Submitted:

21 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

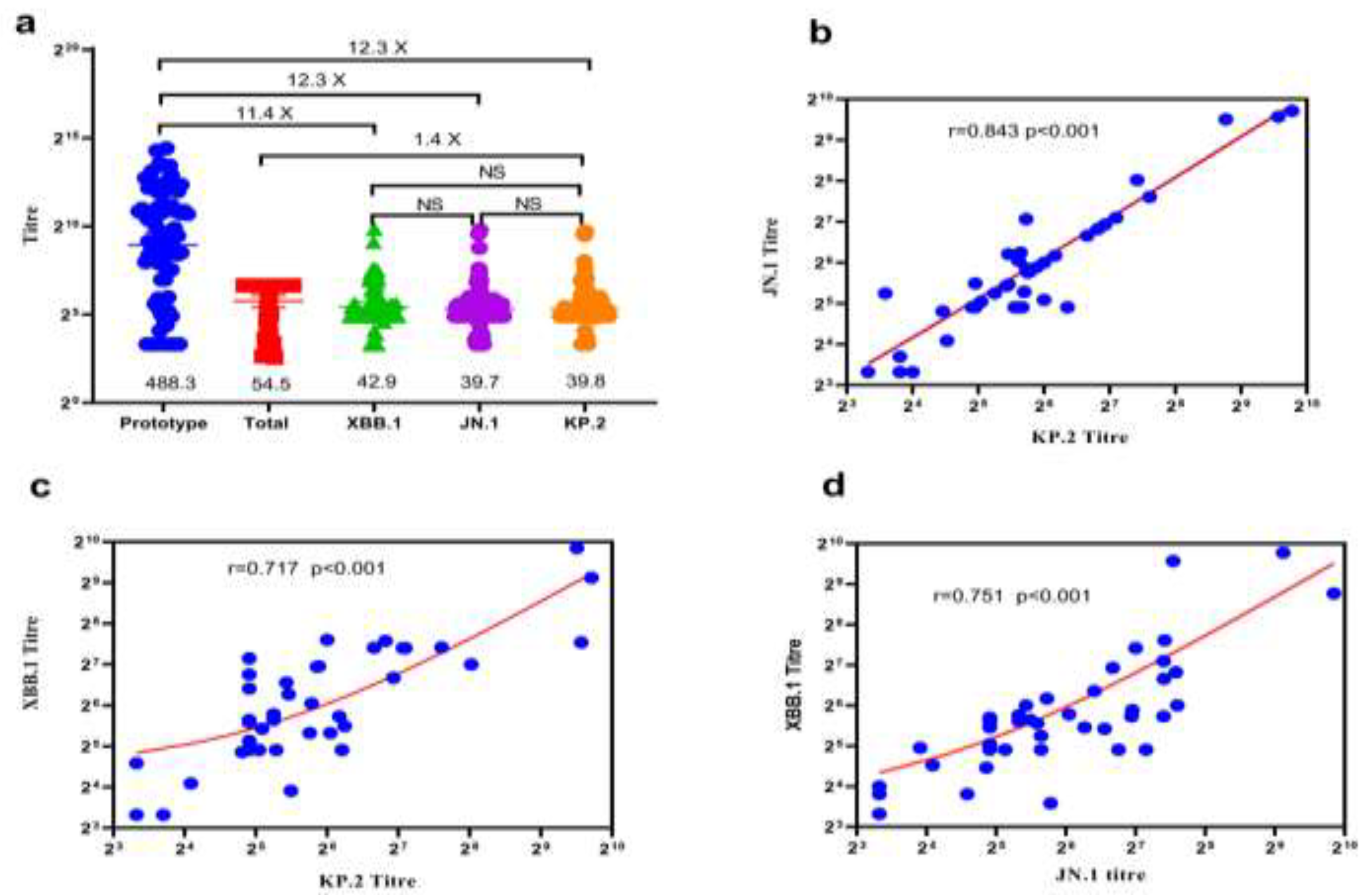

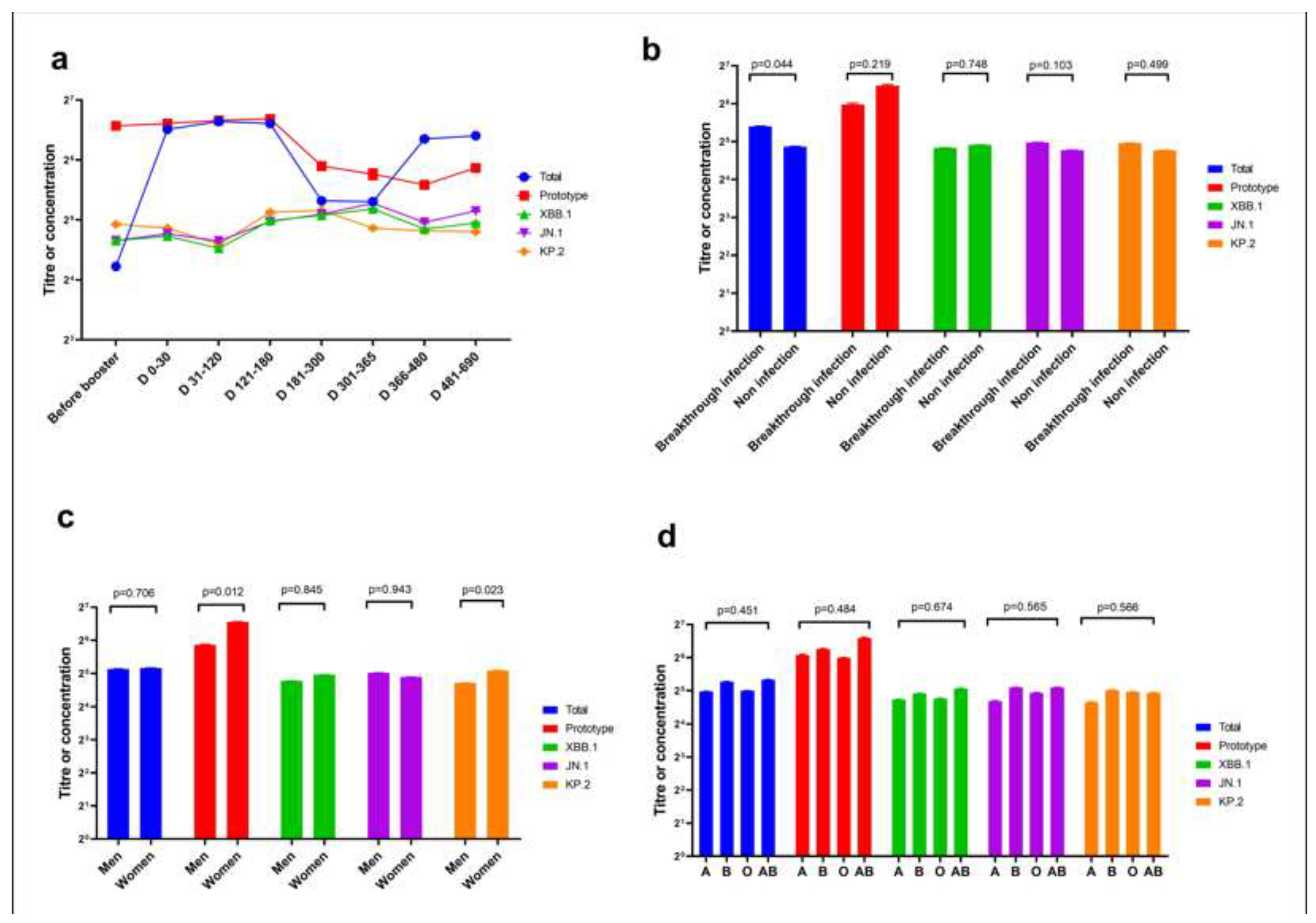

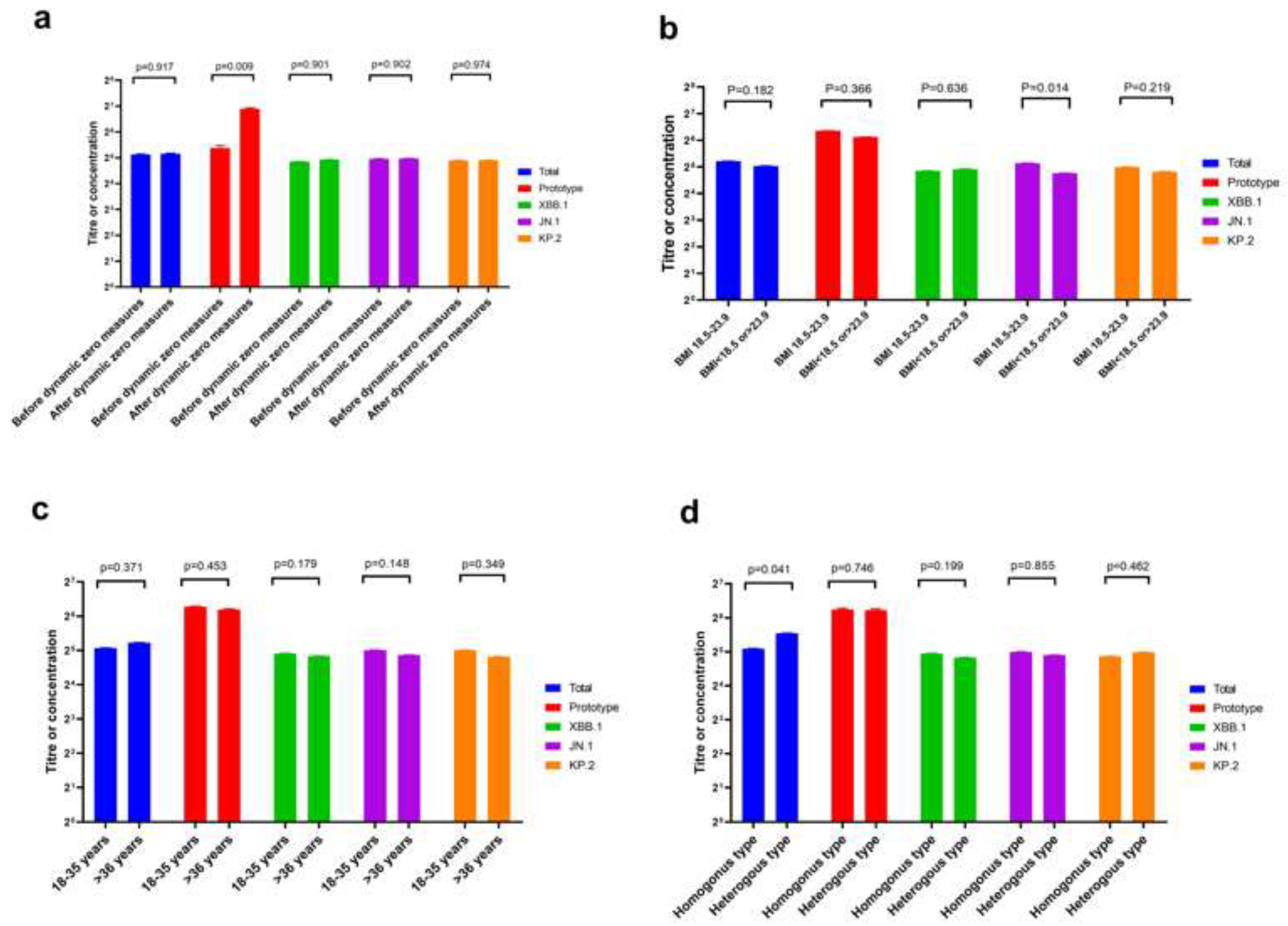

Abstract

The neutralisation ability of homologous and heterologous booster vaccinations against the KP.2 variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is unknown. We evaluated Omicron variants (XBB.1, JN.1, and KP.2) neutralisation in participants vaccinated with heterologous versus homologous boosters. In 38 participants each from homologous and heter-ologous booster groups over 690 days, serum pseudovirus neutralisation was tested against the prototype, XBB.1, JN.1, and KP.2 variants to detect neutralisation titres. Total concentration of neutralising antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain was measured by en-zyme-linked immunosorbent assay. On throat swab samples, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was used to verify breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections in participants. Geometric mean neutralising titres against the prototype, total, XBB.1, JN.1, and KP.2 variants were 488.3, 54.5, 42.9, 39.7, and 39.8, respectively. Neutralisation assays revealed 12.3-, 12.3-, and 11.4-fold reduc-tions against JN.1, KP.2, and XBB.1 variants, respectively, compared with the prototype. No sig-nificant difference occurred in neutralising antibody titres among JN.1, KP.2, and XBB.1 Omicron variants. Homologous booster group and males produced fewer neutralising antibodies than heterologous booster group and females, respectively. KP.2 Omicron variant exhibited compa-rable immune evasion properties with other variants. A second different-type or broad-spectrum booster may improve neutralisation against Omicron variants KP.2.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

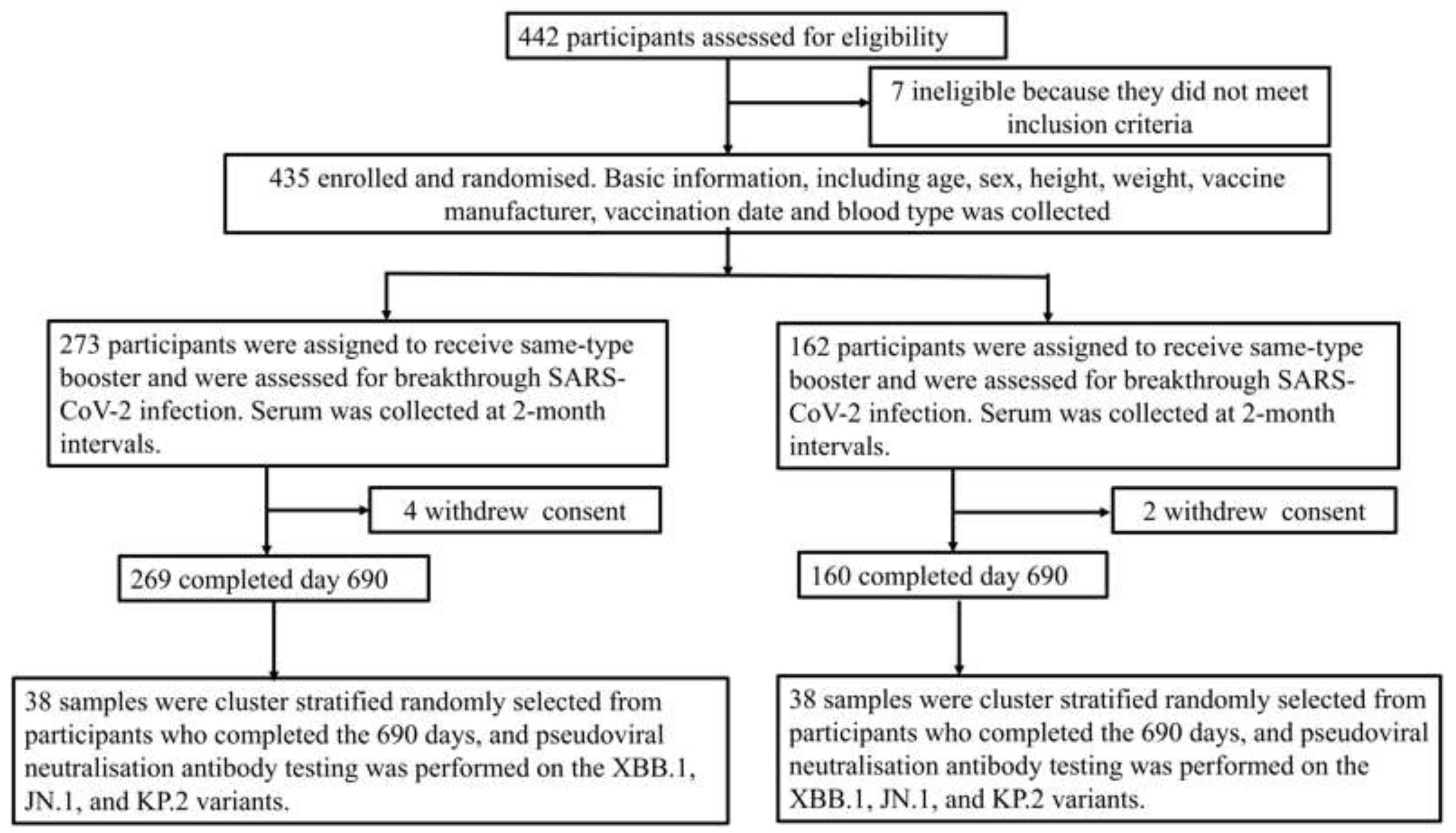

2.1. Participants and Flow of Study

2.2. Assessment of Samples

2.3. Serum Pseudovirus Neutralisation Test

2.4. Measurement of Total Neutralising Antibodies and ABO Blood Typing

2.5. Throat Swab Samples Test

2.6. Ethics

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaku, Y.; Yo, M. S.; Tolentino, J. E.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K. Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium, Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.3, LB.1, and KP.2.3 variants. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e482–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, V.; Das, R.; Pramanik, R.; Nannaware, K.; Sushma, Y.; Taji, N.; Rajput, V.; Rajkhowa, R.; Pacharne, P.; Shah, P.; Gogate, N.; Sangwar, P.; Bhalerao, A.; Jain, N.; Kamble, S.; Dastager, S.; Shashidhara, L. S.; Karyakarte, R.; Dharne, M. Early detection of KP.2 SARS-CoV-2 variant using wastewater-based genomic surveillance in Pune, Maharashtra, India. J Travel Med Advance online publication. 2024, taae097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Jayan, J.; Sharma, R. K.; Gaidhane, A. M.; Zahiruddin, Q. S.; Rustagi, S.; Satapathy, P. The emerging challenge of FLiRT variants: KP.1.1 and KP.2 in the global pandemic landscape. QJM 2024, 117, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, F.; Ciccozzi, A.; Romano, C.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. Another variant another history: description of the SARS-CoV-2 KP.2 (JN.1.11.1.2) mutations. Infect Dis (Lond). 2024, 56, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Faraone, J. N.; Hsu, C. C.; Chamblee, M.; Zheng, Y. M.; Carlin, C.; Bednash, J. S.; Horowitz, J. C.; Mallampalli, R. K.; Saif, L. J.; Oltz, E. M.; Jones, D.; Li, J.; Gumina, R. J.; Xu, K.; Liu, S. L. Neutralization escape, infectivity, and membrane fusion of JN.1-derived SARS-CoV-2 SLip, FLiRT, and KP.2 variants. Cell Rep 2024, 43, 114520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haitao, T.; Vermunt, J.V.; Abeykoon, J.; Ghamrawi, R.; Gunaratne, M.; Jayachandran, M.; Narang, K.; Parashuram, S.; Suvakov, S.; Garovic, V.D. COVID-19 and sex differences: Mechanisms and biomarkers. Mayo Clin Proc 2189, 95, 2189–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitselman, K.; Bédard-Matteau, J.; Rousseau, S.; Tabrizchi, R.; Daneshtalab, N. Sex differences in vascular endothelial function related to acute and long COVID-19. Vascul Pharmacol. 2024, 154, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlarbi, M.; Ding, S.; Bélanger, É.; Tauzin, A.; Poujol, R.; Medjahed, H.; El Ferri, O.; Bo, Y.; Bourassa, C.; Hussin, J.; Fafard, J.; Pazgier, M.; Levade, I.; Abrams, C.; Côté, M.; Finzi, A. Temperature-dependent Spike-ACE2 interaction of Omicron subvariants is associated with viral transmission. mBio. 2024, 15, e0090724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, J.; Sun, Q.; Chen, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xue, X.; Fang, J.; Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Kan, H. Respiratory benefits of multisetting air purification in children: A cluster randomized crossover trial. JAMA Pediatr 2024, e245049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Peng, Z.; Wei, F.; Jin, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J.; Ren, Z.; Lu, B.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Huang, S. Study on the COVID-19 epidemic in mainland China between November 2022 and January 2023, with prediction of its tendency. J BiosafBiosecur. 2023, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Xu, Y.; Dai, R.; Zheng, L.; Qin, P.; Wan, P.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, H.; Hu, X.; Lv, H. Study of efficacy and antibody duration to fourth-dose booster of Ad5-nCoV or inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Chinese adults: a prospective cohort study. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1244373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Li, Q.; Liang, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, S.; Cui, Q.; Nie, J.; Wu, Q.; Qu, X.; Huang, W.; Wang, Y. The significant immune escape of pseudotyped SARS-CoV-2 variant Omicron. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeworowski, L. M.; Mühlemann, B.; Walper, F.; Schmidt, M. L.; Jansen, J.; Krumbholz, A.; Simon-Lorière, E.; Jones, T. C.; Corman, V. M.; Drosten, C. Humoral immune escape by current SARS-CoV-2 variants BA.2.86 and JN.1, December 2023. Euro Surveill 2024, 29, 2300740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaku, Y.; Okumura, K.; Padilla-Blanco, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Uriu, K.; Hinay, A.A., Jr.; Chen, L.; Plianchaisuk, A.; Kobiyama, K.; Ishii, K. J. Genotype to Phenotype Japan (G2P-Japan) Consortium, Zahradnik, J.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 JN.1 variant. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planas, D.; Staropoli, I.; Michel, V.; Lemoine, F.; Donati, F.; Prot, M.; Porrot, F.; Guivel-Benhassine, F.; Jeyarajah, B.; Brisebarre, A.; Dehan, O.; Avon, L.; Bolland, W.H.; Hubert, M.; Buchrieser, J.; Vanhoucke, T.; Rosenbaum, P.; Veyer, D.; Péré, H.; Lina, B.; Schwartz, O. Distinct evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron XBB and BA.2.86/JN.1 lineages combining increased fitness and antibody evasion. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Guo, Y.; Bowen, A.; Mellis, I. A.; Valdez, R.; Gherasim, C.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D.D. XBB.1.5 monovalent mRNA vaccine booster elicits robust neutralizing antibodies against XBB subvariants and JN.1. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 315–321.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Jian, F.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, L.; Niu, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, F.; Jin, R.; Wang, Y.; Cao, Y. Fast evolution of SARS-CoV-2 BA.2.86 to JN.1 under heavy immune pressure. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024, 24, e70–e72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Xu, J.; Ma, B.; Chen, G.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Jing, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, B.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Li, Y. Characteristics of humoral and cellular responses to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) inactivated vaccine in central China: A prospective, multicenter, longitudinal study. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raisinghani, N.; Alshahrani, M.; Gupta, G.; Verkhivker, G. Atomistic prediction of structures, conformational ensembles and binding energetics for the SARS-CoV-2 spike JN.1, KP.2 and KP.3 variants using AlphaFold2 and molecular dynamics simulations: Mutational profiling and binding free energy analysis reveal epistatic hotspots of the ACE2 affinity and immune escape. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itamochi, M.; Yazawa, S.; Saga, Y.; Shimada, T.; Tamura, K.; Maenishi, E.; Isobe, J.; Sasajima, H.; Kawashiri, C.; Tani, H.; Oishi, K. COVID-19 mRNA booster vaccination induces robust antibody responses but few adverse events among SARS-CoV-2 naive nursing home residents[J]. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 23295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savulescu, C.; Prats-Uribe, A.; Brolin, K.; Lovrić Makarić, Z.; Uusküla, A.; Panagiotakopoulos, G.; Bergin, C.; Fleming, C.; Agodi, A.; Bonfanti, P.; Murri, R. Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among European healthcare workers and effectiveness of the first booster COVID-19 vaccine, VEBIS HCW observational cohort study, May 2021-May 2023[J]. Vaccines (Basel). 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talmy, T.; Nitzan, I. Rapid rollout and initial uptake of a booster COVID-19 vaccine among Israel defense forces soldiers[J]. J Prev. 2023, 44, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Favresse, J.; Gillot, C.; Cabo, J.; David, C.; Dogné, J.M.; Douxfils, J. Neutralizing antibody response to XBB.1.5, BA.2.86, FL.1.5.1, and JN.1 six months after the BNT162b2 bivalent booster[J]. Int J Infect Dis. 2024, 143, 107028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Factor | Heterologous-type (n = 38) |

Homologous-type (n = 38) |

P | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 16 | 20 | 0.358 | 36 |

| Female | 22 | 18 | 40 | |

| Age (years), M (P25, P75) * | 27.0 (21, 57.0) | 37.5 (31, 50) | 0.084 | 34.5 (24.5, 44.8) |

| 18–35 | 24 | 18 | 0.166 | 42 |

| > 36 | 14 | 20 | 34 | |

| Blood type | ||||

| A | 10 | 6 | 0.719 | 16 |

| B | 9 | 10 | 19 | |

| O | 14 | 17 | 31 | |

| AB | 5 | 5 | 10 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7 ± 3.3 | 22.9 ± 3.3 | 0.702 | 22.8 ± 3.4 |

| 18.5–23.9 | 26 | 22 | 0.342 | 48 |

| < 18.5 and > 23.9 | 12 | 16 | 28 | |

| Breakthrough infection | ||||

| Yes | 22 | 15 | 0.108 | 37 |

| No | 16 | 23 | 39 | |

| Control measures | ||||

| Dynamic zero policy (before 13 December 2022) | 7 | 23 | 0.001 | 30 |

| Routine control measures (after 13 December 2022) | 31 | 15 | 46 | |

| Duration after booster | ||||

| Before booster | 0 | 5 | 0.054 |

5 |

| 1–30 | 4 | 9 | 13 | |

| 31–120 | 8 | 4 | 12 | |

| 121–180 | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| 181-300 | 5 | 3 | 8 | |

| 301–365 | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| 366–480 | 7 | 2 | 9 | |

| 481–690 | 9 | 7 | 16 | |

| Interval between the primary and booster vaccinations | ||||

| 180–210 | 12 | 17 | 0.238 | 29 |

| > 210 | 26 | 21 | 47 | |

| Booster vaccine type | ||||

| Inactive vaccine | 0 | 35 | <0.001 | 35 |

| Attenuated live vaccine | 31 | 0 | 31 | |

| Protein vaccine | 7 | 3 | 10 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).