Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

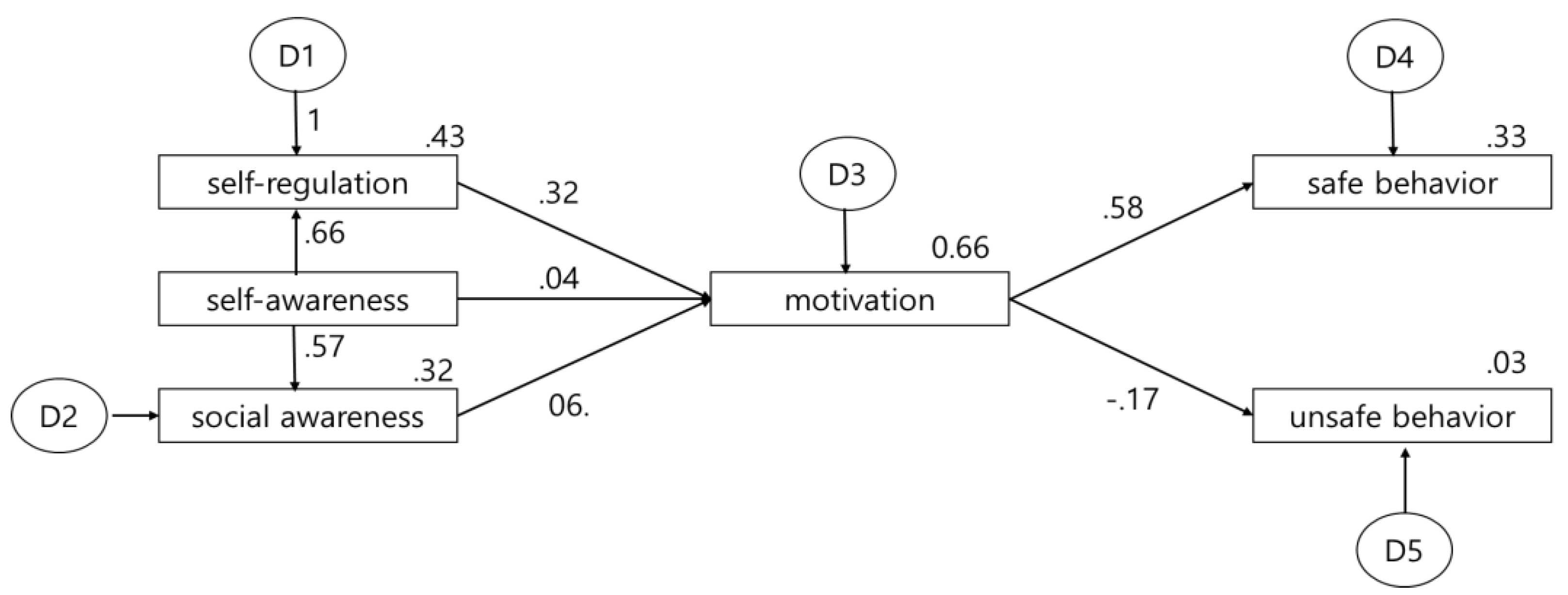

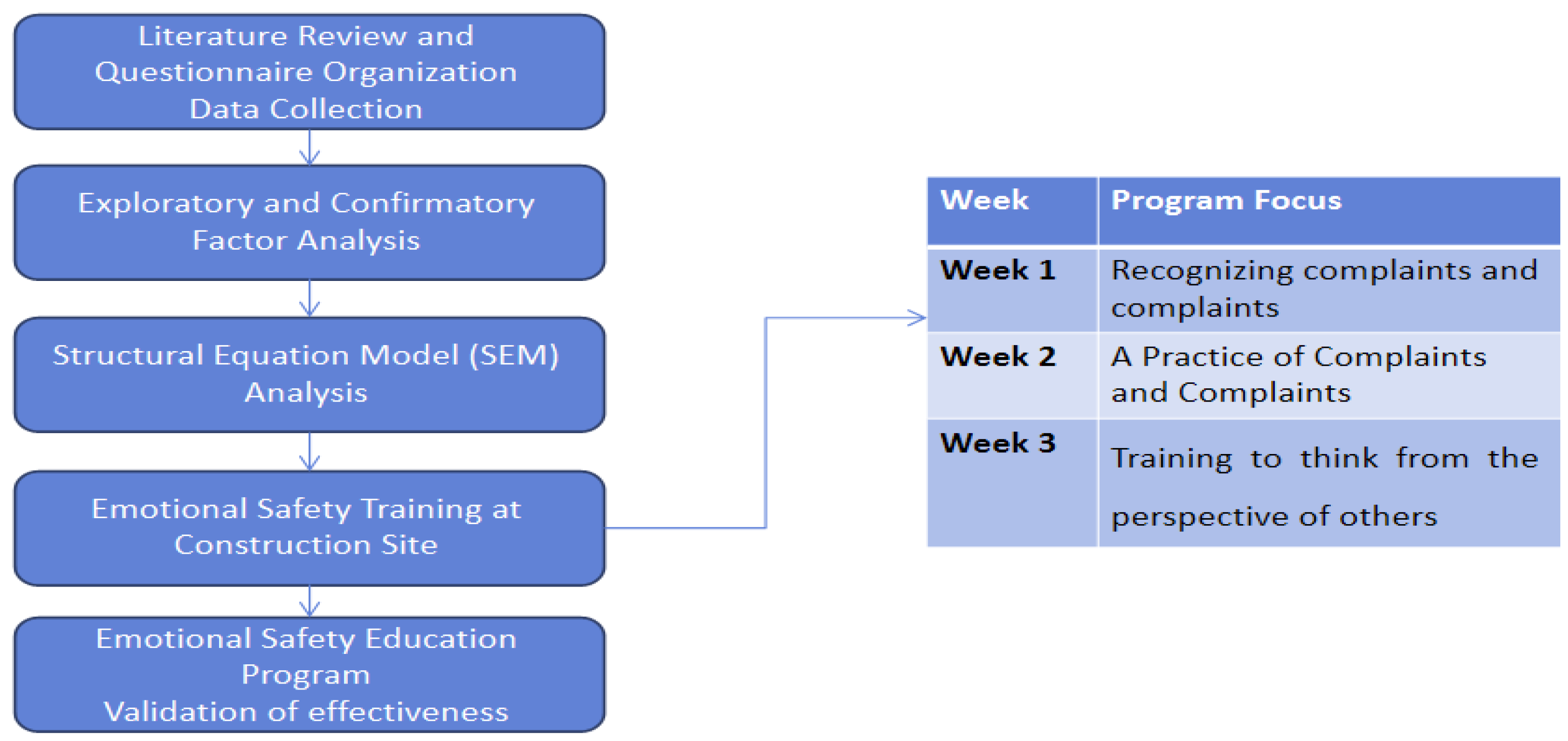

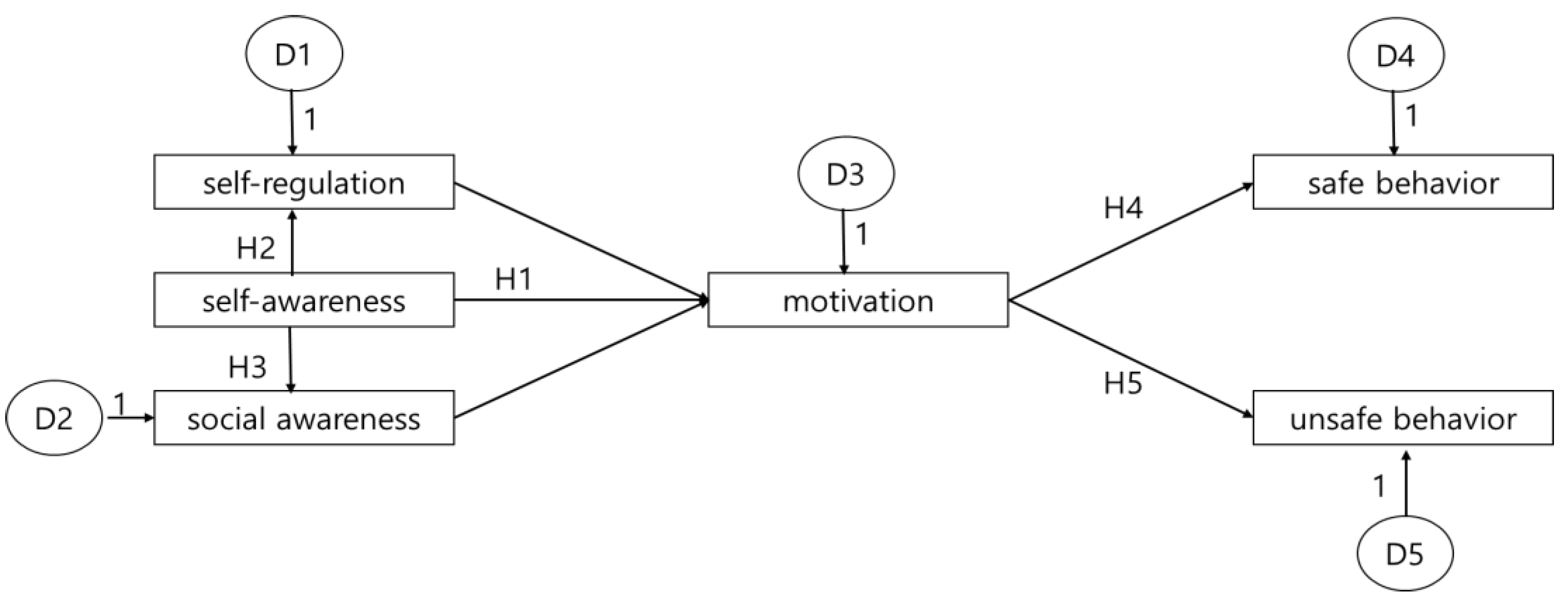

In high-risk environments such as construction sites, the integration of emotional intelligence (EI) training into safety management systems offers a promising strategy for enhancing safety performance. While existing research has predominantly focused on the leadership aspects of EI, there is a notable paucity of studies that empirically examine the subcomponents of EI, their specific effects on safety performance, or changes before and after an EI training program. This study addresses these gaps by investigating how the sub-factors of emotional intelligence—self-awareness, self-regulation, and social awareness—impact safety behavior, with motivation serving as a mediating variable. A theoretical framework was developed to model the pathway linking emotional intelligence sub-factors to safety behavior through motivation. This pathway, “emotional intelligence sub-factors → motivation → safety behavior,” was tested using path analysis to evaluate both direct and indirect effects on safety performance. The results revealed that self-awareness does not exert a direct influence on motivation; however, it has a significant indirect effect mediated by self-regulation and social awareness. Furthermore, the implementation of an emotional intelligence-based training program resulted in significant improvements across key dimensions, including emotion regulation (36.75%), impulse control (37.53%), and cause analysis (38.32%). These findings provide robust evidence that EI training fosters behavioral changes, as demonstrated by measurable differences in pre- and post-training outcomes, thereby contributing meaningfully to the enhancement of safety management systems. This study underscores the strategic value of emotional intelligence as a psychological intervention that complements conventional, technology-driven safety measures. By cultivating EI competencies, construction organizations can not only address unsafe behaviors but also create a proactive and safer working environment, ultimately elevating safety performance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Objectives

2. Literature Review

2.1. Review of Previous Studies on Emotional Factors

2.2. Components of Emotional Intelligence and Their Application to Construction Sites

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Design and Instrument Reliability

4. Results of the Study

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Emotional Subfactors and Safety. Results of Path Analysis between Unsafe Behaviors

| Division | Self-awareness | Self-regulation | Social awareness | Motivation |

| Self-awareness | .657*** (.657***,000) |

|||

| Social-awareness | .569*** (.569***,000) |

|||

| Motivation | .597*** (.043,555***) |

.322*** (.322***,000) |

.603** (.603***,000) |

|

| Unsafe behavior | -.099 (.000, -.099) |

-.053 (.000, -.053) |

-.100 (.000, -.100) |

-.166 (-.166, .000) |

| Safe behavior | .345*** (000,345***) |

.186** (000,186***) |

.348*** (000,348***) |

.578*** (578***, 000) |

4.3. Pre- and Post-Analysis of the Effectiveness of the Emotional Safety Education Program

| Subject | Emotional Regulation | Average in Korea: 63.5 | |||

| ER | I C | CA | Total | ||

| 1 | Pre | 16 | 19 | 20 | 55 |

| Post | 21 | 24 | 24 | 69 | |

| 2 | Pre | 22 | 21 | 24 | 67 |

| Post | 22 | 25 | 24 | 71 | |

| 3 | Pre | 22 | 26 | 22 | 70 |

| Post | 27 | 26 | 27 | 80 | |

| 4 | Pre | 21 | 19 | 28 | 68 |

| Post | 24 | 23 | 24 | 71 | |

| 5 | Pre | 17 | 19 | 21 | 57 |

| Post | 23 | 22 | 22 | 67 | |

| 6 | Pre | 19 | 21 | 21 | 61 |

| Post | 23 | 23 | 25 | 71 | |

5. Conclusions

References

- Shappell, S.A.; Wiegmann, D.A. Human error and general aviation accidents: A comprehensive, fine-grained analysis using HFACS. FAA/Civil Aerospace Medical Institute & University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. 2014. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252109608.

- Reason, J. Human Error. New York: Cambridge University Press: 1990.

- Bayram, M.; Arpat, B.; Ozkan, Y. Safety priority, safety rules, safety participation and safety behaviour: the mediating role of safety training. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2021, 28, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishdorj, S.; Ahn, C.R.; Park, M. Major Factors Influencing Safety Knowledge–Sharing Behaviors of Construction Field Workers: Worker-to-Worker Level Safety Communication. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, D.; Chen, Y. The relationship between construction workers’ emotional intelligence and safety performance. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kletz, T.A. Accident investigation: Keep asking “why?”. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 130, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, J. Human errors: A taxonomy for describing human malfunction in industrial installations. J. Occup. Accid. 1982, 4, 311–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craparo, G.; Magnano, P.; Paolillo, A.; Costantino, V. The Subjective Risk Intelligence Scale: The development of a new scale to measure a new construct. Curr. Psychol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Clarke, N. Emotional intelligence and its relationship to transformational leadership and key project manager competences. Proj. Manag. J. 2010, 41, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Blackman, A. Linking emotional intelligence to safety performance: The roles of situational awareness and safety training. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 78, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa, R.; Moros, A.; Morante, D.; Rodríguez, D.; Scavarda, A. The impact of emotional intelligence on operational effectiveness: The mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior and leadership. PLOS ONE, 2023; 18. [Google Scholar]

- Love, P.; Edwards, D.; Wood, E. Loosening the Gordian knot: The role of emotional intelligence in construction. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2010, 17, 176–187, Retrieved from www.emeraldinsight.com/0969-9988.htm. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, A.; Ashkanasy, N.; Khosravi, P. Key Attitudes: Unlocking the Relationships between Emotional Intelligence and Performance in Construction Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04020025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, H.; Serbaya, S.H.; Rizwan, A.; Saleem, M.; Maleh, Y.; Alamgir, Z. Impact of emotional intelligence on the stress and safety of construction workers' in Saudi Arabia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, D.; Chen, Y. The relationship between construction workers’ emotional intelligence and safety performance. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lubis, Y.; Lubis, F.R.A.; Syaifuddin, S.; Nasib, N. The Role of Motivation in Moderating the Impact of Emotional Intelligence, Work-Life Balance, Leadership, and Work Ethic on Employee Performance. Society 2023. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Gao, L.; Deng, X.; Fu, H. The Relationship Between Emotional Intelligence and Expatriate Performance in International Construction Projects. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2022, 15, 3825–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukah, A.S.; Akomea-Frimpong, I.; Jin, X.; Osei-Kyei, R. Emotional intelligence (EI) research in the construction industry: a review and future directions. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021.

- Alsulami, H.; Serbaya, S.H.; Rizwan, A.; Saleem, M.; Maleh, Y.; Alamgir, Z. (2021). Impact of emotional intelligence on the stress and safety of construction workers' in Saudi Arabia. Eng. Constr. Archit. Management.

- Lubis, Y.; Lubis, F.R.A.; Syaifuddin, S.; Nasib, N. The Role of Motivation in Moderating the Impact of Emotional Intelligence, Work-Life Balance, Leadership, and Work Ethic on Employee Performance. Society 2023. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, D.; Chen, Y. The relationship between construction workers’ emotional intelligence and safety performance. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bratton, V.K.; Dodd, N.G.; Brown, W. The impact of emotional intelligence on accuracy of self-awareness and leadership performance. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Kyung-Soo. The Impact of Emotional Factors and Self-Esteem on Safe and Unsafe Behaviors(Master's thesis). Graduate School of Engineering, Kyonggi University, South Korea, 2017.

- Ghoddousi, P.; Zamani, A. The effect of emotional intelligence, motivation and job burnout on safety behaviors of construction workers: a case study. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Du, H.; Wang, C. Relations between Safety Climate, Awareness, and Behavior in the Chinese Construction Industry: A Hierarchical Linear Investigation. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Septian, F.; Haryanto, B. The Effect of Safety Climate on Safety Behaviour: the Mediating Role of Safety Motivation and Safety Knowledge. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. Research. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Al-Bayati, A. Impact of Construction Safety Culture and Construction Safety Climate on Safety Behavior and Safety Motivation. Safety 2021, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, S.; Park, D. The effect of safety communication network characteristics on safety awareness and behavior in a liquefied natural gas terminal. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2019, 27, 144–159, [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10803548.2019.1568071]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Wu, C.; Wu, H. Impact of the Supervisor on Worker Safety Behavior in Construction Projects. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31, 04015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.; Liang, Q.; Olomolaiye, P. Impact of Job Stressors and Stress on the Safety Behavior and Accidents of Construction Workers. J. Manag. Eng. 2016, 32, 04015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Isha, A.; Yusop, Y. b. M.; Awan, M.I.; Naji, G. The Role of Psychological Capital and Work Engagement in Enhancing Construction Workers' Safety Behavior. Front. Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuwatwanich, K.; Al-Haadir, S.; Stewart, R. Influence of safety motivation and climate on safety behaviour and outcomes: evidence from the Saudi Arabian construction industry. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2017, 23, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey Composition | Mean | α | KMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Intelligence | (Self-Awareness)-SA (4items) | 3.62 | 0.680 | 0.941 |

| (Self-Regulation)-SR (5items) | 3.79 | 0.862 | ||

| (Motivation)-MO (4items) | 3.80 | 0.907 | ||

| (Social Awareness)-SO (3items) | 3.83 | 0.882 | ||

| (Social Skills)-SS(6items) | 3.48 | 0.934 | ||

| Safe Behavior | Safety Compliance Behavior (6 items) / Safety Habitual Behavior (6 items) |

3.97/3.50 | 0.931 | 0.911 |

| Safety Habit Behavior Integration | 3.74 | |||

| Unsafe Behavior | Violation Behavior (5 items) / Error Behavior (8 items) |

2.49/2.19 | 0.929 | |

| Unsafe Behavior Integration | 2.30 | |||

| Above 1.965 | Above 0.5 | Above 0.5 | Above 0.7 | |||||

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | Estimate | AVE | CR | |||

| C1 | <--- | SR | 1 | 0.708 | 0.61094086 | 0.88662324 | ||

| C2 | <--- | SR | 1.112 | 0.096 | 11.535 | 0.807 | ||

| C3 | <--- | SR | 1.05 | 0.094 | 11.2 | 0.782 | ||

| C4 | <--- | SR | 1.077 | 0.092 | 11.692 | 0.818 | ||

| C5 | <--- | SR | 0.991 | 0.098 | 10.128 | 0.705 | ||

| JD1 | <--- | Mo | 1 | 0.844 | 0.74784591 | 0.92221834 | ||

| JD2 | <--- | Mo | 1.022 | 0.061 | 16.76 | 0.87 | ||

| JD3 | <--- | Mo | 0.949 | 0.063 | 15.022 | 0.813 | ||

| JD4 | <--- | Mo | 1.015 | 0.063 | 15.995 | 0.845 | ||

| H2 | <--- | SO | 1 | 0.811 | 0.7289474 | 0.88961581 | ||

| H3 | <--- | SO | 1.046 | 0.069 | 15.248 | 0.879 | ||

| H4 | <--- | SO | 1.021 | 0.07 | 14.554 | 0.846 | ||

| F6 | <--- | SS | 1 | 0.825 | 0.71943426 | 0.93895039 | ||

| F5 | <--- | SS | 0.976 | 0.065 | 14.956 | 0.823 | ||

| F4 | <--- | SS | 1.067 | 0.066 | 16.158 | 0.865 | ||

| F3 | <--- | SS | 1.04 | 0.067 | 15.574 | 0.845 | ||

| F2 | <--- | SS | 0.991 | 0.065 | 15.148 | 0.83 | ||

| F1 | <--- | SS | 1.004 | 0.065 | 15.405 | 0.839 | ||

| B6 | <--- | SA | 1 | 0.801 | 0.993385058 | 0.997784868 | ||

| B5 | <--- | SA | 0.997 | 0.08 | 12.539 | 0.771 | ||

| B2 | <--- | SA | 0.941 | 0.075 | 12.606 | 0.774 | ||

| B1 | <--- | SA | 0.875 | 0.072 | 12.229 | 0.755 | ||

| Correlation coefficients | |||||

| SR | MO | SO | SS | AVE | |

| SR: Self-Regulation(r2) | 1 | 0.61094086 | |||

| MO: Motivation(r2) | 0.787(0.620)*** | 1 | 0.74784591 | ||

| SO: SocialAwareness(r2) | 0.656(0.430)*** | 0.85(0.722)*** | 1 | 0.7289474 | |

| SS: Social Skills(r2) | 0.704(0.500)*** | 0.668(0.445)*** | 0.55(0.302)*** | 1 | 0.71943426 |

| SA: Self-Awareness(r2) | 0.838(0.702)*** | 0.662(0.438)*** | 0.566((0.302)** | 0.804(0.650)*** | 0.99338505 |

| UnEstimate | Estimate | Hypothesis | ||

| Self-regulation | Self-awareness | 0.804 | 0.657*** | Adopted |

| Social-awareness | Self-awareness | 0.679 | 0.569*** | Rejected |

| Motivation | Self-awareness | 0.052 | 0.043 | Rejected |

| Motivation | Social-awareness | 0.614 | 0.603*** | Adopted |

| Motivation | Self-regulation | 0.319 | 0.322*** | Adopted |

| Safe behavior | Motivation | 0.594 | 0.578*** | Adopted |

| Unsafe behavior | Motivation | -0.188 | -0.166 | Rejected |

| Absolute Fit Index: RMR=.049, GFI.925, AGFI.802 Incremental Fit Index: NFI=.913, TLI=.855, CFI=.923 Chi-square = 59.123 ,Degrees of freedom = 8 Probability level= .000 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).