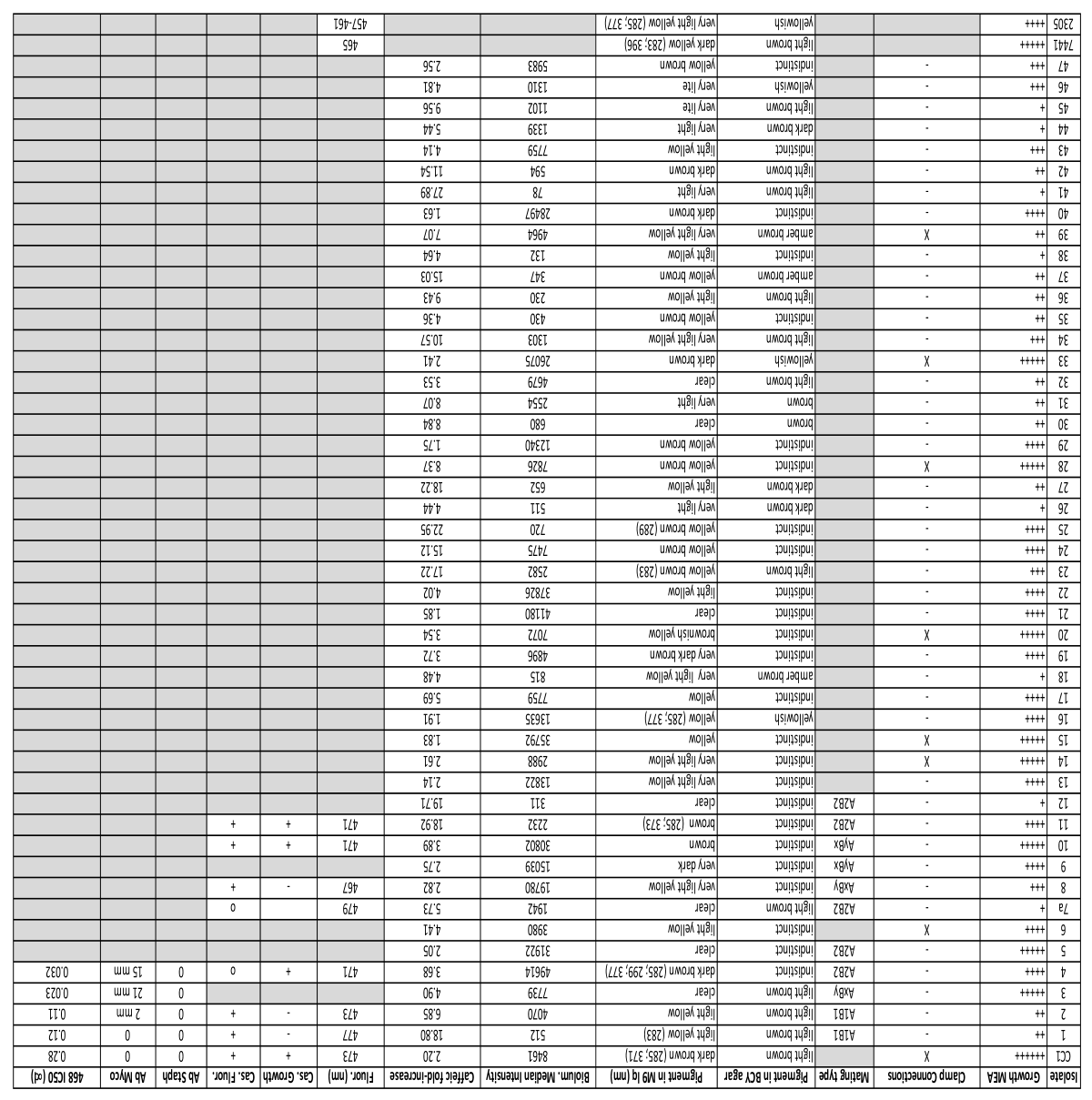

The fungal genus Omphalotus is noted for its bioluminescence and the production of biologically active secondary metabolites. We isolated 47 fungal strains of Omphalotus olivascens germinated from spores of a single mushroom. We first noted a high degree of variation in the outward appearances in radial growth and pigmentation among the cultures. Radial growth rates fell into at least five distinct categories, with only slower growing isolates obtained compared with the parental dikaryon. Scanning UV-vis spectroscopy of liquid-grown cultures showed variation in pigmentation in both the absorption intensity and peak absorption wavelengths, indicating that some isolates vary from the parental strain in both pigment concentration and composition. Bioluminescence intensity was observed to have isolates with both greater and lesser intensities, while the increased emission in response to caffeic acid was inversely proportional to the unstimulated output. Under UV illumination the media of parental strain was observed to be brightly fluorescent, which was not due to the pigment, while the isolates also varied from greater to lesser intensity and in their peak emission. At least three separate fluorescent bands were observed by gel electrophoresis from one of the cultures, while only one was observed in others. Fluorescence intensity varied significantly in response to casamino acids. None of a subset of the cultures produced an antibiotic effective against Staphylococcus aureus, and only the haploids, but not the parental heterokaryon, produced an antibiotic consistent with illudin M effective against Mycobacterium smegmatis. This same subset all produced an anticancer agent that was highly potent against MDA-MB-468 breast cancer tumor cells. We interpret these variations in haploids as significant in altering Omphalotus physiology and its production of secondary metabolites, which may in turn alter their ecology and life cycle, and could be further applied to studying fungal physiologies and facilitate linking them to their genetic underpinnings.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Cultures

2.2. Growth Assessment

2.2.1. Radial Growth

2.2.2. Mating Type Determinations

2.3. Pigmentation

2.4. Bioluminescence

2.5. Fluorescence

2.5.1. Fluorescence in Minimal Media

2.5.2. Growth and Fluorescence with Casamino Acids

2.6. Antibiological Activity

2.6.1. Antibacterial Activity

2.6.2. Antitumor Cell Activity

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fungal Cultures

3.2. Growth

3.2.1. Variation in Radial Growth

3.2.2. Mating Types

3.3. Variation in Pigmentation

3.4. Bioluminescence

3.4.1. Variation in Luminosity

3.4.2. Response to Caffeic Acid

3.5. Variation in Fluorescence

3.5.1. Fluorescence Variation in Minimal Media

3.5.2. Fluorescence and Growth Variation in Response to Casamino Acids

3.6. Antibiological Activity

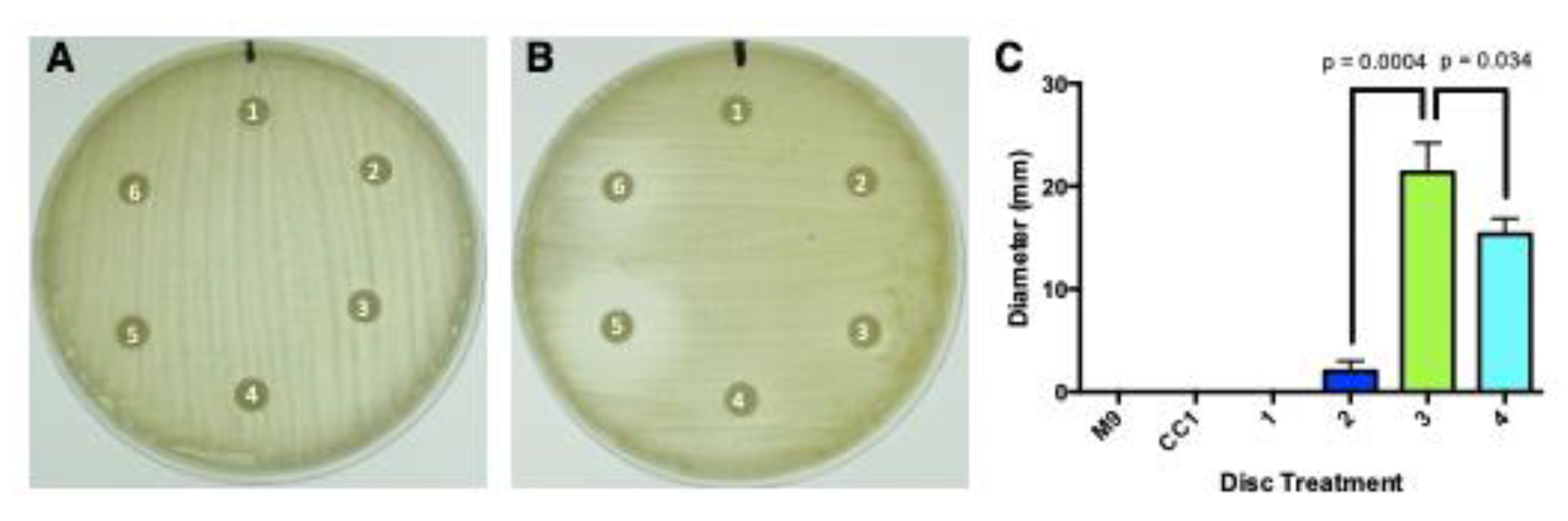

3.6.1. Antibacterial Activity

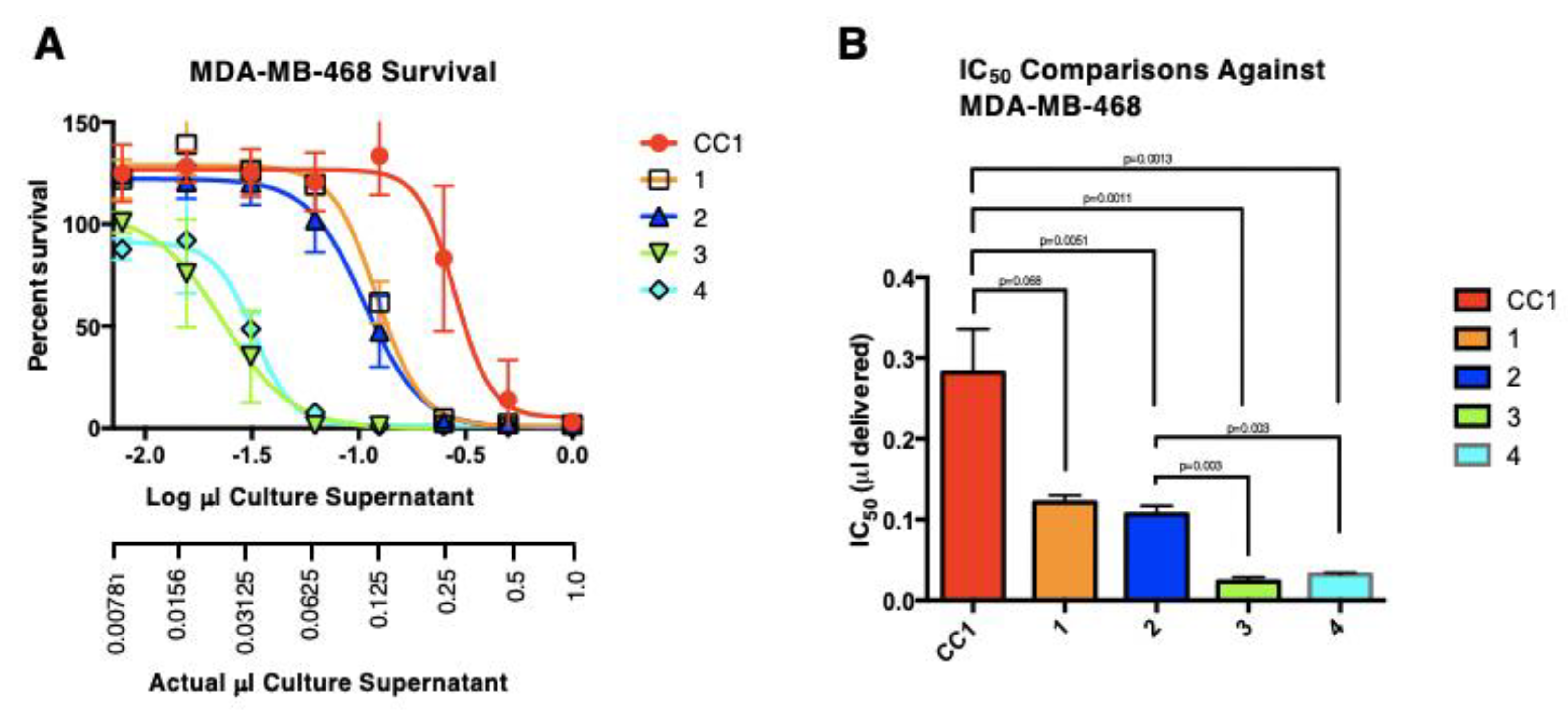

3.6.2. Antitumor Cell Activity

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ke, H.-M.; Lu, M.R.; Chang, C.-C.; Hsiao, C.; Ou, J.-H.; Taneyama, Y.; Tsai, I.J. Evolution and Diversity of Bioluminescent Fungi. In The Mycota; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2023; pp. 275–294. ISBN 9783031291982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, M.J.; Shim, D.; Ryoo, R. De Novo Genome Assembly of the Bioluminescent Mushroom Omphalotus Guepiniiformis Reveals an Omphalotus-Specific Lineage of the Luciferase Gene Block. Genomics 2022, 114, 110514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purtov, K.V.; Petunin, A.I.; Rodicheva, E.K.; Bondar, V.S.; Gitelson, J.I. Components of the Luminescent System of the Luminous Fungus Neonothopanus Nambi. Dokl. Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 461, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purtov, K.V.; Petushkov, V.N.; Baranov, M.S.; Mineev, K.S.; Rodionova, N.S.; Kaskova, Z.M.; Tsarkova, A.S.; Petunin, A.I.; Bondar, V.S.; Rodicheva, E.K.; et al. The Chemical Basis of Fungal Bioluminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed Engl. 2015, 54, 8124–8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oba, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Martins, G.N.R.; Carvalho, R.P.; Pereira, T.A.; Waldenmaier, H.E.; Kanie, S.; Naito, M.; Oliveira, A.G.; Dörr, F.A.; et al. Identification of Hispidin as a Bioluminescent Active Compound and Its Recycling Biosynthesis in the Luminous Fungal Fruiting Body. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlobay, A.A.; Sarkisyan, K.S.; Mokrushina, Y.A.; Marcet-Houben, M.; Serebrovskaya, E.O.; Markina, N.M.; Gonzalez Somermeyer, L.; Gorokhovatsky, A.Y.; Vvedensky, A.; Purtov, K.V.; et al. Genetically Encodable Bioluminescent System from Fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 12728–12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A, Ichihara; H, Shirahama; T, Matsumoto Dihydroiludin S, A New Constitutent from Lampteromyes Japonicus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1969, 45, 3965–3968.

- Endo, M.; Kajiwara, M.; Nakanishi, K. Fluorescent Constituents and Cultivation of Lampteromyces Japonicus. Journal of the Chemical Society D: Chemical Communications 1970, 0, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, M.; Uyakul, D.; Goto, T. Lampteromyces Bioluminescence--1. Identification of Riboflavin as the Light Emitter in the Mushroom L. Japonicus. J. Biolumin. Chemilumin. 1987, 1, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M, Isobe; D, Uyakul; T, Goto. Lampteromyces Bioluminescence - 2 Lampteroflavin, A Light Emitter in the Luminous Mushroom L. Japonicus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 1169–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, W.D.; Hastings, J.W.; Sonnenfeld, V.; Coulombre, J. The Requirement of Riboflavin Phosphate for Bacterial Luminescence. Science 1953, 118, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Kishi, Y.; Shimomura, O. Panal: A Possible Precursor of Fungal Luciferin. Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 1597–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, W.J.; Hervey, A.; Davidson, R.W.; Ma, R.; Robbins, W.C. A Survey of Some Wood-Destroying and Other Fungi for Antibacterial Activity. Bull. Torrey Bot. Club 1945, 72, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, W.J.; Kavanagh, F.; Hervey, A. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: I. Pleurotus Griseus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1947, 33, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, W.J.; Kavanagh, F.; Hervey, A. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: II. Polyporus Biformis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1947, 33, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchel, M.; Hervey, A.; Kavanagh, F.; Polatnick, J.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: III. Coprinus Similis and Lentinus Degener: III. Coprinus Similis and Lentinus Degener. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1948, 34, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, F.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: IV. Marasmius Conigenus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1949, 35, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, F.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: V. Poria Corticola, Poria Tenuis and an Unidentified Basidiomycete. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1950, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, F.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: VI. Agrocybe Dura. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1950, 36, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchel, M.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes. VII. Clitocybe Illudens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1950, 36, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, F.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: VIII. Pleurotus Multilus (Fr.) Sacc. and Pleurotus Passeckerianus Pilat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1951, 37, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh, F.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: IX. Drosophila Subtarata. (Batsch Ex Fr.) Quel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1952, 38, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anchel, M.; Hervey, A.; Robbins, W.J. Antibiotic Substances from Basidiomycetes: X. Fomes Juniperinus Schrenk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1952, 38, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Tada, M.; Yamada, Y.; Ohashi, M.; Komatsu, N.; Terakawa, H. Isolation of Lampterol, an Antiumour Substance from Lampteromyces Japonicus. Nature 1963, 197, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMorris, T.C.; Anchel, M. The Structures of the Basidiomycete Metabolites Illudin S and Illudin M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Yamada, Y.; Bhacca, N.S.; Nakanishi, K.; Ohashi, M. STRUCTURE AND REACTIONS OF ILLUDIN-S (LAMPTEROL). Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 1964, 12, 853–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Shirahama, H.; Ichihara, A.; Fukuoka, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Mori, Y.; Watanabe, M. Structure of Lampterol (Illudin S). Tetrahedron 1965, 21, 2671–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Ohashi, M.; Tada, M.; Yamada, Y. Illudin S (Lampterol). Tetrahedron 1965, 21, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelner, M.J.; McMorris, T.C.; Beck, W.T.; Zamora, J.M.; Taetle, R. Preclinical Evaluation of Illudins as Anticancer Agents. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 3186–3189. [Google Scholar]

- Kelner, M.J.; McMorris, T.C.; Taetle, R. Preclinical Evaluation of Illudins as Anticancer Agents: Basis for Selective Cytotoxicity. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1990, 82, 1562–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelner, M.J.; McMorris, T.C.; Estes, L.; Starr, R.J.; Rutherford, M.; Montoya, M.; Samson, K.M.; Taetle, R. Efficacy of Acylfulvene Illudin Analogues against a Metastatic Lung Carcinoma MV522 Xenograft Nonresponsive to Traditional Anticancer Agents: Retention of Activity against Various Mdr Phenotypes and Unusual Cytotoxicity against ERCC2 and ERCC3 DNA Helicase-Deficient Cells. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 4936–4940. [Google Scholar]

- Kelner, M.J.; McMorris, T.C.; Montoya, M.A.; Estes, L.; Uglik, S.F.; Rutherford, M.; Samson, K.M.; Bagnell, R.D.; Taetle, R. Characterization of Acylfulvene Histiospecific Toxicity in Human Tumor Cell Lines. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1998, 41, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schobert, R.; Biersack, B.; Knauer, S.; Ocker, M. Conjugates of the Fungal Cytotoxin Illudin M with Improved Tumour Specificity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 8592–8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaverra-Muñoz, L.; Briem, T.; Hüttel, S. Optimization of the Production Process for the Anticancer Lead Compound Illudin M: Improving Titers in Shake-Flasks. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaverra-Muñoz, L.; Hüttel, S. Optimization of the Production Process for the Anticancer Lead Compound Illudin M: Process Development in Stirred Tank Bioreactors. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaverra-Muñoz, L.; Briem, T.; Hüttel, S. Optimization of the Production Process for the Anticancer Lead Compound Illudin M: Downstream Processing. Microb. Cell Fact. 2022, 21, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.A.; Bakkeren, G.; Sun, S.; Hood, M.E.; Giraud, T. Fungal Sex: The Basidiomycota. In The Fungal Kingdom; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; pp. 147–175. ISBN 9781683670827. [Google Scholar]

- Fincham, J.R.S. Fungal Genetics. Encyclopedia of Life Sciences 2001.

- Idnurm, A.; Hood, M.E.; Johannesson, H.; Giraud, T. Contrasted Patterns in Mating-Type Chromosomes in Fungi: Hotspots versus Coldspots of Recombination. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2015, 29, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, R.H.; Hughes, K.W. Mating Systems in Omphalotus (Paxillaceae, Agaricales). Osterr. Bot. Z. 1998, 211, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E. Tetrapolar Fungal Mating Types: Sexes by the Thousands. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 18, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kües, U. From Two to Many: Multiple Mating Types in Basidiomycetes. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2015, 29, 126–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.L.; Bruhn, J.N.; Anderson, J.B. The Fungus Armillaria Bulbosa Is among the Largest and Oldest Living Organisms. Nature 1992, 356, 428–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peabody, R.B.; Peabody, D.C.; Sicard, K.M. A Genetic Mosaic in the Fruiting Stage of Armillaria Gallica. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000, 29, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selosse, M.A. Adding Pieces to Fungal Mosaics. New Phytol. 2001, 149, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, K.W.; Petersen, R.H.; Lodge, D.J.; Bergemann, S.E.; Baumgartner, K.; Tulloss, R.E.; Lickey, E.; Cifuentes, J. Evolutionary Consequences of Putative Intra-and Interspecific Hybridization in Agaric Fungi. Mycologia 2013, 105, 1577–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreeburg, S.; Nygren, K.; Aanen, D.K. Unholy Marriages and Eternal Triangles: How Competition in the Mushroom Life Cycle Can Lead to Genomic Conflict. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrrell, M.G.; Peabody, D.C.; Peabody, R.B.; James-Pederson, M.; Hirst, R.G.; Allan-Perkins, E.; Bickford, H.; Shafrir, A.; Doiron, R.J.; Churchill, A.C.; et al. Mosaic Fungal Individuals Have the Potential to Evolve within a Single Generation. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, R.; Solovyeva, I.; Rühl, M.; Thines, M.; Hennicke, F. Dikaryotic Fruiting Body Development in a Single Dikaryon of Agrocybe Aegerita and the Spectrum of Monokaryotic Fruiting Types in Its Monokaryotic Progeny. Mycol. Prog. 2016, 15, 947–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-W.; McKeon, M.C.; Elmore, H.; Hess, J.; Golan, J.; Gage, H.; Mao, W.; Harrow, L.; Gonçalves, S.C.; Hull, C.M.; et al. Invasive Californian Death Caps Develop Mushrooms Unisexually and Bisexually. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raper, J.R. Heterokaryosis and Sexuality in Fungi. Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1955, 17, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, A.; Hayakawa, N.; Saito, C.; Horimai, Y.; Misawa, H.; Yamanaka, T.; Fukuda, M. Physiological Variation among Tricholoma Matsutake Isolates Generated from Basidiospores Obtained from One Basidioma. Mycoscience 2019, 60, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado López, S.; Theelen, B.; Manserra, S.; Issak, T.Y.; Rytioja, J.; Mäkelä, M.R.; de Vries, R.P. Functional Diversity in Dichomitus Squalens Monokaryons. IMA Fungus 2017, 8, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peabody, R.B.; Peabody, D.C.; Tyrrell, M.G.; Edenburn-MacQueen, E.; Howdy, R.P.; Semelrath, K.M. Haploid Vegetative Mycelia of Armillaria Gallica Show Among-Cell-Line Variation for Growth and Phenotypic Plasticity. Mycologia 2005, 97, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, V.A. … Analysis of Luminescence Intensity of Single Spore Isolates from the Naturally Bioluminescent Fungus Armillaria Mellea (Agaricales, Physalacriaceae). 2018.

- Petersen, R.H.; Bermudes, D. Panellus Stypticus: Geographically Separated Interbreeding Populations. Mycologia 1992, 84, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, I.M.; Valdes, I.D.; Hayes, R.D.; LaButti, K.; Duffy, K.; Chovatia, M.; Johnson, J.; Ng, V.; Lugones, L.G.; Wösten, H.A.B.; et al. High Phenotypic and Genotypic Plasticity among Strains of the Mushroom-Forming Fungus Schizophyllum Commune. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2024, 173, 103913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauserud, H.; Schumacher, T. Outcrossing or Inbreeding: DNA Markers Provide Evidence for Type of Reproductive Mode in Phellinus Nigrolimitatus (Basidiomycota). Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, M. Pigments of Fungi (Macromycetes). Natural product reports 2003, 20, 615–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, C.; Vinithkumar, N.V.; Kirubagaran, R.; Venil, C.K.; Dufossé, L. Multifaceted Applications of Microbial Pigments: Current Knowledge, Challenges and Future Directions for Public Health Implications. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmair, M.; Pöder, R.; Huber, C.; Miller, O.K. Chemotaxonomical and Morphological Observations in the Genus Omphalotus (Omphalotaceae). Persoonia 2002, 17, 583–600. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.-J.; Kim, E.; Kim, M.-J.; Jang, Y.; Ryoo, R.; Ka, K.-H. Cloning and Expression Analysis of Bioluminescence Genes in Omphalotus Guepiniiformis Reveal Stress-Dependent Regulation of Bioluminescence. Mycobiology 2024, 52, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klostermeyer, D.; Knops, L.; Sindlinger, T.; Polborn, K.; Steglich, W. Novel Benzotropolone and 2H-Furo[3,2-b]Benzopyran-2-One Pigments FromTricholoma Aurantium (Agaricales). European J. Org. Chem. 2000, 2000, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreau, M.; Hector, A. Partitioning Selection and Complementarity in Biodiversity Experiments. Nature 2001, 412, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staake, M.D.; Kashinatham, A.; McMorris, T.C.; Estes, L.A.; Kelner, M.J. Hydroxyurea Derivatives of Irofulven with Improved Antitumor Efficacy. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 1836–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrzyn, G.T.; Quin, M.B.; Choudhary, S.; López-Gallego, F.; Schmidt-Dannert, C. Draft Genome of Omphalotus Olearius Provides a Predictive Framework for Sesquiterpenoid Natural Product Biosynthesis in Basidiomycota. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 772–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J.; Kim, S.W. Combinatorial Engineering of Hybrid Mevalonate Pathways in Escherichia Coli for Protoilludene Production. Microb. Cell Fact. 2016, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Gravekamp, C.; Bermudes, D.; Liu, K. Tumour-Targeting Bacteria Engineered to Fight Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, I.; Itterson, M.; Bermudes, D. Tumor-Targeted Salmonella Typhimurium Overexpressing Cytosine Deaminase: A Novel, Tumor-Selective Therapy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 542, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.-B.; Liu, W.; Lu, Y.-Y.; Bian, Y.-B.; Zhou, Y.; Kwan, H.S.; Cheung, M.K.; Xiao, Y. Constructing a New Integrated Genetic Linkage Map and Mapping Quantitative Trait Loci for Vegetative Mycelium Growth Rate in Lentinula Edodes. Fungal Biol. 2014, 118, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Xie, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y. A Resequencing-Based Ultradense Genetic Map of Hericium Erinaceus for Anchoring Genome Sequences and Identifying Genetic Loci Associated with Monokaryon Growth. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, S.; Maeda, K.; Sadamori, A.; Saitoh, S.; Tsuda, M.; Azuma, T.; Nagano, A.; Tomiyama, T.; Matsumoto, T. Construction of a Genetic Linkage Map and Detection of Quantitative Trait Locus for the Ergothioneine Content in Tamogitake Mushroom (Pleurotus Cornucopiae Var. Citrinopileatus). Mycoscience 2021, 62, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.-S.; Park, B.; van Peer, A.F.; Na, K.S.; Lee, S.H. Quantitative Trait Loci Analysis for Molecular Markers Linked to Agricultural Traits of Pleurotus Ostreatus. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0308832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, B.P.S.; Aanen, D.K. Nuclear Arms Races: Experimental Evolution for Mating Success in the Mushroom-Forming Fungus Schizophyllum Commune. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0209671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Song, X.; Xie, C.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, C.; Peng, Y. Landscape of Meiotic Crossovers in Hericium Erinaceus. Microbiological Research 2021, 245, 126692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).