Submitted:

14 January 2025

Posted:

15 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

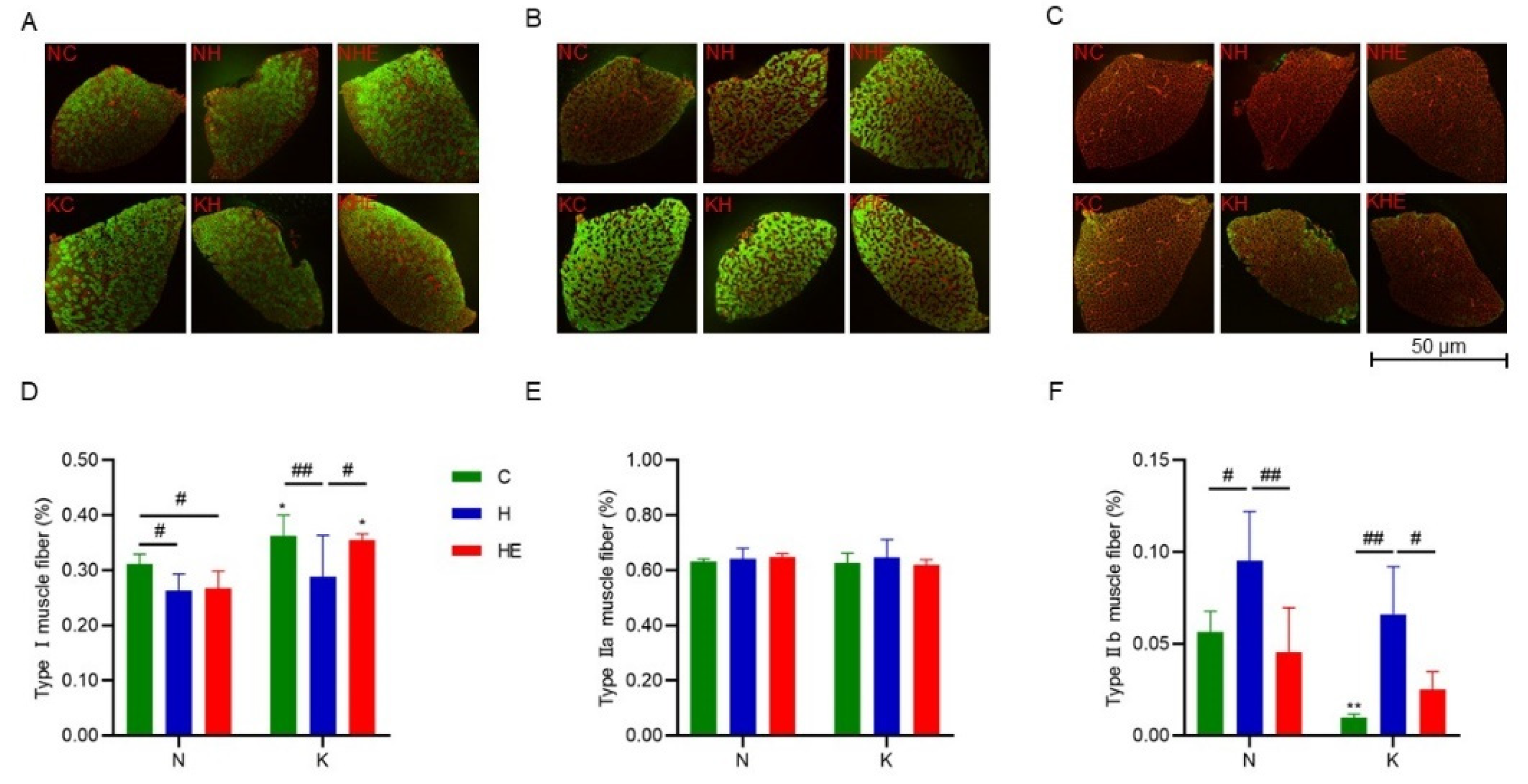

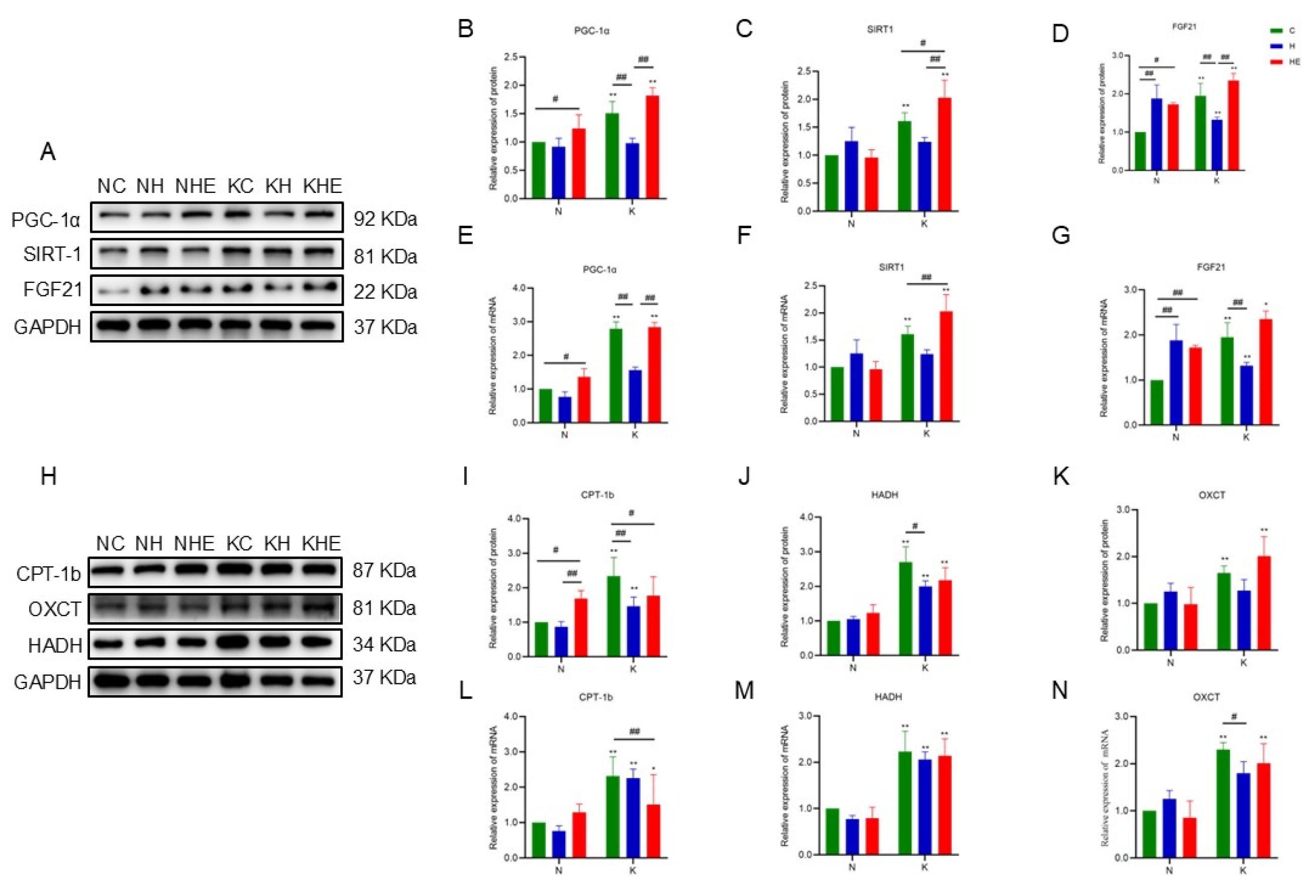

Abstract

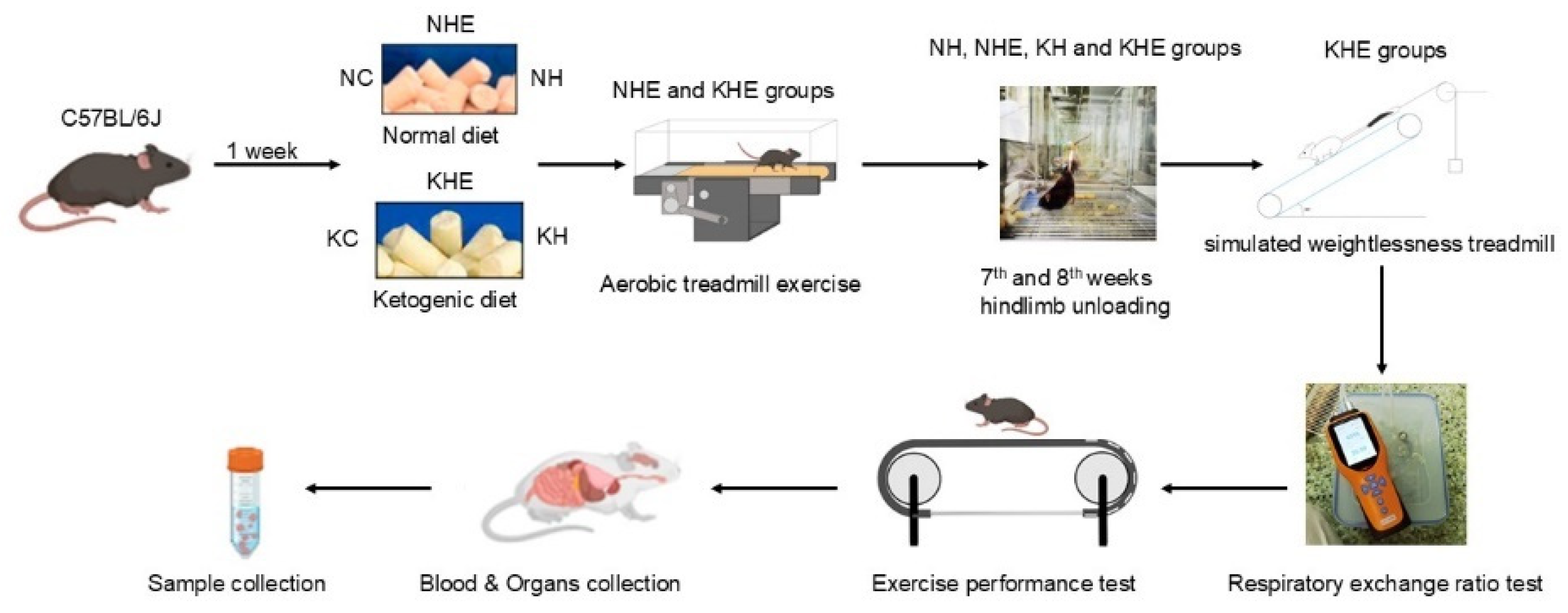

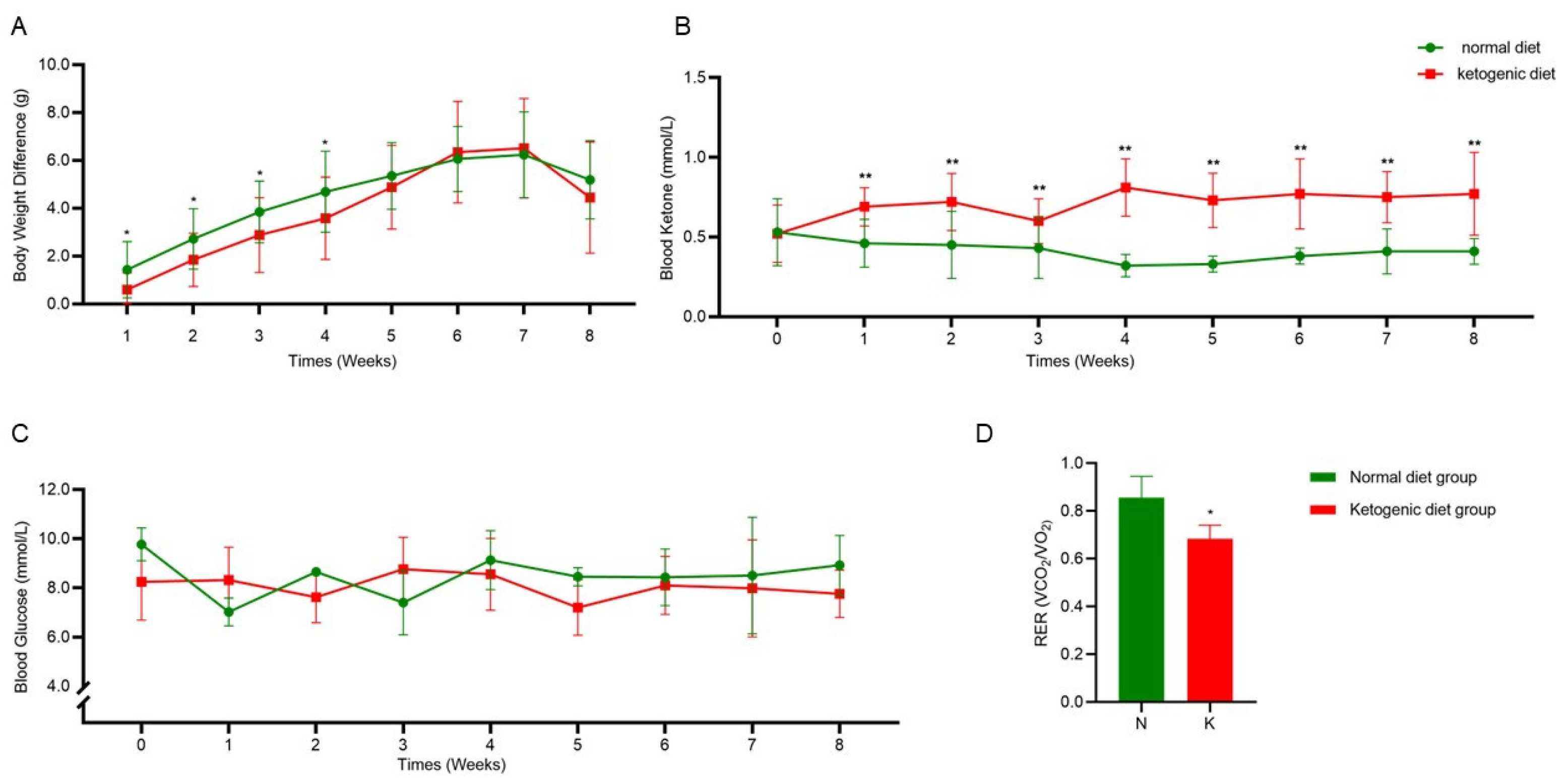

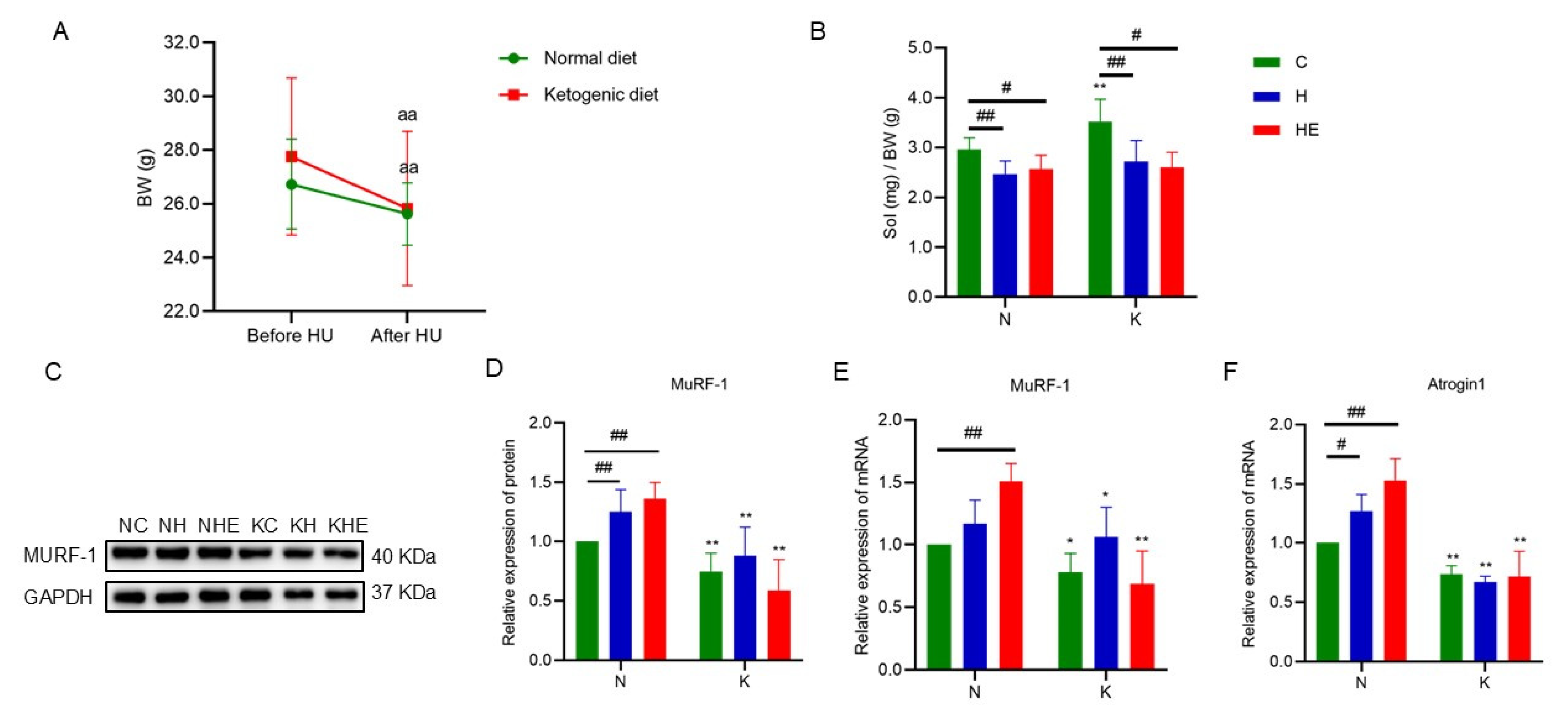

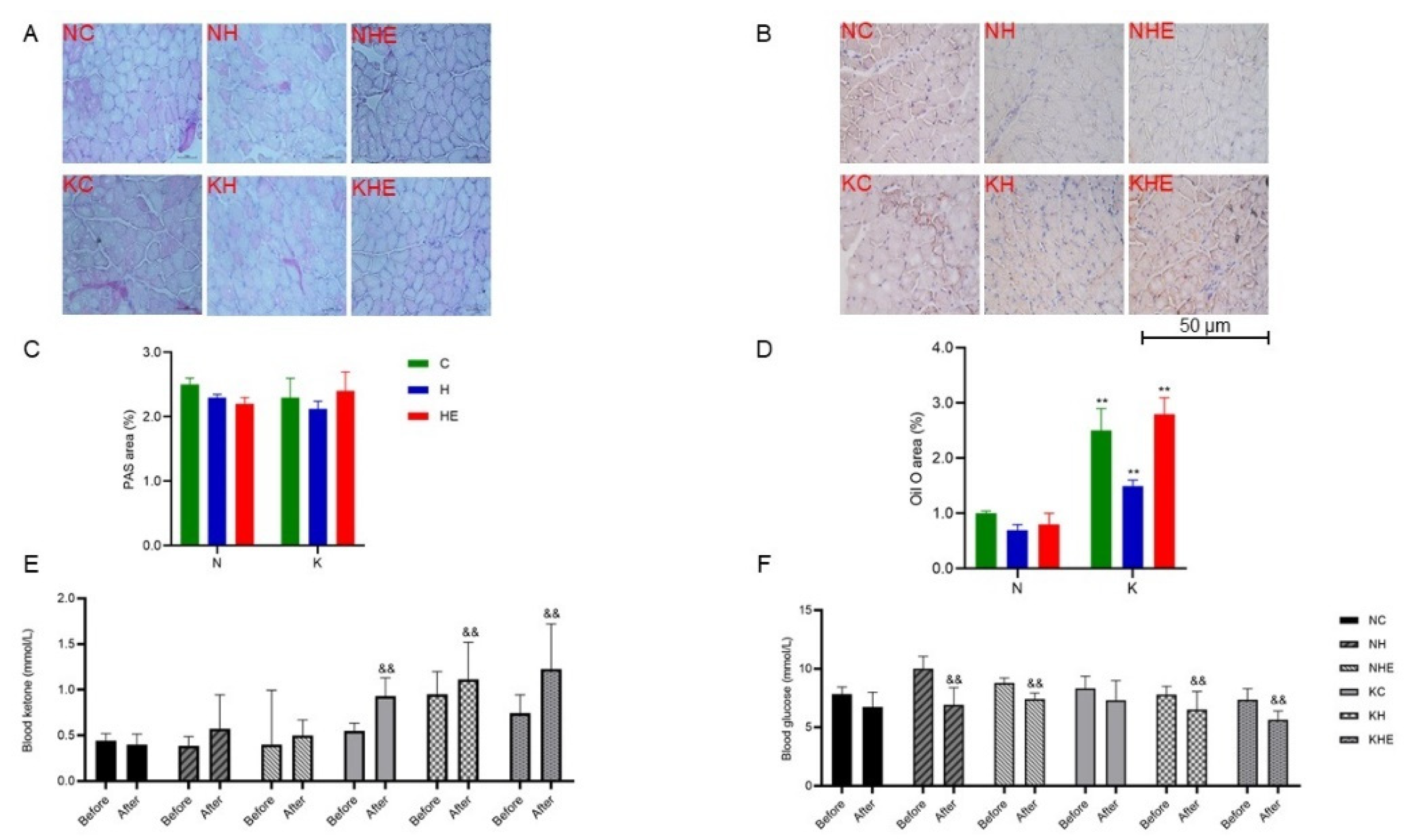

Objective: To investigate the effects of an 8-week ketogenic diet combined with aero-bic exercise on muscle fiber composition and exercise capacity in mice subjected to simulated microgravity. Methods: Seven-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were randomly assigned to six groups: normal diet (NC), ketogenic diet (KC), normal diet + tail sus-pension (NH), ketogenic diet + tail suspension (KH), normal diet + tail suspension + exercise (NHE), and ketogenic diet + tail suspension + exercise (KHE). During the final two weeks of the intervention, a tail suspension model was employed to simulate mi-crogravity in the tail suspension groups, while the exercise groups performed moder-ate-intensity aerobic exercise. The exercise protocol involved running at 12 m/min for 60 minutes per day, 6 days per week, over the course of 8 weeks. Weekly measure-ments included body weight, blood ketones, and blood glucose concentrations. Respir-atory metabolic rates were assessed before and after tail suspension. Following the in-tervention, all mice underwent a forced exercise test. Blood was collected via the or-bital sinus immediately after the test, and the bilateral soleus muscles were quickly ex-cised. Biochemical analysis was performed to assess blood markers, and Western blot-ting and RT-PCR were used to examine changes in protein and gene expression in skeletal muscle. Additionally, Oil Red O and PAS staining were utilized to evaluate li-pid deposition and glycogen content in the muscles. Immunofluorescence staining was employed to analyze the distribution of MHC muscle fibers in skeletal muscle. Results: Mice in the tail suspension model exhibited weight loss, muscle atrophy, shifts in muscle fiber type, and decreased endurance. However, the combined intervention of a ketogenic diet and aerobic exercise significantly reduced markers of muscle atrophy, enhanced the expression of proteins and genes related to fat metabolism, increased the proportion of MHC-I muscle fibers in the soleus muscle, and decreased the proportion of MHC-IIb fibers. This combined intervention, which primarily utilizes ketone body metabolism, significantly enhanced fat metabolism, thereby improving exercise capac-ity in the mice. Conclusion: The combined intervention of a ketogenic diet and aerobic exercise effectively mitigated muscle atrophy in mice subjected to simulated micro-gravity, enhanced the expression of fat metabolism-related genes in skeletal muscles, and inhibited the transition from slow-twitch to fast-twitch muscle fibers, ultimately improving the exercise capacity of the mice.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Diets

2.2. Simulated Weightlessness Model

2.3. Training Protocols

2.4. Respiratory Exchange Eatio Test

2.5. Assessment of Endurance Exercise Performance

2.6. Tissue Sampling

2.7. Plasma Biochemical Assessment

2.8. Oil Red O Staining

2.9. Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) Staining

2.10. Western Blotting

2.11. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.12. Histological Staining

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of the Ketogenic Diet Model

3.2. The Effects on Body Weight and Skeletal Muscle Mass in Simulated Weightlessness Mice

3.3. The Effects on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Mice

3.4. The Effects on Muscle Fiber Types in Mouse Skeletal Muscle

3.5. The Effects on the Expression of Skeletal Muscle-Related Proteins and Genes in Mice

3.6. The Effects of Exercise Capacity in Mice

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trappe, T.A.; Minchev, K.; Perkins, R.K.; Lavin, K.M.; Jemiolo, B.; Ratchford, S.M.; Claiborne, A.; Lee, G.A.; Finch, W.H.; Ryder, J.W.; et al. NASA SPRINT Exercise Program Efficacy for Vastus Lateralis and Soleus Skeletal Muscle Health during 70 Days of Simulated Microgravity. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md 1985 2024, 136, 1015–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.-Q.; Li, J. Ketogenic Diets and Protective Mechanisms in Epilepsy, Metabolic Disorders, Cancer, Neuronal Loss, and Muscle and Nerve Degeneration. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Hagopian, K.; López-Domínguez, J.A.; Kim, K.; Jasoliya, M.; Roberts, M.N.; Cortopassi, G.A.; Showalter, M.R.; Roberts, B.S.; González-Reyes, J.A.; et al. A Ketogenic Diet Impacts Markers of Mitochondrial Mass in a Tissue Specific Manner in Aged Mice. Aging 2021, 13, 7914–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukao, T.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Mitchell, G.A. Pathways and Control of Ketone Body Metabolism: On the Fringe of Lipid Biochemistry. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2004, 70, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McSwiney, F.T.; Wardrop, B.; Hyde, P.N.; Lafountain, R.A.; Volek, J.S.; Doyle, L. Keto-Adaptation Enhances Exercise Performance and Body Composition Responses to Training in Endurance Athletes. Metabolism. 2018, 83, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kephart, W.C.; Pledge, C.D.; Roberson, P.A.; Mumford, P.W.; Romero, M.A.; Mobley, C.B.; Martin, J.S.; Young, K.C.; Lowery, R.P.; Wilson, J.M.; et al. The Three-Month Effects of a Ketogenic Diet on Body Composition, Blood Parameters, and Performance Metrics in CrossFit Trainees: A Pilot Study. Sports Basel Switz. 2018, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloemberg, D.; Quadrilatero, J. Rapid Determination of Myosin Heavy Chain Expression in Rat, Mouse, and Human Skeletal Muscle Using Multicolor Immunofluorescence Analysis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, M.A.; Aguirre, N.W.; Marcotte, G.R.; Marshall, A.G.; Baehr, L.M.; Hughes, D.C.; Hamilton, K.L.; Roberts, M.N.; Lopez-Dominguez, J.A.; Miller, B.F.; et al. The Ketogenic Diet Preserves Skeletal Muscle with Aging in Mice. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, Y.; Kakehashi, C.; Yoshihara, T.; Kurosaka, M.; Kakigi, R.; Higashida, K.; Fujiwara, S.-E.; Akema, T.; Funabashi, T. Ketogenic Diet Feeding Improves Aerobic Metabolism Property in Extensor Digitorum Longus Muscle of Sedentary Male Rats. PloS One 2020, 15, e0241382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.A.B.; Murach, K.A.; Dyar, K.A.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise Metabolism and Adaptation in Skeletal Muscle. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.C.; Bryce, G.R.; Conlee, R.K. Adaptations to a High-Fat Diet That Increase Exercise Endurance in Male Rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 1984, 56, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Huang, Q.; Yada, K.; Liu, C.; Suzuki, K. An 8-Week Ketogenic Low Carbohydrate, High Fat Diet Enhanced Exhaustive Exercise Capacity in Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simi, B.; Sempore, B.; Mayet, M.H.; Favier, R.J. Additive Effects of Training and High-Fat Diet on Energy Metabolism during Exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md 1985 1991, 71, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer, D.K.; Ahlsén, M.; Norrbom, J.; Jansson, E.; Hjeltnes, N.; Gustafsson, T.; Krook, A. Human Skeletal Muscle Fibre Type Variations Correlate with PPAR Alpha, PPAR Delta and PGC-1 Alpha mRNA. Acta Physiol. Oxf. Engl. 2006, 188, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Wu, H.; Tarr, P.T.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Wu, Z.; Boss, O.; Michael, L.F.; Puigserver, P.; Isotani, E.; Olson, E.N.; et al. Transcriptional Co-Activator PGC-1 Alpha Drives the Formation of Slow-Twitch Muscle Fibres. Nature 2002, 418, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortensen, O.H.; Frandsen, L.; Schjerling, P.; Nishimura, E.; Grunnet, N. PGC-1alpha and PGC-1beta Have Both Similar and Distinct Effects on Myofiber Switching toward an Oxidative Phenotype. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 291, E807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnyder, S.; Svensson, K.; Cardel, B.; Handschin, C. Muscle PGC-1α Is Required for Long-Term Systemic and Local Adaptations to a Ketogenic Diet in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 312, E437–E446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, K.; Albert, V.; Cardel, B.; Salatino, S.; Handschin, C. Skeletal Muscle PGC-1α Modulates Systemic Ketone Body Homeostasis and Ameliorates Diabetic Hyperketonemia in Mice. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2016, 30, 1976–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Hou, L.; Xiong, Y.; Zhao, S. Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 (FGF21) Promotes Formation of Aerobic Myofibers via the FGF21-SIRT1-AMPK-PGC1α Pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 1893–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.S.; Li, Z.L.; Zhang, J.F.; Liu, S.J.; Chen, W.J.; Wang, H.J.; Wang, L.J.; Li, Y.H. A Method for Treadmill Exercise Simulating Weightlessness in Rats and A Rat Weightlessness Simulation Treadmill 2016.

- Dougherty, J.P.; Springer, D.A.; Gershengorn, M.C. The Treadmill Fatigue Test: A Simple, High-Throughput Assay of Fatigue-like Behavior for the Mouse. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2016, 54052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, N.; Arnold, A.-S.; Item, F.; Summermatter, S.; Santos, G.B.S.; Christe, M.; Boutellier, U.; Toigo, M.; Handschin, C. Electric Pulse Stimulation of Cultured Murine Muscle Cells Reproduces Gene Expression Changes of Trained Mouse Muscle. PloS One 2010, 5, e10970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, C.; Mancinelli, L.; Matacchione, G.; Olivieri, F.; Antonicelli, R. The Cardioprotective Effects of Nutritional Ketosis: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeukendrup, A.E.; Wallis, G.A. Measurement of Substrate Oxidation during Exercise by Means of Gas Exchange Measurements. Int. J. Sports Med. 2005, 26 Suppl 1, S28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, R.; Drescher, C.; Nowotny, K.; Grune, T.; Castro, J.P. Impaired Proteostasis during Skeletal Muscle Aging. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 132, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, F.M.; Maratos-Flier, E. Understanding the Physiology of FGF21. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdurrachim, D.; Woo, C.C.; Teo, X.Q.; Chan, W.X.; Radda, G.K.; Lee, P.T.H. A New Hyperpolarized 13C Ketone Body Probe Reveals an Increase in Acetoacetate Utilization in the Diabetic Rat Heart. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, A.; Saha, P.K.; Jain, A.; Jung, S.Y.; Mynatt, R.L.; Pi, X.; Xie, L. PHDs/CPT1B/VDAC1 Axis Regulates Long-Chain Fatty Acid Oxidation in Cardiomyocytes. Cell Rep. 2021, 37, 109767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhu, M.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; Ji, G. Gan-Jiang-Ling-Zhu Decoction Alleviates Hepatic Steatosis in Rats by the miR-138-5p/CPT1B Axis. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltais, F.; Simard, A.A.; Simard, C.; Jobin, J.; Desgagnés, P.; LeBlanc, P. Oxidative Capacity of the Skeletal Muscle and Lactic Acid Kinetics during Exercise in Normal Subjects and in Patients with COPD. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 153, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckett, T.L.; Studzinski, C.M.; Keller, J.N.; Paul Murphy, M.; Niedowicz, D.M. A Ketogenic Diet Improves Motor Performance but Does Not Affect β-Amyloid Levels in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Res. 2013, 1505, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bielohuby, M.; Menhofer, D.; Kirchner, H.; Stoehr, B.J.M.; Müller, T.D.; Stock, P.; Hempel, M.; Stemmer, K.; Pfluger, P.T.; Kienzle, E.; et al. Induction of Ketosis in Rats Fed Low-Carbohydrate, High-Fat Diets Depends on the Relative Abundance of Dietary Fat and Protein. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 300, E65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielohuby, M.; Sawitzky, M.; Stoehr, B.J.M.; Stock, P.; Menhofer, D.; Ebensing, S.; Bjerre, M.; Frystyk, J.; Binder, G.; Strasburger, C.; et al. Lack of Dietary Carbohydrates Induces Hepatic Growth Hormone (GH) Resistance in Rats. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 1948–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellenbroek, J.H.; van Dijck, L.; Töns, H.A.; Rabelink, T.J.; Carlotti, F.; Ballieux, B.E.P.B.; de Koning, E.J.P. Long-Term Ketogenic Diet Causes Glucose Intolerance and Reduced β- and α-Cell Mass but No Weight Loss in Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 306, E552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukushima, A.; Ogura, Y.; Furuta, M.; Kakehashi, C.; Funabashi, T.; Akema, T. Ketogenic Diet Does Not Impair Spatial Ability Controlled by the Hippocampus in Male Rats. Brain Res. 2015, 1622, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, B.A.; Walton, C.M.; Carr, S.T.; Andrus, J.L.; Cheung, E.C.K.; Duplisea, M.J.; Wilson, E.K.; Draney, C.; Lathen, D.R.; Kenner, K.B.; et al. β-Hydroxybutyrate Elicits Favorable Mitochondrial Changes in Skeletal Muscle. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, H.A.; Kephart, W.C.; Mumford, P.W.; Romero, M.A.; Mobley, C.B.; Zhang, Y.; Roberts, M.D.; Kavazis, A.N. Ketogenic Diet Increases Mitochondria Volume in the Liver and Skeletal Muscle without Altering Oxidative Stress Markers in Rats. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.N.; Wallace, M.A.; Tomilov, A.A.; Zhou, Z.; Marcotte, G.R.; Tran, D.; Perez, G.; Gutierrez-Casado, E.; Koike, S.; Knotts, T.A.; et al. A Ketogenic Diet Extends Longevity and Healthspan in Adult Mice. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Moraleda, E.; Delisle, C.; Collado Mateo, D.; Aznar-Lain, S. [Weight loss and body composition changes through ketogenic diet and physical activity: a methodological and systematic review]. Nutr. Hosp. 2019, 36, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sahagun, E.; Ward, L.M.; Kinzig, K.P. Attenuation of Stress-Induced Weight Loss with a Ketogenic Diet. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 212, 112654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Zou, K. Effect of Ketogenic Diet on Exercise Tolerance and Transcriptome of Gastrocnemius in Mice. Open Life Sci. 2023, 18, 20220570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, K.; Saito, H.; Sumi, K.; Sakamoto, Y.; Tachi, Y.; Iida, K. Short-Term and Long-Term Ketogenic Diet Therapy and the Addition of Exercise Have Differential Impacts on Metabolic Gene Expression in the Mouse Energy-Consuming Organs Heart and Skeletal Muscle. Nutr. Res. N. Y. N 2018, 60, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, M.A.; Aguirre, N.W.; Marcotte, G.R.; Marshall, A.G.; Baehr, L.M.; Hughes, D.C.; Hamilton, K.L.; Roberts, M.N.; Lopez-Dominguez, J.A.; Miller, B.F.; et al. The Ketogenic Diet Preserves Skeletal Muscle with Aging in Mice. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Vidales, J.; González-Reyes, J.A.; Shibata, B.; Baar, K.; Rutkowsky, J.M.; Ramsey, J.J. A 1-Month Ketogenic Diet Increased Mitochondrial Mass in Red Gastrocnemius Muscle, but Not in the Brain or Liver of Middle-Aged Mice. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilodeau, P.A.; Coyne, E.S.; Wing, S.S. The Ubiquitin Proteasome System in Atrophying Skeletal Muscle: Roles and Regulation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2016, 311, C392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, T.P.; Wade, C.E. Metabolic Consequences of Muscle Disuse Atrophy. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 1824S–1828S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciciliot, S.; Rossi, A.C.; Dyar, K.A.; Blaauw, B.; Schiaffino, S. Muscle Type and Fiber Type Specificity in Muscle Wasting. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2191–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Pessin, J.E. Mechanisms for Fiber-Type Specificity of Skeletal Muscle Atrophy. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2013, 16, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, S.L.; Rygiel, K.; Purves-Smith, F.M.; Solbak, N.M.; Turnbull, D.M.; Hepple, R.T. Denervation Causes Fiber Atrophy and Myosin Heavy Chain Co-Expression in Senescent Skeletal Muscle. PloS One 2012, 7, e29082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aare, S.; Spendiff, S.; Vuda, M.; Elkrief, D.; Perez, A.; Wu, Q.; Mayaki, D.; Hussain, S.N.A.; Hettwer, S.; Hepple, R.T. Failed Reinnervation in Aging Skeletal Muscle. Skelet. Muscle 2016, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, B.M.; Deemer, S.E.; Smith, D.L.; Mobley, J.A.; Musi, N.; Plaisance, E.P. Effects of an Exogenous Ketone Ester Using Multi-Omics in Skeletal Muscle of Aging C57BL/6J Male Mice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, H.A.; Powers, S.K.; Naito, H.; Hughes, M.; Coombes, J.S. Exercise-Induced Alterations in Skeletal Muscle Myosin Heavy Chain Phenotype: Dose-Response Relationship. J. Appl. Physiol. Bethesda Md 1985 1999, 86, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, Y.; Naito, H.; Kakigi, R.; Akema, T.; Sugiura, T.; Katamoto, S.; Aoki, J. Different Adaptations of Alpha-Actinin Isoforms to Exercise Training in Rat Skeletal Muscles. Acta Physiol. Oxf. Engl. 2009, 196, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, Y.; Naito, H.; Kakigi, R.; Ichinoseki-Sekine, N.; Kurosaka, M.; Katamoto, S. Alpha-Actinin-3 Levels Increase Concomitantly with Fast Fibers in Rat Soleus Muscle. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 372, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K, S.; H, S.; K, S.; Y, S.; Y, T.; K, I. Short-Term and Long-Term Ketogenic Diet Therapy and the Addition of Exercise Have Differential Impacts on Metabolic Gene Expression in the Mouse Energy-Consuming Organs Heart and Skeletal Muscle. Nutr. Res. N. Y. N 2018, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura, Y.; Kakehashi, C.; Yoshihara, T.; Kurosaka, M.; Kakigi, R.; Higashida, K.; Fujiwara, S.-E.; Akema, T.; Funabashi, T. Ketogenic Diet Feeding Improves Aerobic Metabolism Property in Extensor Digitorum Longus Muscle of Sedentary Male Rats. PloS One 2020, 15, e0241382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Huang, Q.; Tominaga, T.; Liu, C.; Suzuki, K. An 8-Week Ketogenic Diet Alternated Interleukin-6, Ketolytic and Lipolytic Gene Expression, and Enhanced Exercise Capacity in Mice. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritzen, A.M.; Lundsgaard, A.-M.; Kiens, B. Tuning Fatty Acid Oxidation in Skeletal Muscle with Dietary Fat and Exercise. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2020, 16, 683–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, D.O.; Boros, L.G.; Crunkhorn, S.; Gami, H.; Patti, M.-E. Dual Modulation of Both Lipid Oxidation and Synthesis by Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-Gamma Coactivator-1alpha and -1beta in Cultured Myotubes. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2010, 24, 1003–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, K.E.; Mikus, C.R.; Slentz, D.H.; Seiler, S.E.; DeBalsi, K.L.; Ilkayeva, O.R.; Crain, K.I.; Kinter, M.T.; Kien, C.L.; Stevens, R.D.; et al. Muscle-Specific Overexpression of PGC-1α Does Not Augment Metabolic Improvements in Response to Exercise and Caloric Restriction. Diabetes 2015, 64, 1532–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, Z.; Zhao, M.; Nie, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, X. Skeletal Muscle Lipid Droplets and the Athlete’s Paradox. Cells 2019, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, P.J.; Clarke, K. Acute Nutritional Ketosis: Implications for Exercise Performance and Metabolism. Extreme Physiol. Med. 2014, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasai, H.; Aoyama, Y.; Otsuka, H.; Abdelkreem, E.; Naiki, Y.; Kubota, M.; Sekine, Y.; Itoh, M.; Nakama, M.; Ohnishi, H.; et al. Heterozygous Carriers of Succinyl-CoA:3-Oxoacid CoA Transferase Deficiency Can Develop Severe Ketoacidosis. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017, 40, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalska, P.; Crawford, P.A. Multi-Dimensional Roles of Ketone Bodies in Fuel Metabolism, Signaling, and Therapeutics. Cell Metab. 2017, 25, 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene Name | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|

| Atrogin1 | 5′-TCAGCAGCCTGAACTACGAC -3′ | 5′-GCGCTCCTTCGTACTTCCTT -3′ |

| MURF-1 | 5’-GTGTGAGGTGCCTACTTGCT-3’ | 5’-GACTTTTCCAGCTGCTCCCT-3’ |

| PGC-1α | 5′- AGCCGTGACCACTGACAACGAG-3′ | 5′- GCTGCATGGTTCTGAGTGCTAAG-3′ |

| SIRT1 | 5′- TACCTTGGAGCAGGTTGCAG-3′ | 5′- GCACCGAGGAACTACCTGAT-3′ |

| FGF21 | 5′- GCATACCCCATCCCTGACTC-3′ | 5′- GGATCAAAGTGAGGCGATCC-3′ |

| CPT-1b | 5′-TTCAACACTACACGCATCCC-3′ | 5′-GCCCTCATAGAGCCAGACC-3′ |

| HADH | 5′-ACACCTTCATTCGCCATATTGC-3′ | 5′-TCGGTGAATTTTCTGTAGACCAC-3′ |

| OXCT | 5′-CCCATACCCACTGAAAGACGAA-3′ | 5′- CTGGAGAAGAAAGAGGCTCCTG-3′ |

| 18s | 5′-GGGAGCCTGAGAAACGGC-3′ | 5′-GGGTCGGGAGTGGGTAATTT-3′ |

| TC (mmol/L) |

TG (mmol/L) |

HDL-C (mmol/L) |

LDL-C (mmol/L) |

UREA (mmol/L) |

Insulin (ng/mL) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 1.35 ± 0.15 | 0.38 ± 0.07 | 1.18 ± 0.09 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 9.57 ± 0.37 | 0.97 ± 0.21 |

| NH | 1.29 ± 0.23 | 0.58 ± 0.18 | 1.12 ± 0.13 | 0.18 ± 0.06 | 9.28 ± 0.34 | 1.72 ± 0.58## |

| NHE | 1.24 ± 0.21 | 0.59 ± 0.29 | 1.09 ± 0.21 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 8.33 ± 0.30 | 1.44 ± 0.56## |

| KC | 2.16 ± 0.20** | 0.63 ± 0.20** | 1.90 ± 0.12** | 0.27 ± 0.04** | 9.31 ± 0.80** | 1.51 ± 0.59* |

| KH | 1.96 ± 0.23#** | 0.99 ± 0.16##** | 1.64 ± 0.27##** | 0.25 ± 0.03** | 9.53 ± 0.85** | 1.38 ± 0.51** |

| KHE | 1.79± 0.36##** | 0.74 ± 0.29# | 1.55 ± 0.38##** | 0.23 ± 0.03## | 9.25 ± 0.42** | 1.65 ± 0.71** |

| LD (mmol/L) | UREA (mmol/L) | CK (U/L) |

LDH (U/L) |

Time (min) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 1.81±0.26 | 9.57±0.37 | 850±310 | 513±166 | 136 ± 15 |

| NH | 2.41±0.53## | 9.27±0.34 | 866±260 | 655±97 | 83 ± 24## |

| NHE | 2.32±0.34## | 8.33±0.30 | 749±275 | 547±113 | 84 ± 30## |

| KC | 2.43±0.39** | 9.20±0.71 | 981±233 | 521±180 | 152 ± 18 |

| KH | 2.23±0.46 | 9.26±0.61 | 863±315 | 615±272 | 81 ± 36## |

| KHE | 2.03±0.34## | 9.26±0.49 | 955±288 | 486±286 | 136 ± 26##* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).