Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Description

2.2. Field Surveys on Monthly Occurrence of Galerucella birmanica in Brasenia schreberi Pond

2.3. Comparison of Galerucella birmanica Occurrence in Relatively Intact and Severely Chewed Areas

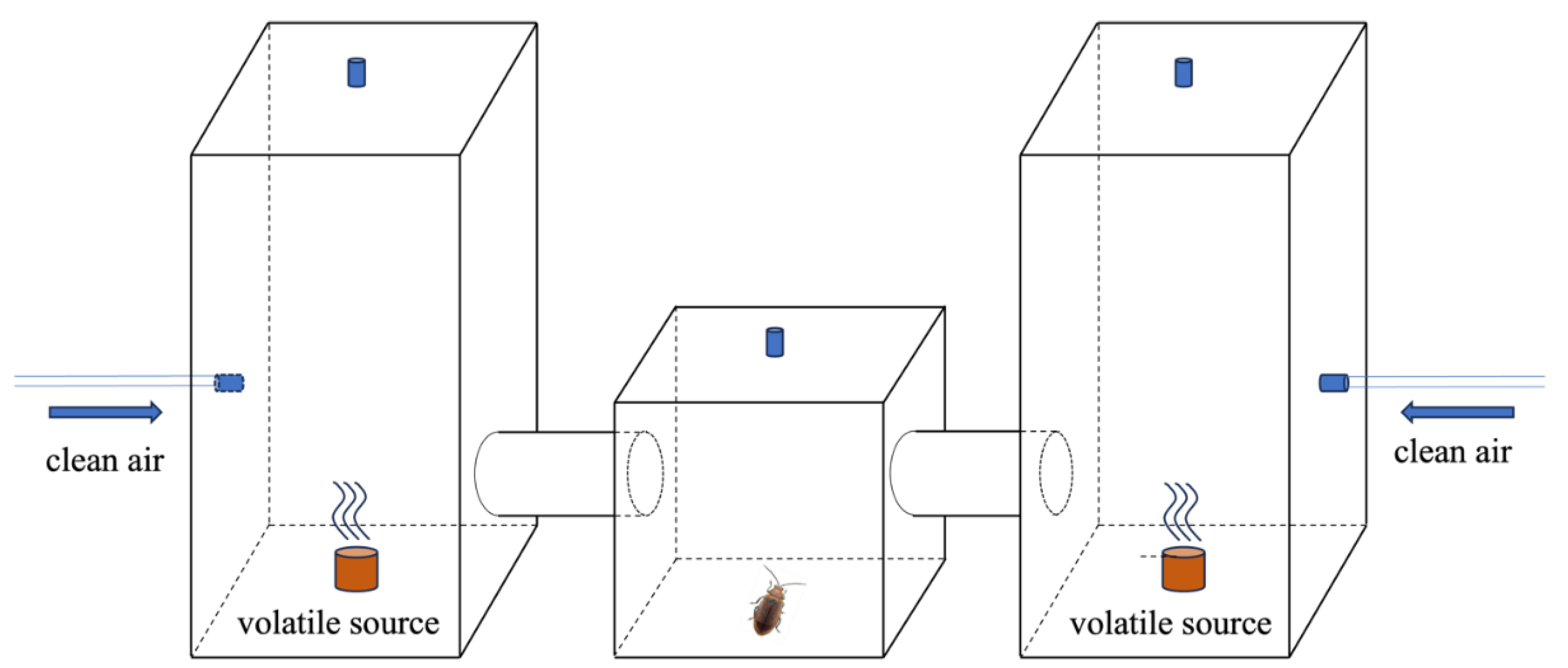

2.4. Two-Choice Tests of Adult Galerucella birmanica Towards Volatiles from Intact and Chewed Brasenia schreberi Leaves

2.5. GC-MS Analysis for Volatiles from Intact and Chewed B. schreberi Leaves

2.6. Verification of Volatile Substance that Attracting Galerucella birmanica

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

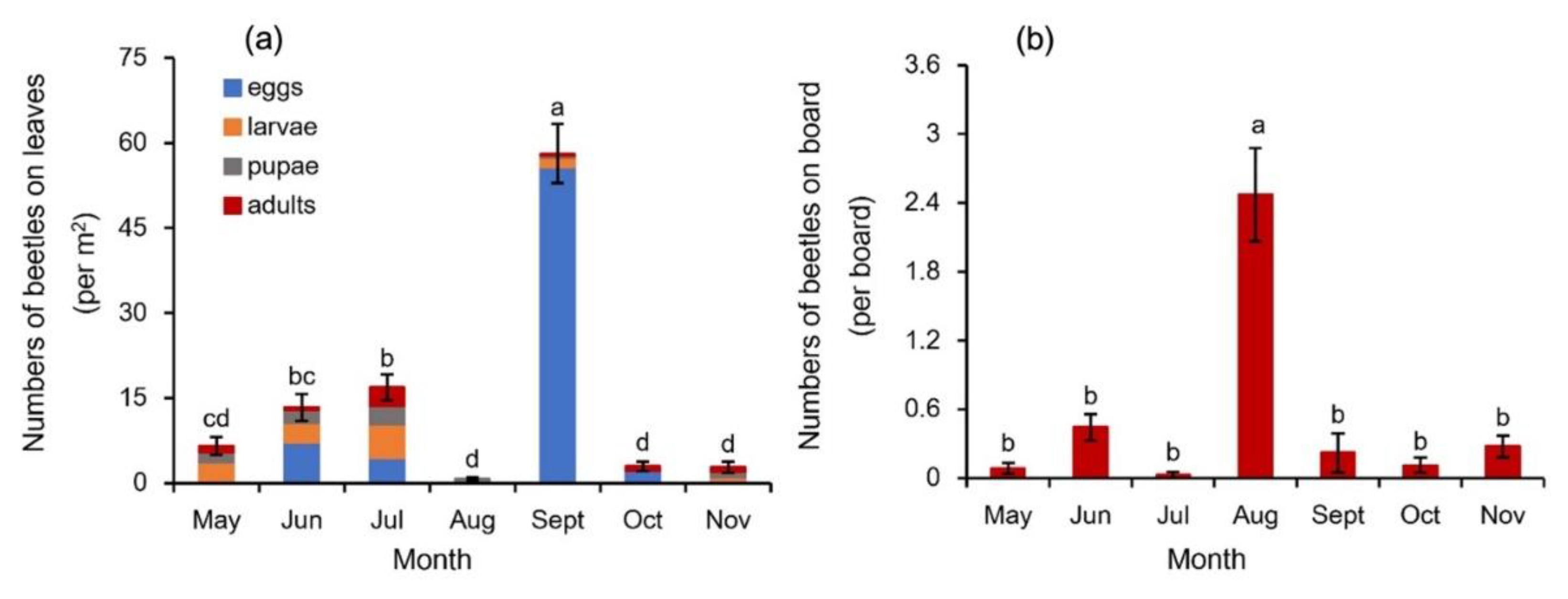

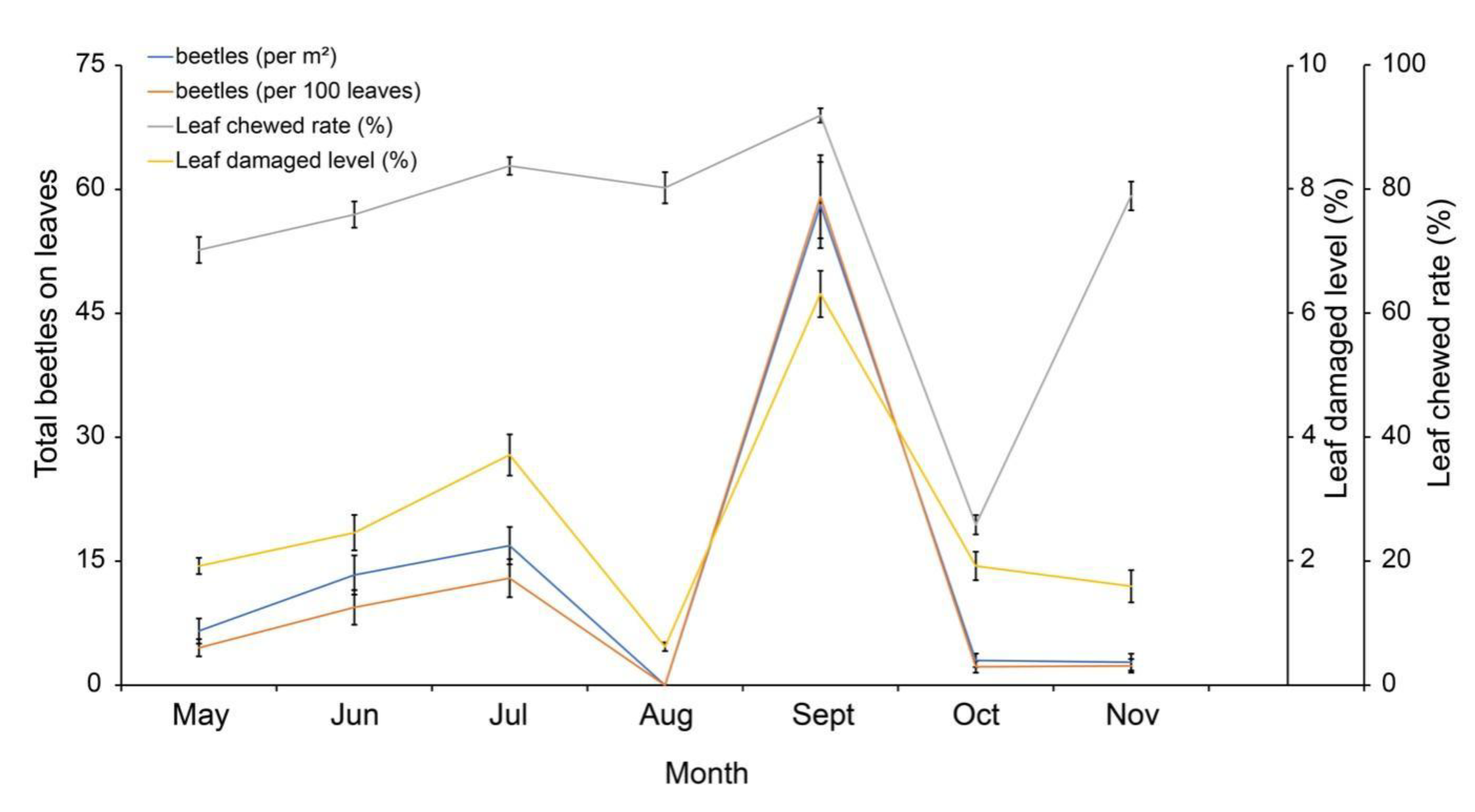

3.1. Monthly Occurrence of Galerucella birmanica in Brasenia schreberi Pond

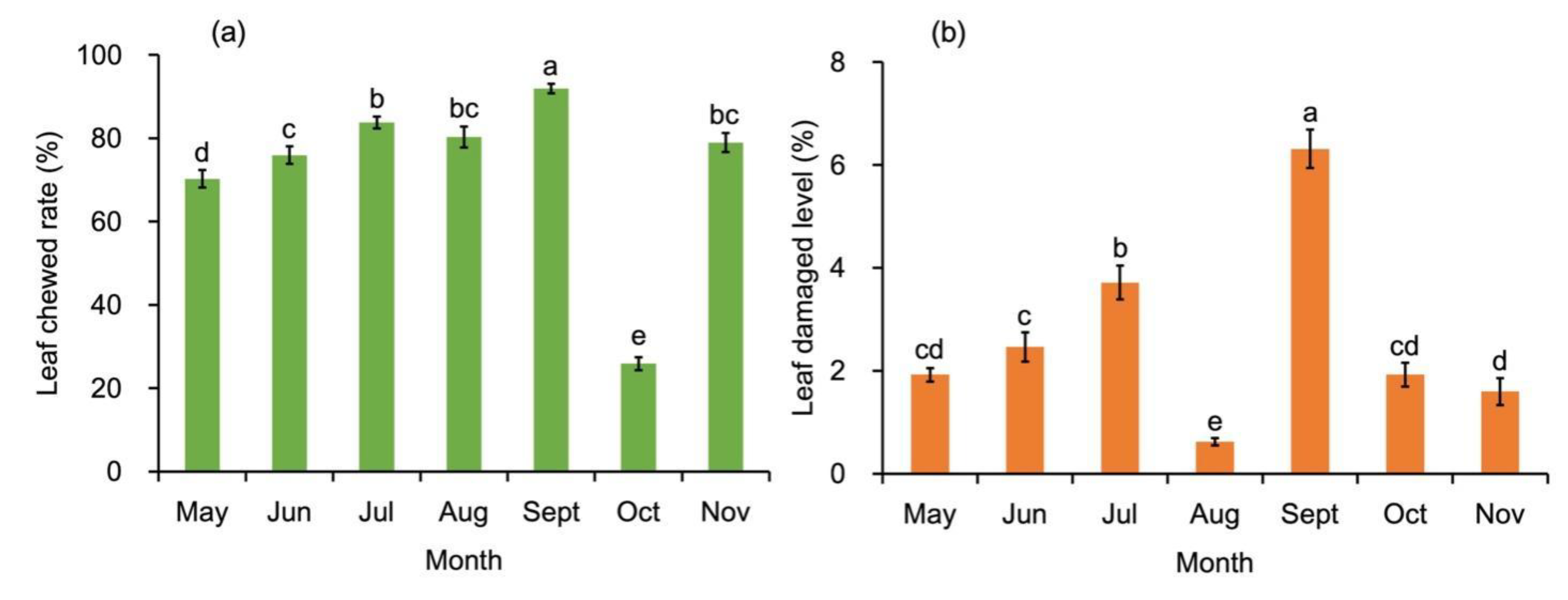

3.2. Leaf Damage Condition of Brasenia schreberi and Its Correlation with Galerucella birmanica Occurrence

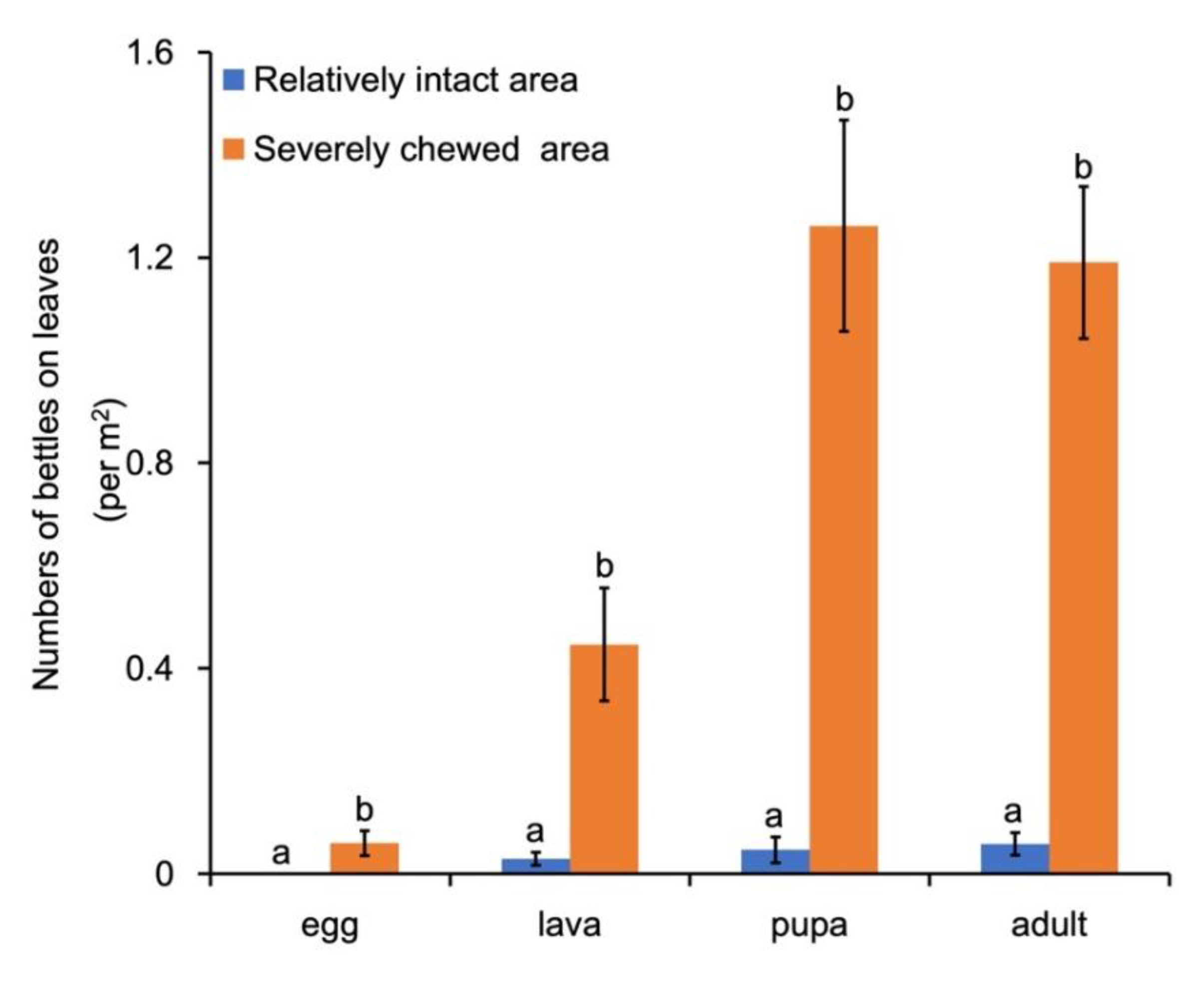

3.3. Aggregation of Galerucella birmanica in Brasenia schreberi Pond

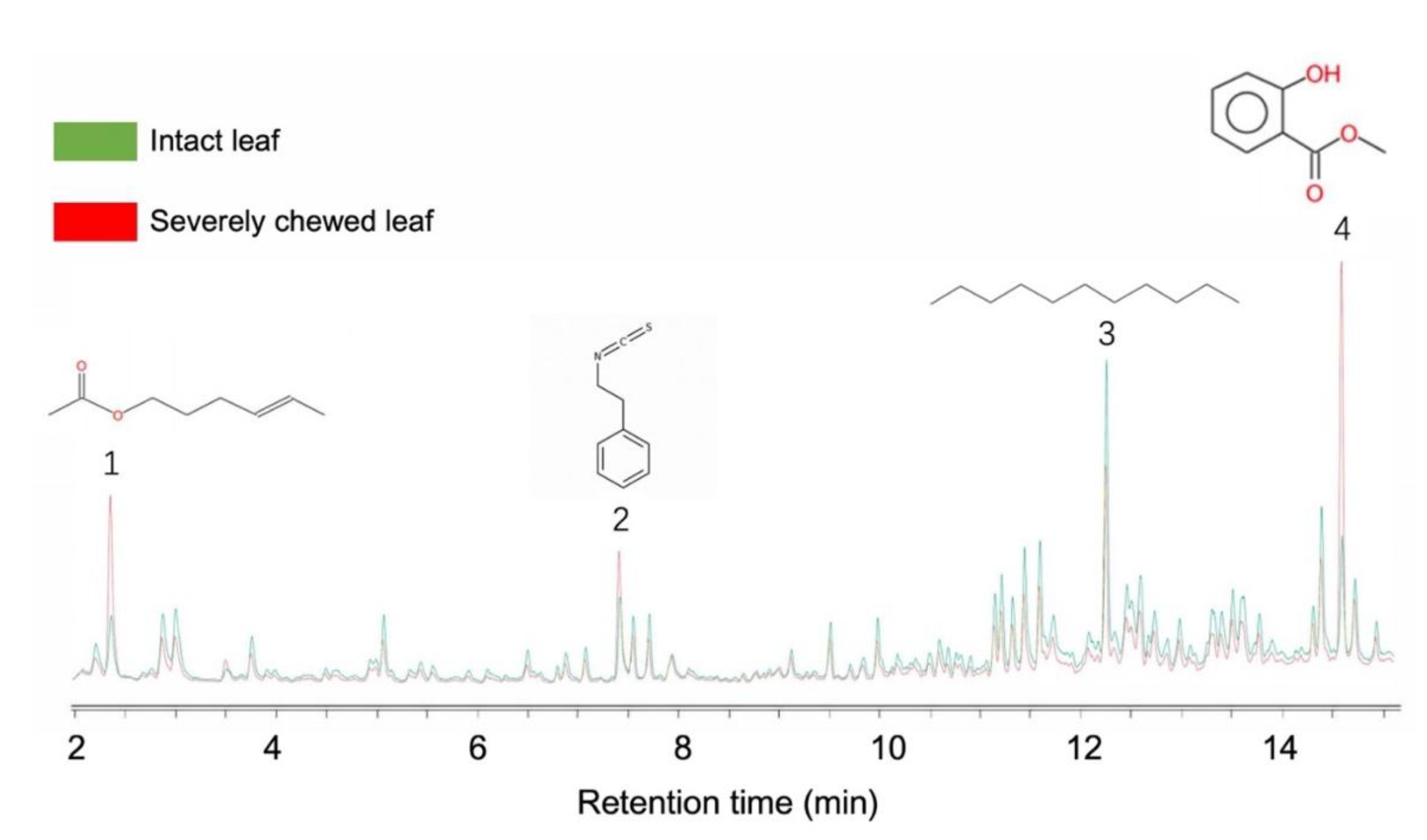

3.4. Volatiles Differed Between Intact and Chewed Brasenia schreberi Leaves

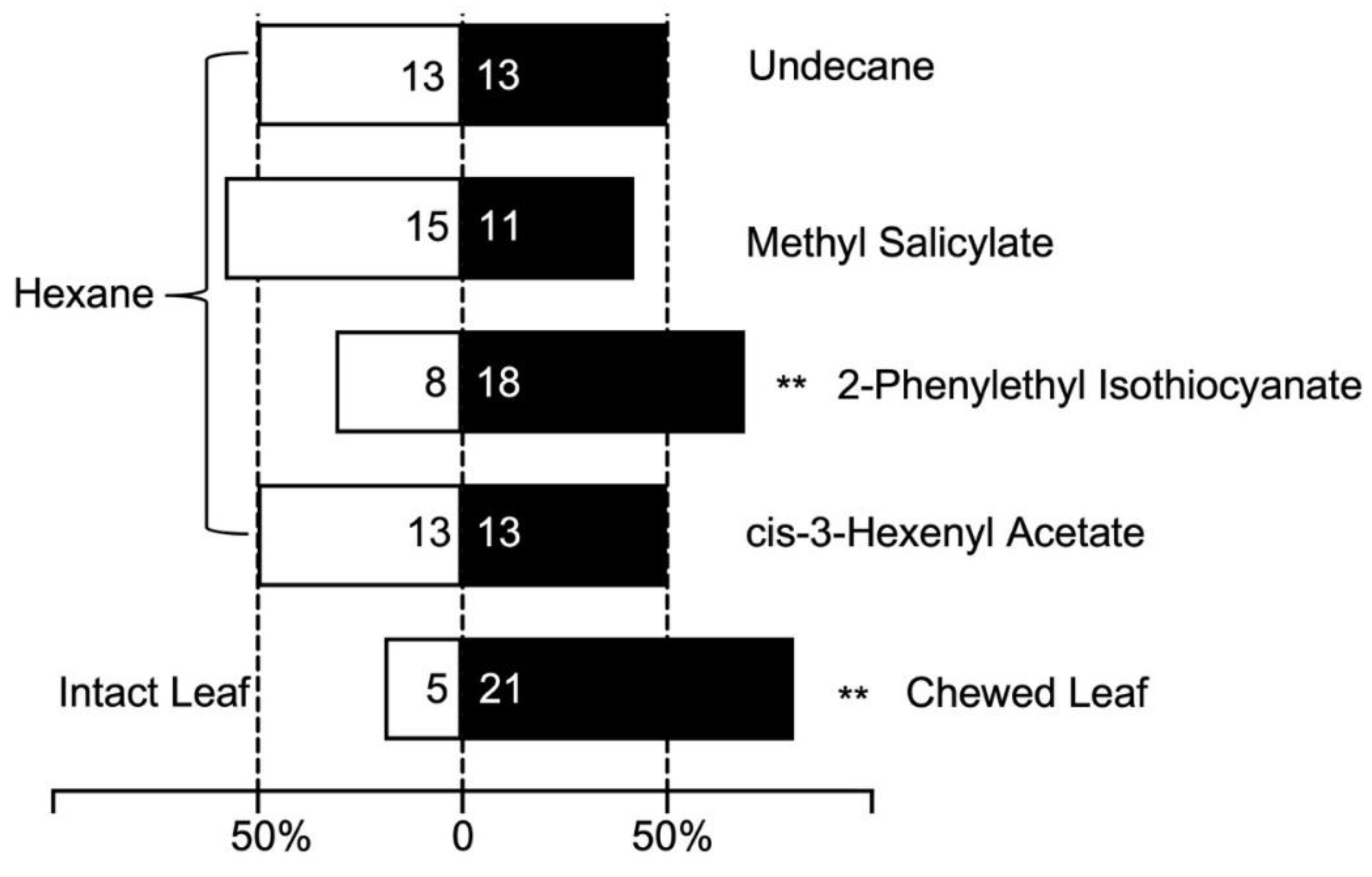

3.5. Two-Choice Test of Volatiles from Brasenia schreberi by Adult Galerucella birmanica

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Song, X.; Hu, H.; Wang, D.; Chen, J.; Ma, Y.; Ma, X.; Ren, X.; Ma, Y. Knockdown of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine pyrophosphorylase and chitin synthase A increases the insecticidal efficiency of Lufenuron to Spodoptera exigua. Pestic Biochem Physiol 2022, 186, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, T.; Hou, Y.; Wilson, K.; Wang, X.; Su, C.; Li, Y.; Ren, G.; Xu, P. Densovirus infection facilitates plant-virus transmission by an aphid. New Phytol 2024, 243, 1539–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Bi, Y.D.; Liu, M.; Li, W.; Liu, M.; Di, S.F.; Yang, S.; Fan, C.; Bai, L.; Lai, Y.C. Identification and expression profiles analysis of odorant-binding proteins in soybean aphid, Aphis glycines (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Insect Sci 2020, 27, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inayat, R.; Khurshid, A.; Boamah, S.; Zhang, S.; Xu, B. Mortality, Enzymatic Antioxidant Activity and Gene Expression of Cabbage Aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae L.) in Response to Trichoderma longibrachiatum T6. Front Physiol 2022, 13, 901115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, D.M. Interactions between resource availability and enemy release in plant invasion. Ecol Lett 2006, 9, 887–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, T.; Zhou, S.; Chen, J.; Pang, L.; Ye, X.; Shi, M.; Huang, J.; et al. Symbiotic bracovirus of a parasite manipulates host lipid metabolism via tachykinin signaling. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, e1009365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinero, J.C.; Souder, S.K.; Vargas, R.I. Vision-mediated exploitation of a novel host plant by a tephritid fruit fly. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Yi, T.; Li, Y.Y.; Xu, T.; Chen, L.; Xu, H. A green leaf volatile, (Z)-3-hexenyl-acetate, mediates differential oviposition by Spodoptera frugiperda on maize and rice. BMC Biol 2023, 21, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Zhang, S.S.; Niu, B.L.; Ji, D.F.; Liu, X.J.; Li, M.W.; Bai, H.; Palli, S.R.; Wang, C.Z.; Tan, A.J. A determining factor for insect feeding preference in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. PLoS Biol 2019, 17, e3000162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karssemeijer, P.N.; de Kreek, K.A.; Gols, R.; Neequaye, M.; Reichelt, M.; Gershenzon, J.; van Loon, J.J.A.; Dicke, M. Specialist root herbivore modulates plant transcriptome and downregulates defensive secondary metabolites in a brassicaceous plant. New Phytol 2022, 235, 2378–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Du, L.; Chen, Q.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Tian, K.; Cao, S.; Huang, T.; Jacquin-Joly, E.; et al. Odorant Receptors for Detecting Flowering Plant Cues Are Functionally Conserved across Moths and Butterflies. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, E.L.; Carlquist, S. Vessels in Brasenia (Cabombaceae): New perspectives on vessel origin in primary XYLEM OF ANGIOSPERMS. American Journal of Botany 1996, 83, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Luan, D.; Ning, K.; Shao, P.; Sun, P. Ultrafiltration isolation, hypoglycemic activity analysis and structural characterization of polysaccharides from Brasenia schreberi. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 135, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Feng, S.; Yan, J.; Luan, D.; Sun, P.; Shao, P. Antidiabetic potential of polysaccharides from Brasenia schreberi regulating insulin signaling pathway and gut microbiota in type 2 diabetic mice. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Ai, T.; Yin, C.; Liu, H.; Qin, R. A special polysaccharide hydrogel coated on Brasenia schreberi: preventive effects against ulcerative colitis via modulation of gut microbiota. Food Funct 2023, 14, 3564–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Fang, Q.; Feng, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, W.; Wei, Q. Polysaccharides from Brasenia schreberi with Great Antioxidant Ability and the Potential Application in Yogurt. Molecules 2023, 29, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Li, J.; Pan, F.; Fu, J.; Zhou, W.; Lu, S.; Li, P.; Zhou, C. Environmental factors influencing mucilage accumulation of the endangered Brasenia schreberi in China. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 17955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhong, Z. Watershield (Brasenia schreberi J. F. Gmel.), from Popular Vegetable to Endangered Species. World Journal of Agriculture and Soil Science 2021, 6, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, X. Monitoring populations of Galerucella birmanica (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) on Brasenia schreberi and Trapa natans (Lythraceae): Implications for biological control. Biological Control 2007, 43, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, W.; Blossey, B. Host plant phylogeny does not fully explain host choice and feeding preferences of Galerucella birmanica, a promising biological control herbivore of Trapa natans. Biological Control 2023, 180, 105201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, S.; Chen, Z. Preliminary studies on the beetle (Galerucella Birmanica Jacoby) - an insect pest of waterchestnut and watershield. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 1984, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.; Blossey, B.; Du, Y.; Zheng, F. Galerucella birmanica (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a promising potential biological control agent of water chestnut, Trapa natans. Biological Control 2006, 36, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Huang, M.; Li, S.; Zeng, X.; Hu, G.; Tang, C. Occurrence and integrated control measures of Galerucella birmanica Jacoby. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences 2015, 43, 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemberton, R.W. Natural enemies of Trapa spp. in Northeast Asia and Europe. Biological Control 1999, 14, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bisch-Knaden, S.; Fandino, R.A.; Yan, S.; Obiero, G.F.; Grosse-Wilde, E.; Hansson, B.S.; Knaden, M. The olfactory coreceptor IR8a governs larval feces-mediated competition avoidance in a hawkmoth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116, 21828–21833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Komail Raza, S.A.; Wei, Z.; Keesey, I.W.; Parker, A.L.; Feistel, F.; Chen, J.; Cassau, S.; Fandino, R.A.; Grosse-Wilde, E.; et al. Competing beetles attract egg laying in a hawkmoth. Curr Biol 2022, 32, 861–869 e868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekholm, A.; Faticov, M.; Tack, A.J.M.; Berger, J.; Stone, G.N.; Vesterinen, E.; Roslin, T. Community phenology of insects on oak: local differentiation along a climatic gradient. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, C.H.; Lee, M.J.; Grim, M.; Schroeder, J.; Young, H.S. Interactions between temperature and predation impact insect emergence in alpine lakes. Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.S.; Du, Y.Z.; Wang, Z.J.; Xu, J.J. Effect of temperature on the demography of Galerucella birmanica (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Insect Science 2008, 15, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Gou, W.; Ma, W.; Tang, L.; Hu, G.; Sun, Y. Effects of temperature on the growth, development and reproduction of Diorhabda rybakowi (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). Plant Protection 2023, 49, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoume, S.; Bressac, C.; Chevrier, C. Sperm production and mating potential of males after a cold shock on pupae of the parasitoid wasp Dinarmus basalis (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). J Insect Physiol 2007, 53, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Zhang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Luo, L.; Lei, C.; Jiang, X. Age-stage two-sex life table for laboratory populations of oriental armyworm Mythimna separata (Walker) under different temperatures. Acta Phytophylacica Sinica 2017, 44, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, Z.; Qu, J.; Zhang, F.; Yin, X.; Xu, Y. Responses of Harmonia axyridis (Pallas) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) adults to cold acclimation and the related changes of activities of several enzymes in their bodies. Acta Entomologica Sinica 2010, 53, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.H.; Chen, B.; Kang, L. Impact of mild temperature hardening on thermotolerance, fecundity, and Hsp gene expression in Liriomyza huidobrensis. J Insect Physiol 2007, 53, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Cossé, A.A.; Zilkowski, B.W.; Bartlelt, R.J. Aggregation pheromone of the cereal leaf beetle: Field evaluation and emission from males in the laboratory. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2003, 29, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, F.; Zheng, Y.; Lu, Y.; Qiang, C.; Ding, J. Spatial distribution pattern of water chestnut beetle (Galerucella birmanica Jacoby). Chinese journal of eco-agriculture 2006, 14, 171–175. [Google Scholar]

- Turlings, T.C.J.; Erb, M. Tritrophic Interactions Mediated by Herbivore-Induced Plant Volatiles: Mechanisms, Ecological Relevance, and Application Potential. Annual Review of Entomology 2018, 63, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maselou, D.A.; Anastasaki, E.; Milonas, P.G. The Role of Host Plants, Alternative Food Resources and Herbivore Induced Volatiles in Choice Behavior of an Omnivorous Predator. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 2019, 6, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dong, W.; Li, H.; D'Onofrio, C.; Bai, P.; Chen, R.; Yang, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, B.; et al. Molecular basis of (E)-beta-farnesene-mediated aphid location in the predator Eupeodes corollae. Curr Biol 2022, 32, 951–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Xu, L.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Xu, Y. Host Plant Species of Bemisia tabaci Affect Orientational Behavior of the Ladybeetle Serangium japonicum and Their Implication for the Biological Control Strategy of Whiteflies. Insects 2020, 11, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Felton, G.W. Priming of antiherbivore defensive responses in plants. Insect Sci 2013, 20, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yan, X. The role of glucosinolates in plant-biotic environment interactions. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2007, 27, 2584–2593. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, I.; Rohloff, J.; Bones, A.M. Defence mechanisms of Brassicaceae: implications for plant-insect interactions and potential for integrated pest management. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2010, 30, 311–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, J.A.A. The chemical world of crucivores: lures, treats and traps. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2003, 104, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.A.; Kurashige, N.S. A role for isothiocyanates in plant resistance against the specialist herbivore Pieris rapae. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2003, 29, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstock, U.; Agerbirk, N.; Stauber, E.J.; Olsen, C.E.; Hippler, M.; Mitchell-Olds, T.; Gershenzon, J.; Vogel, H. Successful herbivore attack due to metabolic diversion of a plant chemical defense. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 4859–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, C.; Agerbirk, N.; Olsen, C.E.; Boevé, J.-L.; Schaffner, U.; Brakefield, P.M. Sequestration of host plant glucosinolates in the defensive hemolymph of the sawfly Athalia rosae. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2001, 27, 2505–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, T.J.A. Glucosinolates in oilseed rape: secondary metabolites that influence interactions with herbivores and their natural enemies. Annals of Applied Biology 2014, 164, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlet, E.; Blight, M.M.; Hick, A.J.; Williams, I.H. The responses of the cabbage seed weevil (Ceutorhynchus assimilis) to the odor of oilseed rape (Brassica napus) and to some volatile isothiocyanates. Entomologia Experimentalis Et Applicata 1993, 68, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, L.E.; Blight, M.M. Response of the pollen beetle, Meligethes aeneus, to traps baited with volatiles from oilseed rape, Brassica napus. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2000, 26, 1051–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, F.; Burgueno, A.P.; Gonzalez, A.; Rossini, C. Better Together: Volatile-Mediated Intraguild Effects on the Preference of Tuta absoluta and Trialeurodes vaporariorum for Tomato Plants. J Chem Ecol 2023, 49, 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, M.; Ton, J. Long-distance signalling in plant defence. Trends Plant Sci 2008, 13, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Wang, Y.; He, L.; Huang, F.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wei, X.; Han, M.; Deng, H.; Luo, L.; et al. Molecular basis of methyl-salicylate-mediated plant airborne defence. Nature 2023, 622, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.; Du, L.; Liu, Q.; Hu, X.; Ye, W.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Li, Y. Stemborer-induced rice plant volatiles boost direct and indirect resistance in neighboring plants. New Phytol 2023, 237, 2375–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberth, J.; Alborn, H.T.; Schmelz, E.A.; Tumlinson, J.H. Airborne signals prime plants against insect herbivore attack. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 1781–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Gong, X.L.; Li, G.C.; Huang, L.Q.; Ning, C.; Wang, C.Z. A gustatory receptor tuned to the steroid plant hormone brassinolide in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Elife 2020, 9, e64114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Wang, S.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, H.; Jiang, L.; McLamore, E.S.; Shen, Y. The WRKY46-MYC2 module plays a critical role in E-2-hexenal-induced anti-herbivore responses by promoting flavonoid accumulation. Plant Commun 2024, 5, 100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wari, D.; Aboshi, T.; Shinya, T.; Galis, I. Integrated view of plant metabolic defense with particular focus on chewing herbivores. J Integr Plant Biol 2022, 64, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, K.D.; Agrawal, A.A. Induced resistance mitigates the effect of plant neighbors on susceptibility to herbivores. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foba, C.N.; Shi, J.H.; An, Q.Q.; Liu, L.; Hu, X.J.; Hegab, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, P.M.; Wang, M.Q. Volatile-mediated tritrophic defense and priming in neighboring maize against Ostrinia furnacalis and Mythimna separata. Pest Manag Sci 2023, 79, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choh, Y.; Ozawa, R.; Takabayashi, J. Do plants use airborne cues to recognize herbivores on their neighbours? Exp Appl Acarol 2013, 59, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blassioli-Moraes, M.C.; Michereff, M.F.F.; Magalhães, D.M.; Morais, S.D.; Hassemer, M.J.; Laumann, R.A.; Meneghin, A.M.; Birkett, M.A.; Withall, D.M.; Medeiros, J.N.; et al. Influence of constitutive and induced volatiles from mature green coffee berries on the foraging behaviour of female coffee berry borers, Hypothenemus hampei (Ferrari) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2018, 13, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Zhang, J.; Yan, Q.; Miao, C.L.; Han, W.K.; Hou, W.; Yang, K.; Hansson, B.S.; Peng, Y.C.; Guo, J.M.; et al. The Molecular Basis of Host Selection in a Crucifer-Specialized Moth. Curr Biol 2020, 30, 4476–4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurr, G.M.; Wratten, S.D.; Landis, D.A.; You, M. Habitat Management to Suppress Pest Populations: Progress and Prospects. Annu Rev Entomol 2017, 62, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Beetles on leaves (per m2) | Beetles on leaves (per hundred leaves) | Beetles on board | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| egg | larva | pupa | adult | total | |||

| Leaf chewed rate |

0.3846 (0.0000) |

0.2416 (0.0001) |

0.2264 (0.0003) |

0.1011 (0.1095) |

0.4533 (0.0000) |

0.4641 (0.000) |

0.1586 (0.0117) |

| Leaf damaged level |

0.6431 (0.0000) |

0.3919 (0.0000) |

0.3509 (0.0000) |

0.2691 (0.0000) |

0.7809 (0.0000) |

0.7783 (0.0000) |

-0.3034 (0.0000) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).