Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Chiral Symmetry Approach for Kaon Condensation

2.1. Kaon-Baryon and Multi-Kaon Interactions

3. Baryon Interactions

3.1. Minimal RMF for Baryon-Baryon Interaction

3.2. Universal Three-Baryon Repulsive Force and Three Nucleon Attractive Force

4. Description of the Ground State for the (Y+K) Phase

4.1. Energy Density Expression for the (Y+K) Phase

4.2. Classical Field Equations for Kaon Condensates and Meson Mean Fields

4.3. Ground-State Conditions

5. Properties of Symmetric Nuclear Matter

5.1. Meson-Nucleon Coupling Constants Determined From Saturation Properties in SNM

| (MeV·fm6) | (fm3) | (MeV) | (MeV) | ||||||||

| SJM2+TNA-L60 | −1662.63 | 17.18 | 5.27 | 8.16 | 3.29 | 39.06 | 16.37 | 0.78 | 3.29 | 2.00 | 1.82 |

| SJM2+TNA-L65 | −1597.67 | 18.25 | 5.71 | 9.07 | 3.35 | 42.16 | 18.18 | 0.74 | 3.54 | 2.34 | 1.93 |

| SJM2+TNA-L70 | −1585.48 | 19.82 | 6.07 | 9.77 | 3.41 | 44.62 | 19.59 | 0.71 | 3.74 | 2.61 | 2.02 |

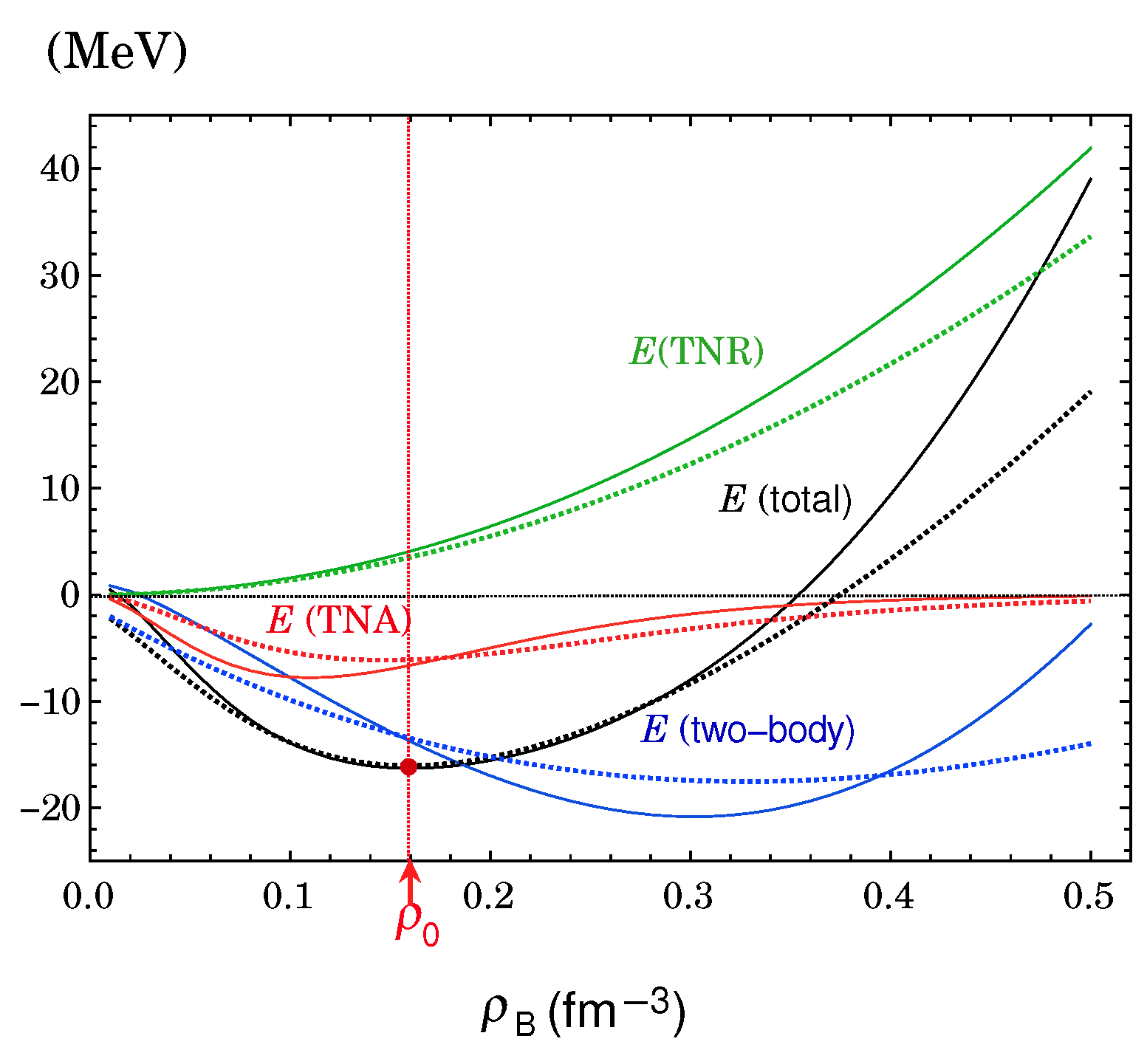

5.2. Necessity of Three-Body Repulsion and Attraction for Empirical Saturation of SNM

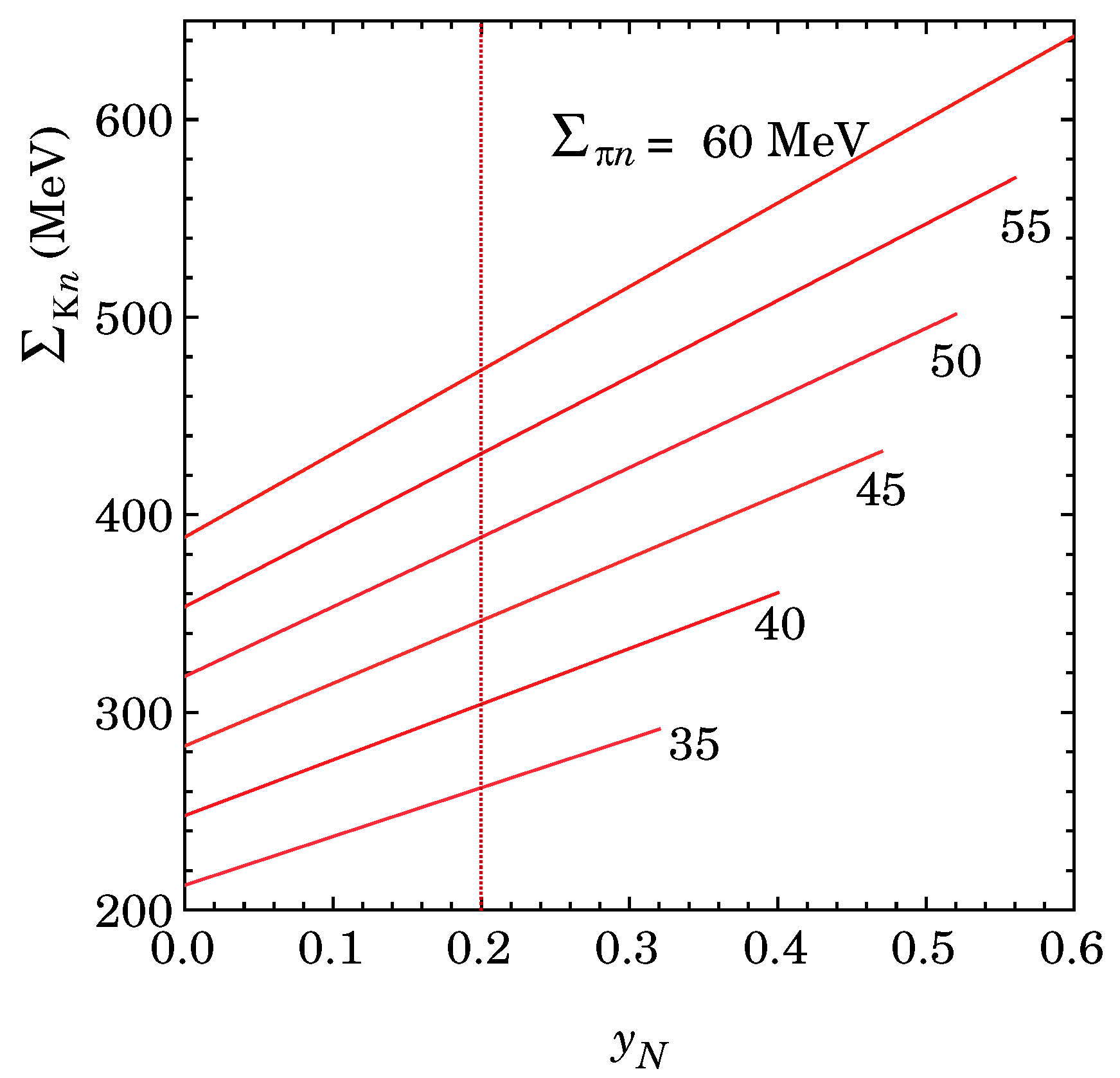

6. Estimation of the Kaon-Baryon Sigma Terms-Quark Condensates in the Baryon -

6.1. Nonlinear Effect on the Quark Condensates

| () | (= ) | (= ) | |||||||

| (MeV) | (MeV) | (MeV) | (MeV) | (MeV) | |||||

| (−0.697, 1.37) | −3.09 | 47.4 | 0 | −3.43 | −2.23 | 300 | 368 | 379 | −111 |

| −3.37 | 51.3 | 0.20 | −2.51 | −2.74 | 400 | 468 | 479 | −131 |

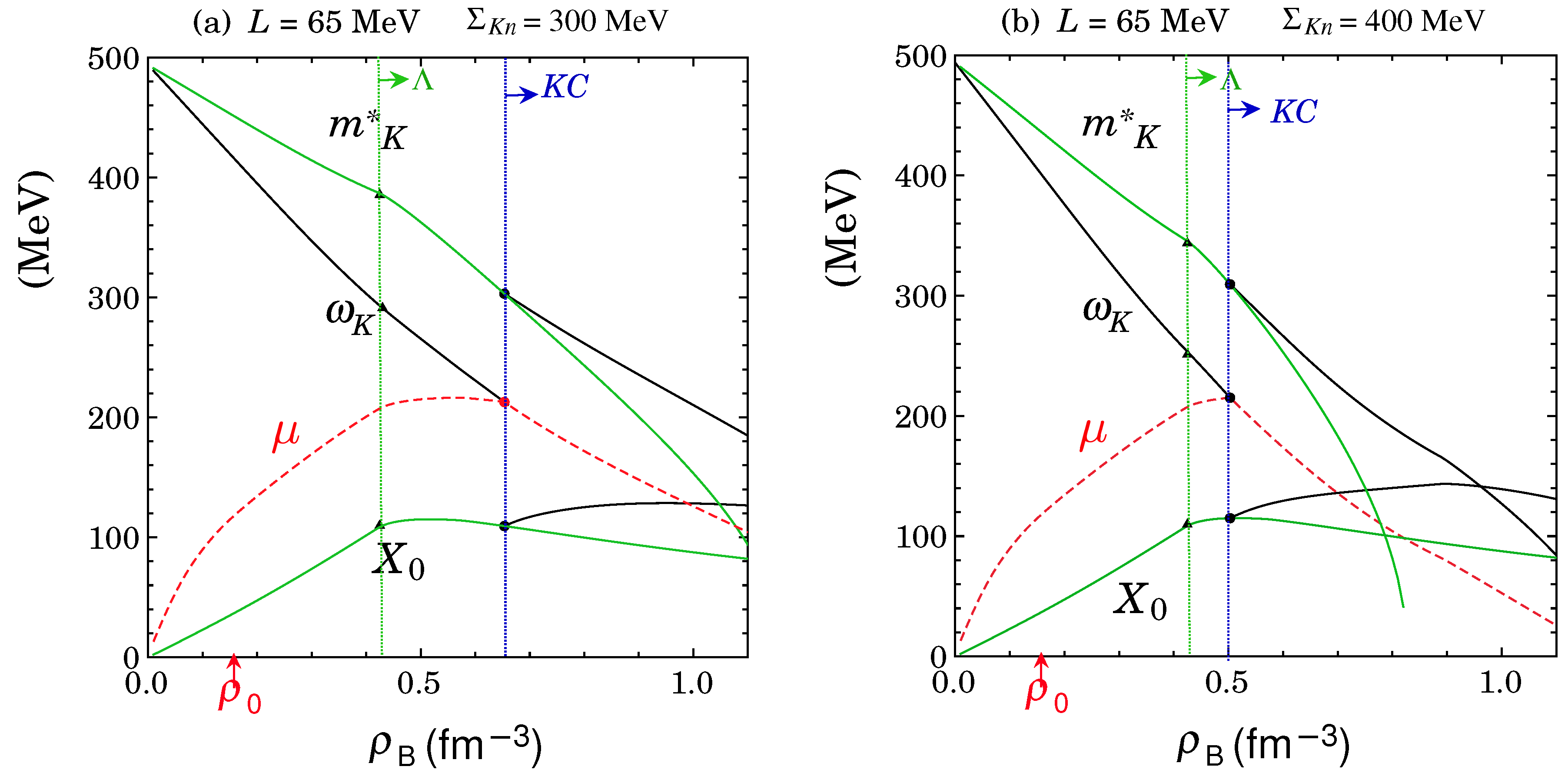

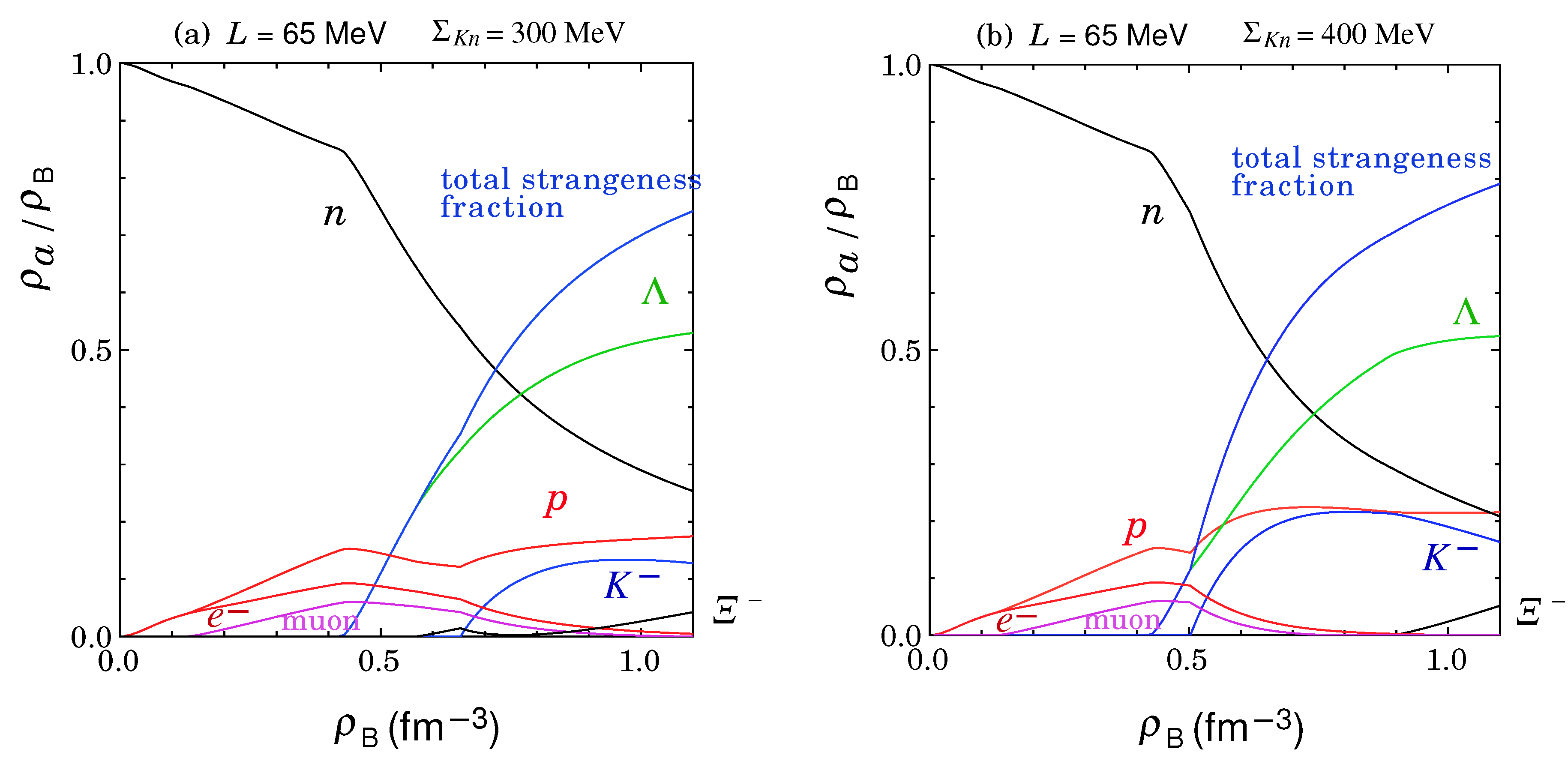

7. Onset of KC and Composition of Matter in the ( + ) Phase

7.1. Onset Density of Kaon Condensation in Hyperon-Mixed Matter

| L | |||||

| (MeV) | (MeV) | (fm−3) | (fm−3) | (fm−3) | (fm−3) |

| 60 | 300 | 0.466 | − | 0.598 | 1.04 |

| 400 | 0.466 | − | 0.486 | 0.994 | |

| 65 | 300 | 0.425 | 0.568 | 0.653 | − |

| 400 | 0.425 | − | 0.503 | 0.900 | |

| 70 | 300 | 0.397 | 0.516 | 0.733 | − |

| 400 | 0.397 | (0.516) | 0.523 | 0.790 |

7.2. Interplay Between Kaons and Baryons Before and After the Onset of KC

8. EOS and Structure of Neutron Stars with the ( + ) phase

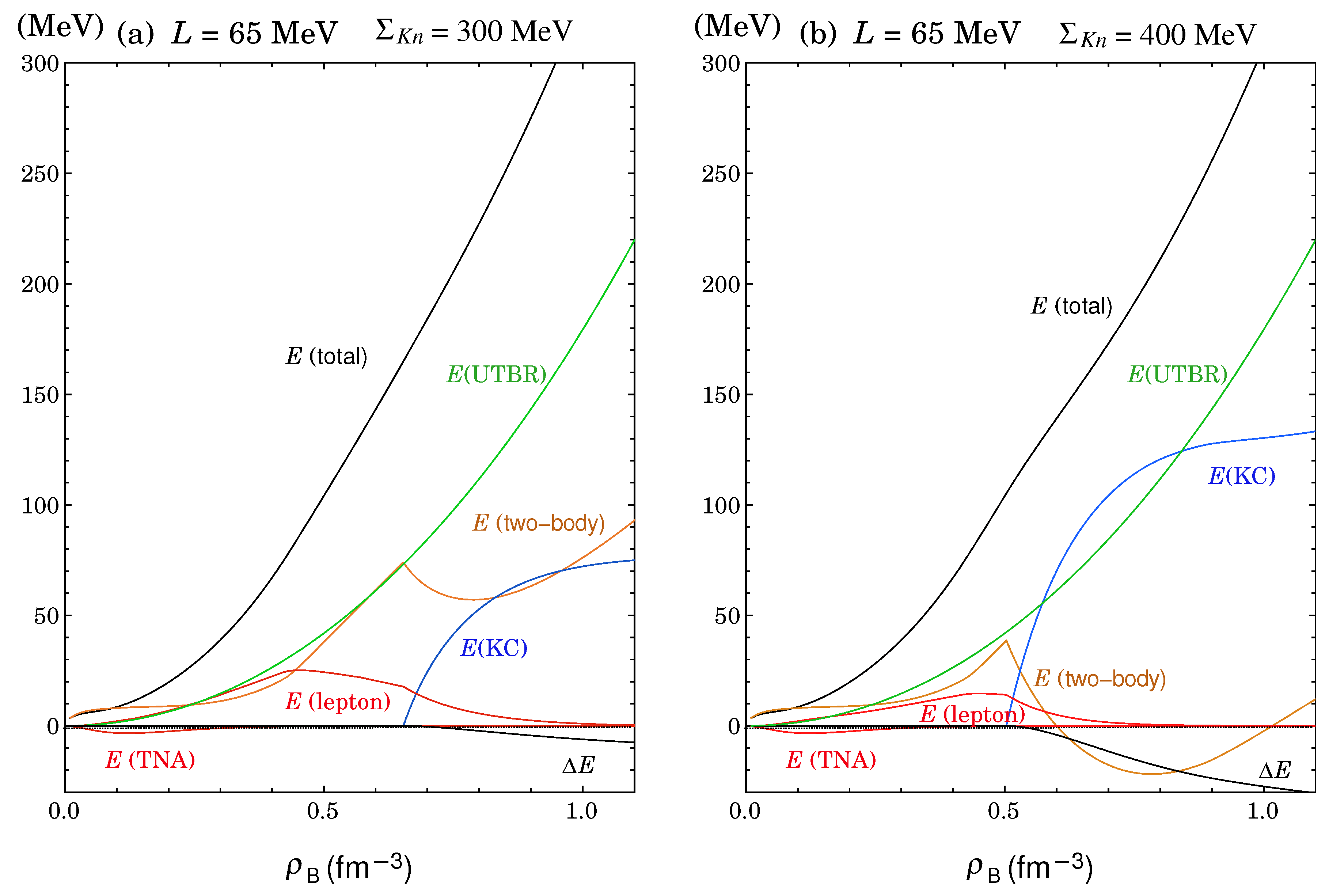

8.1. Energy Per Unit of Baryon

8.2. Gravitational Mass to Radius Relations

9. Quark Condensates in the (Y+K) Phase and Relevance to Chiral Restoration

10. Summary and Outlook

Acknowledgments

References

- R. F. Sawyer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 29,382 (1972). D. J. Scalapino, Phys. Rev. Lett. 29, 392 (1972).

- A. B. Migdal, Rev. Mod. Phys. 50, 107 (1978).A. B. Migdal, E. E. Saperstein, M. A. Troitsky, and D. N. Voskresensky, Phys. Rep. 192, 179 (1990).

- G. Baym and D. K. Campbell, Mesons and Nuclei, ed. M. Rho and D. H. Wilkinson (North Holland, Amsterdam, 1979),Vol. III, p.1031.

- T. Kunihiro, T. Muto, T. Takatsuka, R. Tamagaki, and T. Tatsumi, Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 112,1 (1993).

- D. B. Kaplan and A. E. Nelson, Phys. Lett. B 175, 57 (1986).

- T. Tatsumi, Prog. Theor. Phys. 80, 22 (1988).

- T. Muto and T. Tatsumi, Phys. Lett. B 283, 165 (1992).

- T. Muto, Prog. Theor. Phys. 89 (1993) 415.

- T. Muto, R. Tamagaki, and T. Tatsumi, Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 112, 159 (1993).T. Muto, T. Takatsuka, R. Tamagaki, and T. Tatsumi, Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 112, 221 (1993).

- V. Thorsson, M. Prakash, and J. M. Lattimer, Nucl. Phys. A 572, 693 (1994); Nucl. Phys. A 574, 851 (1994) (E).

- E. E. Kolomeitsev, D. N. Voskresensky, B. Kämpfer, Nucl. Phys. A 588 (1995) 889.

- C. -H. Lee, G. E. Brown, D. -P. Min, and M. Rho, Nucl. Phys. A 585, 401 (1995).

- C. -H. Lee, Phys. Rep. 275,197 (1996).

- M. Prakash, I. Bombaci, M. Prakash, P. J. Ellis, J. M. Lattimer, and Knorren, Phys. Rep. 280, 1 (1997).

- K. Tsushima, K. Saito, A. W. Thomas, and S. V. Wright, Phys. Lett. B 429, 239 (1998); ibid. 436, 453 (1998) (E).

- H. Fujii, T. Maruyama, T. Muto, and T. Tatsumi, Nucl. Phys. A 597, 645 (1996).

- P. J. Ellis, R. Knorren, and M. Prakash, Phys. Lett. B349, 11 (1995).

- R. Knorren, M. Prakash, and P. J. Ellis, Phys. Rev. C52, 3470 (1995).

- J. Schaffner and I. N. Mishustin, Phys. Rev. C53, 1416 (1996).

- S. Pal, D. Bandyopadhyay, and W. Greiner, Nucl. Phys. A 674, 553 (2000).

- T. Muto, Phys. Rev. C 77, 015810 (2008), and references cited therein.

- A. Mishra, A. Kumar, S. Sanyal, V. Dexheimer, and S. Schramm, Eur. Phys. J. A 45, 169 (2010).

- P. Char and S. Banik, Phys. Rev. C 90, 015801 (2014).

- T. Malik, S. Banik, and D. Bandyopadhyay, Astrophys. J. 910, No. 2, 96 (2021).

- Fu Ma, C. Wu, and W. Guo, Phys. Rev. C 107, 045804 (2023).

- T. Muto, T. Maruyama, and T. Tatsumi, Phys. Lett. B 820, 136587 (2021).

- T. Muto, T. Maruyama, and T. Tatsumi, Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2022 093D03 (2022).

- T. Muto, arXiv: 2411.09967v1 [nucl-th].

- R. Tamagaki, Prog. Theor. Phys. 119, 965 (2008).

- T. Takatsuka, S. Nishizaki, and R. Tamagaki, AIP Conf. Proc. 1011, 209 (2008).

- P. A. Zyla et al. (Particle Data Group), Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys. 2020, 083C01 (2020).

- J. Schaffner, C. B. Dover, A. Gal, C. Greiner, D. J. Millener, and H. Stöcker, Ann. Phys. 235, 35 (1994).

- S. Nishizaki, T. Takatsuka and J. Hiura, Prog. Theor. Phys. 92, 93 (1994).

- I. E. Lagaris and V. R. Pandharipande, Nucl. Phys. A 359 (1981),349.

- M. Oertel, M. Hempel, T. Kähn, and S. Typel, Rev. Mod. Phys. 89, 015007 (2017).

- H. Ohki et al.(JLQCD Collaboration), Phys. Rev. D 78, 054502 (2008).

- S. Durr, Z. Fodor, C. Hoelbling et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 172001 (2016).

- C. Alexandrou, S. Bacchio, M. Constantinou et al., Phys. Rev. D 102, 054517 (2020).

- J. Gasser, H. Leutwyler, and M. E. Sainio, Phys. Lett. B 253, 260 (1991).

- For a review, J. M. Alarcón,Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 230, 1609 (2021).

- R. L. Jaffe and C. L. Korpa, Comm. Nucl. Part. Phys. 17, 163 (1987).

- T. Hatsuda and T. Kunihiro, Z. Phys. C 51, 49 (1991).

- A. Ramos and E. Oset, Nucl. Phys. A 671, 481 (2000).

- T. Waas, M. Rho, and W. Weise, Nucl. Phys. A 617, 449 (1997).

- T. Waas and W. Weise, Nucl. Phys. A 625, 287 (1997).

- Y. Ichikawa et al., Prog. Theor. Exp. Phys.2020,123D01 (2020).

- P. E. Shanahan, A. W. Thomas, and R. D. Young, Phys. Rev. D 87, 074503 (2013).

- M. F. M. Lutz, R. Bavontaweepanya, C. Kobadaj, and K. Schwarz, Phys. Rev. D 90, 054505 (2014).

- T. Muto, T. Tatsumi, and N. Iwamoto, Phys. Rev. D 61, 063001 (2000); Phys. Rev. D 61, 083002 (2000).

- G. Baym, C. Pethick, and P. Sutherland, Astrophys. J. 170, 299 (1971).

- P. B. Demorest, T. Pennucci, S. M. Ransom, M. S. E. Roberts, and J. W. T. Hessels, Nature 467, 1081 (2010);E. Fonseca, T. T. Pennucci et al., Astrophys. J 832, 167 (2016).

- J. Antoniadis et al., Science 340, 6131 (2013).

- H. T. Cromartie et al., Nat. Astron. 4, 72 (2020);E. Fonseca, H. T. Cromartie, T. T. Pennucci, et al.,Astrophys. J. L. 915, L12 (2021), arXiv:2104.00880 [astro-ph.HE].

- M. C. Miller et al., Astrophys. J. L. 918 L28 (2021), arXiv : 2105.06979 v1 [astro-ph. HE].

- T. E. Riley et al., Astrophys. J. L. 918 L27 (2021), arXiv : 2105.06980 [astro-ph. HE].

- T. E. Riley et al., Astrophys. J. L. 887, L21 (2019).

- M. C. Miller et al., Astrophys. J. L. 887, L24 (2019).

- S. Nishizaki, Y. Yamamoto, and T. Takatsuka, Prog. Theor. Phys. 108, 703 (2002).

- T. D. Cohen, R. J. Furnstahl, and D. K. Griegel, Phys. Rev. C 45, 1881 (1992).

- P. Danielewicz, R. Lacey, and W. G. Lynch, Science 298, 1592 (2002).

- As a review, M. Mannarelli, Particles 2019, 2, 411 (2019).

- H. Abuki, R. Anglani, R. Gatto, M. Pellicoro, and M. Ruggieri, Phys. Rev. D 79, 034032 (2009).

- T. G. Khunjua, K. G. Klimenko, and R. N. Zhokhov, Symmetry 2019, 11, 778 (2019) ; Eur. Phys. J. C (2020) 80:995.

- P. Adhikari and J. .O. Andersen, Eur. Phys. J. C (2020)80:1028; JHEP 2020, 170 (2020).

- A. Schmitt, S. Stetina, and M. Tachibana, Phys. Rev. D 83, 045008 (2011).

- K. Masuda, T. Hatsuda, and T. Takatsuka, Astrophys. J. 764, 12 (2013); PTEP 2016. No. 2, 021D01 (2016).

- G. Baym, S. Furusawa, T. Hatsuda, T. Kojo, and H. Togashi, Astrophys. J. 885, 42 (2019).

- T. Kojo, Phys. Rev. D 104, 074005 (2021).

- Y. Fujimoto, K. Fukushima, L. D. McLerran, and M. Praszalowicz, Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 252702 (2022).

- T. Tatsumi and E. Nakano, arXiv: hep-ph/0408294v1;E. Nakano and T. Tatsumi, Phys. Rev. D 71, 114006 (2005).

- D. T. Son and M. Stephanov, Phys. Rev. D 61, 07402 (2000).

- P. Bedaque and T. Schafer, Nucl. Phys. A 697, 802 (2002).

- D. B. Kaplan and S. Reddy, Phys. Rev. D 65, 054042 (2002).

| L | |||||||

| (MeV) | (MeV) | (km) | (km) | (km) | |||

| 60 | 300 400 |

1.448 | 12.33 | 1.742 1.452 |

12.11 12.33 |

2.035 1.993 |

10.02 9.48 |

| 65 | 300 400 |

1.508 | 12.78 | 1.961 1.737 |

12.29 12.68 |

2.124 2.076 |

10.76 10.29 |

| 70 | 300 400 |

1.582 | 13.15 | 2.139 1.915 |

12.24 12.97 |

2.200 2.155 |

11.31 11.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).