Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

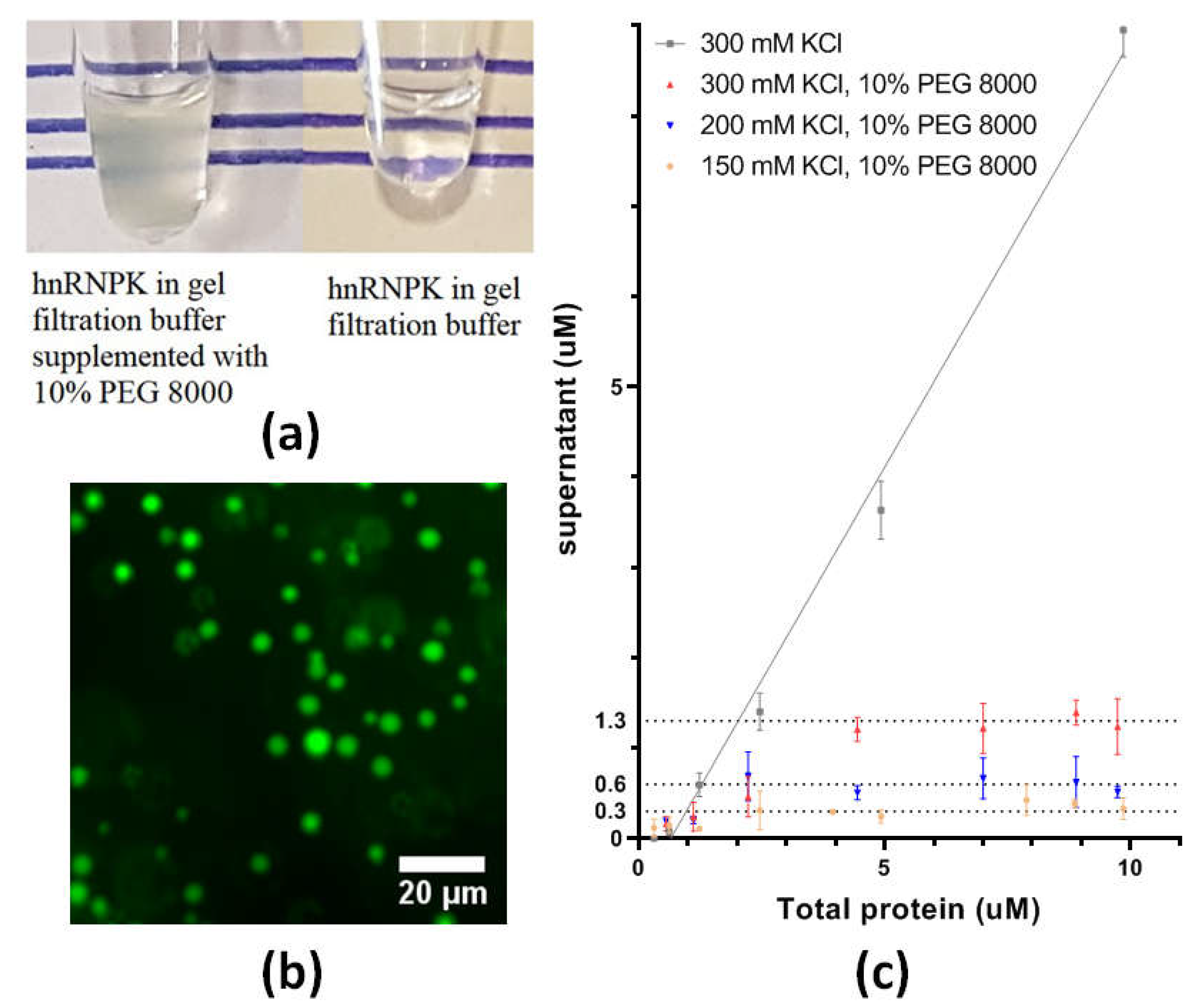

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear protein K (hnRNPK) is an RNA-binding protein with low-complexity domains (LCDs) that regulate its behavior under stress conditions. This study demonstrates the ability to control hnRNPK’s transitions into four distinct material states—monomer, soluble aggregate, liquid droplet, and fibrillar hydrogel—by modulating environmental factors such as temperature and protein concentration. Importantly, the phase-separated and hydrogel states are newly identified for hnRNPK, marking a significant advancement in understanding its material properties. A combination of biophysical techniques, including DLS and SEC-LS, was used to further characterize hnRNPK in monomeric and soluble aggregate states. Structural methods, such as SANS, SAXS, and TEM, revealed the elongated morphology of the hnRNPK monomer. Environmental perturbations, such as decreased temperature or crowding agents, drove hnRNPK into phase-separated or gel-like states, each with distinct biophysical characteristics. These novel states were further analyzed using SEM, X-ray diffraction, and fluorescence microscopy. Collectively, these results demonstrate the complex behaviors of hnRNPK under different conditions and illustrate the properties of the protein in each material state. Transitions of hnRNPK upon condition changes could potentially affect functions of hnRNPK, playing a significant role in regulation of hnRNPK-involved processes in the cell.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Unstable Nature of hnRNPK

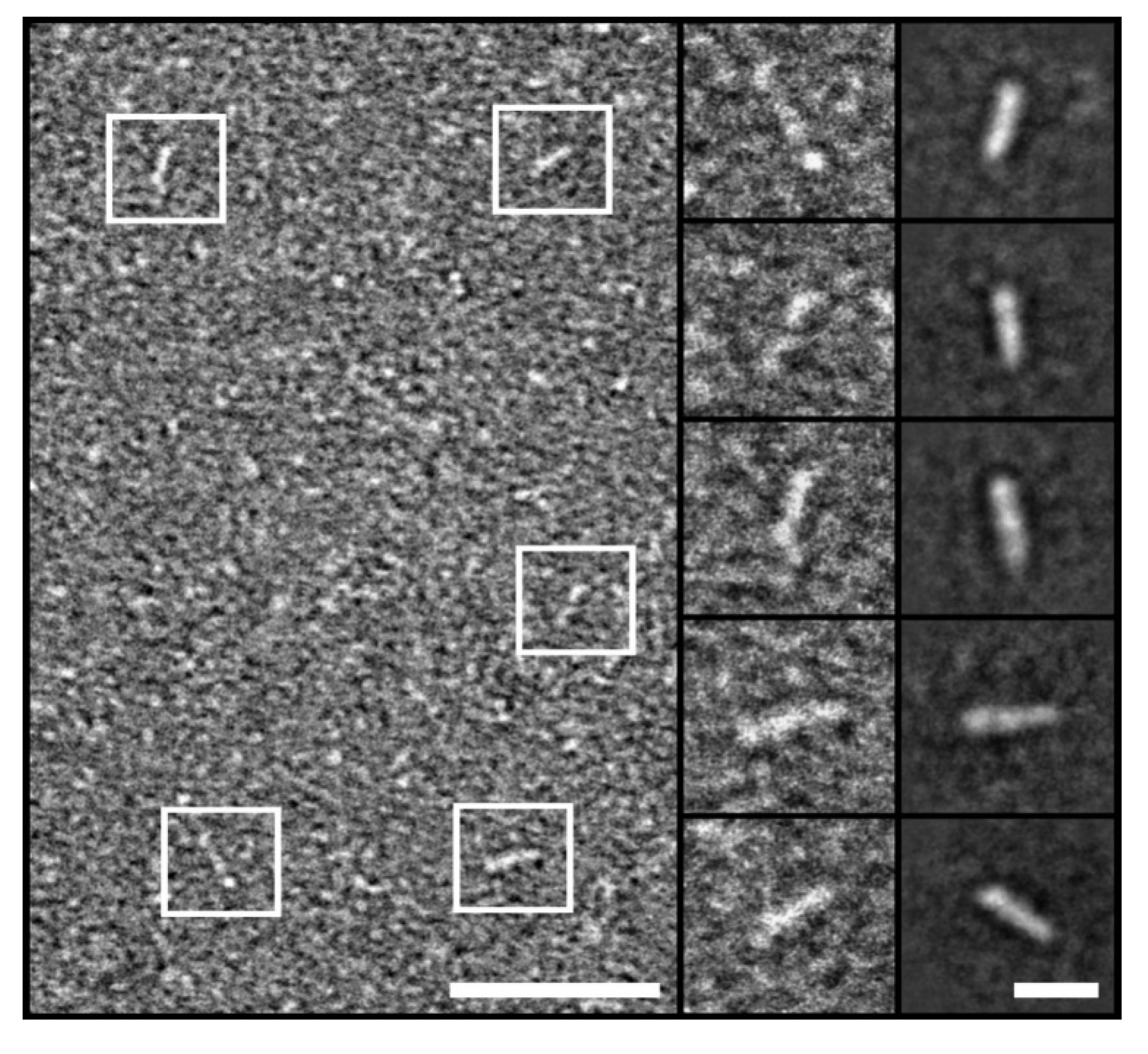

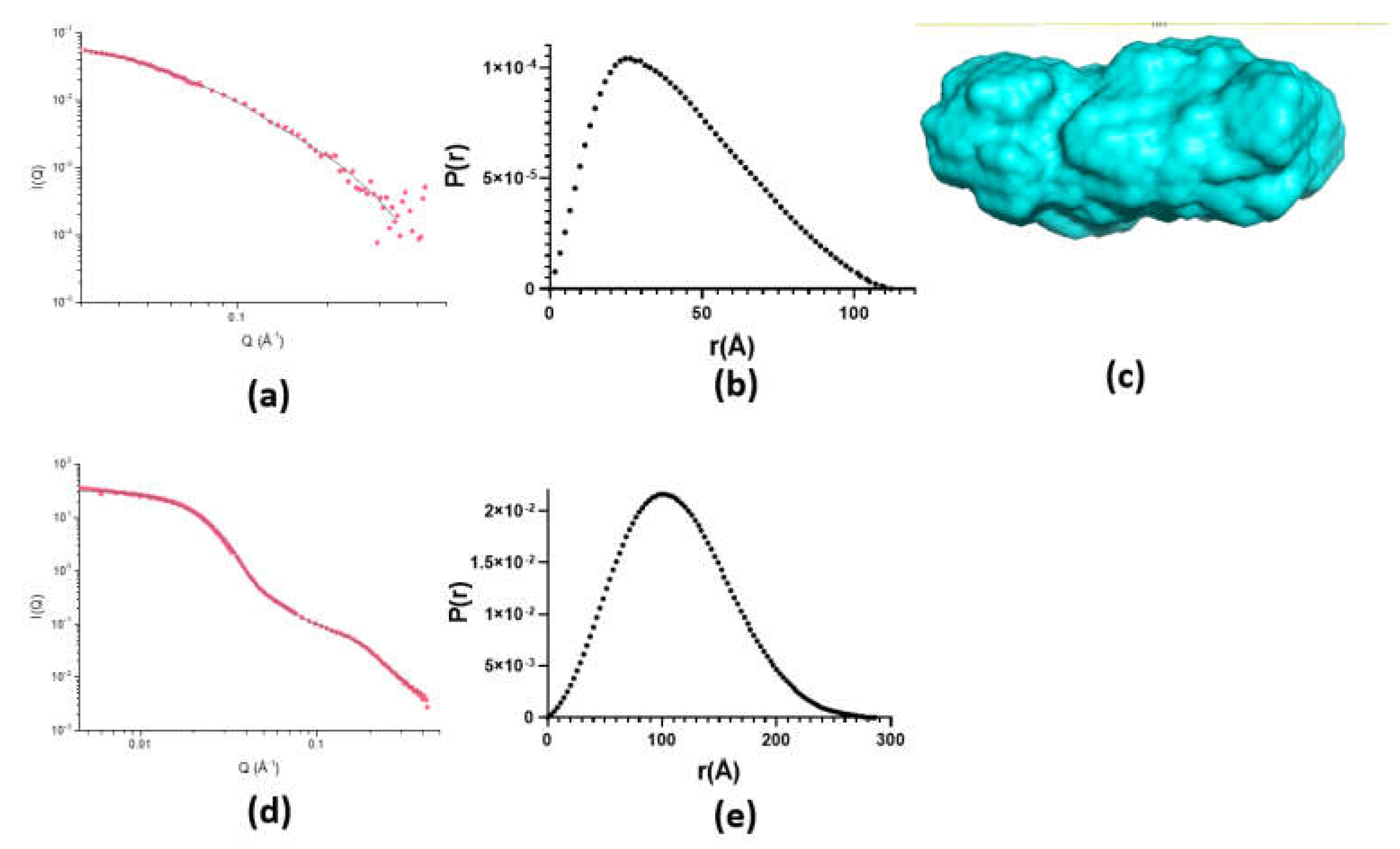

2.2. Monomeric State of hnRNPK

2.3. Aggregation State of hnRNPK

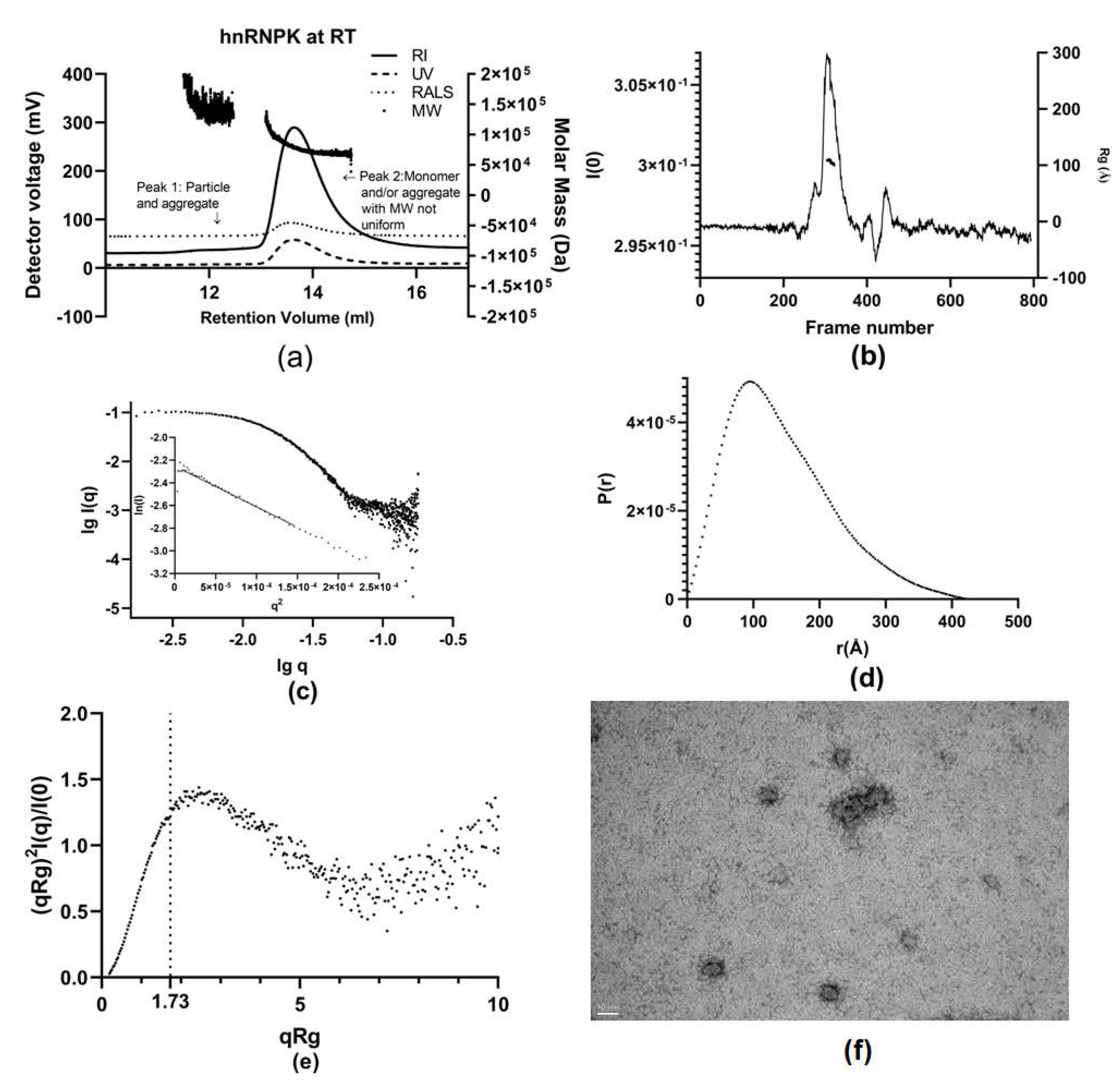

2.4. Characterization of hnRNPK Monomer in Mixture with Aggregates

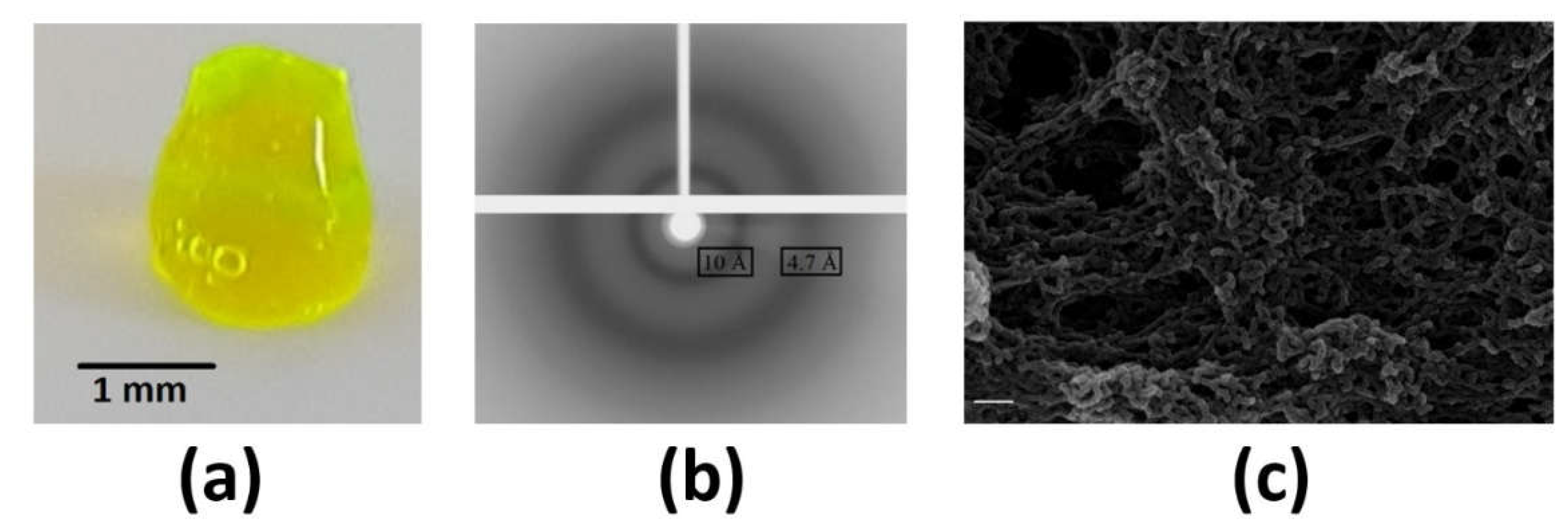

2.5. Hydrogel of hnRNPK

2.6. Phase Separation of hnRNPK

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Protein Expression and Purification

4.2. Gelation

4.3. X-ray Diffraction

4.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

4.5. Fluorescence Microscopy

4.6. Saturation Concentration Determination by Centrifugation

4.7. Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

4.8. Size-Exclusion Chromatography Coupled to Light Scattering (SEC-LS)

4.9. Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS)

4.10. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS)

4.11. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| hnRNPK | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| SEC-LS | Size-exclusion chromatography coupled to light scattering |

| SAXS | Small-angle X-ray scattering |

| SANS | small-angle neutron scattering |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| LCD | Low complexity domain |

| KH | K-homologous domains |

| KI | K-interactive region |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| DTT | Dithiothreitol |

| MM | Molecular mass |

| Csat | Saturation concentration |

Appendix

References

- Zimmerman, S.B.; Trach, S.O. Estimation of macromolecule concentrations and excluded volume effects for the cytoplasm of Escherichia coli. 2005, 222, 599–620. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, I.M.; Turoverov, K.K.; Uversky, V.N. What Macromolecular Crowding Can Do to a Protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 23090–23140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leibly, D.J.; Nguyen, T.N.; Kao, L.T.; Hewitt, S.N.; Barrett, L.K.; Van Voorhis, W.C. Stabilizing Additives Added during Cell Lysis Aid in the Solubilization of Recombinant Proteins. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e52482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foit, L.; Morgan, G.J.; Kern, M.J.; Steimer, L.R.; von Hacht, A.A.; Titchmarsh, J.; Warriner, S.L.; Radford, S.E.; Bardwell, J.C. Optimizing Protein Stability In Vivo. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arakawa, T. and S.N. Timasheff, Theory of protein solubility. Methods Enzymol, 1985. 114: p. 49-77.

- Schmidt, C.L.A. , Proteins, Amino Acids and Peptides as Ions and Dipolar Ions (Cohn, Edwin J.; Edsall, John T.). Journal of Chemical Education, 1943. 20(8): p. 415.

- Rousseau, F. Schymkowitz, and L. Serrano, Protein aggregation and amyloidosis: confusion of the kinds? Curr Opin Struct Biol, 2006. 16(1): p. 118-26.

- Jonker, A.M.; Löwik, D.W.P.M.; van Hest, J.C.M. Peptide- and Protein-Based Hydrogels. Chem. Mater. 2011, 24, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeynaems, S.; Alberti, S.; Fawzi, N.L.; Mittag, T.; Polymenidou, M.; Rousseau, F.; Schymkowitz, J.; Shorter, J.; Wolozin, B.; van den Bosch, L.; et al. Protein Phase Separation: A New Phase in Cell Biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Villanueva, J.F.; Díaz-Molina, R.; García-González, V. Protein Folding and Mechanisms of Proteostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 17193–17230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, S.F.; Lee, H.O.; Hyman, A.A.; Rosen, M.K. Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Brangwynne, C.P. Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 2017, 357, eaaf4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S. The wisdom of crowds: regulating cell function through condensed states of living matter. J. Cell Sci. 2017, 130, 2789–2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balchin, D.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Hartl, F.U. In vivo aspects of protein folding and quality control. Science 2016, 353, aac4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiti, F.; Dobson, C.M. Protein Misfolding, Amyloid Formation, and Human Disease: A Summary of Progress Over the Last Decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 27–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.W.; Mittag, T. Relationship of Sequence and Phase Separation in Protein Low-Complexity Regions. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 2478–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Lin, Y.; McKnight, S.L. Cross-β polymerization and hydrogel formation by low-complexity sequence proteins. Methods 2017, 126, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, W.; Han, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, P.; Xu, H. Post-translational modification control of RNA-binding protein hnRNPK function. Open Biol. 2019, 9, 180239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, M.Y.; Lammer, N.C.; Batey, R.T.; Wuttke, D.S. hnRNPK recognition of the B motif of Xist and other biological RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 9320–9335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomsztyk, K.; Denisenko, O.; Ostrowski, J. hnRNP K: One protein multiple processes. BioEssays 2004, 26, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wootton, J.C.; Federhen, S. Statistics of local complexity in amino acid sequences and sequence databases. 2001, 17, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarnot, P.; Ziemska-Legiecka, J.; Dobson, L.; Merski, M.; Mier, P.; A Andrade-Navarro, M.; Hancock, J.M.; Dosztányi, Z.; Paladin, L.; Necci, M.; et al. PlaToLoCo: the first web meta-server for visualization and annotation of low complexity regions in proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W77–W84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poenisch, M.; Metz, P.; Blankenburg, H.; Ruggieri, A.; Lee, J.-Y.; Rupp, D.; Rebhan, I.; Diederich, K.; Kaderali, L.; Domingues, F.S.; et al. Identification of HNRNPK as Regulator of Hepatitis C Virus Particle Production. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz, B.; Lilie, H.; Vries, I.S.N.-D.; Urlaub, H.; Wahle, E.; Ostareck-Lederer, A.; Ostareck, D.H. Biophysical and biochemical analysis of hnRNP K: arginine methylation, reversible aggregation and combinatorial binding to nucleic acids. Biol. Chem. 2014, 395, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backe, P.H.; Messias, A.C.; Ravelli, R.B.; Sattler, M.; Cusack, S. X-Ray Crystallographic and NMR Studies of the Third KH Domain of hnRNP K in Complex with Single-Stranded Nucleic Acids. Structure 2005, 13, 1055–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oromendia, A.B.; Dodgson, S.E.; Amon, A. Aneuploidy causes proteotoxic stress in yeast. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 2696–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAlary, L.; Plotkin, S.S.; Yerbury, J.J.; Cashman, N.R. Prion-Like Propagation of Protein Misfolding and Aggregation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascarina, S.M.; King, D.C.; Nishimura, E.O.; Ross, E.D. LCD-Composer: an intuitive, composition-centric method enabling the identification and detailed functional mapping of low-complexity domains. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2021, 3, lqab048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Gong, R.; He, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, T.; Luo, S.-Z. Low-complexity domain of U1-70K modulates phase separation and aggregation through distinctive basic-acidic motifs. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsching, K.J.; Yang, Y.; Pogue, E.M.; Rayman, J.B.; Kandel, E.R.; McDermott, A.E. Micellar TIA1 with folded RNA binding domains as a model for reversible stress granule formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 31832–31837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig, S.; Kong, G.; Mannen, T.; Sadowska, A.; Kobelke, S.; Blythe, A.; Knott, G.J.; Iyer, K.S.; Ho, D.; Newcombe, E.A.; et al. Prion-like domains in RNA binding proteins are essential for building subnuclear paraspeckles. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 210, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.S., et al., TDP-43 is intrinsically aggregation-prone, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-linked mutations accelerate aggregation and increase toxicity. J Biol Chem, 2009. 284(30): p. 20329-39.

- Alberti, S.; Saha, S.; Woodruff, J.B.; Franzmann, T.M.; Wang, J.; Hyman, A.A. A User’s Guide for Phase Separation Assays with Purified Proteins. 2018, 430, 4806–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.K., Minimizing Heterogeneity of Protein Samples for Metal Transporter Proteins Using SAXS and Metal Radioisotopes. Methods Mol Biol, 2021. 2199: p. 151–156.

- Hajizadeh, N.R.; Franke, D.; Jeffries, C.M.; Svergun, D.I. Consensus Bayesian assessment of protein molecular mass from solution X-ray scattering data. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, D.; Svergun, D.I. DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J Appl Crystallogr, 2009. 42(Pt 2): p. 342-346.

- Volkov, V.V.; Svergun, D.I. Uniqueness of ab initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 860–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarachan, K.L.; Curtis, J.E.; Krueger, S. Small-angle scattering contrast calculator for protein and nucleic acid complexes in solution. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2013, 46, 1889–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupiac, C.; Bonetti, M.; Pin, S.; Calmettes, P. High-pressure effects on horse heart metmyoglobin studied by small-angle neutron scattering. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 4731–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanOudenhove, J.; Anderson, E.; Krueger, S.; Cole, J.L. Analysis of PKR Structure by Small-Angle Scattering. 2009, 387, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, D.T.; Kato, M.; Lin, Y.; Thurber, K.R.; Hung, I.; McKnight, S.L.; Tycko, R. Structure of FUS Protein Fibrils and Its Relevance to Self-Assembly and Phase Separation of Low-Complexity Domains. 2017, 171, 615–627. e16. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Kato, M.; Wu, L.C.; Lin, Y.; Ding, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Y.; McKnight, S.L. The LC Domain of hnRNPA2 Adopts Similar Conformations in Hydrogel Polymers, Liquid-like Droplets, and Nuclei. Cell 2015, 163, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, O.S.; Serpell, L.C. Structures for amyloid fibrils. The FEBS Journal, 2005. 272(23): p. 5950-5961.

- Ross, C.A.; Poirier, M.A. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, S10–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbinden, A.; Pérez-Berlanga, M.; De Rossi, P.; Polymenidou, M. Phase Separation and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Disturbance in the Force. Dev. Cell 2020, 55, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.J.; Pardeshi, N.N.; Mulder, A.M.; Mulligan, S.K.; Quispe, J.; On, K.; Carragher, B.; Potter, C.S.; Carpenter, J.F.; Schneemann, A. Transmission Electron Microscopy as an Orthogonal Method to Characterize Protein Aggregates. J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 104, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, A.H.; Nakagawa, S.; Hirose, T.; Bond, C.S. Paraspeckles: Where Long Noncoding RNA Meets Phase Separation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 43, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molliex, A.; Temirov, J.; Lee, J.; Coughlin, M.; Kanagaraj, A.P.; Kim, H.J.; Mittag, T.; Taylor, J.P. Phase Separation by Low Complexity Domains Promotes Stress Granule Assembly and Drives Pathological Fibrillization. Cell 2015, 163, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, S.; Gladfelter, A.; Mittag, T. Considerations and Challenges in Studying Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation and Biomolecular Condensates. Cell 2019, 176, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julius, K.; Weine, J.; Gao, M.; Latarius, J.; Elbers, M.; Paulus, M.; Tolan, M.; Winter, R. Impact of Macromolecular Crowding and Compression on Protein–Protein Interactions and Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation Phenomena. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 1772–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaum-Garfinkle, S. Matter over mind: Liquid phase separation and neurodegeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 7160–7168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroo, E.; Koopman, M.; Nollen, E.A.A.; Mata-Cabana, A. Cellular Regulation of Amyloid Formation in Aging and Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, T.; Alshareedah, I.; Wang, W.; Ngo, J.; Moosa, M.M.; Banerjee, P.R. Molecular Crowding Tunes Material States of Ribonucleoprotein Condensates. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, S.; Wang, G.; Randle, S.J.; Ruggeri, F.S.; Varela, J.A.; Lin, J.Q.; Phillips, E.C.; Miyashita, A.; Williams, D.; Ströhl, F.; et al. FUS Phase Separation Is Modulated by a Molecular Chaperone and Methylation of Arginine Cation-π Interactions. Cell 2018, 173, 720–734.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George-Hyslop, P.S.; Lin, J.Q.; Miyashita, A.; Phillips, E.C.; Qamar, S.; Randle, S.J.; Wang, G. The physiological and pathological biophysics of phase separation and gelation of RNA binding proteins in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and fronto-temporal lobar degeneration. Brain Res. 2018, 1693, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A., et al., A single N-terminal phosphomimic disrupts TDP-43 polymerization, phase separation, and RNA splicing. EMBO J, 2018. 37(5).

- McGurk, L.; Gomes, E.; Guo, L.; Mojsilovic-Petrovic, J.; Tran, V.; Kalb, R.G.; Shorter, J.; Bonini, N.M. Poly(ADP-Ribose) Prevents Pathological Phase Separation of TDP-43 by Promoting Liquid Demixing and Stress Granule Localization. 71. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Yu, D.; Gu, R.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jaganathan, A.; Yang, X.; Yu, M.; Babault, N.; Zhao, C.; et al. Roles of the BRD4 short isoform in phase separation and active gene transcription. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabari, B.R.; Dall’Agnese, A.; Boija, A.; Klein, I.A.; Coffey, E.L.; Shrinivas, K.; Abraham, B.J.; Hannett, N.M.; Zamudio, A.V.; Manteiga, J.C.; et al. Coactivator condensation at super-enhancers links phase separation and gene control. Science 2018, 361, eaar3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Han, T.W.; Xie, S.; Shi, K.; Du, X.; Wu, L.C.; Mirzaei, H.; Goldsmith, E.J.; Longgood, J.; Pei, J.; et al. Cell-free Formation of RNA Granules: Low Complexity Sequence Domains Form Dynamic Fibers within Hydrogels. 2012, 149, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, L.; Foley, A.C.; Vaux, D.J.T. The Physiological and Pathological Implications of the Formation of Hydrogels, with a Specific Focus on Amyloid Polypeptides. Biomolecules 2017, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E., et al., Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy Server, in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook, J.M. Walker, Editor. 2005, Humana Press: Totowa, NJ. p. 571-607.

- Gully, B.S.; Cowieson, N.; Stanley, W.A.; Shearston, K.; Small, I.D.; Barkan, A.; Bond, C.S. The solution structure of the pentatricopeptide repeat protein PPR10 upon binding atpH RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 1918–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, N.M.; Mudie, S.T.; Hawley, A.M.; Cookson, D.J.; Mertens, H.D.T.; Cowieson, N.; Samardzic-Boban, V. A low-background-intensity focusing small-angle X-ray scattering undulator beamline. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2013, 46, 1670–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- http://archive.synchrotron.org.au/aussyncbeamlines/saxswaxs/software-saxswaxs, S. http://archive.synchrotron.org.au/aussyncbeamlines/saxswaxs/software-saxswaxs, S.

- Petoukhov, M.V., et al., New developments in the ATSAS program package for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Crystallogr, 2012. 45(Pt 2): p. 342-350.

- Tria, G.; Mertens, H.D.T.; Kachala, M.; Svergun, D.I. Advanced ensemble modelling of flexible macromolecules using X-ray solution scattering. IUCrJ 2015, 2, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.sasview.org/, S. https://www.sasview.org/, S.

- Konarev, P.V.; Volkov, V.V.; Sokolova, A.V.; Koch, M.H.J.; Svergun, D.I. PRIMUS: A Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 1277–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenyuk, A.V.; Svergun, D.I. GNOM – a program package for small-angle scattering data processing. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1991, 24, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Peng, L.; Baldwin, P.R.; Mann, D.S.; Jiang, W.; Rees, I.; Ludtke, S.J. EMAN2: An extensible image processing suite for electron microscopy. J. Struct. Biol. 2007, 157, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Peak 1 | Peak 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elution volume (ml) | Measured MW (kDa) | MW distribution (kDa) |

Stoichiometry | Elution volume (ml) | Measured MW (kDa) | MW distribution (kDa) |

Stoichiometry | |

| hnRNPK at 4oC | 12.4 | 101.3 | 49.0-152.9 | 1.98:1 | 14.0 | 59.1 | 54.0-73.0 | 1.16:1 |

| hnRNPK at RT | 12.5 | 146.9 | 114.8-282.4 | 2.88:1 | 13.6 | 78.0 | 51.0-138.0 | 1.53:1 |

| Sample | hnRNPK at 25o C | hnRNPK at 4o C | Hydrogenated hnRNPK monomer |

Hydrogenated hnRNPK aggregate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Collection Parameters | ||||

| Instrument | Australian Synchrotron SAXS/WAXS beamline | QUOKKA, SANS beamline, ANSTO | ||

| q range (Å-1) | 0.0031-0.0751 | 0.0080-0.4800 | 0.0060-0.42 | 0.0060-0.0824 |

| Concentration (mg/ml) | 0.82 | 6.20 | 1.1 (unmatched); 26.6 (total) |

28.9 (unmatched) |

| Sample temperature (oC) |

22o C |

4oC |

20o C |

20o C |

| Structural Parameters | ||||

| I(0), cm-1, from Guinier | 0.1036±0.001000 | 0.0062±0.000075 | 0.0692 ± 0.001500 | 34.1000 ± 0.000880 |

| Rg, Å, from Guinier | 106.0±1.40 | 39.4±2.96 | 28.8 ± 0.90 | 88.48 ± 0.01 |

| I(0), cm-1, from P(r) | 0.109300±0.0010280 | 0.006347±0.0002068 | 0.074000 ± 0.0011000 | 34.120000 ± 0.0008103 |

| Rg, Å, from P(r) |

113.9±1.710000 |

44.0±2.695000 |

32.9 ± 0.600000 |

88.71 ±0.004509 |

| Dmax, nm | 42.5 | 18.7 | 11.2 | 28.6 |

| P(r) Quality estimate |

0.6733 |

0.6411 |

0.5840 |

0.6500 |

| Molecular Mass Estimation by Bayesian Probability | ||||

| Estimated Molecular mass, Mr(kDa) | 873.1 | 54.4 |

67.5 |

1267.9 |

| MW Probability, % | 32.6 | 21.5 | ||

| Credibility Interval (kDa) | 614.5, 1013.1 | 46.2, 63.1 | ||

| Credibility Interval Probability, % | 93.2 | 93.1 | ||

| Calculated Mrfrom sequence (kDa) † | 51.0 | 51.0 | ||

| Estimated Ratio/state† |

Aggregate |

Monomer |

Monomer |

Aggregate |

| DAMMIF (default parameters, 20 calculations) | ||||

| Symmetry, anisotropy assumptions | P1, none | P1, none | P1, none |

P1, none |

| χ2 | 0.2892 | 0.2594 | 0.6888 | 1454 |

| NSD (standard deviation) |

1.094 (0.078) |

0.651 (0.037) |

0.893 (0.048) |

0.708 (0.056) |

| Resolution (from SASRES) (Å) |

97 ± 7 |

39 ± 3 |

40 ± 3 |

85 ± 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).