Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 81P40

1. Introduction

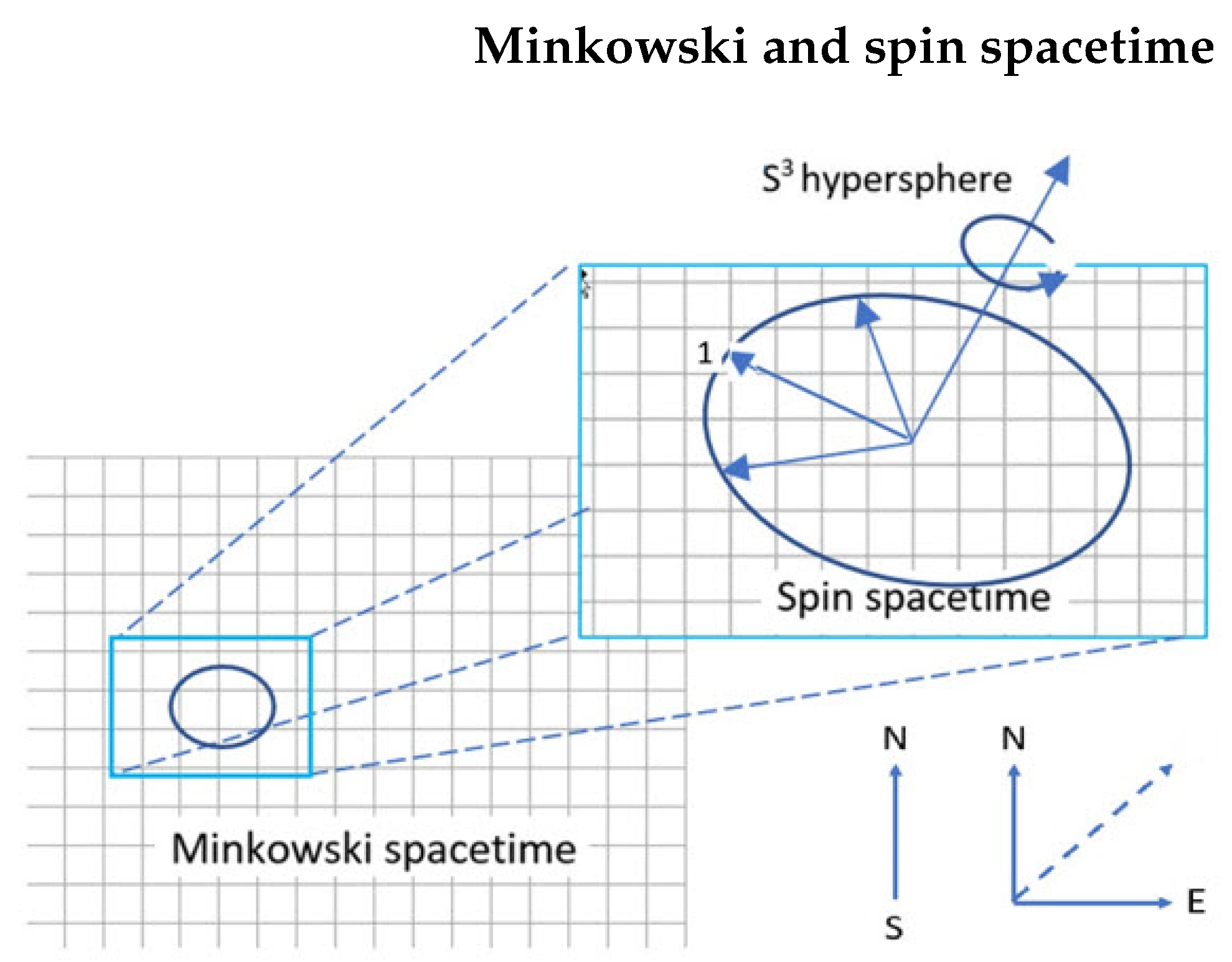

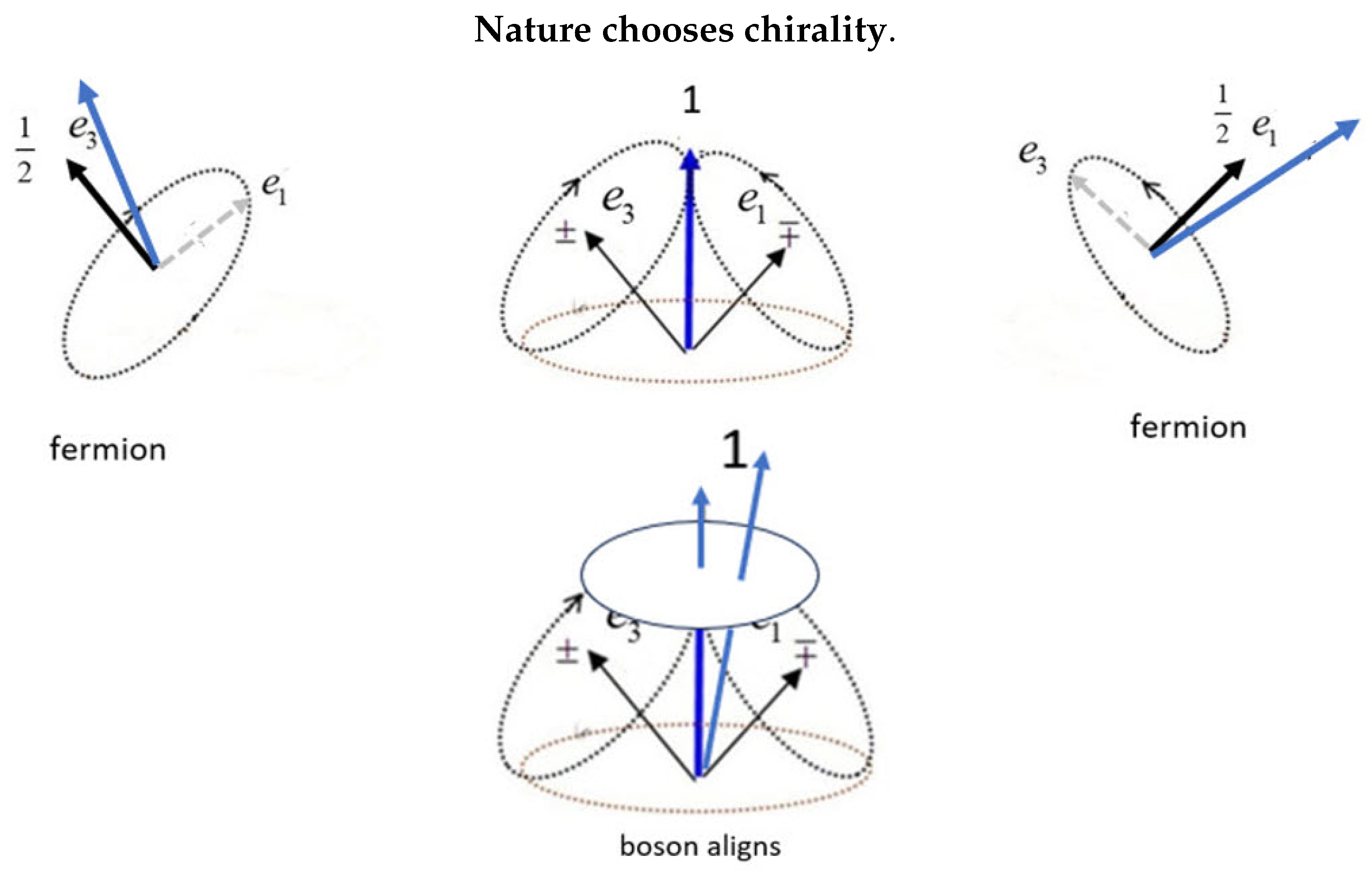

2. Quaternion Spin

2.1. The Complex Dirac Field

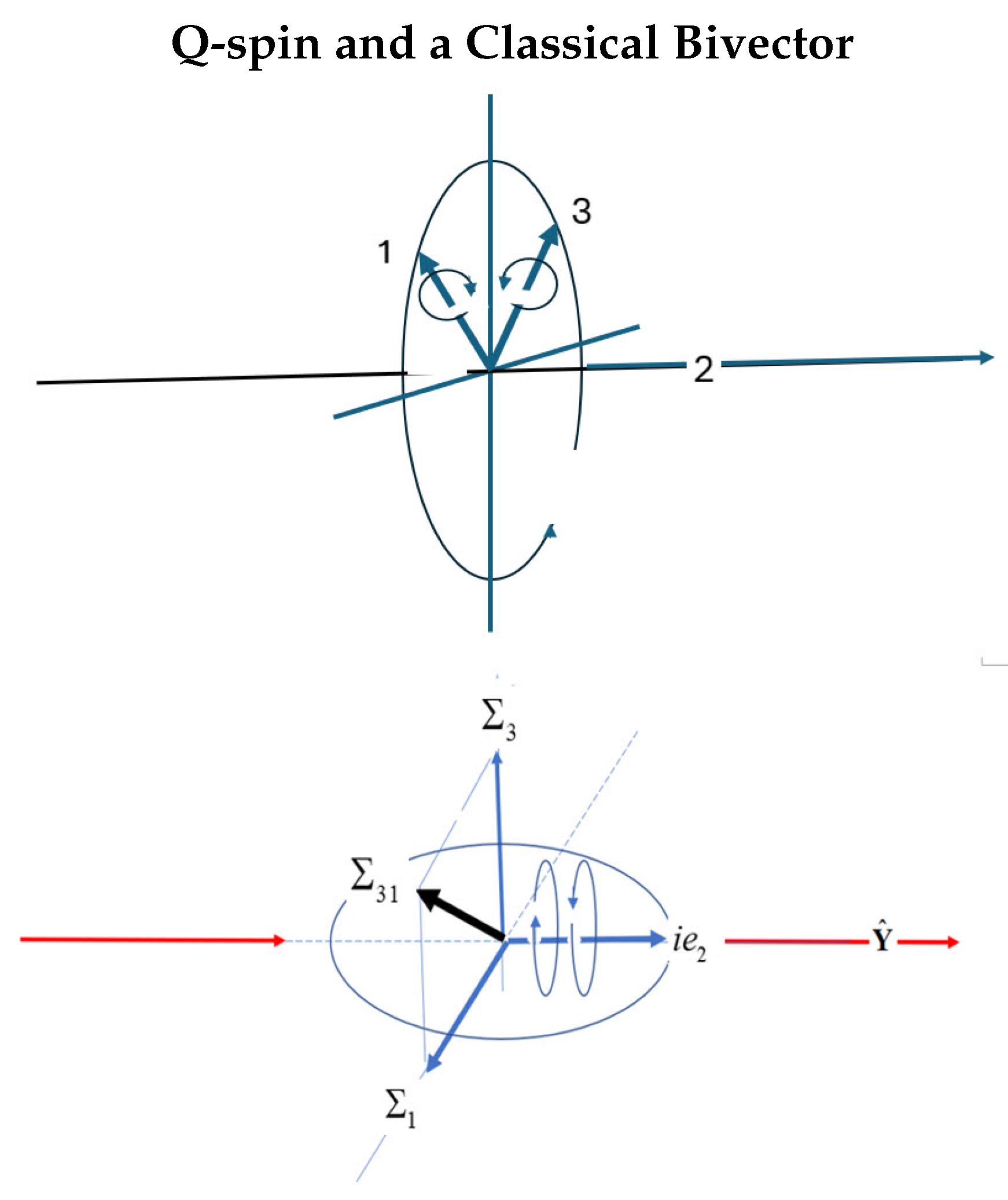

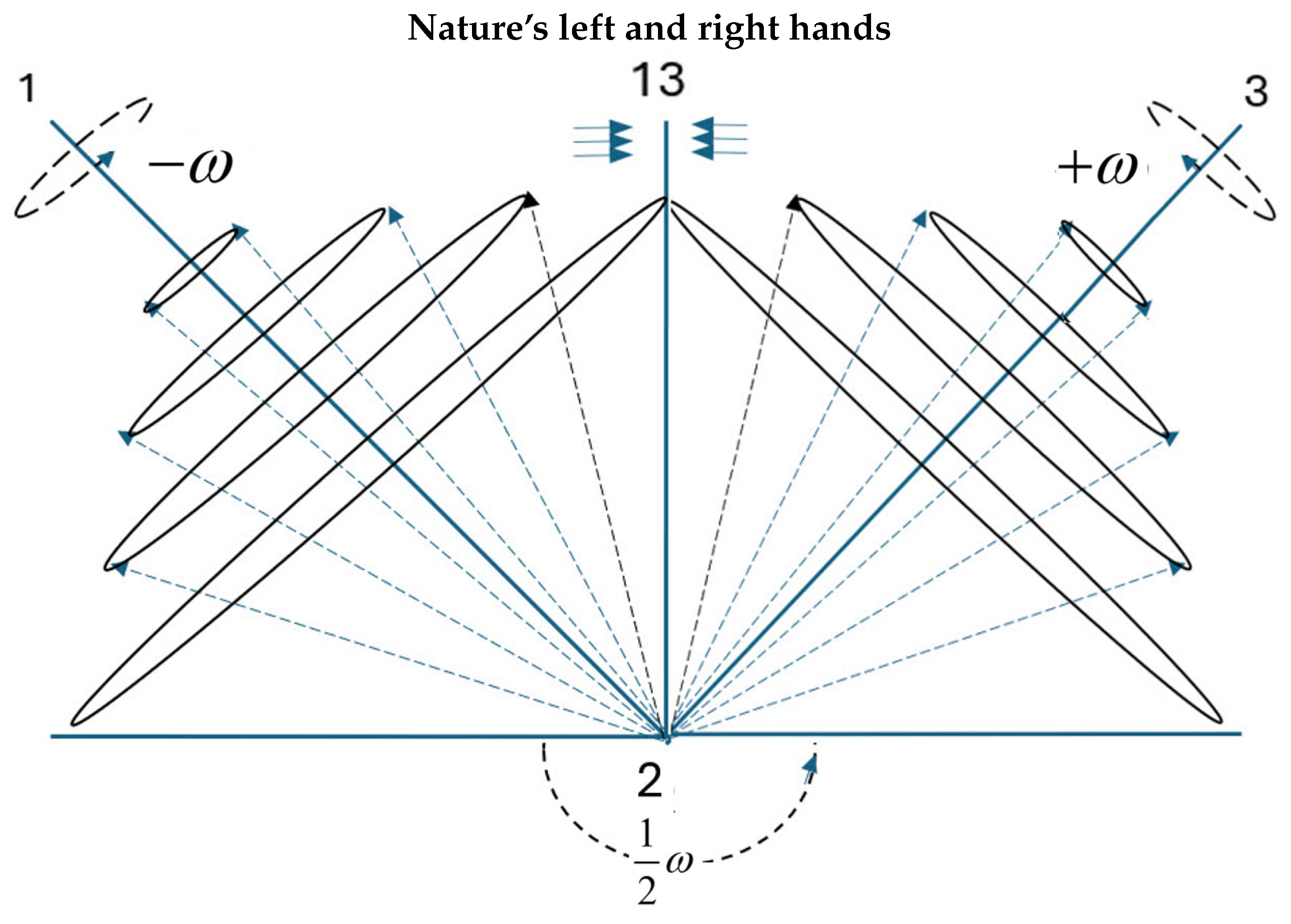

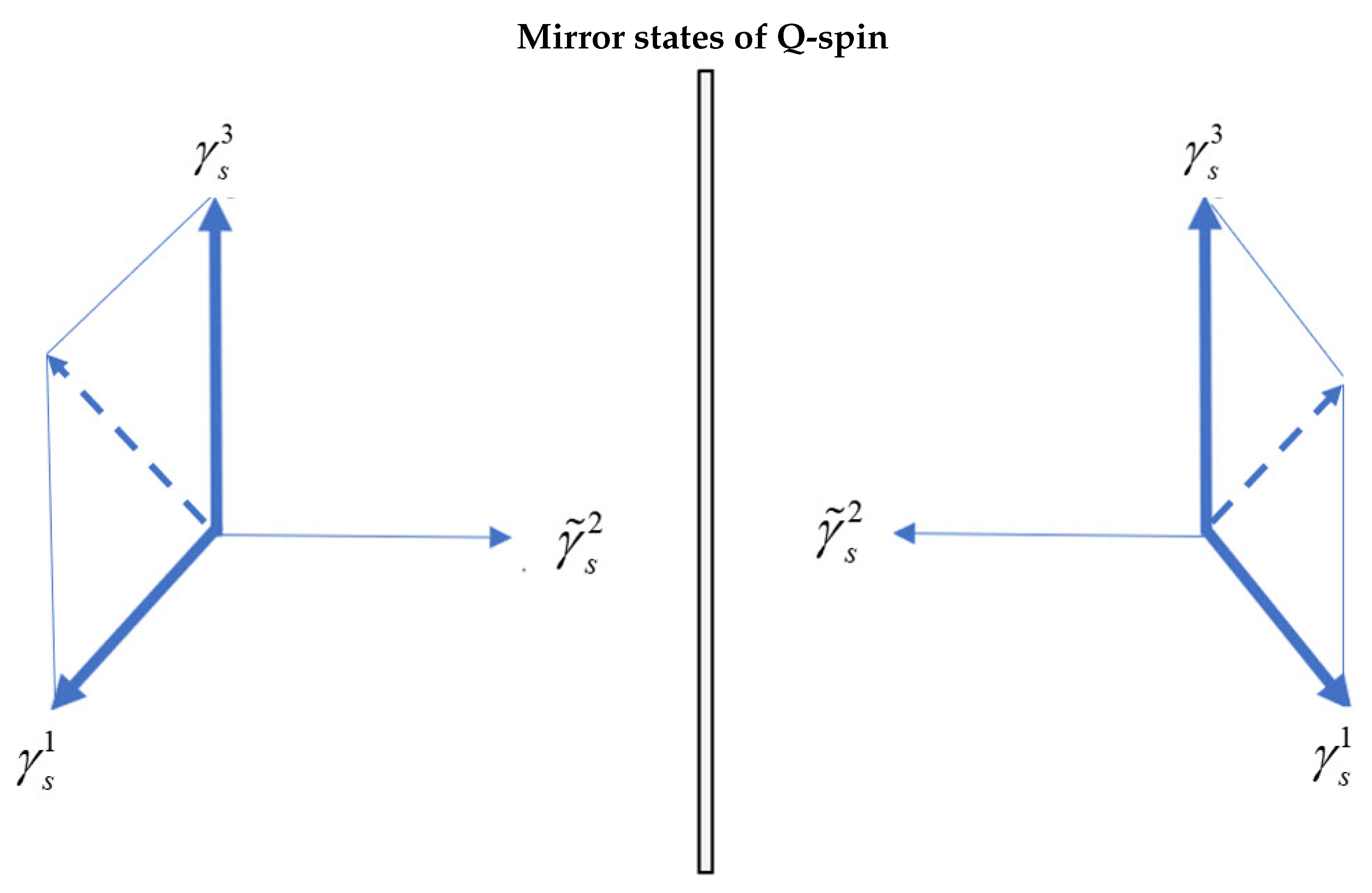

2.2. Symmetry and Q-Spin

2.3. One Particle, Not Two

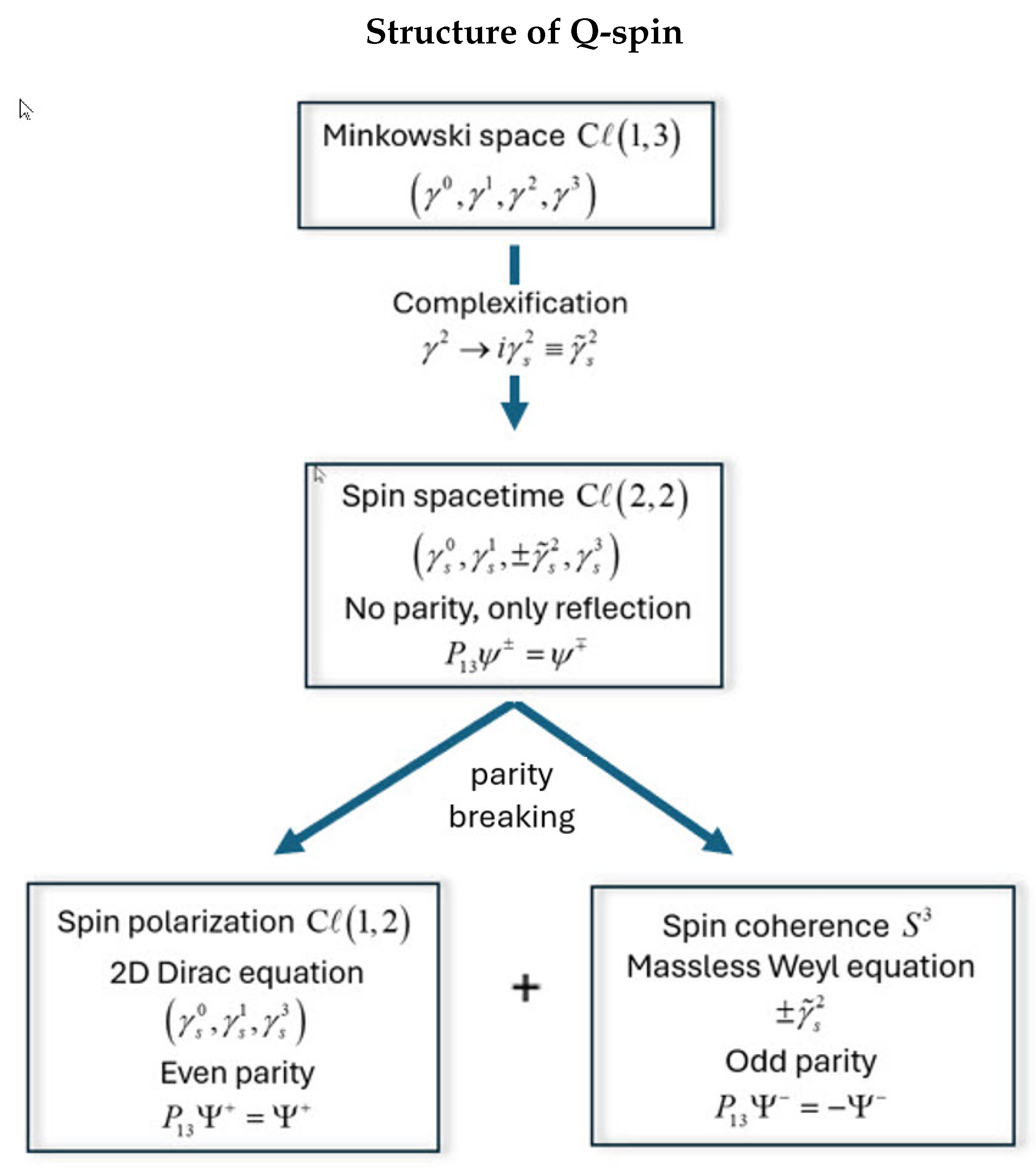

2.4. Q-Spin Structure

3. Definition of Q-Spin

3.1. The Composite Boson

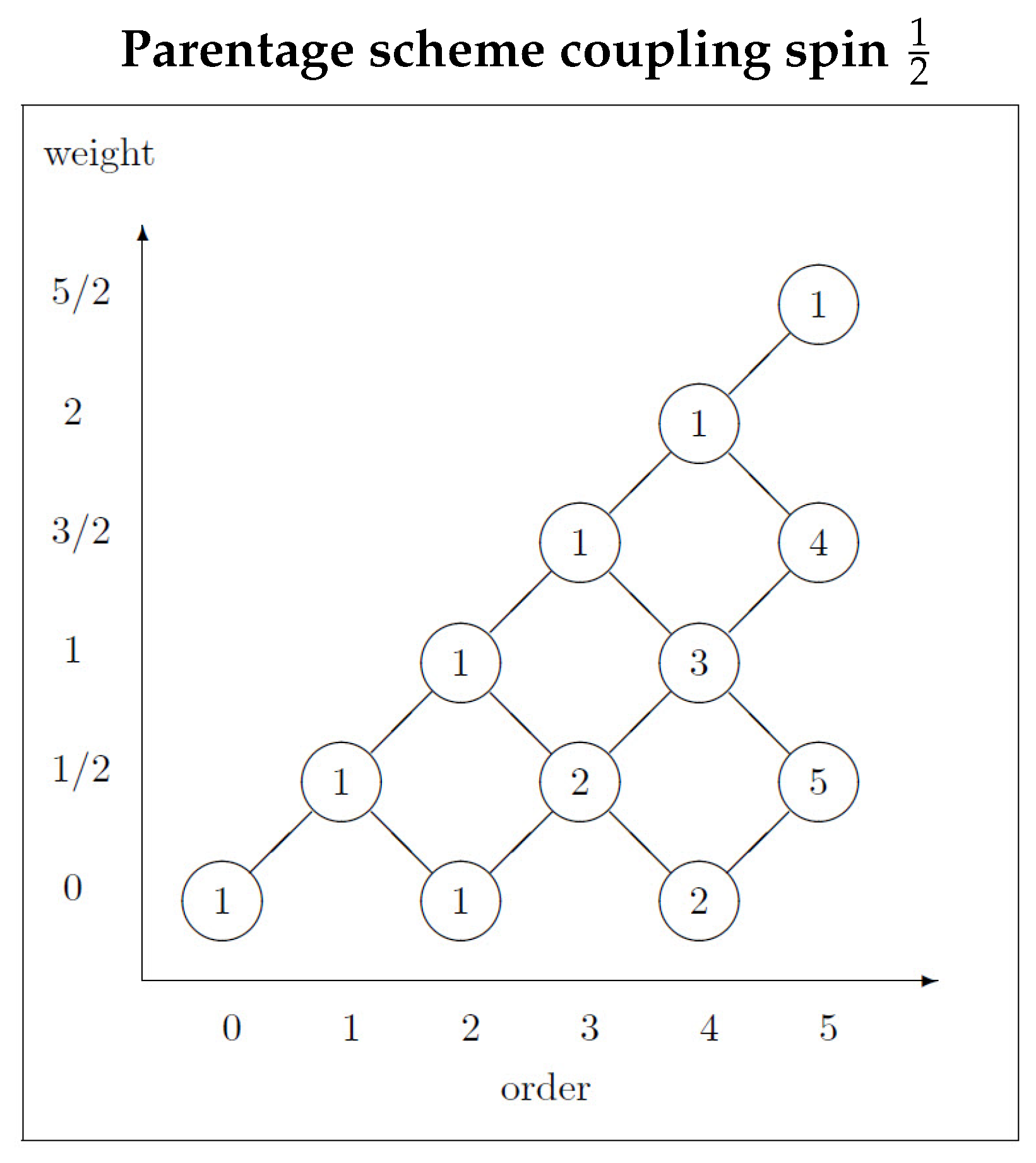

3.2. Higher Spins

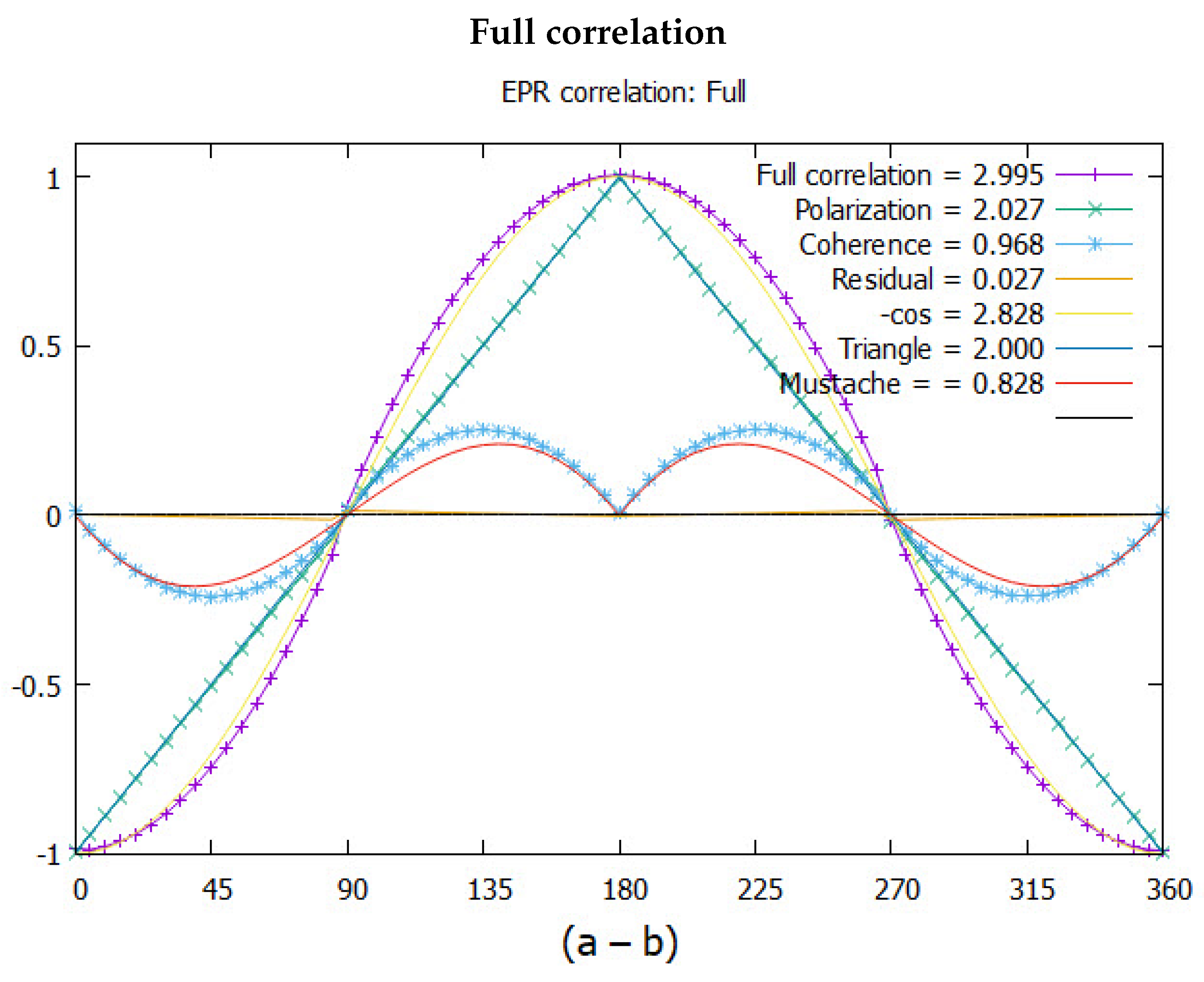

4. Q-Spin Example: The EPR Paradox

4.1. Helicity Disproves Bell’s Theorem

4.2. EPR Correlation Using Quaternions

5. Weyl Solutions

6. Massless Limit

7. Comparison with a Photon

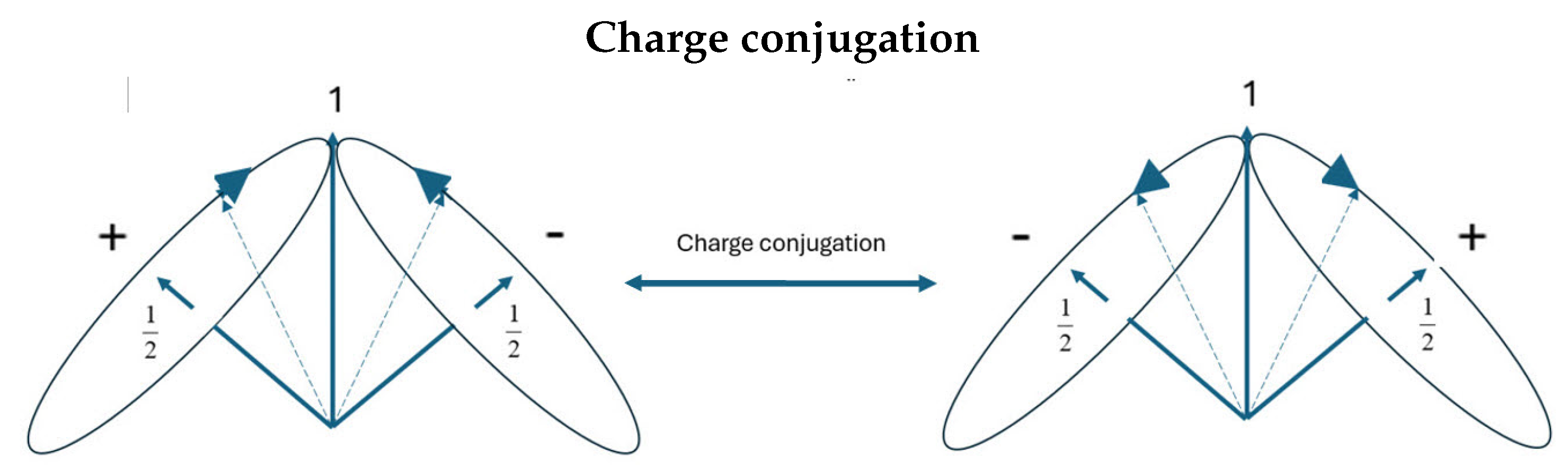

8. Dirac: No Antimatter

8.1. Baryogenesis

9. Conclusions

Appendix A

References

- Sanctuary, B. Quaternion Spin. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. Spin Helicity and the Disproof of Bell’s Theorem. Quantum Rep. 2024, 6, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. C. , Non-local EPR Correlations using Quaternion Spin. Quantum Rep. 2024, 6(3), 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanctuary, B. The classical origin of intrinsic angular momentum, submitted, 2024.

- Sanctuary, B. Quaternion spin: parity and beta decay, 2025.

- Sanctuary, B. Bell’s theorem and hidden variables, 2025.

- Sanctuary, B. Quantum coherence 2025.

- Sanctuary, B. The singlet state is an approximation. 2025.

- Clauser, J. F., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A., & Holt, R. A. (1969). Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Physical review letters, 23(15), 880. [CrossRef]

- Aspect, Alain, Jean Dalibard, and Gérard Roger. “Experimental test of Bell’s inequalities using time-varying analyzers.” Physical review letters 49.25 (1982): 1804.Aspect, Alain (15 October 1976). “Proposed experiment to test the non separability of quantum mechanics”. Physical Review D. 14 (8): 1944–1951. [CrossRef]

- Weihs, G., Jennewein, T., Simon, C., Weinfurter, H., Zeilinger, A. (1998). Violation of Bell’s inequality under strict Einstein locality conditions. Physical Review Letters, 81(23), 5039. [CrossRef]

- Bell, John S. "On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox." Physics Physique Fizika 1.3 (1964): 195.

- Wikipedia contributors. (2024, July 12). Pauli matrices. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 12:06, August 15, 2024.

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1928). The quantum theory of the electron. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character, 117(778), 610-624. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, Roger. "Twistor algebra." Journal of Mathematical Physics 8.2 (1967): 345-366. [CrossRef]

- Penrose, Roger. "Solutions of the Zero-Rest-Mass Equations." Journal of Mathematical Physics 10.1 (1969): 38-39. [CrossRef]

- Wilczek, F. (1982). Quantum mechanics of fractional-spin particles. Physical review letters, 49(14), 957. [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M., Kitaev, A., Larsen, M., and Wang, Z. (2003). Topological quantum computation. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 40(1), 31-38.

- Kauffman, L. H., and Lomonaco, S. J. (2004). Braiding operators are universal quantum gates. New Journal of Physics, 6(1), 134. [CrossRef]

- Hestenes, D., and Sobczyk, G. (2012). Clifford algebra to geometric calculus: a unified language for mathematics and physics (Vol. 5). Springer Science and Business Media.

- Doran, C., Lasenby, J., (2003). Geometric algebra for physicists. Cambridge University Press.

- Peskin, M.; Schroeder, D.V. An Introduction To Quantum Field Theory; Frontiers in Physics: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995.

- Edmonds, A. R. (1957). Angular Momentum in Quantum Mechanics. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07912-7.

- Coope, J. A. R., Snider, R. F., and McCourt, F. R. (1965). Irreducible cartesian tensors. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 43(7), 2269-2275. [CrossRef]

- Coope, J. A. R., and Snider, R. F. (1970). Irreducible cartesian tensors. II. General formulation. Journal of Mathematical Physics, 11(3), 1003-1017. [CrossRef]

- Coope, J. A. R. (1970). Irreducible Cartesian Tensors. III. Clebsch-Gordan Reduction. Journal of Mathematical Physics, 11(5), 1591-1612. [CrossRef]

- Coope, J. A. R., Sanctuary, B. C., and Beenakker, J. J. M. (1975). The influence of nuclear spins on the transport properties of molecular gases and application to HD. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 79(2), 129-170. [CrossRef]

- Snider, R. F. (2017). Irreducible Cartesian Tensors (Vol. 43). Walter de Gruyter GmbH and Co KG.

- Bell, J. S. (1987). Speakable and unspeakable in quantum mechanics Cambridge University Press. New York, Bell’s quote is on page 65.

- Tsirel’son, B. S. (1987). Quantum analogues of the Bell inequalities. The case of two spatially separated domains. Journal of Soviet Mathematics, 36, 557–570. [CrossRef]

- Dirac, P. A. M. (1930). "A Theory of Electrons and Protons". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. 126 (801): 360–365. [CrossRef]

- Conrad, J. M., & Shaevitz, M. H. (2018). Sterile neutrinos: An introduction to experiments. Adv. Ser. Direct. High Energy Phys, 28, 391-442.

- Baryon Asymmetry. In Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baryon_asymmetry (accessed on 6 April 2024).

- Riotto, A., & Trodden, M. (1999). Recent progress in Baryogenisis. Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, 49(1), 35-75.

- Steigman, G. (2007). "Primordial Nucleosynthesis in the Precision Cosmology Era". Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science, 57: 463-491. [CrossRef]

- Ade, P. A. R. et al. (Planck Collaboration) (2016). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics, 594, A13.

- Ahmadi, M.; Alves, B.X.R.; Baker, C.J.; Bertsche, W.; Butler, E.; Capra, A.; Carruth, C.; Cesar, C.L.; Charlton, M.; Cohen, S.; et al. Observation of the 1S–2S transition in trapped antihydrogen. Nature 2017, 541, 506–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E. K., Baker, C. J., Bertsche, W., Bhatt, N. M., Bonomi, G., Capra, A., ... and Wurtele, J. S. (2023). Observation of the effect of gravity on the motion of antimatter. Nature, 621(7980), 716-722. [CrossRef]

- Wick, David. The Infamous Boundary: Seven decades of heresy in quantum physics. Springer Science and Business Media, 2012.

- Wu, C. S., Ambler, E., Hayward, R. W., Hoppes, D. D., and Hudson, R. P. (1957). Experimental test of parity conservation in beta decay. Physical review, 105(4), 1413. [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. Unitary irreducible representations of SO (2, 2) and SO (3, 2).

- Maldacena, J., Susskind, L. (2013). Cool horizons for entangled black holes. Fortschritte der Physik, 61(9), 781-811. [CrossRef]

- Snygg, J. (1997). Clifford Algebra: A Computational Tool for Physicists. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Gsponer, A., Hurni, J. P. (2002). The physical heritage of Sir WR Hamilton. arXiv preprint math-ph/0201058.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).