Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Question

- RQ1: How can LLMs and RAG be leveraged to enhance the current automation in Cyber Incident Timeline Analysis ?

- RQ2: How can a framework driven by RAG and LLMs advance incident timeline analysis by seamlessly integrating artefact analysis and event correlation ?

- RQ3: How can the framework be optimised to produce a reliable, comprehensive, and semantically-rich timeline for DFIR investigations ?

- RQ4: Is Timeline Analysis truly ready for Generative AI automation?

1.2. Novelty and Contribution

2. Research Background and Related Works

2.1. Timeline Analysis in DFIR

- DF: involves the management and analysis of digital evidence from its initial discovery to its presentation in legal contexts. This process includes the identification, collection, and analysis of evidence, with a key component being timeline analysis. Timeline analysis is essential in DF as it helps reconstruct the sequence of events by establishing the chronological order of actions, which is crucial for uncovering critical details and understanding the flow of the incident.

- IR: On the other hand, refers to the set of actions and procedures an organisation follows to detect, manage, and mitigate cyber incidents. It typically starts with preparation, followed by detection, where timeline analysis also plays a role in understanding the sequence of events and determining the scope of the incident. During the analysis phase, establishing a chronological order of actions helps assess how the incident progressed. The process continues with containment, eradication, recovery, and post-incident activities, where insights from timeline analysis can guide decisions and help evaluate the effectiveness of the response.

2.2. Large Language Models

- Prompt Engineering: is the art and science of skillfully crafting and designing prompts to maximise the capabilities of a model. In the context of timeline analysis, this involves strategically framing inputs, specifying technical details, and establishing the investigative context to refine the model’s output based on its precise and meaningful definition [20]. For example, a DFIR analyst might prompt the system as follows: "Conduct artefact analysis, correlate events, and reconstruct a coherent timeline of the incident.". This method aims to ensure that the LLM understands the context, adheres to specific DFIR timeline analysis constraints, and achieves the intended goals of the investigation and analysis.

- Token: In LLMs, a token represents a character, word, subword, symbol, or number [20]. However, in timeline analysis, a token can be represented as follows:

- Embedding: is the process of converting text into numerical representations, often in the form of tensors, suitable for the LLM. It begins with tokenisation, where words or characters within a text are transformed into tokens, representing individual units. These tokens are then mapped to numerical values that capture their semantic representation. Subsequently, additional layer transformations and processing are applied to refine these representations further. The final output is a dense vector, where each value corresponds to a specific feature of the text [39].

2.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) in Information Extraction and Knowledge Expansion

-

Retrieval-Augmented: In the context of RAG, retrieval refers to the process of searching and selecting relevant information from a knowledge base or document dataset to enhance the output of a generative model. This ensures the model generates more accurate and contextually relevant responses [49]. Retrieval techniques commonly used in information retrieval include cosine similarity, Jaccard similarity, BM25, TF-IDF, Latent Semantic Analysis (LSA), and embedding-based models. These methods evaluate the similarity between the query and documents, retrieving the top k pieces with the highest similarity scores to provide relevant contextual knowledge for the LLM [50].In GenDFIR, retrieval is applied to extract relevant incident events from documents containing cyber incident events. It helps identify and select the most pertinent ones (Top k pieces) based on their relevance to the query or event context.

- Augmented Generation: Is the process where, after retrieval, the extracted information is provided to the LLM for semantic enhancement, enabling it to generate more accurate and contextually enriched outputs [49]. In the case of GenDFIR, this involves extracting evidence (mostly anomalous events) from the incident knowledge base and passing it to the LLM to produce a timeline of the incident, which includes key events, correlations, and analysis of the evidence.

- Token-Based: Divides text based on a fixed number of tokens.

- Paragraph-Based: Segments text by paragraphs to maintain context.

- Semantic-Based: Groups text based on meaning or topics.

- Sentence-Based: Segments text into sentences, each of which may have unique semantics.

3. Research Methodology

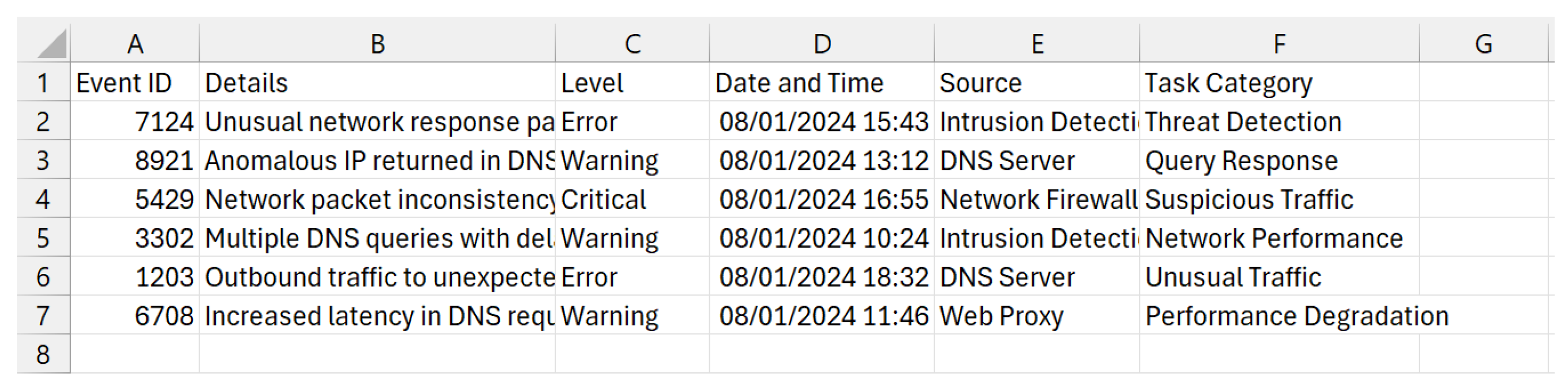

3.1. Incident Events Preprocessing and Structuring:

- The collected events refer to those that occurred during the timeframe of the cyber incident.

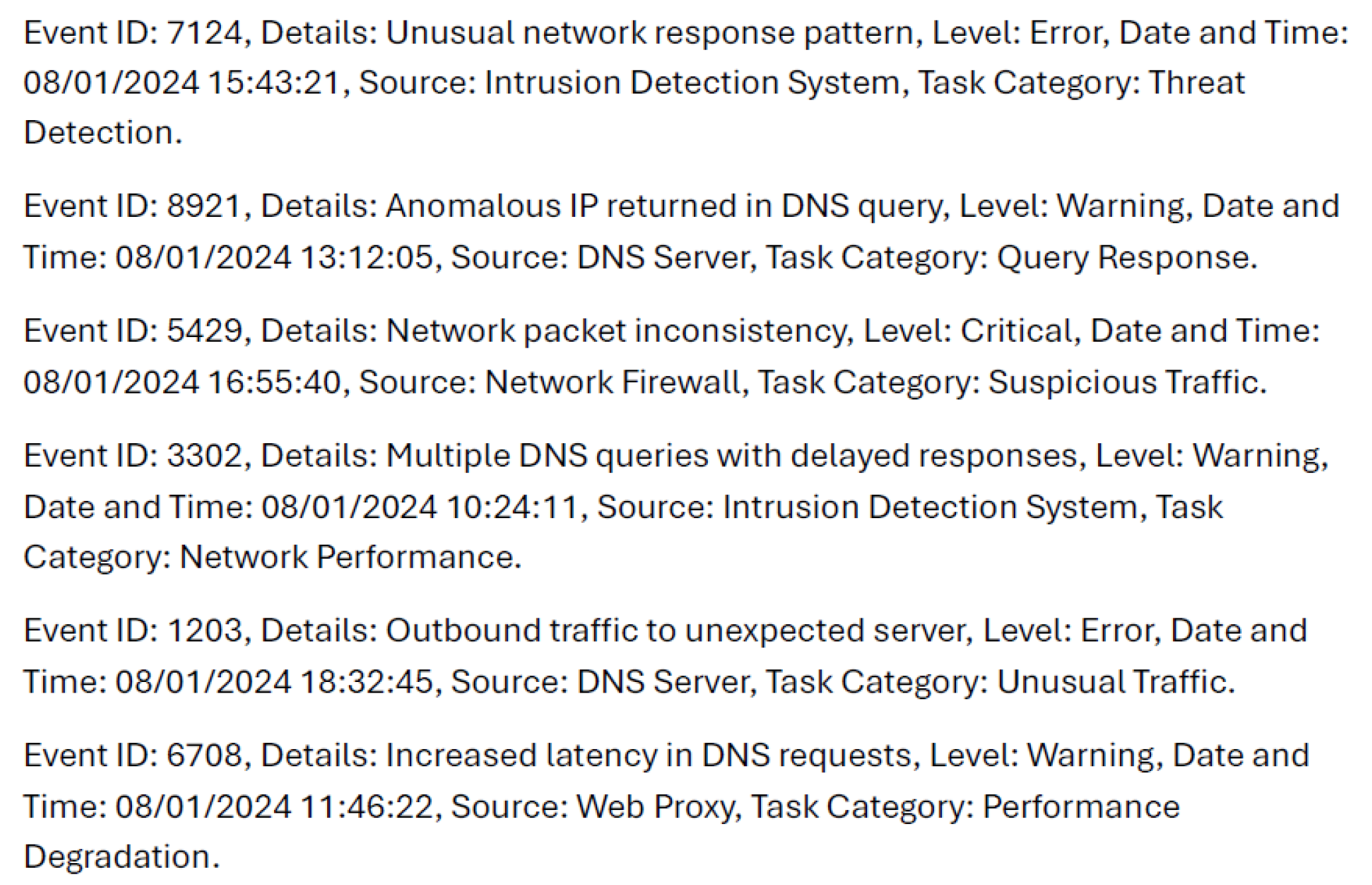

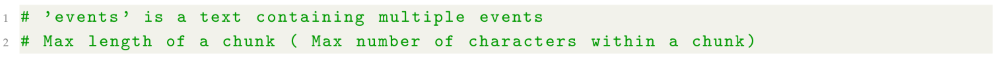

3.2. Incident Events Chunking

-

Cyber Incident Event Length: The length of an event is defined as the total sum of the number of characters across its attributes. The characters in a line of events are counted based on their attributes, , where:

- i represents the event number (e.g., Event 1, Event 2), and

- j represents the attribute number within that event (e.g., Event ID, Level).

The total number of characters in the i-th event is given as follows:- is the total number of characters in the i-th event.

- is the number of characters in the j-th attribute of the i-th event.

- n is the total number of attributes in the i-th event.

-

Events Chunking: The proposed method extends the general chunking concept by incorporating the calculated lengths of individual events. It enhances retrieval precision through precise semantic embedding, as every event attribute contributes to the chunking process, improving the accuracy of retrieval tasks. The chunking process adheres to the following equations to ensure compliance with both the token capacity of the LLM and the adopted embedding model:To calculate the number of tokens for an event or chunk, we consider the token capacity of the embedding model, for instance, models that can process up to 512 tokens per input.For optimisation, we assume an average of 4 characters per token, which is within the standard range of 4 to 6 characters in English, with 4 selected to maximise token capture and improve input accuracy. Based on this, the number of tokens for an event is approximately the total number of characters in the event , divided by the average of characters per token. This relationship is expressed by the Equation 2:

- i represents the index of the i-th event in the sequence.

Similarly, the number of tokens for a chunk is calculated in the same manner, as in Equation 3:- k represents the index of the k-th chunk in the sequence.

This equation follows the same principle as equation 2 but applies to a chunk (a chunk represents a single event ). is the total number of characters in a chunk.The constraint on the number of tokens in a chunk is introduced in Equation 4. It ensures that the number of tokens for any chunk does not exceed the model’s token capacity :- represents the model’s maximum token capacity, such as 512 tokens.

This helps ensure that a chunk fits within the embedding model’s processing limits.- represents the maximum number of characters that the model can embed per chunk.

We define a cyber incident in a document as the sum of all chunks , where each chunk corresponds to an event :

- n is the total number of chunks.

- i represents the index of the i-th event in the incident.

- j represents the index of the j-th character in the i -th event.

- is the maximum or total number of characters that can be processed in the i-th event. With :

- represents the greatest number of characters found in any single event within the incident, ensuring that the maximum event length is selected as the standard size of a chunk.

- If a chunk does not reach the limit, it is padded and adjusted to this limit.

- represents the total length of the incident, calculated as the sum of the lengths of each event or chunk .

- t represents the total number of events or chunks in the incident. This total length determines how many tokens will be used to process the entire incident, ensuring that the chunking and tokenisation process adheres to the embedding model’s constraint.

| Listing 1. Chunking code snippet |

|

3.3. Incident Events and DFIR Query Embedding

-

Events: Following the chunking process, this step focuses on embedding the chunks into high-dimensional vector representations. An embedding model is adopted to transform each chunk or event into a dense vector, which captures its semantic meaning and enables efficient similarity search and analysis. The first step involves passing an individual event through the embedding model, which first tokenises the event (i.e., splits it into tokens such as words or subwords) and then generates its vector .

- The event consists of several attributes , where each attribute represents a specific aspect or detail of the event (such as the date, description, etc.).

- DFIR Query: The DFIR expert conducts automated timeline analysis by querying or instructing the framework. The query/instruction undergoes an embedding process similar to that of the event E. When the user inputs the query, it is first tokenised and then embedded, transforming it into a dense vector . The process is expressed as:

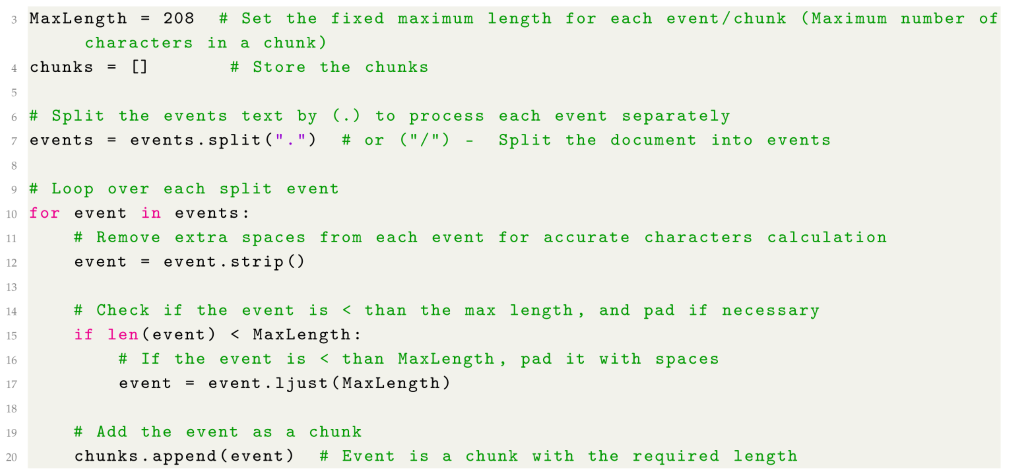

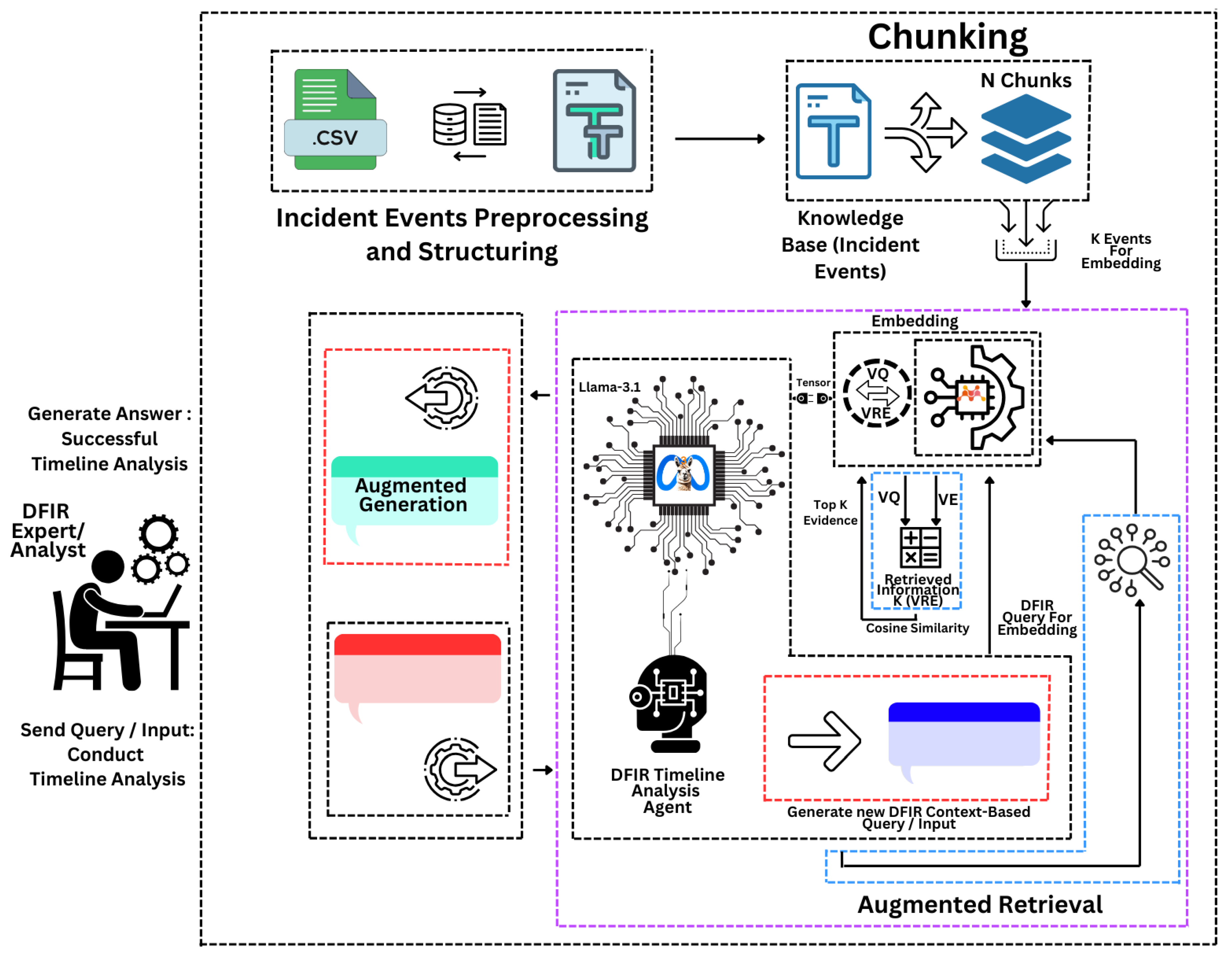

3.4. Context-Specific LLM-Powered RAG Agent for Timeline Analysis

-

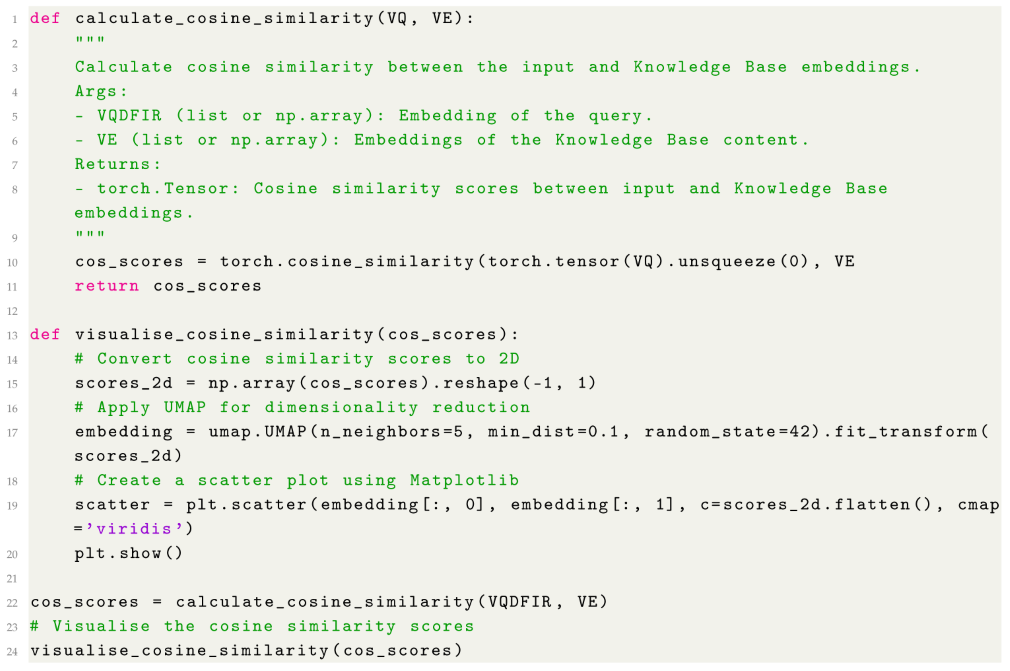

Events Retrieval: The retrieval phase is initiated when the DFIR expert provides a query related to an incident. The query is embedded into a vector , along with the vectors representing anomalous events stored in the external knowledge base . We represent the retrieval process of GenDFIR as:These embeddings allow the framework to semantically compare the input query with historical incident events. The similarity between the query vector and each event vector is computed using the cosine similarity function:

- is the dot product of the query and event vectors, quantifying their alignment in the vector space.

- and are the Euclidean norms (magnitudes) of the respective vectors.

The cosine similarity identifies how closely the query aligns with the context of each anomalous event. This computation forms the basis for selecting the most relevant events. To ensure efficiency, only the top-k events with the highest similarity scores are retrieved, as defined by:- represents the set of retrieved event vectors ranked by similarity scores. It plays a critical role in narrowing down the large pool of potential event to a focused subset of highly relevant anomalous events.

- t denotes the total number of events in the knowledge base .

- k is a hyperparameter that is defined and set manually based on the number of events within the knowledge base that are intended to be considered for analysis. The choice of k directly impacts the quality and completeness of the DFIR timeline analysis, while an optimally defined k equal to the exact number of events in the controlled knowledge base , ensures all evidence is included.

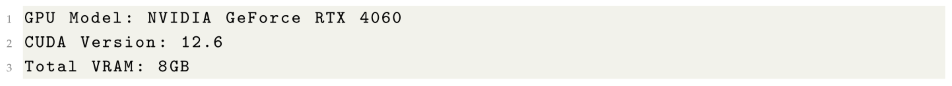

- DFIR Context-Specific Agent Workflow: Once the initial set of relevant events has been retrieved, the DFIR RAG agent focuses on further filtering and refining these results based on contextual relevance. During this phase, the agent focuses on identifying and filtering the most contextually relevant events, ensuring that irrelevant evidence is excluded according to its assigned task as shown in Listing 2.

| Listing 2. Code snippet for GenDFIR Agent Prompt and Role |

|

- is the matrix containing the embedding vectors of all events in the knowledge base .

- is the embedding vector of the query.

- k is the predefined number of top events to retrieve, equal to the number of events in the controlled knowledge base.

- 3.

-

Timeline Analysis Generation: In this phase, the framework utilises both the context provided by the retrieval process (Relevant Evidence ) and the user’s input to generate a timeline of anomalous events. The process involves multiple steps, including attention-based mechanisms, contextual enrichment by the LLM [56], and final timeline generation via a decoder-based LLM model.After retrieving the relevant evidence, the framework applies attention mechanisms. Attention scores are calculated between the query vector and the event vectors , allowing the model to weigh the relevance of each event. The attention score is computed as follows:

- d is the dimension of the vectors (the number of features in each vector),

- k is the number of the retrieved events.

This process amplifies the differences in similarity scores between events and the query, so events that are more similar to the query will have higher attention scores. This attention score is calculated using the dot product between and , followed by an exponential function. The exponential function serves two primary purposes in this context. First, it emphasises retrieved incident events that are more relevant to the query by assigning them higher attention scores, which helps these events contribute more to the final timeline generation. Second, it ensures that the difference between similarity scores is amplified in a controlled manner, preventing events with slightly lower similarity from being overshadowed or overlooked. This balance allows the model to consider both highly relevant events and those with smaller, yet still meaningful, similarity and relevance to .Once the attention score is calculated, the next step is to enrich the context of each event. The weighted sum of event vectors, adjusted by the attention scores, represents an initial context c for the events, reflecting their weighted relevance to the query :The LLM further enriches this context by processing the weighted sum of events c in light of its pre-existing training knowledge. For instance, Llama 3.1 has been extensively trained to recognise anomalous patterns, as well as publicly known cyber incident threats and anomalies. In this case, the context represents a nuanced, model-based interpretation of anomalous events, incorporating the LLM’s understanding of their significance based on patterns, relationships, and domain knowledge learned during training. This enriched context incorporates event correlation, where the LLM identifies and links related events based on temporal order, causality, or contextual associations.For example, failed login attempts in a cyber incident might signal unauthorised access. The LLM correlates this event with subsequent related activities, such as privilege escalation or data exfiltration attempts, tying them to the same threat source. By analysing timestamps, anomaly severity, and underlying causes, the LLM constructs a logically sequenced timeline of events, capturing the progression and full scope of the incident. Without such automation, resolving incidents would require significant time and expertise, particularly for analysing complex event relationships and uncovering causal links. This process often demands considerable manual effort from specialists with deep technical knowledge. In contrast, GenDFIR leverages the LLM’s extensive contextual understanding to accelerate and improve incident analysis, minimising reliance on manual intervention.The final enriched context , derived from the attention mechanism and LLM-based enrichment, is represented as a vectorised timeline . This step involves integrating relevant evidence and user inputs to generate a numerical representation of the incident’s timeline, as shown in Equation 18.The final enriched context , derived from the attention mechanism and LLM-based enrichment, is represented as a vectorised timeline . This step involves integrating relevant evidence and user inputs to generate the incident’s timeline, as shown in Equation 19.At this stage, has all relevant event information in a numerical form. It reflects the incident’s sequence, correlation, and anomaly patterns across multiple dimensions (e.g., event features, timestamps, anomaly levels).To make the timeline accessible and understandable to humans, must be decoded into a readable format. This is achieved by the decoder-based LLM model, which transforms the representation into a human-readable, logically structured timeline of events as in Equation 20:- Where denotes the model’s generated or predicted timeline, in a human-readable format, suitable for further analysis, interpretations and decision-making by Investigators or DFIR Experts.

| Algorithm 1:GenDFIR Core |

|

Input: DFIR Expert/Analyst Query or Instruction as input , Incident Knowledge Base

Output: Auto-Generated Timeline Analysis Report relevant to the incident

|

4. GenDFIR Implementation

-

Variability in DFIR Timeline Analysis Practices and GenDFIR: It is essential to recognise the diversity of methodologies and procedures within the DFIR industry. Each organisation or entity may adopt different investigative workflows and reporting formats, depending on the specific nature of the investigation. Broadly, DFIR processes can be divided into two primary domains: DF, which focuses on the preservation, collection, and analysis of digital evidence, and IR, which centres on the containment, eradication, and recovery from cyber incidents.Organisations vary in their approach to timeline analysis during investigations, as enterprise-focused IR differs from legal forensics in terms of the depth of analysis, objectives, and reporting. In enterprise environments, timeline analysis often prioritises speed and operational impact, emphasising the rapid identification of critical events and resolution steps, sometimes with less emphasis on maintaining a formal chain of custody. In contrast, legal forensic investigations place greater importance on the preservation and reconstruction of timelines, ensuring that all digital events are accurately sequenced and documented to meet evidentiary standards for potential legal proceedings.The reporting mechanisms for timeline analysis also differ. IR reports typically concentrate on delivering actionable insights—such as the timing of compromise, propagation, and remediation steps—often to guide immediate decision-making. These reports prioritise clarity and immediacy over legal formalities. In contrast, forensic timeline analysis reports must adhere to strict documentation standards, ensuring that every event is precisely tracked and presented in a manner that preserves the integrity of the investigation for legal scrutiny [2]. This involves rigorous validation of timestamps, metadata, and cross-referencing multiple data sources to reconstruct a legally defensible timeline of events.The GenDFIR framework is not a one-size-fits-all solution, as DFIR practices differ across organisations. The framework is designed as a flexible approach to integrate GenAI models into DFIR workflows, supporting experts in improving the efficiency of investigations. The framework focuses on tasks such as log analysis, anomaly detection, and rapid evidence identification, with the purpose of providing a context-rich timeline analysis to help DFIR experts make informed decisions more quickly.

-

Large Language Models in GenDFIR: The practical application of LLMs within DFIR tasks is still novel. Recent advancements in the use of LLMs across various fields have generated interest, but they are far from being fully reliable tools for DFIR investigations [59]. Several challenges must be acknowledged, including issues of hallucination, precision, and limitations related to input/output token lengths, which can restrict the model’s ability to process large datasets typical in DFIR cases.LLMs are powerful tools for automating certain aspects of data analysis, summarisation, and even generating incident reports. However, they are not yet capable of performing highly specialised forensic tasks without human oversight.

-

Data in GenDFIR: The LLM used in GenDFIR operates in a zero-shot mode, relying solely on its pre-existing training data to generate general-purpose DFIR Timeline Analysis reports. While this approach works for broad applications, it is insufficient for the specific and dynamic needs of DFIR, which requires real-time recognition and processing of incident-specific data. This is particularly important during the phase of enriching the context of incident events, where the effectiveness of enrichment and interpretation depends on the LLM’s pre-existing knowledge and its ability to process relevant data. Furthermore, each DFIR case involves unique and sensitive information, often shaped by regulatory frameworks, organisational policies, and legal requirements. As a result, incident data is highly diverse, reflecting variations in breach detection and response mechanisms.This diversity highlights a significant gap between generalised knowledge and the nuanced demands of DFIR. Bridging this gap requires moving beyond generic outputs, such as the Timeline Analysis report generated by GenDFIR, and integrating incident-specific data into the model. This can be achieved by training LLMs in secure, controlled environments using curated datasets derived from real-world incidents. Such an approach enables LLMs to adapt to the distinct characteristics of various DFIR scenarios, improving their ability to identify patterns and respond effectively across different contexts.However, the integration of real-world data into LLM training raises important privacy, legal, and ethical considerations. DFIR investigations often involve sensitive information, including personal data and proprietary organisational content. The use of incident-specific data must adhere to data protection laws, organisational consent policies, and robust security measures to safeguard against breaches during both model training and inference. These safeguards are critical to ensuring confidentiality while maximising the value of such data for future applications.Moreover, current LLMs face limitations in adapting to new or evolving threats outside their original training scope. Without regular updates and retraining on fresh, ethically and legally sourced datasets, their performance in DFIR scenarios may degrade over time.

4.1. GenDFIR Components

- LLM Model: Llama-3.1 a powerful model developed by Meta, evaluated on a range of standard benchmarks and human evaluations. The rationale behind selecting this model is its open-source nature and training on cybersecurity-related content [43]. This offers significant advantages for GenDFIR, as it suggests that the LLM can analyse and potentially recognise anomalous events, providing insights into cyber incidents. The model is available in different versions with varying parameter sizes, including 405B, 70B, and 8B parameters. At an early stage, we adopt the 8B model to reduce hallucinations and for system prototyping.

- Embedding Model: mxbai-embed-large, a Mixedbread release, with a maximum token limit of 512 and a maximum dimension of 1024. The model performed highly on the Massive Text Embedding Benchmark (MTEB) [60]. The reason for opting for this model is its capabilities in retrieval and semantic textual similarities. Additionally, it is effective for scoring methods during the retrieval process, such as cosine similarity, adopted in GenDFIR.

- DFIR RAG Agent: Autonomous Context-Augmented Agent, powered by Llama-3.1. Employed in GenDFIR for context-based retrieval and output generation. Operating autonomously as an expert in Cybersecurity and DFIR, specialising in DFIR Timeline Analysis and tasked with identifying events and information related to cyber incidents from our knowledge base containing cyber incident events.

4.2. Experiment Environment

- Python Libraries: Our code was written in Python. The primary libraries used are PyTorch for tensor operations, NumPy for numerical computations such as cosine similarity, and pandas for data manipulation and handling embeddings.

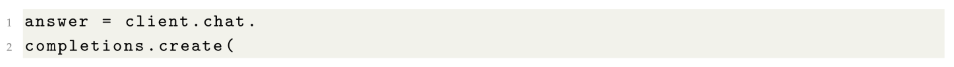

- LLM Response Temperature: The temperature of the core LLM (Llama3.1:8b) is set to a very low value (temperature = 0.1) to reduce perplexity and control prediction variability. This limits the generation of unnecessary content, enabling the framework to focus more effectively on the knowledge retrieved from the knowledge base, rather than relying on the LLM’s additional and irrelevant internal knowledge.

- Max Output Tokens: is set to (maxtokens=2000) to work conveniently with the embedding model (mxbai-embed-large:335m) and the LLM (llama3.1:8b) specifications.

- Number of Completions: is set to a low value (n=1) to make the LLM’s generation more deterministic and to select the optimal word predictions.

| Listing 3. GenDFIR code snippet Visualisation |

|

- 5.

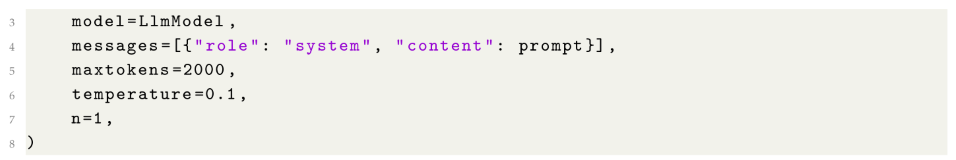

- Parallel Computing: For optimised tensor computation, CUDA is used to run the tensors on the GPU.

| Listing 4. CUDA and GPU |

|

4.3. Datasets Elaboration

5. Results, Evaluation and Discussion

5.1. GenDFIR Results

5.2. Evaluation

-

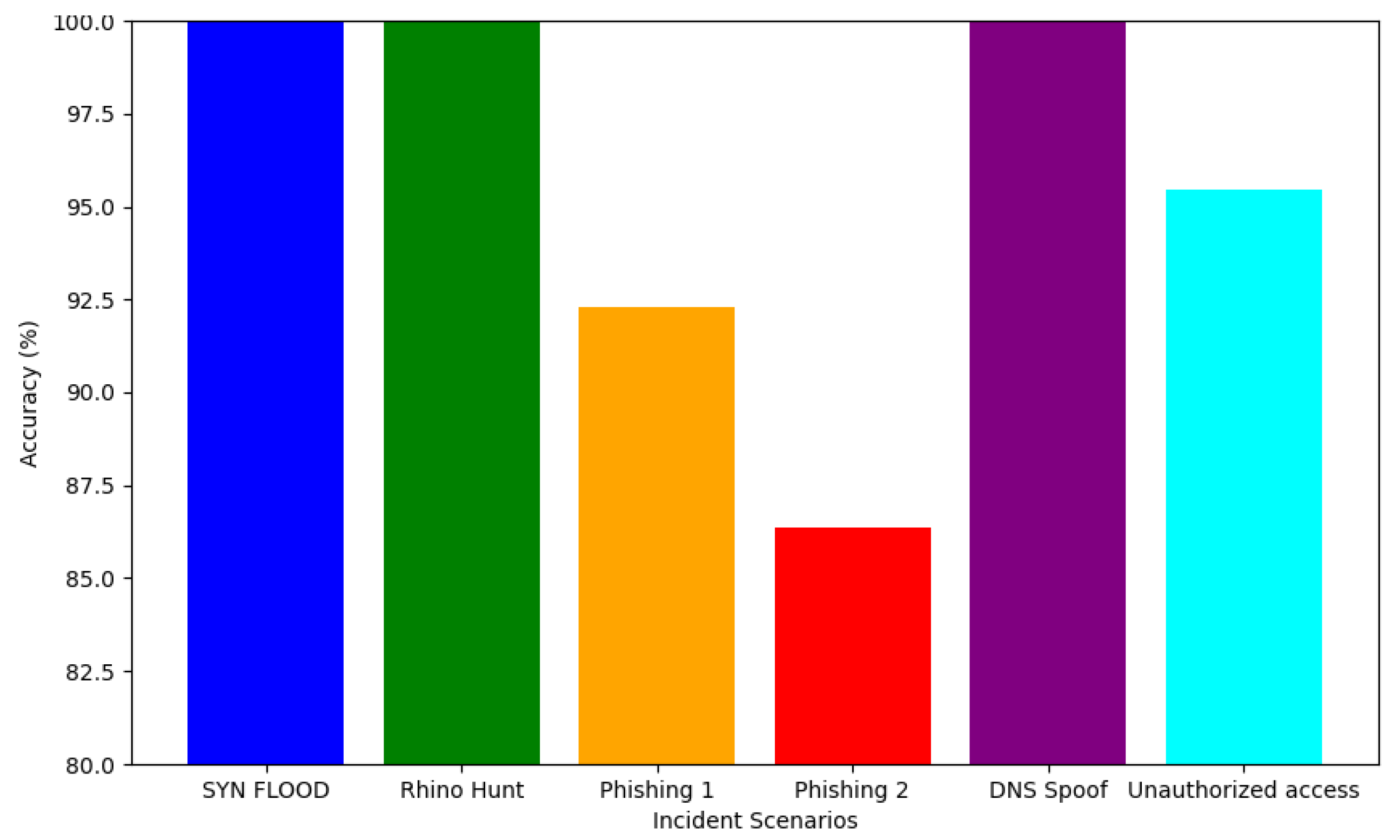

Accuracy: Accuracy in GenDFIR is determined by evaluating the generated timeline analysis reports to identify and verify the factual content, as well as to assess how and to what extent these reports can be useful and reliable in assisting DFIR experts. This process involves cross-referencing the generated information with a verified knowledge base (Incident Events) to ensure correctness and relevance while confirming that interpretations are logical and reasonable. The reports are divided into two sections:

- (a)

- Knowledge Base (Events) Facts Section: This section includes artefact analysis, timeline analysis, event correlation, and timeline reconstruction. These components are derived from facts retrieved from the knowledge base and enriched with contextual information by the LLM (Llama-3.1).

- (b)

- Additional Insights Facts Section: This section provides supplementary information, including mitigation strategies, recommendations, and other relevant insights. These outputs are generated using the general knowledge of the LLM (Llama-3.1) and its contextual application to the knowledge base (Incident Events).

The accuracy of GenDFIR reports is evaluated using a proposed equation designed to quantify the proportion of verified correct facts relative to the total number of facts generated. The equation is defined as:Where according to Table 7:- Overall Corerct Facts: Are the total number of accurate facts obtained by combining the correct facts from the incident knowledge base with the correct facts generated by the LLM, as shown in Table 7

- Correct Facts: Are facts that are verified and deemed accurate individually from both the incident knowledge base and the LLM-generated facts

- Incorrect Facts: Similarly, facts that are inaccurate and identified separately from each source.

Based on extensive monitoring and assessment of the Timeline Analysis reports and results, as illustrated in Table 7, minor incident events found in the generated report, along with their interpretation and retrieval, have been identified as incorrect in some scenarios. For instance, in Phishing Email-1, it was reported that "2. Follow-up emails attempting to get Michael to verify his account through a link (10:45 AM, 03:00 PM, and 04:30 PM)" is incorrect, as the time (04:30 PM) does not exist and is not mentioned in the incident events knowledge base. On the other hand, the additional knowledge generated by the LLM was all correct. For example, in the SYN-FLOOD scenario, the key discoveries generated and found in the Timeline report were relevant **Key Discoveries** * Multiple SYN flood attacks detected throughout the day. * High volume of SYN packets and excessive packet volumes exceeded thresholds. * Regular network performance checks revealed potential issues and were successfully cleared. " Even though these discoveries and knowledge are general knowledge related to any type of SYN flood attack, they were accurate in this context.

- 2.

-

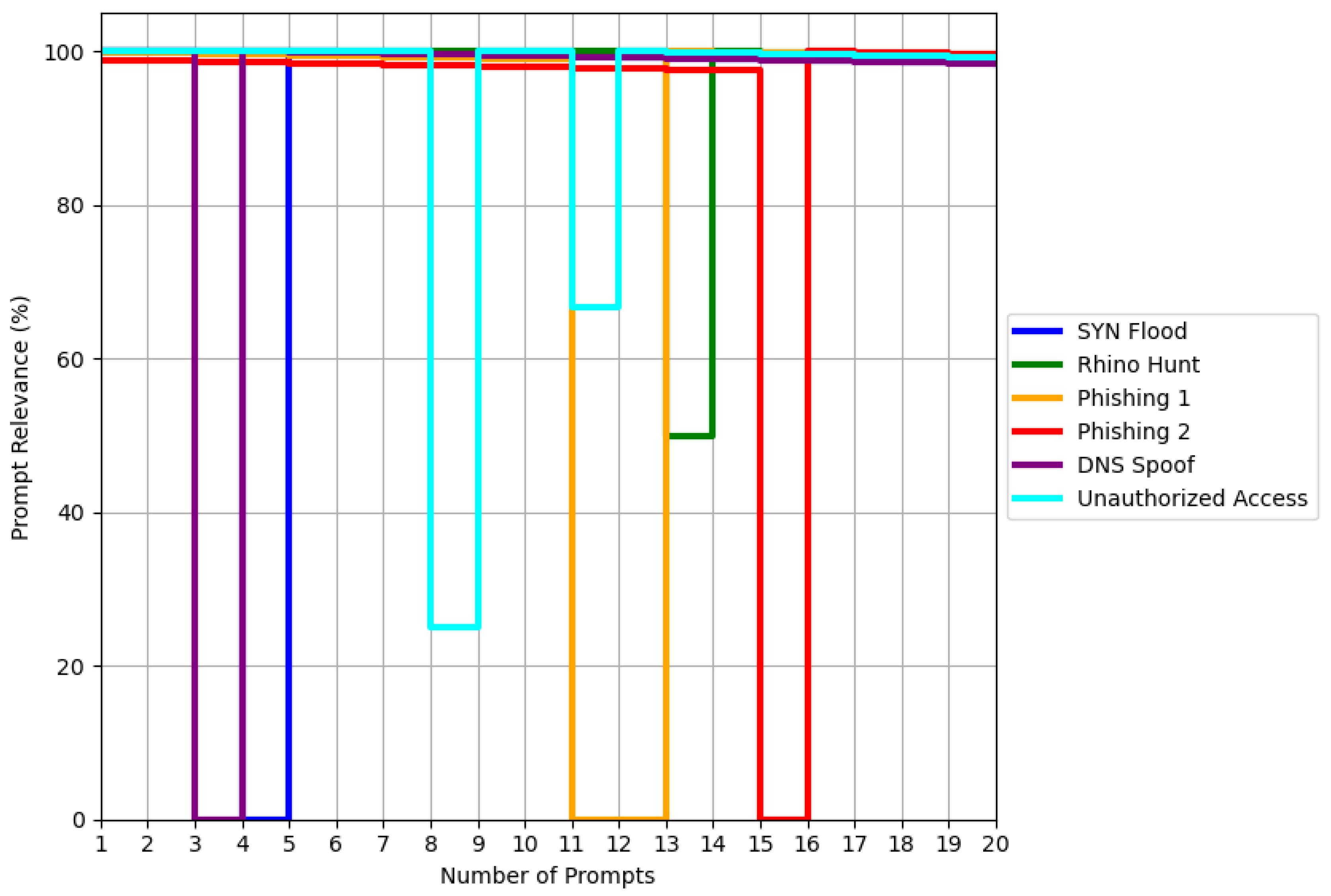

Relevance: In this context, we define the relevance metric as the extent to which the answers provided by the framework are pertinent. To measure this, we have crafted 20 DFIR context-specific prompts (available on [62] - 240 Prompts in total) in the form of questions for each scenario related to the incident. These prompts are characterised by their focus on various aspects, including sentiment (e.g., "What is the overall sentiment of the image described in Event 2 (Image b)?" - Rhino Hunt Scenario), intention (e.g., "What specific action is requested by GlobalBank in the initial email?" - Email Phishing-1 Scenario), deep analysis (e.g., "Analyze the severity levels associated with the events involving SYN flood attacks. List the events and their corresponding severity levels." - SYN-FLOOD Scenario), as well as retrieval, prediction, and insights. According to the generated answers, GenDFIR failed to provide correct responses for certain questions (DFIR prompts). For instance, in the SYN Flood scenario, GenDFIR failed on Prompt 4; in the Rhino Hunt scenario, Prompt 13 was answered partially correctly (50%); and in the Phishing Email 1 scenario, GenDFIR failed on both Prompts 11 and 12. The correctness and incorrectness of these answers were compared and cross-referenced with the incident events knowledge base, which is considered the ground truth data. The detailed failures and successes are shown in the graph in Figure 9:The overall relevance rate of GenDFIR in this case is 94.51%.

- 3.

- Exact Match: The EM metric in GenDFIR is designed to evaluate the framework’s ability to retrieve precise and granular information from the knowledge base. It tests the framework’s performance by posing DFIR questions that require exact matches to the ground truth data. This includes specific details such as timestamps (e.g., "What was the exact time when Michael Davis responded to the first email from the GlobalBank Security Team?)" and descriptions (e.g., "In Event 5, what was the description of the alligator?)", along with other relevant queries. Results found in [62] show that GenDFIR has performed well, aligning perfectly with the ground truth. GenDFIR successfully passed all checks without any errors. Therefore, the EM in this case is rated at 100%, as all 20 prompts were answered correctly.

- 4.

-

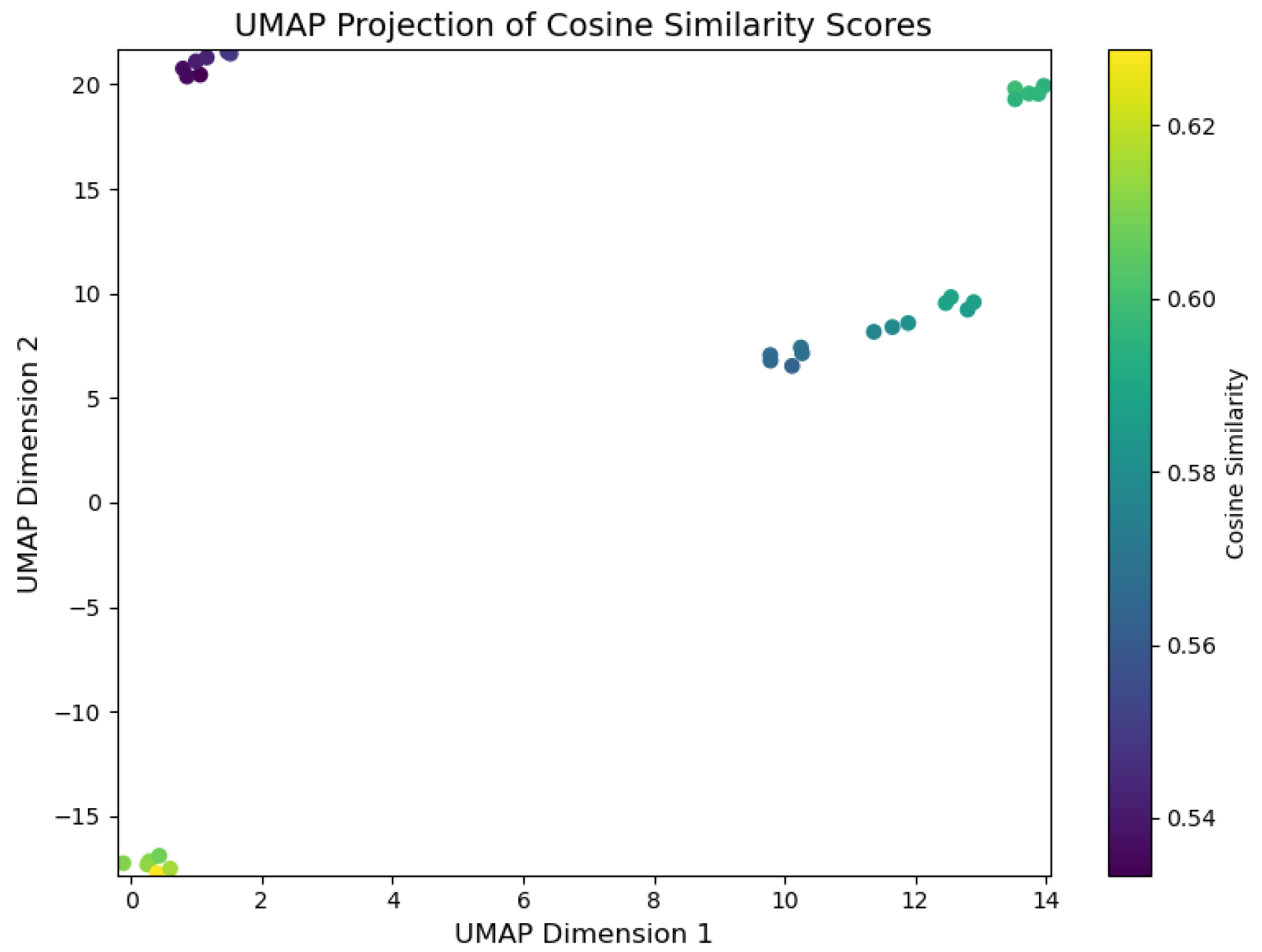

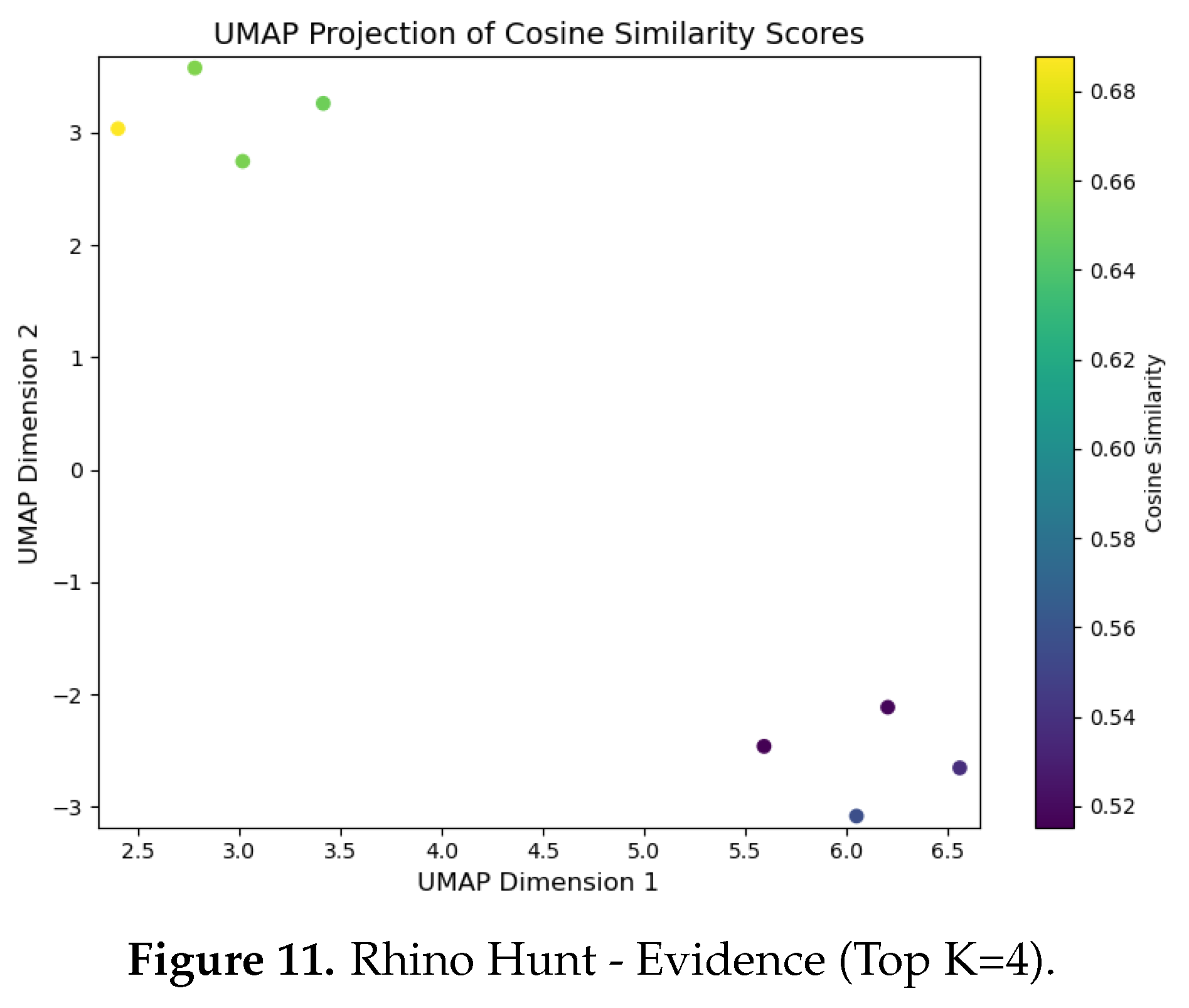

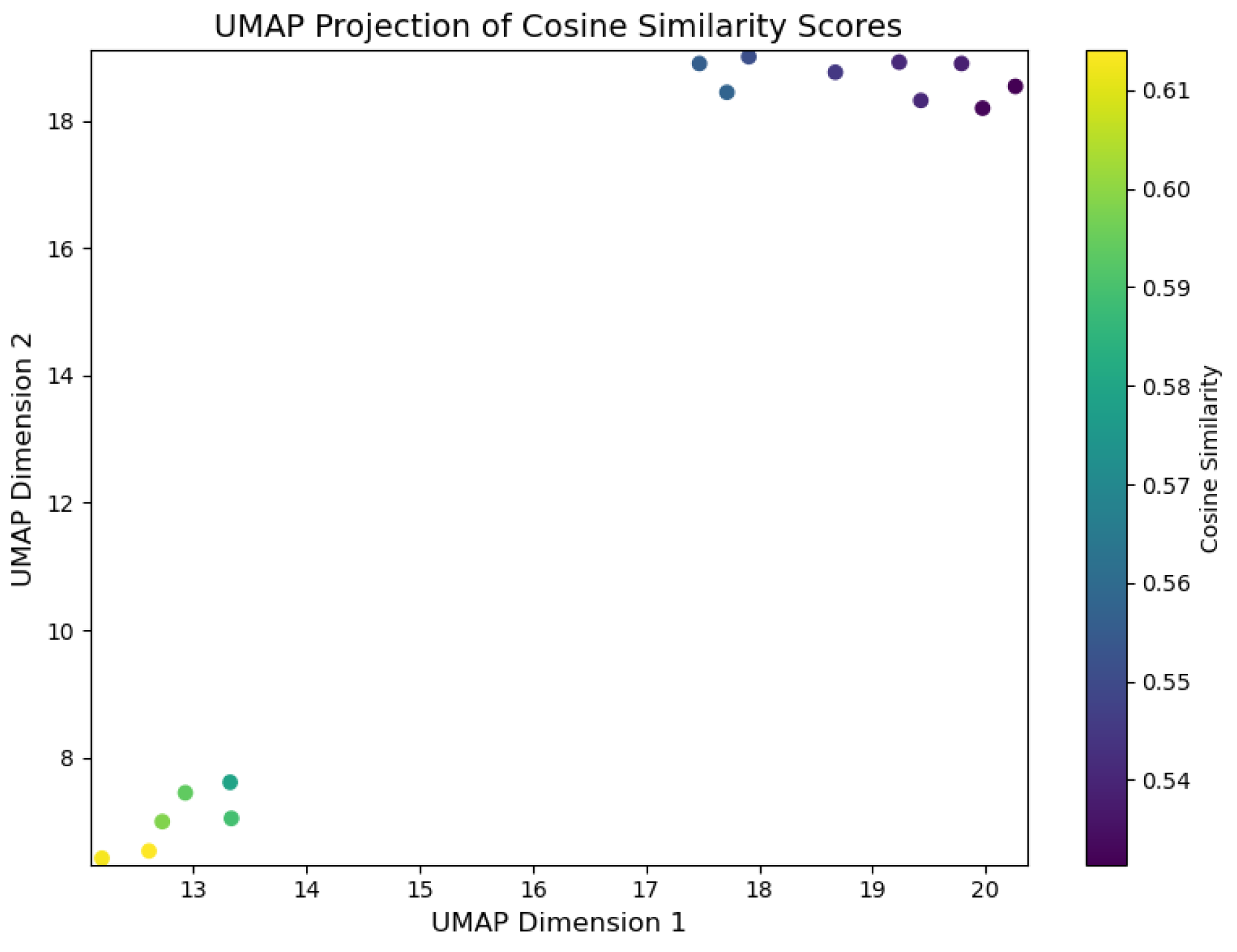

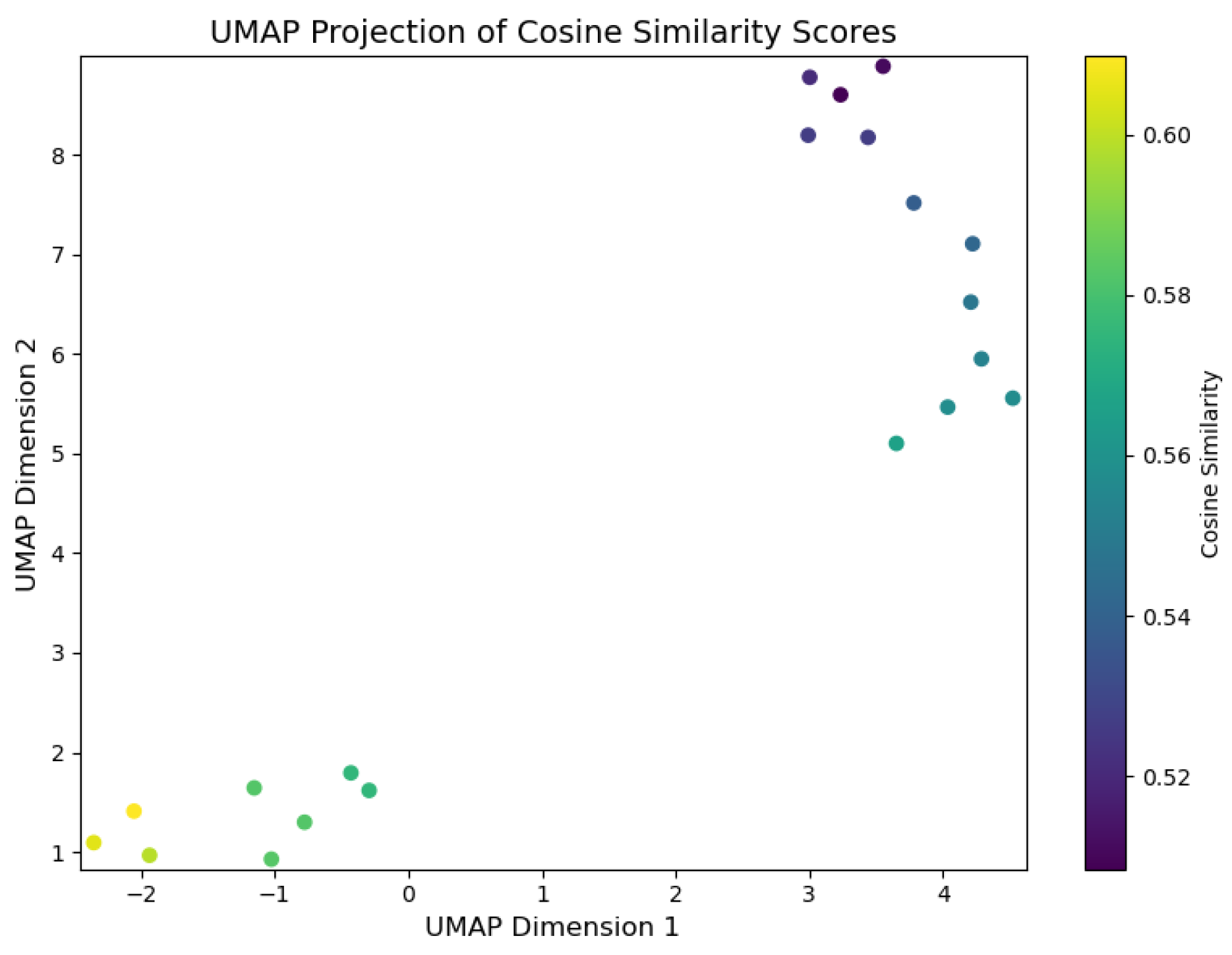

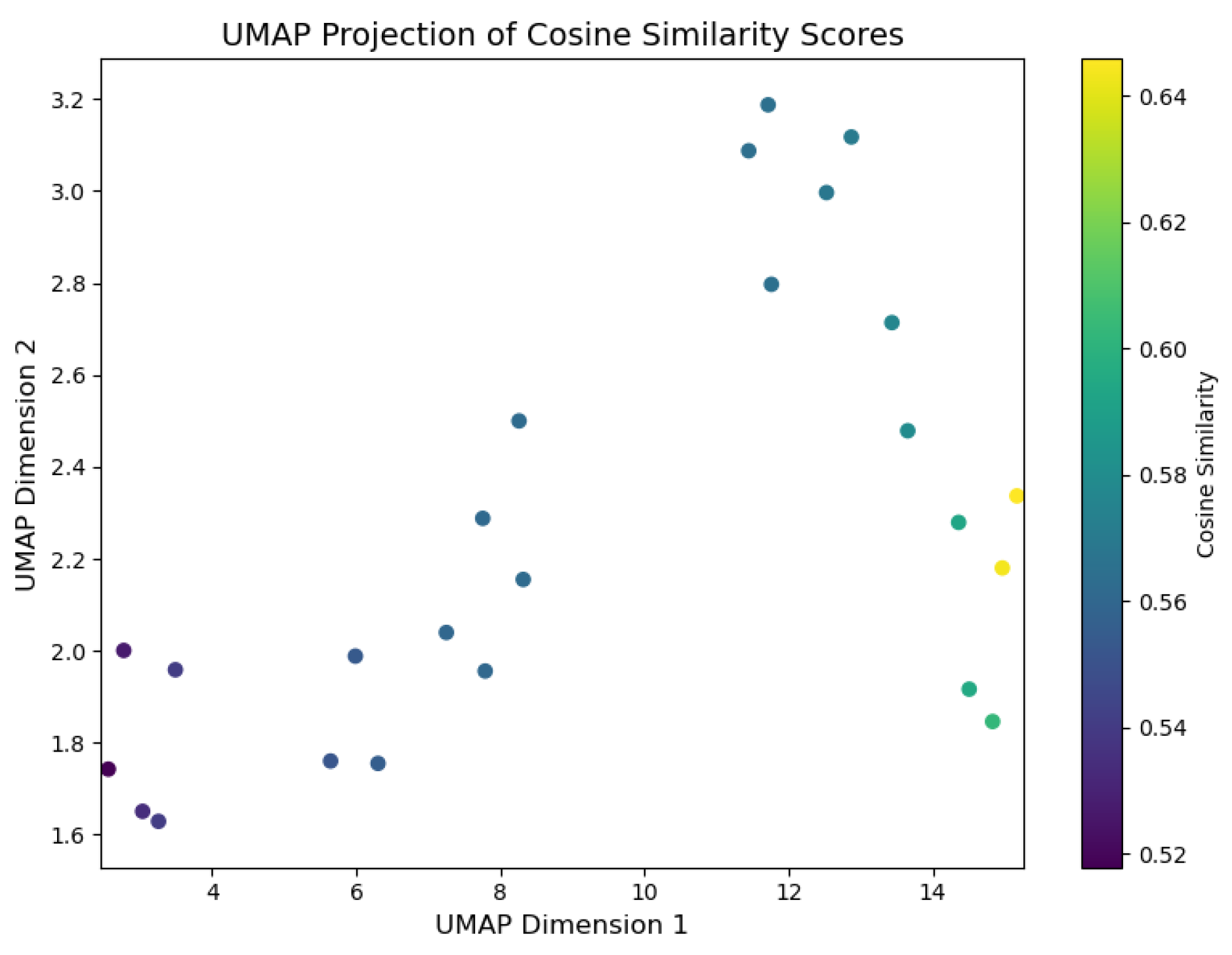

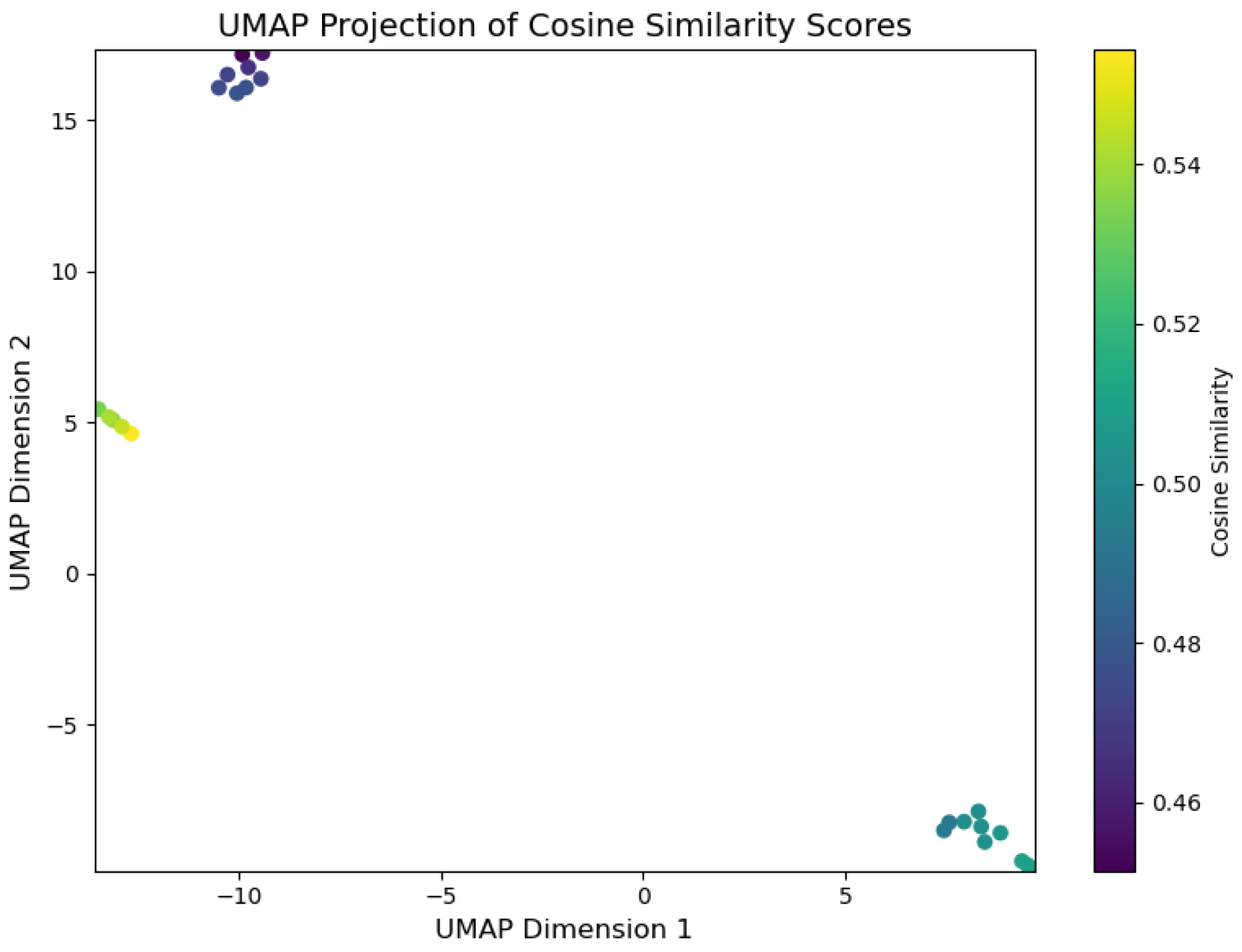

Evidence (Top-k) : DFIR Timeline Analysis is primarily focused on identifying evidence through the analysis of digital artefacts, with the correlation between events linked to the relevance of evidence deemed pertinent to the incident. To facilitate real-time visualisation of evidence identification during inference, we developed a script, illustrated in Listing 4, which uses the UMAP library.

-

UMAP Library Adaptation for GenDFIR: The UMAP library contains algorithms used for dimensionality reduction and visualisation, enabling the identification of the closest data points in a 2D vector space. These algorithms work by calculating the distances between data points, selecting the nearest neighbours, and generating a graphical representation that illustrates how data points are related, preserving both local and global structures [63]. In the context of GenDFIR, we developed a script using this library to visualise the relationship between features from the vectorised user input and their corresponding features in the embedded knowledge base (Incident Events ). This process helps identify how input data from the DFIR expert aligns with relevant incident events.It is important to note that evidence identification in this scenario depends on the input provided by the user, who determines which events or attributes should be considered as evidence. In other words, the evidence is solely based on the query prompts issued by the DFIR expert, whose suspicious assessment guides the process. As discussed in the methodology, GenDFIR integrates algorithms based on cosine similarity and a DFIR-specific agent to assess relevance. In UMAP, we added a heat parameter to visualise the similarity during inference between the query from the DFIR expert and the events embeddings from the knowledge base. This heat parameter ranges from 0 to 1, where a value closer to 1 indicates stronger similarity between the query and the events embeddings, and a value closer to 0 indicates weaker similarity. The colour intensity in the visualisation reflects this similarity, with higher values (closer to 1) represented by warmer colours, signifying that the events are more relevant to the query. In addition to this, the script leverages the traditional functionality of the UMAP algorithm, which clusters data points according to how similar they are to each other.

To interpret the graphs generated by UMAP, data points that are close to each other indicate higher contextual similarity. During inference, events deemed relevant to the query will be positioned near one another in the visualisation. The heat parameter, represented by colour variation, reflects the degree of similarity between the data points, with warmer colours indicating a stronger match to the expert’s query. -

| Listing 5. Code snippet for Calculating and Visualising Similarity |

|

5.3. GenDFIR Overall Performance

5.4. Discussion

- Event Chronology: A detailed timeline of events, presenting a chronological order of activities related to the incident.

- Evidence Correlation: Analysis of how various pieces of evidence relate to the timeline.

- Incident Overview: A summary of the incident, including key findings and impacts.

- Technical Stakeholders: Forensics experts and IT professionals require detailed, technical reports with precise timestamps, technical analysis, and evidence correlation. For example, a technical report may include granular timestamps of system log entries and detailed forensic data.

- Non-Technical Stakeholders: Reports for non-technical audiences, such as senior management or legal teams, present a streamlined timeline with key events highlighted. These reports focus on the overall sequence of events and impacts, formatted to be accessible and understandable to non-experts. An example is an Executive Summary followed by a simplified timeline of events.

6. Limitations and Ethical Issues

6.1. Limitations

- Novelty of Approach: The application of LLMs to DFIR Timeline Analysis is a relatively novel approach. The limited existing research on automating Timeline Analysis means there are few established guidelines or benchmarks, which has necessitated the development of a new context and methodology for this task.

- Data Volume and Variety: The large volume and heterogeneity of data in cyber incident scenarios present significant challenges for data management and processing [22]. Moreover, adapting solutions to real-world cyber incidents and DFIR practices is particularly difficult, as each incident introduces unique challenges that require tailored approaches. Data can vary considerably from one incident to another, and the rules that trigger each incident can differ [65], further complicating the solution. In the case of GenDFIR, our experiments were conducted using synthetic and oversimplified cyber incident scenarios, excluding anti-forensics techniques.

- Privacy and Data Security: Handling DFIR cases often requires access to sensitive personal data. To mitigate the risk of exposing real personal information, we have used synthetic data derived from synthetic cyber incidents as an alternative.

- Evaluation Methods: Assessing the effectiveness and performance of our framework presents significant challenges, particularly in the context of DFIR practices. Current research on automated evaluation methods for LLMs and AI systems in domain-specific applications is still in its early stages, and most approaches rely heavily on manual evaluation. In our case, this necessitated the creation of custom DFIR context-based evaluation prompts to measure performance. However, even with the proposed metrics, we contend that they are insufficient. The DFIR field is inherently complex and non-deterministic, with results often influenced by a wide range of unpredictable factors, such as varying incident types, data quality, and contextual nuances. These variables complicate the ability to derive consistent, controlled outcomes, making automated evaluation. Moreover, the dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of cyber incidents demands evaluation methods that can adapt to real-world scenarios’ technical and contextual variables, presenting an ongoing challenge to develop robust, reliable assessment frameworks.

6.2. Ethical Issues

- Privacy and Confidentiality: The use of LLMs to advance cyber incident timeline analysis can lead to significant privacy breaches. These technologies often require access to and process vast amounts of sensitive data, including personal, digital, financial, health, and other types of information, all of which must comply with security standards and frameworks. This increases the risk of exposing personal and confidential information without proper safeguards.

- Accuracy and Efficiency: Ensuring the accuracy and reliability of automated analyses and generated reports from the LLM-powered framework is critical. Inaccurate results could lead to flawed or irrelevant conclusions and decisions by investigators and DFIR experts, potentially affecting legal proceedings and justice.

- Consent: Obtaining proper consent from individuals whose data is used for automatic processing in real-life scenario adaptations by the framework is essential. Without explicit consent, using such data would directly violate their privacy rights.

- Bias and Fairness: One major concern with AI models is their tendency to introduce or perpetuate biases, potentially leading to unfair outcomes in cyber incident analysis. For instance, in GenDFIR, the aspect of context enrichment tied to the interpretation of the knowledge base events can introduce bias and compromise results, impacting the impartiality and credibility of investigations.

- Automatically Detected Evidence: In cases where the framework is employed to detect and retrieve evidence autonomously, improper internal processing or analysis could compromise its reliability and validity.

7. Conclusion and Future Works

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamouda, D.; Ferrag, M.A.; Benhamida, N.; Seridi, H.; Ghanem, M.C. Revolutionizing intrusion detection in industrial IoT with distributed learning and deep generative techniques. Internet of Things 2024, 26, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, G. Digital Forensics and Incident Response; Packt, 2017.

- Velociraptor. Velociraptor. https://docs.velociraptor.app/, 2024.

- FTK Exterro. FTK Forensic Toolkit. https://www.exterro.com/digital-forensics-software/forensic-toolkit, 2024.

- EnCase. EnCase Forensic Suite. https://e-forensic.ca/products/encase-forensic-suite/, 2024.

- Dissect. Dissect. https://docs.dissect.tools/, 2024.

- Timesketch. timesketch. https://timesketch.org/, 2024.

- Palso, L. log2timeline palso. https://plaso.readthedocs.io/, 2024.

- Splunk. Splunk. https://www.splunk.com/, 2024.

- Dunsin, D.; Ghanem, M.C.; Ouazzane, K.; Vassilev, V. A comprehensive analysis of the role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in modern digital forensics and incident response. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2024, 48, 301675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunsin, D.; Ghanem, M.C.; Ouazzane, K. The Use of Artificial Intelligence in Digital Forensics and Incident Response (DFIR) in a Constrained Environment. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology 2022, 280-285, 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Dunsin, D.; Mohamed, C. Ghanem, K.O.; Vassilev, V. Reinforcement Learning for an Efficient and Effective Malware Investigation during Cyber Incident Response. High-Confidence Computing 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI GPT. GPT-4. https://openai.com/index/gpt-4/, 2024.

- Meta Llama. Llama. https://llama.meta.com/, 2024.

- Anthropic Claude. Claude. https://www.anthropic.com/claude, 2024.

- Perković, G.; Drobnjak, A.; Botički, I. Hallucinations in LLMs: Understanding and Addressing Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2024 47th MIPRO ICT and Electronics Convention (MIPRO); 2024; pp. 2084–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuskley, C.; Woods, R.; Flaherty, M. The Limitations of Large Language Models for Understanding Human Language and Cognition. Open Mind 2024, 8, 1058–1083, [https://direct.mit.edu/opmi/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/opmi_a_00160/2468254/opmi_a_00160.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansurova, A.; Mansurova, A.; Nugumanova, A. QA-RAG: Exploring LLM Reliance on External Knowledge. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linzbach, S.; Tressel, T.; Kallmeyer, L.; Dietze, S.; Jabeen, H. Decoding Prompt Syntax: Analysing its Impact on Knowledge Retrieval in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Companion Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2023, New York, NY, USA, 2023; WWW ’23 Companion, p. 1145–1149. [CrossRef]

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Akhtar, N.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A Comprehensive Overview of Large Language Models, 2024. arXiv:cs.CL/2307.06435].

- Zimmerman, E. Eric Zimmerman’s tools. https://ericzimmerman.github.io/, 2024.

- Chabot, Y.; Bertaux, A.; Nicolle, C.; Kechadi, M.T. A complete formalized knowledge representation model for advanced digital forensics timeline analysis. Digital Investigation 2014, 11, S95–S105, Fourteenth Annual DFRWS Conference. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Jusas, V. The Phases Based Approach for Regeneration of Timeline in Digital Forensics. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on INnovations in Intelligent SysTems and Applications (INISTA); 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, C.; Patterson, J. An automated timeline reconstruction approach for digital forensic investigations. Digital Investigation 2012, 9, S69–S79, The Proceedings of the Twelfth Annual DFRWS Conference. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, A.; Ivezic, N.; Kulvatunyou, B.; Mavridis, I. D4I - Digital forensics framework for reviewing and investigating cyber attacks. Array 2020, 5, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- of Standards, N.I.; (NIST), T. Cybersecurity Incident. https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/cybersecurity_incident, n.d.

- VMware. Anomaly Detection. https://www.vmware.com/topics/anomaly-detection, n.d.

- Ferrag, M.A.; Alwahedi, F.; Battah, A.; Cherif, B.; Mechri, A.; Tihanyi, N. Generative AI and Large Language Models for Cyber Security: All Insights You Need, 2024. arXiv:cs.CR/2405.12750].

- Otal, H.T.; Canbaz, M.A. LLM Honeypot: Leveraging Large Language Models as Advanced Interactive Honeypot Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS); 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, K. Exploiting LLM Embeddings for Content-Based IoT Anomaly Detection. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Pacific Rim Conference on Communications, Computers and Signal Processing (PACRIM); 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariha, A.; Gharavian, V.; Makrehchi, M.; Rahnamayan, S.; Alwidian, S.; Azim, A. Log Anomaly Detection by Leveraging LLM-Based Parsing and Embedding with Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE); 2024; pp. 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Tarek, S.; Yahyaei, K.; Saha, S.K.; Zhou, J.; Tehranipoor, M.; Farahmandi, F. LLM for SoC Security: A Paradigm Shift. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 155498–155521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickramasekara, A.; Breitinger, F.; Scanlon, M. SoK: Exploring the Potential of Large Language Models for Improving Digital Forensic Investigation Efficiency. ArXiv, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, M.; Breitinger, F.; Hargreaves, C.; Hilgert, J.N.; Sheppard, J. ChatGPT for digital forensic investigation: The good, the bad, and the unknown. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2023, 46, 301609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, S.E.; Sakshi.; Wadhwa, M. Enhancing Digital Investigation: Leveraging ChatGPT for Evidence Identification and Analysis in Digital Forensics. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computing, Communication, and Intelligent Systems (ICCCIS), 2023, pp. 733–738. [CrossRef]

- Security, C. Cado Security. https://www.cadosecurity.com/, 2024.

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. A Survey on Evaluation of Large Language Models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugging Face. The Tokenizer Playground. https://huggingface.co/spaces/Xenova/the-tokenizer-playground, n.d.

- Ning, L.; Liu, L.; Wu, J.; Wu, N.; Berlowitz, D.; Prakash, S.; Green, B.; O’Banion, S.; Xie, J. USER-LLM: Efficient LLM Contextualization with User Embedding. Technical report, Google DeepMind, Google, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Wei, P.; Lin, L. Decoder-Only LLMs are Better Controllers for Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 2410957–10965. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xu, L.; Zheng, H.; Chen, L.; Tolba, A.; Zhao, L.; Yu, K.; Feng, H. Evolution and Prospects of Foundation Models: From Large Language Models to Large Multimodal Models. Computers, Materials and Continua 2024, 80, 1753–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Nikolaidis, C.; Song, D.; Molnar, D.; Crnkovich, J.; Grace, J.; Bhatt, M.; Chennabasappa, S.; Whitman, S.; Ding, S.; et al. CYBERSECEVAL 3: Advancing the Evaluation of Cybersecurity Risks and Capabilities in Large Language Models. https://github.com/meta-llama/PurpleLlama/tree/main/CybersecurityBenchmarks, 2024. Release Date: July 23, 2024.

- López Espejel, J.; Ettifouri, E.H.; Yahaya Alassan, M.S.; Chouham, E.M.; Dahhane, W. GPT-3.5, GPT-4, or BARD? Evaluating LLMs reasoning ability in zero-shot setting and performance boosting through prompts. Natural Language Processing Journal 2023, 5, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tihanyi, N.; Ferrag, M.A.; Jain, R.; Bisztray, T.; Debbah, M. CyberMetric: A Benchmark Dataset based on Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Evaluating LLMs in Cybersecurity Knowledge. 2024 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR) 2024, pp. 296–302. [CrossRef]

- Lála, J.; O’Donoghue, O.; Shtedritski, A.; Cox, S.; Rodriques, S.G.; White, A.D. PaperQA: Retrieval-Augmented Generative Agent for Scientific Research, 2023. arXiv:cs.CL/2312.07559].

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, X.; Zhang, F.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shi, T.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Qian, Q.; et al. Searching for Best Practices in Retrieval-Augmented Generation, 2024. arXiv:cs.CL/2407.01219].

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, G. Chat2Data: An Interactive Data Analysis System with RAG, Vector Databases and LLMs. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2024, 17, 4481–4484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toukmaji, C.; Tee, A. Retrieval-Augmented Generation and LLM Agents for Biomimicry Design Solutions. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Symposium Series, 2024, Vol. 3-1, pp. 273–278. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, H. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey, 2024. arXiv:cs.CL/2312.10997].

- Li, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, M.; Mei, Q.; Bendersky, M. Retrieval Augmented Generation or Long-Context LLMs? A Comprehensive Study and Hybrid Approach, 2024. arXiv:cs.CL/2407.16833].

- Xu, L.; Lu, L.; Liu, M.; Song, C.; Wu, L. Nanjing Yunjin intelligent question-answering system based on knowledge graphs and retrieval augmented generation technology. Heritage Science 2024, 12, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chroma Research. Evaluating Chunking Strategies for Retrieval. https://research.trychroma.com/evaluating-chunking, 2024.

- Lu, Y.; Aleta, A.; Du, C.; Shi, L.; Moreno, Y. LLMs and generative agent-based models for complex systems research. Physics of Life Reviews 2024, 51, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Xu, J.; Cao, Z.; Zheng, H.T.; Kim, H.G. Extending Context Window in Large Language Models with Segmented Base Adjustment for Rotary Position Embeddings. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharavy, A., Fundamental Limitations of Generative LLMs. In Large Language Models in Cybersecurity: "Threats, Exposure and Mitigation"; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 55–64. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; NIPS’17, p. 6000–6010.

- Meta, AI. Llama 3.2: Revolutionizing edge AI and vision with open, customizable models. https://ai.meta.com/blog/llama-3-2-connect-2024-vision-edge-mobile-devices/?utm_source=chatgpt.com, 2024.

- The Guardian. Meta releases advanced AI multimodal LLaMA model for EU Facebook owner. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jul/18/meta-release-advanced-ai-multimodal-llama-model-eu-facebook-owner?utm_source=chatgpt.com, 2024.

- Michelet, G.; Breitinger, F. ChatGPT, Llama, can you write my report? An experiment on assisted digital forensics reports written using (local) large language models. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2024, 48, 301683, DFRWS EU 2024 - Selected Papers from the 11th Annual Digital Forensics Research Conference Europe. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MixedBread, AI. MXBAI-Embed-Large-V1 Documentation. https://www.mixedbread.ai/docs/embeddings/mxbai-embed-large-v1, 2024.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. RhinoHunt. https://cfreds.nist.gov/all/NIST/RhinoHunt, 2005.

- Loumachi, F.Y.; Ghanem, M.C.; Ferrag, M.A. GenDFIR: Advancing Cyber Incident Timeline Analysis Through Retrieval-Augmented Generation and Large Language Models. https://github.com/GenDFIR, 2024.

- UMAP. How UMAP Works. https://umap-learn.readthedocs.io/en/latest/how_umap_works.html, 2024.

- Jiménez, M.B.; Fernández, D.; Eduardo Rivadeneira, J.; Flores-Moyano, R. A Filtering Model for Evidence Gathering in an SDN-Oriented Digital Forensic and Incident Response Context. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 75792–75808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.C.; Chen, T.M.; Ferrag, M.A.; Kettouche, M.E. ESASCF: Expertise Extraction, Generalization and Reply Framework for Optimized Automation of Network Security Compliance. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 129840–129853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynan, P. The integration and implications of artificial intelligence in forensic science. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology 2024, 20, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Finding | Approach | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| Tool: Eric Zimmerman’s tools [21] | Processing various types of data, including event logs, registry entries, and metadata, to provide detailed insights into incidents. | Beyond the tools discussed earlier, others, [21], have gained recognition for their capabilities in performing timeline analysis at a deterministic forensic level. However, they are not AI-based and lack automation, relying heavily on the expertise of the analyst or investigator. |

| Study: Chabot et al. 2014 [22] | Data is collected from various sources and analyzed using tools like Zeitline and log2timeline. The FORE system manages events, semantic processing converts data into knowledge, and algorithms correlate events. Graphical visualizations then illustrate event sequences, relationships, and patterns, enhancing clarity and interpretability of the data insights. | This contribution proposes a systematic, multilayered framework focusing on semantic enrichment to tackle challenges in timeline analysis. This approach not only automates timeline analysis but also delivers semantically enriched representations of incident events. However, one apparent limitation is the reliance on multiple standalone tools, which may complicate the workflow. |

| Study: Bhandari et al. 2020 [23] | Techniques that primarily involve managing, organising, and structuring temporal artefacts into a more comprehensible timeline. Log2timeline is utilised to extract timestamps from disk image files, while Psort processes the output to further handle the temporal artefacts and generate the final timeline. | New approach that addresses the complexities and challenges of understanding generated temporal artefacts using abstraction techniques. Artefact analysis is performed manually although it claims managing the textual nature of events and produces easily interpretable results, it still relies on manual intervention for analysis. |

| Study: Christopher et al. 2012 [24] | Achieved by proposing the use of analyser plugins to conduct detailed analysis on raw, low-level events. These plugins extracted relevant data and aggregated it into high-level events. They then used Bayesian Networks to correlate and link these high-level events by performing probabilistic inference. | The study focuses on automating event reconstruction and generating a human-understandable timeline. This was The main advantage of this approach is its ability to successfully handle and process large volumes of data, as well as produce an interpretable timeline. |

| Finding | Approach | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| Study: Ferrag et al. 2024 [28] | Reviewing and examining research studies, published articles, and journals addressing the integration of generative AI and LLMs into cybersecurity. Additionally, the paper discusses features, findings, insights, and theoretical approaches derived from datasets relevant to cybersecurity, including training methods, architectures, and associated mathematical equations. | The authors provide an extensive review of the application of LLMs in the field of cybersecurity, covering its subfields, including intrusion detection, cyber forensics, and malware detection. |

| Study: Otal et al. 2024 [29], Wang et al. 2024 [30], Fariha et al. 2024 [31], Saha et al. 2024 [32] | - [29] LLaMA3 8B and 70B, and Phi3 applied to honeypot systems for conducting advanced malicious activity analysis and detection - [30] GPT and BERT, with LSTM to predict cyberattacks in IoT networks. - [31] GPT-3.5 for log summarisation to analyse and summarise log files and detect specific events. - [32] advanced paradigm utilising GPT for SOC tasks, including vulnerability insertion, security assessment, and security verification. | All of these studies explored the use of different LLMs to automate specific cybersecurity tasks by embedding them into their workflows. |

| Study: Wickramasekara et al. 2024 [33] | Theoretically introducing and explaining how LLMs can be utilised in various phases of a DF investigation and how specific models can perform particular tasks. For example, a model like GPT-3.5 can generate textual reports at the conclusion of investigations, while multimodal LLMs, such as GPT-4 and LLaVA with vision assistance, can analyse images and videos, providing contextual outputs for digital forensics. | The paper provides an extensive literature review on the integration of LLMs to advance the DF process. |

| Study: Scanlon et al. 2023 [34] | The role of ChatGPT in supporting various tasks, including artefact analysis, generating regular expressions and keyword lists, creating scripts for file carving, RAID disk acquisition, and password cracking, identifying IR sources, anomaly detection, and developing detailed forensic scenarios. | Presents a comprehensive study on how ChatGPT can assist during DF investigations, examining this concept from multiple perspectives. The paper also addresses the limitations and strengths of ChatGPT, clearly stating that while the model significantly enhances the DF process. |

| Study: Sakshi et al. 2023 [35] | ChatGPT, powered by GPT-4 and GPT-3.5 models, to analyse artefacts (input data) and extract relevant evidence, such as conversations, images, and other information pertinent to the investigation. | The paper proposes using ChatGPT to enhance digital investigations by identifying evidence during the DF process. The paper emphasises that, despite the efficiency of this method, its outputs must always be verified and monitored by humans. |

| Tool: CADO 2024 [36] | Dedicated to assisting forensic analysts with investigations by providing insights and streamlining the investigation process. | A recent AI-based platform CADO [36] powered by a local LLM has been developed. |

| Finding | Approach | Overview |

|---|---|---|

| Study: Tihanyi et al. 2024 [44] | RAG to generate high-quality, context-based questions using an external knowledge. | Paper presents RAG usage to advance the process of creating cybersecurity dataset. Subsequently, CyberMetric was used to benchmark the general cybersecurity knowledge of cybersecurity-oriented LLMs. |

| Study: Lála et al. 2023 [45] | Employing RAG agents to answer questions based on embedded scientific literature. | Paper explains and showcases the power of RAG agents in addressing some limitations of traditional LLMs, such as hallucinations and lack of interpretability. |

| Study: Wang et al. 2023 [46] | RAG extraction and retrieval are optimised using chunks and tokens, where chunks are used for text segmentation, and tokens represent units, words, or subwords within a chunk. | Authors propose an approach to enhance the performance of RAG in single LLMs for both contextual ranking and answer generation. The goal is to ensure that each chunk contains sufficient context to answer questions and queries accurately. |

| System: Chat2Data by Zhao et al. 2024 [47] | A prototype for advanced data analysis using RAG for data retrieval, and a knowledge base where all data are stored. Outputs are shown in a graphical representation. | The authors applied RAG and LLMs to build and introduce an interactive system. |

| System: BIDARA by Toukmaji et al. 2024 [48] | Employing RAG technologies and LLM agents to address the complexities of biomimicry. | An AI research assistant model was presented as a system. |

| Scenario | Description | Number of Events (Chunks) | Max Chunk Length (Characters - MaxLength) per Event | Event Splitter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SYN Flood | This is a SYN flood attack, where unusual network events disrupted standard operations. The anomalies were characterised by a high volume of Synchronise (SYN) requests, causing intermittent service degradation across the network. Data was collected from firewalls, network scanners, and Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS). The analysis focus on critical attributes such as event ID, details, level, timestamps, source, task category, and affected devices to assess the nature of the attack and identify potential threats or operational issues.

|

30 | 210 | " . " |

| Rhino Hunt (Inspired from [61]) | This scenario is inspired by the well-known "Rhino Hunt" incident, but in this case, it involves the illegal exfiltration of copyrighted rhino images. An unauthorised individual accessed the company’s FTP server and stole twelve protected images. The investigation traced the exfiltration to a device within the company’s internal network, with the stolen data directed to an external IP address. Forensic analysis revealed that the user associated with the IP address possessed additional images matching the stolen ones. The collected data included images that met specific metadata criteria, including camera model, artist, and copyright details.

- The images used in this scenario are AI-generated (using DALL·E 3) for the purpose of ensuring copyright compliance and consent. The metadata of the images has been modified to align with the scenario description and can be extracted and viewed using the Metaminer module found on [62].

|

8 | 500 | " / " |

| Phishing Email - 1 | This scenario represents a phishing attack where an employee was targeted by emails impersonating a security service. The organisation’s policy prohibits communication with untrusted domains, permitting only interactions with verified sources. All suspicious emails were collected for analysis, focusing on domains, sender and receiver details, IP addresses, email content, and timestamps to determine the nature of the attack.

|

15 | 725 | " / " |

| Phishing Email - 2 | Same as the previous scenario, this is a phishing attack where an employee was targeted by emails impersonating a trusted support service, attempting to deceive the employee into verifying account information. The organisation’s policy restricts communication with unverified domains and permits only trusted sources. All suspicious emails received during the suspected phishing period were collected for analysis, focusing on domains, sender and receiver details, IP addresses, email content, and timestamps to assess the nature of the attack.

|

20 | 500 | " / " |

| DNS Spoof | This incident involves a DNS spoofing scenario where multiple event logs were collected from various devices, including Windows event logs, DNS server logs, firewall records, and network traffic monitoring tools. Irregularities such as delayed DNS responses, inconsistent resolutions, and unexpected outbound traffic were identified, triggering alerts from the Intrusion Detection System (IDS) and performance monitoring tools.

|

23 | 200 | " . " |

| Unauthorised Access | This scenario is an unauthorised access attempt detected by an intrusion detection system (IDS). The system flagged multiple access attempts from a blacklisted IP address, which was not authorised for any legitimate activity within the network. The collected data, including warnings, errors, and critical alerts, provided the basis for further investigation into the potential breach.

|

25 | 208 | " . " |

| Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:15:05, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 5038, Details: Integrity of system file failed, Level: Error, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:16:37, Source: System, Task Category: System Integrity. Event ID: 4723, Details: Attempt to change account password, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:17:05, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Account Management. Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:17:21, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 1102, Details: Audit log cleared, Level: Critical, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:18:05, Source: Security, Task Category: Audit Logs. Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:18:55, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 4769, Details: Kerberos service ticket request failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:20:12, Source: Security, Task Category: Credential Validation. Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:21:00, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 4771, Details: Pre-authentication failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:22:30, Source: Security, Task Category: Credential Validation. Event ID: 4648, Details: Logon attempt with explicit credentials, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:23:35, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 4724, Details: Password reset attempt, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:24:12, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Account Management. Event ID: 5031, Details: Firewall service encountered an error, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:24:45, Source: Security, Task Category: Firewall. Event ID: 4776, Details: Logon failure due to incorrect credentials, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:27:15, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Credential Validation. Event ID: 4771, Details: Pre-authentication failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:30:01, Source: Security, Task Category: Credential Validation. Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:30:45, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 4723, Details: Attempt to change account password, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:31:55, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Account Management. Event ID: 5038, Details: Integrity of system file failed, Level: Error, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:32:07, Source: System, Task Category: System Integrity. Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:33:15, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 4648, Details: Logon attempt with explicit credentials, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:34:15, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 4771, Details: Pre-authentication failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:34:30, Source: Security, Task Category: Credential Validation. Event ID: 1102, Details: Audit log cleared, Level: Critical, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:35:00, Source: Security, Task Category: Audit Logs. Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:35:12, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. Event ID: 4776, Details: Logon failure due to incorrect credentials, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:36:15, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Credential Validation. Event ID: 5031, Details: Firewall service encountered an error, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:36:30, Source: Security, Task Category: Firewall. Event ID: 4625, Details: Logon attempt failed, Level: Warning, Date and Time: 2016/09/15 02:37:45, Source: Windows Security, Task Category: Logon. |

|

**Incident Analysis** I have analyzed the given event IDs to identify anomalous events, conducted a timeline analysis, correlated between them, reconstructed the events timeline, and provided precise mitigation solutions. **Event Timeline Reconstructed** 1. **2016/09/15 02:16:37**: Event ID 5038 - Integrity of system file failed (Source: System) 2. **2016/09/15 02:17:05**: Event ID 4723 - Attempt to change account password (Source: Windows Security) 3. **2016/09/15 02:17:21**: Event ID 4625 - Logon attempt failed (Source: Windows Security) 4. **2016/09/15 02:20:12**: Event ID 4769 - Kerberos service ticket request failed (Source: Security) 5. **2016/09/15 02:22:30**: Event ID 4771 - Pre-authentication failed (Source: Security) 6. **2016/09/15 02:24:12**: Event ID 4724 - Password reset attempt (Source: Windows Security) 7. **2016/09/15 02:24:45**: Event ID 5031 - Firewall service encountered an error (Source: Security) 8. **2016/09/15 02:27:15**: Event ID 4776 - Logon failure due to incorrect credentials (Source: Windows Security) 9. **2016/09/15 02:30:01**: Event ID 4771 - Pre-authentication failed (Source: Security) 10. **2016/09/15 02:31:55**: Event ID 4723 - Attempt to change account password (Source: Windows Security) 11. **2016/09/15 02:32:07**: Event ID 5038 - Integrity of system file failed [duplicated] (Source: System) 12. **2016/09/15 02:34:30**: Event ID 4771 - Pre-authentication failed [duplicated] (Source: Security) 13. **2016/09/15 02:36:15**: Event ID 4776 - Logon failure due to incorrect credentials [duplicated] (Source: Windows Security) 14. **2016/09/15 02:36:30**: Event ID 5031 - Firewall service encountered an error [duplicated] (Source: Security) 15. **2016/09/15 02:37:45**: Event ID 4625 - Logon attempt failed [duplicated] (Source: Windows Security) **Anomalous Events and Trends** 1. Multiple attempts to change account password (Event IDs 4723) between 2:17 AM and 2:31 AM. 2. Repeated pre-authentication failures (Event ID 4771) between 2:22 AM and 2:34 AM. 3. Logon attempt failures (Event IDs 4625, 4627) multiple times between 2:17 AM and 2:37 PM. 4. Firewall service encountered errors (Event ID 5031) at different intervals between 2:24 AM and 2:36 PM. **Root Cause Analysis** These events suggest a possible malicious action or an automated script that was attempted to gain unauthorized access. The repeated failures may indicate a faulty password reset attempt or other security measures that could not be bypassed. **Mitigation Solutions** 1. **Enhance Security Measures**: Immediate updates and patches should be applied to counter vulnerabilities. 2. **Alert System Deployment**: Activate systems capable of detecting such attempts in real-time to prevent further occurrences. 3. **Audit Logging Review**: Review all logging mechanisms to determine if more detailed records are needed. 4. **Training Session**: Update security training to emphasize common attack vectors and prevention strategies. **Recommendations** 1. The security team needs to review the system’s configuration for any vulnerabilities that could have been exploited. 2. Investigate these events further with a focus on identifying potential weaknesses the attacker might have used. 3. Conduct in-depth audits of systems, configurations, and account management policies to prevent similar incidents from recurring. |

| Scenarios | Overall Timeline Analysis Report Facts | Incident Knowledge Base | LLM Facts (All correct) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SYN Flood | 20 | - Correct: 17 - Incorrect: 0 |

03 |

| Rhino Hunt | 16 | - Correct: 08 - Incorrect: 0 |

08 |

| Phishing Email - 1 | 13 | - Correct: 09 - Incorrect: 1 |

03 |

| Phishing Email - 2 | 22 | - Correct: 13 - Incorrect: 03 |

06 |

| DNS Spoof | 19 | - Correct 14 - Incorrect: 0 |

05 |

| Unauthorized Access | 22 | - Correct: 14 - Incorrect: 01 |

07 |

| Cyber Incident | Criteria of Evidence (Evidence Extraction Prompt) | Incident Events - K | Evidence - Top K |

|---|---|---|---|

| SYN Flood | Identify all Events with Level: Critical. | 30 | 05 |

| Rhino Hunt (Inspired from [61]) | Rhino. | 08 | 04 |

| Phishing Email - 1 | Identify all Events that appear to be phishing. | 15 | 06 |

| Phishing Email - 2 | Identify all Events that appear to be phishing. | 20 | 07 |

| Unauthorised Access | Identify all Events with Level: Warning. | 25 | 25 |

| DNS Spoof | Identify all Events with Level: Error. | 23 | 06 |

| Metric | Rate |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 95.52%. |

| Relevance | 94.51% |

| EM | 100% |

| Top-K | 100% |

| Overall | 97.51% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).