Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

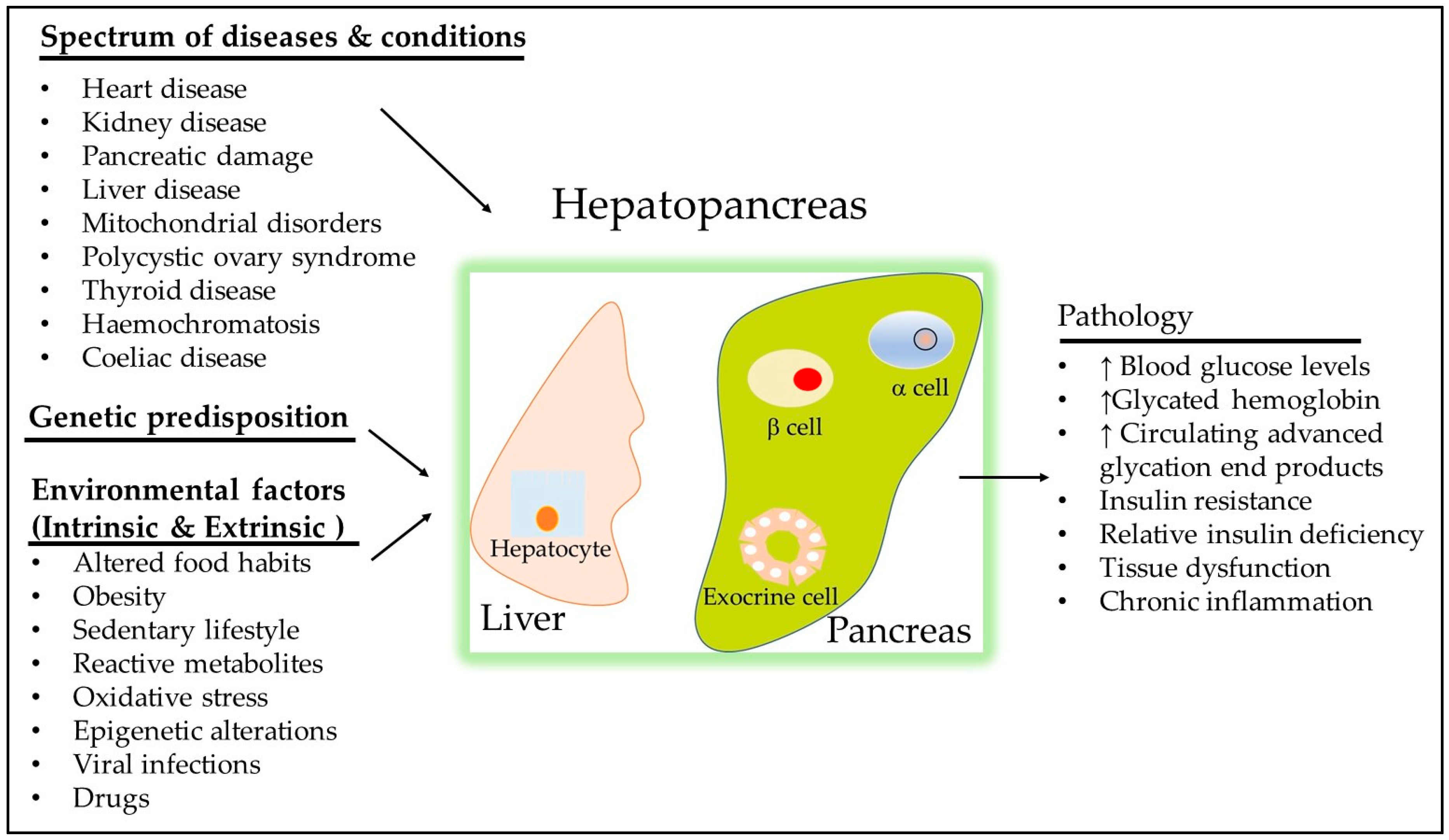

1. Introduction

2. Definition of Uncontrolled T2DM

3. Heterogeneity of Uncontrolled T2DM

3.1. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ)

3.2. Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY)

3.2.1. HNF4α and Its Role in Diabetes

3.2.2. KCNJ11 and Its Role in Diabetes

3.2.3. GLIS3 and Its Role in Diabetes

3.3. LEP Variant and Its Role in T2DM and Obesity

3.4. OPG Gene

4. Diabetes Inheritance and Personalized Treatment Approaches

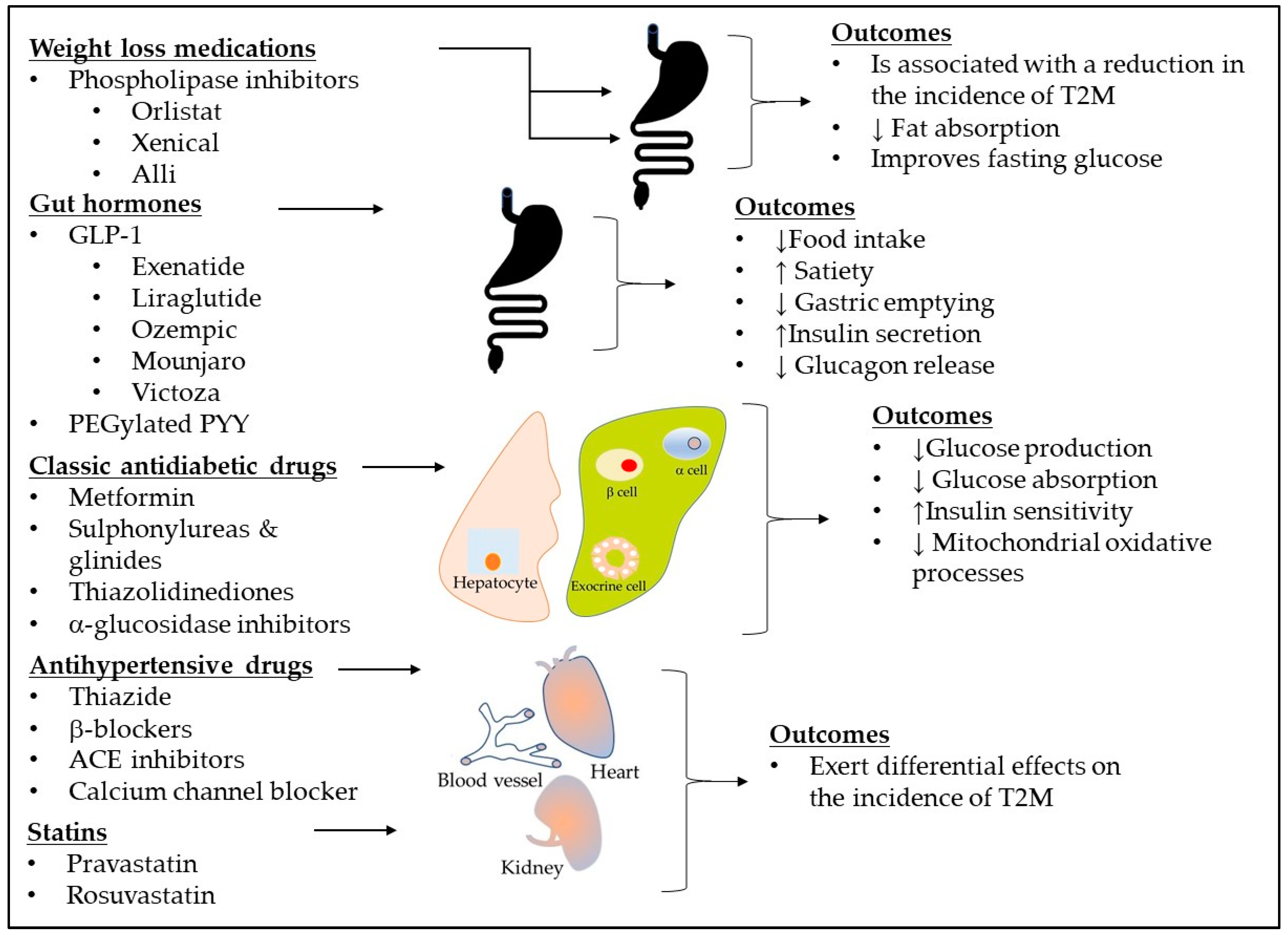

4.1. Current Treatment Guidelines for Diabetes

4.2. Genetic Variability and Ethnic Differences in Drug Response

5. Obesity and Its Association with Insulin Resistance

5.1. Gene-Environment Interactions in Obesity

5.2. Implications for Personalized Medicine and Obesity Management

6. Need for New Treatments

6.1. Novel Pharmacological Therapies in T2DM

6.1.1. Brenzavvy (Bexagliflozin)

6.1.2. Tirzepatide

6.1.3. Kerendia (finerenone)

6.2. Clinical Trial of Antidiabetic Therapy in Patients T2DM

7. Future Perspectives

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADA | American Diabetes Association |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CV | Cardiovascular |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DPP-4 | dipeptidyl peptidase-4 |

| FTO | Fat mass and obesity-associated |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GLIS3 | Gli-similar 3 |

| GLP-1 | Glucagon-like peptide-1 |

| GIP | Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| HNF4α | hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-alpha |

| HbA1C | Plasma glycosylated hemoglobin A1C |

| MC4R | Melanortin-4 receptor |

| MeSH | Medical subject headings |

| MODY | Maturity-onset diabetes of the young |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-κB |

| OPG | Osteoprotegerin |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor Gamma |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| SGLT2 | Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| TGFβ | Transforming growth factor beta |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Hollstein, T.; Basolo, A.; Ando, T.; Votruba, S.B.; Walter, M.; Krakoff, J.; Piaggi, P. , Recharacterizing the Metabolic State of Energy Balance in Thrifty and Spendthrift Phenotypes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2020, 105, 1375–1392. [Google Scholar]

- Heilbronn, L.K.; de Jonge, L.; Frisard, M.I.; DeLany, J.P.; Larson-Meyer, D.E.; Rood, J.; Nguyen, T.; Martin, C.K.; Volaufova, J.; Most, M.M.; Greenway, F.L.; Smith, S.R.; Deutsch, W.A.; Williamson, D.A.; Ravussin, E.; Pennington CALERIE Team, f. t. , Effect of 6-Month Calorie Restriction on Biomarkers of Longevity, Metabolic Adaptation, and Oxidative Stress in Overweight IndividualsA Randomized Controlled Trial. Jama 2006, 295, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, C.W.; Egan, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. , Age-Related Changes in Glucose Metabolism, Hyperglycemia, and Cardiovascular Risk. Circulation research 2018, 123, 886–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Fang, R.; Wang, H.; Xu, D.-X.; Yang, J.; Huang, X.; Cozzolino, D.; Fang, M.; Huang, Y. , A review of environmental metabolism disrupting chemicals and effect biomarkers associating disease risks: Where exposomics meets metabolomics. Environment international 2022, 158, 106941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virolainen, S.J.; VonHandorf, A.; Viel, K.C.M.F.; Weirauch, M.T.; Kottyan, L.C. , Gene–environment interactions and their impact on human health. Genes & Immunity 2023, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, F.; Liu, J.; Na, L.; Chen, L. , Roles of Epigenetic Modifications in the Differentiation and Function of Pancreatic β-Cells. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2020, 8, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snykers, S.; Henkens, T.; De Rop, E.; Vinken, M.; Fraczek, J.; De Kock, J.; De Prins, E.; Geerts, A.; Rogiers, V.; Vanhaecke, T. , Role of epigenetics in liver-specific gene transcription, hepatocyte differentiation and stem cell reprogrammation. Journal of hepatology 2009, 51, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Norton, L.E. , Metabolic adaptation to weight loss: implications for the athlete. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2014, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, P.N.; Sapper, T.N.; Crabtree, C.D.; LaFountain, R.A.; Bowling, M.L.; Buga, A.; Fell, B.; McSwiney, F.T.; Dickerson, R.M.; Miller, V.J.; Scandling, D.; Simonetti, O.P.; Phinney, S.D.; Kraemer, W.J.; King, S.A.; Krauss, R.M.; Volek, J.S. , Dietary carbohydrate restriction improves metabolic syndrome independent of weight loss. JCI insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.; Pagnini, F.; Langer, E. , Glucose metabolism responds to perceived sugar intake more than actual sugar intake. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 15633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, D.M.; Singer, D.E.; Hurxthal, K.; Goodson, J.D. , The clinical information value of the glycosylated hemoglobin assay. The New England journal of medicine 1984, 310, 341–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R.M.; Haggerty, S.; Herman, W.H. , HbA1c for the Diagnosis of Diabetes and Prediabetes: Is It Time for a Mid-Course Correction? The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2010, 95, 5203–5206. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.D., 6. Glycemic Targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2019. Diabetes care 2018, 42, (Supplement_1), S61-S70.

- Glycemic Control and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Optimal Hemoglobin A1c Targets. A Guidance Statement from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine 2007, 147, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonde, L.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Reddy, S.S.; McGill, J.B.; Berga, S.L.; Bush, M.; Chandrasekaran, S.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Einhorn, D.; Galindo, R.J.; Gardner, T.W.; Garg, R.; Garvey, W.T.; Hirsch, I.B.; Hurley, D.L.; Izuora, K.; Kosiborod, M.; Olson, D.; Patel, S.B.; Pop-Busui, R.; Sadhu, A.R.; Samson, S.L.; Stec, C.; Tamborlane, W.V., Jr.; Tuttle, K.R.; Twining, C.; Vella, A.; Vellanki, P.; Weber, S.L. , American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan—2022 Update. Endocrine Practice 2022, 28, 923–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, A.J.; Moghissi, E.S.; Bransome, E.D., Jr.; Clark, N.G.; Clement, S.; Cobin, R.H.; Furnary, A.P.; Hirsch, I.B.; Levy, P.; Roberts, R.; Van den Berghe, G.; Zamudio, V. , American College of Endocrinology position statement on inpatient diabetes and metabolic control. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 2004, 10, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-S.; Jung, S.-H.; Shivakumar, M.; Xiao, B.; Khera, A.V.; Won, H.-H.; Kim, D. , Polygenic risk for type 2 diabetes, lifestyle, metabolic health, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective UK Biobank study. Cardiovascular diabetology 2022, 21, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakso, M.; Fernandes Silva, L. , Genetics of Type 2 Diabetes: Past, Present, and Future. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajnik, C.S.; Wagh, R.; Kunte, P.; Asplund, O.; Ahlqvist, E.; Bhat, D.; Shukla, S.R.; Prasad, R.B. , Polygenic scores of diabetes-related traits in subgroups of type 2 diabetes in India: a cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health - Southeast Asia.

- Praetorius, C.; Grill, C.; Stacey, Simon N. ; Metcalf, Alexander M.; Gorkin, David U.; Robinson, Kathleen C.; Van Otterloo, E.; Kim, Reuben S. Q.; Bergsteinsdottir, K.; Ogmundsdottir, Margret H.; Magnusdottir, E.; Mishra, Pravin J.; Davis, Sean R.; Guo, T.; Zaidi, M.R.; Helgason, Agnar S.; Sigurdsson, Martin I.; Meltzer, Paul S.; Merlino, G.; Petit, V.; Larue, L.; Loftus, Stacie K.; Adams, David R.; Sobhiafshar, U.; Emre, N.C.T.; Pavan, William J.; Cornell, R.; Smith, Aaron G.; McCallion, Andrew S.; Fisher, David E.; Stefansson, K.; Sturm, Richard A.; Steingrimsson, E., A Polymorphism in IRF4 Affects Human Pigmentation through a Tyrosinase-Dependent MITF/TFAP2A Pathway. Cell 2013, 155, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar]

- Fajans, S.S.; Bell, G.I.; Polonsky, K.S. , Molecular mechanisms and clinical pathophysiology of maturity-onset diabetes of the young. The New England journal of medicine 2001, 345, 971–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Zhang, W. , Risk Factors Contributing to Type 2 Diabetes and Recent Advances in the Treatment and Prevention. International journal of medical sciences 2014, 11, 1185–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M. , Long-term noise exposure and the risk for type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis: Erratum. Noise & health 2015, 17, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Marcadenti, A. , Diet, Cardiometabolic Factors and Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus: The Role of Genetics. Current diabetes reviews 2016, 12, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuntić, M.; Hahad, O.; Münzel, T.; Daiber, A. , Crosstalk between Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Caused by Noise and Air Pollution—Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, O. , Genetics of type 2 diabetes. World journal of diabetes 2013, 4, 114–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.N.; Kleinberger, J.W.; Zhang, H.; Srinivasan, S.; Tollefsen, S.E.; Levitsky, L.L.; Levitt Katz, L.E.; Tryggestad, J.B.; Bacha, F.; Imperatore, G.; Lawrence, J.M.; Pihoker, C.; Divers, J.; Flannick, J.; Dabelea, D.; Florez, J.C.; Pollin, T.I. , Monogenic Diabetes in Youth With Presumed Type 2 Diabetes: Results From the Progress in Diabetes Genetics in Youth (ProDiGY) Collaboration. Diabetes care 2021, 44, 2312–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, M.V.; Arosemena, M.; Pollin, T.; Greeley, S.A.W.; Naylor, R.N.; Letourneau-Freiberg, L.; Bowden, T.L.; Wei, D.; Philipson, L.H., Monogenic Forms of Diabetes. In Diabetes in America, Lawrence, J.M.; Casagrande, S.S.; Herman, W.H.; Wexler, D.J.; Cefalu, W.T., Eds. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK): Bethesda (MD), 2023.

- Blonde, L.; Umpierrez, G.E.; Reddy, S.S.; McGill, J.B.; Berga, S.L.; Bush, M.; Chandrasekaran, S.; DeFronzo, R.A.; Einhorn, D.; Galindo, R.J.; Gardner, T.W.; Garg, R.; Garvey, W.T.; Hirsch, I.B.; Hurley, D.L.; Izuora, K.; Kosiborod, M.; Olson, D.; Patel, S.B.; Pop-Busui, R.; Sadhu, A.R.; Samson, S.L.; Stec, C.; Tamborlane, W.V., Jr.; Tuttle, K.R.; Twining, C.; Vella, A.; Vellanki, P.; Weber, S.L. , American Association of Clinical Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline: Developing a Diabetes Mellitus Comprehensive Care Plan-2022 Update. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists 2022, 28, 923–1049. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.S.; Ekinci, E.I.; Pyrlis, F. , Maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD): An uncommon but important cause of diabetes. Endocrine and Metabolic Science 2021, 2, 100074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, L.E.; Severin, N.E. , Maternally Inherited Diabetes and Deafness in a North American Kindred: Tips for Making the Diagnosis and Review of Unique Management Issues. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2006, 91, 4737–4742. [Google Scholar]

- Urano, F. , Wolfram Syndrome: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Current diabetes reports 2016, 16, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, A., Bardet-Biedl syndrome: A clinical overview focusing on diagnosis, outcomes and best-practice management. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2024, 26, (S2), 25-33.

- Baier, L.J.; Muller, Y.L.; Remedi, M.S.; Traurig, M.; Piaggi, P.; Wiessner, G.; Huang, K.; Stacy, A.; Kobes, S.; Krakoff, J.; Bennett, P.H.; Nelson, R.G.; Knowler, W.C.; Hanson, R.L.; Nichols, C.G.; Bogardus, C. , ABCC8 R1420H Loss-of-Function Variant in a Southwest American Indian Community: Association With Increased Birth Weight and Doubled Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2015, 64, 4322–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveline, J.P.; Rousseau, E.; Reznik, Y.; Fetita, S.; Philippe, J.; Dechaume, A.; Hartemann, A.; Polak, M.; Petit, C.; Charpentier, G.; Gautier, J.F.; Froguel, P.; Vaxillaire, M. , Clinical and metabolic features of adult-onset diabetes caused by ABCC8 mutations. Diabetes care 2012, 35, 248–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farid, M.M.M.; Abdel-Mageed, A.I.; El-sherbini, A.; Mohamed, N.R.; Mohsen, M. , Study of the association between GLIS3 rs10758593 and type 2 diabetes mellitus in Egyptian population. Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics 2022, 23, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meulebrouck, S.; Scherrer, V.; Boutry, R.; Toussaint, B.; Vaillant, E.; Dechaume, A.; Loiselle, H.; Balkau, B.; Charpentier, G.; Franc, S.; Marre, M.; Baron, M.; Vaxillaire, M.; Derhourhi, M.; Boissel, M.; Froguel, P.; Bonnefond, A. , Pathogenic monoallelic variants in GLIS3 increase type 2 diabetes risk and identify a subgroup of patients sensitive to sulfonylureas. Diabetologia 2024, 67, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayhurst, G.P.; Lee, Y.H.; Lambert, G.; Ward, J.M.; Gonzalez, F.J. , Hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha (nuclear receptor 2A1) is essential for maintenance of hepatic gene expression and lipid homeostasis. Molecular and cellular biology 2001, 21, 1393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, L.K.; Jablonski, K.A.; Warner, A.S.; Cheng, Y.C.; McAteer, J.B.; Tipton, L.; Shuldiner, A.R.; Ehrmann, D.A.; Manning, A.K.; Dabelea, D.; Franks, P.W.; Kahn, S.E.; Pollin, T.I.; Knowler, W.C.; Altshuler, D.; Florez, J.C. , Variation in Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young Genes Influence Response to Interventions for Diabetes Prevention. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2017, 102, 2678–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwege, J.N.; Hicks, P.J.; Palmer, N.D.; Ng, M.C.; Freedman, B.I.; Bowden, D.W. , Examination of Rare Variants in HNF4 alpha in European Americans with Type 2 Diabetes. Journal of diabetes & metabolism 2011, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Haghvirdizadeh, P.; Mohamed, Z.; Abdullah, N.A.; Haghvirdizadeh, P.; Haerian, M.S.; Haerian, B.S. , KCNJ11: Genetic Polymorphisms and Risk of Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of diabetes research 2015, 2015, 908152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Raza, S.T.; Mahdi, F.; Singh, S.P.; Rajput, M.; Rahman, Q. , Genetic polymorphisms in KCNJ11 (E23K, rs5219) and SDF-1β (G801A, rs1801157) genes are associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. British journal of biomedical science 2018, 75, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Chagoya, A.; Schroeder, P.; Mandla, R.; Li, J.; Morris, L.; Vora, M.; Alkanaq, A.; Nagy, D.; Szczerbinski, L.; Madsen, J.G.S.; Bonàs-Guarch, S.; Mollandin, F.; Cole, J.B.; Porneala, B.; Westerman, K.; Li, J.H.; Pollin, T.I.; Florez, J.C.; Gloyn, A.L.; Carey, D.J.; Cebola, I.; Mirshahi, U.L.; Manning, A.K.; Leong, A.; Udler, M.; Mercader, J.M. , Rare variant analyses in 51,256 type 2 diabetes cases and 370,487 controls reveal the pathogenicity spectrum of monogenic diabetes genes. Nature genetics 2024, 56, 2370–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claussnitzer, M.; Dankel, S.N.; Klocke, B.; Grallert, H.; Glunk, V.; Berulava, T.; Lee, H.; Oskolkov, N.; Fadista, J.; Ehlers, K.; Wahl, S.; Hoffmann, C.; Qian, K.; Ronn, T.; Riess, H.; Muller-Nurasyid, M.; Bretschneider, N.; Schroeder, T.; Skurk, T.; Horsthemke, B.; Spieler, D.; Klingenspor, M.; Seifert, M.; Kern, M.J.; Mejhert, N.; Dahlman, I.; Hansson, O.; Hauck, S.M.; Bluher, M.; Arner, P.; Groop, L.; Illig, T.; Suhre, K.; Hsu, Y.H.; Mellgren, G.; Hauner, H.; Laumen, H. , Leveraging cross-species transcription factor binding site patterns: from diabetes risk loci to disease mechanisms. Cell, 2014; 156, 343–358. [Google Scholar]

- Majithia, A.R.; Flannick, J.; Shahinian, P.; Guo, M.; Bray, M.-A.; Fontanillas, P.; Gabriel, S.B.; Consortium, G.D.; Project, N.J.F.A.S.; Consortium, S.T.D.; Consortium, T.D.-G.; Rosen, E.D.; Altshuler, D.; Flannick, J.; Manning, A.K.; Hartl, C.; Agarwala, V.; Fontanillas, P.; Green, T.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.; Poplin, R.; Shakir, K.; Fennell, T.; Njølstad, P.R.; Altshuler, D.; Burtt, N.; Gabriel, S.; Fuchsberger, C.; Kang, H.M.; Sim, X.; Ma, C.; Locke, A.; Blackwell, T.; Jackson, A.; Teslovich, T.M.; Stringham, H.; Chines, P.; Kwan, P.; Huyghe, J.; Tan, A.; Jun, G.; Stitzel, M.; Bergman, R.N.; Bonnycastle, L.; Tuomilehto, J.; Collins, F.S.; Scott, L.; Mohlke, K.; Abecasis, G.; Boehnke, M.; Strom, T.; Gieger, C.; Nurasyid, M.M.; Grallert, H.; Kriebel, J.; Ried, J.; Hrabé de Angelis, M.; Huth, C.; Meisinger, C.; Peters, A.; Rathmann, W.; Strauch, K.; Meitinger, T.; Kravic, J.; Algren, P.; Ladenvall, C.; Toumi, T.; Isomaa, B.; Groop, L.; Gaulton, K.; Moutsianas, L.; Rivas, M.; Pearson, R.; Mahajan, A.; Prokopenko, I.; Kumar, A.; Perry, J.; Howie, B.; van de Bunt, M.; Small, K.; Lindgren, C.; Lunter, G.; Robertson, N.; Rayner, W.; Morris, A.; Buck, D.; Hattersley, A.; Spector, T.; McVean, G.; Frayling, T.; Donnelly, P.; McCarthy, M.; Gupta, N.; Taylor, H.; Fox, E.; Cheh, C.N.; Wilson, J.G.; O'Donnell, C.J.; Kathiresan, S.; Hirschhorn, J.; Seidman, J.G.; Gabriel, S.; Seidman, C.; Altshuler, D.; Williams, A.L.; Jacobs, S.B.R.; Macías, H.M.; Chagoya, A.H.; Churchhouse, C.; Luna, C.M.; Ortíz, H.G.; Vázquez, M.J.G.; Burtt, N.P.; Estrada, K.; Mercader, J.M.; Ripke, S.; Manning, A.K.; Neale, B.; Stram, D.O.; López, J.C.F.; Hidalgo, S.R.; Delfín, I.A.; Hernández, A.M.; Cruz, F.C.; Caamal, E.M.; Monsalve, C.R.; Andrade, S.I.; Córdova, E.; Arellano, E.R.; Soberón, X.; Villalpando, M.E.G.; Monroe, K.; Wilkens, L.; Kolonel, L.N.; Le Marchand, L.; Riba, L.; Sánchez, M.L.O.; Guillén, R.R.; Bautista, I.C.; Torres, M.R.; Hernández, L.L.M.; Sáenz, T.; Gómez, D.; Alvirde, U.; Onofrio, R.C.; Brodeur, W.M.; Gage, D.; Murphy, J.; Franklin, J.; Mahan, S.; Ardlie, K.; Crenshaw, A.T.; Winckler, W.; Fennell, T.; MacArthur, D.G.; Altshuler, D.; Florez, J.C.; Haiman, C.A.; Henderson, B.E.; Salinas, C.A.A.; Villalpando, C.G.; Orozco, L.; Luna, T.T.; Abecasis, G.; Almeida, M.; Altshuler, D.; Asimit, J.L.; Atzmon, G.; Barber, M.; Beer, N.L.; Bell, G.I.; Below, J.; Blackwell, T.; Blangero, J.; Boehnke, M.; Bowden, D.W.; Burtt, N.; Chambers, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, P.; Chines, P.S.; Choi, S.; Churchhouse, C.; Cingolani, P.; Cornes, B.K.; Cox, N.; Williams, A.G.D.; Duggirala, R.; Dupuis, J.; Dyer, T.; Feng, S.; Tajes, J.F.; Ferreira, T.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Flannick, J.; Florez, J.; Fontanillas, P.; Frayling, T.M.; Fuchsberger, C.; Gamazon, E.R.; Gaulton, K.; Ghosh, S.; Gloyn, A.; Grossman, R.L.; Grundstad, J.; Hanis, C.; Heath, A.; Highland, H.; Hirokoshi, M.; Huh, I.-S.; Huyghe, J.R.; Ikram, K.; Jablonski, K.A.; Kim, Y.J.; Jun, G.; Kato, N.; Kim, J.; King, C.R.; Kooner, J.; Kwon, M.-S.; Im, H.K.; Laakso, M.; Lam, K.K.-Y.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Lehman, D.M.; Li, H.; Lindgren, C.M.; Liu, X.; Livne, O.E.; Locke, A.E.; Mahajan, A.; Maller, J.B.; Manning, A.K.; Maxwell, T.J.; Mazoure, A.; McCarthy, M.I.; Meigs, J.B.; Min, B.; Mohlke, K.L.; Morris, A.; Musani, S.; Nagai, Y.; Ng, M.C.Y.; Nicolae, D.; Oh, S.; Palmer, N.; Park, T.; Pollin, T.I.; Prokopenko, I.; Reich, D.; Rivas, M.A.; Scott, L.J.; Seielstad, M.; Cho, Y.S.; Tai, E.-S.; Sim, X.; Sladek, R.; Smith, P.; Tachmazidou, I.; Teslovich, T.M.; Torres, J.; Trubetskoy, V.; Willems, S.M.; Williams, A.L.; Wilson, J.G.; Wiltshire, S.; Won, S.; Wood, A.R.; Xu, W.; Teo, Y.Y.; Yoon, J.; Lee, J.-Y.; Zawistowski, M.; Zeggini, E.; Zhang, W.; Zöllner, S. , Rare variants in <i>PPARG</i> with decreased activity in adipocyte differentiation are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 13127–13132. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K.H.; Niu, T.; Ma, Y.; You, N.C.; Song, Y.; Sobel, E.M.; Hsu, Y.H.; Balasubramanian, R.; Qiao, Y.; Tinker, L.; Liu, S. , Common genetic variants in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPARG) and type 2 diabetes risk among Women's Health Initiative postmenopausal women. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2013, 98, E600–E604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sailaja, A.N.; Nanda, N.; Suryanarayana, B.S.; Pal, G.K. , Association of rs2073618 polymorphism and osteoprotegerin levels with hypertension and cardiovascular risks in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Scientific reports 2023, 13, 17451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliewer, S.A.; Forman, B.M.; Blumberg, B.; Ong, E.S.; Borgmeyer, U.; Mangelsdorf, D.J.; Umesono, K.; Evans, R.M. , Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1994, 91, 7355–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tontonoz, P.; Hu, E.; Graves, R.A.; Budavari, A.I.; Spiegelman, B.M. , mPPAR gamma 2: tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes & development 1994, 8, 1224–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ricote, M.; Huang, J.; Fajas, L.; Li, A.; Welch, J.; Najib, J.; Witztum, J.L.; Auwerx, J.; Palinski, W.; Glass, C.K. , Expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in human atherosclerosis and regulation in macrophages by colony stimulating factors and oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 7614–7619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Gao, Y.; Aaron, N.; Qiang, L. , A glimpse of the connection between PPARγ and macrophage. Frontiers in pharmacology 2023, 14, 1254317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, A. , Control of macrophage activation and function by PPARs. Circulation research 2010, 106, 1559–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, H.F.; Thatcher, T.H.; Kottmann, R.M.; Garcia, T.M.; Phipps, R.P.; Sime, P.J. , The Role of PPARs in Lung Fibrosis. PPAR research 2007, 2007, 71323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, C.; Izquierdo, A.; Velagapudi, V.; Vivas, Y.; Velasco, I.; Campbell, M.; Burling, K.; Cava, F.; Ros, M.; Oresic, M.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Medina-Gomez, G. , Accelerated renal disease is associated with the development of metabolic syndrome in a glucolipotoxic mouse model. Disease models & mechanisms 2012, 5, 636–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kökény, G.; Calvier, L.; Hansmann, G. , PPARγ and TGFβ-Major Regulators of Metabolism, Inflammation, and Fibrosis in the Lungs and Kidneys. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszer, T.; Menéndez-Gutiérrez, M.P.; Lefterova, M.I.; Alameda, D.; Núñez, V.; Lazar, M.A.; Fischer, T.; Ricote, M. , Autoimmune kidney disease and impaired engulfment of apoptotic cells in mice with macrophage peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma or retinoid X receptor alpha deficiency. J Immunol 2011, 186, 621–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabshomali, A.; Bazzazzadehgan, S.; Mahdi, F.; Shariat-Madar, Z. , Potential Benefits of Antioxidant Phytochemicals in Type 2 Diabetes. Molecules 2023, 28, 7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, S.; Lu, Y.; Cui, H.; Racanelli, A.C.; Zhang, L.; Ye, T.; Ding, B.; Zhang, B.; Yang, J.; Yao, Y. , Targeting fibrosis: mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R.; Birerdinc, A.; Younossi, Z.M. , Host Genetic Variants in Obesity-Related Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clinics in liver disease 2014, 18, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, R.K.; Chatterjee, V.K.K.; O’Rahilly, S. , PPARγ and human metabolic disease. The Journal of clinical investigation 2006, 116, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majithia, A.R.; Flannick, J.; Shahinian, P.; Guo, M.; Bray, M.A.; Fontanillas, P.; Gabriel, S.B.; Rosen, E.D.; Altshuler, D. , Rare variants in PPARG with decreased activity in adipocyte differentiation are associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 13127–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhangi, N.; Sharifi, F.; Hashemian, L.; Hassani Doabsari, M.; Heshmatzad, K.; Rahbaran, M.; Jamaldini, S.H.; Aghaei Meybodi, H.R.; Hasanzad, M. , PPARG (Pro12Ala) genetic variant and risk of T2DM: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 12764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; He, C.; Nie, H.; Pang, Q.; Wang, R.; Zeng, Z.; Song, Y. , G Allele of the rs1801282 Polymorphism in PPARgamma Gene Confers an Increased Risk of Obesity and Hypercholesterolemia, While T Allele of the rs3856806 Polymorphism Displays a Protective Role Against Dyslipidemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in endocrinology 2022, 13, 919087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, R.G.; Korman, B.D.; Allanore, Y.; Dieude, P.; Armstrong, L.L.; Rzhetskaya, M.; Hinchcliff, M.; Carns, M.; Podlusky, S.; Shah, S.J.; Ruiz, B.; Hachulla, E.; Tiev, K.; Cracowski, J.-L.; Varga, J.; Hayes, M.G. , A candidate gene study reveals association between a variant of the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPAR-γ) gene and systemic sclerosis. Arthritis research & therapy 2015, 17, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, R.; Davis, A.; Verma, V. , Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young: Rapid Evidence Review. American family physician 2022, 105, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Lemelman, M.B.; Letourneau, L.; Greeley, S.A.W. , Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus: An Update on Diagnosis and Management. Clinics in perinatology 2018, 45, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroso, I.; Luan, J.; Middelberg, R.P.; Harding, A.H.; Franks, P.W.; Jakes, R.W.; Clayton, D.; Schafer, A.J.; O'Rahilly, S.; Wareham, N.J. , Candidate gene association study in type 2 diabetes indicates a role for genes involved in beta-cell function as well as insulin action. PLoS biology 2003, 1, E20. [Google Scholar]

- Gloyn, A.L.; Weedon, M.N.; Owen, K.R.; Turner, M.J.; Knight, B.A.; Hitman, G.; Walker, M.; Levy, J.C.; Sampson, M.; Halford, S.; McCarthy, M.I.; Hattersley, A.T.; Frayling, T.M. , Large-scale association studies of variants in genes encoding the pancreatic beta-cell KATP channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) confirm that the KCNJ11 E23K variant is associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2003, 52, 568–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajans, S.S.; Bell, G.I. , MODY: History, genetics, pathophysiology, and clinical decision making. Diabetes care 2011, 34, 1878–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanabalasingham, G.; Pal, A.; Selwood, M.P.; Dudley, C.; Fisher, K.; Bingley, P.J.; Ellard, S.; Farmer, A.J.; McCarthy, M.I.; Owen, K.R. , Systematic assessment of etiology in adults with a clinical diagnosis of young-onset type 2 diabetes is a successful strategy for identifying maturity-onset diabetes of the young. Diabetes care 2012, 35, 1206–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajans, S.S.; Bell, G.I.; Paz, V.P.; Below, J.E.; Cox, N.J.; Martin, C.; Thomas, I.H.; Chen, M. , Obesity and hyperinsulinemia in a family with pancreatic agenesis and MODY caused by the IPF1 mutation Pro63fsX60. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine 2010, 156, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, R.B. , Mild familial diabetes with dominant inheritance. Q J Med 1974, 43, 339–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, B.M.; Hicks, S.; Shepherd, M.H.; Colclough, K.; Hattersley, A.T.; Ellard, S. , Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY): how many cases are we missing? Diabetologia 2010, 53, 2504–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffel, M.; Duncan, S.A. , The maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY1) transcription factor HNF4alpha regulates expression of genes required for glucose transport and metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1997, 94, 13209–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavvoura, F.K.; Owen, K.R. , Maturity onset diabetes of the young: clinical characteristics, diagnosis and management. Pediatric endocrinology reviews : PER 2012, 10, 234–42. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.; Bescos, M.; Velho, G.; Chevre, J.; Vidal, J.; Sesmilo, G.; Bellanne-Chantelot, C.; Froguel, P.; Casamitjana, R.; Rivera-Fillat, F. , Genetic and clinical characterisation of maturity-onset diabetes of the young in Spanish families. European journal of endocrinology 2000, 142, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voight, B.F.; Scott, L.J.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Morris, A.P.; Dina, C.; Welch, R.P.; Zeggini, E.; Huth, C.; Aulchenko, Y.S.; Thorleifsson, G. , Twelve type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci identified through large-scale association analysis. Nature genetics 2010, 42, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, H.; Inanobe, A.; Furutani, K.; Murakami, S.; Findlay, I.; Kurachi, Y. , Inwardly Rectifying Potassium Channels: Their Structure, Function, and Physiological Roles. Physiological reviews 2010, 90, 291–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTaggart, J.S.; Clark, R.H.; Ashcroft, F.M. , The role of the KATP channel in glucose homeostasis in health and disease: more than meets the islet. The Journal of physiology 2010, (Pt 17) Pt 17, 3201–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloyn, A.L.; Diatloff-Zito, C.; Edghill, E.L.; Bellanné-Chantelot, C.; Nivot, S.; Coutant, R.; Ellard, S.; Hattersley, A.T.; Robert, J.J. , KCNJ11 activating mutations are associated with developmental delay, epilepsy and neonatal diabetes syndrome and other neurological features. European Journal of Human Genetics 2006, 14, 824–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edghill, E.L.; Gloyn, A.L.; Goriely, A.; Harries, L.W.; Flanagan, S.E.; Rankin, J.; Hattersley, A.T.; Ellard, S. , Origin of de Novo KCNJ11 Mutations and Risk of Neonatal Diabetes for Subsequent Siblings. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2007, 92, 1773–1777. [Google Scholar]

- Phani, N.M.; Guddattu, V.; Bellampalli, R.; Seenappa, V.; Adhikari, P.; Nagri, S.K.; D′Souza, S.C.; Mundyat, G.P.; Satyamoorthy, K.; Rai, P.S. , Population Specific Impact of Genetic Variants in KCNJ11 Gene to Type 2 Diabetes: A Case-Control and Meta-Analysis Study. PloS one 2014, 9, e107021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Blanco, H.L.; Villarreal-Perez, J.Z.; Cerda-Flores, R.M.; Figueroa, A.; Sanchez-Dominguez, C.N.; Gutierrez-Valverde, J.M.; Torres-Muñoz, I.C.; Lavalle-Gonzalez, F.J.; Gallegos-Cabriales, E.C.; Martinez-Garza, L.E. , Genetic variants in KCNJ11, TCF7L2 and HNF4A are associated with type 2 diabetes, BMI and dyslipidemia in families of Northeastern Mexico: A pilot study. Experimental and therapeutic medicine 2017, 13, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javorsky, M.; Klimcakova, L.; Schroner, Z.; Zidzik, J.; Babjakova, E.; Fabianova, M.; Kozarova, M.; Tkacova, R.; Salagovic, J.; Tkac, I. , KCNJ11 gene E23K variant and therapeutic response to sulfonylureas. European journal of internal medicine 2012, 23, 245–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, Y.; Inoue, H.; Keshavarz, P.; Miyawaki, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Moritani, M.; Kunika, K.; Nakamura, N.; Yoshikawa, T.; Yasui, N.; Shiota, H.; Tanahashi, T.; Itakura, M. , SNPs in the KCNJ11-ABCC8 gene locus are associated with type 2 diabetes and blood pressure levels in the Japanese population. Journal of human genetics 2007, 52, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, B.K.; Cho, Y.M.; Park, B.L.; Cheong, H.S.; Shin, H.D.; Jang, H.C.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, H.K.; Park, K.S. , Polymorphisms of KCNJ11 (Kir6.2 gene) are associated with Type 2 diabetes and hypertension in the Korean population. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association 2007, 24, 178–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam-Jazi, M.; Najd-Hassan-Bonab, L.; Masjoudi, S.; Tohidi, M.; Hedayati, M.; Azizi, F.; Daneshpour, M.S. , Risk of type 2 diabetes and KCNJ11 gene polymorphisms: a nested case-control study and meta-analysis. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 20709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Li, Q.; Gao, S. , Meta-analysis of the relationship between common type 2 diabetes risk gene variants with gestational diabetes mellitus. PloS one 2012, 7, e45882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauenborg, J.; Grarup, N.; Damm, P.; Borch-Johnsen, K.; Jørgensen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Hansen, T. , Common type 2 diabetes risk gene variants associate with gestational diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2009, 94, 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Majcher, S.; Ustianowski, P.; Malinowski, D.; Czerewaty, M.; Tarnowski, M.; Safranow, K.; Dziedziejko, V.; Pawlik, A. , KCNJ11 and KCNQ1 Gene Polymorphisms and Placental Expression in Women with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Genes 2022, 13, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.; Na, R.; Xu, R.; Wang, S.; Sheng, H.; Wu, W.; Qu, Y. , Quantitative assessment of the effect of KCNJ11 gene polymorphism on the risk of type 2 diabetes. PloS one 2014, 9, e93961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muftin, N.Q.; Jubair, S. , KCNJ11 polymorphism is associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Iraqi patients. Gene Reports 2019, 17, 100480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, P.; Habibipour, R.; Ghasemi, M.; Kazemnezhad, E.; Alizadeh, M.; Omami, M.H. , Lack of genetic susceptibility of KCNJ11 E23K polymorphism with risk of type 2 diabetes in an Iranian population. Endocrine research 2014, 39, 120–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhzoom, O.; Kabalan, Y.; Al-Quobaili, F. , Association of KCNJ11 rs5219 gene polymorphism with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a population of Syria: a case-control study. BMC medical genetics 2019, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; He, L. , The E23K variation in the KCNJ11 gene is associated with type 2 diabetes in Chinese and East Asian population. Journal of human genetics 2009, 54, 433–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonen, M.S.; Arikoglu, H.; Erkoc Kaya, D.; Ozdemir, H.; Ipekci, S.H.; Arslan, A.; Kayis, S.A.; Gogebakan, B. , Effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms in K(ATP) channel genes on type 2 diabetes in a Turkish population. Archives of medical research 2012, 43, 317–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzehery, R.; El-Hafez, H.A.; Elsehely, I.; Barakat, A.; Foda, E.A.E.; Hendawy, S.R.; Gameil, M.A.; Nada, H.S.; El-Sebaie, A. , Association of the E23K (rs5219) polymorphism in the potassium channel (KCNJ11) gene with diabetic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes. Gene 2024, 921, 148525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorokhova, P.; Baranov, V.; Vorokhobina, N. , Abstract #1001320: Effects of KCNJ11 RS5219 Variant on Metformin Pharmacodynamics in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrine Practice 2021, 27, S39. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Elsadek, H.M.; Shalaby, S.M.; Elnahas, H.M. , Association of SLC22A1, SLC47A1, and KCNJ11 polymorphisms with efficacy and safety of metformin and sulfonylurea combination therapy in Egyptian patients with type 2 diabetes. Research in pharmaceutical sciences 2023, 18, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, X.; Fang, Y.A.O.; Limin, J.I.N.; Fan, N.; Hanqiang, S.H.I.; Shuqin, D.U.; Yanbo, S.H.I. , Study of <i>KCNJ11</i> rs5219 Gene Polymorphism on the Efficacy of Metformin Combined with Gliclazide in Newly Diagnosed Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 Patients. Chinese Journal of Modern Applied Pharmacy 2023, 40, 3431–3438. [Google Scholar]

- Sesti, G.; Laratta, E.; Cardellini, M.; Andreozzi, F.; Del Guerra, S.; Irace, C.; Gnasso, A.; Grupillo, M.; Lauro, R.; Hribal, M.L.; Perticone, F.; Marchetti, P. , The E23K Variant of KCNJ11 Encoding the Pancreatic β-Cell Adenosine 5′-Triphosphate-Sensitive Potassium Channel Subunit Kir6.2 Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Secondary Failure to Sulfonylurea in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2006, 91, 2334–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis, J.; Langenberg, C.; Prokopenko, I.; Saxena, R.; Soranzo, N.; Jackson, A.U.; Wheeler, E.; Glazer, N.L.; Bouatia-Naji, N.; Gloyn, A.L.; Lindgren, C.M.; Mägi, R.; Morris, A.P.; Randall, J.; Johnson, T.; Elliott, P.; Rybin, D.; Thorleifsson, G.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Henneman, P.; Grallert, H.; Dehghan, A.; Hottenga, J.J.; Franklin, C.S.; Navarro, P.; Song, K.; Goel, A.; Perry, J.R.; Egan, J.M.; Lajunen, T.; Grarup, N.; Sparsø, T.; Doney, A.; Voight, B.F.; Stringham, H.M.; Li, M.; Kanoni, S.; Shrader, P.; Cavalcanti-Proença, C.; Kumari, M.; Qi, L.; Timpson, N.J.; Gieger, C.; Zabena, C.; Rocheleau, G.; Ingelsson, E.; An, P.; O'Connell, J.; Luan, J.; Elliott, A.; McCarroll, S.A.; Payne, F.; Roccasecca, R.M.; Pattou, F.; Sethupathy, P.; Ardlie, K.; Ariyurek, Y.; Balkau, B.; Barter, P.; Beilby, J.P.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Benediktsson, R.; Bennett, A.J.; Bergmann, S.; Bochud, M.; Boerwinkle, E.; Bonnefond, A.; Bonnycastle, L.L.; Borch-Johnsen, K.; Böttcher, Y.; Brunner, E.; Bumpstead, S.J.; Charpentier, G.; Chen, Y.D.; Chines, P.; Clarke, R.; Coin, L.J.; Cooper, M.N.; Cornelis, M.; Crawford, G.; Crisponi, L.; Day, I.N.; de Geus, E.J.; Delplanque, J.; Dina, C.; Erdos, M.R.; Fedson, A.C.; Fischer-Rosinsky, A.; Forouhi, N.G.; Fox, C.S.; Frants, R.; Franzosi, M.G.; Galan, P.; Goodarzi, M.O.; Graessler, J.; Groves, C.J.; Grundy, S.; Gwilliam, R.; Gyllensten, U.; Hadjadj, S.; Hallmans, G.; Hammond, N.; Han, X.; Hartikainen, A.L.; Hassanali, N.; Hayward, C.; Heath, S.C.; Hercberg, S.; Herder, C.; Hicks, A.A.; Hillman, D.R.; Hingorani, A.D.; Hofman, A.; Hui, J.; Hung, J.; Isomaa, B.; Johnson, P.R.; Jørgensen, T.; Jula, A.; Kaakinen, M.; Kaprio, J.; Kesaniemi, Y.A.; Kivimaki, M.; Knight, B.; Koskinen, S.; Kovacs, P.; Kyvik, K.O.; Lathrop, G.M.; Lawlor, D.A.; Le Bacquer, O.; Lecoeur, C.; Li, Y.; Lyssenko, V.; Mahley, R.; Mangino, M.; Manning, A.K.; Martínez-Larrad, M.T.; McAteer, J.B.; McCulloch, L.J.; McPherson, R.; Meisinger, C.; Melzer, D.; Meyre, D.; Mitchell, B.D.; Morken, M.A.; Mukherjee, S.; Naitza, S.; Narisu, N.; Neville, M.J.; Oostra, B.A.; Orrù, M.; Pakyz, R.; Palmer, C.N.; Paolisso, G.; Pattaro, C.; Pearson, D.; Peden, J.F.; Pedersen, N.L.; Perola, M.; Pfeiffer, A.F.; Pichler, I.; Polasek, O.; Posthuma, D.; Potter, S.C.; Pouta, A.; Province, M.A.; Psaty, B.M.; Rathmann, W.; Rayner, N.W.; Rice, K.; Ripatti, S.; Rivadeneira, F.; Roden, M.; Rolandsson, O.; Sandbaek, A.; Sandhu, M.; Sanna, S.; Sayer, A.A.; Scheet, P.; Scott, L.J.; Seedorf, U.; Sharp, S.J.; Shields, B.; Sigurethsson, G.; Sijbrands, E.J.; Silveira, A.; Simpson, L.; Singleton, A.; Smith, N.L.; Sovio, U.; Swift, A.; Syddall, H.; Syvänen, A.C.; Tanaka, T.; Thorand, B.; Tichet, J.; Tönjes, A.; Tuomi, T.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; van Dijk, K.W.; van Hoek, M.; Varma, D.; Visvikis-Siest, S.; Vitart, V.; Vogelzangs, N.; Waeber, G.; Wagner, P.J.; Walley, A.; Walters, G.B.; Ward, K.L.; Watkins, H.; Weedon, M.N.; Wild, S.H.; Willemsen, G.; Witteman, J.C.; Yarnell, J.W.; Zeggini, E.; Zelenika, D.; Zethelius, B.; Zhai, G.; Zhao, J.H.; Zillikens, M.C.; Borecki, I.B.; Loos, R.J.; Meneton, P.; Magnusson, P.K.; Nathan, D.M.; Williams, G.H.; Hattersley, A.T.; Silander, K.; Salomaa, V.; Smith, G.D.; Bornstein, S.R.; Schwarz, P.; Spranger, J.; Karpe, F.; Shuldiner, A.R.; Cooper, C.; Dedoussis, G.V.; Serrano-Ríos, M.; Morris, A.D.; Lind, L.; Palmer, L.J.; Hu, F.B.; Franks, P.W.; Ebrahim, S.; Marmot, M.; Kao, W.H.; Pankow, J.S.; Sampson, M.J.; Kuusisto, J.; Laakso, M.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Wichmann, H.E.; Illig, T.; Rudan, I.; Wright, A.F.; Stumvoll, M.; Campbell, H.; Wilson, J.F.; Bergman, R.N.; Buchanan, T.A.; Collins, F.S.; Mohlke, K.L.; Tuomilehto, J.; Valle, T.T.; Altshuler, D.; Rotter, J.I.; Siscovick, D.S.; Penninx, B.W.; Boomsma, D.I.; Deloukas, P.; Spector, T.D.; Frayling, T.M.; Ferrucci, L.; Kong, A.; Thorsteinsdottir, U.; Stefansson, K.; van Duijn, C.M.; Aulchenko, Y.S.; Cao, A.; Scuteri, A.; Schlessinger, D.; Uda, M.; Ruokonen, A.; Jarvelin, M.R.; Waterworth, D.M.; Vollenweider, P.; Peltonen, L.; Mooser, V.; Abecasis, G.R.; Wareham, N.J.; Sladek, R.; Froguel, P.; Watanabe, R.M.; Meigs, J.B.; Groop, L.; Boehnke, M.; McCarthy, M.I.; Florez, J.C.; Barroso, I. , New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nature genetics 2010, 42, 105–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chang, B.H.; Samson, S.L.; Li, M.V.; Chan, L. , The Krüppel-like zinc finger protein Glis3 directly and indirectly activates insulin gene transcription. Nucleic acids research 2009, 37, 2529–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chan, L. , Monogenic Diabetes: What It Teaches Us on the Common Forms of Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrine reviews 2016, 37, 190–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; ZeRuth, G.; Lichti-Kaiser, K.; Vasanth, S.; Yin, Z.; Kim, Y.S.; Jetten, A.M. , Gli-similar (Glis) Krüppel-like zinc finger proteins: insights into their physiological functions and critical roles in neonatal diabetes and cystic renal disease. Histology and histopathology 2010, 25, 1481–96. [Google Scholar]

- London, S.; De Franco, E.; Elias-Assad, G.; Barhoum, M.N.; Felszer, C.; Paniakov, M.; Weiner, S.A.; Tenenbaum-Rakover, Y. , Case Report: Neonatal Diabetes Mellitus Caused by a Novel GLIS3 Mutation in Twins. Frontiers in endocrinology 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, K.; Chetty, R. , Gene of the month: GLIS1-3. Journal of clinical pathology 2020, 73, 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.S.; Kim, Y.S.; ZeRuth, G.; Beak, J.Y.; Gerrish, K.; Kilic, G.; Sosa-Pineda, B.; Jensen, J.; Pierreux, C.E.; Lemaigre, F.P.; Foley, J.; Jetten, A.M. , Transcription factor Glis3, a novel critical player in the regulation of pancreatic beta-cell development and insulin gene expression. Molecular and cellular biology 2009, 29, 6366–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scoville, D.W.; Jetten, A.M. , GLIS3: A Critical Transcription Factor in Islet β-Cell Generation. Cells 2021, 10, 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franco, E.; Flanagan, S.E.; Houghton, J.A.L.; Allen, H.L.; Mackay, D.J.G.; Temple, I.K.; Ellard, S.; Hattersley, A.T. , The effect of early, comprehensive genomic testing on clinical care in neonatal diabetes: an international cohort study. The Lancet 2015, 386, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, T.C.; Paula, F.M.; Villate, O.; Colli, M.L.; Moura, R.F.; Cunha, D.A.; Marselli, L.; Marchetti, P.; Cnop, M.; Julier, C.; Eizirik, D.L. , GLIS3, a Susceptibility Gene for Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes, Modulates Pancreatic Beta Cell Apoptosis via Regulation of a Splice Variant of the BH3-Only Protein Bim. PLoS genetics 2013, 9, e1003532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Have, C.T.; Hollensted, M.; Grarup, N.; Linneberg, A.; Pedersen, O.; Nielsen, J.S.; Rungby, J.; Christensen, C.; Brandslund, I.; Kristiansen, K.; Jun, W.; Hansen, T.; Gjesing, A.P. , Sequencing reveals protective and pathogenic effects on development of diabetes of rare GLIS3 variants. PloS one 2019, 14, e0220805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhtshneider, E.V.; Mikhailova, S.V.; Ivanoshchuk, D.E.; Orlov, P.S.; Ovsyannikova, A.K.; Rymar, O.D.; Ragino, Y.I.; Voevoda, M.I. , Polymorphism of the GLIS3 gene in a Caucasian population and among individuals with carbohydrate metabolism disorders in Russia. BMC research notes 2018, 11, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, R.V.; Sinha, M.K.; Heiman, M.L.; Kriauciunas, A.; Stephens, T.W.; Nyce, M.R.; Ohannesian, J.P.; Marco, C.C.; McKee, L.J.; Bauer, T.L. , Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. New England Journal of Medicine 1996, 334, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Herrera, K.; Florio, A.A.; Moore, M.; Marrero, A.; Tamez, M.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Mattei, J. , The Leptin System and Diet: A Mini Review of the Current Evidence. Frontiers in endocrinology 2021, 12, 749050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigle, D.S.; Breen, P.A.; Matthys, C.C.; Callahan, H.S.; Meeuws, K.E.; Burden, V.R.; Purnell, J.Q. , A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2005, 82, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsiki, N.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Banach, M. , Leptin, cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2018, 39, 1176–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, I.S.; Jebb, S.A.; Langmack, G.; Lawrence, E.; Cheetham, C.H.; Prentice, A.M.; Hughes, I.A.; McCamish, M.A.; O'Rahilly, S. , Effects of Recombinant Leptin Therapy in a Child with Congenital Leptin Deficiency. New England Journal of Medicine 1999, 341, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

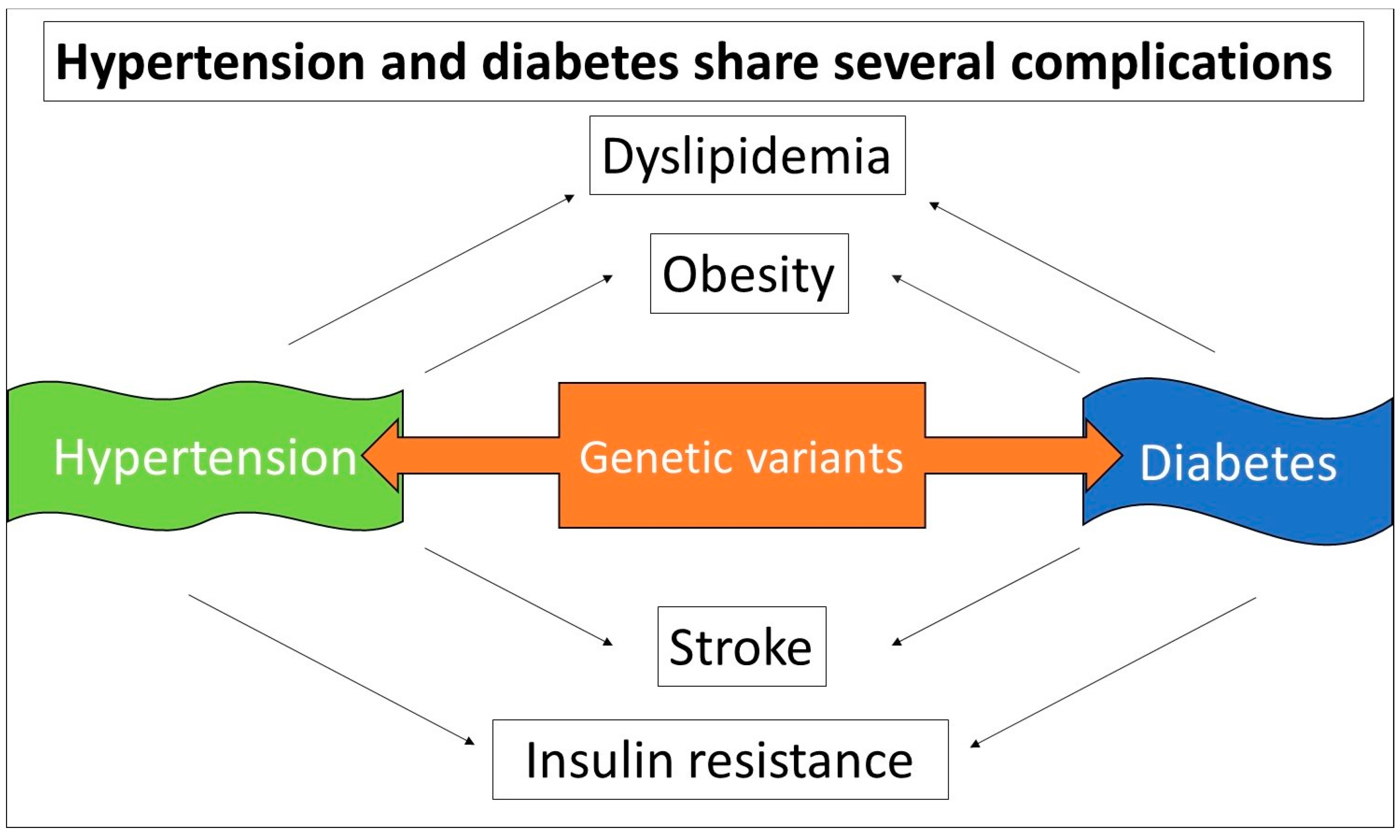

- Padmanabhan, S.; Dominiczak, A.F. , Genomics of hypertension: the road to precision medicine. Nature reviews. Cardiology 2021, 18, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.N. , Genetic and Epigenetic Mechanisms Regulating Blood Pressure and Kidney Dysfunction. Hypertension 2024, 81, 1424–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmot, E.; Idris, I. , Early onset type 2 diabetes: risk factors, clinical impact and management. Therapeutic advances in chronic disease 2014, 5, 234–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Forman, J.P.; Jensen, M.K.; Flint, A.; Curhan, G.C.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B.; Qi, L. , Genetic predisposition to high blood pressure associates with cardiovascular complications among patients with type 2 diabetes: two independent studies. Diabetes 2012, 61, 3026–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, J.R.; Guzik, T.J.; Touyz, R.M. , Diabetes, Hypertension, and Cardiovascular Disease: Clinical Insights and Vascular Mechanisms. The Canadian journal of cardiology 2018, 34, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoily, S.S.; Ahsan, T.; Fatema, K.; Sajib, A.A. , Common genetic variants and pathways in diabetes and associated complications and vulnerability of populations with different ethnic origins. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Shu, Y.; Cai, Y.D. , Genetic differences among ethnic groups. BMC genomics 2015, 16, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, E.; Forde, H.; Davenport, C.; Rochfort, K.D.; Smith, D.; Cummins, P.M. , Vascular calcification in type-2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Integrative roles for OPG, RANKL and TRAIL. Vascular pharmacology 2016, 82, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalra, S.S.; Shanahan, C.M. , Vascular calcification and hypertension: cause and effect. Annals of medicine 2012, 44 Suppl 1, S85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Tu, P.; Si, L.; Hu, W.; Liu, M.; Liu, J.; Xue, Y. , Gene Polymorphisms in the RANKL/RANK/OPG Pathway Are Associated with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Southern Han Chinese Women. Genetic testing and molecular biomarkers 2016, 20, 285–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahagi, K.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Lutter, C.; Mori, H.; Romero, M.E.; Finn, A.V.; Virmani, R. , Pathology of Human Coronary and Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis and Vascular Calcification in Diabetes Mellitus. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2017, 37, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamimura, D.; Suzuki, T.; Furniss, A.L.; Griswold, M.E.; Kullo, I.J.; Lindsey, M.L.; Winniford, M.D.; Butler, K.R.; Mosley, T.H.; Hall, M.E. , Elevated serum osteoprotegerin is associated with increased left ventricular mass index and myocardial stiffness. Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine 2017, 18, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazquez-Medela, A.M.; Garcia-Ortiz, L.; Gomez-Marcos, M.A.; Recio-Rodriguez, J.I.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, A.; Lopez-Novoa, J.M.; Martinez-Salgado, C. , Osteoprotegerin is associated with cardiovascular risk in hypertension and/or diabetes. European journal of clinical investigation 2012, 42, 548–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmine, M.R.; Nanda, N.; Sahoo, J.; Velkumary, S.; Pal, G.K. , Increased osteoprotegerin level is associated with impaired cardiovagal modulation in type-2 diabetic patients treated with oral antidiabetic drugs. BMC cardiovascular disorders 2020, 20, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, A.D.A.P.P., 9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes care 2024, 48, (Supplement_1), S181-S206.

- Lemkes, B.A.; Hermanides, J.; Devries, J.H.; Holleman, F.; Meijers, J.C.; Hoekstra, J.B. , Hyperglycemia: a prothrombotic factor? Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis : JTH 2010, 8, 1663–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.H.; Prior, S.M.; Plens, K.; Konieczynska, M.; Hohendorff, J.; Malecki, M.T.; Butenas, S.; Undas, A. , Predictors of neutrophil extracellular traps markers in type 2 diabetes mellitus: associations with a prothrombotic state and hypofibrinolysis. Cardiovascular diabetology 2019, 18, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salavati, M.; Arabshomali, A.; Nouranian, S.; Shariat-Madar, Z. , Overview of Venous Thromboembolism and Emerging Therapeutic Technologies Based on Nanocarriers-Mediated Drug Delivery Systems. Molecules 2024, 29, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, F.; Adjedj, J.; Varenne, O. , [Diabetes Mellitus, a prothrombotic disease]. Annales de cardiologie et d'angeiologie 2017, 66, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baye, A.M.; Fanta, T.G.; Siddiqui, M.K.; Dawed, A.Y. , The Genetics of Adverse Drug Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in genetics 2021, 12, 675053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altshuler, D.; Hirschhorn, J.N.; Klannemark, M.; Lindgren, C.M.; Vohl, M.C.; Nemesh, J.; Lane, C.R.; Schaffner, S.F.; Bolk, S.; Brewer, C.; Tuomi, T.; Gaudet, D.; Hudson, T.J.; Daly, M.; Groop, L.; Lander, E.S. , The common PPARgamma Pro12Ala polymorphism is associated with decreased risk of type 2 diabetes. Nature genetics 2000, 26, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vella, A. , Pharmacogenetics for type 2 diabetes: practical considerations for study design. Journal of diabetes science and technology 2009, 3, 705–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, A.; Camilleri, M. , Pharmacogenetics: potential role in the treatment of diabetes and obesity. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy 2008, 9, 1109–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Yee, S.W.; Seiser, E.L.; van Leeuwen, N.; Tavendale, R.; Bennett, A.J.; Groves, C.J.; Coleman, R.L.; van der Heijden, A.A.; Beulens, J.W.; de Keyser, C.E.; Zaharenko, L.; Rotroff, D.M.; Out, M.; Jablonski, K.A.; Chen, L.; Javorský, M.; Židzik, J.; Levin, A.M.; Williams, L.K.; Dujic, T.; Semiz, S.; Kubo, M.; Chien, H.-C.; Maeda, S.; Witte, J.S.; Wu, L.; Tkáč, I.; Kooy, A.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Stehouwer, C.D.A.; Logie, L.; Sutherland, C.; Klovins, J.; Pirags, V.; Hofman, A.; Stricker, B.H.; Motsinger-Reif, A.A.; Wagner, M.J.; Innocenti, F.; Hart, L.M. t.; Holman, R.R.; McCarthy, M.I.; Hedderson, M.M.; Palmer, C.N.A.; Florez, J.C.; Giacomini, K.M.; Pearson, E.R.; MetGen, I.; Investigators, D.P.P.; Investigators, A. , Variation in the glucose transporter gene SLC2A2 is associated with glycemic response to metformin. Nature genetics 2016, 48, 1055–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.K.; Padhukasahasram, B.; Ahmedani, B.K.; Peterson, E.L.; Wells, K.E.; González Burchard, E.; Lanfear, D.E. , Differing effects of metformin on glycemic control by race-ethnicity. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 2014, 99, 3160–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- www.who.int/nutrition/topics/obesity/en.

- Fruh, S.M. , Obesity: Risk factors, complications, and strategies for sustainable long-term weight management. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 2017, (S1), S3–s14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.-P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; St-Onge, M.-P.; Lifestyle, O. b. o. t. A. H. A. C. o.; Health, C.; Cardiovascular, C. o.; Nursing, S.; Cardiology, C. o. C.; Epidemiology, C. o.; Prevention; Council, S. , Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, H. , Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Frontiers in endocrinology 2021, 12, 706978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini, J.; Ahangari, R.; Miller, C.; Samsam, M. , Chapter 18 - Perspective on economics and obesity. In Global Health Complications of Obesity, Moini, J.; Ahangari, R.; Miller, C.; Samsam, M., Eds. Elsevier: 2020; pp 411-423.

- Evans, M.; de Courcy, J.; de Laguiche, E.; Faurby, M.; Haase, C.L.; Matthiessen, K.S.; Moore, A.; Pearson-Stuttard, J. , Obesity-related complications, healthcare resource use and weight loss strategies in six European countries: the RESOURCE survey. International Journal of Obesity 2023, 47, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, D.W.; James, W.P. , Obesity. Lancet 2005, 366, 1197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, B.B.; Flier, J.S. , Obesity and insulin resistance. The Journal of clinical investigation 2000, 106, 473–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewens, K.G.; Jones, M.R.; Ankener, W.; Stewart, D.R.; Urbanek, M.; Dunaif, A.; Legro, R.S.; Chua, A.; Azziz, R.; Spielman, R.S.; Goodarzi, M.O.; Strauss, J.F. , 3rd, FTO and MC4R gene variants are associated with obesity in polycystic ovary syndrome. PloS one 2011, 6, e16390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, P.; Lipowska, A.; Rys, P.; Ewens, K.G.; Franks, S.; Tan, S.; Lerchbaum, E.; Vcelak, J.; Attaoua, R.; Straczkowski, M.; Azziz, R.; Barber, T.M.; Hinney, A.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Lukasova, P.; Bendlova, B.; Grigorescu, F.; Kowalska, I.; Goodarzi, M.O.; Consortium, G.; Strauss, J.F., 3rd; McCarthy, M.I.; Malecki, M.T. , Impact of FTO genotypes on BMI and weight in polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 2636–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauchi, S.; Stutzmann, F.; Cavalcanti-Proenca, C.; Durand, E.; Pouta, A.; Hartikainen, A.L.; Marre, M.; Vol, S.; Tammelin, T.; Laitinen, J.; Gonzalez-Izquierdo, A.; Blakemore, A.I.; Elliott, P.; Meyre, D.; Balkau, B.; Jarvelin, M.R.; Froguel, P. , Combined effects of MC4R and FTO common genetic variants on obesity in European general populations. J Mol Med (Berl) 2009, 87, 537–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, J.J.; Orlando, R.A.; Garver, W.S. , Gene-nutrient interactions and susceptibility to human obesity. Genes & nutrition 2017, 12, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Trang, K.; Grant, S.F.A. , Genetics and epigenetics in the obesity phenotyping scenario. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders 2023, 24, 775–793. [Google Scholar]

- Lalle, G.; Lautraite, R.; Bouherrou, K.; Plaschka, M.; Pignata, A.; Voisin, A.; Twardowski, J.; Perrin-Niquet, M.; Stéphan, P.; Durget, S.; Tonon, L.; Ardin, M.; Degletagne, C.; Viari, A.; Belgarbi Dutron, L.; Davoust, N.; Postler, T.S.; Zhao, J.; Caux, C.; Caramel, J.; Dalle, S.; Cassier, P.A.; Klein, U.; Schmidt-Supprian, M.; Liblau, R.; Ghosh, S.; Grinberg-Bleyer, Y. , NF-κB subunits RelA and c-Rel selectively control CD4+ T cell function in multiple sclerosis and cancer. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2024, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Osta, A.; Brasacchio, D.; Yao, D.; Pocai, A.; Jones, P.L.; Roeder, R.G.; Cooper, M.E.; Brownlee, M. , Transient high glucose causes persistent epigenetic changes and altered gene expression during subsequent normoglycemia. The Journal of experimental medicine 2008, 205, 2409–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, W.; Wang, X. , Studies on the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene and its impact on obesity-associated diseases. Genes Dis 2023, 10, 2351–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saqlain, M.; Khalid, M.; Fiaz, M.; Saeed, S.; Mehmood Raja, A.; Mobeen Zafar, M.; Fatima, T.; Bosco Pesquero, J.; Maglio, C.; Valadi, H.; Nawaz, M.; Kaukab Raja, G. , Risk variants of obesity associated genes demonstrate BMI raising effect in a large cohort. PloS one 2022, 17, e0274904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegretti, A.S.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, W.; Thurber, T.K.; Rigby, S.P.; Bowman-Stroud, C.; Trescoli, C.; Serusclat, P.; Freeman, M.W.; Halvorsen, Y.C. , Safety and Effectiveness of Bexagliflozin in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Stage 3a/3b CKD. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation 2019, 74, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, R.L.; Gallo, G.; Le, K.-P. N.; Volino, L.R. , Bexagliflozin: a comprehensive review of a recently approved SGLT2 inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Medicinal Chemistry Research 2024, 33, 1354–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauck, M.A.; D‘Alessio, D.A. , Tirzepatide, a dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor co-agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes with unmatched effectiveness regrading glycaemic control and body weight reduction. Cardiovascular diabetology 2022, 21, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirzepatide (Mounjaro) for type 2 diabetes. The Medical letter on drugs and therapeutics 2022, 64, 105–107.

- Dutta, P.; Kumar, Y.; Babu, A.T.; Giri Ravindran, S.; Salam, A.; Rai, B.; Baskar, A.; Dhawan, A.; Jomy, M. , Tirzepatide: A Promising Drug for Type 2 Diabetes and Beyond. Cureus 2023, 15, e38379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Costello, R.A., Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists. In StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing.

- Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.: Treasure Island (FL), 2024.

- Frampton, J.E. , Finerenone: First Approval. Drugs 2021, 81, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Mesa, J.S.; White, A.; Ahmadian-Tehrani, A.; Anderson, A.S. , Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists: a Comprehensive Review of Finerenone. Current cardiology reports 2020, 22, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Vasco, M.A.; Fantaye, S.H.; Raghunathan, S.; Solis-Herrera, C. , The potential role of finerenone in patients with type 1 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2024, 26, 4135–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AstraZeneca. Study of BMS-477118 as Monotherapy With Titration in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Who Are Not Controlled With Diet and Exercise. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00316082?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=9&page=1&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- AstraZeneca. A Phase 3 Study of BMS-477118 in Combination With Metformin in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Who Are Not Controlled With Diet and Exercise. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00327015?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=14&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- AstraZeneca. A Pilot Study of BMS-512148 in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00357370?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=3. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- AstraZeneca. A Study of BMS-512148 (Dapagliflozin) in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes With Inadequately Controlled Hypertension on an ACEI or ARB and an Additional Antihypertensive Medication. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01195662?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=13&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Cadila Pharnmaceuticals. Effect of CPL-2009-0031 in the Treatment of Patients With Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04801199?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=1. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- University of Florida. Effect of a Basal/Pre-Meal Insulin Strategy (Detemir/Aspart) on Insulin Secretion and Action in Type 2 Diabetes. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00998335?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=24&page=3&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Soo Lim. Effect of Ertugliflozin on Cardiac Function in Diabetes (ERTU-GLS). ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online:https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03717194?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=2. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Weill Medical College of Cornell University. Efficacy of Exenatide-LAR and Dapagliflozin in Overweight/Obese, Insulin Treated Patients With Type 2 Diabetes (Dexlar). ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02811484?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=6. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Medical University of Vienna. Effects of Combined Dapagliflozin and Exenatide Versus Dapagliflozin and Placebo on Ectopic Lipids in Patients With Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. (EXENDA). ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03007329?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=17&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Ross, S.A.; Caballero, A.E.; Del Prato, S.; Gallwitz, B.; Lewis-D'Agostino, D.; Bailes, Z.; Thiemann, S.; Patel, S.; Woerle, H.J.; von Eynatten, M. , Linagliptin plus metformin in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes and marked hyperglycemia. Postgraduate medicine 2016, 128, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehringer Ingelheim. Linagliptin and Metformin Versus Linagliptin in Newly Diagnosed, Untreated Type 2 Diabetes. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT01512979?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=27&page=3&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Roger New. Study to Evaluate the Safety and Efficacy of Oral Insulin Formulation in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Subjects. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06473662?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=15&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Pfizer. Trial to Learn About the Study Medicine (PF-07081532) and Rybelsus in People With Type 2 Diabetes and Separately PF-07081532 in People With Obesity. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05579977?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=20&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- AstraZeneca. A Study Assessing Saxagliptin Treatment in Type 2 Diabetic Subjects Who Are Not Controlled With TZD Therapy Alone. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00295633?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=12&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- AstraZeneca. Study Assessing Saxagliptin Treatment In Type 2 Diabetic Subjects Who Are Not Controlled With Metformin Alone. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00121667?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=19&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- AstraZeneca. Study Assessing Saxagliptin Treatment in Subjects With Type 2 Diabetes Who Are Not Controlled With Diet and Exercise. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00374907?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=21&page=3&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Sanofi. Effect of Soliqua 100/33 on Time in Range From Continuous Glucose Monitoring in Insulin-naive Patients With Very Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (Soli-CGM). ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05114590?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=4. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Safety and Efficacy of Vildagliptin vs. Thiazolidinedione as add-on Therapy to Metformin in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Not Controlled With Metformin Alone. ClinicalTrials.Gov. [];2024 Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT00396227?term=New%20Antidiabetic%20Drugs,%20uncontrolled%20diabetes&rank=11&page=2&limit=10. (accessed on 10 December 2024).

|

Genes |

Major function |

Mutations or variants associated with T2DM |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABCC8 | Encodes regulatory SUR1 subunits | R1420H, rare occurrence in adult | [34,35] |

| GLIS3 | A transcription factor: Regulator of islet development, insulin gene transcription, and obesity-induced compensatory β-cell proliferation |

P/LP GLIS3, rs10758593 |

[36,37] |

| HNF4A | Transcription factor for early fetal development | p.Arg114Trp | [38,39,40] |

| KCNJ11 | Encodes pore-forming inwardly-rectifying potassium channel subunits (Kir6.2) | E23K rs5215, rs5218, and rs5219 |

[41,42] |

| LEP | A regulator of appetite and energy balance | rs147287548 | [43] |

| PPAR | A transcription factor: master regulator of adipogenesis, energy balance, lipid biosynthesis, and insulin sensitivity; cellular target of TZDs |

rs4684847 rs1801282 |

[44] [45,46] |

| OPG | A decoy receptor for receptor-activator for NF-B ligand (RANKL) | rs2073618 | [47] |

| Conditions | Medicines | MAO | Outcomes | Side effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2DM | Brenzavvy (bexagliflozin) | A dual agonist for the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptors | Improves hyperglycemia | It may cause ketoacidosis, a serious, potentially life-threatening complication that occurs when the body produces high levels of acids in the blood | It works similarly in Asians, Black or African Americans, and Whites adults |

| T2DM | Mounjaro (tirzepatide) | Improves blood sugar control | It may cause serious side effects including inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis), low blood sugar, allergic reactions, kidney problems (kidney failure), severe stomach problems, and complications of diabetes-related eye disease (diabetic retinopathy) | It works similarly in Asians, Black or African Americans, and Whites adults | |

| CKD associated T2DM | Kerendia (finerenone) | It reduced the risk of kidney failure associated with T2DM, having a heart attack or stroke, being hospitalized for heart failure, and dying from cardiovascular disease | The most common side effects included high potassium levels in the blood (hyperkalemia), low blood pressure (hypotension), and low sodium levels in the blood (hyponatremia). | No notable difference in side effects was observed by racial subgroups. |

|

Conditions |

Compounds |

Mechanism of action |

Clinical outcomes |

Stage |

Trial registration no. |

Sponsor |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2DM | BMS-477118 | DPP-4 inhibitor | Phase 3 | NCT00316082 | AstraZeneca | [170,171] | |

| Diabetes | BMS-512148 (Dapagliflozin) |

A new SGLT2 inhibitor | Phase 2| Phase 3 | NCT00357370 | AstraZeneca | [172,173] | |

| Uncontrolled T2DM | CPL2009-0031 | DPP-4 inhibitor | Phase 3 | NCT04801199 | Cadila Pharnmaceuticals | [174] | |

| Uncontrolled T2DM | Detemir/Aspart | Insulin | Improved glycemic control | Phase 4 | NCT00998335 | University of Florida | [175] |

| Cardiac function in diabetes | Ertugliflozin | A new SGLT2 inhibitor | Phase 3 | NCT03717194 | Soo Lim | [176] | |

| Uncontrolled T2DM | Exenatide-LAR and Dapagliflozin | Insulin secretion/ SGLT2 inhibitor | Improved glycemic control, weight, SBP | Phase 4 | NCT0281184, NCT03007329 | Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Medical University of Vienna | [177,178] |

| Uncontrolled T2DM | Linagliptin plus metformin | DPP-4 inhibitor/ inhibiting hepatic gluconeogenesis | Improved glycemic control | Phase 4 | NCT01512979 | Boehringer Ingelheim | [179,180] |

| T2DM | Oral insulin | Insulin | Phase 2 | NCT06473662 | Roger New | [181] | |

| T2DM/Obesity | PF-07081532 | Oral small-molecule glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist | Phase 2 | NCT05579977 | Pfizer | [182] | |

| T2DM | Saxagliptin | DPP-4 inhibitor | Phase 3 | NCT00295633, NCT00121667, NCT00374907 | AstraZeneca | [183,184,185] | |

| Very Uncontrolled T2DM | Soliqua 100/33 | GLP1 RA | Improved glycemic control as an adjunct to diet and exercise | Phase 4 | NCT05114590 | Sanofi | [186] |

| T2DM | Vildagliptin | DPP-4 inhibitor | Phase 3 | NCT00396227 | Novartis Pharmaceuticals | [187] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).