1. Introduction

Neonatal sepsis (NS) is described as a bloodstream infection that occurs within 28 days after birth and is caused by bacterial, viral, or fungal pathogens [

1]. NS is responsible for 15% of newborn deaths in 2016 worldwide [

2]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based research from various parts of the world estimated the incidence of 2824 newborn sepsis cases per 100,000 live births as well as death rate of 17.6% [

3]. An estimated 2.3 million newborn deaths occurred worldwide in 2022 [

4]. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5) 2019–21 reports that the neonatal mortality rate (NNMR) in Tamil Nadu is 12.7 per 1,000 live births, while the NNMR in India is 24.9 per 1,000 live births [

5].

Preterm newborns and those with extremely low birth weights are more susceptible to morbidity and death from NS [

1,

6,

7]. India had the highest burden of newborn deaths, with around 1,000,000 infants dying every year within the first four weeks of life [

8]. It is especially important to rule out fungal sepsis when a baby is severely ill, even if blood cultures are negative. This syndrome is common in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), especially when there have been invasive operations and prolonged empirical antibiotic treatment. The neonatal fatalities are caused by sepsis, highlighting the critical need for enhanced infection control and medical treatment for newborns in the country.

A study from Chennai, India concluded that careful monitoring of the coagulation profile, including Prothrombin Time (PT), activated Partial Thromboplastin Clotting Time (aPTT), and Intracranial Haemorrhage (ICH), had a substantial impact on non-survival in fungal sepsis neonates when employing Cox regression analysis. The prevalence of fungal infection in infants varies substantially between medical facilities due to differences in modifiable risk factors [

9]. Time-to-event data collected across several geographical areas is frequently divided into strata, or clusters, such as regions or healthcare facilities [

10,

11]. Frailty models employ random effects to reflect unobserved heterogeneity in survival analysis, helping to explain variability in survival times that cannot be explained by observable factors. These models are especially useful in situations comprising clustered or grouped data, such as patients from several geographical areas [

12]. Incorporating geographical information into the survival model will be helpful if survival times differ between locations. Numerous studies described the importance of geographic location information in survival prediction and spatial survival frailty models [

10,

11,

13,

14,

15,

16] investigated the patterns and geographic distribution of newborn sepsis in Uganda from 2016 to 2020 in order to direct measures aimed at lowering the prevalence of sepsis-related fatalities and neonatal sepsis [

17]. Kibret et al., 2022 explored the spatial variations and contributing factors for neonatal mortality rates in Ethiopia using Bayesian spatial logistic regression model [

18].

The use of spatial survival analysis for figuring out diagnostic delays in high-incidence locations was demonstrated in analysing Tuberculosis (TB) diagnosis delays [

19]. Numerous studies have applied Bayesian spatial survival models to a variety of disease datasets [

10,

11,

14,

15,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. To our knowledge, a spatial frailty model using a Bayesian approach to identify hotspot areas and risk factors for neonatal deaths due to fungal sepsis has not yet been studied. Compared to conventional statistical approaches, the Bayesian spatial method assist in the reduction of bias and variance more effectively [

24]. According to computer advances such as Geographic Information Systems and Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), Bayesian methods to frailty models that may explain spatial clustering are easier to implement [

11,

25]. The Bayesian spatial survival model is robust estimates when survival data is spatially correlated, complex, and when there is a need for robust estimates that incorporate prior knowledge and quantify uncertainty [

13,

23]. This was a unique opportunity to use the data on newborns with fungal sepsis in India. Against this background, our research hypothesis aims to identify factors influencing neonatal deaths due to fungal sepsis and to pinpoint hotspot areas associated with these deaths using Bayesian spatial frailty models.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

Secondary data on 80 neonates who were admitted to the NICU and diagnosed with fungal sepsis using blood culture at Government Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital in Tamil Nadu, India during January 2018 and December 2020 [

9] was considered for this study. Of 80 neonates, 50 (62.5%) were died and the remaining 30 (37.5%) were discharged. The variables such as addresses of the neonates, weeks of gestational age (GA_weeks), the neonates’s birth weight (B_Weight), Haemorrhage - no haemorrhage, intraventricular haemorrhage and intracerebral haemorrhage, platelet count (in 10^3 µL), levels of activated thromboplastin (PT_APTT) - normal and abnormal, number of hours spent in NICU (time) and outcome - alive/dead were extracted for this study.

2.2. Setting and Study design

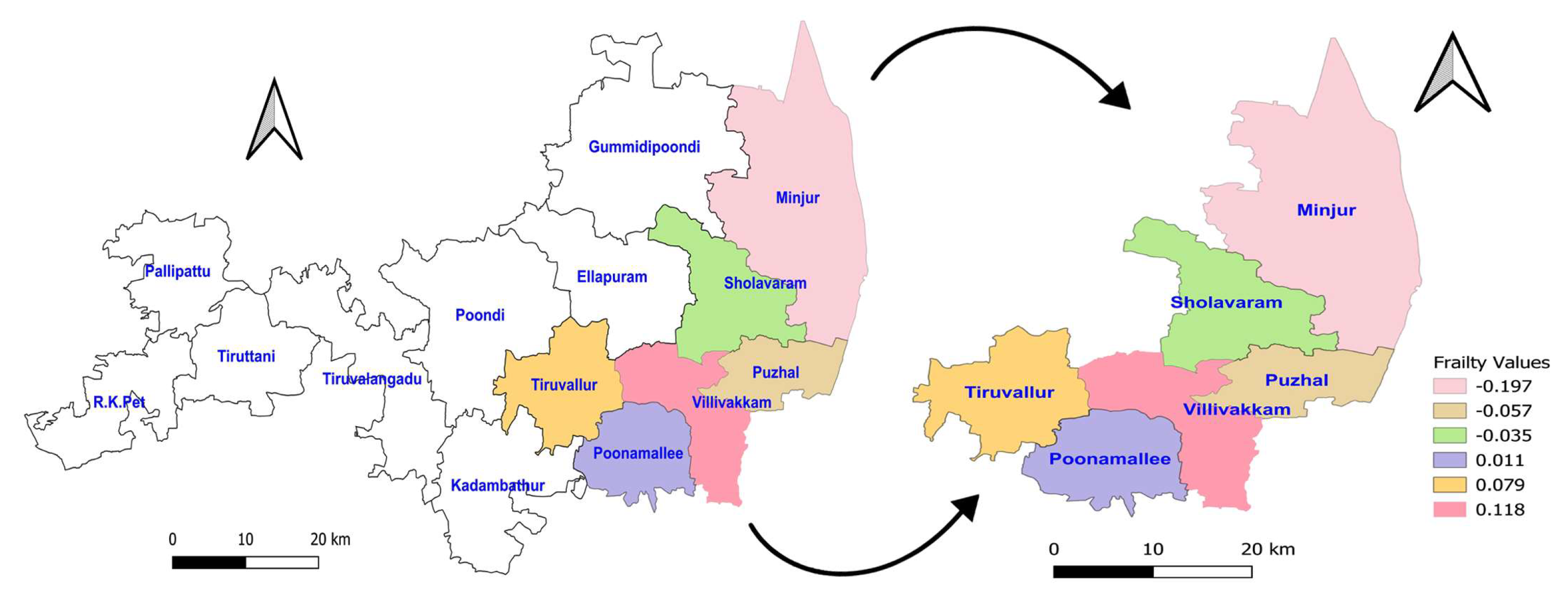

This is a Bayesian spatial survival modeling approach utilizing secondary data of NFS. Based on geographical location of residence of neonates who were admitted in the NICU, Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, their location were grouped into six blocks in Tiruvallur district which having 14 blocks. The six blocks are Tiruvallur, Poonnamalle, Villivakkam, Minjur, Puzhal, and Sholavaram.

2.3. Ethics Approval

The original study was approved by Institutional Ethical committee of Government Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital (IEC No. 02A-2017.14/11/2017). The written assent was obtained from the parents of the neonates. The details of the study design were found in the study elsewhere [

9].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The proportional hazard (PH) frailty model was applied to the data on neonates with fungal sepsis. The event of interest was defined as death of neonates with fungal sepsis who admitted in NICU of the hospital. In this analysis, right censoring was used and the time was defined as the difference between the day of admission in the NICU and the day of the event of interest occurred or the day of discharge. The frailty model incorporates a random effect to capture unobserved factors that influence the hazard, allowing for individual or group-level variability [

26]. We applied the parametric frailty models including Log-logistic PH [

27,

28,

29], Log-normal PH [

27,

30,

31] and Weibull PH [

27,

31,

32,

33] models to fit the data by incorporating the MCMC iteration and compared the results [

34]. In a Bayesian framework, estimating model parameters is the primary objective of MCMC methods such as Metropolis-Hastings [

35] and Gibbs sampling [

36] algorithms to generate samples from the appropriate marginal posterior distributions. A paramete

r’s space is explored by the MCMC sampler based on its prior knowledge and the likelihood of the observed values [

37]. Plotting the values in the simulated chains against the iteration, or the MCMC trace plot, is another diagnostic tool to check for the model convergence. A high degree of chain mixing suggests that the MCMC is convergent. In this study, non-informative prior was used for Bayesian analysis [

38]. The fitted survival curve was employed to obtain a better insight of the geographic pattern [

39,

40]. The Cox-Snell residual plots [

15,

40,

41] were utilised to assess the model

s’ fitness and to compare the fitted models. It was assumed that each region had at least one neighbour hence the proportionality constant for the improper density, which represents the non-spatial data, was considered under an independent Gaussian prior [

14,

40]. We used three measures Log pseudo marginal likelihood (LPML), the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) and Watanabe Akaike Information Criterion (WAIC) [

15,

38] for comparing the best fit model by choosing the model with lowest LPML, DIC and WAIC of Bayesian spatial PH frailty model. The

R version 4.1.3 software was used to carry out the statistical analysis. The prior for the regression coefficient of PH model follow Normal distribution with mean ‘0’ and large variance ‘1000’. The prior for the frailty term or random effect follows Gaussian distribution with mean ‘0’ and default variance used in the R software. The spatial prior is an independent and identically distributed random effect that follows a normal distribution with mean ‘0’ and standard deviation ‘σ’. It accounts for heterogeneity after adjusting for subject-specific covariates and includes a random effect within each group [

15,

38]. The spatial map was done using Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) version 3.26 software.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Details for NFS Data

The descriptive analysis of associated parameters such as Gestational age in weeks, neonate’s birth weight in kilo gram (kg) and platelet count in micro litre (10

3 /μL) with respect to survival and death of the neonates. The mean weight of childbirth was 2.08 kg. The Platelets count of the neonates ranges from 2 to 252. The average of haemorrhage and PT_APTT for neonates who died were 0.86, 0.96 respectively which were higher than those for neonates who survived. In contrast, the average of platelet count for neonates who died was 47 (10

3 /μL) which was lower as compared to the platelet count of neonates who survived (56.4 (10

3 /μL)) were presented in the

Table 1.

3.2. Posterior Estimates of Spatial Frailty of Three PH Models

The Bayesian spatial frailty of the three PH models were obtained using 1000 iterations after discarding first 1000 burin in iteration. The posterior estimates of the three PH models, the spatial frailty hazard ratios and their 95% credible intervals (CI), are presented in

Table 2. NFS with abnormal PT_APTT levels had a substantially higher risk of death compared to those with normal PT_APTT levels for the three models (Log-logistic PH model: HR = 22.12, 95% CI: 5.40–208.08; Log-normal PH model: HR = 20.87, 95% CI: 5.29–123.23; Weibull PH model: HR = 18.49, 95% CI: 5.60–93.41). Over all, the risk of death was more than 18 times higher in those with abnormal PT_APTT. NFS neonates with haemorrhage had an increased risk of death compared to those without haemorrhage for the models (Log-normal PH model: HR = 1.65, 95% CI: 1.05–2.75; Weibull PH model: HR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.07–3.12) except for the model Log-logistic PH model. Over all, the risk of death was approximately 1.75 times higher in neonates with haemorrhage. Abnormal PT_APTT is a much stronger predictor of mortality (HR > 20) than haemorrhage (HR ~1.65–1.75).

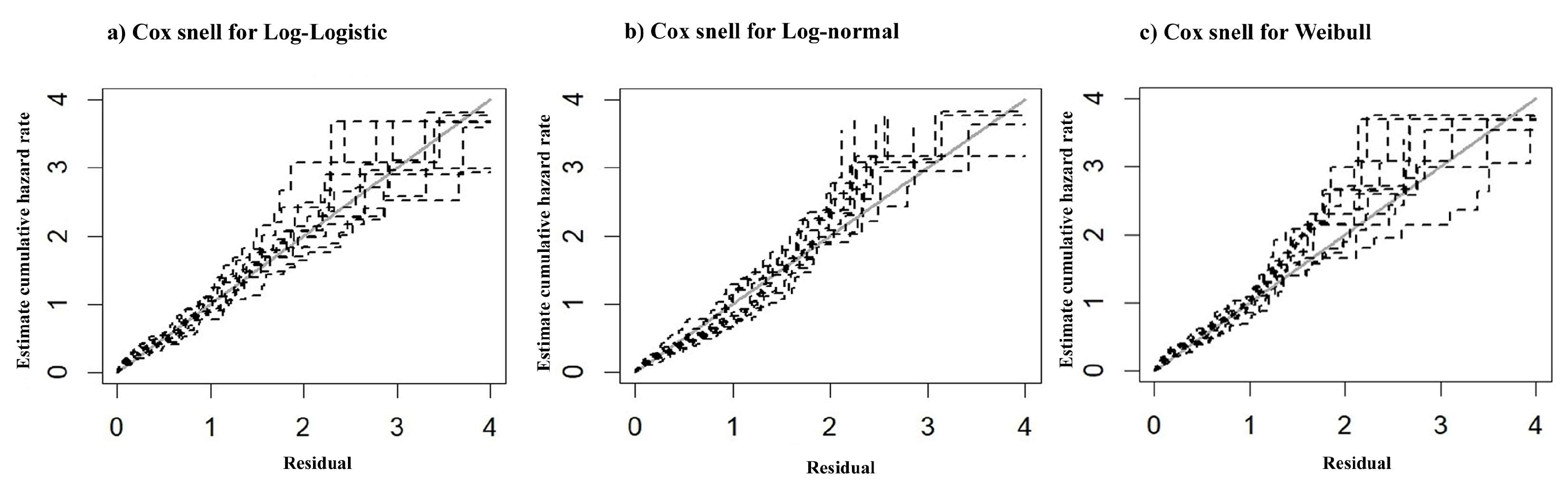

The acceptance rate of Adaptive Metropolis Hasting Algorithm for the three PH models such as Log-logistic, Log-normal and Weibull models were 0.17, 0.20 and 0.19 respectively and which were around 0.2 considered as practical acceptance rate for the sampling process. The result of fit indices LPML, DIC and WAIC are presented in

Table 2. The Weibull PH model was found to be good (LPML = 220.68, DIC = 439.64 and WAIC = 440.76) when comparing the fit indices of the other two models have been reported in

Table 3. The

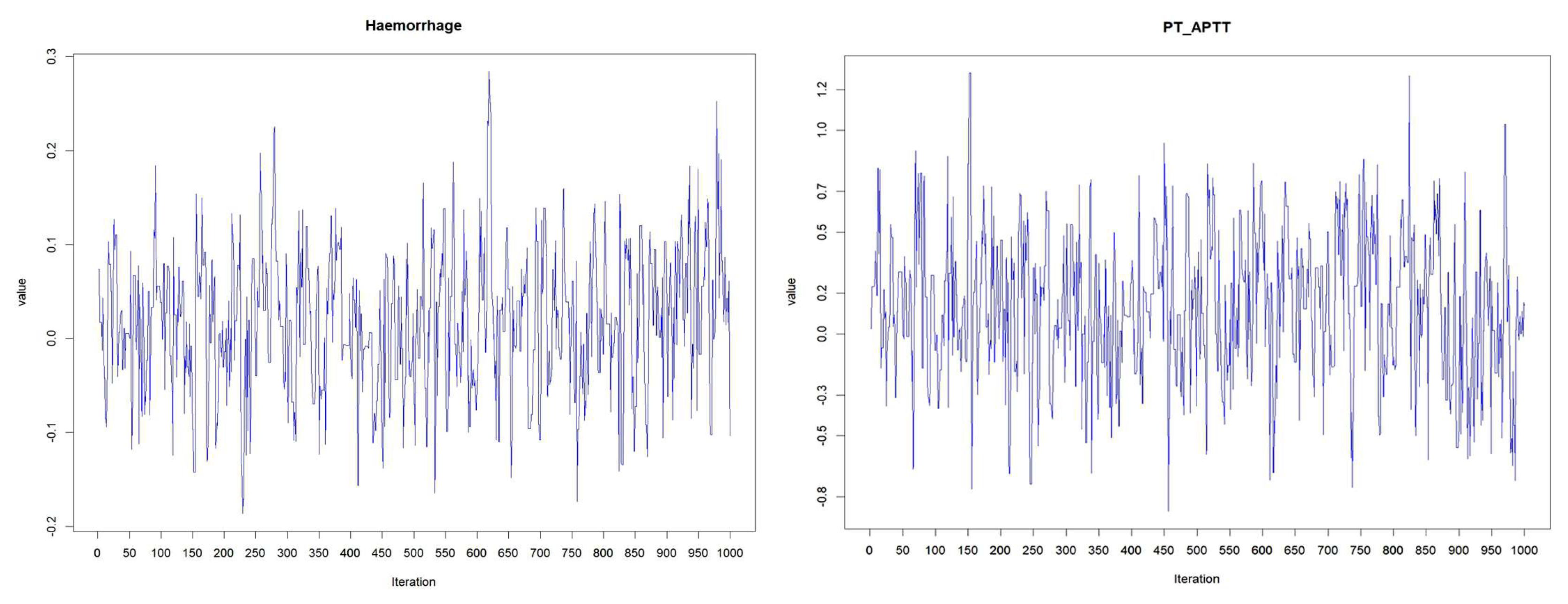

Figure 1 represents the average of values of posterior sampling frailties. The higher rates of mortality for NFS occurred in the hotspot regions Villivakkam (0.118), Tiruvallur (0.079), and Ponnamallee (0.011) among the six blocks of the study area. The spatial frailty model effectively explains the differences in infant mortality from fungal sepsis among the blocks. The Weibull PH spatial frailty model’s trace plot of the parameters shows a narrow horizontal band that indicates the parameters are converged in

Figure 2.

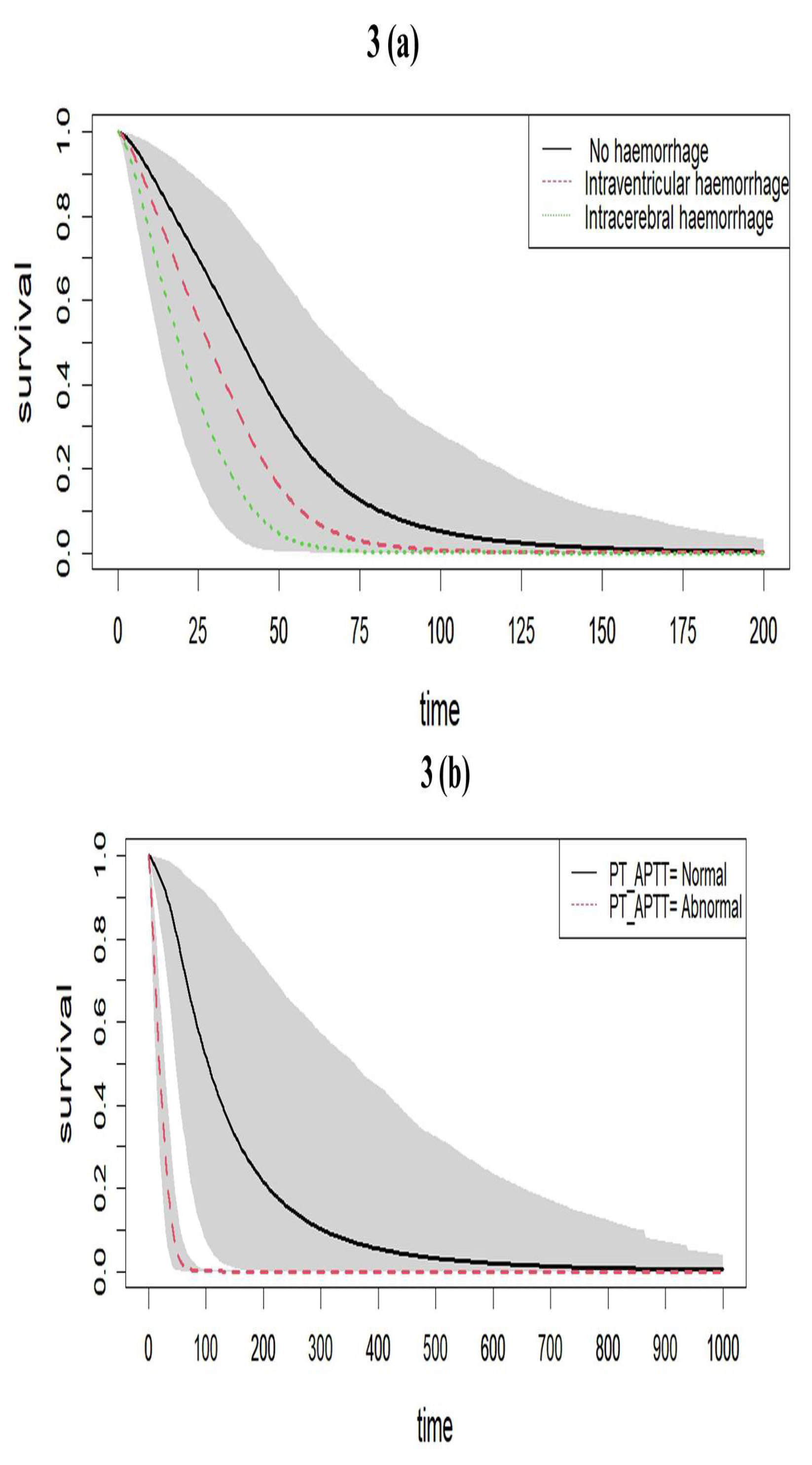

The fitted survival curves with 95% CIs are depicted for a GA_weeks of 30 weeks, B_Weight of 1 kg, a platelet count of 25 (10³ /μL), and abnormal PT_APTT levels across different types of haemorrhage. The plot indicates that survival probability is higher at earlier time points but decreases as time progresses. Additionally, it demonstrates that survival probability is lower for intracerebral haemorrhage compared to other types of haemorrhage visualized in

Figure 3a. Another set of fitted survival curves with 95% CI is shown for a GA_weeks of 30 weeks, B_Weight of 1 kg, a platelet count of 25 (10³ /μL), and intracerebral haemorrhage at varying PT_APTT levels. The figure reveals that survival probability is initially higher but declines over time. It also shows that when PT_APTT is abnormal, survival probability approaches zero after 60 hours. In contrast, when PT_APTT is normal, survival probability remains significantly higher compared to when PT_APTT is abnormal has represented in

Figure 3b. The Cox-Snell residual plots for three PH model which were used to assess the reliability of the model showed nearly straight hazard plots with a slope of one, suggesting a good model fit visualized in

Figure 4.

4. Discussion

The research article demonstrated Bayesian spatial frailty modeling technique based on the geographic locations of neonates admitted to the NICU in Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. To our knowledge, there is no previous research studies on Bayesian spatial frailty models in the survival of newborns with fungal sepsis. This study used a novel approach to modeling the spatial dependence of survival times in NFS from the six blocks in Tiruvallur district who were admitted in in Kilpauk Medical College. We assessed the posterior estimates of parameters of the three frailty PH models, Log-logistic, Log-normal, and Weibull and validated these models using fit indices for model selection. We also identified clinical factors impacting geographical disparities in neonatal mortality. Even though all the models performed well, the Weibull PH model was found as the best model, representing spatial frailty and mortality patterns in NFS. Our key findings revealed spatial heterogeneity, which has a major impact on the severity and mortality of NFS whereas the contributing factors were hemorrhage and abnormal PT_APTT levels. However, the study highlights how crucial geographic closeness is to understanding mortality and the spatial dependence of infant survival. From the current study, the hotspot blocks Villivakkam, Ponnamallee, and Tiruvallur in Tiruvallur district, showed elevated neonatal mortality rates.

A similar finding of better performance of Weibull model was documented from a study on Bayesian spatial survival models for dengue hospitalization at Wahidin Hospital in Makassar, Indonesia [

10]. The results of the current study align with prior studies that revealed the advantages of spatial survival models in various contexts, including, dengue patient survival, under-five mortality risks and COVID-19 recovery times [

14,

42,

43]. In another study on paediatric leukaemia from Southern Iran reported that the Log-normal and Weibull models were superior models compared to the Cox regression model [

44]. A study from Mexico on spatial survival model for COVID-19 highlighted that the spatial models outperformed than the Cox model in capturing variations in survival across the Mexican states. Regional clusters showed distinct mortality risks, demonstrating the necessity of geographical locations analysis for accurate risk assessment and resource allocation [

15]. Additionally, in different research study using a Bayesian spatial model concluded that the prevalence of TB/HIV co-infection varied spatially [

45].

In this study, neonates from the six blocks of the Tiruvallur district, Tamil Nadu who were admitted under the NICU at Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital accounted for 62.5% of the fatalities. Neonatal mortality among preterm newborns in NICUs of Pakistan was twice as high as in Indian NICUs, in accordance to a prospective study carried out in NICUs at three hospitals in Davangere, India, and a public hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. This occurred due to NICUs of Pakistan had fewer diagnostic tests, shorter NICU stays, and fewer resources [

46]. In a comprehensive study and meta-analysis on neonatal sepsis based on 14 countries reported an overall incidence of 2824 sepsis cases per 100,000 live births with a 17.6% mortality rate, predominantly affecting preterm and extremely low birth weight neonates. The prevalence was highest in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, with early-onset sepsis (EOS) showing higher incidence and mortality rates than late-onset sepsis (LOS) [

3].

Reducing preterm birth rates and improving newborn outcomes may be possible with targeted healthcare measures, such as supporting pregnant women and closely monitoring high-risk pregnancies. NFS is strongly linked to preterm birth, and infant death rates may be considerably reduced by recognizing and controlling risk factors, such as abnormal blood parameters like PT_APTT and hemorrhage. Postnatal interventions are also crucial in mitigating the risk of neonatal death. The observed geographical dependency in survival outcomes highlights the importance of considering a neonate’s birthplace when developing targeted interventions to address neonatal mortality effectively. Spatial survival models can aid obstetricians and healthcare providers in identifying high-risk blocks within the district that require additional resources and focused management strategies, thereby reducing preterm births, lowering infant mortality, and preventing complications associated with fungal sepsis.

There are limitations on this study, though. The absence of important clinical factors, such as the methods of delivery and the haematological and biochemical characteristics of pregnant women, may have limited the model’s accuracy. Furthermore, there may be bias in misclassification due to the dependence on self-reported data for comorbidities. Sociodemographic factors like maternal age, education, income, pregnancy intervals, and access to essential services were also absent, further constraining the analysis. Maternal infections in healthcare settings remain a critical contributor to neonatal mortality and morbidity [

47]. There may be over 80 NFS in these zones, and there is possibility of admission to nearby or other hospitals, which presents a limitation for this study.

Future research aims to address these limitations by incorporating socioeconomic indicators, levels of urbanization, poverty data, climatic factors, and additional clinical parameters. It will also take into account data associated with socioeconomic factors at the local level, including social development, urbanization, poverty, and clinical and laboratory outcomes. Expanding the study to include data from other districts and states will provide a broader understanding of NFS survival determinants. To enhance the understanding of survival determinants and improve strategies for comprehensively evaluating and treating fungal sepsis in neonates data from the other hospitals of Tamil Nadu State, India should be studied.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we assessed the survival times associated with NFS across six blocks in Tiruvallur district, Tamil Nadu, India, taking into account the geographic distribution of NFS. Intracerebral hemorrhage and abnormal PT-APTT had a substantial influence on NFS survival. The importance of spatial determinants in NFS outcomes was further highlighted by the substantial variations in survival times by geographic location.

Our results showed that all three models fit the data well, although the Weibull model performed slightly better. The risk of mortality of NFS was higher in those with abnormal PT_APTT and with haemorrhage.

These results highlight how important it is for newborns with these risk factors to be identified early and closely monitored in NICUs. When NFS patients have abnormal PT_APTT and haemorrhage prompt intervention combined with focused care strategies may significantly increase survival rates. To reduce mortality in NFS, future initiatives must incorporate these findings into NICU procedures, with an increased focus on risk stratification, early diagnostic screening, and evidence-based interventions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The original study was approved by Institutional Ethical committee of Government Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital (IEC No. 02A-2017.14/11/2017). The written assent was obtained from the parents of the neonates. The details of the study design were found in the study elsewhere [

9].

Informed Consent Statement

As per the study approved by the IEC Committee [

9].

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon receiving written request and approval granted by the study authority.

Acknowledgments

The original study main author acknowledges the authorities of the Government Kilpauk Medical College and Hospital and ICMR-National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, Indian Council of Medical Research, Chennai, India for permitting us to use the data for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NFS |

Neonatal Fungal Sepsis |

| NS |

Neonatal Sepsis |

| PH |

Proportional Hazard |

| NFHS-5 |

National Family Health Survey - 5 |

| NNMR |

Neonatal Mortality Rate |

| NICU |

Neonatal Intensive Care Units |

| PT |

Prothrombin Time |

| aPTT |

activated Partial Thromboplastin Clotting Time |

| PT_APTT |

Levels of Activated Thromboplastin Level |

| ICH |

Intracranial Haemorrhage |

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| MCMC |

Markov chain Monte Carlo |

| GA_weeks |

Gestational Age in Weeks |

| B_Weight |

Neonates Birth Weight |

| LPML |

Log Pseudo Marginal Likelihood |

| DIC |

Deviance Information Criterion |

| WAIC |

Watanabe Akaike Information Criterion |

| QGIS |

Quantum Geographic Information System |

| CI |

Credible Intervals |

| HR |

Hazard Ratio |

References

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.; Fanaroff, A.A.; Wright, L.L.; Carlo, W.A.; Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Lemons, J.A.; Donovan, E.F.; Stark, A.R.; Tyson, J.E.; Oh. , W.; Bauer, C.R.; Korones, S.B.; Shankaran, S.; Laptook, A.R.; Stevenson, D.K.; Papile, L.-A.; Poole, W.K. Late-Onset Sepsis in Very Low Birth Weight Neonates: The Experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2002, 110, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO sepsis technical expert meeting, 16-. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-sepsis-technical-expert-meeting-16-17-january-2018 (accessed 2025-01-09). 17 January.

- Fleischmann, C.; Reichert, F.; Cassini, A.; Horner, R.; Harder, T.; Markwart, R.; Tröndle, M.; Savova, Y.; Kissoon, N.; Schlattmann, P.; Reinhart, K.; Allegranzi, B.; Eckmanns, T. Global Incidence and Mortality of Neonatal Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arch Dis Child 2021, 106, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newborn mortality. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborn-mortality (accessed 2025-01-10.

- NFHS. International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 20019-21 https://mohfw.gov.in/sites/default/files/NFHS-5_Phase-II_0.pdf (accessed 2025-01-10).

- Adams-Chapman, I.; Stoll, B.J. Neonatal Infection and Long-Term Neurodevelopmental Outcome in the Preterm Infant. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases 2006, 19, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, B.J.; Hansen, N.I.; Adams-Chapman, I.; Fanaroff, A.A.; Hintz, S.R.; Vohr, B.; Higgins, R.D.; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Neurodevelopmental and Growth Impairment among Extremely Low-Birth-Weight Infants with Neonatal Infection. JAMA 2004, 292, 2357–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Neonatal-Perinatal Database 2002 - NNPD Nodal Center AIIMS Delhi New Delhi; 2005. Available at: https://www.newbornwhocc.org/pdf/nnpd_report_2002-03.PDF Accessed 10 August 2019.

- Adalarasan, N.; Stalin, S.; Venkatasamy, S.; Sridevi, S.; Padmanaban, S.; Chinnaiyan, P. Association and Outcome of Intracranial Haemorrhage in Newborn with Fungal Sepsis- A Prospective Cohort Study. IJNMR 2022. [CrossRef]

- Aswi, A.; Cramb, S.; Duncan, E.; Hu, W.; White, G.; Mengersen, K. Bayesian Spatial Survival Models for Hospitalisation of Dengue: A Case Study of Wahidin Hospital in Makassar, Indonesia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Wall, M.M.; Carlin, B.P. Frailty Modeling for Spatially Correlated Survival Data, with Application to Infant Mortality in Minnesota. Biostatistics 2003, 4, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balan, T.A.; Putter, H. A Tutorial on Frailty Models. Stat Methods Med Res 2020, 29, 3424–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motarjem, K.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Abyar, A. Geostatistical Survival Model with Gaussian Random Effect. Stat Papers 2020, 61, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thamrin, S.A. ; Aswi; Ansariadi; Jaya, A.K.; Mengersen, K. Bayesian Spatial Survival Modelling for Dengue Fever in Makassar, Indonesia. Gac Sanit, 1. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castro, E.; Guzmán-Martínez, M.; Godínez-Jaimes, F.; Reyes-Carreto, R.; Vargas-de-León, C.; Aguirre-Salado, A.I. Spatial Survival Model for COVID-19 in México. Healthcare 2024, 12, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egbon, O.A.; Bogoni, M.A.; Babalola, B.T.; Louzada, F. Under Age Five Children Survival Times in Nigeria: A Bayesian Spatial Modeling Approach. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migamba, S.M.; Kisaakye, E.; Komakech, A.; Nakanwagi, M.; Nakamya, P.; Mutumba, R.; Migadde, D.; Kwesiga, B.; Bulage, L.; Kadobera, D.; Ario, A.R. Trends and Spatial Distribution of Neonatal Sepsis, Uganda, 2016-2020. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kibret, G.D.; Demant, D.; Hayen, A. Bayesian Spatial Analysis of Factors Influencing Neonatal Mortality and Its Geographic Variation in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0270879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.; Taylor, B.M. Modelling the Time to Detection of Urban Tuberculosis in Two Big Cities in Portugal: A Spatial Survival Analysis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2016, 20, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazar, E.; Baghishani, H.; Doosti, H.; Ghavami, V.; Aryan, E.; Nasehi, M.; Sharafi, S.; Esmaily, H.; Yazdani Charati, J. Bayesian Spatial Survival Analysis of Duration to Cure among New Smear-Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis (PTB) Patients in Iran, during 2011–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, P.-F.; Sie, F.-C.; Yang, C.-T.; Mau, Y.-L.; Kuo, S.; Ou, H.-T. Association of Ambient Air Pollution with Cardiovascular Disease Risks in People with Type 2 Diabetes: A Bayesian Spatial Survival Analysis. Environ Health 2020, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, R.; Shimakura, S.; Gorst, D. Modeling Spatial Variation in Leukemia Survival Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2002, 97, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan., R.; Ponnuraja., C.; Pradeep., AM.; Moeng., SR.; Sivasamy., R.; Venkatesan, P. Srinivasan. R.; Ponnuraja. C.; Pradeep. AM.; Moeng. SR.; Sivasamy. R.; Venkatesan, P. Bayesian Spatial Cox Proportional Hazard Model For HIV Infected Tuberculosis Cases In Chennai. Global Journal of Pure and Applied Mathematics. ISSN, /: Volume 15, Number 6, pp. 971-980. https, 2019; 15. [Google Scholar]

- Besag, J.; Green, P.J. Spatial Statistics and Bayesian Computation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1993, 55, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Carlin, B.P.; Gelfand, A.E.; Banerjee, S. Hierarchical Modeling and Analysis for Spatial Data; Chapman and Hall/CRC: New York, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kau, J.B.; Keenan, D.C.; Li, X. An Analysis of Mortgage Termination Risks: A Shared Frailty Approach with MSA-Level Random Effects. J Real Estate Finan Econ 2011, 42, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, P.; Parmar, M.K.B. Flexible Parametric Proportional-Hazards and Proportional-Odds Models for Censored Survival Data, with Application to Prognostic Modelling and Estimation of Treatment Effects. Stat Med 2002, 21, 2175–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aziz, S.N.; Hassan Muse, A.; Jawa, T.M.; Sayed-Ahmed, N.; Aldallal, R.; Yusuf, M. Bayesian Inference in a Generalized Log-Logistic Proportional Hazards Model for the Analysis of Competing Risk Data: An Application to Stem-Cell Transplanted Patients Data. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2022, 61, 13035–13050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Khosa, S.K. Generalized Log-Logistic Proportional Hazard Model with Applications in Survival Analysis. J Stat Distrib App 2016, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhoseingholi, M.A.; Moghimi-Dehkordi, B.; Safaee, A.; Hajizadeh, E.; Solhpour, A.; Zali, M.R. Prognostic Factors in Gastric Cancer Using Log-Normal Censored Regression Model. Indian J Med Res 2009, 129, 262–267. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A. Exponentiated Weibull Regression for Time-to-Event Data. Lifetime Data Anal 2018, 24, 328–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Parametric Regression Model for Survival Data: Weibull Regression Model as an Example. Ann Transl Med 2016, 4, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, S.K.; Dey, D.K.; Aslanidou, H.; Sinha, D. A Weibull Regression Model with Gamma Frailties for Multivariate Survival Data. Lifetime Data Anal 1997, 3, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, C.P.; Elvira, V.; Tawn, N.; Wu, C. Accelerating MCMC Algorithms. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Comput Stat 2018, 10, e1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, W.K. Monte Carlo Sampling Methods Using Markov Chains and Their Applications. Biometrika 1970, 57, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geman, S.; Geman, D. Stochastic Relaxation, Gibbs Distributions and the Bayesian Restoration of Images*. Journal of Applied Statistics 1993, 20, 25–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.; Charvin, K.; Nielsen, S.; Sambridge, M.; Stephenson, J. Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampling Methods to Determine Optimal Models, Model Resolution and Model Choice for Earth Science Problems. Marine and Petroleum Geology 2009, 26, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musa, G.K.; Chaku, S.E.; Nwaze, N.O.; Adehi, M.U.; Omaku, P.E. Bayesian Accelerated Failure Time Model With Spatial Dependency: Application To Under Five Mortality Rate. Global Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 2024, 30, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Lawson, A.B. A Bayesian Normal Mixture Accelerated Failure Time Spatial Model and Its Application to Prostate Cancer. Stat Methods Med Res 2016, 25, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Hanson, T. A Unified Framework for Fitting Bayesian Semiparametric Models to Arbitrarily Censored Survival Data, Including Spatially Referenced Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2018, 113, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardhiah, K.; Wan-Arfah, N.; Naing, N.N.; Hassan, M.R.A.; Chan, H.-K. Comparison of Cox Proportional Hazards Model, Cox Proportional Hazards with Time-Varying Coefficients Model, and Lognormal Accelerated Failure Time Model: Application in Time to Event Analysis of Melioidosis Patients. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine 2022, 15, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, K.; Onyango, N.O.; Sarguta, R.J. A Spatial Survival Model for Risk Factors of Under-Five Child Mortality in Kenya. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanta, K.K.; Hazarika, J.; Barman, M.P.; Rahman, T. An Application of Spatial Frailty Models to Recovery Times of COVID-19 Patients in India under Bayesian Approach. JSR 2021, 65, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshnizi, S.H.; Ayatollahi, S.M.T. Comparison of Cox Regression and Parametric Models: Application for Assessment of Survival of Pediatric Cases of Acute Leukemia in Southern Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017, 18, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemechu, L.L.; Debusho, L.K. Bayesian Spatial Modelling of Tuberculosis-HIV Co-Infection in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0283334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Tikmani, S.S.; Goudar, S.S.; Hwang, K.; Dhaded, S.; Guruprasad, G.; Nadig, N.G.; Kusagur, V.B.; Patil, L.G.C.; Siddartha, E.S.; Yogeshkumar, S.; Somannavar, M.S.; Roujani, S.; Khan, M.; Shaikh, M.; Hanif, M.; Bann, C.M.; McClure, E.M.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Group, the P. S. Neonatal Mortality among Preterm Infants Admitted to Neonatal Intensive Care Units in India and Pakistan: A Prospective Study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2023, 130, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihatov Stefanovic, I. Neonatal Sepsis. Biochemia medica 2011, 21, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).