Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

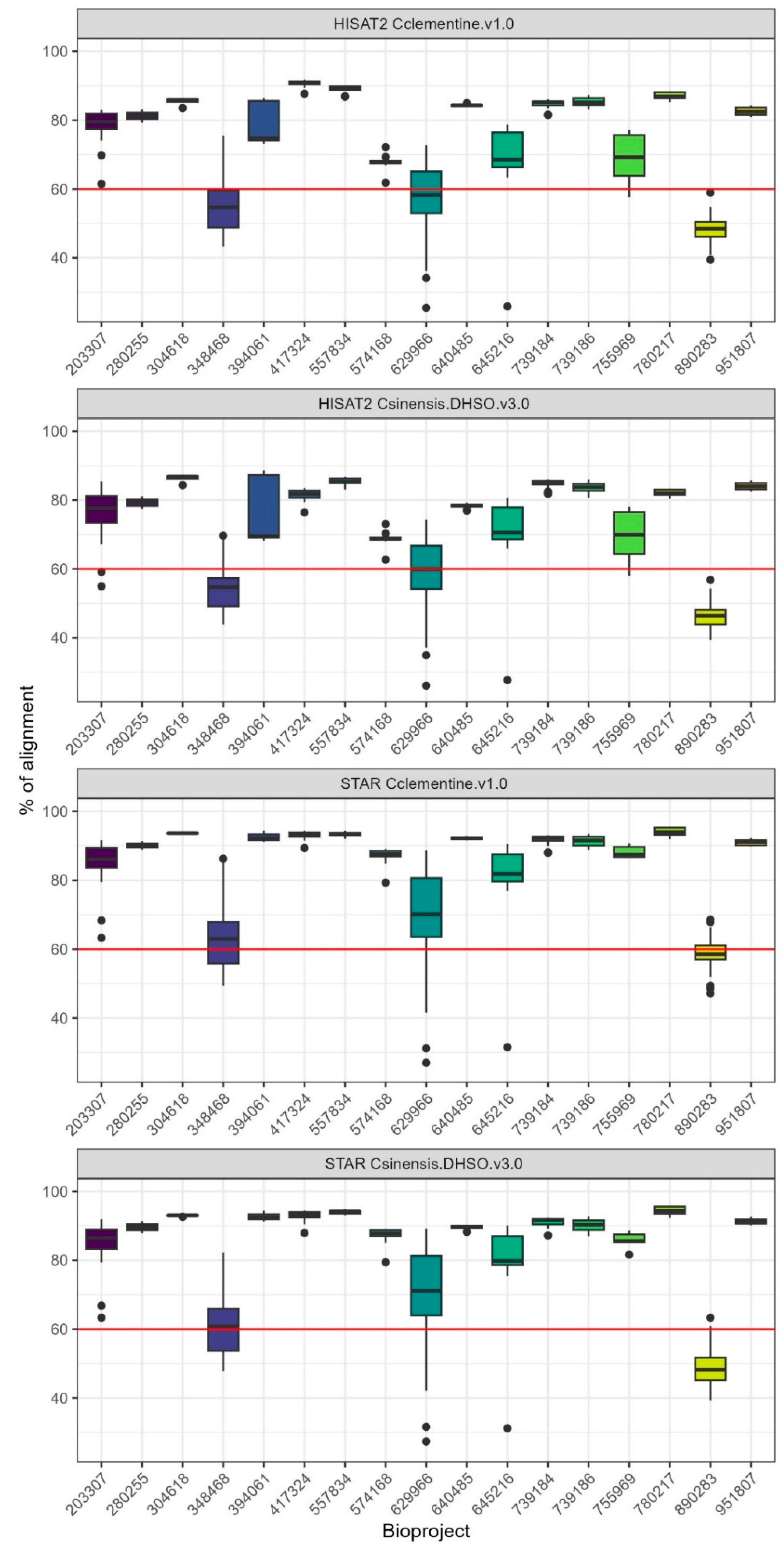

2.1. Evaluation of RNA-Seq Aligners and Selection of Citrus Reference Genome for Optimal Mapping Efficiency.

2.2. Quality Control and Data Retention for Further Analyses

2.3. Gene Expression Profiling and Principal Component Analysis

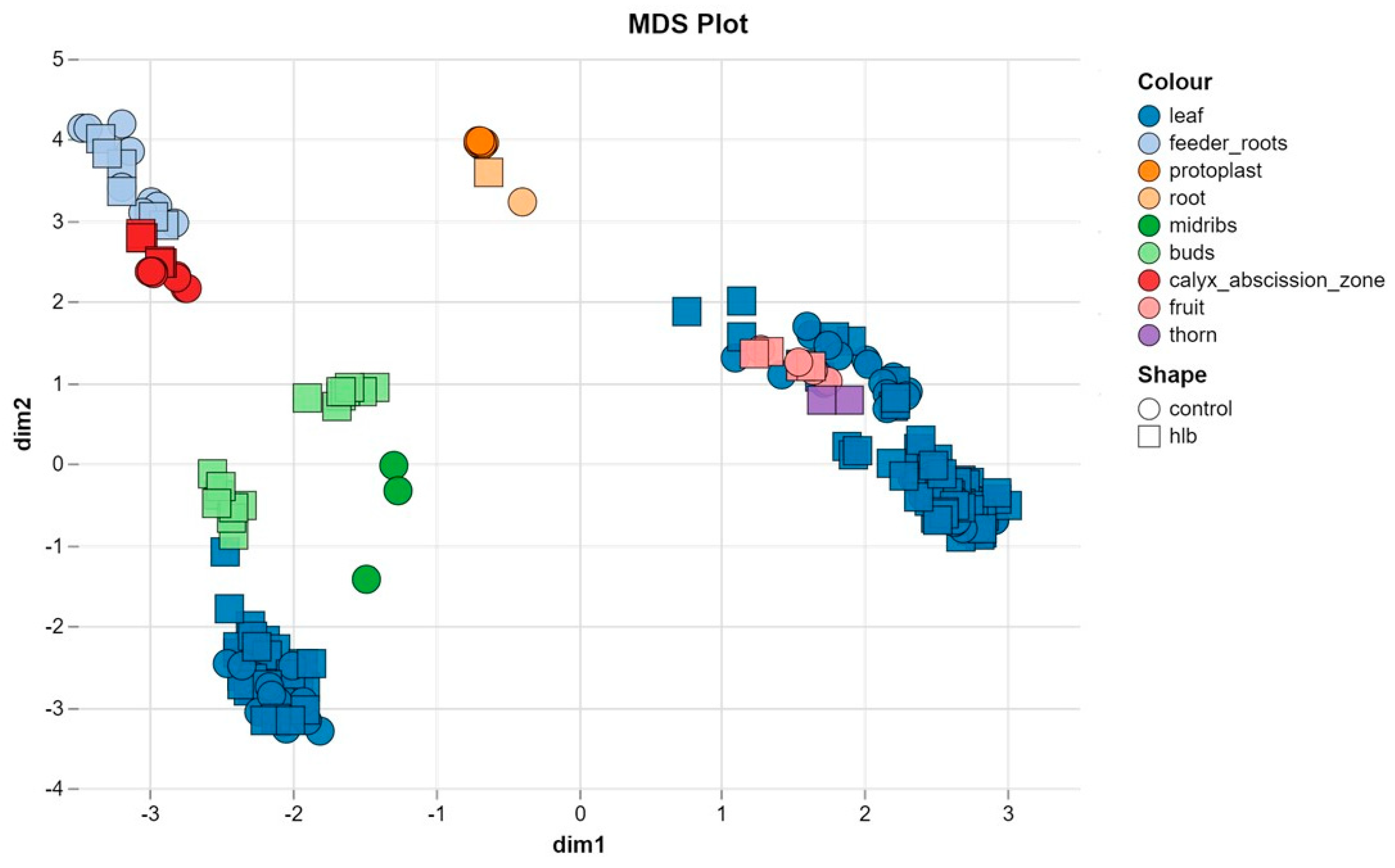

2.4. Clustering of Gene Expression Samples

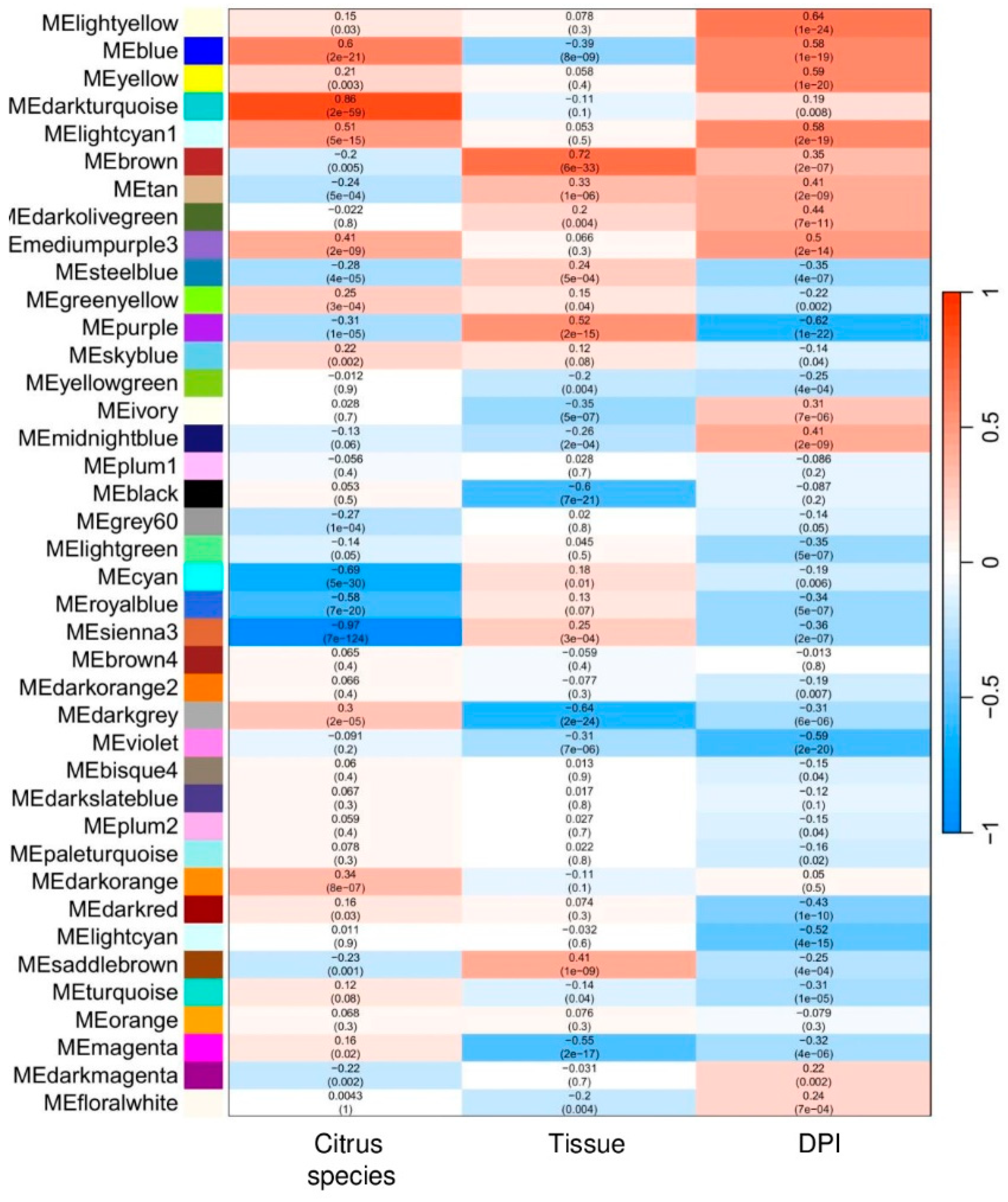

2.5. Weighted Co-Expression Network Construction and Module Trait Analysis

2.6. Gene Significance and Module Membership Results

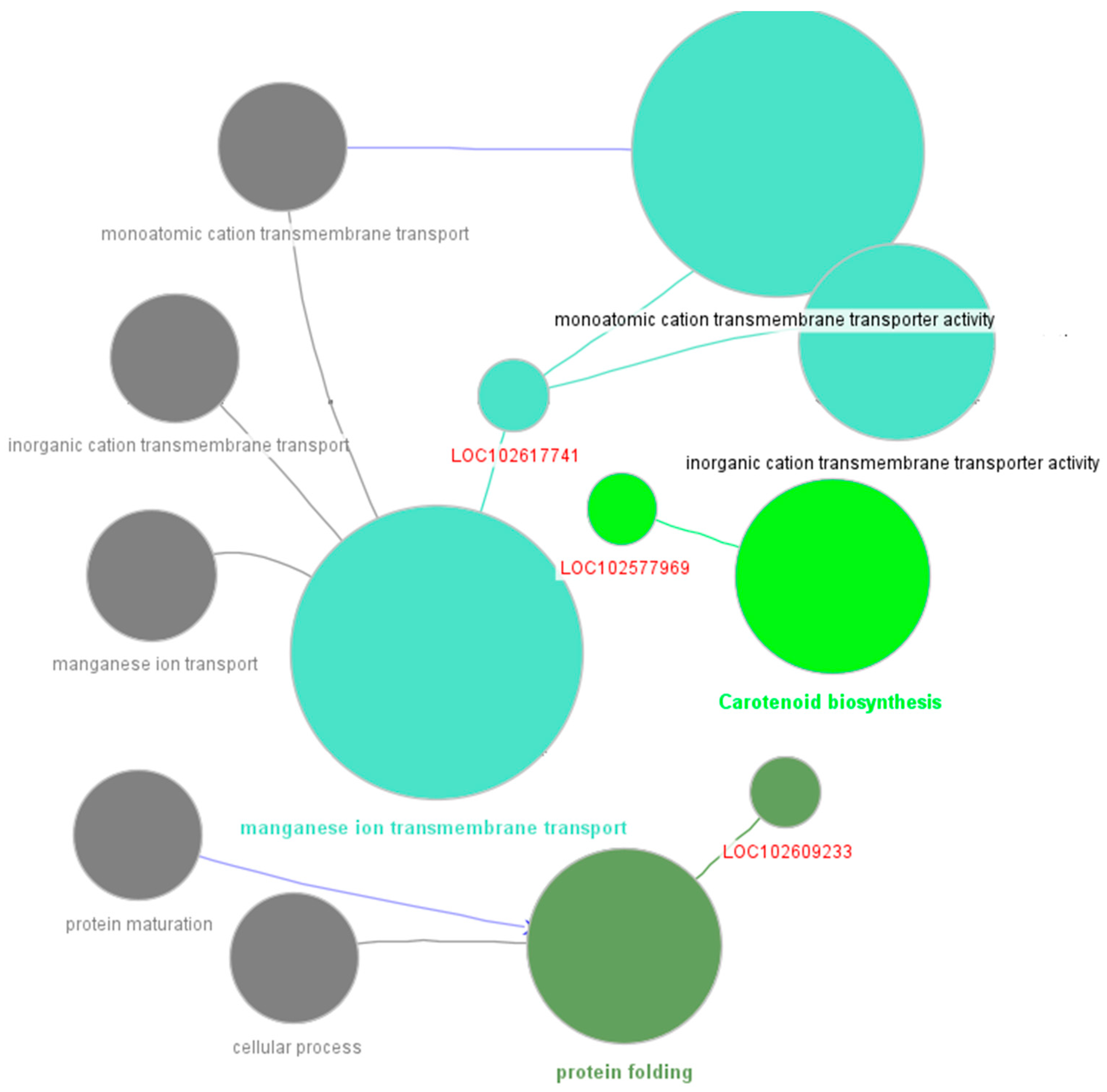

2.7. Differential Gene Expression Analysis Across Selected Citrus Bioprojects

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Acquisition

4.2. Quality Control and Mapping of Data

4.3. Data Normalization and Outlier Detection

4.4. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis

4.5. Gene Significance (GS) and Module Membership (MM) Evaluation

4.6. Functional Annotation and Network Visualization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bové, J.M. Huanglongbing: A Destructive, Newly-Emerging, Century-Old Disease of Citrus. Journal of Plant Pathology 2006, 88, 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gottwald, T.R. Current Epidemiological Understanding of Citrus Huanglongbing *. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol 2010, 48, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Kokane, S.; Savita, B.K.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, A.K.; Ozcan, A.; Kokane, A.; Santra, S. Huanglongbing Pandemic: Current Challenges and Emerging Management Strategies. Plants 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinking, O.A. Diseases of Economic Plants in Southern China. Philippine Agriculturist 1919, 8, 109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Husain, M.A. Dina Nath The Citrus Psylla (Diaphorina Citri, Kuw.) Psyllidae: Homoptera. Memoirs of the Dept. Agri. India Entomol. Series 1927, 10, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Capoor, S.P. Decline of Citrus Trees in India. Bull Natl Inst Sci India 1963, 24, 48–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe, A.J.; Anderssen, F.G. Chromium and Manganese Toxicity. Is It Important in Transvaal Citrus Growing? Farm 1937, 12, 439–440. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, D.; Kokane, S.; Savita, B.K.; Kumar, P.; Sharma, A.K.; Ozcan, A.; Kokane, A.; Santra, S. Huanglongbing Pandemic: Current Challenges and Emerging Management Strategies. Plants 2023, 12, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boa, E. Citrus Huanglongbing (Greening) Disease. Plant Health Cases 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coletta-Filho, H.D.; Targon, M.L.P.N.; Takita, M.A.; De Negri, J.D.; Pompeu, J.; Machado, M.A.; do Amaral, A.M.; Muller, G.W. First Report of the Causal Agent of Huanglongbing (“Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus”) in Brazil. Plant Dis 2004, 88, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbert, S.E. The Discovery of Huanglongbing in Florida. In Proceedings of the International Citrus Canker and Huanglongbing Research Workshop, Orlando, FL, USA, 7–11 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization ‘Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus’. EPPO Datasheets on Pests Recommended for Regulation. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/LIBEAS/distribution (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Usman, H.M.; Saleem, U.; Shafique, T. Decoding Huanglongbing: Understanding the Origins, Impacts, and Remedies for Citrus Greening. Phytopathogenomics and Disease Control 2023, 2, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dala-Paula, B.M.; Plotto, A.; Bai, J.; Manthey, J.A.; Baldwin, E.A.; Ferrarezi, R.S.; Gloria, M.B.A. Effect of Huanglongbing or Greening Disease on Orange Juice Quality, a Review. Front Plant Sci 2019, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, K.C.; Mahmoud, L.M.; Stanton, D.; Welker, S.; Qiu, W.; Grosser, J.W.; Levy, A.; Dutt, M. Insights into the Mechanism of Huanglongbing Tolerance in the Australian Finger Lime (Citrus Australasica). Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Z.; Bredeson, J.V.; Wu, G.A.; Shu, S.; Rawat, N.; Du, D.; Parajuli, S.; Yu, Q.; You, Q.; Rokhsar, D.S.; et al. A Chromosome-Scale Reference Genome of Trifoliate Orange (Poncirus Trifoliata) Provides Insights into Disease Resistance, Cold Tolerance and Genome Evolution in Citrus. Plant Journal 2020, 104, 1215–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killiny, N.; Jones, S.E.; Nehela, Y.; Hijaz, F.; Dutt, M.; Gmitter, F.G.; Grosser, J.W. All Roads Lead to Rome: Towards Understanding Different Avenues of Tolerance to Huanglongbing in Citrus Cultivars. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 129, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Hu, Y.; Fu, S.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X. Coordination of Multiple Regulation Pathways Contributes to the Tolerance of a Wild Citrus Species (Citrus Ichangensis ‘2586’) against Huanglongbing. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 2020, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folimonova, S.Y.; Robertson, C.J.; Garnsey, S.M.; Gowda, S.; Dawson, W.O. Examination of the Responses of Different Genotypes of Citrus to Huanglongbing (Citrus Greening) under Different Conditions. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Bai, X.; Wen, Q.; Xie, Z.; Wu, L.; Peng, A.; He, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, S. Comparative Analysis of Tolerant and Susceptible Citrus Reveals the Role of Methyl Salicylate Signaling in the Response to Huanglongbing. J Plant Growth Regul 2019, 38, 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Liu, X.; Lou, B.; Zhou, C.; Wang, X. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Unveils the Tolerance Mechanisms of Citrus Hystrix in Response to “Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus” Infection. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yu, X.; Stover, E.; Luo, F.; Duan, Y. Transcriptome Profiling of Huanglongbing (HLB) Tolerant and Susceptible Citrus Plants Reveals the Role of Basal Resistance in HLB Tolerance. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadugu, C.; Keremane, M.L.; Halbert, S.E.; Duan, Y.P.; Roose, M.L.; Stover, E.; Lee, R.F. Long-Term Field Evaluation Reveals Huanglongbing Resistance in Citrus Relatives. Plant Dis 2016, 100, 1858–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, G.P.; Stover, E.; Ramadugu, C.; Keremane, M.L.; Lee, R.F. Apparent Tolerance to Huanglongbing in Citrus and Citrus-Related Germplasm. HortScience 2017, 52, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.N.; Lopes, S.A.; Raiol-Junior, L.L.; Wulff, N.A.; Girardi, E.A.; Ollitrault, P.; Peña, L. Resistance to ‘Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus,’ the Huanglongbing Associated Bacterium, in Sexually and/or Graft-Compatible Citrus Relatives. Front Plant Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.Y.; Niu, D.D.; Kund, G.; Jones, M.; Albrecht, U.; Nguyen, L.; Bui, C.; Ramadugu, C.; Bowman, K.D.; Trumble, J.; et al. Identification of Citrus Immune Regulators Involved in Defence against Huanglongbing Using a New Functional Screening System. Plant Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivager, G.; Calvez, L.; Bruyere, S.; Boisne-Noc, R.; Brat, P.; Gros, O.; Ollitrault, P.; Morillon, R. Specific Physiological and Anatomical Traits Associated With Polyploidy and Better Detoxification Processes Contribute to Improved Huanglongbing Tolerance of the Persian Lime Compared With the Mexican Lime. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.P.; De Francesco, A.; Trinh, J.; Gurung, F.B.; Pang, Z.; Vidalakis, G.; Wang, N.; Ancona, V.; Ma, W.; Coaker, G. Genome-Wide Analyses of Liberibacter Species Provides Insights into Evolution, Phylogenetic Relationships, and Virulence Factors. Mol Plant Pathol 2020, 21, 716–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batarseh, T.N.; Batarseh, S.N.; Morales-Cruz, A.; Gaut, B.S. Comparative Genomics of the Liberibacter Genus Reveals Widespread Diversity in Genomic Content and Positive Selection History. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Pierson, E.A.; Setubal, J.C.; Xu, J.; Levy, J.G.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Rangel, L.T.; Martins, J. The Candidatus Liberibacter-Host Interface: Insights into Pathogenesis Mechanisms and Disease Control. Annu Rev Phytopathol 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.F.; Kong, W.Z.; Mukangango, M.; Hu, Y.W.; Liu, Y.T.; Sang, W.; Qiu, B.L. Distribution and Dynamic Changes of Huanglongbing Pathogen in Its Insect Vector Diaphorina Citri. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endarto, O.; Wicaksono, R.C.; Wuryantini, S.; Tarno, H.; Nurindah. Climate Change Mitigation and Seasonal Infestation Patterns of Citrus Psyllid Diaphorina Citri: Implications for Managing Huanglongbing (HLB) Disease in Tangerine Citrus. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2024, 1346, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, E.A.; Cubero, J.; Roper, C.; Brown, J.K.; Bock, C.H.; Wang, N. ‘Candidatus Liberibacter’ Pathosystems at the Forefront of Agricultural and Biological Research Challenges. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Guo, X.; Su, J.; Zhang, Q.; Lian, M.; Xue, H.; Li, Q.; He, Y.; Zou, X.; Song, Z.; et al. ABA-CsABI5-CsCalS11 Module Upregulates Callose Deposition of Citrus Infected with Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus. Hortic Res 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Huynh, L.; Zhang, S.; Rabara, R.; Nguyen, H.; Velásquez Guzmán, J.; Hao, G.; Miles, G.; Shi, Q.; Stover, E.; et al. Two Liberibacter Proteins Combine to Suppress Critical Innate Immune Defenses in Citrus. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.S.; Xu, J.; Achor, D.S.; Li, J.; Wang, N. Microscopic and Transcriptomic Analyses of Early Events Triggered by ‘Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus’ in Young Flushes of Huanglongbing-Positive Citrus Trees. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardini, C.; Turner, D.; Wang, C.; Welker, S.; Achor, D.; Artiga, Y.A.; Turgeon, R.; Levy, A. Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus Reduces Callose and reactive Oxygen Species Production in the Phloem. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Gong, Y.; Shi, H.; Ma, X.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, D.; Fu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yang, N.; et al. ‘Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus’ Secretory Protein SDE3 Inhibits Host Autophagy to Promote Huanglongbing Disease in Citrus. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2558–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, L.; Fox, E.G.P.; Deng, X.; Xu, M.; Zheng, Z.; Li, X.; Fu, J.; Zhu, H.; Huang, J.; et al. Physiological Variables Influenced by ‘Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus’ Infection in Two Citrus Species. Plant Dis 2023, 107, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Chen, C.; Yu, Q.; Khalaf, A.; Achor, D.S.; Brlansky, R.H.; Moore, G.A.; Li, Z.G.; Gmitter, F.G. Comparative Transcriptional and Anatomical Analyses of Tolerant Rough Lemon and Susceptible Sweet Orange in Response to “Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus” Infection. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2012, 25, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Chen, C.; Du, D.; Huang, M.; Yao, J.; Yu, F.; Brlansky, R.H.; Gmitter, F.G. Reprogramming of a Defense Signaling Pathway in Rough Lemon and Sweet Orange Is a Critical Element of the Early Response to Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus. Hortic Res 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.; Xu, J.; Hendrich, C.; Pandey, S.S.; Yu, Q.; Jr, F.G.G.; Wang, N. Seasonal Transcriptome Profiling of Susceptible and Tolerant Citrus Cultivars to Citrus Huanglongbing. Phytopathology 2023, 113, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, X.; Yu, Q.; Russo, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Wang, Y.Z.; Holden, P.M.; Gmitter, F.G. Role of Long Non-Coding RNA in Regulatory Network Response to Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus in Citrus. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.C.; Mahmoud, L.M.; Stanton, D.; Welker, S.; Qiu, W.; Grosser, J.W.; Levy, A.; Dutt, M. Insights into the Mechanism of Huanglongbing Tolerance in the Australian Finger Lime (Citrus Australasica). Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, X.; Mira, A.; Yu, Q.; Gmitter, F.G. The Mechanism of Citrus Host Defense Response Repression at Early Stages of Infection by Feeding of Diaphorina Citri Transmitting Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfelder, P.; Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R Package for Weighted Correlation Network Analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2008, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Chen, D.; Liu, K.; Chen, W.; He, F.; Tong, Z.; Luo, Q. Co-Expression Network Analysis and Identification of Core Genes in the Interaction between Wheat and Puccinia Striiformis f. Sp. Tritici. Arch Microbiol 2024, 206, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.; Wang, P.; Fang, H.; Zheng, J.; Zhong, C.; Yang, Y.; Yu, W. Weighted Gene Co-Expression Analysis Network-Based Analysis on the Candidate Pathways and Hub Genes in Eggplant Bacterial Wilt-Resistance: A Plant Research Study. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Wei, H.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Qi, Y.; Wu, Z.; Huang, F.; Yu, L. Weighted Gene Coexpression Network Analysis of Candidate Pathways and Genes in Soft Rot Resistance of Amorphophallus. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2022, 147, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Huang, G. Analysis of Huanglongbing-Associated RNA-Seq Data Reveals Disturbances in Biological Processes within Citrus Spp. Triggered by Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus Infection. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobin, A.; Davis, C.A.; Schlesinger, F.; Drenkow, J.; Zaleski, C.; Jha, S.; Batut, P.; Chaisson, M.; Gingeras, T.R. STAR: Ultrafast Universal RNA-Seq Aligner. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.; Di Marco, A.; Pellegrini, C. Comparing HISAT and STAR-Based Pipelines for RNA-Seq Data Analysis: A Real Experience. In Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023; Vol. 2023, pp. 218–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.B.B.; Fei, Z.; Giovannoni, J.J.; Rose, J.K.C. Catalyzing Plant Science Research with RNA-Seq. Front Plant Sci 2013, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, F.; Uratsu, S.L.; Albrecht, U.; Reagan, R.L.; Phu, M.L.; Britton, M.; Buffalo, V.; Fass, J.; Leicht, E.; Zhao, W.; et al. Transcriptome Profiling of Citrus Fruit Response to Huanglongbing Disease. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dam, S.; Võsa, U.; van der Graaf, A.; Franke, L.; de Magalhães, J.P. Gene Co-Expression Analysis for Functional Classification and Gene-Disease Predictions. Brief Bioinform 2018, 19, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, B.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Dandekar, A.M.; Caruso, T.; Martinelli, F. Identifying Host Molecular Features Strongly Linked With Responses to Huanglongbing Disease in Citrus Leaves. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Pang, Z.; Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Pandey, S.S.; Li, J.; Achor, D.S.; Vasconcelos, F.N.C.; Hendrich, C.; Huang, Y.; et al. Citrus Huanglongbing Is a Pathogen-Triggered Immune Disease That Can Be Mitigated with Antioxidants and Gibberellin. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijaz, F.; Manthey, J.A.; Van der Merwe, D.; Killiny, N. Nucleotides, Micro- and Macro-Nutrients, Limonoids, Flavonoids, and Hydroxycinnamates Composition in the Phloem Sap of Sweet Orange. Plant Signal Behav 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicine National Academies of Sciences, Engineering; Division on Earth and Life Studies. A Review of the Citrus Greening Research and Development Efforts Supported by the Citrus Research and Development Foundation: Fighting a Ravaging Disease; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, 2018; ISBN 9780309472142. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, U.; Fiehn, O.; Bowman, K.D. Metabolic Variations in Different Citrus Rootstock Cultivars Associated with Different Responses to Huanglongbing. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 107, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killiny, N.; Nehela, Y. Metabolomic Response to Huanglongbing: Role of Carboxylic Compounds in Citrus Sinensis Response to “candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus” and Its Vector, Diaphorina Citri. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 2017, 30, 666–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinelli, F.; Dandekar, A.M. Genetic Mechanisms of the Devious Intruder Candidatus Liberibacter in Citrus. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijaz, F.; Manthey, J.; Folimonova, S.Y.; Davis, C.L.; Jones, S.E.; Reyes-De-Corcuera, J.I. An HPLC-MS Characterization of the Changes in Sweet Leaf Metabolite Profile Following Infection by the Bacterial Pathogen Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus. PLoS One 2013, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yu, X.; Stover, E.; Luo, F.; Duan, Y. Transcriptome Profiling of Huanglongbing (HLB) Tolerant and Susceptible Citrus Plants Reveals the Role of Basal Resistance in HLB Tolerance. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, B.; Yu, Q.; Deng, Z.; Duan, Y.; Luo, F.; Gmitter, F. A Chromosome-Level Phased Genome Enabling Allele-Level Studies in Sweet Orange: A Case Study on Citrus Huanglongbing Tolerance. Hortic Res 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimò, G.; Lo Bianco, R.; Gonzalez, P.; Bandaranayake, W.; Etxeberria, E.; Syvertsen, J.P. Carbohydrate and Nutritional Responses to Stem Girdling and Drought Stress with Respect to Understanding Symptoms of Huanglongbing in Citrus. HortScience 2013, 48, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achor, D.S.; Etxeberria, E.; Wang, N.; Folimonova, S.Y.; Chung, K.R.; Albrigo, L.G. Sequence of Anatomical Symptom Observations in Citrus Affected with Huanglongbing Disease. Plant Pathol J (Faisalabad) 2010, 9, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yu, Q.; Deng, Z.; Duan, Y.; Luo, F.; Gmitter, F. A Chromosome-Level Phased Genome Enabling Allele-Level Studies in Sweet Orange: A Case Study on Citrus Huanglongbing Tolerance. Hortic Res 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.; Munoz-Bodnar, A.; Gabriel, D.W. ‘Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus’ Peroxiredoxin (LasBCP) Suppresses Oxylipin-Mediated Defense Signaling in Citrus. J Plant Physiol 2019, 236, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giossi, C.; Cartaxana, P.; Cruz, S. Photoprotective Role of Neoxanthin in Plants and Algae. Molecules 2020, 25, 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.S.; Peng, T.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.H. Genome-Wide Identification and Comparative Expression Profiling of the WRKY Transcription Factor Family in Two Citrus Species with Different Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus Susceptibility. BMC Plant Biol 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtolo, M.; de Souza Pacheco, I.; Boava, L.P.; Takita, M.A.; Granato, L.M.; Galdeano, D.M.; de Souza, A.A.; Cristofani-Yaly, M.; Machado, M.A. Wide-Ranging Transcriptomic Analysis of Poncirus Trifoliata, Citrus Sunki, Citrus Sinensis and Contrasting Hybrids Reveals HLB Tolerance Mechanisms. Sci Rep 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, M.; Zeier, J. L-Lysine Metabolism to N-Hydroxypipecolic Acid: An Integral Immune-Activating Pathway in Plants. Plant Journal 2018, 96, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeier, J. New Insights into the Regulation of Plant Immunity by Amino Acid Metabolic Pathways. Plant Cell Environ 2013, 36, 2085–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershko, A.; Ciechanover, A. The Ubiquitin System. Annu Rev Biochem 1998, 67, 425–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killiny, N.; Hijaz, F. Amino Acids Implicated in Plant Defense Are Higher in Candidatus Liberibacter Asiaticus-Tolerant Citrus Varieties. Plant Signal Behav 2016, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwugo, C.C.; Doud, M.S.; Duan, Y.; Lin, H. Proteomics Analysis Reveals Novel Host Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Thermotherapy of ’Ca. Liberibacter Asiaticus’-Infected Citrus Plants. BMC Plant Biol 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibáñez, A.M.; Martinelli, F.; Reagan, R.L.; Uratsu, S.L.; Vo, A.; Tinoco, M.A.; Phu, M.L.; Chen, Y.; Rocke, D.M.; Dandekar, A.M. Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis of Citrus Fruit to Elucidate Puffing Disorder. Plant Science 2014, 217–218, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.A.; Prochnik, S.; Jenkins, J.; Salse, J.; Hellsten, U.; Murat, F.; Perrier, X.; Ruiz, M.; Scalabrin, S.; Terol, J.; et al. Sequencing of Diverse Mandarin, Pummelo and Orange Genomes Reveals Complex History of Admixture during Citrus Domestication. Nat Biotechnol 2014, 32, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. HISAT: A Fast Spliced Aligner with Low Memory Requirements. Nat Methods 2015, 12, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. FeatureCounts: An Efficient General Purpose Program for Assigning Sequence Reads to Genomic Features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Gorodkin, J.; Jensen, L.J. Cytoscape StringApp: Network Analysis and Visualization of Proteomics Data. J Proteome Res 2019, 18, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindea, G.; Mlecnik, B.; Hackl, H.; Charoentong, P.; Tosolini, M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Fridman, W.H.; Pagès, F.; Trajanoski, Z.; Galon, J. ClueGO: A Cytoscape Plug-in to Decipher Functionally Grouped Gene Ontology and Pathway Annotation Networks. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aligner | Genome | Minimum (%) | Q1 (%) | Median (%) | Q3 (%) | Maximum (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | C. sinensis DHSO v3.0 | 23.02 | 63.53 | 88.88 | 92.1 | 95.71 |

| STAR | C. clementina v1.0 | 27 | 66.23 | 89.75 | 92.41 | 95.44 |

| HISAT2 | C. sinensis DHSO v3.0 | 19.17 | 56.05 | 78.06 | 83.3 | 88.6 |

| HISAT2 | C. clementina v1.0 | 14.73 | 55.63 | 80.87 | 85.52 | 91.81 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).