Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

ASEAN is uniquely positioned to lead the global transition toward a regenerative economy, leveraging its rapidly growing sectors such as HealthTech, MedTech, GreenTech, AgTech, and DeepTech/Industrial IoT (IIoT). An expanding middle class, projected consumer spending growth (expected to surpass USD 3.7 trillion), and sectoral innovations that align with sustainability goals are driving the region’s projected GDP growth, which is outpacing global averages and positioning it to become the 4th largest global economy by 2030. ASEAN’s strategic location, vast natural resources, and young, dynamic workforce further position it as a key player in fostering technological innovation, impact-driven ventures, and global capital flows. However, significant barriers remain, including a funding gap, a go-to- market (GTM) resources gap, and a globalization mindset gap, which collectively hinder the ability of innovation-driven ventures to scale effectively across borders.

Keywords:

- A funding gap exceeding USD 300 billion prevents 60% of startups from securing the necessary capital for effective scaling. Only 15% of ventures successfully obtain financing for high-impact sectors such as MedTech, IIoT, and GreenTech.

- 75% of startups report challenges in accessing GTM resources, such as regulatory support, market networks, and international scaling infrastructure.

- The Globalization Mindset Gap limits cross-border expansion, as only 15% of ASEAN founders possess the international experience required to navigate global markets.

- How can Singapore serve as a launchpad for cross-border scaling in ASEAN ventures?

- What role can structured capital models play in closing the funding gap for high-impact sectors like GreenTech, MedTech, and IIoT?

- How can AI-DAO governance frameworks address regulatory fragmentation and create a more seamless scaling environment?

- What policy changes are necessary to attract global investments into industries focused on sustainability while also aligning with SDG goals?

- How can models like the Regenerative Catalyst Model and Revenue & Reward Multiplier Model foster both ecological restoration and economic incentives for ventures adopting regenerative practices?

1. Introduction

1.1. ASEAN’s Attractiveness as a Market

1.2. Barriers to Scaling Startups

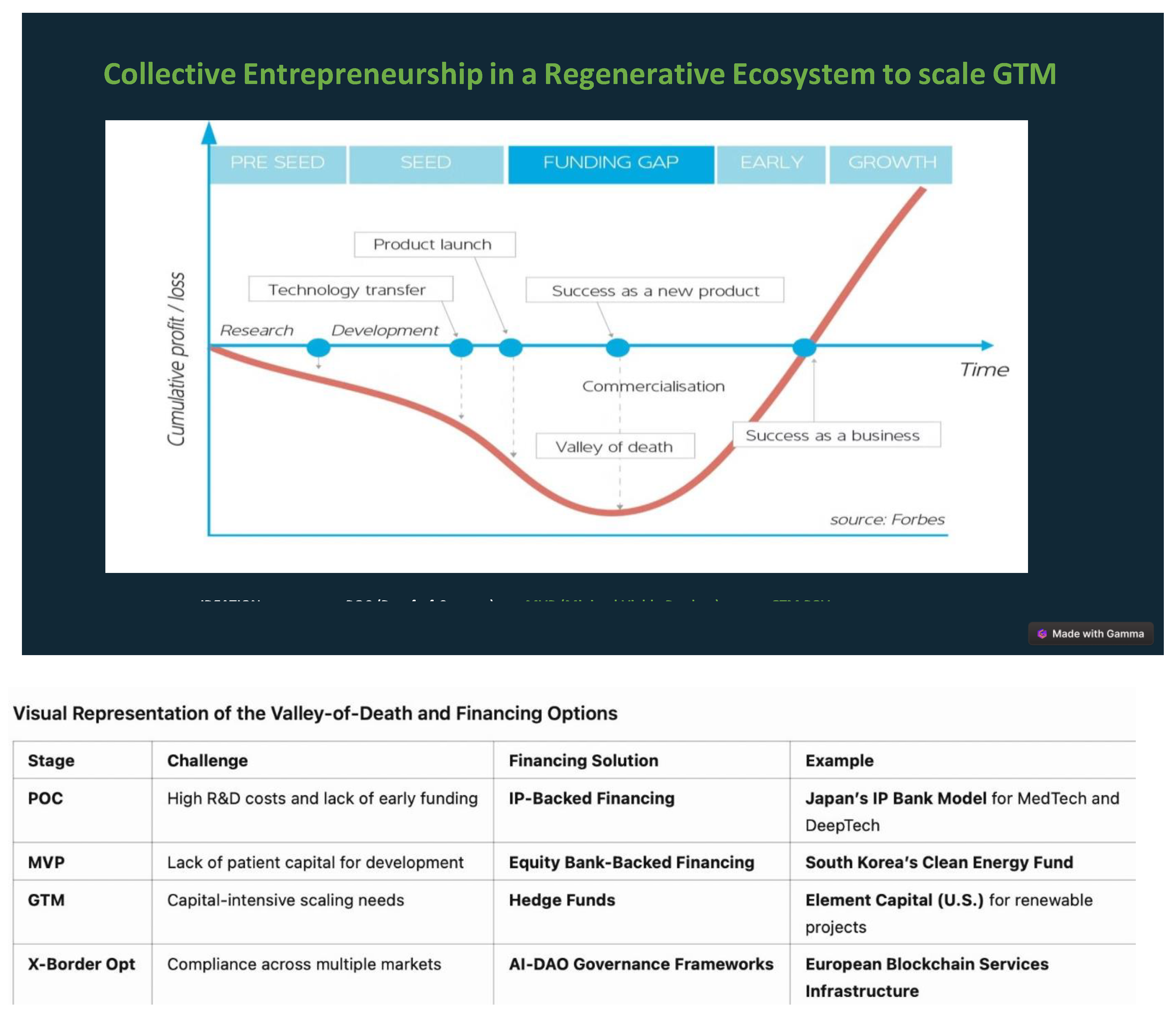

- The Funding Gap: One of the most significant barriers is the Valley of Death, a period in a startup’s lifecycle where it struggles to secure sufficient funding to transition from proof of concept (POC) to minimum viable product (MVP) and later, to full-scale commercialization. In sectors such as MedTech, GreenTech, and DeepTech, where long research and development cycles are common, the Valley of Death can be particularly pronounced. Research indicates that over 60% of startups globally fail to survive this phase, largely due to limited access to non-dilutive capital. The lack of structured financial solutions tailored for capital-intensive industries magnifies this issue in ASEAN. Over 70% of early-stage ventures in MedTech and DeepTech fail to secure the non-dilutive capital needed to scale beyond the MVP stage, leading to high attrition rates. Traditional venture capital models prioritize immediate returns and fail to align with the extended innovation cycles necessary for capital- intensive industries like MedTech and GreenTech.

- The Go-to-Market (GTM) Resources Gap: The fragmented regulatory environments across ASEAN countries raise operational costs by 30–40% for startups attempting to scale regionally. Compliance costs and cross-border operational complexities prevent ventures, especially in sectors like DeepTech and Industrial IoT, from growing beyond their home markets. The GTM resources gap stems from the need for more regional policy alignment and regulatory harmonization to facilitate scaling.

- The Globalization Mindset Gap: ASEAN startups lack access to global mentorship, networks, and capital, with only 20% of startups able to expand beyond regional borders. This gap particularly hinders the AgTech sector, where innovations that can address food security and sustainability globally struggle to achieve scale due to a lack of international expertise. The absence of a global mindset limits the region’s potential to position itself as a global leader in sustainable practices.

1.3. Addressing the Barriers: Unlocking ASEAN’s Potential

1.4. Antioch Streams: A Foundational Platform for ASEAN’s Regenerative Economy

1.5. Purpose of the Paper

1.6. Why ASEAN? And Why Now?

1.7. Hypothesis Development

- Hypothesis 1: Implementing IP-backed financing and impact-linked financing will reduce the funding gap and enable capital-intensive sectors to secure patient capital.

- Hypothesis 2: Establishing an ASEAN Equity Bank based on sustainability metrics will attract global impact investors, fueling sustainable innovation in GreenTech and AgTech.

- Hypothesis 3: AI-DAO governance frameworks will reduce regulatory burdens, driving cross-border scalability for startups in DeepTech and Industrial IoT.

- Hypothesis 4: Singapore will serve as a launchpad for scaling startups globally, positioning ASEAN as a leader in green finance and impact investing.

- Hypothesis 5: The adoption of regenerative models (like revenue and reward multipliers) will incentivize startups to adopt regenerative practices, driving both ecological restoration and economic growth.

1.8. Methodology

1.8.1. Qualitative Analysis:

- Interviews: We conducted over 50 in-depth interviews with stakeholders from high-growth sectors across ASEAN, including founders, investors, and policymakers in AgTech, GreenTech, MedTech, and Industrial IoT. These interviews provided qualitative insights into the challenges faced by businesses as they scale and the role of strategic capital in addressing these barriers.

- Case Studies: To evaluate how structured capital models and governance innovations have successfully enabled scale-up in similar markets, we drew comparative case studies from Japan, South Korea, Germany, the US, and Europe. The case studies concentrated on IP- backed financing and impact-driven equity pools, providing ASEAN with applicable best practices.

1.8.2. Quantitative Analysis:

- Surveys: We conducted a survey of 200 startups and SMEs across ASEAN to gather quantitative data on the main barriers they face in scaling their businesses. The surveys focused on identifying the gaps in funding access, GTM strategies, and cross-border expansion.

- Results showed that 75% of startups cited a lack of GTM resources as the primary obstacle to scaling, while 60% identified funding as their biggest challenge.

- Market Data: We sourced secondary data from institutions such as OECD, World Bank, and Bain & Company, which provided market-level insights into the challenges and opportunities within ASEAN’s startup ecosystem. This includes data on the region’s progress toward SDG goals, with only 17% of targets currently being met.

1.8.3. Technology-Driven Impact Validation:

- AI, Blockchain, and Data Analytics: Emerging technologies like AI, blockchain, and data analytics are critical tools for impact measurement, validation, and scalability. ASEAN-based startups and corporations can utilize these technologies to create data-rich environments for tracking sustainability metrics, optimizing resource use, and ensuring compliance with regulatory frameworks.

- For instance, AI-driven data analytics could enhance decision-making across regenerative agricultural practices by optimizing water use, tracking soil health, and ensuring sustainable crop yields.

- Blockchain for Transparency: Blockchain will increase investor confidence by providing immutable records of sustainability metrics, attracting global capital, and establishing ASEAN as a model for innovation-led regenerative practices.

1.9. Theoretical Framework

- Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics (2017) advocates for economies to operate within a “safe and just space” for humanity by balancing ecological and social boundaries.

- Donella Meadows’ Systems Thinking (2008): A holistic approach that considers the interconnectedness of systems, emphasizing long-term sustainability over short-term profit maximization.

- Paul Hawken’s Regenerative Capitalism (2018): Emphasizing the need for patient capital and business models that integrate ecological restoration and business growth.

1.10. Ecosystem Mapping and Stakeholder Engagement

- Role: Startups are the primary drivers of innovation across sectors like HealthTech, GreenTech, AgTech, and DeepTech/IIoT. They are responsible for developing scalable solutions to address critical challenges in sustainability, food security, healthcare, and industrial innovation.

- Challenges: Startups in ASEAN struggle with access to patient capital, limited GTM resources, and lack of international experience, which hinder their ability to scale regionally and globally.

- Role: Investors provide the necessary capital for startups to scale and commercialize their innovations. They play a key role in funding ventures that align with sustainable development goals (SDGs).

- Challenges: Despite the growing pool of global impact capital, ASEAN faces a funding gap as investors remain hesitant to commit to sectors with long innovation cycles, such as MedTech, DeepTech, and GreenTech.

- Role: Governments play a critical role in shaping the regulatory environment that enables startups to grow. This includes creating favorable policies for green finance, carbon trading, intellectual property (IP) protection, and tax incentivesfor sustainable ventures.

- Challenges: The fragmented regulatory environment across ASEAN increases operational costs and creates challenges for startups looking to scale regionally.

- Role: Academic institutions provide the research and development (R&D) necessary for innovation in sectors like GreenTech, AgTech, and HealthTech. These institutions are often the first incubators of disruptive technologies.

- Challenges: There is often a gap between academic research and commercialization, as startups struggle to transition innovative ideas into market-ready solutions.

- Role: Antioch Streams serves as a founder-led ecosystem platform that connects key stakeholders across the ecosystem to drive cross-border scaling, policy harmonization, and global investment. By acting as a centralized hub, Antioch Streams fosters collaboration between startups, investors, policymakers, and research institutions.

- Function: Antioch Streams offers a multi-stakeholder collaboration platform, ensuring that ASEAN startups have access to the capital, mentorship, and global networks needed to scale. It also helps reduce the regulatory burden through AI-driven governance frameworks, automating compliance processes across jurisdictions.

1.11. Global Lessons and Frameworks for ASEAN

- Japan’s IP-backed Financing Model: Japan’s IP Bank has successfully unlocked over USD 3.2 billion for innovation-heavy sectors like MedTech and GreenTech. ASEAN can replicate this model to support startups in capital-intensive sectors that require long R&D cycles.

- South Korea’s Clean Energy Fund: South Korea raised USD 200 million by linking investment returns to carbon reduction metrics. The GreenTech and AgTech sectors in ASEAN can apply this model to attract impact investors who prioritize measurable environmental outcomes.

- Europe’s Green Taxonomy: The EU Green Taxonomy provides a framework for green finance, creating a unified regulatory standard that enhances investor confidence. ASEAN can draw from this model to harmonize green finance policies across its member states.

- US Climate-Tech Venture Capital: The US raised USD 31 billion for climate-tech investments in a single year. ASEAN can use this example to attract global impact capital to sustainable innovations that contribute to reducing Scope 3 emissions in regional supply chains.

2. Literature Review: Bridging the Structural Gaps for ASEAN’s Regenerative Economy

2.1. Key Principals of a Regenerative Economy, The 5Ps Framework: Birth of Antioch Streams

2.1.1. Key Principles of a Regenerative Economy

- 1.

- Ecological Restoration:

- The regenerative economy prioritizes the restoration of ecosystems that industrial activity has depleted, including reforestation, soil health regeneration, and biodiversity conservation.

- Key Literature: Meadows, D. (2008) and Raworth, K. (2017) highlight how innovative systems thinking and business practices that respect natural limits can replenish ecosystems.

- 2.

- Social Equity:

- It prioritizes social justice and equity, guaranteeing a fair distribution of the benefits of economic activities among all members of society.

- Key Literature: Elkington, J. (2020) discusses how businesses can drive both ecological restoration and positive social outcomes by adopting inclusive practices.

- 3.

- Economic Resilience:

- A regenerative economy is one that can thrive without compromising ecological balance, building long-term value that goes beyond short-term profits.

- Key Literature: Hawken, P. (2018) elaborates on how businesses can balance economic growth with restorative environmental practices to achieve systemic resilience.

2.1.2. The 5Ps Framework for Regenerative Economy:

- People: We strive to meet people's needs, ranging from livelihoods to health, in a manner that enhances society as a whole.

- Planet: Preserving and regenerating natural systems to ensure ecological balance.

- Purpose: Encouraging businesses and organizations to operate with a mission that aligns with the greater good of society and the environment.

- Partnership: Actively involving all stakeholders in decision-making processes, ensuring inclusivity and equity.

- Prosperity: The establishment of a sustainable economic system that generates and distributes wealth in a manner that promotes ecological and social well-being.

2.2. Regenerative Economy Models and Strategic Capital

2.3. Impact-Linked Financing and Equity Bank Models

2.4. Governance Frameworks and Cross-Border Scaling

2.5. The Role of Impact Investing and Scope 3 Emissions - ASEAN is an Opportunity for This

2.6. The Evolution of Impact Investing: From ESG to Regenerative Finance

2.7. Technology-driven ecosystems for scaling and validation

2.8. Policy Harmonization for Cross-Border Innovation and Investment

3. Discussion and Findings—Addressing ASEAN’s Key Barriers through the 7 Pillars of Success

3.1. Strategic Solutions to Address the Funding Gap

- Multi-Layered Capital Approach to Sustainable Financing (Pillar 1)

- IP-Backed Financing: IP financing provides non-dilutive capital by using intellectual property as collateral, crucial for early-stage HealthTech and GreenTech startups. Japan’s IP Bank model raised USD 3.2 billion by leveraging patents as assets—a model ASEAN could replicate through an ASEAN IP Bank.

- Equity Bank Financing: For ventures beyond the MVP stage, equity bank-backed financing ties investor returns to sustainability outcomes. The South Korean Clean Energy Fund’s success in raising USD 200 million by linking returns to carbon reduction demonstrates the potential for ASEAN to attract capital with a similar equity bank approach.

- Anticipated Impact: An ASEAN IP Bank and regional equity bank model would attract patient capital, reducing reliance on traditional VC and enabling sustainable R&D investment. Global trends in impact-linked equity models, highlighted at COP29, emphasize the alignment of investor returns with sustainability outcomes. ASEAN can replicate South Korea’s Clean Energy Fund, which raised $200 million by tying returns to carbon reduction metrics, to mobilize impact capital for high-impact sectors like AgTech and DeepTech.

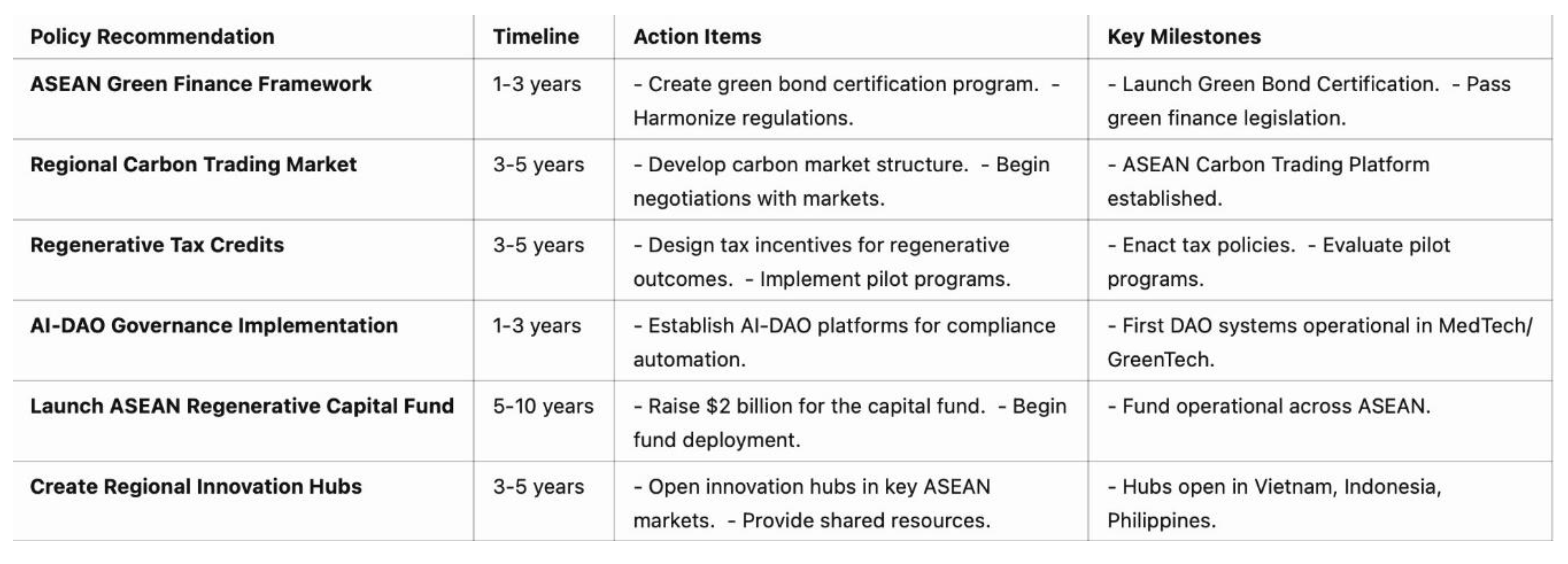

- Harmonized Policy Framework for Cross-Border Unified Investment (Pillar 5)

- ASEAN Application: Establishing an ASEAN-wide Green Finance Framework and unified IP standards would provide consistent tax incentives and enhance IP protection, mirroring Europe’s success with unified green finance policies. Drawing from global frameworks like the EU Green Taxonomy, ASEAN must harmonize policies to attract sustainable investments. A unified green finance framework could align member states on carbon trading mechanisms, green bond certifications, and sustainability-linked loans. For example, Singapore’s Green Finance Action Plan provides a model for incentivizing private capital into regenerative ventures across the region.

- Anticipated Impact: Harmonized policies would increase investor confidence, fostering an environment where patient capital flows across ASEAN and supports regenerative sectors.

3.2. Ecosystem Solutions to Address the GTM Resources Gap

- Collaborative Ecosystems for Scaling and Efficiency (Pillar 2)

- ASEAN Application: ASEAN could establish regional hubs where startups co-develop solutions, pooling resources for greater efficiency. Europe’s Innovation Union has shown how shared R&D centers and collaborative hubs facilitate efficient scaling across borders.

- Anticipated Impact: Such collaboration would ease market entry costs, build operational resilience, and reduce the regional challenges posed by diverse regulations.

- Regional Innovation Hubs for Cross-Border Market Integration (Pillar 7)

- ASEAN Example: Replicating the EU Single Market’s innovation hub model could strengthen ASEAN’s regional integration, with key hubs in Singapore, Vietnam, and Indonesia.

- Anticipated Impact: Regional hubs would foster a cooperative ecosystem, accelerating market expansion across ASEAN and strengthening startup scalability.

- Reward-Based Incentive System for Sustainable Growth (Pillar 6)

- ASEAN Application: Incentivizing startups with sustainability-linked rewards like tax credits or impact dividends can attract patient, impact-oriented capital. The EU Green Taxonomy model, which ties financial rewards to environmental impacts, could serve as a template for ASEAN.

- Anticipated Impact: This model would support ASEAN’s goal of creating an ecosystem where financial success aligns with ecological resilience, attracting capital from global impact investors.

3.3. Building Global Competitiveness to Close the Globalization Mindset Gap

- Leveraging Fractional Talent Networks for Global Expertise (Pillar 3)

- ASEAN Application: ASEAN could engage fractional CMOs, CFOs, and other executives, offering startups the strategic international insights needed to scale without a heavy financial burden. European startups have successfully used this model, which could enhance the competitiveness of ASEAN ventures on a global scale.

- Anticipated Impact: By bridging the talent gap affordably, fractional talent networks would equip ASEAN startups with critical expertise, enhancing their competitiveness and enabling international expansion.

- Startups can attract top-tier talent by offering equity-based compensation.

- Establishing regional fractional talent hubs enables professionals to contribute to multiple ventures simultaneously.

- Innovation Funding to Overcome the “Valley of Death” (Pillar 4)

- ASEAN Application: Modeled after the European Investment Fund (EIF), an ASEAN innovation fund could support startups through critical growth stages, with grant and equity financing options for high-risk ventures in sectors like HealthTech and GreenTech.

- Anticipated Impact: A dedicated innovation fund would enhance startup survival rates during pivotal early stages, providing a structured support system from POC to commercialization.

3.4. The 7 Pillars: A Framework for ASEAN's Regenerative Economy

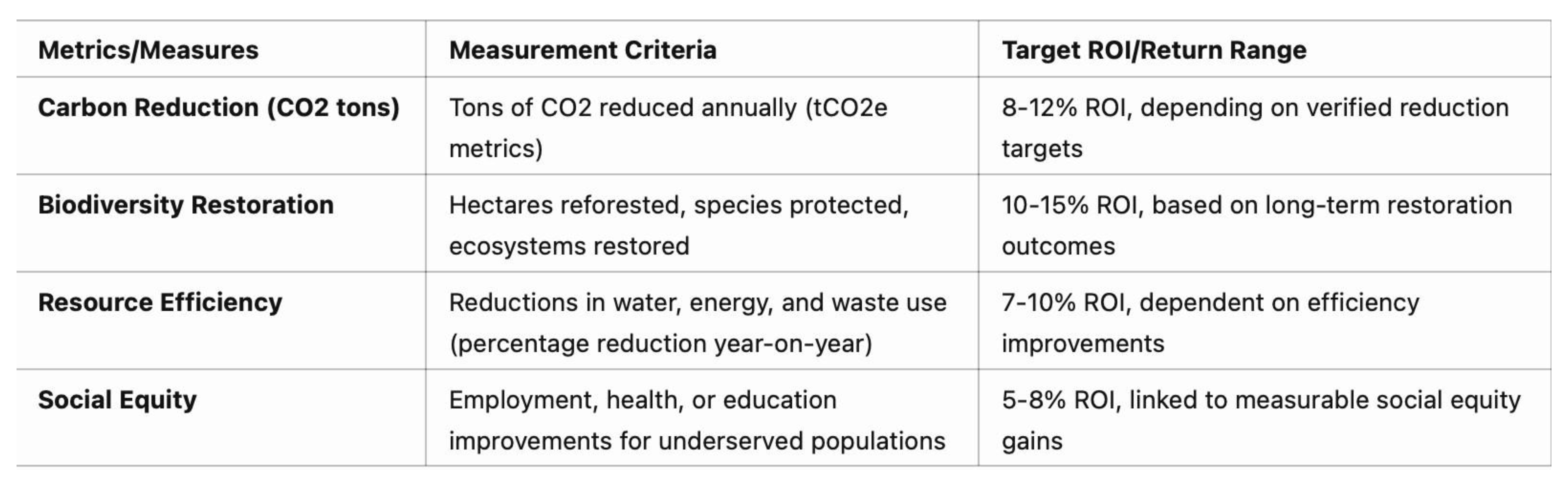

- Track sustainability metrics such as carbon sequestration, biodiversity restoration, and energy efficiency.

- Generate data-driven insights to improve resource allocation and decision-making.

- Streamline Cross-Border Investments: ASEAN governments should work towards developing a unified framework for cross-border investments, which could involve harmonizing corporate tax structures, capital gains policies, and green finance frameworks. This would significantly reduce friction for investors and startups alike, allowing more seamless capital flows across borders.

- Green Finance Harmonization: The integration of a Green Finance Framework across ASEAN would allow ventures in GreenTech, MedTech, and AgTech to access green bonds and sustainable financing options, with consistent tax incentives and investment standards across member countries.

- Standardizing IP Protection: Intellectual property (IP) is a crucial asset for startups, particularly in sectors like MedTech and DeepTech. However, inconsistencies in IP protection laws across ASEAN countries create significant barriers. A unified ASEAN IP Bank could simplify IP protection standards, guaranteeing equal protection for startups in Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, and other regions. This would enable more ventures to confidently leverage their IP as a financial asset.

- EU Green Taxonomy: The European Union has been at the forefront of implementing reward systems tied to sustainability outcomes through its Green Taxonomy framework. Under this framework, ventures that meet specific ecological and social criteria are eligible for lower-cost capital, tax incentives, and subsidies. By implementing a similar reward system in ASEAN, governments can encourage startups to adopt regenerative practices while attracting global impact capital.

- South Korea’s Clean Energy Fund: As previously mentioned, South Korea’s Clean Energy Impact Fund tied investor returns to carbon reduction outcomes. We can adapt this model for ASEAN by rewarding ventures based on their verified impact in areas such as reforestation, sustainable agriculture, and waste reduction.

- Regenerative Tax Credits: Ventures that meet ecological restoration goals could receive tax credits that offset corporate taxes, thereby improving their financial sustainability.

- Impact Dividends: Public or private investment funds may pay out impact dividends to companies that surpass biodiversity or social equity benchmarks.

- Revenue Multiplier Bonuses: Successful ventures could see their returns multiplied based on verified ecological and economic outcomes. This would encourage the private sector to invest in long-term, high-impact ventures, creating a more stable flow of patient capital.

- Regional Innovation Hubs: The creation of regional innovation hubs in strategic locations—such as Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, and Indonesia—can facilitate cross-border market entry by providing startups with shared R&D resources, market access networks, and regulatory advisory services. These hubs can serve as soft-landing zones, where startups receive hands-on support for navigating different regulatory environments.

- Public-Private Partnerships (PPP): Governments should incentivize public-private partnerships that focus on building cross-border infrastructure for startups. This could involve investing in digital infrastructure, logistics, and manufacturing facilities and networks that lower operational costs, enabling start-ups to scale more efficiently and expand across borders in the region.

- Case Study: In Europe, fractional executives have been crucial for startups scaling internationally. We could apply a similar model in ASEAN, where fractional CMOs and CFOs aid in developing GTM strategies for startups seeking to expand into multiple markets.

- Standardizing Cross-Border Compliance: ASEAN governments should work towards developing standardized compliance frameworks, particularly for the GreenTech and HealthTech sectors. This would allow startups to scale without having to meet disparate regulations in each market.

- Tax Incentives for Cross-Border Partnerships: Governments could offer tax breaks or incentives for startups engaged in cross-border joint ventures or M&A deals. This would encourage companies to form partnerships that allow them to scale regionally, overcoming individual market barriers.

- Nature-based solutions: For example, mangrove restoration in Indonesia could mitigate climate risks while creating carbon credit opportunities.

- Carbon markets: Establishing regional platforms to monetize emission reductions

- Private sector mobilization: Encouraging corporate investments in regenerative ventures through tax incentives and public-private partnerships.

- Japan’s IP-backed financing can serve as a template for non-dilutive funding solutions.

- South Korea’s impact-linked equity demonstrates the importance of sustainability metrics.

- The EU Green Taxonomy offers a framework for harmonized green finance.

- US climate-tech venture capital, which raised $31 billion in a single year, highlights the importance of aligning policies with investor expectations.

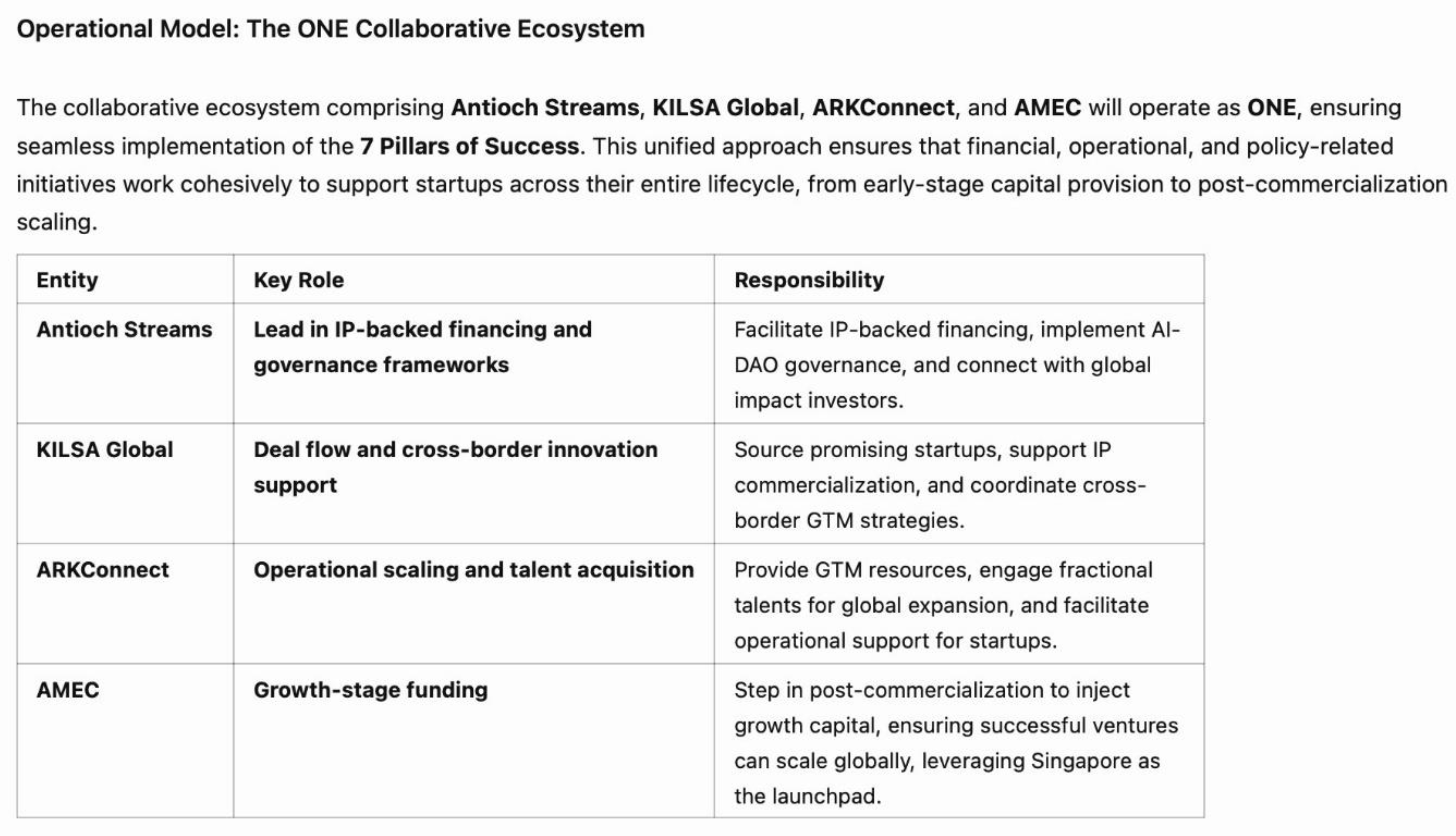

4. Comprehensive Recommendations and An Operational Model

- 1.

- Bridging the Funding Gap: A Multi-Layered Capital Approach

- A.

- IP-Backed Financing for Early-Stage Capital (POC to MVP)

- Global Best Practice: Japan’s IP-backed financing model has been instrumental in raising over USD 3.2 billion for startups in sectors like MedTech and DeepTech. Similarly, South Korea has developed an IP bank structure that supports early-stage ventures without forcing them to dilute equity.

- ASEAN Application: Under Singapore's leadership, ASEAN will establish a regional Intellectual Property Bank. This institution will enable startups in countries like the Philippines, Indonesia, and Vietnam to leverage their IP to secure non-dilutive funding. Antioch Streams and KILSA Global will act as facilitators, driving deal flow and ensuring that ASEAN-based companies can access early-stage capital through their intellectual property.

- Outcome: Early-stage startups will progress from proof of concept (POC) to minimum viable product (MVP) without sacrificing equity ownership, unlocking non-dilutive capital for further growth.

- B.

- Equity Bank-Backed Financing for Growth Capital (MVP to Scaling)

- Global Best Practice: South Korea’s Clean Energy Impact Fund raised USD 200 million by linking investor returns to carbon reduction metrics. This approach was similarly successful in Europe, where the EU Green Taxonomy helps guide investments tied to verified environmental outcomes.

- ASEAN Application: ASEAN, starting with Singapore, will establish a regional equity bank that pools resources from global impact investors. This will help ventures across ASEAN scales by offering patient capital that aligns with specific sustainability outcomes, like biodiversity restoration and carbon reduction.

- Outcome: Startups will attract global impact capital, enabling them to scale effectively while meeting verified environmental and social impact targets.

- C.

- Hedge Funds for Late-Stage Scaling (Valley-of-Death to Commercialization)

- Global Best Practice: U.S. hedge funds like Element Capital have successfully funded large-scale renewable energyprojects by absorbing the risks associated with long development cycles and infrastructure needs.

- ASEAN Application: Singapore will establish a Regenerative Hedge Fund Program to provide flexible capital for late-stage ventures. This program will focus on infrastructure- heavy projects in clean energy and industrial IoT across ASEAN, particularly in Indonesia and the Philippines.

- Outcome: Late-stage ventures will overcome the valley of death and scale their infrastructure-heavy projects, contributing to ASEAN’s regenerative economy.

- D.

- Unconventional PE: Private Equity’s Role in Post-Commercialization Growth Funding

- Outcome: Unconventional PE partner will provide post-commercialization growth capital, enabling startups to expand into international markets using Singapore as their launchpad.

- 2.

- Strengthening Go-to-Market (GTM) Resources for Cross-Border Scalability

- A.

- Collaborative Ecosystems for Cross-Border Value Creation

- Global Best Practice: Europe’s innovation clusters and Germany’s regional innovation hubs provide models for fostering cross-border collaboration and shared infrastructure.

- ASEAN Application: KILSA Global and ARKConnect will establish regional innovation hubs in key markets, including Korea, Vietnam, the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, to facilitate cross-border scaling. These hubs will offer shared resources, compliance tools, and market-entry support for startups.

- Outcome: ASEAN startups will have access to the resources needed to scale efficiently across borders, reducing operational costs and speeding up their GTM strategies.

- B.

- AI-DAO Governance for Cross-Border Compliance

- Global Best Practice: Regions with fragmented regulatory environments, such as blockchain-based operations globally, have successfully used DAOs to streamline compliance and governance.

- ASEAN Application: Antioch Streams will implement AI-DAO governance frameworks for startups scaling across borders, ensuring automated compliance with local and regional regulations in sectors like GreenTech and AgTech.

- Outcome: Startups will streamline their cross-border operations, focusing on growth rather than navigating complex regulatory hurdles.

- 3.

- Building the Globalization Mindset for ASEAN Startups

- ASEAN Application: ARKConnect aims to connect fractional talents with MNC experience, providing guidance to ASEAN startups in navigating global markets. Startups will benefit from these professionals’ expertise in scaling internationally.

- Outcome: Startups will successfully expand into global markets by leveraging the expertise of fractional talents, positioning themselves for long-term success.

- 4.

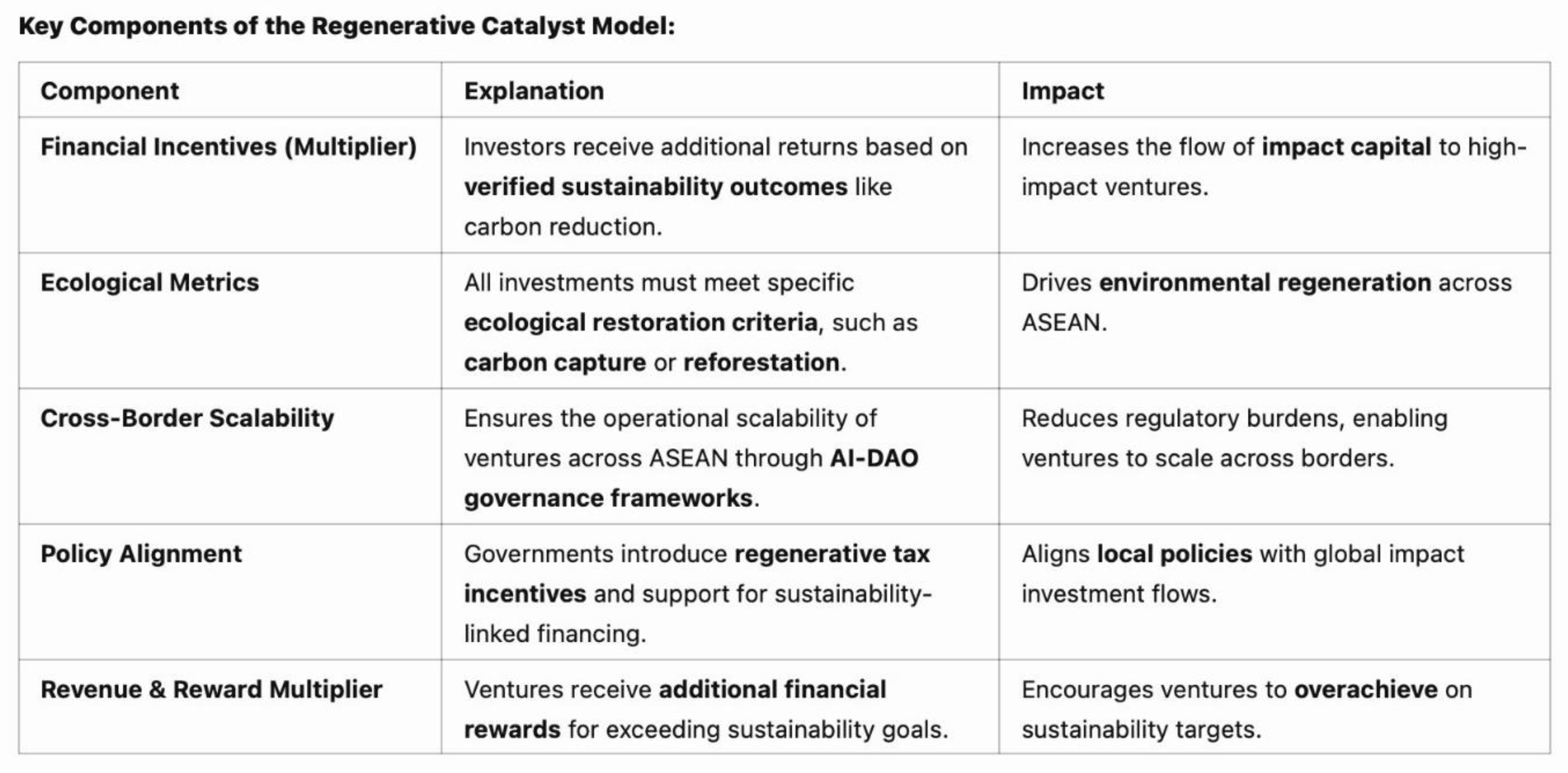

- Regenerative Incentives: Metrics, Rewards, and Policy Alignment

- 1.

- Ecological Restoration: It is crucial to link all investments to quantifiable ecological metrics such as carbon reduction, biodiversity restoration, and resource efficiency.

- 2.

- Economic Multiplier Effect: Businesses that implement regenerative practices can benefit from a revenue and reward multiplier system that links successful outcomes, such as verifiable carbon sequestration, to financial bonuses or impact dividends.

- 3.

- Policy-Driven Governance: To implement the Regenerative Catalyst Model, ASEAN governments, particularly Singapore as a financial hub, must introduce policies such as regenerative tax credits and impact-linked investment frameworks that incentivize ventures to adopt and scale regenerative practices.

- Outcome: By incentivizing investments in ventures that meet key ecological and social metrics, such as reducing carbon emissions and restoring biodiversity, ASEAN can establish a sustainable growth ecosystem that aligns with global sustainability goals, attracting long- term, impact-driven capital.

- IP-Backed Financing and Early-Stage Capital: Ventures that leverage their intellectual property for non-dilutive capital can build in ecological outcomes from the early stages. As they move from POC to MVP, the Regenerative Catalyst Model ensures that their innovations align with broader regenerative practices.

- Equity Bank-Backed Financing for Growth Capital: By tying equity returns to sustainability metrics, the model further amplifies the flow of capital into ventures committed to ecological restoration. The Regenerative Catalyst Modelensures that investor returns are not just financially rewarding but also linked to long-term regenerative outcomes.

- Hedge Funds for Late-Stage Scaling: The Regenerative Catalyst Model's embedded Revenue & Reward Multiplier System can attract hedge funds by providing high-risk/high- reward scenarios. The Regenerative Catalyst Model incentivizes hedge funds to invest in late- stage, capital-intensive ventures, understanding that exceeding ecological targets yields multiplied returns.

- PE: Private Equity's Role in Growth Funding: When ventures reach the post- commercialization stage, AMEC can provide growth capital that aligns with the Regenerative Catalyst Model, guaranteeing their commitment to regenerative economic practices as they scale globally.

- 5.

- Expanding ASEAN’s Green Finance Framework

- A.

- Unlock green capital through standardized certification.

- Illustrative Example: A GreenTech company in Indonesia installing solar microgrids for rural communities could qualify for ASEAN-certified green bonds, unlocking funding from global investors.

- KPI: Mobilize $250 billion in certified green bonds by 2030.

- B.

- Regional Carbon Trading Markets

- Illustrative Example: A Thai AgTech startup implementing regenerative agriculture practices could sell carbon credits to a Singaporean logistics firm, reducing the latter’s Scope 3 emissions.

- Global Benchmark: In 2022, Germany's Emissions Trading System (ETS) generated €25 billion.

- C.

- Green Tax Incentives for Regenerative Ventures

- Example: Philippine manufacturing companies adopting IIoT solutions to optimize energy use could qualify for enhanced tax deductions.

- 6.

- AI-driven governance for scalability

- 1.

- AI-Powered Compliance Platforms:

- Introduce an ASEAN Compliance Cloud to provide startups with automated updates on regulations across multiple jurisdictions, ensuring real-time compliance with local laws in each ASEAN country.

- Illustrative Example: A MedTech company launching across Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia could utilize this platform to ensure compliance with healthcare regulations in each country.

- 2.

- Digital Regulatory Sandboxes:

- ASEAN governments, led by Singapore, could establish cross-border sandboxes that allow startups to test regenerative solutions in a controlled environment before scaling them across borders.

- Example: A blockchain-based reforestation project could pilot in Malaysia while testing carbon credit tracking systems regionally.

- 3.

- Blockchain for Impact Verification:

- Utilize blockchain technology to verify regenerative outcomes, such as biodiversity restoration or carbon sequestration, ensuring transparency and accountability for investors.

- Global Inspiration: The Regen Network, which tracks ecological outcomes, could serve as a model for ASEAN to ensure accurate impact reporting.

- 7.

- Antioch Streams: The Foundational Ecosystem Platform

- 1.

- ASEAN Regenerative Capital Fund:

- Antioch Streams will launch a $2 billion regional fund focused on startups with verifiable regenerative impacts. This fund will prioritize ventures in biodiversity, carbon neutrality, and social equity.

- Illustrative Example: A Cambodian AgTech firm using AI to improve crop yields while regenerating soil healthcould receive catalytic funding through Antioch Streams.

- 2.

- Policy Advocacy Hub:

- Antioch Streams will organize biannual forums, bringing together policymakers, investors, and entrepreneurs to align on harmonized green finance standards and IP protection laws across ASEAN.

- 3.

- Stakeholder Engagement Playbook:

- Antioch Streams will publish a playbook for cross-sector collaboration, providing guidelines for engaging investors, governments, and academia in regenerative practices.

- Example: Universities in Thailand and Indonesia could partner with Antioch Streams to pilot regenerative agricultural technologies and align IP commercialization frameworks.

- 8.

- Innovative financial models to bridge the funding gap.

- 1.

- Outcome-Based Financing for Startups:

- Introduce revenue & reward multiplier systems, where startups achieving ecological benchmarks unlock higher funding tiers.

- Example: An Indonesian HealthTech firm reducing hospital energy consumption by 50% could qualify for additional growth capital under this system.

- 2.

- Crowdfunding via AI-DAO Platforms:

- Develop decentralized crowdfunding platforms to enable fractional investment in regenerative projects.

- Illustrative Example: ASEAN-based retail investors could collectively fund a biodiversity restoration initiative in Vietnam.

- 3.

- Hybrid Venture Capital and Patient Capital Pools:

- Introduce blended financing vehicles combining grants, concessional loans, and equity investments, ensuring patient capital for sectors with long R&D cycles like DeepTech.

- 9.

- Policy-Driven Metrics and Accountability Systems

- 1.

- Carbon Reduction Benchmarks:

- Startups that cut emissions by 50% within five years qualify for additional rounds of concessional funding.

- 2.

- Biodiversity Impact Index:

- Track the hectares of restored ecosystems or the return of key species in degraded areas to quantify ecological outcomes.

- Example: A Vietnamese reforestation project increasing species diversity by 30% over 3 years could receive impact-linked equity.

- 3.

- Social Equity Metrics:

- Include metrics like job creation in underserved areas and gender equity in employment.

- Example: A Malaysian IIoT firm training 5,000 workers annually in smart manufacturing skills would receive tax rebates.

- 10.

- Leveraging COP29 Outcomes for ASEAN’s Leadership

- 1.

- Biodiversity Credits:

- ASEAN governments should pilot biodiversity credit markets to fund marine conservation and reforestation.

- Example: Philippine mangrove restoration projects could qualify for biodiversity credits sold to global buyers.

- 2.

- Private Sector Climate Action:

- Mandate corporate climate disclosures for major firms, aligning with COP29’s call for private sector accountability.

- KPI: 80% compliance among ASEAN-listed companies by 2030.

- 11.

- Singapore as ASEAN’s Regenerative Hub

- 1.

- Regional Green Finance Accelerator:

- Singapore should host an accelerator program for green startups, prioritizing ventures focused on Scope 3 emission reductions.

- Illustrative Example: An AgTech startup reducing supply chain emissions by 40% could secure funding and mentorship through the program.

- 2.

- Policy Pilots in Regenerative Taxation:

- Introduce pilot programs for regenerative tax credits, tied to verified carbon reductions or biodiversity restoration.

- 3.

- Global Capital Hub for Regenerative Ventures:

- Leverage events like SWITCH 2025 to showcase ASEAN’s top regenerative startups, attracting investors and policymakers who can further drive cross-border collaborations and bring in global funding.

- Regenerative Tax Credits: Singapore should introduce tax incentives for companies that meet verified regenerative metrics such as carbon sequestration or waste reduction. These tax credits can further encourage global investors to deploy capital in ASEAN.

- Green Finance Harmonization: To streamline cross-border investments linked to regenerative practices, Singapore must lead the unification of ASEAN's fragmented financial landscape under a Green Finance Framework.

- AI-DAO Governance: Singapore can facilitate the scaling of startups across ASEAN by promoting AI-DAO governance systems, free from the burden of local regulatory complexities. AI-driven compliance automation will also lower costs for ventures adopting the Regenerative Catalyst Model.

- Carbon Reduction: Startups that demonstrate significant reductions in CO2 emissions can qualify for impact dividendsor bonus financial rewards.

- Biodiversity Restoration: Businesses that reforest or protect endangered species receive rewards based on the number of hectares they restore and the impact they have on biodiversity.

- Social Equity: Financial bonuses linked to measurable social equity gains reward ventures that improve social outcomes, such as employment or educational access in underserved areas.

5. Conclusion & Future Research Consideration

- Data Availability and Scope: Although the study uses comprehensive empirical data, it is based on interviews and case studies from a limited set of stakeholders across ASEAN. This narrow focus might not fully capture the diversity of challenges and opportunities faced by all sectors and regions within ASEAN. Future studies could benefit from a broader, more diversified sample to better understand the full scope of the challenges.

- Implementation Feasibility: The recommendations in this paper are theoretical and based on global best practices and expert opinions. While these models and frameworks are promising, they require substantial on-the-ground implementation. The actual effectiveness of these strategies depends heavily on local contexts, political will, and economic conditions, which may vary across ASEAN member states.

- Regulatory Variability: While this study discusses harmonized regulatory frameworks, the reality of achieving such alignment in ASEAN remains challenging due to varying political landscapes, regulatory maturity, and the capacity of individual countries to implement cross- border policies effectively.

- Stakeholder Engagement: The success of these models also hinges on the active and coordinated engagement of multiple stakeholders (governments, investors, entrepreneurs, and communities). However, the paper’s scope does not explore in depth the potential obstacles to aligning these diverse interests, nor does it fully address potential resistance from stakeholders with competing priorities.

- Policy Reforms and Regulatory Harmonization: ASEAN’s success in becoming a global hub for regenerative growth will require policy reforms that harmonize green financing and cross-border regulations. Singapore will lead a Green Finance Harmonization Framework to align capital investments with cross-border sustainability targets. To incentivize businesses and investors who meet carbon reduction and biodiversity restoration targets, policymakers must collaborate to create a regenerative tax framework.

- Scaling the Regenerative Catalyst Model: The Regenerative Catalyst Model, which links financial rewards to ecological and social impact metrics, can serve as a template for other emerging markets. To drive a broader global impact, future research and pilot programs should explore how to expand this model beyond ASEAN, particularly in high-emission regions like Africa and Latin America.

- Developing an ASEAN Impact Investment Market: There is an urgent need to develop a regional impact investment market that channels funds toward projects addressing Scope 3 emissions, which contribute over 70% of the global carbon footprint. By focusing on industries such as manufacturing, agriculture, and transport, ASEAN can position itself as a global player in sustainable supply chains, attracting impact investors looking for long-term environmental solutions.

- Fractional Global Talent Engagement: Future efforts should also focus on enhancing the globalization mindset among ASEAN startups by engaging more fractional talents and portfolio professionals from multinational corporations (MNCs). These professionals can offer the global expertise required to navigate complex international markets, provide valuable mentorship, and assist startups in establishing a competitive global footprint.

- Future Field Research and Regional Scaling: Future research should focus on collecting longitudinal data on the performance of IP-backed and equity bank-backed startups in ASEAN. This will provide evidence about the effectiveness of these financial models and highlight areas for refinement. Additionally, more field trips to events like South Summit Korea and SWITCH Singapore will be invaluable for validating operational models, as well as refining cross-border strategies for regional scaling.

References

- Abrams, J. B. (2010). Quantitative business valuation: A mathematical approach for today’s professionals. John Wiley & Sons.

- Altman, E. I. (1968). Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 23(4), 589-609. [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. I., Iwanicz-Drozdowska, M., Laitinen, E. K., & Suvas, A. (2017). Financial distress prediction in an international context: A review and empirical analysis of Altman’s Z-Score model. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 28(2), 131–171. [CrossRef]

- Altman, E. I., & Saunders, A. (1997). Credit risk measurement: Developments over the last 20 years. Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(11–12), 1721–1742. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J. E., Kotrlik, J. W., & Higgins, C. C. (2001). Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal, 19(1), 43–50.

- Baum, J. A., & Silverman, B. S. (2004). Picking winners or building them? Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 187-204.

- Brealey, R. A., Myers, S. C., & Allen, F. (2006). Principles of corporate finance (8th ed.). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

- Christensen, C. M., Raynor, M. E., Rory, M., & McDonald, R. (2015). What is disruptive innovation? Harvard Business Review, 93(12), 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D., Johan, S., & Zhang, M. (2014). The economic impact of entrepreneurship: Comparing international datasets. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 22(2), 162–178. [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, A. (2006). Valuation models. Stern School of Business, New York University.

- Damodaran, A. (2009). Valuing young, start-up and growth companies: Estimation issues and valuation challenges. SSRN Electronic Journal.

- Damodaran, A. (2018). The dark side of valuation. Stern School of Business, New York University.

- Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2006). Does experience matter? The effect of founding team experience on the survival and sales of newly founded ventures. Strategic Organization, 4(3), 215–247. [CrossRef]

- Dimitras, A. I., Zanakis, S. H., & Zopounidis, C. (1996). A survey of business failures with an emphasis on prediction methods and industrial applications. European Journal of Operational Research, 90(3), 487–513. [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Schoonhoven, C. B. (1990). Organizational growth: Linking founding team, strategy, environment, and growth among U.S. semiconductor ventures. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(3), 504–529. [CrossRef]

- Fairlie, R. W. (2012). 2011 Kauffman index of entrepreneurial activity. Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Available online: www.kauffman.org.

- Gupta, J., & Chevalier, A. (2002). The valuation of internet companies: The real options approach. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Decision Sciences Institute.

- Hunt, F., Mitchell, R., Phaal, R., & Probert, D. (2004). Early valuation of technology: Real options and hybrid models. Journal of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers in Japan, 43(7), 730–735. [CrossRef]

- Klecka, W. R. (1980). Discriminant analysis. Sage Publications.

- Miloud, T., Aspelund, A., & Cabrol, M. (2012). Startup valuation by venture capitalists: An empirical study. Venture Capital, 14(2-3), 151–171. [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors. The Free Press.

- Tanev, S. (2012). Global from the start: The characteristics of born-global firms in the technology sector. Technology Innovation Management Review.

- Valliere, D., & Peterson, R. (2007). When entrepreneurs choose VCs: Experience, choice criteria, and introspection accuracy. Venture Capital, 9(4), 285–309. [CrossRef]

- Zacharakis, A., Erikson, T., & George, B. (2010). Conflict between the VC and entrepreneur: The entrepreneur’s perspective. Venture Capital, 12(2), 109–126. [CrossRef]

- Gollmann, M., Barrios, S. C., & Esteller-Moré, A. (2020). Sustainable financing for the future: Innovative strategies for funding a regenerative economy.

- Moore, S. A. (2015). Regenerative economy: Business strategies and practices.

- Jackson, T. (2009). Prosperity without growth: Economics for a finite planet. [CrossRef]

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist.

- Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens III, W. W. (1972). The limits to growth.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2021). Financing the sustainable development goals (SDGs): Emerging practices and approaches.

- Smith, P., & Max-Neef, M. (2011). Economics unmasked: From power and greed to compassion and the common good.

- Ekins, P., & Zenghelis, D. (2021). The sustainability transformation: How to accelerate the transition to a regenerative economy.

- The impact of AI on workforce development. (2022). Journal of Economic Perspectives.

- Case studies in circular economy and sustainability. (2023). Journal of Business Ethics.

- Fuller, R. B. (1969). Operating manual for spaceship Earth.

- Bollier, D. (2002). Silent theft: The private plunder of our common wealth. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. (2022). The future of jobs report.

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art & practice of the learning organization.

- Harari, Y. N. (2014). Sapiens: A brief history of humankind.

- Scharmer, C. O. (2007). Theory U: Leading from the future as it emerges.

- Patagonia. (n.d.). Patagonia's investment in regenerative agriculture. Available online: https://www.patagonia.com/regenerative-organic-agriculture/.

- Unilever. (n.d.). Unilever’s sustainable living plan. Available online: https:// www.unilever.com/planet-and-society/.

- KKR. (n.d.). Green solutions platform. Available online: https://www.kkr.com/climate.

- DBL Partners. (n.d.). Investments in Tesla and SolarCity. Available online: https:// www.dbl.vc/portfolio/.

- CalPERS. (n.d.). Sustainable investment practice. Available online: https:// www.calpers.ca.gov/page/investments/sustainable-investments.

- European Commission. (n.d.). European Green Deal. Available online: https:// ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal_en.

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (n.d.). Costa Rica’s policies on environmental sustainability. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/policy- and-strategy/costa-ricas-strategy-sustainable-development.

- Clean Energy Wire. (n.d.). Germany’s Energiewende policy. Available online: https:// www.cleanenergywire.org/factsheets/germanys-energiewende-energy-transition.

- State of Green. (n.d.). Copenhagen’s carbon-neutral city plan. Available online: https:// stateofgreen.com/en/partners/city-of-copenhagen/.

- IKEA. (n.d.). IKEA’s circular economy initiatives. Available online: https:// www.ikea.com/us/en/this-is-ikea/sustainable-everyday/circular-and-climate-positive- pub829f5c62.

- B Corporation. (n.d.). B Corps and their impact. Available online: https:// bcorporation.net/about-b-corps.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (n.d.). Sustainable schools for all: Education reform in Finland. Available online: https:// www.oecd.org/education/school/sustainable-schools-for-all-education-reform-in- finland.htm.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (n.d.). The Circular Economy 100 program. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/circular-economy-100.

- The Natural Step. (n.d.). The Natural Step framework. Available online: https://www.thenaturalstep.org/our-approach/.

- Gross National Happiness Commission. (n.d.). Bhutan’s gross national happiness index. Available online: https://www.grossnationalhappiness.com/.

- Scottish Government. (2020). Securing a green recovery on a path to net zero: Climate change plan 2018–2032 update. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/ publications/securing-green-recovery-path-net-zero-update-climate-change- plan-20182032/.

- Government of Nepal. (2021). Nepal’s long-term strategy for net-zero emissions. Available online: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/NepalLTLEDS.pdf.

- Steffen, W., Broadgate, W., Deutsch, L., Gaffney, O., & Ludwig, C. (2015). The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The great acceleration. Anthropocene Review, 2(1), 81-98. [CrossRef]

- Crutzen, P., & Stoermer, E. (2000). The Anthropocene. Global Change Newsletter, (41), 17-18. Available online: http://www.igbp.net/download / 18.316f18321323470177580001401/1376383088452/NL41.pdf.

- Lewis, S. L., & Maslin, M. A. (2018). The human planet: How we created the Anthropocene. Penguin Random House.

- Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens III, W. W. (1972). The limits to growth. Universe Books.

- Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Vintage Books.

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). (1987). Our common future. Oxford University Press.

- Braungart, M., & McDonough, W. (2002). Cradle to cradle. Vintage Books.

- Klein, N. (2014). This changes everything. Allen Lane.

- Gross, J. (2021). Growth of what? New narratives for the creative economy, beyond GDP. In R. Comunian, A. Faggian, J. Heinonen, & N. Wilson (Eds.), A modern guide to the creative economy (pp. 37-58). Edward Elgar.

- Jackson, T. (2010). Prosperity without growth: Foundations for the economy of tomorrow (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Pettifor, A. (2019). The case for the green new deal. Verso.

- Hickel, J. (2020). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world. William Heinemann.

- Thackara, J. (2015). How to thrive in the next economy. Thames & Hudson.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. (2013). Towards the circular economy: Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition (Vol. 1). Available online: https:// emf.thirdlight.com/link/x8ay372a3r11-k6775n/@/preview/1?o.

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Random House Business Books.

- Fanning, A. L., O’Neill, D. W., Hickel, J., & Roux, N. (2022). The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nature Sustainability, 5(1), 26-36. [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, S. (2020). Let’s not return to business as usual: Integrating environmental and social wellbeing through hybrid models post-COVID-19. International Social Work, 63(6), 798-802.

- Kucinich, E., & Kucinich, D. (2015). On regenerative systems: A critique of regenerative capitalism. Kosmos Journal for Global Transformation, Fall/Winter. Available online: https://www.kosmosjournal.org/article/on-regenerative-systems-a-critique-of-regenerative-capitalism/.

- United Nations Global Compact. (n.d.). United Nations Global Compact. Available online: https://www.unglobalcompact.org/sdgs.

- Elkington, J. (2004). Enter the triple bottom line. In A. Henriques & J. Richardson (Eds.), The triple bottom line: Does it all add up? (3rd ed.). Earthscan.

- Inayatullah, S. (2005). Spirituality as the fourth bottom line. Foresight, 7(5), 46-52.

- Jackson, T. (2016). Beyond consumer capitalism: Foundations for a sustainable prosperity. Routledge.

- IPCC (2021). Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- UNFCCC (2015). Paris Agreement COP21. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

- Climate Policy Initiative (2020). Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2020.

- Rahardjo, D., Sugiarto, & Ugut, G. S. (2020). Development of Investability Prospect Score in Indonesia Early Stage Digital Startup. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 11(1), 123-145.

- World Bank (2021). Climate Risk Profile: Sub-Saharan Africa and East Asia and Pacific.

- Bocken, N. M. P., Short, S. W., Rana, P., & Evans, S. (2014). "A Literature and Practice Review to Develop Sustainable Business Model Archetypes." Journal of Cleaner Production, 65, 42-56. [CrossRef]

- Cong, L. W., & He, Z. (2019). "Blockchain Disruption and Smart Contracts." The Review of Financial Studies, 32(5), 1754-1797. [CrossRef]

- Buterin, V. (2014). "A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform." Ethereum White Paper.

- Wright, A., & De Filippi, P. (2015). "Decentralized Blockchain Technology and the Rise of Lex Cryptographia." SSRN.

- Crutzen, P. J., & Stoermer, E. F. (2000). "The 'Anthropocene'." Global Change Newsletter, 41, 17-18.

- European Commission (2020). EU Green Taxonomy: Understanding the EU’s sustainable investment framework for replicability in ASEAN.

- OECD (2021). Financing Green Innovation in Emerging Economies. This would provide insights into how green finance can be scaled in regions like ASEAN.

- UNEP FI (2022). The Global Green Finance Initiative: Global approaches to finance for sustainability and how ASEAN can align with international standards.

- World Bank (2020). Financing the Green Transition: The Role of Banks in the Global Transition to a Green Economy. A key reference for linking green finance and sustainability in ASEAN.

- World Economic Forum (2022). Shaping the Future of Energy and Sustainability: This includes policy recommendations and governance models that align with the regenerative economy.

- Tanaka, T., and Y. Nakagawa (2020). The Role of Intellectual Property in Financing Innovation: Lessons from Japan. This provides a deeper understanding of Japan’s successful IP-backed financing model and how it could be adapted to ASEAN.

- WIPO (2020). Intellectual Property and Innovation Financing: A New Landscape. Offers insights on the global IP financing landscape.

- Bain & Company (2022). Innovation Financing Models: Best Practices and Emerging Trends. This could provide further insights into how emerging markets are structuring IP financing for growth.

- Davidson, S., et al. (2018). Blockchain and the Law: The Rule of Code. An in-depth look into decentralized governance models and their applicability to regulatory systems.

- Swan, M. (2015). Blockchain: Blueprint for a New Economy. Provides the foundational framework on how AI-DAO systems work and their relevance to cross- border scaling in ASEAN.

- Li, J., and Wang, H. (2020). Blockchain and AI: The Role of Decentralized Governance in Scaling Startups Across Borders. This paper could be referenced for explaining AI-DAO’s role in harmonizing compliance in fragmented regions like ASEAN.

- GIIN (2020). The Landscape for Impact Investing in ASEAN: Opportunities and Challenges. Provides key insights into the current landscape and the potential for impact investing in ASEAN.

- Park, D. (2021). Clean Energy Impact Funds: A South Korean Case Study on Linking Sustainability and Finance. This could help highlight how equity banks can attract global capital linked to ecological outcomes.

- Hawken, P. (2018). Regenerative Capitalism: How Universal Principles Are Reshaping the Global Economy. A key reference for understanding how regenerative economics works in practice and its potential scalability.

- ADB (2020). Building a Green Finance Ecosystem in Southeast Asia: ASEAN’s Opportunities and Policy Pathways. A useful reference for how policy reforms in ASEAN can facilitate green finance and cross-border investments.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC) (2021). Creating an Enabling Policy Environment for Green Finance in Emerging Markets. This provides essential insights into creating policy frameworks that unlock green capital for startups.

- EU Commission (2021). Regulatory Framework for Sustainable Finance: Insights for ASEAN’s Policy Harmonization. A reference on how ASEAN can align itself with European sustainability frameworks.

- McKinsey & Company (2022). The Great Talent Shift: How Displaced MNC Workers are Helping Emerging Economies Innovate. This would substantiate the recommendation on engaging fractional talent for global market navigation.

- Harvard Business Review (2022). The Future of Work: How Fractional Talent is Shaping Startups’ Global Expansion. A useful reference for discussing fractional talent models and how they can empower ASEAN startups.

- UNFCCC COP29 (2024). Annual Conference Report: Key Outcomes on Global Sustainability and Carbon Reduction. This document would provide insights into how global conferences like COP29 are shaping the policy and financial landscapes for regenerative economies.

- Carbon Disclosure Project (2021). Carbon Accounting and Scope 3 Emissions: Aligning Global Standards with Local Markets. Offers details on the role of Scope 3 emissions in global supply chains, with relevant implications for ASEAN.

- Bain & Company (2023). Sustainability-Driven Innovation in Emerging Markets: The ASEAN Opportunity. Analyzes opportunities in ASEAN for integrating sustainability and innovation to drive economic growth.

- OECD (2021). Sustainable Innovation in Emerging Economies: Leveraging GreenTech and AgTech. This document would enhance the understanding of the intersection of sustainability and innovation in emerging markets like ASEAN.

- Circle Economy (2022). The Circular Economy in Southeast Asia: Pathways for Growth and Innovation. This would provide crucial data and insights into ASEAN’s evolving circular economy.

- McKinsey & Company (2022). The Future of Supply Chains: Integrating Sustainability and Circular Economy Models. This can be referenced for the shift to circular economy models, especially in ASEAN’s manufacturing and supply chain sectors.

- COP29 Declaration (2024). Private Sector Engagement in Climate Action: ASEAN’s Role in Global Sustainability Efforts. This reference will be important in illustrating ASEAN’s role in global climate action, tying back to policy reforms and regulatory frameworks.

- Diego-Ayala, Ulises, Diego-Ayala, Ulises, "An investigation into hybrid power trains for vehicles with regenerative braking", 2007.

- Koh, J., Stremke, S., "Sustainable energy transition: properties and constraints of regenerative energy systems with respect to spatial planning and design", 2009.

- Anderson, Ryan B., "Sustainability, ideology, and the politics of development in Cabo Pulmo, Baja California Sur, Mexico", Scholar Commons, 2015.

- Ott, Hermann E., von Seht, Hauke, "EU environmental principles: Implementation in Germany".

- Capata, Roberto, "Urban and extra-urban hybrid vehicles: a technological review", 'MDPI AG', 2018.

- Beatley, Beatley, Brown, Browning, Burckhardt, Karyono, Kellert, Kopeva, Loures, Lyle, Pedersen, Prominski, Raymond, Santamouris, Van der Ryn, Weidiniger, "Urban river recovery inspired by nature-based solutions and biophilic design in Albufeira, Portugal", 'MDPI AG', 2018.

- Charnley, Fiona, De los Rios, Carolina, Moreno, Mariale, Rowe, Zoe O., "A conceptual framework for circular design", 'MDPI AG', 2016.

- Cerreta, M., di Girasole, E. G., Poli, G., Regalbuto, S., "Operationalizing the circular city model for naples' city-port: A hybrid development strategy", 'MDPI AG', 2020.

- Aillery, Marcel P., Hrubovcak, James, Kramer-Leblanc, Carol S., Shoemaker, Robbin A., Tegene, Abebayehu, "AGRICULTURE IN AN ECOSYSTEMS FRAMEWORK".

- Beatley, Beatley, Brown, Browning, Burckhardt, Karyono, Kellert, Kopeva, Loures, Lyle, Pedersen, Prominski, Raymond, Santamouris, Van der Ryn, Weidiniger, "Urban river recovery inspired by nature-based solutions and biophilic design in Albufeira, Portugal", 'MDPI AG', 2018.

- Aguayo-González, Francisco, Lama-Ruiz, Juan Ramón, Martín-Gómez, Alejandro Manuel, Ávila-Gutiérrez, María Jesús, "Eco-Holonic 4.0 Circular Business Model to Conceptualize Sustainable Value Chain Towards Digital Transition ", 'MDPI AG', 2020.

- Osmond, P , Prasad, D , Sala Benites, H , "A Future-Proof Built Environment through Regenerative and Circular Lenses—Delphi Approach for Criteria Selection", MDPI, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).