Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Changes in Behavior After Soil Improvement

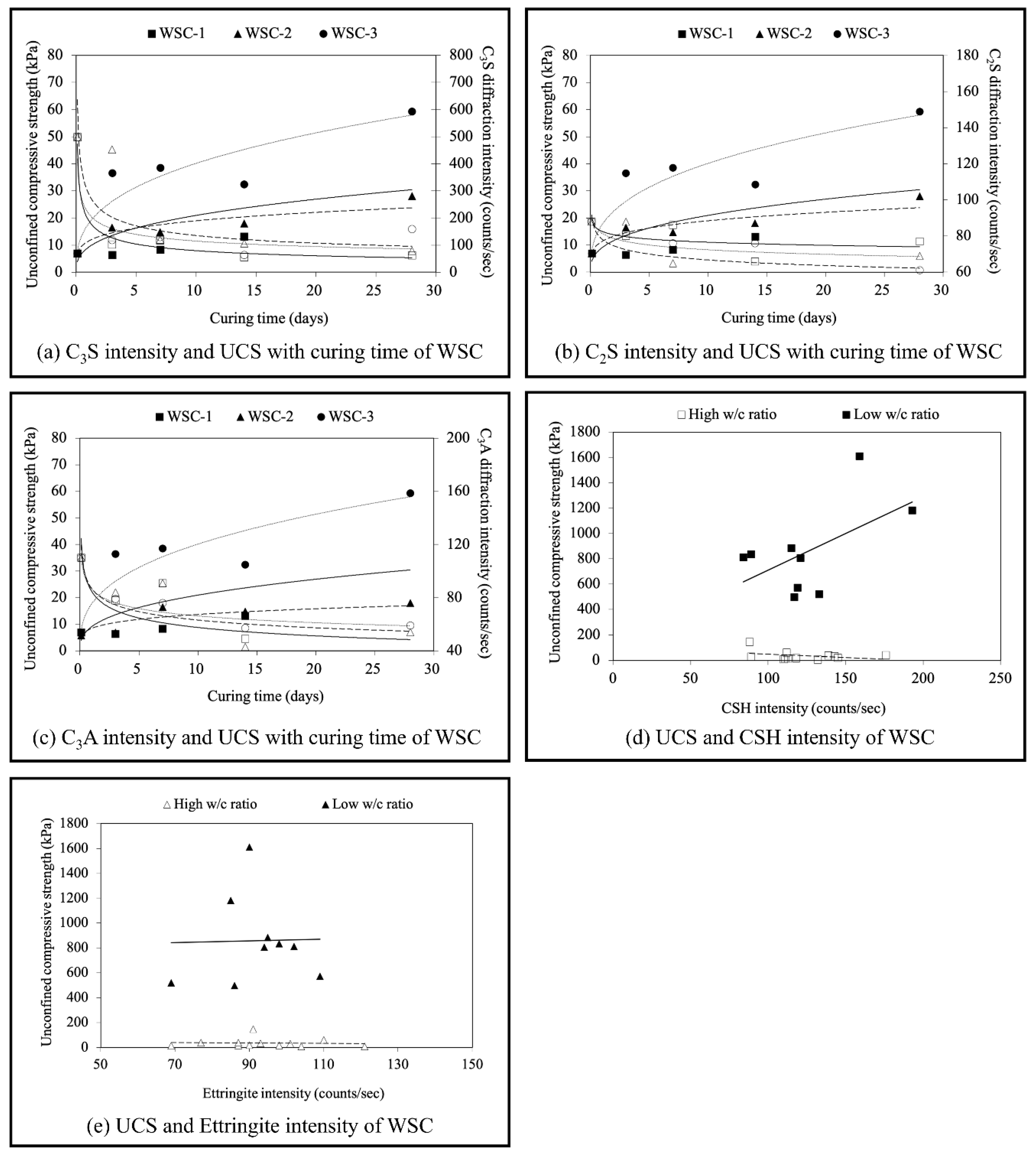

3.2. Reaction Product by X-Ray Diffraction Technique

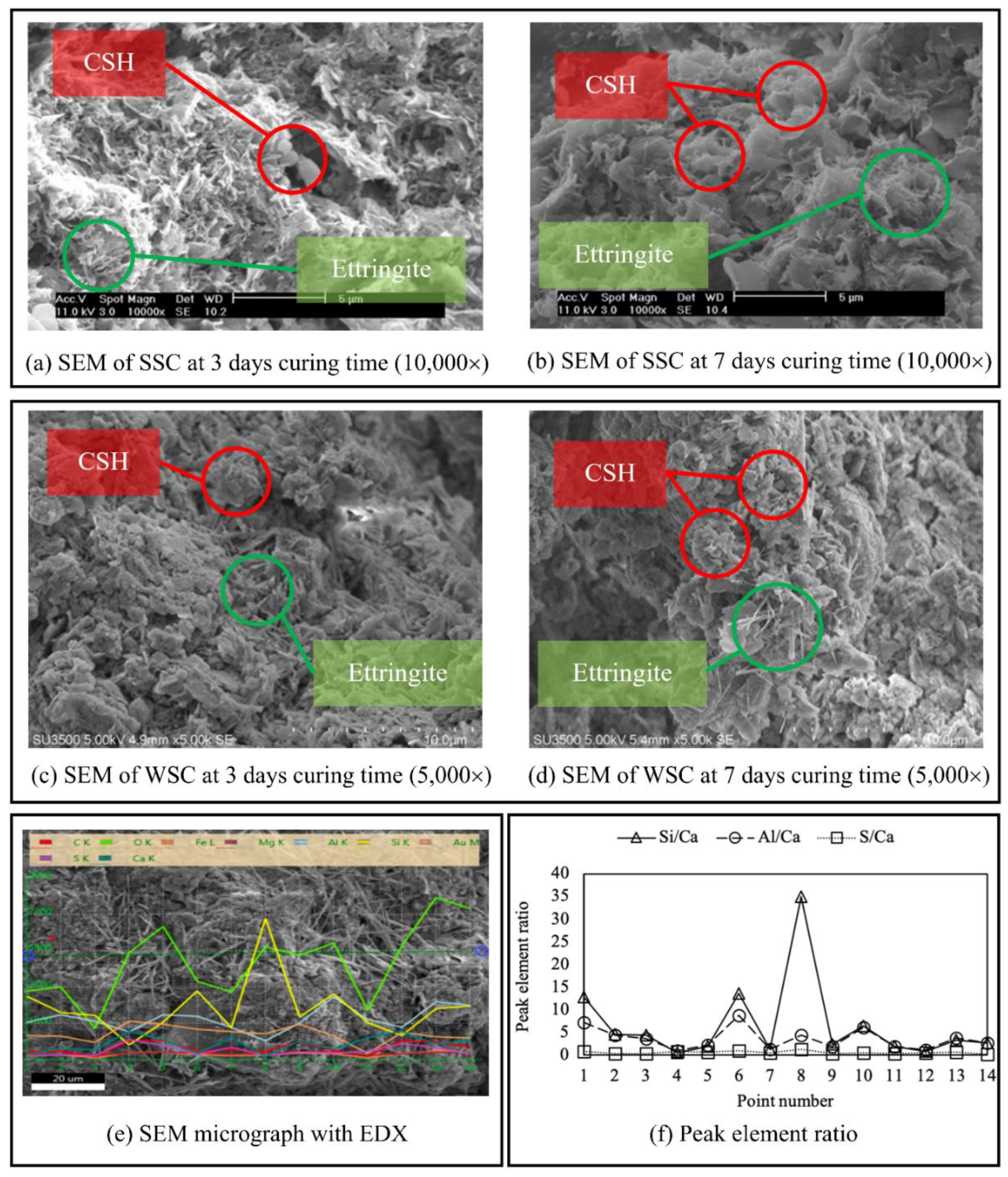

3.3. Internal Structure of Cement Treated Sludges by SEM

3.4. EDX Confirmation of Reaction Products in Improved Sludges

4. Conclusions

- (1)

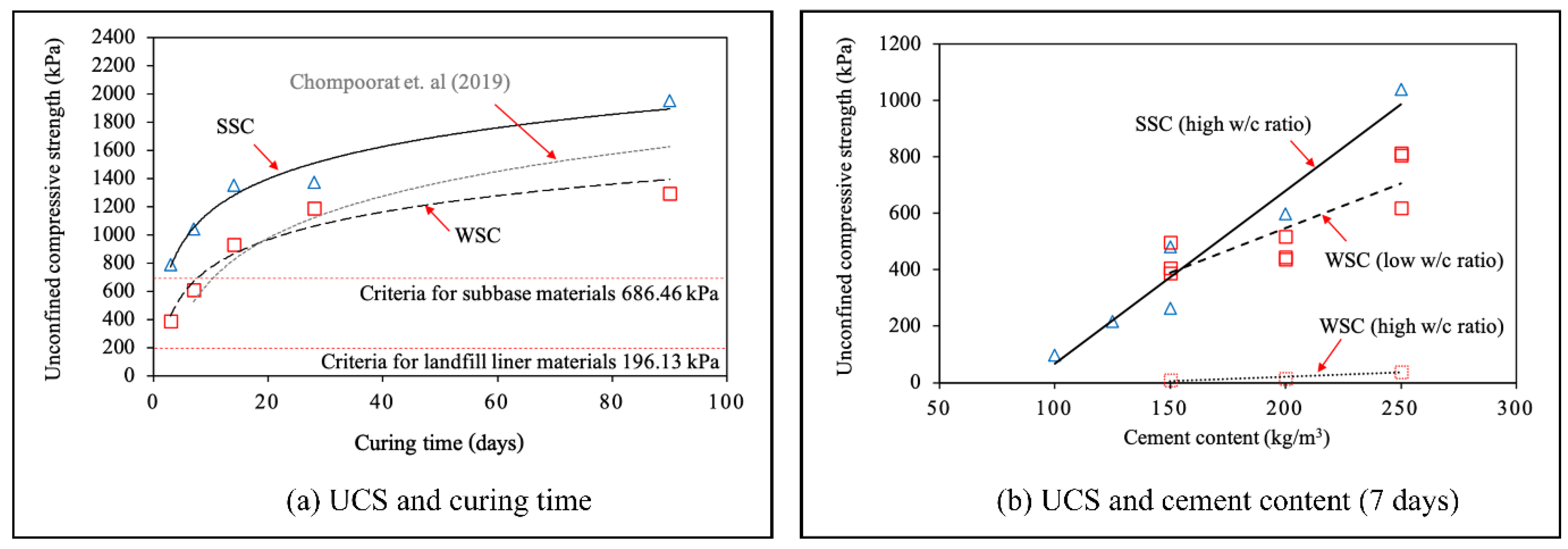

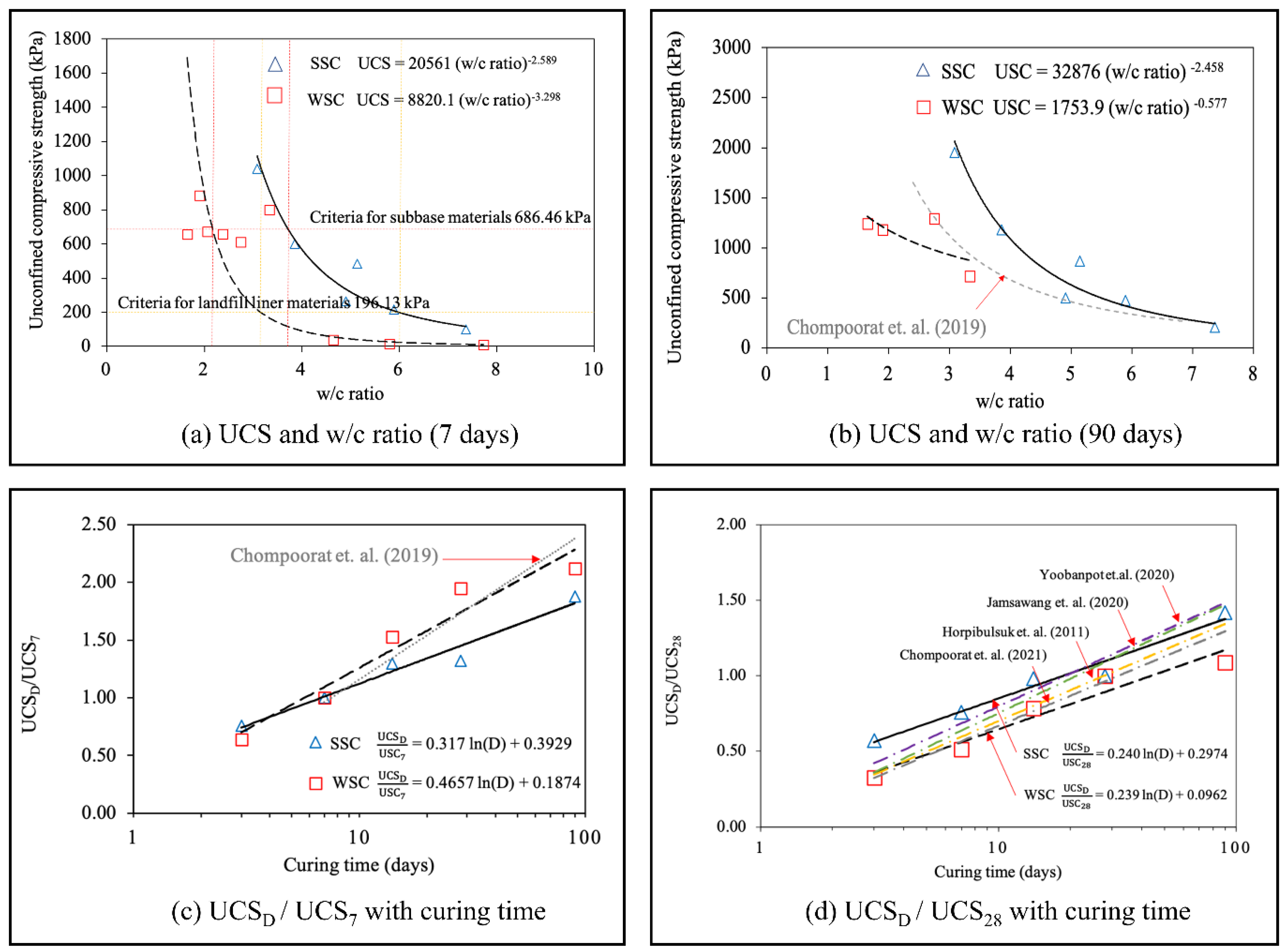

- Both SS and WS have high moisture content and require moisture reduction using dewatering process and appropriate cement mixing to achieve a suitable w/c ratio, thus improving quality. As the w/c ratio decreased, the UCS increased, meeting the Department of Rural Roads of Thailand's standards for subbase materials. For SSC, a w/c ratio of less than 3.5 is recommended for highway subbases, while a ratio below 6 is suitable for landfill liners. WSC requires an even lower ratio, below 3.5, for both applications.

- (2)

- The UCS after 7 days and 28 days of curing (UCS7 and UCS28) serve as effective normalization benchmarks for predicting strength. The ratios of UCSD/UCS7 and UCSD/UCS28 were proposed and consistently found to increase with longer curing times.

- (3)

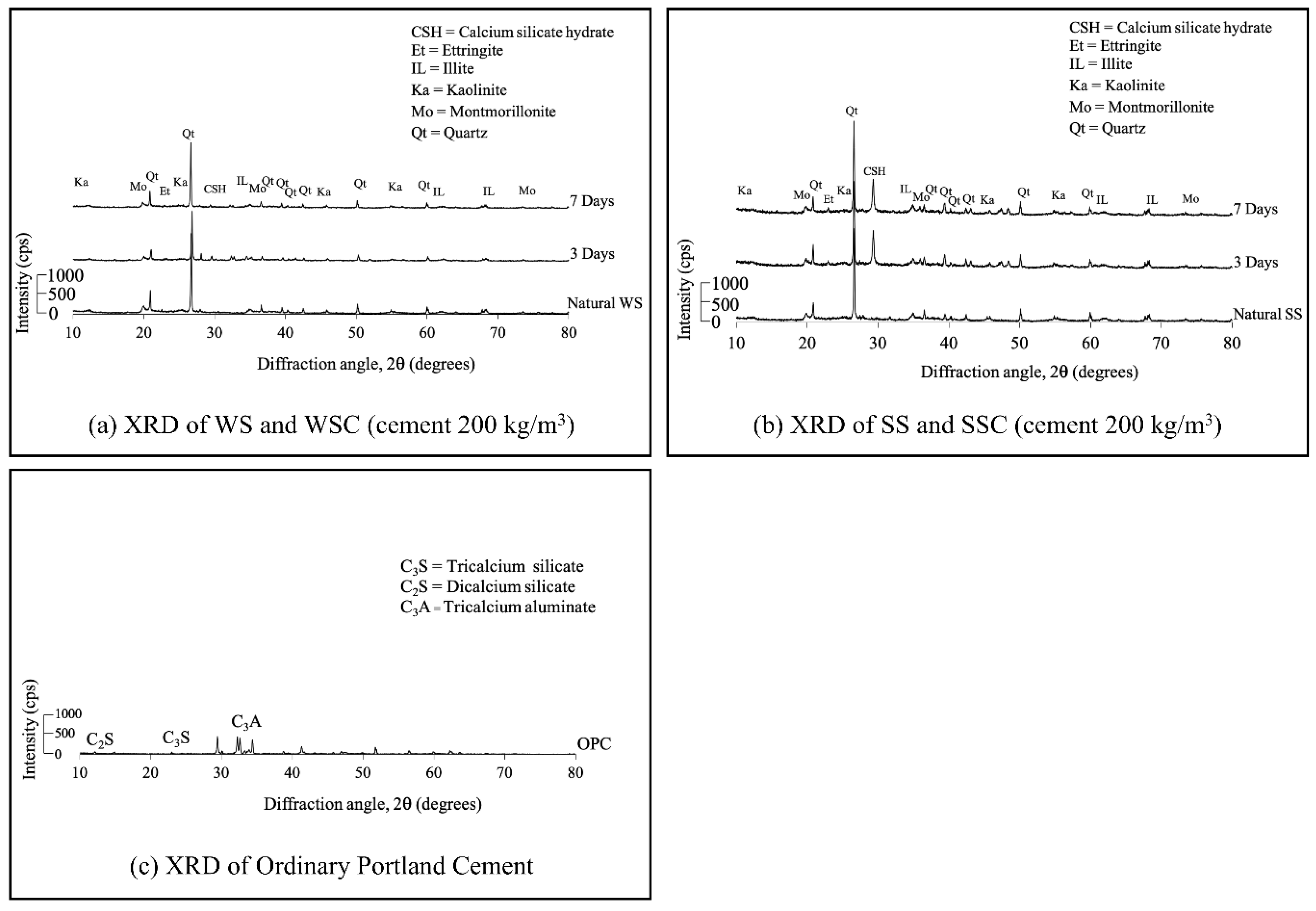

- XRD and SEM-EDX analysis confirmed that calcium silicate hydrate (CSH) and ettringite were key contributors to strength development. Elemental composition was assessed using Peak Element Ratios () and Surface Area Ratios (), with Si/Ca ratios ranging from 0.58 to 6.40, indicating CSH. S/Ca ratios ranged from 0.33 to 0.77, and Al/Ca ratios from 1.00 to 6.20, suggesting the presence of calcium aluminate hydrate (CAH) or needle-like ettringite.

- (4)

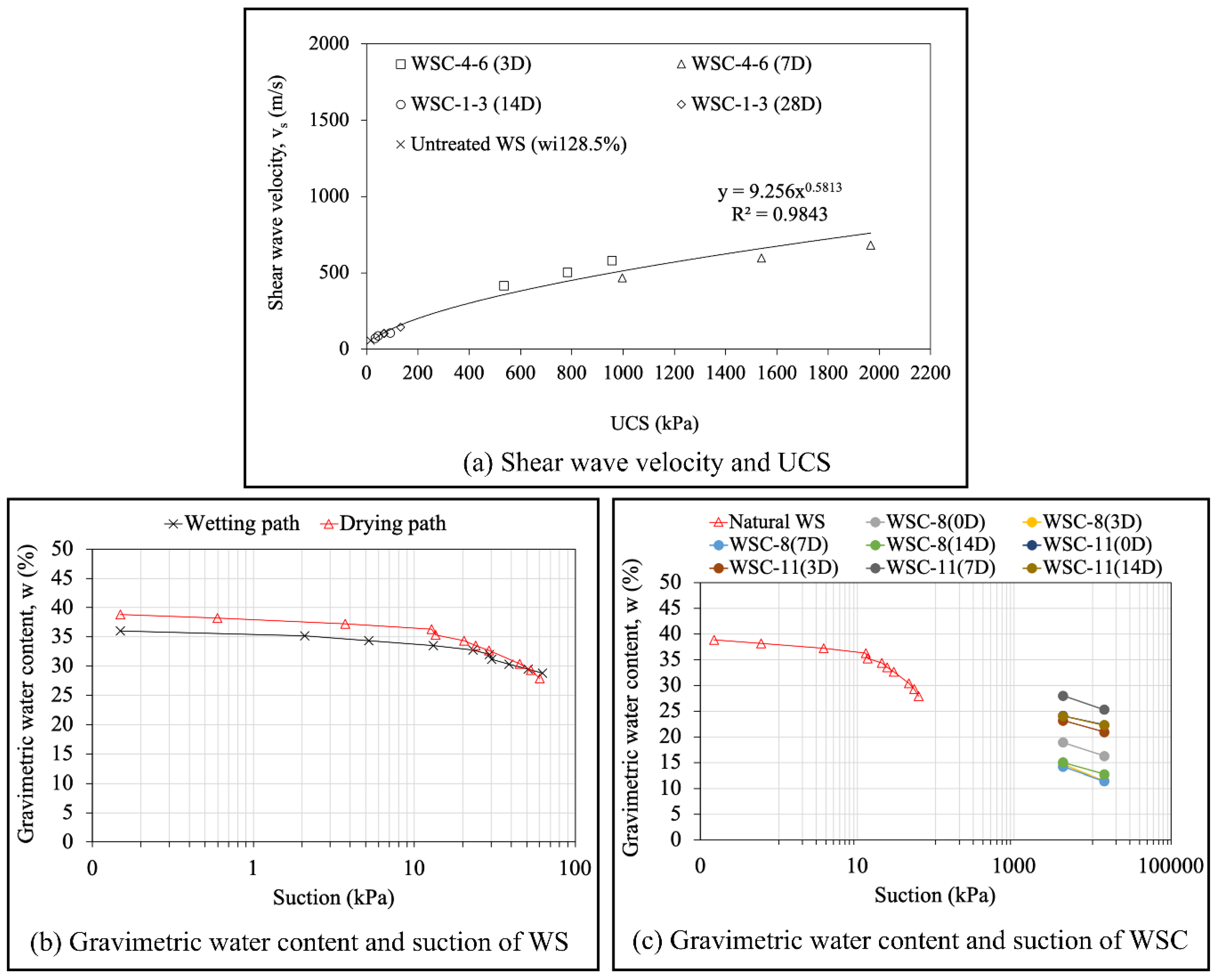

- Suction tests revealed that moisture content of cement-treated sludges decreases compared to the original condition, confirming the occurrence of the hydration reaction. This corresponds with the increase in UCS and enhanced hardness of the cement-treated sludges. As a result, the shear wave velocity () also increased with curing time. In addition, the correlation between UCS and was proposed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jagaba, A.H.; Shuaibu, A.; Umaru, I.; Musa, S.; Lawal, I.M.; Abubakar, S. Stabilization of soft soil by incinerated sewage sludge ash from municipal wastewater treatment plant for engineering construction. Sustain. Struct. Mater. 2019, 2, 32–44. [Google Scholar]

- Thongdetsri, T.; Khumsuprom, N.; Noipasee, S.; Pongpayuha, P.; Jotisankasa, A.; Inazumi, S.; Nontananandh, S. Improvement of High-Water Content Sludges Using Ordinary Portland Cement as Construction Materials. In Proceedings of the 21st Southeast Asian Geotechnical Conference and 4th AGSSEA Conference (SEAGC-AGSSEA 2023), Bangkok, Thailand; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yekeen, N.; Padmanabhan, E.; Idris, A.K.; Chauhan, P.S. Nanoparticles applications for hydraulic fracturing of unconventional reservoirs: A comprehensive review of recent advances and prospects. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 178, 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inazumi, S.; Shiina, M.; Nakao, K. Aeration Curing for Recycling Construction-Generated Sludge, and Its Effect of Immobilizing Carbon Dioxide. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.T.; Satomi, T.; Takahashi, H. Study on sludge recycling with compaction type and placing type by rice husk-cement-stabilized soil method. Adv. Exp. Mech. 2017, 2, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Zhou, F.; Ma, Q.; Li, W.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, D. Investigation on strength properties of phosphogypsum-dredged soil stabilized by carbide slag activated ground granulated blast-furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 457, 139427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, L.S.; Nakarai, K.; Duc, M.; Kouby, A.L.; Maachi, A.; Sasaki, T. Analysis of Strength Development in Cement-Treated Soils under Different Curing Conditions through Microstructural and Chemical Investigations. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 166, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamsawang, P.; Charoensil, S.; Namjan, T.; Jongpradist, P.; Likitlersuang, S. Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of Dredged Sediments Treated with Cement and Fly Ash for Use as Road Materials. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2020, 21, 2498–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barus, R.M.N.; Jotisankasa, A.; Chaiprakaikeow, S.; Nontananandh, S.; Inazumi, S.; Sawangsuriya, A. Effects of Relative Humidity During Curing on Small-Strain Modulus of Cement-Treated Silty Sand. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2021, 39, 2131–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horpibulsuk, S.; Miura, N.; Nagaraj, T.S. Assessment of Strength Development in Cement-Admixed High Water Content Clays with Abrams’ Law as a Basis. Geotechnique 2003, 53, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, V.; Simão, N.; Freire, A.C. A Soil-Cement Formulation for Road Pavement Base and Sub Base Layers: A Case Study. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotech. 2017, 4, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Omine, K.; Li, J.; Flemmy, S.O. Feasibility Study of Low-Environmental-Load Methods for Treating High-Water-Content Waste Dredged Clay (WDC)—A Case Study of WDC Treatment at Kumamoto Prefecture Ohkirihata Reservoir in Japan. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horpibulsuk, S.; Rachan, R.; Suddeepong, A. Assessment of Strength Development in Blended Cement Admixed Bangkok Clay. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoobanpot, N.; Jamsawang, P.; Poorahong, H.; Jongpradist, P.; Likitlersuang, S. Multiscale Laboratory Investigation of the Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of Dredged Sediments Stabilized with Cement and Fly Ash. Eng. Geol. 2020, 267, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chompoorat, T.; Likitlersuang, S.; Sitthiawiruth, S.; Komolvilas, V.; Jamsawang, P.; Jongpradist, P. Mechanical Properties and Microstructures of Stabilised Dredged Expansive Soil from Coal Mine. Geomech. Eng. 2021, 25, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- Rakshith, S.; Singh, D.N. Utilization of dredged sediments: contemporary issues. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2017, 143, 04016025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimsiri, S. Feasibility Study of Improvement of Dredge Soil Properties by Geopolymer for Use as Highway Material. Res. Rep. 2018, Burapha University, Chonburi, Thailand.

- Karawek, S.; Khonthon, S.; Intarapadung, A.; Thiamtham, T. Development of Mixed Bodies from Water Treatment Sludge for Pottery. Phranakhon Rajabhat Res. J. Sci. Technol. 2019, 14, 117–136. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Du, H.; Li, F.; Su, H.; Bhat, S.A.; Hudori, H.; Rosadi, M.Y. Effect of Adding Drinking Water Treatment Sludge on Excess Activated Sludge Digestion Process. Sustainability 2020, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Pollution Control. Announcement of the Department of Pollution Control, Criteria for the Quality of Seabed Sediments. Dated October 9, 2015.

- Katsumi, T.; Inui, T.; Yasutaka, T.T. Towards Sustainable Soil Management—Reuse of Excavated Soils with Natural Contamination. In Proceedings of the 8th International Congress on Environmental Geotechnics (ICEG 2018); Environmental Science and Engineering, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 35–42. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.D.; Reddy, K.R. Geoenvironmental Engineering: Site Remediation, Waste Containment, and Emerging Waste Management Technologies; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Åhnberg, H.; Holmén, M. Assessment of Stabilised Soil Strength with Geophysical Methods. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Ground Improv. 2011, 164, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimond-Barret, A.; Nauleau, E.; Le Kouby, A.; Pantet, A.; Reiffsteck, P.; Martineau, F. Free–Free Resonance Testing of In Situ Deep Mixed Soils. Geotech. Test. J. 2012, 36, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiprakaikeow, A.; Soponpong, C.; Sukolrat, J. Development of a Quality Control Index of Cement Stabilized Road Structures Using Shear Wave Velocity. In Proceedings of the 2nd World Congress on Civil, Structural, and Environmental Engineering (CSEE’17), Barcelona, Spain, 2017.

- Ryden, N.; Ekdahl, U.; Lindh, P. Quality Control of Cement Stabilized Soil Using Non-Destructive Seismic Tests. In Conference Proceedings: Advanced Testing of Fresh Cementitious Materials; 2006; pp. 3–4.

- American Society for Testing and Materials. ASTM D 2166, D 2166M: Standard Test Method for Unconfined Compressive Strength of Cohesive Soil; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Highway. Road Construction Supervision, Manual for Construction Supervision of Highways, Vol. 2; Bangkok, Thailand, 2007. (In Thai).

- Yang, K.H.; Cho, A.R.; Song, J.K.; Nam, S.H. Hydration Products and Strength Development of Calcium Hydroxide-Based Alkali-Activated Slag Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 29, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nontananandh, S.; Boonyong, S.; Yoobanpot, T.; Chantawarangul, K. Strength Development of Soft Marine Clay Stabilized with Cement and Fly Ash. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2004, 38, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Chompoorat, T.; Maikhun, T.; Likitlersuang, S. Cement Improved Lake Bed Sedimentary Soil for Road Construction. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Ground Improv. 2019, 172, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Highways. Standard No. DH-S 206/2564: Soil Cement Subbase; Bureau of Highway Standard and Evaluation: Bangkok, Thailand, 2021. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Yoobanpot, N.; Jamsawang, P.; Simarat, P.; Jongpradist, P.; Likitlersuang, S. Sustainable Reuse of Dredged Sediments as Pavement Materials by Cement and Fly Ash Stabilization. J. Soils Sediments 2020, 20, 3807–3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chompoorat, T.; Thepumong, T.; Taesinlapachai, S.; Likitlersuang, S. Repurposing of Stabilised Dredged Lakebed Sediment in Road Base Construction. J. Soils Sediments 2021, 21, 2719–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cai, G.; Cheeseman, C.; Li, J.; Poon, C.S. Sewage sludge ash-incorporated stabilisation/solidification for recycling and remediation of marine sediments. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 301, 113877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmi, D.; Serati, M.; Williams, D.J.; Qasim, S.; Cheng, Y.P. The potential use of crushed waste glass as a sustainable alternative to natural and manufactured sand in geotechnical applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (a) Physical properties | |||||

| Properties | Seabed dredged sludge (SS) | Water treatment sludge (WS) | |||

| Specific gravity | 2.67 - 2.72 | 2.58 | |||

| Natural water content (%) | 200 - 300 | 120 - 150 | |||

| Liquid limit (%) | 99.64 - 101.69 | 58.7 | |||

| Plastic limit (%) | 35.81 - 37.95 | 53.8 | |||

| Plastic index | 63.79 | 4.9 | |||

| Soil classification (AASHTO) | A-7-5 (20) | A-7-5 (20) | |||

| Soil classification (USCS) | CH | MH | |||

| (b) Chemical compositions | |||||

| Oxide component | SS [17] | WS [18] | WS [2] | ||

| SiO2 | 63.56 | 56.30 | 57.30 | ||

| Al2O3 | 22.19 | 28.60 | 26.74 | ||

| Fe2O3 | 3.67 | 7.78 | 8.58 | ||

| K2O | 3.04 | 2.15 | 1.95 | ||

| CaO | 1.02 | 1.18 | 1.25 | ||

| MgO | 1.34 | 1.24 | 1.34 | ||

| P2O5 | - | 0.91 | 0.36 | ||

| TiO2 | - | 0.89 | 0.91 | ||

| SO3 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 1.16 | ||

| MnO | - | 0.19 | 0.23 | ||

| Na2O | 2.07 | 0.36 | - | ||

| LOI | - | 0.17 | - | ||

| Cl | 1.68 | - | 0.07 | ||

| Sample | Element ratio | Remarks: Mixing condition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 days | 7 days | 14 days | Cement content (kg/m3) | Initial water content (%) | w/c ratio | ||

| WSC-1 | Si/Ca | 2.84 | 1.71 | 3.38 | 150 | 128.5 | 7.73 |

| S/Ca | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.32 | ||||

| Al/Ca | 2.32 | 1.70 | 2.77 | ||||

| WSC-2 | Si/Ca | 1.99 | 1.95 | 7.44 | 200 | 128.5 | 5.80 |

| S/Ca | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Al/Ca | 1.15 | 1.56 | 7.20 | ||||

| WSC-3 | Si/Ca | 3.30 | 3.94 | 6.67 | 250 | 128.5 | 4.64 |

| S/Ca | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||

| Al/Ca | 2.19 | 1.96 | 5.70 | ||||

| WSC-4 | Si/Ca | 3.75 | 7.12 | - | 150 | 46.0 | 3.07 |

| S/Ca | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | ||||

| Al/Ca | 2.38 | 5.02 | - | ||||

| WSC-5 | Si/Ca | 3.69 | 5.19 | - | 200 | 46.0 | 2.30 |

| S/Ca | 0.00 | 0.16 | - | ||||

| Al/Ca | 3.29 | 3.84 | - | ||||

| WSC-6 | Si/Ca | 4.42 | 12.05 | - | 250 | 46.0 | 1.84 |

| S/Ca | 0.00 | 0.00 | - | ||||

| Al/Ca | 3.32 | 9.61 | - | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).