Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. COVID-19 mRNA-LNP Vaccines: Collateral Immune Effects Beyond Antiviral Defense

3. The Symptoms, Incidence and Prevalence of Adverse Events and Deaths: Limitations of Statistics

4. Unique Structural Features of Comirnaty and Spikevax

5. Preclinical Pharmacokinetic, Tissue Distribution and Toxicities

6. The Distinct Structural Characteristics of mRNA-LNPs That May Be Linked to Adverse Events and Complications

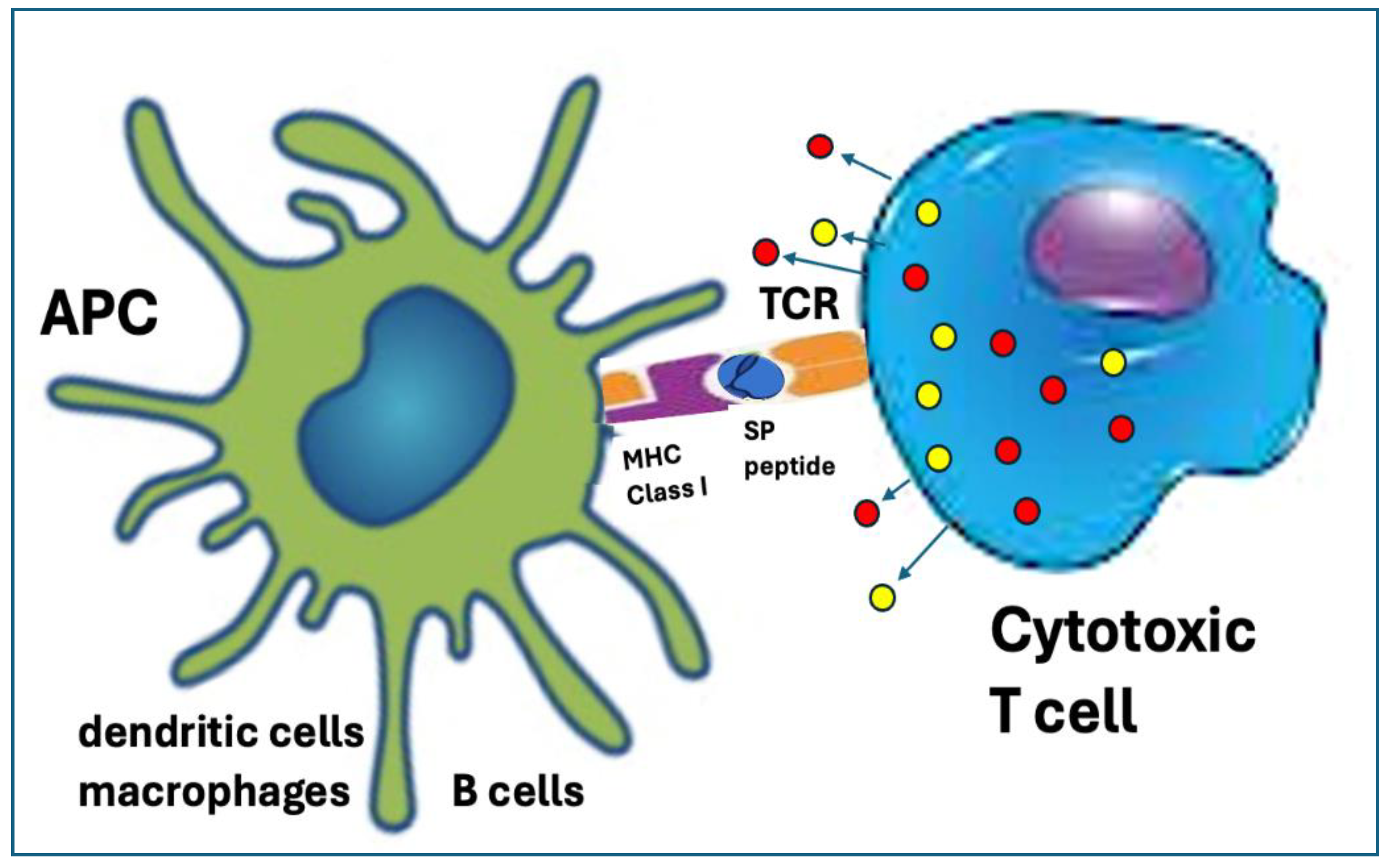

6.1. Ribosomal Synthesis of the Spike Protein Fundamentally Transforms Antigen Processing and Presentation

6.2. Multiple Chemical Modification of the mRNA Increases Its Stability and Translation Efficacy

6.2.1. Replacement of mRNA Uridine with Pseudouridine (ψ)

6.2.2. Codon Optimization

6.2.3. Methylation of the 5’ Cap

6.2.4. UTR Stabilization

6.2.5. 3′ Poly(A) Tail Optimization

6.2.6. GC Enrichment

6.3. The Biological Consequences of Ribosomal Antigen Synthesis and mRNA Modification

6.3.1. Enhancement of Immunogenicity

6.3.2. Uncontrollable Cytoplasmic Accumulation with Diversification of the Processing and Presentation of the SP

6.3.3. Digestion of the SP by the Proteasomes Resulting in Cross Presentation on MHC-Class-I Molecules with Autoimmune Damage

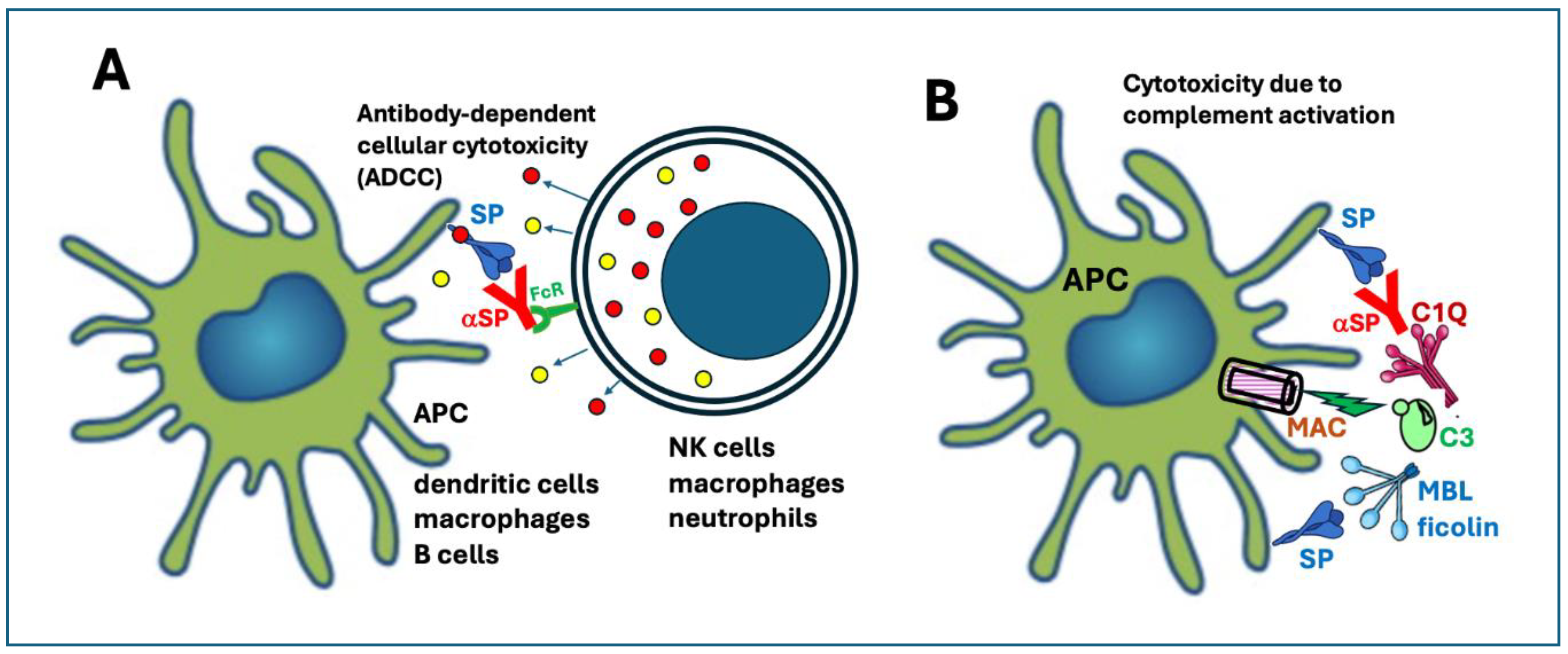

6.3.4. Expression of the SP on the Plasma Membrane Leading to Antibody-Mediated Cellular and Complement-Mediated Humoral Cytotoxicities

6.3.5. The "Seneca Effect"

6.3.6. Secretion of SP into the Extracellular Space for SP Reuptake and Systemic Dissemination

6.3.7. The Autophagy Pathway of Antigen Processing and Presentation

6.3.8. Exosomal Dissemination of Vaccine and Viral Elements Propagating Inflammation and Transfection: The Dumbed-Down Virus/LNP Chimera Concept

6.3.9. Excessive Somatic Hypermutation in B Cells

6.3.10. Reverse Transcription of the mRNA with Insertion Mutagenesis May Prolong the Risk of Harm

6.3.11. Frameshift Mutation upon mRNA Translation Causing SP Polymorphism

6.4. The Spike Protein Can Be Toxic

6.4.1. The Structure and Cellular Secretion of the Spike Protein

6.4.2. Clinical Manifestations of SP Toxicity

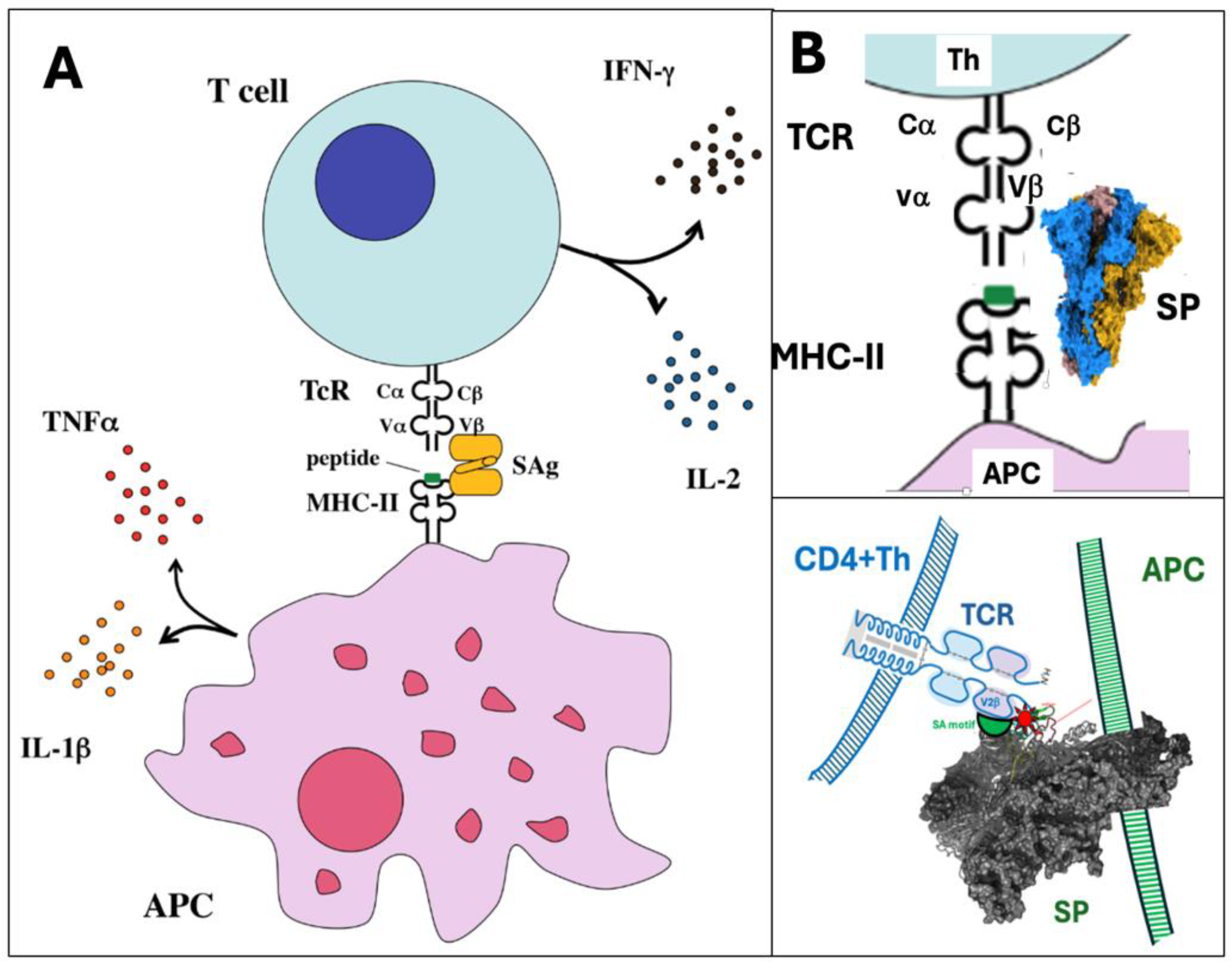

6.4.3. The Superantigen-Like Activity of the Spike Protein

6.4.4. The Spike Protein May Act Like a Toxoid with Sporadic Pathogenicity

6.5. The LNP Is Pharmacologically Active Immune Stimulant and mRNA Transfectant

6.5.1. Activation of the Cellular Arm of Innate Immunity

6.5.2. Triggering of Humoral Immune Response: Complement Activation

6.5.3. The LNP Is a Superadjuvant

6.5.4. The LNP Is a Fusogenic Transfecting Agent

6.6. The PEG on the LNP Surface Is Immune Reactive and Immunogenic

6.6.1. True and Pseudoallergic Reactogenicity

6.6.2. Anti-PEG Immunogenicity

6.7. The LNP Is Unstable in Water

6.8. The Spike Protein Is Enriched with Proline

6.9. The Injectable Vaccines May Contain Contaminations with Plasmid DNA and Inorganic Elements

7. The Issue of Turbo Cancer, Alias Conspiracy Cancer

8. Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krumholz, H.M.; Wu, Y.; Sawano, M.; Shah, R.; Zhou, T.; Arun, A.S.; et al. Post-Vaccination Syndrome: A Descriptive Analysis of Reported Symptoms and Patient Experiences After Covid-19 Immunization. MedRxiv posted November 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.; Bhakdi, S.; Hooker, B.; Holland, M.; DesBois, M.; Rasnick, D.; et al. mRNA Vaccine Toxicity. https://d4ce.org/mRNA-vaccine-toxicity/2023.

- Costa, C.; Moniati, F. The Epidemiology of COVID-19 Vaccine-Induced Myocarditis. Adv Med. 2024, 2024, 4470326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, N.; Tordesillas, L.; Cabanillas, B. Adverse rare events to vaccines for COVID-19: From hypersensitivity reactions to thrombosis and thrombocytopenia. Int Rev Immunol. 2022, 41, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oueijan, R.I.; Hill, O.R.; Ahiawodzi, P.D.; Fasinu, P.S.; Thompson, D.K. . Rare Heterogeneous Adverse Events Associated with mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review. Medicines (Basel). 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Flores, T.; Sampieri, A.; Vaca, L. Incidence and management of the main serious adverse events reported after COVID-19 vaccination. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024, 12, e1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law, B. Priority List of COVID-19 Adverse events of special interest: Quarterly update December 2020. Safety Platform for Emergency Vaccines (SPEAC). 2021;https://brightoncollaboration.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/SO2_D2.1.2_V1.2_COVID-19_AESI-update_V1.3-1.pdf.

- Fraiman, J.; Erviti, J.; Jones, M.; Greenland, S.; Whelan, P.; Kaplan, R.M.; et al. Serious adverse events of special interest following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination in randomized trials in adults. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 5798–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faksova, K.; Walsh, D.; Jiang, Y.; Griffin, J.; Phillips, A.; Gentile, A.; et al. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine. 2024, 42, 2200–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, K.M.; Buttery, J.P.; Crawford, N.W.; Cheng, D.R. Letter to the Editor: A comparison of post-COVID vaccine myocarditis classification using the Brighton Collaboration criteria versus (United States) Centers for Disease Control criteria: an update. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 2024, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitan, B.; Hadler, S.C.; Hurst, W.; Izurieta, H.S.; Smith, E.R.; Baker, N.L.; et al. The Brighton collaboration standardized module for vaccine benefit-risk assessment. Vaccine. 2024, 42, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y.M.; Ferrari, M.; Lynch, N.J.; Yaseen, S.; Dudler, T.; Gragerov, S.; et al. Lectin Pathway Mediates Complement Activation by SARS-CoV-2 Proteins. Front Immunol. 2021, 12, 714511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeOre, B.J.; Tran, K.A.; Andrews, A.M.; Ramirez, S.H.; Galie, P.A. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Disrupts Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity via RhoA Activation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2021, 16, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indes, J.E.; Koleilat, I.; Hatch, A.N.; Choinski, K.; Jones, D.B.; Aldailami, H.; et al. Early experience with arterial thromboembolic complications in patients with COVID-19. J Vasc Surg. 2021, 73, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles, J.P.; Zamora, M.; Adan-Castro, E.; Siqueiros-Marquez, L.; Martinez de la Escalera, G.; Clapp, C. The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces endothelial inflammation through integrin alpha5beta1 and NF-kappaB signaling. J Biol Chem. 2022, 298, 101695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perico, L.; Morigi, M.; Galbusera, M.; Pezzotta, A.; Gastoldi, S.; Imberti, B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein 1 Activates Microvascular Endothelial Cells and Complement System Leading to Platelet Aggregation. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 827146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, C.B.; Zhang, L.; Bhushan, A.; Swanson, B.; Zhang, L.; Mamede, J.I.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 S1 Spike Protein Promotes MAPK and NF-kB Activation in Human Lung Cells and Inflammatory Cytokine Production in Human Lung and Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Microorganisms. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thachil, J.; Favaloro, E.J.; Lippi, G. D-dimers-"Normal" Levels versus Elevated Levels Due to a Range of Conditions, Including "D-dimeritis," Inflammation, Thromboembolism, Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation, and COVID-19. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2022, 48, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, E.; Grover, P.; Zhang, H. Thrombosis after SARS-CoV2 infection or COVID-19 vaccination: will a nonpathologic anti-PF4 antibody be a solution?-A narrative review. J BioX Res. 2022, 5, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimura, Y.; Holland, L.Z. COVID-19 microthrombosis: unusually large VWF multimers are a platform for activation of the alternative complement pathway under cytokine storm. Int J Hematol. 2022, 115, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.V.; Rethi, L.; Lee, T.W.; Higa, S.; Kao, Y.H.; Chen, Y.J. Spike Protein Impairs Mitochondrial Function in Human Cardiomyocytes: Mechanisms Underlying Cardiac Injury in COVID-19. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.; Aparicio-Alonso, M.; Henry, M.; Radman, M.; Attal, R.; Bakkar, A. Toxicity of the spike protein of COVID-19 is a redox shift phenomenon: A novel therapeutic approach. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023, 206, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettori, M.; Dima, F.; Henry, B.M.; Carpene, G.; Gelati, M.; Celegon, G.; et al. Effects of Different Types of Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein on Circulating Monocytes' Structure. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vettori, M.; Carpene, G.; Salvagno, G.L.; Gelati, M.; Dima, F.; Celegon, G.; et al. Effects of Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Variants on Platelet Morphology and Activation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Nishikawa, M.; Kanno, H.; Yang, R.; Ibayashi, Y.; Xiao, T.H.; et al. Long-term effects of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccinations on platelets. Cytometry A. 2023, 103, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Whitehouse, K.; Bruno, R. Potential health risks of mRNA-based vaccine therapy: A hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2023, 171, 111015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, P.I.; Lefringhausen, A.; Turni, C.; Neil, C.J.; Cosford, R.; Hudson, N.J.; et al. 'Spikeopathy': COVID-19 Spike Protein Is Pathogenic, from Both Virus and Vaccine mRNA. Biomedicines. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, C.; Liang, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhou, L.; Chen, N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces the cytokine release syndrome by stimulating T cells to produce more IL-2. Front Immunol. 2024, 15, 1444643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dima, F.; Salvagno, G.L.; Lippi, G. Effects of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants on red blood cells parameters and red blood cell distribution width. Biomed J. 2024, 2024, 100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouman, S.; El-Kholy, N.; Hussien, A.E.; El-Derby, A.M.; Magdy, S.; Abou-Shanab, A.M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-associated lymphopenia: possible mechanisms and the role of CD147. Cell Commun Signal. 2024, 22, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Jeong, M.; Park, J.; Jung, H.; Lee, H. Immunogenicity of lipid nanoparticles and its impact on the efficacy of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. Exp Mol Med. 2023, 55, 2085–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wu, Z.; Wass, L.; Larson, H.J.; Lin, L. Mapping global public perspectives on mRNA vaccines and therapeutics. NPJ Vaccines. 2024, 9, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S.; Kumari, M.; Chen, G.H.; Hong, M.H.; Yuan, J.P.; Tsai, J.L.; et al. mRNA-based vaccines and therapeutics: an in-depth survey of current and upcoming clinical applications. J Biomed Sci. 2023, 30, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diblasi, L.; Monteverde, M.; Nonis, D.; Sangorrín, M. At Least 55 Undeclared Chemical Elements Found in COVID-19 Vaccines from AstraZeneca, CanSino, Moderna, Pfizer, Sinopharm and Sputnik, V.; with Precise ICP-MS. International Journal of Vaccine Theory, Practice, and Research 2024, 3, 1367–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, J. Expanded spectrum and incidence of adverse events linked to COVID-19 genetic vaccines: New concepts on prophylactic immuno-gene therapy and iatrogenic orphan disease Preprints Org. 2024;Submittedhttps://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202411.1837/v1.

- Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhan, J.; Cheng, X.; Huang, H.; et al. The dawn of a new Era: mRNA vaccines in colorectal cancer immunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024, 132, 112037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldo, B.A. Immune- and Non-Immune-Mediated Adverse Effects of Monoclonal Antibody Therapy: A Survey of 110 Approved Antibodies. Antibodies (Basel). 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, S.H.C.; Mohan, G.S.; Elhaddad, A.; Lehmann, L. Cytokine Release Syndrome and Associated Acute Toxicities in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Immune Effector Cell Therapy or Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 841117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peaytt, R.; Parsons, L.B.; Siler, D.; Matthews, R.; Li, B.; Bell, D.; et al. The impact of early versus late tocilizumab administration in patients with cytokine release syndrome secondary to immune effector cell therapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2023, 29, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenVAERS. VAERS COVID Vaccine Adverse Event Reports. https://openvaerscom/covid-data. 2024;https://openvaers.com/covid-data.

- word, CO. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindataorg/grapher/covid-vaccine-doses-by-manufacturer?country=European+Union~HUN~USA. 2024.

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M.; Hasell, J.; Appel, C.; et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat Hum Behav. 2021, 5, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data. covid-vaccine-doses-by-manufacturer. https://ourworldindataorg/grapher/covid-vaccine-doses-by-manufacturer?time=2021-01-12latest&country=European+Union~USA. https://ourworldindataorg/covid-vaccinations. 2024.

- Rhodes, P.; Parry, P.I. Pharmaceutical product recall and educated hesitancy towards new drugs and novel vaccines. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 2024, 35, 317–333. [Google Scholar]

- VAERS. VAERS IDs. https://vaershhsgov/data/datasetshtml. 2023.

- Institute, P.E. Safety report. https://wwwpeide/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/newsroom-en/dossiers/safety-reports/safety-report-27-december-2020-31-march-2022pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=8. 2022.

- Zhou, F.; Hu, T.J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Lai, K.; Chen, J.H.; Zhou, X.H. The association of intensity and duration of non-pharmacological interventions and implementation of vaccination with COVID-19 infection, death, and excess mortality: Natural experiment in 22 European countries. J Infect Public Health. 2022, 15, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostert, S.; Hoogland, M.; Huibers, M.; Kaspers, G. Excess mortality across countries in the Western World since the COVID-19 pandemic: ‘Our World in Data’ estimates of January 2020 to December 2022. BMJ Public Health. 2024, 2, e000282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayano, T.; Sasanami, M.; Nishiura, H. Science-based exit from stringent countermeasures against COVID-19: Mortality prediction using immune landscape between 2021 and 2022 in Japan. Vaccine X. 2024, 20, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, S.H.; Lee, J.H.; Chapman, D.A.; Sabo, R.T.; Zimmerman, E. Excess Death Rates by State During the COVID-19 Pandemic: United States, 2020‒2023. Am J Public Health. 2024, 114, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibo, M.; Kojima, S.; Fujisawa, A.; Kikuchi, T.; Fukushima, M. Increased Age-Adjusted Cancer Mortality After the Third mRNA-Lipid Nanoparticle Vaccine Dose During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan. Cureus. 2024, 16, e57860. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, P.; Parry, P.I. Pharmaceutical product recall and educated hesitancy towards new drugs and novel vaccines. International Journal of Risk & Safety in Medicine. 2024, 0, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Szebeni, J.; Storm, G.; Ljubimova, J.Y.; Castells, M.; Phillips, E.J.; Turjeman, K.; et al. Applying lessons learned from nanomedicines to understand rare hypersensitivity reactions to mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Nat Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmaker, L.; Witzigmann, D.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Verbeke, R.; Kersten, G.; Jiskoot, W.; et al. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int J Pharm. 2021, 601, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebeni, J.; Kiss, B.; Bozo, T.; Turjeman, K.; Levi-Kalisman, Y.; Barenholz, Y.; et al. Insights into the Structure of Comirnaty Covid-19 Vaccine: A Theory on Soft, Partially Bilayer-Covered Nanoparticles with Hydrogen Bond-Stabilized mRNA-Lipid Complexes. ACS Nano. 2023, 17, 13147–13157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brader, M.L.; Williams, S.J.; Banks, J.M.; Hui, W.H.; Zhou, Z.H.; Jin, L. Encapsulation state of messenger RNA inside lipid nanoparticles. Biophys J. 2021, 120, 2766–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Wappelhorst, C.N.; Jensen, E.L.; Chi, Y.T.; Rouse, J.C.; Zou, Q. Elucidation of lipid nanoparticle surface structure in mRNA vaccines. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 16744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A.K.; Hafez, I.M.; Baoukina, S.; Belliveau, N.M.; Zhigaltsev, I.V.; Afshinmanesh, E.; et al. Lipid Nanoparticles Containing siRNA Synthesized by Microfluidic Mixing Exhibit an Electron-Dense Nanostructured Core. J Phys Chem C Nanomater Interfaces. 2012, 116, 18440–18450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, T.; Gotz, K.; Vogel, C.; Frohlich, E.; Scheurer, A.; Porcar, L.; et al. Mesoscopic Structure of Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations for mRNA Drug Delivery: Comirnaty and Drug-Free Dispersions. ACS Nano. 2024, 18, 9746–9764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Tuyishime, S.; Muramatsu, H.; Kariko, K.; Mui, B.L.; Tam, Y.K.; et al. Expression kinetics of nucleoside-modified mRNA delivered in lipid nanoparticles to mice by various routes. J Control Release. 2015, 217, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segalla, G. Apparent Cytotoxicity and Intrinsic Cytotoxicity of Lipid Nanomaterials Contained in a COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine. International Journal of Vaccine Theory Practice and Research. 2023, 3, 957–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Golubovic, A.; Xu, S.; Pan, A.; Li, B. Rational design and combinatorial chemistry of ionizable lipids for RNA delivery. J Mater Chem B. 2023, 11, 6527–6539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, J.L. A review of the scientific literature on experimental toxicity studies of COVID-19 vaccines, with special attention to publications in toxicology journals. Arch Toxicol. 2024, 98, 3603–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamanzi, A.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Liu, F.; Berti, R.; Wang, B.; et al. Quantitative Visualization of Lipid Nanoparticle Fusion as a Function of Formulation and Process Parameters. ACS Nano. 2024, 18, 18191–18201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ltd PAP. Nonclinical Evaluation Report: BNT162b2 [mRNA] COVID-19 vaccine (COMIRNATYTM). https://wwwtgagovau/sites/default/files/foi-2389-06pdf. 2021;https://t.co/Zrhakh7Xgv.

- Sarri, C.A.; Papadopoulos, G.E.; Papa, A.; Tsakris, A.; Pervanidou, D.; Baka, A.; et al. Amino acid signatures in the HLA class II peptide-binding region associated with protection/susceptibility to the severe West Nile Virus disease. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0205557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N.; Weissman, D.; Whitehead, K.A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granneman, S.; Tollervey, D. Building ribosomes: even more expensive than expected? Curr Biol. 2007, 17, R415–R417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonenberg, N.; Hinnebusch, A.G. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009, 136, 731–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henras, A.K.; Plisson-Chastang, C.; O'Donohue, M.F.; Chakraborty, A.; Gleizes, P.E. An overview of pre-ribosomal RNA processing in eukaryotes. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015, 6, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito Querido, J.; Diaz-Lopez, I.; Ramakrishnan, V. The molecular basis of translation initiation and its regulation in eukaryotes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentilella, A.; Kozma, S.C.; Thomas, G. A liaison between mTOR signaling, ribosome biogenesis and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015, 1849, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seneff, S.; Nigh, G.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; McCullough, P.A. Innate immune suppression by SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccinations: The role of G-quadruplexes, exosomes, and MicroRNAs. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022, 164, 113008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kariko, K.; Buckstein, M.; Ni, H.; Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005, 23, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariko, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Welsh, F.A.; Ludwig, J.; Kato, H.; Akira, S.; et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA yields superior nonimmunogenic vector with increased translational capacity and biological stability. Mol Ther. 2008, 16, 1833–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.R.; Muramatsu, H.; Jha, B.K.; Silverman, R.H.; Weissman, D.; Kariko, K. Nucleoside modifications in RNA limit activation of 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthetase and increase resistance to cleavage by RNase L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 9329–9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariko, K.; Muramatsu, H.; Ludwig, J.; Weissman, D. Generating the optimal mRNA for therapy: HPLC purification eliminates immune activation and improves translation of nucleoside-modified, protein-encoding mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andries, O.; Mc Cafferty, S.; De Smedt, S.C.; Weiss, R.; Sanders, N.N.; Kitada, T. N(1)-methylpseudouridine-incorporated mRNA outperforms pseudouridine-incorporated mRNA by providing enhanced protein expression and reduced immunogenicity in mammalian cell lines and mice. J Control Release. 2015, 217, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.J.; Kim, D.; Kang, S.; Li, K.; Cha, I.; Sasaki, A.; et al. Viral codon optimization on SARS-CoV-2 Spike boosts immunity in the development of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. J Med Virol. 2023, 95, e29183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachaev, Z.M.; Lebedeva, L.A.; Kozlov, E.N.; Shidlovskii, Y.V. Interplay of mRNA capping and transcription machineries. Biosci Rep. 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warminski, M.; Depaix, A.; Ziemkiewicz, K.; Spiewla, T.; Zuberek, J.; Drazkowska, K.; et al. Trinucleotide cap analogs with triphosphate chain modifications: synthesis, properties, and evaluation as mRNA capping reagents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 10788–10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muttach, F.; Muthmann, N.; Rentmeister, A. Synthetic mRNA capping. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2017, 13, 2819–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imprachim, N.; Yosaatmadja, Y.; Newman, J.A. Crystal structures and fragment screening of SARS-CoV-2 NSP14 reveal details of exoribonuclease activation and mRNA capping and provide starting points for antiviral drug development. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S.J. mRNA vaccine sequence and structure design and optimization: Advances and challenges. J Biol Chem. 2024, 301, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, C.; Emmaneel, M.; Nelissen, F.H.T.; Roosenboom, L.W.M.; Petrova, Y.; Elzokla, O.; et al. Decoupled degradation and translation enables noise modulation by poly(A) tails. Cell Syst. 2024, 15, 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, S.; Lutz, J.; Kowalczyk, A.; Schlake, T.; Heidenreich, R. RNActive(R) Technology: Generation and Testing of Stable and Immunogenic mRNA Vaccines. Methods Mol Biol. 2017, 1499, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, S.; Lutz, J.; Muhe, J.; Kowalczyk, A.; Schlake, T.; Heidenreich, R. Sequence-Optimized mRNA Vaccines Against Infectious Disease. Methods Mol Biol. 2024, 2786, 183–203. [Google Scholar]

- Kramps, T. Introduction to RNA Vaccines Post COVID-19. Methods Mol Biol. 2024, 2786, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Hu, J.; Jiao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Pan, X.; et al. mRNA vaccines in the context of cancer treatment: from concept to application. J Transl Med. 2025, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garneau, N.L.; Wilusz, J.; Wilusz, C.J. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, R.; Jain, A.; Nakajima, R.; Jasinskas, A.; Kahn, S.; Palma, A.; et al. Distinct SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Responses Elicited by Natural Infection and mRNA Vaccination. bioRxiv. 2021, 2021, 440089. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, A.; Muecksch, F.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Wang, Z.; Finkin, S.; Gaebler, C.; et al. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain antibody evolution after mRNA vaccination. Nature. 2021, 600, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Saleh, H.; Abo-Halawa, B.Y.; Younes, S.; Younes, N.; Al-Sadeq, D.W.; Shurrab, F.M.; et al. Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 are higher but decline faster in mRNA vaccinees compared to individuals with natural infection. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2022, 29, taac130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Muecksch, F.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Finkin, S.; Viant, C.; Gaebler, C.; et al. Naturally enhanced neutralizing breadth against SARS-CoV-2 one year after infection. Nature. 2021, 595, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embgenbroich, M.; Burgdorf, S. Current Concepts of Antigen Cross-Presentation. Front Immunol. 2018, 9, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Nigh, G.; McCullough, P.A.; Seneff, S. Autoimmune and Neoplastic Outcomes After the mRNA Vaccination: The Role of T Regulatory Cell Responses. International Journal of Vaccine Theory, Practice, and Research. 2024, 3, 1395–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, E.; Morioka, H.; Kikuchi, T.; Fukushima, M. Behavioral and Health Outcomes of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case-Control Study in Japanese Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Cureus. 2024, 16, e75652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Perincheri, S.; Fleming, T.; Poulson, C.; Tiffany, B.; Bremner, R.M.; et al. Cutting Edge: Circulating Exosomes with COVID Spike Protein Are Induced by BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) Vaccination prior to Development of Antibodies: A Novel Mechanism for Immune Activation by mRNA Vaccines. J Immunol. 2021, 207, 2405–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.J.; Atai, N.A.; Cacciottolo, M.; Nice, J.; Salehi, A.; Guo, C.; et al. Exosome-mediated mRNA delivery in vivo is safe and can be used to induce SARS-CoV-2 immunity. J Biol Chem. 2021, 297, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciottolo, M.; Nice, J.B.; Li, Y.; LeClaire, M.J.; Twaddle, R.; Mora, C.L.; et al. Exosome-Based Multivalent Vaccine: Achieving Potent Immunization, Broadened Reactivity, and Strong T-Cell Responses with Nanograms of Proteins. Microbiol Spectr. 2023, 11, e0050323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Naradikian, M.S.; Parkhouse, K.; Cain, D.W.; Jones, L.; et al. Nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccines induce potent T follicular helper and germinal center B cell responses. J Exp Med. 2018, 215, 1571–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zan, H.; Zhang, J.; Ardeshna, S.; Xu, Z.; Park, S.R.; Casali, P. Lupus-prone MRL/faslpr/lpr mice display increased AID expression and extensive DNA lesions, comprising deletions and insertions, in the immunoglobulin locus: concurrent upregulation of somatic hypermutation and class switch DNA recombination. Autoimmunity. 2009, 42, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Smith, D.; Aviszus, K.; Detanico, T.; Heiser, R.A.; Wysocki, L.J. Somatic hypermutation as a generator of antinuclear antibodies in a murine model of systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2010, 207, 2225–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakuma, H.; Okumura, F.; Miyabe, S.; Sugiura, M.; Joh, T.; Shimozato, K.; et al. Analysis of VH gene rearrangement and somatic hypermutation in Sjogren's syndrome and IgG4-related sclerosing sialadenitis. Scand J Immunol. 2010, 72, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, N.S.; Hazanov, H.; Barak, M.; Edelman, H.; Hess, S.; Shcolnik, H.; et al. Somatic hypermutation and antigen-driven selection of B cells are altered in autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun. 2010, 35, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, F.; Sakuma, H.; Nakazawa, T.; Hayashi, K.; Naitoh, I.; Miyabe, K.; et al. Analysis of VH gene rearrangement and somatic hypermutation in type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis. Pathol Int. 2012, 62, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Herrmann, M.; Winkler, T.H. The role of somatic hypermutation in the generation of pathogenic antibodies in SLE. Autoimmunity. 2013, 46, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Richards, A.; Barrasa, M.I.; Hughes, S.H.; Young, R.A.; Jaenisch, R. Reverse-transcribed SARS-CoV-2 RNA can integrate into the genome of cultured human cells and can be expressed in patient-derived tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, M.; Olofsson Falla, F.; Yang, D.; Barghouth, M.; Luan, C.; Rasmussen, M.; et al. Intracellular Reverse Transcription of Pfizer BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine BNT162b2 In Vitro in Human Liver Cell Line. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022, 44, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramouly, G.; Zhao, J.; McDevitt, S.; Rusanov, T.; Hoang, T.; Borisonnik, N.; et al. Poltheta reverse transcribes RNA and promotes RNA-templated DNA repair. Sci Adv. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, H.A. Comment on Alden et al. Intracellular Reverse Transcription of Pfizer BioNTech COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine BNT162b2 In Vitro in Human Liver Cell Line. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brogna, C.; Cristoni, S.; Marino, G.; Montano, L.; Viduto, V.; Fabrowski, M.; et al. Detection of recombinant Spike protein in the blood of individuals vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2: Possible molecular mechanisms. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2023, 17, e2300048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauson, A.J.; Casimero, F.V.C.; Siddiquee, Z.; Stone, J.R. Duration of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine persistence and factors associated with cardiac involvement in recently vaccinated patients. NPJ Vaccines. 2023, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndeupen, S.; Qin, Z.; Jacobsen, S.; Bouteau, A.; Estanbouli, H.; Igyarto, B.Z. The mRNA-LNP platform's lipid nanoparticle component used in preclinical vaccine studies is highly inflammatory. iScience. 2021, 24, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanworth, S.J.; New, H.V.; Apelseth, T.O.; Brunskill, S.; Cardigan, R.; Doree, C.; et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on supply and use of blood for transfusion. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e756–e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Yan, Y.; Wang, L. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Coronaviruses and Blood Safety. Transfus Med Rev. 2020, 34, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhou, S.; Lahjouji, K.; Masrar, A. Blood donor eligibility after COVID-19 vaccination: the current state of recommendations. Pan Afr Med J. 2021, 40, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.W.; Bibb, L.A.; Savani, B.N.; Booth, G.S. Refusing blood transfusions from COVID-19-vaccinated donors: are we repeating history? Br J Haematol. 2022, 196, 585–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunain, R.; Uday, U.; Rackimuthu, S.; Nawaz, F.A.; Narain, K.; Essar, M.Y.; et al. Effects of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination on blood donation and blood banks in India. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022, 78, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubinian, N.H.; Greene, J.; Liu, V.X.; Lee, C.; Mark, D.G.; Vinson, D.R.; et al. Clinical outcomes in hospitalized plasma and platelet transfusion recipients prior to and following widespread blood donor SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. Transfusion. 2024, 64, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonker, L.M.; Swank, Z.; Bartsch, Y.C.; Burns, M.D.; Kane, A.; Boribong, B.P.; et al. Circulating Spike Protein Detected in Post-COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine Myocarditis. Circulation. 2023, 147, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, N.; De Mejia, C.M.; Heffes-Doon, A.; Lin, X.; Botros, B.; Gurzenda, E.; et al. Biodistribution of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in human breast milk. EBioMedicine. 2023, 96, 104800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulroney, T.E.; Poyry, T.; Yam-Puc, J.C.; Rust, M.; Harvey, R.F.; Kalmar, L.; et al. N(1)-methylpseudouridylation of mRNA causes +1 ribosomal frameshifting. Nature. 2024, 625, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boros, L.G.; Kyriakopoulos, A.M.; Brogna, C.; Piscopo, M.; McCullough, P.A.; Seneff, S. Long-lasting, biochemically modified mRNA, and its frameshifted recombinant spike proteins in human tissues and circulation after COVID-19 vaccination. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2024, 12, e1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safra, M.; Tamari, Z.; Polak, P.; Shiber, S.; Matan, M.; Karameh, H.; et al. Altered somatic hypermutation patterns in COVID-19 patients classifies disease severity. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1031914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob-Dolan, C.; Lifton, M.; Powers, O.C.; Miller, J.; Hachmann, N.P.; Vu, M.; et al. B cell somatic hypermutation following COVID-19 vaccination with Ad26.COV2.S. iScience. 2024, 27, 109716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fay, M.M.; Lyons, S.M.; Ivanov, P. RNA G-Quadruplexes in Biology: Principles and Molecular Mechanisms. J Mol Biol. 2017, 429, 2127–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, E.; Carrabba, M.; Milligan, R.; Kavanagh Williamson, M.; Beltrami, A.P.; Gupta, K.; et al. The SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein disrupts human cardiac pericytes function through CD147 receptor-mediated signalling: a potential non-infective mechanism of COVID-19 microvascular disease. Clin Sci (Lond). 2021, 135, 2667–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perico, L.; Morigi, M.; Pezzotta, A.; Locatelli, M.; Imberti, B.; Corna, D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces lung endothelial cell dysfunction and thrombo-inflammation depending on the C3a/C3a receptor signalling. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 11392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U.; Kariko, K.; Tureci, O. mRNA-based therapeutics--developing a new class of drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobbelaar, L.M.; Venter, C.; Vlok, M.; Ngoepe, M.; Laubscher, G.J.; Lourens, P.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S1 induces fibrin(ogen) resistant to fibrinolysis: implications for microclot formation in COVID-19. Biosci Rep. 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.; Herman, A.; Pullen, A.M.; Kubo, R.; Kappler, J.W.; Marrack, P. The V beta-specific superantigen staphylococcal enterotoxin B: stimulation of mature T cells and clonal deletion in neonatal mice. Cell. 1989, 56, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noval Rivas, M.; Porritt, R.A.; Cheng, M.H.; Bahar, I.; Arditi, M. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Long COVID: The SARS-CoV-2 Viral Superantigen Hypothesis. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 941009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, N.; Ratzon, R.; Hazan, I.; Zimmerman, D.R.; Singer, S.R.; Wasser, J.; et al. Multisystemic inflammatory syndrome in children and the BNT162b2 vaccine: a nationwide cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2024, 183, 3319–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Llera, A.; Malchiodi, E.L.; Mariuzza, R.A. The structural basis of T cell activation by superantigens. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999, 17, 435–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, A.; Leonardi, A. Superantigens and SARS-CoV-2. Pathogens. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.; Bhardwaj, N. Super(antigen) target for SARS-CoV-2. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2021, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubinski, B.; Whittaker, G.R. The SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site: natural selection or smoking gun? Lancet Microbe. 2023, 4, e570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, F.; Connes, P. Morphology and Function of Red Blood Cells in COVID-19 Patients: Current Overview 2023. Life (Basel). 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, M.; Ibershoff, L.; Zacher, J.; Bros, J.; Tomschi, F.; Diebold, K.F.; et al. Even patients with mild COVID-19 symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 infection show prolonged altered red blood cell morphology and rheological parameters. J Cell Mol Med. 2022, 26, 3022–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschi, C.; Scheim, D.E.; Bancod, A.; Militello, M.; Bideau, M.L.; Colson, P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Induces Hemagglutination: Implications for COVID-19 Morbidities and Therapeutics and for Vaccine Adverse Effects. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheim, D.E.; Vottero, P.; Santin, A.D.; Hirsh, A.G. Sialylated Glycan Bindings from SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein to Blood and Endothelial Cells Govern the Severe Morbidities of COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tian, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Zheng, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein potentiates platelet aggregation via upregulating integrin alphaIIbbeta3 outside-in signaling pathway. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, C.C.; Basnet, N.; Bodakuntla, S.; Alvarez-Brecht, P.; Nichols, S.; Martinez-Sanchez, A.; et al. Direct Cryo-ET observation of platelet deformation induced by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzak, B.; Rozalski, M.; Przygodzki, T.; Boncler, M.; Wojkowska, D.; Kosmalski, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Neutralizing Anti-Spike Protein Antibodies Modulate Blood Platelet Function. Int J Mol Sci.

- Degenfeld-Schonburg, L.; Sadovnik, I.; Smiljkovic, D.; Peter, B.; Stefanzl, G.; Gstoettner, C.; et al. Coronavirus Receptor Expression Profiles in Human Mast Cells, Basophils, and Eosinophils. Cells. 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghihi, H. CD147 as an alternative binding site for the spike protein on the surface of SARS-CoV-2. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020, 24, 11992–11994. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Lian, J.Q.; Du, P.; et al. CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020, 5, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, T.; Kaur, I.; Aleya, L.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, S.; Sharma, N.; et al. CD147-spike protein interaction in COVID-19: Get the ball rolling with a novel receptor and therapeutic target. Sci Total Environ. 2022, 808, 152072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodowski, M.; Pierpaoli, M.; Janik, M.; Kowalski, M.; Ficek, M.; Slepski, P.; et al. Enhanced susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD protein assay targeted by cellular receptors ACE2 and CD147: Multivariate data analysis of multisine impedimetric response. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2022, 370, 132427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, L.R.; Estivariz, C.F.; Sutter, R.W. Vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis: a review of the epidemiology and estimation of the global burden. J Infect Dis. 2014, 210 (Suppl 1), S380–S389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraff, L.J.; Manclark, C.R.; Cherry, J.D.; Christenson, P.; Marcy, S.M. Analyses of adverse reactions to diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis vaccine by vaccine lot, endotoxin content, pertussis vaccine potency and percentage of mouse weight gain. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989, 8, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipp, M.; Goldbach, M.; Greenberg, S.; Gold, R. Effect of needle change and air bubble in syringe on minor adverse reactions associated with diphtheria-tetanus toxoids-pertussis-polio vaccination in infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990, 9, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Golaz, A.; Hardy, I.R.; Glushkevich, T.G.; Areytchiuk, E.K.; Deforest, A.; Strebel, P.; et al. Evaluation of a single dose of diphtheria-tetanus toxoids among adults in Odessa, Ukraine, 1995: immunogenicity and adverse reactions. J Infect Dis. 2000, 181 (Suppl 1), S203–S207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Relyveld, E.H.; Bizzini, B.; Gupta, R.K. Rational approaches to reduce adverse reactions in man to vaccines containing tetanus and diphtheria toxoids. Vaccine. 1998, 16, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.S.; Kalman, D.D. Successful vaccination with tetanus and diphtheria and acelluar pertussis vaccine after adverse reaction to diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis vaccine or diphtheria and tetanus vaccine in pediatric patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019, 123, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullis, P.R.; Hope, M.J. Lipid Nanoparticle Systems for Enabling Gene Therapies. Mol Ther. 2017, 25, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullis, P.R.; Felgner, P.L. The 60-year evolution of lipid nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhiz, H.; Brenner, J.S.; Patel, P.N.; Papp, T.E.; Shahnawaz, H.; Li, Q.; et al. Added to pre-existing inflammation, mRNA-lipid nanoparticles induce inflammation exacerbation (IE). J Control Release. 2022, 344, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoke, D.; Kovacs, G.; Kemecsei, E.; Balint, L.; Szotak-Ajtay, K.; Aradi, P.; et al. Nucleoside-modified VEGFC mRNA induces organ-specific lymphatic growth and reverses experimental lymphedema. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchordoquy, T.; Artzi, N.; Balyasnikova, I.V.; Barenholz, Y.; La-Beck, N.M.; Brenner, J.S.; et al. Mechanisms and Barriers in Nanomedicine: Progress in the Field and Future Directions. ACS Nano. 2024, 18, 13983–13999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Hoorn, D.; Aitha, A.; Breier, D.; Peer, D. The immunostimulatory nature of mRNA lipid nanoparticles. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2024, 205, 115175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, W. Anaphylatoxins: possible roles in disease. Complement. 1986, 3, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schanzenbacher, J.; Kohl, J.; Karsten, C.M. Anaphylatoxins spark the flame in early autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 958392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alving, C.R.; Kinsky, S.C.; Haxby, J.A.; Kinsky, C.B. Antibody binding and complement fixation by a liposomal model membrane. Biochemistry. 1969, 8, 1582–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szebeni, J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy caused by liposomes, micellar carriers of intravenous drugs and radiocontrast agents. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carr Syst. 2001, 18, 567–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: a new class of drug-induced acute immune toxicity. Toxicology. 2005, 216, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, J. Complement activation-related pseudoallergy: A stress reaction in blood triggered by nanomedicines and biologicals. Mol Immunol. 2014, 61, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezsi, L.; Meszaros, T.; Kozma, G.; M, H.V.; Olah, C.Z.; Szabo, M.; et al. A naturally hypersensitive porcine model may help understand the mechanism of COVID-19 mRNA vaccine-induced rare (pseudo) allergic reactions: complement activation as a possible contributing factor. Geroscience. 2022, 44, 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vrieze, J. Suspicions grow that nanoparticles in Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine trigger rare allergic reactions. Science. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, J.; Fontana, J.L.; Wassef, N.M.; Mongan, P.D.; Morse, D.S.; Dobbins, D.E.; et al. Hemodynamic changes induced by liposomes and liposome-encapsulated hemoglobin in pigs: a model for pseudoallergic cardiopulmonary reactions to liposomes. Role of complement and inhibition by soluble CR1 and anti-C5a antibody. Circulation. 1999, 99, 2302–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, I.; Weisser, K.; Gaston-Tischberger, D.; Mahler, V.; Keller-Stanislawski, B. Anaphylactic reactions after COVID-19 vaccination in Germany. Allergol Select. 2023, 7, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barta, B.A.; Radovits, T.; Dobos, A.B.; Tibor Kozma, G.; Meszaros, T.; Berenyi, P.; et al. Comirnaty-induced cardiopulmonary distress and other symptoms of complement-mediated pseudo-anaphylaxis in a hyperimmune pig model: Causal role of anti-PEG antibodies. Vaccine X. 2024, 19, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Lai, S.K. Anti-PEG immunity: emergence, characteristics, and unaddressed questions. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2015, 7, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, E.; Chen, B.M.; Su, Y.C.; Chang, Y.C.; Cheng, T.L.; Barenholz, Y.; et al. Premature Drug Release from Polyethylene Glycol (PEG)-Coated Liposomal Doxorubicin via Formation of the Membrane Attack Complex. ACS Nano. 2020, 14, 7808–7822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, G.T.; Shimizu, T.; Ishida, T.; Szebeni, J. Anti-PEG antibodies: Properties, formation, testing and role in adverse immune reactions to PEGylated nano-biopharmaceuticals. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020, 154–155, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabizon, A.; Szebeni, J. Complement Activation: A Potential Threat on the Safety of Poly(ethylene glycol)-Coated Nanomedicines. ACS Nano. 2020, 14, 7682–7688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USFDA. Guidance for Industry: Immunogenicity Assessment for Therapeutic Protein Products. https://wwwfdagov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/immunogenicity-assessment-therapeutic-protein-products. 2014;FDA-2013-D-0092.

- Bakos, T.; Meszaros, T.; Kozma, G.T.; Berenyi, P.; Facsko, R.; Farkas, H.; et al. mRNA-LNP COVID-19 Vaccine Lipids Induce Complement Activation and Production of Proinflammatory Cytokines: Mechanisms, Effects of Complement Inhibitors, and Relevance to Adverse Reactions. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, K.; Castano, D.; Gomez Atria, D.; Oguin, T.H.; Wang, S., 3rd; Manzoni, T.B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccines Foster Potent Antigen-Specific Germinal Center Responses Associated with Neutralizing Antibody Generation. Immunity. 2020, 53, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameh, M.G.; Tombacz, I.; Bettini, E.; Lederer, K.; Sittplangkoon, C.; Wilmore, J.R.; et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity. 2021, 54, 2877–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alameh, M.G.; Tombacz, I.; Bettini, E.; Lederer, K.; Sittplangkoon, C.; Wilmore, J.R.; et al. Lipid nanoparticles enhance the efficacy of mRNA and protein subunit vaccines by inducing robust T follicular helper cell and humoral responses. Immunity. 2022, 55, 1136–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmrich, E.; McNeil, S. Active ingredient vs excipient debate for nanomedicines. Nat Nanotechnol. 2023, 18, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akinc, A.; Maier, M.A.; Manoharan, M.; Fitzgerald, K.; Jayaraman, M.; Barros, S.; et al. The Onpattro story and the clinical translation of nanomedicines containing nucleic acid-based drugs. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalby, B.; Cates, S.; Harris, A.; Ohki, E.C.; Tilkins, M.L.; Price, P.J.; et al. Advanced transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 reagent: primary neurons, siRNA, and high-throughput applications. Methods. 2004, 33, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraresso, F.; Badior, K.; Seadler, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wietrzny, A.; Cau, M.F.; et al. Protein is expressed in all major organs after intravenous infusion of mRNA-lipid nanoparticles in swine. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2024, 32, 101314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateev, I.; Seregina, K.; Ivanov, R.; Reshetnikov, V. Biodistribution of RNA Vaccines and of Their Products: Evidence from Human and Animal Studies. Biomedicines. 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachmann, P.J. The amplification loop of the complement pathways. Adv Immunol. 2009, 104, 115–149. [Google Scholar]

- lebel, P. COMIRNATY® (COVID-19 Vaccine, mRNA) suspension for injection, for intramuscular use. https://labelingpfizercom/ShowLabelingaspx?id=16351#section-6. 1023.

- Dempsey, P.W.; Allison, M.E.; Akkaraju, S.; Goodnow, C.C.; Fearon, D.T. C3d of complement as a molecular adjuvant: bridging innate and acquired immunity. Science. 1996, 271, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills-Karp, M. Complement activation pathways: a bridge between innate and adaptive immune responses in asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2007, 4, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, G.T.; Meszaros, T.; Berenyi, P.; Facsko, R.; Patko, Z.; Olah, C.Z.; et al. Role of anti-polyethylene glycol (PEG) antibodies in the allergic reactions to PEG-containing Covid-19 vaccines: Evidence for immunogenicity of PEG. Vaccine. 2023, 41, 4561–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, J.M.; Singh, G.; Tcheou, J.; Srivastava, K.; Gleason, C.; Muramatsu, H.; et al. mRNA-1273 but not BNT162b2 induces antibodies against polyethylene glycol (PEG) contained in mRNA-based vaccine formulations. Vaccine. 2022, 40, 6114–6124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Lee, W.S.; Pilkington, E.H.; Kelly, H.G.; Li, S.; Selva, K.J.; et al. Anti-PEG Antibodies Boosted in Humans by SARS-CoV-2 Lipid Nanoparticle mRNA Vaccine. ACS Nano. 2022, 16, 11769–11780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bavli, Y.; Chen, B.M.; Gross, G.; Hershko, A.; Turjeman, K.; Roffler, S.; et al. Anti-PEG antibodies before and after a first dose of Comirnaty(R) (mRNA-LNP-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine). J Control Release. 2023, 354, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.H.Y.; Leung, J.; Zhang, Y.; Strong, C.; Basha, G.; Momeni, A.; et al. Induction of Bleb Structures in Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations of mRNA Leads to Improved Transfection Potency. Adv Mater. 2023, 35, e2303370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfizer, Biontech. Comirnaty Original Omicron BA.4-5. https://labelingpfizercom/ShowLabelingaspx?id=19823. 2023.

- Boros, L.G.; Seneff, S.; Turi, M.; Palcsu, L.; Zubarev, R.A. Active involvement of compartmental, inter- and intramolecular deuterium disequilibrium in adaptive biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024, 121, e2412390121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korchinsky, N.; Davis, A.M.; Boros, L.G. Nutritional deuterium depletion and health: a scoping review. Metabolomics. 2024, 20, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.S.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hsieh, C.L.; Abiona, O.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoult, D. Confirmation of the presence of vaccine DNA in the Pfizer anti-COVID-19 vaccine. Hal Open Science. 2024, 04778576. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Ki-Yeob, J. Foreign Materials in Blood Samples of Recipients of COVID19 Vaccines. International Journal of Vaccine Theory, Practice, and Research. 2022, 2, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.J.; Kim, A.; Kim, K. Method of Replication-Competent Plasmid DNA from COVID-19 mRNA Vaccines for Quality Control. Journal of High School Science. 2024, 8, 427–439. [Google Scholar]

- Kämmerer, U.; Schulz, V.; Steger, K. BioNTech RNA-Based COVID-19 Injections Contain Large Amounts Of Residual DNA Including An SV40 Promoter/Enhancer Sequence. Science, Public Health Policy and the Law. 2024, 5, 2019–2024. [Google Scholar]

- CGC. Case briefing document. http://ukcitizen, 2024.

- Doherty, M.; Whicher, J.T.; Dieppe, P.A. Activation of the alternative pathway of complement by monosodium urate monohydrate crystals and other inflammatory particles. Ann Rheum Dis. 1983, 42, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, I.J.; Mansen, C.; Kolb, L.M.; Kolb, W.P. Activation of the fifth component of human complement (C5) induced by monosodium urate crystals: C5 convertase assembly on the crystal surface. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1982, 24, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fields, T.R.; Abramson, S.B.; Weissmann, G.; Kaplan, A.P.; Ghebrehiwet, B. Activation of the alternative pathway of complement by monosodium urate crystals. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1983, 26, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyi, L.; Szebeni, J.; Savay, S.; Bodo, M.; Bunger, R.; Alving, C. ; editors. When cholesterol kills: fatal complement activation-mediated circulatory distress provoked by cholesterol-enriched liposomes. FASEB, 2000; 20814-3998. [Google Scholar]

- Baranyi, L.; Szebeni, J.; Savay, S.; Bodo, M.; Basta, M.; Bentley, T.B.; et al. Complement-Dependent Shock and Tissue Damage Induced by Intravenous Injection of Cholesterol-Enriched Liposomes in Rats. Journal of Applied Research. 2003, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak, M.Z.; Lee, H.; Wysoczynski, M.; Wan, W.; Marlicz, W.; Laughlin, M.J.; et al. Novel insight into stem cell mobilization-plasma sphingosine-1-phosphate is a major chemoattractant that directs the egress of hematopoietic stem progenitor cells from the bone marrow and its level in peripheral blood increases during mobilization due to activation of complement cascade/membrane attack complex. Leukemia. 2010, 24, 976–985. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, C.P.; de Groot, K.; van Kamp, G. Activation of complement C3 by different calcium phosphate powders. Biomaterials. 1983, 4, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselbacher, P. Binding of immunoglobulin and activation of complement by asbestos fibers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1979, 64, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szebeni, J.; Alving, C.R.; Savay, S.; Barenholz, Y.; Priev, A.; Danino, D.; et al. Formation of complement-activating particles in aqueous solutions of Taxol: possible role in hypersensitivity reactions. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001, 1, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Bouteau, A.; Herbst, C.; Igyarto, B.Z. Pre-exposure to mRNA-LNP inhibits adaptive immune responses and alters innate immune fitness in an inheritable fashion. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18, e1010830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes Angues, R.; Perea Bustos, Y. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination and the Multi-Hit Hypothesis of Oncogenesis. Cureus. 2023, 15, e50703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, U. Covid Vaccination and Turbo-Cancer. Multiple Tumors in Multiple Organs. https://wwwglobalresearchca/turbo-cancer-we-have-problem/5789172 2024.

- Wiedmeier-Nutor, J.E.; Iqbal, M.; Rosenthal, A.C.; Bezerra, E.D.; Garcia-Robledo, J.E.; Bansal, R.; et al. Response to COVID-19 Vaccination Post-CAR T Therapy in Patients With Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and Multiple Myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2023, 23, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekizawa, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Kobayashi, S.; Kozono, S.; Kobayashi, T.; Kawamura, Y.; et al. Rapid progression of marginal zone B-cell lymphoma after COVID-19 vaccination (BNT162b2): A case report. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022, 9, 963393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacionales, D.C.; Weinstein, J.S.; Yan, X.J.; Albesiano, E.; Lee, P.Y.; Kelly-Scumpia, K.M.; et al. B cell proliferation, somatic hypermutation, class switch recombination, and autoantibody production in ectopic lymphoid tissue in murine lupus. J Immunol. 2009, 182, 4226–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentilini, P.; Lindsay, J.C.; Konishi, N.; Fukushima, M.; Polykretis, P. A Case Report of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL)/Lymphoblastic Lymphoma (LBL) Following the Second Dose of Comirnaty®: An Analysis of the Potential Pathogenic Mechanism Based on of the Existing Literature. Preprints Org. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.B. The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965, 58, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menetrier-Caux, C.; Ray-Coquard, I.; Blay, J.Y.; Caux, C. Lymphopenia in Cancer Patients and its Effects on Response to Immunotherapy: an opportunity for combination with Cytokines? J Immunother Cancer. 2019, 7, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; El-Deiry, W.S. Transfected SARS-CoV-2 spike DNA for mammalian cell expression inhibits p53 activation of p21(WAF1), TRAIL Death Receptor DR5 and MDM2 proteins in cancer cells and increases cancer cell viability after chemotherapy exposure. Oncotarget. 2024, 15, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockert, J.A.; Gupta, A.; Herzog, B.; Yadav, S.S.; Tewari, A.K.; Yadav, K.K. Predictive value of pseudouridine in prostate cancer. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2019, 7, 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Stockert, J.A.; Weil, R.; Yadav, K.K.; Kyprianou, N.; Tewari, A.K. Pseudouridine as a novel biomarker in prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2021, 39, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y.L.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.G. RNA methylations in human cancers. Semin Cancer Biol. 2021, 75, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raszek, M.; Cowley, D.; Redwan, E.M.; Vladimir, N.; Uversky, V.N.; Rubio-Casillas, A. Exploring the possible link between the spike protein immunoglobulin G4 antibodies and cancer progression. Exploration of immunology. 2024, 4, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Shirjang, S.; Baradaran, B. Micro-RNAs: The new potential biomarkers in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and cancer therapy. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2015, 61, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.; Chang, Q.; Lu, H.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Chen, C. MicroRNA-873-5p suppresses cell malignant behaviors of thyroid cancer via targeting CXCL5 and regulating P53 pathway. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022, 18, 2065837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trifylli, E.M.; Kriebardis, A.G.; Koustas, E.; Papadopoulos, N.; Fortis, S.P.; Tzounakas, V.L.; et al. A Current Synopsis of the Emerging Role of Extracellular Vesicles and Micro-RNAs in Pancreatic Cancer: A Forward-Looking Plan for Diagnosis and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Goswami, J.; Baqui, A.H.; Doreski, P.A.; Perez-Marc, G.; Zaman, K.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of an mRNA-Based RSV PreF Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2023, 389, 2233–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moderna. Prescribing Information: Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine) Injectable suspension, for intramuscular use. https://wwwfdagov/media/179005/download?attachment=&utm_source=chatgptcom. 2024;https://www.fda.gov/media/179005/download?attachment=&utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- FDA. FDA Approves and Authorizes Updated mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines to Better Protect Against Currently Circulating Variants. https://wwwfdagov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-and-authorizes-updated-mrna-covid-19-vaccines-better-protect-against-currently. 2024;https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-and-authorizes-updated-mrna-covid-19-vaccines-better-protect-against-currently.

- Zhang, G.; Tang, T.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Liang, T. mRNA vaccines in disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023, 8, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladak, R.J.; He, A.J.; Huang, Y.H.; Ding, Y. The Current Landscape of mRNA Vaccines Against Viruses and Cancer-A Mini Review. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 885371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayour, E.J.; Boczkowski, D.; Mitchell, D.A.; Nair, S.K. Cancer mRNA vaccines: clinical advances and future opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024, 21, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Chen, B.; Wong, J. Evolution of the market for mRNA technology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 735–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Application Therapeutics, Research. Lipid Nanoparticles Market Size, Share & Industry Analysis, By Type (Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs), Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs), and Others). https://wwwfortunebusinessinsightscom/lipid-nanoparticles-market-106960. 2024;https://www.fortunebusinessinsights.com.

- mRNA Vaccine and Therapeutics Market Size & Share Analysis - Growth Trends & Forecasts (2024 - 2029) https://wwwmordorintelligencecom/industry-reports/mrna-vaccines-and-therapeutics-market. 2024;https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/mrna-vaccines-and-therapeutics-market.

- The hope accord. https://thehopeaccordorg/?utm_source=chatgptcom. 2024.

- Housfeld. COVID19 Inquiry: The treatment of the vaccine injured in this country has historically been a source of shame. https://wwwhausfeldcom/en-gb/news/covid19-inquiry-the-treatment-of-the-vaccine-injured-in-this-country-has-historically-been-a-source-of-shame/?utm_source=chatgptcom. 2025.

- Association, B.M. Engagement with the UK Covid-19 Inquiry. Module 4: Vaccines and therapeutics. 2025;https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/what-the-bma-is-doing/bma-engagement-with-the-uk-covid-19-inquiry?utm_source=chatgpt.com(https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/covid-19/what-the-bma-is-doing/bma-engagement-with-the-uk-covid-19-inquiry?utm_source=chatgpt.com).

- NVIC. Protecting Health and Informed Consent Rights Since 1982. https://wwwnvicorg/ 2025.

- Help. https://www.worldcouncilforhealth.org/. https://wwwworldcouncilforhealthorg/ [Internet]. 2025; https://www.worldcouncilforhealth.org/.

- The Times. State’s ‘fatal strategic flaws’ during Covid are laid bare. The Times https://wwwthetimescom/uk/healthcare/article/states-failure-to-protect-public-during-covid-laid-bare-p2tp93xvd?utm_source=chatgptcom®ion=global. 2024;Thursday July 18 2024.

- UK COVID-19 Inquiry. https://wwwgovuk/government/publications/uk-covid-19-inquiry-terms-of-reference. 2024.

- Litaker, J.R.; Lopez Bray, C.; Tamez, N.; Durkalski, W.; Taylor, R. COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptors, Refusers, and the Moveable Middle: A Qualitative Study from Central Texas. Vaccines (Basel). 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FDA. Considerations for Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Vaccine Safety in Pediatric Populations. VRBPAC Briefing Document. 2024;https://www.fda.gov/media/184301/download.

- Igyarto, B.Z.; Jacobsen, S.; Ndeupen, S. Future considerations for the mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccine platform. Curr Opin Virol. 2021, 48, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unique vaccine properties | Sections* | Collateral immune effects | Potential AEs complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Ribosomal synthesis of the spike protein fundamentally transforms antigen processing and presentation | 6.1. |

|

|

| 2) Multiple chemical modification of the mRNA increases its stability and translation efficacy | 6.2.1-6.2.6 | ||

| 3) The spike protein can be toxic | 6.4.1.-6.4.4 |

|

|

| 4) The LNP is pharmacologically active immune stimulant and mRNA transfectant | 6.5.1.-6.5.4 |

|

|

| 5) PEG on the LNP surface is immune reactive and immunogenic | 6.6.1-6.6.2 |

|

|

| 6) The mRNA-LNP is unstable in water | 6.7. |

|

|

| 7) The spike protein is stabilized by enrichment with proline and G-quadruplexes | 6.8 |

|

|

| 8) The injectable vaccine may contain contaminations with plasmid DNA and inorganic elements or complexes | 6.9 |

|

|

| Systemic toxicities | References |

|---|---|

| Complement activation | [12,16] |

| Endothelial inflammation, microvascular damage | [15,16,121,128,129] |

| Oxidative (mitochondrial) damage | [21,22,130] |

| Cytokine release | [17,28] |

| (Micro)thrombosis | [14,19,20,129] |

| Red blood cell aggregation | [29] |

| White cell activation and/or cytotoxicity | [23,24,30] |

| Platelet activation and/or coagulation abnormalities | [18,25] |

| Fibrin thrombus formation | [131] |

| Blood-brain barrier damage | [13] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).