Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

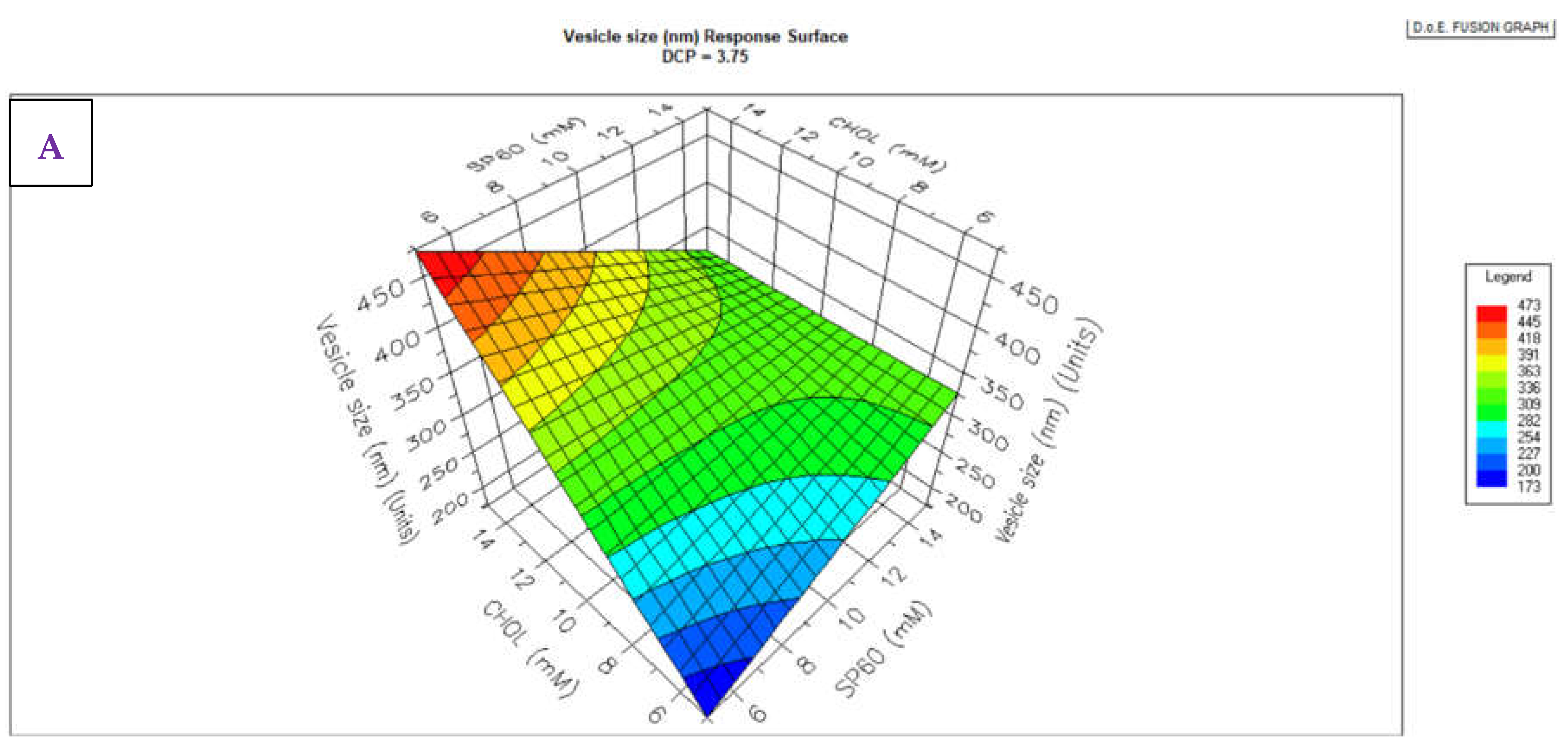

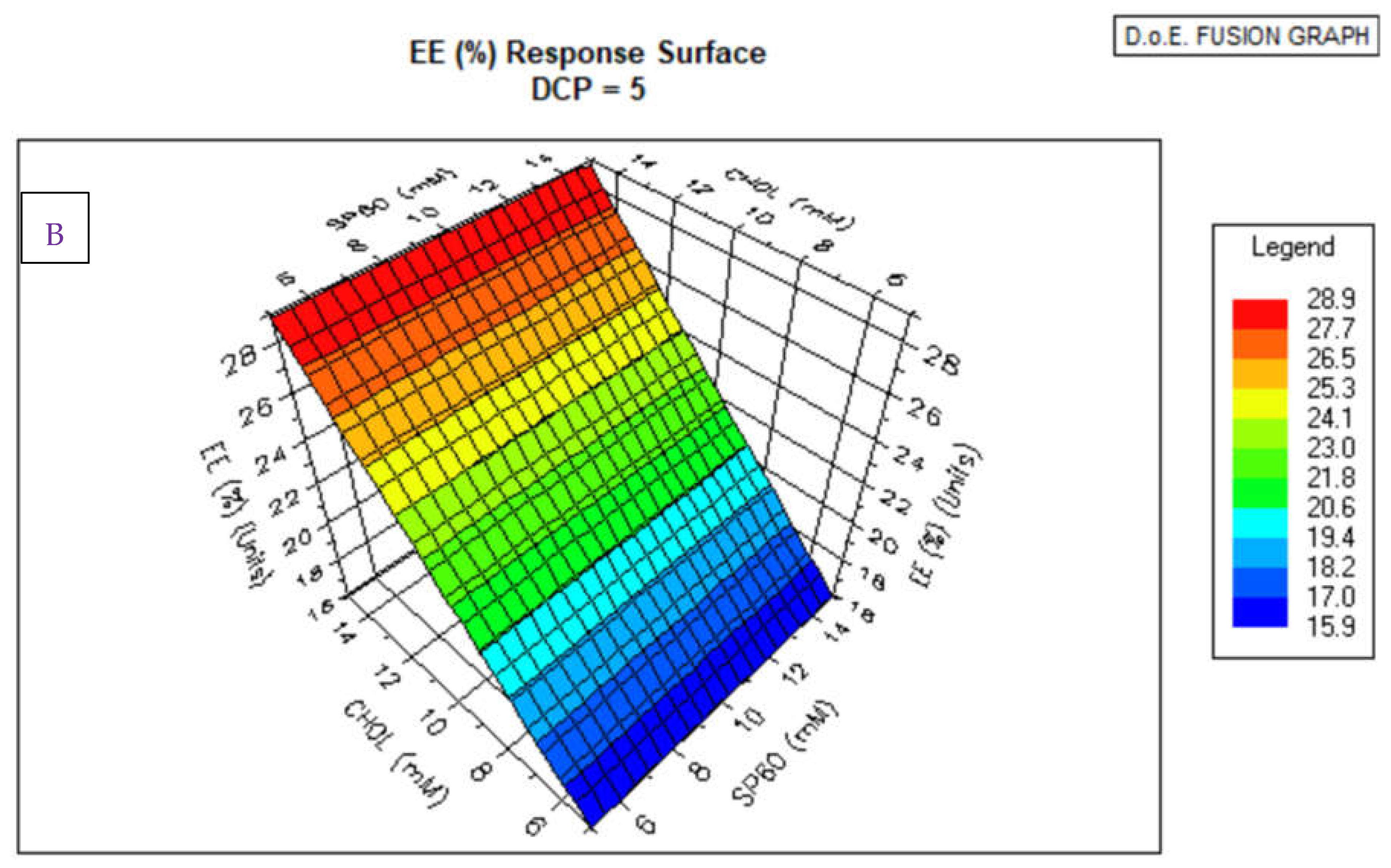

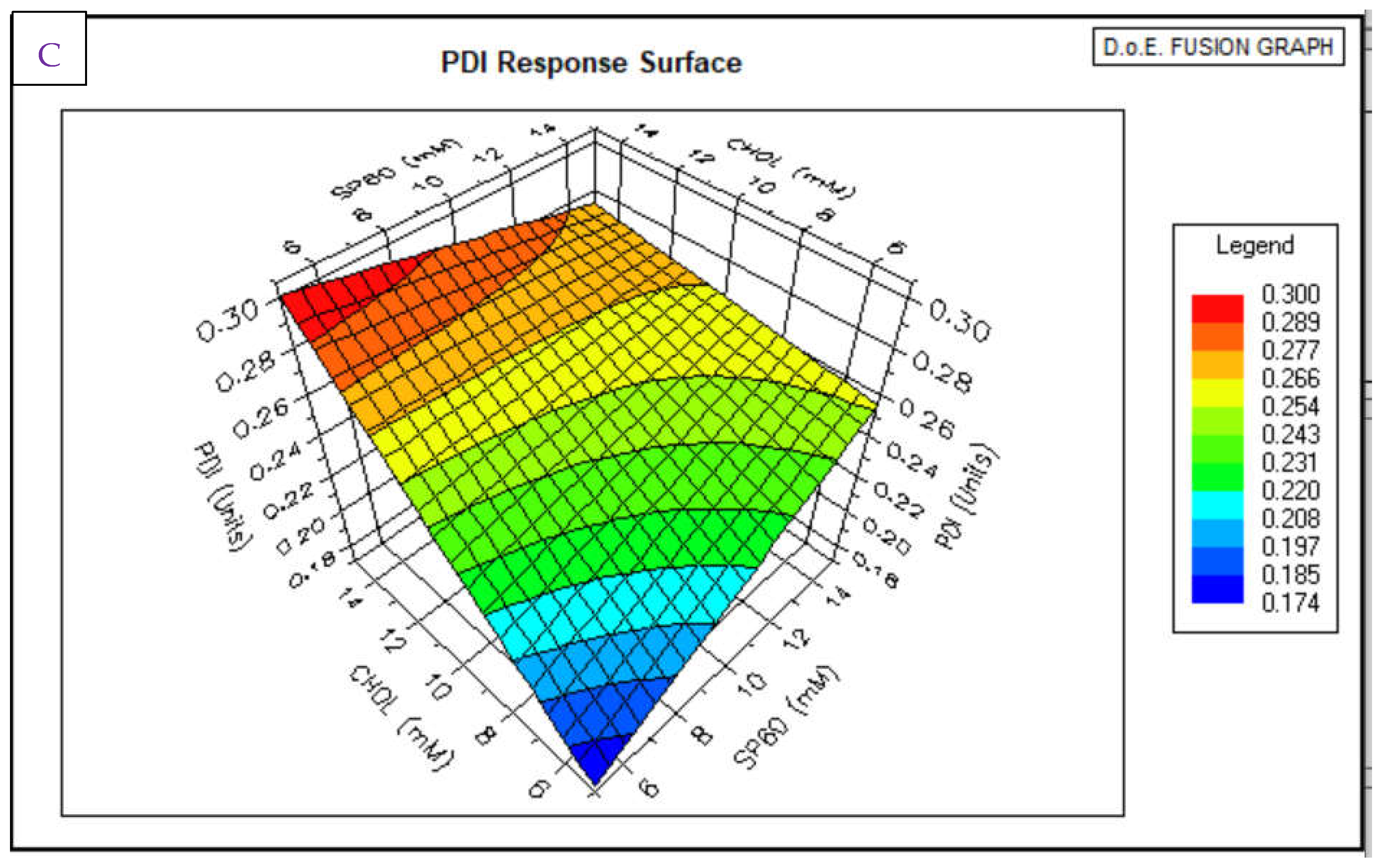

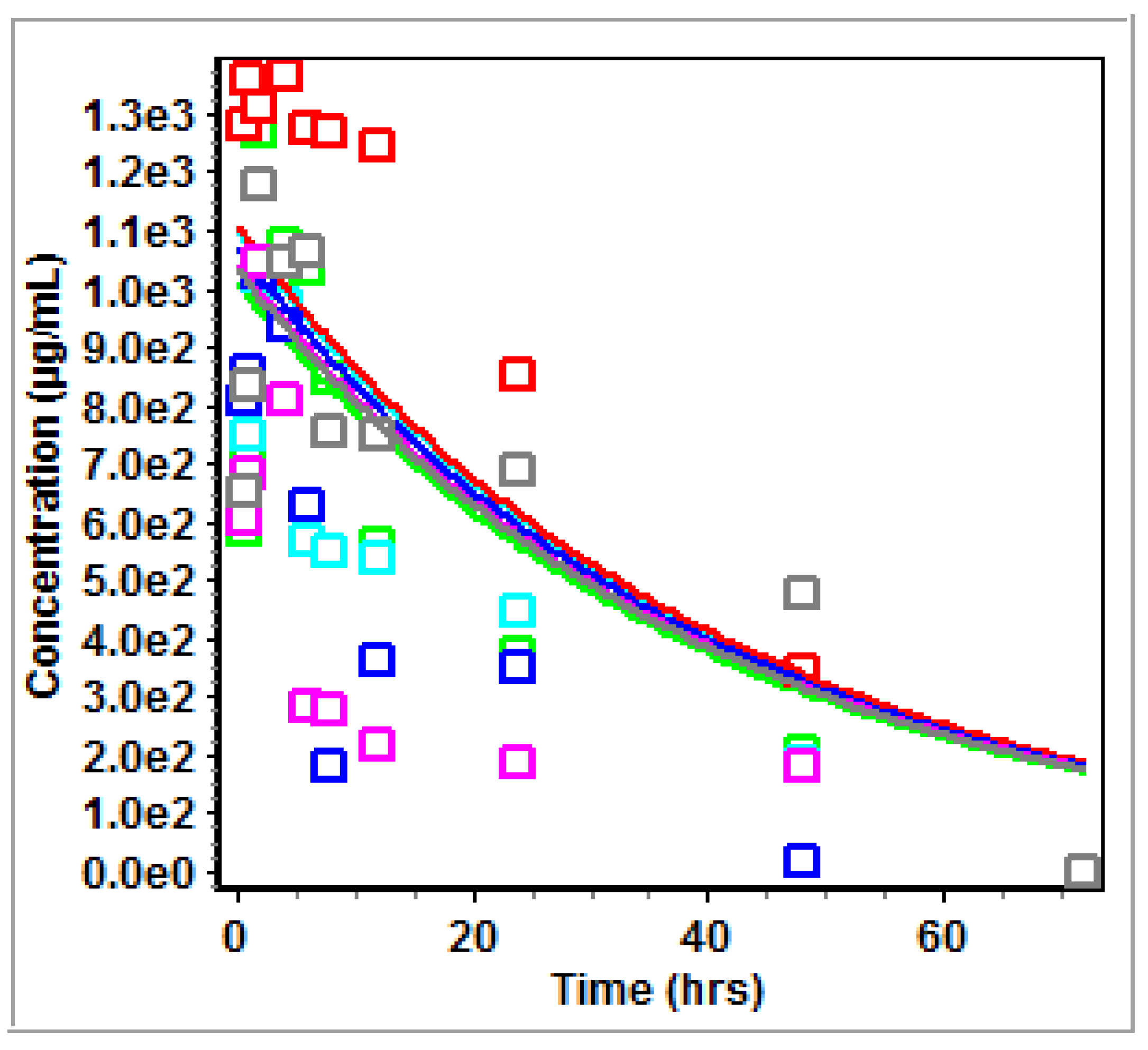

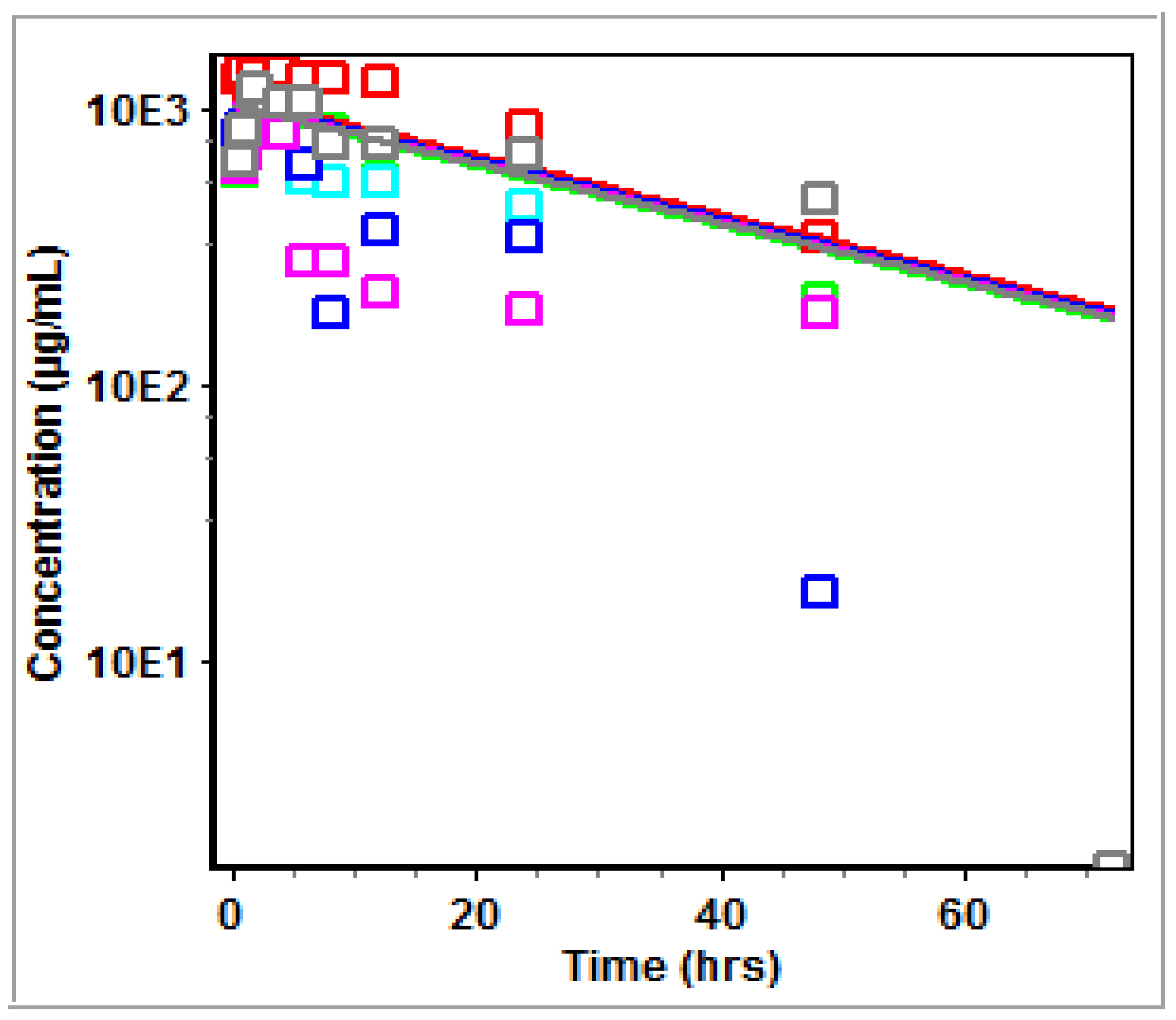

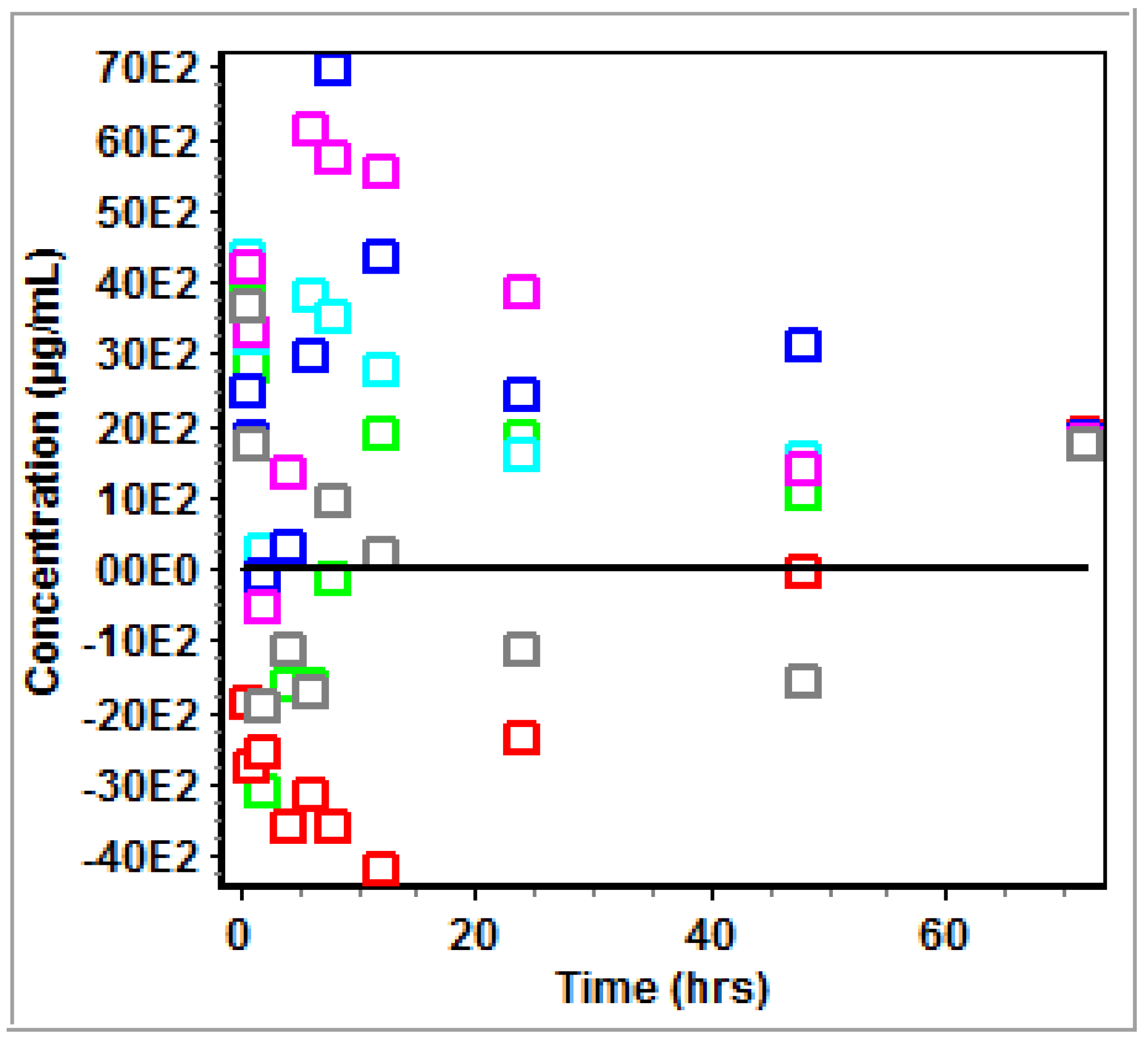

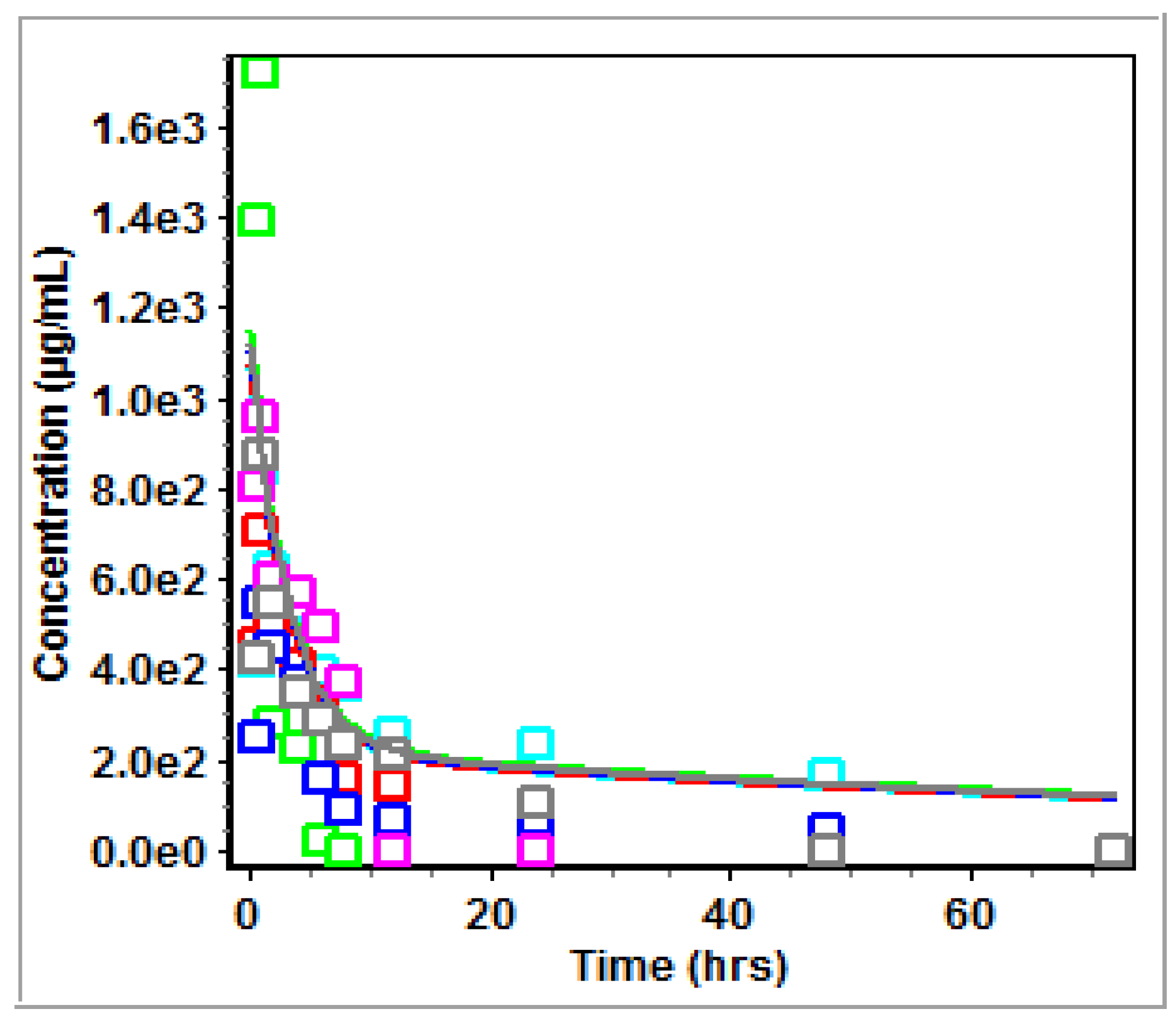

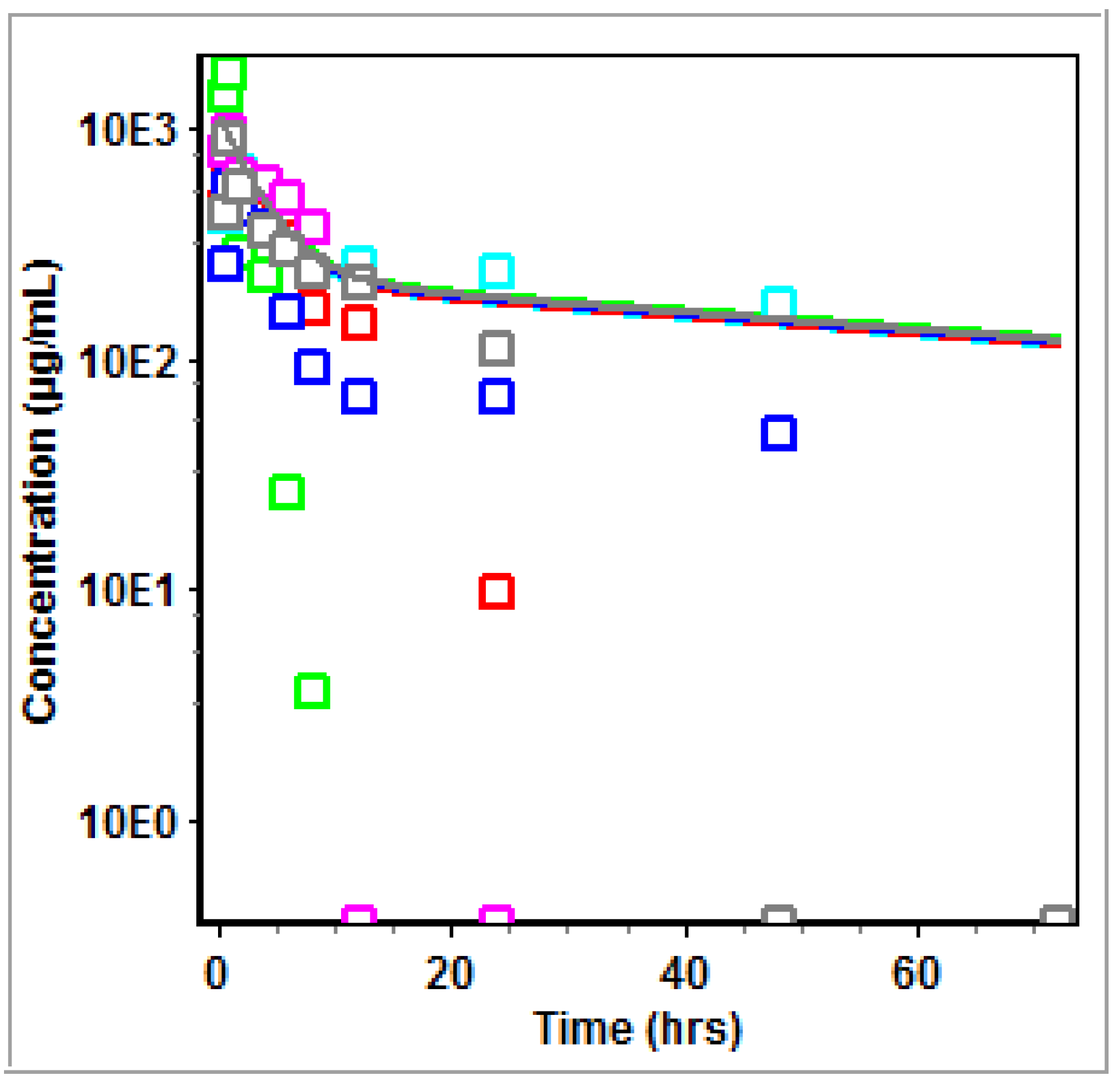

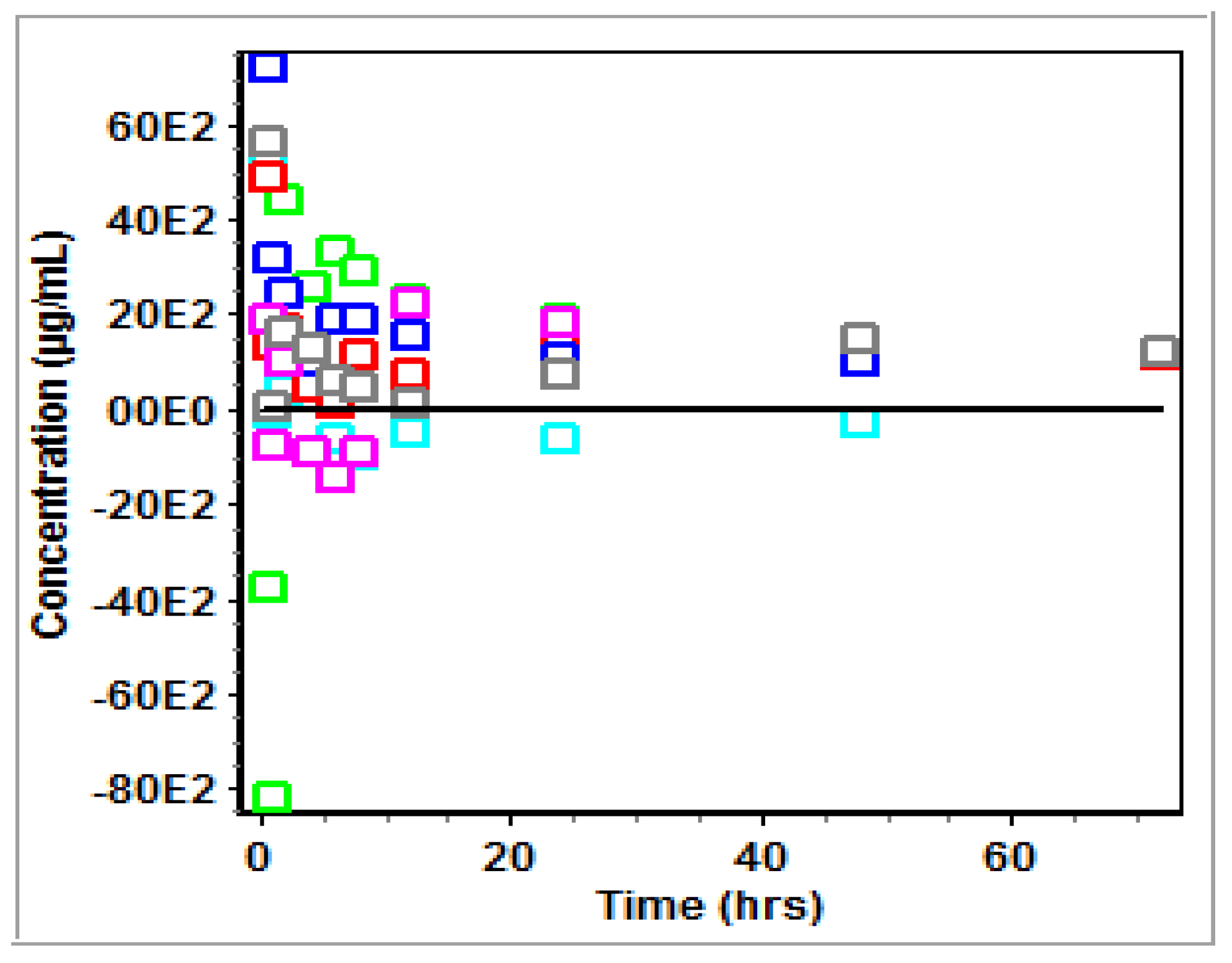

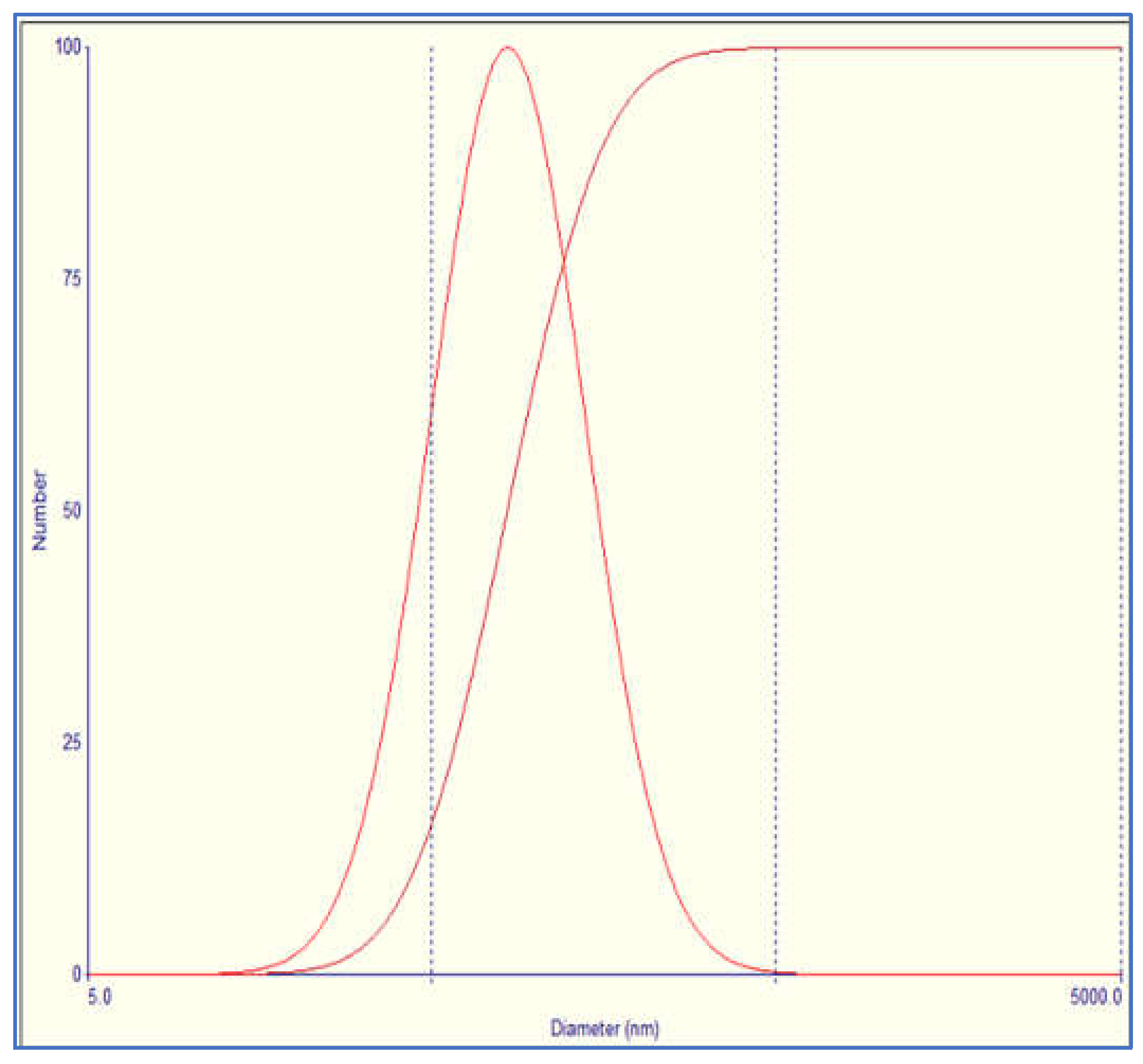

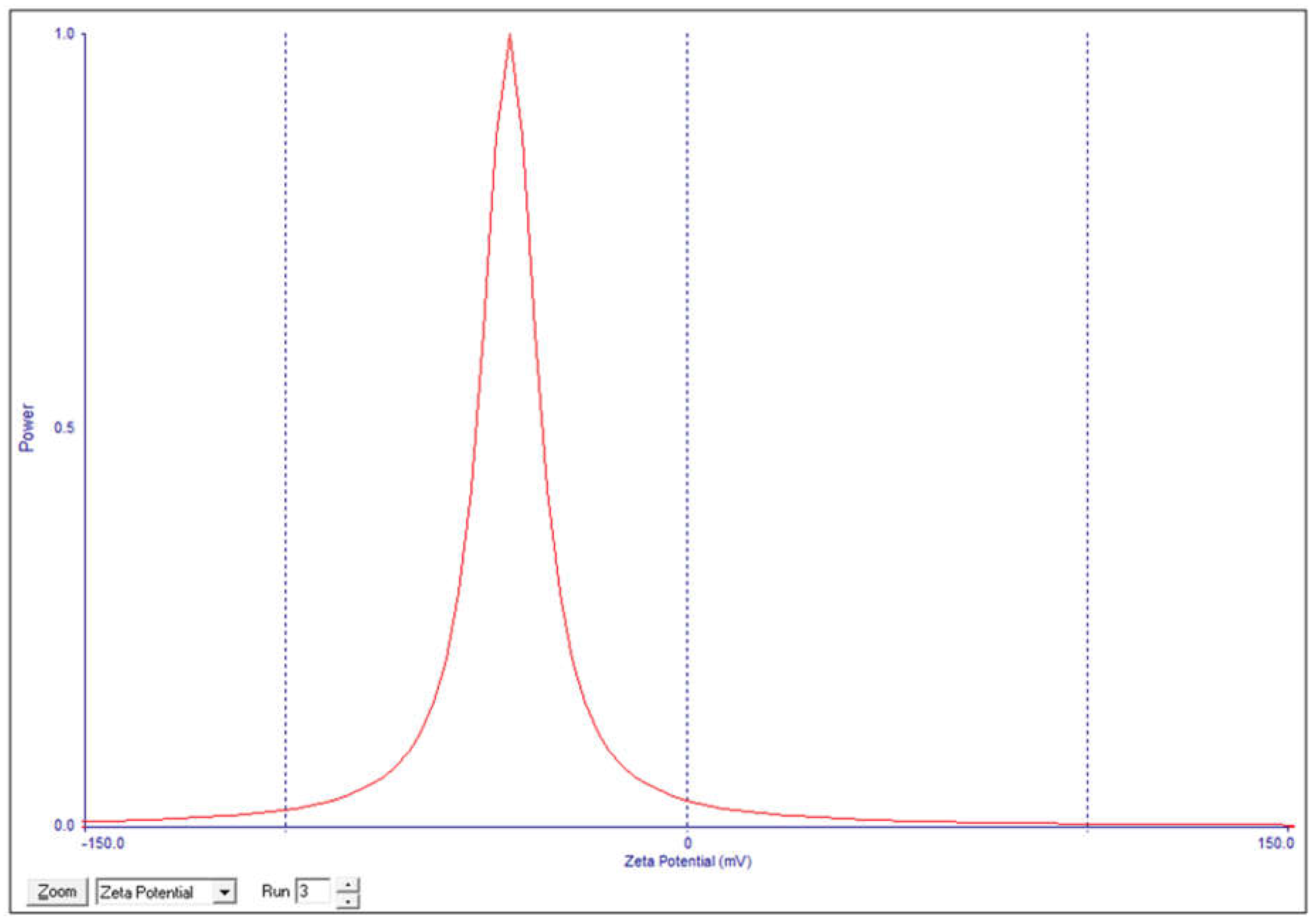

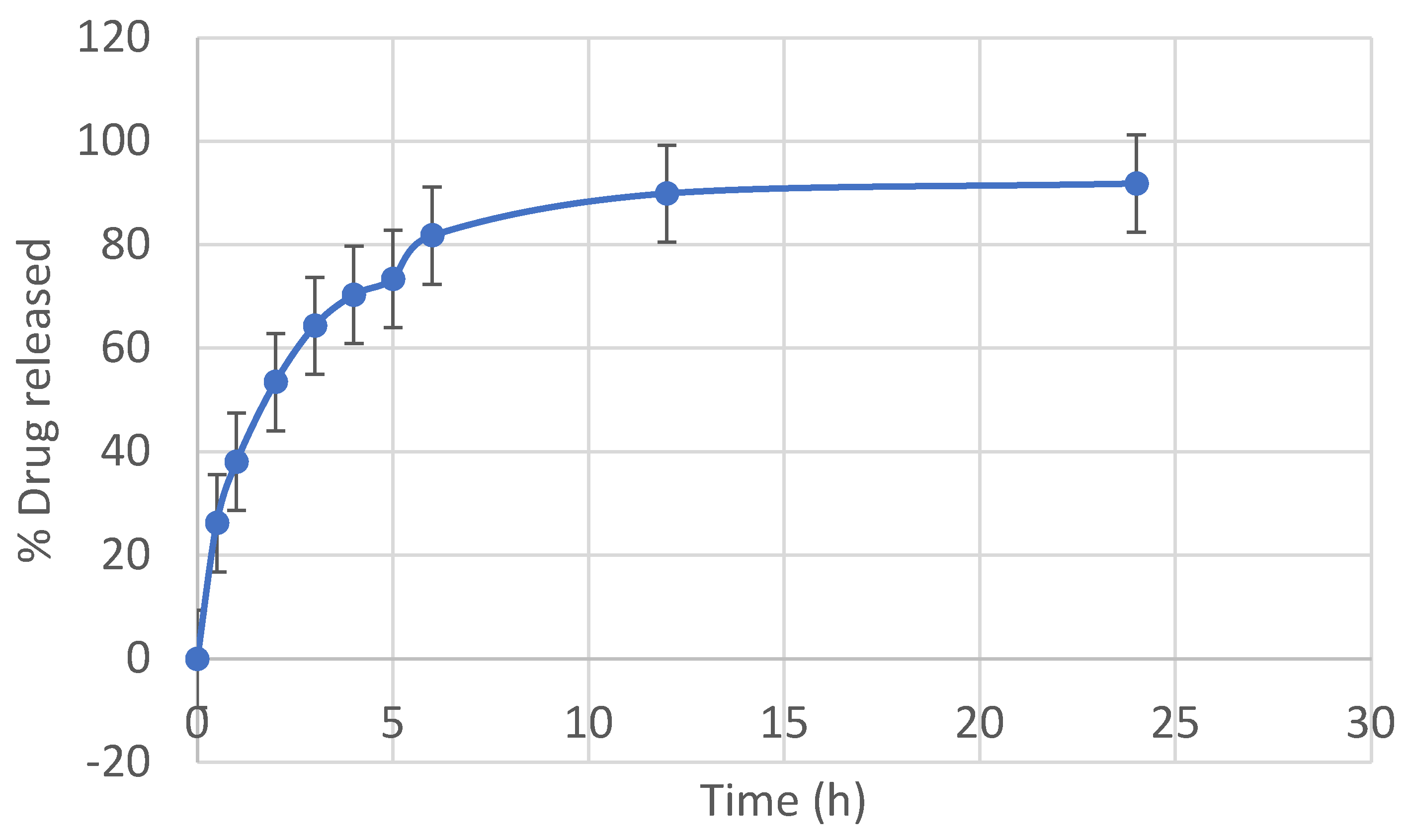

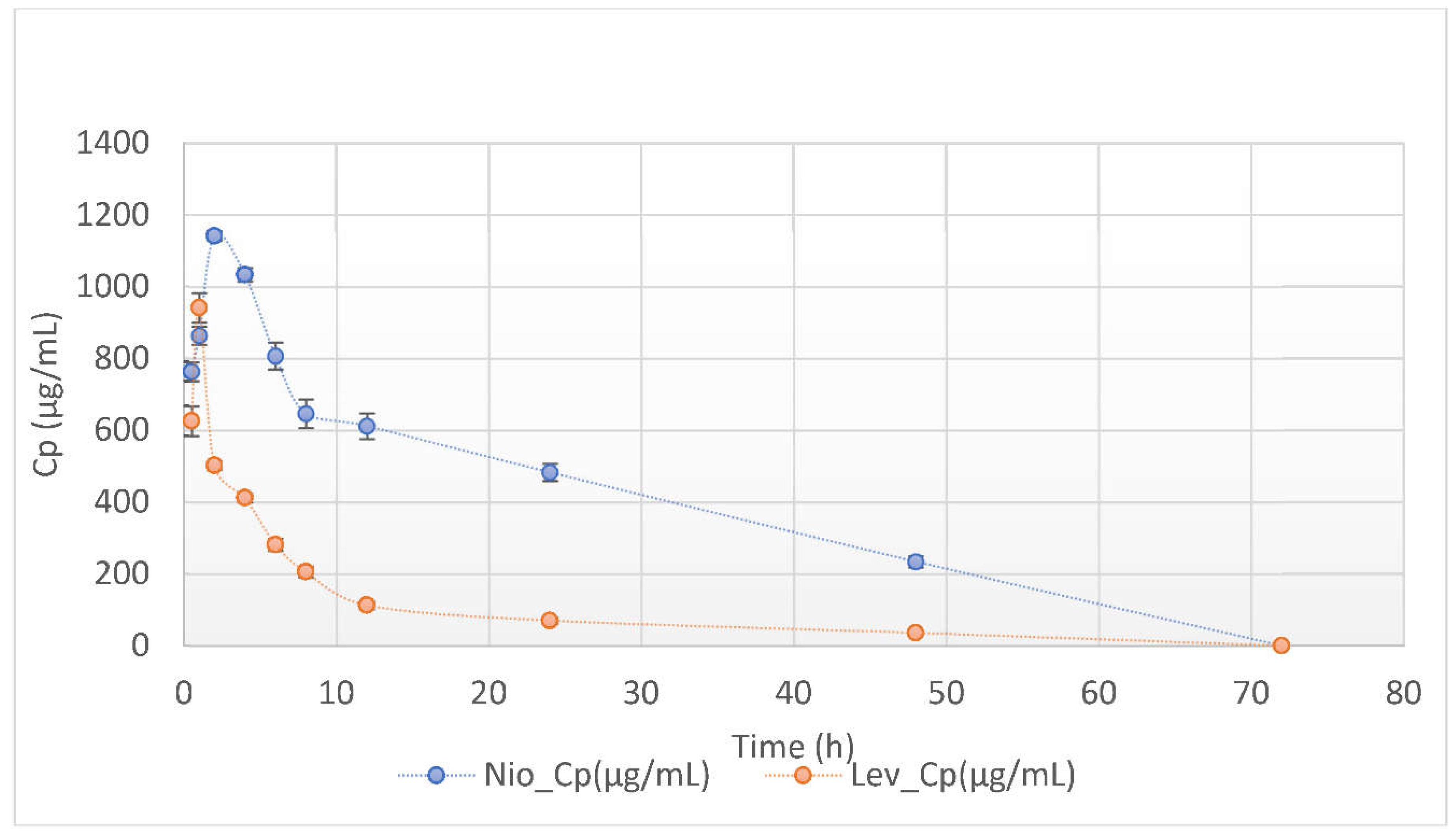

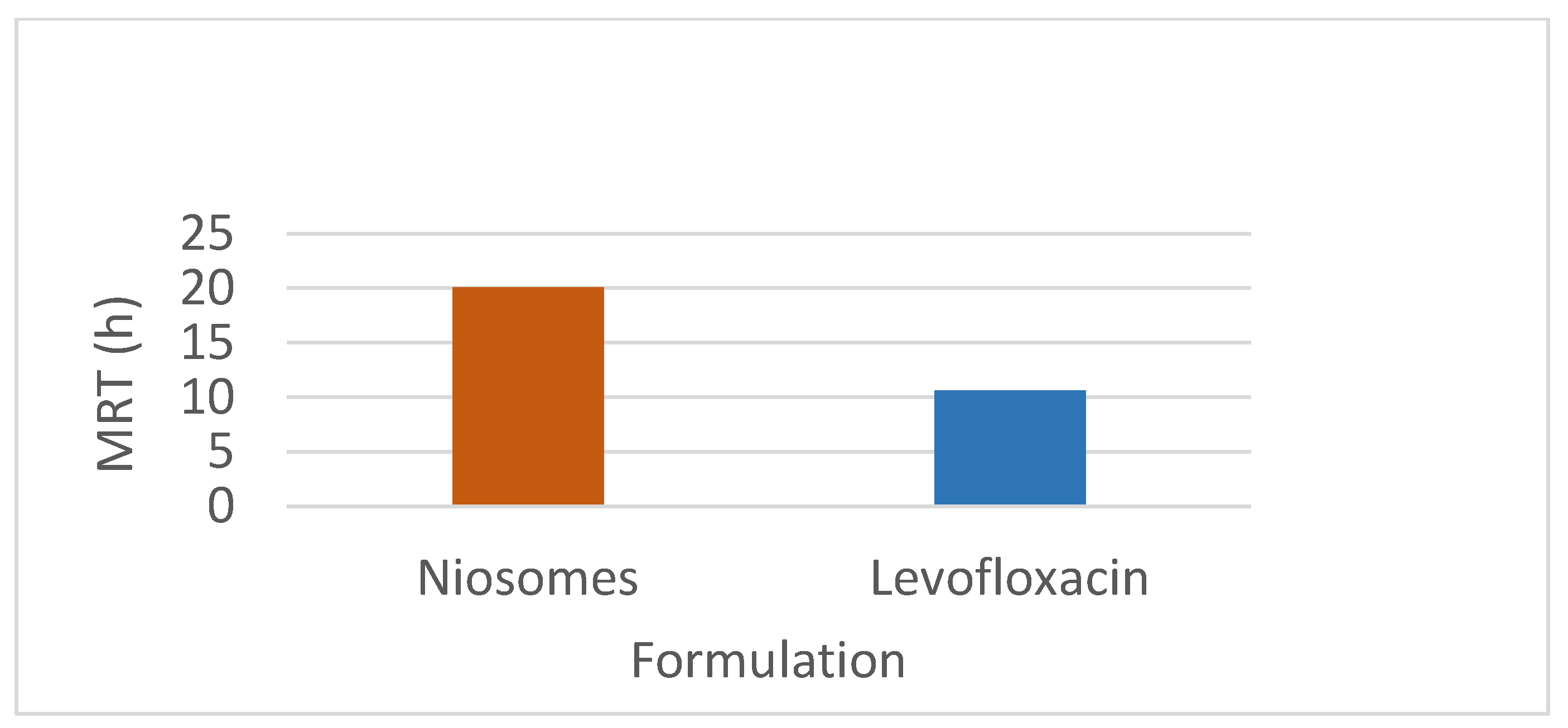

This study investigated the pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin niosomes following a single dose administered intraperitoneally to Sprague Dawley rats, using conventional unentrapped drug as reference. Guided by results of previous studies, an experimental design software (DoE Fusion One) was used to design screening experiments that provided factor combinations and processing variable settings that resulted in an optimized formulation. Optimized niosomes of levofloxacin were prepared, characterized and evaluated in vitro for drug release rate. The well-characterized formulation was used for in vivo study in Sprague Dawley rats in a non-cross over parallel study. One of two groups of rats (n = 6 each) was injected intraperitoneally with conventional levofloxacin and the other with levofloxacin niosomes at 7.5mg/kg/dose. Blood samples were collected at ½, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 48 and 72 hours via tail snip. Drug concentrations were determined using a validated high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) method. The plasma concentration versus time data from rats were fed into the Gastroplus software (Simulations Plus, CA) and used to model the pharmacokinetic profiles of the i.p. levofloxacin and its niosomes. The optimized drug-loaded niosomes used for in vivo rat study had a mean size of 368.8 (± 11.0 SE), encapsulation efficiency (EE) of 34.21 %, Zeta potential of -42.10 (± 2.07 SE) and mean polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.316 (± 0.014 SE). Following i.p. injection, levofloxacin release was controlled with less than 80 % released in 6 h and about 90% released in 12 h. Modeling of levofloxacin bio-disposition following i.p. injection in rats with Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Schwarz criterion (SC) indicated that the niosomes formulations are best fitted to one-compartment model while the conventional drug formulation followed two-compartment model. The niosomal formulation appeared to alter the biodistribution of levofloxacin, and concentrated the drug in the vascular compartment with slow, sustained distribution outside of the vascular compartment. Overall, the niosomes formulation showed significant increase in levofloxacin mean residence time (MRT), prolonged its elimination half-life (t1/2) and decrease its volume of distribution (Vd). Encapsulation of levofloxacin in niosomes altered its pharmacokinetic profile. It appears that, by vesicular encapsulation, niosomes altered levofloxacin biodistribution possibly by preventing its binding to plasma protein while correspondingly increasing its residence time in systemic circulation. Thus, by protecting intraperitoneally injected levofloxacin en route into the plasma, niosomes significantly enhance its delivery to, and concentration in, the intravascular compartment with enanced potential for treating intravascular conditions like bacteremia.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Declaration

2.2. Experimental Design for Niosomes Formulation

2.3. Niosomes Preparation and Characterization

2.3.1. Characterization of Niosomes

2.3.2. Assay of Niosomes Drug Content

2.4. Design of Bioavailability Study

2.5. Samples Preparation for HPLC Analysis

2.6. Treatment and PK Analysis of Plasma Data

3. Results

3.1. Niosomes Physicochemical Properties

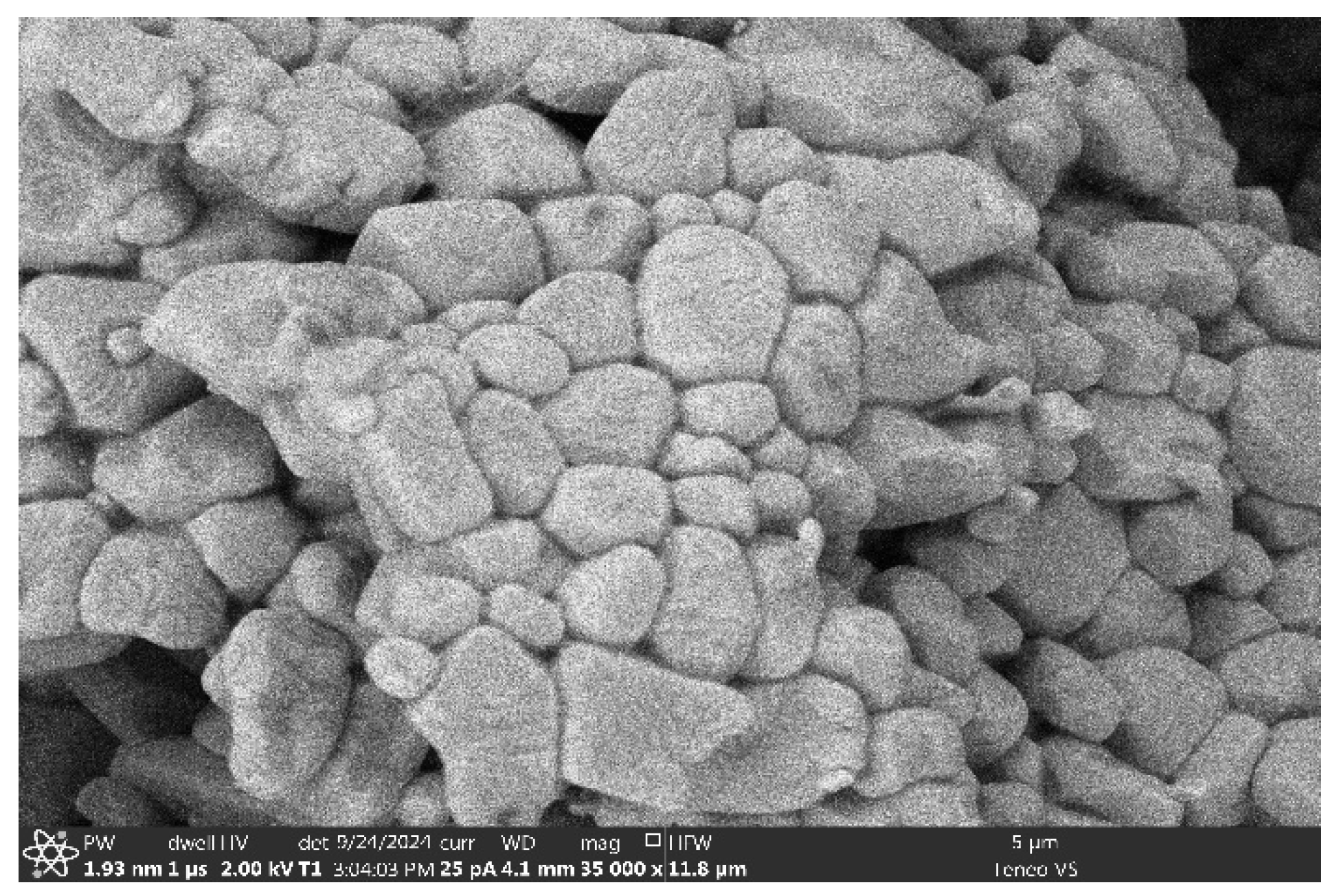

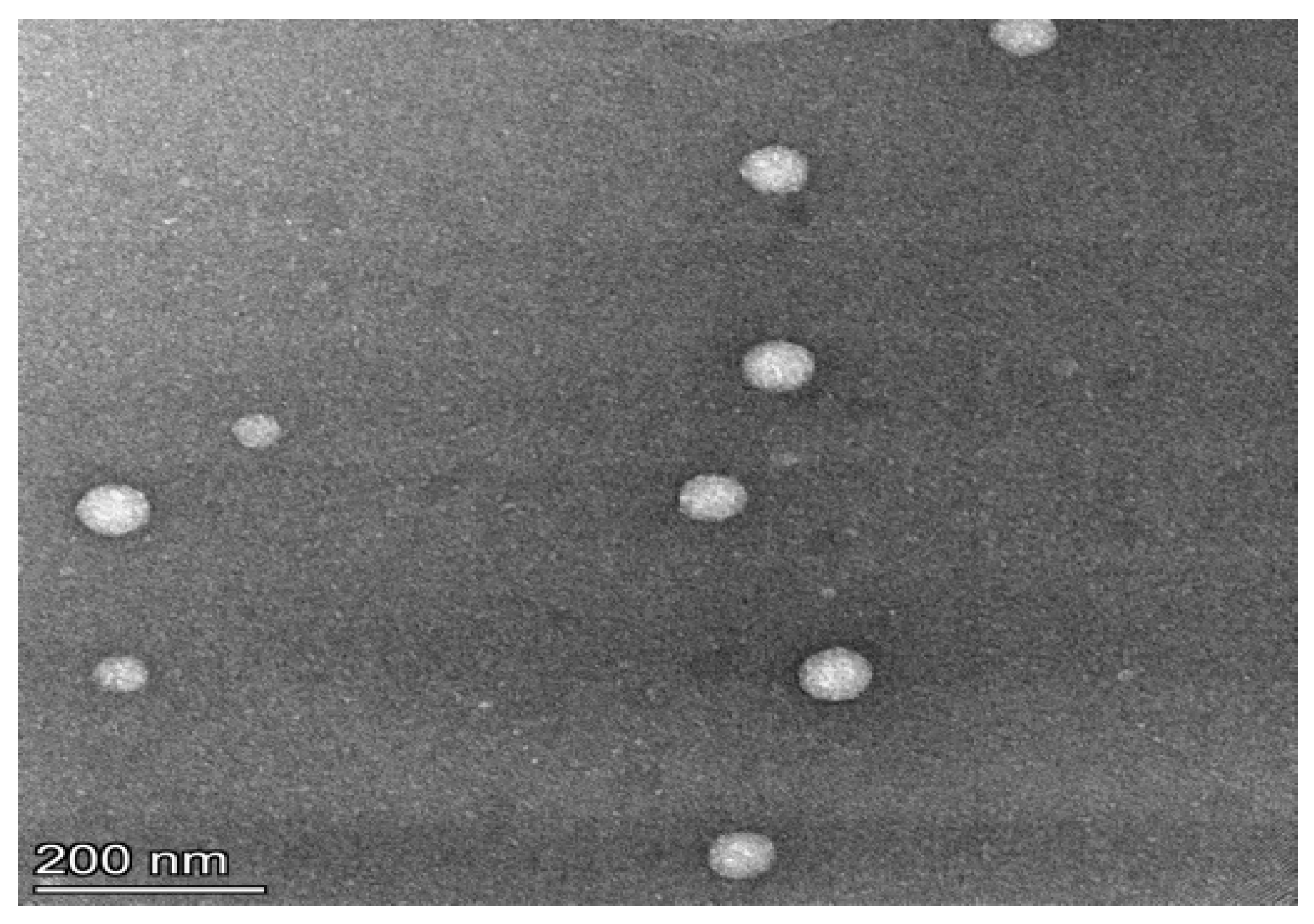

3.1.1. Morphology, PDI and Zeta Potential

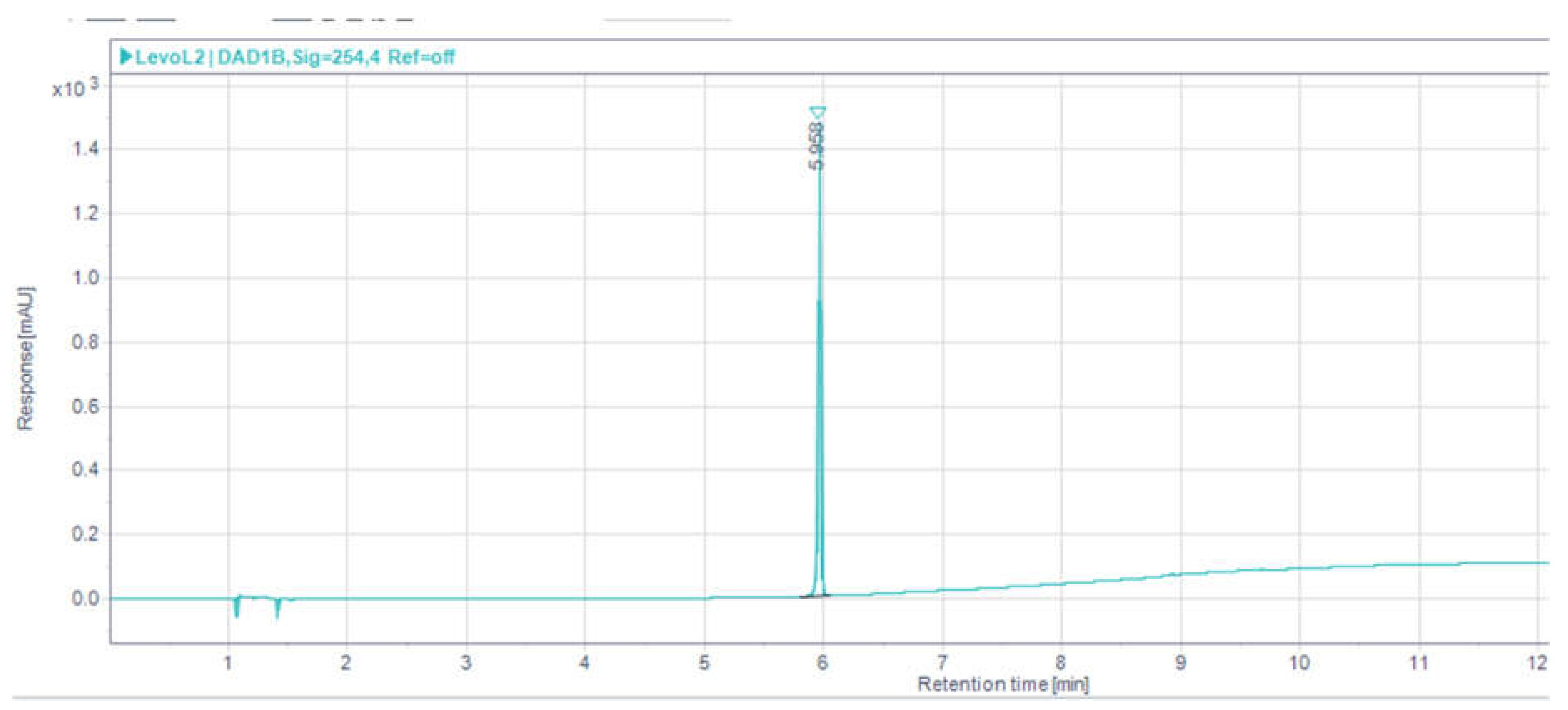

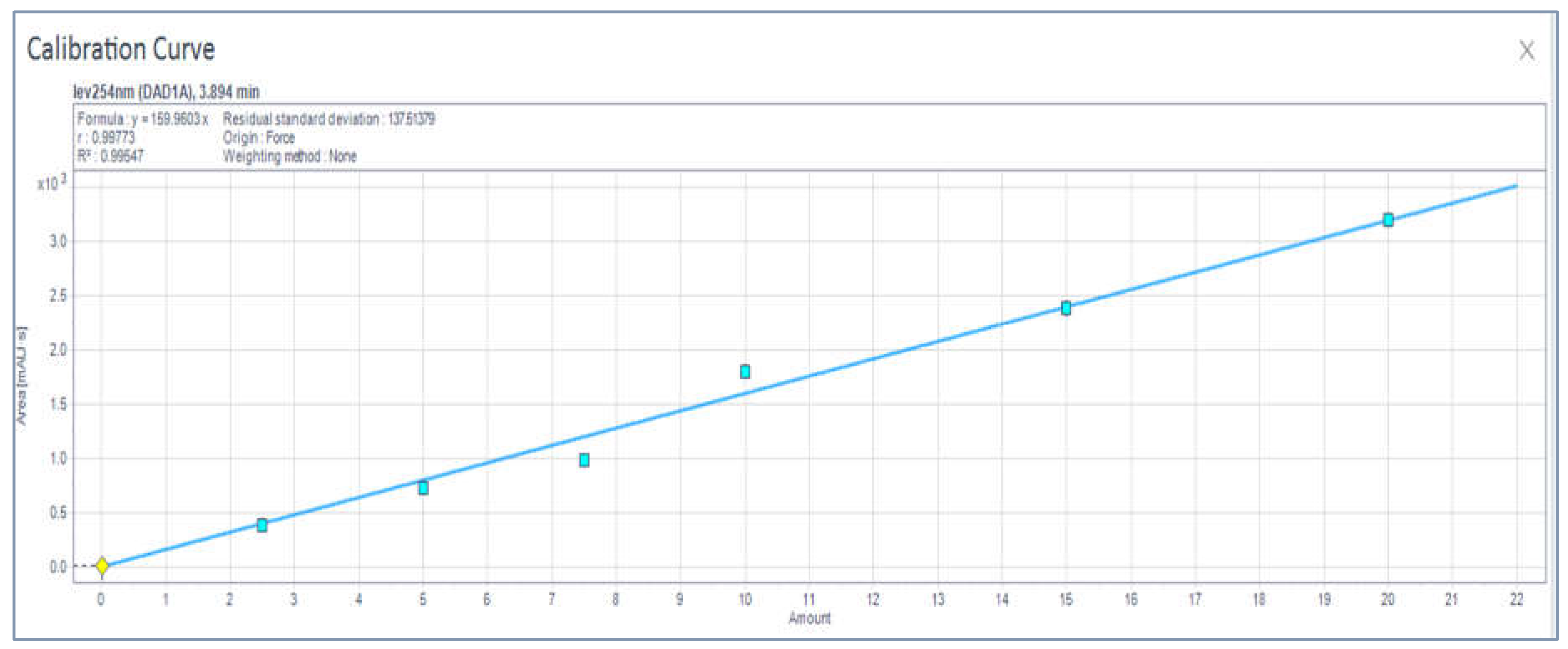

3.1. HPLC Analytical Method Parameters

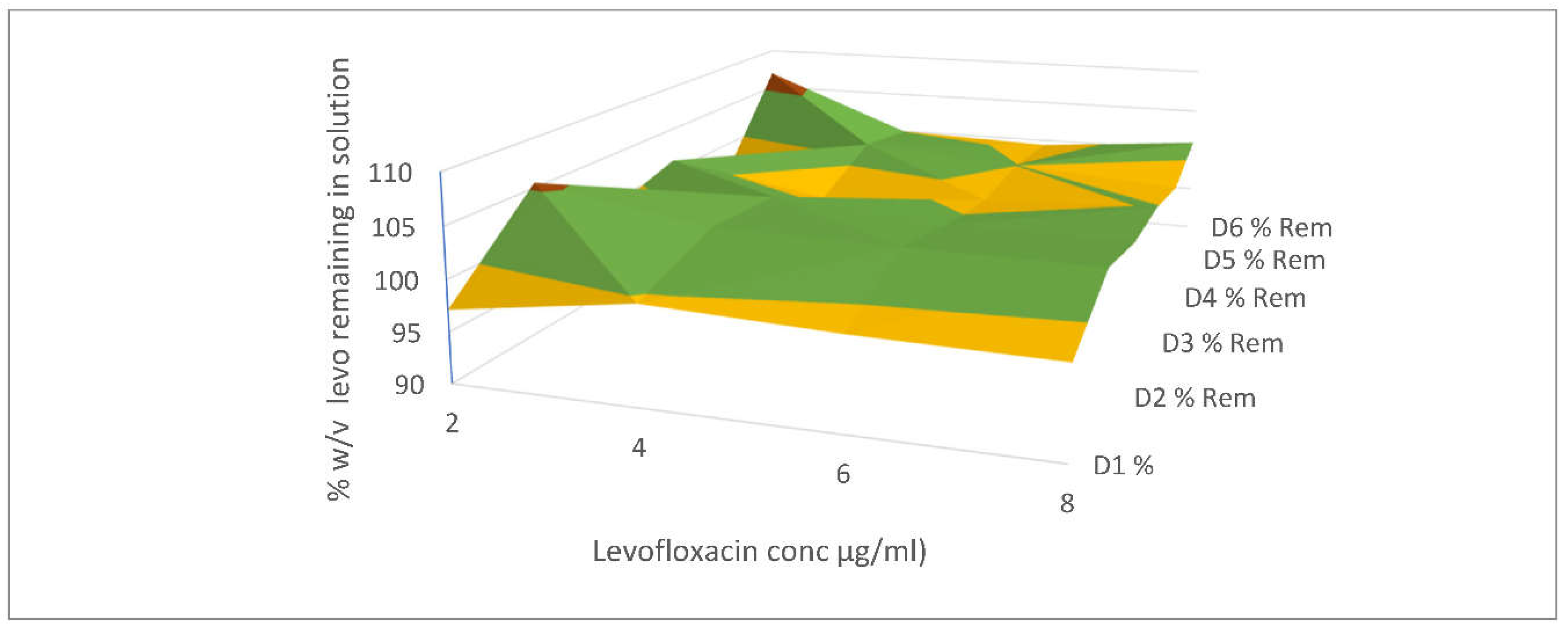

3.3. Drug Dissolution from Niosomes

3.2. Non-Compartmental Analysis (NCA) in GastroPlus™

4. Discussion

Niosome Formulation and Characterization

4.2. PK Modeling and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPLC | High Pressure Liquid Chromatography |

| EE | Encapsulation Efficiency |

| AIC | Akaike information criteria (AIC) |

| BIC | Bayesian information criterion |

| SC | Schwartz criteria (SC) |

| MRT | Mean Residence time |

| Vd | Volume of distribution |

| t1/2 | Elimination half-life |

| AUC | Area under the Plasma Concentration Versus Time Plot |

| AUMC | Area Under the First Moment Curve |

| SMEDDS | Self-microemulsifying Drug Delivery System |

| SCF | Super Critical Fluid |

| BCS | Biopharmaceutics Classification System |

| CHOL | Cholesterol |

| DCP | Dicetyl phosphate |

| SAA | Surface Active Agent |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscope |

| PDI | Polydispersity Index |

| Cl | Clearance |

| Vss | Volume of distribution at steady state |

| Cmax | Maximum plasma concentration |

| Vc | Volume of (distribution) central compartment |

References

- Nix DE, Goodwin SD, Peloquin CA, Rotella DL, Schentag JJ. Antibiotic tissue penetration and its relevance: models of tissue penetration and their meaning. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:1947–52. [CrossRef]

- Dalhoff A. A review of quinolone pharmacokinetics. In: Fernandes PB,editor. Tele-symposium on quinolones: Barcelona, Spain: JR Prous Science Publishers; 1989. 277-312.

- Easmon CS, Crane JP. Uptake of ciprofloxacin by human neutrophils. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;16(1):67–73. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi N, Blom-Potar MC. Intracellular bactericidal activity of ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv multiplying in the J-774 macrophage cell line. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1990;273(2):195–9. [CrossRef]

- Nikaido H, Vaara M. Molecular basis of bacterial outer membrane permeability. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49(1):1–32. [CrossRef]

- Hancock REW, Raffle VJ, Nicas TI. Involvement of the outer membrane in gentamicin and streptomycin uptake and killing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19(5):777–85. [CrossRef]

- Bedard J, Wong S, Bryan LE. Accumulation of enoxacin by Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31(9):1348–54. [CrossRef]

- Koeppe MO, Cristofoletti R, Fernandes EF, Storpirtis S, Junginger HE, Kopp S, Midha KK, Shah VP, Stavchansky S, Dressman JB, Barends DM. Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Levofloxacin. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011 May 1;100(5):1628-36. [CrossRef]

- Jankie S, Johnson J, Pinto Pereira LM, Adebayo AS, Pillai GK. Acute and Subacute Toxicity of Sorbitan Monostearate (Span 60) Non-ionic Surfactant Vesicles (Niosomes) in Sprague Dawley Rats. British Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2016; 14. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Akbarzadeh, I., Yaraki, M. T., Bourbour, M., Noorbazargan, H., Lajevardi, A., Shilsar, S. M. S., ... & Mousavian, S. M. (2020). Optimized doxycycline-loaded niosomal formulation for treatment of infection-associated prostate cancer: An in-vitro investigation. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 57, 101715. [CrossRef]

- Paganoni R, Herzog C, Braunsteiner A, Hohl P. Fleroxacin: in-vitro activity worldwide against 20,807 clinical isolates and comparison to ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22 Suppl D:3–17. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S., Joyce, P., Thomas, N., & Prestidge, C. A. (2021). Bioinspired drug delivery strategies for repurposing conventional antibiotics against intracellular infections. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 177, 113948. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich E. The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. International journal of nanomedicine. 2012 Nov 2:5577-91. [CrossRef]

- Fish DN, Chow AT. The clinical pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997 Feb;32(2):101-19. [CrossRef]

- Bilardi C, Dulbecco P, Zentilin P, Reglioni S, Iiritano E, Parodi A, Accornero L, Savarino E, Mansi C, Mamone M, Vigneri S. A 10-day levofloxacin-based therapy in patients with resistant Helicobacter pylori infection: a controlled trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2004 Nov 1;2(11):997-1002.

- Hu Y, Zhang M, Lu B, Dai J. Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance, a continuing and intractable problem. Helicobacter. 2016 Oct;21(5):349-63.

- Maeda, Y., Takahashi, Y., Naika, Y., Maeda, T., Otsuka, Y., Saeki, Y., Otani, S., Kohama, K., Hieda, Y., Goromaru, T., Eto, S., & Murakami, T. (2023). Ester Prodrugs of Levofloxacin to Prevent Chelate Formation in Presence of Aluminium Ion. Pharmaceutical Sciences, 29(1), 65-74. [CrossRef]

- Adeyeye MC, Adebayo A. Hard Shell Capsules in Clinical Trials. In Pharmaceutical Dosage Forms 2017 Oct 30 (pp. 31-74). CRC Press.

- Stasiłowicz A, Tykarska E, Rosiak N, Sałat K, Furgała-Wojas A, Plech T, Lewandowska K, Pikosz K, Pawłowicz K, Cielecka-Piontek J. The Inclusion of tolfenamic acid into cyclodextrins stimulated by microenvironmental pH modification as a way to increase the anti-migraine effect. Journal of Pain Research. 2021 Apr 14:981-92. [CrossRef]

- Mu H, Holm R. Solid lipid nanocarriers in drug delivery: characterization and design. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 2018 Aug 3;15(8):771-85. [CrossRef]

- Bagheri H, Notej B, Shahsavari S, Hashemipour H. Supercritical carbon dioxide utilization in drug delivery: Experimental study and modeling of paracetamol solubility. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022 Oct 1;177:106273. [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi-Kouhsar M, Bagheri H, Alsaikhan F, Aldhalmi AK, Ahmed HH. Solubility of digitoxin in supercritical CO2: Experimental study and modeling. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2024 Apr 1;195:106731. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini S, Mehrtash M, Khamesee MB. Design, fabrication and control of a magnetic capsule-robot for the human esophagus. Microsystem technologies. 2011 Jun;17:1145-52. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi M, Emami J, Hasanzadeh F, Minaiyan M, Mirian M, Lavasanifar A. Pegylated multifunctional pH-responsive targeted polymeric micelles for ovarian cancer therapy: synthesis, characterization and pharmacokinetic study. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials. 2021 Sep 22;70(14):1012-26.

- Blokhina SV, Sharapova AV, Ol'khovich MV, Volkova ТV, Perlovich GL. Solubility, lipophilicity and membrane permeability of some fluoroquinolone antimicrobials. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2016 Oct 10;93:29-37. [CrossRef]

- Behroozi R, Dehghanian E. Drug repurposing study of levofloxacin: Structural properties, lipophilicity along with experimental and computational DNA binding. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 2024 Jun 6:125218. [CrossRef]

- Islan GA, Tornello PC, Abraham GA, Duran N, Castro GR. Smart lipid nanoparticles containing levofloxacin and DNase for lung delivery. Design and characterization. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2016 Jul 1;143:168-76. [CrossRef]

- Cicuendez M, Izquierdo-Barba I, Portolés MT, Vallet-Regí M. Biocompatibility and levofloxacin delivery of mesoporous materials. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 2013 May 1;84(1):115-24. [CrossRef]

- Konreddy AK, Rani GU, Lee K, Choi Y. Recent drug-repurposing-driven advances in the discovery of novel antibiotics. Current medicinal chemistry. 2019 Aug 1;26(28):5363-88. [CrossRef]

- Derbali RM, Aoun V, Moussa G, Frei G, Tehrani SF, Del’Orto JC, Hildgen P, Roullin VG, Chain JL. Tailored nanocarriers for the pulmonary delivery of levofloxacin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a comparative study. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2019 Mar 22;16(5):1906-16. [CrossRef]

- Jankie S, Adebayo AS, Pillai G. In vitro activities of fluoroquinolones entrapped in non-ionic surfactant vesicles against ciprofloxacin-resistant bacteria strains. J Pharm Technol Drug Res.2012; 1:1–1.

- Uchegbu IF, Florence AT. Non-ionic surfactant vesicles (niosomes): physical and pharmaceutical chemistry. Advances in colloid and interface science. 1995 Jun 27;58(1):1-55. [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health (US). Animal Research Committee, & NIH Office of Animal Care. (1999). Using Animals in Intramural Research: Guidelines for Investigators and Guidelines for Animal Users. NIH Animal Research Advisory Committee.

- Hooke, R., & Jeeves, T. A. (1961). “Direct Search'' Solution of Numerical and Statistical Problems. Journal of the ACM (JACM), 8(2), 212-229. [CrossRef]

- Wadham JJB, Townsend P, Morton DB. Intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital as a method for euthanasia for rodents. Australian and New Zealand Council for the care of animals in research and teaching. 1997; 10 (4): 8.

- Siefert, C. M. (2000). Model-assisted pattern search (Doctoral dissertation, College of William and Mary).

- Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE transactions on automatic control, 19(6), 716-723. [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, N. (1978). Further analysis of the data by akaike's information criterion and the finite corrections: Further analysis of the data by akaike's. Communications in Statistics-theory and Methods, 7(1), 13-26.

- Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The annals of statistics, 461-464. [CrossRef]

- Danaei M, Dehghankhold M, Ataei S, Hasanzadeh Davarani F, Javanmard R, Dokhani A, Khorasani S, Mozafari MR. Impact of Particle Size and Polydispersity Index on the Clinical Applications of Lipidic Nanocarrier Systems. Pharmaceutics. 2018 May 18;10(2):57. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q., Deng, C., Fu, Y., Sun, X., Gong, T., & Zhang, Z. (2016). Repeated administration of hyaluronic acid coated liposomes with improved pharmacokinetics and reduced immune response. Molecular pharmaceutics, 13(6), 1800-1808. [CrossRef]

- Hurtado FK, Weber B, Derendorf H, Hochhaus G, Dalla Costa T. Population pharmacokinetic modeling of the unbound levofloxacin concentrations in rat plasma and prostate tissue measured by microdialysis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2014 Feb;58(2):678-86. [CrossRef]

- Ruckmani K, Sankar V, Sivakumar M. Tissue distribution, pharmacokinetics and stability studies of zidovudine delivered by niosomes and proniosomes. Journal of biomedical nanotechnology. 2010 Feb 1;6(1):43-51. [CrossRef]

- Ammar HO, Haider M, Ibrahim M, El Hoffy NM. In vitro and in vivo investigation for optimization of niosomal ability for sustainment and bioavailability enhancement of diltiazem after nasal administration. Drug delivery. 2017 Jan 1;24(1):414-21. [CrossRef]

- Feitosa RC, Ishikawa ES, da Silva MF, da Silva-Junior AA, Oliveira-Nascimento L. Five decades of doxycycline: Does nanotechnology improve its properties? International journal of pharmaceutics. 2022 Apr 25; 618:121655.

- Nestorov IA, Aarons LJ, Arundel PA, Rowland M. Lumping of whole-body physiologically based pharmacokinetic models. Journal of pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics. 1998 Feb;26:21-46. [CrossRef]

- Jeong YS, Kim MS, Chung SJ. Determination of the number of tissue groups of kinetically distinct transit time in whole-body physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models I: theoretical consideration of bottom-up approach of lumping tissues in whole-body PBPK. The AAPS journal. 2022 Aug 24;24(5):90. [CrossRef]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR, editors. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2002 Jul.

- Xie Q, Deng W, Yuan X, Wang H, Ma Z, Wu B, et al. Selenium-functionalized liposomes for systemic delivery of doxorubicin with enhanced pharmacokinetics and anticancer effect. Eur J Pharm Biopharm.2018; 122, 87-95. [CrossRef]

- Bayindir ZS, BEŞİKCİ A, Yüksel N. Paclitaxel-loaded niosomes for intravenous administration: pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution in rats. Turkish journal of medical sciences. 2015;45(6):1403-12.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).