1. Introduction

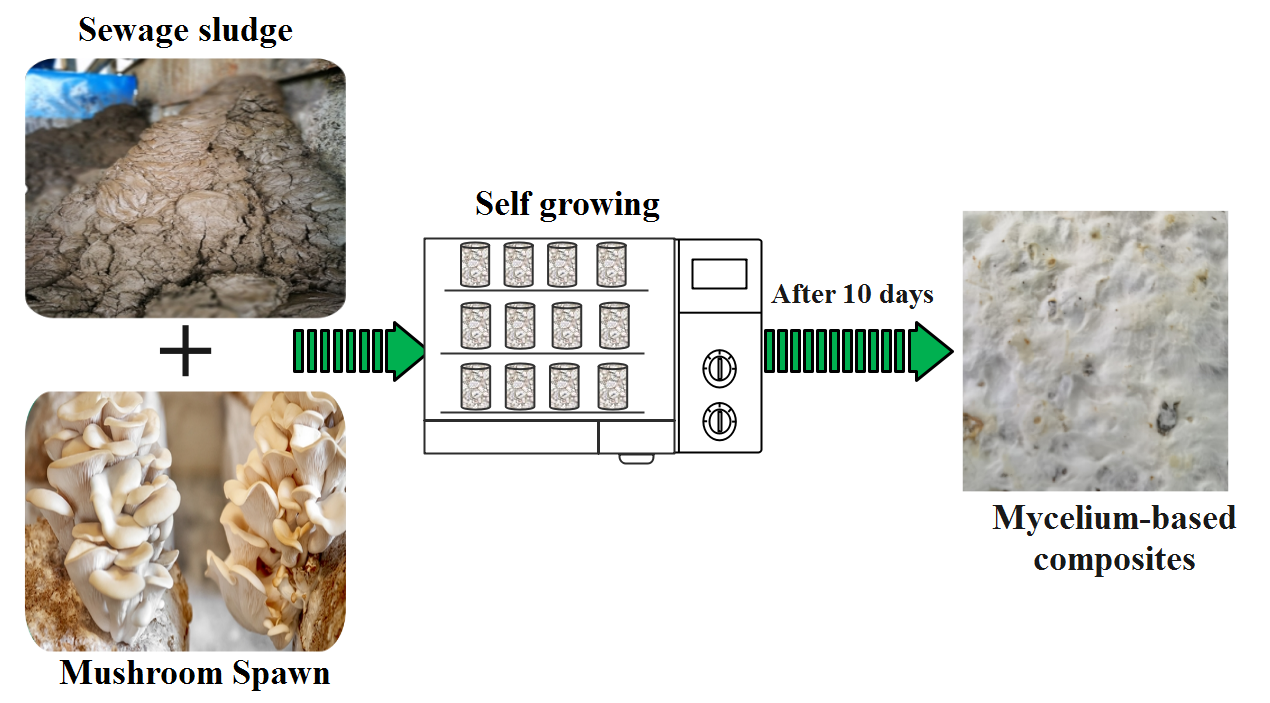

In recent years, mycelium-based composites (MBCs) have drawn the attention of an increasing number of researchers due to their low energy consumption and carbon emission[

1,

2]. MBCs consist of fungi and substrate materials (agricultural by-products), whereby the fungi, primarily enzyme, break down organic matter of substrates by digestion of carbon and nitrogen based substrates resulting in branching of hyphae. These branching filamentous mycelium interface those dispersed substrates through a three-dimensional interconnected networks as natural binder. Unlike conventional manufacturing processes, the mycelial branching process occurs naturally and self-grow to manufacture the resulting MBCs as needed when the colonization conditions are optimized[

3]. They consume less energy, emit less carbon, and are used as biofoam[

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] in packaging[

9], construction[

10,

11,

12], impact-resistant filling materials[

13] and designing[

14]. Agricultural by-products are frequently utilized as substrates to promote the mycelial growth. Divnesh et al. produced MBCs using rice husk, bagasse, coconut husk, and juncao grass. Visual inspection revealed that the composites achieved 70 to 80% mycelial colonization rates. Furthermore, the juncao grass containing 2% lime and 10% wheat bran grew the fastest overall, with over 80% mycelium colonization, generating high compressive strength of 78.34 kpa[

15]. G.A. Holt et al.[

9] added starch and gypsum to cotton plant biomass of different particle sizes to obtain MBCs and the compressive strength was 72 kPa. A comparison of bran/cotton and bran/hemp mixtures showed that bran offered desirable nutrients capable of increasing mycelial growth. Besides, bran improved the mechanical properties of MBCs because bran particles synergistically increased composite strength and hardness by filling effect and strengthening effect of reducing the voids[

16]. To expand the substrates source, Sun et al.[

17] cultured Trametes versicolor mycelium on yellow birch wood particles and the materials formed from mycelia-modified wood had better properties than that from physically mixing pure wood particles and mycelium. Moreover, MBCs got stiffer when the substrate was harder to digest.[

18] The use of a stiffer substrate or a strain with stiffer mycelia would likely yield MBCs with much more favourable physico-mechanical properties.[

19] The nutritional substrate as inocula increased the overall density[

6]. The resulting MBCs are not only low-cost and carbon emissions, lightweight, biodegradable, but also present exccellent physico-mechanical properties. However, because agricultural by-products are seasonal, their output is limited by a constant need for substrates. Considering these characteristics of the MBCs, they have the potential to be used as lightweight backfill materials (LBMs). The LBMs are normally consist of soil, cementing material (usually cement), water, expanded polystyrene (EPS) or foam agent[

20,

21]. In recent decades, they are widely applied in the backfilling of embankment, slope protection, backfilling behind retaining walls and bridge abutments, and backfilling pipeline trenches[

22]. However, the production of LBMs consumes large amounts EPS or cement which poses an environment challenge of high energy consumption and carbon emissions[

23]. A large body of research is devoted to the green LBMs, with an emphasis on their low environmental impact and carbon footprint[

24].

Sewage sludge (SS) is a semisolid byproduct derived from municipal wastewater treatment. It consists of a heterogeneous mixture of proteins, carbohydrates, lipids or fats, and organic and inorganic matter[

25]. Owing to rapid development of urbanization, the amount of SS is increasing and its disposal has become an urgent issue. Some disposal methods for SS, such as landfilling and land use, have been obsoleted due to high energy consumption and secondary pollution[

26,

27]. Incineration and utilization as building materials is regarded as one of the most promising disposal options. The SS ash were used or as supplementary cementing materials under alkali-activated stimulation[

28]. However, the organic matters as a resource, which should be beneficial to the manufacture of MBCs and provide essential nutrients to enable mycelial growth, have been decomposed by large amounts of heat energy among sintering requires.[

29] It’s also reported fungi also readily spread on inorganic glass fines, but about 50 wt% nutritional substrates were supplemented to facilitate sufficient growth, because the high inorganic content limited growth to a weak surface spread[

30]. Thus due to the heterogeneous mixture, SS are promising to be an alternative to agricultural by-products for bacteria-induced cementation and mycelial growth.

Set against this background, a kind of bio-based LBM named mycelium-based composites (MBCs) was proposed in this paper. Hyphae (Pleurotus ostreatus) were cultured in the substrate as three different substrate types namely, bagasse (BM), a mixture of bagasse plus sewage sludge (BSM) and sewage sludge (SM) to investigate the feasibility of developing MBCs with substitution of SS for bagasse. Appearance test were to evaluate the biological compatibility of fungi on SS and mycelial colonization of the MBCs. The physical properties of the MBCs, such as density and volume shrinkage were examined and tested. Compressive strength test was conducted to study the mechanical characteristics of MBCs. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and fourier transform infrared spectroscopy analysis (FTIR) were conducted to study the morphological characteristics. The findings of this study provide an alternative pathway for SS disposal as a nutrient supplement in MBCs production.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In this study, bagasse (

Figure 1(a)) and SS (

Figure 1(b)) were used as substrates. Bagasse were milled to different size ratios by means of a straw cutter followed by screenning to exclude particles more than 10 mm (square-mesh screen of 9.5 mm). SS was collected from Deyang Solid Waste Disposal Co., LTD. The treatment process for the SS was not published. The chemical composition and other physical properties of the SS were shown in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3. The ready-made mycelium,

Pleurotus ostreatus used in this study consisted of 5% hyphal inoculum grown on the 95% wt. nutrient rich wheat grains were purchased from the commercial farm (

Figure 1(c)).

2.2. Preparation of MBCs

2.2.1. Preparation of Substrates

The bagasse was hand-mixed with deionized water (the volume ratio of fibres to water was 1:2) to remove impurities. The bagasse was autoclaved at 121°C for 3 hours (JSM280G-12, Ningbo, China) to sterilize and left to cool to room temperature. Then, the samples were packed into a polypropylene bag, sealed and put into an ozone disinfection cabinet (ZTD50A-50, Foshan, China) to avoid bacterial contamination. The same sterilization process was performed to SS. To investigate the compatibility of fungi with SS, three different substrate types by bagasse (BM) as control were designed to prepare MBCs with the ready-made mycelium inoculation. Bagasse and sludge were used alone and in combination at different mixture ratios, as shown in

Table 4.

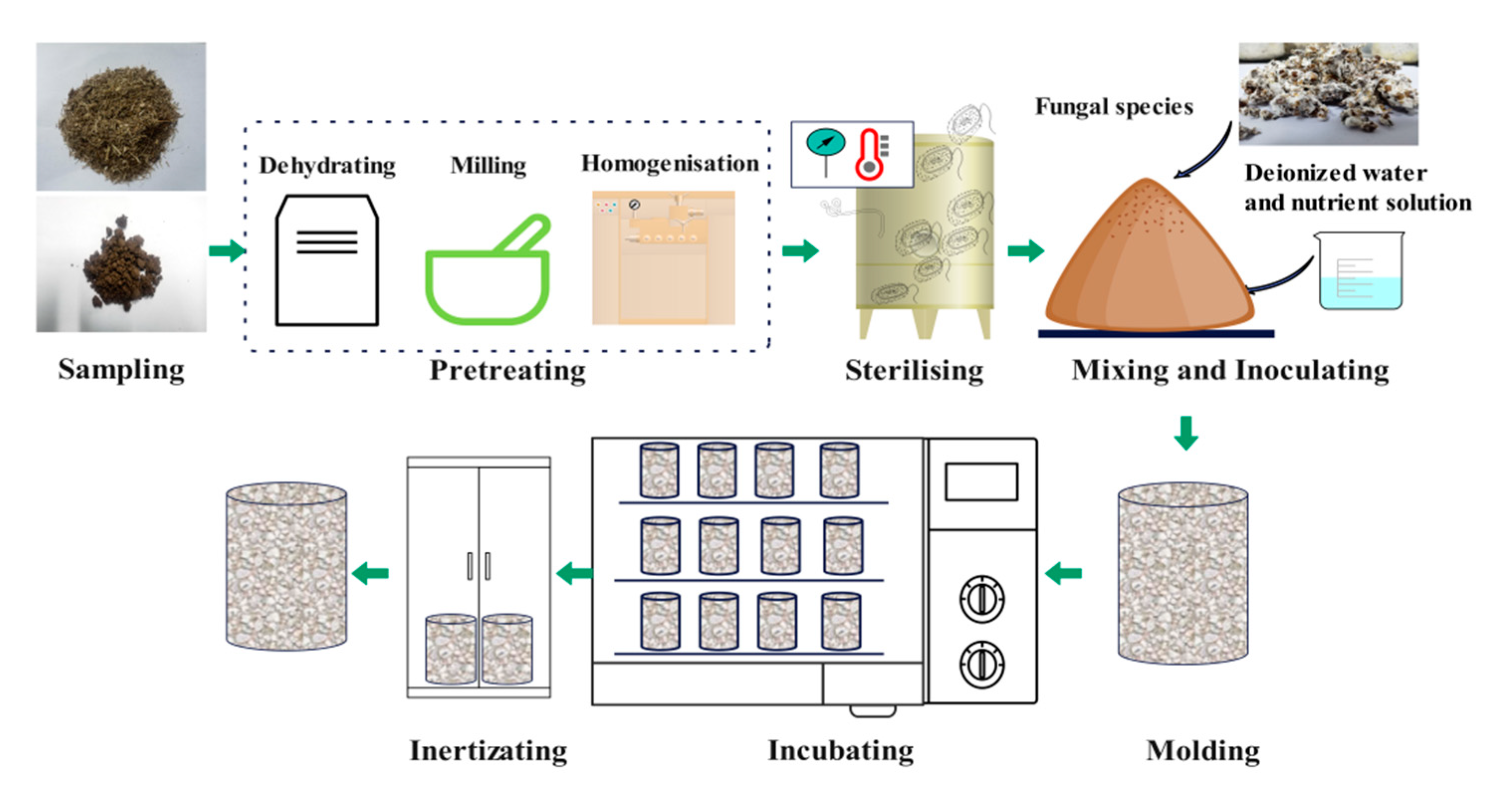

2.2.2. Preparation of MBCs

The flowchart for preparing the MBCs is shown in

Figure 2. Ready-made mycelium were removed from the polypropylene bottle and torn down to smaller particles. According to the protocols of proportion shown

Table 4, the mixture obtained from the ozone disinfection cabinet (ZTD50A-50, Foshan, China) was inoculated with the ready-made mycelium on a clean bench and was moulded into a round-mouth cup with a diameter of 5 cm and a height of 8 cm without compaction. To avoid the moisture evaporation, the top surface of the moulds were sealed with plastic wrap. Moreover, holes were poked in the plastic wrap to ensure good ventilation. A total of 30 samples were prepared. They were then placed in a curing box (SHBY-60b, Cangzhou, China) with humidity ranging from 60%-70% and a temperature of 25±1°C. Every 24 hours, a mist spray was used to water the samples, and the growth state was recorded. A few days later, the MBCs were demoulded and stored in a dark incubator to test the wet density. The mixture was then oven-dried for 12 hours at 80°C for inertization, which was performed to deactivate the fungal organisms and obtain MBCs samples.

2.3. Testing and Characterization

2.3.1. Appearance, Density and Volume Shrinkage

The appearance of MBCs at different ages were characterized by recording photos[

31]. A greater amount of hyphae indicated that the hyphae grew more rapidly at the same time and more nutrients were obtained from the substrates. This contrast of appearance was used to determine the biological compatibility of fungal species with SS.

The dry density, wet density and volume shrinkage of the samples of MBCs were calculated by according to the measuring the mass and volume in Equation (1) (2):

Where m was the weight of the MBCs. When MBCs were demoulded, stored in a dark incubator at a temperature of 25 ℃ and 60% RH until they reached constant mass for wet density measurements. Via oven-drying to make fungal cell inertial, measures the constant mass. Dry density was calculated. V was calculated by the diameter and height. For LBMs, the lower density and volume shrinkage indicated the better the properties of the MBCs. Three times of repeated test for each sample were conducted.

2.3.2. Compressive Strength Test

The compression test was conducted via a microcomputer-controlled electronic universal testing machine (EHC-1300, Shanghai, China), with a compression rate of 0.5 kN/s. To reduce errors, three samples were tested and the average value was taken as the final compressive strength of the MBCs.

2.3.3. Thermal Conductivity Test

The thermal conductivity of the MBCs was determined using a thermal conductivity instrument (TPS2500S, Hot Disk, Sweden) based on the ISO 22007-2 test standard. Prior to testing, make sure the samples were completely and absolutely dry.

2.3.4. FTIR Test

The FTIR spectra of the MBCs were recorded via a Spectrum One FTIR Spectrometer (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) in the range of 400-4000 cm-1.

2.3.5. SEM Test

The morphology of all specimens was detected by the field emission scanning electron microscope (Zeiss Ultra 55, Oberkochen, Germany). The separated cross-section of samples were cored into small pieces and used to observe internal surface structures. The samples were dried for 24 hours at 80 ℃ to expedite fungal inertization and then coated with a thin layer of gold to SEM analysis. The surface morphology of the gold-coated samples was observed via SEM.

2.3.6. TG Test

Thermogravimetric analysis was used to examine the thermal stability and weight loss of the samples on a thermoanalyzer (ZRT-B, Beijing, China). The samples were heated under an air atmosphere from ambient temperature to 800 ℃ at a heating rate of 5℃ per min.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All of the MBCs analyses were performed in triplicate. The experimental data are presented as the means±standard deviation and were analysed via Origin software.

3. Results and Discussion

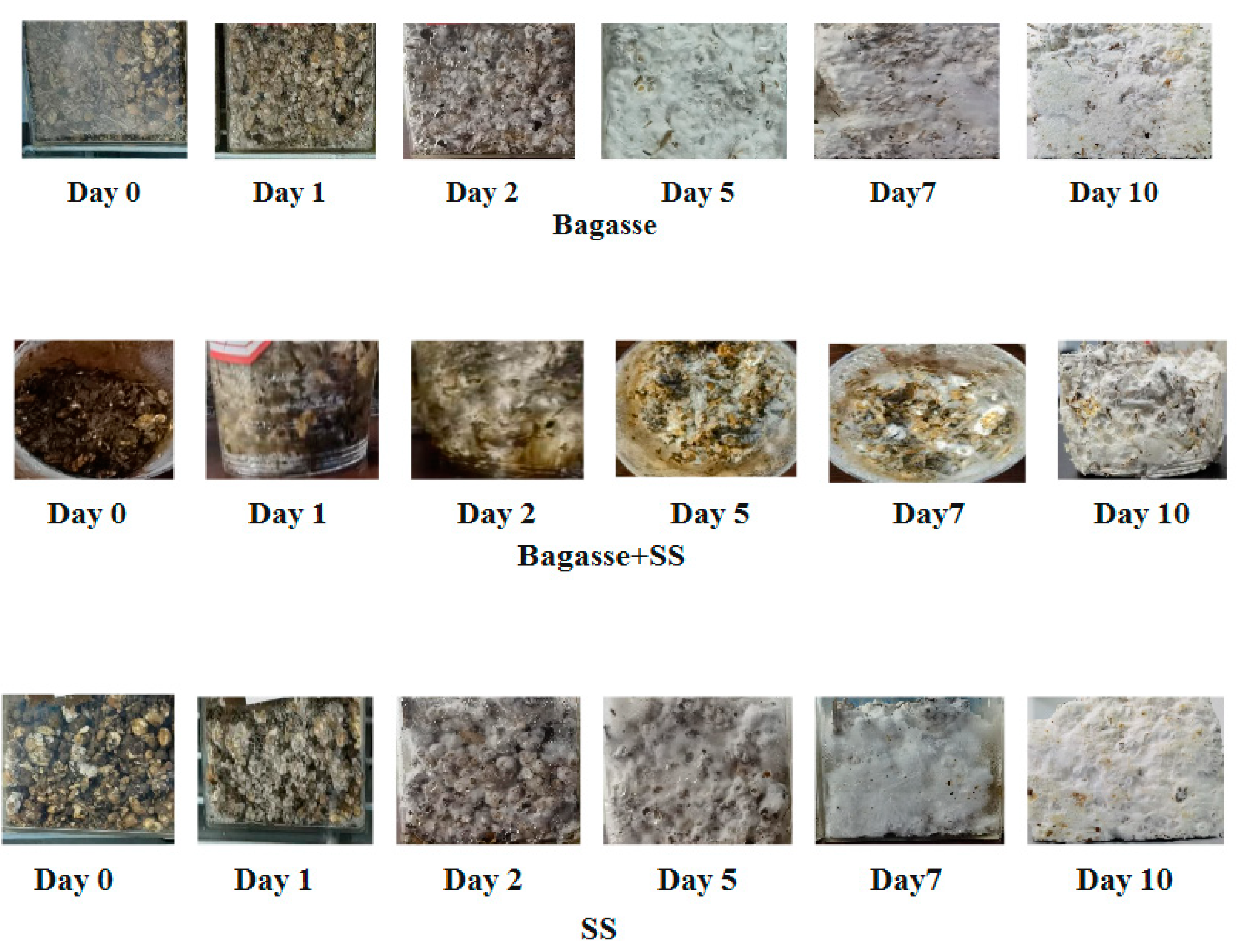

3.1. Appearance

Figure 3 shows the formation process of the MBCs. On day 1, fungal growth was not visible to the naked eye because the fungal population was in a period of zero or low growth, referred to as the lag phase.[

32] Over the next 24 hours, prolonged rapid growth called exponential growth phase occurred. The inoculated fungal cells grew accustomed to the new chemical and physical environment. In comparison, the sample cultured by bagasse showed that the hyphae grow more rapidly. Because enzyme of fungi degraded substrates to obtain nutrients for vegetative growth by secreting cellulase, hemicellulose and lignin. The enzyme of

Pleurotus ostreatus showed the natural affinity of hemicellulose[

33]. As shown in

Table 1, bagasse contained more hemicellulose than sewage sludge, and fungi firstly consumed simple sugars (i.e. hemicellulose) rather than more complex sugars (i.e. cellulose). On day 10, all the samples were white on their external surfaces. ready-made mycelia successfully colonized the substrates during the growth stage, resulting in signature white mycelial layers on the outer surface of the composites. The hyphae can enter the interspaces of substrates with the help of expansion pressure of the growing hyphae; they then branch and extend into the interspaces and surfaces of filling materials to allow for cohesion in incoherent substrates[

34,

35] and confer three-dimensional interconnected networks to resulting MBCs.

Figure 4.

growing process of MBCs derived from different substrates. A: bagasse, B: bagasse+SS, C: SS.

Figure 4.

growing process of MBCs derived from different substrates. A: bagasse, B: bagasse+SS, C: SS.

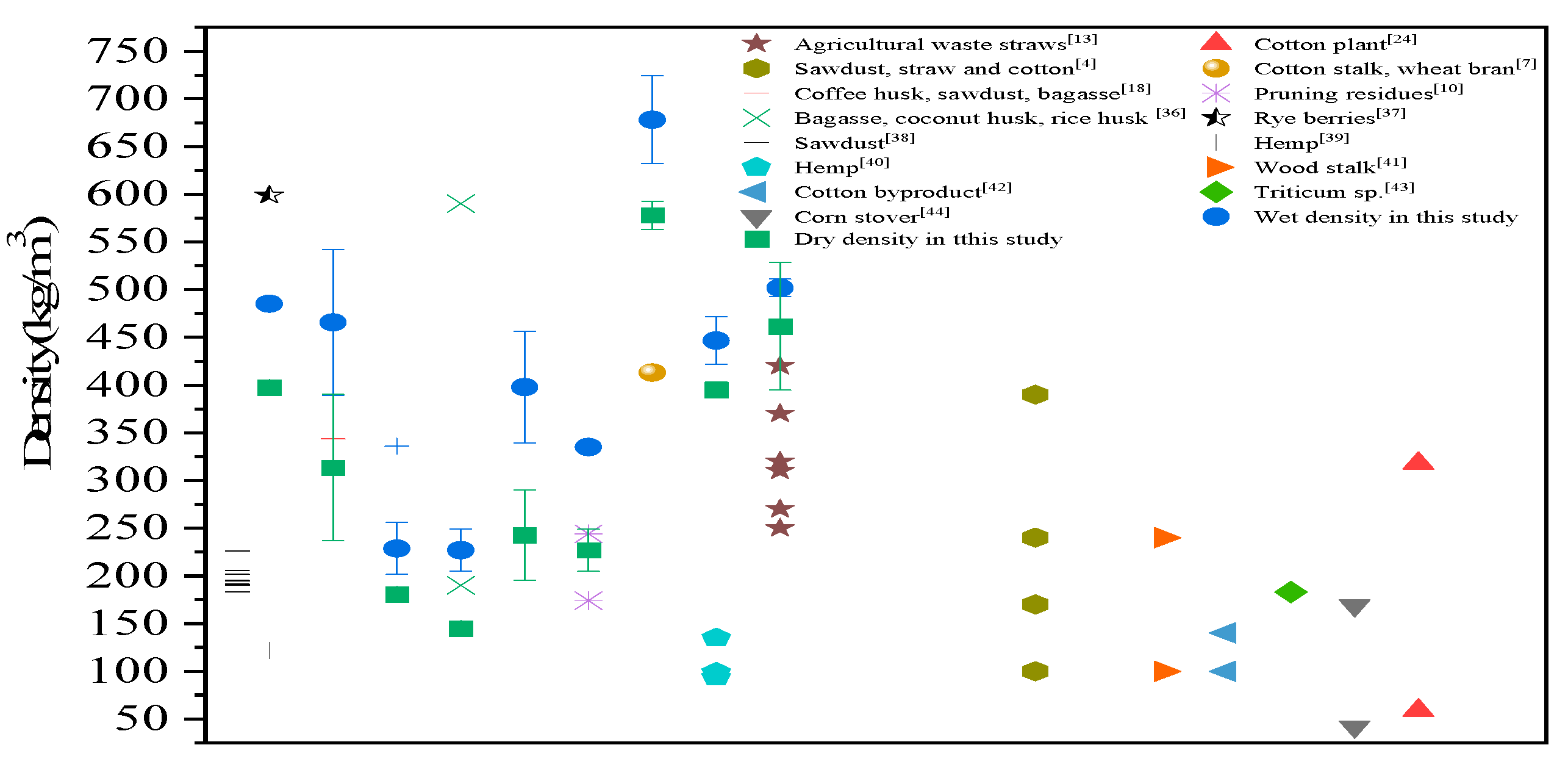

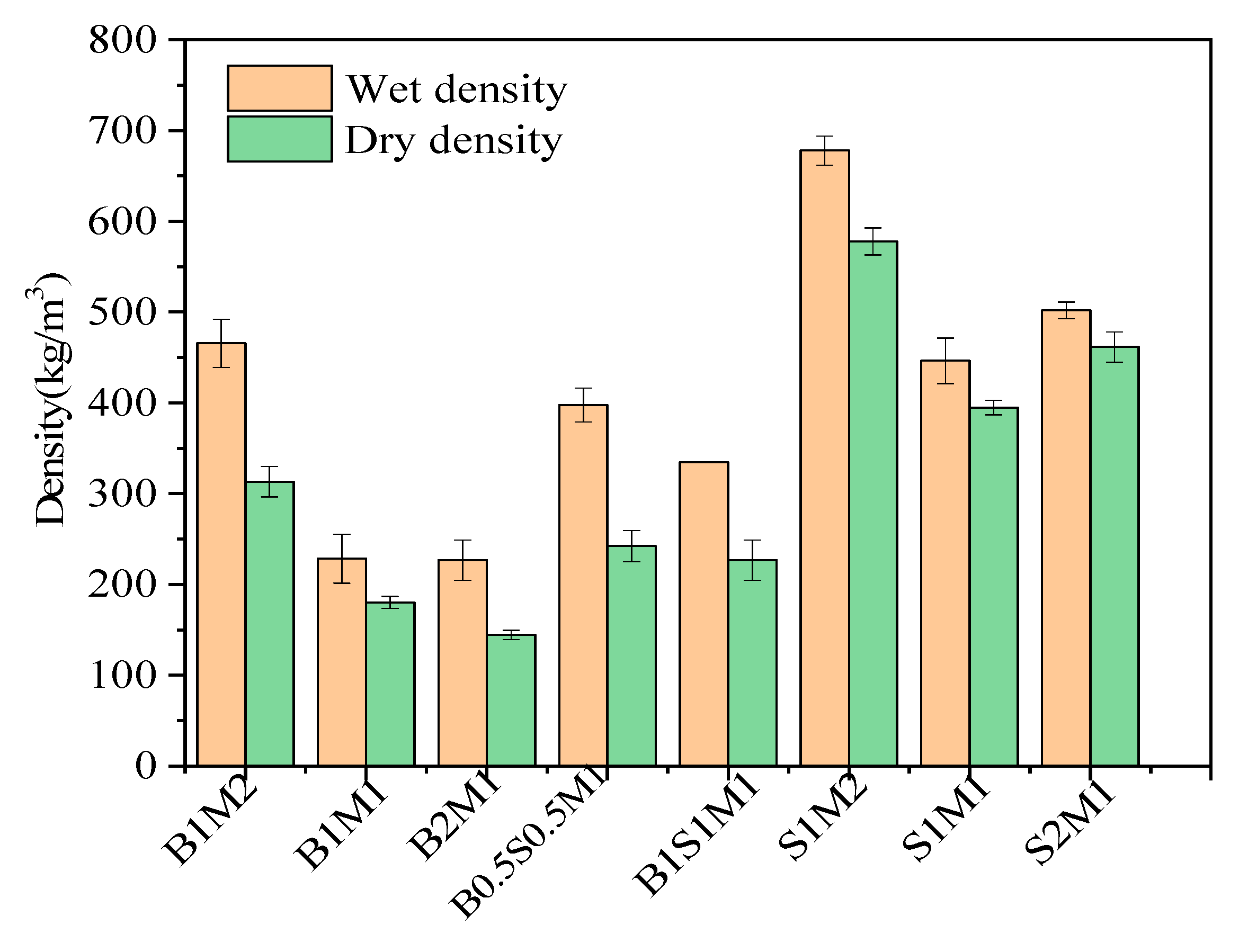

3.2. Density

The data reported in the literature are compared in

Figure 5, and the density derived from different agricultural wastes or plant residues ranged from 100 to 700 kg/m

3. Our data demonstrated that the density of MBCs based on SS was acceptable in the lightweight backfilling engineering and comparable to those prepared from agricultural waste. The wet density and dry density of all samples are shown in

Figure 6. Overall, the MBCs in Group 1 derived from bagasse as sole substrate had relatively low densities. When the proportion of bagasse was increased from with from 1:2 to 2:1, the wet density and dry density of the MBCs decreased. There was a positive correlation between density and ready-made mycelium content, although a negative correlation existed between density and bagasse percentage. When SS was added at different ratios in Group 2, the wet and dry densities of the MBCs increased. It was mainly attributed to the different densities of the substrates, as shown in

Table 2. The heavy constituents in the substrate mixture subsequently increased, resulting in an increasing density of MBCs. The density of the MBCs increased with the use of sludge as the sole constituent. However, the histogram of Group 3 shows that the density curve with respect to the percentage of SS had an inflection point. Specifically, SS provided nutrients for vigorous mycelial growth, and the hyphae decomposed the substrates to reduce the density of the MBCs. When the ratio of SS to bagasse reached 1:1, the wet density and dry density were the lowest at 446 kg/m

3 and 395 kg/m

3, respectively.

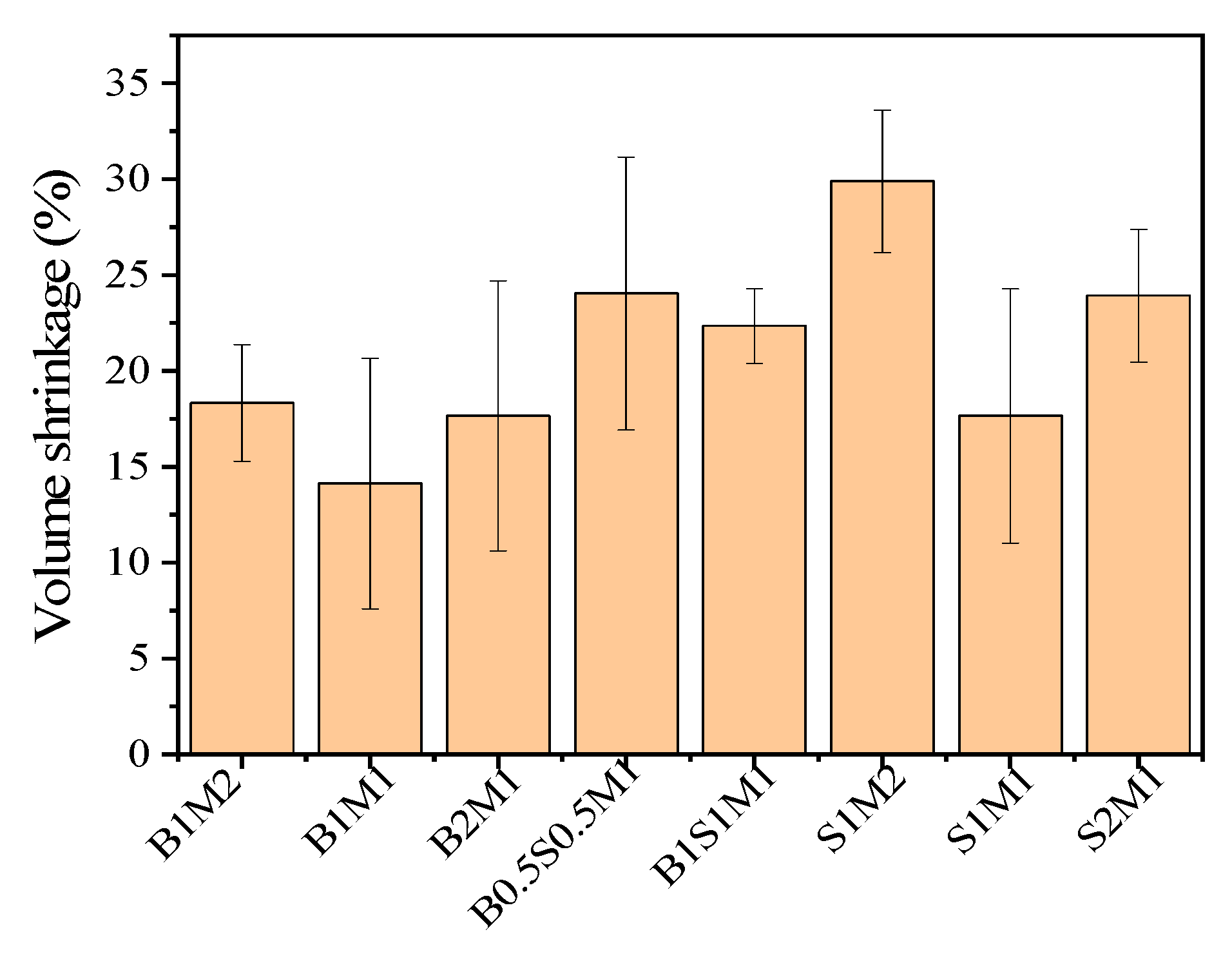

3.3. Volume Shrinkage

The volume shrinkage of MBCs is shown in

Figure 7. The volume shrinkage first decreased and then increased in every group. In comparison, the volume shrinkage of S1M2 (29.90%) samples were the greatest than that of the other samples. The decreases in volume of the B1S1M1 and S2M1 samples were 22.34% and 23.92%, respectively. The differences in volume shrinkage among B1M2, B1M1, B2M1 and S1M1 were very small. This is attributed to residual water vaporization in the sterilized substrates and the high moisture content in the MBCs. After the samples were placed in an oven, most of the moisture was eliminated; as a result, the mass and volume of the MBCs decreased. Furthermore, the standard deviation in the volume shrinkage for all the MBCs was greater than the standard deviation for density. The available data on volume shrinkage were inconsistent, and the level of volume shrinkage was too high for dimensional stability in the product. The implication is that the prepared MBCs may be suitable only for applications where dimensional variability is permissible. Moreover, it is necessary to enhance the anti-shrinkage potential of MBCs in subsequent investigations.

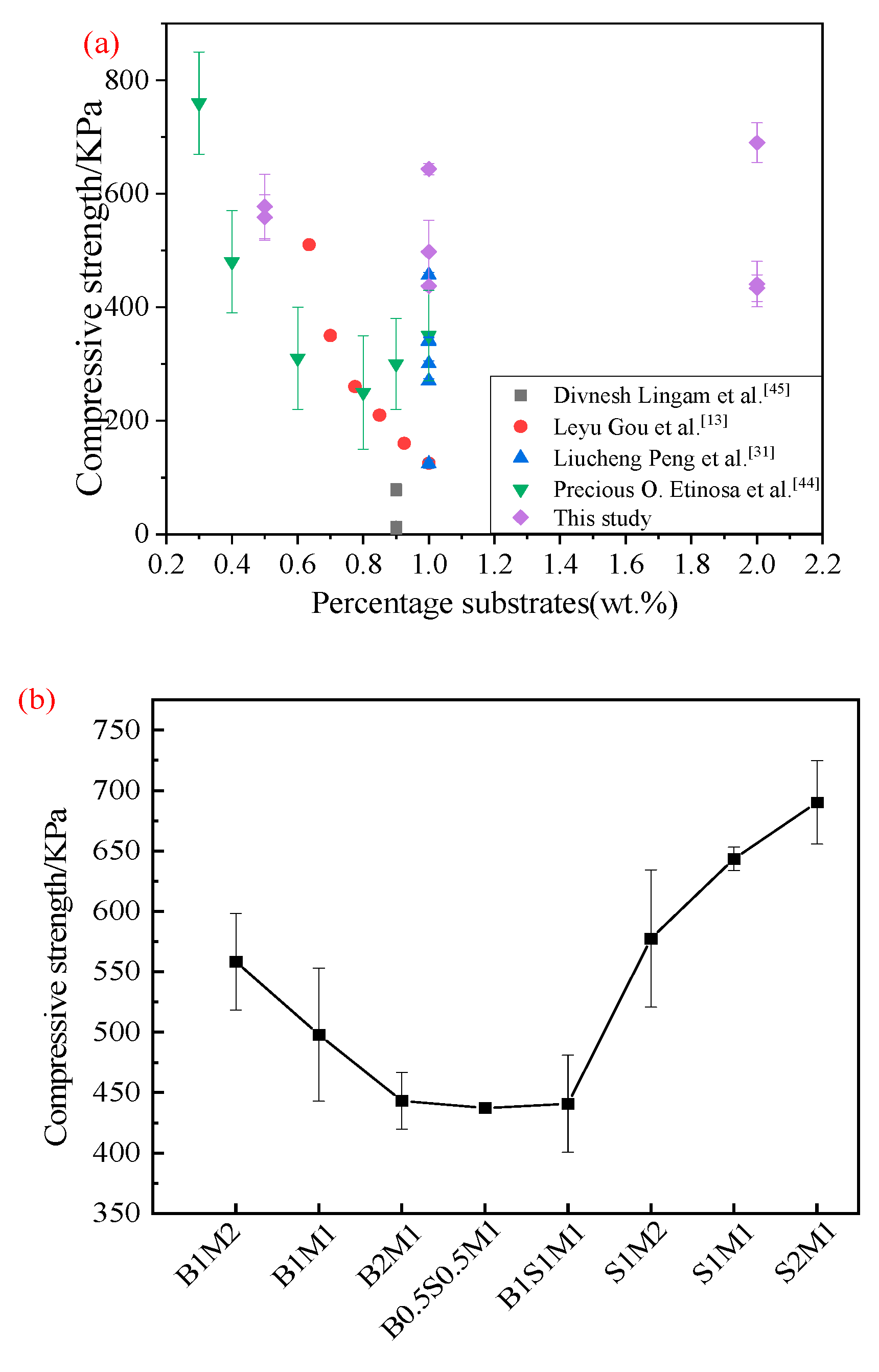

3.4. Compressive Strength

Figure 8(a) presents the compressive strengths of the samples reported in the published literature. The strength distributions of MBCs with different substrates were wide and ranged from 7.7 to 760 KPa. Substrates derived from agricultural wastes vary in terms of structure and nutrient levels, which has an impact on the mechanical qualities of the MBCs and on the growth of fungi[

39]. Substrates with high nutrient content result in rapid fungal growth and high compressive strength, but substrates with low nutrient contents can also sustain fungal growth. The compressive strength in this study is shown in

Figure 8(b). It can be seen the compressive strength gradually decreased with increasing bagasse/ready-made mycelium ratio, indicating that the strength in the material was dominated by the growth of ready-made mycelium. On the basis of density (

Figure 6), it was determined that the density clearly decreased, and strength decreased[

10]. The compressive strength of the MBCs gradually stabilized with increasing percentage of SS in the mixed substrate. However, the compressive strength in Group 3 showed the opposite trend when the substrate consisted of only SS. This finding further verified that SS provides nutrients for mycelial growth on particulate-based lignocellulosic SS and that fungal cells assemble into filaments, forming a highly interlocked porous network structure that binds the particulates of SS together[

18]. In addition, the organic components in SS act as nutrient sources, and inorganic matter plays a role in the filling effect. The compressive strength of S1M2 was lower than that of S2M1 (

Figure 8 (b)). The filling and strengthening effects of SS were most apparent with increasing percentage of SS[

44], which improved the mechanical properties of the final MBCs.

3.5. Thermal Conductivity

Table 5 showed the thermal conductivity of B1M2 and S2M1 was 0.12 Wm

-1K

-1 and 0.13 Wm

-1K

-1. Under the same circumstances, MBCs made from SS had higher thermal conductivity than those constructed from bagasse due to SS greater amount of inorganic matter. By combining the dry density in Part 3.2, the thermal conductivity of B1M2 satisfied the standard range of T/CHTS 10165-2024 (Technical Guidelines for Application of Foamed Lightweight Soil in Highway, in which the limit λ of class W4 is ≤0.12 Wm

-1K

-1). The thermal conductivity of S2M1 was less than the class W5 standard of (the limit λ of class W5 is ≤0.15Wm

-1K

-1). The literature reported as fungal degradation progressed, the thermal conductivity of the MBCs decreased gradually.[

46] Therefore, the longer incubation time of the bagasse-based MBCs could be investigated in future studies.

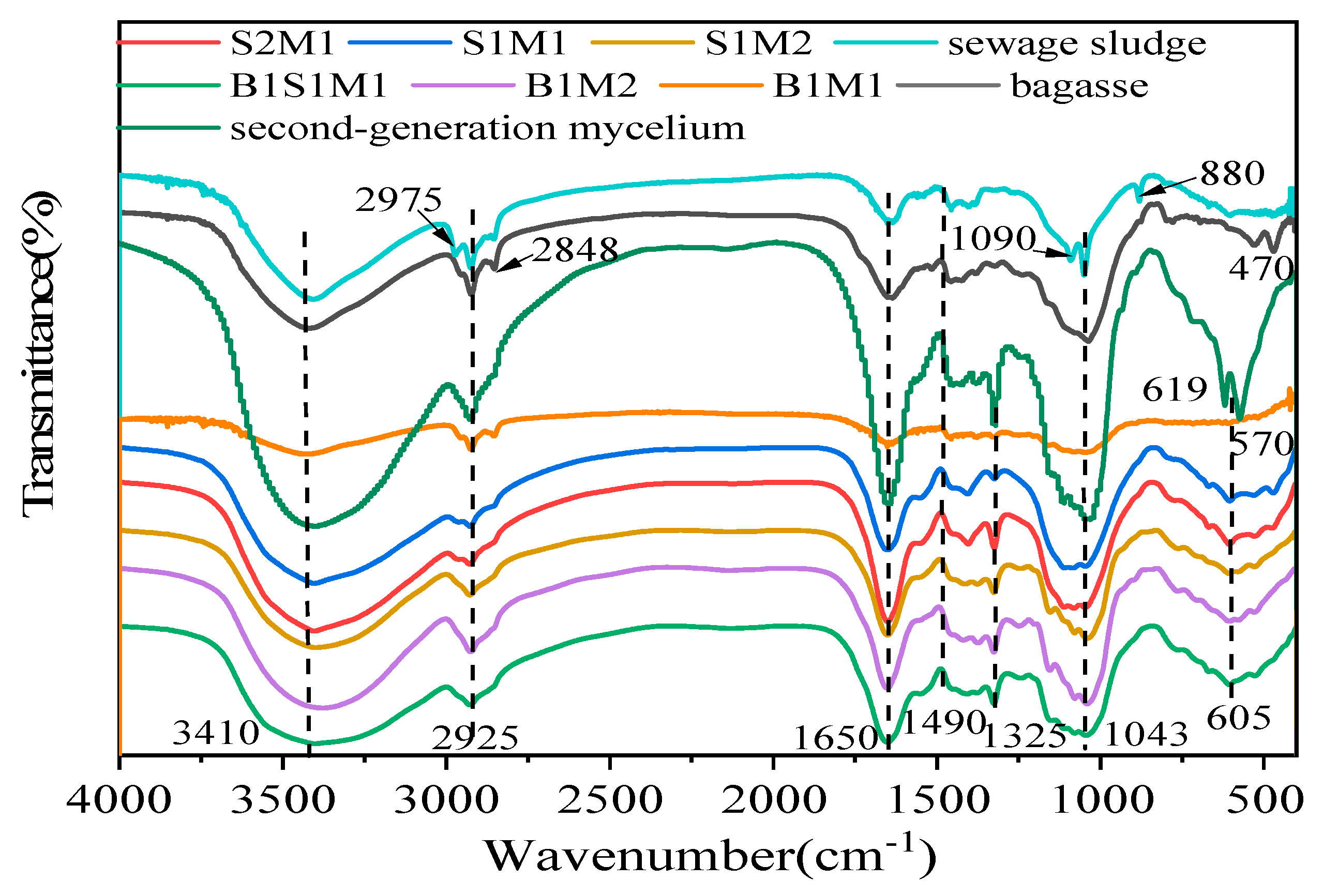

3.6. The FT-IR Analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was used to investigate the differences in the chemical compositions of the raw materials and the resulting MBCs.

Figure 9 and

Table 6 present the FT-IR spectra and corresponding peak assignments. The characteristics for the biomolecules in

Table 1 as well as the elements listed in

Table 2, such as lipids, proteins and polysaccharides, are reflected in the FT-IR spectra. As shown in

Figure 9 and

Table 6, bagasse presented signals typical of various functional groups, such as O‒H stretching of polysaccharides (from cellulose and hemicellulose) at 3410 cm

-1[

47] and CH symmetric and symmetric stretching at 2975 cm

-1, 2925 cm

-1 and 2848 cm

-1 (waxes and oils)[

48]. The signals for C=O stretching (called amide I)[

49,

50] and -NH

2 at 1650 cm

-1 and CH

2 bending at 1490 cm

-1 are related to proteins. The peak at 1325 cm

-1 is attributed to the NH

2 stretching vibration in amines (amide III)[

17]. The C-C stretching vibration at 1043 cm

-1 is attributed to proteins, lignin and polysaccharides. Compared with those in bagasse, the signals of proteins and polysaccharides detected in SS and ready-made mycelium were higher. For example, SS showed a characteristic peak for the stretching vibration of C-O groups from polysaccharides at 1090 cm

-1 and the glucan β-anomer C-H bending stretching vibration of cellulose at 880 cm

-1[

17,

47,

51]. Additionally, ready-made mycelia presented stronger characteristic peaks at 1650 cm

-1, 1325 cm

-1, 1050 cm

-1 and 605 cm

-1. The MBCs presented characteristic bands common to the starting materials (bagasse and SS) combined with absorption bands from the ready-made mycelia. These findings are similar to those reported in the literature, with the bands identified in the fungal species studied aligning with the main bands reported previously. Remarkably, the peaks for amide I at 1650 cm

-1, amide III at 1325 cm

-1 and C-H below 800 cm

-1 weakened in the MBCs relative to the raw materials. The chemical characteristics of the starting materials were also clearly responsible for distinct changes in the infrared spectra of the MBCs[

12,

17,

31,

47,

52]. Band related to protein, cellulose and polysaccharides (1090 cm

-1, 880 cm

-1, 619 cm

-1) were not detected in any MBCs, evidencing decomposition of proteins, cellulose, and hemicellulose. The enzymes of fungi secreted during

Pleurotus ostreatus growth facilitated the rapid decomposition of SS and bagasse through the digestion of proteins, cellulose, and hemicellulose.

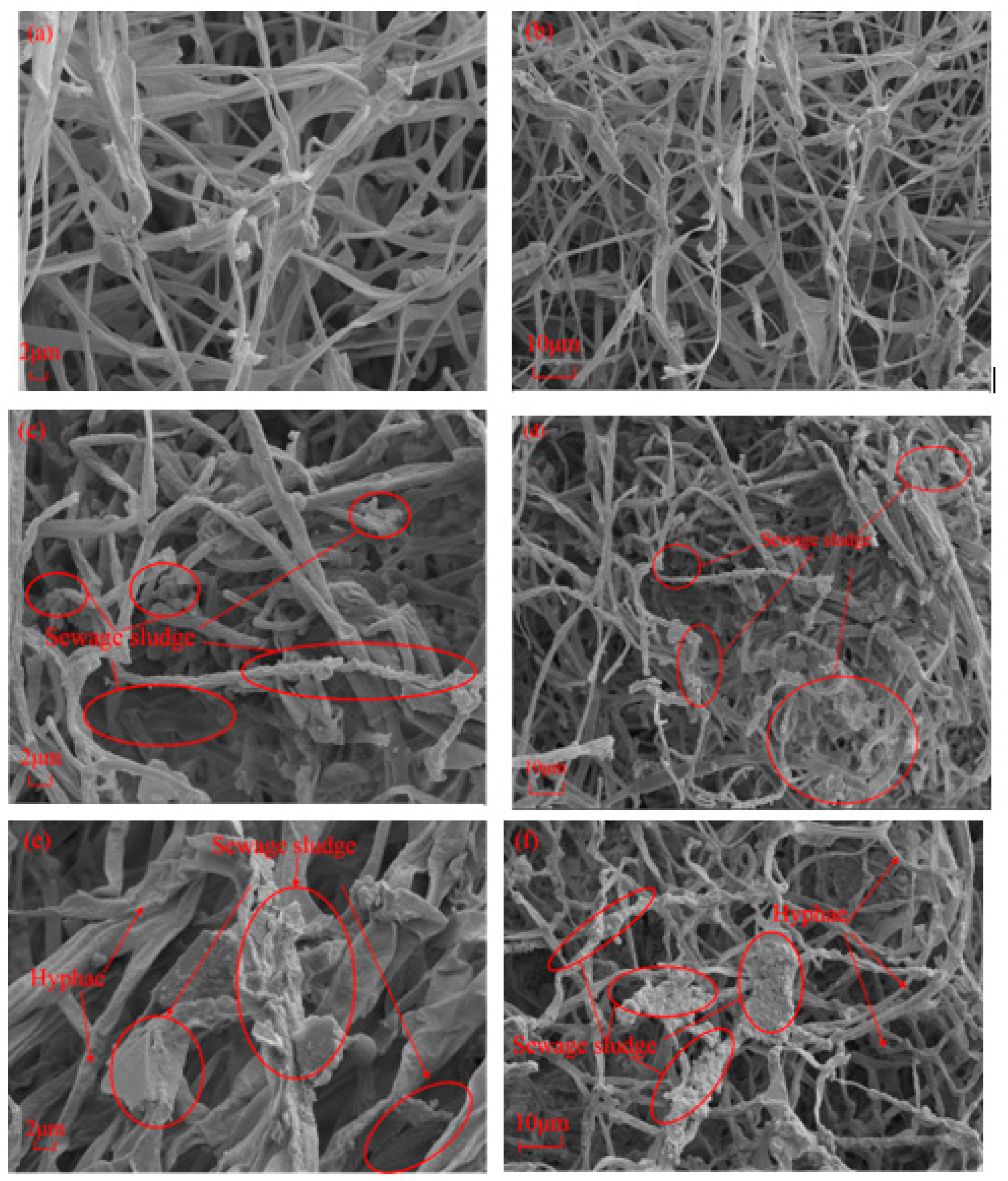

3.7. SEM Analysis

Figure 10 presents the images of the representative MBCs. Two SEM images per sample were captured at 1000x and 2000x magnification. These SEM images confirmed that the interwoven network of MBCs was generated by filamentous hyphae and aggregated fibrous mycelia on the bagasse and SS. The resulting bagasse MBCs were relatively thin, and the interwoven hyphal networks had more air voids between the bagasse fibre(

Figure 10(a)(b)). The addition of SS led to tenacious and dense hyphal growth, as shown in

Figure 10(c)(d). The SEM images (

Figure 10(e)(f)) for S1M1 showed highly clustered SS and hyphae that were relatively strong and thick. Because the presence of proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids in SS facilitated hyphal growth and nutrient utilization[

52], the exterior surfaces of hyphae overlapped with those of SS layers, and the voids were filled with SS, which resulted in a denser network of mycelial filaments, as shown in

Figure 10(e)(f), to further verify the filling and strengthening effects of SS.

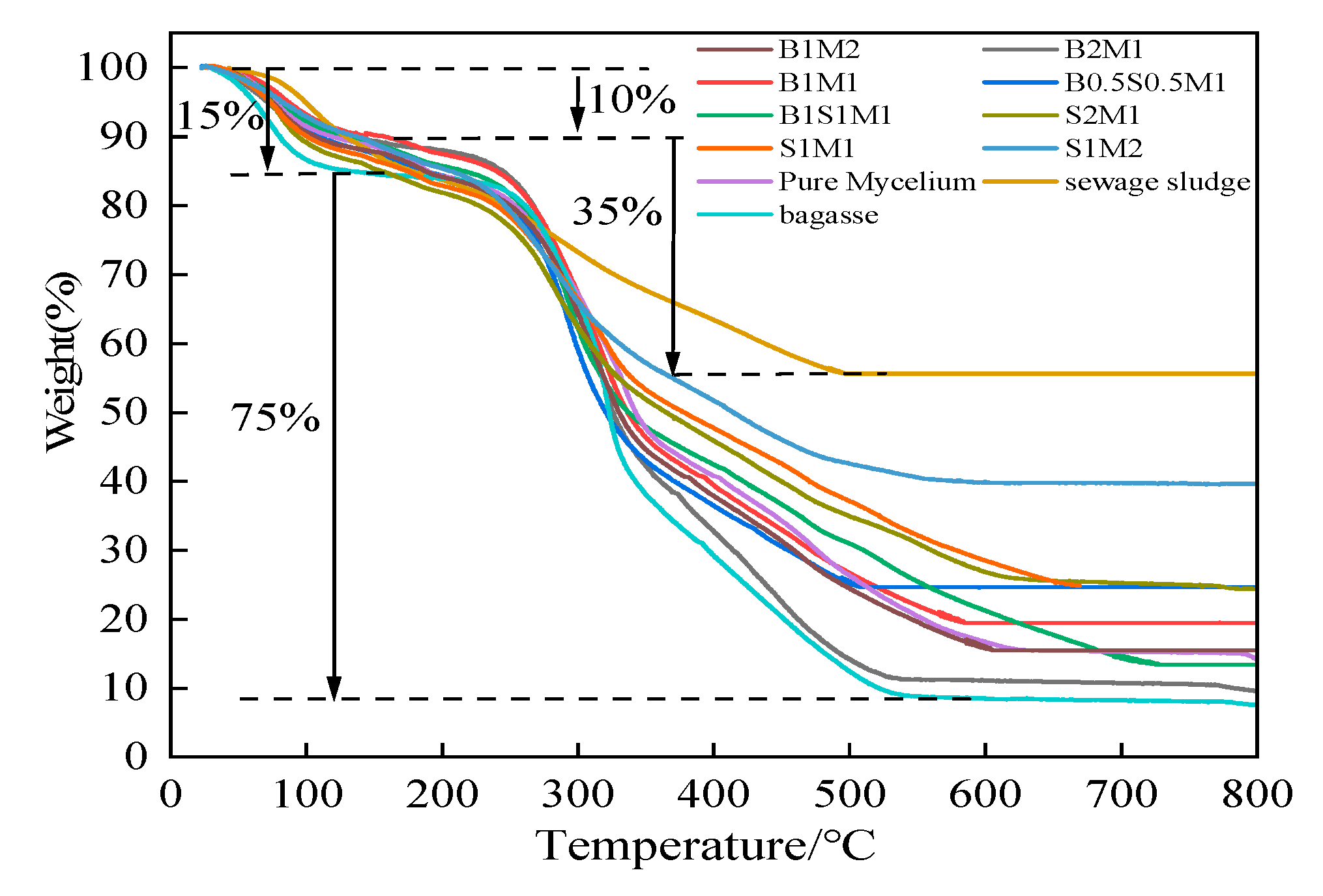

3.8. TGA Analysis

The thermal stability of the MBCs was analyzed using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), as shown in

Figure 11. Two decomposition stages are observed in all treatment. At 80°C-100°C, 10%-15% of the weight loss was attributed to the evaporation front for free water and chemically coupled water. During the second stage, distinct degradation occurred between 250 °C and 500 °C. Approximately 50% and 10% of the weight was lost, as shown in the top and bottom of the photographs, respectively. Owing to the presence of inorganic matter in the SS, which may greatly increase thermal stability, the final residue of SS at 500 °C was quite high, measuring 55.67%, whereas the residue of bagasse was only 12.44%. However, thermal degradation of MBCs began at 250 °C and constituted more than half of the mass loss at 350 °C. The loss of mass remained constant at 500 °C. These were within the degradation ranges of bagasse and SS. The cellulose and hemicellulose in the fibrous mycelium broke down at 200-300 °C, whereas lignin decomposed at a temperature of approximately 400 °C[

53]. Therefore, it was deduced that the thermal degradation of the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin in the MBCs was the cause of the rapid decrease in the second decomposition stage of all MBCs. On the basis of the thermal stability observed via TGA, it was determined that the samples in Group 3 were more stable. Hence, the addition of SS to MBCs resulted in improved thermal stability and resistance to thermal degradation.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the potential for producing MBCs using SS was explored. The MBCs were prepared by the edible fungus Pleurotus ostreatus cultured on SS and bagasse as substrates. The physico-mechanical properties, morphological properties, and thermal stability analysis of the MBCs were studied. On the basis of a series of experimental tests, the following conclusions were drawn:

1)The results prove that the ready-made mycelium have grown on the SS substrate bound together to form a mycelial network on day 10. The fungi had good biological compatibility with SS.

2)The MBCs derived from bagasse as the sole substrate presented the lowest densities. When SS was added at different ratios to bagasse and as the sole constituents, the density of the resulting MBCs increased. An inflection point occurred with increasing amounts of SS. When the SS to ready-made mycelium ratio reached 1:1, the wet density and dry density of MBCs reached their optimal value of 446 kg/m3 and 395 kg/m3, respectively. However, the lowest volume shrinkage of the MBCs was 14.12%.

3)Owing to the filling effect and strengthening effect of SS, the compressive strength of the MBCs increased significantly with increasing SS proportion. The organic component of SS functions as a nutritional source whereas the inorganic matter as stiffing inclusions plays a role in the filling effect. The compressive strength of the MBCs prepared with a SS/ready-made mycelium ratio of 2:1 reached 690.20 KPa.

4)The thermal conductivity of the MBCs was comparable to foamed lightweight soil used in highway. But the mycelium as natural binder bring significantly better environmental benefits than the EPS and cement which have inflicted great damage to environment of high energy consumption and carbon emissions during production process.

5)An analysis of the microstructure of the MBCs revealed that the hyphae on SS were stronger and thicker compared with those on bagasse, because the more additional nutrients from SS for fungal growth. Adding SS improved the thermal stability and thermal degradation resistance of the MBCs.

This is the first study reporting the use of SS to manufacture MBCs and highlights the potential use of SS to produce a range of MBCs. Therefore, the mechanism on SS promoting mycelial growth is required to elucidate, and accurate biological tests are needed to further characterize the digestion process of mycelia for carbon and nitrogen sources present in SS. Further studies are recommended to optimize the manufacturing procedures to improve their performance and address the technical barriers for their application.

Author Contributions

Min Hu: Writing original draft preparation, experimental analysis, writing, funding, review, editing and supervision; Xuejuan Cao: Resources or funding acquisition, validation and visualization, project administration, statistical analysis and data validation.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.52278441); Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (Surface Project) (No.2024NSFSC0133); Chongqing Graduate Joint Training Base Construction Project (JDLHPYJD2018006); State Engineering Research Center for Resource Utilization of Municipal Sludge(Sichuan College of Architectural Technology (No.SESBM202401, No. SESBM202402).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MBCs |

mycelium-based composites |

| SS |

sewage sludge |

| LBMs |

lightweight backfill materials |

| EPS |

expanded polystyrene |

References

- Sunil Kumar Ramamoorthy, Mikael Skrifvars & Anders Persson (2015) A Review of Natural Fibers Used in Biocomposites: Plant, Animal and Regenerated Cellulose Fibers, Polymer Reviews, 55:1, 107-162. [CrossRef]

- Lai Jiang, Daniel Walczyk, Gavin McIntyre, Wai Kin Chan, Cost modeling and optimization of a manufacturing system for mycelium-based biocomposite parts, Journal of Manufacturing Systems, Volume 41, 2016, Pages 8-20, . [CrossRef]

- Soh E, Saeidi N, Javadian A, Hebel DE, Le Ferrand H (2021) Effect of common foods as supplements for the mycelium growth of Ganoderma lucidum and Pleurotus ostreatus on solid substrates. PLoS ONE 16(11): e0260170. [CrossRef]

- Appels, F.V. Camere, S. Montalti, M. Karana, E. Jansen, K.M. Dijksterhuis, J. Krijgsheld, P. Wösten, H.A. Fabrication factors influencing mechanical, moisture-and water-related properties of mycelium-based composites. Materials and Design.2019, 161, 64-71. [CrossRef]

- Appels, F.V.W., Dijksterhuis, J., Lukasiewicz, C.E. et al. Hydrophobin gene deletion and environmental growth conditions impact mechanical properties of mycelium by affecting the density of the material. Sci. Rep.8, 4703(2018). [CrossRef]

- Yang Zhaohui; Zhang Feng; Still Benjamin; White Maria; Amstislavski, Philippe. Physical and mechanical properties of fungal mycelium-based biofoam. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Bruscato Clá, Malvessi E, Brandalise RN, Camassola M, High performance of macro fungi in the production of mycelium-based biofoams using sawdust-Sustainable technology for waste reduction, Journal of Cleaner Production (2019), . [CrossRef]

- Kayecyleen Canda, et.al. Mycelium-Based Composite: An Experimental Study on the Utilization of Sawdust and Glass Fines as Substrates for Potential Fungi-Based Bio-Formed Insulation Board. International journal of progressive research in science and engineering, vol.4,No. 06,June 2023.

- Holt, G.A., McIntyre, G., Flagg, D., Bayer, E., Wanjura, J.D., Pelletier, M.G..Fungal mycelium and cotton plant materials in the manufacture of biodegradable molded packaging material: evaluation study of select blends of cotton byproducts. J. Bio. Based Mater. Energy, 2012,69 (4), 431-439.

- M. Jones, A. Mautner, S. Luenco, et al., Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: A critical review, Materials & Design(2019), . [CrossRef]

- Scott Womer, Tien Huynh, Sabu John, Hybridizations and reinforcements in mycelium composites: A review, Bioresource Technology Reports, Volume 22, 2023, 101456, . [CrossRef]

- Digafe Alemu, Mesfin Tafesse, Yohannes Gudetta Deressa. Production of Mycoblock from the Mycelium of the Fungus Pleurotus ostreatus for Use as Sustainable Construction Materials[J]. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering Volume 2022, Article ID 2876643, 12 pages. [CrossRef]

- Jingming Cai, Jinsheng Han, Feng Ge, Yuanzheng Lin, Jinlong Pan, Ang Ren, Development of impact-resistant mycelium-based composites (MBCs) with agricultural waste straws, Construction and Building Materials, Volume 389, 2023, 131730, . [CrossRef]

- Attias N, Danai O, Abitbol T, Tarazi E, Ezov N, Pereman I, Grobman YJ. Mycelium bio-composites in industrial design and architecture: Comparative review and experimental analysis, Journal of Cleaner Production (2019). [CrossRef]

- E. César, M.A. Castillo-Campohermoso, A.S. Ledezma-Pérez, L.A. Villarreal-Cárdenas, L. Montoya, V.M. Bandala, A.M. Rodríguez-Hernández, Guayule bagasse to make mycelium composites: An alternative to enhance the profitability of a sustainable guayule crop, Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, Volume 47, 2023, 102602, . [CrossRef]

- Laura Sisti, Claudio Gioia, Grazia Totaro, Steven Verstichel, Marco Cartabia, Serena Camere, Annamaria Celli, Valorization of wheat bran agro-industrial byproduct as an upgrading filler for mycelium-based composite materials, Industrial Crops and Products, Volume 170, 2021, 113742, . [CrossRef]

- Sun, W., Tajvidi, M., Hunt, C.G. et al. Fully Bio-Based Hybrid Composites Made of Wood, Fungal Mycelium and Cellulose Nanofibrils. Sci Rep 9, 3766 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Haneef, M.; Ceseracciu, L.; Canale, C.; Bayer, I.S.; Heredia-Guerrero, J.A.; Athanassiou, A. Advanced materials from fungal mycelium: Fabrication and tuning of physical properties. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41292. https://doi:10.1038/srep41292.

- Eugene Soh, Hortense Le Ferrand, Woodpile structural designs to increase the stiffness of mycelium-bound composites, Materials & Design, Volume 225, 2023, 111530, . [CrossRef]

- Liu, T., Hou, Ts. & Liu, Hy. Active Earth Pressure Characteristics of Light Weight Soil with EPS Particles Behind Rigid Retaining Wall. Int. J. of Geosynth. and Ground Eng. 10, 21 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Jinhao Chen, Haibin Wei, Boyu Jiang, Zipeng Ma, Sixun Wen, Fuyu Wang, Preparation and experimental study of saponified slag fly ash foam lightweight soil, Construction and Building Materials, Volume 431, 2024, 136504, . [CrossRef]

- Abdrabbo, F.M., Gaaver, K.E., Elwakil, A.Z. et al. Towards construction of embankment on soft soil: a comparative study of lightweight materials and deep replacement techniques. Sci Rep 14, 29628 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Safa Layachi, Ouarda Izemmouren, Azzedine Dakhia, Bachir Taallah, Elhoussine Atiki, Kamal Saleh Almeasar, Maroua Layachi, Abdelhamid Guettala, Effect of incorporating Expanded polystyrene beads on Thermophysical, mechanical properties and life cycle analysis of lightweight earth blocks, Construction and Building Materials, Volume 375, 2023, 130948, . [CrossRef]

- Gou, L., Li, S. Dynamic shear modulus and damping of lightweight sand-mycelium soil. Acta Geotech. 19, 131–145 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Salman Raza Naqvi, Rumaisa Tariq, Muhammad Shahbaz, Muhammad Naqvi, Muhammad Aslam, Zakir Khan, Hamish Mackey, Gordon Mckay, Tareq Al-Ansari, Recent developments on sewage sludge pyrolysis and its kinetics: Resources recovery, thermogravimetric platforms, and innovative prospects, Computers & Chemical Engineering,Volume 150, 2021, 107325. [CrossRef]

- SUN Min, WANG Xianzhang, XIONG Renying, et al. In-situ fabrication of layered double oxides/biochar composites from municipal sludge and adsorption mechanism elucidation[J]. Chinese Journal of Environmental Engineering, 2023, 17(8): 2716-2727.

- Octavio Suárez-Iglesias, José Luis Urrea, Paula Oulego, Sergio Collado, Mario Díaz,Valuable compounds from sewage sludge by thermal hydrolysis and wet oxidation. A review, Science of The Total Environment, Volumes 584-585, 2017, Pages 921-934. [CrossRef]

- Zhiyang Chang, Guangcheng Long, Youjun Xie, John L. Zhou. Chemical effect of sewage sludge ash on early-age hydration of cement used as supplementary cementitious material[J]. Construction and Building Materials, 322(2022)126116. [CrossRef]

- HE Sheng, XIA Xin, QIN Zhidi, YU Peng. Freeze-thaw Resistance of Concrete based on Fly Ash and Municipal Sludge under Alkali Excitation[J/OL]. Advanced Engineering Sciences, . [CrossRef]

- Jones,M.; Bhat,T.; Huynh,T.; Kandare, E.;Yuen, R.; Wang, C.H.; John, S. Waste-derived low-cost mycelium composite construction materials with improved fire safety. Fire Mater. 2018,1-10. https://doi:10.1002/fam.2637.

- Liucheng Peng, Jing Yi, Xinyu Yang, Jing Xie, Chenwei Chen, Development and characterization of mycelium bio-composites by utilization of different agricultural residual byproducts, Journal of Bioresources and Bioproducts, Volume 8, Issue 1, 2023, Pages 78-89, ISSN 2369-9698, . [CrossRef]

- 3Jones M, Huynh T, Dekiwadia C, Daver F, John S. Mycelium composites: A review of engineering characteristics and growth kinetics. J Bionanosci. 2017;11(4):241-257.

- J. Kung'u, The Phases of Fungal Growth in Indoor Environment, 2016. http://www.moldbacteria.com/mold/the-phases-of-fungal-growth-in-indoor-environment.html. (Accessed 8 June 2024).

- M. Jones, A. Mautner, S. Luenco, et al., Engineered mycelium composite construction materials from fungal biorefineries: A critical review, Materials & Design(2019), . [CrossRef]

- W. Nawawi, K.-Y. Lee, E. Kontturi, R. Murphy, A. Bismarck, Chitin nanopaper from mushroom extract: natural composite of nanofibres and glucan from a single bio-based source, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 7(7) (2019) 6492-6496.

- Lelivelt, R.J.J. The Mechanical Possibilities of Mycelium Materials. Master’s Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2015.

- Schritt, H., Vidi, S., Pleissner, D. Spent mushroom substrate and sawdust to produce mycelium-based thermal insulation composites. J. Clean. Prod. , 2021.313, 127910. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhady, O.; Spyridonos, E.; Dahy, H. Bio-Modules: Mycelium-Based Composites Forming a Modular Interlocking System through a Computational Design towards Sustainable Architecture. Designs 2023, 7, 20. [CrossRef]

- Elsacker, E.; De Laet, L.; Peeters, E. Functional Grading of Mycelium Materials with Inorganic Particles: The Effect of Nanoclay on the Biological, Chemical and Mechanical Properties. Biomimetics 2022, 7, 57. [CrossRef]

- Libin Yang, Zhao Qin, Mycelium-based wood composites for light weight and high strength by experiment and machine learning, Cell Reports Physical Science, Volume 4, Issue 6, 2023, 101424, . [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, A.R.; Bajwa, S.G.; Holt, G.A.; McIntyre, G.; Bajwa, D.S. Evaluation of physico-mechanical properties of mycelium reinforced green biocomposites made from cellulosic fibers. Applied Engineering in Agriculture. 2016, 32, 931-938. DOI:10.13031/aea.32.11830.

- López Nava, J.A.; Méndez González, J.; Ruelas Chacón, X.; Nájera Luna, J.A. Assessment of Edible Fungi and Films Bio-Based Material Simulating Expanded Polystyrene. Mater. Manuf. Process 2016, 31, 1085-1090. [CrossRef]

- M.G. Pelletier, G.A. Holt, J.D. Wanjura, L. Greetham, G. McIntyre, E. Bayer, J. Kaplan-Bie. Acoustic evaluation of mycological biopolymer, an all-natural closed cell foam alternative[J]. Industrial Crops & Products 139 (2019) 111533. [CrossRef]

- Precious O. Etinosa, Ali A. Salifu, Salifu T. Azeko, John D. Obayemi, Emmanuel O. Onche, Toyin Aina, Winston O. Soboyejo, Self-organized mycelium biocomposites: Effects of geometry and laterite composition on compressive behavior, Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, Volume 142, 2023, 105831, . [CrossRef]

- Divnesh Lingam, Sumesh Narayan, Kabir Mamun, Dipanshil Charan, Engineered mycelium-based composite materials: Comprehensive study of various properties and applications, Construction and Building Materials, Volume 391, 2023, 131841. [CrossRef]

- Zhang M, Zhang Z, Zhang R, Peng Y, Wang M, Cao J, Lightweight, thermal insulation, hydrophobic mycelium composites with hierarchical porous structure: Design, manufacture and applications, Composites Part B (2023), doi: . [CrossRef]

- Girometta, C., Picco, A.M., Baiguera, R.M., Dondi, D., Babbini, S., Cartabia, M., Pellegrini, M., Savino, E., 2019. Physico-mechanical and thermodynamic properties of mycelium-based biocomposites: A review. Sustain. 11. [CrossRef]

- Rǎut, I., Calin, M., Vuluga, Z.,Oancea, F., Paceagiu, J., Radu, N., Doni, M., Alexandrescu, E., Purcar, V., Gurban, A.M., Petre, I., Jecu, L., 2021. Fungal based biopolymer composites for construction materials.Materials 14,2906.

- Shen,D.K., Gu, S.,Bridgwater,A.V., 2010.Study on the pyrolytic behaviour of xylan-based hemicellulose using TG-FTIR and Py-GC-FTIR.J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 87,199-206.

- Weng Shifu, Xu Yizhuang. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy[M]. Beijing: Chemical Industry Press, 2016(in Chinese).

- Shao, G. , Xu, D. , Xu, Z. , Jin, Y. , Wu, F. , & Yang, N. , et al. (2024). Green and sustainable biomaterials: edible bioplastic films from mushroom mycelium. Food hydrocolloids(Jan. Pt.B), 146.

- Salman Raza Naqvi, Rumaisa Tariq, Muhammad Shahbaz, Muhammad Naqvi, Muhammad Aslam, Zakir Khan, Hamish Mackey, Gordon Mckay, Tareq Al-Ansari, Recent developments on sewage sludge pyrolysis and its kinetics: Resources recovery, thermogravimetric platforms, and innovative prospects, Computers & Chemical Engineering,Volume 150, 2021, 107325. [CrossRef]

- Ru Liu, Ling Long, Yan Sheng, Jianfeng Xu, Hongyun Qiu, Xiaoyan Li, Yanxia Wang, Huagui Wu, Preparation of a kind of novel sustainable mycelium/cotton stalk composites and effects of pressing temperature on the properties, Industrial Crops and Products, Volume 141, 2019, 111732, . [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).