Submitted:

29 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Samples

2.2. Serological and Molecular Analysis

2.3. Next Generation Sequencing

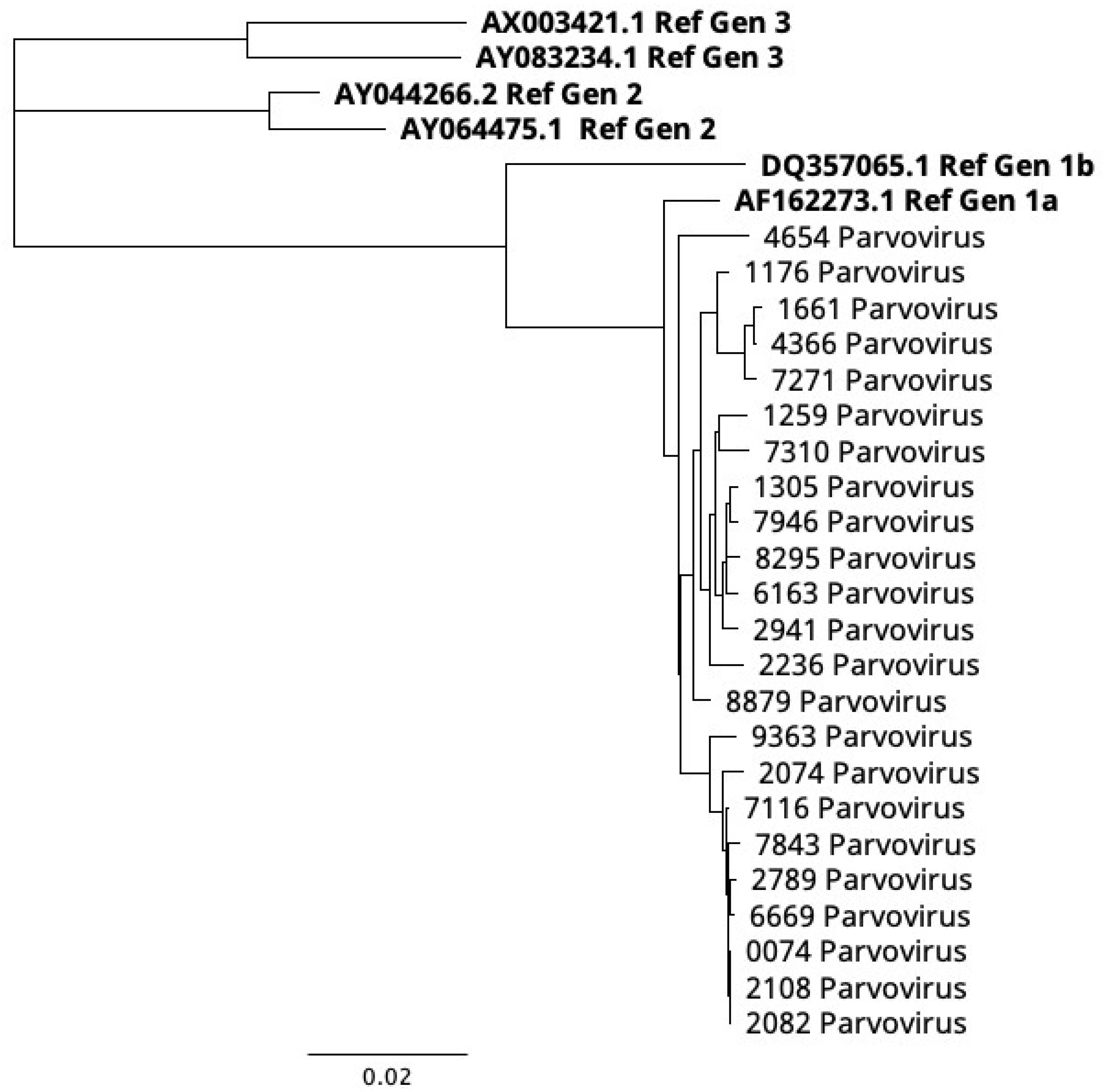

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

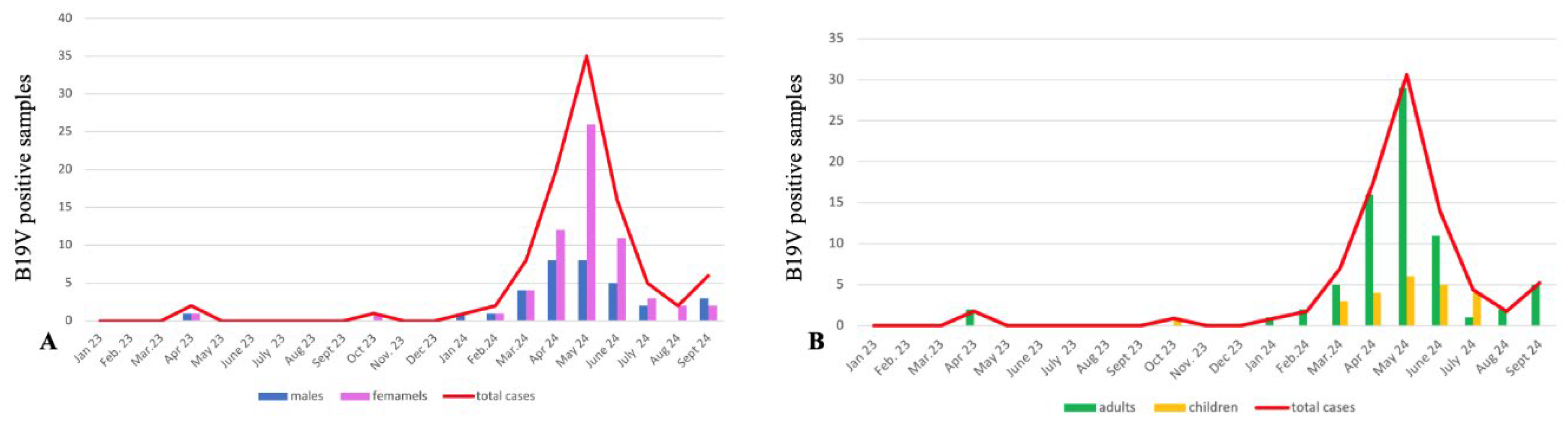

3. Results and Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Servey, J.T.; Brian V Reamy B., V.; Hodge, J. Clinical presentations of parvovirus B19 infection. Am Fam Physician. 20007, 75, 373–376. [Google Scholar]

- Badrinath, A.; Gardere, A.; Samantha, L. Palermo S.L.; Campbell K.S.; and Kloc A. Analysis of Parvovirus B19 persistence and reactivation in human heart layers. Front. Virol. 2024, 4, 1304779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, T. , von Landenberg P.; Modrow S. Parvovirus B19 and Autoimmunity: A Review of Current Findings in Adult Infections. Autoimmun Rev. 2003, 2, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmer, F.P.; De Moura Guimarães, C.; Alberto Borges Peixoto, A.; Monezi Pontes, K.F.; Bonasoni, M.P.; Tonni, G.; Araujo, E. Júnior. Parvovirus B19 Infection and Pregnancy: Review of the Current Knowledge. Journal of Personalized Medicine,.

- De Cnc Garcia, R.; Leon, L.A. Human Parvovirus B19: A Review of Clinical and Epidemiologial Aspects in Brazil. Future Microbiology 2021, 16, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallinella, G. Parvoviridae. In Encyclopedia of Infection and Immunity; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, M.; Weidner, A. & Enders, G. Current epidemiological aspects of human parvovirus B19 infection during pregnancy and childhood in the western part of Germany. Epidemiol. Infect, 2007, 135, 563–569. [Google Scholar]

- Vyse, A. J.; Andrews, N. J.; Hesketh, L. M. & Pebody, R. The burden of parvovirus B19 infection in women of childbearing age in England and Wales. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007, 135, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar]

- d’Humières, C.; Fouillet, A.; Verdurme, L. ; Lakoussan S-B.; Gallien Y.; Coignard C.; Hervo M.; Ebel A.; Visseaux B.; Maire B.; et al. An unusual outbreak of parvovirus B19 infections, France, 2023 to 2024. Euro Surveill. 2400, 29, pii=2400339. [Google Scholar]

- Ganaie Safder, S. , Qiu J. Recent Advances in Replication and Infection of Human Parvovirus B19. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2018, 8, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Yong Luo, Y.; Jianming Qiu, J. Human parvovirus B19: a mechanistic overview of infection and DNA replication. Future Virol. 2015, 10, 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Servant, A.; Laperche S,; Lallemand F. ; Marinho V.; De Saint Maur G.; J.F.; Garbarg-Chenon A. Genetic diversity within human erythroviruses: identification of three genotypes. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 9124–9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübschen, J.M.; Mihneva, Z.; Mentis, A.F.; Schneider, F.; AboudyY. ; Grossman Z.; Rudich H. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of human parvovirus B19 sequences from eleven different countries confirms the predominance of genotype 1 and suggests the spread of genotype 3b. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3735–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallinella, G.; Venturoli, S.; Manaresi, E.; Musiani, M.; Zerbini, M. B19 virus genome diversity: Epidemiological and clinical correlations. J. Clin. Virol. 2003, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eis-Hübinger, A.M.; Reber, U.; Edelmann, A.; Kalus, U.; Hofmann, J. Parvovirus B19 genotype 2 in blood donations. Transfusion. 2014, 54, 54,1682–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russcher, A.; van Boven, M.; Benincà, E.; Verweij, E.J.T.; M. W.A.; Zaaijer H.L.; Vossen A. C. T. M.; Kroes A.C.M. Changing epidemiology of parvovirus B19 in the Netherlands since 1990, including its re-emergence after the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 9630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.P. , Walther, F.J., Kroes, A.C.M. and Oepkes, D. Parvovirus B19 infection in pregnancy: new insights and management. Prenat. Diagn., 2011, 31, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Kant, R. Genotypes of erythrovirus B19, their geographical distribution & circulation in cases with various clinical manifestations. Indian J. Med. Res. 2018, 147, 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Karlin, D.G. Parvovirus B19 and Human Parvovirus 4 Encode Similar Proteins in a Reading Frame Overlapping the VP1 Capsid Gene. Viruses 2024, 16, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikawa, T.; Anderson, S.; Momoeda, M.; Kajigaya, S.; Young, N.S. Neutralizing linear epitopes of B19 parvovirus cluster in the VP1 unique and VP1-VP2 junction regions. J. Virol, 1993, 67, 3004–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Momoeda, M.; Kawase, M.; Kajigaya, S.; Young, N.S. Peptides derived from the unique region of B19 parvovirus minor capsid protein elicit neutralizing antibodies in rabbits. Virology 1995, 206, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzman, G.J.; Cohen, B.J.; Field, A.M.; Oseas, R.; Blaese, R.M.; Young, N.S. Immune response to B19 parvovirus and an antibody defect in persistent viral infection. J. Clin. Investig. 1989, 84, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzman, G.J.; Cohen, B.J.; Field, A.M.; Oseas, R.; Blaese, R.M.; Young, N.S. Immune response to B19 parvovirus and an antibody defect in persistent viral infection. J. Clin. Investig. 1989, 84, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtzman, G.; Frickhofen, N.; Kimball, J.; Jenkins, D.W.; Nienhuis, A.W.; Young, N.S. Pure Red-Cell Aplasia of 10 Years’ Duration Due to Persistent Parvovirus B19 Infection and Its Cure with Immunoglobulin Therapy. New Engl. J. Med. 1989, 321, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamenković, G.G; Ćirković, V.S.; Šiljić, M.M.; Blagojević, J.V.; Aleksandra, M. Knežević A.M.; Joksić I.D. & Stanojević M.P. Substitution rate and natural selection in parvovirus B19. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Haoran, J.; Qi, Q.; Yangzi, Z.; Yan, Z.; Wenbo X; Cui, Aili; XiaomeL. The epidemiological and genetic characteristics of human parvovirus B19 in patients with febrile rash illnesses in China. Sci. Reports, 2023, 13, 15913. [Google Scholar]

| Gene | Mutations |

|---|---|

| NS1 | 803G>A; 1175 C>T; 1227 A>T, 1430 A>T; 1140 C>T; 1529A>G; 1928 A>C; 2286 T>C |

| VP1/VP2 | 2754 C>T; 3351T>G; 3444 T>A; 3489 C>T; 3531 A>C; 3752 C>G; 3795 A>G; 3894 C>T; 4264C>T; 43069A>T; 4345 T>C; 4346 C>A. |

| Gene | Mutation | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| NS1 | C17S | 9/23 |

| NS1 | F57L | 4/23 |

| NS1 | V71A | 5/23 |

| NS1 | L111F | 6/23 |

| NS1 | F554S | 9/23 |

| VP1u | K14E | 7/23 |

| VP1 | V30L | 18/23 |

| VP1u | S98N | 17/23 |

| VP1/VP2 | A260T-A33T | 6/23 |

| VP1/VP2 | N533S-N306S | 17/23 |

| VP1/VP2 | G537A-G310A | 9/23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).