1. Introduction

Renal resistive index (RRI), an ultrasound vascular doppler-derived parameter, evaluates renal resistance and compliance; it was first described by Pourcelot in 197[

1,

2].

RRI was primarily explored as a diagnostic tool in situations in which intrarenal impedance is altered, particularly renovascular and chronic kidney disease, but it has recently been reported in critical care, where it may be able to capture changes in renal perfusion and to predict acute kidney injury [

3,

4].

Adequate organ perfusion is fundamental in critically ill (like ARDS or cardiac failure) patients. Intrarenal circulation is sensitive to fluctuations in systemic hemodynamics and such changes frequently mark an early sign of systemic circulatory afterload [

5]. Serum creatinine and urine output are indirect markers of the physiologic processes governing renal function but they are late and poor sensitive indicators of acute kidney injury. On the contrary, RRI provides real-time informations about renal hemodynamics, which may result in earlier recognition of renal dysfunction in acute setting and earlier interventions [

6].

.

The coordinated interplay of positive pressure ventilation, hypoxemia, and systemic inflammation exerts a direct influence on renal function in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [

7], with the renal resistance index potentially serving as an indicator of these complex interactions, thereby offering a novel marker of renal hemodynamics. Similarly, in heart failure (HF), RRI may reflect the interrelationships between cardiac output, venous congestion, and renal perfusion [

8].

The aim of this review is to evaluate the existing evidence regarding the use of RRI in both ARDS and HF. We will explore the physiological mechanisms underlying its relevance, the techniques employed for its measurement, clinical applications, and its prognostic value, while also addressing its limitations and considering future research directions.

2. Measuring RRI: Methodology

Doppler ultrasonography is a non-invasive imaging tecnique that allows to obtain real-time visualization of blood flow in renal vessels [

9]; RRI is assessed using Doppler ultrasonography. The procedure usually occurs with the patient typically either in the supine or in slight lateral decubitus to provide optimal exposure of the kidneys [

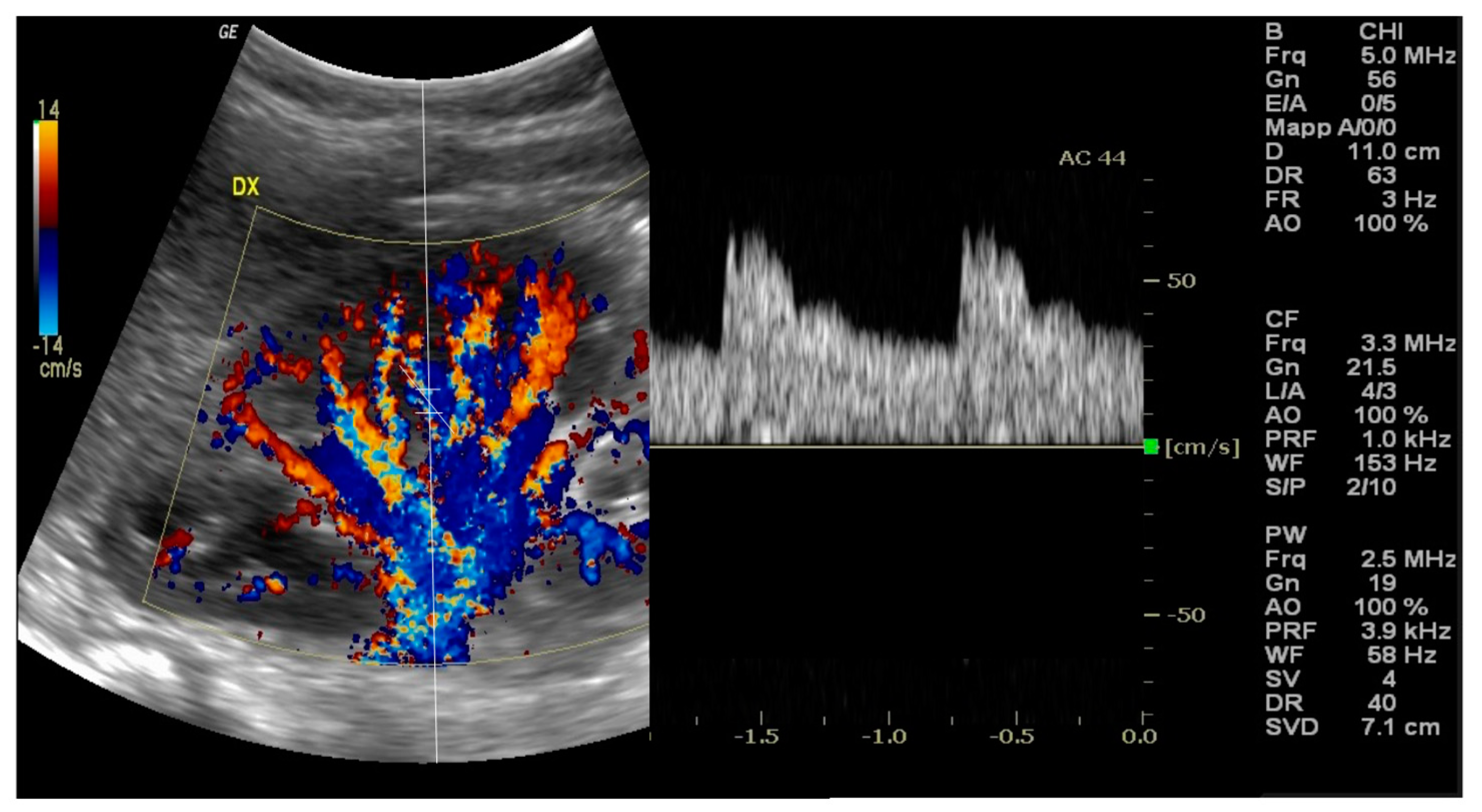

10]. The kidney is identified and its anatomy is evaluated via B-mode ultrasound, then Color Doppler augmentation allows to detect the main renal artery and its branches inside the kidney [

11] [

Figure 1].

A pulsed wave Doppler sample volume is located in an interlobar or arcuate artery at the corticomedullary junction in most cases [

12], in addition to the peak systolic velocity [PSV] and end-diastolic velocity [EDV] measurements from the arterial waveform. Therefore, RRI is then calculated using the formula: RRI = (Peak Systolic Velocity - End-Diastolic Velocity) / Peak Systolic Velocity [

2]. At least three measurements should be taken from separate interlobar arteries in each kidney, and the mean value is considered for the final RRI [

6].

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of RRI measurements, the following parameters should be considered:

Skills: RRI measurement needs a trained operator [

13] to achieve precise and repeatable results.

Standardized ultrasound machine settings, including Doppler gain, pulse repetition frequency, and wall filter should be used to minimize variability [

14].

Measurement site: performing measurements in the same location [i.e., always at the corticomedullary junction] is better for comparison [

15].

Patient Factors — Breath-holding, heart-rate, blood pressure can influence RRI and should be standardized or controlled accordingly [

16].

Time of assessment: For studies involving critically ill patients, RRI should be assessed after any intervention, as this will differ in terms of best practice [

17].

Inter- and intra-observer variability: this may be depend on various factors as discussed above [

18].

Reporting standards: this is a crucial factor for comparability between studies and implementation into the clinical practice [

19].

By the way, bedside RRI measurement is relatively fast and simple, so that it could be performed in most critical care units. Nevertheless, the awareness of methodological issues is a prerequisite for appropriate interpretation and use of RRI in such a context.

3. RRI in ARDS and HF: Pathophysiological Bases

Under physiological conditions, the kidneys are especially sensitive to variations in systemic hemodynamics [

5], receiving about 20–25% of cardiac output. The critical illness for example influences renal perfusion such as the changes in output, systemic vascular resistance and intravascular volume status [

20].

In patients with ARDS [

21], renal function and intrarenal hemodynamics are significantly influenced by the complex interaction between hypoxemia, inflammatory mediators, and positive pressure ventilation. Moreover, hypoxemia causes renal vasoconstriction as a compensatory mechanism to preserve oxygen delivery to other organs, but prolonged hypoxemia creates cellular injury and oxidative stress, both detrimental to renal function [

22]. Mechanical ventilation, one of the cornerstones of ARDS management, might considerably influence renal hemodynamics and, in turn, RRI: mechanical ventilation produces positive intrathoracic pressure that decreases venous return and may decrease cardiac output and renal perfusion [

23]. Mechanical ventilation is able both to increase right atrial pressure which, on its turn, may increase renal venous pressure and to decrease the transrenal perfusion pressure gradient [

24] also stimulating neurohumoral mechanisms such as the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system that influences renal vascular resistance and intrarenal circulation [

25]. These effects are magnified at higher levels of positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP] and in patients with baseline cardiac dysfunction [

26]. With initiation of mechanical ventilation, RRI has shown to increase and such an increase has been positively correlated to the degree of PEEP [

27], suggesting that it could reflect the pathophysiologic response to changes in the intrathoracic pressure, cardiac function and renal perfusion.

Both diminished cardiac output and increased venous pressure can result in changes in renal perfusion in cardiac failure [

28]. Low cardiac output results in decreased renal perfusion while declining renal perfusion increases renal vascular resistance as a compensatory mechanism [

29] and increased central venous pressure [especially in right heart failure] leads to renal congestion which causes increased renal interstitial pressure, thus affecting renal blood flow and glomerular filtration [

30,

31].

Consistent with these findings, RRI has been shown to correlate with cardiac function biomarkers like left ventricular ejection fraction and right atrial pressure in patients with both acute and chronic heart diseases [

32,

33]. Whereas neurohormonal activation [sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system] may contribute to further increase renal vascular resistance [

34], changes in RRI correlate with improvement in cardiac function with treatment, indicating that RRI may be predictive of response to therapy [

35].

4. RRI in ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS] is an extreme form of acute lung injury characterised by systemic inflammation impairing gas exchange and typically inducing the need of mechanical ventilation. The complexity of ARDS pathophysiology can deeply influence renal physiology. In this context, the RRI deserves greater attention as a noninvasive tool to assess renal perfusion and AKI susceptibility.

Many studies found an association between RRI and the severity of ARDS. Darmon et al. found that RRI values were also significantly higher in patients with moderate to severe ARDS if compared with mild ARDS or no ARDS patients[

27]. This association may be due to physiologic and pathophysiologic effects associated with severe lung injury, such as increased levels of inflammatory mediators and shifting hemodynamics that can affect renal perfusion.

In addition, RRI has also been associated with oxygenation variables in ARDS patients. Lahmer et al. [

36] found a strong inverse relationship between RRI and PaO2 /FiO2 ratio, a well-established marker of degree of oxygenation impairment in ARDS: RRI might become an additional marker of disease severity and this could potentially also help in monitoring the progression or improvement of ARDS.

Among the possible applications, RRI could become a predictor of AKI in ARDS. Oliveira et al. [

17] showed that high RRI levels predicted a more than double risk of AKI in critically ill patients, including those with ARDS, and found that a cut-off of 0.69 had sensitivity 85% and specificity 79% in predicting AKI within 72 h.

RRI has not only been valuable in predicting AKI, but also other important outcomes in patients with ARDS [

11].

An elevated RRI has been independently associated with the development of AKI in critically ill patients, including those with ARDS. The prognostic significance of RRI in managing ARDS has been highlighted by various studies, underscoring its potential utility in clinical decision-making. Furthermore, the ability of RRI to reflect renal hemodynamics in response to changes in ventilator settings and fluid management enhances its promise as a marker for guiding ARDS treatment [

37]. A recent retrospective study demonstrated that alterations in positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) were mirrored by corresponding changes in RRI, with increases in PEEP resulting in an elevated RRI and decreases in PEEP leading to a reduction in RRI. This finding supports the use of RRI to titrate PEEP, potentially minimizing nephron exposure to suboptimal renal perfusion.

Fluid optimization remains a critical aspect of clinical practice in ARDS management, and RRI could be an invaluable tool for guiding clinicians in preventing fluid excess without compromising organ perfusion.

Schneider et al. [

38] recently showed that changes in RRI in response to fluid challenges could predict fluid responsiveness in critically ill patients, suggesting that RRI may be used to guide fluid administration in ARDS patients. This approach could help maintain renal perfusion while avoiding the risks associated with fluid overload.

5. RRI in Heart Failure

Heart failure [HF] is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome defined by the heart’s inability to maintain sufficient cardiac output [CO] to satisfy body’s demands. HF may affect renal function through numerous mechanisms. RRI has proven to be useful for the evaluation of renal hemodynamics in patients with HF, providing information on complex cardiorenal interactions and possible prognostic data.

RRI is a multidimensional value in association with heart function in patients with HF. It has been shown that RRI is significantly related to CO and left ventricular function. Iacoviello et al. [

32]

In chronic HF patients, a high value of RRI was independently correlated with low left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] and the same results were found in patients with coronary heart disease [

33]. This relationship probably reflects the effects of decreased cardiac output on renal perfusion, resulting in increased renal vascular resistance as a compensatory response.

Notably, in recent years, there has been much interest in the association between the right ventricular [RV] function and RRI. Husain-Syed et al.[

39] showed that RRI is independently and strongly associated with RV dysfunction indices like tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion [TAPSE] and RV fractional area change. We focus here on this relationship, which is especially pertinent as RV function is critical to renal perfusion, particularly in the setting of high central venous pressure [CVP] common in right heart failure.

In HF, one of the most exciting potential uses of RRI is as a marker of venous congestion. Elevated central venous pressure has become increasingly recognized as an important mechanism of renal injury contributing to cardiorenal syndrome, manifesting as venous congestion. Nijst et al.[

8] Based on the transition between euvolemia and hypervolemia in HF patients, authors have shown that RRI rises substantially, thus suggesting that RRI could be a sensitive indicator of escalating venous congestion. This association of RRI with venous congestion is especially relevant when classic volume markers [e. g. central venous pressure measurement or clinical examination] could be unreliable or invasive.

In HF patients, a few studies have shown the prognostic significance of RRI. Ciccone et al. [

35] shown that RRI was an independent predictor of HF progression in chronic HF patients, and specifically that patients with abnormal RRI had a significantly higher risk of heart failure hospitalizations and mortality. Moreover, Ennezat et al. [

40] In another study by, they have proved RRI can predict negative outcomes in patients with decompensated heart failure admitted to hospital, and even found that RRI ≥ 0.70 could predict the increased risk of all-cause mortality and rehospitalization for heart failure. We proposed that the prognostic value of the RRI in heart failure can be explained by the capacity of the RRI to combine information on cardiac function, renal circulation and systemic hemodynamics [

41,

42]. Therefore, it gives an additional insight into the global cardiovascular health of the patient, possibly providing more comprehensive risk stratification than conventional markers alone [

43].

RRI could serve as a valuable tool in fluid management, particularly in the context of acute decompensated heart failure (HF). By providing insights into renal perfusion and venous congestion, RRI could enable clinicians to not only optimize volume status but also minimize renal dysfunction, thereby enhancing patient outcomes. Additionally, RRI holds potential as a marker for monitoring the response to HF therapy. For instance, in the study by Tudoran M. and Tudoran C. [

44], improvements in RRI were associated with clinical success in the treatment of acute heart failure, with a decrease in RRI values suggesting treatment efficacy. Finally, RRI also plays a prognostic role, aiding clinical decision-making for high-risk patients by providing crucial information on the patient’s renal and hemodynamic status.

6. Relationship of RRI with Other Organ Dysfunction Markers

As previously stated, in critical care setting RRI has been recently validated as a promising marker of renal impairment. But to assess the overall clinical value, RRI needs to be compared with other more validated organ dysfunction markers, both serum biomarkers and other ultrasonography detected parameters.

Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen [BUN] are traditional cornerstones in the evaluation of renal function. Nevertheless, they exhibit limitations such as the time-lag appearance of the markers in AKI and they can be influenced by conditions independent of renal function. By comparison, RRI assesses renal hemodynamics in real time, enabling earlier identification of renal dysfunction.

Several studies have compared RRI with novel biomarkers of kidney injury. Bossard et al.[

45] Our findings are consistent with a study by Macedo et al. in which they showed that although serum cystatin C can predict AKI in critically ill patients, neither the sensitivity nor the specificity was as good as RRI. An RRI ≥ 0.70 was found to have a sensitivity of 75% and specificity of 84% compared with cystatin C with a respective sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 80% to predict AKI.

Another promising biomarker for early AKI diagnosis is neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin [NGAL]. Schnell et al. [

11] In a group of septic patients who were not receiving antibiotics, compared RRI with plasma NGAL in the prediction of AKI and found that both markers were predictive of AKI, though RRI had a higher area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUROC] than NGAL [0.87 vs 0.80]. Nevertheless, these biomarkers and RRI have a different prognostic value. While biomarkers such as NGAL and cystatin C are related to cellular damage in kidney, RRI gives informations on renal hemodynamics. Hence, the combination of RRI and these biomarkers may yield a more accurate assessment of renal function than either biomarker or RRI alone.

Besides RRI, additional ultrasonographic parameters have been investigated for organ dysfunction assessment in critical care. For example, plenty of these parameters are included in the venous excess ultrasound [VExUS] score, which evaluates venous congestion through the examination of inferior vena cava [ICV] diameter and hepatic, portal, and intrarenal venous flow patterns. Beaubien-Souligny et al. [

46] have compared RRI vs the standard VExUS score for prediction of AKI following cardiac surgery. Both parameters were predictive for AKI; however, the combination of RRI and VExUS score was associated with a better predictive accuracy than either parameter alone. Echocardiography, as a specialist skill, is another ultrasonographic parameter commonly encountered in critical care, particularly with respect to assessment of left ventricular function. Nguyen et al. [

47] in patients suffering from septic shock, compared the relationship between RRI and echocardiographic parameters and AKI; both RRI and LVEF predicted AKI; however, for RRI, the AUROC was higher [0.86 vs 0.72]. Lung ultrasound is a key ultrasonographic tool in critical care to detect extravascular lung water, as well as in the diagnosis of conditions such as ARDS. Direct comparisons of lung ultrasound findings with RRI are limited, but both of them provide informations regarding fluid status and organ dysfunction. Additional studies comparing these parameters should be performed.

Due to the complexity of the pathophysiology behind critical illness, most commonly a multi-parameter integration will lead to the most comprehensive evaluation of the patients’ clinical conditions.

Darmon et al.[

6] in critically ill patients, proposed a model combining RRI and clinical and laboratory parameters to identify AKI reversibility; this model, including RRI, urinary output, and serum creatinine, was superior to any single parameter to predict renal recovery. Similarly, Oliveira et al.[

17] in critically ill patients, proposed a model based on RRI, Mean arterial Pressure, and serum lactate to predict AKI: this model showed an excellent predictive performance, suggesting that RRI, when combined with other clinical and laboratory parameters, can provide an even better risk stratification.

7. Limitations and Challenges

The most important limitation of RRI measurement is its operator-dependency. This need for technical skills can restrict the broader translation of RRI into clinical practice, especially in settings and areas where experienced sonographers may not be available. In addition, RRI can also be influenced by the type and quality of ultrasound equipment. Compared with older or portable devices, high-end machines with higher resolution and more sensitive Doppler capabilities may yield more accurate and reproducible findings [

2]. Differences in equipment quality therefore may cause heterogeneity of RRI reported in clinical settings or research studies.

Technical standardization of the RRI measurement is another issue. Although there are general recommendations for the specific vessels [interlobar, arcuate, or segmental arteries] and number of measurements taken and how these measurements are averaged [

10], there is often a certain degree of variability. This variability can complicate comparisons of results across studies, or even clinical practices.

The RRI might be affected by patient-specific factors among which age, as RRI become higher with advanced age, even without renal disease [

48] because vascular compliance is decreasing along with aging. Cardiovascular factors such as heart rate, blood pressure, and cardiac output can also affect RRI. Tachycardia can lead to an underestimation of RRI, while bradycardia can cause an overestimation [

49]. Likewise, blood pressure variations may affect RRI, where a rise in systemic blood pressure could provoke an RRI [

50] decrease. In critically ill patients, these hemodynamic effects may be crucial if we consider the fast and dramatic changes in these parameters.

Mechanical ventilation settings can substantially influence the measurement of RRI. PEEP increases RRI, presumably from the mechanical interaction between intrathoracic pressure and venous return [

27]. This is especially troublesome in ARDS patients, where high PEEP levels are frequently employed, and the incremental PEEP-induced changes could mislead the meaning of the changes of RRI.

Also pre-existing renal conditions affect RRI. Chronic kidney disease, renal artery stenosis, and other structural renal abnormalities may all cause baseline increases in RRI that may alter the real acute changes [

41,

42,

43,

51]. This aspect is especially crucial in multi-organ dysfunction [as commonly occurs in critically ill patients] and therefore RRI. In such complex scenarios, alterations in RRI might reflect renal alterations but also systemic effects of critical illness. Changes in RRI in patients with both ARDS and AKI, such as the septic ones, could be related to a combination of systemic inflammation, cardiac output changes, mechanical ventilation effects and intrinsic renal disease [

52]. Likewise, in patients with concomitant heart and kidney dysfunction, changes in RRI might not be so easy to understand. Rising RRI might indicate worsening heart function or progression of renal damage, or both [

33],[

35]. Moreover, RRI is a dynamic index that can also rapidly change over time under the influence of many factors.

In summary, despite its limitations and challenges, the renal RRI holds promise as a valuable tool in critical care. It offers a novel advantage over existing invasive renal hemodynamic monitoring methods by providing real-time information. However, clinicians and researchers must be mindful of these limitations and interpret RRI results within a broader context, incorporating other clinical and laboratory parameters. Overcoming these limitations will be crucial for fully realizing the potential benefits of RRI in critical care. This includes the development of standardized protocols for RRI assessment, conducting larger studies to elucidate the interactions between individual physiological factors and RRI, and exploring how RRI measurements can be integrated with other clinical and biochemical markers to enhance its utility in complex multi-organ dysfunction scenarios.

8. Future Directions

One of the primary research priorities moving forward is the standardization of measurement techniques. Standardized protocols for RRI measurement need to be developed and validated, including the identification of optimal measurement sites, the determination of the appropriate number of measurements and the averaging procedure, as well as the standardization of equipment settings. Implementing a uniform data acquisition approach would substantially enhance the reproducibility of RRI measurements across different operators and clinical environments, thereby strengthening its utility as both a research and clinical tool [

19].

Further research could come from technical innovations through the development of automated RRI measurement methods, novel ultrasound technologies to enhance the accuracy and precision of RRI measurements. Post-operative renal perfusion could be monitored continuously on a real-time basis, and continuous RRI monitoring technologies [

18] might offer insight into RRI assessment in the critical care settings.

The first study by Samoni et al. includes Intra-Parenchymal Renal Resistive Index Variation (IRRIV) based on a pole-to-pole assessment of Renal Functional Reserve (RFR) [

53], an excellent indicator of the dynamic functional reserve of the kidney expressed as the range of RRI values between the maximum and minimum throughout a given time-period with the more subtle changes in RRI correlating closely with changes in renal perfusion. IRRIV was initially tested in healthy volunteers but has potential utility in patients with ARDS or HF. It could help in the early diagnosis of AKI, in decisions about renal replacement therapy, and provide more precise informations about renal function in complicated hemodynamic conditions. Future studies are needed to validate this concept in critically ill.

RRI association with other clinical and laboratory variables is also a potential topic for future investigation. AI and machine learning algorithms might add RRI to other patient data providing a more complete evaluation. Finally, the assessment of RRI along with new kidney injury biomarkers may help to enhance risk stratification approaches [

54,

55].

Further studies, however, are needed to understand what influences RRI, for example, the determination of age-specific and comorbidity-specific reference ranges for RRI. Hence we could identify some clues to detect genetic factors that may contribute to the RRI and to the effect of therapies [

48].

RRI research also needs longitudinal studies to assess the prognostic significance of time-dependent RRI changes or to assess the effect of RRI-based management strategies on long-term outcomes or the effect of acute change in RRI on long-term renal function [

4].

Interventional studies are required to address whether RRI-guided fluid management protocols are superior to standard protocols in patients with ARDS or HF. Renal replacement therapy guided by RRI and RRI-defined ventilation strategies in patients with ARDS [

37] also are worthy of interest.

In multi-organ dysfunction, further studies should be conducted to determine the relative contributions of individual organs to changes in RRI. [

52]. Further, while the majority of RRI research has been conducted with adults, application in pediatric and neonatal critical care settings is auspicable after an accurate determination of age-dependent ranges for RRI in pediatric and neonatal populations, use of RRI in fluid management of critically ill children, and the applicability of RRI for assessment of renal function in premature infants [

56].

Finally, the cost-effectiveness of RRI needs to be assessed in critical care settings [

13].

9. Conclusions

Recent studies have identified the renal resistance index (RRI) as a promising non-invasive tool that provides valuable insights into renal hemodynamic status in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and heart failure. RRI has demonstrated its utility in risk stratification, fluid management, and treatment response assessment, with associations noted between RRI and disease severity, oxygenation parameters, and the risk of acute kidney injury.

While RRI holds significant potential in critical care settings, several challenges hinder its broader application, including operator dependence, the need for standardized measurement protocols, and difficulties in interpretation, particularly in the context of multi-organ dysfunction. Despite these challenges, there remains considerable potential for enhancing the utility of RRI through future research aimed at addressing these limitations.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pourcelot, L. Applications cliniques de l’examen Doppler transcutane. In: Peronneau P, editor. Velocimetrie Ultrasonore Doppler. Paris: INSERM; 1974. p. 213-240. In.

- Tublin ME, Bude RO, Platt JF. The Resistive Index in Renal Doppler Sonography: Where Do We Stand? Am J Roentgenol. aprile 2003;180(4):885–92.

- Schnell D, Darmon M. Renal Doppler to assess renal perfusion in the critically ill: a reappraisal. Intensive Care Med. novembre 2012;38(11):1751–60. [CrossRef]

- Ninet S, Schnell D, Dewitte A, Zeni F, Meziani F, Darmon M. Doppler-based renal resistive index for prediction of renal dysfunction reversibility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crit Care. giugno 2015;30(3):629–35. [CrossRef]

- Prowle JR, Molan MP, Hornsey E, Bellomo R. Measurement of renal blood flow by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging during septic acute kidney injury: A pilot investigation*. Crit Care Med. giugno 2012;40(6):1768–76.

- Darmon M, Schortgen F, Vargas F, Liazydi A, Schlemmer B, Brun-Buisson C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of Doppler renal resistive index for reversibility of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. gennaio 2011;37(1):68–76. [CrossRef]

- Koyner JL, Murray PT. Mechanical Ventilation and the Kidney. Blood Purif. 2010;29(1):52–68. [CrossRef]

- Nijst P, Martens P, Dupont M, Tang WHW, Mullens W. Intrarenal Flow Alterations During Transition From Euvolemia to Intravascular Volume Expansion in Heart Failure Patients. JACC Heart Fail. settembre 2017;5(9):672–81. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, WC. Renal Resistive Index: A Case of Mistaken Identity. Hypertension. novembre 2014;64(5):915–7.

- Granata A, Zanoli L, Clementi S, Fatuzzo P, Di Nicolò P, Fiorini F. Resistive intrarenal index: myth or reality? Br J Radiol. giugno 2014;87(1038):20140004.

- Schnell D, Deruddre S, Harrois A, Pottecher J, Cosson C, Adoui N, et al. Renal Resistive Index Better Predicts the Occurrence of Acute Kidney Injury Than Cystatin C. Shock. dicembre 2012;38(6):592–7. [CrossRef]

- Boddi M, Bonizzoli M, Chiostri M, Begliomini D, Molinaro A, Tadini Buoninsegni L, et al. Renal Resistive Index and mortality in critical patients with acute kidney injury. Eur J Clin Invest. marzo 2016;46(3):242–51. [CrossRef]

- Schnell D, Reynaud M, Venot M, Le Maho AL, Dinic M, Baulieu M, et al. Resistive Index or color-Doppler semi-quantitative evaluation of renal perfusion by inexperienced physicians: results of a pilot study. Minerva Anestesiol. dicembre 2014;80(12):1273–81.

- Dietrich CF, Averkiou M, Nielsen MB, et al. How to perform Doppler ultrasound in pregnancy. Ultraschall Med. 2021;42(5):497-512.

- Geraci G, Mulè G, Mogavero M, Geraci C, Nardi E, Cottone S. Association Between Uric Acid and Renal Hemodynamics: Pathophysiological Implications for Renal Damage in Hypertensive Patients. J Clin Hypertens. ottobre 2016;18(10):1007–14. [CrossRef]

- Lahmer T, Rasch S, Schnappauf C, Schmid RM, Huber W. Influence of volume administration on Doppler-based renal resistive index, renal hemodynamics and renal function in medical intensive care unit patients with septic-induced acute kidney injury: a pilot study. Int Urol Nephrol. agosto 2016;48(8):1327–34. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira RAG, Mendes PV, Park M, Taniguchi LU. Factors associated with renal Doppler resistive index in critically ill patients: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intensive Care. dicembre 2019;9(1):23. [CrossRef]

- Corradi F, Brusasco C, Vezzani A, Palermo S, Altomonte F, Moscatelli P, et al. Hemorrhagic Shock in Polytrauma Patients: Early Detection with Renal Doppler Resistive Index Measurements. Radiology. luglio 2011;260(1):112–8. [CrossRef]

- Schnell D, Darmon M. Bedside Doppler ultrasound for the assessment of renal perfusion in the ICU: advantages and limitations of the available techniques. Crit Ultrasound J. dicembre 2015;7(1):8. [CrossRef]

- Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Ronco C. Acute kidney injury. The Lancet. agosto 2012;380(9843):756–66.

- Koyner JL, Murray PT. Mechanical Ventilation and Lung–Kidney Interactions. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. marzo 2008;3(2):562–70. [CrossRef]

- Sharfuddin AA, Molitoris BA. Pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. Nat Rev Nephrol. aprile 2011;7(4):189–200. [CrossRef]

- Pinsky, MR. Cardiovascular Issues in Respiratory Care. Chest. novembre 2005;128(5):592S-597S.

- Kuiper JW, Groeneveld ABJ, Slutsky AS, Plötz FB. Mechanical ventilation and acute renal failure*: Crit Care Med. giugno 2005;33(6):1408–15.

- Lionetti V, Recchia FA, Marco Ranieri V. Overview of ventilator-induced lung injury mechanisms: Curr Opin Crit Care. febbraio 2005;11(1):82–6.

- Luecke T, Pelosi P. Clinical review:Positive end-expiratory pressure and cardiac output. Crit Care. 2005;9(6):607. [CrossRef]

- Darmon M, Schortgen F, Leon R, Moutereau S, Mayaux J, Di Marco F, et al. Impact of mild hypoxemia on renal function and renal resistive index during mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med. giugno 2009;35(6):1031–8. [CrossRef]

- Mullens W, Abrahams Z, Francis GS, Sokos G, Taylor DO, Starling RC, et al. Importance of Venous Congestion for Worsening of Renal Function in Advanced Decompensated Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. febbraio 2009;53(7):589–96. [CrossRef]

- Nohria A, Hasselblad V, Stebbins A, Pauly DF, Fonarow GC, Shah M, et al. Cardiorenal Interactions:insights from the ESCAPE trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. aprile 2008;51(13):1268–74.

- Gnanaraj JF, Von Haehling S, Anker SD, Raj DS, Radhakrishnan J. The relevance of congestion in the cardio-renal syndrome. Kidney Int. marzo 2013;83(3):384–91. [CrossRef]

- Damman K, Van Deursen VM, Navis G, Voors AA, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Hillege HL. Increased Central Venous Pressure Is Associated With Impaired Renal Function and Mortality in a Broad Spectrum of Patients With Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. febbraio 2009;53(7):582–8. [CrossRef]

- Iacoviello M, Nonarella A, Guida P, et al. Renal resistive index predicts worsening renal function in chronic heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(14):E237.

- Geraci G, Buccheri D, Zanoli L, Fatuzzo P, Di Natale K, Zammuto M, et al. Renal haemodynamics and coronary atherosclerotic burden are associated in patients with hypertension and mild coronary artery disease. Exp Ther Med [Internet]. 15 febbraio 2019 [citato 9 novembre 2024]; Disponibile su: http://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/etm.2019.7279. [CrossRef]

- Schrier RW, Abraham WT. Hormones and Hemodynamics in Heart Failure. Epstein FH, curatore. N Engl J Med. 19 agosto 1999;341(8):577–85. [CrossRef]

- Ciccone MM, Iacoviello M, Gesualdo L, Puzzovivo A, Antoncecchi V, Doronzo A, et al. The renal arterial resistance index: a marker of renal function with an independent and incremental role in predicting heart failure progression. Eur J Heart Fail. febbraio 2014;16(2):210–6. [CrossRef]

- Lahmer T, Treiber M, von Dossow V, et al. Renal effects of dexmedetomidine in the critically ill: A retrospective case-control study. J Crit Care. 2016;35:133-137.

- Deruddre S, Cheisson G, Mazoit JX, Vicaut E, Benhamou D, Duranteau J. Renal arterial resistance in septic shock: effects of increasing mean arterial pressure with norepinephrine on the renal resistive index assessed with Doppler ultrasonography. Intensive Care Med. 22 agosto 2007;33(9):1557–62. [CrossRef]

- Schneider AG, Goodwin MD, Schelleman A, Bailey M, Johnson L, Bellomo R. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound to evaluate changes in renal cortical perfusion around cardiac surgery: a pilot study. Crit Care. 12 luglio 2013;17(4):R138. [CrossRef]

- Husain-Syed F, Birk H, Ronco C, Schörmann T, Tello K, Richter MJ, et al. Doppler-Derived Renal Venous Stasis Index in the Prognosis of Right Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 5 novembre 2019;8(21):e013584. [CrossRef]

- Ennezat PV, Maréchaux S, Six-Carpentier M, Pinçon C, Sediri I, Delsart P, et al. Renal resistance index and its prognostic significance in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nephrol Dial Transplant. dicembre 2011;26(12):3908–13. [CrossRef]

- Geraci G, Mulè G, Paladino G, Zammuto MM, Castiglia A, Scaduto E, et al. Relationship between kidney findings and systemic vascular damage in elderly hypertensive patients without overt cardiovascular disease. J Clin Hypertens. dicembre 2017;19(12):1339–47. [CrossRef]

- Geraci G, Zammuto MM, Cottone S, Mulè G. Renal resistive index: Beyond the hemodynamics. J Clin Hypertens. luglio 2020;22(7):1288–9. [CrossRef]

- Mulè G, Geraci G, Geraci C, Morreale M, Cottone S. The renal resistive index: is it a misnomer? Intern Emerg Med. dicembre 2015;10(8):889–91.

- Tudoran M, Tudoran C. Acute heart failure syndrome: the relationship between renal resistive index and NT-proBNP as a predictor for the outcome. Med Ultrason. 2017;19(3):295-301.

- Bossard G, Bourgoin P, Corbeau JJ, Huntzinger J, Beydon L. Early detection of postoperative acute kidney injury by Doppler renal resistive index in cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Br J Anaesth. dicembre 2011;107(6):891–8. [CrossRef]

- Beaubien-Souligny W, Benkreira A, Robillard P, Bouabdallaoui N, Chassé M, Desjardins G, et al. Alterations in Portal Vein Flow and Intrarenal Venous Flow Are Associated With Acute Kidney Injury After Cardiac Surgery: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2 ottobre 2018;7(19):e009961. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen HB, Losey T, Rasmussen J, Oliver R, Guptill M, Wittlake WA, et al. Interrater reliability of cardiac output measurements by transcutaneous Doppler ultrasound: implications for noninvasive hemodynamic monitoring in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. novembre 2006;24(7):828–35. [CrossRef]

- Ponte B, Pruijm M, Ackermann D, Vuistiner P, Eisenberger U, Guessous I, et al. Reference Values and Factors Associated With Renal Resistive Index in a Family-Based Population Study. Hypertension. gennaio 2014;63(1):136–42. [CrossRef]

- Bude RO, Rubin JM. Relationship between the Resistive Index and Vascular Compliance and Resistance. Radiology. maggio 1999;211(2):411–7. [CrossRef]

- Rim SJ, Leong-Poi H, Lindner JR, Wei K, Fisher NG, Kaul S. Decrease in Coronary Blood Flow Reserve During Hyperlipidemia Is Secondary to an Increase in Blood Viscosity. Circulation. 27 novembre 2001;104(22):2704–9.

- Radermacher J, Chavan A, Bleck J, Vitzthum A, Stoess B, Gebel MJ, et al. Use of Doppler Ultrasonography to Predict the Outcome of Therapy for Renal-Artery Stenosis. N Engl J Med. 8 febbraio 2001;344(6):410–7. [CrossRef]

- Dewitte A, Coquin J, Meyssignac B, Joannès-Boyau O, Fleureau C, Roze H, et al. Doppler resistive index to reflect regulation of renal vascular tone during sepsis and acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 12 settembre 2012;16(5):R165. [CrossRef]

- Samoni S, Nalesso F, Meola M, Villa G, De Cal M, De Rosa S, et al. Intra-Parenchymal Renal Resistive Index Variation (IRRIV) Describes Renal Functional Reserve (RFR): Pilot Study in Healthy Volunteers. [CrossRef]

- Geraci G, Sorce A, Mulè G. The “Renocentric Theory” of Renal Resistive Index: Is It Time for a Copernican Revolution? J Rheumatol. aprile 2020;47(4):486–9.

- Haitsma Mulier JLG, Rozemeijer S, Röttgering JG, Spoelstra-de Man AME, Elbers PWG, Tuinman PR, et al. Renal resistive index as an early predictor and discriminator of acute kidney injury in critically ill patients; A prospective observational cohort study. Burdmann EA, curatore. PLOS ONE. 11 giugno 2018;13(6):e0197967.

- Bude RO, DiPietro MA, Platt JF, Rubin JM, Miesowicz S, Lundquist C. Age dependency of the renal resistive index in healthy children. Radiology. agosto 1992;184(2):469–73. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).