Submitted:

27 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

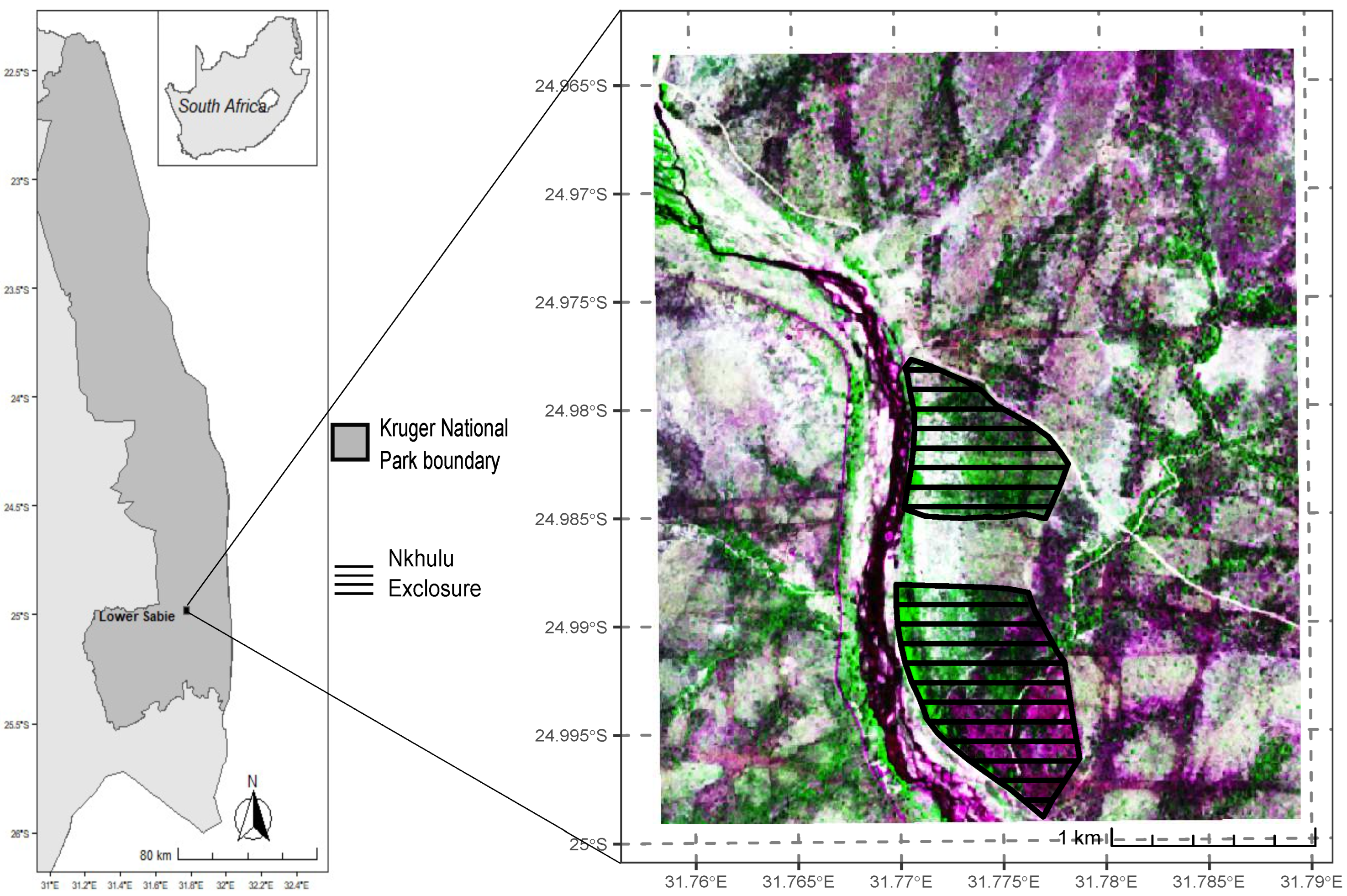

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Land Cover Classification Nomenclature

2.3. Reference Data

2.4. Remote Sensing Data and Preprocessing

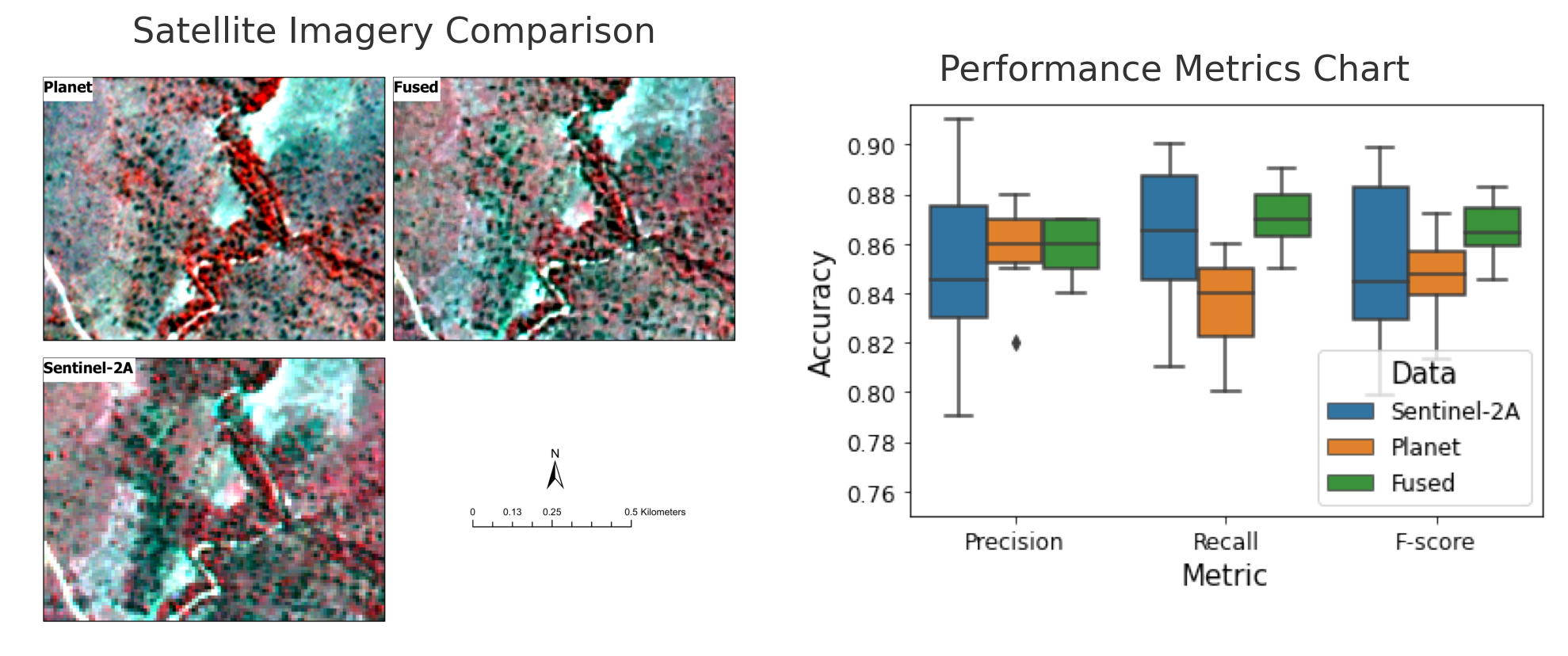

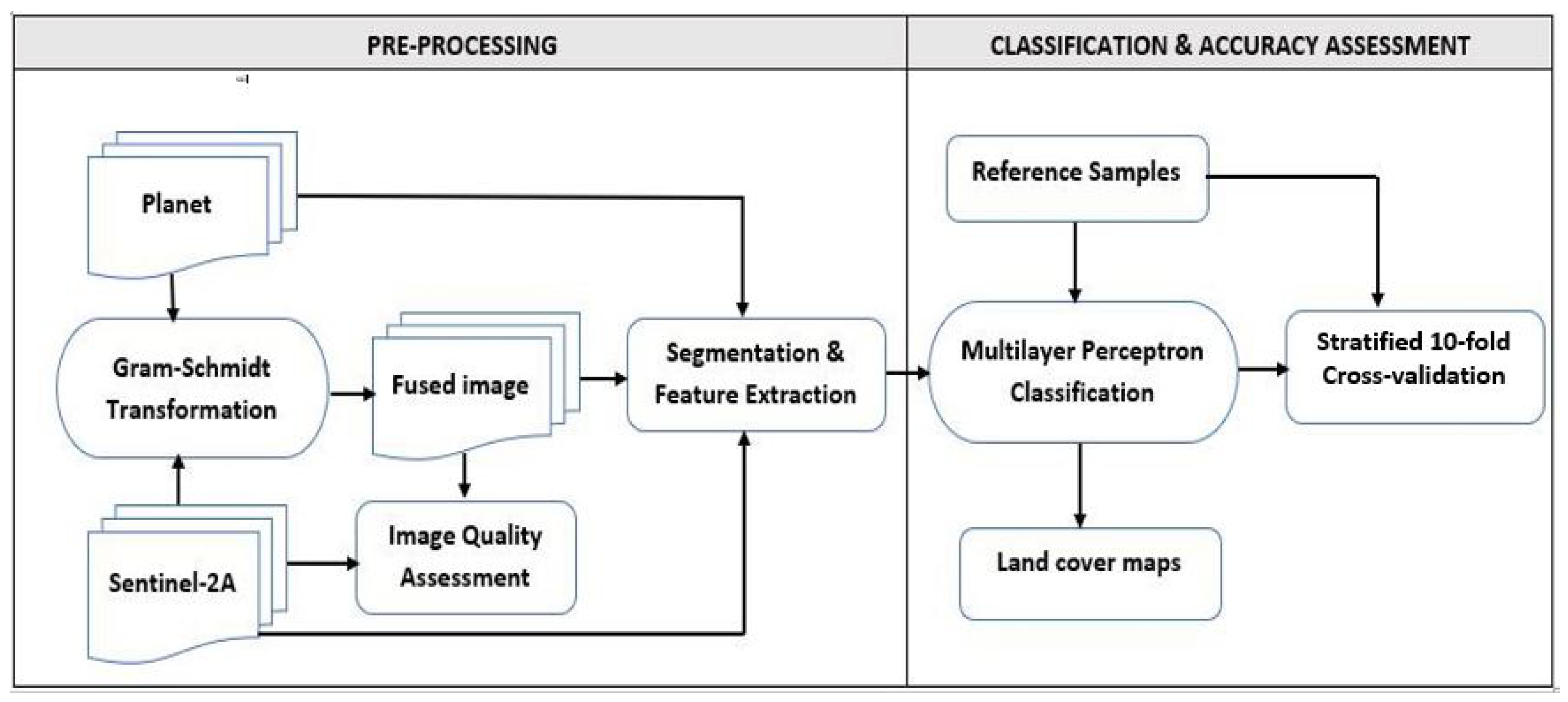

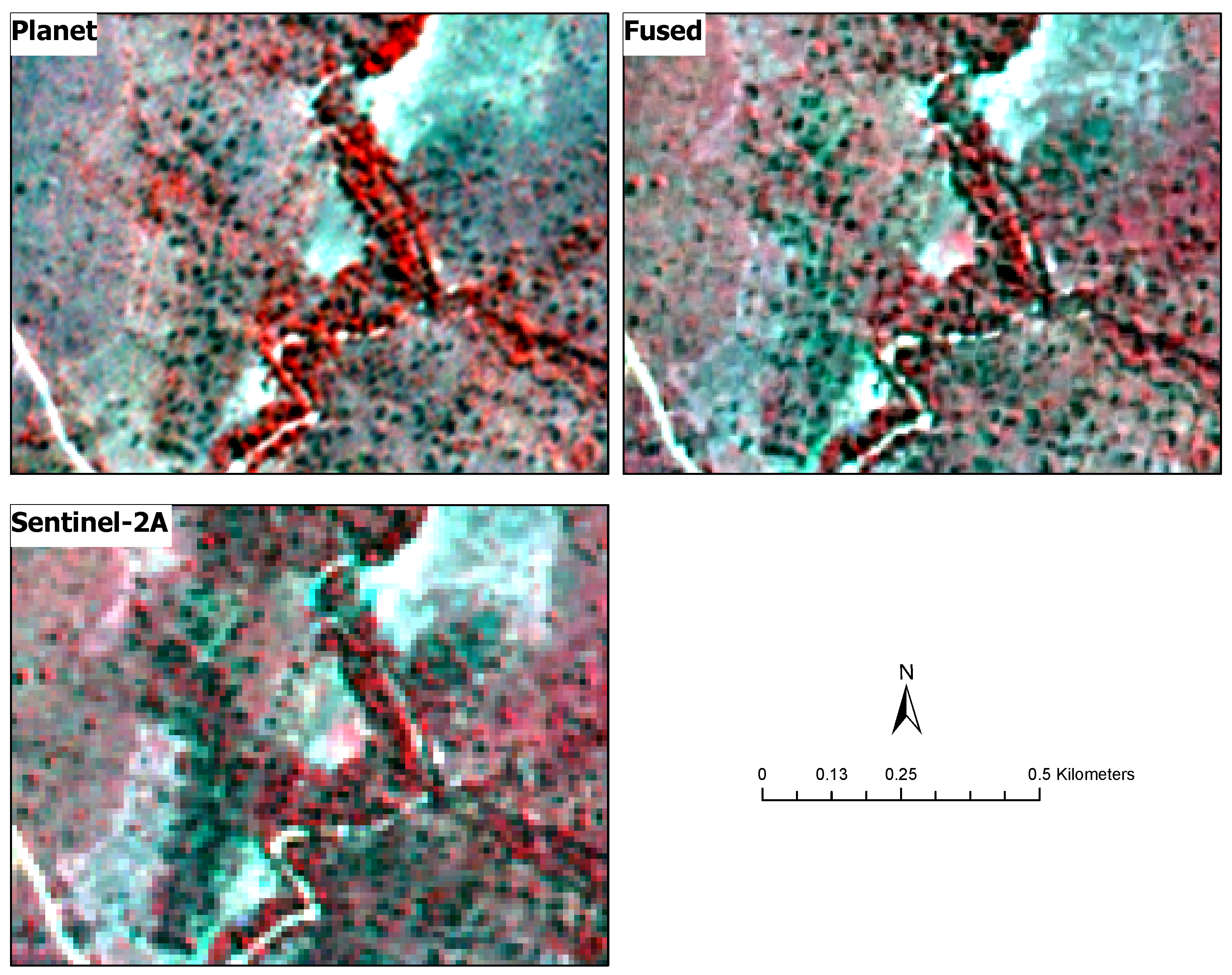

2.5. Multi-sensor Image Fusion

2.6. Image Quality Assessment

2.7. Image Segmentation

2.8. Feature Extraction

2.9. Image Classification and Accuracy Assessment

2.10. Feature Importance Estimation

3. Results

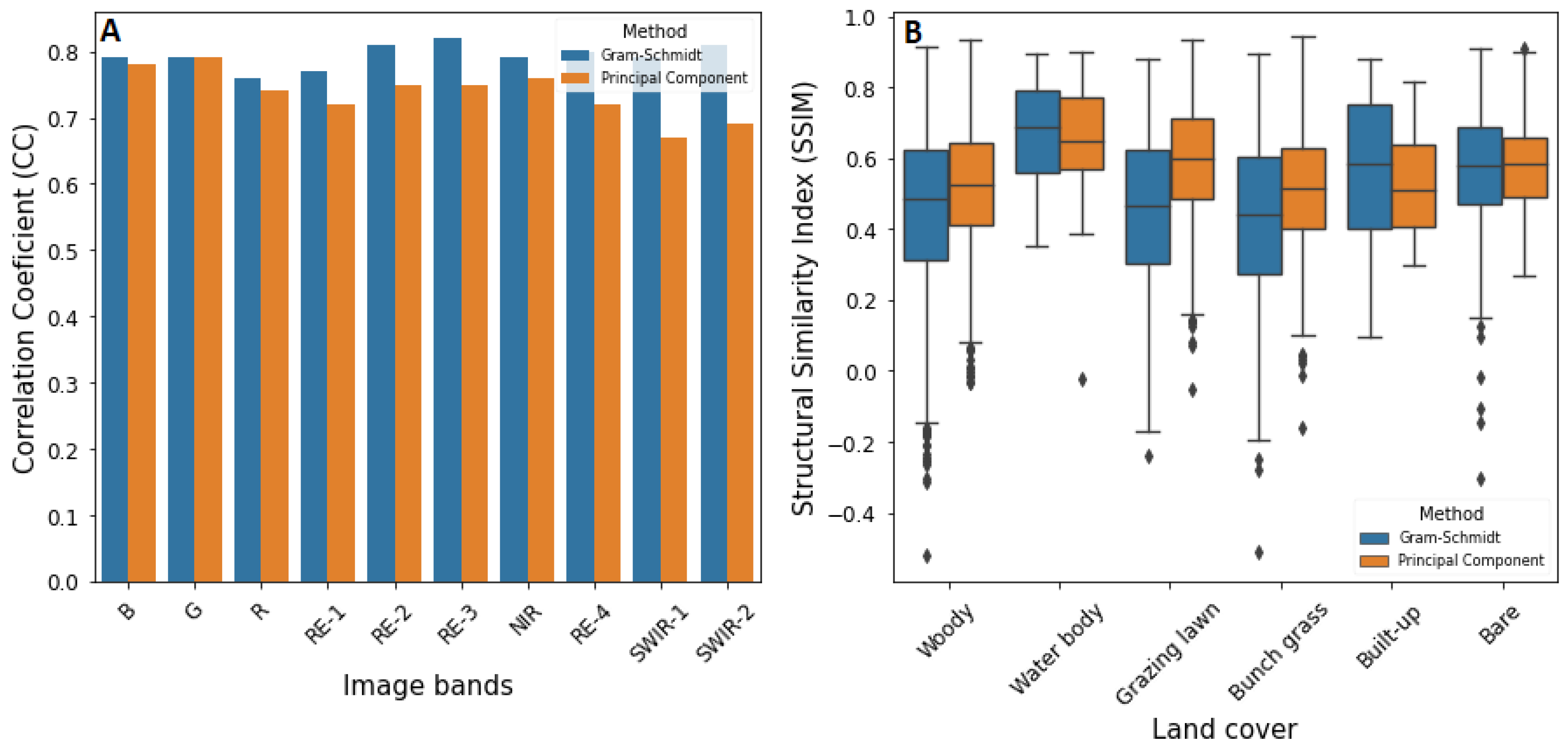

3.1. Image Fusion Accuracy

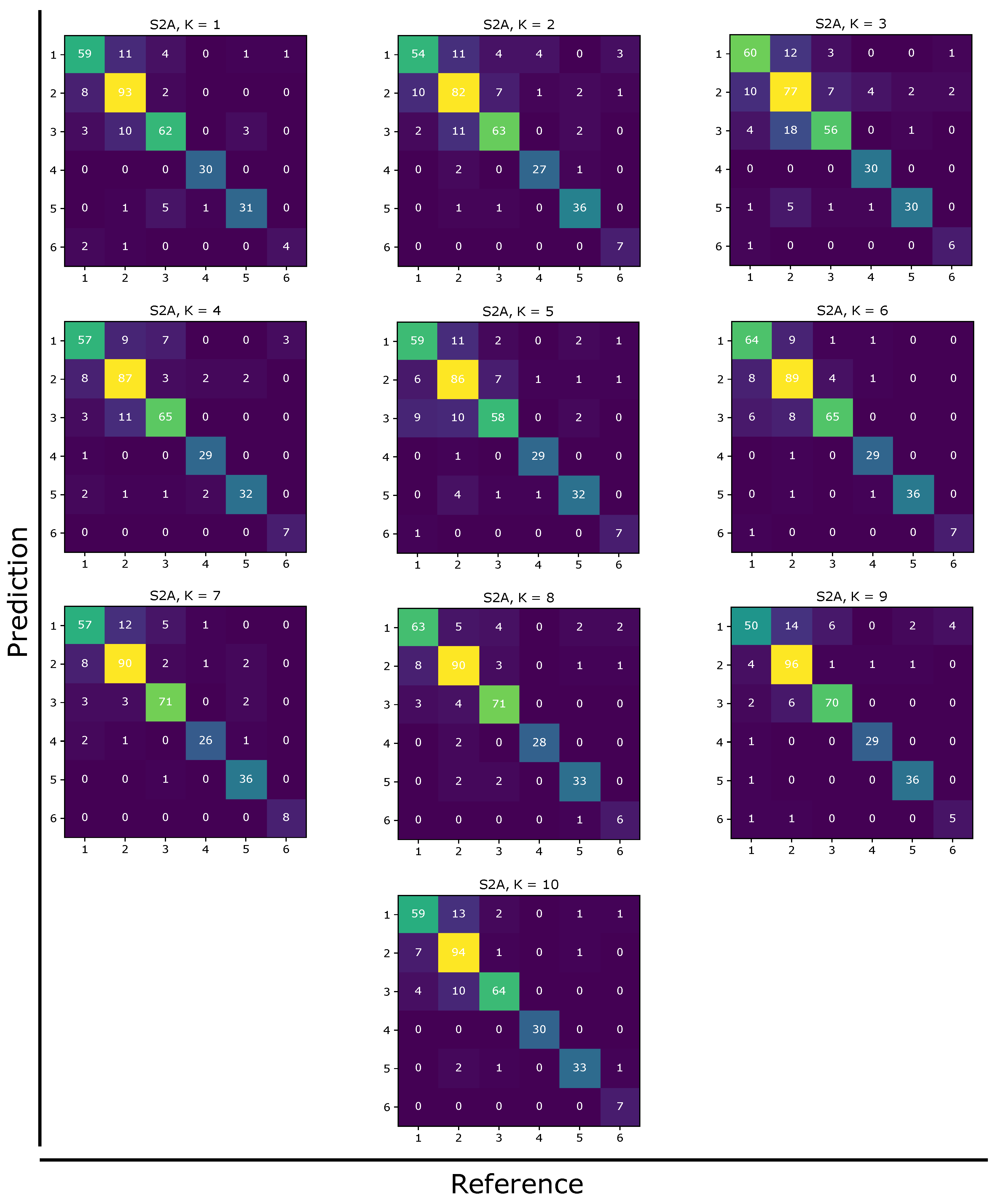

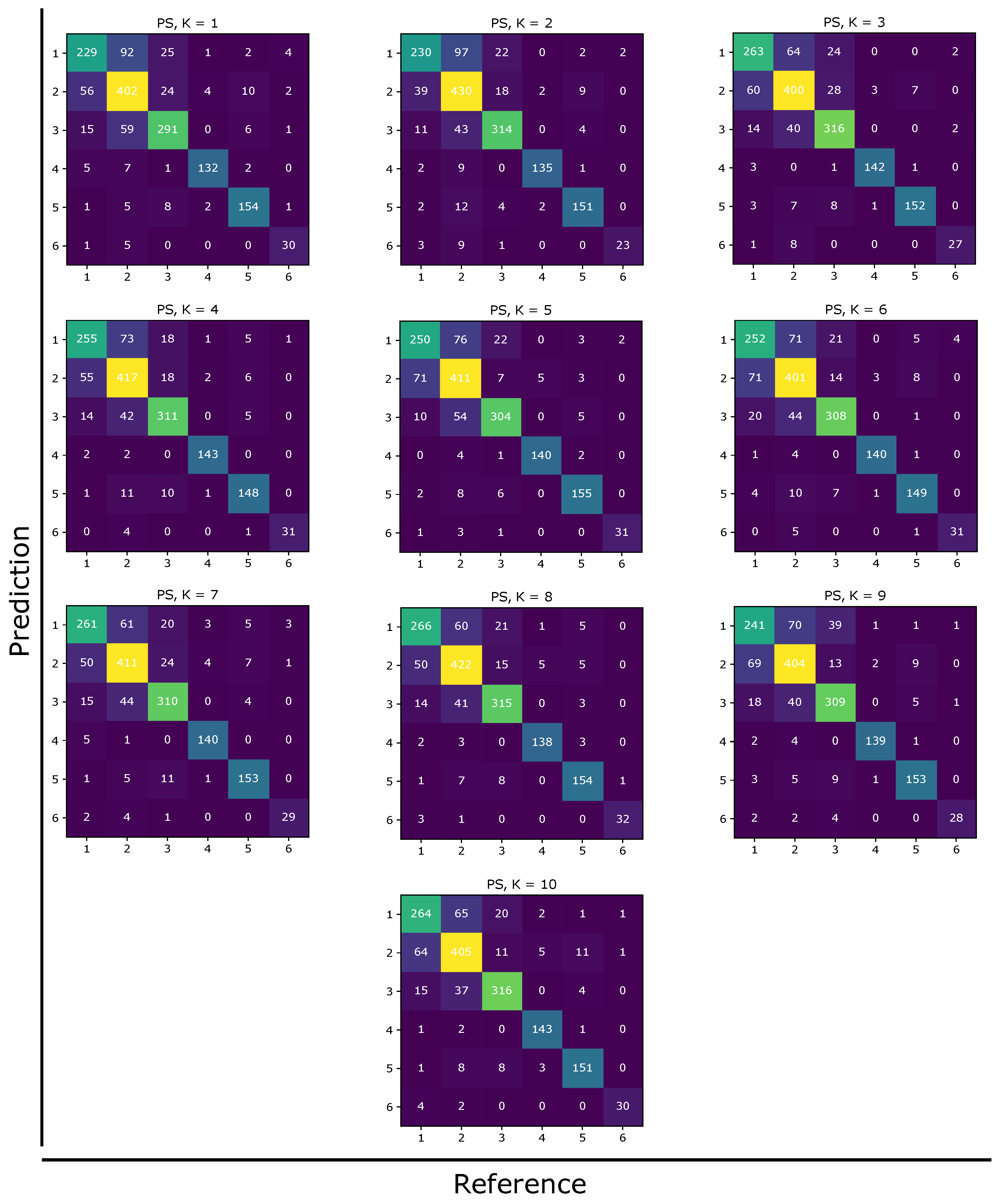

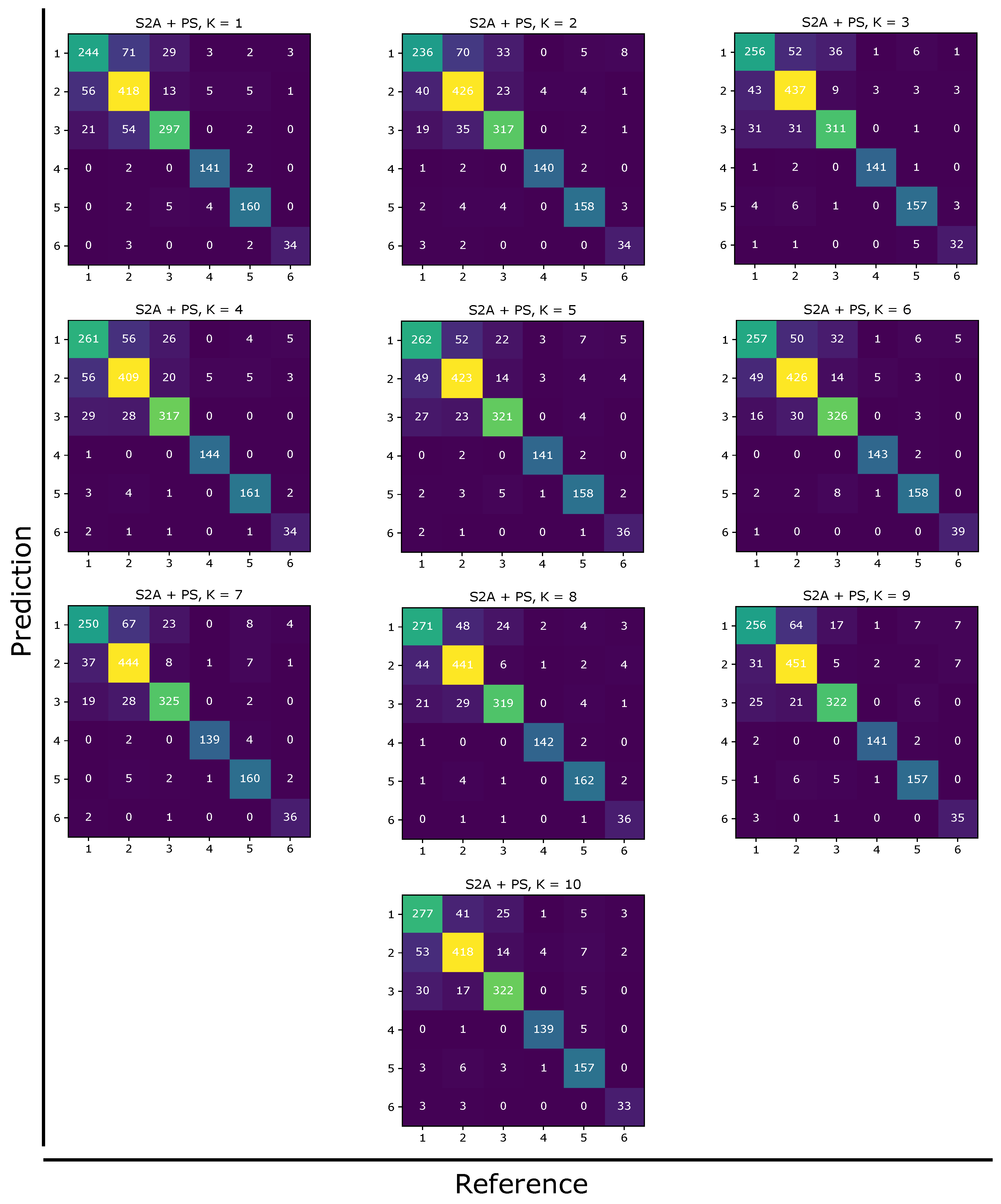

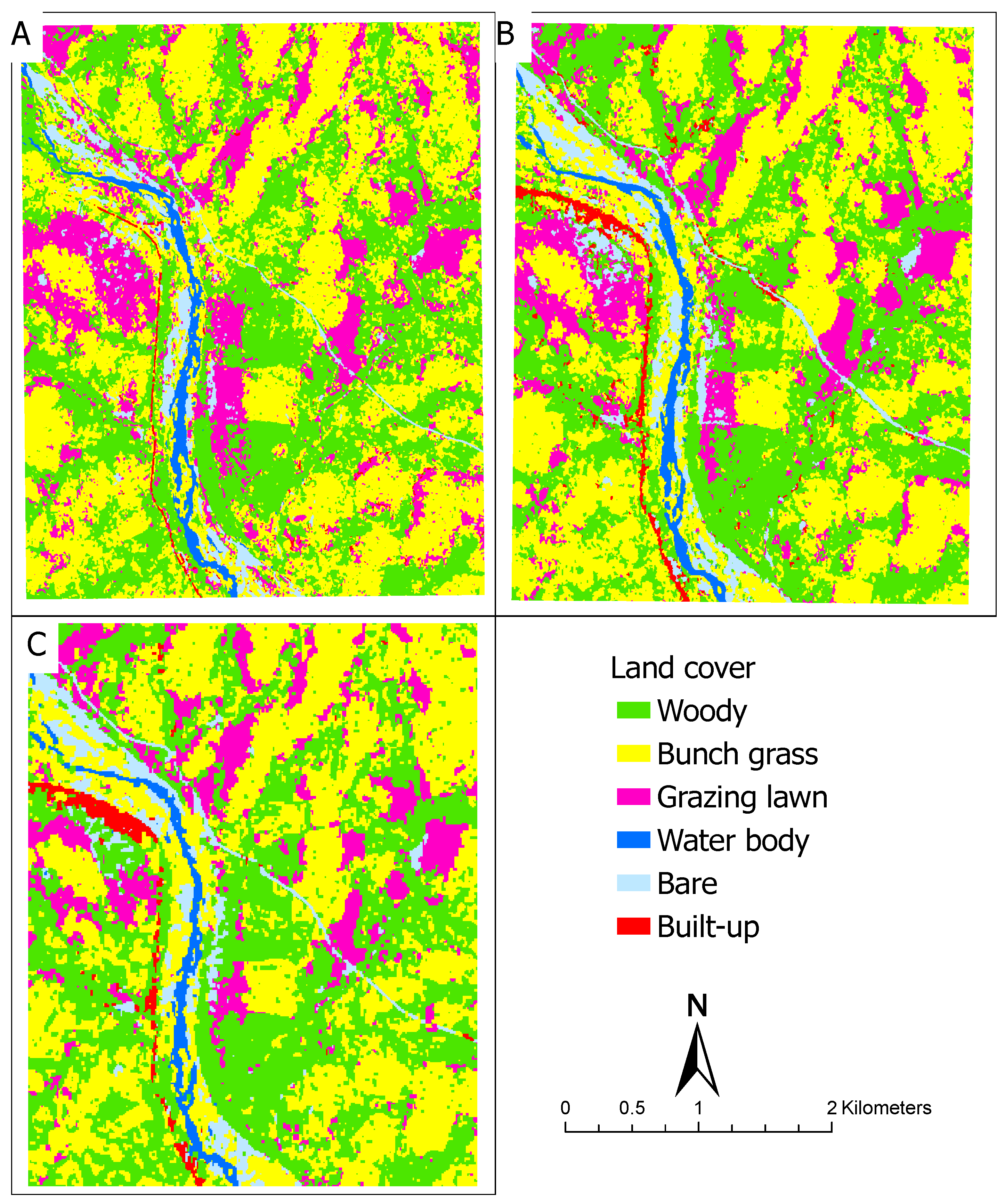

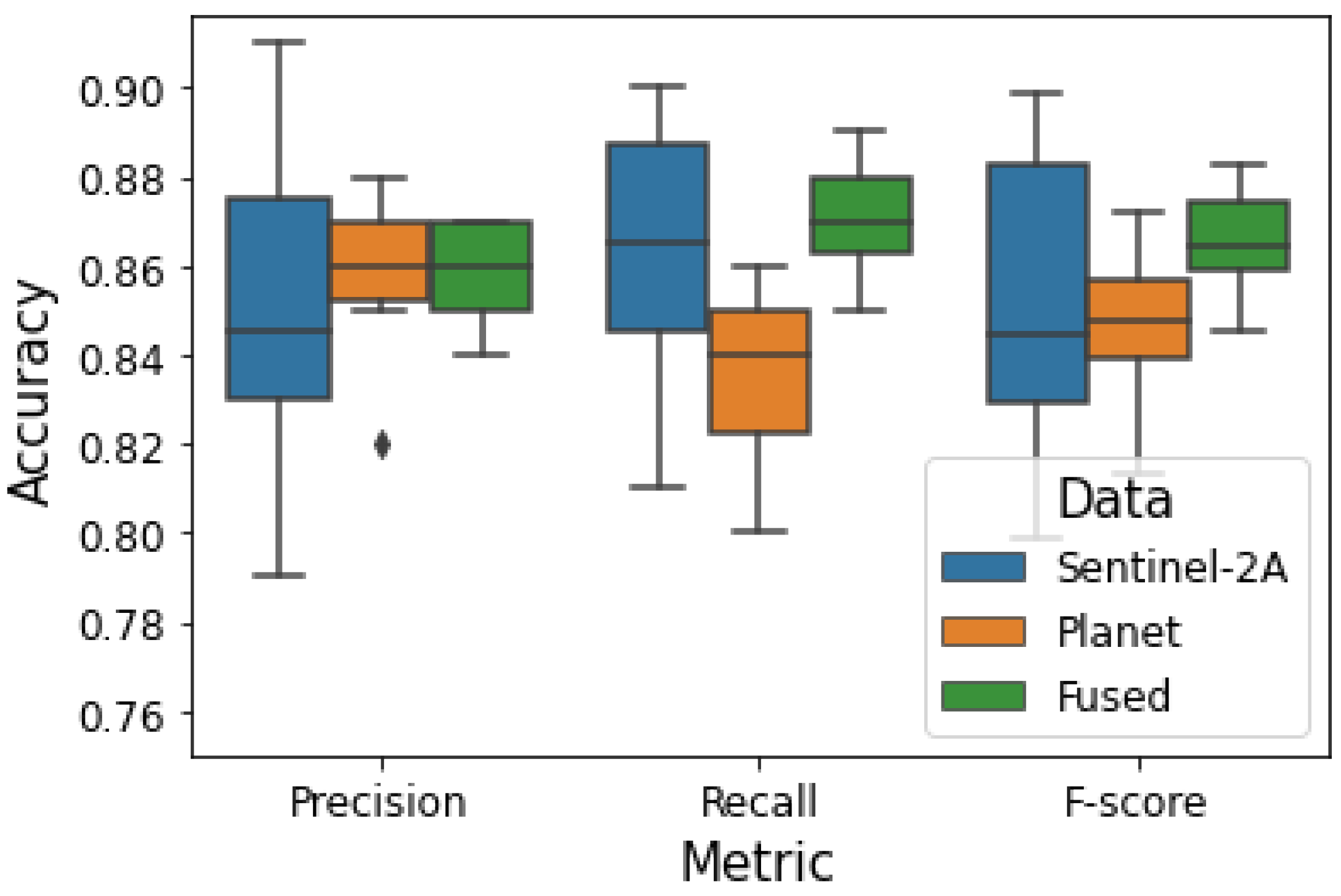

3.2. Land Cover Classification

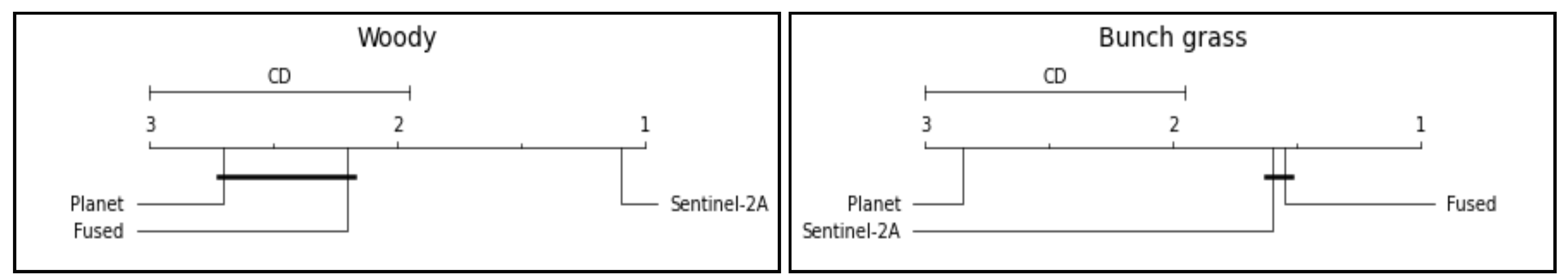

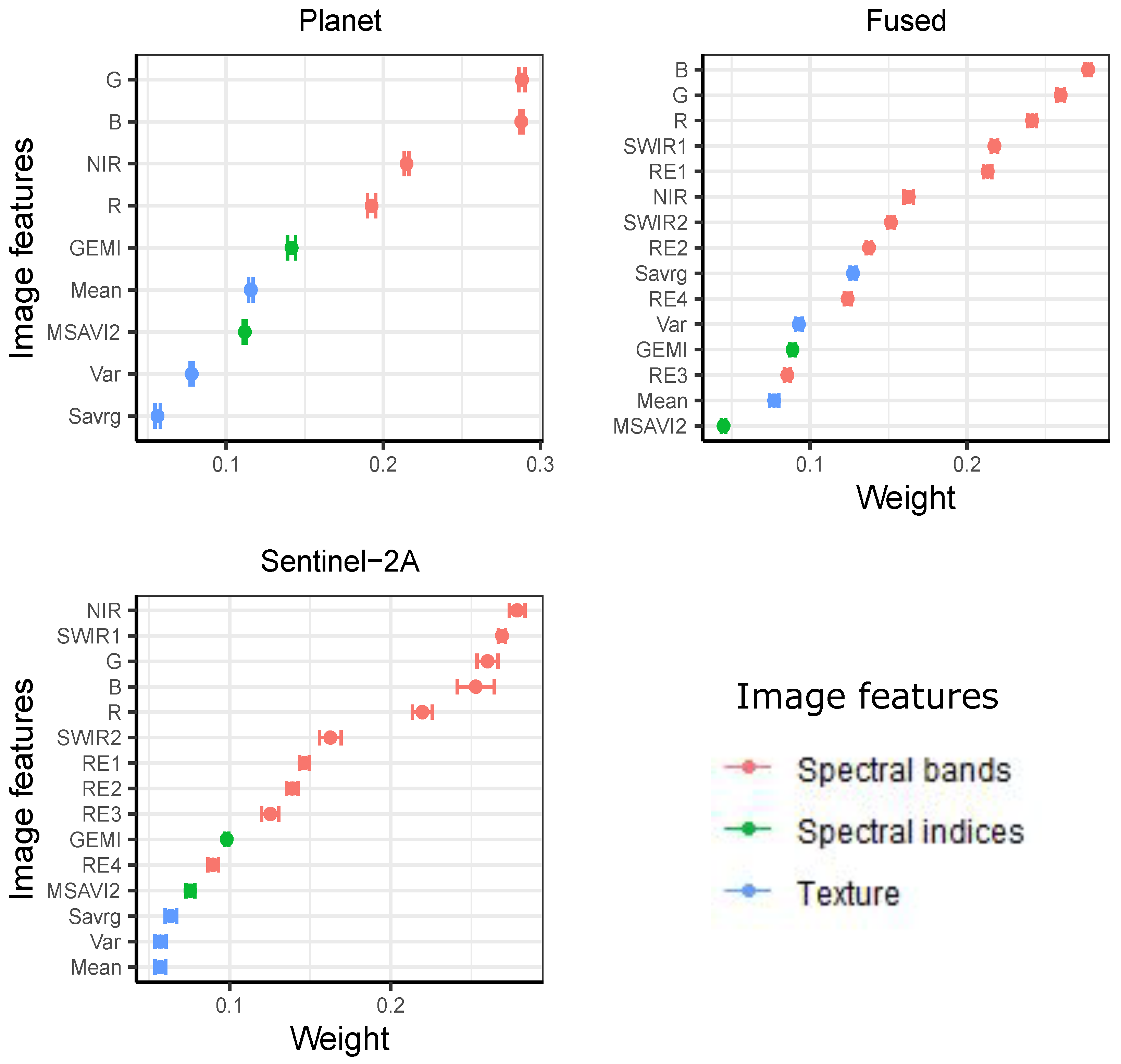

3.3. Feature Importance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

Appendix A.1. Confusion Matrices

References

- Wulder, M.A.; Masek, J.G.; Cohen, W.B.; Loveland, T.R.; Woodcock, C.E. Opening the archive: How free data has enabled the science and monitoring promise of Landsat. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 122, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drusch, M.; Del Bello, U.; Carlier, S.; Colin, O.; Fernandez, V.; Gascon, F.; Hoersch, B.; Isola, C.; Laberinti, P.; Martimort, P.; others. Sentinel-2: ESA’s optical high-resolution mission for GMES operational services. Remote sensing of Environment 2012, 120, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastin, J.F.; Berrahmouni, N.; Grainger, A.; Maniatis, D.; Mollicone, D.; Moore, R.; Patriarca, C.; Picard, N.; Sparrow, B.; Abraham, E.M.; others. The extent of forest in dryland biomes. Science 2017, 356, 635–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, D.M.; Lehmann, C.E.; Strömberg, C.A.; Parr, C.L.; Pennington, R.T.; Sankaran, M.; Ratnam, J.; Still, C.J.; Powell, R.L.; Hanan, N.P.; others. Comment on “The extent of forest in dryland biomes”. Science 2017, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Hill, M.J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Richardson, A.D.; Hufkens, K.; Filippa, G.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Ma, S.; Verfaillie, J.; others. Using data from Landsat, MODIS, VIIRS and PhenoCams to monitor the phenology of California oak/grass savanna and open grassland across spatial scales. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2017, 237, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonakis, E.; Higginbottom, T.P.; Petroulaki, K.; Rabe, A. Optimisation of savannah land cover characterisation with optical and SAR data. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.; Higginbottom, T.P.; Symeonakis, E.; Jones, M. Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 Data for Savannah Land Cover Mapping: Optimising the Combination of Sensors and Seasons. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszta, Ż.; Van De Kerchove, R.; Ramoelo, A.; Cho, M.; Madonsela, S.; Mathieu, R.; Wolff, E. Seasonal separation of African savanna components using worldview-2 imagery: a comparison of pixel-and object-based approaches and selected classification algorithms. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, K.T.; Aplin, P.; Marston, C.G.; Powell, I.; Smit, I.P. Probabilistic mapping and spatial pattern analysis of grazing lawns in Southern African savannahs using WorldView-3 imagery and machine learning techniques. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucini, G.; Saatchi, S.; Hanan, N.; Boone, R.B.; Smit, I. Woody cover and heterogeneity in the savannas of the Kruger National Park, South Africa. 2009 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. IEEE, 2009, Vol. 4, pp. IV–334.

- Bucini, G.; Hanan, N.P.; Boone, R.B.; Smit, I.P.; Saatchi, S.S.; Lefsky, M.A.; Asner, G.P. Woody fractional cover in Kruger National Park, South Africa: remote sensing-based maps and ecological insights. In Ecosystem function in savannas: measurement and modeling at landscape to global scales; CRC Press, 2010; pp. 219–237.

- Cho, M.A.; Mathieu, R.; Asner, G.P.; Naidoo, L.; Van Aardt, J.; Ramoelo, A.; Debba, P.; Wessels, K.; Main, R.; Smit, I.P.; others. Mapping tree species composition in South African savannas using an integrated airborne spectral and LiDAR system. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 125, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, C.G.; Aplin, P.; Wilkinson, D.M.; Field, R.; O’Regan, H.J. Scrubbing up: multi-scale investigation of woody encroachment in a southern African savannah. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planet, T. Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com 2017.

- Francini, S.; McRoberts, R.E.; Giannetti, F.; Mencucci, M.; Marchetti, M.; Scarascia Mugnozza, G.; Chirici, G. Near-real time forest change detection using PlanetScope imagery. European Journal of Remote Sensing 2020, 53, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laso, F.J.; Benítez, F.L.; Rivas-Torres, G.; Sampedro, C.; Arce-Nazario, J. Land cover classification of complex agroecosystems in the non-protected highlands of the Galapagos Islands. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonakis, I.; Verón, S.; Baldi, G.; Banchero, S.; De Abelleyra, D.; Castellanos, G. Savannah land cover characterisation: a quality assessment using Sentinel 1/2, Landsat, PALSAR and PlanetScope 2019.

- Gao, Y.; Mas, J.F. A Comparison of the Performance of Pixel Based and Object Based Classifications over Images with Various Spatial Resolutions 2008.

- Van der Sande, C.; De Jong, S.; De Roo, A. A segmentation and classification approach of IKONOS-2 imagery for land cover mapping to assist flood risk and flood damage assessment. International Journal of applied earth observation and geoinformation 2003, 4, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaschke, T.; Hay, G.J.; Kelly, M.; Lang, S.; Hofmann, P.; Addink, E.; Feitosa, R.Q.; Van der Meer, F.; Van der Werff, H.; Van Coillie, F.; others. Geographic object-based image analysis–towards a new paradigm. ISPRS journal of photogrammetry and remote sensing 2014, 87, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, A.E.; Warner, T.A. Differentiating mine-reclaimed grasslands from spectrally similar land cover using terrain variables and object-based machine learning classification. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2015, 36, 4384–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Cawkwell, F.; Dwyer, E.; Barrett, B.; Green, S. Satellite remote sensing of grasslands: from observation to management. Journal of Plant Ecology 2016, 9, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Chen, B.; Shen, B.; Wang, X.; Yan, Y.; Xu, L.; Xin, X. The classification of grassland types based on object-based image analysis with multisource data. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2019, 72, 318–326. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, Y. The modified IHS method for fusing satellite imagery. ASPRS 2003 Annual Conference Proceedings. Anchorage, Alaska, 2003, pp. 5–9.

- Yocky, D.A. Image merging and data fusion by means of the discrete two-dimensional wavelet transform. JOSA A 1995, 12, 1834–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laben, C.A.; Brower, B.V. Process for enhancing the spatial resolution of multispectral imagery using pan-sharpening, 2000. US Patent 6,011,875.

- Jenerowicz, A.; Woroszkiewicz, M. The pan-sharpening of satellite and UAV imagery for agricultural applications. Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology XVIII. International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2016, Vol. 9998, p. 99981S.

- Rokni, K.; Ahmad, A.; Solaimani, K.; Hazini, S. A new approach for surface water change detection: Integration of pixel level image fusion and image classification techniques. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2015, 34, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Shi, Y.; Liu, B.; Hovis, C.; Duan, Y.; Shi, Z. Finer Classification of Crops by Fusing UAV Images and Sentinel-2A Data. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, F.; Scholes, R.; Eckhardt, H. The abiotic template and its associated vegetation pattern In du Toit JT, Biggs HC, & Rogers KH (Eds.), The Kruger experience: Ecology and management of savanna heterogeneity (pp. 83–129), 2003.

- Hempson, G.P.; Archibald, S.; Bond, W.J.; Ellis, R.P.; Grant, C.C.; Kruger, F.J.; Kruger, L.M.; Moxley, C.; Owen-Smith, N.; Peel, M.J.; others. Ecology of grazing lawns in Africa. Biological Reviews 2015, 90, 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, F.J. A classification of land for management planning in the Kruger National Park. PhD thesis, University of South Africa, 1991.

- Kleynhans, E.J.; Jolles, A.E.; Bos, M.R.; Olff, H. Resource partitioning along multiple niche dimensions in differently sized African savanna grazers. Oikos 2011, 120, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizka, A.; Govender, N.; Higgins, S.I. How to tell a shrub from a tree: A life-history perspective from a S outh A frican savanna. Austral Ecology 2014, 39, 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, J.; Knight, J.; Pelletier, K.; Rampi, L.; Wang, Y. The effects of point or polygon based training data on RandomForest classification accuracy of wetlands. Remote Sensing 2015, 7, 4002–4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, M.; Ma, X.; Cheng, L.; Du, P.; Liu, Y. A review of supervised object-based land-cover image classification. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2017, 130, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeh, Y.; Zhu, X.; Dunkerley, D.; Walker, J.P.; Zhang, Y.; Rozenstein, O.; Manivasagam, V.; Chenu, K. Fusion of Sentinel-2 and PlanetScope time-series data into daily 3 m surface reflectance and wheat LAI monitoring. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2021, 96, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote sensing of Environment 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, J.; Debaecker, V.; Pflug, B.; Main-Knorn, M.; Bieniarz, J.; Mueller-Wilm, U.; Cadau, E.; Gascon, F. Sentinel-2 sen2cor: L2a processor for users. Proceedings Living Planet Symposium 2016. Spacebooks Online, 2016, pp. 1–8.

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE transactions on image processing 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanaki, A.N. Exact global histogram specification optimized for structural similarity. Optical review 2009, 16, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, O.R.; Folorunso, O.; others. A descriptive algorithm for sobel image edge detection. Proceedings of informing science & IT education conference (InSITE). Informing Science Institute California, 2009, Vol. 40, pp. 97–107.

- Roerdink, J.B.; Meijster, A. The watershed transform: Definitions, algorithms and parallelization strategies. Fundamenta informaticae 2000, 41, 187–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X. Segmentation-based image processing system, 2012. US Patent 8,260,048.

- Pinty, B.; Verstraete, M. GEMI: a non-linear index to monitor global vegetation from satellites. Vegetatio 1992, 101, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laosuwan, T.; Uttaruk, P. Estimating tree biomass via remote sensing, MSAVI 2, and fractional cover model. IETE Technical Review 2014, 31, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralick, R.M.; Shanmugam, K.; Dinstein, I.H. Textural features for image classification. IEEE Transactions on systems, man, and cybernetics 1973, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, W.K. Introduction to Digital Image Processing, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Ranton, USA, 2013; p. 756. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep learning; MIT press: Cambridge, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Bischof, H.; Schneider, W.; Pinz, A.J. Multispectral classification of Landsat-images using neural networks. IEEE transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 1992, 30, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, Y.; Raja, S.K. On the classification of multispectral satellite images using the multilayer perceptron. Pattern Recognition 2003, 36, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, N.; Hinton, G.; Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Salakhutdinov, R. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The journal of machine learning research 2014, 15, 1929–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980 2014. arXiv:1412.6980. [CrossRef]

- Congalton, R.G.; Green, K. Assessing the accuracy of remotely sensed data: principles and practices, 3rd ed.; CRC press: Boca Ranton, USA, 2019; p. 346. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. Journal of the american statistical association 1937, 32, 675–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. A comparison of alternative tests of significance for the problem of m rankings. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1940, 11, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demšar, J. Statistical comparisons of classifiers over multiple data sets. The Journal of Machine Learning Research 2006, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nemenyi, P.B. Distribution-free multiple comparisons.; Princeton University, 1963.

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; others. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. the Journal of machine Learning research 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Sarp, G. Spectral and spatial quality analysis of pan-sharpening algorithms: A case study in Istanbul. European Journal of Remote Sensing 2014, 47, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushparaj, J.; Hegde, A.V. Evaluation of pan-sharpening methods for spatial and spectral quality. Applied Geomatics 2017, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah, K.T.; Nölke, N.; Freudenberg, M.; Diwakara, B.; Tewari, V.; Kleinn, C. Spatial resolution and landscape structure along an urban-rural gradient: Do they relate to remote sensing classification accuracy?–A case study in the megacity of Bengaluru, India. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 2018, 12, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forkuor, G.; Dimobe, K.; Serme, I.; Tondoh, J.E. Landsat-8 vs. Sentinel-2: examining the added value of sentinel-2’s red-edge bands to land-use and land-cover mapping in Burkina Faso. GIScience & remote sensing 2018, 55, 331–354. [Google Scholar]

- Otunga, C.; Odindi, J.; Mutanga, O.; Adjorlolo, C. Evaluating the potential of the red edge channel for C3 (Festuca spp.) grass discrimination using Sentinel-2 and Rapid Eye satellite image data. Geocarto International 2019, 34, 1123–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngadze, F.; Mpakairi, K.S.; Kavhu, B.; Ndaimani, H.; Maremba, M.S. Exploring the utility of Sentinel-2 MSI and Landsat 8 OLI in burned area mapping for a heterogenous savannah landscape. Plos one 2020, 15, e0232962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, R.; Landry, S. A comparative analysis of high spatial resolution IKONOS and WorldView-2 imagery for mapping urban tree species. Remote Sensing of Environment 2012, 124, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, I.T.; McDermid, G.J.; Silveira, E.M.; Hird, J.N.; Domingos, B.I.; Acerbi Júnior, F.W. Spatial Agreement among Vegetation Disturbance Maps in Tropical Domains Using Landsat Time Series. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, R.; Aplin, P.; Boyd, D.S. Mapping complex urban land cover from spaceborne imagery: The influence of spatial resolution, spectral band set and classification approach. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanprasit, C.; Srichai, N. Impacts of spatial resolution on land cover classification. Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Advanced Network 2012, 33, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, K. Landcover classification in a heterogenous savanna environment: investigating the performance of an artificial neural network and the effect of image resolution. PhD thesis, 2007.

- Pandey, P.; Kington, J.; Kanwar, A.; Curdoglo, M. Addendum to Planet Basemaps Product Specifications: NICFI Basemaps. Technical Report Revision: v02, Planet Labs, 2021.

- Mitchard, E.T.; Flintrop, C.M. Woody encroachment and forest degradation in sub-Saharan Africa’s woodlands and savannas 1982–2006. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2013, 368, 20120406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, N.; Lehmann, C.E.; Murphy, B.P.; Durigan, G. Savanna woody encroachment is widespread across three continents. Global change biology 2017, 23, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, M.F.; Staver, A.C. Fire prevents woody encroachment only at higher-than-historical frequencies in a South African savanna. Journal of Applied Ecology 2017, 54, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaran, M. Droughts and the ecological future of tropical savanna vegetation. Journal of Ecology 2019, 107, 1531–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, M.F.; Wigley, B.J.; Wigley-Coetsee, C.; Carla Staver, A. Could drought constrain woody encroachers in savannas? African Journal of Range & Forage Science 2020, 37, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Tingley, M.W.; Case, M.F.; Coetsee, C.; Kiker, G.A.; Scholtz, R.; Venter, F.J.; Staver, A.C. Woody encroachment happens via intensification, not extensification, of species ranges in an African savanna. Ecological Applications 2021, e02437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, J.E.; Parr, C.L.; Mangena, E.; Archibald, S. Droughts decouple African savanna grazers from their preferred forage with consequences for grassland productivity. Ecosystems 2020, 23, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land cover | Reference samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Name | Description | Number of polygons | Area coverage () |

| 1 | Woody | Woody vegetation components including trees and shrubs at different phenological stages. |

1908 | 0.071 |

| 2 | Bunch grass | Tall grass patches often with upright growth form and dense distribution that are >20 cm in height. |

679 | 0.101 |

| 3 | Grazing lawn | Short grass patches with stoloniferous growth form and <20 cm in height, often sparsely distributed. |

457 | 0.077 |

| 4 | Water body | Water bodies occurring within the landscapes including rivers, streams and reservoirs. The landscape is mainly drained by the Sabie River. |

56 | 0.03 |

| 5 | Bare | Patches of exposed soil including dusty trails and rocky outcrops. | 262 | 0.034 |

| 6 | Built-up | Built artificial structures within the landscape, mostly asphalt and concrete coated surfaces such as roads and bridges and buildings. |

36 | 0.007 |

| Data | Land cover | Precision | Recall | F-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sentinel-2A | Woody | |||

| Bunch grass | ||||

| Grazing lawn | ||||

| Water body | ||||

| Bare | ||||

| Built-up | ||||

| Planet | Woody | |||

| Bunch grass | ||||

| Grazing lawn | ||||

| Water body | ||||

| Bare | ||||

| Built-up | ||||

| Fused | Woody | |||

| Bunch grass | ||||

| Grazing lawn | ||||

| Water body | ||||

| Bare | ||||

| Built-up |

| Land cover | Friedman statistic () | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Woody | 14.11 | 0.00 |

| Bunch grass | 12.05 | 0.00 |

| Grazing lawn | 3.44 | 0.18 |

| Water body | 6.06 | 0.05 |

| Bare | 4.15 | 0.13 |

| Built-up | 2.00 | 0.37 |

| All | 5.60 | 0.06 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).