1. Introduction

H9N2 avian influenza virus (AIV) is the most widespread low pathogenicity avian influenza virus (LPAIV) in the world. Inactivated vaccines are primarily used to prevent H9N2 AIV and have been applied in poultry in China for more than 30 years [

1]. Although the vaccines are effective in laboratories, they are more likely to be less effective in poultry in the field, leading to a constant H9N2 AIV transmission in the field and posing enormous economic loses and threats to public health [

2,

3,

4].

Maternal-derived antibodies (MDAs) are one of the main factors for the failure of H9N2 AIV vaccination in the field [

5]. MDAs are derived from maternal placental blood circulation and milk in humans and mammals, or from the yolk in avian species. On one hand, MDAs can protect offsprings from many infectious diseases at the beginning of their lives when they are vulnerable [

6,

7,

8]. On the other hand, MDAs hinder the immune responses to vaccinations against AIV [

5,

9], Newcastle disease virus (NDV) [

10,

11] in poultry and against measles virus in humans [

12,

13]. MDAs decrease with age, but the interference of vaccine immunization lead to a transient window of increased vulnerability to infections in young animals and infants. Given the convenience and cost-effectiveness of infant vaccination, it is crucial to develop new vaccines for young animals to overcome the interference MDAs and elicit strong immune responses.

The complement system plays an important role in immune responses. The complement C3d covalently attaches to microbial antigen, leading to markedly enhanced adaptive immune responses to that antigen [

14,

15,

16]. Several studies have shown that antigens attached to different copies (ranging from 1 to 6) of C3d can enhance immunogenicity and induce higher levels of both humoral and cellular immune responses compared to antigens without C3d [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. P28 (known as P29 in avian species), the minimum-binding domain of C3d, has also been shown to greatly enhance the antibody responses and Th2 immune responses when attached to antigens [

17,

22,

23,

24]. Recently, a booster dose of part P28-associaetd vaccine has been reported to overcome MDAs interference in pigs [

25]. However, it remains unclear whether P29 or multiple copies of P29 can overcome MDAs interference in avian species.

In the present study, we inserted different copies of P29 between the signal peptide and the head domain of a H9N2 AIV hemagglutinin (HA) proteins, and successfully rescued two modified H9N2 AIVs which could express HA with one or two copies of P29. The efficacy of the inactivated vaccines made with the two modified H9N2 AIVs were evaluated in the chickens with or without MDAs. MDAs are naturally inherited from dams have a high degree of variability in individual broilers, which makes it difficult to study MDAs-related research [

26]. Hyperimmune serum, which contains mostly IgY, has the similar isotype proportions to MDAs and can therefore be used to mimic the presence of MDAs in SPF chickens [

27,

28,

29]. Therefore, we used passively transferred antibodies (PTAs) as a model to mimic MDAs in one-day-old specific pathogen-free (SPF) chickens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Viruses

Specific pathogen free (SPF) chicken eggs were purchased from Beijing Merial Vital Laboratory Animal Technology and hatched in the laboratory of SHVRI. All chickens were tagged and housed in high containment chicken isolators (2200mm * 860mm * 1880 mm) and had full access to feed and water.

The low pathogenicity avian influenza virus (LPAIV) H9N2 (A/Chicken/Shanghai/H514/2017) was used in the SHVRI laboratory, abbreviated as H514. It was isolated and stored by the Research Team of the Etiologic Ecology of Animal Influenza and Avian Emerging Viral Disease, SHVRI. For experimental use, the H514 was propagated in 10-day-old SPF embryonated chicken eggs (ECEs) (Beijing Merial Vital Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd.). The modified viruses rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 were rescued in the SHVRI laboratory. Viral titers were calculated as median egg infectious doses (EID50).

2.2. Preparation of the Recombinant Plasmids

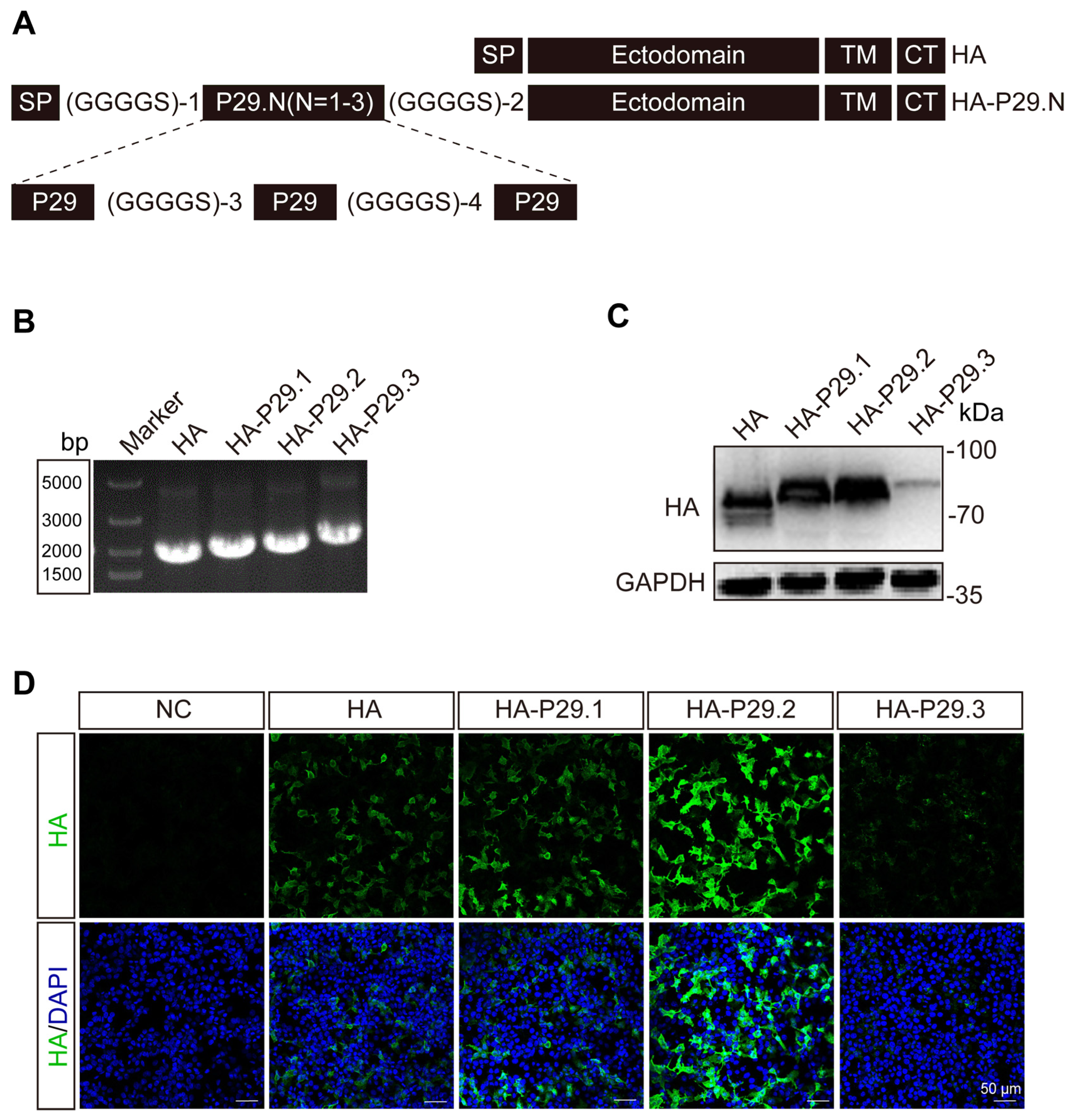

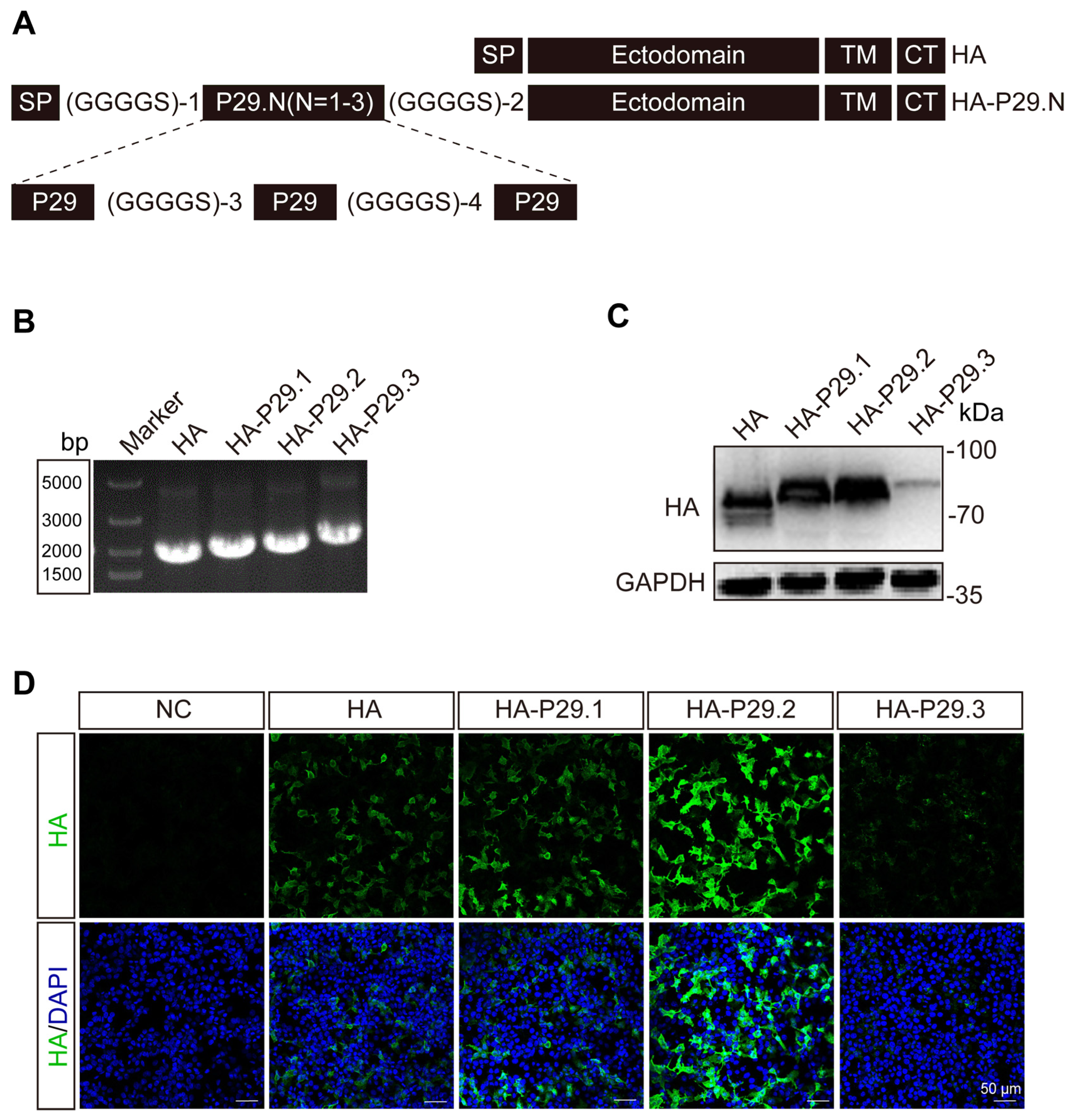

We initially obtained 3 copies of P29 (GenBank: EF632299.1) with 4 GGGGS flexible linkers via gene synthesis in GENEWIZ company (China), as shown in

Figure 1. All linkers used in this study were GGGGS but coded by different nucleotides (

Table 1).

The synthesized P29.3 served as PCR template. The 1, 2 and 3 copies of P29 were PCR-amplified by using specific primers (

Table 2). Next, 1, 2 and 3 copies of P29 were inserted between the 3′ end of the HA signal peptide and the nucleotides encoding the N-terminal domain of the HA1 ectodomain of H514 HA (

Figure 1A). The HA and recombinant HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) were cloned into pCAGGS plasmid by using specific primers (

Table 2), named pCAGGS-HA, pCAGGS-HA-P29.1, pCAGGS-HA-P29.2 and pCAGGS-HA-P29.3, respectively. The recombinant plasmids were amplified in DH5α and extracted by using Plasmids Maxi Kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

The eight gene segments of H514 were inserted into the vRNA-mRNA bidirectional transcription vector PHW2000. The gene segments of recombinant HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) were inserted into PHW2000. By using the eight-plasmid system [

30], we successfully rescued the H514 (named rH514) and the modified viruses (named rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2) by changing PHW2000-HA plasmid to PHW2000-HA-P29.1 or PHW2000- HA-P29.2 plasmid. However, we failed to rescue the rH514-P29.3 because of the low expression of HA-P29.3 proteins.

2.3. Western Blotting and Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay Analysis

We used western blotting (WB) and indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) to identify the expression of HA and HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) proteins. Eghorn male hepatoma (LMH) cells were seeded in 6-well plates (1 × 106/mL/well) and transfected with 1μg pCAGGS-HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) plasmid or inoculated with 100 μL 106EID50 rescued modified viruses. After 24 hours, the cells were harvested for WB and IFA.

For WB, the harvested cells were treated with SDS-PAGE loading buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were electroblotted on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes and then blocked with 5% skimmed milk dissolved in 0.5% phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 (PBS-T). The membrane was probed with anti-H514 HA monoclonal antibody (2F10) that was cloned and conserved in the laboratory of Etiologic Ecology of Animal Influenza and Avian Emerging Viral Disease, SHVRI and then anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Sigma, United States). The HA glycoprotein bands were visualized after adding ECL detection reagents. For IFA, the transfected or inoculated cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Paraformaldehyde (4%) was added to stabilize cells. The cells were permeabilized using 1% triton and blocked using 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The cells were then incubated with 2F10 and then with fluorescence conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Sigma, United States) at 37°C while protected from light. The results were observed by inverse microscopy (magnifications ×20).

2.4. Real-Time PCR Analysis

Real-time PCR analysis was conducted to quantify the mRNA levels of chicken interferons (chIFNs). Total cDNA was generated from total mRNA extracted from transfected cells using random 9 primers. Specific primers and probes were designed using the online tool available at the website (

https://eu.idtdna.com/site/account/login?returnurl=%2F PrimerQuest%2F) (

Table 2). Chicken β-actin served as a house-keeping gene. For each gene, the cycle threshold (Ct) values of different treatments at each time point were normalized to the respective endogenous control to get the ΔCt value. The difference in ΔCt value between the stimulated and control group was calculated (ΔΔCt). Quantification of mRNA levels from each resultant cDNA was expressed as fold changes (2-ΔΔCt) [

31].

2.5. Virus Growth

The growth characteristics of the rH514, rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 in eggs were examined. The rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 were inoculated into 9-11 days SPF eggs at 10

4 EID

50. Allantoic fluid was harvested at 12, 24, 48, 72 hour-post inoculation (p.i). The harvested viruses were measured by calculating the TCID50 as previously described [

32]. Briefly, a series of 10-fold dilutions of the samples were prepared in EMEM medium with 1 mg/mL penicillin & 1 mg/mL streptomycin, and then inoculated into the MDCK cells (37 °C, 5% CO2). After 48 hours of incubation, an HA assay using 0.5% chicken RBC in PBS was done to identify whether these samples contained the virus. The viral titers were calculated using the Reed & Muench method [

33].

2.6. The Inactivated Vaccine Formation

The rH514, rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 were inactivated with 1:2000 β- propiolactone (BPL) by constantly shaking for 16 h at 4℃. The residual β-propiolactone was evaporated at 37℃ for 2 h, and then 0.1 mL of the inactivated viruses were inoculated to three eggs and incubated for 48 h to confirm the loss of infectivity by an HA assay. The inactivated viruses were then mixed with water-in-oil Montanide VG71 (0.85g/cm3) adjuvant (SEPPIC, France) at a volume ratio of 3:7 according to the manufacturer’s instruction [

34].

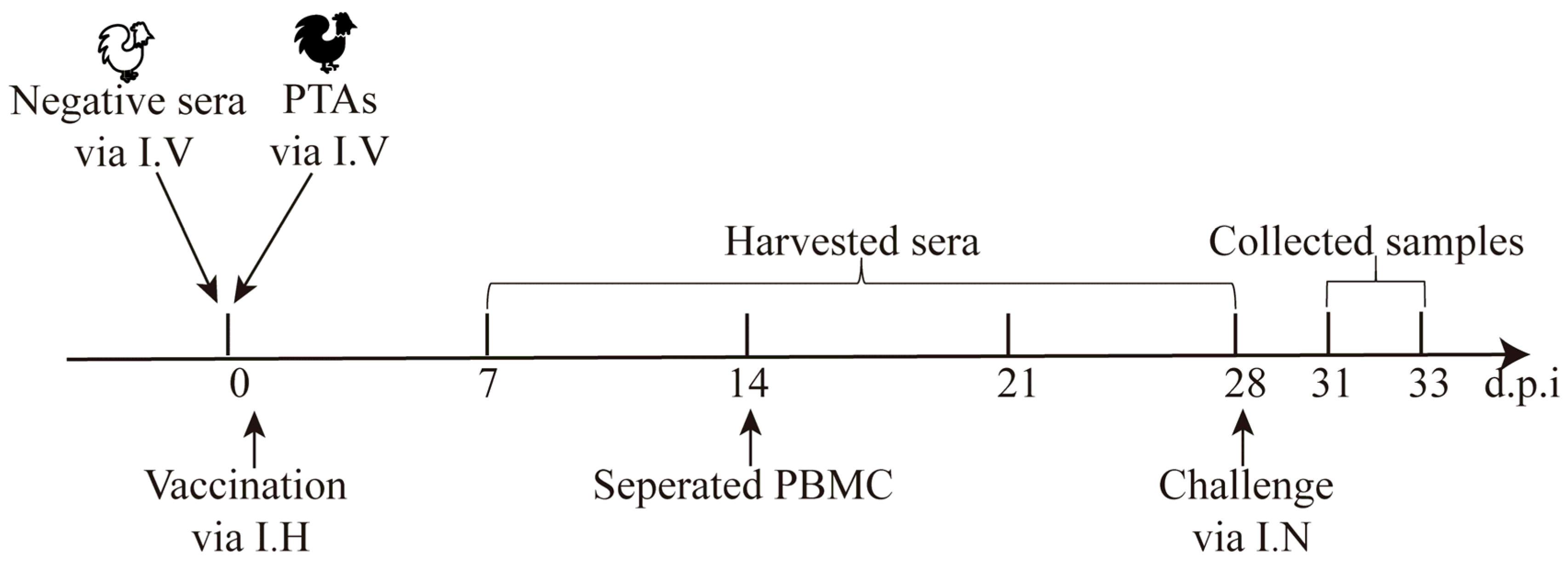

2.7. Passively Transferred Antibodies (PTAs) Model and Animal Experiment

The PTAs model was developed as previously described to mimic MDAs in one-day-old SPF chickens [

29]. Hyperimmune sera containing H514-specific antibodies was generated by subcutaneous injection of five-week-old SPF chickens with the inactivated vaccine made with H514 (0.5 mL/chicken) three times, with a two-week interval. A total of 0.3 mL of sera containing H514-specific antibodies (HI= 12 log

2) was transferred intravenously into one-day-old SPF chickens to achieve antibody titters of approximately 9 log

2, which was similar to the high titters of natural MDAs in one-day-old commercial chickens detected in poultry. Negative sera that did not contain H514-specific antibodies were used as a negative control.

One-day-old chickens, with or without PTAs (n=6/group), were inoculated subcutaneously in the neck with 0.1 mL of the inactivated vaccines made with rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2. Blood samples were collected weekly and sera were separated for detecting the chIFNs and rH514-specific antibodies. After 14 days of vaccination, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated and used for flow cytometry (FCM). Chickens with PTAs were intranasally challenged with 106 EID50 of H514 (0.1 mL/chicken) 28 days after vaccination. Oronasal and cloaca swabs were collected at 3 and 5 days post-challenge. At the end of the experiments, all animals were euthanized.

2.8. Flow Cytometry

PBMC were isolated by using chicken peripheral blood lymphocyte isolation reagent kit (P8740, Solarbio, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. A 15 μL volume of a panel of conjugated monoclonal antibody listed below, against chicken cell surface markers, was added to 100 μL of PBMC in a falcon tube and incubated in the dark for 15 min. All monoclonal antibodies were obtained from Invitrogen company, USA. Panel: anti-CD3-FITC (MA5-28696), anti-CD4-PE (MA5-28686) and anti-CD8-PE-Cyanine5 (MA5-28727). After washing with PBS and centrifugation for 5 min at 300 g, PBMC were analyzed on ACEA NovoCyte™ (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. Raw data was performed and analyzed by using FlowJo10.10.0 version.

2.9. ChIFNs ELISA Assay

The chIFNs (α, β and γ) in sera of vaccinated chickens were detected by using chIFN-α (SEKCN-0098), chIFN-β(SEKCN-0099) and chIFN-γ(SEKCN-0162) ELISA kits, respectively according to the manufacturer’s (Solarbio, China) instruction.

2.10. Hemagglutination Inhibition (HI) Assay

The antibodies were tested by HI assay as previously described [

35]. The BPL-inactivated H514 virus was used as a target antigen and diluted to standard HA units (8 HA in 50 μL). Serum samples were diluted in a serial 2-fold dilutions and 0.5% chicken red blood was used in the HI assay.

2.11. Detection of Virus from Oronasal and Cloaca Swabs

To calculate the viral shedding after challenging, oronasal and cloaca swabs were collected at 3 and 5 days post-challenge. Viral shedding was measured by calculating the TCID50 as mentioned above.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Significant differences were calculated using a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-hoc test using SPSS software (Windows v16.0). P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of the Recombinant Plasmids Expressing HAs Fused Different Copies of P29

To explore whether the P29-associated H9N2 AIV inactivated vaccine can overcome MDAs interference in chickens, 1, 2 or 3 copies of P29 (GenBank: EF632299.1) were inserted into the HA gene segment, located behind the signal peptide (SP) of H9N2 AIV (A/Chicken/Shanghai/H514/2017, abbreviated H514). The structure was illustrated in

Figure 1A. The gene segments of HA and HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) gene segments were cloned into the eukaryotic expression vector pCAGGS, named pCAGGS-HA and pCAGGS-HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3), respectively. The agarose and polyacrylamide gels demonstrated that the HA (1683 bp), HA-P29.1 (1800 bp) HA-P29.2 (1902 bp) and HA-P29.3 (2004 bp) gene segment was successfully integrated into the pCAGGS vector (

Figure 1B). The sequence analysis revealed that there were no mutation and the entire recombinant sequences were fully consistent with our expectations.

The pCAGGS-HA and pCAGGS-HA-P29.N plasmids were transfected into LMH cells. Western blotting (WB) results indicated that the proteins HA, HA-P29.1, HA-P29.2 and HA-P29.3 proteins were detected in the transfected cells. However, the expression of the HA-P29.3 proteins was weak (

Figure 1C). The indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) in transfected LMH cells also confirmed the expression of HA and HA-P29.N proteins. The IFA results showed that the HA-P29.2 proteins exhibit the highest fluorescence intensity, while the fluorescence intensity of the HA-P29.3 proteins was weak (

Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Development and identification of the recombinant HA-P29.N (N= 1, 2, 3) proteins. (A) The schematic of HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) gene segment. One, two or three copies of P29 were inserted into the HA gene segment behind the signal peptide (SP). The flexible linker GGGGS, coded by different nucleotides, was used to connect P29 with the other part of HA. (B) The gel electrophoresis of the HA and HA-P29.N. The HA and HA-P29.N were PCR-amplified using the same primers but different plasmids as templates. (C) WB analysis of the recombinant HA-P29.N proteins. LMH cells were transfected with pCAGGS-HA, pCAGGS-HA–P29.1, pCAGGS-HA–P29.2 or pCAGGS-HA–P29.3 plasmids. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were harvested to examine HA, HA-P29.1, HA-P29.2 and HA-P29.3 proteins by WB. (D) The IFA detection of the HA and HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) proteins. LMH cells were transfected with pCAGGS-HA, pCAGGS-HA–P29.1, pCAGGS-HA–P29.2, pCAGGS-HA–P29.3 or empty plasmid served as negative control. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were harvested to examine HA and HA-P29.N proteins by IFA.

Figure 1.

Development and identification of the recombinant HA-P29.N (N= 1, 2, 3) proteins. (A) The schematic of HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) gene segment. One, two or three copies of P29 were inserted into the HA gene segment behind the signal peptide (SP). The flexible linker GGGGS, coded by different nucleotides, was used to connect P29 with the other part of HA. (B) The gel electrophoresis of the HA and HA-P29.N. The HA and HA-P29.N were PCR-amplified using the same primers but different plasmids as templates. (C) WB analysis of the recombinant HA-P29.N proteins. LMH cells were transfected with pCAGGS-HA, pCAGGS-HA–P29.1, pCAGGS-HA–P29.2 or pCAGGS-HA–P29.3 plasmids. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were harvested to examine HA, HA-P29.1, HA-P29.2 and HA-P29.3 proteins by WB. (D) The IFA detection of the HA and HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) proteins. LMH cells were transfected with pCAGGS-HA, pCAGGS-HA–P29.1, pCAGGS-HA–P29.2, pCAGGS-HA–P29.3 or empty plasmid served as negative control. After 24 hours of transfection, cells were harvested to examine HA and HA-P29.N proteins by IFA.

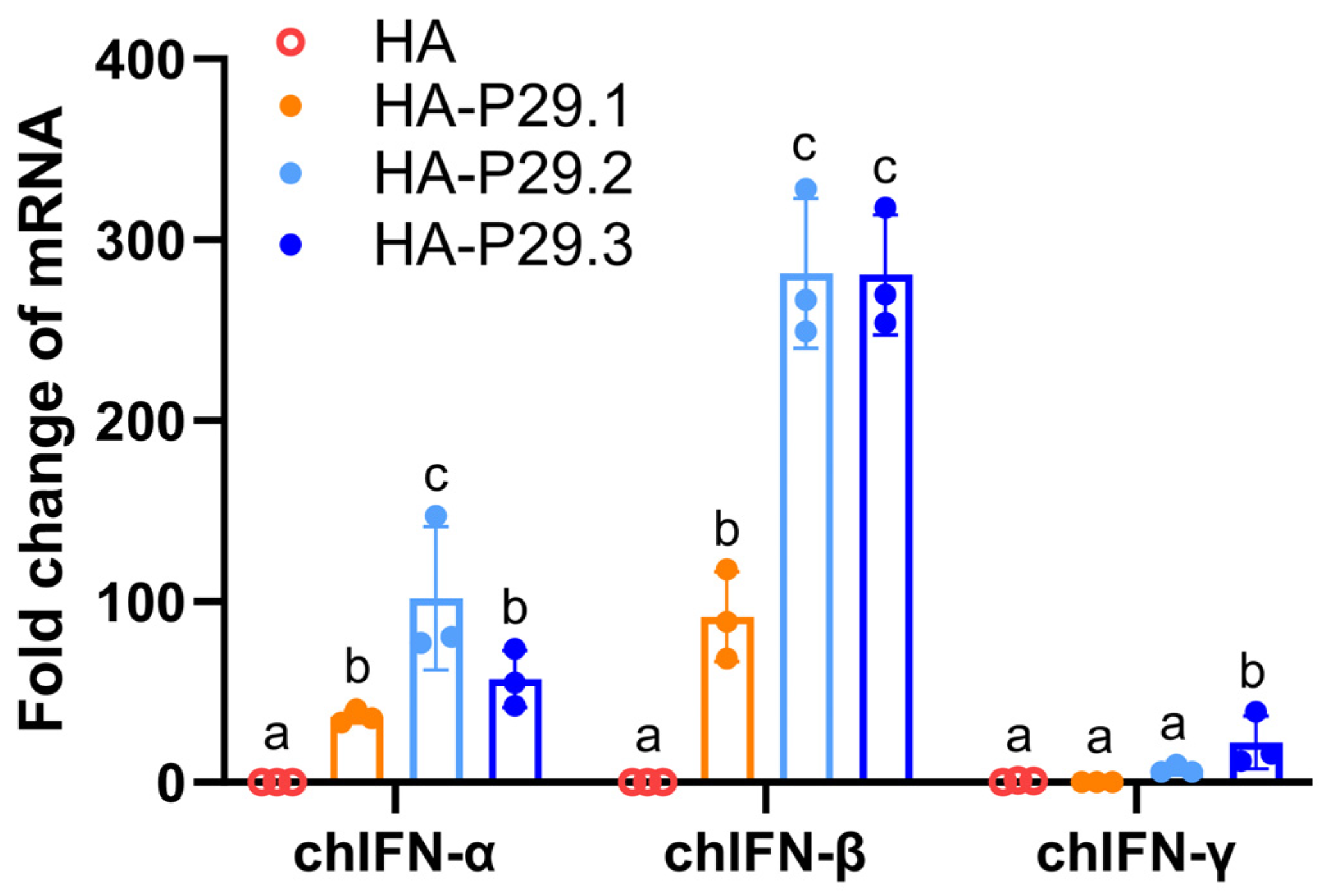

3.2. The HAs Fused Two Copies of P29 Promote the Expression of TypeⅠchIFNs

IFNs are known to be positive stimulators of immune responses by providing co-stimulatory signals to lymphocytes that recognize their antigen via B cell receptors or T cell receptors engagement [

36,

37]. Therefore, Real-time PCR was used to quantify the mRNA expression of chIFNs in LMH cells transfected with pCAGGS-HA and pCAGGS-HA-P29.N plasmids. The chIFN-α mRNA expression stimulated by pCAGGS-HA-P29.2 was significantly higher than that stimulated by the other plasmid and was 100 times higher than that stimulated by empty plasmids. The chIFN-β mRNA expression stimulated by both pCAGGS-HA-P29.2 and pCAGGS-HA-P29.3 was almost 300 time higher than that stimulated by empty plasmids and was significantly higher than in cells transfected with pCAGGS-HA or pCAGGS-HA-P29.1. The chIFN-γ mRNA expression in cells transfected with pCAGGS-HA-P29.3 was significantly higher than in the other transfected groups although the fold change was low (

Figure 2).

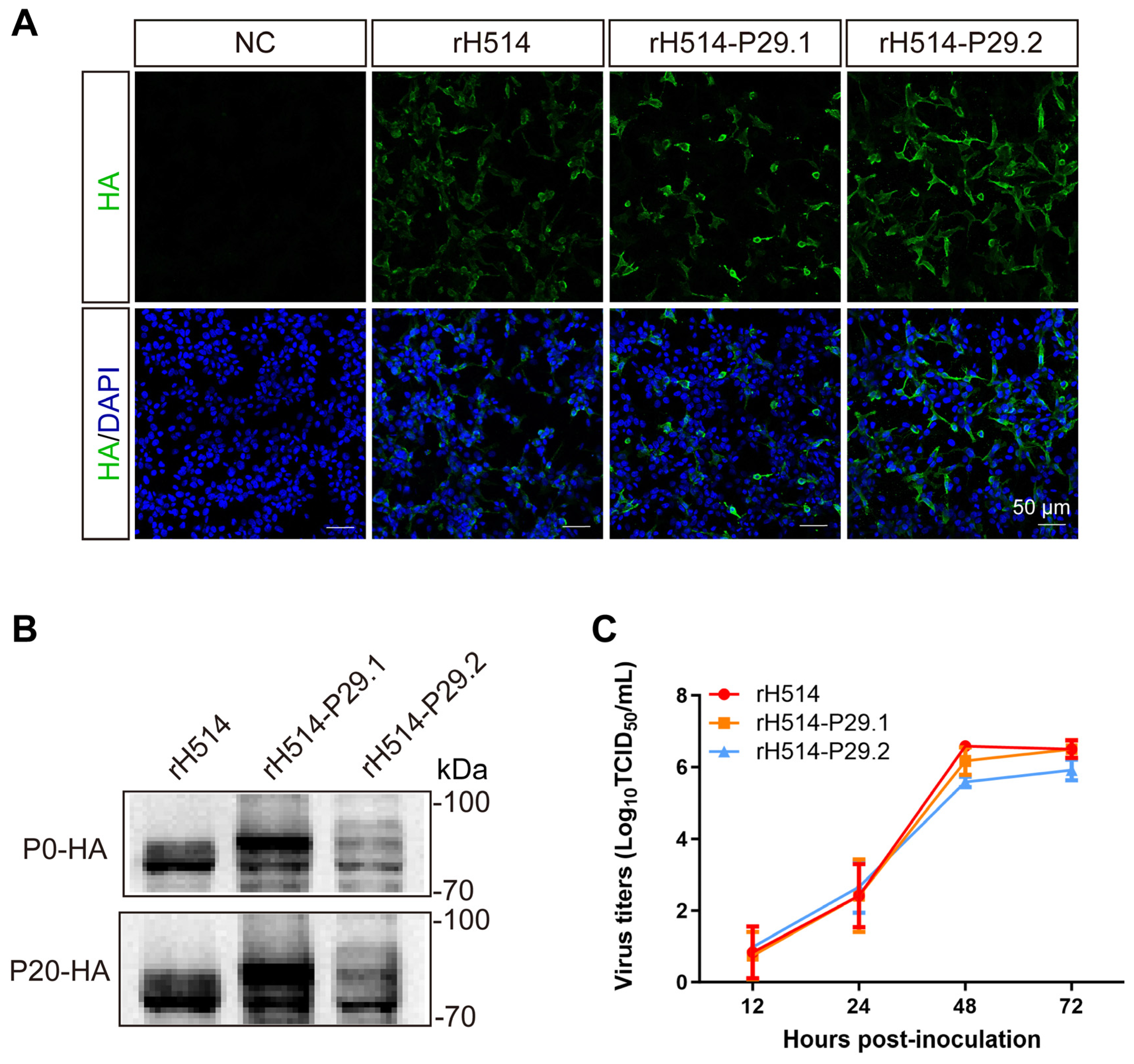

3.3. Generation of a Modified H9N2 Viruses Whose HA Fused Different Copies of P29

To develop a novel H9N2 AIV inactivated vaccine to overcome MDAs interference, we cloned the recombinant HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) gene segment into the vRNA-mRNA bidirectional transcription vector PHW200. Using the backbone of H514 and the eight-plasmid system [

30], we successfully rescued two modified H9N2 viruses, referred to as rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2, respectively. We failed to rescue the modified rH514-P29.3. This is probably because of the low expression of HA-P29.3 proteins identified by WB (

Figure 1C) and IFA (

Figure 1D). The parental H514 H9N2 virus was rescued as a control, abbreviated as rH514. The HA titers of the rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 was 2

10 and 2

9, respectively, which were similar to that of rH514 (210). The three rH514, rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 viruses have the same EID

50 titers (

Table 3). The results of IFA (

Figure 3A) and WB (

Figure 3B) showed that the rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 express HA-P29.1 and HA-P29.2 proteins efficiently, respectively.

To determine whether the P29.N insertion affect the replication properties of these modified H9N2 viruses, we analyzed the growth kinetics of rH514, rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 in embryo eggs. The results showed that the growth kinetics of rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 followed the same trend as those of rH514, with the highest viral titer reached at 48 h post-inoculation (

Figure 3C). Moreover, we assessed the genetic stability of rH514, rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 by continuously propagating them in 9 to 11 days-old embryo eggs. The allantoic fluid from these virus-infected eggs were harvested at every passage up to 20 generations. The expression of HA, HA-P29.1 and HA-P29.2 proteins were identified by WB. The results showed that the HA, HA-P29.1 and HA-P29.2 proteins could be stably expressed and inherited in rH514, rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 recombination viruses, respectively (

Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Identification and characterization of the modified rH514-P29.N (N=1, 2) and parental rH514 viruses in vitro. (A) The IFA detection of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N recombinant viruses. LMH cells were inoculated with the rH514, rH514-P29.1, rH514-P29.2 or PBS served as negative control. Cells were harvested to examine the HA and HA-P29.N proteins by IFA after 24 hours of inoculation. (B) WB analysis of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N recombinant viruses. The viruses were continuously propagated in 9 to 11 days-old eggs up to 20 passages (P20). The allantoic fluid from P0 and P20 virus-infected eggs were harvested and subjected to WB to examine HA and HA-P29.N proteins. (C) Growth curve of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N recombinant viruses. The 9 to 11 days-old eggs were inoculated with 104 EID50 of the rH514 or rH514-P29.N. The allantoic fluid from infected eggs were harvested at 12, 24, 48 and 72 h.p.i. and titrated in MDCK cells.

Figure 3.

Identification and characterization of the modified rH514-P29.N (N=1, 2) and parental rH514 viruses in vitro. (A) The IFA detection of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N recombinant viruses. LMH cells were inoculated with the rH514, rH514-P29.1, rH514-P29.2 or PBS served as negative control. Cells were harvested to examine the HA and HA-P29.N proteins by IFA after 24 hours of inoculation. (B) WB analysis of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N recombinant viruses. The viruses were continuously propagated in 9 to 11 days-old eggs up to 20 passages (P20). The allantoic fluid from P0 and P20 virus-infected eggs were harvested and subjected to WB to examine HA and HA-P29.N proteins. (C) Growth curve of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N recombinant viruses. The 9 to 11 days-old eggs were inoculated with 104 EID50 of the rH514 or rH514-P29.N. The allantoic fluid from infected eggs were harvested at 12, 24, 48 and 72 h.p.i. and titrated in MDCK cells.

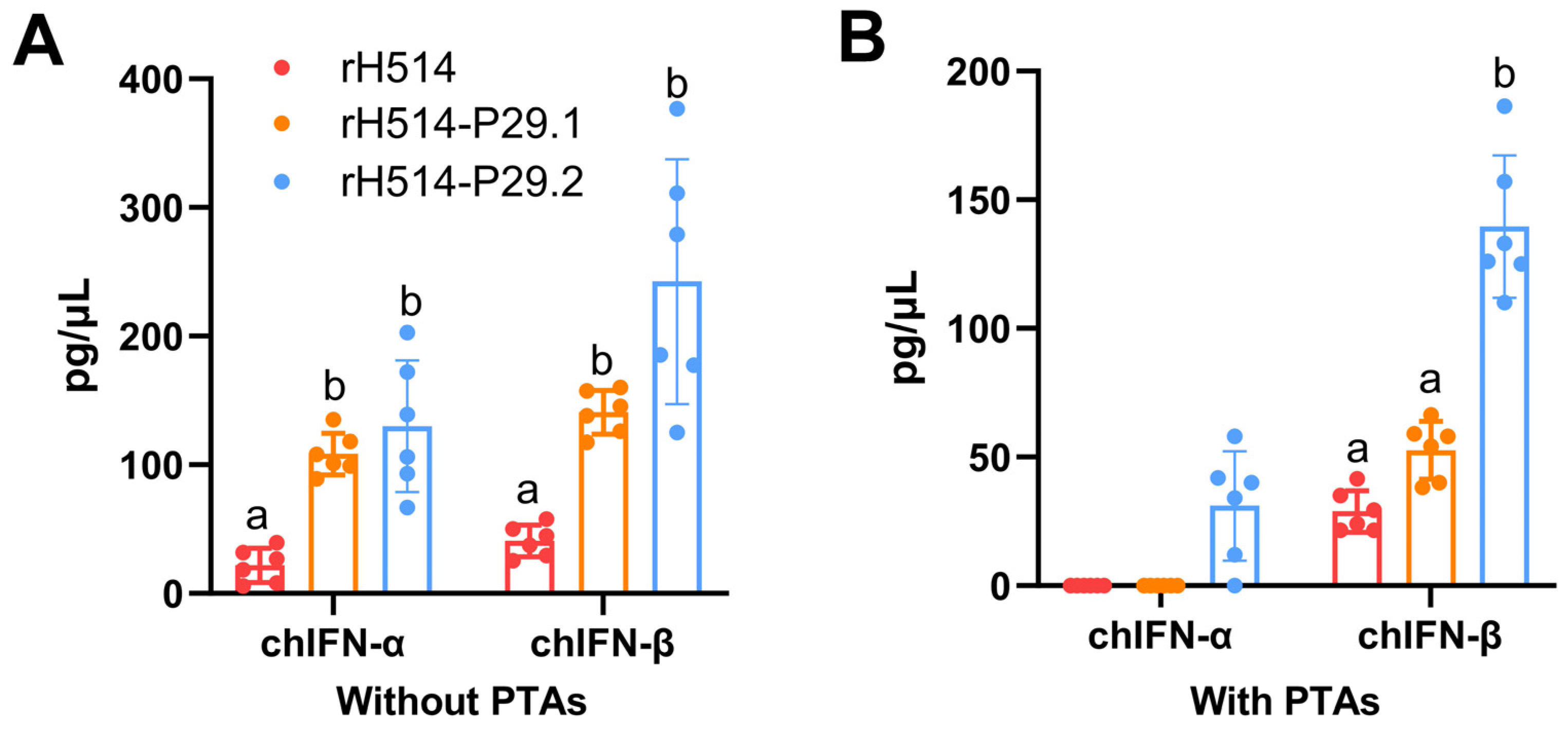

3.4. The rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 Inactivated Vaccines Promote the Secretion of Type ⅠchIFNs

Since IFNs positively stimulate immune responses, the secretion of chIFN stimulated by the rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines were assessed in chickens with or without MDAs. To ensure uniform level of MDAs in chickens, passively transferred rH514-specific antibodies (PTAs) were used to mimic MDAs in one-day-old chickens SPF chickens as described previously [

27,

28,

29]. The animal experiments were performed according to the strategies illustrated in

Figure 4.

After 28 days of vaccination, serum was collected and the secretion of chIFNs in each group was measured by using ELISA Kits. The results indicated that in chickens without MDAs, the rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines stimulated significantly higher both chIFN-α and chIFN-β secretion than the vaccine made with rH514 (

Figure 5A). Similarly, in chickens with PTAs, the vaccine made with rH514-P29.2 stimulated significantly higher both chIFN-α and chIFN-β than the vaccines made with rH514 or rH514-P29.1 (

Figure 5B). ChIFN-γ was not detected in any groups under any condition.

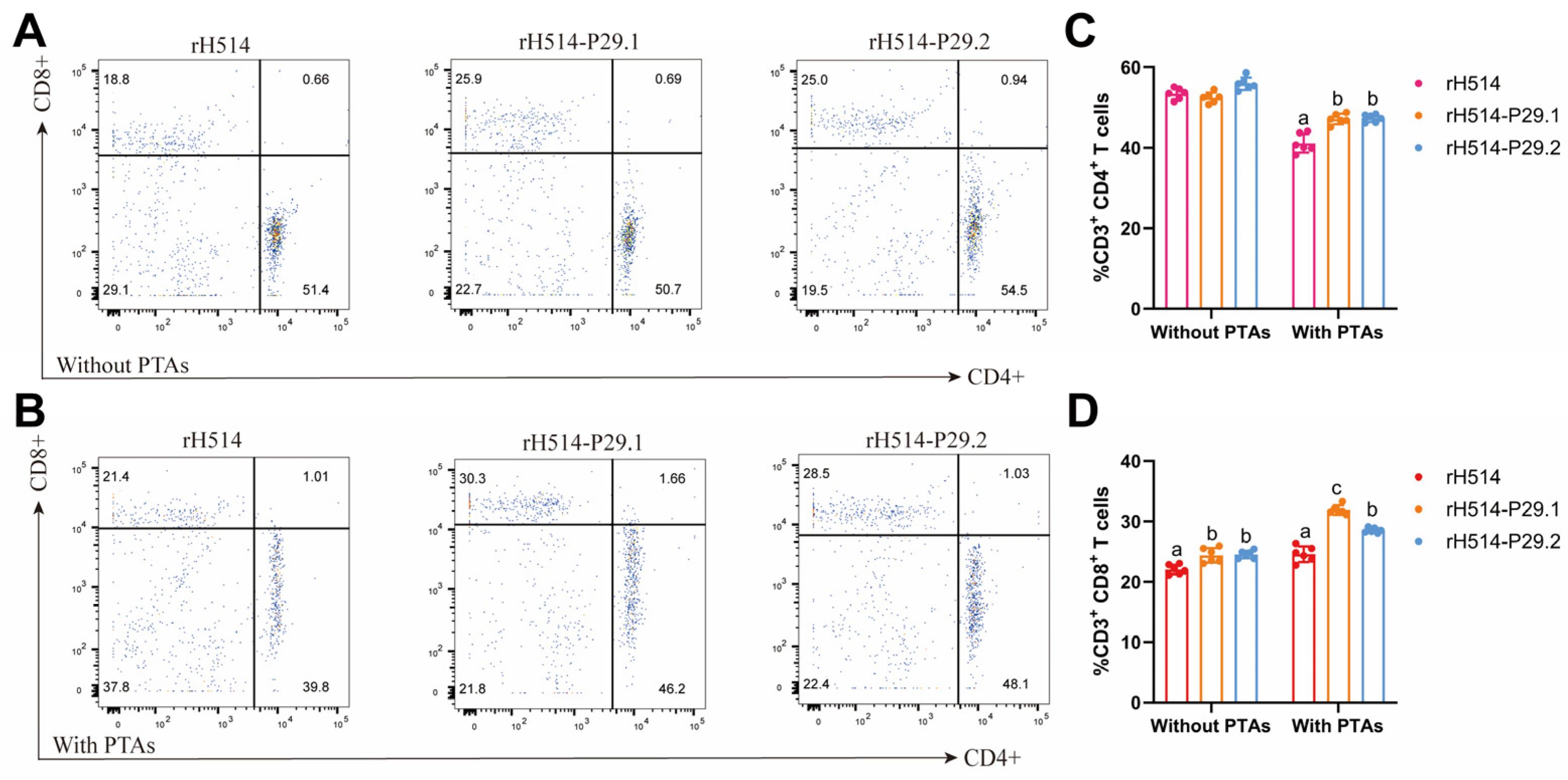

3.5. The rH514-P29.2 Inactivated Vaccines Stimulates Robust Adaptive Immunity in Chickens with MDAs

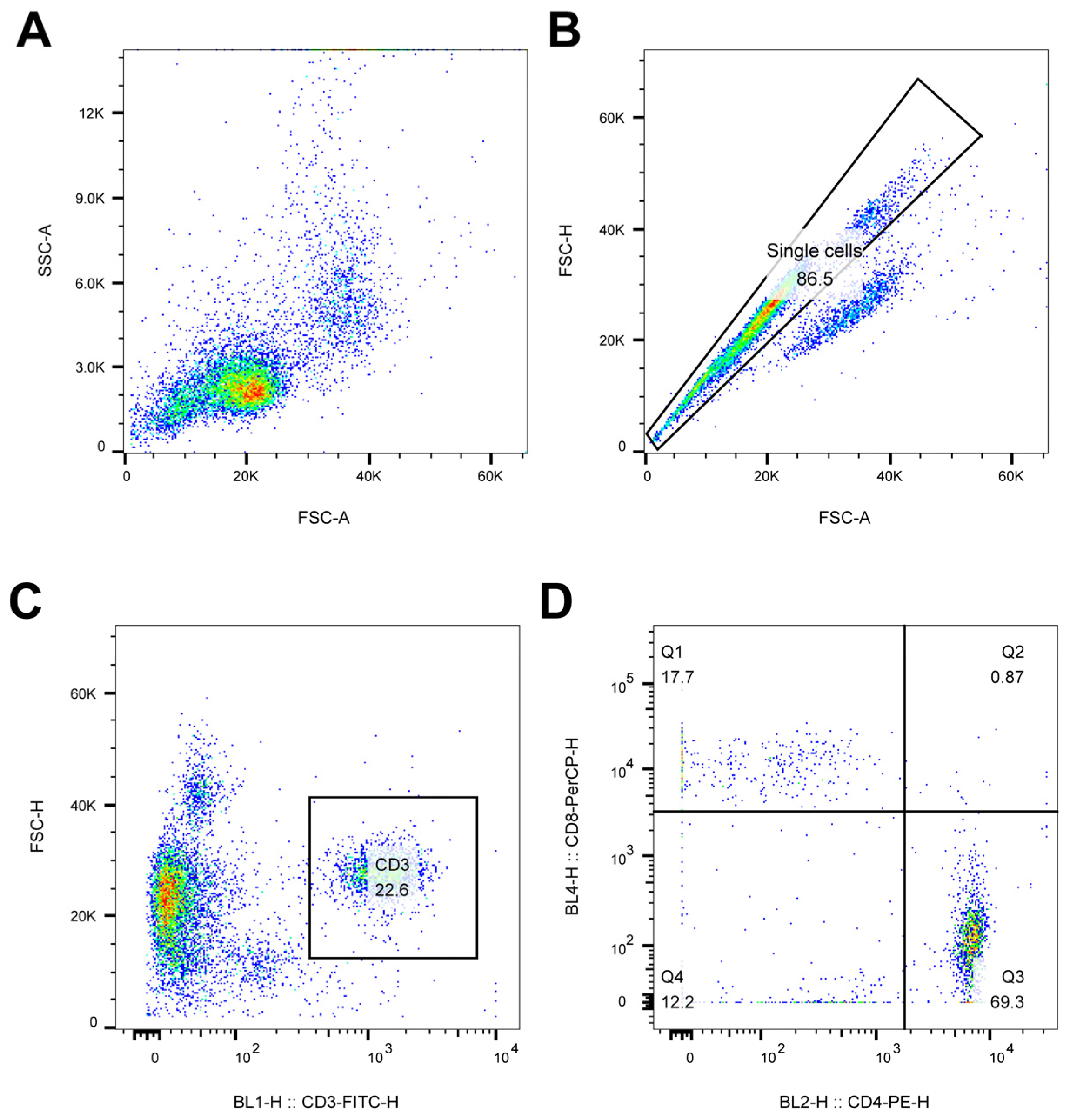

To evaluate whether the inactivated vaccines made with rH514-P29.N (N=1, 2) induce strong cellular immune responses, blood samples were collected from each group and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were separated. Flow cytometry analysis was performed on PBMC to evaluate the cellular immune responses in each group. The gating strategy for lymphocytes identification was illustrated in

Figure 6.

The percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in PBMC was calculated based on these gating strategies by using FlowJo 10.10.0. software. There are the overview proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in chickens with or without MDAs in

Figure 7A and

Figure 7B, respectively. Compared with the rH514 inactivated vaccine, the rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines induced significantly higher CD4+ T cells immune responses in chickens with MDAs (

Figure 7C), and stronger CD8+ T cells immune responses in chicken both with and without MDAs (

Figure 7D).

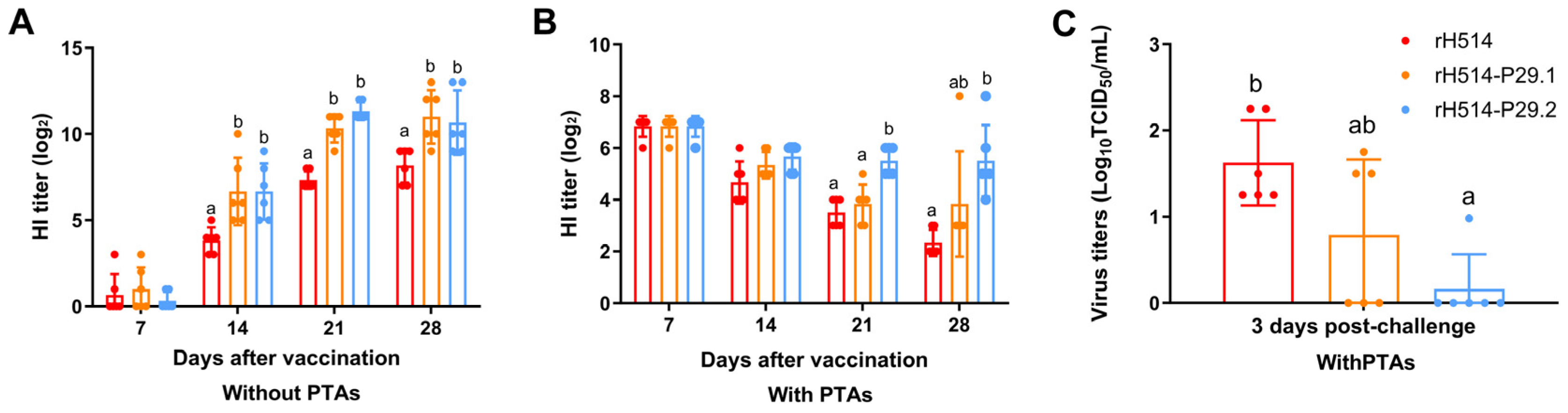

To assess the effectiveness of the rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines in inducing humoral immune responses, we collected serum samples from each group weekly after vaccination. The H514-specific antibodies in serum were measured using HI assay. The results showed that in chickens without MDAs, the rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines induced antibodies more quickly and at higher levels than the rH514 inactivated vaccines after 21 days of vaccination (

Figure 8A). In chickens with MDAs, only the rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccine induced significantly higher antibodies levels than the rH514 inactivated vaccine after 21 days of vaccination (

Figure 8B).

3.6. The rH514-P29.2 Inactivated Vaccine Reduce the Viral Shedding in Chickens with MDAs After Challenge

To gain insight into overcoming MDAs interference, vaccinated chickens with MDAs were challenged with rH514 after 28 days of vaccination. Following this challenge, the oronasal and cloaca swabs were collected at 3 and 5 days post-challenge (d.p.c) to assess viral shedding. The inactivated vaccine made with rH514-P29.2 significantly reduced viral shedding at 3 d.p.c (

Figure 8C). Viral shedding was not detected in cloaca swabs and any groups at 5 d.p.c.

4. Discussion

Antigen bearing two and three copies of C3d increase 1000 and 10000 times immunogenic, respectively [

20]. The minimum-binding domain of C3d, P28 in mammals and P29 in avian species, can also significantly increase the immunogenicity of antigens [

17,

22,

23]. In the present study, we found that HA proteins fused to one (HA-P29.1) and two (HA-P29.2) copies of P29 exhibited high immunogenicity and stimulated strong secretion of typeⅠchIFNs in vitro. Consequently, we rescued two modified H9N2 AIV based on the H514 strain, which express HA-P29.1 (rH514-P29.1) and HA-P29.2 (rH514-P29.2) proteins efficiently. To evaluate whether the vaccines made with rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 could overcome MDAs interference, the inactivated vaccines were used to immunize one-day-old chickens with PTA. The results showed that the rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines induced strong typeⅠchIFNs expression and robust adaptive immune responses in chickens with and without MDAs. More importantly, the rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccine significantly reduced viral shedding compared with the vaccine without P29 in chickens with PTAs, which suggests that vaccine antigens fused two copies of P29 can overcome MDAs interference in chickens.

MDAs are one of the reasons for the failure of vaccination in the field [

5,

13,

38]. Numbers of research have been conducted to develop new vaccines to overcome MDAs interference. The combination of toll like receptor (TLR)-3 and TLR-9 agonists with inactivated measle virus leads to a high level of typeⅠIFN and stimulates strong humoral immune responses in the presence of MDAs in cotton rats [

36,

39]. The CpG ODN (TLR-21 agonist) is reported to overcome MDAs interference when used as an adjuvant for the H9N2 inactivated vaccine in chickens [

40]. Besides TLR agonists, new vaccines conjugating antigens to single chain fragment variable antibodies against chicken antigen presenting cell receptor CD83 can also overcome MDAs interference in chickens [

41]. Due to the characters of cell-associated nature and the nature of replication, turkey herpesvirus (HVT) is used as a live vaccine vector to bypass MDAs interference in chickens [

28,

29,

42,

43]. However, no commercial vaccines that can overcome MDAs interference are extensively applied in the field. This is probably because of the high cost and safety of these vaccine candidates need frequent purification or cold chain preservation. Traditional inactivated vaccine is low-cost but sensitive to MDAs. Therefore, in the present study, we designed a novel inactivated vaccine that stimulated robust immune responses in the presence of MDAs by increasing the immunogenicity of HA proteins.

The immunogenicity of antigens is crucial for vaccines to induce strong immune responses. To enhance the immunogenicity of HA proteins, we fused different copies of P29 (N=1, 2, 3) behind the signal peptide (SP) of HA proteins. We found that 1 (HA-P29.1) and 2 (HA-P29.2) copies of P29 fusion increased the immunogenicity of the recombinant HA proteins by inducing high I chIFN mRNA expression in LMH cells. However, 3 copies of P29 fused to HA proteins (HA-P29.3) were hardly expressed in vitro. This indicates that the insertion of 3 copies of P29 (107 amino acids) into HA proteins may destroy the structure of HA protein. As a consequence, the modified H9N2 AIV expressing HA-P29.3 is not successfully rescued by reverse genetics. However, in contrast to our study, other researchers found that the H1N1 AIV HA proteins fused G proteins of central conserved-domains (114 amino acids) of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) behind SP induce dominant antibodies and protect animals from RSV infection [

44]. It is probably that the HA proteins of H9N2 AIV may be less flexible than those of H1N1 AIV which are compatible with many more amino acids. Beside the position behind SP, the head-domain of HA proteins is also a place to insert foreign antigens. Li et al. reported that inserting 12 amino acids into the head-domain of the H1N1 AIV HA proteins induces strong B- and T-cell immune responses [

45]. However, we found that the insertion of partial P29 (15 or 14 amino acids) into the head-domain will abolish the immunogenicity of the H9N2 AIV HA proteins (data were not shown). This may be because the amino acids we inserted destroyed the structure of the HA protein. Overall, the position behind SP is more flexible than the head-domain of HA proteins.

Activating B cells to stimulate strong humoral immune responses is crucial for inactivated vaccines to protect host from pathogen infections. MDAs-antigen complexes are more likely to bind to B cell receptor (BCR) and Fcγ-receptor IIB (FcγRIIB), which negatively regulate B cells activation and thus interfere with humoral immune responses [

36,

39,

46]. TypeⅠIFN is reported to abolish the negative regulation and promote B cells activation even in the presence of MDAs in cotton rats. The results of our studies match these earlier studies. In this study, we found that the HA-P29.1 and HA-P29.2 proteins stimulated high typeⅠchIFN expression in vitro and in vivo in the presence of MDAs in chickens, which help overcome the interference of MDAs. The reason of typeⅠIFN overcoming MDAs is because it has two receptors: the traditional receptor IFNA-R and the newly found receptor CD21 (CR2), both of which are highly expressed on the surface of B cells [

36]. CD21 is a co-receptor along with CD19 and CD81. Interestingly, CD21 is also the receptor of C3d. While binding to C3d, CD21 generates a downstream signal through CD19 immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs to activate B cells [

47]. Therefore, we hypothesis that C3d and its minimum-binding domain P29 may be capable of promoting B cell activation even in the presence of MDAs in chickens.

To test our hypothesis, we rescued two modified H9N2 AIV: rH514-P29.1 and rH514-P29.2 that constantly express HA-P29.1 and HA-P29.2 proteins, respectively. The vaccine made with rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 significantly increased the expression of typeⅠchIFN and stimulated strong adaptive immune responses in chickens with and without PTAs. The results from our study are in line with previous studies using different methods in other species. The administration of mRNA vaccine encoding spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 attached with 3 copies of C3d induces a 10- times higher level of antibodies than the same mRNA vaccine without C3d in mice [

18]. Furthermore, a polypeptide linear epitope G5 fused to the molecular adjuvant P28 (P29 in chickens) enhances virus neutralizing antibodies and induce a specific T-cell proliferation responses [

23]. Similarly, F proteins of the Newcastle disease virus fused to different copies of P29 (N=1-6) promote the secretion of antigen-specific antibodies and protect chickens from infection [

17].

Until now, the immunogenicity of antigens fused different copies of C3d or P28/P29 has only been explored in animals without MDAs. Little is known about their immunogenicity in animals with MDAs. Lee et al. once inserted part P28 into VP1 of foot-and-mouth disease to develop a new inactivated vaccine. The inactivated vaccine induces robust adaptive immune responses in pigs with MDAs by a booster-vaccination [

25]. By using PTAs to mimic MDAs, we found that the inactivated vaccine made with rH514-P29.2 induced significantly strong adaptive immune responses, reducing viral shedding in chickens with PTAs, which suggests that the vaccine antigens fused two copies of P29 can decrease MDAs interference by only one-shot vaccination. Nevertheless, more experimentation is needed to explore the efficacy of these vaccines in the presence of MDAs in the field.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the rH514 HA proteins fused two copies of P29 stimulated high expression of typeⅠchINF in vitro and in vivo. The inactivated vaccine made with rH514-P29.2 induced robust adaptive immune responses and reduced viral shedding in chickens in the presence of MDAs. We firstly evaluated the immunogenicity of antigens fused different copies of P29 in the presence of MDAs. It is worth to further evaluate efficacy of other subtypes of AIVs fused with different copies of P28/P29 in different species in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xue Pan and Zejun Li; methodology, Fan Zhou; software, Xiaona Shi; validation, Qinfang Liu and Zejun Li; formal analysis, Qiaoyang Teng; investigation, Zhifei Zhang; resources, Bangfeng Xu; data curation, Dawei Yan; writing—original draft preparation, Xue Pan; writing—review and editing, Qinfang Liu; visualization, Chunxiu Yuan; supervision, Zejun Li; project administration, Minghao Yan; funding acquisition, Xue Pan and Zejun Li. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation, grant number: K2024003; Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, grant number: CAAS-CSLPDCP-202402; National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number: 32302861 and Shanghai Municipal Natural Science, grant number: F04617.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal studies were adhered to regulation of Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, and were proved by the institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute (SHVRI). All experiments involving H9N2 AIVs were conducted in the Biological Safety Level 2 (BSL2) facility at the Animal Centre of SHVRI. The permit number was SHVRI-SZ-20240611-01.

Data Availability Statement

All materials are available upon request to interested researchers.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Xiuyun Zhao for modifying the figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIV |

avian influenza virus |

| LPAIV |

low pathogenicity avian influenza virus |

| HA |

hemagglutinin |

| SP |

signal peptide |

| MDAs |

Maternal-derived antibodies |

| PTAs |

passively transferred antibodies |

| SPF |

specific pathogen-free |

| NDV |

Newcastle disease virus |

| SHVRI |

Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute |

| ECEs |

embryonated chicken eggs |

| EID50

|

median egg infectious doses |

| WB |

western blotting |

| IFA |

indirect immunofluorescence assay |

| LMH |

Eghorn male hepatoma |

| PVDF |

polyvinylidene fluoride |

| PBS-T |

phosphate-buffered saline with Tween 20 |

| PBS |

phosphate-buffered saline |

| BSA |

bovine serum albumin |

| chIFNs |

chicken interferons |

| BPL |

β- propiolactone |

| PBMC |

peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| FCM |

flow cytometry |

| TLR |

toll like receptor |

| HVT |

turkey herpesvirus |

| FcγRIIB |

Fcγ-receptor IIB |

References

- Li, C., K. Yu, G. Tian, D. Yu, L. Liu, B. Jing, J. Ping, and H. Chen, Evolution of H9N2 influenza viruses from domestic poultry in Mainland China. Virology, 2005. 340(1): p. 70-83. [CrossRef]

- Gu, M., L. Xu, X. Wang, and X. Liu, Current situation of H9N2 subtype avian influenza in China. Vet Res, 2017. 48(1): p. 49. [CrossRef]

- Peacock, T.H.P., J. James, J.E. Sealy, and M. Iqbal, A Global Perspective on H9N2 Avian Influenza Virus. Viruses, 2019. 11(7). [CrossRef]

- Bahari, P., S.A. Pourbakhsh, H. Shoushtari, and M.A. Bahmaninejad, Molecular characterization of H9N2 avian influenza viruses isolated from vaccinated broiler chickens in northeast Iran. Trop Anim Health Prod, 2015. 47(6): p. 1195-201. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., X. Su, P. Ding, J. Zhao, H. Cui, D. Yan, Q. Teng, X. Li, N. Beerens, H. Zhang, Q. Liu, M.C.M. de Jong, and Z. Li, Maternal-derived antibodies hinder the antibody response to H9N2 AIV inactivated vaccine in the field. Animal Diseases, 2022. 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Forrest, H.L., A. Garcia, A. Danner, J.P. Seiler, K. Friedman, R.G. Webster, and J.C. Jones, Effect of passive immunization on immunogenicity and protective efficacy of vaccination against a Mexican low-pathogenic avian H5N2 influenza virus. Influenza Other Respir Viruses, 2013. 7(6): p. 1194-201. [CrossRef]

- Maas, R., S. Rosema, D. van Zoelen, and S. Venema, Maternal immunity against avian influenza H5N1 in chickens: limited protection and interference with vaccine efficacy. Avian Pathol, 2011. 40(1): p. 87-92. [CrossRef]

- Cardenas-Garcia, S., L. Ferreri, Z. Wan, S. Carnaccini, G. Geiger, A.O. Obadan, C.L. Hofacre, D. Rajao, and D.R. Perez, Maternally-Derived Antibodies Protect against Challenge with Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus of the H7N3 Subtype. Vaccines (Basel), 2019. 7(4). [CrossRef]

- Abdelwhab, E.M., C. Grund, M.M. Aly, M. Beer, T.C. Harder, and H.M. Hafez, Influence of maternal immunity on vaccine efficacy and susceptibility of one day old chicks against Egyptian highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1. Vet Microbiol, 2012. 155(1): p. 13-20. [CrossRef]

- Bennejean, G., M. Guittet, J.P. Picault, J.F. Bouquet, B. Devaux, D. Gaudry, and Y. Moreau, Vaccination of one-day-old chicks against newcastle disease using inactivated oil adjuvant vaccine and/or live vaccine. Avian Pathol, 1978. 7(1): p. 15-27. [CrossRef]

- Eidson, C.S., S.H. Kleven, and P. Villegas, Efficacy of intratracheal administration of Newcastle disease vaccine in day-old chicks. Poult Sci, 1976. 55(4): p. 1252-67. [CrossRef]

- Niewiesk, S., Maternal antibodies: clinical significance, mechanism of interference with immune responses, and possible vaccination strategies. Front Immunol, 2014. 5: p. 446. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z., J. Ni, Y. Cao, and X. Liu, Newcastle Disease Virus as a Vaccine Vector for 20 Years: A Focus on Maternally Derived Antibody Interference. Vaccines (Basel), 2020. 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.C. and D.E. Isenman, Regulation of humoral immunity by complement. Immunity, 2012. 37(2): p. 199-207. [CrossRef]

- Fearon, D.T. and R.M. Locksley, The instructive role of innate immunity in the acquired immune response. Science, 1996. 272(5258): p. 50-3. [CrossRef]

- Fearon, D.T., The complement system and adaptive immunity. Semin Immunol, 1998. 10(5): p. 355-61. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. and Z.X. Niu, Cloning of a gene fragment encoding chicken complement component C3d with expression and immunogenicity of Newcastle disease virus F gene-C3d fusion protein. Avian Pathol, 2008. 37(5): p. 477-85. [CrossRef]

- Li, B., A.Y. Jiang, I. Raji, C. Atyeo, T.M. Raimondo, A.G.R. Gordon, L.H. Rhym, T. Samad, C. MacIsaac, J. Witten, H. Mughal, T.M. Chicz, Y. Xu, R.P. McNamara, S. Bhatia, G. Alter, R. Langer, and D.G. Anderson, Enhancing the immunogenicity of lipid-nanoparticle mRNA vaccines by adjuvanting the ionizable lipid and the mRNA. Nature Biomedical Engineering, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K., X. Duan, L. Hao, X. Wang, and Y. Wang, Immune Effect of Newcastle Disease Virus DNA Vaccine with C3d as a Molecular Adjuvant. J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2017. 27(11): p. 2060-2069. [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, P.W., M.E. Allison, S. Akkaraju, C.C. Goodnow, and D.T. Fearon, C3d of complement as a molecular adjuvant: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Science, 1996. 271(5247): p. 348-50. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, I., T.M. Ross, S. Tamura, T. Ichinohe, S. Ito, H. Takahashi, H. Sawa, J. Chiba, T. Kurata, T. Sata, and H. Hasegawa, Protection against influenza virus infection by intranasal administration of C3d-fused hemagglutinin. Vaccine, 2003. 21(31): p. 4532-8. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z., H. Wang, Y. Feng, Q. Li, and J. Li, A candidate DNA vaccine encoding a fusion protein of porcine complement C3d-P28 and ORF2 of porcine circovirus type 2 induces cross-protective immunity against PCV2b and PCV2d in pigs. Virol J, 2019. 16(1): p. 57. [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Romero, G., M. Salas-Rojas, E.N. Pompa-Mera, K. Chavez-Rueda, and A. Aguilar-Setien, Addition of C3d-P28 adjuvant to a rabies DNA vaccine encoding the G5 linear epitope enhances the humoral immune response and confers protection. Vaccine, 2018. 36(2): p. 292-298. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W., S. Sha, T. Jiang, X. Xing, and Y. Cao, A new DNA vaccine fused with the C3d-p28 induces a Th2 immune response against amyloid-beta. Neural Regen Res, 2013. 8(27): p. 2581-90.

- Lee, M.J., H.M. Kim, S. Shin, H. Jo, S.H. Park, S.M. Kim, and J.H. Park, The C3d-fused foot-and-mouth disease vaccine platform overcomes maternally-derived antibody interference by inducing a potent adaptive immunity. NPJ Vaccines, 2022. 7(1): p. 70. [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, S., K. Mahmoud, and M. Al-Natour, Field evaluation of maternal antibody transfer to a group of pathogens in meat-type chickens. Poult Sci, 2008. 87(8): p. 1550-5. [CrossRef]

- Hamal, K.R., S.C. Burgess, I.Y. Pevzner, and G.F. Erf, Maternal antibody transfer from dams to their egg yolks, egg whites, and chicks in meat lines of chickens. Poult Sci, 2006. 85(8): p. 1364-72. [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, O.B., C. Estevez, Q. Yu, and D.L. Suarez, Passive antibody transfer in chickens to model maternal antibody after avian influenza vaccination. Vet Immunol Immunopathol, 2013. 152(3-4): p. 341-7. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., Q. Liu, S. Niu, D. Huang, D. Yan, Q. Teng, X. Li, N. Beerens, M. Forlenza, M.C.M. de Jong, and Z. Li, Efficacy of a recombinant turkey herpesvirus (H9) vaccine against H9N2 avian influenza virus in chickens with maternal-derived antibodies. Front Microbiol, 2022. 13: p. 1107975. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., H. Chen, P. Jiao, G. Deng, G. Tian, Y. Li, E. Hoffmann, R.G. Webster, Y. Matsuoka, and K. Yu, Molecular basis of replication of duck H5N1 influenza viruses in a mammalian mouse model. J Virol, 2005. 79(18): p. 12058-64. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J. and T.D. Schmittgen, Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods, 2001. 25(4): p. 402-8.

- Klimov, A., A. Balish, V. Veguilla, H. Sun, J. Schiffer, X. Lu, J.M. Katz, and K. Hancock, Influenza virus titration, antigenic characterization, and serological methods for antibody detection. Methods Mol Biol, 2012. 865: p. 25-51.

- Ramakrishnan, M. and M. Dhanavelu, Influence of Reed-Muench Median Dose Calculation Method in Virology in the Millennium. Antiviral Research, 2018. 28: p. 16-18.

- Lone, N.A., E. Spackman, and D. Kapczynski, Immunologic evaluation of 10 different adjuvants for use in vaccines for chickens against highly pathogenic avian influenza virus. Vaccine, 2017. 35(26): p. 3401-3408. [CrossRef]

- Suarez, D.L., M.L. Perdue, N. Cox, T. Rowe, C. Bender, J. Huang, and D.E. Swayne, Comparisons of highly virulent H5N1 influenza A viruses isolated from humans and chickens from Hong Kong. J Virol, 1998. 72(8): p. 6678-88. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. and S. Niewiesk, Synergistic induction of interferon alpha through TLR-3 and TLR-9 agonists identifies CD21 as interferon alpha receptor for the B cell response. PLoS Pathog, 2013. 9(3): p. e1003233. [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, K., M.A. Oropallo, M.P. Cancro, and A. Marshak-Rothstein, Role of type I interferons in the activation of autoreactive B cells. Immunol Cell Biol, 2012. 90(5): p. 498-504. [CrossRef]

- Sunwoo, S.Y., M. Schotsaert, I. Morozov, A.S. Davis, Y. Li, J. Lee, C. McDowell, P. Meade, R. Nachbagauer, A. Garcia-Sastre, W. Ma, F. Krammer, and J.A. Richt, A Universal Influenza Virus Vaccine Candidate Tested in a Pig Vaccination-Infection Model in the Presence of Maternal Antibodies. Vaccines (Basel), 2018. 6(3). [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. and S. Niewiesk, Synergistic induction of interferon alpha through TLR-3 and TLR-9 agonists stimulates immune responses against measles virus in neonatal cotton rats. Vaccine, 2014. 32(2): p. 265-70. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X., Q. Liu, M.C.M. de Jong, M. Forlenza, S. Niu, D. Yan, Q. Teng, X. Li, N. Beerens, and Z. Li, Immunoadjuvant efficacy of CpG plasmids for H9N2 avian influenza inactivated vaccine in chickens with maternal antibodies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol, 2023. 259: p. 110590. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A., R. Meeuws, J.R. Sadeyen, P. Chang, M. Van Hulten, and M. Iqbal, Haemagglutinin antigen selectively targeted to chicken CD83 overcomes interference from maternally derived antibodies in chickens. NPJ Vaccines, 2022. 7(1): p. 33. [CrossRef]

- Bublot, M., N. Pritchard, F.X. Le Gros, and S. Goutebroze, Use of a vectored vaccine against infectious bursal disease of chickens in the face of high-titred maternally derived antibody. J Comp Pathol, 2007. 137 Suppl 1: p. S81-4. [CrossRef]

- Bertran, K., D.H. Lee, M.F. Criado, C.L. Balzli, L.F. Killmaster, D.R. Kapczynski, and D.E. Swayne, Maternal antibody inhibition of recombinant Newcastle disease virus vectored vaccine in a primary or booster avian influenza vaccination program of broiler chickens. Vaccine, 2018. 36(43): p. 6361-6372. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.N., H. Suk Hwang, M.C. Kim, Y.T. Lee, M.K. Cho, Y.M. Kwon, J. Seok Lee, R.K. Plemper, and S.M. Kang, Recombinant influenza virus carrying the conserved domain of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) G protein confers protection against RSV without inflammatory disease. Virology, 2015. 476: p. 217-225. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., V. Polonis, H. Isobe, H. Zaghouani, R. Guinea, T. Moran, C. Bona, and P. Palese, Chimeric influenza virus induces neutralizing antibodies and cytotoxic T cells against human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol, 1993. 67(11): p. 6659-66. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., D. Huey, M. Oglesbee, and S. Niewiesk, Insights into the regulatory mechanism controlling the inhibition of vaccine-induced seroconversion by maternal antibodies. Blood, 2011. 117(23): p. 6143-51. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.R., M.D. Moore, and G.R. Nemerow, Immunobiology of CR2, the B lymphocyte receptor for Epstein-Barr virus and the C3d complement fragment. Annu Rev Immunol, 1988. 6: p. 85-113. [CrossRef]

Figure 2.

The mRNA expression of chIFN-α, β and γ stimulated by HA and HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) proteins in transfected LMH cells. LMH cells were transfected with pCAGGS-HA, pCAGGS-HA–P29.1, pCAGGS-HA–P29.2, pCAGGS-HA–P29.3 or empty plasmid as negative control. After 12 hours of transfection, cells were harvested to examine the relative mRNA expression of chIFN-α, β and γ by Real-time PCR. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Figure 2.

The mRNA expression of chIFN-α, β and γ stimulated by HA and HA-P29.N (N=1, 2, 3) proteins in transfected LMH cells. LMH cells were transfected with pCAGGS-HA, pCAGGS-HA–P29.1, pCAGGS-HA–P29.2, pCAGGS-HA–P29.3 or empty plasmid as negative control. After 12 hours of transfection, cells were harvested to examine the relative mRNA expression of chIFN-α, β and γ by Real-time PCR. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Figure 4.

The schematic of animal experimental strategy. Passively transferred 0.3 mL of H514-specific antibodies (PTAs) into one-day-old chickens (n=6/group) via intravenous injection to mimic MDAs. Chickens were immediately and subcutaneously vaccinated with 0.1 mL of the rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines. Sera and PBMC were collected at indicated time points. Chickens were intranasally challenged with 106EID50 of H514 (0.1mL/chicken) at 28 d.p.i. Oronasal and cloaca swabs were collected at indicated time points.

Figure 4.

The schematic of animal experimental strategy. Passively transferred 0.3 mL of H514-specific antibodies (PTAs) into one-day-old chickens (n=6/group) via intravenous injection to mimic MDAs. Chickens were immediately and subcutaneously vaccinated with 0.1 mL of the rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines. Sera and PBMC were collected at indicated time points. Chickens were intranasally challenged with 106EID50 of H514 (0.1mL/chicken) at 28 d.p.i. Oronasal and cloaca swabs were collected at indicated time points.

Figure 5.

The chIFN-α and β expression in sera of vaccinated chickens with and without PTAs. The chickens without (A) and with (B) PTAs were inoculated with rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines. The amount of chIFN-α and -β in sera collected at 28 d.p.i were detected using ELISA kit. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Figure 5.

The chIFN-α and β expression in sera of vaccinated chickens with and without PTAs. The chickens without (A) and with (B) PTAs were inoculated with rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines. The amount of chIFN-α and -β in sera collected at 28 d.p.i were detected using ELISA kit. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Figure 6.

Gating strategy for lymphocytes identification by flow cytometry analysis. Putative lymphocytes were gated based on the light scatter properties (A) and doublet cells were excluded based on FSC-A versus FSC-H (B). T cells were identified as being CD3+ (C) and two subsets were identified in this way: CD3+CD4+CD8- and CD3+CD4-CD8+ T cells.

Figure 6.

Gating strategy for lymphocytes identification by flow cytometry analysis. Putative lymphocytes were gated based on the light scatter properties (A) and doublet cells were excluded based on FSC-A versus FSC-H (B). T cells were identified as being CD3+ (C) and two subsets were identified in this way: CD3+CD4+CD8- and CD3+CD4-CD8+ T cells.

Figure 7.

The proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ in PBMC of vaccinated chickens with and without MDAs. The chickens with and without MDAs were inoculated with rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines. PBMC was collected at 14 d.p.i. and subject to FCM to show an overview of CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T cells in each group. The total proportions of CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) T cells were calculated and presented. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Figure 7.

The proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ in PBMC of vaccinated chickens with and without MDAs. The chickens with and without MDAs were inoculated with rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines. PBMC was collected at 14 d.p.i. and subject to FCM to show an overview of CD4+ (A) and CD8+ (B) T cells in each group. The total proportions of CD4+ (C) and CD8+ (D) T cells were calculated and presented. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Figure 8.

The humoral immune response in vaccinated chickens with and without PTAs and viral shedding after challenge. Chickens were inoculated with the rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines and sera were collected weekly. The H514-specific antibodies in chickens without (A) and with (B) PTAs were evaluated by HI. (C)The viral titers from oropharyngeal swabs of vaccinated and challenged chickens with PTAs were detected at 3 d.p.c. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Figure 8.

The humoral immune response in vaccinated chickens with and without PTAs and viral shedding after challenge. Chickens were inoculated with the rH514, rH514-P29.1 or rH514-P29.2 inactivated vaccines and sera were collected weekly. The H514-specific antibodies in chickens without (A) and with (B) PTAs were evaluated by HI. (C)The viral titers from oropharyngeal swabs of vaccinated and challenged chickens with PTAs were detected at 3 d.p.c. Different letters denote significant differences among each group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Table 1.

The nucleotides of different linkers.

Table 1.

The nucleotides of different linkers.

| Linker |

Sequence (5′→3′) |

| (GGGGS)-1 |

GGTGGCGGAGGGAGT |

| (GGGGS)-2 |

GGCGGGGGAGGTAGC |

| (GGGGS)-3 |

GGAGGTGGCGGGTCT |

| (GGGGS)-4 |

GGGGGCGGTGGATCC |

Table 2.

The primers for PCR and RT-PCR.

Table 2.

The primers for PCR and RT-PCR.

| Primer name |

Sequence (5′→3′) |

| HA1-F |

ATGGAGACAGTATCA |

| HA1-R |

ACTCCCTCCGCCACCTGCATAGCTTACTGTTG |

| HA2-F |

GGGGGCGGTGGATCCGATAAAATCTGCATCGGCTACCAATC |

| HA2-R |

CTATATACAAATGTTGCATC |

| P29.1-F |

GGTGGCGGAGGGAGT |

| P29.1-R |

GCTACCTCCCCCGCC |

| P29.2-R |

AGACCCGCCACCTCC |

| P29.3-R |

GGATCCACCGCCCCC |

| Pcaggs-HA-P29.N-F |

GTCTCATCATTTTGGCAAAG ATGGAGACAGTATCA |

| Pcaggs-HA-P29.N-R |

AGGGAAAAAGATCTGCTAGC CTATATACAAATGTTGCATC |

| PHW-HA-P29.N-F |

GGGGAGCAAAAGCAGGGGATA |

| PHW-HA-P29.N-R |

GGTTATTAGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTT |

| PHW-PB2-F |

CCAGCGAAAGCAGGTC |

| PHW-PB2-R |

TTAGTAGAAACAAGGTCGTTT |

| PHW-PB1-F |

CACACAGCTCTTCGGCCAGCGAAAGCAGGCA |

| PHW-PB1-R |

CACACAGCTCTTCTATTAGTAGAAACAAGGCATTT |

| PHW-PA-F |

CCAGCGAAAGCAGGTAC |

| PHW-PA-R |

TTAGTAGAAACAAGGTACTT |

| PHW-HA-F |

TTAGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTT |

| PHW-HA-R |

CCAGCAAAAGCAGGGG |

| PHW-NP-F |

CACACAGCTCTTCGGCCAGCAAAAGCAGGGTA |

| PHW-NP-R |

CACACAGCTCTTCTATTAGTAGAAACAAGGGTATTTTT |

| PHW-NA-F |

CACACAGCTCTTCGGCCAGCAAAAGCAGGAGT |

| PHW-NA-R |

CACACAGCTCTTCTATTAGTAGAAACAAGGAGTTTTTT |

| PHW-M-F |

CACACAGCTCTTCTATTAGCAAAAGCAGGTAG |

| PHW-M-R |

CACACAGCTCTTCGGCCAGTAGAAACAAGGTAGTTTTT |

| PHW-NS-F |

CACACAGCTCTTCTATTAGCAAAAGCAGGGTG |

| PHW-NS-R |

CACACAGCTCTTCGGCCAGTAGAAACAAGGGTGTTTT |

| chIFN-α-F |

CCTTCCTCCAAGACAACGATTAC |

| chIFN-α-Probe |

TTGTGGATGTGCAGGAACCAGGC |

| chIFN-α-R |

AGTGCGAGTGATAAATGTGAGG |

| chIFN-β-F |

CCTTGAGCAATGCTTCGTAAAC |

| chIFN-β-Probe |

CAACGCTCACCTCAGCATCAACAA |

| chIFN-β-R |

GGAAGTTGTGGATGGATCTGAA |

| chIFN-γ-F |

GTGAAGAAGGTGAAAGATATCATGGA |

| chIFN-γ-Probe |

TGGCCAAGCTCCCGATGAACGA |

| chIFN-γ-R |

GCTTTGCGCTGGATTCTCA |

Table 3.

The information of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N (N=1, 2) viruses.

Table 3.

The information of the rH514 and rH514-P29.N (N=1, 2) viruses.

| Virus |

HA titer (Log2) |

EID50 (Log10/mL) |

| rH514 |

10 |

9.50 |

| rH514-P29.1 |

10 |

9.50 |

| rH514-P29.2 |

9 |

9.50 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).