Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

10 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Investigation of Monitoring Models

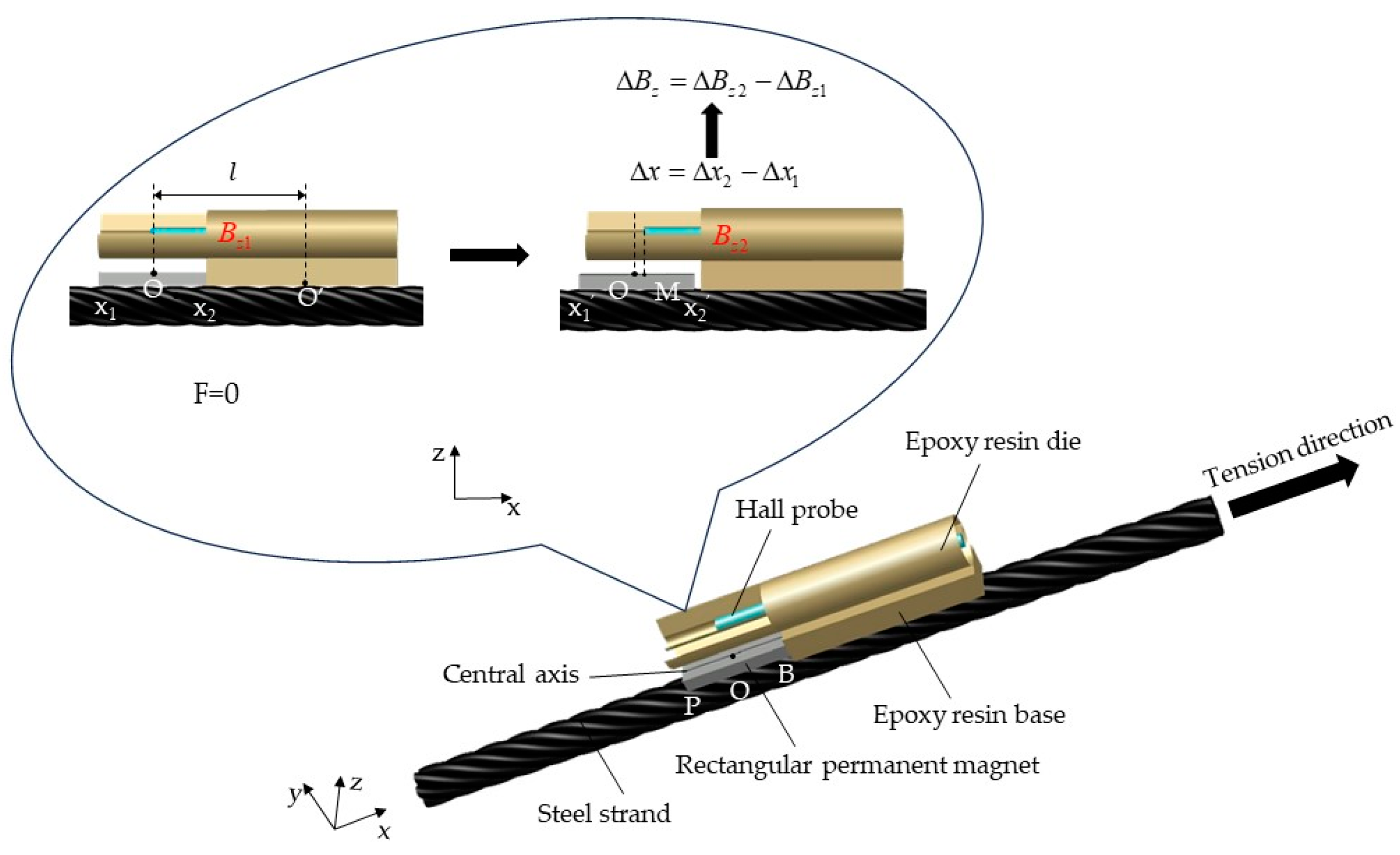

2.1. Monitoring Principles:

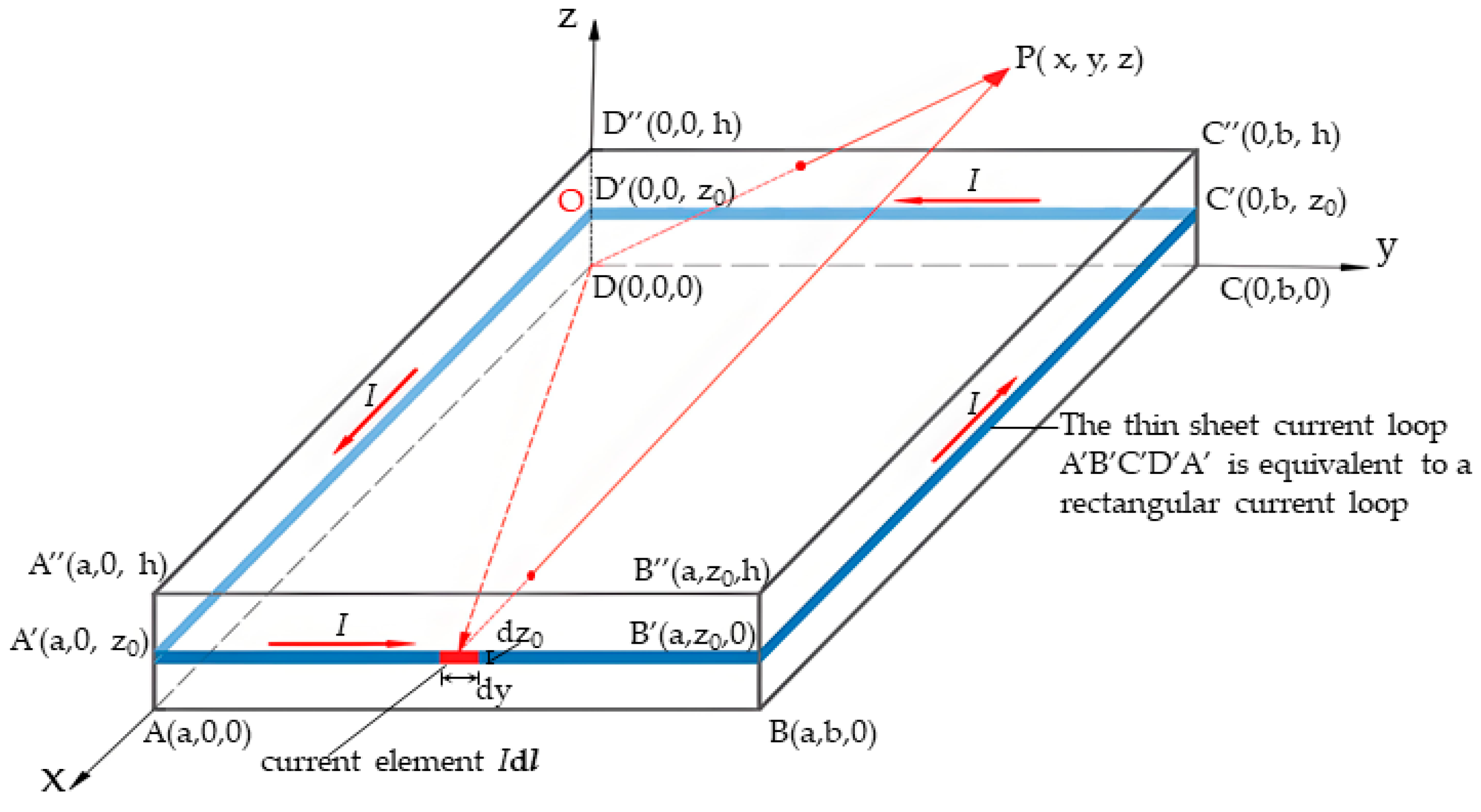

2.2. Analysis of the Spatial Magnetic Field Distribution of Permanent Magnets:

2.3. Force-Magnetic Coupling Monitoring Model

3. Simulation Analysis of the Monitoring Theoretical Model

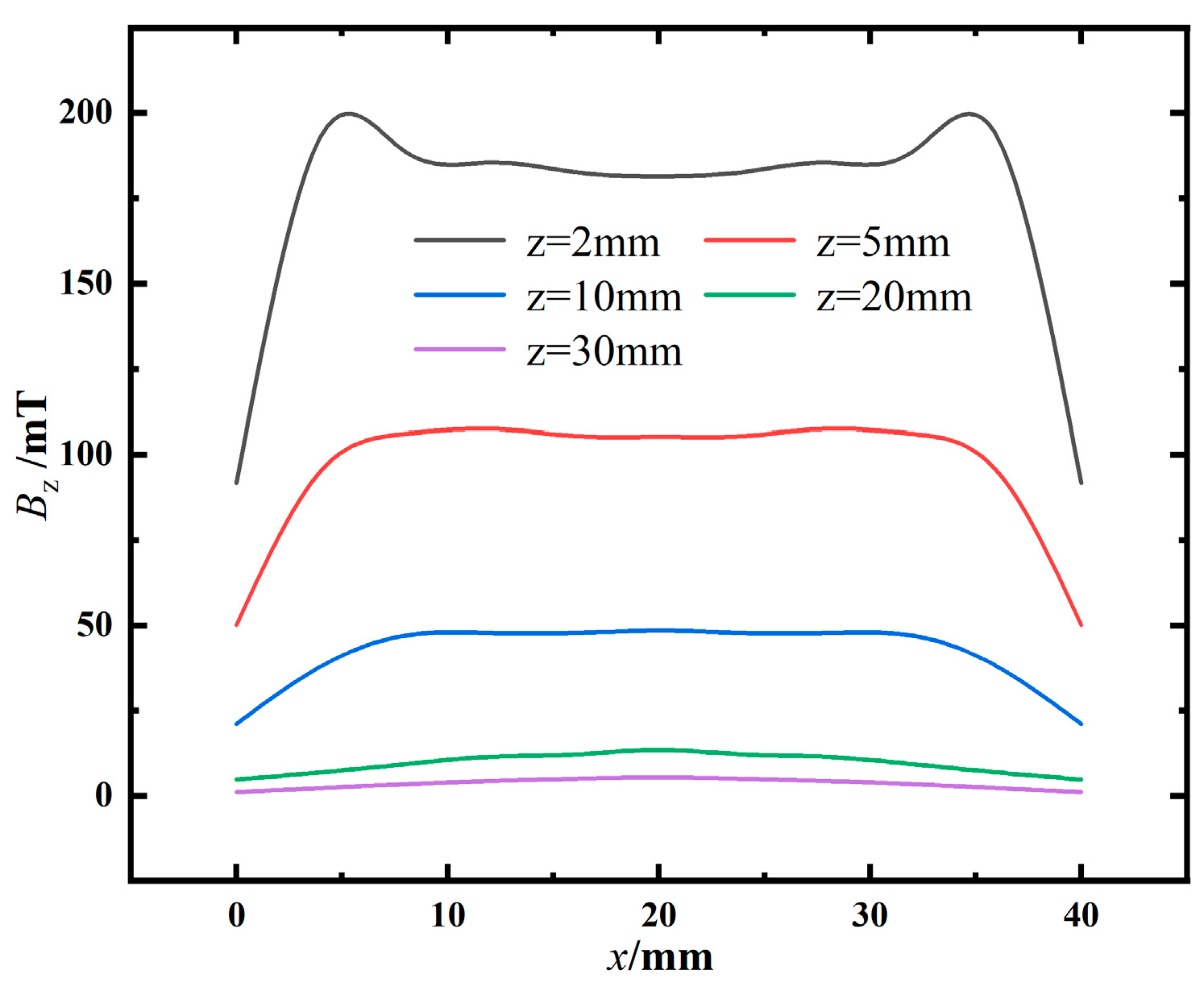

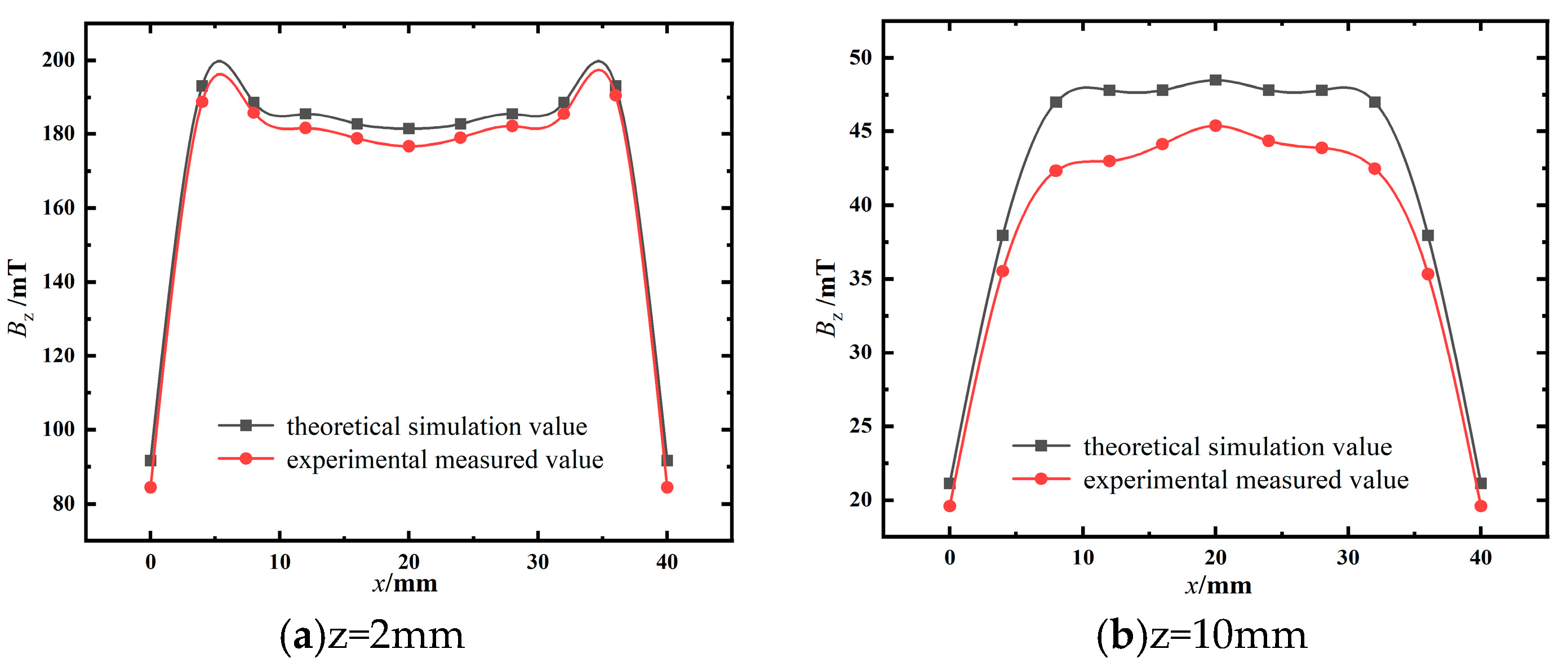

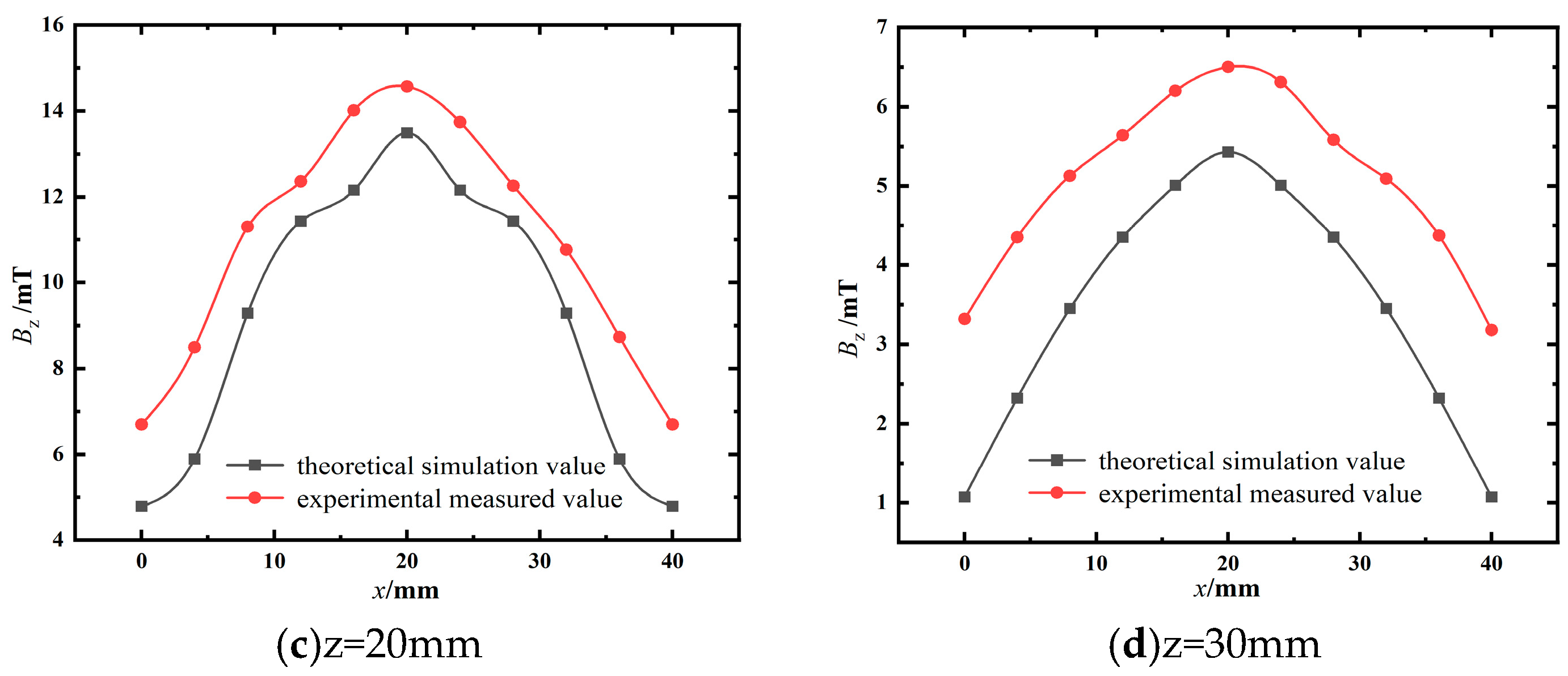

3.1. Simulation and Comparison of the Magnetic Field of a Rectangular Permanent Magnet

3.2. Force-Magnetic Coupling Theoretical Simulation.

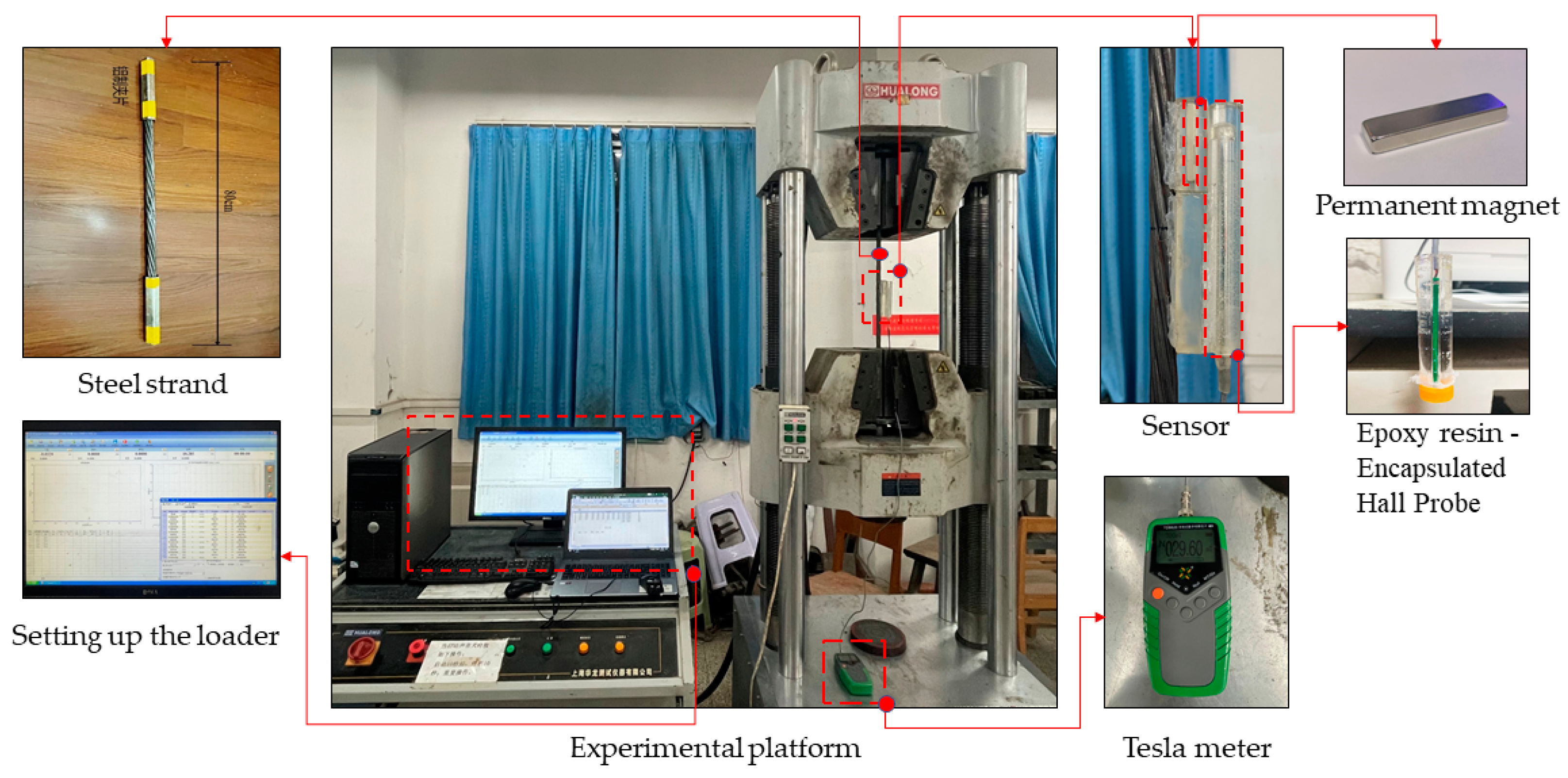

4. Experimental Study

4.1. Subsection

4.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

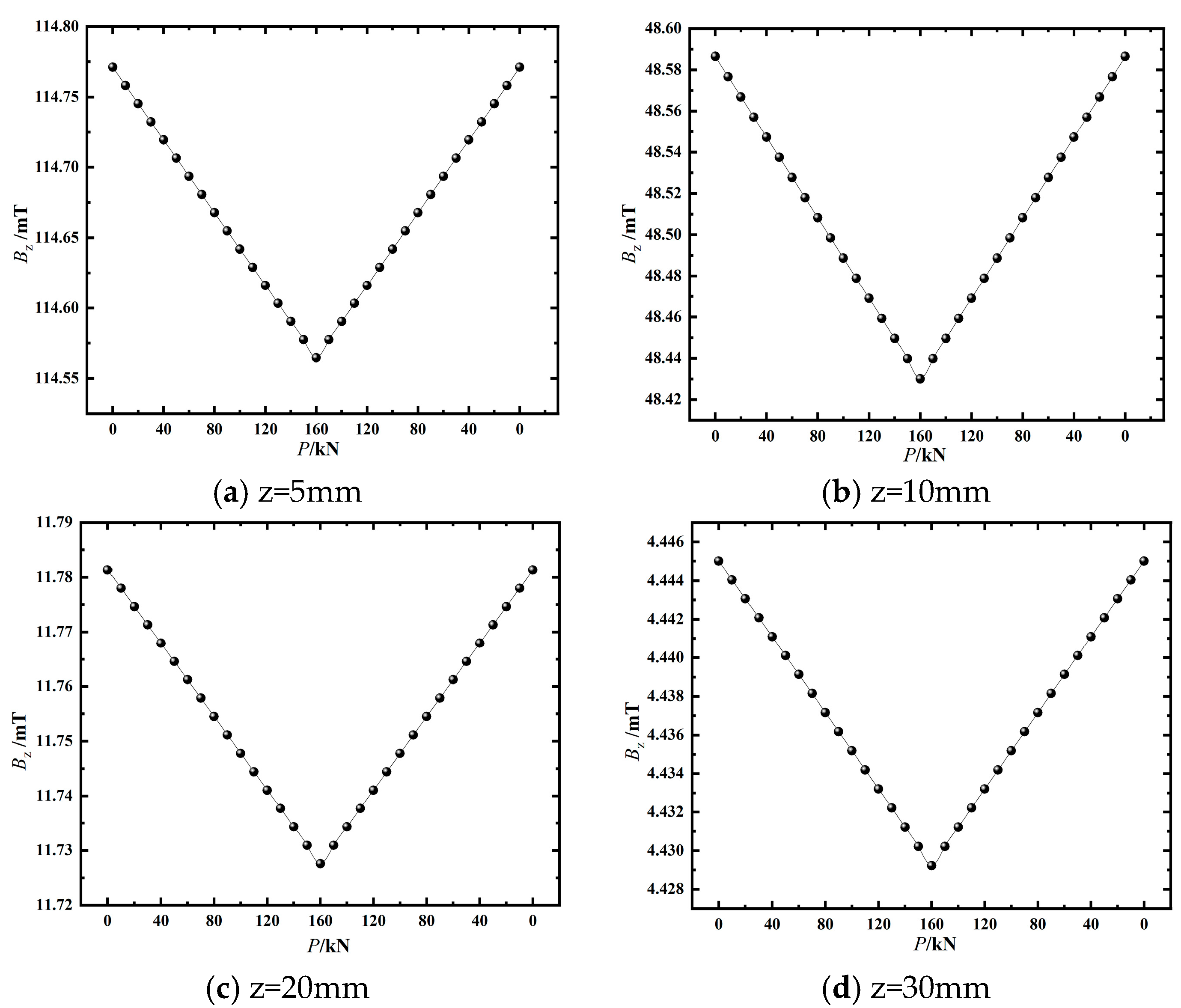

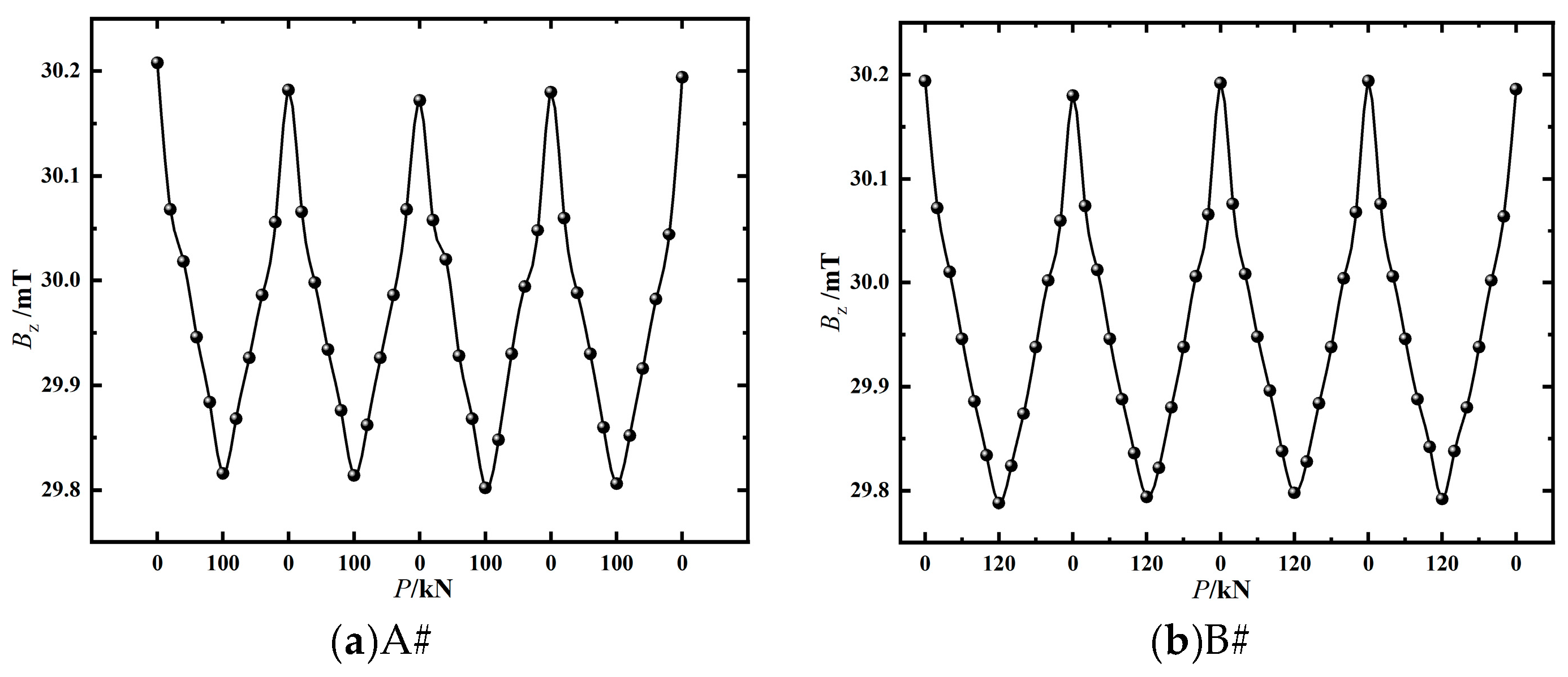

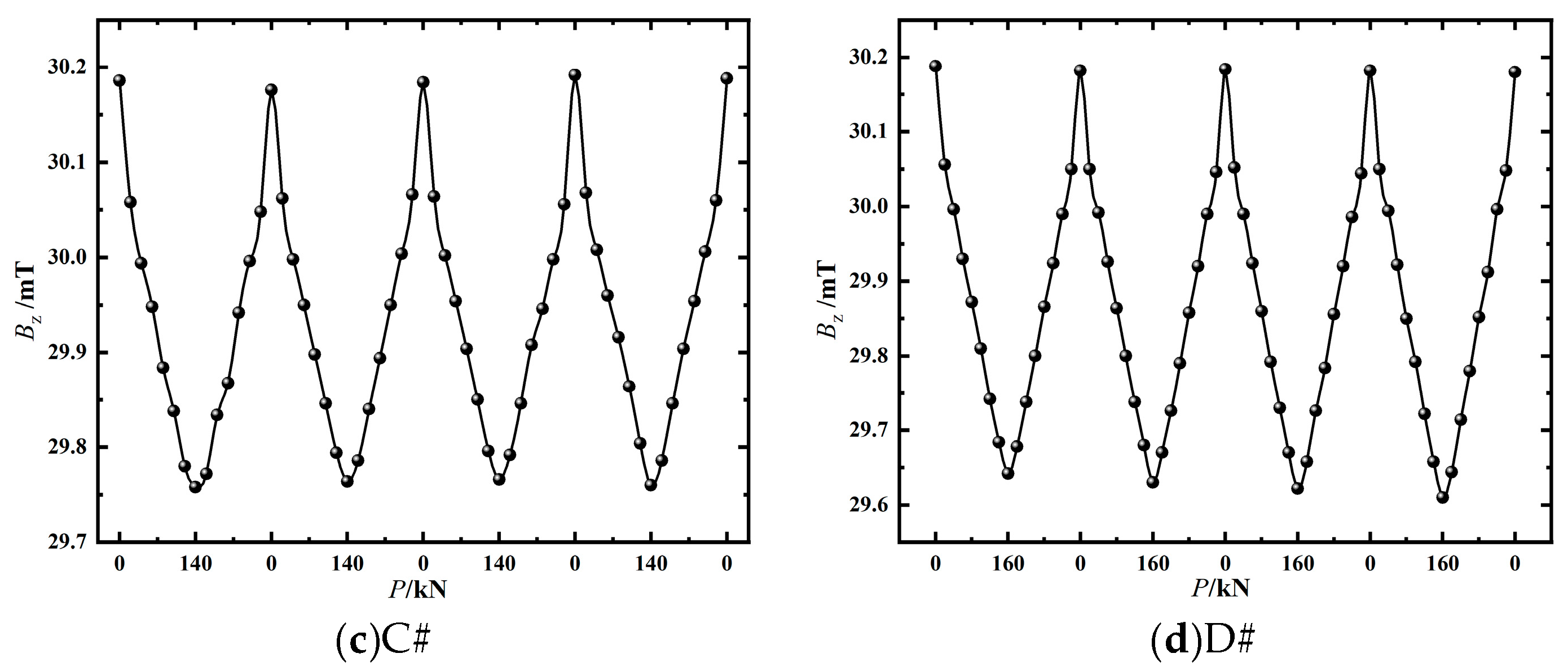

4.2.1. Relationship Between Magnetic Induction Intensity and Load

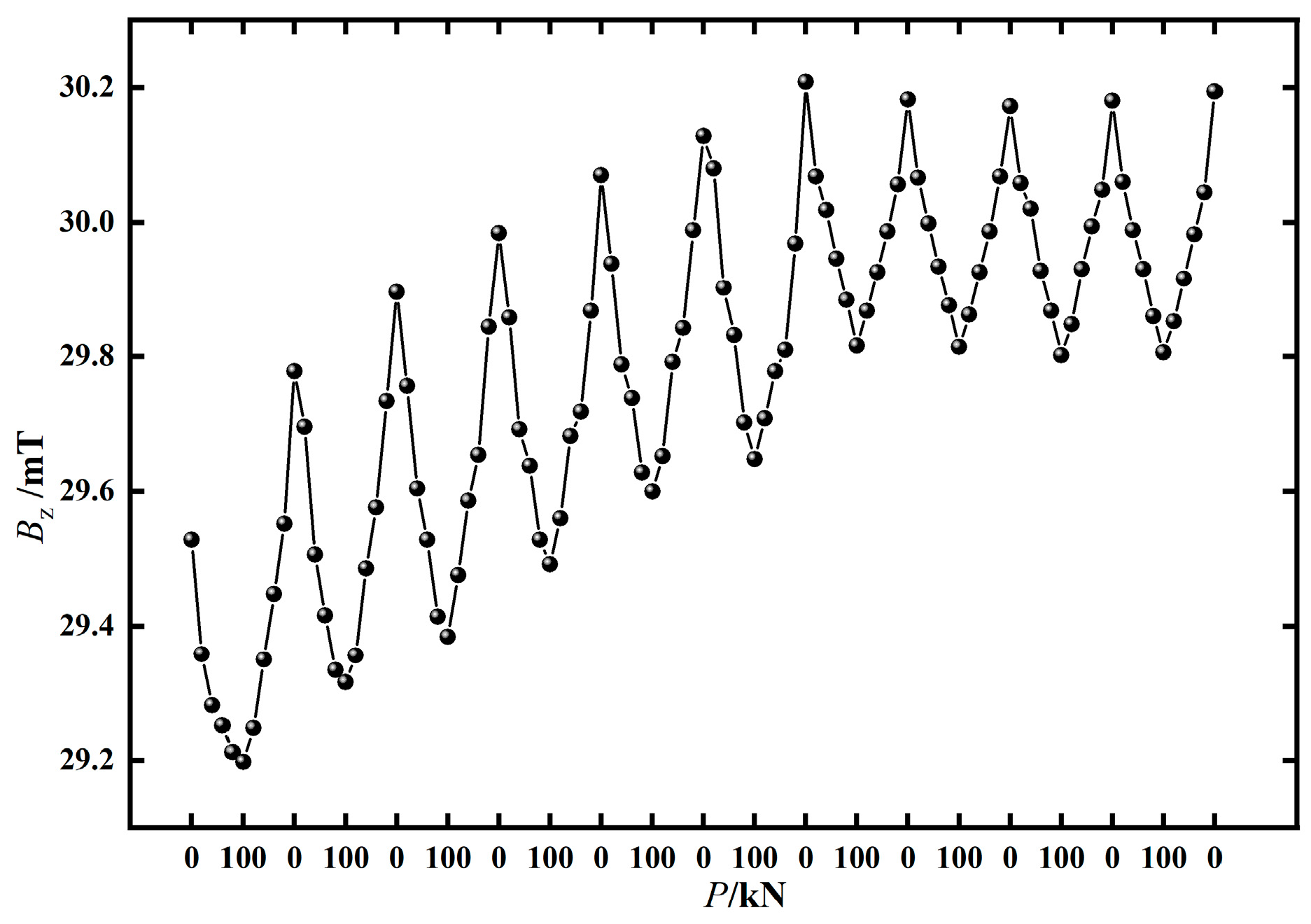

4.2.2. Analysis of the Repeatability of Test Data

5. Conclusions

- By combining the molecular circulation model and the Biot-Savart law, an analytical expression for the spatial magnetic field distribution of a rectangular permanent magnet was derived. This expression was then coupled with the stress-strain characteristics of the steel strand to establish a theoretical monitoring model that relates the anchor cable tensile force to the magnetic induction intensity of the permanent magnet. By monitoring the magnetic signal, the magnitude of the anchor cable force can be determined, thereby enabling effective anchor cable force monitoring.

- Using MATLAB, the distribution pattern of the magnetic induction intensity Bz and the force-magnetic relationship in the anchor cable force monitoring model were studied. The results showed that the z-component of the magnetic induction intensity Bz is symmetrically distributed about the central point. On the surface of the permanent magnet, the variation in Bz forms a 'downward concave' curve, and as the lift-off height z increases, Bz transforms into an 'upward convex' curve, approximately following a quadratic distribution. Notably, the value of Bz decreases as the tensile force increases.

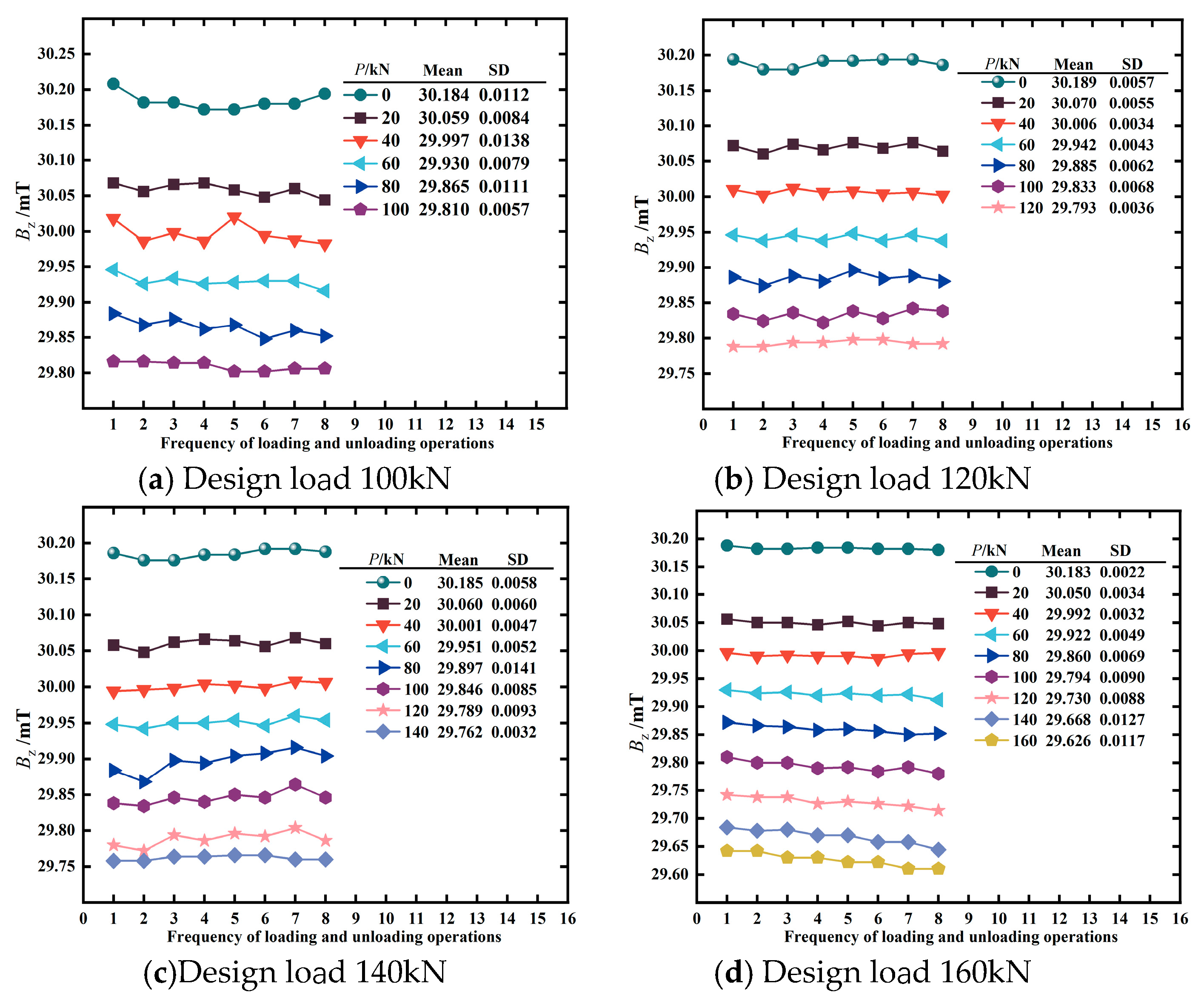

- The indoor experimental results indicate that the magnetic induction intensity Bz decreases as the tensile force increases, demonstrating a negative correlation consistent with the simulation results. The quadratic function effectively describes the relationship between force and magnetic field. Repeatability analysis of the test data shows that the standard deviation of the magnetic induction intensity Bz collected under the design loads is less than 1.5%, indicating low data dispersion and good stability of the monitoring technique. These results verify the effectiveness and applicability of the proposed monitoring technique.

- Given the constraints of the current study, this paper investigates the magnetic signal distribution characteristics along the z-axis of the rectangular permanent magnet sensing structure and its correlation with the applied load. Further research could address the three-dimensional magnetic signal distribution and its associated relationship with the load.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Y.; Ling, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhao, Y.; An, X.; Yi, T. Experimental Study on Internal Monitoring Structure of A New Prestressed Anchor Cable. Chinese Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 2020, 42, 226–230. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Hou, Q.; Ji, Z.; Zhang, D.; Xia, C.; Liu, C.; Zhao, H. Analysis of retaining system of secant pile- rotary anchor cable for foundation pit excavation. Journal of Railway Engineering Society, 2022, 284, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, G.; Dai, L.; Cheng, T.; Xi, B.; Chen, M.; Yang, J. A modified bearing capacity model for inclined shallow anchor cable with experimental verification. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Y. A long-term monitoring method of corrosion damage of prestressed anchor cable. Micromachines. 2023, 14, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, T.; Liu, H.; Zheng, J.; Yu, X.; Li, Y.; Peng, H. Study on the effect of anchor cable prestress loss on foundation stability. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Huang, C.; Chen, Y.; Dong, Q.; Sui, W. Development of a novel resilient anchor cable and its large shear deformation performance. International Journal of Rock Mechanics and Mining Sciences, 2023, 163, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Wu, X.; Tian, Y.; Xie, X. Analysis of re-tensioning time of anchor cable based on new prestress loss model. Mathematics. 2021, 9, 1094–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Jia, J.; Bao, X.; Mei, G.; Zhang, L.; Tu, B. Investigation of dynamic responses of slopes in various anchor cable failure modes. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering. 2025, 188(PartB), 109077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.H.; Li, J.H.; Qin, H.Y. Application of FBG self-sensing prestressed anchor cable in slope engineering. Journal of China Foreign Highway, 2021, 41, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Yao, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, Y. Cable force measurement technology and engineering application. Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures. 2021, 62, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Qu, L.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Xie, L.; Du, S. Design and application of bridge monitoring system based on vibrating wire sensors. Journal of North University of China (natural science editon), 2021, 42, 468–474. [Google Scholar]

- Branko, G. Concise historic overview of strain sensors used in the monitoring of civil structures: the first one hundred years. Sensors. 2022, 22, 2397–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Ou, J. An NCFA-based notch frequency feature extraction method for guided waves and its application in steel strand tension detection. J. Bridge Eng. 2023, 28, 04023099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, C. Application of intelligent monitoring and collection instrument in monitoring of urban rail foundation pit. Railway Investigation & Surveying. 2023, 49, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tu, C.; Wu, H.; Zhu, H.; Wu, J.; Fang, W. Testing method for internal stress of materials. Physical Testing and Chemical Analysis(Part A(Physical Testing)). 2020, 56, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Wei, C.; Wang, W. A new detection method based on magnetic leakage theory and bp neural network for broken steel strands in ACSR conductor. IEEE Sensors Journal. 22, 19620-19634.

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, E.; Pan, S. A new signal processing method for the nondestructive testing of a steel wire rope using a small device. NDT&E International. 2020, 102299.

- Liu, S.; Cheng, C.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, J.; Tong, K. A stress measurement method for steel strands based on spatially self-magnetic flux leakage field. Buildings. 2023, 13, 2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Liao, L.; Yang, W.; Li, Y. Corrosion non-destructive testing of loaded steel strand based on self-magnetic flux leakage effect. Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation. 2022, 37, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ding, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Xia, R.; Zhou, J. Experimental analysis of the magnetic leakage detection of a corroded steel strand due to vibration. Sensors. 2023, 23, 7130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branko, G. Concise historic overview of strain sensors used in the monitoring of civil structures: the first one hundred years. Sensors. 2022, 22, 2397–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.; Liu, W.; Fu, S. Recent progress of fiber-optic sensors for the structural health monitoring of civil infrastructure. Sensors. 2020, 20, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Hong, C.; Chen, X.; Luo, G.; Dong, S. Comparative analysis of anchor cables in pullout tests using distributed fiber optic sensors. Canadian Geotechnical Journal. 2023, 60, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezzi, L.; Fabbian, N.; Schenato, L.; Scala, A.; Cola, S. Distributed optical fiber-based monitoring of smart passive anchors for soil stabilization. Procedia Structural Integrity. 2024, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Li, C.; Luo, B.; Tang, P. Force monitoring in steel-strand anchor cables using quasi-distributed embedded FBG sensors. Construction and Building Materials. 2024, 438, 137192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Feng, Y. Latest application progress and prospect analysis of permanent magnet materials. China Energy and Environmental Protection. 2019, 41, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Coey, J. Perspective and prospects for rare earth permanent magnets. Engineering. 2020, 6, 119–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishanth, F.; Verdeghem, J.; Severson, E. A review of axial flux permanent magnet machine technology. IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications. 2023, 59, 3920–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Duan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, B.; Li, C.; Kang, Y. A flexible permanent magnetic field perturbation testing probe based on through-slot flexible magnetic sheet. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical. 2024, 366, 114899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Transport of the People's Republic of China. Technical specifications for construction of highway bridges and culverts(JTG/T3650-2020), China communication press, Beijing,China,2020;70-80.

| Design load /kN | Cycle1 | Cycle2 | Cycle3 | Cycle4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loading | Unloading | Loading | Unloading | Loading | Unloading | Loading | Unloading | |

| 100 | A-1-1 | A-1-2 | A-2-1 | A-2-2 | A-3-1 | A-3-2 | A-4-1 | A-4-2 |

| 120 | B-1-1 | B-1-2 | B-2-1 | B-2-2 | B-3-1 | B-3-2 | B-4-1 | B-4-2 |

| 140 | C-1-1 | C-1-2 | A-2-2 | A-2-3 | C-3-1 | C-3-2 | C-4-1 | C-4-2 |

| 160 | D-1-1 | D-1-2 | B-2-2 | B-2-3 | D-3-1 | D-3-2 | D-4-1 | D-4-2 |

| Working condition |

Bz/mT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0kN | 20 kN | 40 kN | 60 kN | 80 kN | 100 kN | |

| A# | 30.184 | 30.059 | 29.997 | 29.930 | 29.865 | 29.810 |

| B# | 30.186 | 30.064 | 30.002 | 29.938 | 29.880 | 29.838 |

| C# | 30.185 | 30.060 | 30.001 | 29.951 | 29.897 | 29.846 |

| D# | 30.183 | 30.050 | 29.992 | 29.922 | 29.860 | 29.794 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).