1. Introduction

Papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC) is one of the most frequently diagnosed forms of thyroid cancer. There has been an increasing trend in its incidence over the past decades. Over the period between 1990 and 2017, the global annual age-standardized incidence rate (ASIR) of thyroid cancer rose from 2.1 to 3.15; the annual increase was 1.59% [

1]. Advances in diagnostic procedures and higher frequency of using fine-needle aspiration biopsy are among the key reasons behind the increasing number of diagnosed cases. The modern imaging techniques and diagnostic approaches allow one to detect even minute lesions in the thyroid gland, thus resulting in larger number of diagnosed PTMC cases [

2].

Specialists often perform fine-needle aspiration biopsy of even small thyroid lesions, although clinical guidelines do not always find it necessary [

3]. Nevertheless, physicians perform a biopsy at the slightest suspicion of malignancy, which in turn increases the number of detected PTMC cases. Physicians often rely on the results of fine-needle aspiration biopsy when making a decision whether a surgical intervention is needed, so the number of surgeries of the thyroid rises [

4]. Controversy exists among specialists about this approach, since many of detected microcarcinomas remain stable and do not progress over a long time [

2]. The strategy of active surveillance (AS) for PTMC is currently becoming more popular in the global medical community [

5].

Studies demonstrated that only 5% of all papillary microcarcinomas progress and require active interventions [

6]. However, even this small percentage is rather significant, since tumor progression can jeopardize patient health. Therefore, the AS strategy requires tight control and regular examination to timely detect any potential changes in tumor condition and take respective measures. There currently exist certain criteria for active surveillance of patients: tumors < 1 cm in diameter, located at a distance from the trachea, esophagus, and laryngeal nerves [

7].

Patient’s psychological readiness for active surveillance is also very important. The patient should be informed about the possible risks and benefits of this approach, as well as the need to undergo regular monitoring and examinations [

8].

Despite the significance of the aforementioned criteria for choosing a strategy for active surveillance of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma, one should admit that they are relative and subjective. Each case of papillary thyroid microcarcinoma is unique, and its progression can be affected by numerous factors [

9].

The pivotal criterion for choosing the active surveillance strategy is the absence of any signs of lymphogenic or distant metastases. If metastases emerge during AS, more aggressive treatment (thyroidectomy and lymphadenectomy; radioiodine therapy) is required than therapy that could have been used for a newly diagnosed microcarcinoma when hemithyroidectomy is usually a sufficient option [

4]. Searching for new markers that can predict the aggressiveness of PTMC as early as at the preoperative stage remains an urgent problem that still needs to be solved. Attempts to predict the aggressiveness of papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) based on molecular genetic alterations have been made in various studies [

10,

11,

12], and molecular risk groups (MRGs) were formed. In particular, the low-risk MRG involved RAS-like alterations, and the intermediate-risk MRG involved BRAF alterations. The high-risk profile included the presence of mutations in the TERT, TP53, AKT1, and PIK3CA genes. Studies have shown that the molecular profile can rather accurately predict the risk of distant metastases based on the presence of TERT, TP53, AKT1 and PIK3CA mutations [

13,

14] and generally improve the accuracy of estimating the risk of recurrence according to the ATA guidelines [

15]. However, it was impossible to predict the emergence of metastases in the cervical lymph nodes based on the data on mutations.

The revealed associations between the presence of regional metastases in patients with PTC and the microRNA + mRNA expression levels in tumor tissue are of particular interest. However, the chances for detecting these molecular genetic alterations in FNAB specimens have not been assessed in these studies [

16,

17,

18,

19].

In our previous paper, we investigated the diagnostic potential of several types of molecular markers, such as expression of various miRNAs and protein-coding genes, for preoperatively predicting such characteristics of PTC as lymphogenic metastasis and extrathyroidal invasion. The results of these studies have already been published [

20]. In the present work, we assessed the diagnostic accuracy of molecular genetic markers in predicting the metastatic potential in patients with PTMC.

2. Materials and Methods

Over the period between 2021 and 2023, 92 patients were chosen from 1804 patients diagnosed with PTMC on a random basis; 32 of them had metastases to regional cervical lymph nodes. The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of the South Ural State Medical University dated 18 April 2019 (protocol No. 3).

Choosing a set of molecular markers. The set of mRNAs for analysis was primarily selected according to the available literature. Protein-coding genes were chosen so that their exon–intron structure enabled detection of mRNA without preliminary removal of genomic DNA. The list of mRNAs included 22 genes: FN1, Geminin (GMNN), CDKN2A, TIMP1, CITED1, TPO, SLC26A7, HMGA2, CPQ, RXRG, SPATA18, APOE, ASF1B, AFAP1L2, CLU, ECM1, DIO1, NIS, SERPINA1, TFF3, TMPRSS4, and TSHR.

The microRNA set was chosen based on our own data [

21], as well as analysis of literature data. A total of 11 microRNAs were included in experimental analysis: miR-146b-5p, miR-199b-5p, miR-221-3p, miR-223-3p, miR-31-5p, miR-375, miR-451a, miR-551b-3p, miR-148b-3p, miR-21-5p, and miR-125b-5p. Hence, a total of 33 molecular genetic markers were studied in this work. The presence of the somatic BRAF V600E mutation was investigated separately.

Semi-quantitative assessment of messenger RNA level. Semi-quantitative assessment of mRNA level was conducted by real-time RT-PCR using specific primers and fluorescent-labeled probes to detect mRNAs of respective genes and the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK1) housekeeping gene, which was used as a normalization gene. The RT-PCR protocol was as follows: incubation at 45 °C for 30 min; heating at 95 °C for 2 min, 50 cycles: denaturation at 94 °C for 10 s, annealing and elongation at 60 °C for 20 s. The relative expression level was calculated using the 2

−ΔCq method [

22].

Detection of microRNAs. Real-time RT-PCR detection of 16 miRNAs was conducted for all the types of tumors and lesions. Mature miRNAs were detected by stem-loop RT-PCR [

23]. Real-time reverse-transcription PCR was conducted according to the procedure described in ref. [

21]. Reverse transcription reaction followed by real-time PCR was carried out individually for each miRNA. A single replicate of analysis was performed for each sample. The miRNA level was normalized to the geometric mean of the levels of three reference miRNAs (miR-197-3p, -23a-3p, and -29b-3p) using the 2-ΔCq method.

Detection of somatic BRAF mutation. All the samples were analyzed to detect somatic mutations: V600E, V600K, and V600R in the BRAF gene. Somatic mutations were detected by allele-specific PCR with a hydrolyzable probe. The PCR protocol was as follows: pre-heating at 95 °C for 2 min, 50 cycles: denaturation at 94 °C for 10 s; annealing and elongation at 60 °C for 15 s.

Statistical data analysis was conducted using the SPSS Statistics 23 (IBM, USA) and Excel software (Microsoft, USA). The data are presented as the mean and median values, as well as the first (Q1) and third (Q3) quartiles. Comparative analysis of two independent groups for quantitative traits was performed using the Mann–Whitney U test. Comparative analysis of two independent groups for quantitative traits was conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test. The multiple hypothesis testing problem was solved using the family-wise error rate (FWER) with Bonferroni correction. The significance level p was calculated as 0.05 divided by the number of features being compared; 33 features were compared in our study. Therefore, differences at significance level p <0.05/33 = 0.0015 were considered statistically significant. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to assess associations between two binary characteristics.

ROC analysis was conducted to objectively assess the predictive power of expression levels of various microRNAs and genes and predict the risk of detecting lymphogenic metastases of PTMC. The operating characteristics of the following parameters were calculated: sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPC), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV). Test comparison was carried out with allowance for the area under the ROC curves (AUC). The expert scale used to assess model performance was as follows: 0.9–1.0—excellent; 0.8–0.9—very good; 0.7–0.8—good; 0.6–0.7—fair; and 0.5–0.6—unsatisfactory.

Machine learning algorithms were used to build classification models: logistic regression analysis (LR) and light gradient-boosting machine (LightGBM). The models were built using the data development and machine learning software packages (Numpy v1.24.3, Pandas v2.0.3, Scikit-learn v1.3.0, and LightGBM v4.3.0) for Python programming language (v3.11.5). The data were randomly divided into the training and test samples (at a ratio of 0.8:0.2 from the original sample), with interclass correlations left unchanged. Values in the training and test samples were normalized. Hyperparameters were selected using the grid search procedure and fivefold cross-validation. Accuracy (prognostic accuracy), Precision (correctness of positive predictions), Recall (completeness of prognosis), F1 score (the harmonic mean of the Precision and Recall metrics), ROC AUC score (area under the ROC curve), and Specificity were used as prognostic performance metrics. The Recall metric, corresponding to classifier sensitivity, was chosen to be the target metric for training. The results of comparison using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Mutual Information function (a nonparametric test indicating the relationship between two random variables, which is used in machine learning for feature selection) were used for feature selection.

3. Results

Females predominated (81.5%) among the 92 patients included in the study; the percentage of males was 18.5% of the total number of patients. The mean age of patients at surgery was 47 years (range: 18–76 years). PTMC was most frequently located in the right thyroid lobe (70%) and less frequently, in the left thyroid lobe (30%). In accordance with the standardized European Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System (EU-TIRADS), six (6.5%) patients had EU-TIRADS category 3; 19 (20.7%) patients, EU-TIRADS category 4; and 67 (72.8%) patients, EU-TIRADS category 5. According to the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (TBSRTC, 2023), the analyzed group of patients was distributed as follows: Atypia of Undetermined Significance (AUS), in 2 (2.2%) patients; Follicular neoplasm (FN), in 13 (14.1%) patients; Suspicious for Malignancy (SM), in 43 (46.7%) patients; and Malignant (M), in 34 (37%) patients. Hemithyroidectomy was conducted in 60 (65.2%) cases; thyroidectomy, in 32 (34.8%) cases; of those, the intervention involved central lymphadenectomy in 27 patients; central and lateral lymphadenectomy, in 5 patients. Metastases verified by ultrasound imaging or thyroglobulin measurement in FNAB washout fluid at the preoperative stage was an indication for lymphadenectomy (prophylactic lymphadenectomy was not performed). The mean tumor nodule size was 7 mm (the minimal size, 4 mm; the maximal size, 9 mm).

Statistically significant differences were detected for 11 out of 33 analyzed molecular genetic markers: microRNAs miR-146b, miR-7, and miR-148b; messenger RNAs FN1, TIMP1, TPO, SLC26A7, HMGA2, DIO1, TFF3, and the BRAF mutation (

Table 1).

In patients with metastatic PTMC, the HMGA2 gene (transcriptional regulation factor), the TIMP1 gene (matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor), and the FN1 gene (fibronectin) were more active, and microRNA-146b expression was upregulated. Downregulated expression of microNRA-7 and -148b was also detected in metastatic tumors, which is indicative of their tumor suppressor role. Metastatic tumors were characterized by on average 11-fold lower activity of iodothyronine deiodinase (DIO1), eightfold lower expression of the TFF3 gene, fourfold lower expression of the thyroid peroxidase (TPO) gene, and 2.6-fold lower expression of the SLC26A7 (the sulfate anion transporter) gene.

With allowance for multiple hypothesis testing with Bonferroni correction, the significance level p of 0.05/33 = 0.0015 was achieved only for miR-146b (p = 0.013).

The BRAFV600E mutation was detected in 24 out of 32 patients with metastases and 34 out of 60 patients without metastases. The odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was 4.6 (1.8–11.9), p = 0.0016.

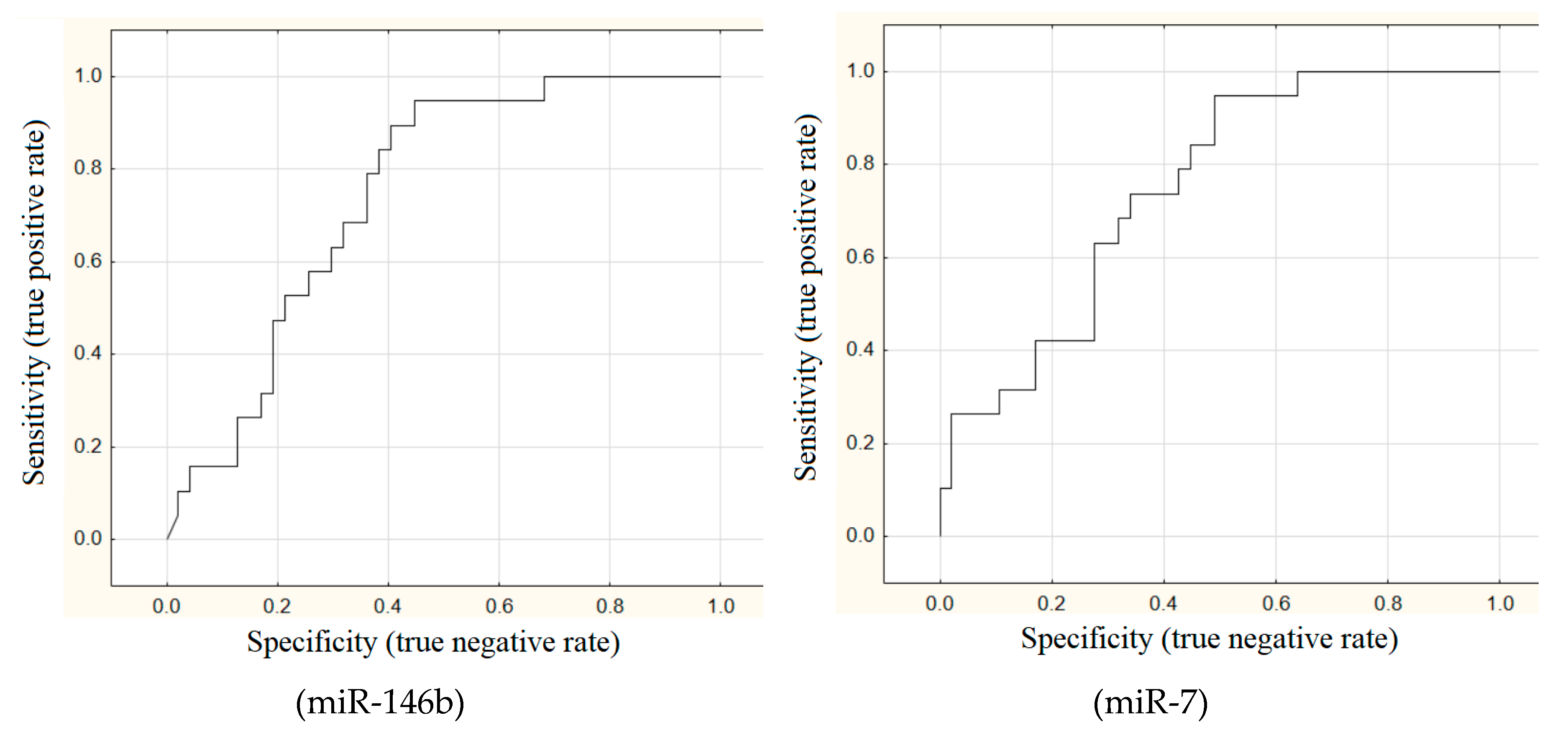

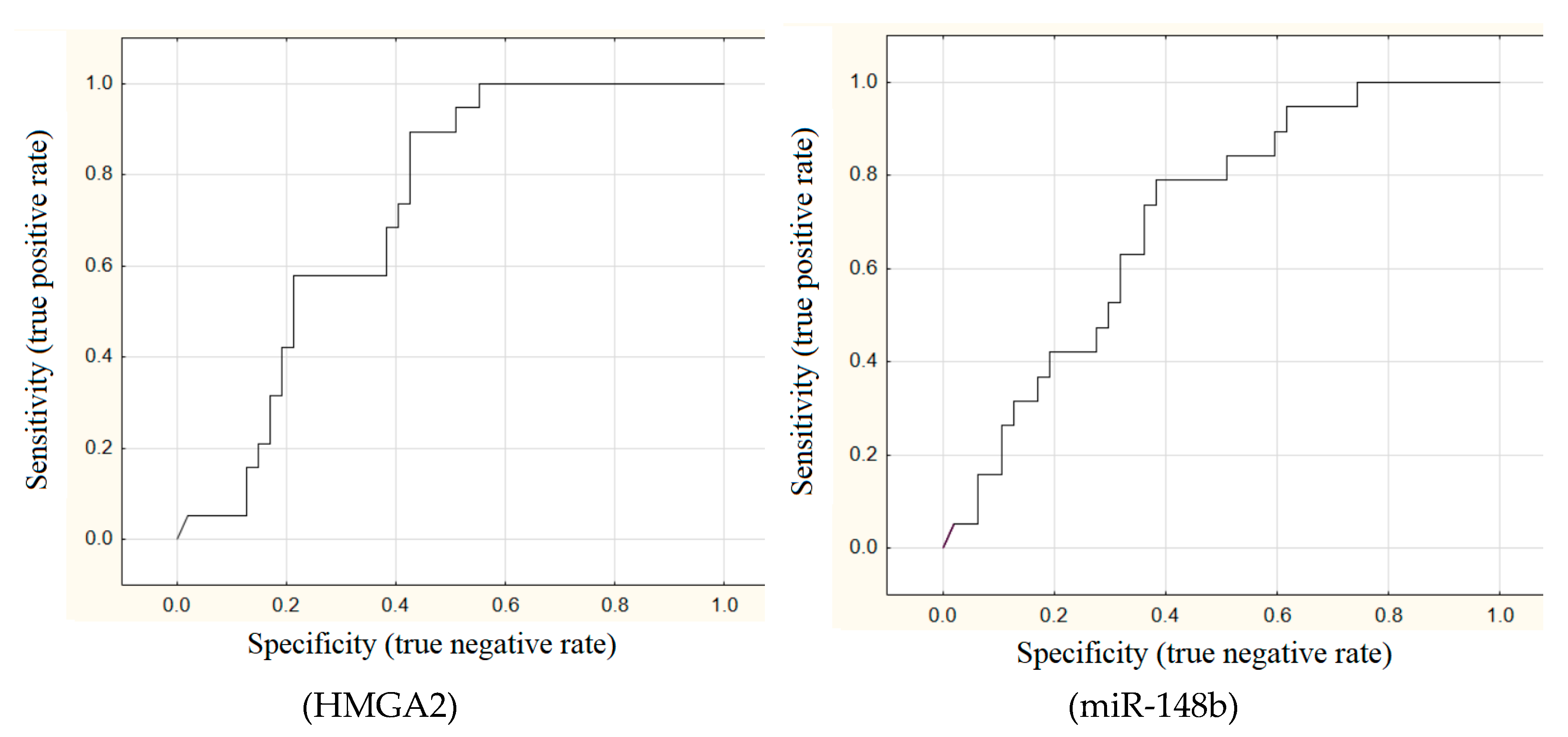

The areas under ROC curves (AUC) were calculated for all these 11 markers. Good outcomes (AUC > 0.7) were achieved for miR-146b (AUC = 0.75), miR-7 (AUC = 0.75), HMGA2 (AUC = 0.72), and miR-148b (AUC = 0.7) (

Figure 1).

The diagnostic capability was assessed for each of these four markers and the BRAF mutation (

Table 2). Detected BRAFV600E mutation, miR-146b expression level ≥ 5.4, miR-7 expression level ≤ 0.13, HGMA2 expression level ≥ 0.17, and miR-148b expression level ≤ 0.67 were regarded as diagnostic factors of metastatic PTMC.

All the markers, except for BRAF mutation, have high sensitivity for detecting metastatic PTMC but low specificity (~50%). In other words, expression levels of microRNA and mRNA were typical of metastatic carcinoma in almost every other patient without metastases.

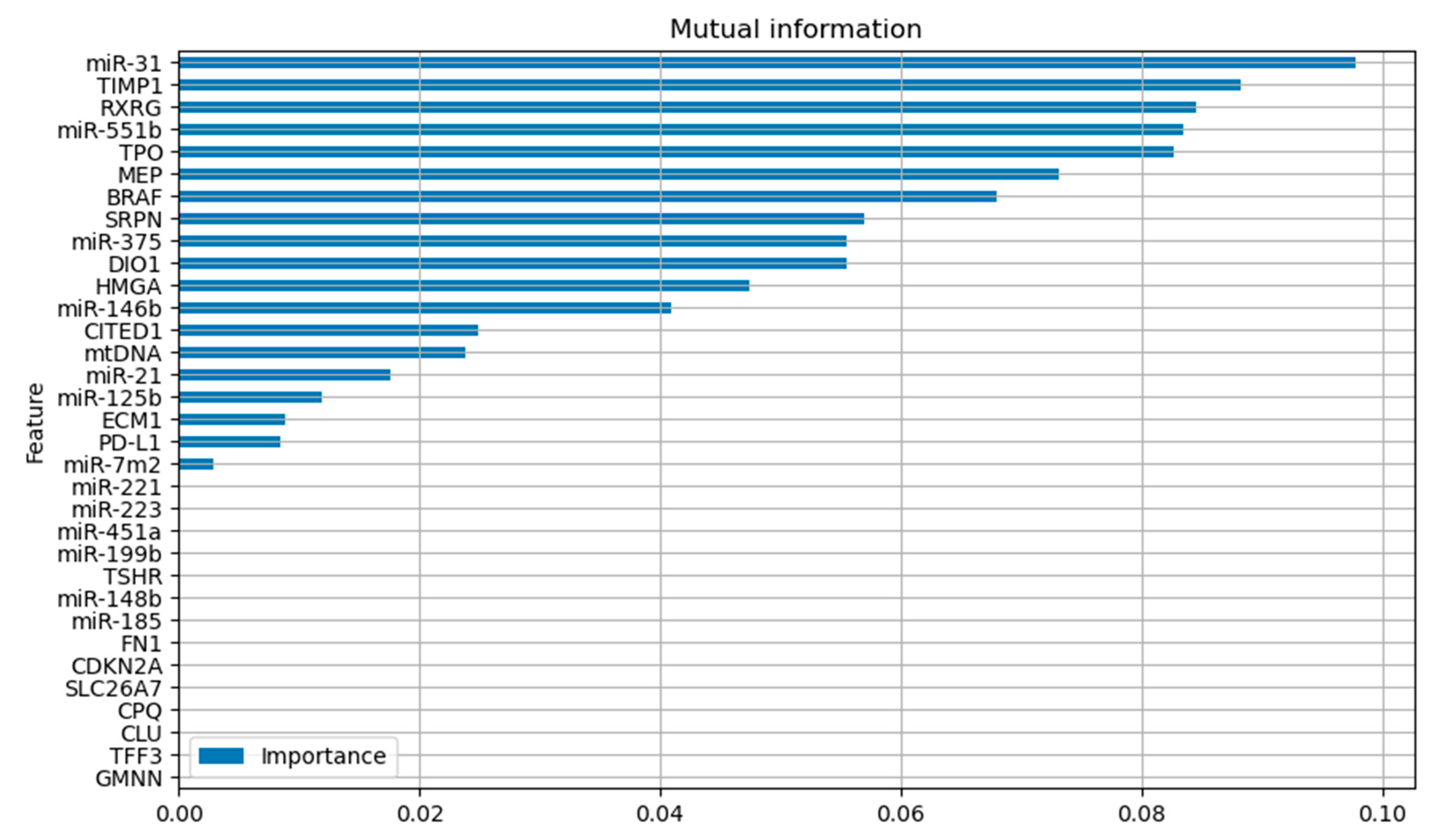

Different machine learning algorithms were used to build prognostic models. Training involved two stages. At the first stage, feature selection procedure was employed using the Mutual Information function implemented in sklearn for the training dataset (

Figure 2). Features with the Mutual Information value of zero were excluded from further analysis.

At the second stage, classification models were built using the selected features (

Table 3). The models were also built for the features selected using the Mann–Whitney U test according to statistical significance (

Table 4).

The LGBoost model built based on the features selected using the Mutual Information function had the most robust prediction results in the training and test datasets (up to 71% sensitivity and 66% specificity for the test sample).

4. Discussion

The ATA recurrence risk stratification system assesses the likelihood of PTMC persistence to be low. Unifocal papillary microcarcinomas located inside the thyroid gland and having no aggressive histological signs are believed to be characterized by recurrence risk of <1% [

5]. According to the same guidelines, the recurrence risk is associated with the presence of cervical lymph node metastases. When assessing the recurrence risk, one should take into account the number and size of metastases, the number of affected lymph nodes with extracapsular invasion and their localization (the central or lateral cervical region). Therefore, it is possible to identify the histological variant and the stage of the neoplastic process depending on existing capsular invasion, multifocality and cervical lymph node metastases only after the final histological examination is performed. It is the major problem faced by advocates for active surveillance for PTMC.

The largest observational study of active surveillance in patients with PTMC was conducted at the Kuma Clinic upon suggestion of Akira Miyauchi [

6]. The authors of the study followed up 3222 patients with microcarcinomas and compared the data to the outcomes of surgical treatment in 2424 patients. The rate of metastatic spread to cervical lymph nodes within the 20-year follow-up was statistically significantly higher in the AS group (1.7% vs. 0.7% in the group of operated patients). Nevertheless, the authors inferred that the likelihood of metastatic spread is low, and active surveillance is justified. Researchers mentioned that young age (<30 years), male sex, and tumor size ≥6 mm are factors increasing the risk of metastatic spread [

6,

24].

The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), in cooperation with Kuma Hospital group, has elaborated the clinical scheme to assess whether active surveillance is suited for a certain patient [

7]. The “ideal” candidates are patients older than 60 years, with a tumor not adjoining the thyroid capsule. A “suitable” candidate should be younger and have a multifocal tumor with the potentially aggressive molecular phenotype (BRAF, TERT-positive; PDT-positive); the tumor can be adjoining the thyroid capsule but should not lie in the risk zones; it may also have other imaging features that may hamper further surveillance (e.g., thyroiditis or other benign thyroid nodules). An “ill-suited” candidate has tumors in risky locations (e.g., near the trachea or the recurrent laryngeal nerve) or has signs of extrathyroidal invasion. The authors of these recommendations indicate that many of these characteristics are rather relative and strongly depend on the expertise of the clinic and medical personnel. Experts agree that molecular genetic studies are the future of identifying indications for using the active surveillance approach; however, they are currently not available in routine practice, especially in developing countries [

25].

The presence of BRAF mutation is currently the best-studied and widely available molecular genetic marker. According to the large-scale meta-analysis data [

26], PTMC patients carrying a BRAFV600E mutation had a 43% higher risk of developing metastasis in cervical lymph nodes (OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.19–1.71). According to our data, the OR was 4.6 (CI = 1.8–11.9), which is probably related to the higher occurrence of this mutation (63%) in the study group. However, if we rely exclusively on this marker, 63% of PTMC patients a priori should not remain under active surveillance.

The potential role of microRNA-146b in oncogenesis of papillary thyroid cancer was reported in a meta-analysis back in 2017 [

27]. Its increased expression level was associated with the more aggressive course of the disease. According to our data, prediction of metastatic spread using this marker was more accurate than prediction based on BRAF mutation (87.5% sensitivity; 50% specificity). The other two microRNAs (miR-7 and miR-148b) and the HMGA2 gene showed a comparable accuracy. Nonetheless, the ~50% specificity implies that surgical treatment should be planned instead of active surveillance, whereas the total percentage of PTMC patients with lymphogenic metastases estimated by us was as low as 5.6% (102 out of 1804). We believe that each of these markers should not be decisive and can be viewed exclusively as a supplementary method in doubtful cases when a choice between active surveillance and surgical treatment needs to be made

Machine learning models assess the potential of analyzed markers for predicting metastatic spread in patients with PTMC. A combination of several markers improves prognostic performance. A promising approach is to combine the detected molecular parameters and clinical instrumented data to build more accurate models. Further data collection will significantly improve performance of the created models.

5. Conclusions

Application of molecular markers for predicting lymphogenic metastatic spread in patients with PTMC can possibly supplement the existing risk grading systems. These studies are relatively simple to conduct and available as early as at the preoperative stage. Machine learning algorithms provide more accurate outcomes than each individual marker. To create higher-accuracy models, experience needs to be gained and parameters being analyzed need to be expanded by using clinical instrumented data and larger patient samples.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.A.L., S.E.T. and V.E.V.; methodology: S.E.T., S.A.L. and A.V.D.; validation: S.A.L. and S.E.T.; formal analysis: S.A.L. and S.V.S.; investigation: S.E.T., S.A.L., A.V.D. and Y.A.V.; resources: S.A.L., E.V.B., E.A.T. and L.S.U.; data curation: S.A.L., S.E.T. and S.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation: S.E.T., S.A.L. and A.V.D.; writing—review and editing: S.V.S. and D.G.B.; supervision: S.V.S., V.E.V. and D.G.B.; project administration: S.A.L. and S.E.T.; funding acquisition: E.V.B. E.A.T. and L.S.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Grant Number: 075-15-2022-310). The study was supported by the Tomsk State University Development Program (Priority-2030). The study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 20-14-00074-P).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of the South Ural State Medical University dated April 18, 2019 (protocol No. 3).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study; all data were depersonalized.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

The cell analysis was carried out at the Multi-Access Center of Microscopic Research at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics SB RAS (supported by a government-funded project for the IC&G). The authors express their gratitude to the multi-access center Bioinformatics for the computational resources and their software, which was created within the framework of the government-funded project FWNR-2022-0020.

Conflicts of Interest

Sergei E. Titov is an employee of AO Vector-Best. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Deng Y, Li H, Wang M, Li N, Tian T, Wu Y, Xu P, Yang S, Zhai Z, Zhou L, Hao Q, Song D, Jin T, Lyu J, Dai Z. Global Burden of Thyroid Cancer From 1990 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Jun 1;3(6):e208759. [CrossRef]

- Sugitani I. Active surveillance of low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023 Jan;37(1):101630. [CrossRef]

- Jasim S, Dean DS, Gharib H. Fine-Needle Aspiration of the Thyroid Gland. 2023 Mar 23. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000–. PMID: 25905400.

- Bi J, Zhang H. A meta-analysis of total thyroidectomy and lobectomy outcomes in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 Dec 15;102(50):e36647. [CrossRef]

- Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, et al.2015 American thyroid association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American thyroid association guidelines task force on thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016 26 1–133. [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi A, Ito Y, Fujishima M, Miya A, Onoda N, Kihara M, Higashiyama T, Masuoka H, Kawano S, Sasaki T, Nishikawa M, Fukata S, Akamizu T, Ito M, Nishihara E, Hisakado M, Kosaka K, Hirokawa M, Hayashi T. Long-Term Outcomes of Active Surveillance and Immediate Surgery for Adult Patients with Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: 30-Year Experience. Thyroid. 2023 Jul;33(7):817-825. [CrossRef]

- Brito JP, Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Tuttle RM. A Clinical Framework to Facilitate Risk Stratification When Considering an Active Surveillance Alternative to Immediate Biopsy and Surgery in Papillary Microcarcinoma. Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26(1):144-9. [CrossRef]

- Kong SH, Ryu J, Kim MJ, Cho SW, Song YS, Yi KH, Park DJ, Hwangbo Y, Lee YJ, Lee KE, Kim SJ, Jeong WJ, Chung EJ, Hah JH, Choi JY, Ryu CH, Jung YS, Moon JH, Lee EK, Park YJ. Longitudinal Assessment of Quality of Life According to Treatment Options in Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma Patients: Active Surveillance or Immediate Surgery (Interim Analysis of MAeSTro). Thyroid. 2019 Aug;29(8):1089-1096. [CrossRef]

- Jin L, Zhou L, Wang JB, Tao L, Lu XX, Yan N, Chen QM, Cao LP, Xie L. Whether Detection of Gene Mutations Could Identify Low- or High-Risk Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma? Data from 393 Cases Using the Next-Generation Sequencing. Int J Endocrinol. 2024 Jan 16;2024:2470721. [CrossRef]

- Patel SG, Carty SE, McCoy KL, Ohori NP, LeBeau SO, Seethala RR, Nikiforova MN, Nikiforov YE, Yip L. Preoperative detection of RAS mutation may guide extent of thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2017 Jan;161(1):168-175. [CrossRef]

- Song YS, Lim JA, Choi H, Won JK, Moon JH, Cho SW, Lee KE, Park YJ, Yi KH, Park DJ, Seo JS. Prognostic effects of TERT promoter mutations are enhanced by coexistence with BRAF or RAS mutations and strengthen the risk prediction by the ATA or TNM staging system in differentiated thyroid cancer patients. Cancer. 2016 May 1;122(9):1370-9. [CrossRef]

- Yip L, Nikiforova MN, Yoo JY, McCoy KL, Stang MT, Armstrong MJ, Nicholson KJ, Ohori NP, Coyne C, Hodak SP, Ferris RL, LeBeau SO, Nikiforov YE, Carty SE. Tumor genotype determines phenotype and disease-related outcomes in thyroid cancer: a study of 1510 patients. Ann Surg. 2015 Sep;262(3):519-25; discussion 524-5. [CrossRef]

- Schumm MA, Shu ML, Hughes EG, Nikiforov YE, Nikiforova MN, Wald AI, Lechner MG, Tseng CH, Sajed DP, Wu JX, Yeh MW, Livhits MJ. Prognostic Value of Preoperative Molecular Testing and Implications for Initial Surgical Management in Thyroid Nodules Harboring Suspected (Bethesda V) or Known (Bethesda VI) Papillary Thyroid Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023 Aug 1;149(8):735-742. [CrossRef]

- Yip L, Gooding WE, Nikitski A, Wald AI, Carty SE, Karslioglu-French E, Seethala RR, Zandberg DP, Ferris RL, Nikiforova MN, Nikiforov YE. Risk assessment for distant metastasis in differentiated thyroid cancer using molecular profiling: A matched case-control study. Cancer. 2021 Jun 1;127(11):1779-1787. [CrossRef]

- Liu JB, Baugh KA, Ramonell KM, McCoy KL, Karslioglu-French E, Morariu EM, Ohori NP, Nikiforova MN, Nikiforov YE, Carty SE, Yip L. Molecular Testing Predicts Incomplete Response to Initial Therapy in Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma Without Lateral Neck or Distant Metastasis at Presentation: Retrospective Cohort Study. Thyroid. 2023 Jun;33(6):705-714. [CrossRef]

- Zafon C, Gil J, Pérez-González B, Jordà M. DNA methylation in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2019 Jul;26(7):R415-R439. [CrossRef]

- Rogucki M, Buczyńska A, Krętowski AJ, Popławska-Kita A. The Importance of miRNA in the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Papillary Thyroid Cancer. J Clin Med. 2021 Oct 15;10(20):4738. [CrossRef]

- Nieto HR, Thornton CEM, Brookes K, Nobre de Menezes A, Fletcher A, Alshahrani M, Kocbiyik M, Sharma N, Boelaert K, Cazier JB, Mehanna H, Smith VE, Read ML, McCabe CJ. Recurrence of Papillary Thyroid Cancer: A Systematic Appraisal of Risk Factors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Apr 19;107(5):1392-1406. [CrossRef]

- Wang M, Li R, Zou X, Wei T, Gong R, Zhu J, Li Z. A miRNA-clinicopathological nomogram for the prediction of central lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid carcinoma-analysis from TCGA database. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Aug 28;99(35):e21996. [CrossRef]

- Lukyanov SA, Titov SE, Kozorezova ES, Demenkov PS, Veryaskina YA, Korotovskii DV, Ilyina TE, Vorobyev SL, Zhivotov VA, Bondarev NS, Sleptsov IV, Sergiyko SV. Prediction of the Aggressive Clinical Course of Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma Based on Fine Needle Aspiration Biopsy Molecular Testing. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Jun 28;25(13):7090. [CrossRef]

- Titov SE, Ivanov MK, Karpinskaya EV, Tsivlikova EV, Shevchenko SP, Veryaskina YA, Akhmerova LG, Poloz TL, Klimova OA, Gulyaeva LF, Zhimulev IF, Kolesnikov NN. miRNA profiling, detection of BRAF V600E mutation and RET-PTC1 translocation in patients from Novosibirsk oblast (Russia) with different types of thyroid tumors. BMC Cancer. 2016 Mar 9;16:201. [CrossRef]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001 Dec;25(4):402-8. [CrossRef]

- Chen C, Ridzon DA, Broomer AJ, Zhou Z, Lee DH, Nguyen JT, Barbisin M, Xu NL, Mahuvakar VR, Andersen MR, Lao KQ, Livak KJ, Guegler KJ. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem-loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005 Nov 27;33(20):e179. [CrossRef]

- Lee EK, Moon JH, Hwangbo Y, Ryu CH, Cho SW, Choi JY, Chung EJ, Jeong WJ, Jung YS, Ryu J, Kim SJ, Kim MJ, Kim YK, Lee CY, Lee JY, Yu HW, Hah JH, Lee KE, Lee YJ, Park SK, Park DJ, Kim JH, Park YJ. Progression of Low-Risk Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma During Active Surveillance: Interim Analysis of a Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study of Active Surveillance on Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma in Korea. Thyroid. 2022 Nov;32(11):1328-1336. [CrossRef]

- Dimov R, Kostov G, Doykov M, Hristov B. PAPILLARY MICROCARCINOMA OF THE THYROID GLAND—DOES SIZE MATTER? Acta Endocrinol (Buchar). 2023 Apr-Jun;19(2):163-168. [CrossRef]

- Attia AS, Hussein M, Issa PP, Elnahla A, Farhoud A, Magazine BM, Youssef MR, Aboueisha M, Shama M, Toraih E, Kandil E. Association of BRAFV600E Mutation with the Aggressive Behavior of Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma: A Meta-Analysis of 33 Studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Dec 9;23(24):15626. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Xu H, Qi M, Yan S, Tian X. miRNA dysregulation and the risk of metastasis and invasion in papillary thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017 Mar 29;9(4):5473-5479. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).