Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Urban Development

2.2. Community Engagement in Sustainable Urban Development

2.2.1. Importance of Community Engagement and Community Attachment Theory and Sense of Ownership

2.2.2. Frameworks for Understanding Community Values and Empowering Community Values.

Enhancing Participation

Capacity Building

Co-Designing Activities

Policy Integration

Inclusive Governance Models

2.3. Case Studies for Community Engagement Tool

2.3.1. Case Study 1:

2.3.2. Case Study 2:

2.3.3. Case Study 3:

2.3.4. Case Study 4 :

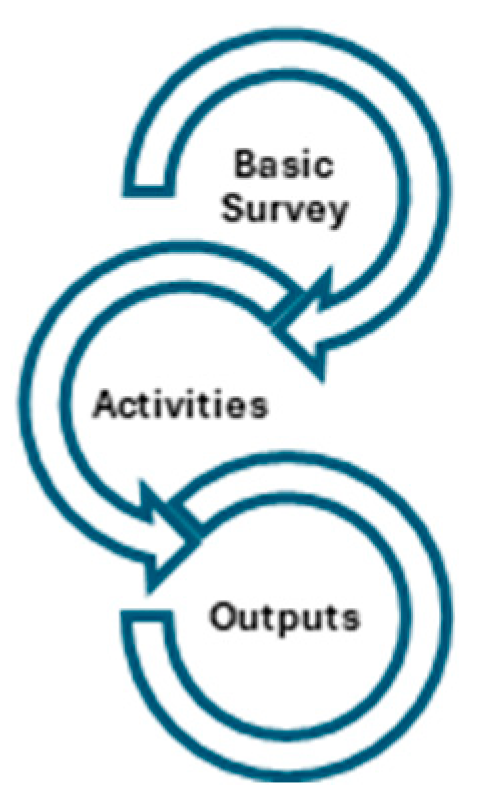

3. Methodology

3.1. GHA KHAN Project (The Aga Khan Trust for Culture)

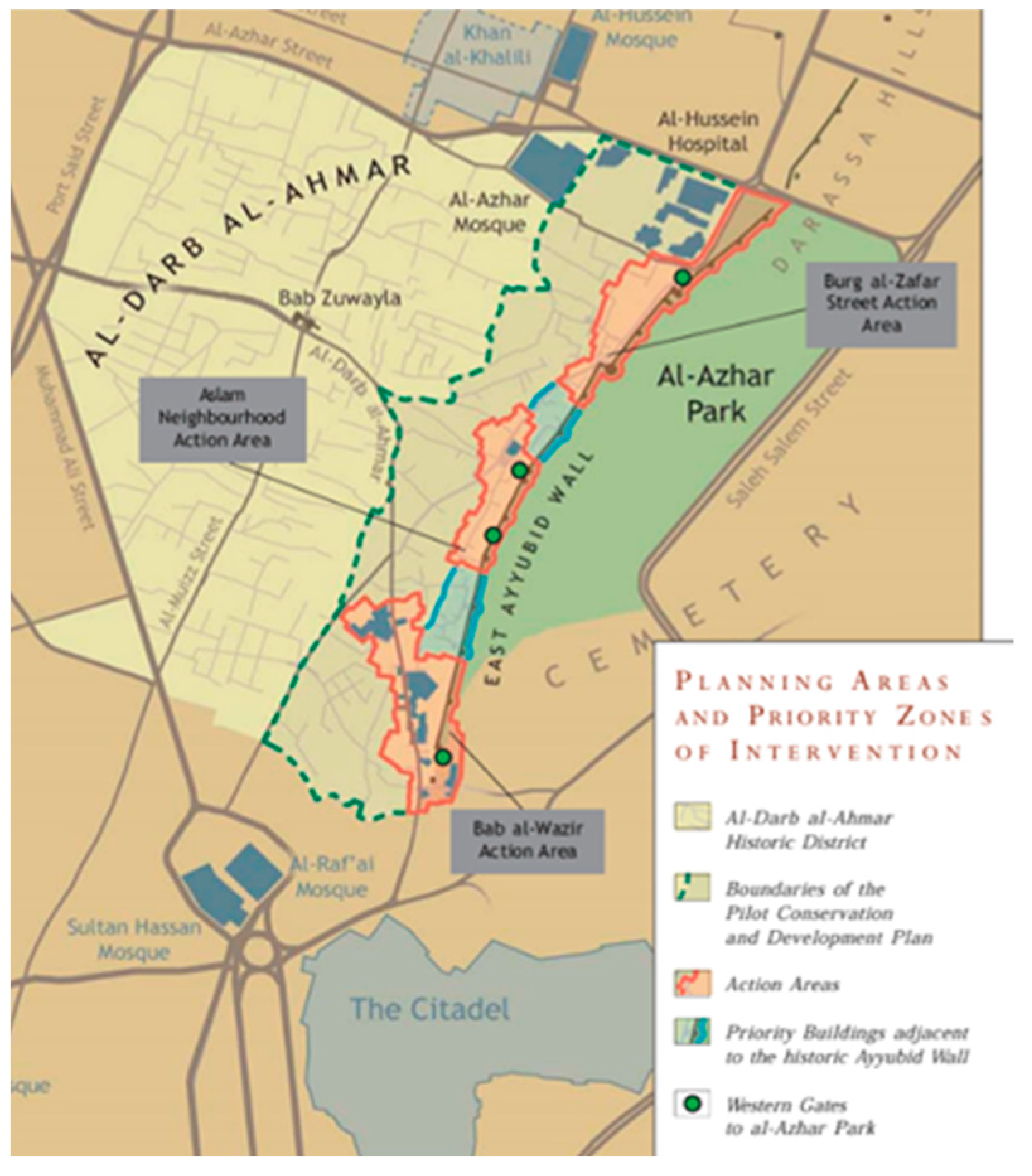

3.1.1. Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Housing Rehabilitation Program ,Cairo , Egypt (ADAA HRP) March 2004-2009

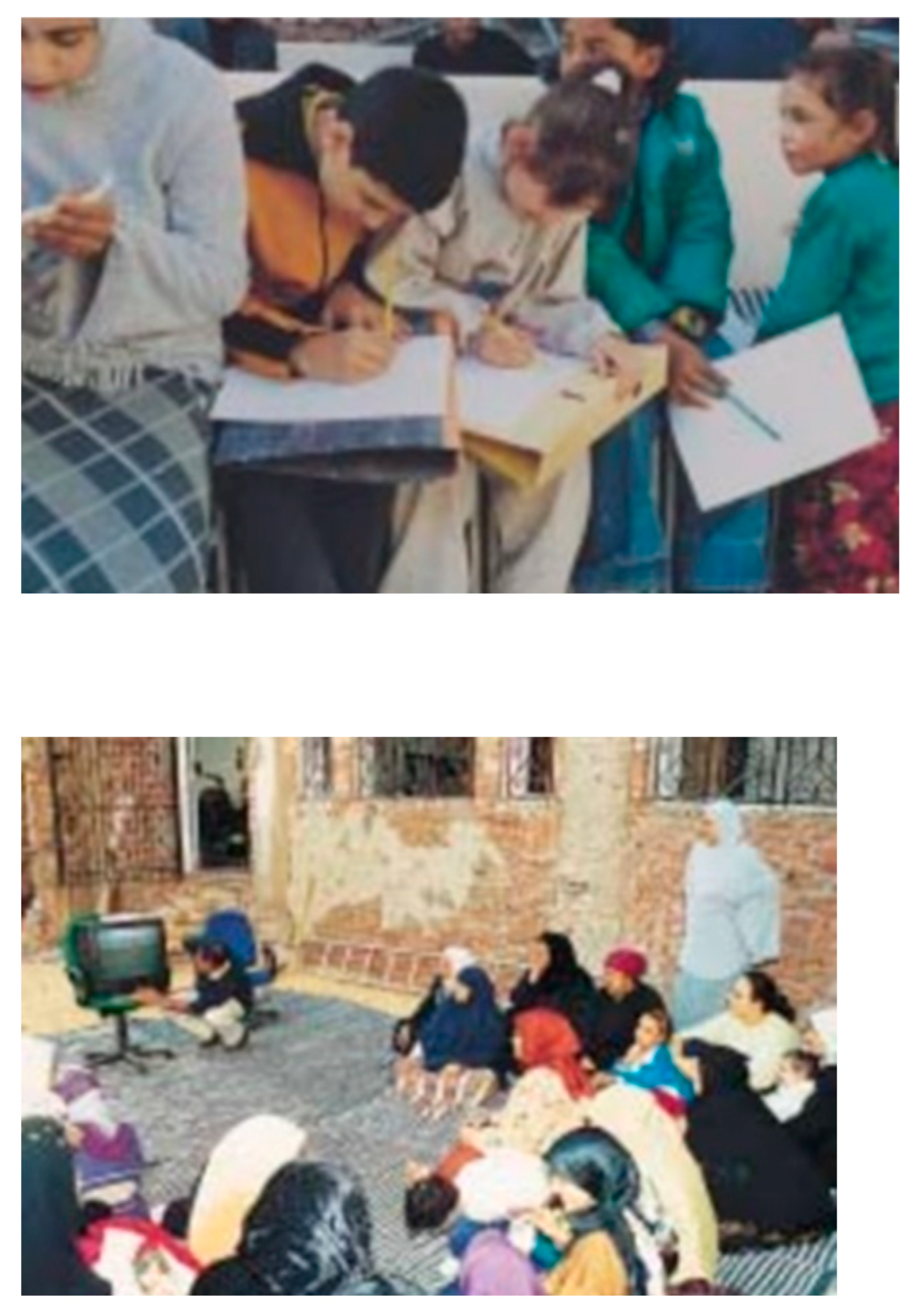

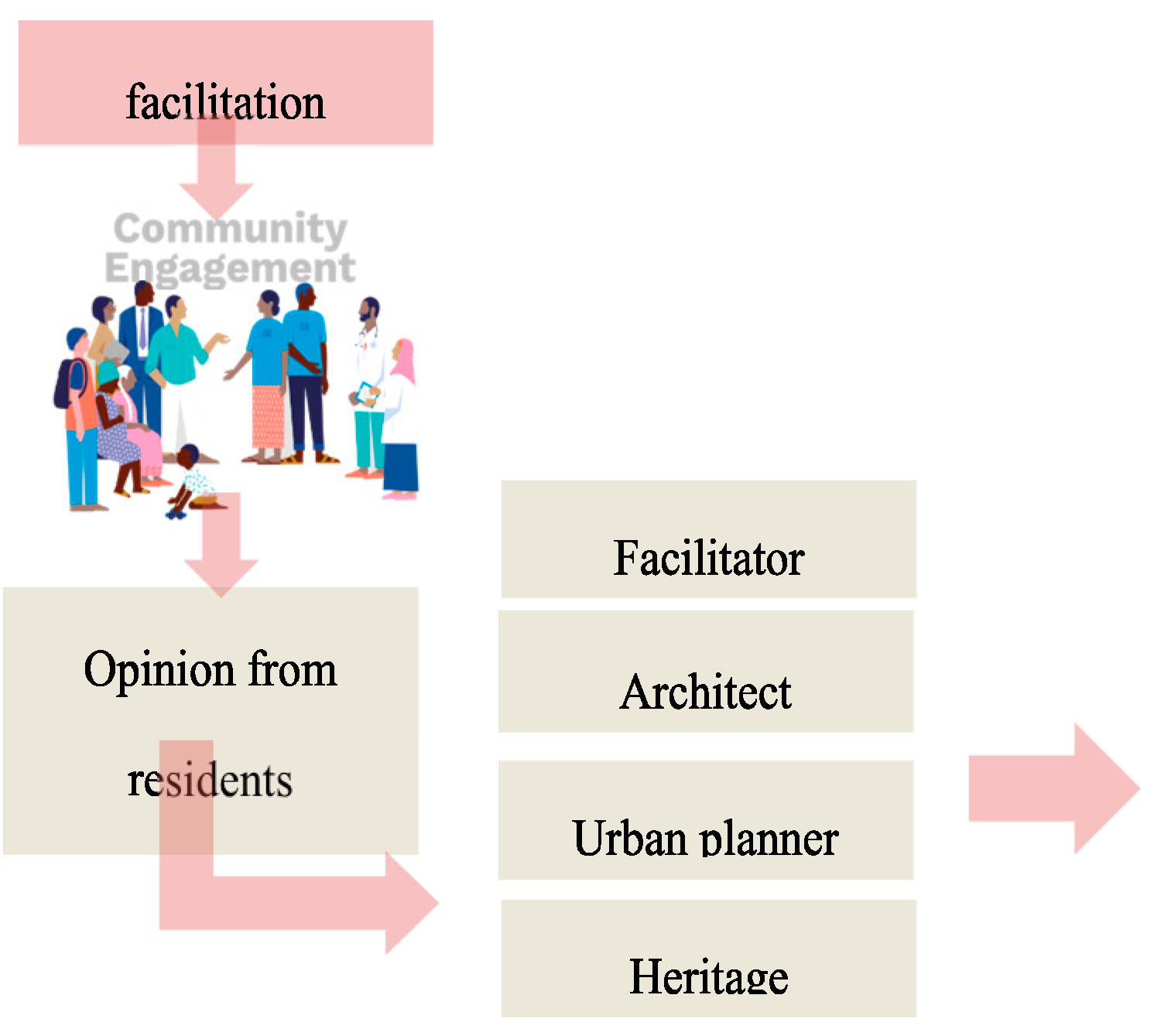

3.1.2. Al-Darb Al-Ahmar Housing Rehabilitation Program Community Engagement Framework:

3.1.3. Benefits of the Community Engagement Tool in the Outcomes:

3.2. JSPS PROJECT (Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.)

3.2.1. Project for Sustainable Conservation in the Historic Cairo/Community Development with the Participation of Local Residents” June 2022 to January 2023.

3.2.2. Details of the Project:

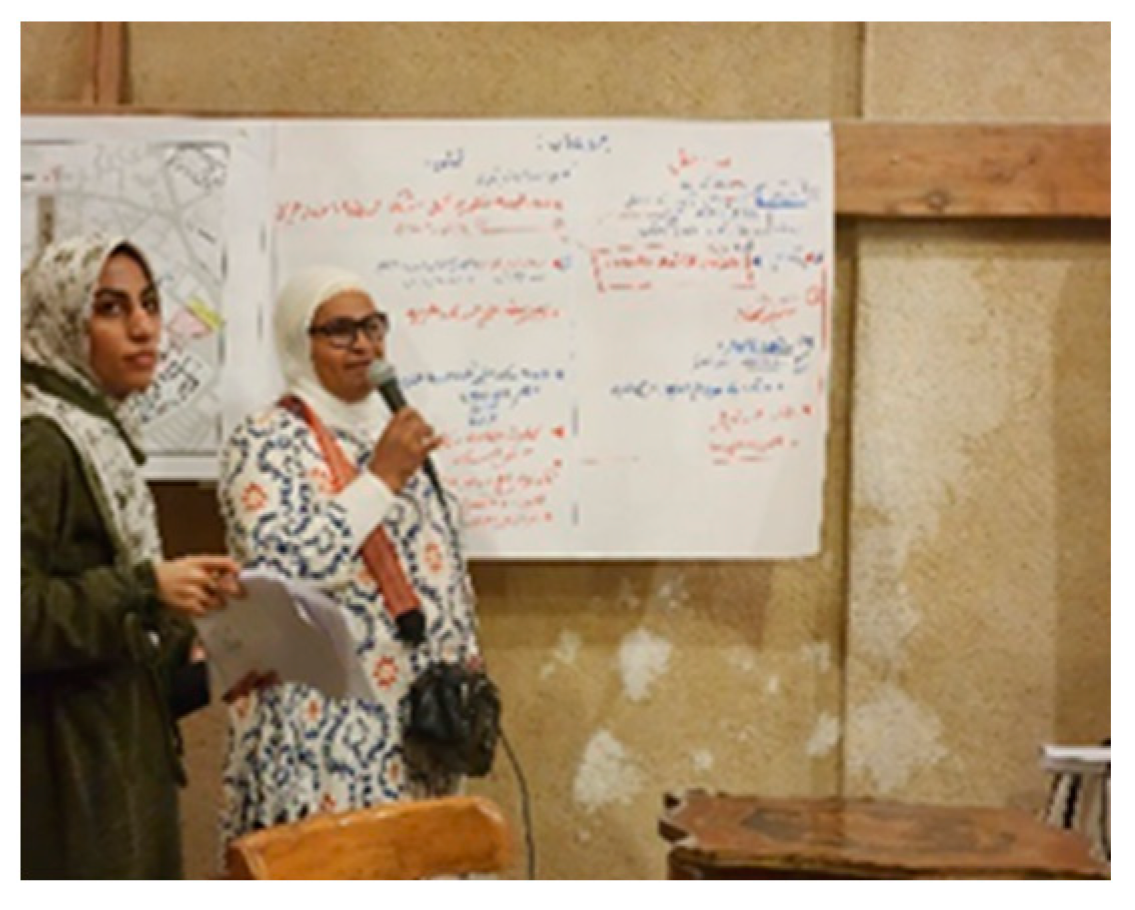

3.2.3. Project for Sustainable Conservation in the Historic Cairo /Community Development with the Participation of Local Residents Community Engagement Framework:

| Date | workshop Num | workshop Topic | Number of Facilitators | Number of Men | Ages Range of men | Numbers of women | Ages Range of women | conclusion |

| 26/6/2022 | 1 | Traffic in Al-darb Al-Ahmar,its problems and solutions | 6 | 8 | 35-50 | 13 | 30-45 | 1. Improve traffic management and infrastructure. 2. Enhance street safety and cleanliness. 3. Beautify the area with trees and lighting. 4. Utilize resources like empty lands and shopping carts. 5. Create a pedestrian-friendly and organized environment. |

| 24/7/2022 | 2 | Garbage collection for waste management inAl-Darb Al-Ahmar | 9 | 14 | 35-50 | 5 | 30-45 | 1. Promote community involvement in recycling and waste management. 2. Sort garbage at home and reuse materials creatively. 3. Use waste for fertilizer and surplus food to aid the poor. 4. Educate children on sustainability. 5. Create platforms for sharing used items. |

| 21/8/2022 | 3 | Risk management in Al-Darb Al-Ahmar,Historic Cairo | 8 | 13 | 35-50 | 16 | 30-45 | 1. Upgrade infrastructure for safety and fire prevention. 2. Convert vacant lands into gardens and . improve waste management. 3. Renovate streets and public spaces for emergencies. 4. Use schools and mosques as refuge points. 5. Raise awareness and reduce risks from utilities and factories. |

| 18/9/2022 | 4 | Reusing Historic Monuments For Residents in Al-Darb Al-Ahmar, Historic Cairo | 8 | 13 | 35-50 | 10 | 30-45 | 1. Restore historic buildings and address concerns about local businesses. 2. Repurpose Sabil Kokalian for community activities and exhibitions. 3. Use Sabil water in emergencies and improve facilities. 4. Open a restaurant and rehabilitate public spaces. 5. Operate the fire station and consider residents' opinions. |

| Date | workshop Num | Workshop topic | Number of Facilitators | Number of Men | Ages Range of men | Numbers of women | Ages Range of women | conclusion |

| 23/10/2022 | 5 | Intangible HeritageSouq Al-Silah, how to connect it with historical architecture | 7 | 8 | 35-50 | 9 | 30-45 | 1. Oral Traditions: Proverbs, stories, superstitions, and transportation signs. 2. Performing Arts: Traditional dances, instruments, and Mawlid shows. 3. Social Practices: Popular foods, cultural habits, and rituals. 4. Nature Customs: Practices linked to nature for good fortune. 5. Craft Skills: Traditional arts like Khayamiya, arabesques, and copperwork. |

| 26/11/2022 | 6 | Building Maintenance | 7 | 9 | 35-50 | 6 | 30-45 | 1. Promote cleaning campaigns and improve infrastructure. 2. Enhance fire safety and electrical systems. 3. Utilize groundwater for firefighting and set up waste sorting areas. 4. Encourage skill development through summer workshops. 5. Create community spaces for entertainment. |

| 18/12/2022 | 7 | Traditional crafts in the Al-Darb Al-Ahmar area | 6 | 18 | 35-50 | 10 | 30-45 | 1. Challenges: High costs, loss of crafts, and lack of support. 2. Solutions: Provide training, create exhibitions, and establish a trade union. 3. Awareness & Education: Promote crafts via media and schools. 4. Monitoring: Track artisans through a craft record. |

| 18/1/2023 | 8 | Tourism Settlement in Al-Darb Al-Ahmar area | 5 | 8 | 35-50 | 11 | 30-45 | 1. Challenges: Narrow streets, waste, and lack of accommodations. 2. Heritage & Crafts: Raise awareness, display crafts, and attract tourists. 3. Community Involvement: Engage locals in tourism, offering traditional drinks. 4. Promotion & Safety: Use social media for promotion and ensure tourist safety. |

3.2.4. Benefits of Community Engagement Tool in the Outcomes:

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- A Bjørgen, K Fossheim, C Macharis. How to build stakeholder participation in collaborative urban freight planning. Cities 2021, 112, 103149.

- A Egusquiza, M. Z. Systemic innovation areas for heritage-led rural regeneration: A multilevel repository of best practices. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Eyisi, D. L. (2021). Facilitating collaboration and community participation in tourism development: The case of South-Eastern Nigeria. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 5-10.

- A Mandić, J. K. (2021). governance for heritage tourism destinations: Contextual factors and destination management organization perspectives. Tourism Management Perspectives.

- A Piperno, C. I. (2023). Institutional Collective Actions for Culture and Heritage-Led Urban Regeneration: A Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Sustainability.

- AJ Miller-Rushing, N. A. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impacts on conservation research, management, and public engagement in US national parks. Biological journal.

- Alaa el-Habashy, N. F. (2022). Community Development with the Participation of Local Residents. Egypt : JSPS cairo research station.

- Alam, A. (2022). Mapping a Sustainable Future Through Conceptualization of Transformative Learning Framework, Education for Sustainable Development, Critical Reflection, and Responsible Citizenship: An Exploration of Pedagogies for Twenty-First Century Learning. ECS Transactions.

- Asadullah, Q. B. (2023). Impact of tourism development upon environmental sustainability: a suggested framework for sustainable ecotourism. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 6-9.

- Beiming Hu, F. H. (2022). Community Empowerment Under Powerful Government: A Sustainable Tourism Development Path for Cultural Heritage Sites. Frontiers in Psychology, 1-4.

- Bose, B. (2021). The Terracotta temple of Antpur: An Attempt to Study the Importance of Heritage Management. Society for Heritage, Archaeology & Management, 5-8.

- C Rendon, KK Osman, KM Faust. (2021). Path towards community resilience: Examining stakeholders' coordination at the intersection of the built, natural, and social systems. Sustainable cities and society, 10.

- D Brodzinsky, M. G. (2022). Adoption and trauma: Risks, recovery, and the lived experience of adoption. Child Abuse & Neglect.

- D Zhu, A. A.-J. (2024). Digital Storytelling Intervention for Enhancing the Social Participation of People With Mild Cognitive Impairment: Co-Design and Usability Study. Jmir Publications.

- Devindi Geekiyanage, T. F. (2021). Assessing the state of the art in community engagement for participatory decision-making in disaster risk-sensitive urban development. International journal of cultural heritage.

- DM Zocchi, M. F. (2021 ). Recognising, safeguarding, and promoting food heritage: challenges and prospects for the future of sustainable food systems. Sustainability.

- E Bruley, B. L. (2021). Nature's contributions to people: Coproducing quality of life from multifunctional landscapes. Ecology and Society.

- Eduardo, S. Brondízio1, 2. Y.-T.-L.-G. (2021). Locally Based, Regionally Manifested, and Globally Relevant: Indigenous and Local Knowledge, Values, and Practices for Nature. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 485-487.

- EG Martín, R. G. Using a system thinking approach to assess the contribution of nature based solutions to sustainable development goals. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 738, 139693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EK Elbes, L. O. (2022). Character building in English for daily conversation class materials for English education freshmen students. Journal of English Language Teaching, 12.

- Ferreira, A. T. (2020). Towards a Historic Urban Landscape approach: community engagement through local population’s perception on heritage. ERDF).

- H Jie, I. K. (2023). energy policy, socio-economic development, and ecological footprint: The economic significance of natural resources, population growth, and industrial development. Utilities Policy, 6-10.

- H Pineo, N. Z. (2020). Integrating health into the complex urban planning policy and decision-making context: A systems thinking analysis. Palgrave Communications, 3-6.

- H Solman, M. S. (2021). Co-production in the wind energy sector: A systematic literature review of public engagement beyond invited stakeholder participation. eEnergy Research & social Science.

- Haigen Xu , Y. C. (2021). Ensuring effective implementation of the post-2020 global biodiversity targets. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2-3.

- J Li, S Krishnamurthy. (2020). Informing or consulting? Exploring community participation within urban heritage management in China. Habitat International, 21:22.

- J Li, S. K. (2020). Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities, Elsevier.

- J Ocloo, S. G. (2021). Exploring the theory, barriers and enablers for patient and public involvement across health, social care and patient safety: a systematic review of reviews. Health research policy and systems, 4-5.

- J Sharp, V. P. (2020). Just art for a just city: Public art and social inclusion in urban regeneration. Culture-Led Urban Regeneration.

- Jagtap, S. (2022). Co-design with marginalised people: designers' perceptions of barriers and enablers. CoDesign, 15-20.

- Joshi, L. R. (2017). Community Engagement in Post-Earthquake Nepal: Lessons from Bhaktapur. International Journal of Heritage Studies., 12-18.

- K Bernard, C. C. (2022). Attachment goes to court: Child protection and custody issues. Attachment & Human Development.

- K Nordberg, Å. M. (2020). Community-driven social innovation and quadruple helix coordination in rural development. Case study on LEADER group Aktion Österbotten. Journal of Rural Studies.

- L Somerwill, U. W. (2022). How to measure the impact of citizen science on environmental attitudes, behaviour and knowledge? A review of state-of-the-art approaches. Environmental Sciences Europe, 8-11.

- Labadi, S. G. (2021). Heritage and the Sustainable Development Goals: Policy Guidance for Heritage and Development Actors."ICOMOS". Kent Academic Repository.

- Li, J. K. (2020). Community participation in cultural heritage management: A systematic literature review comparing Chinese and international practices. Cities, 1-4.

- M Chahardowli, H. S. Survey of sustainable regeneration of historic and cultural cores of cities. Energies 2020, 13, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M Ghobakhloo, M. I. (2022). Identifying industry 5.0 contributions to sustainable development: A strategy roadmap for delivering sustainability values. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 716-737.

- MA Habib, F. D. (2021). Knowledge, attitude and practice survey of COVID-19 pandemic in Northern Nigeria. PloS one, 10-15.

- NA Bizami, Z. T. (2023). Innovative pedagogical principles and technological tools capabilities for immersive blended learning: a systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies, 7-10.

- NH Tien, N. N. Sustainable Development of Higher Education Institutions in Developing Countries: Comparative Analysis of Poland and Vietnam. Contemporary economics 2022, 16, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P Camangian, S. C. (2022). Social and emotional learning is hegemonic miseducation: Students deserve humanization instead. Race Ethnicity and Education, 18-21.

- Pappalardo, G. (2020). Community-Based processes for revitalizing heritage: Questioning justice in the experimental practice of ecomuseums. Sustainability.

- Q Jia, L. J. (2023). Linking supply-demand balance of ecosystem services to identify ecological security patterns in urban agglomerations. Sustainable Cities and Society.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2023). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 445-447.

- Ronchi, A. T. (2020). Community involvement in built heritage conservation. UCL press, 66-77.

- RT Buxton, E. N. (2020). Avoiding wasted research resources in conservation science. Conservation Science and Practice, 3-5.

- Sendra, P. (2024). The ethics of co-design. Journal of Urban Design, 17-18.

- Sharma, S. T. (2019). Sustainable Restoration Practices in Heritage Sites: Bhaktapur as a Case Study. Kathmandu University Press., 11-14.

- Thapa, R. K. (2018). Integrating Traditional Building Techniques in Urban Development: A Bhaktapur Perspective.. Journal of Urban Heritage, 10-15.

- Torabi, F. S. H. (2021). Can public awareness, knowledge and engagement improve climate change adaptation policies? Discover Sustainability, 5-7.

- UNESCO. (2020). World Heritage City lab. Paris.

- Usmaedi Usmaedi, M. A. (2024). Cultural heritage preservation through community engagement a new paradigm for social sustainability. sustainabilty, pp 50-59.

- Vuong, Q.-H. (2021). The Semiconducting Principle of Monetary and Environmental Values Exchange. Economics and Business Letters, 286-287.

- Walter Leal Filho, F. F. (2021). A Framework for the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals in University programmes. Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 299.

- Wiktor-Mach, D. (2020). What role for culture in the age of sustainable development? UNESCO's advocacy in the 2030 Agenda negotiations. International Journal of Cultural Policy.

- WM Seyoum, A. Y. (2022). STUDENTS'ATTITUDES AND PROBLEMS ON QUESTION-BASED ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY WRITING INSTRUCTION. Journal of English.

- X Chu, Z Shi, L Yang. Evolutionary game analysis on improving collaboration in sustainable urban regeneration: A multiple-stakeholder perspective. urban planning and development 2020, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxu Liang, Y. L. (2021). A review of the role of social media for the cultural heritage sustainability. Sustainability, 7-10.

- Z Aripin, S. M. (2023). SUSTAINABILITY MANAGEMENT EFFORTS IN EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES: BUILDING A RECIPROCITY FRAMEWORK FOR COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT. development and community.

- Z Mthembu, M. C. (2023). Community engagement: health research through informing, consultation, involving and empowerment in Ingwavuma community. Frontiers in Public Health, 4-7.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).