1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis represents a significant global health challenge, affecting millions in diverse geographical regions, particularly in tropical and subtropical areas [

1,

2]. This parasitic disease, caused by various species of Leishmania and transmitted by sandflies, manifests itself in cutaneous [

3], mucocutaneous [

4], and visceral forms [

5], each presenting distinct clinical complexities and health burdens [

6]. Although often neglected within the broader scope of public health initiatives, leishmaniasis remains endemic in more than 90 countries, with an estimated 700,000 to 1 million new cases each year. Current control measures are limited by socioeconomic factors, challenges in vector control, and the lack of an effective vaccine, making the disease’s persistence a critical concern. Addressing the multidimensional aspects of leishmaniasis demands a coordinated global response, integrating scientific, medical, and socio-political strategies to reduce its impact on affected populations [

7].

Current treatments for leishmaniasis primarily rely on a limited array of drugs, including antimonials, amphotericin B, miltefosine, and paromomycin [

8]. These treatments, while effective, pose several challenges: many have significant toxicity, require prolonged administration, and often demand hospitalization, especially in cases requiring intravenous medication [

9,

10]. The efficacy of these drugs also varies by Leishmania species and geographical location, complicating treatment protocols. Furthermore, drug resistance is emerging in some regions, exacerbating treatment difficulties and underscoring the need for alternative therapies [

11]. For public health systems, particularly in endemic areas, the financial burden of leishmaniasis treatment is substantial. High drug costs, combined with the need for infrastructure to support safe administration and follow-up care, strain limited healthcare budgets, often redirecting resources from other critical areas. This economic strain highlights the urgent need for investment in the development of affordable, effective, and accessible therapies that can alleviate the financial and operational pressures on public health systems worldwide [

12].

Natural products are gaining attention as promising alternatives for developing effective and sustainable treatments for leishmaniasis, with the Amazon rainforest recognized as a rich reservoir of biologically active species [

13]. This extensive biodiversity encompasses a variety of aromatic plants, which produce essential oils with well-established antimicrobial and antiparasitic properties [

14]. Natural products (NP) from Amazon rainforest species, particularly essential oils (EO) that are abundant in terpenoids, phenolic compounds, and other bioactive molecules, represent an innovative approach for the formulation of anti-leishmanial therapies [

15,

16,

17]. Recent research has focused on incorporating of EO into nanotechnological delivery systems, such as nanoparticles and liposomes, to enhance their therapeutic efficacy [

18,

19]. By encapsulating bioactive compounds in nanoscale carriers, these advanced formulations can improve drug stability, target specificity, and bioavailability, while reducing toxicity [

20]. Utilizing Amazon rainforest EO in nanotechnology-driven treatment strategies not only holds promise for more effective and accessible leishmaniasis therapies but also supports the sustainable use of rainforest resources, bridging biodiversity conservation with innovation in global health [

21].

Among these formulations, nanogels represent an innovative and highly effective approach for treating cutaneous lesions caused by cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Nanogels stand out due to their unique characteristics, such as high loading capacity and controlled release of active compounds, which make them ideal carriers for EO. These oils are particularly valued for their potent anti-inflammatory properties, alongside their antimicrobial and wound-healing effects. By promoting the reduction of inflammation, EO can help accelerate the healing process of lesions while simultaneously reducing local parasitic burden. Furthermore, the topical application of nanogels enables targeted, sustained delivery of the active compounds, ensuring enhanced therapeutic efficacy at the infection site and minimizing potential systemic side effects [

22,

23].

Nanogels have emerged as a promising platform for the controlled release of EO, offering significant potential for advancing wound healing and infection prevention [

24,

25,

26]. Incorporating EO into nanogel formulations enhances their antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and regenerative properties, making them highly effective for skin repair [

27]. Nanogels, characterized by their high loading capacity and controlled release mechanisms, offer sustained therapeutic effects directly at the wound site, aiding in tissue recovery and reducing the risk of infection [

28]. By incorporating essential oils, these systems further enhance localized efficacy through targeted delivery while simultaneously minimizing systemic side effects [

29]. Despite the promise demonstrated by nanogels as therapeutic platforms for delivering essential oils, particularly in antimicrobial and wound care applications, the number of published studies specifically focusing on EO-loaded nanogels with leishmanicidal and anti-inflammatory activities remains limited [

30]. While essential oil-loaded nanogels show considerable potential for localized and controlled drug delivery, their application in the treatment of leishmaniasis has yet to be fully explored. Further research is needed to optimize these formulations and to comprehensively evaluate their therapeutic efficacy, particularly for targeting both the parasite and the inflammatory processes associated with the CL. This gap highlights a critical opportunity for advancing EO-based nanogel systems as innovative and multifunctional tools for managing complex infectious diseases like leishmaniasis.

This study aims to broaden the antimicrobial applications of

Pectis brevipedunculata (Asteraceae) essential oil (EO

Pb) loaded F127/974P nanogel formulations. The genus

Pectis, part of the Asteraceae family, includes

Pectis brevipedunculata, a plant found in tropical and subtropical regions of the Americas, particularly in Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay [

31]. Known for its therapeutic properties, including anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial effects,

P. brevipedunculata has been used traditionally for various health benefits. Its essential oils, rich in monoterpenes such as neral, geranial, a-pinene, and limonene, exhibit strong antimicrobial activity, making the plant a promising candidate for developing natural antimicrobial agents and sustainable therapeutic applications [

32,

33]. In a prior investigation by our research group demonstrated promising larvicidal activity of EO

Pb-loaded nanogel against

Aedes aegyptilarvae, achieving effective inactivation without cytotoxic effects when tested with the unloaded nanogel [

34]. Based on these findings, the current work evaluates the

in vitro activity of the nanogel against promastigote forms of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis (

LLa), along with its

in vivo anti-inflammatory potential using the carrageenan-induced model of rat paw edema.

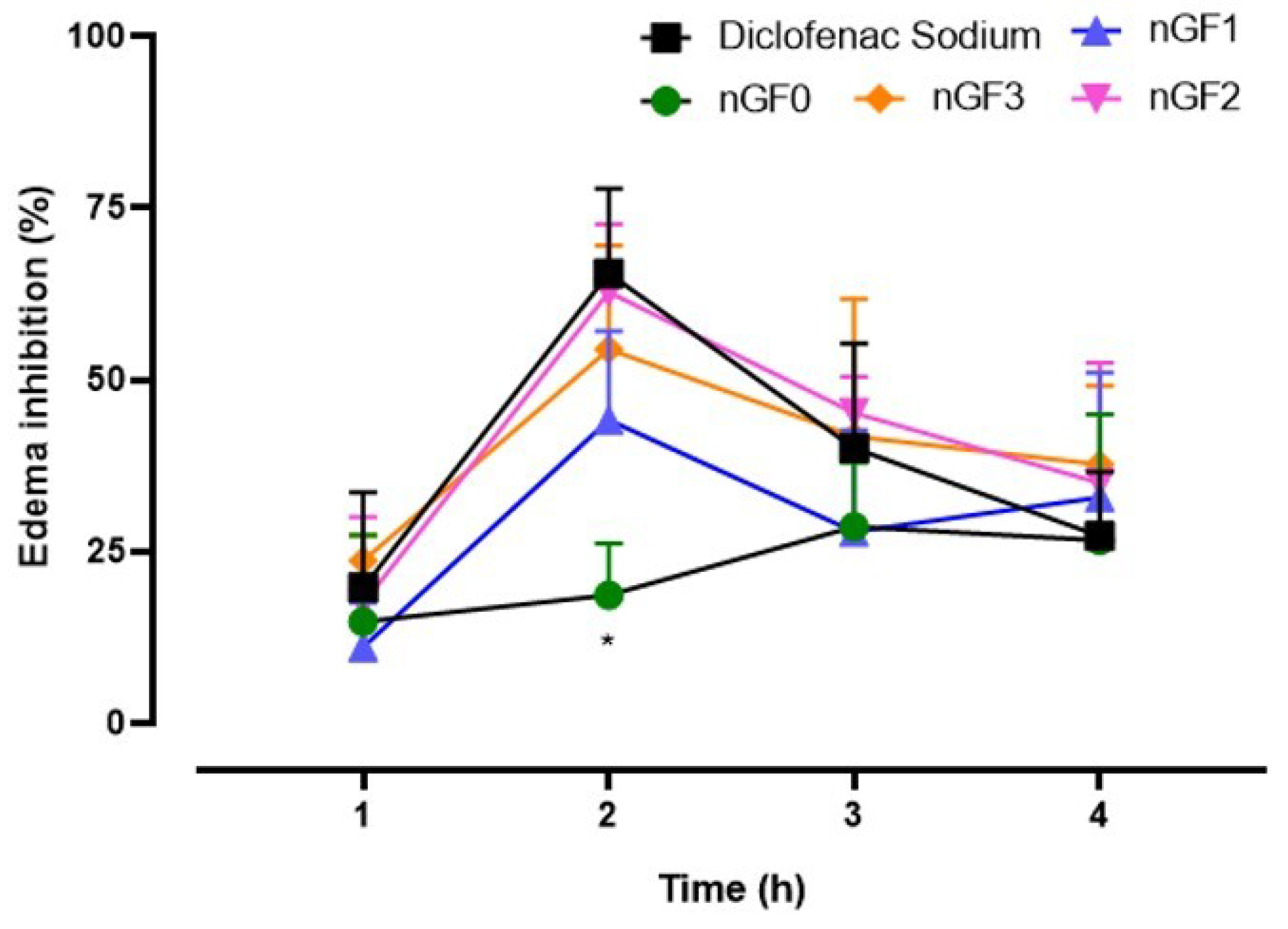

These findings suggest that the nanogel (nGF) shows strong potential as a multifunctional nanocarrier. It demonstrates time- and concentration-dependent efficacy against Leishmania amazonensis promastigotes, with significant potency even at lower concentrations. Mortality rates of 38.15% at 24 h and 33.03% at 48 h were observed, with the cytotoxic effect attributed to the OEPbcomposition in the gel matrix. Additionally, in vivo studies showed that nanogel application at OEPb concentrations of 0.25%, 0.50%, and 1% achieved maximum efficacy 2 h after inflammatory agent inoculation, with edema reductions of 44.1%, 62.7%, and 54.4%, respectively. This ecofriendly nanogel, developed through a low-energy, solvent-free process, presents a sustainable and innovative approach to wound treatment that offers potential as an effective therapeutic solution for CL. By leveraging the potent bioactive properties of EOPb within a biodegradable gel matrix, this formulation aligns environmental responsibility with therapeutic efficacy, positioning it as a promising alternative for sustainable, targeted treatment in the management of leishmaniasis-related skin lesions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Pluronic F127 (poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide)-poly(ethylene oxide) triblock copolymer (MW = 12,600 g/mol; (EOPOEO)), ultrapure water, anhydrous sodium sulfate (≥99%), sodium chloride (≥99%), deuterated chloroform (CDCl), alkane standard mixture XTT (2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide), PMS (N-methyl dibenzopyrazine methyl sulfate), penicillin, streptomycin, fetal bovine serum and amphotericin B were commercially acquired from the Merck company (Rahway, NJ, USA). Carbopol 974P NF polymer was provided by IMCD Brasil (São Paulo, SP, Brazil).

2.2. Plant Material

P. brevipedunculata (Pb) was collected from the Universidade Federal do Maranhão (UFMA) campus in São Luís, Maranhão, Brazil (2° 33’ 20.5"S, 44° 18’ 32.7"W). A voucher specimen (No. 5287) was deposited at the Rosa Mochel Herbarium (SLUI), Universidade Estadual do Maranhão (UEMA), São Luís, MA, Brazil. Plant collection a(D)ered to Brazilian biodiversity protection regulations, registered under SisGen code AAFB38B.

2.3. Extraction Procedure

The essential oil from

Pb (EO

Pb) was extracted via hydrodistillation using a Clevenger-type apparatus following the methodology described in a previous study [

34]. Air-dried

Pb (300 g) was cut into small pieces using pruning shears to optimize extraction efficiency. The plant material was then combined with 500 mL of distilled water in a flask and hydrodistilled for 3 h following reflux onset. Post-extraction, the oil/water mixture was centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min at 25 °C. Remaining water was removed by treating the mixture with anhydrous sodium sulfate, yielding a final EO

Pb yield of 0.80% based on initial plant material weight (

Figure 1).

2.4. CG–MS and NMR analyses of EOPb

The OE

Pb analyses were conducted utilizing GC–MS and NMR techniques, following previously established methodologies [

34]. Briefly, the GC and GC-MS analyses were performed using Shimadzu systems, employing a fused capillary column (RXi-1MS) with helium carrier gas. The temperature program consisted of optimized settings, with samples (10 mg/mL in CH

Cl

injected at a 1:50 split ratio. Retention indices were determined using n-alkane standards, and peak areas and retention times were measured to calculate relative amounts. GC–MS analyses utilized a Shimadzu QP2010 SE system with AOC-20i auto-injector, employing identical conditions to GC. EO components were identified by comparing retention times, indices, and MS spectra with standards and literature data (ADAMS and FFNSC libraries). NMR spectra

1H,

13C and DEPT

13C) were acquired on a BRUKER Avance III HD spectrometer (11.75 Tesla, 500.13 MHz and 125.76 MHz). Samples were dissolved in deuterated chloroform (CDCl

) with chemical shifts reported in ppm relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal reference.

2.5. Preparation of Nanogel Formulations and Stability Evaluation

The nanogel formulations were developed according to a previously published paper [

34]. F127 copolymer (20% w/w) was gradually introduced into cold distilled water maintained in an ice bath (5–10 °C), with gentle stirring to facilitate hydration of each copolymer flake. Subsequently, 974P (0.2% w/w) was added incrementally, and the solution was gently stirred at 5–10 °C until complete dissolution was achieved. Subsequently, EO

Pb was added dropwise to the mixture while stirring continuously for 30 min. The solution was refrigerated overnight at 5 °C to ensure complete solubility of all components (

Figure 1). The formulations were labeled according to the OE

Pb concentration (% w/w): nGF0 (prepared without OE

Pb), nGF1 (containing 0.25%), nGF2 (containing 0.50%), and nGF3 (containing 1.0%). To assess the impact of temperature on the physical and chemical stability of nanogel formulations, accelerated stability tests and shelf-life tests were conducted according to the methodology described in the previously published work [

34], following ANVISA and US Pharmacopeia guidelines.Chemical stability was analyzed using GC-MS by comparing EO

Pb chromatograph profiles over a 28-day period.

2.6. FTIR Analysis

FTIR analyses were performed in reflectance mode using a Shimadzu Tracer-100 FTIR spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan). Nanogel samples were freeze-dried and compressed into pellets with KBr, while pure OEPb was analyzed using Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) mode. The spectrometer was equipped with a horizontal ATR accessory, featuring a ZnSe crystal window (PIKE Technologies) for ATR-FTIR measurements. The spectra were collected within the 400-4000 cm-1 range, with a resolution of 8 cm-1 and 50 scans. For sample preparation, the material was evenly applied to the ATR crystal surface. After each spectrum was acquired, the crystal window was thoroughly cleaned with hexane and acetone before proceeding with further measurements. The UV−Vis absorption spectra of the nanogels, prepared at a concentration of 5.0 x 10-3 g/mL in water, were recorded at room temperature using a Shimadzu UV−Vis 1800 spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan).

2.7. DLS Analysis

Average hydrodynamic diameters (D) analyses were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) in water at 25 °C and 40 mW semiconductor laser of 658 nm with a Litesizer 500 (Anton Paar GmbH) instrument (Module BM 10). The D measurement was performed using a quartz cuvette of 3.0 mL. The potential was performed using a low-volume cuvette (Univette). All the measurements were performed in triplicate (mean ± SD).

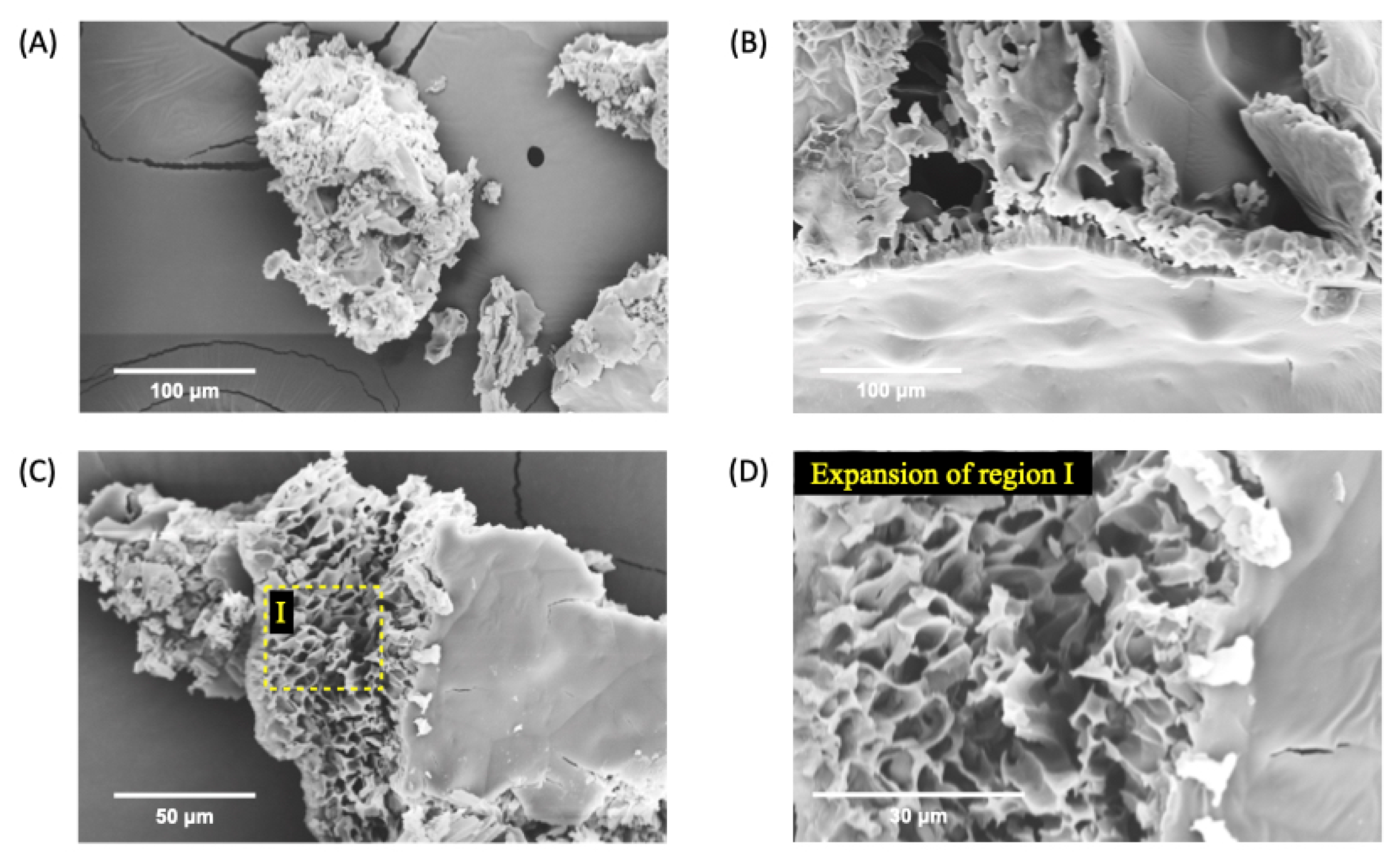

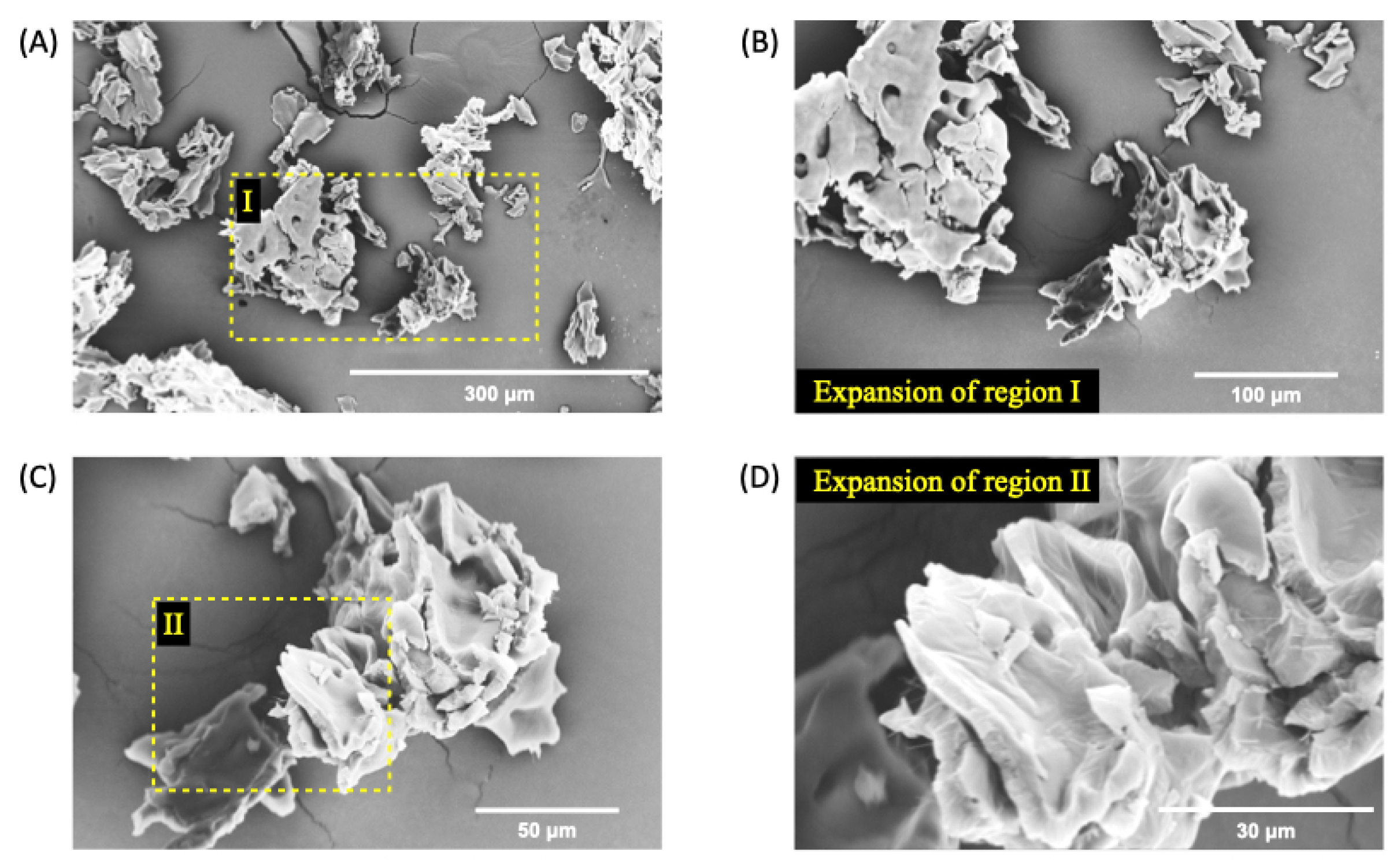

2.8. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

The morphology of nGF0 and nGF3 was examined using SEM analysis. The samples were initially frozen in liquid nitrogen at -196 °C and then lyophilized for 24 h using a Thermo Micro Modulyo freeze dryer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). After lyophilization, the samples were coated with a thin layer of metal using a BAL-TEC SCD 050 Sputter Coater (Balzers, Liechtenstein), and their morphology was analyzed at magnifications of 100x and 50x using a FEI Quanta 250 microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Karlsruhe, Germany).

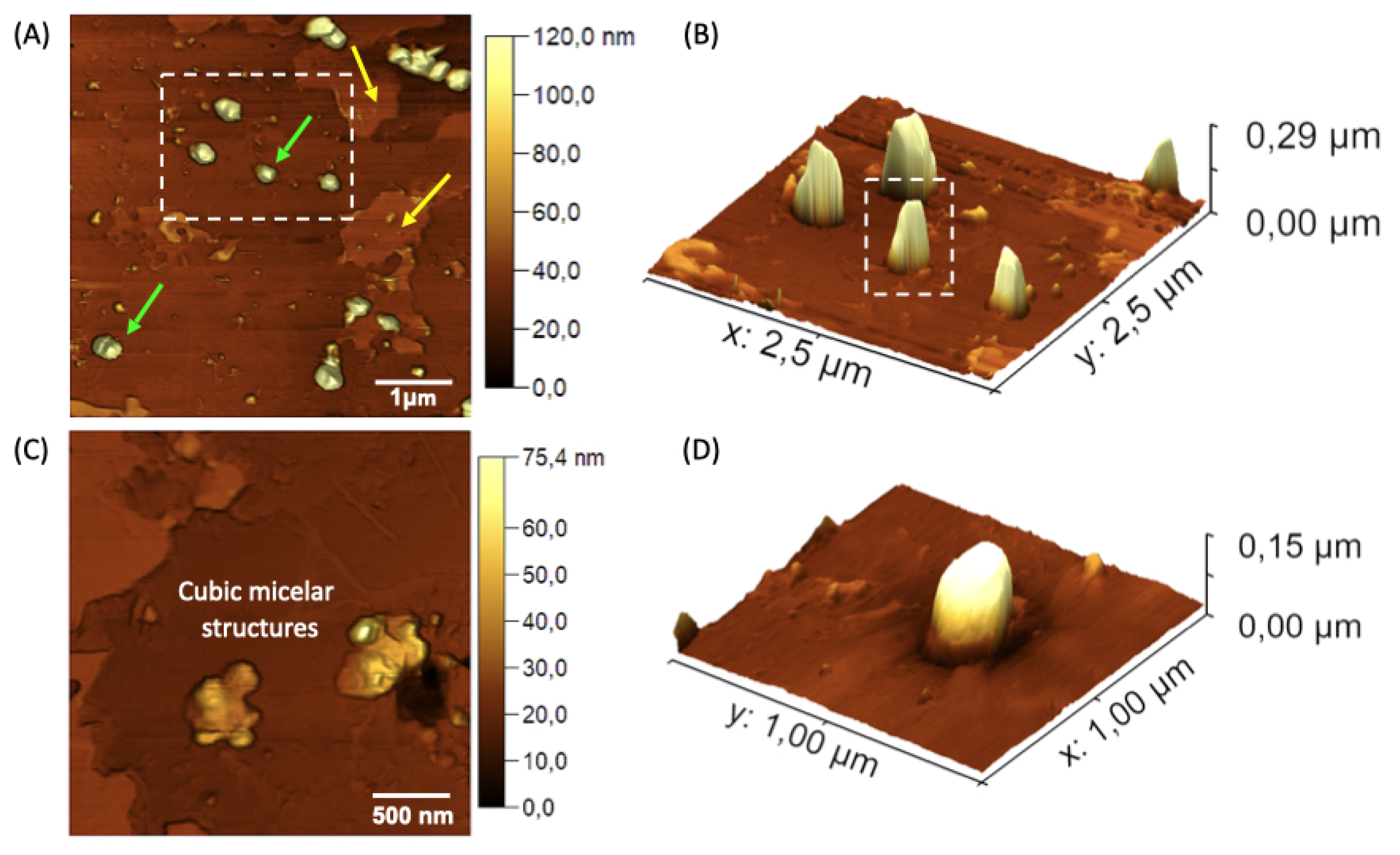

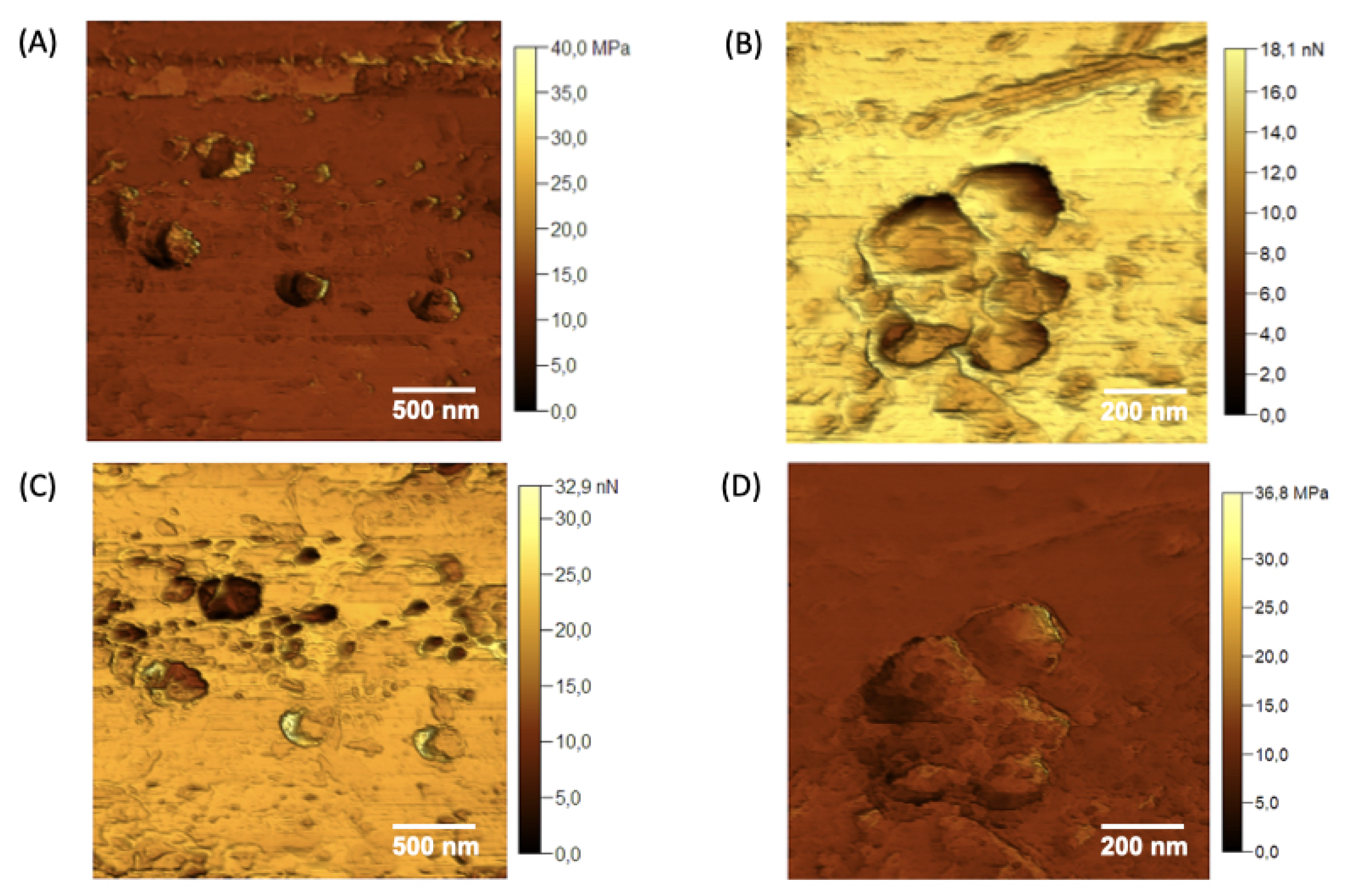

2.9. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

AFM analysis, a Multimode 8 microscope (Bruker, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) was employed, operating in PeakForce Quantitative Nanomechanics (QNM) mode. In this mode, the probe oscillated at 1 kHz, below its resonance frequency, acquiring force curves with each oscillation cycle. Concurrently with force curve acquisition, we obtained nanomechanical properties such as Young’s modulus and adhesion. The probes used in this study had a nominal spring constant of 0.4 N/m and a tip radius of 2 nm (probe brand), with a scan resolution of 256 x 256 lines and a scan frequency of 0.5 Hz per acquired map. Young’s modulus data were derived using the Derjaguin-Muller-Toporov (DMT) model, which characterizes the interaction between an undeformed conical probe and a rigid sample plane. According to the DMT model, force applied to the DMT model between the surfaces is expressed as [

35].

E is Young’s modulus,

Poisson’s ratio,

indentation depth, and

R is the tip radius. Adhesion measurements were calculated from the force curves during the probe-sample interaction. Adhesion is the maximum resistance the AFM probe encounters when detaching from the sample surface [

36]. This resistance manifests as a downward deflection of the cantilever due to attractive forces. Consequently, the adhesion force is identified as the maximum negative force recorded during the retraction phase of the force cycle [

37,

38].

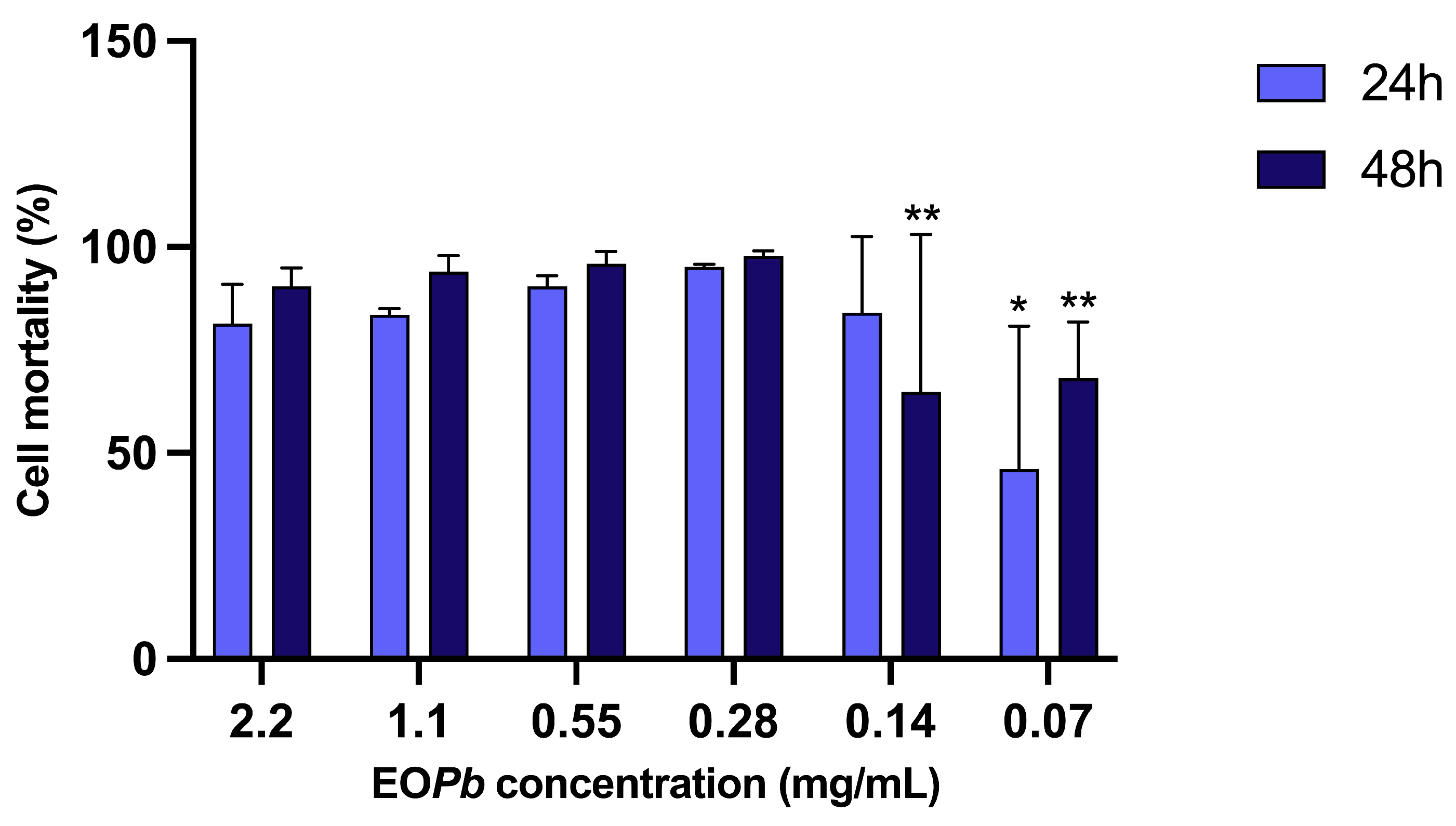

2.10. in vitro Assay against Promastigotes of Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis (LLa)

LLa(strain PH8) cells were cultured in 199 culture medium, supplemented with 10% inactivated fetal bovine serum and antibiotics (100 UI/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin). The cultures were incubated at 27 °C with constant subculturing. In 96-well plates, the culture of LLa promastigotes was seeded in RPMI 1640 medium, resulting in a final concentration of 2 × 107 leishmania/mL after the addition of the compounds. The nanogels were diluted in RPMI 1640 medium and added at concentrations ranging from 2.2–0.7 mg/mL in OEPb. The plates were then incubated at 27 °C for 24, 48, and 72 h. The viability of the promastigotes was determined using the colorimetric XTT method. A mixture containing 20% of XTT:PMS and 60% of NaCl solutin (at concentration of the 0.9%) was added to the plates. The plates were then incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with 5% CO. After this period, absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer with filters set to 450–620 nm, and the percentage of inhibition was estimated by comparison with untreated cells. Amphotericin B was used as a positive control. The experiments were conducted in triplicate and in the absence of light. The percentage of mortality was calculated based on a logarithmic regression of the control curve made only with Leishmania and culture medium, starting with a concentration of 2 × 107 leishmania/mL and diluted in a ratio of two down to a concentration of 6.25 × 105 leishmania/mL.

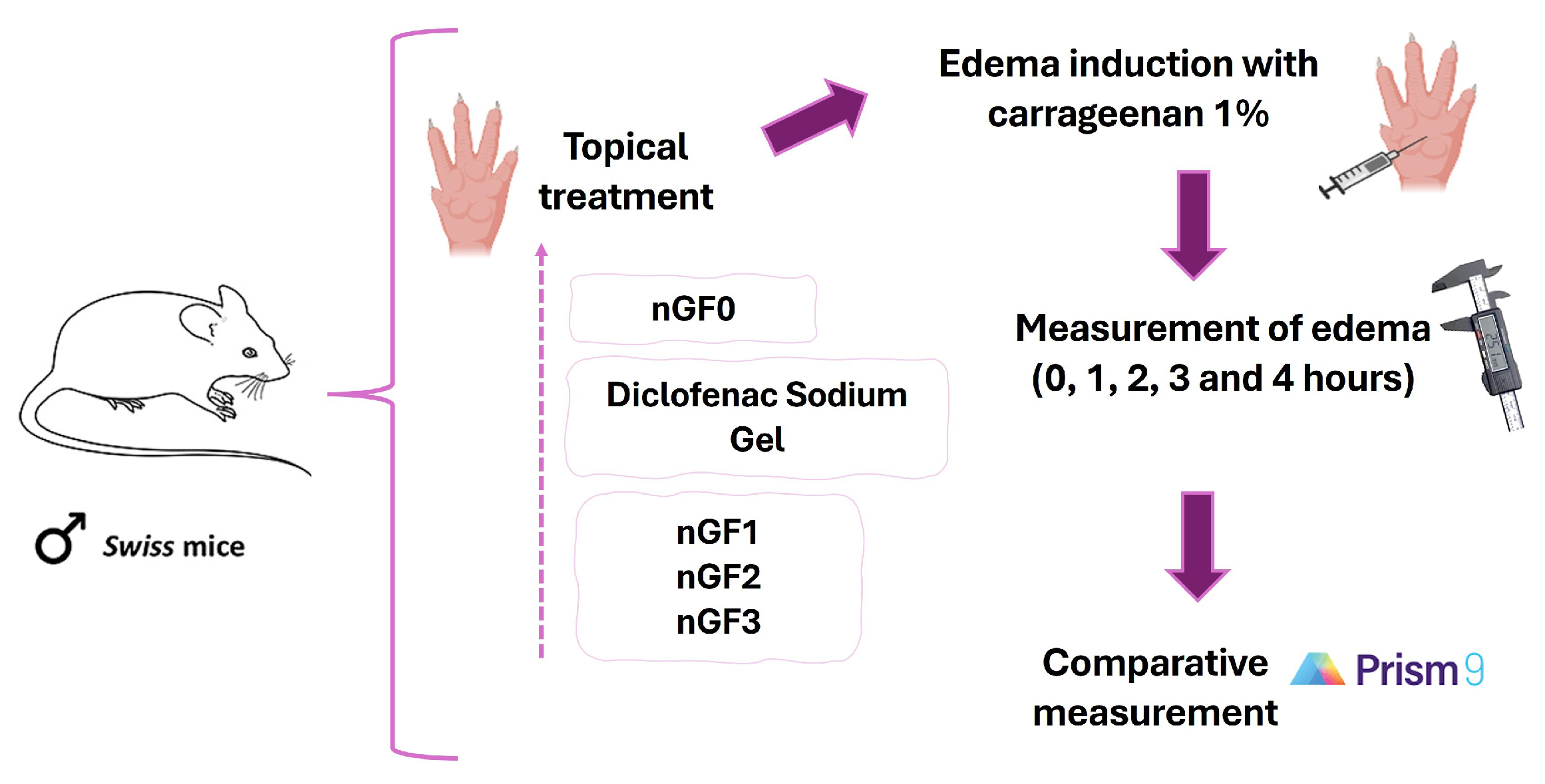

2.11. in vivo Evaluation of the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Nanogels

To characterize the anti-inflammatory effect of the produced nanogels, the carrageenan-induced paw edema experimental protocol was performed in adult male Swiss mice, following the methodology of Sulaiman et al. (2010) with modifications. Approved by the Ethics Committee of CEP-UFMA (Research Ethics Committee of AGEUFMA), under approval code 23115.038817/2024-44, on 1 May 2024. Topical formulations nGF0–nGF3 were evaluated against diclofenac sodium gel 10 mg/g, which was selected as the standard anti-inflammatory topical drug. The animals were divided into six groups (n=5), as follows: Control, which received NaCl 0.9% saline solution; Groups II, III, and IV, which received nGF1, nGF2, and nGF3, respectively; Group V received nGF0, and Group VI received diclofenac sodium gel 10 mg/g. After 1 hour, acute inflammation was induced in the right hind paws of the animals by intraplantar injection of 0.05 ml of carrageenan (1% w/v). A digital caliper was utilized to measure the increase in paw thickness (Ct) immediately following the carrageenan injection (0 h) and then every hour for 4 h thereafter. Any increase in paw thickness was considered an indicator of inflammation (

Figure 2). The calculate inflammation inhibition is expressed as:

Where is the paw measurement after carrageenan treatment at time t, and is the initial (basal) paw measurement.

2.12. Statistical analysis

For the statistical analysis, data were evaluated using a single-criterion approach through ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s post-test for pairwise comparisons and Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc test for non-parametric data. Statistical significance was determined based on predefined criteria. All statistical analyses and graphical representations were performed using Prism 9 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). Values with statistically significant differences were explicitly highlighted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, investigation, writing-original draft, writing—review and editing, E.M.M.; conceptualization, data curation, methodology, formal analysis, L.G.S.A, L.M.R.A, E.R.D.R., R.M.R., R.C.C., G.C.S.M., D.S.S.L.L-N., M.J.S.G., M.V.C.L., M.P.S. and E.V.C.; conceptualization, data curation, methodology, investigation, writing-original draft, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, R.S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

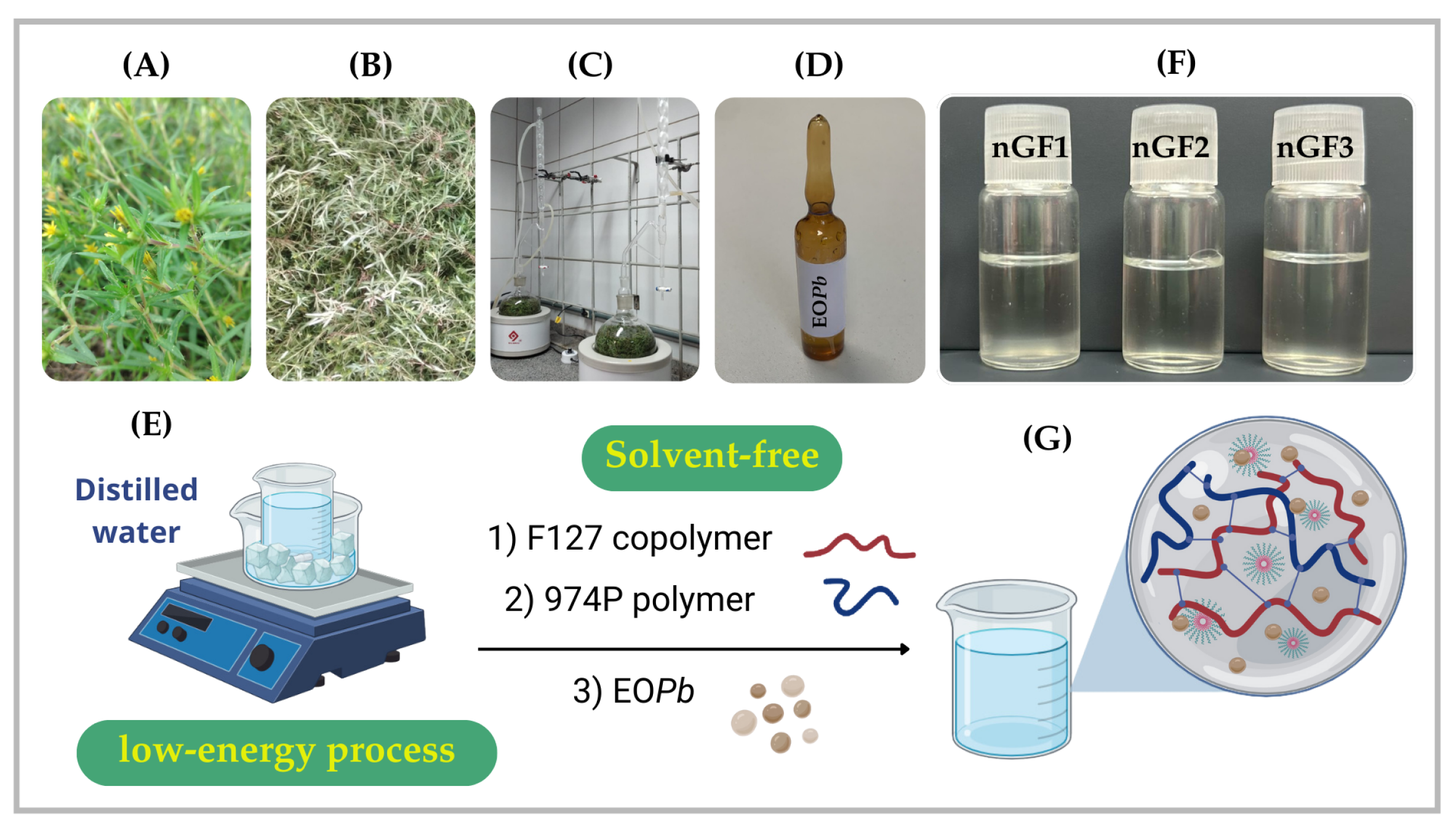

Figure 1.

Experimental sequence for the OEPb extraction procedure: collection of Pb (A), air drying of the plant material (B), grinding and hydrodistillation under controlled conditions (C), followed by drying and storage of OEPb in a sealed amber vial (D). The nanogel preparation methodology was performed using a low-energy, solvent-free procedure (E). Photograph of the nanogels nGF1–nGF3 (F), along with a schematic representation of the structural organization of the F127/974P polymer blend and OEPb-loading F127 micelles (G).

Figure 1.

Experimental sequence for the OEPb extraction procedure: collection of Pb (A), air drying of the plant material (B), grinding and hydrodistillation under controlled conditions (C), followed by drying and storage of OEPb in a sealed amber vial (D). The nanogel preparation methodology was performed using a low-energy, solvent-free procedure (E). Photograph of the nanogels nGF1–nGF3 (F), along with a schematic representation of the structural organization of the F127/974P polymer blend and OEPb-loading F127 micelles (G).

Figure 2.

Experimental sequence for in vivo evaluation of the anti-inflammatory potential of nanogels.

Figure 2.

Experimental sequence for in vivo evaluation of the anti-inflammatory potential of nanogels.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of nGF0 at a magnification of 1000x (A), 2000x (B), and (C), and 5000x (D) after the freeze-dried process.

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of nGF0 at a magnification of 1000x (A), 2000x (B), and (C), and 5000x (D) after the freeze-dried process.

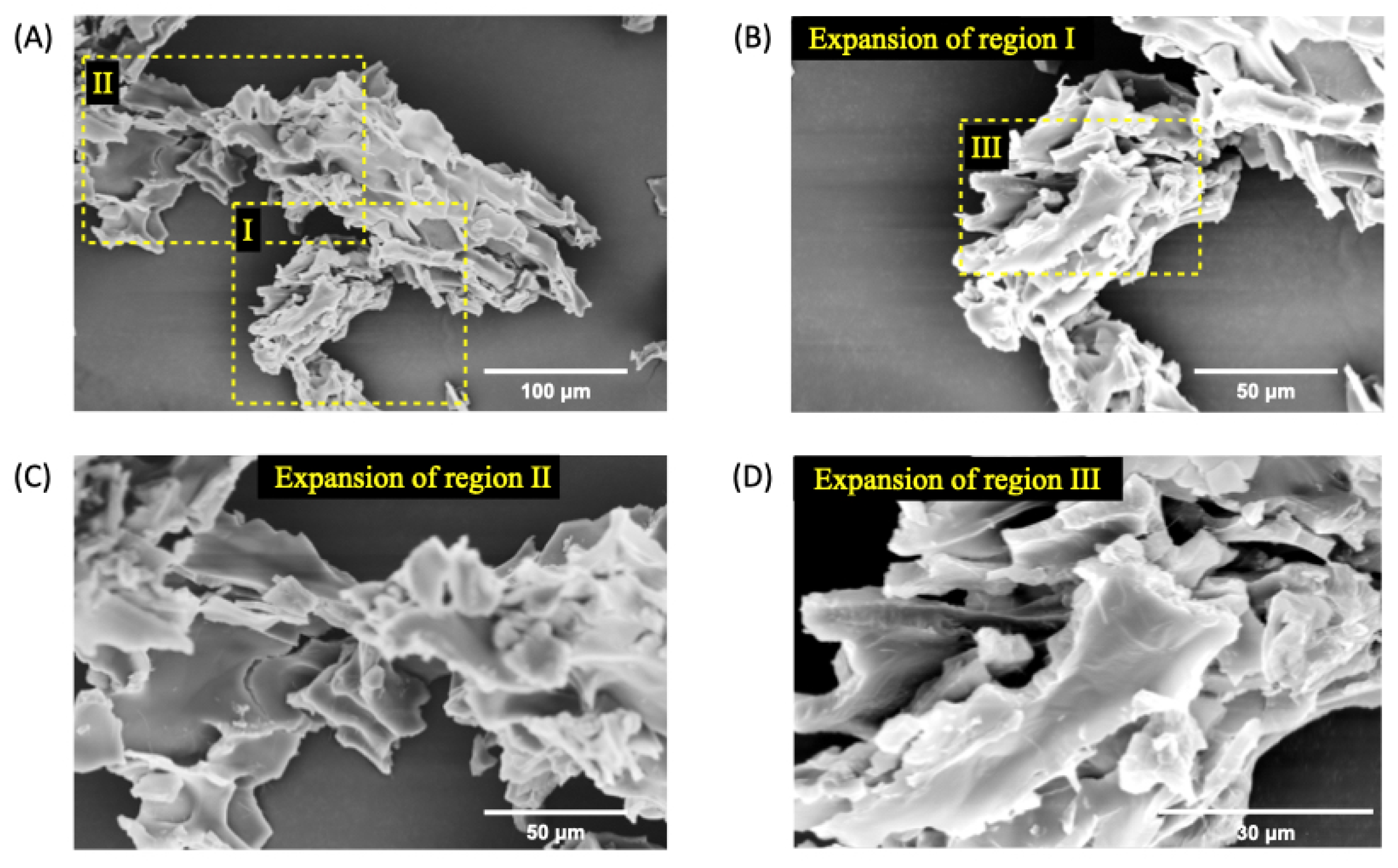

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of nGF3 at a magnification of 500x (A), 1000x (B), 2000x (C), and 5000x (D) after the freeze-dried process. The SEM micrographs show well-defined planar regions with the absence of pores.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of nGF3 at a magnification of 500x (A), 1000x (B), 2000x (C), and 5000x (D) after the freeze-dried process. The SEM micrographs show well-defined planar regions with the absence of pores.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of nGF3 at a magnification of 1000x (A), 2000x (B), and (C), and 5000x (D) after the freeze-dried process. The SEM micrographs show thick planes organized in layers.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of nGF3 at a magnification of 1000x (A), 2000x (B), and (C), and 5000x (D) after the freeze-dried process. The SEM micrographs show thick planes organized in layers.

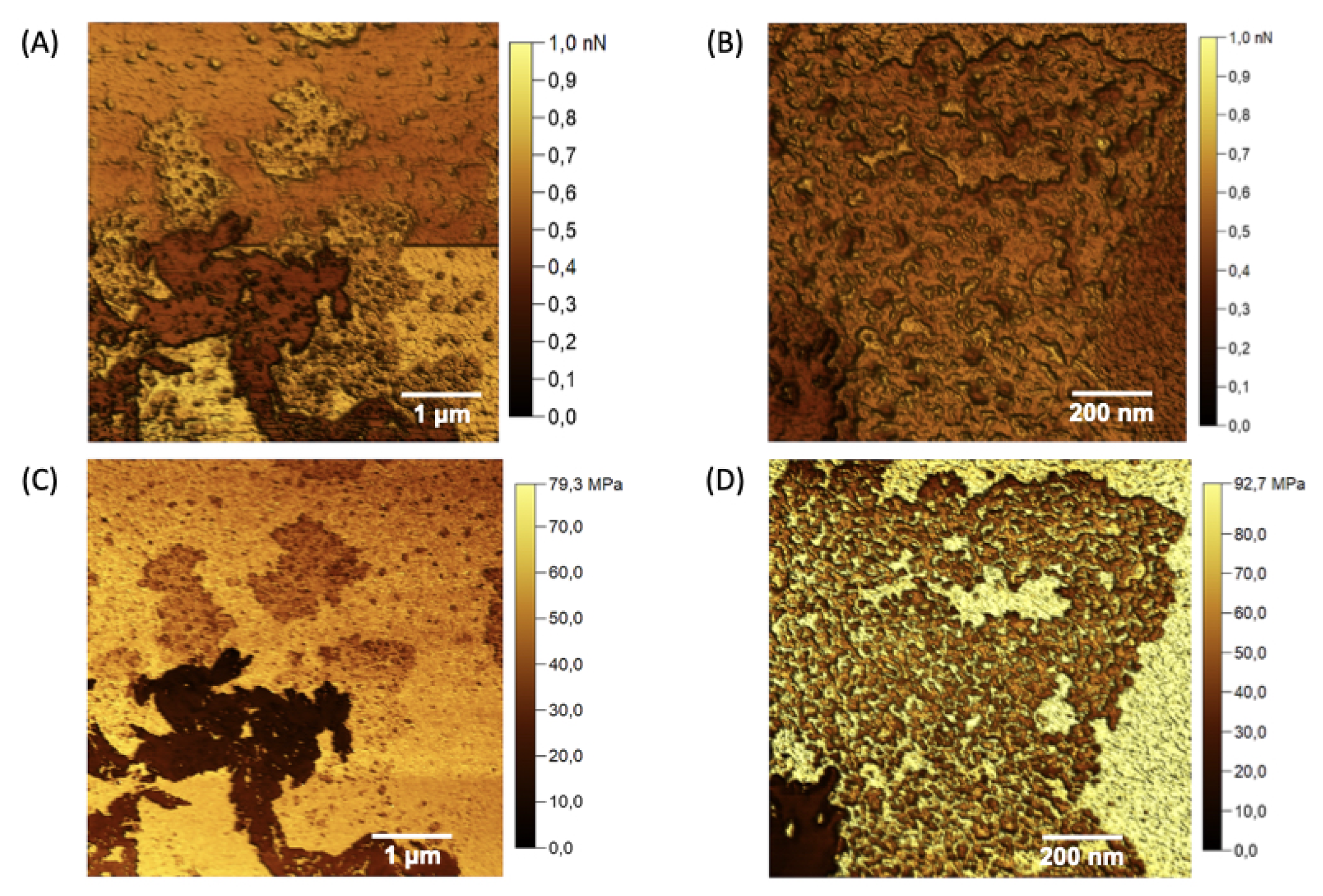

Figure 6.

AFM topographic maps of the nGF0 nanogel. (A) Yellow arrows indicate spherical structures formed by F127 micelles, with an average height of 108.74 ± 19.41 nm (n = 19), and green arrows indicate flat regions with an average height of 5.92 ± 3.00 nm (n = 15). (B) and (D) Expanded 3D micrographs showing the spherical structures in detail. (C) Cubic micellar structures formed by aggregational processes of F127 micelles.

Figure 6.

AFM topographic maps of the nGF0 nanogel. (A) Yellow arrows indicate spherical structures formed by F127 micelles, with an average height of 108.74 ± 19.41 nm (n = 19), and green arrows indicate flat regions with an average height of 5.92 ± 3.00 nm (n = 15). (B) and (D) Expanded 3D micrographs showing the spherical structures in detail. (C) Cubic micellar structures formed by aggregational processes of F127 micelles.

Figure 7.

Young’s modulus maps (A) and (B), and adhesion force maps (C) and (D) were acquired for the different domains observed in the nGF0.

Figure 7.

Young’s modulus maps (A) and (B), and adhesion force maps (C) and (D) were acquired for the different domains observed in the nGF0.

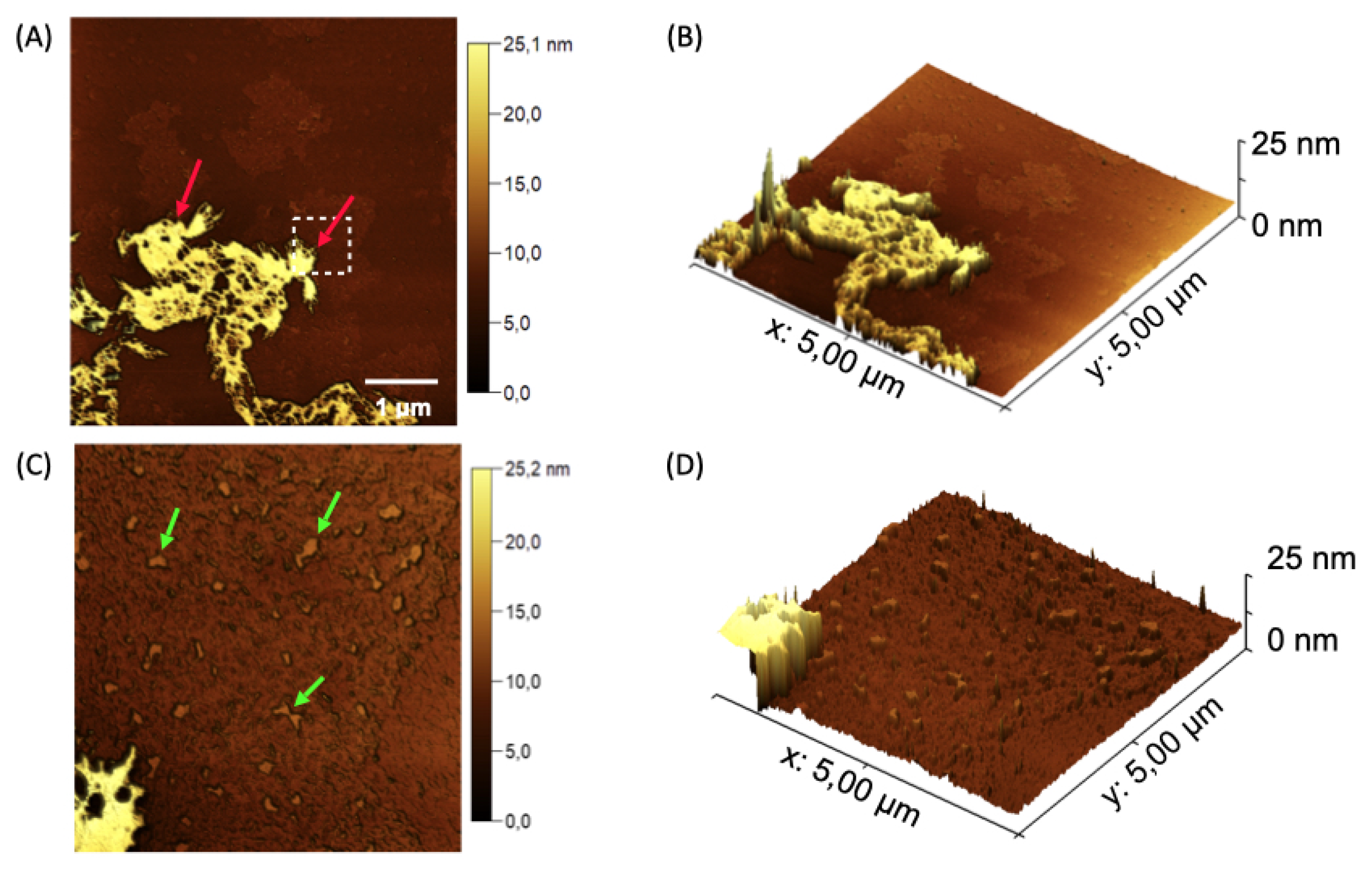

Figure 8.

Topographical AFM maps of the nanogel nGF3. (A) Red arrows indicate flat structures formed by the presence of EOPbon the surface of the nGF0 matrix, with an average height of 7.39 ± 0.79 nm (n = 17). (B) Green arrows indicate the incorporation of EOPb into the F127 micellar structures and the pores of the nGF0 material, with average height values of 1.37 ± 0.21 nm (n = 20) and size of 40.58 ± 7.98 nm (n = 20. (C) and (D) 3D micrographs showing the flat nGF3 structures.

Figure 8.

Topographical AFM maps of the nanogel nGF3. (A) Red arrows indicate flat structures formed by the presence of EOPbon the surface of the nGF0 matrix, with an average height of 7.39 ± 0.79 nm (n = 17). (B) Green arrows indicate the incorporation of EOPb into the F127 micellar structures and the pores of the nGF0 material, with average height values of 1.37 ± 0.21 nm (n = 20) and size of 40.58 ± 7.98 nm (n = 20. (C) and (D) 3D micrographs showing the flat nGF3 structures.

Figure 9.

Maps of Young’s modulus (A) and (B), and adhesion forces (C) and (D) acquired for the nanogel nGF3.

Figure 9.

Maps of Young’s modulus (A) and (B), and adhesion forces (C) and (D) acquired for the nanogel nGF3.

Figure 10.

in vitro leishmanicidal activity of nanogel formulation (nGF3) demonstrating concentration and time dependent efficacy against LLa (p < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc test).

Figure 10.

in vitro leishmanicidal activity of nanogel formulation (nGF3) demonstrating concentration and time dependent efficacy against LLa (p < 0.05, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc test).

Figure 11.

Topical anti-inflammatory action of nanogels in an experimental paw edema model in mice (p < 0.05, ANOVA, Tukey Test).

Figure 11.

Topical anti-inflammatory action of nanogels in an experimental paw edema model in mice (p < 0.05, ANOVA, Tukey Test).

Table 1.

Infrared Spectroscopy data for EOPb and nGF3 Compounds

Table 1.

Infrared Spectroscopy data for EOPb and nGF3 Compounds

| Compound |

Wavenumber (cm) |

Assignment |

Compound class |

|

2954 |

C—H stretching |

Alkene |

| |

2920 |

C—H stretching |

Alkane |

| |

2870 |

C—H stretching |

Aldehyde |

|

EOPb

|

1712 |

C=O stretching |

Aldehyde |

| |

1674 |

C=C stretching |

Alkene |

| |

1442 |

C—H scissoring |

Alkane |

| |

1377 |

C—H rock |

Alkane |

| |

1141 |

C—O stretching |

Aldehyde |

| |

840 |

C=O bending |

Aldehyde |

| nGF3 |

3676 |

O—H stretching |

Alcohol |

| 3340 |

O—H stretching |

Hydrogen bond |

| 1732 |

C=O stretching |

Aldehyde |

| 1103 |

C—O—H stretching |

Ether |

Table 2.

Particle size measurements (nm) of nGF0 and nGF3 nanogels obtained using DLS and AFM techniques, expressed as D ± Standard Deviation (SD), PDI, Height (H) and Diameter (D) ± SD.

Table 2.

Particle size measurements (nm) of nGF0 and nGF3 nanogels obtained using DLS and AFM techniques, expressed as D ± Standard Deviation (SD), PDI, Height (H) and Diameter (D) ± SD.

| Measurement |

nGF0 |

nGF3 |

| DLS: D ± SD; PDI |

661.03 ± 6.1; 0.34 |

30.44 ± 12.1; 0.54 |

| AFM: D ± DS (nm) |

279.09 ± 38.93 |

40.58 ± 7.98 |

| AFM: H ± DS (nm) |

108.74 ± 19.41 |

1.37 ± 0.21 |