1. Introduction

The death of a child is a profound loss with far-reaching emotional and psychological consequences for families and healthcare professionals (HCPs) alike [

1,

2,

3]. Pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) often witness such tragedies, particularly in cases involving complex congenital heart disease (CCHD). These settings demand a unique integration of pediatric palliative care (PPC) to support both the child and their family during end-of-life (EoL) care [

4,

5].

PPC services are pivotal in enhancing EoL care, alleviating distress, and improving outcomes for children, families, and HCPs [

1]. Effective PPC relies on honest, compassionate, and ongoing communication tailored to families’ cultural, emotional, and spiritual needs. Rather than a single event, this communication unfolds over time through multiple stages [

1,

6]. Conducted in private, supportive settings, these discussions help families gradually comprehend their child’s prognosis, establish care goals, and navigate emotional and practical caregiving challenges. The iterative process fosters trust and supports families’ adaptation as the child’s condition evolves. Advance care planning (ACP) complements this process by enabling families to articulate preferences for treatment, symptoms management, and the location of EoL care, prioritizing quality of life [

7].

CCHDs are a leading cause of infant mortality in intensive care settings [

8]. Most deaths occur during infancy, often following prolonged hospital stays and invasive procedures, which intensify parental grief. Previous findings from our group revealed that among children with severe CCHD who died in our institution, 97% passed away in the PICU setting, frequently intubated and sedated, with only 23% having a parent present at the bedside during EoL [

9]. Moreover, over 60% of parents identified minimizing their child’s suffering as the primary therapeutic goal, yet many recognized the absence of survival chances only shortly before their child’s death. These data highlight significant gaps in communication and decision-making at EoL, which contribute to parental distress. Understanding the experiences and perceptions of parents regarding their child’s EoL care is therefore essential for improving clinical practices and support systems [

9,

10,

11].

Qualitative research is essential for exploring the emotional, social, and spiritual aspects of care as it provides valuable insights into communication issues, family dynamics, and bereavement experiences. Despite recent growth, qualitative research in this field remains insufficient to fully capture the unique challenges families face, particularly regarding complex decision-making [

12,

13,

14].

To address this gap, we analyzed the experiences of bereaved parents whose children died of CCHD at a tertiary cardiac care center (Paediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Units of the University of Padova). By highlighting both the child’s and family’s needs during their most vulnerable moments, this qualitative analysis contributes to the evolving development of family-centered practices for CCHD at the EoL in the PICU.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

Bereaved parents of children (<18 years) who died from CCHD following major cardiac surgery at our tertiary cardiac care center (Paediatric Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery Units of the University of Padova, Italy) between January 1st 2009 and December 31st 2012 were invited to participate. Exclusion criteria included non fully proficient Italian speakers, refusal to participate, or ongoing litigation with the hospital. Parents were contacted by the child’s cardiovascular surgeon, who explained the study and sought consent. Only the parent identified as the primary caregiver was interviewed.

The study was conducted within the framework of a pediatric tertiary hospital where a PPC service has been operational since 2003. This service provides comprehensive PPC across inpatient, outpatient, and community settings, with 24/7 access to consultations by physicians and advanced practice nurses.

The Hospital Ethics Committee approved the study design; the need for parental consent was waived for the revision of the clinical charts. Parents and HCPs voluntarily decided to participate to the study. Medical records were reviewed for demographic and clinical data, including the time between the child’s death and the interview.

2.2. Study Context

This study is part of a larger project aimed at improving the quality of end-of-life (EoL) care for children with CCHD. The overarching research involved a cross-sectional, questionnaire-based study conducted through semi-structured, telephone-administered interviews [

9]. This paper specifically focuses on data derived from five open-ended questions in the original questionnaire and spontaneous comments provided by parents during interviews (see

Table 1). The results of the retrospective medical record review are reported on the previously published article [

9].

2.3. Qualitative Approach

This study used phenomenological analysis, a qualitative approach ideal for exploring participants’ lived experiences. The methodology focuses on understanding complex phenomena from subjective perspectives without relying on pre-existing theories. This approach was employed to examine the experiences of parents who endured the traumatic loss of a child due to CCHD.

To ensure sensitivity and minimize bias, interviewers underwent specialized training by a psychologist, including role-playing exercises and techniques to bracket personal assumptions. Five semi-structured interview questions were collaboratively designed, with input from external contributors to ensure neutrality (

Table 1).

Data were collected through telephone-administered interviews, capturing responses to open-ended questions and spontaneous reflections. Transcripts were reviewed verbatim, preserving participants’ linguistic authenticity. Data were analyzed inductively, identifying recurring themes and clusters. Two researchers independently coded the data, resolving discrepancies through face-to-face discussions with oversight from a third investigator.

2.4. Analytical Process

The analysis adhered to Colaizzi’s iterative method [

15], ensuring thematic coherence and data saturation. Spontaneous comments were analyzed within a phenomenological framework, prioritizing participants’ linguistic specificity to ensure fidelity to their perspectives. Thematic content analysis, as outlined by Braun and Clarke [

16], was supported by manual coding to organize data and ensure systematic derivation of themes and subthemes.

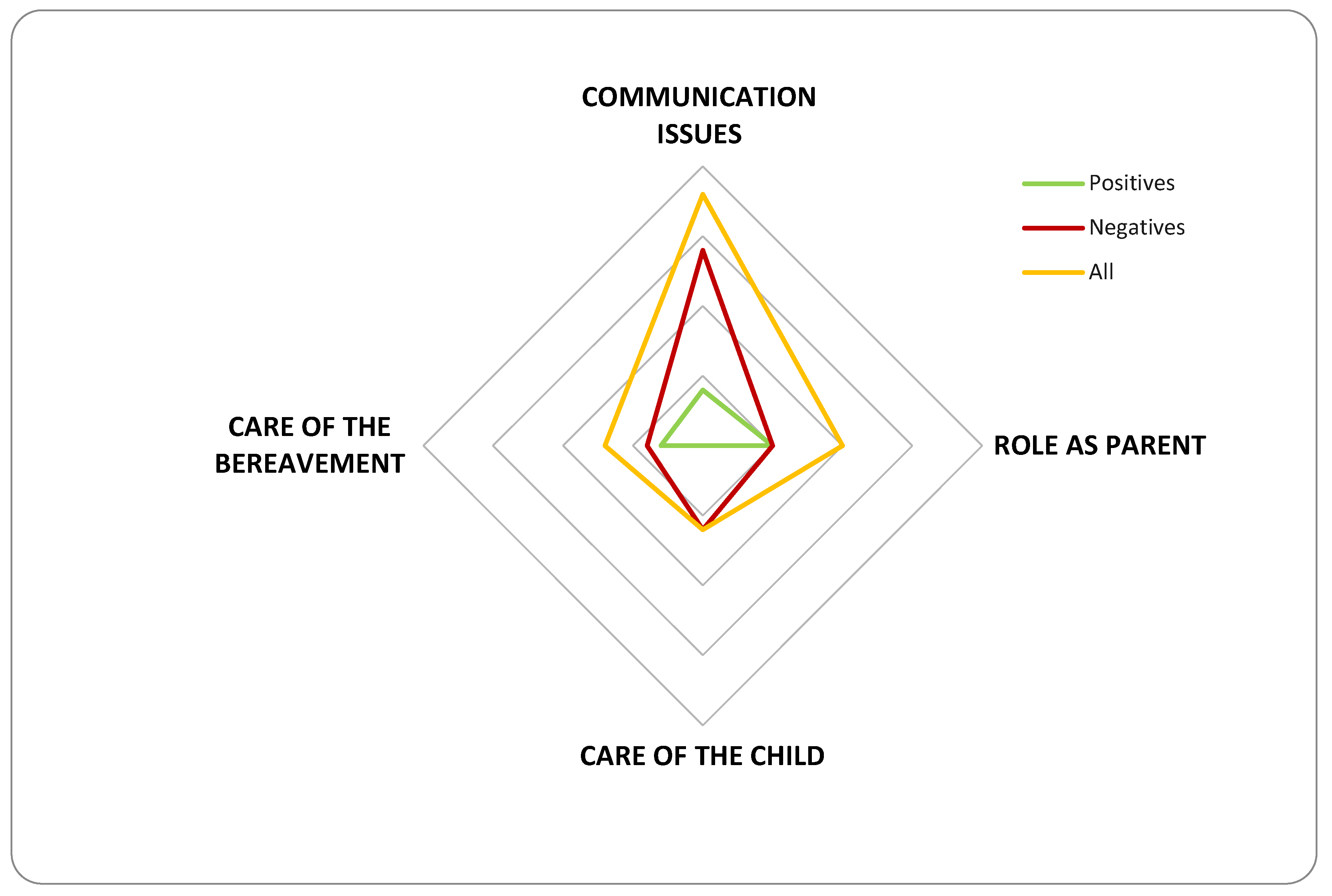

Rigor was maintained through peer debriefing, triangulation, and referential adequacy. While ethical considerations precluded contacting parents for further validation, comprehensive reviews confirmed the findings’ robustness. The final dataset was distilled into conceptual domains and themes, encapsulating the essence of the parental experience. Spontaneous comments collected during the study were analyzed and categorized into recurring themes. Each comment was further classified as positive or negative. Key categories included Communication Issues, Parental Role, Child Care, and Bereavement Support. The findings were visually summarized in a graph. A radar (spider) chart was chosen to visually represent the study’s findings, as it effectively displays the themes and their classification as either positive or negative [

17]. The chart comprises three data series: (1) positive comments, reflecting satisfaction or constructive experiences; (2) negative comments, highlighting areas of concern or dissatisfaction; and (3) total comments, representing the overall count within each thematic domain. This visual format facilitates a clear comparison across domains, emphasizing the balance—or imbalance—between positive and negative feedback within each theme.

2.5. Quantitative Analysis

Demographic and clinical data were encoded and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0. Continuous variables, such as age and duration of hospital stay, were summarized using mean, median, and range. Categorical variables, including demographic characteristics and clinical outcomes, were reported as frequencies in both absolute numbers and percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Participants and Recruitment

During the study period, 30 children died. Among the families, 28 (93%) met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 10 families (36%) could not be contacted, while 18 families (60%) participated in the study. The median time between the child’s death and the interview was 5 years, with a range of 3.5 to 6.5 years.

3.2. Patient Characteristics

Eighteen children were included in the study, of whom 56% (10/18) were male.

Table 2 depicts their baseline characteristics. The median age at death was 45 days (range: 15 days to 9 months), with all children being under 1 year of age at the time of death. The median length of the final hospital stay was 27 days (range: 10 to 130 days). Half of the children (9/18, 50%) had single-ventricle physiology anatomy.

Most patients (95%, 17/18) died in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit (CICU), while one child died in the pediatric cardiology ward. During the final 72 hours of life, nearly all patients (95%, 17/18) were intubated and sedated, and 77% (14/18) were receiving mechanical circulatory support, such as extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Multi-organ failure (MOF) was the leading cause of death, accounting for 72% of cases (13/18).

Modes of death included failed cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in 11% of cases (2/18) and withholding of treatment in 88% (16/18). Among the latter, three children had documented do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders and for them the pediatric palliative care consultation was requested.

3.3. Parent Characteristics

The majority of parents in the study group were women (14/18, 78%), with a median age of 41 years (range: 33 to 52 years). Regarding proximity to the hospital, 56% (10/18) of families lived 30 to 100 km away, 33% (6/18) lived more than 100 km away, and 11% (2/18) lived less than 30 km from the hospital.

In terms of religious background, 72% of parents (13/18) identified as Catholic, 17% (3/18) as Islamic, and 11% (2/18) did not report their religious affiliation. At the time of their child’s death, 11% of parents (2/18) were present.

3.4. Open-Ended Questions

When parents were asked, “What was most difficult for the child?” two themes emerged most frequently: the lack of affection due to limited parental contact during hospitalization and the burden of invasive treatments, both identified by 44% of participants (8/18). A smaller proportion of parents (11%, 2/18) mentioned the child’s inability to play as another significant difficulty.

Regarding their own challenges, parents’ responses reflected a range of struggles. Common themes included feeling isolated from extended family, difficulties managing family responsibilities, and the challenges of being far from home, each reported by 17% of participants (3/18). For some parents, the most difficult aspects were their inability to spend time with the child (11%, 2/18), being separated from their other children (11%, 2/18), or lacking time for self-care (11%, 2/18). A few parents also noted the distressing ICU environment (6%, 1/18), feelings of guilt (6%, 1/18), or a profound sense of helplessness in their inability to support their child effectively (6%, 1/18).

When asked, “Is there anything that made things easier?” many parents highlighted the importance of family support (44%, 8/18) and their religious faith (33%, 6/18) as sources of strength. Additionally, a smaller number of participants found solace in their love for the child (11%, 2/18) and maintaining hope (11%, 2/18) during these difficult times.

Parents were also invited to share advice for other families facing similar situations. More than half (56%, 10/18) expressed that there is no universal advice for such circumstances, underscoring the unique and deeply personal nature of each family’s experience. Others suggested seeking clarification from medical staff (11%, 2/18), relying on prayer (17%, 3/18), or consulting a therapist for emotional support (6%, 1/18). A few parents emphasized the importance of avoiding false optimism (6%, 1/18) and focusing on what is best for the child, even if that means accepting the inevitability of death (6%, 1/18).

Finally, parents offered advice to physicians based on their experiences. Many urged healthcare professionals to improve their human connection with families (44%, 8/18) and to provide clear, honest communication when discussing diagnoses (33%, 6/18). Some parents also emphasized the need for more opportunities to dialogue with medical staff (17%, 3/18) and encouraged physicians to give their utmost effort and dedication in supporting families during such difficult times (6%, 1/18).

3.5. Spontaneous Comments

Parents’ spontaneous comments revealed a spectrum of positive and negative experiences across four key domains: communication issues, the role as parents, care of the child, and care of bereavement. Positive reflections often emphasized compassionate interactions with healthcare professionals, moments of emotional connection, and support from family or spiritual advisors. However, many parents also highlighted significant challenges, including fragmented communication, feelings of helplessness, and inadequate preparation for their child’s EoL care. The negative comments were particularly concentrated in areas of communication and care management, underscoring gaps in transparency and emotional support.

Table 3 provides an overview of these comments classified as either positive or negative and categorized in themes.

Figure 1. illustrates the distribution of categorized comments, with negative feedback shown in red, positive feedback in green, and the overall totals in yellow. This visual representation highlights the proportions within each theme, enabling a clear comparison of positive and negative perceptions across various aspects of care and support.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to deepen our understanding of the feelings and needs of bereaved parents whose children died of CCHD in intensive care. While survival rates for congenital heart diseases have improved in recent years, critical or complex forms, such as single ventricle lesions, remain a leading cause of infant mortality. These conditions are often diagnosed prenatally and necessitate intensive, aggressive interventions within the first months of life [

4,

9].

Despite advancements in medical care, children with CCHD frequently die in intensive care units, often with limited focus on end-of-life (EoL) care [

5]. Research indicates a notable reluctance among cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and intensive care physicians to recognize or acknowledge when a child is nearing or has reached EoL [

7]. This hesitation can lead to the continuation of intensive, invasive treatments that may ultimately prove futile, prolonging the child’s suffering and reducing the quality of their remaining life. Addressing this gap is essential for fostering a more compassionate, patient-centered approach that prioritizes comfort and dignity in critical moments [

1,

9].

Qualitative studies, such as this, provide a crucial lens into the nuanced emotional and psychological dimensions of pediatric end-of-life care, offering insights that quantitative data alone cannot capture. By exploring the lived experiences of parents, qualitative studies help identify gaps in communication, barriers to care, and opportunities for improving family-centered interventions. This is particularly significant in pediatric palliative care, where subjective experiences and emotional needs play a central role in shaping care delivery. However, the retrospective nature of this study may have influenced the detail or emotional framing of their responses. Additionally, as this research was conducted in a single-center setting and included only Italian-speaking participants, its findings may not fully capture the experiences of diverse populations, cultures, or healthcare systems. Future studies should be designed to explore these varied perspectives further.

The data presented originate from a time period over a decade ago and are part of a broader quantitative research. While articles on this topic have become increasingly prevalent in the past decade, we believe that our analysis holds particular significance as it takes a qualitative approach, delving deeper into the subject matter.

Insights from Open-Ended Questions

The responses to the open-ended questions yielded nuanced insights into the personal and emotional dimensions of the parental experience, beyond the spontaneous reflections. When asked about the most difficult aspects for their child, parents overwhelmingly cited the burden of invasive treatments and the lack of physical affection, underscoring the emotional toll of prolonged hospital stays. This lack of closeness, reported by 44% of participants, highlights the critical need to reassess visitation policies and promote physical interaction between parents and children, even in intensive care environments.

Similarly, the parental responses regarding their own difficulties emphasized isolation, family separation, and the emotional exhaustion inherent in balancing caregiving with external responsibilities. For 17% of parents, the inability to be physically present for their child at all times or to manage other family obligations amplified their distress. Family-centered interventions address not only the child’s needs but also the broader context of parental well-being.

The open-ended responses further provided insight into resilience factors, with family support (44%) and religious faith (33%) emerging as key coping mechanisms. However, the notable absence of universal advice, as expressed by over half of the participants, suggests that while external support is valuable, the grief experience remains profoundly individualized. This draws attention to the necessity for personalized bereavement care pathways that accommodate diverse coping styles and acknowledge the uniqueness of each family’s journey.

Crucially, the reflections offered by parents on advice for clinicians pointed to actionable areas for improvement. Many urged healthcare providers to foster clearer, more compassionate communication, reflecting themes consistent with those found in the spontaneous comments. The emphasis on the human connection between physicians and families underscores the need for communication training that prioritizes empathy, transparency, and emotional support during difficult conversations.

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the emotional and logistical challenges faced by bereaved parents whose children died of CCHD in a PICU setting. Key findings highlight persistent gaps in communication, parental involvement, and bereavement support, alongside the critical role of family and faith as coping mechanisms. These findings underscore the importance of integrating early, structured pediatric palliative care interventions to address the unique needs of families during end-of-life care. Improved communication strategies, flexible visitation policies, and enhanced post-mortem follow-up are essential for fostering compassionate, family-centered care. Addressing these areas can improve the quality-of-care delivery and alleviate the emotional burden on families, offering a roadmap for better support during the most vulnerable moments of their journey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.B. and C.A.; Methodology, F.B., V.V. and L.G.; Investigation, All; Data Curation, All; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, F.B. and L.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, All; Supervision, L.G. and C.A.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Hospital Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedale Università di Padova approved the study design; the need for parental consent was waived for the revision of the clinical charts.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the Corresponding Author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- Benini, F.; Papadatou, D.; Bernadá, M.; Craig, F.; De Zen, L.; Downing, J.; et al. International standards for pediatric palliative care: From IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022, 63, e529-e543.

- Delgado-Corcoran, C.; Wawrzynski, S.E.; Mansfield, K.; Fuchs, E.; Yeates, C.; Flaherty, B.F.; et al. Grieving children’s death in an intensive care unit: Implementation of a standardized process. J Palliat Med. 2024, 27, 236-240. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.T.; Dahl, N. Paediatrics and discomfort with death and dying. Paediatr Child Health. 2023, 29, 303-305. [CrossRef]

- Blume, E.D.; Kirsch, R.; Cousino, M.K.; Walter, J.K.; Steiner, J.M.; Miller, T.A.; et al. Palliative care across the life span for children with heart disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2023, 16, e000114. [CrossRef]

- Adistie, F.; Neilson, S.; Shaw, K.L.; Bay, B.; Efstathiou, N. The elements of end-of-life care provision in paediatric intensive care units: A systematic integrative review. BMC Palliat Care. 2024, 23, 184. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.; Nunn, M. Palliative communication in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2023, 35, 287-294. [CrossRef]

- Porteri, C.; Ienco, G.; Turla, E.M.; Petrini, C.; Pasqualetti, P. Italian law n. 219/2017 on consent and advance directives: Survey among ethics committees on their involvement and possible role. BMC Med Ethics. 2022, 23, 114.

- Bertaud, S.; Lloyd, D.F.; Laddie, J.; Razavi, R. The importance of early involvement of paediatric palliative care for patients with severe congenital heart disease. Arch Dis Child. 2016, 101, 984-987. [CrossRef]

- Agosto, C.; Benedetti, F.; De Tommasi, V.; Milanesi, O.; Stellin, G.; Padalino, M.A.; et al. End-of-life care for children with complex congenital heart disease: Parents’ and medical caregivers’ perceptions. J Paediatr Child Health. 2021, 57, 696-701.

- Baughcum, A.E.; Fortney, C.A.; Winning, A.M.; Dunnells, Z.D.O.; Humphrey, L.M.; Gerhardt, C.A. Healthcare satisfaction and unmet needs among bereaved parents in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020, 20, 118-126. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, F.; Widger, K.; Sung, L.; Wheaton, L. End-of-life childhood cancer research: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2021, 147, e2020003780. [CrossRef]

- Woolf-King, S.E.; Arnold, E.; Weiss, S.; Teitel, D. “There’s no acknowledgement of what this does to people”: A qualitative exploration of mental health among parents of children with critical congenital heart defects. J Clin Nurs. 2018, 27, 2785-2794.

- Krick, J.A.; Weiss, E.M.; Snyder, A.; Haldar, S.; Campelia, G.D.; Opel, D.J. Living with the unknown: A qualitative study of parental experience of prognostic uncertainty in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol. 2021, 38, 821-827. [CrossRef]

- Alzawad, Z.; Lewis, F.M.; Kantrowitz-Gordon, I.; Howells, A.J. A qualitative study of parents’ experiences in the pediatric intensive care unit: Riding a roller coaster. J Pediatr Nurs. 2020, 51, 8-14. [CrossRef]

- Colaizzi, P.F. Psychological research as a phenomenologist views it. In: King, R.V.M., Ed.; Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978; pp. 48–71.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101.

- Verdinelli, S.; Scagnoli, N.I. Data Display in Qualitative Research. Int J Qual Methods. 2013, 12, 359–381. [CrossRef]

- Songer, K.L.; Wawrzynski, S.E.; Olson, L.M.; Harousseau, M.E.; Meeks, H.D.; Moresco, B.L.; Delgado-Corcoran, C. Timing of Palliative Care Consultation and End-of-Life Care Intensity in Pediatric Patients With Advanced Heart Disease: Single-Center, Retrospective Cohort Study, 2014-2022. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2025, 26, e23-e32. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).