1. Introduction

The use of fossil fuels to fulfill green energy requirements is predicted to increase. Due to the negative impact of fossil resource consumption on environmental contamination, there has been a developing corpus of research focusing on alternative fuel sources [

1,

2]. Biodiesel, a renewable energy source, is widely regarded as indispensable for the preservation of a healthy ecosystem [

3,

4]. Utilizing biodiesel has numerous advantages. This particular characteristic's non-toxic nature ensures safety and cost-effectiveness, which is a notable advantage [

5]. The production of biodiesel involves a series of chemical reactions that result in the formation of free radicals susceptible to oxidation in the surrounding atmosphere. Ensuring the preservation of biodiesel's storage stability is crucial to assessing its overall quality. Therefore, it is crucial to emphasize the utmost importance of standards and gasoline quality certification in Europe [

6,

7]. When there is instability in the fuel, blends form. These blends can then lead to the formation of injector deposits or particles that can block fuel filters or the fuel injection system. The necessity of a stability additive exhibits significant variation across different types of fuels. The variability in fuel quality is contingent upon factors such as the method of fuel production, the origin of the crude oil, and the specific processes and blending techniques employed at the refinery [

8,

9]. Stability additives commonly function by obstructing a specific stage within a complex series of reactions. The efficacy of an addition to one fuel may be compromised when applied to another due to the intricate chemical interactions involved. In order to achieve fuel stabilization, it is necessary to conduct testing to determine the appropriate additive and treatment rate. Optimal outcomes are achieved when the additive is introduced promptly subsequent to the fuel's production process [

10,

11]. Additives for fuel stability are used because adding antioxidants greatly improves the quality, storage stability, and durability of biodiesel [

12]. These additives include stabilizers, dispersants, and metal deactivators [

13]. Schiff bases are chemical compounds characterized by the general formula RCH=NR'. The formation of an imine group (>C=N) results from the condensation reaction between aldehydes or ketones and primary amines, which produces these compounds. The condensation process, specifically nucleophile addition removal involving carbonyl compounds, generates Schiff bases [

14,

15]. In contemporary times, Schiff bases have gained prominence in the realm of medicinal and biological applications. These compounds hold promise as prospective medication substances and are utilized as diagnostic tools for diseases. Certain complexes that include radioactive nuclei exhibit features such as antioxidant, anticancer, antibacterial, and antiviral activities. Schiff bases are useful in many situations because they are very stable at high temperatures, they can form liquid crystals, they can bind other molecules, they are semiconductors, they have optical properties, and they may even be useful for medicine [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Schiff bases can improve the quality of biodiesel-diesel blends in two ways: first, they can do this by forming complexes with metal ions that deactivate the metals; and second, they can do this by trapping radicals in biodiesel-diesel blends and stopping the chain reaction of radical reactions. To begin, Schiff bases are likely to react because they have a nitrogen atom in the azomethine group. This nitrogen atom is in the sp

2 hybrid orbital and has an unpaired electron pair [

23,

24]. The excellent chelating capabilities of Schiff bases have garnered significant recognition in the academic community. The presence of minute quantities of some metals in diesel fuel has been seen to behave as catalysts, expediting the processes associated with fuel instability. Metal deactivators function by chelating the metals, effectively neutralizing their catalytic activity [

25]. Typically, they are employed within the concentration range of 1 to 15 ppm. The Schiff bases exhibit a high propensity for metal chelation owing to their dentate character. As a result, they function as metal deactivators within biodiesel-diesel blends [

26,

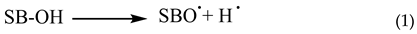

27]. The intricate arrangement of Schiff bases with metal ions (M) is depicted in

Figure 1.

Secondly, Schiff bases have been the subject of research that indicates their potential as effective antioxidant compounds. Antioxidants are a group of chemicals that effectively halt the process of oxidation [

28,

29]. Inhibiting the production of free radicals or the scavenging of already existing radicals effectively controls the oxidation process of biodiesel, even when present in small amounts. The chemical structure of antioxidants commonly includes phenolic functional groups. The degradation of biodiesel has shown a significant reduction. Recent studies have indicated that the use of both natural and synthetic antioxidants is imperative for the purpose of augmenting and optimizing the oxidative stability of biodiesel. The utilization of antioxidants underscores the importance of diminishing the presence of free radicals in biodiesel and prolonging the process of oxidation [

9,

30]. Phenolic antioxidants (AH) are frequently employed as free radical scavengers due to their advantageous properties. Phenic acid antioxidants have long lasting radical intermediates that stop molecular oxygen from attacking these areas because of resonance delocalization. Additionally, phenolic antioxidants have strong hydrogen donating capabilities [

31,

32,

33].

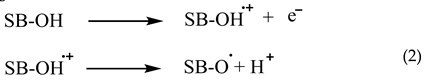

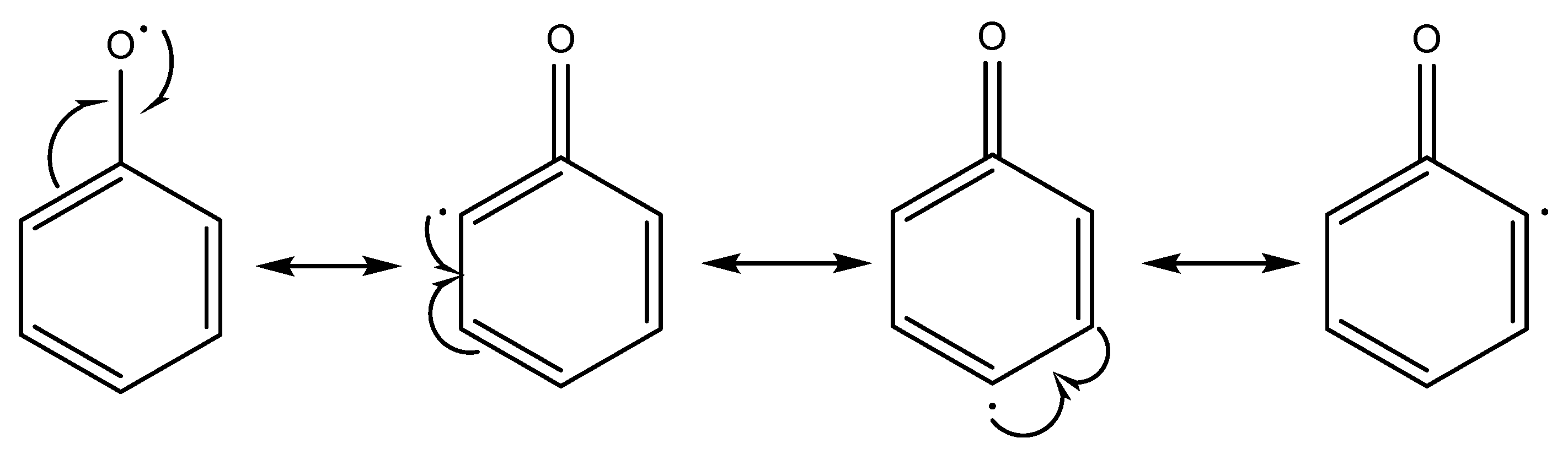

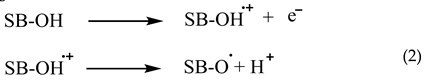

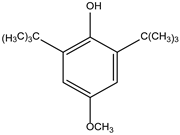

Figure 2 shows how the phenoxy radical becomes more stable and the mismatched electrons move around the aromatic system.

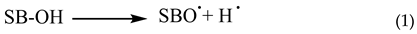

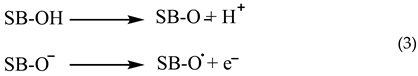

The capacity to scavenge free radicals is a prevalent characteristic shown by phenolic compounds. The antioxidative action of phenolic Schiff bases (SB-OH) is closely associated with their capacity to liberate hydrogen atoms. There are a variety of methods for removing free radicals, including hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), single electron transfer followed by proton transfer (SET-PT), and sequential proton loss electron transfer (SPLET). All of these methods provide the same outcome, specifically the generation of the appropriate phenoxy radical. The hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) process is characterized by a single step in which a hydrogen atom is converted to a free radical.

The SET−PT and SPLET mechanisms are comprised of a two step process. In the SET−PT mechanism, the initial step involves the loss of one electron, resulting in the creation of a radical cation. Subsequently, in the second step, the radical cation undergoes deprotonation, leading to the formation of the corresponding radical.

The initial step in the SPLET process is the deprotonation of the parent molecule. During the second stage, the anion undergoes electron loss, resulting in the formation of a matching radical [

24,

25,

34,

35].

Schiff bases were made, and their chemical makeups were figured out using FT-IR,

1H NMR–

13C NMR (in DMSO-d

6), and elemental analysis, among other methods. The determination of the in vitro antioxidant properties of all structures was conducted using the DPPH

• free radical capture and ABTS

•+ radical cation scavenging activities techniques [

18,

30]. The results are presented with the IC

50 values that have been computed. Schiff base derivatives were added, and a concentration of 3000 ppm was added to the mixtures [

36]. Several characterization techniques, including DSC, TGA, and FT−IR, were used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of fuels [

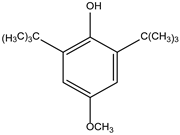

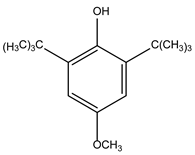

37]. The use of BHT, also known as 2,6-di-tert-butyl-

p-cresol (DBPC), resulted in comparisons between the experimental results and those BHT is a synthetic phenolic antioxidant that is extensively employed as a food additive. Because it is made up of phenolics, BHT helps to free hydrogen from phenolic hydroxide groups and stop the formation of free fatty acid radicals at the carboxyl end of the fatty acid. The substance exhibits a notable antioxidant capacity. The process has been found to improve the effectiveness of the oils and help prevent the formation of deposits. BHT is utilized in various industries, including the food and rubber sectors, metallurgy, cosmetics, medicines, embalming liquids, antifreeze, auto chemistry liquids, and the fuel business [

38,

39].

Table 1 displays the antioxidant properties and structural formula of BHT.

2. Materials and Methods

Compounds sourced from reputable suppliers such as Merck, Sigma, and Aldrich Chemical Company were utilized in their original form without undergoing additional purification. The experiment utilized a solvent of high spectroscopic quality. We conducted an elemental analysis using a CHNS-932 (LECO) instrument. We took 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra (in DMSO-d6) at 25 °C using an Agilent Premium Compact spectrometer operating at 14.1 Tesla and 600 MHz. Gallenkamp melting point equipment determined the melting points. Methods used to measure the ability of the resulting mixtures to exhibit antioxidant activity: We used SDTQ 600 for the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and DSCQ 2000 for the differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). We plotted TGA and DSC graphs using the software Universal Analysis 2000/XP/Vista Version 4.5A. We used ATR-FTIR (Perkin Elmer, Spectrum-Two, USA) to perform Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR).

The Biodiesel Corporation, known as Aves Energy Oil and Food Industry, and the Fuel Corporation, referred to as OPET, have both played a substantial role in enabling widespread commercial availability of neat aspire biodiesel (B100) and neat diesel fuel (D100) in the Turkish market. The chemical properties of aspire oil methyl ester (AME) are shown in

Table 2.

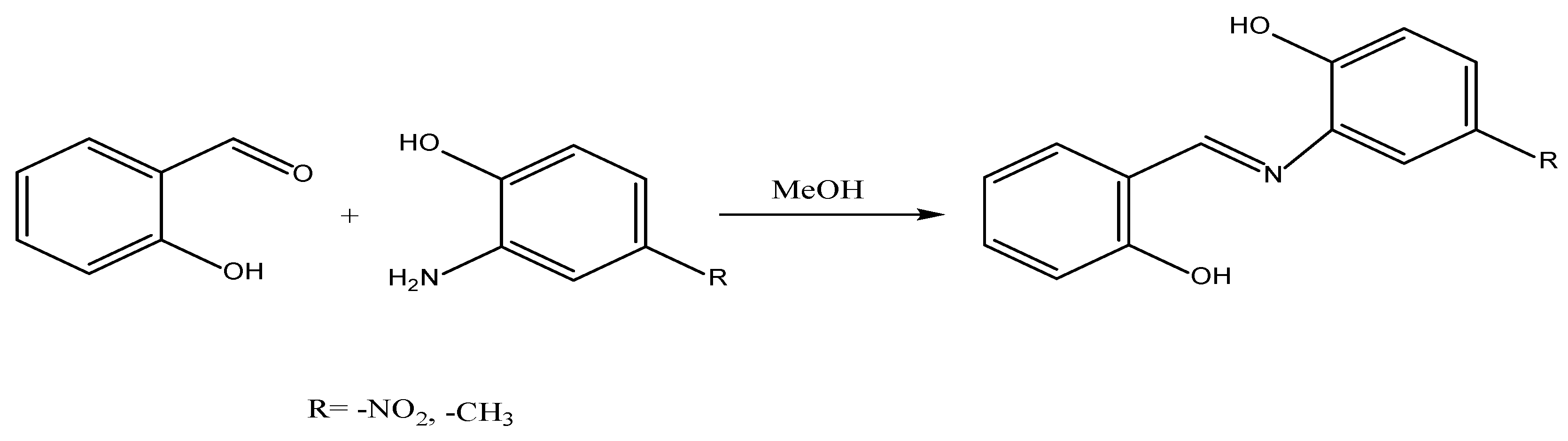

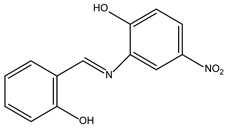

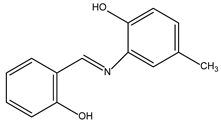

2.1. Experimental Stage: Schiff Base Synthesis

The objective of this study was to investigate the outcomes of incorporating. Schiff bases have antioxidant activity and possess the ability to deactivate metals. The initial compound of salicylaldehyde reacts with the compounds of 2-amino-4-methylphenol and 2-amino-4-nitrophenol respectively, resulting in the synthesis of Schiff bases with two different substantions. The synthesized Schiff bases were characterized using various analytical techniques such as TLC, MP, FT-IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and elemental analysis. Furthermore, the antioxidant properties of these compounds were assessed using the DPPH. free radical trapping and ABTS•+ radical cation scavenging activities techniques. The biodiesel to diesel ratio in diesel-biodiesel blends typically varied between 30% and 70%. The mixture was denoted by the formula B30D70. A mixture of plant extracts was prepared at a concentration of 3000 ppm. In order to evaluate the potential additive effects of Schiff bases, these compounds were incorporated into blends and subjected to analysis using an oxifast device. The performance of these blends was compared to BHT, a chemical antioxidant. The experimental samples were meticulously prepared and assigned the following designations: D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1. The samples underwent characterization through the utilization of several analytical techniques, DSC, TGA, and FT-IR.

Salisylaldehyde (2-hydroxybenzaldehyde) is reacted individually with 2-amino-4-methylphenol and 2-amino-4-nitrophenol, each in mmol quantities. Acetic acid acts as a catalyst to individually adjust the resulting mixtures, and then absolute methyl alcohol dissolves them. Subsequently, the mixtures are combined and heated separately using a refrigerator. An executive phase TLC analysis using a 4:1 mixture of n-hexane and ethyl acetate is used to track the reactions as they happen [

40]. The resulting product of the reaction is subjected to multiple washes with warm distilled water, methyl alcohol, and diethyl ether. It is then dried under vacuum conditions, and its structure is elucidated [

41,

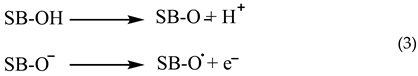

42]. The reaction of Schiff's base synthesis is given in

Figure 3. Physical properties, efficiency values, melting points, and results of elemental analysis of synthetic Schiff bases are given in

Table 3.

The compound 1 is chemically synthesised as (E)-2-((2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino)-4-nitrophenol. The following is the analytical summary of the compound: FT-IR (cm-1): 3695 (O−H), 2926 (aromatic C−H), 2856 (aliphatic C−H), 1725 (C=N), 1619 (aromatic C=C), 1462 (asymmetric N=O), 1380 (symmetric N−O), 1255 (C−N); 1 H NMR (600 MHz, in DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 10.96 (s, 1H), 10.17 (s, 1H), 8.81 (s, 1H), 6.74–7.81 (m, 7H), 2.11 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (600 MHz, in DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 166.56, 162.24, 162.01, 155.08, 44.92, 131.06, 128.42, 124.71, 123.53, 119.38, 115.60, 112.01, 105.88.

Compound 2 is synthesised as ((E)-2-((2-hydroxybenzylidene)amino)-4-methylphenol). The following is the analytical summary of the compound: FT-IR (cm-1): 3034 (O−H), 2925 (aromatic C−H), 2872 (aliphatic C−H), 1618 (C=N), 1485 (C=C), 1232 (C−N); 1H NMR (600 MHz, in DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 9.53 (s, 1H), 9.08 (s, 1H), 8.74 (s, 1H), 5.27–8.72 (m, 7H); 13C NMR (600 MHz, in DMSO-d6, ppm): δ 160.95, 159.82, 156.48, 146.70, 135.65, 134.32, 131.63, 124.43, 121.57, 120.31, 111.96, 108.27. The solvent peak was seen at a chemical shift of 2.50 ppm, whereas the water peak was detected at a chemical shift of 3.35 ppm.

2.2. Formulation of Biodiesel-Diesel Blends

The biodiesel to diesel ratio in diesel and biodiesel blends often ranged from 30% to 70%. The combination being mixed was represented by the formula B30D70. The combination of extracts from many plants was performed at a concentration of 3000 ppm [

41]. The contents and sample codes are presented in

Table 4.

2.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC methods can be employed for the goal of characterizing, quantifying, and inferring. The main aim of this study was to examine the temperatures at which the process of crystallization starts, as measured in degrees Celsius, for the following materials: D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_

2, and B30D70_

1. The experiment utilized a DSC Q-2000 calorimeter, manufactured by TA Instruments-Waters, a US-based company. The calorimeter was equipped with an RCS 90 and a cooling mechanism. Aluminum pans were employed for the purpose of performing analysis. During the course of the experimental procedure, a sample weighing 5 ± 0.5 mg was meticulously placed into the pan. The study conducted by indicated that the cooling rate throughout the temperature range of 25 °C to -90 °C was found to be 10 °C per minute, while a consistent nitrogen flow rate of 50 mL per minute was maintained [

42,

43].

2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA is frequently utilized to examine the relationship between alterations in mass and temperature fluctuations, whether increasing or constant, under controlled atmospheric conditions. This analytical technology is employed to quantify vapors, assess combustion reactions, investigate degradation processes, and determine residual components in products. TGA technique has been employed to observe the decomposition characteristics of various organic compounds and the potential improvement of their constituents [

44]. The TGA analysis was performed using an SDT Q-600 apparatus manufactured by TA Instruments-Waters, a US-based company. The acquisition of the samples involved exposing five powder samples, with a weight of 5 ± 0.5 mg each, to a heating procedure at a rate of 10 °C per minute. The heating procedure was conducted within an alumina pan, while ensuring a consistent oxygen gas flow rate of 50 mL per minute throughout the duration of the process. The temperature was gradually raised until it reached a value of 400 °C, as recorded in the scientific literature [

45].

2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT−IR)

The chemical functional groups present in Schiff base derivatives and fuels blends were analyzed using FT-IR (Perkin Elmer, Spectrum-Two, USA). The spectral range spanning from 650 to 4000 cm

-1 was employed to conduct a surface scan of the material. ATR FT-IR spectra were acquired with an isothermal technique at ambient temperature. [

46]

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.6.1. DPPH. Method for Antioxidant Activity

The determination of the free radical scavenging activity of samples

1 and

2, together with BHT, was conducted using the DPPH

˙ method [

47]. A homogenous mixture was created by combining 150 µL of various concentrations of the sample and standards (BHT) with 50 µL of 0.1 mM DPPH

˙, which was generated using ethanol, on a 96-well plate. The plate was incubated at ambient temperature in a light restricted environment for a duration of 30 minutes. The absorbance values of each combination were quantified using a BioTek (Epoch2) microplate reader at a wavelength of 517 nm. The findings were subsequently calculated by computing the IC

50 values in units of micrograms per milliliter (μM).

The % inhibition of the free radical concentration was computed for the sample compounds and subsequently compared to the standard. The calculation of the percentage of inhibition of radical scavenging activity was performed using the formula denoted as Equation 6.

The variable "Ac" represents the absorbance value of the control, whereas "A" represents the absorbance value of the test substance or standard. In addition, the determination of IC

50 values was carried out by the utilization of a calibration curve. The IC

50 value is established by measuring the concentration of all components necessary to achieve a level of inhibition that is half of the maximum. A lower IC

50 value indicates a higher level of antioxidant activity [

48,

49].

2.6.2. ABTS•+ Method for Antioxidant Activity

The assessment of the radical cation scavenging activity of samples

1 and

2, together with BHT, was carried out utilizing the ABTS

•+ method. In a 96-well plate, 20 µL of various concentrations of the sample and standards (BHT) were mixed with 180 µL of ABTS

•+. The ABTS

•+ solution was prepared by combining 7 mM ABTS

•+ with 2.45 mM Potassium persulfate, and the resulting solution had an absorbance value of 0.700 ± 0.02. The mixture was thoroughly mixed to ensure homogeneity. The plate was left at room temperature for a duration of 6 minutes. The absorbance values of each mixture were measured using a BioTek (Epoch2) microplate reader at a wavelength of 734 nm. The results were determined by calculating the IC

50 values in units of micrograms per milliliter (μM). These values indicated that the sample's ABTS

•+ scavenging activity was less than half that of the standard substance [

50,

51].

3. Results and Discussion

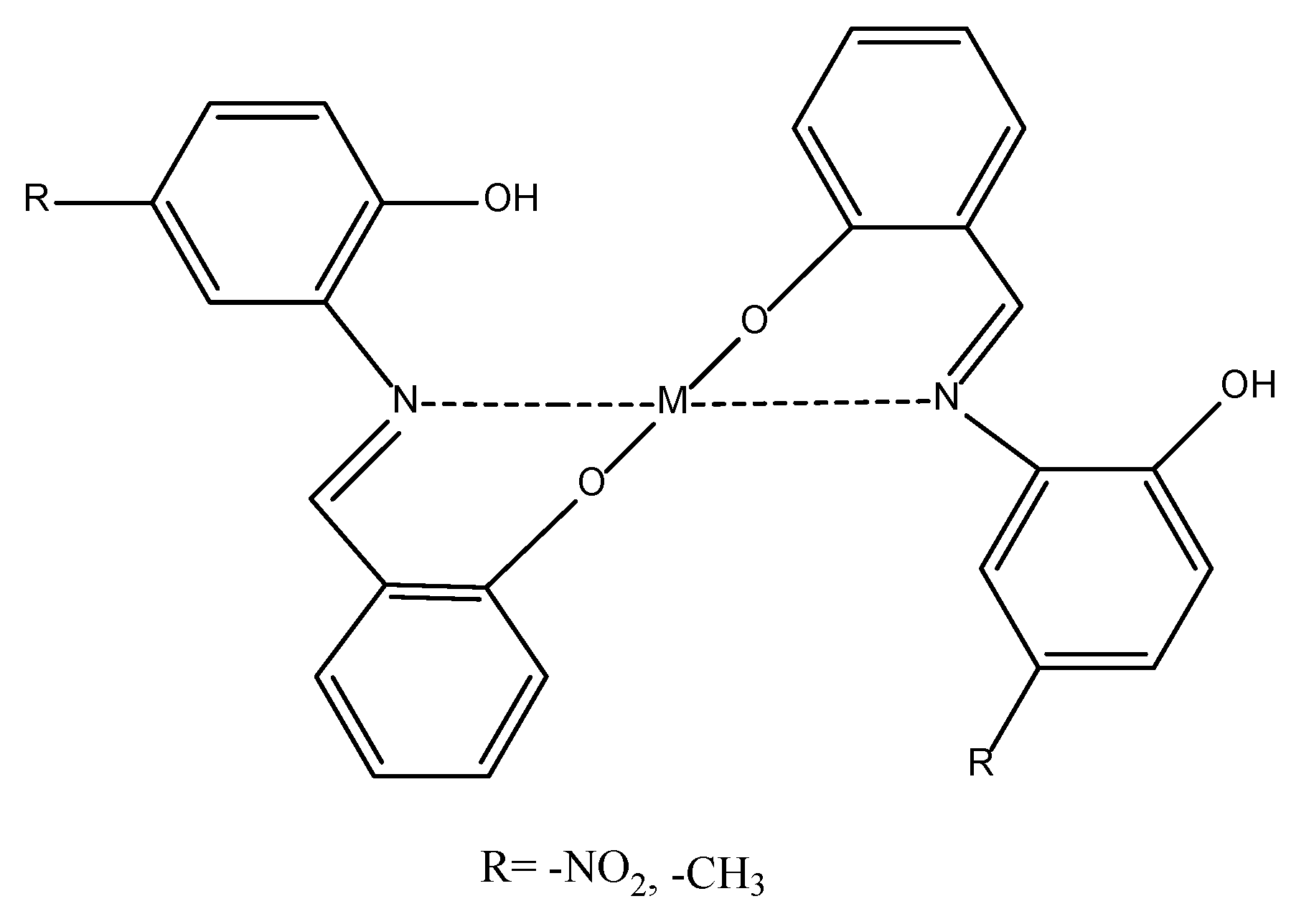

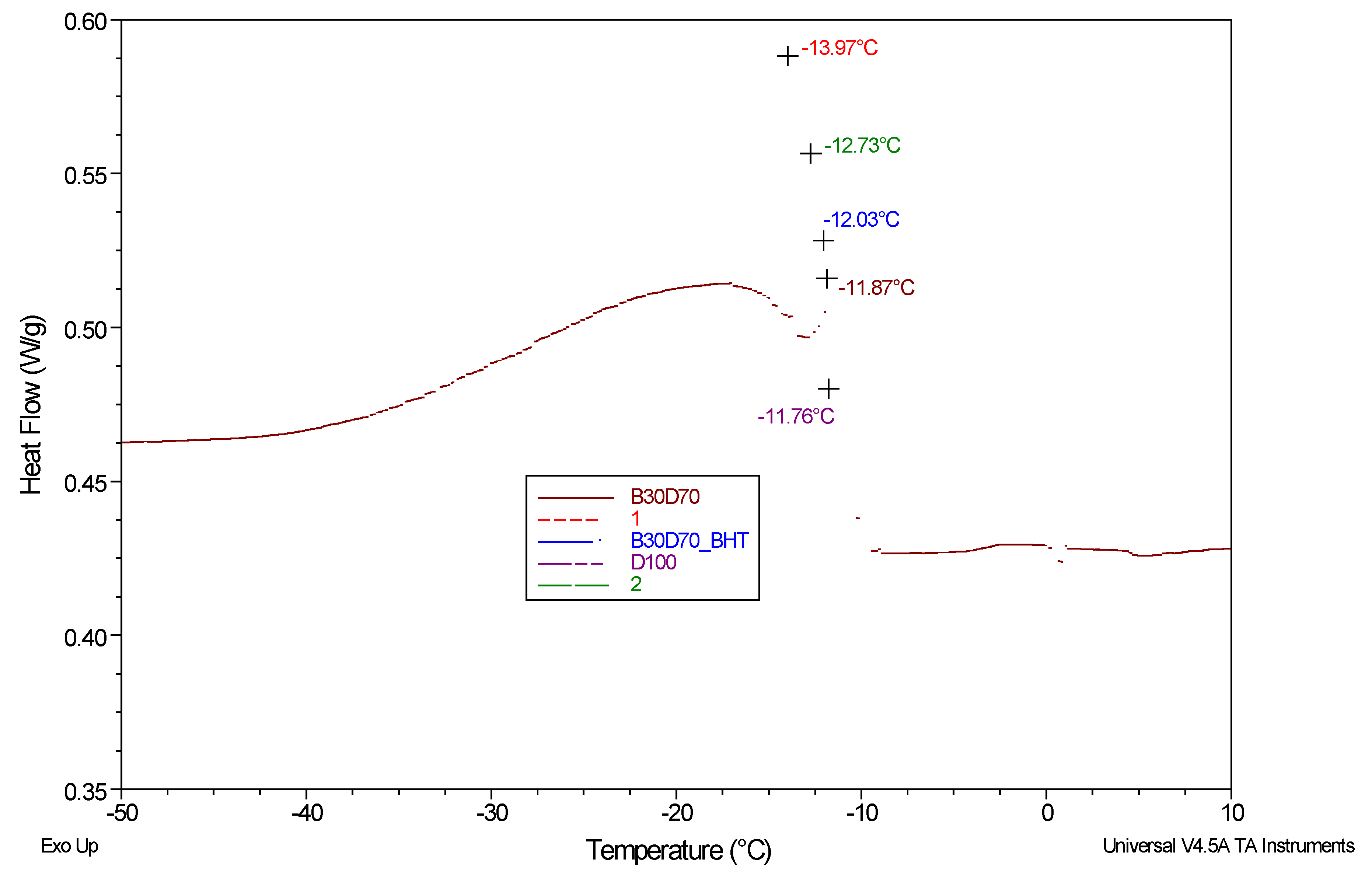

3.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments were performed on a fuel blend consisting of synthetic Schiff base derivatives, unbleached fuel, and diesel in a nitrogen gas environment. The experiment results are shown in

Figure 4, and the crystallization start temperatures (°C) for D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_

2, and B30D70_

1 are displayed in

Table 5. The mean onset temperature for crystallization is determined to be x_mean = 12.47. Equation (5) determines that the standard deviation, a fundamental measure for assessing experimental data variability, is 0.92. As shown in

Table 5.

The objective of this study was to investigate the impact of incorporating Schiff base derivatives into biodiesel-diesel blends on their crystallization temperatures. The study revealed that the extract obtained from the Schiff base exhibited an elevation in the crystallization point. The present inquiry pertains to the initiation temperatures of crystallization for a selection of specific alloys, namely D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1. Following the completion of experiments, the initial temperatures for crystallization were determined to be -11.76 °C, -11.87 °C, -12.03 °C, -12.73 °C, and -13.97 °C for the samples labeled as D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1, correspondingly.

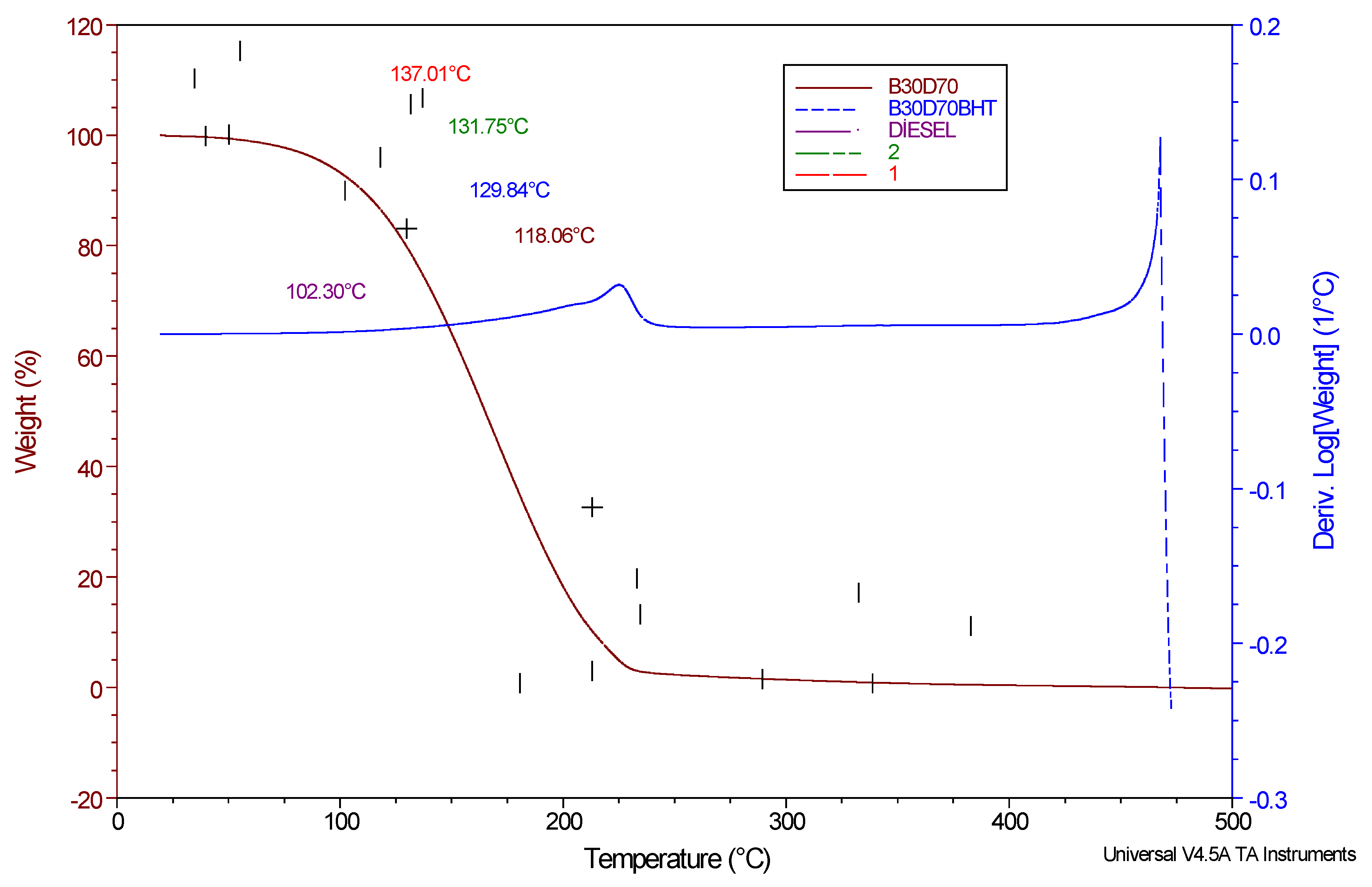

3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

TGA has significant importance in a wide range of sample examinations. The aforementioned techniques entail subjecting the samples to controlled heating while concurrently measuring the reduction in weight as a function of temperature. The TGA-DTG graphs of various combinations were compared. It has been observed that there is a singular degree of degradation in relation to temperature. The temperature at which degradation initiates, referred to as the onset temperature, provides valuable insights into the thermal stability and initial boiling point. A correlation has been observed between the stability of the samples and the Tonset values, indicating that an increase in sample stability is accompanied by a corresponding increase in Tonset values [

31].

Figure 5 presents the graphical depictions of the TGA and DrTGA curves. Upon further examination, it is evident that the curves exhibit a significant degree of similarity to each other. Under the specified temperatures, a variation in sample mass loss is observed, ranging from 98.09% to 99.44%. The recorded values obtained from the thermometers and documented on the thermograms are listed in

Table 6. The average degradation temperature (Tonset) is y_mean= 123.79, with a standard deviation of s = 13.86. The average mass loss is 98.87 with a standard deviation of 0.63, as calculated using Equation (5). As indicated in

Table 6.

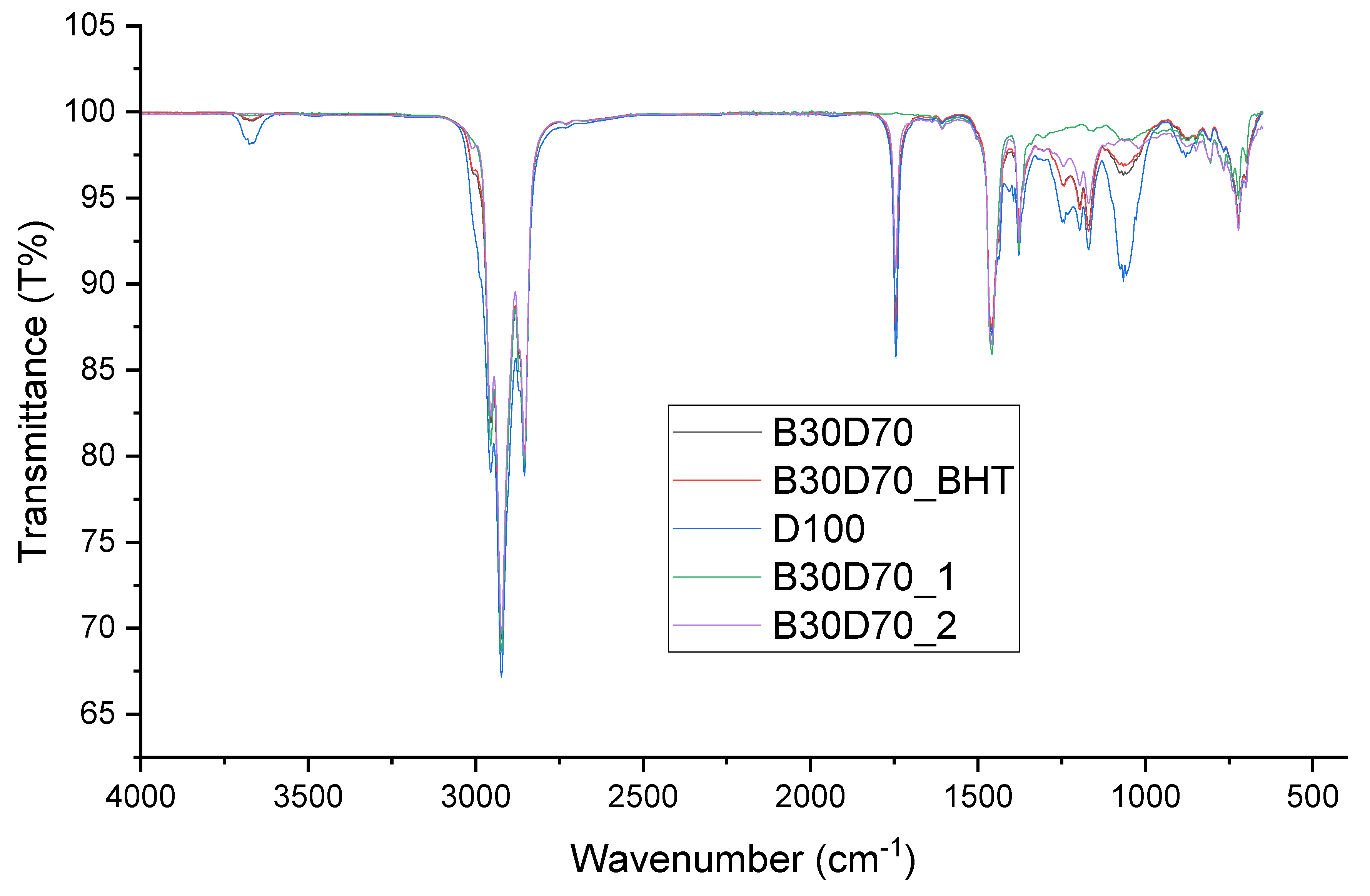

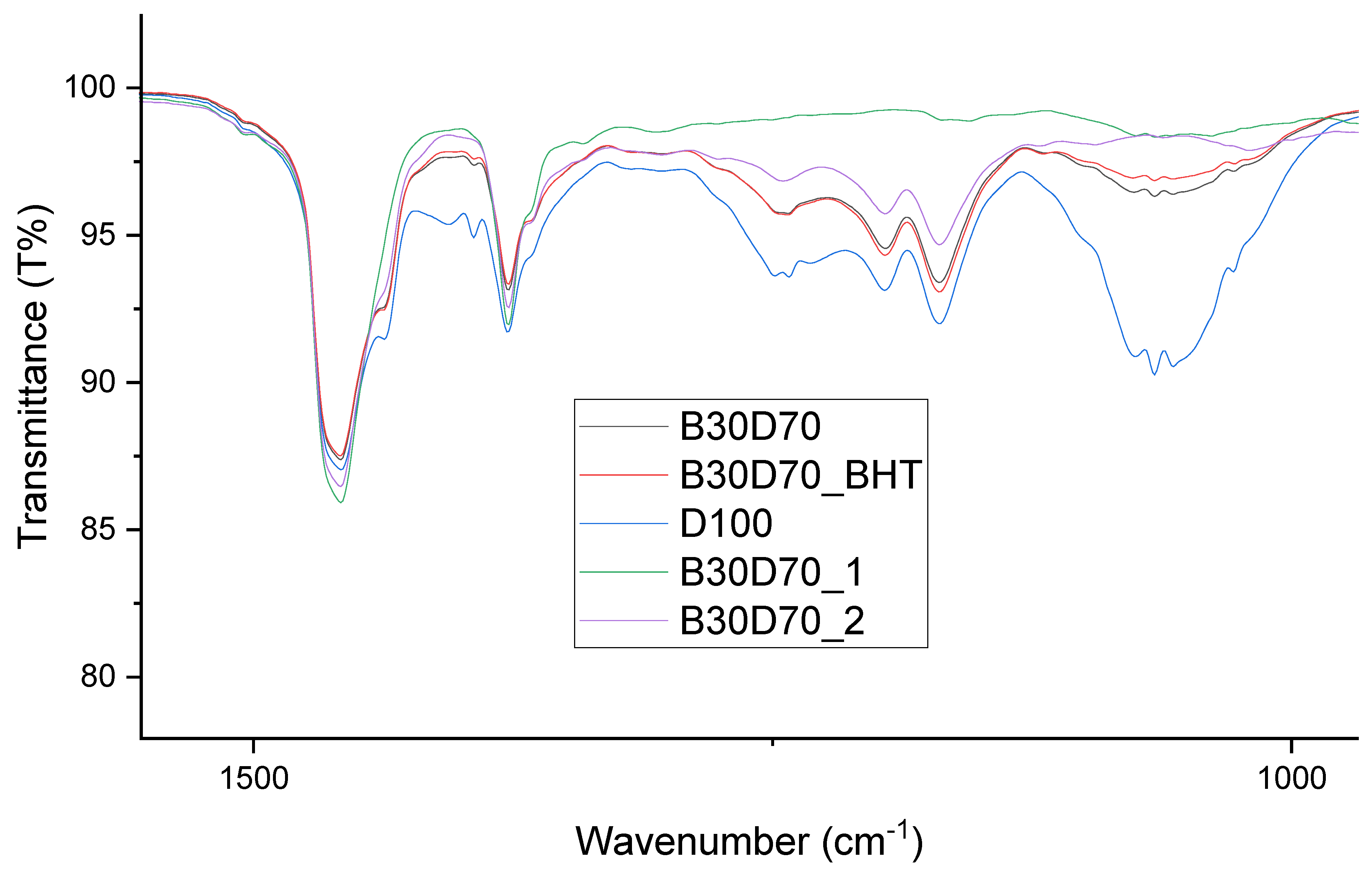

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 depict the FT-IR spectra of the blends, including biodiesel and diesel. These blends were created by introducing different amounts of antioxidants into the biodiesel-diesel samples. The effects of adding antioxidants to biodiesel samples at a concentration of 3000 ppm are presented in

Table 7. It has been found that the valence-stretching vibration frequency range of an unbounded hydroxyl group, which is written as ν(O−H), is around 3680–3685 cm

-1. The spectral peaks observed in the range of 2990−3000 cm

-1 are frequently linked to the vibrational stretching of ν(C−H) bonds, which serves as an indication of the oxidation process. These bonds are present in aldehyde and ketone compounds found in the antioxidants present in the biodiesel samples. The spectral range of 2920−2990 cm

-1 is frequently associated with the ν(C−H) bending vibration, a phenomenon that has been observed to play a role in oxidation processes. The peaks observed in the wavenumber range of 1065−1070 cm

-1 can be attributed to the stretching of the ν(C−O) bond. The comprehensive spectrum exhibits large absorption bands that are indicative of the significant ester carbonyl functional group ν(C=O). The observed absorption occurs within the spectral region of 1050−1755 cm

-1. Therefore, the absence of a proximate band might be interpreted as an indicator of the nonexistence of carboxylic acids. The observed vibrational modes within the wavenumber range of 1450−1460 cm

-1 and 1150−1184 cm

-1 can be ascribed to the bending vibrations of ν(N−H) and ν(C−N) bonds, respectively, within the framework of Schiff base compounds. The observed durability of the biodiesel samples can be attributable to the consistently low levels of oxidation seen in all samples [

33]. Numerous studies have provided evidence indicating that the incorporation of antioxidants results in heightened peak intensity, a phenomenon mostly attributable to the existence of phenolic chemicals [

46,

52].

3.4. Evaluation of Antioxidant Activity

3.4.1. DPPH. Free Radical Scavenger Effect for Schiff Bases

The free radical removal activities of the samples were assessed, and it was observed that compound 1 (28.08 ± 0.98b μM) exhibited higher activity, whereas composite 2 (33.77 ± 0.82b μM) displayed lower activity. Compound 1 is characterized by its ability to effectively remove free radicals, similar to the standard antioxidant substance BHT, making it highly active in free radical removal. The samples exhibited noteworthy free radical scavenging capabilities due to their comparable IC50 values. Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the observed behavior of the sample closely paralleled that of BHT, which might be seen as a good indicator.

3.4.2. ABTS•+ Radical Cation Scavenger Effect for Schiff Bases

The radical cation scavenging capabilities of the compounds were evaluated, revealing that Compounds

1 and

2 exhibited greater radical scavenging activity compared to BHT. When comparing compounds

1 and

2, it was observed that compound

1 shown higher activity with a concentration of 18.80 ± 0.65 μM, whereas compound

2 exhibited lesser activity with a concentration of 21.70 ± 0.70 μM. The DPPH

. free radical and ABTS

•+ radical cation scavenging activities of the compounds are presented in

Table 8.

4. Conclusions

Biodiesel has significance due to its ecologically sustainable attributes and cost-effectiveness as an alternative to conventional fossil derived diesel fuel. The outcomes of our research aimed at mitigating the inherent instability of biodiesel resulting from its heightened susceptibility to oxidation are outlined as follows:

The results of the DSC are as follows: The utilization of both natural and synthetic antioxidants has been found to result in a notable increase in the crystallization temperature (Tc). Through the examination of multiple samples, it was determined that the crystallization temperatures exhibited a range spanning from -11.76 °C to -13.97 °C. Notably, lower temperatures were indicative of a higher degree of purity within the samples under investigation. The initiation of crystallization was determined by measuring the temperatures at which this process commenced. In the study conducted, various samples were analyzed, and their corresponding temperatures were recorded. The sample labeled as D100 exhibited a temperature of -11.76 °C, while B30D70 displayed a slightly lower temperature of -11.87 °C. Furthermore, the sample B30D70BHT demonstrated a temperature of -12.03 °C, whereas B30D70_2 exhibited a slightly lower temperature of -12.73 °C. Lastly, the sample B30D70_1 displayed the lowest temperature among all the samples, measuring -13.97 °C. These findings provide valuable insights into the temperature characteristics of the different samples analyzed in this study. In the realm of crystallization, it has been observed that B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 exhibit lower crystallization tendencies compared to D100. This phenomenon can be attributed to the incorporation of antioxidants, which effectively enhance oxidation stability in a corresponding order. The aforementioned statement implies that the substance in question possesses the characteristics of early crystallization, rapid oxidation, and a heightened susceptibility to oxidation. Hence, it can be observed that the stability of the characteristic increases in the same sequential manner. The findings indicate that the introduction of Schiff base_1 resulted in an 87.78% rise in the crystallization point of the fuel blends, while the inclusion of Schiff base_2 led to a 72.16% increase in the crystallization point of the fuel blends.

The results of the TGA are as follows: TGA results revealed that the oxidative degradation temperature range for the D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 samples occurred within the range of 25–275 °C. This degradation process took place in a single continuous step. In the realm of thermal dynamics, it has been observed that during specific temperature ranges, the phenomenon of mass loss takes place. Recent studies have indicated that this occurrence transpires within the range of 98.09% to 99.44% for various samples under investigation. The curves exhibit remarkable similarities, however, with minor discrepancies in Tonset values observed among the biodiesel-diesel samples.

The FT-IR technique was employed to identify probable functional groups present in the samples. The biodiesel-diesel blends, namely B30D70_2 and B30D70_1, were found to have a decreased presence of functional groups as compared to other samples, such as B30D70BHT, due to the inclusion of 3000 ppm of Schiff bases. The discovery cited above suggests that the incorporation of Schiff bases into the composite has led to an enhancement in the oxidative stability of the mixture.

The compounds' in vitro antioxidant properties were determined by conducting tests using the DPPH. free radical and ABTS•+ radical cation scavenging activities. These tests utilized a spectrophotometric method and scavenging techniques. The IC50 values for the synthesized Schiff bases were found to be 28.08 ± 0.98 μg/mL and 33.77 ± 0.82 μg/mL, respectively, for the DPPH. free radical scavenging activity. The ABTS•+ radical cation scavenging activity was measured to be 18.80 ± 0.65 μg/mL and 21.70 ± 0.70 μg/mL, respectively. Out of the compounds that were evaluated, compound 1 showed the most favorable antioxidant activity based on the DPPH. free radical and ABTS•+ radical cation scavenging activity methods. As a result, molecules that contain electron-withdrawing groups typically exhibit higher antioxidant activity against BHT for DPPH. free radical and ABTS•+ radical cation scavenging activities, when compared to structures that have electron-donating groups. This suggests that a group of −NO2 molecules has a tendency to attract electrons. Additionally, a thorough investigation was carried out to analyze the relationships between the structure and activity of the compound. The investigation specifically focused on studying the presence and characteristics of substituents.

In order to minimize or eliminate the disadvantages of biodiesel, which is used more efficiently instead of fossil diesel fuel, the above mentioned Schiff bases, which are more advantageous than antioxidants added to biodiesel, were synthesized and used as antioxidants. As a result of the experiments and the data obtained, it was observed that the use of Schiff base as an antioxidant increased the oxidative stability of diesel aspirated biodiesel mixtures at all concentrations studied.

5. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Nalan Türköz Karakullukçu; Formal analysis, funding acquisition, validation, writing – review & editing, investigation, resources, supervision, project administration.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nayab, R.; Imran, M.; Ramzan, M.; Tariq, M.; Babar, M.; Nadeem, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Sustainable Biodiesel Production via Catalytic and Non-Catalytic Transesterification of Feedstock Materials – A Review. 2022, 328.

- Ennetta, R.; Soyhan, H.S.; Koyunoğlu, C.; Demir, V.G. Current Technologies and Future Trends for Biodiesel Production: A Review. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2022, 47, 15133–15151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, A.; Said, A.O. Solvent-Free Organic Reaction Techniques as an Approach for Green Chemistry. Journal of the Turkish Chemical Society, Section A: Chemistry 2023, 10, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Prasad, R. Triglycerides-Based Diesel Fuels. Renewable & sustainable energy reviews 2000, 4, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C.; Halliwell, B. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in the Year 2000. A Historical Look to the Future. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2000, 899, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, M.; Botella, L.; Arauzo, J.; Gonzalo, A.; Sánchez, J.L. Antioxidants for Biodiesel : Additives Prepared from Extracted Fractions of Bio-Oil. Fuel Processing Technology 2017, 156, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G. Some Aspects of Biodiesel Oxidative Stability ☆. 2007, 88, 669–677. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Singh, D. Biodiesel Production through the Use of Different Sources and Characterization of Oils and Their Esters as the Substitute of Diesel: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2010, 14, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinzadeh-bandbafha, H.; Kumar, D.; Singh, B.; Shahbeig, H. Biodiesel Antioxidants and Their Impact on the Behavior of Diesel Engines : A Comprehensive Review. Fuel Processing Technology 2022, 232, 107264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabani, A.E.; Silitonga, A.S.; Badruddin, I.A.; Mahlia, T.M.I.; Masjuki, H.H.; Mekhilef, S. A Comprehensive Review on Biodiesel as an Alternative Energy Resource and Its Characteristics. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 2070–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddikeri, G.L.; Pandit, A.B.; Gogate, P.R. Ultrasound Assisted Interesterification of Waste Cooking Oil and Methyl Acetate for Biodiesel and Triacetin Production. Fuel Processing Technology 2013, 116, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, A.; Saqib, S.; Lin, H.; Hassan Shah, M.U.; Ullah, S.; Younas, M.; Rezakazemi, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Mahmood, A.; Asif, S.; et al. Current Status and Challenges in the Heterogeneous Catalysis for Biodiesel Production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2022, 157, 112012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FERİÇOK, G.; KOÇ, Z.E. Schiff Bazı Ligand Kompleks Bileşiğinin Sentezi ve Multinükleer Fe(III)/Fe(II)/Fe(III) Geçiş Metal Kompleksinin İncelenmesi. Selçuk Üniversitesi Fen Fakültesi Fen Dergisi 2019, 45, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkınalı, S.; Yavuz, Ş.; Tosun, T.; Köse, D.A.; Gür, M.; Kocaokutgen, H. Synthesis, Spectroscopic and Thermal Analysis and Investigation of Dyeing Properties of o-Hydroxy Schiff Bases and Their Metal Complexes. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12624–12634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturk, A. pd. File:///C:/Users/mehme/OneDrive/Masaüstü/Semiha/a_2.pdf; File:///C:/Users/mehme/OneDrive/Masaüstü/Semiha/a_4.pdf; e Gediz Synthesis, Structural Identifications of Bioactive Two Novel Schiff Bases. Journal of Molecular Structure 2020, 1202, 127299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunil, D.; Isloor, A.M.; Shetty, P.; Nayak, P.G.; Pai, K.S.R. In Vivo Anticancer and Histopathology Studies of Schiff Bases on Ehrlich Ascitic Carcinoma Cells. 1st Cancer Update. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2013, 6, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, A.; al-Rashida, M.; Uroos, M.; Abid Ali, S.; Khan, K.M. Schiff Bases in Medicinal Chemistry: A Patent Review (2010-2015). Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2017, 27, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakan, H. Preparation, Structure Elucidation, and Antioxidant Activity of New Bis(Thiosemicarbazone) Derivatives. Turkish Journal of Chemistry 2020, 44, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakan, H.; Omer, H.H.S.; Buruk, O.; Çakmak, Ş.; Marah, S.; Veyisoğlu, A.; Muğlu, H.; Ozen, T.; Kütük, H. Synthesis, Structure Elucidation, Biological Activity, Enzyme Inhibition and Molecular Docking Studies of New Schiff Bases Based on 5-Nitroisatin-Thiocarbohydrazone. Journal of Molecular Structure 2023, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, E.M.M.; Abdel-Rahman, L.H.; Abu-Dief, A.M.; Elshafaie, A.; Hamdan, S.K.; Ahmed, A.M. Electric, Thermoelectric and Magnetic Characterization of γ-Fe2O3 and Co3O4 Nanoparticles Synthesized by Facile Thermal Decomposition of Metal-Schiff Base Complexes. Materials Research Bulletin 2018, 99, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, C.M.; Da Silva, D.L.; Modolo, L.V.; Alves, R.B.; De Resende, M.A.; Martins, C.V.B.; De Fátima, Â. Schiff Bases: A Short Review of Their Antimicrobial Activities. Journal of Advanced Research 2011, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- More, M.S.; Joshi, P.G.; Mishra, Y.K.; Khanna, P.K. Metal Complexes Driven from Schiff Bases and Semicarbazones for Biomedical and Allied Applications: A Review. Materials Today Chemistry 2019, 14, 100195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehye, W.A.; Rahman, N.A.; Ariffin, A.; Abd Hamid, S.B.; Alhadi, A.A.; Kadir, F.A.; Yaeghoobi, M. Understanding the Chemistry behind the Antioxidant Activities of Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT): A Review. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2015, 101, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, Z.; Đorović, J.; Petrović, Z.D.; Petrović, V.P.; Simijonović, D. Investigation of the Antioxidant and Radical Scavenging Activities of Some Phenolic Schiff Bases with Different Free Radicals. Journal of Molecular Modeling 2015, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, Z. Study of the Mechanisms of Antioxidative Action of Different Antioxidants. Journal of the Serbian Society for Computational Mechanics 2016, 10, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueke-Eze, C.U.; Fasina, T.M.; Oluwalana, A.E.; Familoni, O.B.; Mphalele, J.M.; Onubuogu, C. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Copper and Cobalt Complexes of (5-Substituted-Salicylidene) Isonicotinichydrazide Derivatives as Antitubercular Agents. Scientific African 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Farwa, U.; Ashraf, A.; Berrin POYRAZ, E.; Yesilbag, S.; Agar, E.; Al-Sehemi, A.G. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, Spectroscopic and Computational Investigations of the Newly Synthesized Schiff Bases Scaffold as Enzyme Inhibitor. Spectrochimica Acta - Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2023, 299, 122864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.S.; Johnson, E.R.; DiLabio, G.A. Predicting the Activity of Phenolic Antioxidants: Theoretical Method, Analysis of Substituent Effects, and Application to Major Families of Antioxidants. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2001, 123, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakhtshah, J. A Comprehensive Review on the Synthesis, Characterization, and Catalytic Application of Transition-Metal Schiff-Base Complexes Immobilized on Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2022, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakan, H. Novel Schiff Bases Derived from Isothiocyanates: Synthesis, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activity. Research on Chemical Intermediates 2020, 46, 3979–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice-Evans, C. Plant Polyphenols: Free Radical Scavengers or Chain-Breaking Antioxidants? Biochemical Society symposium 1995, 61, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Singhal, S.; Singh, M.; Arora, S.; Tanwer, M. Role of Antioxidants in Enhancing Oxidation Stability of Biodiesels. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Johnson, W.J.; Sevilla, C.L.; Herrington, J.W.; Sevilla, M.D. An Electron Spin Resonance Study of the Reactions of Lipid Peroxyl Radicals with Antioxidants. Journal of Physical Chemistry 1990, 94, 7185–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrović, Z.D.; Orović, J.; Simijonović, D.; Petrović, V.P.; Marković, Z. Experimental and Theoretical Study of Antioxidative Properties of Some Salicylaldehyde and Vanillic Schiff Bases. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 24094–24100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amić, A.; Marković, Z.; Marković, J.M.D.; Jeremić, S.; Lučić, B.; Amić, D. Free Radical Scavenging and COX-2 Inhibition by Simple Colon Metabolites of Polyphenols: A Theoretical Approach. Computational Biology and Chemistry 2016, 65, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamid, A.A.; Shah, Z.M.; Muse, R.; Mohamed, S. Characterisation of Antioxidative Activities of Various Extracts of Centella Asiatica (L) Urban. Food Chemistry 2002, 77, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Gan, S.; Lik, H.; Lau, N.; Yee, L. Insights into the Effectiveness of Synthetic and Natural Additives in Improving Biodiesel Oxidation Stability. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 52, 102296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhi, V.; Gupta, V.; Sharma, K.; Bhatnagar, S.; Kumari, R.; Dhaka, N. Potential Applications of Antioxidants – A Review. Journal of Pharmacy Research 2013, 7, 828–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanigan, R.S.; Yamarik, T.A.; Andersen, F.A. Final Report on the Safety Assessment of BHT; 2002; Vol. 21; ISBN 1091581029.

- Harald Küppers DuMonts Farben-Atlas. Über 5500 Farbnuancen Mit Kennzeichnung Und Mischanleitung; DuMont Reiseverlag, Ed.; Ostfildern, 1978. ISBN 9783770110582.

- Uğuz, G.; Çakmak, A.; Bento, C. da S.; Türköz Karakullukçu, N. Experimental Investigation of Fuel Properties and Engine Operation with Natural and Synthetic Antioxidants Added to Biodiesel. Biofuels 2023, 14, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Perez, M.; Adams, T.T.; Goodrum, J.W.; Das, K.C.; Geller, D.P. DSC Studies to Evaluate the Impact of Bio-Oil on Cold Flow Properties and Oxidation Stability of Bio-Diesel. Bioresource Technology 2010, 101, 6219–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Access, O.; Achparaki, M.; Thessalonikeos, E.; Tsoukali, H.; Mastrogianni, O.; Zaggelidou, E.; Chatzinikolaou, F.; Vasilliades, N.; Raikos, N.; Isabirye, M.; et al. We Are IntechOpen, the World ’ s Leading Publisher of Open Access Books Built by Scientists, for Scientists TOP 1 %. Intech 2012, i, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, S.T.; Hamad, K.I.; Gheni, S.A.; Aqar, D.Y.; Ahmed, S.M.R.; Mahmood, M.A.; Ceylan, S.; Abdullah, G.H. Enhancement of Stability of Pd/AC Deoxygenation Catalyst for Hydrothermal Production of Green Diesel Fuel from Waste Cooking Oil. Chemical Engineering Science 2022, 251, 117489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabani, A.E.; Al-Rubaye, O.K. Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds for Biodiesel Production: Blending with Higher Alcohols, FT-IR, TGA, DSC, and NMR Characterizations. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022, 12, 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Company, C. Diesel Fuels Technical Review. 1998, FTR-2, 1–70.

- Ozdemir, O.; Gurkan, P.; Simay Demir, Y.D.; Ark, M. Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activity Studies in Series of Higher Amino Acid Schiff Bases. Gazi University Journal of Science 2020, 33, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.; Chapman, V. © 1958 Nature Publishing Group. 1958.

- Frankel, E.N.; Meyer, A.S. The Problems of Using One-Dimensional Methods to Evaluate Multifunctional Food and Biological Antioxidants. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2000, 80, 1925–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechayont, B.; Ruamdee, P.; Poonnaimuang, S.; Mokmued, K.; Chunthorng-Orn, J. Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities of Pogostemon Cablin (Blanco) Benth. Journal of Botany 2017, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçimen, S.Ş.; İpek, Y.; Behçet, L.; Demirtaş, İ.; Özen, T. Isolation, Characterization and Evaluation of Oxypeucedanin and Osthol from Local Endemic Prangos Aricakensis Behçet and Yapar Root as Antioxidant, Enzyme Inhibitory, Antibacterial and DNA Protection: Molecular Docking and DFT Approaches. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyerinde, A.; Bello, E. Use of Fourier Transformation Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy for Analysis of Functional Groups in Peanut Oil Biodiesel and Its Blends. British Journal of Applied Science & Technology 2016, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Chelate complex formation: metal ions and Schiff base ligands.

Figure 1.

Chelate complex formation: metal ions and Schiff base ligands.

Figure 2.

Stabilization of phenoxy radicals.

Figure 2.

Stabilization of phenoxy radicals.

Figure 3.

Schiff base structures and synthesis reaction.

Figure 3.

Schiff base structures and synthesis reaction.

Figure 4.

DSC thermograms of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 under N2 atmosphere.

Figure 4.

DSC thermograms of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 under N2 atmosphere.

Figure 5.

TGA and DrTGA curves of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 under O2 atmosphere.

Figure 5.

TGA and DrTGA curves of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 under O2 atmosphere.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 at 4000−500 cm-1.

Figure 6.

FT-IR spectra of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 at 4000−500 cm-1.

Figure 7.

FT-IR spectra of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 at 1500−1000 cm-1.

Figure 7.

FT-IR spectra of D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 at 1500−1000 cm-1.

Table 1.

The properties of BHT.

Table 1.

The properties of BHT.

| Property |

Butyl hydroxytoluene (BHT) |

Chemical Structure |

| Molecular formula |

C15H24O |

|

| Molecular mass (g/mol) |

220.35 |

| Density (g/cm3) |

1.05 |

| Boiling temperature (°C) |

265 |

| Flash point temperature (°C) |

127 |

Table 2.

Properties of aspire oil methyl ester (AME).

Table 2.

Properties of aspire oil methyl ester (AME).

| Parameter (unit) |

Method |

Range |

Results |

| Density (15 °C) (kg/m3) |

TS EN ISO 12185 |

860–900 |

84.1 |

| Viscosity (40 °C) (m2·s−1) |

TS1451 EN ISO 3104 |

3.50–5.00 |

4.381 |

| Total Contamination (mg/kg) |

TS EN 12662 |

0–24 |

15.6 |

| Oxidation Stability (h) |

TS EN 14112 |

8-0 |

10.4 |

| Flash Point (°C) |

TS EN ISO 2719 |

101-0 |

166.0 |

| Cold Filter Plugg. Point (CFPP) (°C) |

TS EN 116 |

≤+5 |

-2 |

| Methanol (m/m%) |

TS EN 14110 |

≤0.20 |

0.02 |

| Water Content (%) |

TS 6147 EN ISO 12937 |

≤0.05 |

0.04 |

| Iodine Value (gl/100 g) |

TS EN 14111 |

≤120 |

111 |

| Free Glycerol (wt%) |

TS EN 14105 |

≤0.02 |

0.002 |

| Total Glycerol (wt%) |

TS EN 14105 |

≤0.25 |

0.154 |

| Ester Contents (m/m%) |

TS EN 14103 |

≥96.5 |

97.7 |

| Linolenic Acid Methyl Ester (m/m%) |

TS EN 14103 |

≤12 |

1.6 |

| Polyunsaturated Methyl Ester (m/m%) |

TS EN 14103 |

≤1 |

0.03 |

| Acid Number (mgKOH/g) |

TS EN 14104 |

≤0.50 |

0.36 |

| Copper Strip Corrosion 50 °C, 3h (°C) |

TS 2741 EN ISO 2160 |

Class1 |

Class1 |

| Cetane Number (°C) |

TS EN 15195 |

≤51.0 |

55.6 |

| Sulfated Ash (m/m%) |

TS ISO 3987 |

≤0.02 |

0.003 |

| Sulphur (mg/kg) |

TS EN ISO 20846 |

≤10 |

3.2 |

| Phosphorus (mg/kg) |

TS EN 14107 |

≤4 |

˂1.6 |

| Metals (Na, K) (mg/kg) |

TS EN 14538 |

≤5 |

˂1 |

| Metals (Ca, Mg) (mg/kg) |

TS EN 14538 |

≤5 |

˂1 |

| Monogliserit Content (wt%) |

TS EN 14105 |

≤0.7 |

0.50 |

| Digliserit Content (wt%) |

TS EN 14105 |

≤0.2 |

0.12 |

| Trigliserit Content (wt%) |

TS EN 14105 |

≤0.2 |

0.06 |

Table 3.

Elemental analysis results and physical data of the Schiff bases.

Table 3.

Elemental analysis results and physical data of the Schiff bases.

| Compound |

R group |

Molecular formula |

Molecular weight (g/mol) |

Melting point

(°C) |

Colour and

colour code [40] |

Yield% |

Elemental analysis |

| Calculated |

Experimental |

| C% |

H% |

N% |

O% |

C% |

H% |

N% |

O% |

| 1 |

-NO2

|

C13H10N2O4

|

258.23 |

180.1-181.4 |

Light Brown

S70O26G33 |

82 |

60.47 |

3.90 |

10.85 |

24.78 |

60.18 |

3.20 |

10.32 |

26.30 |

| 2 |

-CH3

|

C14H13NO2

|

227.26 |

158.1-159.6 |

Brown

S90O11G20 |

87 |

73.99 |

5.77 |

6.16 |

14.08 |

73.33 |

5.60 |

6.00 |

15.07 |

Table 4.

Biodiesel diesel antioxidant Schiff base ligand blends: exploring contents and codes.

Table 4.

Biodiesel diesel antioxidant Schiff base ligand blends: exploring contents and codes.

| Sample |

Biodiesel (%) |

Diesel (%) |

| D100 |

- |

100 |

| B30D70 |

30 |

70 |

| B30D70BHT |

30 |

70 |

| B30D70_2 |

30 |

70 |

| B30D70_1 |

30 |

70 |

Table 5.

D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 crystallization onset temperatures (°C) in a N2 atmosphere*.

Table 5.

D100, B30D70, B30D70BHT, B30D70_2, and B30D70_1 crystallization onset temperatures (°C) in a N2 atmosphere*.

| Sample |

(℃) |

|

| D100 |

-11.76 |

0.71 |

| B30D70 |

-11.87 |

0.60 |

| B30D70BHT |

-12.03 |

0.44 |

| B30D70_2 |

-12.73 |

0.26 |

| B30D70_1 |

-13.97 |

1.5 |

Table 6.

TGA values of samples.

Table 6.

TGA values of samples.

| Sample name |

Temperature range (°C) |

(°C)

(Tonset) |

|

(%) |

|

| D100 |

25-275.00 |

102.30 |

21.49 |

99.44 |

0.566 |

| B30D70 |

25-275.00 |

118.06 |

5.73 |

98.30 |

0.574 |

| B30D70BHT |

25-275.00 |

129.84 |

6.05 |

99.34 |

0.466 |

| B30D70_2 |

25-275.00 |

131.75 |

7.96 |

99.20 |

0.326 |

| B30D70_1 |

25-275.00 |

137.01 |

13.22 |

98.09 |

0.784 |

Table 7.

Experimental FT-IR values of the compounds (cm−1).

Table 7.

Experimental FT-IR values of the compounds (cm−1).

| Compound |

ν(O−H) |

ν(C−H)

Aromatic |

ν(C−H)

Aliphatic |

ν(C=O) |

ν(N−H) |

ν(C−N) |

ν(C−O) |

| B30D70_1 |

– |

3000 |

2990 |

1755 |

1450 |

1150 |

1067 |

| B30D70_2 |

– |

2995 |

2920 |

1750 |

1460 |

1184 |

1065 |

| B30D70 |

3680 |

2990 |

2950 |

1650 |

– |

– |

1069 |

| B30D70BHT |

3882 |

2996 |

2965 |

1680 |

– |

– |

1069 |

| D100 |

3685 |

2990 |

2945 |

1650 |

– |

– |

1070 |

Table 8.

DPPH. free radical and ABTS•+ radical cation scavenging activities of compounds (μM)*.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).