1. Introduction

For many years, Fe–Mn–Al ternary alloys have been studied as possible alternatives to Fe–Ni–Cr stainless steel. The combination of outstanding physical and mechanical properties while offering a weight reduction of up to 18% make low density Fe–Mn–Al steels attractive structural materials as lightweight crash-resistant car body structures and structural components in the cryogenic industry [

1]. Alloying of steel with Mn and Al leads to achieving lightweight in steels in which decreased specific gravity due to their substitutional atom nature works to reduce the weight [

2]. Weight reduction for example for steels used in automotive industry has given a boost to the effort to lower fuel consumption thus improve its driving performance while lowering its emissions at the same time [

3].

Knowledge on phase equilibria especially at high temperature plays a crucial role in development of Fe-Mn-Al alloys with corrosion resistance and high-temperature oxidation resistance as well good strength at elevated temperature. The phase equilibria in Fe-Mn-Al system have been investigated by various researchers [

4,

5,

6,

7]. According to the reported phase equilibria diagrams, increasing Mn and AI content stabilizes the austenitic and ferrite phases, respectively. Specifically, a higher concentration of Mn in the alloy results in a greater proportion of austenite, as opposed to predominantly ferrite in low-temperature Fe alloys. On the other hand, Al, known as a ferrite stabilizer, helps form a dual-phase structure of ferrite and austenite at high temperatures, and promotes the formation of precipitates (ppts) during cooling [

8]. Additionally, in Fe-Mn-Al alloys with low aluminum content and high manganese content, a fully austenitic microstructure can be maintained even at low temperatures. Under these conditions, the transformation from high-temperature BCC (body-centered cubic) phase to FCC (face-centered cubic) phase occurs at a lower temperature, unlike conventional ferrous alloys where this transformation is obscured by the formation of another BCC phase. By appropriately alloying ferrous alloys, it becomes possible for the transformation from BCC phase to austenite to take place at low temperatures. This is important in understanding the austenite formation and its further transformation as observed in Fe-Mn-Al alloys.

Unlike in steels, cooling Fe-Mn-Al alloys from high-temperature leads to transformations that involve a change from ferrite to austenite phases [

9]. Depending on the heat treatment conditions, cooling these steels from high temperatures, have been found to undergo phase transformation to yield phases such as Widmanstätten austenite [

10,

11,

12], massive austenite [

13], and martensitic phases [

14,

15,

16,

17]. When the cooling rates are high, this transformation results in the formation of massive austenite [

13], as well as needle-like 18R martensite within the ferrite grains [

14,

18]. Conversely, low cooling rates leads to formation of the austenite side-plates known as Widmanstätten structures [

10,

11] as well as austenite ppts within ferrite grains [

9]. In general, various cooling processes for these steel alloys from high temperatures can result in different phase transformations, such as Widmanstätten side-plate formation massive transformation, martensitic transformation, and spinodal decomposition.

The microstructures of Fe-Mn-Al steels play a crucial role in determining their material properties, motivating extensive research into their microstructure, phase transformation behavior, and mechanical properties under various thermal treatments and cooling rates. For instance, formation of needle like ppts, has been reported in these alloy systems after annealing at high temperature, and subsequent cooling via methods such as quenching in water [

13,

14], furnace cooling [

10,

11] or cooling air [

10]. Liao et-al examined L1

2 ppts within ordered L2

1 phase in an Fe-Mn-Al alloy after annealing at 1300°C for 2 h followed by furnace cooling to room temperature. Similarly, Cheng reported formation of a new phase of Widmanstätten morphology in an Fe-Mn-Al alloy steel upon air cooling an Fe-Mn-Al steel from high temperature. However, these studies did not provide detailed insights into the microstructural characteristics nor the mechanisms underlying the evolution of the reported needle-like precipitate phase in the BCC matrix. This study focused in analyzing the phase composition of the Widmanstätten side-plate ppt phase and to elucidate the mechanisms responsible for its formation in the Fe-Mn-Al alloy. Spinodal decomposition and ordering reactions were identified as key processes governing the observed phase transformations in the alloy system under investigation.

Spinodal decomposition is phase separation process that occurs in certain alloy systems when they are cooled from a high-temperature homogeneous solid solution state to a lower temperature. This process is driven by the tendency of the alloy to lower its Gibbs free energy by separating into two or more distinct phases [

19,

20]. The phase diagram for an alloy system that exhibits spinodal decomposition exhibits a miscibility gap region. When a homogeneous solid solution is cooled into this unstable region, phase separation occurs spontaneously. This indicates that there is no chemical energy barrier preventing the reaction from taking place. Key requirement of spinodal decomposition is that the parent and product phases must have the same crystal structure in order to allow a smooth connection of the Gibbs free energy curve between both composition ends of the product phases. The main distinction between the product phases lies in their compositions [

19,

20,

21,

22]

The studies of the spinodal decomposition have been reported in various alloys reported in various alloys [

21,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Spinodal decomposition in the Fe-C-Mn-Al steels after cooling from high temperature for instance, lead to the transformation of high-temperature FCC austenite into low-temperature FCC austenite and L1

2 phases [

21]. The crystal structure of the FCC austenite is with the Fm m space group. On the other hand, the L1

2 phase, with a Cu3Au structure is a derivative crystallographic structure from the FCC austenite, and its crystal structure belongs to the Pm m space group. Therefore, we have to note that the crystal structure of the L1

2 phase is simple cubic (SC) which is not the same as the FCC austenite. However, one necessary condition for the occurrence of the spinodal decomposition is that the product phases must have the same crystal structure as that of their parent phase. Thus, the SC L1

2 phase is not the direct product phase from the spinodal decomposition, but is produced from an additional phase transformation called ordering reaction which occurs after the spinodal decomposition [

21].

The ordering reaction is also a special case of the ordering effect of the solid solution which has a large negative value of the enthalpy of mixing. Unlike atoms in the solid solution attract each other and form an ordered phase. The low-temperature product ordered phase has the derivative crystal structure from the high-temperature parent phase. One of the features of the ordering reaction is that both parent and product ordered phases are with similar crystal structures and the interfacial energies between them are very low. So almost no activation energy barrier hinders the occurrence of the ordering reaction [

20]. Cheng et-al in their study reported that upon cooling the Fe-C-Mn-Al steel, the spinodal decomposition and ordering reaction occur consecutively. They posited that high-temperature FCC austenite (γ) decomposes initially into two low-temperature FCC austenite phases via the spinodal decomposition. One is carbon-lean FCC austenite′ (γ′) and the other is carbon-enriched FCC austenite′′ (γ′′). The carbon-enriched austenite′′ then transforms to the SC L1

2 superlattice phase through the ordering reaction afterwards. The final product phases are composed of disordered FCC austenite γ′ and ordered SC L1

2, and the overall reactions are in the following. γ → γ′ + γ′′ → γ′ + L1

2 [

21]. In general, austenite plays an important role in Fe–Mn–Al steels because of its possible evolutions. Each configuration derived from γ reaction has its own specific properties and/or drawbacks, which need to be mastered in order to determine optimum steel processing parameters which lead to developing valuable products. The main objective of this paper is to investigate existence and formation of a dual phase structure comprising FCC and L1

2 phases derived from Widmanstätten side plates in a Mn-Al alloyed steel annealed at 1100℃ for 1 h and subsequently air-cooled.

2. Materials and Methods

The alloy material used in this study was prepared by vacuum induction melting process, and its nominal composition was Fe-8.3 Mn-16.9 Al-0.8 C(at.%) Commercial 1008 steel, electrolytic manganese, and high purity aluminum were melted together and casted into approximately 10 kg ingots. All references to composition hereafter are expressed in at.%. The ingots were then sectioned, homogenized at 1200°C for 4 h under an argon protected atmosphere, hot-forged into slabs. The slabs were further sectioned using a water-cooled cutting machine to produce test samples with dimensions 15 mm 10 mm 2 mm. These samples were mechanically ground to remove the oxide layer, sealed in quarts tubes under vacuum, subsequently heated to 1100°C in a box furnace for 1 h, and cooled in air to room temperature.

The as-air-cooled test samples were prepared by mechanically grinding and polishing for various material analysis processes. The samples for observation in an optical microscope and scanning electron microscope (SEM) were finally etched in a 5% nital solution. The overall microstructure was characterized using optical microscope while the phase morphology and chemical compositional analyses was performed using JEOL JXA-7900SX high resolution field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDXS). Some samples were also examined to identify the alloy’s crystal structure by x-ray diffraction (XRD) in a Rigaku DMAX-B x-ray diffractometer operated at a power of 12 kW and 30 V. The microstructure and crystal structure of the phases present in the alloy were further characterized using a Talos F200X G2 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operated with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The TEM specimens were prepared by further mechanically grinding into thin foils approximately 80 μm thick, punching them into 3 mm diameter discs, and finally polishing them using a twin jet electro-polisher in a 5% HClO4 in a 95% CH3COOH solution at 20 V/0.1 A/cm2 at -15°C.

3. Results

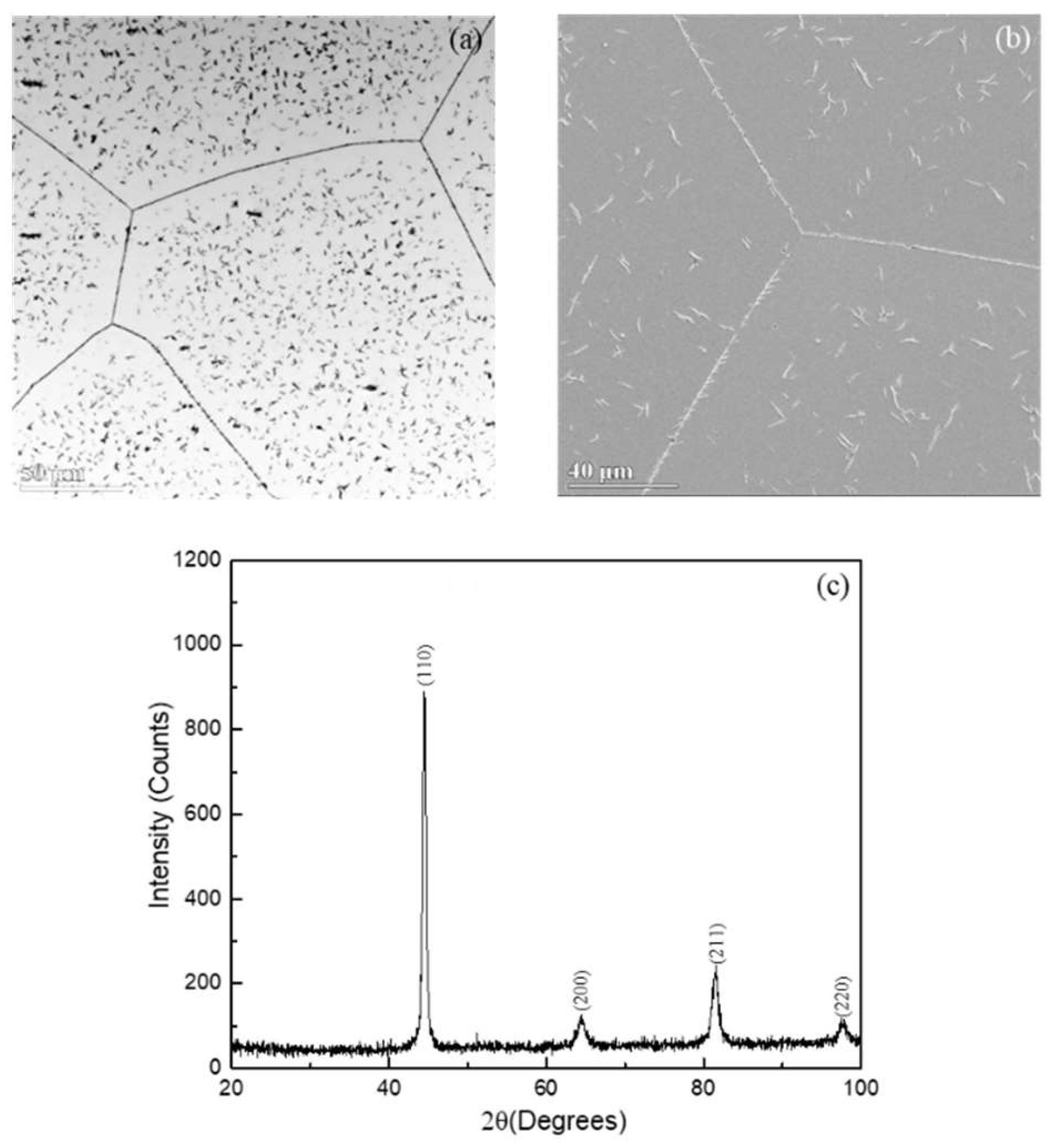

Figure 1 shows the microstructural characterizations of the Fe-Mn-Al alloy after annealing at 1100°C for 1 h and cooling in air (AC). The alloy after this heat treatment is referred as the 1100°C-AC alloy. An optical micrograph (OM) in

Figure 1(a) and SEM secondary electron image (SEI) in

Figure 1(b) reveal that the 1100°C-AC alloy exhibits a dual-phase structure. The primary phase forms a continuous matrix, accompanied by a second phase in the form of needle-like ppt. Closer examination of the SEI in

Figure 1(b) reveals that the needle like ppts exhibit morphological features that are characteristic of Widmanstätten side plates. This structure was commonly observed in alloys after annealing at high temperatures and cooling at high cooling rates [

28]. Similar morphologies have been reported by Cheng and Liao et al in the studies in Fe-Mn-Al alloys. An XRD pattern shown in

Figure 1(c) manifests BCC diffraction peaks only. It represents most probably the matrix phase as a BCC phase. However, the ppt phase may have not identified by the XRD, likely due to its relatively low volume fraction compared with the matrix phase. Therefore, based on these analyses, the 1100°C-AC alloy consists of two phases: the BCC matrix phase and the Widmanstätten side-plate phase.

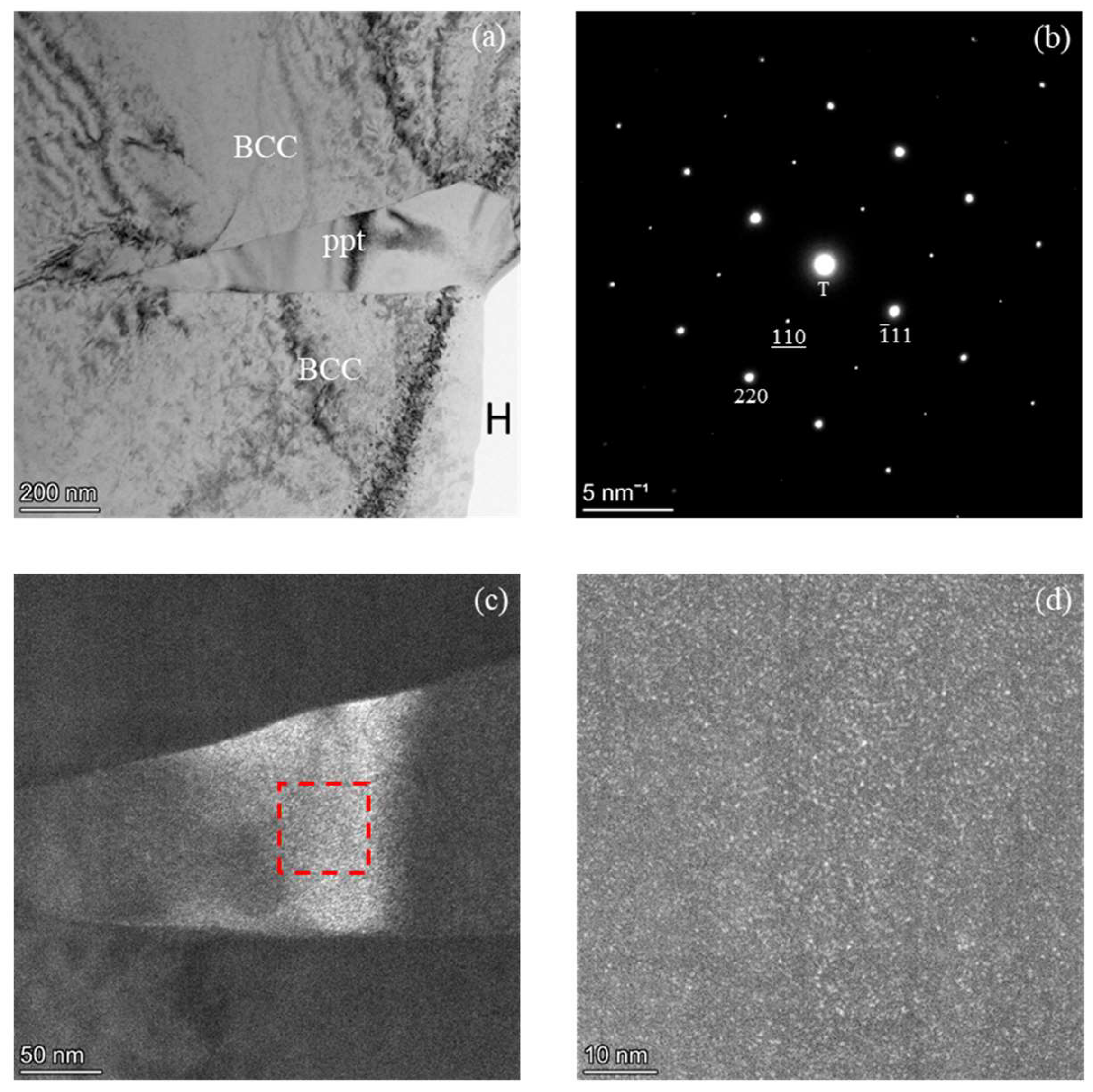

We performed TEM analyses to further clarify the alloy’s phase constitution and to study the ppt in detail. A bright field (BF) image shown in Fig 2(a) confirmed that the 1100℃-AC alloy has a dual phase microstructure. Although the results are not shown here, the electron diffraction analysis on the matrix phase revealed that the matrix consisted primarily of the BCC ferrite phase. The selected area diffraction pattern (SADP) acquired from the ppt phase as depicted in

Figure 2(b) was taken along FCC [1

2] and it indicates that the ppt is mixed with a combination structure of both FCC and L1

2. The L1

2 is an ordered phase having a super lattice structure. Specific Miller indices corresponding to the L1

2 reflections in

Figure 2(b) are underlined to differentiate them from those of the fundamental FCC reflections. Therefore, it was conclusively determined that the 1100°C-AC alloy consists of the BCC matrix and the Widmanstätten side-plate ppts. The side-plate ppts comprise FCC and L1

2 phases.

Further TEM analyses were conducted to examine the finer details of the Widmanstätten side-plate ppt using dark-field (DF) imaging. The DF images taken from the (110) superlattice diffraction spot, are shown in

Figure 2c,d. These images reveal the presence of fine L1

2 particles uniformly distributed within the FCC matrix. The L1

2 particle shape was approximated to be spherical, with a diameter of about 1 nm, indicating a nanoscale dispersion. This morphology underscores the coherent co-existence of the ppts with their host matrix [

20]. This observation suggests that the L1

2 phase likely precipitated homogeneously within the FCC matrix as fine, coherent particles during the cooling process. Thus, Widmanstätten side-plate ppts of the alloy were confirmed to consist of dual phases of the FCC phase and the L1

2 ordered phase, highlighting the complex phase interactions within the alloy. To establish the elemental compositions of existent phases in the alloy, further TEM-STEM analysis was performed.

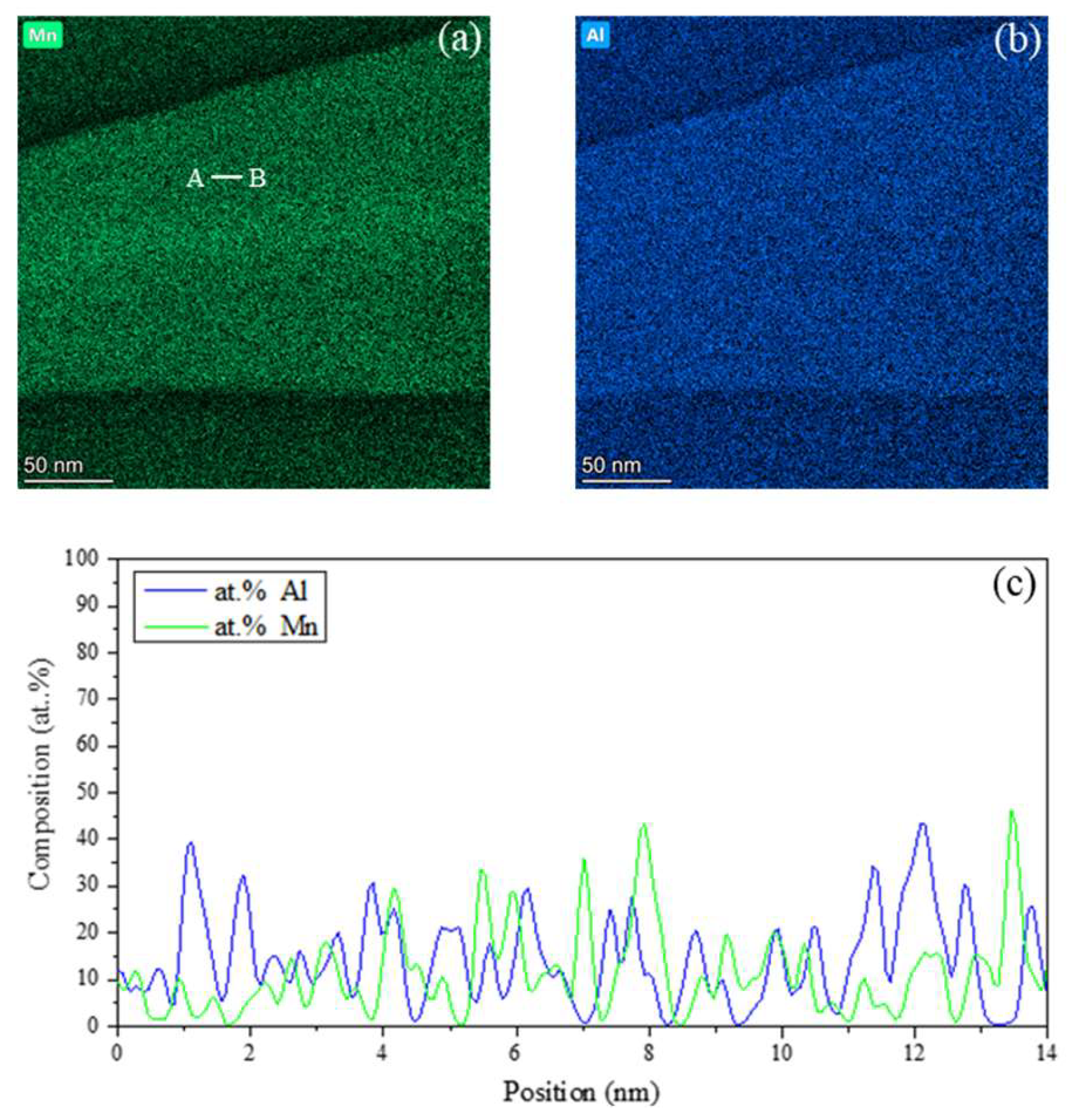

Figure 3 shows the elemental distribution mappings and line scans for the region including majorly the Widmanstätten side-plate.

Figure 3a,b illustrate the distribution of Mn and Al on the Widmanstätten side-plate and the surrounding matrix. The distribution mapping of solvent Fe is not shown since the summation of the alloy composition is 100% and its distribution trend was found to be opposite to that of the solute elements. In these mappings, brighter the color intensity in a specific region indicates higher the concentration of the selected element. The results indicate that the ppt phase is enriched in Mn and Al as compared with those of the surrounding matrix. These mappings further reveal nano-scale elemental segregation within the ppt region, as evidenced by the presence of brighter and darker nanosized regions in both

Figure 3a,b. The brighter color intensity regions correspond to approximately spherical particles embedded in the matrix with a dark contrast. These particles exhibit similar distribution and morphology as those observed in the DF image shown in

Figure 2c,d. Consequently, these particles are supposed to be L1

2 particles while the darker region would represent the FCC matrix.

Compositional analysis was also done by EDS to quantitatively establish how elements were partitioned among the alloy’s constituent phases. The EDS analysis revealed the average elemental composition for the matrix and the ppt approximately as Fe-9.0 Mn-17.0 Al and Fe- 9.5 Mn-26.9 Al, respectively. The margin of error for these measurements is approximately 10%. However, the carbon content could not be established using this method because of carbon contamination issues inherent to the equipment. These results together with those shown in

Figure 3a,b confirm that the ppt is enriched in Mn and Al and lean in Fe. The composition of the nanosized L1

2 particles could not be distinguished from that of FCC phase due to their particle size. Alternatively, STEM line scans along the line AB in

Figure 3(a) were used to indicate the concentration distributions of the Mn and Al among the constituent phases of the ppt. The elemental concentration profiles, shown in

Figure 3(c) for Mn and Al reveal nanoscale variations around the average ppt composition These elemental distribution variations are attributed to the presence of two distinct phases within the ppt. These results combined with those in

Figure 2b–d confirm that the ppt comprises a dual-phase structure consisting of L1

2 and FCC phases.

4. Discussion

The above experimental observations provide essential insights into the dual-phase characteristics of the Widmanstätten side-plate ppt, and their corresponding phase transformations, which are discussed below. The BCC matrix phase is proposed to exist as single high-temperature alloy’s phase while the Widmanstätten side-plate phase forms at lower temperatures during cooling through a precipitation transformation [

9,

20,

28]. The final microstructure reveals that the Widmanstätten side-plate ppt comprises a dual phase of FCC and L1

2. The L1

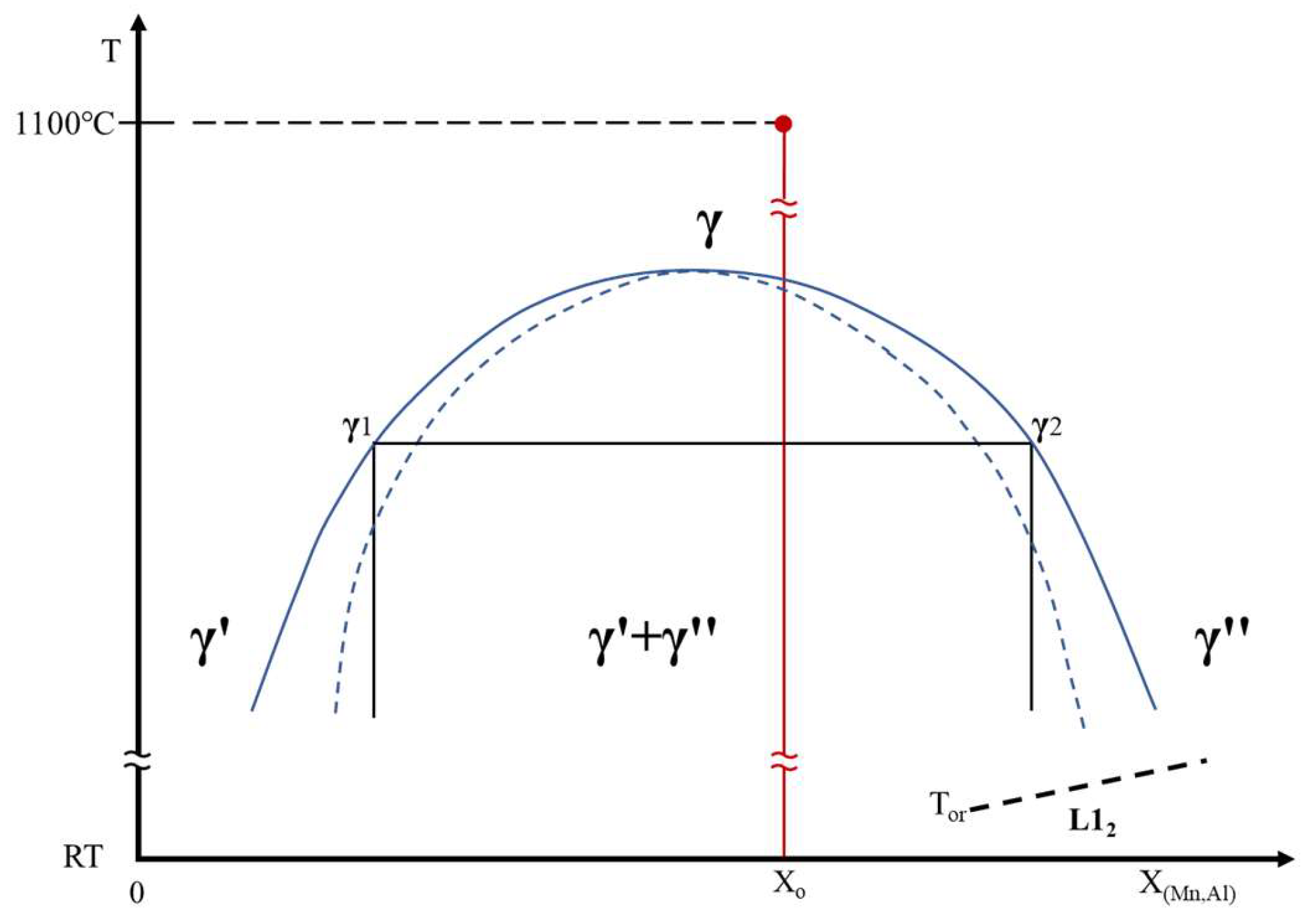

2 phase is observed as particles distributed homogeneously in the FCC matrix as shown in Figs 2(b). In this case, we propose that the Widmanstätten side-plate ppt should have an FCC phase only at the initial formation stage. However, upon further cooling, the high-temperature FCC phase decomposes into two low temperature product FCC phases through spinodal decomposition. One is an Al and Mn lean phase and the other is an Al and Mn enriched phase as shown in

Figure 3a,b. The Al and Mn enriched phase should have subsequently transformed into the L1

2 phase when the alloy was cooled further to low temperatures [

19,

21,

22].

As previously mentioned, spinodal decomposition is governed by the requirement that the parent and product phases should have the same crystal structure [

21]. Thus, during air cooling of the Fe-Mn-Al duplex ferritic alloy, the high temperature FCC phase will first decompose into two distinct low temperature FCC austenite phases, denoted as FCC

ꞌ and FCC

ꞌꞌ, rather than directly transforming into low temperature FCC austenite phase and the SC L1

2 phase. Among these two low temperature FCC austenite phases, FCC′ is solute-lean while the FCC″ is solute-rich. At temperatures below ordering reaction temperature T

or, the FCC″ phase undergoes an ordering reaction, transforming into the L1₂ phase. The L1

2 phase which is a SC crystal structure is a derivative phase of the FCC, but its crystal structure is distinct. Consequently, the L1

2 phase is not a direct product phase of spinodal decomposition. Instead, it’s formation occurs through a subsequent phase transformation process driven by an ordering reaction following spinodal decomposition [

21]. This phase transformation sequence highlights the interplay of the two mechanisms: spinodal decomposition, which serves as the initial process, and the subsequent ordering reaction, which results in the formation of the FCC and L1

2 phases in the Widmanstätten side-plate ppt.

Based on the above discussions, we propose that as the 1100℃-AC alloy cooled, it entered the spinodal region of the miscibility gap in the alloy’s phase diagram as illustrated in

Figure 4. The FCC austenite phase in the Widmanstätten side-plate (Wid. γ) which formed at a high temperature decomposed into two low-temperature austenite phases through the spinodal decomposition. One is lean in Al and Mn content (γ′) and the other is enriched in Al and Mn (γ″). This is evidenced in the elemental distribution mappings in

Figure 3a,b and line scans in

Figure 3(c). Upon cooling the alloy further to temperatures below the T

or, the low-temperature γ″ transformed into L1

2 phase through the ordering reaction. Therefore, the overall phase transformation sequence in the Widmanstätten side-plate ppt of the Fe-Mn-Al ferritic steel after air cooling are as follows: Wid. γ → Wid. (γ′+ γ″) → Wid. (γ′ + L1

2). This analysis clarifies the observed microstructural features on the 1100℃-AC alloy.