Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

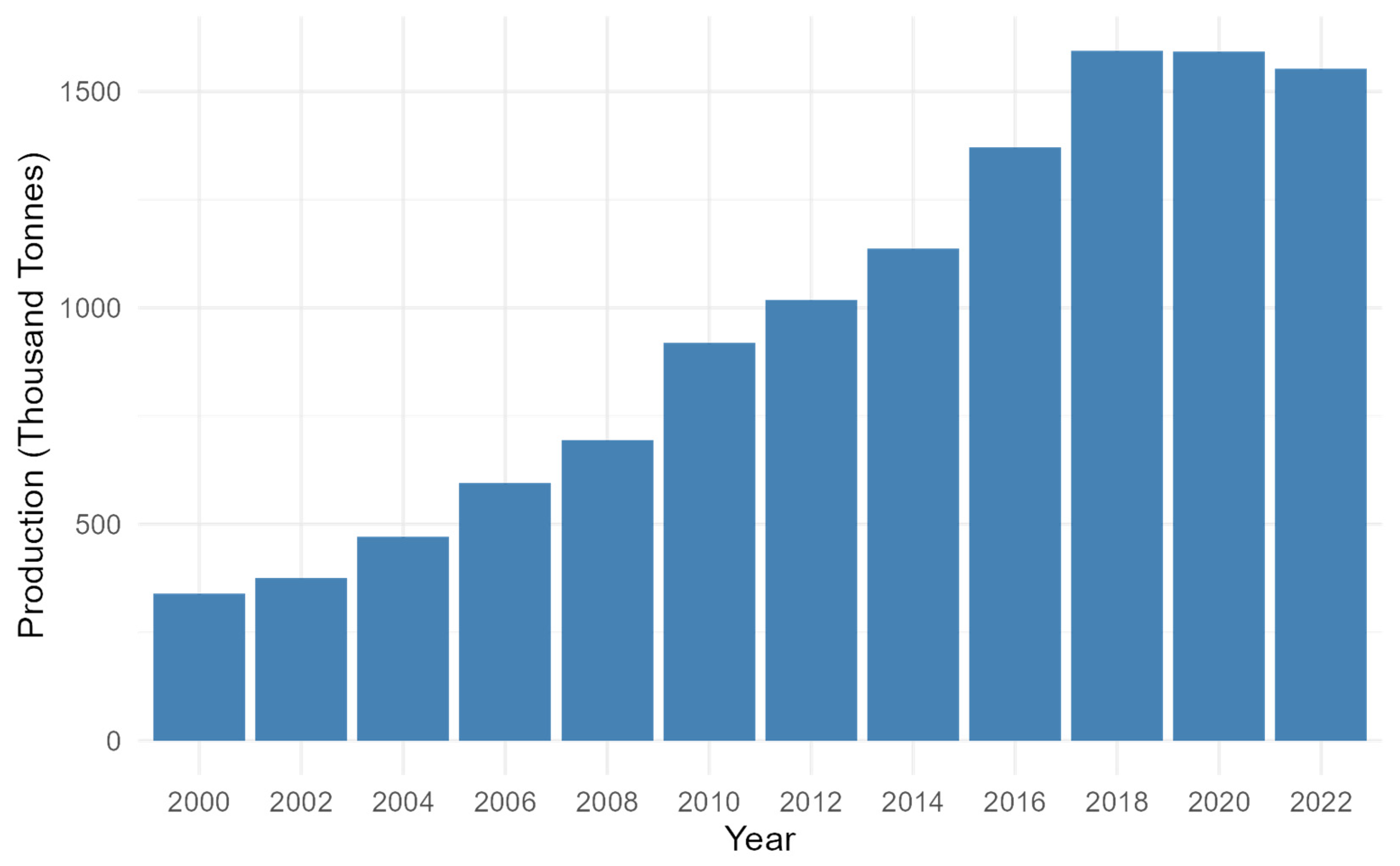

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

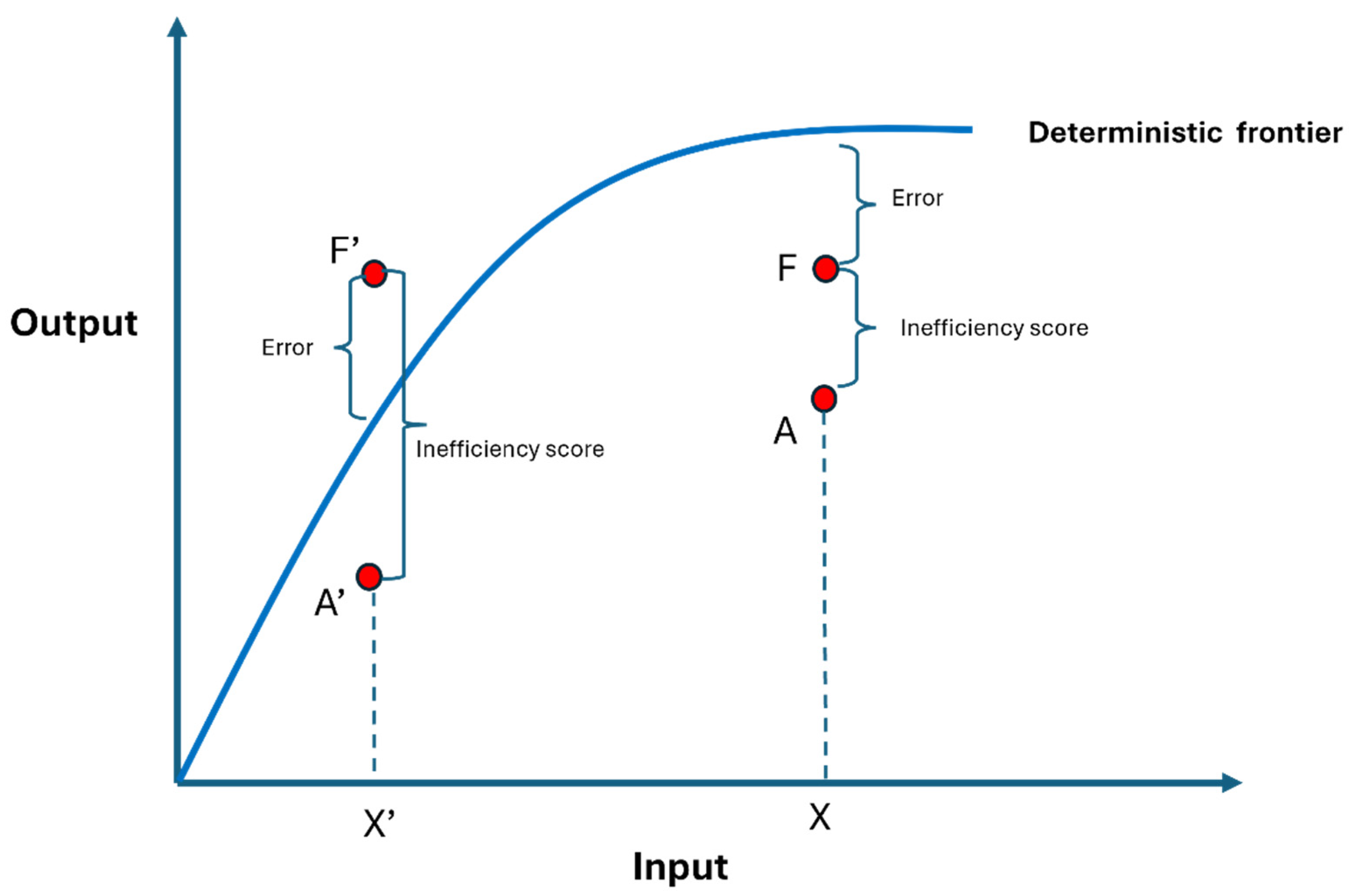

2.1. Efficiency Estimation

2.2. Inefficiency Effects Estimation

2.3. Stochastic Frontier Model

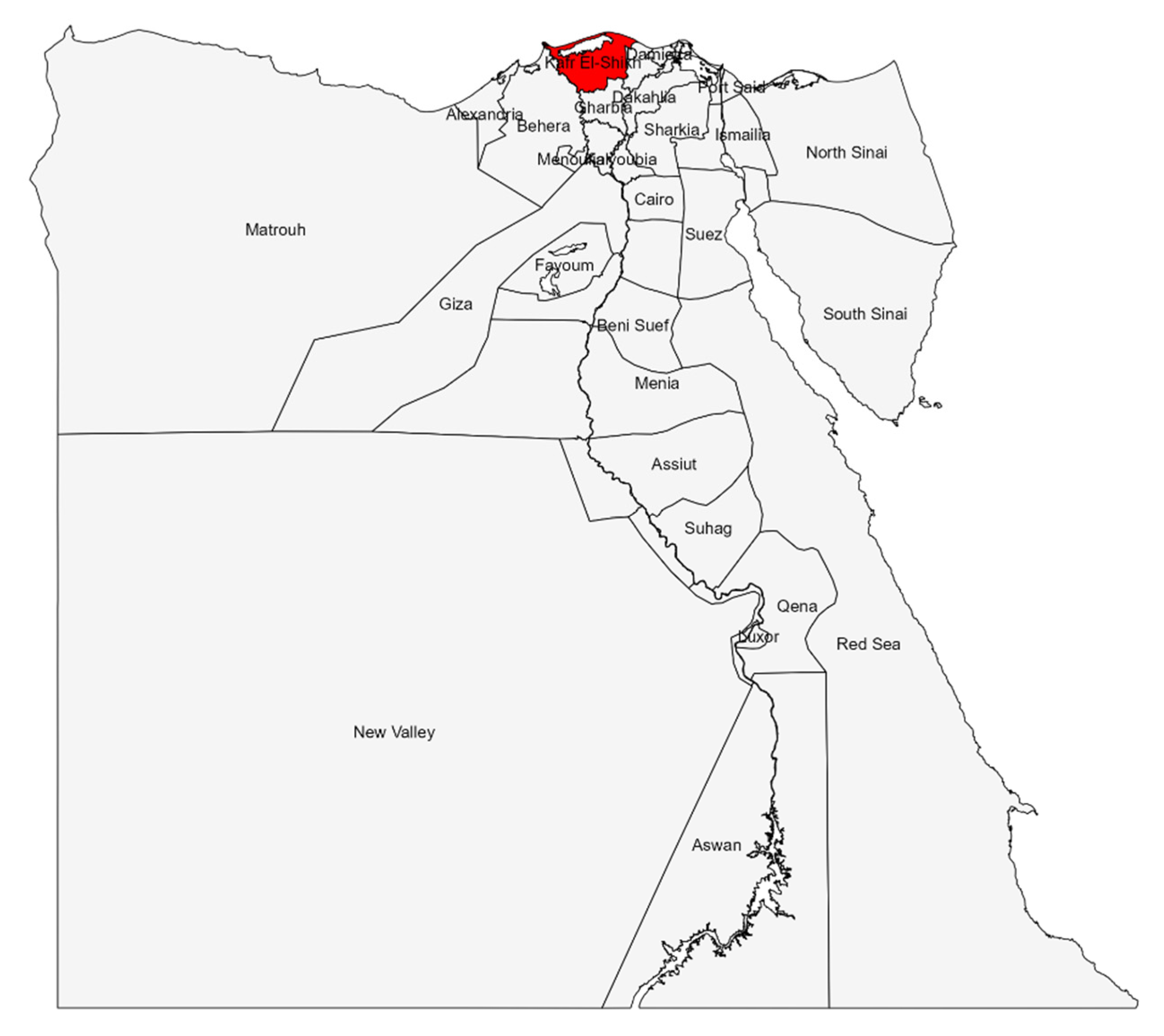

2.4. Data

3. Results

3.1. Hypothesis Testing

3.1. Efficiency estimation

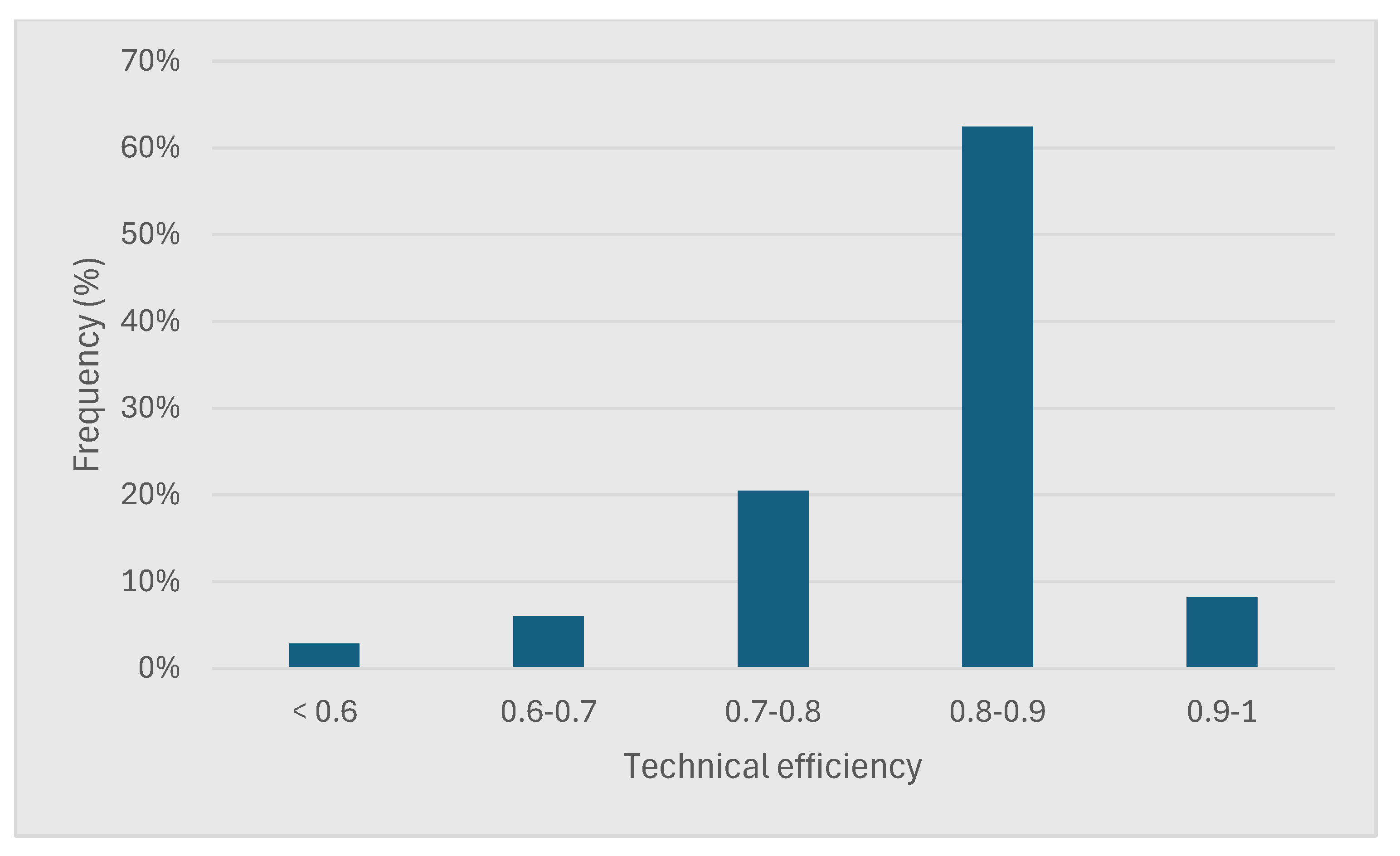

| Technical efficiency range | Number of farms | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| <0.60 | 9 | 3% |

| 0.60-0.70 | 19 | 6% |

| 0.70-0.80 | 65 | 21% |

| 0.80-0.90 | 198 | 62% |

| 0.90-1.00 | 26 | 8% |

3.3. Inefficiency Effects Model

| Efficiency drivers | Coefficient | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Farmer’s age (z1) | -0.02 | 0.02 |

| Number of species cultured (z2) | 0.55** | 0.26 |

| Education level (z3) | 0.17 | 0.13 |

| Farm age (z4) | 0.04* | 0.02 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficiency Estimation

4.2. Inefficiency Effects Model

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- El-Sayed, A. The Success Story of Aquaculture in Egypt: The Real Motivation for Hosting the First Aquaculture Africa Conference (AFRAQ21) Available online:. Available online: https://www.was.org/articles/The-Success-Story-of-Aquaculture-in-Egypt-The-Real-Motivation-for-Hosting-the-First-Aquaculture-Africa-Conference.aspx (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- GAFRD Fish Statistics Yearbooks. Retrieved from Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation, Cairo, Egypt. 2020.

- GAFRD Fish Statistics Yearbooks. Retrieved from Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation, Cairo, Egypt. 2019.

- Mehrim, A.I.; Refaey, M.M. An Overview of the Implication of Climate Change on Fish Farming in Egypt. Sustain. 2023, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA), FAO: Rome, 2022; 2022; ISBN 9789251363645.

- Wally, A. The State and Development of Aquaculture in Egypt. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shaalan, M.; El-Mahdy, M.; Saleh, M.; El-Matbouli, M. Aquaculture in Egypt: Insights on the Current Trends and Future Perspectives for Sustainable Development. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2018, 26, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.F.M.; Nasr-Allah, A.M.; Dickson, M.; Gilmour, C. Analysis of Aquafeed Sector Competitiveness in Egypt. Aquaculture 2022, 547, 737486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, O.; Bio Singou Sabi, A.F. Overview of Aquaculture Systems in Egypt and Nigeria, Prospects, Potentials, and Constraints. Aquac. Fish. 2021, 6, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignoli, C.M.; Manyise, T.; Shikuku, K.M.; Nasr-Allah, A.M.; Dompreh, E.B.; Henriksson, P.J.G.; Lam, R.D.; Lozano Lazo, D.; Tran, N.; Roem, A.; et al. Tilapia Aquaculture Systems in Egypt: Characteristics, Sustainability Outcomes and Entry Points for Sustainable Aquatic Food Systems. Aquaculture 2023, 577, 739952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2024 Global Aquaculture Production. In: Fisheries and Aquaculture Available online: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/collection/aquaculture?lang=en.

- Iliyasu, A.; Mohamed, Z.A.; Terano, R. Comparative Analysis of Technical Efficiency for Different Production Culture Systems and Species of Freshwater Aquaculture in Peninsular Malaysia. Aquac. Reports 2016, 3, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Khan, A.; Huq, A.S.M.A. Technical Efficiency in Tilapia Farming of Bangladesh : A Stochastic Frontier Production Approach. 2012; 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Mitra, S.; Khan, M.A. Technical and Cost Efficiency of Pond Fish Farms: Do Young Educated Farmers Bring Changes? J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 12, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.; Khan, M.A.; Nielsen, R.; Islam, N. Total Factor Productivity and Technical Efficiency Differences of Aquaculture Farmers in Bangladesh: Do Environmental Characteristics Matter? J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gong, Y.; Yuan, Y. Technical Efficiency of Different Farm Sizes for Tilapia Farming in China. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Dey, M.M.; Paraguas, F.J.; Bimbao, G.B.; Regaspi, P.B. Technical Efficiency of Tilapia Growout Pond Operations in the Philippines. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2000, 4, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phiri, F.; Yuan, X. Technical Efficiency of Tilapia Production in Malawi And China: Application of Stochastic Frontier Production Approach. J. Aquac. Res. Dev. 2018, 09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zongli, Z.; Yanan, Z.; Feifan, L.; Hui, Y.; Yongming, Y.; Xinhua, Y. Economic Efficiency of Small-Scale Tilapia Farms in Guangxi, China. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2017, 21, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussa, H.; Kaunda, E.; Jere, W.W.L.; Ng’ong’ola, D.H. Resource Use Efficiency in Tilapia Production in Central and Southern Malawi. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2020, 24, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, Y.M.; Khor, L.Y.; Tran, N.; Shikuku, K.M.; Zeller, M. Technical Efficiency of Small-Scale Aquaculture in Myanmar: Does Women’s Participation in Decision-Making Matter? Aquac. Reports 2021, 21, 100841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.L.; Garcia, Y.T.; Dator, M.-A.L.; Tan, I.M.A.; Pemsl, D.E. Technical Efficiency of Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (Gift) Cage Culture Operations in the Lakes of Laguna and Batangas, Philippines. J. Issaas 2011, 17, 194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Onumah, E.E.; Brümmer, B.; Hörstgen-Schwark, G. Elements Which Delimitate Technical Efficiency of Fish Farms in Ghana. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2010, 41, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The Measurement of Productive Efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1957, 120, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the Efficiency of Decision Making Units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, G.R.; Oukil, A. Flexible Target Setting in Mergers Using Inverse Data Envelopment Analysis. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 35, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, D.; Lovell, C.A.K.; Schmidt, P. Formulation and Estimation of Stochastic Frontier Production Function Models. J. Econom. 1977, 6, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeusen, W.; van Den Broeck, J. Efficiency Estimation from Cobb-Douglas Production Functions with Composed Error. Int. Econ. Rev. (Philadelphia). 1977, 18, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, M.M.; Paraguas, F.J.; Srichantuk, N.; Yuan, X.; Bhatta, R.; Dung, L.T.C. Technical Efficiency of Freshwater Pond Polyculture Production in Selected Asian Countries: Estimation and Implication. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2005, 9, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelli, T.J.; Rao, D.S.P.; O’donnell, C.J.; Battese, G.E. An Introduction to Efficiency and Productivity Analysis; springer science & business media, 2005; ISBN 0387258957.

- Battese, G.E.; Coelli, T.J. A Model for Technical Inefficiency Effects in a Stochastic Frontier Production Function for Panel Data. Empir. Econ. 1995, 20, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakpo, K.H.; Desjeux, Y.; Henningsen, A.; Latruffe, L. SfaR: Stochastic Frontier Analysis Routines. 2023.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2021.

- Shikuku, K.M.; Van Tran, N.; Henriksson, P.; Nasr-Allah, A.; Roem, A.; Badr, A.; Cheong, K.C.; Sbaay, A.; Calmet, M.; Charo-Karisa, H.; et al. Dataset for Baseline Integrated Assessment of Aquaculture Systems Performance in Egypt 2021.

- Shikuku, K.M.; Tran, N.; Henriksson, P.; Nasr-, A.M.; Roem, A.; Badr, A.; Cheong, K.C.; Sbaay, A.S.; Angela, M.; Karisa, H.; et al. A Baseline Integrated Assessment of Aquaculture Systems Performance in Egypt. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Asche, F.; Roll, K.H. Determinants of Inefficiency in Norwegian Salmon Aquaculture. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2013, 17, 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, A. Technical Efficiency Analysis for the Iranian Fishery in the Persian Gulf. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2006, 63, 1759–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, F.-S.; Sun, C.-H.; Yu, J.-M. Technical Efficiency Analysis of Milkfish (Chanos Chanos) Production in Taiwan—an Application of the Stochastic Frontier Production Function. Aquaculture 2004, 230, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Dey, M.M.; Rabbani, A.G.; Sudhakaran, P.O.; Thapa, G. Technical Efficiency of Freshwater Aquaculture and Its Determinants in Tripura, India. 2009.

- Mitra, S.; Khan, M.A.; Nielsen, R. Credit Constraints and Aquaculture Productivity. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2019, 23, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.E.; Khan, M.A.; Dey, M.M.; Alam, M.S. Insights of Freshwater Carp Polyculture in Bangladesh: Inefficiency, Yield Gap, and Yield Loss Perspectives. Aquaculture 2022, 557, 738341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeagocha, S.U.O..; Henri-Ukoha, A..; Chikezie, C..; G.S.; , A.; Oladejo, E.E..; Uhuegbulam, I.J. and; Oshaji, I.O. Economics of Catfish ( Clarias Gariepinus ) and Tilapia ( Tilapia Zilli ) under Monoculture and Polyculture Production in Aguata Local Government Area of Anambra State, Nigeria : A Comparative Approach. 2015, 3, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrim, A.; Refaey, M.; Khalil, F.; Shaban, Z. Impact of Mono- and Polyculture Systems on Growth Performance, Feed Utilization, and Economic Efficiency of Oreochromis Niloticus, Mugil Cephalus, and Mugil Capito. J. Anim. Poult. Prod. 2018, 9, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sagheer, F.; El-Ebiary, E.; Mabrouk, H. Comparison Between Monoculture and Polyculture of Tilapia and Mullet Reared in Floating Net Cages. J. Anim. Poult. Prod. 2008, 33, 4863–4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopin, T.; Buschmann, A.H.; Halling, C.; Troell, M.; Kautsky, N.; Neori, A.; Kraemer, G.P.; Zertuche-González, J.A.; Yarish, C.; Neefus, C. Integrating Seaweeds into Marine Aquaculture Systems: A Key toward Sustainability. J. Phycol. 2001, 37, 975–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais, A.P.M.; Santos, I.L.; Carneiro, R.F.S.; Routledge, E.A.B.; Hayashi, L.; de Lorenzo, M.A.; do Nascimento Vieira, F. Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture System Applied to Shrimp, Tilapia, and Seaweed (Ulva Ohnoi) Using Biofloc Technology. Aquaculture 2023, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S. V.; Sukhdhane, K.S.; Krishnani, K.K.; Rani, B.; Pathak, M.S.; Chanu, T.I.; Munilkumar, S. Inclusion of Organic and Inorganic Extractive Species Improves Growth, Survival and Physiological Responses of GIFT Fish Reared in Freshwater Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture System. Aquaculture 2024, 580, 740346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antwi, D.E.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Onumah, E.E.; Bhujel, R.C. Productivity and Constraints Analysis of Commercial Tilapia Farms in Ghana. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2017, 38, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jandoc, A.M. Technical Efficiency and Social Capital in Tilapia Aquaculture Production in Nueva Vizcaya, Philippines. Asian J. Agric. Dev. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, O.B. Learning-by-Doing or Technological Leapfrogging: PRODUCTION Frontiers and Efficiency Measurement in Norwegian Salmon Aquaculture. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2010, 14, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Unit | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production model | |||||

| Output value (y) | EGP | 1,040,977 | 1,056,944 | 64,500 | 8,720,000 |

| Inputs (x) | |||||

| Seeds (x1) | EGP | 49,678 | 51,820 | 740 | 400,000 |

| Labor (x2) | EGP | 28,119 | 26,580 | 1,800 | 180,000 |

| Feed (x3) | Kg | 45,788 | 38,549 | 4,000 | 350,000 |

| Land (x4) | Hectare | 5.38 | 5.05 | 0.42 | 50.4 |

| Firm specific variables (z) | |||||

| Farmer’s age (z1) | Years | 43.33 | 10.90 | 18 | 75 |

| Number of species cultured (z2) | Levels | 2.18 | 0.75 | 1 | 4 |

| Education level (z3) | Levels | 2.31 | 1.28 | 0 | 6 |

| Farm age (z4) | Years | 11.88 | 8.07 | 1 | 50 |

| Log likelihood value | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cobb Douglas | -57.779 | |

| Trans-log | -42.907 | |

| Test statistic | 29.742*** | |

| Decision | Reject the null hypothesis that trans log is not better than Cobb-Douglas | |

| Coefficient | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 11.78*** | 3.01 |

| ln (Feed) | -1.22** | 0.63 |

| ln (Labor) | 0.17 | 0.46 |

| ln (Seed) | 0.24 | 0.33 |

| ln (Land) | 0.93** | 0.43 |

| ln (Seed) x ln (Seed) | -0.03 | 0.04 |

| ln (Feed) x ln (Feed) | 0.18* | 0.1 |

| ln (Land) x ln (Land) | 0.07 | 0.05 |

| ln (Labor) x ln (Labor) | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| ln (Feed) x ln (Labor) | -0.005*** | 0.06 |

| ln (Feed) x ln (Seed) | 0.06** | 0.05 |

| ln (Feed) x ln (Land) | -0.26 | 0.06 |

| ln (Labor) x ln (Seed) | -0.05 | 0.03 |

| ln (Labor) x ln (Land) | 0.1** | 0.05 |

| ln (Seed) x ln (Land) | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| ) | 0.63*** | 0.09 |

| Sigma squared() | 0.13 *** | 0.02 |

| Average Technical efficiency (ATE) | 0.80 | |

| Input | Average elasticity | SE |

|---|---|---|

| Feed | 0.85*** | 0.04 |

| Labor | 0.07*** | 0.026 |

| Seed | 0.14*** | 0.024 |

| Land | 0.03 | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).