Submitted:

13 January 2025

Posted:

14 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Optimisation of Optimal Conditions for the Infiltration Method in the ZADT Transient Transformation System

2.2. Optimal Conditions for Screening Injection Methods

2.3. Transient Conversion of ZADT Using Ultrasonic Vacuum Method

2.4. Three Methods to Express the Duration of the ZADT Transient Transformation System

2.5. Preliminary Functional Validation of Salt Tolerance Candidate Genes Was Conducted Through Transient Transformation of ZADT Using the Infiltration Method

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Experimental Materials

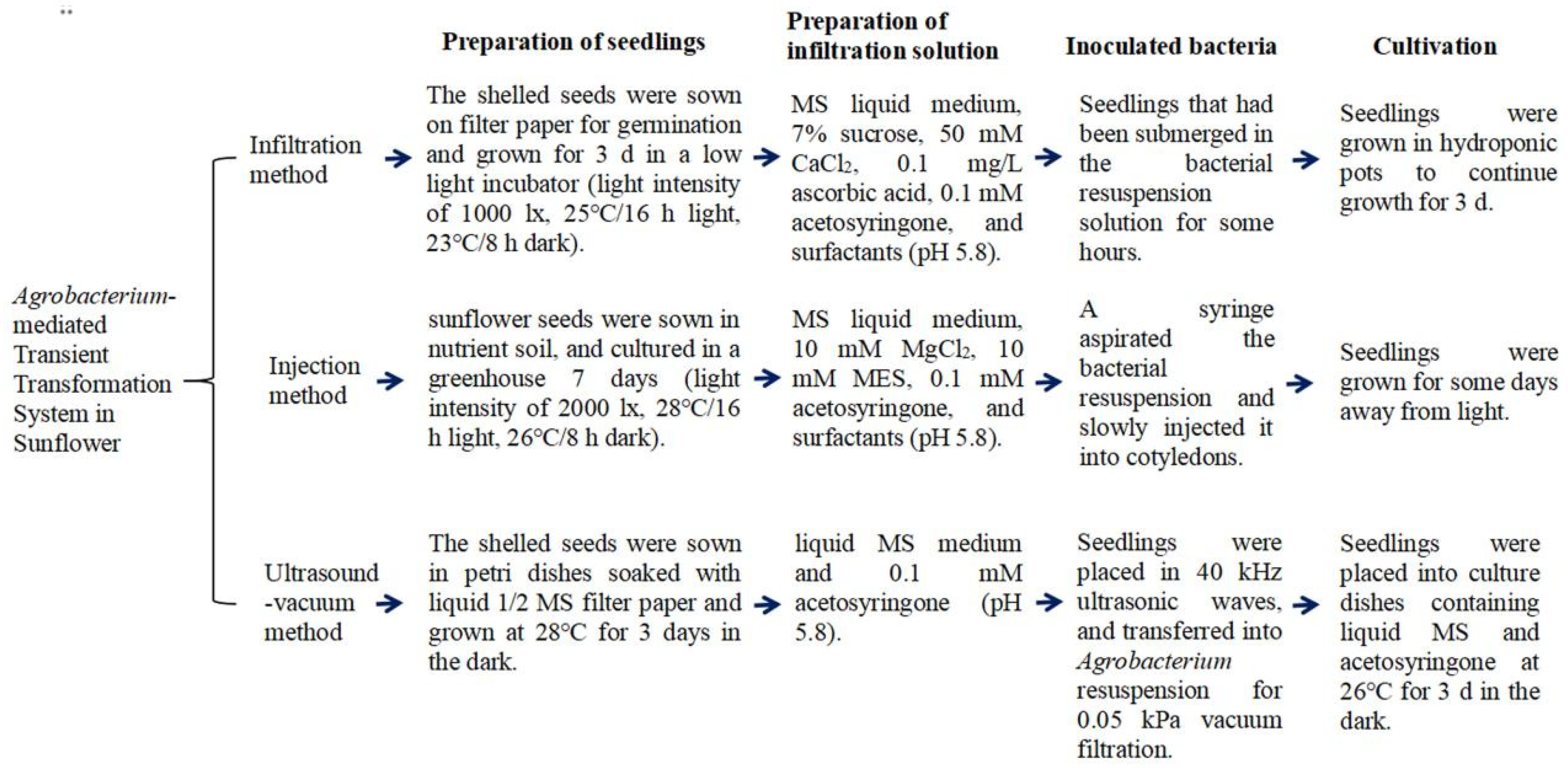

4.2. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Transformation of Sunflower

4.2.1. Infiltration

4.2.2. Cotyledonary Injection

4.2.3. Ultrasonic-Vacuum Infiltration

4.3. Detection of Transient Transformation Efficiency and Duration

4.6. Construction of Recombinant Plasmids

4.7. Plant Protein Extraction and Western Blotting Experiments

4.8. Data Analysis and Graph Construction

5. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Temme, A.A.; Kerr, K.L.; Masalia, R.R.; Burke, J.M.; Donovan, L.A. Key traits and genes associate with salinity tolerance independent from vigor in cultivated sunflower. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184(2), pp.00873.

- Kumar, A.P.K.; et al. Genetics, genomics and breeding of sunfower. Lewes, Delaware : Excelic Press LLC, 2019.

- Su, W.B.; Xu, M.Y.; Radani, Y.; Yang, L.M. Technological development and application of plant genetic transformation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(13), 10646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darqui, F.S.; Radonic, L.M.; Beracochea, V.C.; Hopp, H.E.; Bilbao, L.M. Peculiarities of the transformation of Asteraceae family species: The cases of sunflower and lettuce. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 12, e767459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.X.; Wu, Q.Q.; Guo, F.Q.; Ouyang, Y.Z.; Ao, D.Y.; You, S.J.; Liu, Y.Y. A versatile, rapid Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression system for functional genomics studies in cannabis seedling. Planta. 2024, 260, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.J.; Niu, C.; Xie, Q.; Xing, Q.; Qi, H. The recent advances of transient expression system in horticultural plants. Acta Hortic Sin. 2017, 44(9), 1796–1810. [Google Scholar]

- Tyurin, A.A.; Suhorukova, A.V.; Kabardaeva, K.V.; Goldenkova-Pavlova, I.V. Transient gene expression is an effective experimental tool for the research into the fine mechanisms of plant gene function: advantages, limitations, and solutions. Plants. 2020, 9(9), 1187–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leissing, F.; Reinstdler, A.; Thieron, H.; Panstrega, R. Gene gun-mediated transient gene expression for functional studies in plant immunity. Methods Mol Biol. 2022, 2523, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, D.L.; Shi, S.L.; Li, S.H.; Li, L.Z.; He, Y.J.; Li, J.Y.; Chen, H.Y.; et al. A highly efficient mesophyll protoplast isolation and PEG-mediated transient expression system in eggplant. Sci Hortic. 2022, 304, 111303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y.J.; Li, Y.L.; Bi, P.P.; Wang, D.J.; Feng, J.Y. Optimization of the protoplast transient expression system for gene functional studies in strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020, 141, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Gao, J.; Lu, C.Q.; Wei, Y.L.; Jin, J.P.; Wong, S.M.; Zhu, G.F.; Yang, F.X. Highly efficient protoplast isolation and transient expression system for functional characterization of flowering related genes in cymbidium orchids. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21(7), 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zottini, M.; Barizza, E.; Costa, A.; Formentin, E.; Ruberti, C.; Carimi, F.; Schiavo, F.L. Agroinfiltration of grapevine leaves for fast transient assays of gene expression and for long-term production of stable transformed cells. Plant Cell Rep. 2008, 27(5), 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, K.; Qi, Y.P.; Nguyen, L.V.; Bethke, G.; Tsuda, Y.; Glazebrook, J.; Katagiri, F. An efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012, 69, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Liu, G.F.; Meng, X.N.; Li, Y.B.; Wang, Y.C. A versatile Agrobacterium-mediated transient gene expression system for herbaceous plants and trees. Bioch Gene 2012, 50(9-10), 761–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.W.; Dong, B.; Zhou, J.; Miao, Y.F.; Yang, L.Y. Wang, Y.G. Xiao, Z.; Fang, Q.; Wan, Q.Q.; Zhao, H.B. Highly efficient transient gene expression of three tissues in Osmanthus fragrans mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Sci Hortic. 2023, 310, 111725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. Wang, Y.C.; Wang, Z.B. Optimizing transient genetic transformation method on Arabidopsis plants mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Northeast Forestryuniversity. 2016, 44, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, He JJ, Liu L; Xie, R.D.; Qiu, L.; Li, X.C.; Yuan, W.J.; Chen, K.; Yin, Y.T.; Kyaw, M.M.M.; et al. A convenient, rapid and efficient method for establishing transgenic lines of Brassica napus. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, B.; Xi, Z.Q.; Ren, C.X.; Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Pei, J. The establishment of transient expression systems and their application for gene function analysis of favonoid biosynthesis in Carthamus tinctorius L. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Yang, Q.; Yang, T.R.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G.X.; Yang, F.Y.; Wang, R.G.; Lin, X.F.; Li, G.J. Development of Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression system in Caragana intermedia and characterization of CiDREB1C in stress response. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, J.J.; Xie, L.; Shi, H.W.; Cui, S.R.; Lan, F.S.; Luo, Z.L.; Ma, X.J. Development of an efficient transient expression system for Siraitia grosvenorii fruit and functional characterization of two NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductases. Phytochemistry. 2021, 189, 112824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livak, K.J. Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25(4), 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelly, N.S.; Valat, L.; Walter, B.; Maillot, P. Transient expression assays in grapevine: a step towards genetic improvement. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014, 12(9), 1231–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ku, S.S.; Ye, X.; He, C.; Kwon, S.Y.; Choi, P.S. Current status of genetic transformation technology developed in Cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.). J Integr Agr. 2015, 14, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadegan, R.; Maroufi, A. In vitro regeneration and Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of Dragon’s Head plant (Lallemantia iberica). Sci Rep. 2022, 12(1), 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, J.K.; Kon, B.; Chung-Mo, P. Optimization of conditions for transient Agrobacterium-mediated gene expression assays in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Faizal, A.; Geelen, D. Agroinfiltration of intact leaves as a method for the transient and stable transformation of saponin producing Maesa Lanceolata. Plant Cell Rep. 2012, 31, 1517–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, S.X.; Kang, X.N.; Ge, J.Y.; Fei, R.W.; Duan, S.Y.; Sun, X.M. An efficient Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation system and its application in gene function elucidation in Paeonia lactiflora Pall. Front Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 999433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.W.; Ma, J.J.; Liu, H.M.; Guo, Y.T.; Li, W.; Niu, S.H. An efficient system for Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation in Pinus tabuliformis. Plant Methods. 2020, 16, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang SY, Hu R, Yang L, Zuo ZJ. Establishment of a transient transformation protocol in Cinnamomum camphora. Forests. 2023, 14(9), 1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.P.; Chen, T.T.; Wang, W. Liu, H.; Yan, X.; Wu-Zhang, K.Y.; Qin, W.; Xie, L.H,; Zhang, Y.J. Peng, B.W. et al. A high-efciency Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression system in the leaves of Artemisia annua L. Plant Methods. 2021, 17, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.L. Construction of transients system and function analysis of FT gene in mulberry (Morus alba L.). 2015. [master’s thesis] (Xi’an Shaanxi: Shaanxi Normal University).

- Chen, X.J.; He, S.T.; Jiang, L.N.; Li, X.Z.; Guo, W.L.; Chen, B.H.; Zhou, J.G. ; Skliar,V. An efficient transient transformation system for gene function studies in pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata D.). Sci Horticulturae. 2021, 282, 110028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.L.; Li, Y.N.; Wen, Z.B. The establishment and preliminary verification of transient transformation system of Salsola Laricifolia. Arid Zone Res. 2020, 37, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, R.L.; Yang, S.C.; Zhang, Q.L.; Xu, L.Q.; Luo, Z.R. Vacuum infiltration enhances the Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation for gene functional analysis in persimmon (Diospyros kaki thunb.). Sci Hortic Amsterdam. 2019, 251, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J.; Leng, Y.R.; Jing, S.L.; Zheng, C.P.; Lang, C.J.; Yang, L.P. Using vacuum infection method to transiently expression of GUS Gene in Medicago sativa L. by vacuum infiltration. Mol Plant Breed. 2021, 20, 859–864. [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, B.; Citovsky, V. The roles of bacterial and host plant factors in Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation. Int J Dev Biol 2013, 57(6-7-8), 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, T. Analysis of the intracellular localization of transiently expressed and fluorescently labeled copper-containing amine oxidases, diamine oxidase and N-methylputrescine oxidase in tobacco, using an Agrobacterium infiltration protocol. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1694, 215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.P.; Li, K.; Guo, Y.T.; Guo, J.G.; Miao, K.T.; Botella, J.R.; Song, C.P.; Miao, Y.C. A transient transformation system for gene characterization in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Plant Methods. 2018, 14, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Liang, Y.; Lee, Y.; Pidatala, V.R.; Mortimer, J.C.; Scheller, H.V. Agrobacterium-mediated transient transformation of sorghum leaves for accelerating functional genomics and genome editing studies. BMC Res Notes. 2020, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.L.; Han, X.; Jin, R.X.; Jiao, J.B.; Wang, J.W.; Niu, S.Y.; Yang, Z.Y.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.C. Generation of CRISPR-edited birch plants without DNA integration using Agrobacterium- mediated transformation technology. Plant Science. 2024, 342, 112029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.M.; Huang, Y.Z.; Wang, Q.; Guo, D.J. AaHY5 ChIP-seq based on transient expression system reveals the role of AaWRKY14 in artemisinin biosynthetic gene regulation. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2021, 168, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.J.; Fang, J.R.; Lv, J.X.; Li, Z.Y. , Liu, Z. Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, C. Gao, C.Q. Overexpression of ThSCL32 confers salt stress tolerance by enhancing ThPHD3 gene expression in Tamarix hispida. Tree Physiol. 2023, 43(8), 1444–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).