1. Introduction

Our world is highly complex and interconnected, and decision-making by managers is now made more difficult by unprecedented complexity arising for several reasons, including the increasing role of stakeholder capitalism [

1], increasing diversity and complexity of social structures [

2], rapid technological advancement including AI [

3], changing population dynamics including a growing global population [

4], increasing urbanisation that is limiting natural resources [

5], and emergent phenomena such as unpredictable market behaviour, increases in natural disasters, and social movements, often large-scale [

6,

7,

8]. One feature which is a foundational force behind the complexity of our world is the interdependence of societies, economies, and technologies, a factor which has reshaped the complexity of human interactions [

9]. There are now global networks of transportation, communication, and trade, which connect to humans through digitisation. Financial systems and economies are therefore interdependent, generating emergent and unpredictable phenomena and adding layers of complexity to modern life [

10].

One grand challenge we face is that of sustainable exploration and development that balances the needs of the economy, the environment, and social well-being. Sustainability exploration is often addressed through the concept of grand challenges of unprecedented scale, interconnectedness, and complexity and requiring global efforts in understanding and response [

11]. De Ruyter et al [

12] refer to the Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the UN in 2015 and the need for targeted action to back up academic conversations via societal and political action and working together with industry. The grand challenges of climate change, food security, and inequality are deeply interconnected within our globalized world. These highly interdependent systems are difficult to understand and control and may pose serious threats to society due to their instability, requiring global cooperation [

13]. In addition, technological disruption presents issues around privacy and data protection and the rapidly escalating digital technological developments, including AI, create both benefits and risks. Some are concerned about the impact of automation on employability [

14]. Others raise concerns about misinformation and the capability of agents to manipulate people’s opinions [

15]. Both automation and misinformation are significant difficulties that demand a multidisciplinary approach, involving technological innovation, ethical guidelines, and policy interventions, as well as enhanced contemporary management skills to govern under the weight of all these potential problems. Clearly making wise decisions taking account of all of the information in such complex conditions can incur risk.

The interaction between people and machines itself represents a significant grand challenge within contemporary society. While enormous progress has been made in developing powerful computational systems, the creation of truly intuitive and meaningful interactions between people and machines is still some way off. Human communication is quite sophisticated and nuanced, and this can lead to frustration when people have to adapt their behaviour to fit in with the machines’ limitations, rather than vice versa. While the focus is often on how people could adapt to machines, perhaps it would be wise to consider how machines can be designed to better serve human ways of thinking. Interactions that complement human thinking rather than competing with it would be valuable. The goal would be creating collaborative systems that enhance human capabilities but at the same time respecting human involvement and human judgement. As the machines are more and more integrated into our lives, questions of privacy inevitably emerge. We also want to ensure that human to human interaction is not decreased as human machine interaction builds. How do people work out how to trust machines? Machine decision-making processes need to be transparent and understandable to people. This matter encompasses a range of issues, including ethical concerns, social implications, and technological impacts on human behaviour, management decision-making, and societal structures [

16,

17]. This paper examines the interaction between humans and machines and critically analyses how this interaction can be leveraged to face these difficulties effectively, proposing a conceptual model to thrive in conditions of complexity and high levels of uncertainty. In the past, traditional decision-making systems often have been hierarchical, but this style of decision-making is not suited to the level of complexity of the current era. Cooperative human-machine decision-making is necessary [

18].

The paper discusses the potential of the field of Cybernetics as a way of combining and integrating the potentials of AI and humans, to give our planet the best chance of flourishing into the future. Harari [

19] reflects on the future of human-machine interactions, supporting the potential for cybernetic systems to reshape society through collaboration. Cybernetics is an interdisciplinary field that explores control and communication in complex systems including both living organisms and machines. Cybernetics views humans and machines as information processing systems which, through cooperation, can lead to better design and greater collaborative capabilities [

20]. The field investigates how systems use information feedback and regulation to adapt, adjust their behaviour and maintain stability and equilibrium as the environment changes. Information flow is obviously critical. How humans interact with and are influenced by technology is a critical feature of contemporary life, and Cybernetics presents a promising way of optimising this interaction between humans and machines for the benefit of all, and to assist managers in making wise and sustainable decisions.

2. Cybernetics 3.0 and Human Machine Interactions

The overarching theoretical framework of this paper is Cybernetics 3.0. The field of cybernetics, derived from the Greek word "kybernetikos" meaning "good at steering," was established by Norbert Wiener in the 1940s. The field is highly relevant today, being a discipline that examines systems, emphasizing the interactions and dynamics among humans, technology, and environment. Systems thinking is a foundational perspective for understanding complex interconnected issues, giving a holistic approach to viewing problems and emphasising the relationships and interactions between various components. Systems thinking is powerful as a way of understanding complex relationships involving linkages and feedback loops. If we think of a simple example, two nations may hate each other because they do not know each other and they will not get to know each other because they hate each other. Actions have consequences. We are all familiar with the concept of the self-fulfilling prophecy as a feedback loop in which a self reinforcing system, in this case the initial belief whether true or false, leads to its own confirmation. Cybernetics as a discipline builds upon and extends systems thinking in its recognition that systems are complex, consisting of many feedback loops that influence their operation, variability, and evolution throughout time toward desired outcomes. Cybernetics, therefore, studies how systems regulate themselves and maintain stability and can give key insights into how complex systems can be guided and managed. Wiener's work was widely acknowledged as the founding of “cybernetics” as a distinct scientific field. The primary objective of this field is to examine how best to control complex systems, be this in the field of transportation, services, health, education, and many other domains [

21]. The evolution of cybernetics provides valuable insights into the changing understanding of human-machine interaction. Over time, there has been a move away from understanding machines as being separate from human life towards viewing machines as being extensions of people and reflections of human action.

Cybernetics 1.0, developed by Arturo Rosenblueth and Norbert Wiener in the 1940s [

22] was concerned with observed systems, and feedback. Cybernetics 1.0 focused on analogies between living beings and machines, particularly the application of biological feedback mechanisms to technology. Wiener realized that feedback could be replicated in machines if they met certain criteria, including the presence of an input and an output, a sensor to detect the effector's values, and an instrument to compare this state to a desired final state. Cybernetics 1.0 viewed machines as imitations of biological systems, replicating feedback mechanisms.

Cybernetics 2.0 emerged in the 1970s and shifted the focus from observed systems to observing systems. Heinz von Foerster, Margaret Mead, Gregory Bateson, Humberto Maturana, and Francisco Varela were key figures in this development [

23], introducing the “observer subject” and rejecting the belief in objectivism of the first wave. Maturana and Varela's concept of autopoiesis, which describes a system where the observer and the observed are interlinked in a continuous feedback loop, became a foundational concept in Cybernetics 2.0. However, emphasising the self-referential nature of consciousness, where the ego primarily interacts with itself, leads to an overly subjective perspective that reduces cybernetics to a theory of how we acquire knowledge. While Cybernetics 2.0 attempted to explore the observer’s role more deeply and challenged the traditional view that the observer and the observed are separated, it was not able to fully overcome the tendency towards subjectivism.

Cybernetics 3.0, developed by Luis de Marcos Ortega, Carmen Flores Bjurström, and Fernando Flores Morador, seeks to overcome the limitations of both Cybernetics 1.0 and 2.0 by understanding self-organization not as an inherent property of systems but as a product of human action, emphasizing the role of people in the system [

24]. This approach sees machines as human surrogates rather than as independent entities and considers feedback a specific type of “human doing”. Cybernetics 3.0 reframes the relationship between people and machines, recognizing the human origin of feedback and emphasizing the human action within the system, focusing on the specific role of humans in shaping systems. In this context, feedback mechanisms, commonly associated with both living beings and machines in earlier cybernetic thought, are reframed as a specific form of human doing. By emphasizing human action as the basis for organization, Cybernetics 3.0 introduces a new way of thinking about the observer and the observed. The observer is no longer simply passively observing a system: instead, the observer is actively engaged in creating and shaping the observed system through their actions.

This perspective has profound implications for how we understand the grand challenge of human-machine interaction (HMI): if we see machines as extensions of human action, then humans bear a greater responsibility for the actions of the machines and their consequences. Where there is co-evolution, where human action shapes the machine’s development, and machines also influence human actions. Cybernetics as a science aims to ensure that both people and the environment can benefit from the evolution of technology, and gives us a framework to understand the systems in which we are embedded (including ourselves) as complex adaptive systems that are evolving continuously and adapting to our environment [

25]. Cybernetics 3.0 highlights the need for ethical considerations in the design and development of machines, recognizing that these choices are not neutral but instead reflect human values and intentions. We must consider both the components of a system and their interactions, a concept that is necessary for understanding complex systems and their behaviour. By recognising the human origin of feedback and emphasising human action, Cybernetics 3.0 provides a more sophisticated and human centred perspective on the interaction between humans and machines, and the way in which mutual shaping occurs between people and technology. This has implications for both individual and collective well-being. This perspective is significant in addressing the complex challenges and opportunities presented by technological advancements, particularly in the area of Web 3.0 and the increasing integration of AI into various aspects of life. The implications for human-machine decision-making (HMDI) are many and varied.

3. Systems Thinking in Complex Decision-Making Contexts

The deep interdependence we now see has developed quite quickly. The impacts are only now becoming clearer. Emergence, or the arising of novel properties or behaviours at the macro level which are not present within the individual components, is a fundamental concept in complex systems [

26]. Some forms of unexpected emergence from these linkages will be good, but some will be bad. We have seen many examples of the way catastrophic failures can occur due to this interdependence. The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) as an example demonstrates cascading failures that can arise from tightly coupled systems. We can see that problems in one sector spread through financial networks to affect areas of life around the world: local problems can quickly become global, affecting people far removed from the original issue. Goldin and Vogel [

27] identify the failure of sophisticated global institutions to manage underlying systemic risk. The pandemic is another example of the interconnectedness of systems producing damaging emergence. More integrated thinking would have highlighted the interconnections and enabled systems thinking. A multidisciplinary approach that accepts information from various perspectives could enable superior engagement with people, especially vulnerable people [

28,

29]. As noted by Sturmberg, et al. [

30], awareness of the many interdependencies among the various aspects of the health system would have enabled a much better response and the building of resilient and healthy communities. The pandemic response exposed a critical flaw in modern systems: the lack of integration and collaboration between various fields of knowledge. Identifying the connections between the various aspects of health and well-being would have led to a wiser and more inclusive response [

31]. In fact, the pandemic is a powerful illustration of the dangers of compartmentalisation and a failure to pick up on causal connections. Recognising the connections between human and the planet’s health and fostering collaboration across networks enables the building of more resilient and equitable systems, and these systems will be more capable of navigating future crises as these arise.

There are unique difficulties in making decisions in complex systems due to the interconnected nature of the components, nonlinear relationships, and the dynamic interactions in these environments [

32]. Complex systems such as ecosystems, cities, or financial markets exhibit emergence and this cannot be predicted by analysing the individual components in isolation. Compartmentalisation and a silo mentality creates an “us” versus “them” mindset. Sometimes people are not aware of the existence of a silo mentality. As noted by Cilliers and Greyvenstein [

33], people who are inside a silo may believe that they are actually seeing the problem in a holistic way. Silos may encourage groupthink and a sense of superiority. A scoping review by Bento, et al. [

34] noted that siloed organisational behaviour does not sit well with complexity, which requires instead webs of interaction and communicating networks. Silo mentality is in effect the absence of systems thinking and of a clear vision of the whole organisation, reducing efficiency and morale as well as negatively impacting the organisational culture. Silos create a reluctance to share information and to cooperate across departments and units. People with power also may wish to preserve the status quo [

35]. Current siloed decision-making is a major barrier in addressing such complex matters. Siloed solutions cannot address interconnected problems. What is needed is holistic understanding and wisdom. Systems thinking practices could assist people to anticipate unintended consequences and better comprehend the role of people in shaping systems.

Decision-making against the background of this intense interconnectedness requires not reductionist silo and thinking but wisdom and holistic thinking. Networks exacerbate existing problems such as inequality, scarcity and the disempowerment of many groups of people. Decision-making needs to be different now. Understanding feedback loops is critical. Systems thinking enables people to view the second and third order effects that can occur often after a time delay and often counterintuitive, identify the feedback loops, and recognise that linear cause-and-effect thinking will not work. As asserted by Senge [

36]: “Systems thinking is a conceptual framework, a body of knowledge and tools that has been developed over the past 70 years to make full patterns clearer, and to help us see how to change them effectively.” While there are many perspectives on systems thinking, the main themes refer to the complex nature of systems, its closeness to big picture thinking, the value of holistic thinking, multidimensional thinking and focusing on the big picture of the system in order to obtain more effective solutions. This is a fast-growing area of literature with applications in various domains including management, engineering, education, healthcare, and others. Risk assessment needs to take account of systemic risk and look for contagion pathways. Stakeholder management must be changed as well. A broader range of stakeholders, moving well beyond local stakeholders, should be involved. There will be many competing interests. The decision-making process needs to be flexible and adaptable, using scenario planning to test multiple future possibilities. Cooperation frameworks should be at the forefront and clear communication with clear chains of responsibility will be necessary. Responses need to be rapid under these circumstances.

Prescott [

28] used the parable of the blind men and the elephant to illustrate the impact of holding limited perspectives when we try to understand complex systems. The blind men examine different parts of the elephant and come to completely different understandings of its nature, and in the same way people situated in specialised medical fields, for example, can operate in isolation and not comprehend the interconnected nature of people’s health and planetary health. This prevents us from seeing the whole picture of interconnected systems. Lack of communication between people in various roles who focus on narrow specialised areas provides fragmented solutions that are inadequate in addressing the root causes of the problem at hand. Fragmented approaches that do not appreciate that biological, psychological, social, and cultural aspects of health are all connected are inadequate. The degradation of ecosystems is also connected with human disease. Encouraging cross discipline and cross specialisations communication flow can break down the silos. Embracing diverse perspectives regarding different ways of viewing and living in the world can provide a cultural shift in a positive direction, encouraging ethical and sustainable decision-making [

37]. A competitive and territorial attitude is not helpful in encouraging collaboration: what is really needed is greater openness and a willingness to learn, as well as a connected-up view of the scenario at hand. When we consider HMI and especially HMD that arises, systems thinking and Web 3.0 are foundational.

4. Human-Machine Interaction and Decision-Making

HMI is a critical grand challenge now. It also presents a specific example of decision-making under complexity. The interaction is increasingly adapting to human habits and needs, but there are still questions in balancing human control with machine capabilities, especially in the case of sustainability and complex decision-making environments. The relationships between humans and technology are complex and rapidly evolving. Understanding these relationships will be critical for developing effective solutions to complex problems. We need to understand how we can develop better interfaces and better partnerships between people and machines. As we develop technological solutions to address the various grand challenges now being faced, this interaction becomes increasingly important. There are many issues. Ensuring that technological solutions respect human rights and promote fairness is one of them. We also need to develop technologies that are accessible and beneficial to all users. Through HMI, we can leverage big data and analytics to inform policy and actions that will benefit people.

The introduction of Web 3.0 is characterized by the integration of advanced technologies that enable more intelligent, interconnected, and user-centric experiences. Web 3.0 aims to enhance the functionality of the web by allowing machines to understand and interpret data in a more human-like way. AI and semantic technologies in Web 3.0 enable more personalized and contextually relevant content delivery. For example, streaming services can offer tailored recommendations based on a deeper understanding of user preferences, utilizing machine learning algorithms and vast amounts of user data (Netflix Technology Blog, 2017). Currently there are a range of applications of (AI) within decision-making, with increasing integration and collaboration mainly through AI systems augmenting human decision-making capabilities within a range of industries and sectors. AI is increasingly used for decision support, although this tends to be focused upon lower-level routine decisions rather than intricate, high-stakes decisions necessitating human knowledge [

38]. However, the rapid development of the use of AI predicts that this scenario is likely to change [

39]. Already financial services are applying autonomous AI decisions in services such as loan approvals, but the incorporation of human judgement in AI-facilitated decision-making, is increasingly recognised a critical domain [

40].

Certainly, we see many applications of AI now and the rollout is very rapid. A report by Meissner and Narita [

39] shows that 35% of Amazon’s revenue arises from AI recommendations. Davenport and Ronanki [

41] suggest that there are benefits in incorporating AI into commercial decision-making aiming to enhance decision-making precision, velocity, and efficacy, while simultaneously decreasing expenses and optimizing processes across several sectors. For example, AI can rapidly analyse big data and identify patterns that humans may not be able to detect [

42]. AI is also useful in handling data-intensive, repetitive tasks, enabling faster, consistent, and accurate decisions [

43]. AI can make good predictions based upon the large training data set and this can be of assistance within commercial decision-making; and therefore human labour and input can therefore be reduced for tedious processes [

44]. AI has decision-making strengths around rapidly processing and analysing large volumes of data, identifying patterns that may be overlooked by people. This is a very valuable capability in domains such as financial trading where very rapid decisions are needed. The recognition of subtle patterns provided by AI can give people valuable foresight, helping them to anticipate potential outcomes and prepare for various scenarios. There are modelling capacities now available that allow for sophisticated simulations, which can be used by people to understand the consequences of their decisions and refine their strategies.

HMD is an evolving field with significant implications. HMD moves beyond basic interaction to joint decision processes, combining human judgement with machine processing capabilities. HMD bridges the gap between basic interaction and complex decision-making and is a crucial step in developing more sophisticated approaches to challenging problems. This field considers, among other things, how to allocate decisions between humans and machines. The integration of AI and human capabilities in decision-making processes can enhance efficiency, accuracy, and scale. Viewing both styles as complementary can lead to added value. Humans and AI working together can leverage the strength of each to produce collaborative intelligence [

45]. HMD is characterized by intuition, creativity, experience, and ethical awareness, in addition to analysis. For example, healthcare professionals rely on both their training and their empathy to make beneficial patient-care decisions, considering factors that may not be easily quantifiable, such as a patient's emotional state or quality of life concerns. Peter and Reimer [

48] devised a framework which describes the 7 kinds of capability that AI can provide us existing in a tiered stack, with each level building upon the one below. Pattern recognition is a basic capability provided by AI, and we can see this kind of capability occurring in everyday life, for instance, through facial recognition. Classification, in which AI can organise items into wholes, is another useful attribute. Prediction of the future based upon the past, recommendations of suitable options such as we see popping up based upon our previous buying patterns, automation with a reasonable degree of autonomy, generation of new content that mimics the training data pool, and interactions of the kind that we are now familiar with by using chat bots, are all very useful capabilities provided by AI, but they fall short of integrating human judgement into the decision-making scenario.

There are various hybrid decision-making models and frameworks. HMD occurs along a spectrum from machines being in complete control right through to adaptive decisions in which both systems learn and evolve from feedback [

46]. At the basic level, machines operate independently to make decisions, and an example is that of self-driving cars. At the next level, we see decision support systems in which HMD is enhanced through data driven insights such as medical diagnostics where AI tools assist doctors via suggesting possible diagnoses [

49]. The next level is collaborative decision-making where there is a dynamic interaction between people and machines and both parties contribute to the decision-making process. In military operations, decision support systems provide soldiers with real-time data and strategic options that are then evaluated by a person. Augmented decision-making occurs when machines provide enhanced information and visualisation tools, such as dashboards and predictive analytics. Customer data can be used to provide salespeople with detailed insights into market trends. Human in the loop (HITL) systems ensure human oversight over automated systems, and this is particularly important when the environment is high-stake. In this kind of system, human decision-makers can intervene to override algorithmic decisions such as we see in financial trading systems. Adaptive decision systems are a more dynamic and evolving approach to human-machine decision-making, where a system’s performance improves from incorporating feedback from both machine analysis and human input. In personalised medicine, ftreatment recommendation systems can adapt based upon feedback from the patient and the clinician and continuously improve their accuracy.

5. Implications of Cybernetics 3.0 for Human Machine Decision-Making

Cybernetics 3.0 represents an evolution in systems thinking that is very relevant to today’s interconnected dilemmas incorporating consciousness, human values and ethics into systems thinking. This can contribute to solutions in various ways, including the integration of human consciousness into understanding HMI: recognising that observers and participants are part of the system, incorporating human values and ethics into system design, and bridging the gap between the technical and the human. The recognition of human acting systems and the inherent role of human action in shaping systems helps us to consider the dynamic interplay between people and machines, with both entities influencing each other’s behaviour. Cybernetics 3.0 helps us to understand that human systems can learn how to learn through second-order learning; people can come up with adaptive responses as difficulties emerge and can build resilience through continuous evolution. Cybernetics 3.0 encourages us to think about tools for better group decision-making, ways of sharing knowledge across silos, and ways of integrating various differing perspectives. It is clear from this discussion that by integrating Cybernetics 3.0 principles into the design of human machine operation the consideration of multiple factors is enabled that can elevate ethical considerations in the decision-making process, including personal moral philosophy [

47].

Application of Cybernetics 3.0 in real-world situations would include for example healthcare, where improved diagnosis and treatment could arise through a collaborative approach between medical professionals and AI powered diagnostic tools. Personalised medicine could be enhanced through adaptive decisions as the AI systems learn continuously from patient and clinician feedback and a dynamic series of iterations leads to improvement. A proactive approach to mitigating bias is suggested within this approach, in which medical practitioners and AI developers collaborate to curate the training data, implement bias detection, and ensure human oversight. Other domains in which Cybernetics 3.0 principles could bring beneficial outcomes could include financial trading, in which while AI algorithms can detect underlying patterns and trends that could be missed by humans, human traders can bring their experience and intuition into the arena. A collaborative approach between human traders working closely with AI systems leverages the strength of both, as continuous feedback from human traders could refine the algorithms and lead to a co-evolutionary improvement process. We can also think of the high-stakes and complex nature of military operations where decision support systems can provide real-time data, situational awareness and suggest strategic options: however, human judgement and ethical considerations need to be entrained in evaluating the AI generated recommendations.

This provides a helpful lens for considering future grand challenges that arise from HMI. Through acknowledging the complexity of human systems via the lens of Cybernetics 3.0, we can anticipate unintended consequences that might arise from what seem to be simple interactions between people and machines. Complexity can arise when new technologies are introduced or existing systems are modified, and this can create a ripple effect throughout the interconnected web of human and technological systems, which could lead to unforeseen emergence. The emphasis on human agency highlights the need for responsibility in the design and deployment of new technologies. If humans are active participants in shaping systems, they are also accountable for their actions and their consequences. Ethical implications of technology will be both good and bad. Economic, ecological and other systems remind us to consider the broader implications of HMI as these unfold across many domains. Understanding these complex relationships will be crucial for navigating the dilemmas posed by technologies like AI, automation, and data driven systems.

Cybernetics 3.0 recognises the agency of both people and machines. Machines are not now viewed as passive tools controlled by humans. Machines, especially those with advanced capabilities such as AI, can influence humans and can shape the dynamics of systems in ways that we may not immediately observe. This kind of mutual influence has implications for human flourishing into the future. As machines become more sophisticated, humans need to adapt and coevolve alongside them. This will need ongoing learning, critical thinking, and the ability to navigate complex systems as we increasingly see a blurring of the line between human and machine agency. We can already see HMI augmenting human capabilities. It will be necessary to ensure that this augmentation is in the direction and purpose of human flourishing, rather than undermining human autonomy or well-being. Core principles of Cybernetics include feedback loops and therefore more responsive systems, the design of more intuitive interfaces, recognition that systems can learn from user behaviour and adjust, such as we see in the provision of personalised recommendations based upon previous behaviour patterns. Understanding how people process information can minimise errors in systems such as the provision of warning messages anticipating common user errors.

Reversing the grand challenges notion, there are some grand opportunities here. Grand opportunities is a phrase now appearing in the literature: for example Jyothi, et al. [

48] use the phrase to describe creating wealth from separating rare-earth elements from secondary waste, and Bhattacharya, et al. [

49] discussed five grand opportunities arising from computational breakthroughs in the field of single cell research. Speaking of people acting together with machines, in the best-case scenario, there are grand opportunities that could virtually eliminate poverty and provide better education and health care globally. As machines become more and more capable, human autonomy needs to be highlighted and maintained. There is the need for wisdom in technological development. Such development should not solely be driven by technological advancements or economic gains, but instead a consideration of broader social and ecological impact of new technologies must also be in the mix. Seemingly isolated innovations can have a ripple effect throughout interconnected systems. Therefore, holistic evaluation beyond a narrow focus on efficiency and productivity is necessary. People will need to think long-term and consider the well-being of future generations. There is a need to ensure that the benefits of technology are distributed equitably, and to consider potential biases and discrimination that can arise when algorithms make decisions.

This paper suggests that the emergence of Cybernetics 3.0, building upon the foundations of Web 3.0 but with its focus upon human inputs, might provide the kind of impetus needed to examine the responsibility of people to bring themselves formally into the equation of HMI and HMD. Human wisdom of a holistic sort is needed in appreciating what machines can do and what people must do. People have unique characteristics, including the ability for holistic thinking. Machines lack emotion and ethical understanding. Critical thinking, wisdom, stepping back and applying metacognition are all needed as we face the grand challenge of HMI. Cybernetics offers new paradigms to understand this growing field and, through it, the arrival of collective intelligence that can enable us to make more informed decisions. Integrating advanced machine learning with human oversight can provide constructive ways forward. The approach recognizes that while machines excel at processing vast amounts of data and identifying patterns, humans possess invaluable qualities such as intuition, creativity, and ethical judgment that are crucial for complex decision-making. Integrating these complementary capabilities could potentially lead to outcomes that are superior to what either humans or machines could achieve independently. When machines and humans work in tandem, each contributes their strengths to the decision-making process. Collaborative Cybernetics takes a systems perspective, considering the interplay between the decision-makers, the design processes and the environment. There is a focus on teams regulating and adapting their activities to changes in the design process. Information flows between team members and how this influences decision-making is specifically considered. Understanding how teams work towards common high-level goals while at the same time managing their subgoals and constraints is part of the process.

Interconnectedness is a fundamental principle for addressing complex challenges. Planetary health questions are interwoven, underscoring the need for transdisciplinary collaboration. Individual well-being, community empowerment and environmental sustainability are all interconnected. We need a paradigm shift in our approach to development and progress. Shifting away from externally imposed solutions to inner transformation and the need for a deeper understanding of well-being and flourishing presents such a shift. Cybernetics 3.0 offers a compelling framework for reimagining the relationship between people and technology in the context of empowerment, sustainable development and planetary health. Social, ethical, and philosophical dimensions need to be considered to bring about the responsible and transformative implementation of human-machine collaboration. Collective intelligence that is enabled by Web 3.0 and integrated into Cybernetics 3.0 systems gives us a promising approach for addressing grand challenges arising in this interaction. Ethan Mollick in his book entitled “Co-intelligence” written in 2024 discusses the incredible opportunities arising from a positive partnering and collaboration between humans and AI. At the opposite end of the spectrum, some have suggested that we are rapidly losing the ability to apply critical thinking because of this development [

50]. Clearly this is an area of concern.

6. A Cybernetic Model of Human AI Collaboration

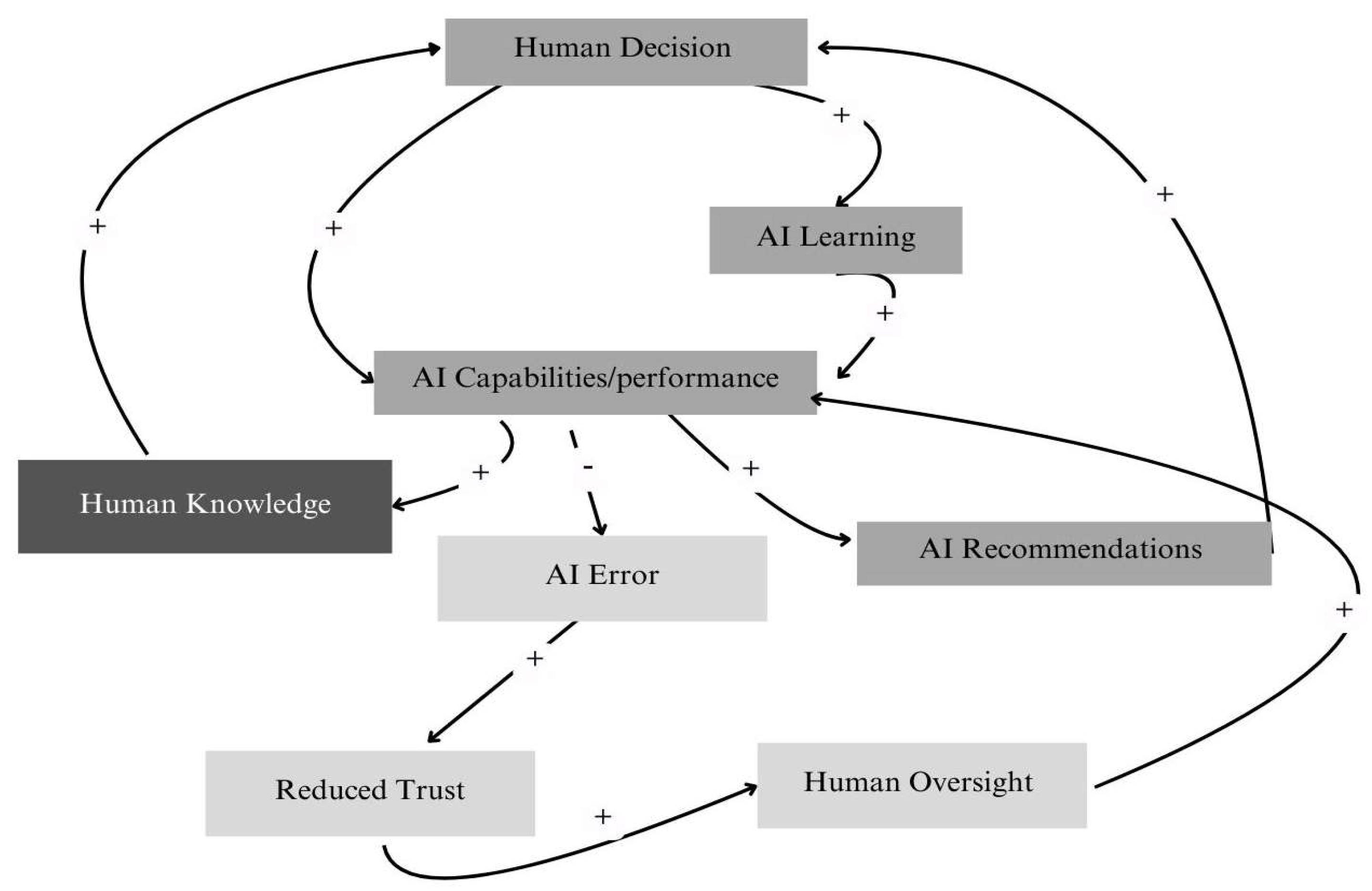

Causal loop diagrams (CLDs) provide an elegant approach for visualising and analysing the complex dynamics between humans and AI in decision-making systems. As visual tools that represent interdependent variables and their relationships, CLD is help us move beyond linear thinking to understand the emergent behaviours arising from feedback loops in complex systems. The diagrams consist of nodes representing key variables connected by arrows showing causal links, with loops that can be either reinforcing (positive) or balancing (negative). Reinforcing loops are self amplifying, while balancing loops are self-correcting. CLDs are helpful in visualising complex systems and identifying nonobvious virtuous or vicious cycles created via feedback loops. CLDs therefore can be used to describe the basic causal mechanisms which generate system behaviour over time [

51]. They also help people to break away from linear thinking towards systems thinking. The earlier example of two nations who hate each other because they don’t get to know each other, and will not get to know each other because they hate each other, is a clear illustration of a reinforcing feedback loop or vicious cycle, in which the initial lack of knowledge leads to hate and that hate then prevents actions that would lead to increased knowledge such as communication and cultural exchange. The continued lack of knowledge further reinforces the hating attitude and perpetuates the cycle.

Figure 1 presents a CLD that captures three critical feedback loops in human-AI collaboration: the core learning loop, the trust oversight loop, and the recommendation feedback loop. The core AI-human learning loop demonstrates how improved human decisions enhance AI capabilities, which in turn augment human knowledge, creating a virtual cycle of continuous improvement. However, this cycle requires careful governance to prevent unintended consequences. The trust oversight loop introduces an essential balancing mechanism whereby increased oversight improves AI performance through monitoring: better performance reduces errors while worse performance increases them. When errors increase, trust decreases, leading to heightened oversight and subsequent performance improvements. This self-regulating loop maintains system stability by counteracting deviations from desired performance levels. The recommendation feedback loop illustrates the dynamic interaction where AI provides suggestions to support human decision-making. The quality of human decisions influences AI performance, which shapes future recommendations. This loop highlights the co-evolutionary nature of human-AI decision systems.

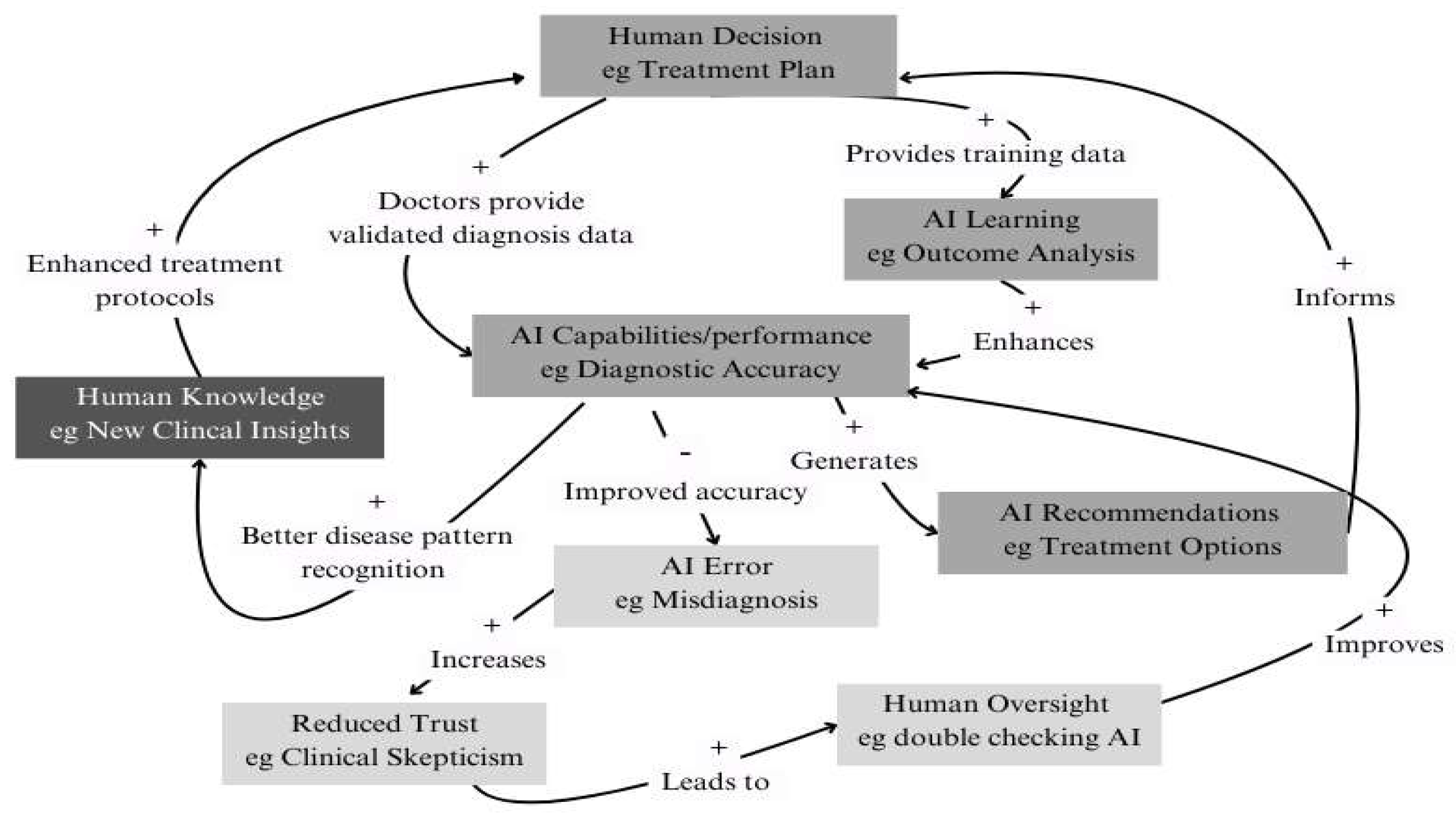

To illustrate the practical application of this model, let us consider the healthcare domain (

Figure 2). Here the core learning loop manifests as medical professionals making treatment decisions and recording outcomes, which improves AI diagnostic capabilities. Their interactions with AI tools provide valuable feedback for algorithm refinement. The trust oversight loop becomes particularly critical: if an AI system misidentifies a tumour, decreased trust leads to enhanced review processes that ultimately improve accuracy. The recommendation loop shows how AI can analyse patient data to suggest treatment options that doctors evaluate using their expertise, leading to AI learning and improvements in future recommendations. The negative loop indicates that an increase in AI capabilities/performance leads to a decrease in AI errors.

This cybernetic model reveals that while AI provides powerful analytical capabilities, human judgement remains essential for oversight, contextual understanding, and ethical considerations. The framework suggests that optional outcomes emerge from carefully designed feedback mechanisms that leverage both human and machine intelligence while maintaining appropriate checks and balances. Cybernetic principles can inform the design of human AI collaborative systems. This framework provides a theoretical foundation for understanding the delicate balance required between automation and human agency in complex decision environments.

7. Conclusion

Using the lens of Cybernetics 3.0, this paper has demonstrated that human-machine decision-making represents both a grand challenge and a grand opportunity for contemporary society. The integration of human judgement with machine capabilities offers unprecedented potential for addressing complex problems, but success depends critically on maintaining an appropriate balance between machine autonomy and human oversight. Human judgement remains indispensable for contextual understanding, including the understanding of ethical questions, and ensuring that decisions align with societal values and human flourishing. Web 3.0 technologies, while transformative in their impact on human-machine interaction, must be developed thoughtfully and purposefully. The principles of Cybernetics 3.0, with its emphasis on human agency and systems interconnectedness, provides a compelling framework for navigating this evolving landscape. The causal modelling presented in the paper demonstrates how feedback mechanisms can be designed to optimise the complementary strengths of human and machine intelligence while maintaining essential safeguards.

Critical to success will be the prioritisation of human capabilities such as creativity, critical thinking, and complex problem-solving, alongside technological advancement. The future of human-machine collaboration must be shaped by a commitment to enhancing, rather than diminishing, human agency. The healthcare example provided illustrates how carefully designed feedback loops can enable continuous improvement while preserving essential human oversight. Looking ahead, several imperatives emerge. First, technological development must be balanced with considerations about human well-being. Second, we must maintain human influence over critical decisions while leveraging AI’s analytical capabilities. Third, organisations need to address potential biases in algorithms and ensure equitable access to technological benefits. Finally, a culture of continuous learning will be essential as these technologies evolve rapidly.

The framework presented in this paper suggests that by embracing cybernetic principles in the design of human-machine systems, we can work towards outcomes that will enhance human flourishing while addressing increasingly complex societal challenges. The future of human-machine collaboration holds immense promise, but realising this potential will require careful attention to the dynamics of feedback, learning, and system adaptation. Only through such thoughtful integration can we ensure that technological advancement serves the broader goals of human and planetary well-being.

8. Limitations and Future Research

While this paper presents a theoretical framework grounded in cybernetic principles, several limitations warrant acknowledgement. First, as a conceptual analysis, the paper would benefit from empirical validation across different organisational contexts and domains. The causal loop diagrams, while theoretically sound, would benefit from systematic testing in real-world settings to verify their practical utility and identify potential refinements. A significant limitation lies in the rapidly evolving nature of AI technology itself. The frameworks and models presented in this paper may need continuous adaptation as new capabilities emerge. This analysis primarily focuses on current technological capabilities: future developments may introduce new dynamics not captured in the current models. The healthcare example, while illustrative, represents just one domain of application. Different sectors may present unique challenges and requirements for human-machine collaboration not addressed in the current framework. Cultural variations in approaches to technology adoption and decision-making processes also merit further investigation.

Several promising directions for future research emerge from these limitations. The development of specific metrics and evaluation frameworks for assessing the effectiveness of human-AI collaborative systems would be useful. This would include examining not just operational efficiency but also the broader impacts on human well-being, job satisfaction, and organisational culture. Future work should also explore the psychological dimensions of human AI interaction: in particular, how different personality types and cognitive styles influence the effectiveness of collaborative decision-making. Understanding these individual differences could inform more nuanced approaches to system design and implementation. Research into educational and training approaches would also be valuable. As these systems become more prevalent, understanding how to develop the necessary skills for effective human-AI collaboration will be increasingly important. This will include both technical competencies and the development of critical thinking and ethical judgement capabilities. These additional research directions could help to develop practical guidelines for the implementation of these systems in ways that enhance human capability and agency.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the research and writing of this article. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

the authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Economic Forum. Stakeholder capitalism: metrics and disclosures. 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org (accessed on November 2024).

- Pew Research Centre. In Global demographic trends and ethnic diversity; 2021.

- Van Kuiken, S. Tech at the edge: trends reshaping the future of IT and business. 2022. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/tech-at-the-edge-trends-reshaping-the-future-of-it-and-business.

- Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA). 2018 Revision of World Urbanisation Prospects; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2018. Available online: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/.

- Huang, S.-L.; Yeh, C.-T.; Chang, L.-F. The transition to an urbanizing world and the demand for natural resources. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2010, 2, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organisation (WMO). State of the global climate. 2021. Available online: https://wmo.int/publication-series/state-of-global-climate.

- OII. Europe Annual Report 2020. EU2020. Available online: https://www.oiieurope.org/oii-europe-annual-report-2020/.

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerabliity. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/.

- Castells, M. The rise of the network society; John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J. Global complexities. In Frontiers of globalization research: Theoretical and methodological approaches; Springer, 2007; pp. 151–162. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Byl, C.; Slawinski, N.; Hahn, T. Responsible management of sustainability tensions: A paradoxical approach to grand challenges. In Research Handbook of Responsible Managementt; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2020; pp. 438–452. [Google Scholar]

- de Ruyter, K.; Keeling, D.I.; Plangger, K.; Montecchi, M.; Scott, M.L.; Dahl, D.W. Reimagining marketing strategy: driving the debate on grand challenges. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2022, 50, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbing, D. Globally networked risks and how to respond. Nature 2013, 497, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Robots and jobs: Evidence from US labor markets. Journal of Political Economy 2020, 128, 2188–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; Rand, D.G. The psychology of fake news. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2021, 25, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, N.; Yudkowsky, E. The ethics of artificial intelligence. In Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; Rock, D.; Syverson, C. Artificial intelligence and the modern productivity paradox. In The economics of artificial intelligence: An agenda; 2019; Volume 23, pp. 23–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, T. Telerobotics, Automation, and Human Supervisory Control; MIT Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Harari, Y.N. Homo deus; Random House: NY, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, N. Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine; MIT Press, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Hipel, K.W.; Jamshidi, M.M.; Tien, J.M.; White, C.C., III. The future of systems, man, and cybernetics: Application domains and research methods. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part C (Applications and Reviews) 2007, 37, 726–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblueth, A.; Wiener, N.; Bigelow, J. Behavior, purpose and teleology. Philosophy of Science 1943, 10, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, D.A. Cybernetics: from past to future; Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Morador, F.F. Cybernetics 3.0. Available at SSRN 4140029 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cibu, B.; Delcea, C.; Domenteanu, A.; Dumitrescu, G. Mapping the evolution of cybernetics: a bibliometric perspective. Computers 2023, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J. Emergence in complex systems. In The Sage Handbook of Complexity and Management; 2011; pp. 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, I.; Vogel, T. Global governance and systemic risk in the 21st century: Lessons from the financial crisis. Global Policy 2010, 1, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L. Planetary Health Requires Tapestry Thinking—Overcoming Silo Mentality. Challenges 2023, 14, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, S.B.; Fort, M.; Patcharanarumol, W.; Tangcharoensathien, V. Primary healthcare in the time of COVID-19: breaking the silos of healthcare provision. BMJ Global Health 2021, 6, e007721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturmberg, J.P.; Tsasis, P.; Hoemeke, L. COVID-19–an opportunity to redesign health policy thinking. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 2022, 11, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Key Messages: World Health Day. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/campaigns/world-health-day/2024/key-messages.

- Merali, Y.; Allen, P. Complexity and systems thinking. The SAGEHandbook of Complexity and Management 2011, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cilliers, F.; Greyvenstein, H. The impact of silo mentality on team identity: An organisational case study. Journal of Industrial Psychology 2012, 38, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, F.; Tagliabue, M.; Lorenzo, F. Organizational silos: A scoping review informed by a behavioral perspective on systems and networks. Societies 2020, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeleel-Ojuade, A. The Role of Information Silos: An analysis of how the categorization of information creates silos within financial institutions, hindering effective communication and collaboration. Available at SSRN 4881342 2024. [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization; Broadway Business, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kunsch, P.L.; Theys, M.; Brans, J.-P. The importance of systems thinking in ethical and sustainable decision-making. Central European Journal of Operations Research 2007, 15, 253–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Klein, G. Conditions for intuitive expertise: A failure to disagree. American Psychologist 2009, 64, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meissner, P.; Narita, Y. AI Will Transform Decision-Making. Here's How. In Emerging Technologies; Forum, W.E., Ed.; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rahwan, I.; et al. Machine behaviour. Nature 2019, 568, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, T.H.; Ronanki, R. Artificial intelligence for the real world. Harvard Business Review 2018, 36, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, O. How AI will change decision-making. 2024. Available online: https://indatalabs.com/blog/artificial-intelligence-decision-making.

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The business of artificial intelligence: What it can – and cannot – do for your organization. Harvard Business Review 2017.

- Agrawal, A.; Gans, J.S.; Goldfarb, A. Prediction machines: The simple economics of artificial intelligence; Harvard Business Review Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mollick, E.; Mollick, E. Co-Intelligence; Random House UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, T.B.; Verplank, W.L.; Brooks, T. Human/computer control of undersea teleoperators. In NASA. American Research Centre: the 14th Annual Conference on Manual Control; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Rhim, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Chen, M.; Lim, A. A deeper look at autonomous vehicle ethics: an integrative ethical decision-making framework to explain moral pluralism. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2021, 8, 632394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothi, R.K.; Thenepalli, T.; Ahn, J.W.; Parhi, P.K.; Chung, K.W.; Lee, J.-Y. Review of rare earth elements recovery from secondary resources for clean energy technologies: Grand opportunities to create wealth from waste. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 267, 122048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, N.; Nelson, C.C.; Ahuja, G.; Sengupta, D. Big data analytics in single-cell transcriptomics: Five grand opportunities. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2021, 11, e1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallo, L.; Rowe, C.; Duh, G. Metaverse vs Descartes: Free Will and Determinism All Over Again. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Crete, Greece, 2024; IEEE Computer Society., Systems and Applications (IISA).

- Bala, B.K.; Arshad, F.M.; Noh, K.M.; Bala, B.K.; Arshad, F.M.; Noh, K.M. Causal loop diagrams. System Dynamics: Modelling and Simulation 2017, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).