Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. RS Structure and Characteristics

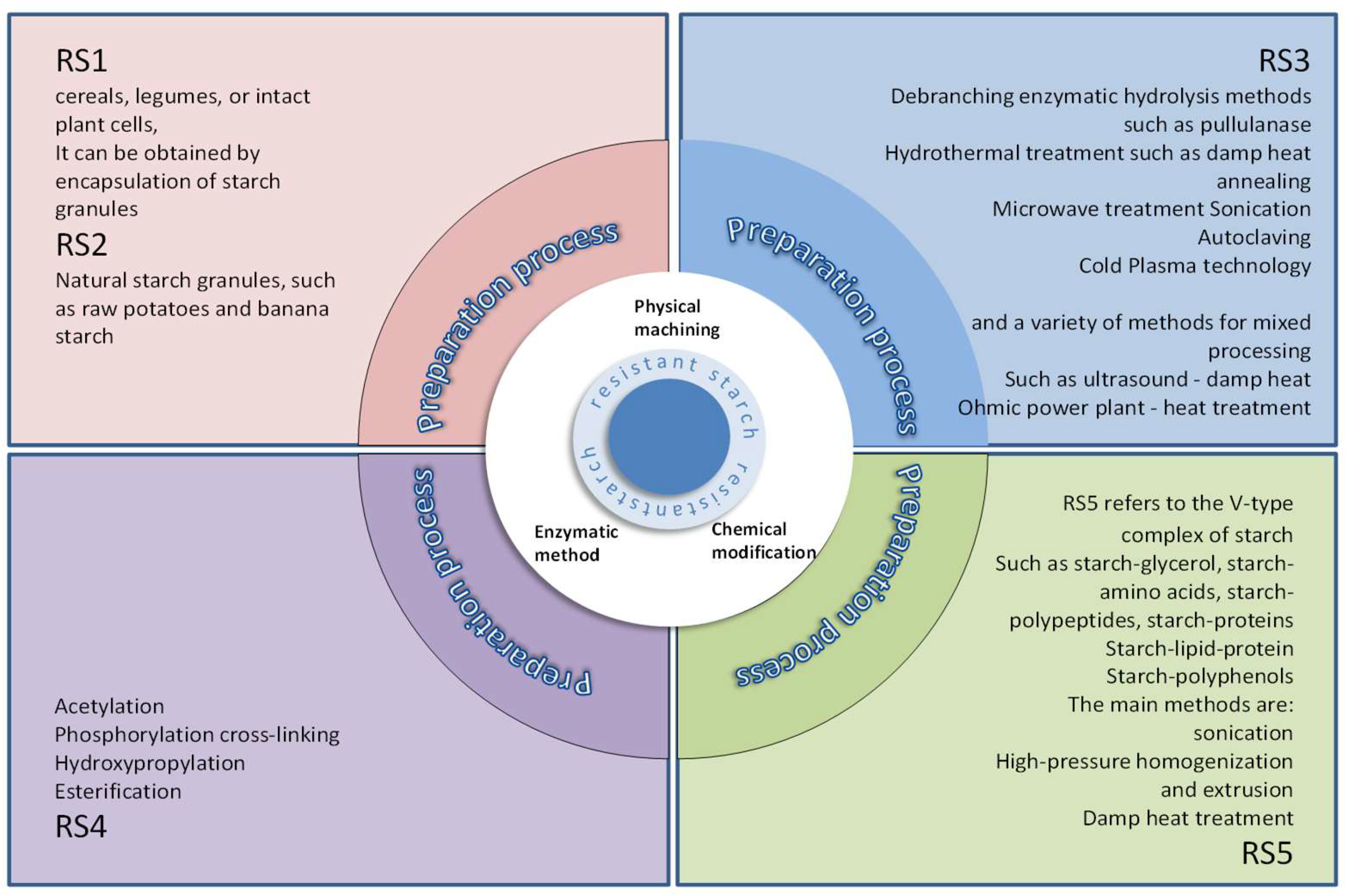

2.1. Classification of RS

2.2. RS1

2.3. RS2

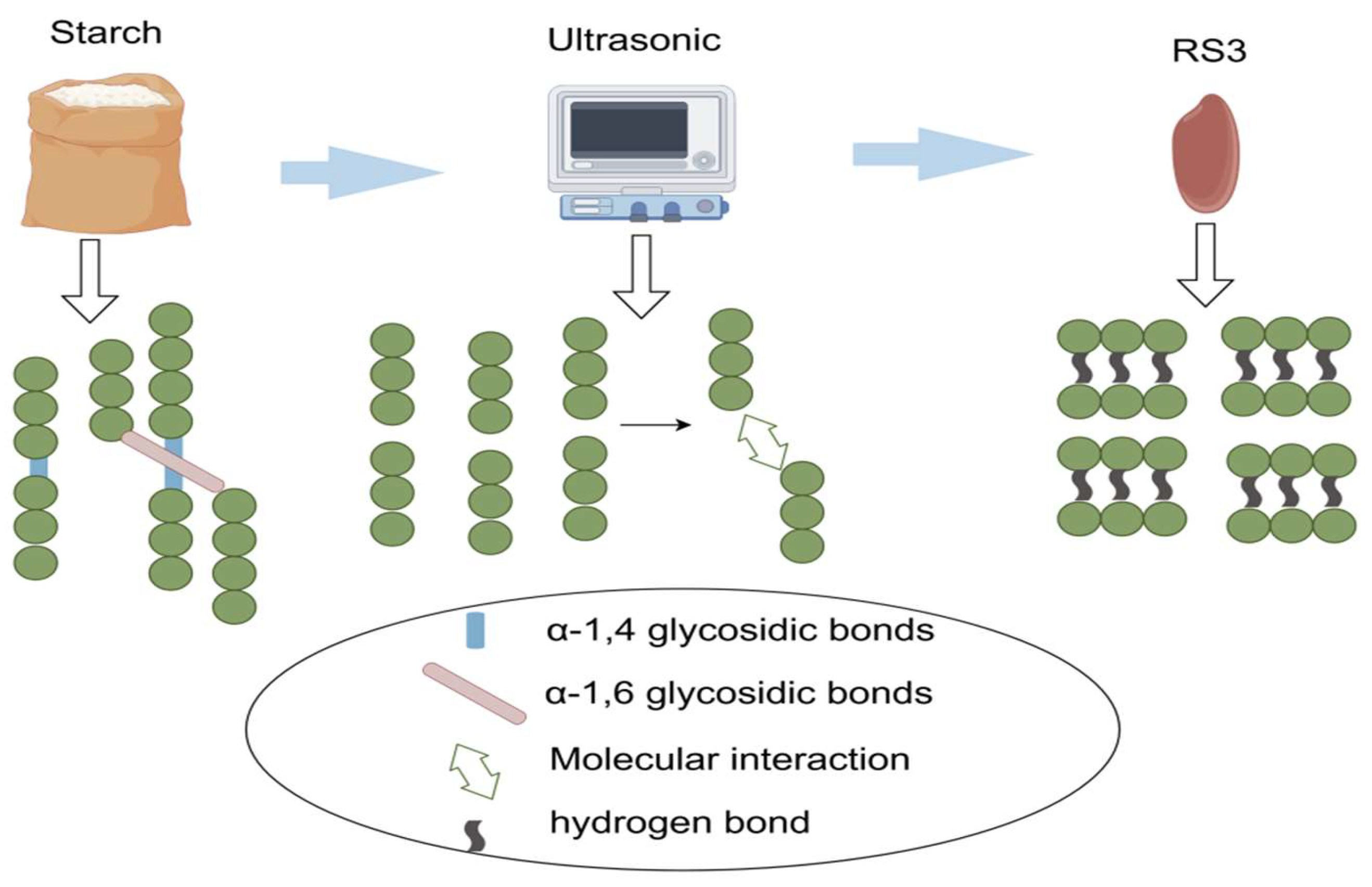

2.4. RS3

2.5. RS4

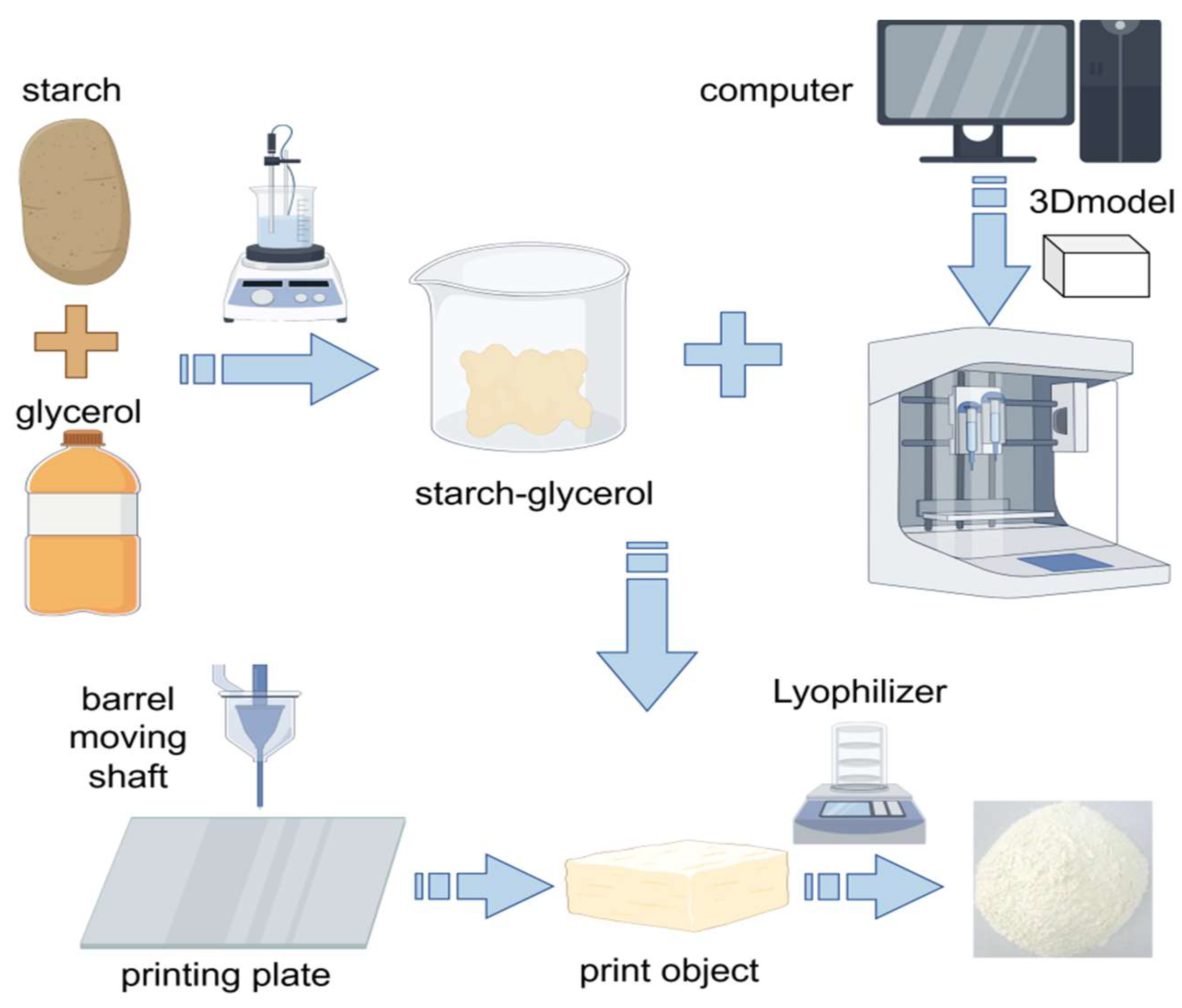

2.6. RS5

| Types | Sources | Characteristics | Production | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS1 | It is commonly found in partially milled grains like brown rice and oats, as well as in legumes such as red beans and green beans. | Starch granules that are inaccessible to amylases because of the barrier provided by the cell wall or the isolating effect of proteins. | Mildly milled grains and legumes. | [11] |

| RS2 | Raw potatoes, green bananas, high-amylose corn starch, and raw peas. | These are types of starch that are naturally resistant to digestion. | Naturally present | [27] |

| RS3 | Cooling starch-based foods, fried foods, etc. | Starch that has undergone gelatinization and then crystallized during cooling or storage, making it resistant to enzymatic degradation by amylase | Enzymatic modification, physical modification | [28] |

| RS4 | Chemical modification | Starch that becomes resistant to enzymatic degradation due to changes in its molecular structure and the introduction of certain chemical functional groups. | Enzymatic debranching, moist heat treatment, annealing, pressure cooking, microwave radiation, chemical methods | [29] |

| RS5 | The complex formed between amylose and lipids under specific conditions. | Long, unbranched starch chains combine with free fatty acids to form a digestion-resistant helical structure. | Classic synthesis, enzymatic synthesis, microwave heating, extrusion, cooking, and chemical modification combined with physical methods | [30] |

2.7. Structural Determination of RS

3. Preparation Methods of RS

3.1. Physical Methods

3.2. Chemical Methods

3.3. Enzymatic Method

| Starch Sources | Preparation Methods | RS Types | RS Yield | References |

| Rice Starch | Enzymatic Hydrolysis Heat-moisture treatment |

RS3 RS3 |

12.66% 23.2% |

[80] [81] |

| High Amylose Wheat Starch | Baking | RS3 | 11.9% | [82] |

| Wheat Starch | Extrusion | RS5 | 35.47% | [83] |

| cornstarch | Ohmic heating | RS3 | 8.29% | [84] |

| Waxy cornstarch | Enzymolysis | RS3 | 70.7% | [85] |

| High amylose cornstarch | Mechanical activation | RS3 | 53.75% | [86] |

| Buckwheat starch | Heat-moisture treatment | RS3 | 41% | [87] |

| Tapioca starch | Pulsed electric field-assisted esterification | RS4 | 47.39% | [88] |

| Sweet potato starch | Cooking | RS3 | 54.96% | [89] |

| potato starch | Toughening treatment | RS3 | 27.09% | [90] |

| Fava bean starch | Enzymatic hydrolysis + Retrogradation | RS3 | 64.88% | [91] |

| Pea starch | High-pressure homogenization | RS5 | 42% | [92] |

| Banana starch | Enzymolysis | RS3 | 68.99% | [93] |

| Yam starch | Autoclave Cross-linking processingHeat-moisture treatment |

RS3 RS4 RS3 |

35.20% 42.42% 46.34% |

[94] |

| Lotus seed starch | Autoclave | RS5 | 63.85% | [95] |

| Pueraria lobata starch | Temperature cycle crystallization | RS3 | 78.8% | [96] |

| Coix starch | Esterify | RS4 | 66% | [97] |

| Chestnut starch | Extrusion Heat-moisture treatment |

RS5 RS3 |

12.35% 41.22% |

[98] [99] |

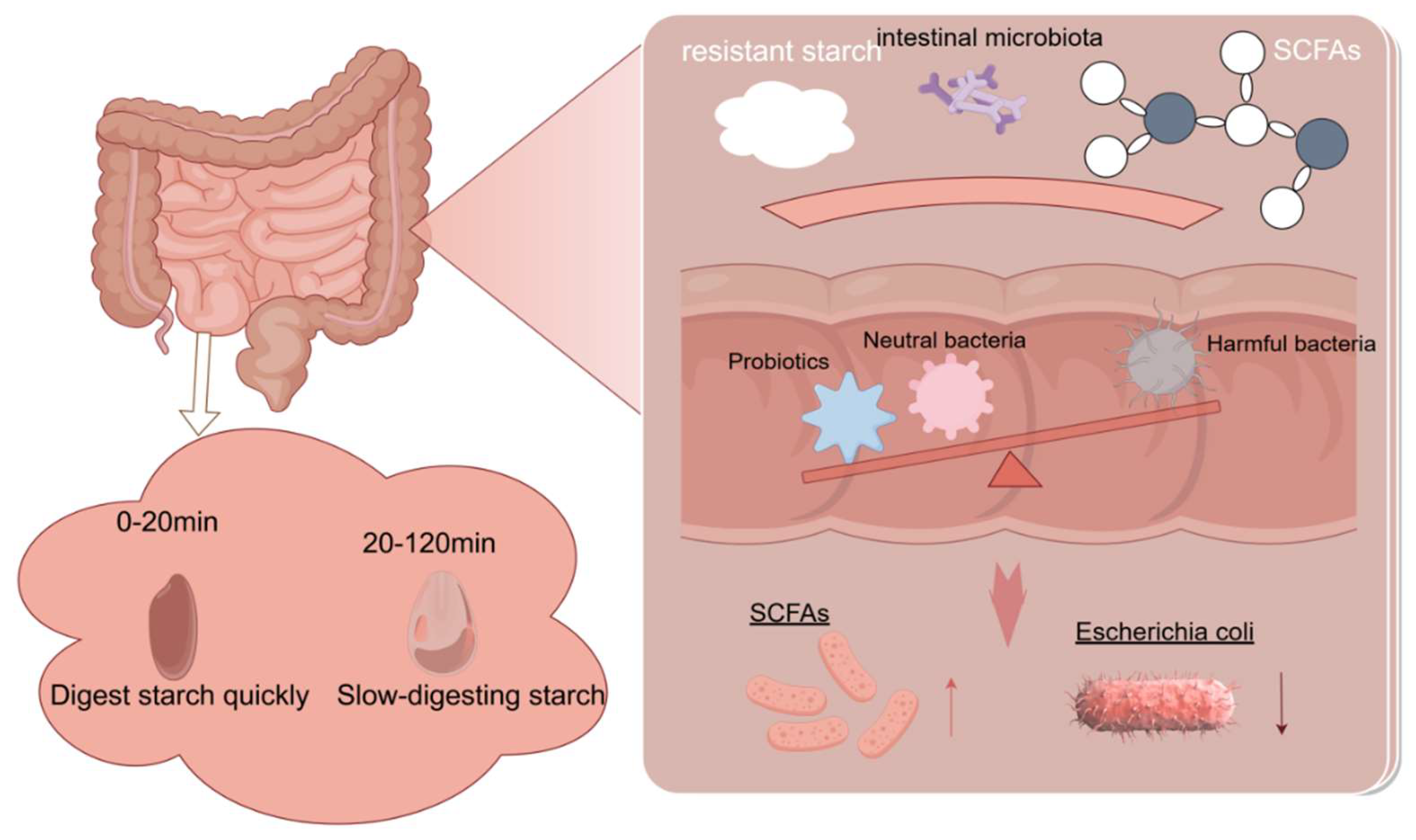

4. Functions of RS

4.1. RS and Blood Glucose Control

4.2. Resistance Starch and Colorectal Cancer Prevention

4.3. Impact on Gut Microbiota

5. Applications of RS in Food

5.1. RS as a Food Additive

5.2. RS as Dietary Fiber

5.3. Resistance Starch as a Prebiotic

5.4. Resistance Starch Facilitates Mineral Absorption

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q.; Kong, Q.; Li, F.; Lu, L.; Xu, Y.; Wei, Y. , Synthesis and Functions of Resistant Starch. Advances in Nutrition 2023, 14, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, C.; Jiao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.J.F.C. , Starch crystal seed tailors starch recrystallization for slowing starch digestion. Food Chemistry 2022, 386, 132849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haralampu, S.J.C. p. , Resistant starch—A review of the physical properties and biological impact of RS3. Carbohydrate Polymers 2000, 41, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englyst, H.N.; Kingman, S.M.; Hudson, G.J.; Cummings, J.H.J.B.J.o.N. , Measurement of resistant starch in vitro and in vivo. British Journal of Nutrition 1996, 75, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Dong, Z.; Liang, J. , Preparation of Resistant Rice Starch and Processing Technology Optimization. Starch 2021, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwar, B.A.; Gani, A.; Shah, A.; Wani, I.A.; Masoodi, F.A. , Preparation, health benefits and applications of resistant starch—A review. Starch 2015, 68, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Z.; Deng, B.; Gilbert, R.G.; Sullivan, M.A.J.I.J. o. B. M. , The effect of high-amylose resistant starch on the glycogen structure of diabetic mice. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 200, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halajzadeh, J.; Milajerdi, A.; Reiner, Ž.; Amirani, E.; Kolahdooz, F.; Barekat, M.; Mirzaei, H.; Mirhashemi, S.M.; Asemi, Z.J.C.R. i. F. S. ; Nutrition, Effects of resistant starch on glycemic control, serum lipoproteins and systemic inflammation in patients with metabolic syndrome and related disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 60, 3172–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, Q.J.F.H. , Preparation and properties of RS4 citrate sweet potato starch by heat-moisture treatment. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 55, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, J.; Ding, R.; Kang, C.; Xiao, T.; Yan, Y.J.C.P. , Impact of waxy protein deletions on the crystalline structure and physicochemical properties of wheat V-type resistant starch (RS5). Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 122695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraithong, S.; Wang, S.; Junejo, S.A.; Fu, X.; Theppawong, A.; Zhang, B.; Huang, Q.J.F.H. , Type 1 resistant starch: Nutritional properties and industry applications. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 125, 107369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, N.; Guo, X.; Fan, B.; Cheng, S.; Wang, F.J.M. , Potato Resistant Starch Type 1 Promotes Obesity Linked with Modified Gut Microbiota in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Molecules 2024, 29, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magallanes-Cruz, P.A.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Tovar, J.; Carmona-Garcia, R.J.L. , Effect of the addition of thermostable and non-thermostable type 2 resistant starch (RS2) in cake batters. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2020, 118, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magallanes-Cruz, P.A.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.; Agama-Acevedo, E.; Tovar, J.; Carmona-Garcia, R.J.L. , Effect of the addition of thermostable and non-thermostable type 2 resistant starch (RS2) in cake batters. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2020, 118, 108834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haralampu, S.J.C. p. , Resistant starch—A review of the physical properties and biological impact of RS3. Carbohydrate Polymers 2000, 41, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Cheng, B.; Lim, J.; Li, B.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.J.C.R. i. F. S.; Safety, F. , Advancements in enhancing resistant starch type 3 (RS3) content in starchy food and its impact on gut microbiota: A review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2024, 23, e13355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lertwanawatana, P.; Frazier, R.A.; Niranjan, K.J.F. c. , High pressure intensification of cassava resistant starch (RS3) yields. Food Chemistry 2015, 181, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.; Jin, Z.; Tian, Y.J.J. o. A.; Chemistry, F. , Recrystallized resistant starch: Structural changes in the stomach, duodenum, and ileum and the impact on blood glucose and intestinal microbiome in mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2023, 71, 12080–12093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaver, E.; Bilgiçli, N.J.F. c. , Effect of ultrasonicated lupin flour and resistant starch (type 4) on the physical and chemical properties of pasta. Food Chemistry 2021, 357, 129758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwar, B.A.; Gani, A.; Shah, A.; Masoodi, F.A.J.I. j. o. b. m. , Physicochemical properties, in-vitro digestibility and structural elucidation of RS4 from rice starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 105, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Xu, Q.; Kong, Q.; Li, F.; Lu, L.; Xu, Y.; Wei, Y.J.A. i. N. , Synthesis and functions of resistant starch. Advances in Nutrition 2023, 14, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Sun, R.; Zhang, Q.; Zhong, G.J.C.P. , Synthesis and characterization of citric acid esterified canna starch (RS4) by semi-dry method using vacuum-microwave-infrared assistance. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 250, 116985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Ellis, A.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, L.; Tan, L.J.C.P. , Starch-ascorbyl palmitate inclusion complex, a type 5 resistant starch, reduced in vitro digestibility and improved in vivo glycemic response in mice. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 321, 121289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ali, M.K.; Du, J.; Li, X.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Pu, X.; Yang, L.E.; Hong, J.; Mou, B.J.F.R.I. , Resistant starch in rice: Its biosynthesis and mechanism of action against diabetes-related diseases. Food Reviews International 2023, 39, 4364–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Jin, Z.; Tian, Y.J.F.H. , Insights into the structural, morphological, and thermal property changes in simulated digestion and fermentability of four resistant starches from high amylose maize starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 142, 108770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Carmona, T.J.; Tovar, J. , Update of the concept of type 5 resistant starch (RS5): Self-assembled starch V-type complexes. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.L.; Horn, W.H.; Finnegan, P.; Newman, J.W.; Marco, M.L.; Keim, N.L.; Kable, M.E.J.N. , Resistant starch type 2 from wheat reduces postprandial glycemic response with concurrent alterations in gut microbiota composition. Nutrients 2021, 13, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, X.; Boye, J.I.J.C.R. i. F. S. ; Nutrition, Research advances on the formation mechanism of resistant starch type III: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 60, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashwar, B.A.; Gani, A.; Shah, A.; Masoodi, F.A.J.S.S. , Production of RS4 from rice by acetylation: Physico-chemical, thermal, and structural characterization. Starch 2017, 69, (1–2), 1600052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, T.J.; Bello-Pérez, L.A.J.F.H. , Self-assembled and assembled starch V-type complexes for the development of functional foodstuffs: A review. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 125, 107453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Müller, E.; Meffert, M.; Gerthsen, D.J.M. ; Microanalysis, On the progress of scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) imaging in a scanning electron microscope. Microscopy and Microanalysis 2018, 24, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Siddiqui, S.; Ur Rahman, U.; Ali, H.; Saba, M.; Andleeb Azhar, F.; Maqsood Ur Rehman, M.; Ali Shah, A.; Badshah, M.; Hasan, F.J.I.J. o. F. P. , Physicochemical properties of enzymatically prepared resistant starch from maize flour and its use in cookies formulation. International Journal of Food Properties 2020, 23, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, C.; Rodríguez-Llamazares, S.; Bouza, R.; Barral, L.; Castaño, J.; Müller, N.; Restrepo, I.J.J. o. P. R. , Study of the structural order of native starch granules using combined FTIR and XRD analysis. Journal of Polymer Research 2018, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrich, M.; Terstegen, T.A.; Flöter, E.J.S.S. , Molecular investigation of the gel structure of native starches. Starch 2019, 71, 1800080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Cheng, K.; Wang, D.; Zhu, W.; Wang, X.J.I. j. o. f. p. , Analysis of crystals of retrograded starch with sharp X-ray diffraction peaks made by recrystallization of amylose and amylopectin. International Journal of Food Properties 2017, 20, sup3–S3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Lin, L.; Li, E.; Cao, Q.; Wei, C.J.M. , Relationships between X-ray diffraction peaks, molecular components, and heat properties of C-type starches from different sweet potato varieties. Molecules 2022, 27, 3385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soler, A.; Mendez-Montealvo, G.; Velazquez-Castillo, R.; Hernández-Gama, R.; Osorio-Diaz, P.; Velazquez, G.J.S.S. , Effect of crystalline and double helical structures on the resistant fraction of autoclaved corn starch with different amylose content. Starch 2020, 72, 1900306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Fu, W.; Chang, Q.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, H.J.F.C. , Moisture distribution model describes the effect of water content on the structural properties of lotus seed resistant starch. Food Chemistry 2019, 286, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Ma, R.; Chang, R.; Tian, Y.J.F.H. , Evaluation of starch retrogradation by infrared spectroscopy. Food Hydrocolloids 2021, 120, 106975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Fan, J.; Tian, Z.; Ma, L.; Meng, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Liu, X.; Kang, L.; Nan, X.J.F.C. , Effects of treatment methods on the formation of resistant starch in purple sweet potato. Food Chemistry 2022, 367, 130580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yao, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.J.F.C. , Interaction of oat avenanthramides with starch and effects on in vitro avenanthramide bioaccessibility and starch digestibility. Food Chemistry 2024, 437, 137770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; Hanashiro, I.; Fujita, N.J.J. o. A. G. , Molecular weight distribution of whole starch in rice endosperm by gel-permeation chromatography. Journal of Applied Glycoscience 2023, 70, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Hui, A.; Tao, H.; Shah, A.; Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Liu, H.J.S.S. , Improving the resistance to enzyme digestion of rice debranched starch via narrowing chain length distribution combined with oven drying. Starch 2023, 75, 2200261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Liu, Q.; Gilbert, R.G.J.C.P. , The effects of chain-length distributions on starch-related properties in waxy rices. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 339, 122264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, B.; Yang, X.; Zou, L.; Liu, J.; Liang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, N.; Ren, G.; Zhang, L.J.C.P. , Starch chain-length distributions determine cooked foxtail millet texture and starch physicochemical properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2023, 320, 121240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Du, C.; Jiang, W.; Wang, L.; Du, S.-K. J. I. J. o. B. M. , The preparation, formation, fermentability, and applications of resistant starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2020, 150, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappiban, P.; Sraphet, S.; Srisawad, N.; Ahmed, S.; Jinsong, B.; Triwitayakorna, K.J.F.C.X. , Cutting-edge progress in green technologies for resistant starch type 3 and type 5 preparation: An updated review. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 101669. [CrossRef]

- Kapelko, M.; Zięba, T.; Michalski, A.J.F.C. , Effect of the production method on the properties of RS3/RS4 type resistant starch. Part 2. Effect of a degree of substitution on the selected properties of acetylated retrograded starch. Food Chemistry 2012, 135, 2035–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-S.; Chung, H.-J. J. M. , Enhancing Resistant Starch Content of High Amylose Rice Starch through Heat–Moisture Treatment for Industrial Application. Molecules 2022, 27, 6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ward, R.; Gao, Q.J.F. h. , Effect of heat-moisture treatment on the formation and physicochemical properties of resistant starch from mung bean (Phaseolus radiatus) starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2011, 25, 1702–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.-T.; Nguyen, T.K.-A.; Pham, T.T.-H.; Nguyen, T.-D.; Nguyen, P.-H.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Nguyen, T.-T. J. F. B. , Compare the effects of moist heat treatment and annealing kinetics on the resistant starch of green banana (Musa paradisiaca L. ) starch. Food Bioscience 2024, 62, 105262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anugerah, M.P.; Faridah, D.N.; Afandi, F.A.; Hunaefi, D.; Jayanegara, A.J.I.J. o. F. S. ; Technology, Annealing processing technique divergently affects starch crystallinity characteristic related to resistant starch content: A literature review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2022, 57, 2535–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, T.S.; Felizardo, S.G.; Jane, J.-l.; Franco, C.M.J.F.H. , Effect of annealing on the semicrystalline structure of normal and waxy corn starches. Food Hydrocolloids 2012, 29, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chai, Z.; Kong, X.; Chen, S.; Ye, X.; Tian, J.J.F.C. , Effect of annealing treatment on the physicochemical properties and enzymatic hydrolysis of different types of starch. Food Chemistry 2023, 403, 134153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noor, N.; Gani, A.; Jhan, F.; Jenno, J.; Dar, M.A.J.U.S. , Resistant starch type 2 from lotus stem: Ultrasonic effect on physical and nutraceutical properties. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2021, 76, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Chen, X.; Ren, X.; Yang, X.; Raza, H.; Ma, H.J.L. , Effects of ultrasound-assisted enzymolysis on the physicochemical properties and structure of arrowhead-derived resistant starch. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2021, 147, 111616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Hao, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Exploring the formation mechanism of resistant starch (RS3) prepared from high amylose maize starch by hydrothermal-alkali combined with ultrasonic treatment. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 258, 128938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, B.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, L.; Xie, F.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Microwave reheating increases the resistant starch content in cooked rice with high water contents. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 184, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, S.; Kahraman, K.; Öztürk, S.J.I. j. o. b. m. , Optimization of resistant starch formation from high amylose corn starch by microwave irradiation treatments and characterization of starch preparations. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 95, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, J.; Qiao, D.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, B.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Microwave reheating enriches resistant starch in cold-chain cooked rice: A view of structural alterations during digestion. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2022, 208, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zeng, S.; Zeng, H.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, B.J.F. c. , Properties of lotus seed starch–glycerin monostearin complexes formed by high pressure homogenization. Food Chemistry 2017, 226, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhao, B.; Chen, L.; Zheng, B.J.N. , Physicochemical properties and digestion of lotus seed starch under high-pressure homogenization. Nutrients 2019, 11, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolidis, E.; Mandala, I.J.F.H. , Modification of resistant starch nanoparticles using high-pressure homogenization treatment. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 103, 105677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Blazek, J.; Gilbert, E.; Copeland, L.J.C.P. , New insights on the mechanism of acid degradation of pea starch. Carbohydrate Polymers 2012, 87, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wen, F.; Zhang, S.; Shen, R.; Jiang, W.; Liu, J.J.I. j. o. b. m. , Effect of acid hydrolysis on morphology, structure and digestion property of starch from Cynanchum auriculatum Royle ex Wight. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2017, 96, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Hong, Y.; Gu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Li, Z.; Li, C.J.L. , Effects of acid hydrolysis on the structure, physicochemical properties and digestibility of starch-myristic acid complexes. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2019, 113, 108274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapelko-Żeberska, M.; Zięba, T.; Pietrzak, W.; Gryszkin, A.J.I.J. o. F. S. ; Technology, Effect of citric acid esterification conditions on the properties of the obtained resistant starch. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2016, 51, 1647–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Kong, J.; Wang, R.; Liu, M.; Strappe, P.; Blanchard, C.; Zhou, Z.J.F.H. , Citrate esterification of debranched waxy maize starch: Structural, physicochemical and amylolysis properties. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 104, 105704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Zeng, X.-A.; Buckow, R.; Han, Z.J.F.H. , Structural, thermodynamic and digestible properties of maize starches esterified by conventional and dual methods: Differentiation of amylose contents. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 83, 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wu, L.; Ji, S.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.; Lu, B.J.F.H. , Modulating the digestibility of cassava starch by esterification with phenolic acids. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 127, 107432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukri, R.; Shi, Y.-C. J. F. C. , Structure and pasting properties of alkaline-treated phosphorylated cross-linked waxy maize starches. Food Chemistry 2017, 214, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Vasanthan, T.J.F.H. , Amylase resistance of corn, faba bean, and field pea starches as influenced by three different phosphorylation (cross-linking) techniques. Food Hydrocolloids 2020, 101, 105506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Masoodi, F.; Gani, A.; Ashwar, B.A.J.L. , Physicochemical, rheological and structural characterization of acetylated oat starches. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2017, 80, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Xing, B.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Wu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, W.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Study on physicochemical properties, digestive properties and application of acetylated starch in noodles. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 128, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, M.M.; Pico, J.; Gómez, M.J.F.H. , Synergistic maltogenic α-amylase and branching treatment to produce enzyme-resistant molecular and supramolecular structures in extruded maize matrices. Food Hydrocolloids 2016, 58, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Saradhuldhat, W.; Tananuwong, K.; Krusong, K.J.F.B. , Enzymes for resistant starch production. Food Bioscience 2024, 105529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Das, M.; Boral, S.; Mukherjee, G.; Chaudhury, K.; Banerjee, R.J.C. p. , Enzyme mediated resistant starch production from Indian Fox Nut (Euryale ferox) and studies on digestibility and functional properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 237, 116158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Liu, C.; Luo, S.; Hu, X.; McClements, D.J.J.F.R.I. , Modification of the digestibility of extruded rice starch by enzyme treatment (β-amylolysis): An in vitro study. Food Research International 2018, 111, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, K.; Cao, H.; Sun, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Sun, Z.; Guan, X.J.U.S. , Different multi-scale structural features of oat resistant starch prepared by ultrasound combined enzymatic hydrolysis affect its digestive properties. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 96, 106419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, H.X.N.; Song, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, B.-H.; Yoo, S.-H. J. F. H. , Characterization of rice starch gels reinforced with enzymatically-produced resistant starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 91, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Z.J.C.P. , Studies on nutritional intervention of rice starch-oleic acid complex (resistant starch type V) in rats fed by high-fat diet. Carbohydrate Polymers 2020, 246, 116637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dhital, S.; Gidley, M.J.J.F.H. , High-amylose wheat bread with reduced in vitro digestion rate and enhanced resistant starch content. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 123, 107181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, B.J.J. o. A.; Chemistry, F. , Chlorogenic Acid/Linoleic Acid-Fortified Wheat-Resistant Starch Ameliorates High-Fat Diet-Induced Gut Barrier Damage by Modulating Gut Metabolism. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-García, F.M.; Morales-Sánchez, E.; Gaytán-Martínez, M.; de la Cruz, G.V.; del Carmen Méndez-Montealvo, M.G.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Effect of electric field on physicochemical properties and resistant starch formation in ohmic heating processed corn starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 266, 131414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Sweedman, M.C.; Shi, Y.-C. J. C. P. , Structural changes and digestibility of waxy maize starch debranched by different levels of pullulanase. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 194, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Fan, S.; Cai, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Hu, H.; Liang, J.J.F.C. , Formation of type 3 resistant starch from mechanical activation-damaged high-amylose maize starch by a high-solid method. Food Chemistry 2021, 363, 130344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Peng, P.; Ma, Q.; Hu, X.J.F.C. , Pre-baking-steaming of oat induces stronger macromolecular interactions and more resistant starch in oat-buckwheat noodle. Food Chemistry 2023, 400, 134045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-R.; Xiao, Y.; Ali, M.; Xu, F.-Y.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Zeng, X.-A.; Teng, Y.-X. J. I. J. o. B. M. , Improving resistant starch content of cassava starch by pulsed electric field-assisted esterification. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 133272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.; Padmaja, G.; Sajeev, M.J.F. c. , Cooking behavior and starch digestibility of NUTRIOSE®(resistant starch) enriched noodles from sweet potato flour and starch. Food Chemistry 2015, 182, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-D.; Xu, T.-C.; Xiao, J.-X.; Zong, A.-Z.; Qiu, B.; Jia, M.; Liu, L.-N.; Liu, W.J.C. p. , Efficacy of potato resistant starch prepared by microwave–toughening treatment. Carbohydrate Polymers 2018, 192, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Diéguez, T.; Pérez-Moreno, F.; Ariza-Ortega, J.A.; López-Rodríguez, G.; Nieto, J.A.J.L. , Obtention and characterization of resistant starch from creole faba bean (Vicia faba L. creole) as a promising functional ingredient. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2021, 145, 111247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Fan, J.; Jin, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Rao, H.; Xue, W.J.F.R.I. , The influence mechanism of pH and polyphenol structures on the formation, structure, and digestibility of pea starch-polyphenol complexes via high-pressure homogenization. Food Research International 2024, 194, 114913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Rajan, N.; Biswas, P.; Banerjee, R.J.L. , A novel approach for resistant starch production from green banana flour using amylopullulanase. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2022, 153, 112391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Lu, J.; Huang, H.; Gao, X.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, W.J.F.H. , Four types of winged yam (Dioscorea alata L. ) resistant starches and their effects on ethanol-induced gastric injury in vivo. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 85, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, W.; Jia, R.; Zheng, B.; Guo, Z.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Insights into impact of chlorogenic acid on multi-scale structure and digestive properties of lotus seed starch under autoclaving treatment. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 278, 134863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Li, T.; Zhao, H.; Chen, H.; Yu, X.; Liu, B.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Effect of debranching and temperature-cycled crystallization on the physicochemical properties of kudzu (Pueraria lobata) resistant starch. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 129, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Choi, S.J.; Shin, S.I.; Sohn, M.R.; Lee, C.J.; Kim, Y.; Cho, W.I.; Moon, T.W.J.C.P. , Resistant glutarate starch from adlay: Preparation and properties. Carbohydrate Polymers 2008, 74, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Kang, H.; Chen, L.; Shen, X.; Zheng, B.J.C.P. , Exploring the relationship between nutritional properties and structure of chestnut resistant starch constructed by extrusion with starch-proanthocyanidins interactions. Carbohydrate Polymers 2024, 324, 121535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zheng, B.; Yang, D.; Chen, L.J.F.H. , Structural changes in chestnut resistant starch constructed by starch-lipid interactions during digestion and their effects on gut microbiota: An in vitro study. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 146, 109228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Park, J.; Kim, D.M.J.J. o. D. I. , Resistant starch and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Clinical perspective. Journal of Diabetes Investigation 2024, 15, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polakof, S.; Díaz-Rubio, M.E.; Dardevet, D.; Martin, J.-F.; Pujos-Guillot, E.; Scalbert, A.; Sebedio, J.-L.; Mazur, A.; Comte, B.J.T.J. o. n. b. , Resistant starch intake partly restores metabolic and inflammatory alterations in the liver of high-fat-diet-fed rats. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2013, 24, 1920–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Wang, J.; Kang, T.; Xu, F.; Ma, A.J.B.J. o. N. , Effects of resistant starch on glycaemic control: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Nutrition 2021, 125, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; LEE, C.J.D. , Effect of resistant starch on postprandial glucose levels in sedentary, abdominally obese persons. Diabetes 2018, 67, (Supplement_1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, K.; Thomas, E.L.; Bell, J.D.; Frost, G.; Robertson, M.D.J.D.M. , Resistant starch improves insulin sensitivity in metabolic syndrome. Diabetic Medicine 2010, 27, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindels, L.B.; Segura Munoz, R.R.; Gomes-Neto, J.C.; Mutemberezi, V.; Martínez, I.; Salazar, N.; Cody, E.A.; Quintero-Villegas, M.I.; Kittana, H.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.J.M. , Resistant starch can improve insulin sensitivity independently of the gut microbiota. Microbiome 2017, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Kan, J.J.F.S.; Wellness, H. , Effects of resistant starch III on the serum lipid levels and gut microbiota of Kunming mice under high-fat diet. Food Science and Human Wellness 2023, 12, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, X.; Zheng, B.J.F.R.B. ; Medicine, Lotus seed resistant starch causes genome-wide transcriptional changes in the pancreas of type 2 diabetic mice. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2017, 112, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sima, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.J.C. , Zinc finger proteins: Functions and mechanisms in colon cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, D.T.; Zhao, X.H.J.S.S. , Impact of exogenous strains on in vitro fermentation and anti-colon cancer activities of maize resistant starch and xylo-oligosaccharides. Starch 2017, 69, (11–12), 1700064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, J. , Resistant starch may reduce colon cancer risk from red meat. Oxford University Press US: 2014.

- Grubben, M.; Braak, C. v. d.; Essenberg, M. v.; Olthof, M.; Tangerman, A.; Katan, M.; Nagengast, F.J.D. d. ; sciences, Effect of resistant starch on potential biomarkers for colonic cancer risk in patients with colonic adenomas. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2001, 46, 750–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hylla, S.; Gostner, A.; Dusel, G.; Anger, H.; Bartram, H.-P.; Christl, S.U.; Kasper, H.; Scheppach, W.J.T.A. j. o. c. n. , Effects of resistant starch on the colon in healthy volunteers: Possible implications for cancer prevention. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1998, 67, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Montgomery, R.; Vilar, E.J.C.P.R. , Can a Banana a Day Keep the Cancer Away in Patients with Lynch Syndrome? Cancer Prevention Research 2022, 15, 557–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Lin, S.; Zheng, B.; Cheung, P.C.J.C. r. i. f. s. ; nutrition, Short-chain fatty acids in control of energy metabolism. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2018, 58, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Cao, L.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, P.; Ding, C.; Lu, W.; Jia, C.; Shao, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, D.J.M.; Proteomics, C. , Butyrate suppresses the proliferation of colorectal cancer cells via targeting pyruvate kinase M2 and metabolic reprogramming. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2018, 17, 1531–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniri, N.H.; Farah, Q.J.B.P. , Short-chain free-fatty acid G protein-coupled receptors in colon cancer. BIOCHEMICAL PHARMACOLOGY 2021, 186, 114483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.-J.; Li, M.-Z.; Hu, J.-L.; Tan, H.-Z.; Nie, S.-P. J. F. C. , Resistant starches and gut microbiota. Food Chemistry 2022, 387, 132895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Huang, C.; Lin, S.; Zheng, M.; Chen, C.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.J.J. o. a.; chemistry, f. , Lotus seed resistant starch regulates gut microbiota and increases short-chain fatty acids production and mineral absorption in mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2017, 65, 9217–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Ma, R.; Zhan, J.; Yang, T.; Tian, Y.J.F.H. , Thermal treatments modulate short-chain fatty acid production and microbial metabolism of starch-based mixtures in different ways: A focus on the relationship with the structure of resistant starch. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 149, 109576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X.J.I.J. o. B. M. , Structure properties of Canna edulis RS3 (double enzyme hydrolysis) and RS4 (OS-starch and cross-linked starch): Influence on fermentation products and human gut microbiota. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 265, 130700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bede, D.; Zaixiang, L.J.S.S. , Recent developments in resistant starch as a functional food. Starch 2021, 73, (3–4), 2000139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balic, R.; Miljkovic, T.; Ozsisli, B.; Simsek, S.J.J. o. F. P. ; Preservation, Utilization of modified wheat and tapioca starches as fat replacements in bread formulation. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2017, 41, e12888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werlang, S.; Bonfante, C.; Oro, T.; Biduski, B.; Bertolin, T.E.; Gutkoski, L.C.J.J. o. F. P. ; Preservation, Native and annealed oat starches as a fat replacer in mayonnaise. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45, e15211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Zeng, L.; Wen, X.; Huang, Q.J.F.C. , Effect of oil-modified crosslinked starch as a new fat replacer on gel properties, water distribution, and microstructures of pork meat batter. Food Chemistry 2023, 409, 135337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gałkowska, D.; Kapuśniak, K.; Juszczak, L.J.M. , Chemically modified starches as food additives. Molecules 2023, 28, 7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, N.D.; Lupton, J.R.J.A. i. N. , Dietary fiber. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 2553–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Tester, R.F.J.I. j. o. b. m. , Utilisation of dietary fibre (non-starch polysaccharide and resistant starch) molecules for diarrhoea therapy: A mini-review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2019, 122, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lončarević, I.; Pajin, B.; Petrović, J.; Nikolić, I.; Maravić, N.; Ačkar, Đ.; Šubarić, D.; Zarić, D.; Miličević, B.J.M. , White chocolate with resistant starch: Impact on physical properties, dietary fiber content and sensory characteristics. Molecules 2021, 26, 5908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianou, N.; Stratigou, T.; Christodoulatos, G.S.; Tsigalou, C.; Dalamaga, M.J.C. o. r. , Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, postbiotics, and obesity: Current evidence, controversies, and perspectives. Current Obesity Reports 2020, 9, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, T.; Dincer, E.J.A.M. ; Biotechnology, Effect of resistant starch types as a prebiotic. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2023, 107, 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, P.; Chen, C.; Huang, C.; Lin, S.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.J.F.C. , Structural properties and prebiotic activities of fractionated lotus seed resistant starches. Food Chemistry 2018, 251, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Rajan, N.; Biswas, P.; Banerjee, R.J.L. , Dual enzyme treatment strategy for enhancing resistant starch content of green banana flour and in vitro evaluation of prebiotic effect. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2022, 160, 113267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.-B.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Xu, J.-L.; Lu, X.; Ren, Q.J.F. , The effect of buckwheat resistant starch on intestinal physiological Function. Foods 2023, 12, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Huang, C.; Lin, S.; Zheng, M.; Chen, C.; Zheng, B.; Zhang, Y.J.J. o. a.; chemistry, f. , Lotus seed resistant starch regulates gut microbiota and increases short-chain fatty acids production and mineral absorption in mice. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2017, 65, 9217–9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisa, M.U.; Kasankala, L.M.; Khan, F.A.; Al-Asmari, F.; Rahim, M.A.; Hussain, I.; Angelov, A.; Bartkiene, E.; Rocha, J.M.J.C.N.E. , Impact of resistant starch: Absorption of dietary minerals, glycemic index and oxidative stress in healthy rats. Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2024, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, H.W.; Coudray, C.; Bellanger, J.; Levrat-Verny, M.-A.; Demigne, C.; Rayssiguier, Y.; Remesy, C.J.N. r. , Resistant starch improves mineral assimilation in rats adapted to a wheat bran diet. Nutrition Research 2000, 20, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).