1. Introduction

The global demand for chicken meat is increasing [

1], necessitating improvements in production efficiency, meat quality, animal health, and welfare [

2]. Modern farms aim to reduce production costs and labour needs while maintaining or increasing flock sizes, which has negatively impacted animal welfare and behaviour [

3]. Alongside declining labour availability [

4], these factors have driven the adoption of intelligent technologies [

5]. Various PLF tools help reduce production costs by monitoring environmental conditions, animal health, behaviour, and performance in real time [

6,

7,

8,

9]. PLF technologies are non-invasive, minimising stress on birds [

10]. These activities involve mechanical (sensors, robots) and digital (computer systems and software) tools, as well as socio-economic factors such as education and technology adoption [

11]. Measuring feed and water consumption helps detect issues with feed quality and animal health more easily [

12], while automated data collection provides up-to-date information on production parameters and welfare indices, enabling early problem detection [

8]. Precision technologies also enhance decision-making processes in production management and reduce economic losses [

13].

PLF systems involve three levels: information/data collection, processing, and supervision [

14]. Information perception uses sensors, IoT (Internet of Things), and algorithms as accurate and automatic tools [

14]. These systems, combined with artificial intelligence, support various areas of poultry production, including environmental conditions [

15,

16], animal behaviour [

17,

18], health [

19,

20], welfare [

21], and production efficiency [

22,

23].

Numerous precision tools are available on the market, providing software, systems, networks and devices for sound analysis, image and video analysis, weight and welfare monitoring, and the control of environmental conditions (air composition, light intensity, litter quality, temperature, etc.).

This review presents and critically reviews the available sources of information on precision livestock farming technologies, including all the significant methods and applications used in broiler production to improve animal health and welfare, nutrition and feed management practices.

2. Precision Tools for the Control of Environmental Factors

Data collection on environmental parameters supports animal welfare, health, and production. Heat stress is a common problem in the case of broiler (meat-type) chickens with intensive metabolism and high growth rates [

24]. The environmental temperature exceeding the birds’ thermoneutral zone hinders their heat release leading to health problems, decreased production, and food safety [

25]. When heat is unequally distributed inside the house, some areas may be colder. Chickens in those parts of the building gather to get warmth. Cold stress may weaken the immune system, cause digestive problems and lead to a decrease in growth rates negatively affecting productivity [

26]. Each broiler house should be equipped with a ventilation, heating and cooling system for controlling temperature, CO

2 and ammonia levels and relative humidity [

27]. Ventilation has a significant role in climate control inside livestock buildings maintaining the desired climatic conditions in every area of the houses [

28]. Continuous monitoring of air characteristics, ambient temperature, relative humidity, ventilation intensity, light intensity, dust content, CO

2 and NH

3 emissions inside buildings is crucial for maintaining animal health, preventing heat stress, and avoiding diseases [

29]. Hygiene is another critical aspect of environmental conditions and disease prevention. Robotic systems, through artificial intelligence, collect data on birds’ immune status and spread litter enhancers, vaccines, and disinfectants [

30,

31]. Stocking densities are also regulated to ensure welfare [

27]. High population densities and consumer awareness of animal feeding and housing conditions have led large-scale farms to adopt precision management tools to meet market and regulatory demands while maintaining production efficiency and profitability [

32,

33].

Many types of building simulation software available on the market use equations to control ventilation [

28]. Sensors gather information on temperature, light intensity, air composition, and relative humidity, and detect areas in the barn with inappropriate ventilation [

34]. The setting of the ventilation system is possible through the analysis of sensor data by artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms [

34]. Proper ventilation may lead to improved air quality, increased productivity, and reduced energy consumption [

35]. As well-known machine learning tools, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) are for the real-time or model-based prediction of airflow in livestock houses by controlling the heating and cooling systems and the mechanical ventilation through windows. The operation of the model may be challenging in the case of large flock sizes (thousands of animals) and a high number of operable windows [

28]. Sensors and sonic anemometers provide autonomous 2-dimensional data collection on climate conditions, air composition, bird distribution, and activity [

15,

16]. Multi-purpose robots measure air composition, light intensity, noise level, and litter quality [

16], sanitise broiler houses [

36] while turning and aerating the litter to reduce pathogen numbers and foot problems [

16].

3. Precision Tools for Assessing the Behaviour, Welfare and Health of Birds

3.1. Sound Analysis

Animals use sounds to communicate their physical and emotional states, establish social relationships, and signal stress. Chickens can emit 30 types of sounds [

37], with vocalisations indicating readiness for breeding, pain, stress, or need [

19]. Changes in vocalisation often reflect physiological and behavioural changes [

38], with most signals showing certain patterns that express the motivation of the individuals [

39]. For example, tonal sounds are associated with fear, while harsh ones indicate aggression [

40]. Vocalisations vary depending on the threats’ origin and birds’ motivations [

41]. In the case of food reward, chickens can express calls with different frequencies and rates based on the food type [

42]. In this respect, animal sound as a form of communication carries information encoded in the amplitude, frequency, duration, rate, and energy distribution of the voice [

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. The vocalisation of animals in response to environmental stimuli depends on both the type of environmental effects and the individuals’ perception (i.e., inner emotional state) [

37]. Sound analysis is a common practice in poultry systems to assess welfare and health [

37] and may also be applied for day-old sex and genetic strain identification [

48]. The development of sound-based systems may be a promising tool for detecting the symptoms of avian influenza or other respiratory diseases [

49]. Bio-acoustics are used to perceive and evaluate coughs in a real-time, non-invasive manner by their resonance [

50,

51].

Neural network pattern recognition identifies chickens infected by

Clostridium perfringens type A with accuracies between 66.6% and 100% [

19]. The neural network differentiate between healthy and unhealthy chickens based on acoustic signals, with feature extraction supporting that healthy individuals show more intensive and uniform vocalisation compared to unhealthy ones [

19]. Sound analysis of broiler chicks by noise frequency and amplitude spectrums using audio editing software informs us about birds’ thermal conditions and well-being [

52]. Higher vocalisation frequency was associated with higher chick density, indicating lower-than-optimal temperature, while increased vocalisation amplitude was related to lower chick density, showing that the temperature was within the comfort range of birds [

52]. Vocalisation frequency changes during incubation stages are detectable by electret microphones and algorithms [

53]. Using an electret microphone and an algorithm developed by audio software based on the sound of the developing chicken embryos, it is possible to determine the time of internal pipping. The algorithm detects when 93-98% of chicks enter the internal pipping stage, enabling the reduction of the hatching window and resulting in lower chick mortality [

53].

3.2. Image and Video Analysis

The intensive growth of chickens leads to a decrease in locomotion and physical activities [

54], with reduced activity frequently being a sign of foot problems (i.e., foot pad dermatitis, hock burn) caused by fast growth and poor litter quality, posing a common problem in broiler production [

55,

56]. The ulcers are painful and decrease locomotor abilities, reducing feed and water intake, resulting in weight loss [

57].

3D-Vision Monitoring, Deep Learning and Neural Networks

Artificial neural networks, machine vision and 3D computer vision have been widely used for the weight monitoring of broiler chickens based on image analysis. Amraei et al. [

58] applied machine vision and artificial neural network for the estimation of broiler chicken body weight from 1 to 42 days of age. Images were taken two times daily and weight estimation was performed by the Levenberg-Marquardt, gradient descent, Bayesian regulation and scaled conjugate gradient algorithms. Bayesian regulation algorithm was proved to have the highest reliability (R=0.98). However, according to Peng, the method provides only approximate measurements with errors around 50 g. Also, small changes are difficult to track in real time, and bird identification and the determination of feed intake simultaneously are technically challenging [

59].

A 3D-vision monitoring system supplemented with algorithms may be an essential, non-invasive, and non-intrusive tool for broiler gait score and lameness assessment, providing 93% accuracy [

17]. RFID (Radio Frequency Identification Devices) tags fixed on the back of chickens in a backpack help to track the locomotion and behavioural activity of birds [

61], although the expensive nature and sensor inaccuracy of these devices imply a need for further development [

12].

Deep neural networks such as Single-shot MultiBox detector (SSD), feature fusion single-shot MultiBox detector (FFSSD) or their improved versions with classification models of InceptionV3 and VGG16 determine the health status of birds [

61], although their disadvantage is the limitation in the number of animals per image and the image size. Digital image processing methods and several deep learning algorithms (i.e., R-FCN, R-CNN (constructed convolutional neural network), YOLO-V3, etc.) help to detect the health status of broilers [

63,

64], with accuracies between 84% and 100%. However, due to the high similarity of the shape of healthy and dead chickens, the recognition of dead ones is challenging and may affect the precision of classification [

64]. Collins [

65] investigated the correlations between stocking densities, social relationships and the behaviour of broiler chickens using video and path analyses to track the birds’ movements. His findings indicated that stocking density had a significant effect on individual behaviour.

Optical Flow Analysis and Linear Models

Optical flow analysis enables the continuous evaluation of bird locomotion by assessing the velocity of change in the brightness of image pixels, indicating leg problems without further tools and sensors [

66]. Based on camera recordings, optical flow combined with the Bayesian regression model is a great tool for mortality, weight gain, foot pad dermatitis and hock burn estimation [

67]. Dawkins et al. [

66] established a negative correlation between the mean optical flow and the mortality of birds, also declaring that the skew and kurtosis of optical flow were positively correlated with welfare indices such as mortality (r= 0.42; r= 0.45), gait scores (r= 0.42; r= 0.48) and hock burns (r= 0.57; r= 0.56). Solid predictions were carried out as early as day 15 of life [

66]. Higher optical flow values were associated with increased activity (rsitting= -0.21; rwalking= 0.42). The optical flow analysis also indicated that the variance in chickens’ walking ability was higher in the flock with more uniform movements [

68]. The accuracy of the technology was not provided in the literature. Automatic precision tools such as image analysis and thermal imaging are time-saving, objective, and continuous methods that may be well-applied in foot health investigations [

16]. The optical flow analysis is an algorithm including activity, distribution, and activity/distribution indices [

71]. The basis of the calculations is a camera image of chickens containing segments and grids. To obtain zone occupation density as a distribution indicator, the areas of the segmented chickens and the grid are compared. In the case of the activity index, the regions of active and segmented chickens are compared [

69]. The activity/distribution index is calculated by dividing the size of zones having average flock activity within a range of 25% with the zone number [

68]. Strong correlations were established between the predicted and observed gait scores based on the optical data, ranging between 0.85 and 0.97. This technique provides up-to-date information on bird health (i.e., gait scores) at an early age, before the appearance of symptoms in a cost- and labour-effective manner [

66,

67,

68]. The algorithm applied in the study was an initial form of individual gait score assessment by precision methods, implying a need for further development and validation.

A remote monitoring system operating with three cameras provides continuous data collection on population densities, bird activity, and distribution analysis. The system applies zones and pixels for activity and distribution index calculations [

18]. The behaviour and welfare of birds may be well-estimated by this method, focusing especially on the ratio of chickens visiting the feeders and drinkers [

18]. The system is appropriate also to determine the correlation between the activity and lameness of broiler chickens based on the gait scores [

2]. However, it should be taken into account that correct definitions should be provided for data classification (i.e., eating or drinking birds) for the right and precise application of the model [

18]. The environment of the observed zone should also be analysed [

18]. The application of force plates should inform us about the gait health of broilers [

70,

71], however, the results are questionable, inaccurate, and statistically insignificant in many cases. For example, in the experiment of Corr et al. [

70], birds with higher growth rates had lower speeds and thus ground reaction force, however, it was not related to lameness or other gait problems. In the study of Silvera et al. [

2], for the prediction of gait score measures, the baseline activity, the amplitude (moving away from the observer), time to return to baseline activities, and average activity after were used as variables. The amplitude was related to the walking ability and it was also reliable for the prediction of the relationship between humans and chickens [

2]. Dynamic linear models (DLM) based on video image analysis are suitable for the evaluation of broiler chicken activity at a given age and life period [

71]. Variations and deviations from normal activity (outliers) may be detected by this automatic monitoring system using filters. Thus the farmer can be notified to take action in the case of unexpected problems (i.e., sudden, detrimental changes in the temperature or relative humidity) to improve animal welfare [

72].

Thermal Imaging

Thermal imaging serves as the basis of optical flow and behaviour analyses in bird flocks [

16] and is also a useful way to optimize the heating and ventilation of broiler houses [

73]. There are two main methods for measuring body temperature: contact and non-contact [

74]. Contact devices may cause stress to the birds and do not support the concept of animal welfare [

75], so these technologies are not mentioned in the manuscript. Non-contact methods, such as infrared thermal imaging cameras, are non-invasive techniques that can measure body surface temperature and are frequently applied in the identification of pathological changes and symptoms [

75,

76]. Infrared cameras used in thermal imaging measure the infrared radiation (wavelengths) of a surface [

77]. By using the Stefan-Boltzmann equation (R=εσT

4), wavelengths are converted into infrared temperatures in Kelvins. Infrared temperature can be expressed as colours or pixels and shows the temperature distribution on the body surface described in a thermogram [

77,

78]. This thermal map can be used for the early detection and prediction of infections [

79] and plays a significant role in the physiological and diagnostic research of mammals, birds, and humans [

80,

81]. However, the system is rarely used for poultry due to their small body size and feathers [

82]. Nääs et al. [

83] used thermal imaging technology to estimate thermal comfort in broiler chickens. By applying video recordings taken in a climatic chamber and algorithms, the analysis of behaviour may serve as a significant welfare indicator in response to the climatic environment. Thermal cameras of multi-purpose robots, combined with artificial intelligence, measure the composition of faeces for the detection of diarrhoea. Data are uploaded to a cloud and can be extracted to the computer or forwarded to smartphones. The inbuilt maps help to direct the farmer to problematic areas by providing notification sounds and signs [

20]. Multi-purpose robots can collect dead birds by distinguishing between live and dead individuals and for detecting wet parts in the litter using infrared thermal imaging [

16]. The accuracy and effectiveness of the activity are not mentioned in the literature.

4. Tools for the Precision Feeding and Growth Estimation of Broiler Chickens

The Monitoring of Water and Feed Intake

Feed constitutes 70-80% of poultry production costs, making real-time control of inputs crucial [

84]. Precision feeding includes the accurate measurement and distribution of the delivered feed quantity adjusted to the age and breeding purpose of birds. The time and frequency of feeding are also determined but mainly in the case of broiler breeders. Feed intake and feed conversion ratio are calculated as well [

85]. Precision feeding enables uniform flock body weights and increases cost-efficiency [

86].

Initially, electronic scales and flow meters fixed on water pipes and troughs were used to measure feed and water consumption [

87]. Nowadays, RFID systems are applied for more accurate monitoring of individual feed intake in poultry [

88]. Load cell scales and water meters in each row or the whole house may be used to estimate feed and water consumption. These simple, real-time tools help detect the health status of birds and any technological and feed quality problems [

89]. Optical flow analysis combined with the Bayesian regression model may also be well-applicable for the estimation of water and feed consumption of birds [

67]. Problems with the operation of feeder lines can be controlled by computer vision based on the distribution index of broiler chickens [

94]. A lower distribution index is observed in the case of limited access to the feeder. The accuracy of the system is 95.24% expressing a high reliability. There is no contradiction mentioned in the literature questioning the usability of the technology [

90]. Metabolic robots are effective tools in improving the FCR (Food Conversion Ratio) of birds by adjusting feed doses according to the bird’s specific needs at a given age or development phase [

91]. The robots are operated by solar energy, wireless, easily installable, self-monitoring, and provide continuous, real-time information about the amount of feed stored in the silos enabling the control of feed intake [

12]. Opportunities and challenges are not available. Drinkers are observed with the classical camera system of multipurpose robots to avoid excessive water drippings [

20]. The individual feed intake of broilers can be in-vitro measured by sound analysis [

92]. Feed quantity is estimated by a weighing system with a balance placed underneath the feeder. Video image recordings with webcams are used to measure pecking frequency. Electret microphones attached to the trough are used for the detection of pecking noise and the preparation of the pecking algorithm. Algorithms are validated by computer vision technology, with an accuracy of 93% [

93].

The Monitoring of Growth Intensity

The weight gain of birds indicates the economic efficiency of farming. Data collection on chicken body weight may inform us about the uniformity of chickens in growth intensity, body weight, feed conversion ratio and health condition [

21]. According to Wang et al. [

18], individual monitoring of broiler chickens’ growth can be conducted based on RFID identification and electronic weighing. However, the authors note that the disadvantage of this system is the position of the tags on the chicken’s body, which causes stress for them, resulting in unreliable results [

22]. Growth models are used for the estimation of growth intensity and nutrient requirements of chickens considering feed composition and environmental conditions [934]. Allometric growth equations are also calculated [

94]

, feed formulator and economic optimizer are implemented in the model enabling economic feed formulation [

93]. Apart from growth models, a precision feeding system has been developed recently in Canada for broiler breeders. In this case, a feeding station is applied for individual feed delivery depending on the difference between the real-time and target body weight of birds [

85]. The future system will enable nutrient specifications based on the individual needs of breeders [

85]. A novel way of weight monitoring in broiler chickens is the one combined with the analysis of perching behaviour. Wang et al. [

22] investigated the accuracy of image-assisted rod platform weighing system for the determination of broiler chicken weight. The perching habit of chickens was used as the basis for weighing. A strain-gauged sensor fixed to the bottom of the rod was responsible for weight monitoring. A printed circuit board read the output information of the sensors and forwarded it to the computer [

22]. The automated weighing system provided accuracies within 2% for average weight and 1.5% for flock uniformity which is more precise compared to manual ones of 0-5% [

22].

Several authors revealed associations between sound frequency and the weight of birds as an innovative approach to weight monitoring [

23,

95]. Fontana et al. [

23] investigated the accuracy of weight analysis by the sound of birds and established a strong correlation (r= 0.96) between the expected and observed weights. Their findings were in consistency with that of Bowling et al. [

95] who found an inverse relationship between the body size and vocalisation frequency of birds during the production cycle. Higher frequencies at younger ages indicated lower weights and vice versa [

95]. No study has questioned the accuracy of sound analysis, so it can be a reliable method of weight determination. Initial forms of image analysis, first applied to estimate live weight and carcass characteristics in swine, date back to the 1980s-1990s [

96]. These techniques provided more reliable measurements than manual ones [

9]. De Wet et al. [

21] were the first to report on the use of image analysis systems in broiler production. In their study, the body surface area and dimensions captured from a top view were the basis for determining chicken live weight. A Sobel-Feldman operator was used for image processing, and regression analysis was applied to establish the relationships between body dimensions and live weights [

21]. Results showed the reliability of the method to be lower (89%) compared to the same analysis conducted with pigs (95%). The locomotion of chickens resulted in alterations in their orientation and posture, leading to inconsistent variations between individuals [

21]. Mollah et al. [

97] used the body contour of birds for weight monitoring. Measurements were based on a digital camera placed 1 m high above the bird to be captured. With optimal light intensity, its body contour became easily visible and was displayed as the average of ten image replicates [

98]. The number of pixels in the body surface area was calculated by an image processing software, and data were used in the estimation of body weight [

98]. Estimations had 0.04% and 16.47% errors regarding surface-area pixels. Up to 35 days of age, calculations did not differ from the manual observations (P>0.05). However, according to the authors, the system needs development to improve its practical application [

98]. A novel method of broiler weight determination is dynamic weighing [

59]. The system provides individual monitoring of feed intake and growth by integrating precision feeding and weighing technology, RFID reading module, analogue circuits, digital filtering, and calculation equations. However, the accuracy is only 2.16 g in contrast to the 0.82 g weighing accuracy of static weighing [

59].

The use of light as a point laser to raise the curiosity of chickens may improve bird activity and feed consumption resulting in higher growth rates [

99].

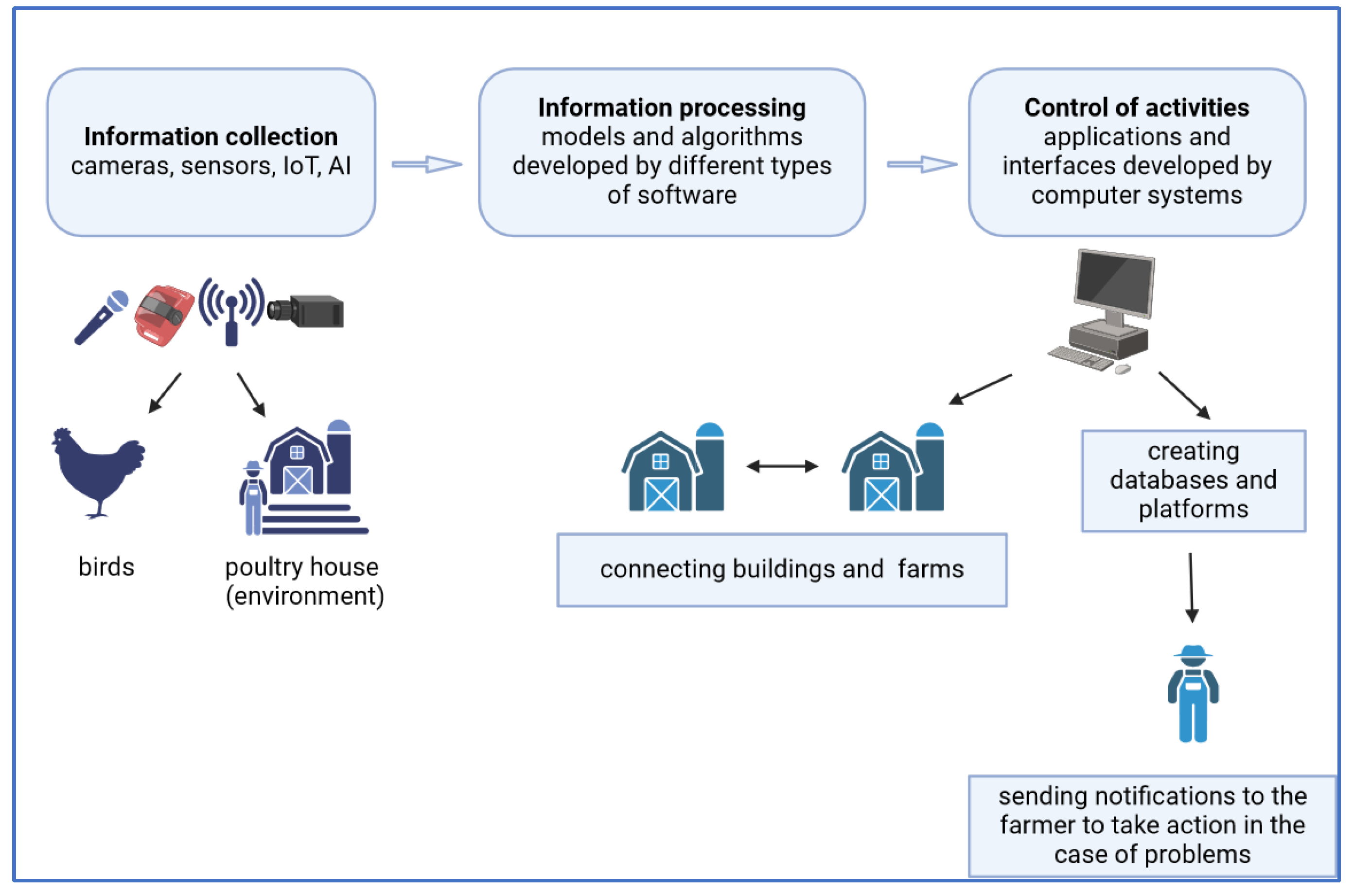

The process of data perception, transformation and activity control in general is presented in

Figure 1.

5. Limitations of PLF Technologies

Before applying precision technologies, we should be aware of possible problems and limitations that may arise during the operation of systems and devices. This may help us in planning, decision-making, and problem-solving.

According to Morrone [

100], we should face an almost equal number of advantages and disadvantages of PLF systems. Technical failures and malfunctioning may emerge caused by power cuts, hardware breakdowns, tag losses, etc [

101]. It can be a great challenge for farms that are highly dependent on PLF tools because in most cases, they are unable to solve the problems on their own and need to ask for specialists [

101]. Devices may negatively affect animal behaviour and disturb animals causing stress for them. Also, they may pose a threat to pathogen transmission [

102]. Algorithms may provide less reliable results under real farm conditions compared to in-vitro analyses. This is mainly due to the poor quality and low variability of training data [

103]. Many tools are only applied under experimental conditions, however, they could be used also in commercial circumstances [

12]. Often, there is no correspondence and agreement on the intentions of researchers, developers, and manufacturers in the scope of indicators and parameters to be measured when assessing the applicability of PLF tools (i.e., lack of information on production efficiency) [

104]. Under- or overreliance on PLF technology can also pose a threat to animal welfare and farm productivity which is often caused by the lack of knowledge of users on the usability and limitations of PLF devices [

102]. PLF systems may result in a decrease in human-animal contact, and interactions are mainly limited to the less favourable ones (i.e., vaccination, transportation, etc.) which pose stress to the animals [

105]. The application of PLF tools may reduce the need for human skills and efforts to take care of the animals risking the ability to notice problems and take action in the case of PLF system failures [

102]. Regarding farm levels, PLF technology cannot be profitably and easily operated on small-scale, extensive farms due to the poor technological background, too large areas to be covered, and the high production costs per animal [

101,

106]. Currently, the focus of PLF systems is more on production efficiency and economic aspects than on animal welfare which may diminish the moral status of animals in society [

107].

There is scarce information on the operational success and effectiveness of robots. It is the consequence of the limited number of experimental studies in this field and also the designer commercial companies are not willing to disclose data on these technologies [

64]. Moreover, poultry robots are also limited in functionality and applicability because most of them are designed for specific tasks [

36]. Multi-tasking abilities should be expanded by using advanced technologies and AI by facing various environmental conditions during navigation in the poultry house [

108]. Also, there is a need to develop an obstacle awareness system to improve real-time path planning and navigation [

64]. Social learning abilities of robots to improve and facilitate robot-animal interactions and future research objectives should focus on this field of challenges regarding animal welfare [

109].

6. Conclusions

The application of precision technology in agriculture and the poultry sector dates back to the 1980s when the first forms of digital image processing were initiated. Nowadays, with the rapid growth of information and computer technology, the scope and type of PLF tools are increasing. Modern technologies automatically detect the environmental parameters, poultry behaviour, health and welfare in a non-invasive, real-time manner. The activities involve mechanical (sensors, robots) and digital (computer systems and software) tools, as well as socio-economic factors such as education and technology adoption. Precision technologies also enhance decision-making processes in production management and reduce economic losses. Sensors can provide continuous and real-time data on environmental conditions (e.i. temperature, humidity, ventilation speed, CO2 and NH3 concentrations, etc.) that are forwarded to a system. Extracted data can be used for control and the farmer is alarmed in the case of problems to interfere. 3D vision monitoring and digital image processing methods with deep learning algorithms can detect lameness and diseases with high accuracies (from 84% to 100%). Multipurpose robots can measure many parameters in parallel which can be energy- and economic-friendly and helps to have a more exact view of production and welfare. The scope of recorded data by robots includes air composition, light intensity, noise level, and litter quality. Also, they can distinguish dead birds from live ones and measure the composition of faeces. Data on accuracies are not provided in the literature.

Besides their advantages, the application of PLF tools and technologies is reduced only to the experimental level, although, they could be used under commercial circumstances, too. Considering technical failures, problems with the reliability of provided data, the limitations in functionality and applicability of precision systems due to their specificity and differences in farm sizes, the following suggestions can be made for the future investigation and improvement of PLF technologies. Globalisation and the increasing need for animal products desire the integration of PLF and IoT technologies. Based on artificial intelligence, the operation of sensors, robots and other systems should be synchronised leading to a more effective data collection and process providing a concise overview of farm productivity. Tools should be connected to enable communication with each other and create a complex, reliable, precise background for farming. This also facilitates management decisions and the treatment of so-called “Big Data” [

111]. When designing and constructing PLF equipment, the ethics of sustainability should be considered, as well [112]. Considering the above-mentioned perspectives and possible objectives, the development of future precision livestock farms may be promoted hand in hand with the improvement of animal welfare and sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.D.B., Zs.V., and I.K.; writing-original draft preparation, L.D.B.; visualisation, L.D.B., I.K. and Zs.V.; supervision, I.K. and Zs.V.; review, editing, and commenting, L.D.B., I.K. and Zs.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The publication was supported by the University of Debrecen Program for Scientific Publication.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The publication was supported by The ÚNKP-23-4-I New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund and the University of Debrecen Program for Scientific Publication. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Professor Davey Jones (Bangor University, Wales) for reviewing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Henchion, M.; McCarthy, M.; Resconi, V.C.; Troy, D. Meat consumption: Trends and quality matters. Meat Sci 2014, 98, 3–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvera, G.A.M.; Hansson, H.; Saatkamp, H.W.; Blokhuis, H.J. Exploring the Economic Potential of Reducing Broiler Lameness. Br Poult Sci 2017, 58, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracke, M.B.M.; Hopster, H. Assessing the importance of natural behavior for animal welfare. J Agr Env Ethics 2006, 19, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitbarek, M. Livestock and livestock product trends by 2050: a review. Int J An Res 2019, 4, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, B.H.; Yang, L.; Zheng, S.S. Research progress on the application of information and intelligent equipment in animal husbandry in China. J China Agr Univ Inf Proc Agr 2018, 30, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Mollo, M.; Vendrametto, O.; Okano, M. Precision Livestock Tools to Improve Products and Processes in Broiler Production: A Review. Braz J Poult Sci 2009, 11, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraess, G.A.; Bench, C.J.; Tierney, K.B. Automated behavioural response assessment to a feeding event in two heritage chicken breeds. Appl Anim Beh Sci 2016, 179, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawkins, M.S.; Roberts, S.J.; Cain, R.J.; Nickson, T.; Donnelly, C.A. Early warning of footpad dermatitis and hockburn in broiler chicken flocks using optical flow, body weight and water consumption. Vet Rec, 2017, 180, 20–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharjan, P.; Liang, Y. Precision Livestock Farming: The Opportunities in Poultry Sector. J Agr Sci Techn 2020, 10, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathes, C.M.; Kristensen, H.H.; Aerts, J.M.; Berckmans, D. Is precision livestock farming an engineer’s daydream or nightmare, an animal’s friend or foe, and a farmer’s panacea or pitfall? Comput Electron Agric 2008, 64, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Goor, A.; Chitnis, P.; Kirk Baer, C. Precision livestock farming: National Institute of Food and Agriculture contributions and opportunities. In: Prec Livest Farm ’19. Eds: O’Brien, B., Hennessy, D., Shalloo, L. 9th European Conference on Precision Livestock Farming Cork, Ireland, 26-29 August 2019.

- Li, N.; Ren, Z.; Li, D.; Zeng, L. Review: Automated Techniques for Monitoring the Behaviour and Welfare of Broilers and Laying Hens: Towards the Goal of Precision Livestock Farming. Animal 2020, 14, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buller, H.; Blokhuis, H.; Lokhorst, K.; Silberberg, M.; Veissier, I. Animal Welfare Management in a Digital World. Animals, 10, 1779. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Cui, D.; Zhou, M.; Ying, Y. Information perception in modern poultry farming: A review. Comput Electron Agric, 2022, 199, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmers, T.G.M.; Dennis, I.C.; Norman, P.; Butler, M.; Clare, D. RoboChick: An autonomous roving platform for data collection in poultry buildings, operational parameters and bird behaviour. In: Prec Livest Farm ’19. Eds: O’Brien B, Hennessy D and Shalloo L. 9th European Conference on Precision Livestock FarmingCork, Ireland, 26-29 August 2019.

- Olejnik K, Popiela E, Opali’nski S. Emerging Precision Management Methods in Poultry Sector. Agriculture, 12, 718 2022. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A. Using 3D vision camera system to automatically assess the level of inactivity in broiler chickens. Comput Electron Agric, 135, 4-10, 2017. [CrossRef]

- De Montis A, Pinna A, Barra M, Vranken EV. Analysis of poultry eating and drinking behavior by software eYeNamic. J Agric Eng, 44, 2, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi M, Banakar A, Khazaee M, Soleimani MR. An intelligent procedure for the detection and classification of chickens infected by Clostridium perfringens based on their vocalization. Braz J of Poult Sci, 17, 537-544. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Hartung H, Lehr H, Rosés D, Mergeay M, van den Bossche J. ChickenBoy: a farmer assistance system for better animal welfare, health and farm productivity. Prec Livest Farm, 9, 2019.

- De Wet L, Vranken E, Chedad A, Jean-Marie A, Ceunen J, et al. Computer-assisted image analysis to quantify daily growth rates of broiler chickens. Br Poult Sci, 44, 4, 524–532, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Wang, K. , Pan, J., Rao, X., Yang, Y., Wang, F., Zheng, R., & Ying, Y. (2018). An image-assisted rod-platform weighing system for weight information sampling of broilers. Trans. ASABE, 61(2), 631-640. [CrossRef]

- Fontana I, Tullo E, Carpentier L, Berckmans D, Butterworth A, Vranken E, Norton T, Berckmans D, Guarino M. Sound analysis to model weight of broiler chickens. Poult Sci, 96, 11, 3938–3943, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Renaudeau D, Collin A, Yahav S, De Basilio V, Gourdine JL, Collier RJ. Adaptation to hot climate and strategies to alleviate heat stress in livestock production. Animal, 6, 5, 707–728, 2012. [CrossRef]

- He SP, Arowolo MA, Medrano RF, Li S, Yu QF, Chen JY, He JH. Impact of heat stress and nutritional interventions on poultry production. World’s Poult Sci 74, 647-664, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Corkery G, Ward S, Kenny C, Hemmingway P. Incorporating Smart Sensing Technologies into the Poultry Industry. J World’s Poult Res 3, 4, 106–128, 2013. ISSN 2322-455X.

- European Union Council Directive 2007/43/EC of 28 June 2007 Laying down Minimum Rules for the Protection of Chickens Kept for Meat Production. Off J Eur Un, 182, 19-28, 2007.

- Gautam KR, Rong L, Zhang G, Abkar M. Comparison of analysis methods for wind-driven cross ventilation through large openings. Build Environ, 154, 375-388, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Jones TA, Donnelly CA, Dawkins MS. Environmental and Management Factors Affecting the Welfare of Chickens on Commercial Farms in the United Kingdom and Denmark Stocked at Five Densities. Poult Sci, 84, 1155-1165, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Park, SO. Application strategy for sustainable livestock production with farm animal algorithms in response to climate change up to 2050: A review. Czech J An Sci, 67, 11, 425–441. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Patel H, Samad A, Hamza M, Muazzam A, Harahap MK. Role of Artificial Intelligence in Livestock and Poultry Farming. Sinkron, 7, 4, 2425–2429, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Meluzzi A, Sirri F. Welfare of Broiler Chickens. Ital J An Sci, 8, 161-173, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira VMOS, Francisco, NS, Belloni M, Aguirre GMZ, Caldara FR, et al. Infrared Thermography Applied to the Evaluation of Metabolic Heat Loss of Chicks Fed with Different Energy Densities. Braz J Poult Sci, 13, 113-118, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Taleb H, Mahrose K, Abdel-Halim, A, Kasem H, Ramadan G, Fouad A, Khafaga A, Khalifa NE, Kamal M, Salem, H, Alqhtani A, Swelum A, Arczewska-Wlosek A, Swiatkiewicz S, Abd El-Hack M. Using artificial intelligence to improve poultry productivity—a review. Ann Anim Sci, 1-25, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nääs IA, Romanini CEB, Neves DP, Nascimento GR, Verceliino RA. Broiler surface temperature distribution of 42-day-old chickens. Scient Agric, Pirac, 67, 5, 497–502, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Ren G, Lin T, Ying Y, Chowdhary G, Ting KC. Agricultural robotics applicable to poultry production: A review. Comput Electron Agric, 169, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Manteuffel G, Puppe B, Schon PC. Vocalization of farm animals as a measure of welfare. Appl Anim Behav Sci, 88, 163-182, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Weary DM, Fraser D. Calling by domestic piglets: reliable signals of need? Anim Behav, 50, 1047-1055, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Olczak K, Penar W, Nowicki J, Magiera A, Klocek C. The Role of Sound in Livestock Farming—Selected Aspects. Animals, 13, 14, 2307, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL. Meaning and emotion in animal vocalizations. Ann New York Acad Sci, 1000, 32-55, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Evans CS, Evans L. Chicken food calls are functionally referential. Anim Behav, 58, 2, 307–319, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Wauters AM, Richard-Yris MA, Pierre JS, Lunel C, Richard JP. Influence of Chicks and Food Quality on Food Calling in Broody Domestic Hens. Behav, 136, 7, 919–933, 1999. [CrossRef]

- Townsend SW, Charlton BD, Manser MB. Acoustic cues to identity and predator context in meerkat barks. Anim Behav, 94, 143-149, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Gustison ML, Townsend SW. A survey of the context and structure of high- and low-amplitude calls in mammals. Anim Behav, 105, 281-288, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Reichard DG, Anderson RC. Why signal softly? The structure, function and evolutionary significance of low-amplitude signals. Anim Behav, 105, 253-265, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Clay Z, Smith CL, Blumstein DT. Food-associated vocalizations in mammals and birds: What do these calls mean? Anim Behav, 83, 2, 323–330, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Dentressangle F, Aubin T, Mathevon N. Males use time whereas females prefer harmony: Individual call recognition in the dimorphic blue-footed booby. Anim Behav, 84, 413-420, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Pereira EM, Naas ID, Garcia RG. Vocalization of broilers can be used to identify their sex and genetic strain. Engen Agric, 35, 192-196, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Carpentier L, Vranken E, Berckmans D, Paeshuyse J, Norton T. Development of sound-based poultry health monitoring tool for automated sneeze detection. Comput Electron Agric, 162, 573-581, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Klaus-Gerhard H, Hemp C, Chunxiang L, Marianne V. Taxonomic, bioacoustic and faunistic data on a collection of Tettigonioidea from Eastern Congo (Insecta: Orthoptera). Zootaxa, 3785, 343-376, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari S, Silva M, Guarino M, Berckmans D. Monitoring of swarming sounds in bee hives for early detection of the swarming period. Comput Electron Agric, 64, 1, 72–77, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Moural DJ, Nääs IA, Alves ECS, Carvalho TMR, Vale MM, et al. Noise analysis to evaluate chick thermal comfort. Scient Agric, 65, 438-443, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Exadaktylos V, Silva M, Berckmans D. Real-time analysis of chicken embryo sounds to monitor different incubation stages. Comput Electron Agric, 75, 321-326, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Aydin A, Cangar O, Ozcan, SE, Bahr, C, Berckmans, D. Application of a Fully Automatic Analysis Tool to Assess the Activity of Broiler Chickens with Different Gait Scores. Comput Electron Agric, 73, 194-199, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann G, Ammon C, Volkamer L, Sürie C, Radko D. Sensor-Based Monitoring of the Prevalence and Severity of Foot Pad Dermatitis in Broiler Chickens. Brit Poult Sci, 54, 553-561, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Haslam SM, Knowles TG, Brown SN, Wilkins LJ, Kestin SC, Warriss PD and Nicol CJ. Factors Affecting the Prevalence of Foot Pad Dermatitis, Hock Burn and Breast Burn in Broiler Chicken. Brit Poult Sci, 48, 264-275, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Bilgili SF, Hess JB, Blake JP, Macklin KS, Saenmahayak B, et al. Influence of Bedding Material on Footpad Dermatitis in Broiler Chickens. J Appl Poult Res, 18, 583-589, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Amraei S, Abdanan MS, Salari S. Broiler weight estimation based on machine vision and artificial neural network. Br Poult Sci, 58, 2, 200–205, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Peng Y, Zeng Z, Lv E, He X, Zeng B, Wu F, Guo J, Li Z. A Real-Time Automated System for Monitoring Individual Feed Intake and Body Weight of Group-Housed Young Chickens. Appl Sci 12, 23, 12339. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Stadig LM, Rodenburg TB, Ampe B, Reubens B, Tuyttens FAM. An Automated Positioning System for Monitoring Chickens’ Location: Effects of Wearing a Backpack on Behaviour, Leg Health and Production. Appl Anim Behav Sci, 198, 83-88, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang X, Zhang T. Detection of sick broilers by digital image processing and deep learning. Biosyst Engin, 179, 106-116, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Dai J, Li Y, He K, Sun J. R-FCN: Object detection via region-based fully convolutional networks. Arxiv, Corn Univ, 1-11, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Lin TY, Goyal P, Girshick R, He K, Dollar P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. Proc IEEE Intern Conf Comput Vis, 2999-3007, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ozenturk U, Chen Z, Jamone L, Versace E. Robotics for poultry farming: challenges and opportunities. Corr, abs/2311.05069, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. Non-intrusive tracking of commercial broiler chickens in situ at different stocking densities. Appl Anim Behav Sci, 112, 94-105, 2008. 10.1016/j.applanim.2007.08.009.

- Dawkins MS, Cain R, Roberts SJ. Optical flow, flock behaviour and chicken welfare. Anim Behav Sci, 84, 219-223, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Roberts SJ, Cain R, Dawkins MS. Prediction of welfare outcomes for broiler chickens using Bayesian regression on continuous optical flow data. J Royal Soc Interf, 9, 3436-3443, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Dawkins MS, Lee HJ, Waitt CD, Roberts SJ. Optical Flow Patterns in Broiler Chicken Flocks as Automated Measures of Behaviour and Gait. Appl Anim Behav Sci, 119, 203-209, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Eijk JAJ, Oleksiy G, Schulte-Landwehr J, Giersberg MF, Jacobs L, et al. Individuality of a group: detailed walking ability analysis of broiler flocks using optical flow approach. Smart Agricult Techn, 5, 1-8, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Corr SA, McCorquodale C, McDonald J, Gentle M, McGovern R. A force plate study of avian gait. J Biomech, 40, 2037-2043, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Kristensen HH, Cornou C. Automatic detection of deviations in activity levels in groups of broiler chickens—A pilot study. Biosyst Eng, 109, 369-376, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Roush WB, Tomiyama K, Garnaoui KH, D’Alfonso TH, Cravener TL. Kalman filter and an example of its use to detect changes in poultry production responses. Comput Electron Agric, 6, 347-356, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Baracho MS, Naas IA, Nachimento GR, Cassiano JA, Oliveira KR. Surface Temperature Distribution in Broiler Houses. Braz J Poult Sci, 13, 3, 188–182, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Shiomi M, Hagita N. Finding a person with a wearable acceleration sensor using a 3D position tracking system in daily environments. Adv Robot, 2, 23, 1563–1574, 2015. [CrossRef]

- McManus C, Tanure B, Peripolli V, Seixas L, Fischer V, et al. Infrared thermography in animal production: An overview. Comput Electron Agric, 123, 10-16, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Lu MZ, He J, Chen C, Okinda C, Shen M, Liu L, Yao W, Norton T and Berckmans D. An automatic ear base temperature extraction method for top view piglet thermal image. Comput Electron Agric, 155, 339-347, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yahav S and Giloh, M. Infrared Thermography—Applications in Poultry Biological Research. In: Infrared Thermography Eds.: Prakash RV. In Tech Open Publisher, 1-236, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Tessier M, Tremblay DD, Klopfenstein C, Beauchamp G, Boulianne M. Abdominal Skin Temperature Variation In Healthy Broiler Chickens As Determined By Thermography. Poult Sci, 82, 5, 846–849, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer AL, Nigel C, Tessaro S, Deregt D, Desroches G, et al. Early detection and prediction of infection using infrared thermography. Can J Anim Sci, 84, 73-80. 2004. [CrossRef]

- Klir JJ, Heath JE. An infrared thermographic study of surface temperature in relation to thermal stress in three species of foxes: the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), arctic fox (Alopex lagopus), and kit fox (Vulpes macrotis). Phys Zool, 65, 1011-1021, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Teunissen LPJ Daanen, HAM. Infrared thermal imaging of the inner canthus of the eye as an estimator of body core temperature. J Med Eng Techn, 35, 3-4, 134-138, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Li P, Lu H, Wang F, Zaho S, Wang N. Detection of Sick Laying Hens by Infrared Thermal Imaging and Deep learning. J Phys: Conf Ser. IOP Publishing, 1-8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nääs IA, Romanini CEB, Neves DP, Nascimento GR, Verceliino RA. Broiler surface temperature distribution of 42-day-old chickens. Scient Agric, Pirac, 67, 5, 497–502, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Olugbenga SO, Abayomi OO, Oluseye AA, Taiwo AT. Optimized nutrients diet formulation of broiler poultry rations in Nigeria using linear programming. J Nutr & Food Sci, 14, 1, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Moss A, Chrystal P, Cadogan D, Wilkinson S, Crowley T, Choct M. Precision feeding and precision nutrition: A paradigm shift in broiler feed formulation?. Anim Biosci 34, 3, 354–362, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zuidhof M, Fedorak M, Ouellette C, Wenger I. Precision feeding: Innovative management of broiler breeder feed intake and flock uniformity. Poult Sci 96, 7, 2254–2263, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Xin H, Berry IL, Barton T, Tabler GT. Feeding and drinking patterns of broilers subjected to different feeding and lighting programs. J Appl Poult Res, 2, 4, 365–372, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Zhao Y, Hailey R, Zhang N, Liang Y, et al. An ultra-high frequency radio frequency identification system for studying individual feeding and drinking behaviors of group-housed broilers. Animal, 13, 2060-2069, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Xin H, Liu K. Precision Livestock Farming in Egg Production. Anim Front, 7, 24-31, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kashiha, Mohammadamin & Pluk, Arno & Bahr, C. & Vranken, Erik & Berckmans, Daniel. (2013). Development of an early warning system for a broiler house using computer vision. Biosystems Engineering. 116. 36-45. [CrossRef]

- Pitla S, Bajwa S, Bhusal S, Brumm T, Brown-Brandl TM. Ground and Aerial Robots for Agricultural Production: Opportunities and Challenges. Counc Agricult Sci Techn (CAST): Ames, IA, USA, 70, 2020.

- Aydin A, Bahr C, Viazzi S, Exadaktylos V, Buyse J and Berckmans D. A novel method to automatically measure the feed intake of broiler chickens by sound technology. Comput Electron Agric, 101, 17-23, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Reis MP, Gous RM, Hauschild L, Sakomura NK. Evaluation of a mechanistic model that estimates feed intake, growth and body composition, nutrient requirements, and optimum economic response of broilers. animal 17, 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo JM, Reis, MP, Gous RM, Dorigam, JCP, Leme, BB, Sakomura NK. Response of broilers to dietary balanced protein. 1. Feed intake and growth. Anim Prod Sci, 61, 1425-1434, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bowling D, Garcia M, Dunn J, Ruprecht R, Stewart A, Frommolt KH, Fitch W. Body size and vocalization in primates and carnivores. Sci. Rep., 7, 41070, 2017.

- Ali, NM. Variance in pig’s dimensions as measured by image analysis. Proceedings of the Fourth International Livestock Environment Symposium, Coventry, UK. ASAE Publication 03-93, ASAE, St. Joseph, MI 151-158, 1993.

- Turner MJ, Gurney P, Crowther JS, Sharp JR. An automatic weighing system for poultry. J Agric Eng Res, 29, 1, 17–24, 1984. [CrossRef]

- Mollah MBR, Hasan MA, Salam MA, Ali MA. Digital image analysis to estimate the live weight of broiler. Comput Electron Agric, 72, 48-52, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Meyer MM, Johnson AK, Bobeck EA. A Novel Environmental Enrichment Device Increased Physical Activity and Walking Distance in Broilers. Poult Sci, 99, 48-60, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Morrone S, Dimauro C, Gambella F, Cappai MG. Industry 4.0 and Precision Livestock Farming (PLF): An up to Date Overview across Animal Productions. Sensors, 22, 4319, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tuyttens FAM, Molento CFM, Benaissa S. Twelve Threats of Precision Livestock Farming (PLF) for Animal Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci., 9, 889623, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hovinen M, Pyörälä S. Invited review: udder health of dairy cows in automatic milking. J Dairy Sci. 94, 547-562, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Burton RJF, Peoples S, Cooper MH. Building cowshed culture: a cultural perspective on the promotion of stockmanship and animal welfare on dairy farms. J Rural Stud. 28, 174-87, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Stygar AH, Gomez Y, Berteselli G V, Dalla Costa E, Canali E, Niemi JK, Llonch P, Pastell M. A Systematic Review on Commercially Available and Validated Sensor Technologies for Welfare Assessment of Dairy Cattle. Front Vet Sci. 8, 634338, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Schillings J, Bennett R, Rose DC. Exploring the potential of precision livestock farming technologies to help address farm animal welfare. Front Anim Sci. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gargiulo JI, Eastwood CR, Garcia SC, Lyons NA. Dairy farmers with larger herd sizes adopt more precision dairy technologies. J Dairy Sci. 101, 5466-73, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Binngießer J, Randler C. Association of the environmental attitudes “Preservation” and “Utilization” with pro-animal attitudes. Int J Environ Sci Educ. 10, 477-492, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Alatise MB, Hancke, GP. A Review on Challenges of Autonomous Mobile Robot and Sensor Fusion Methods. IEEE Access, 8, 39830-39846, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dennis, L. , Fisher, M. Verifiable Autonomy and Responsible Robotics. In: Cavalcanti, A., Dongol, B., Hierons, R., Timmis, J., Woodcock, J. (eds) Software Engineering for Robotics. Springer, Cham. 189-217, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Neethirajan, S.; Kemp, B. Digital livestock farming. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2021, 32, 100408.

- Garcia, R.; Aguilar, J.; Toro, M.; Pinto, A.; Rodriguez, P. A systematic literature review on the use of machine learning in precision livestock farming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).