Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

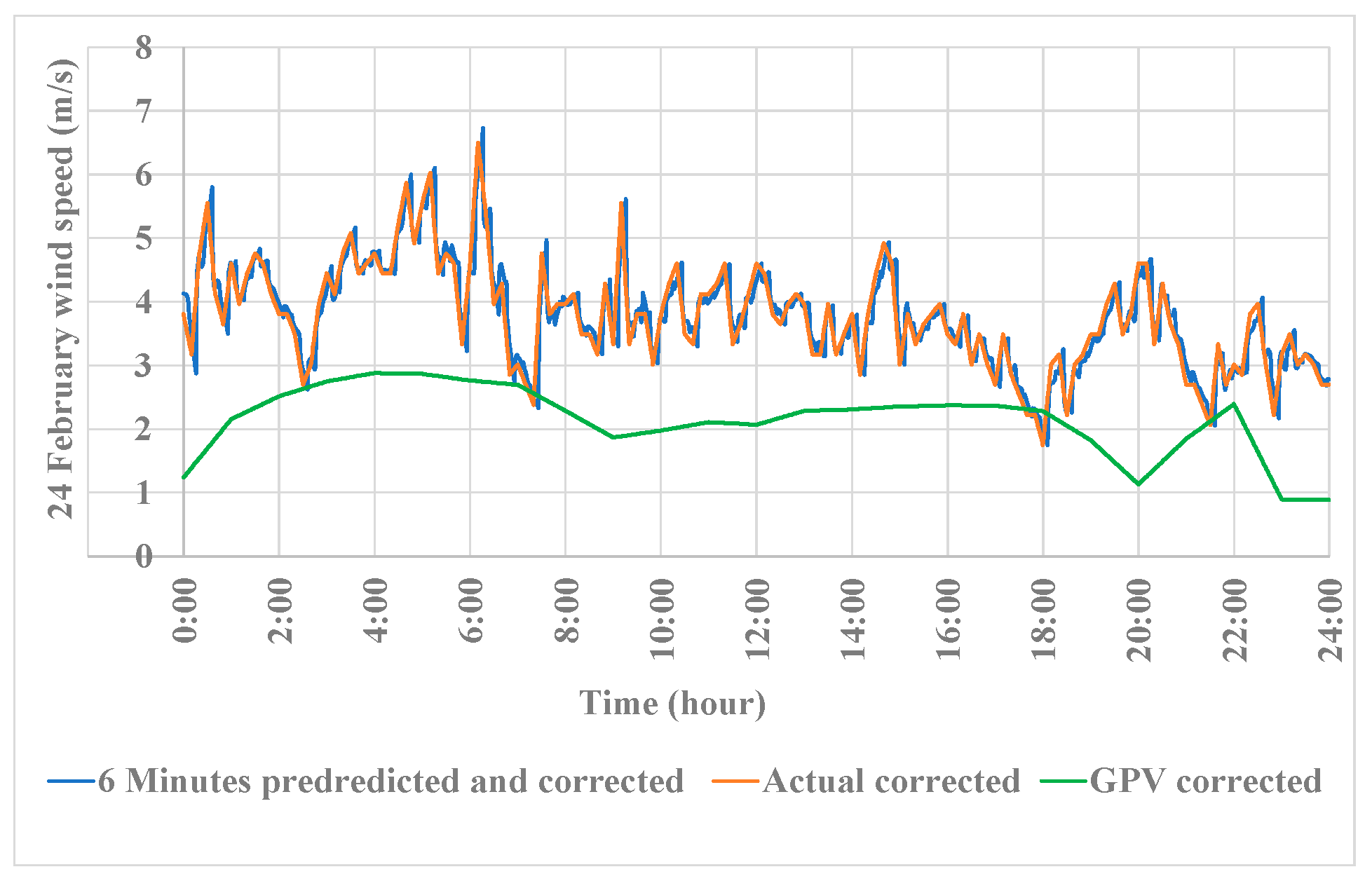

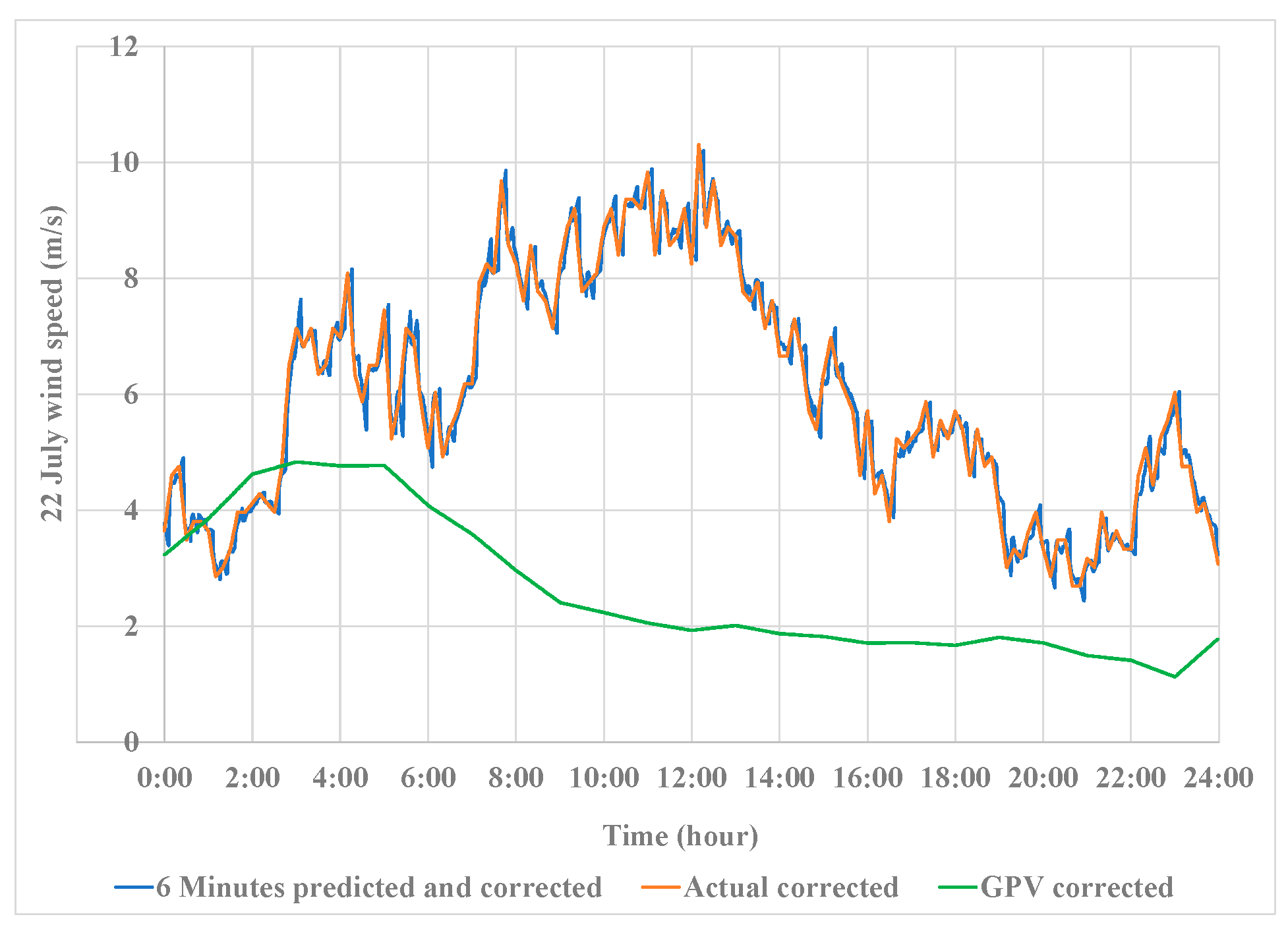

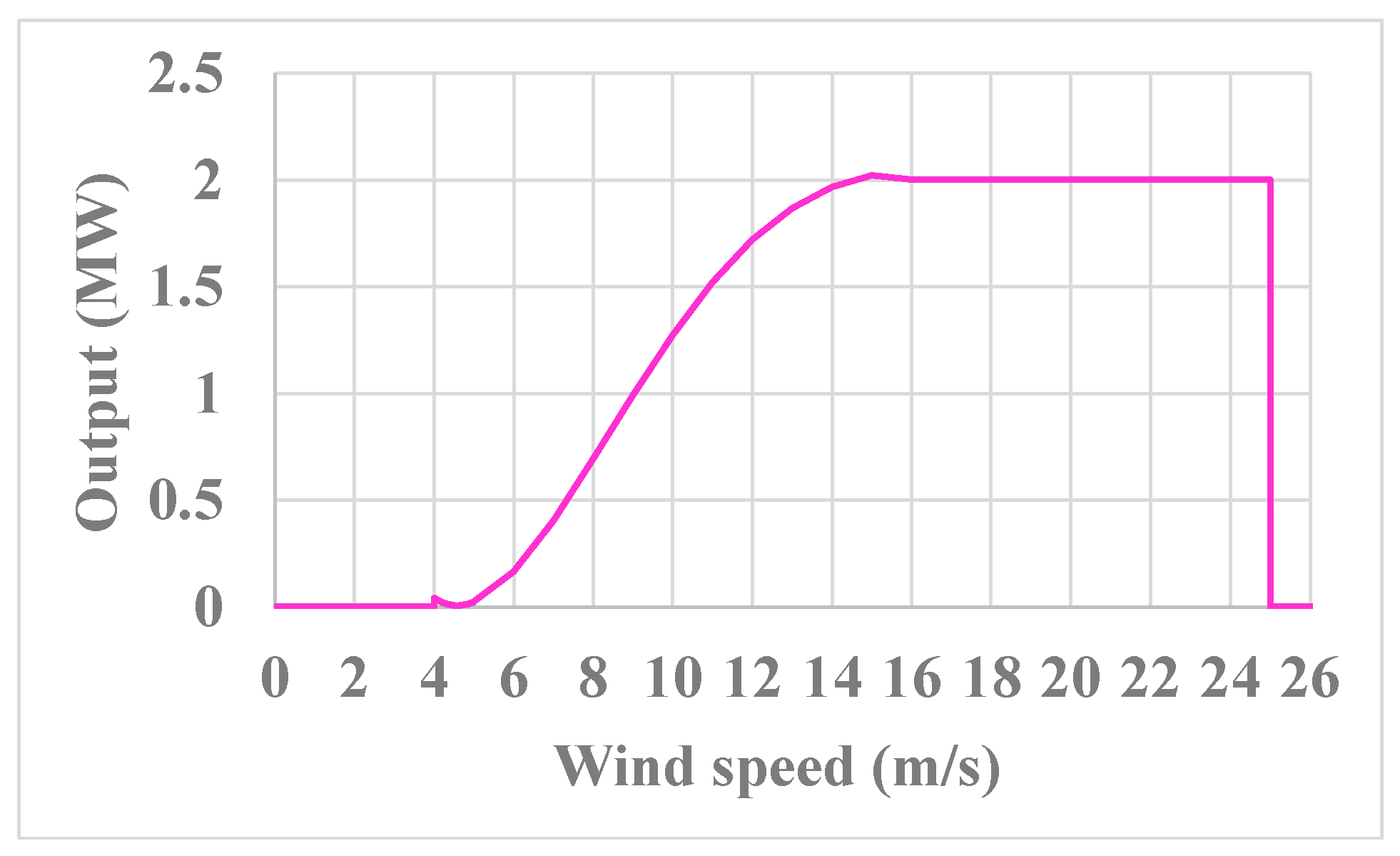

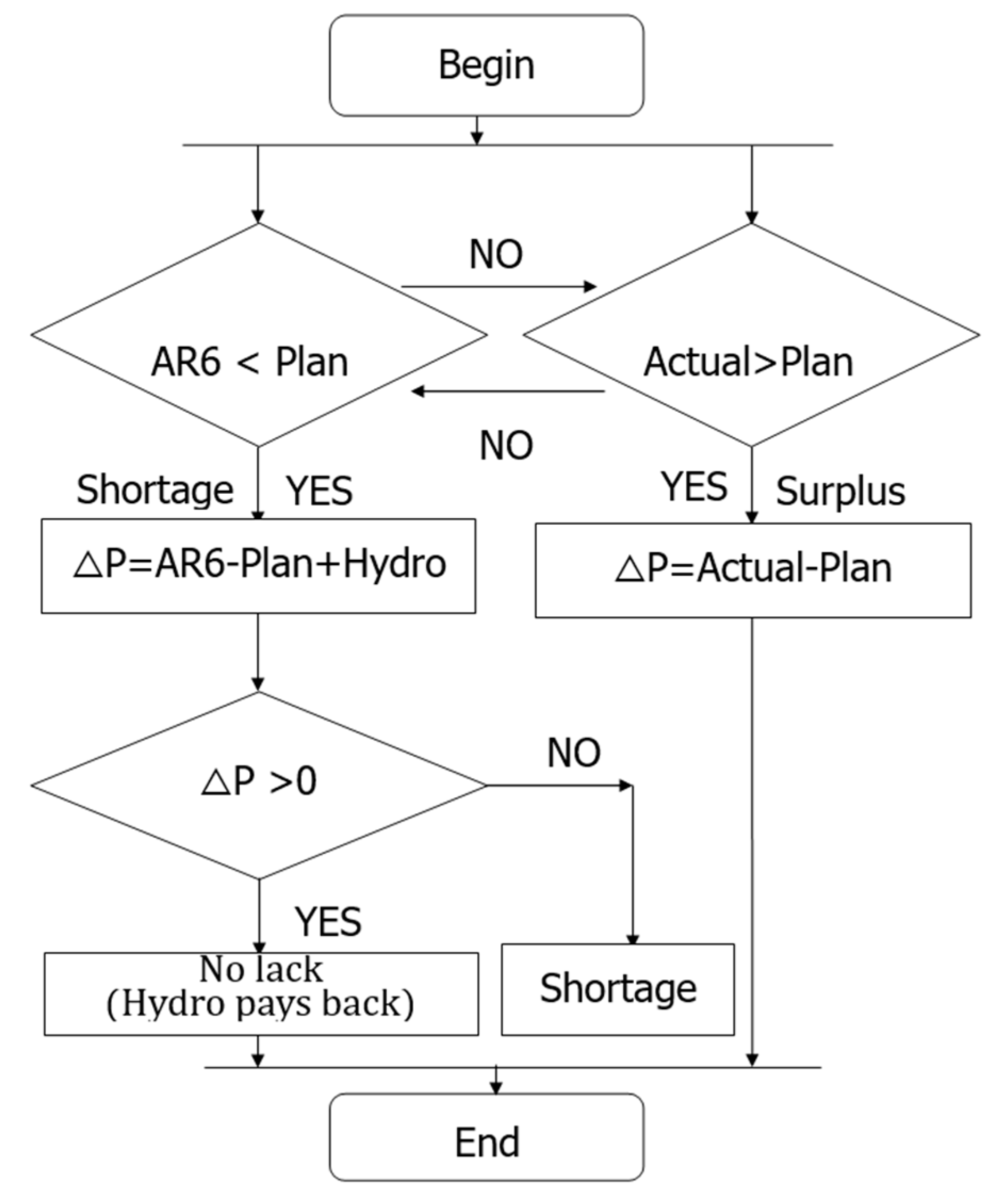

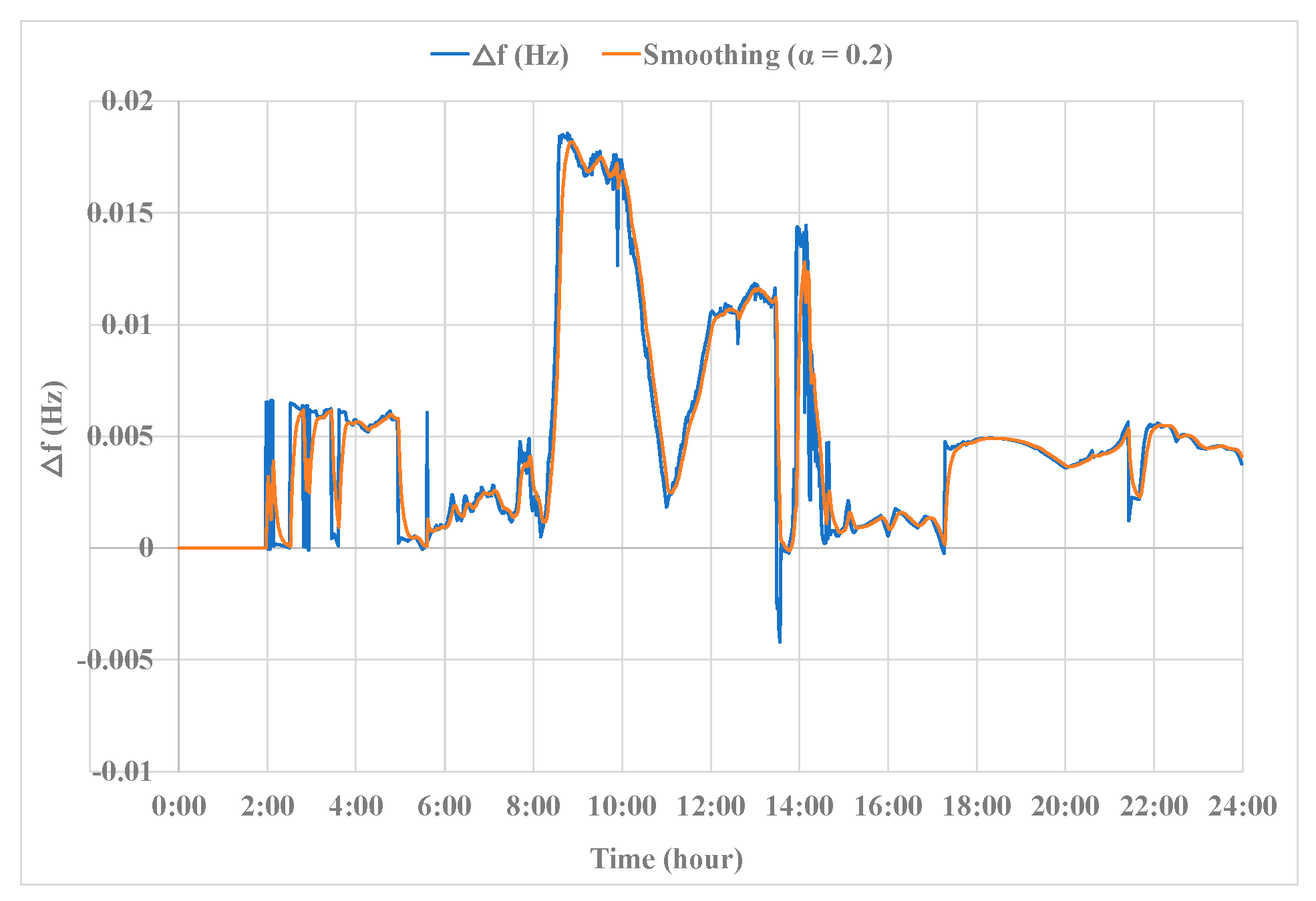

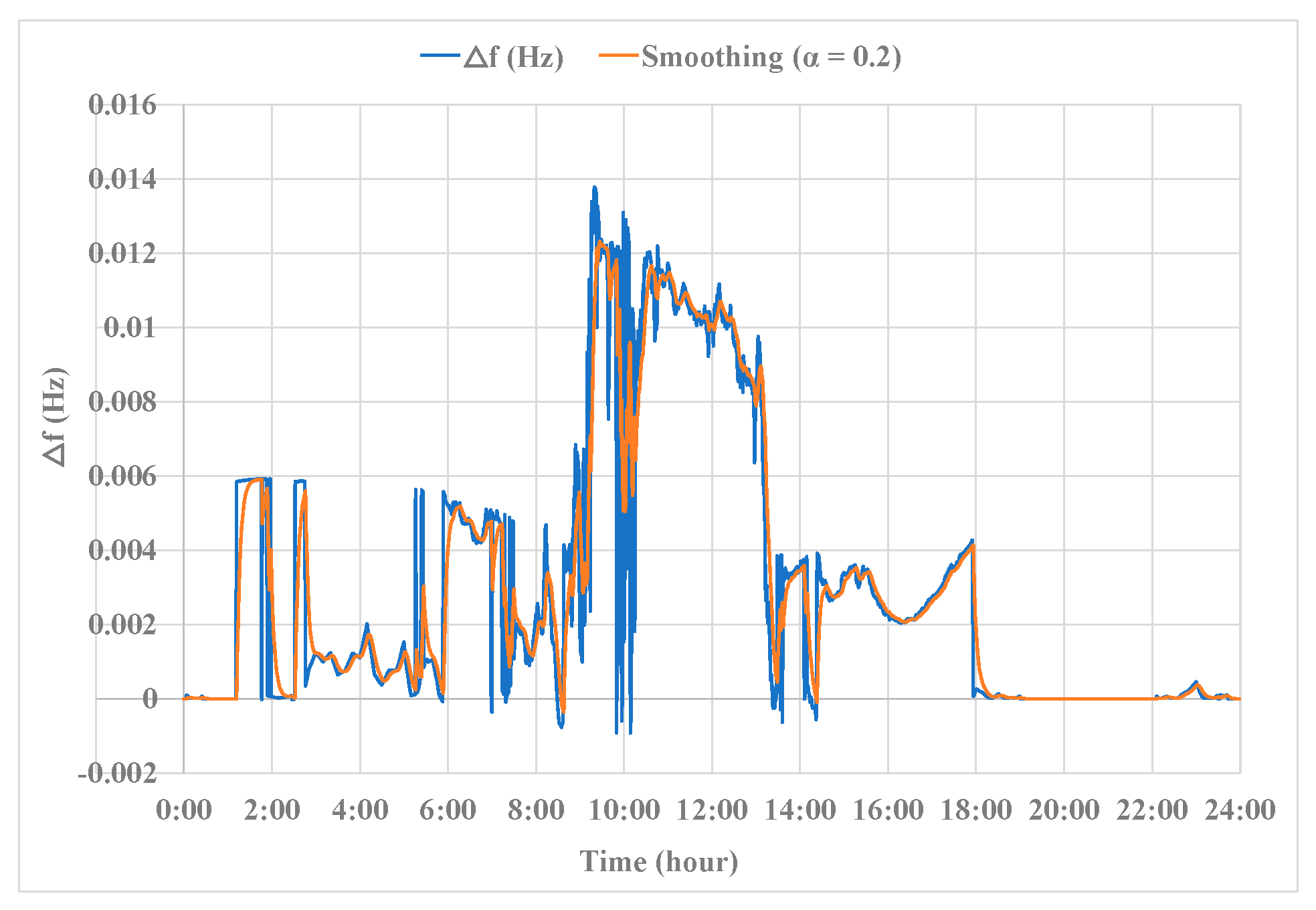

Power system stability (PSS) is the ability of a system to remain in operating equilibrium which is achieved between the electric power generation and consumption. In this paper, we evaluate PSS for a Hybrid power plant (HPP) combining thermal, wind, solar photovoltaic (PV) and, hydro power generations, in Niigata City. A new method to estimate PV power generation, based on NHK cloud distribution forecast (CDF) and land ratio settings, is also introduced. Our objective is to achieve frequency stability (FS) while reducing CO2 emission in the power generation sector. So, PSS is evaluated from the results of the frequency stability (FS) variable. 6-minutes autoregressive wind speed prediction (6ARW) support for wind power (WP). 1-hour GPV wind farm (1HWF) power is computed from the Grid Point Value (GPV) wind speed prediction data. PV power is predicted by autoregressive modelling and CDF. In accordance with the daily power curve and the prediction time, we can support thermal power generation planning. Actual data of wind and solar are measured every 10-minutes and 1-minute, respectively and the hydropower is controlled. The simulation results of the electricity frequency fluctuations are within ±0.2 Hz of the requirements of Tohoku Electric Power Network Co. Inc., for testing and evaluation days. Therefore, the proposed system supplies electricity stably while contributing to CO2 emission reduction.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Objective and Method

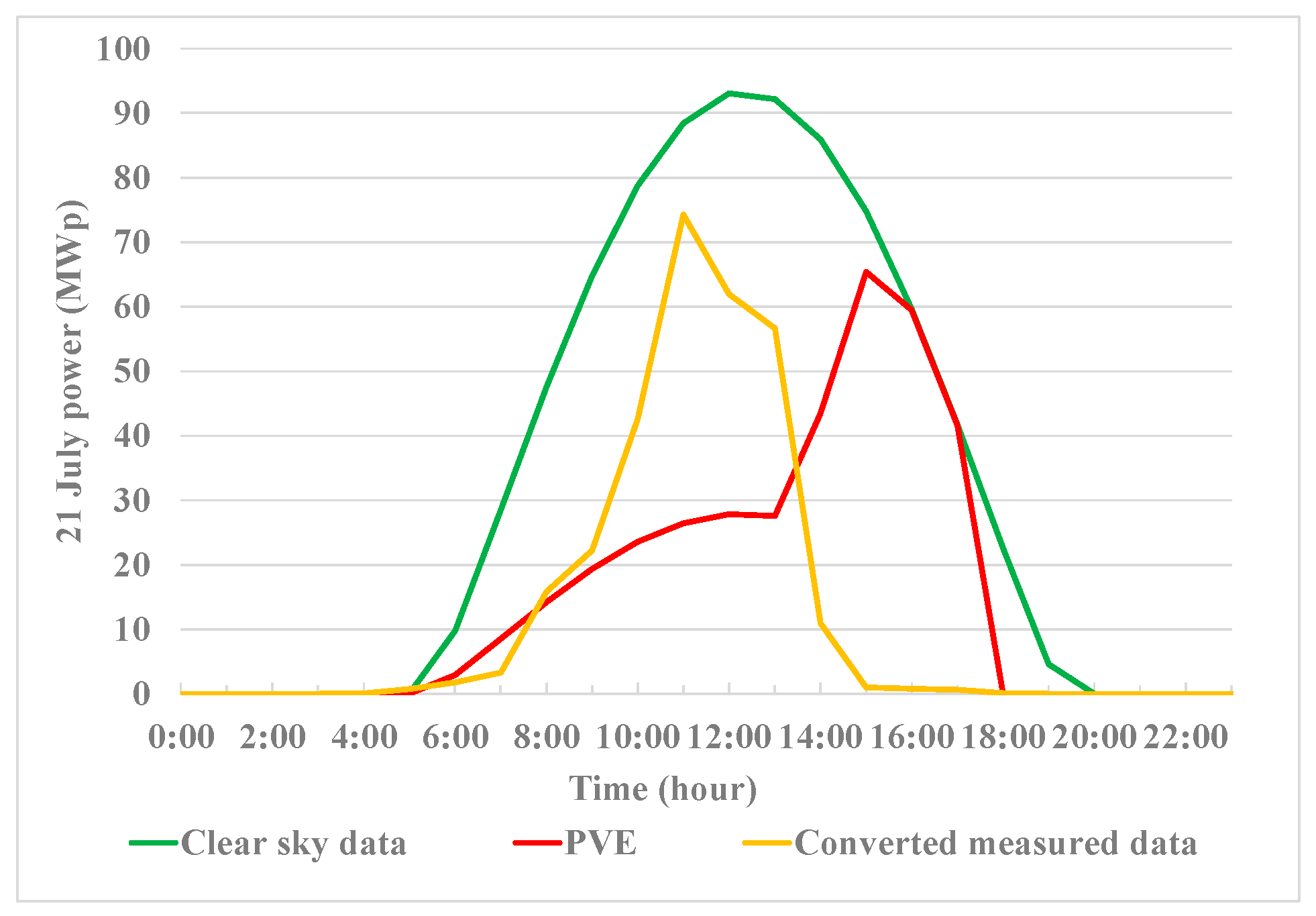

2. Prediction of Photovoltaic Power

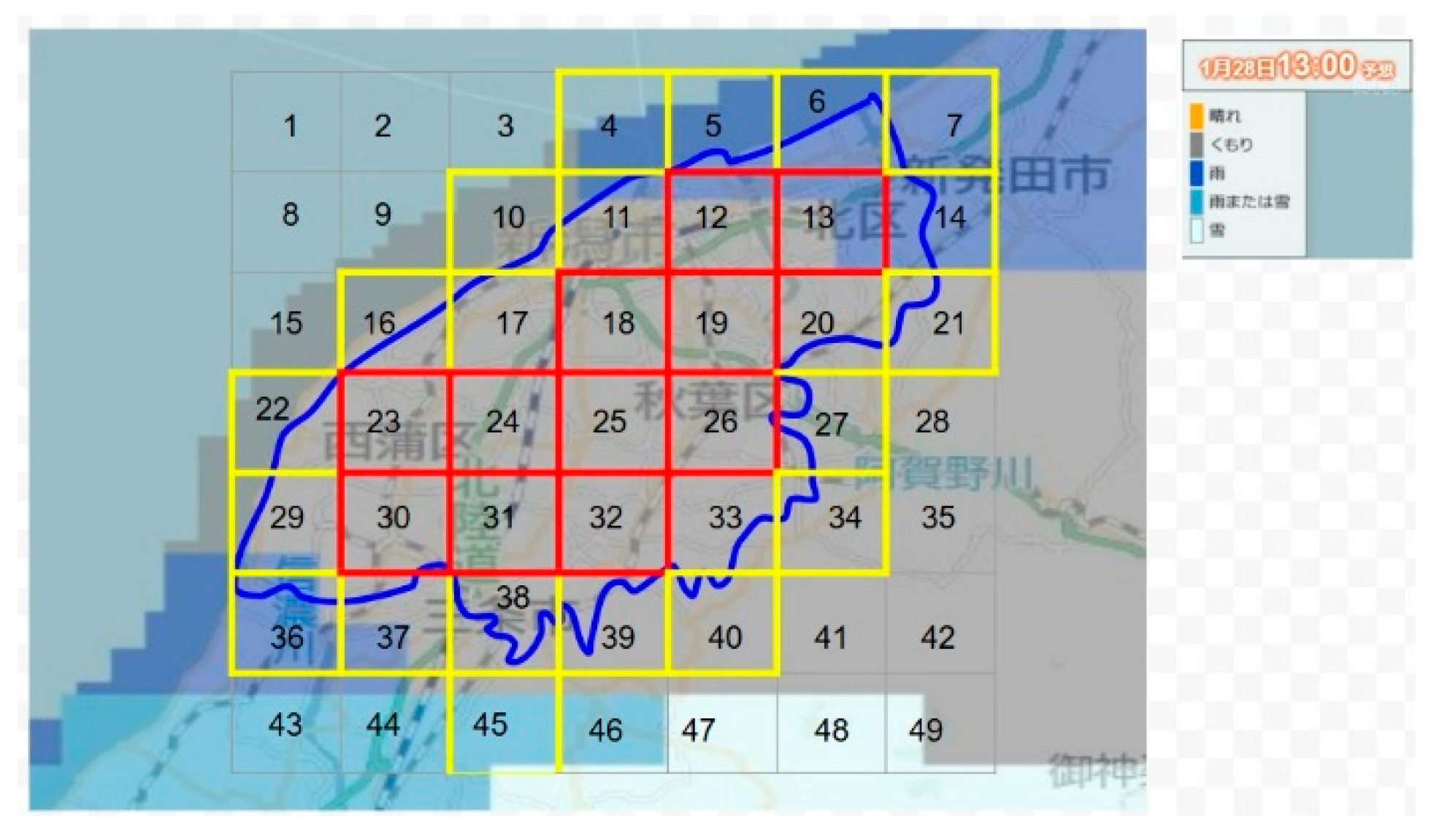

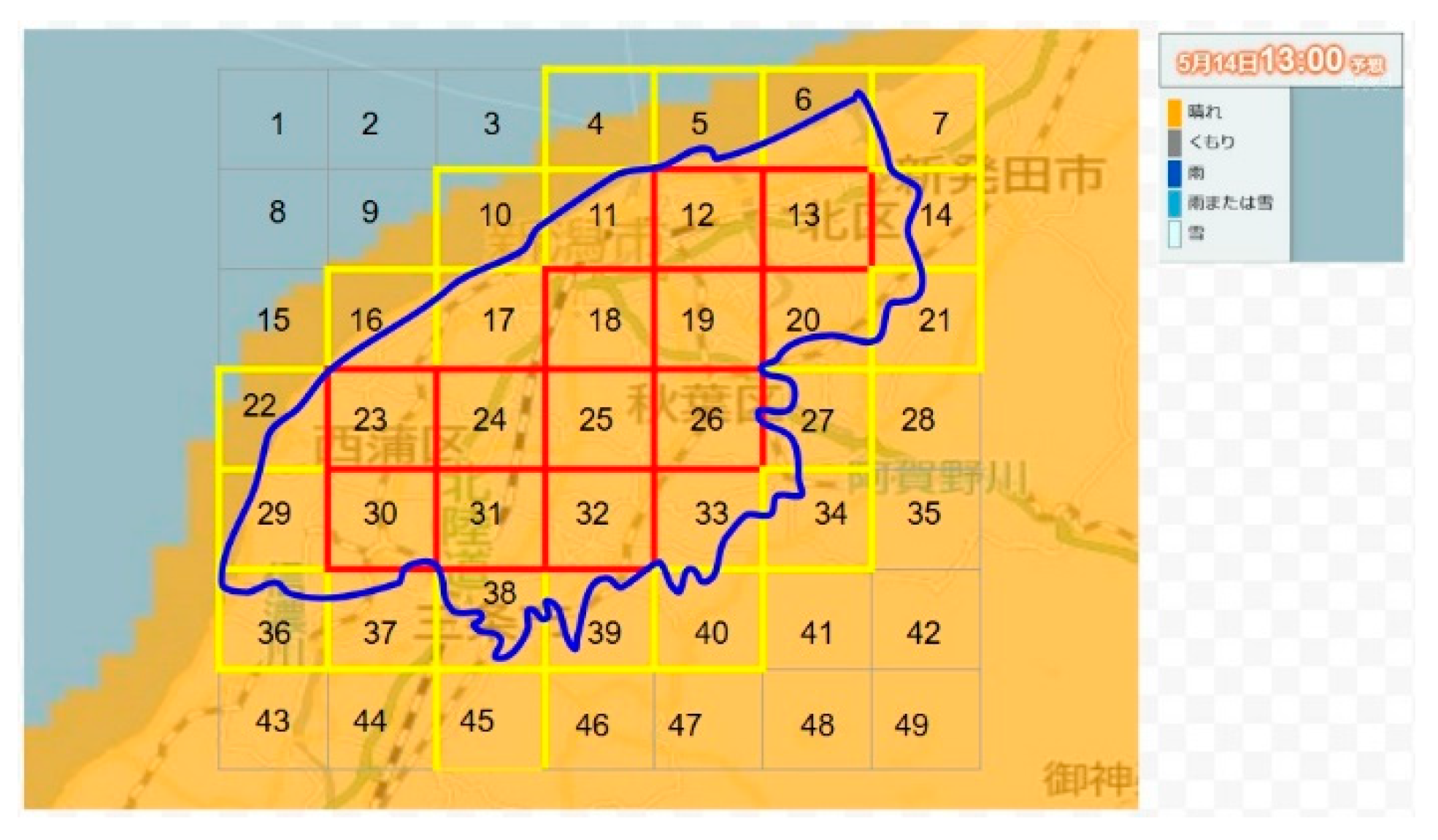

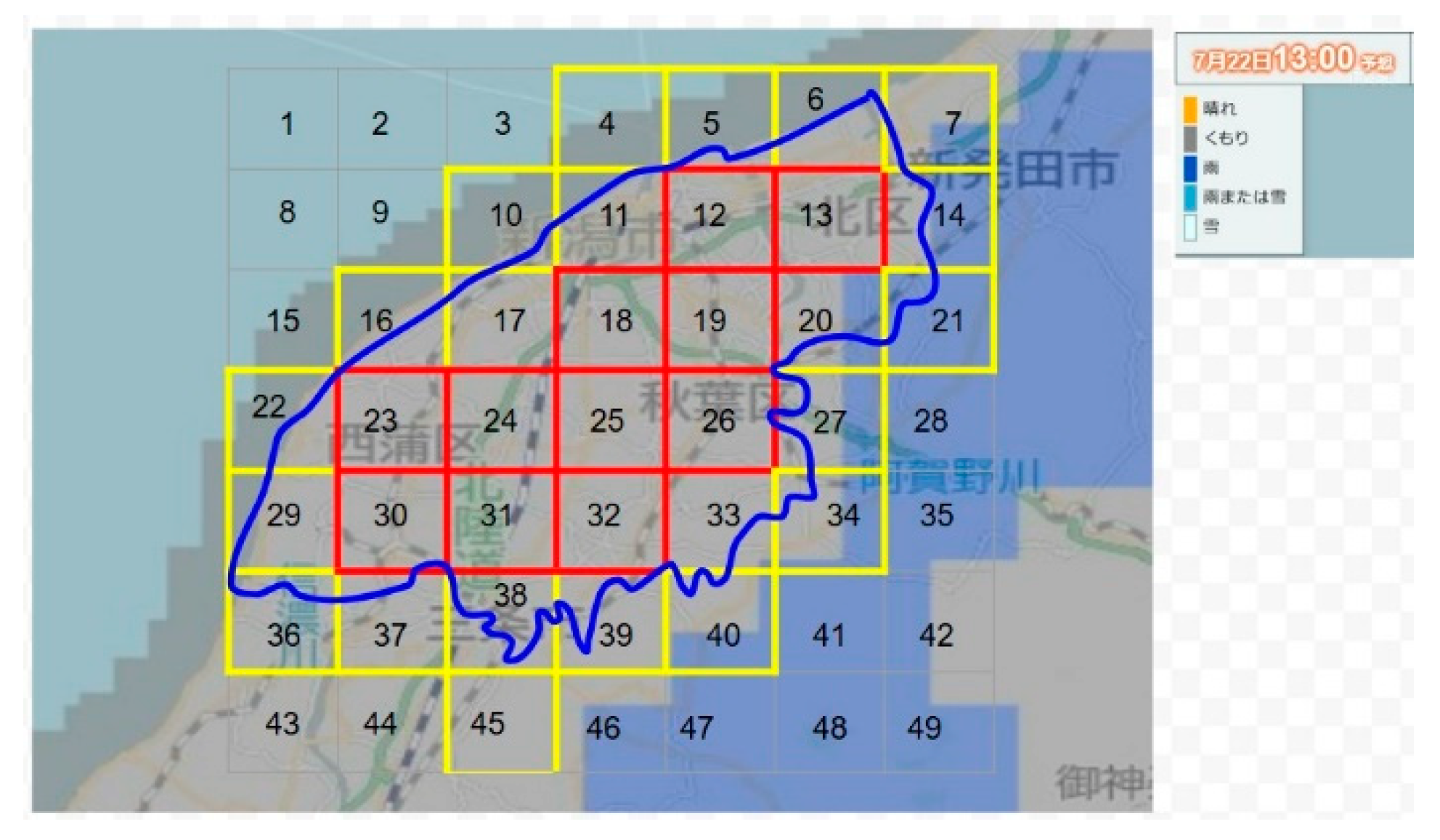

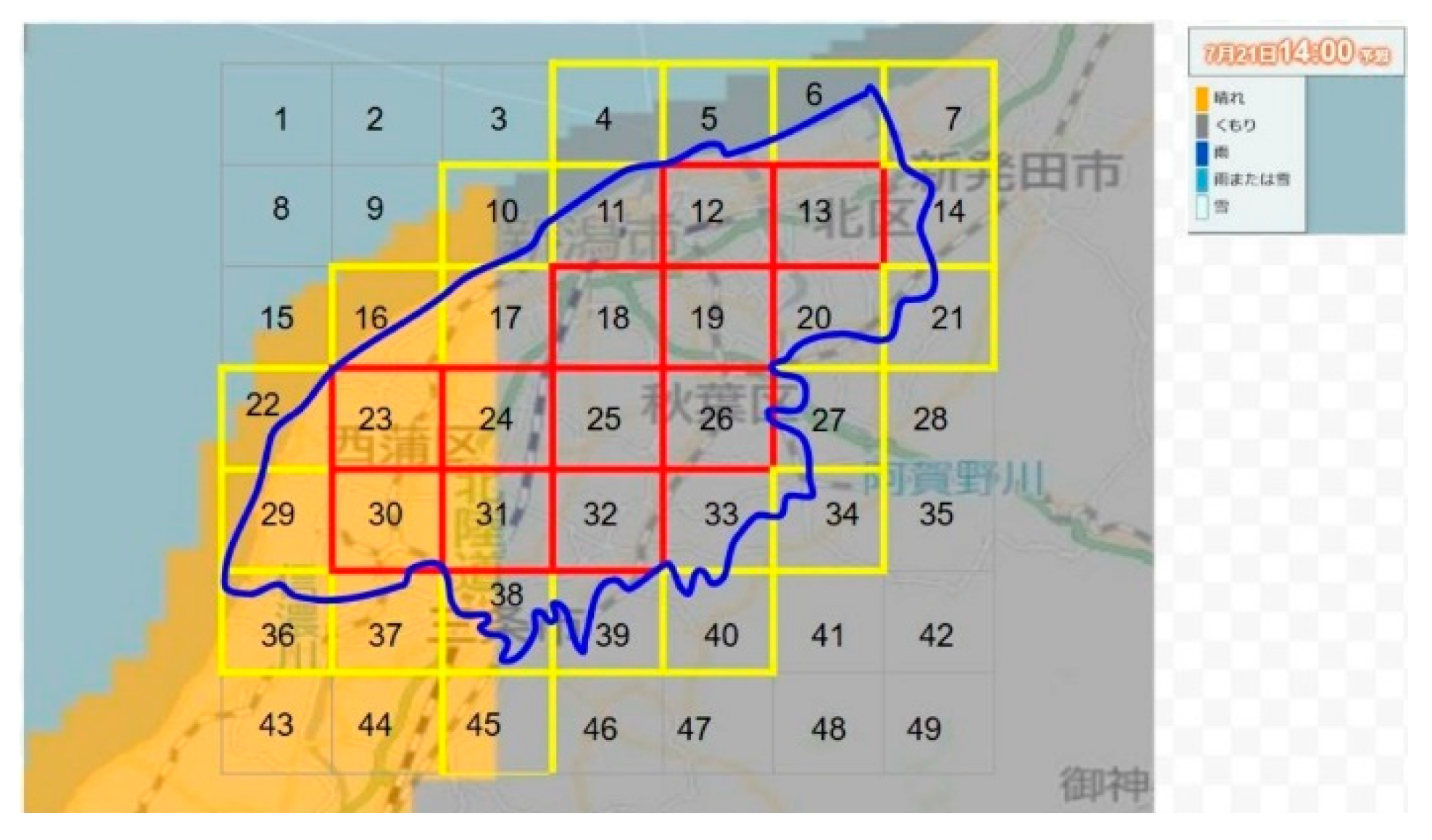

2.1. Mesh Design for PV Power Estimation

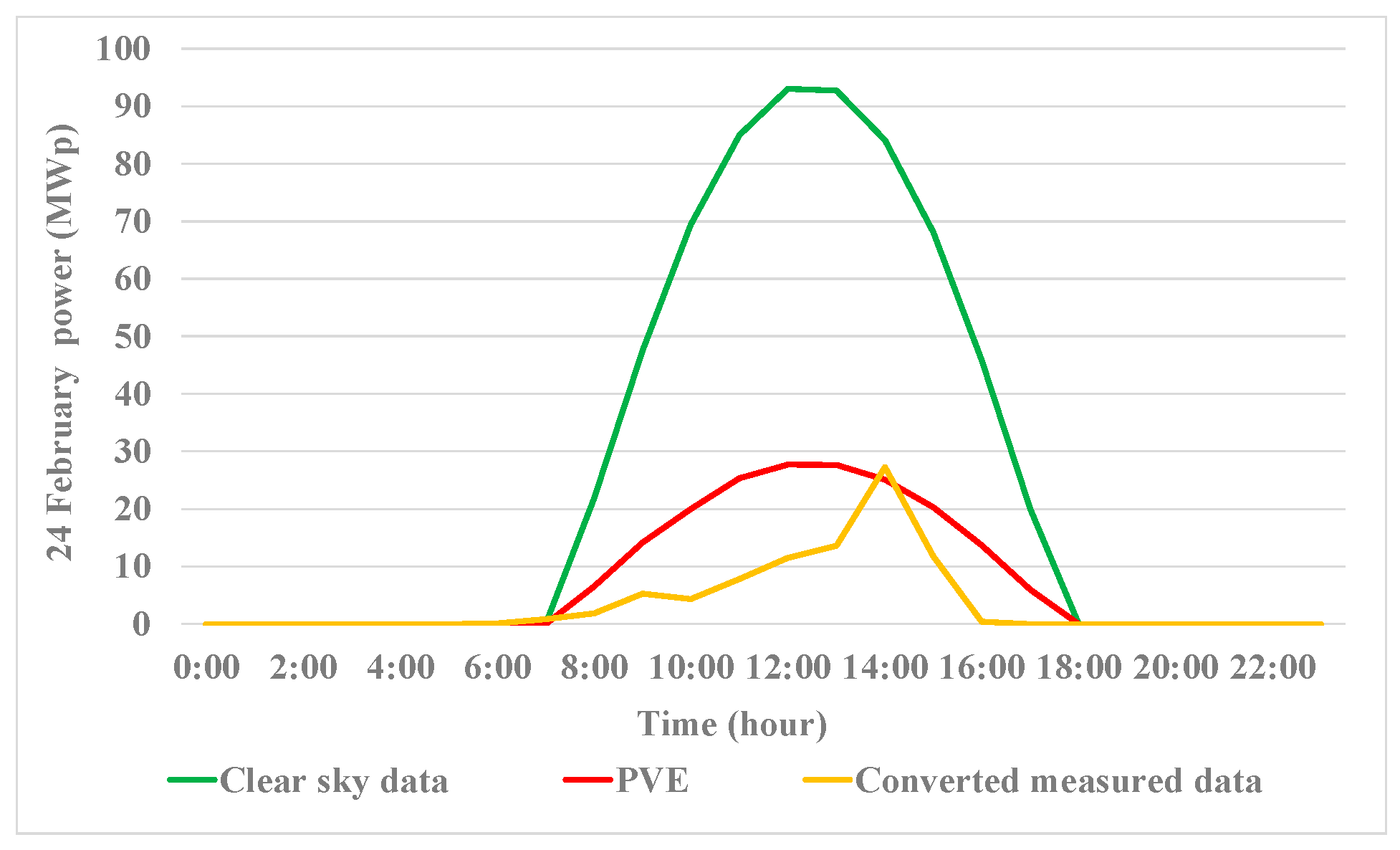

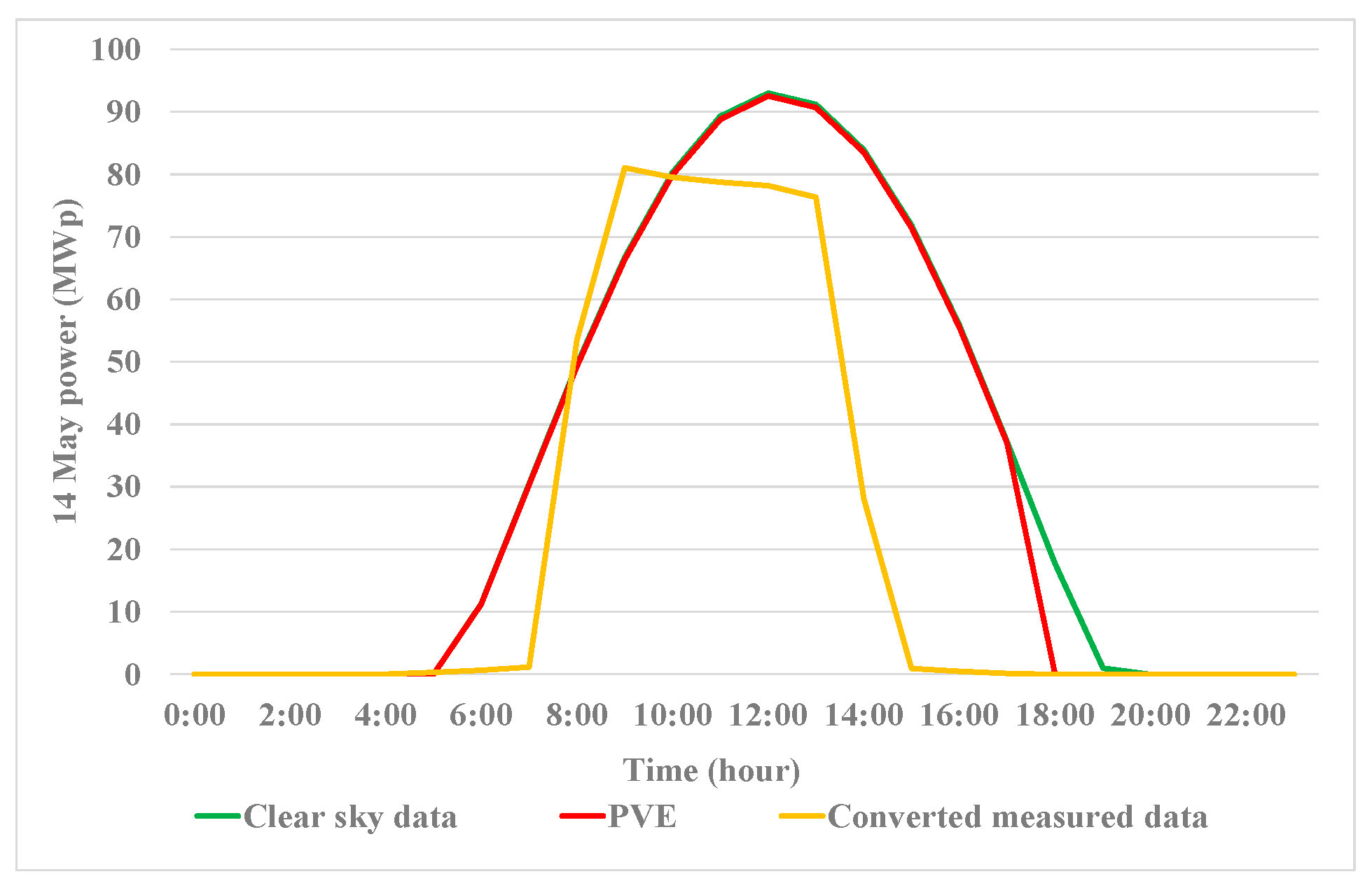

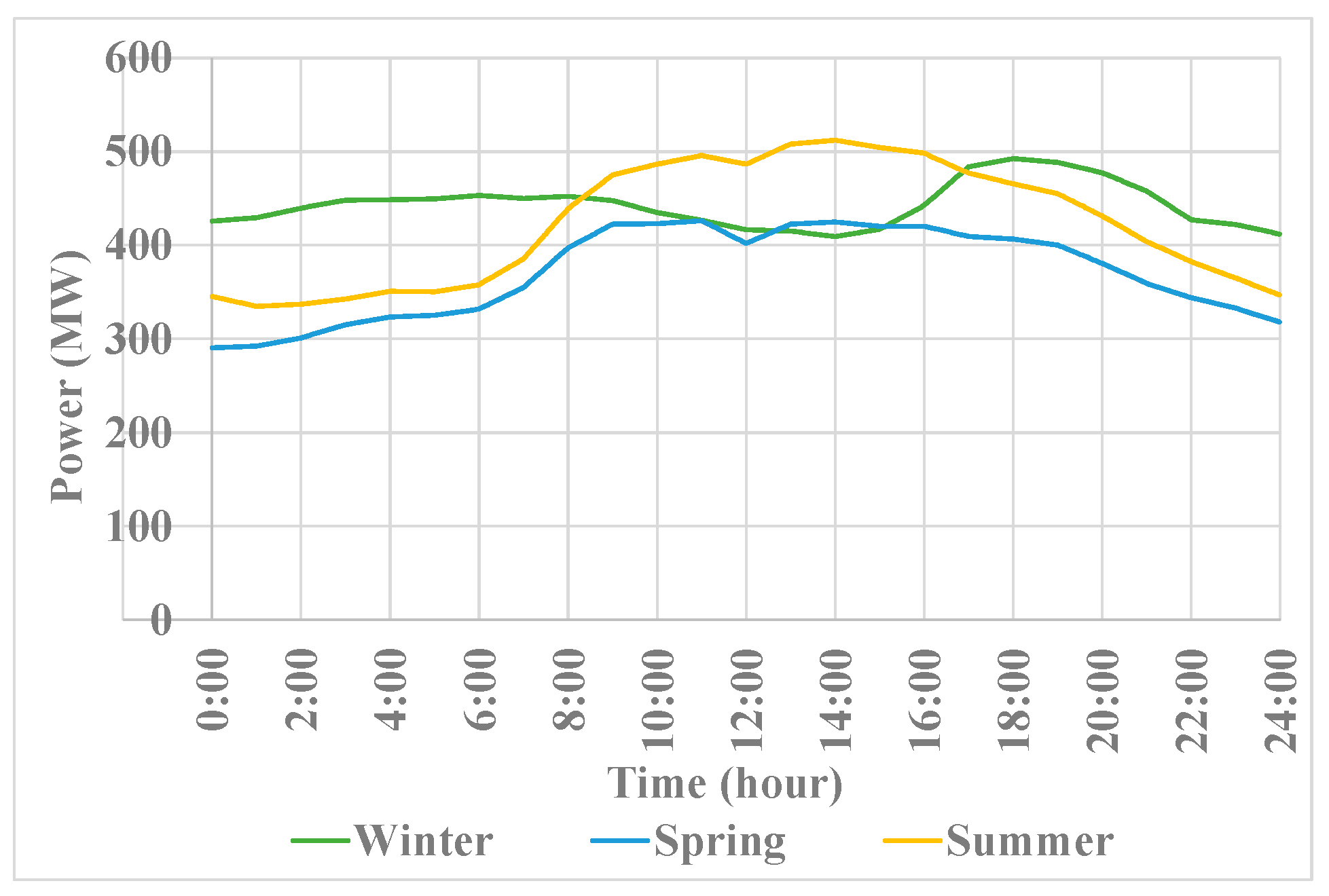

2.2. Niigata City Daily Power Curve

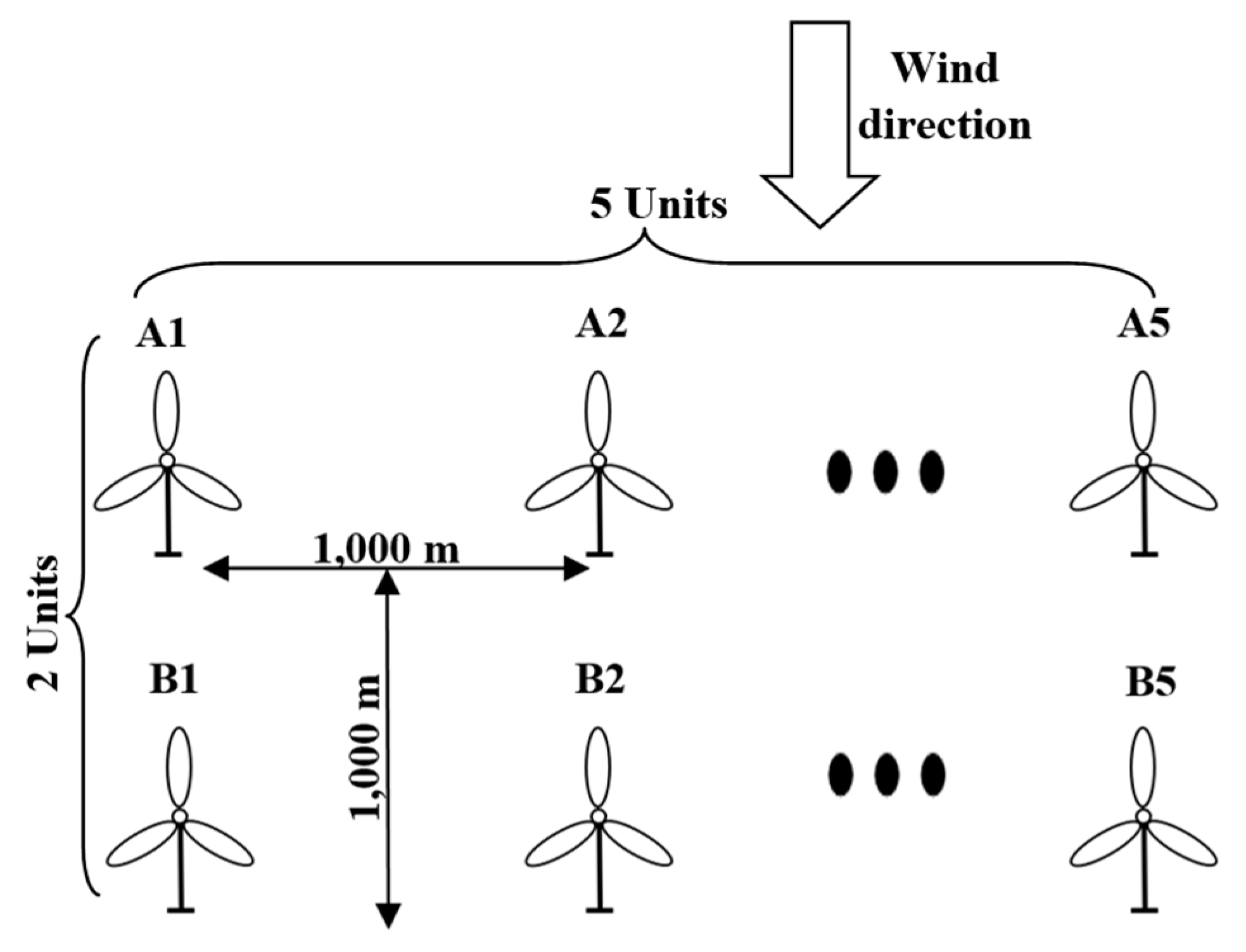

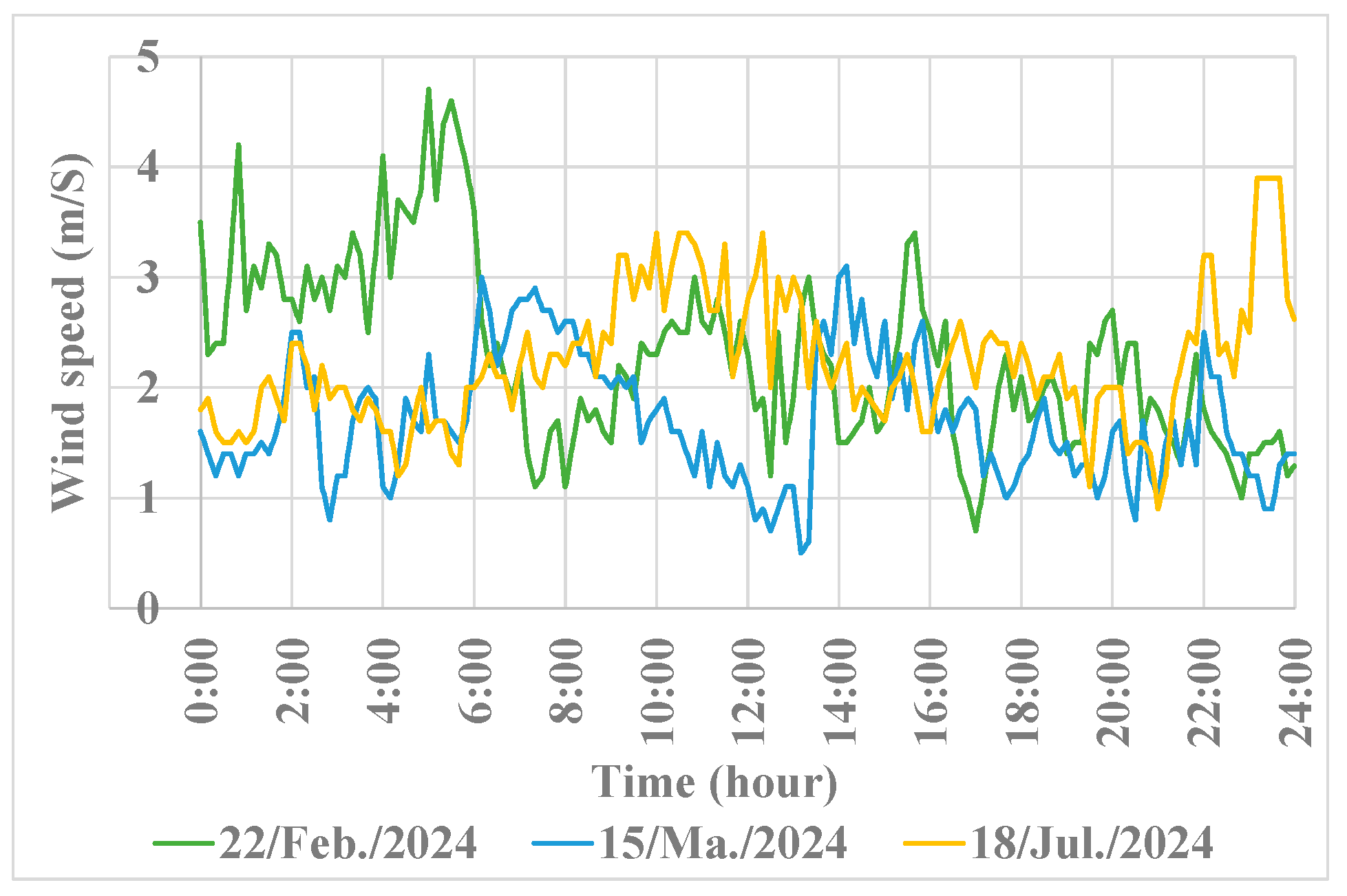

3. Prediction of Wind Power

4. Power Balance Simulation

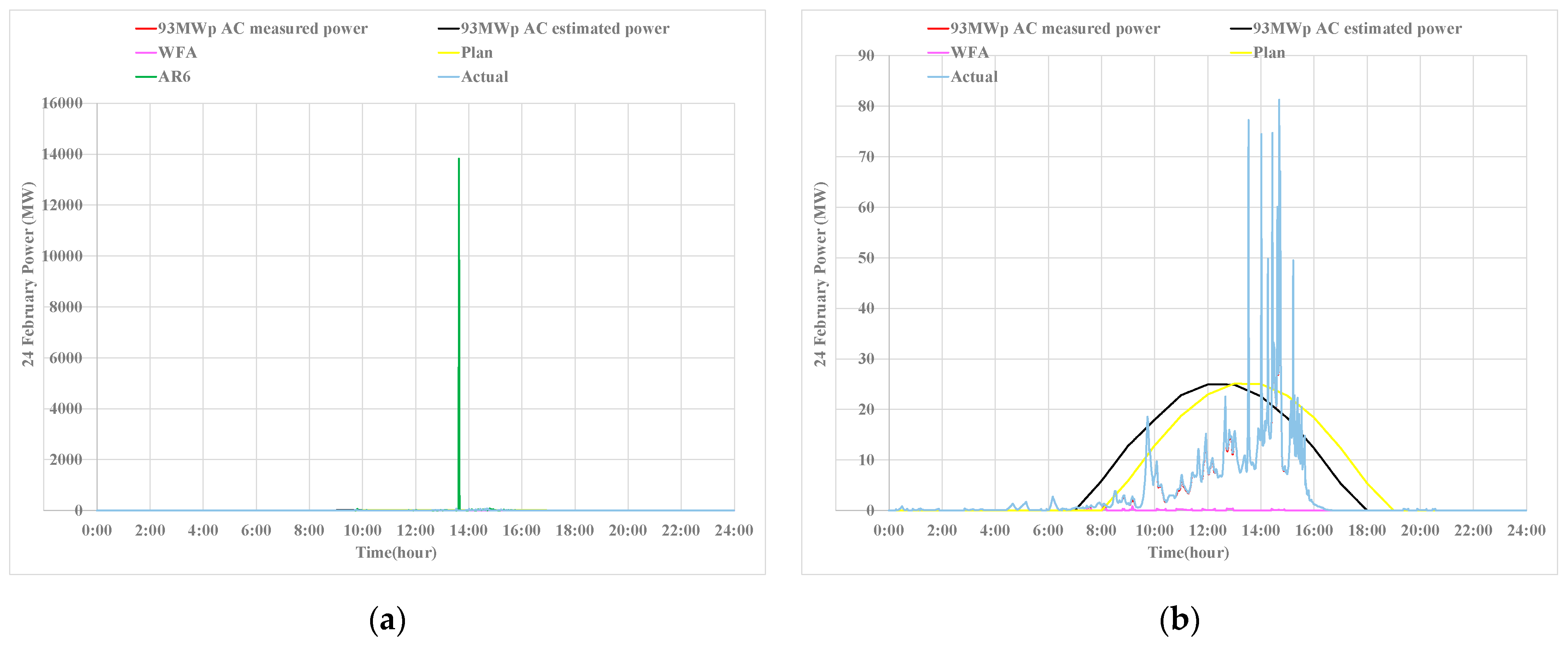

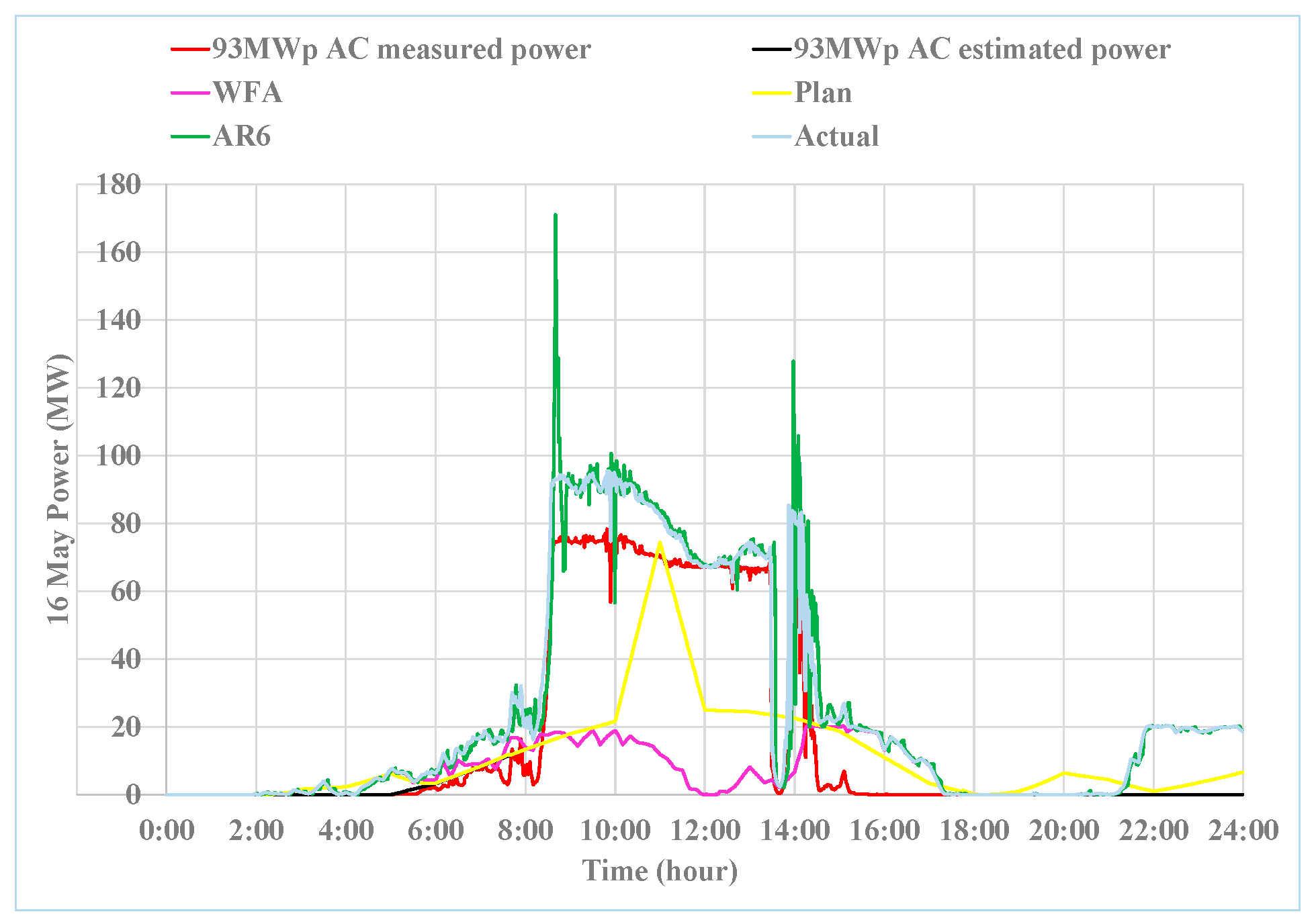

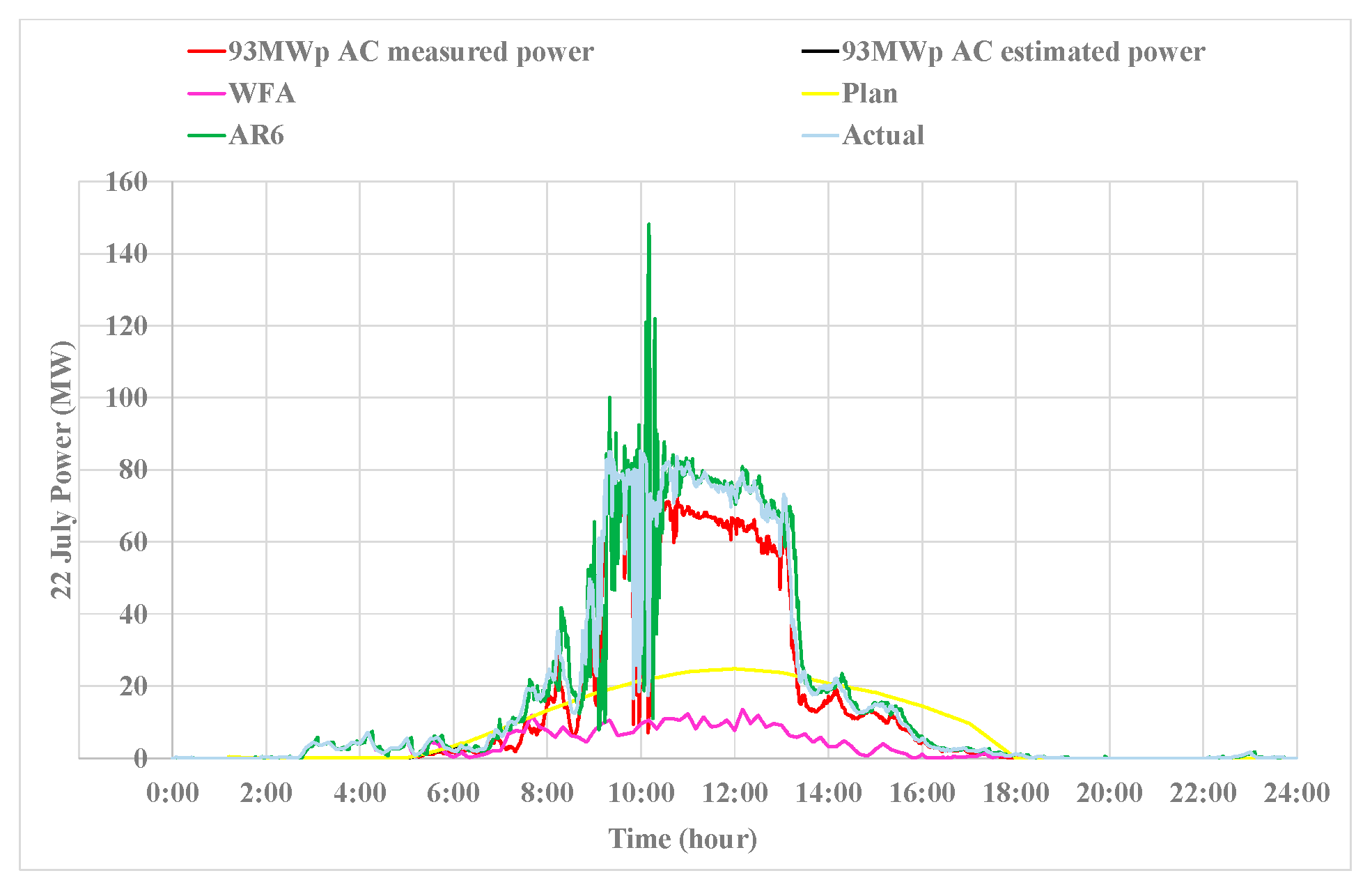

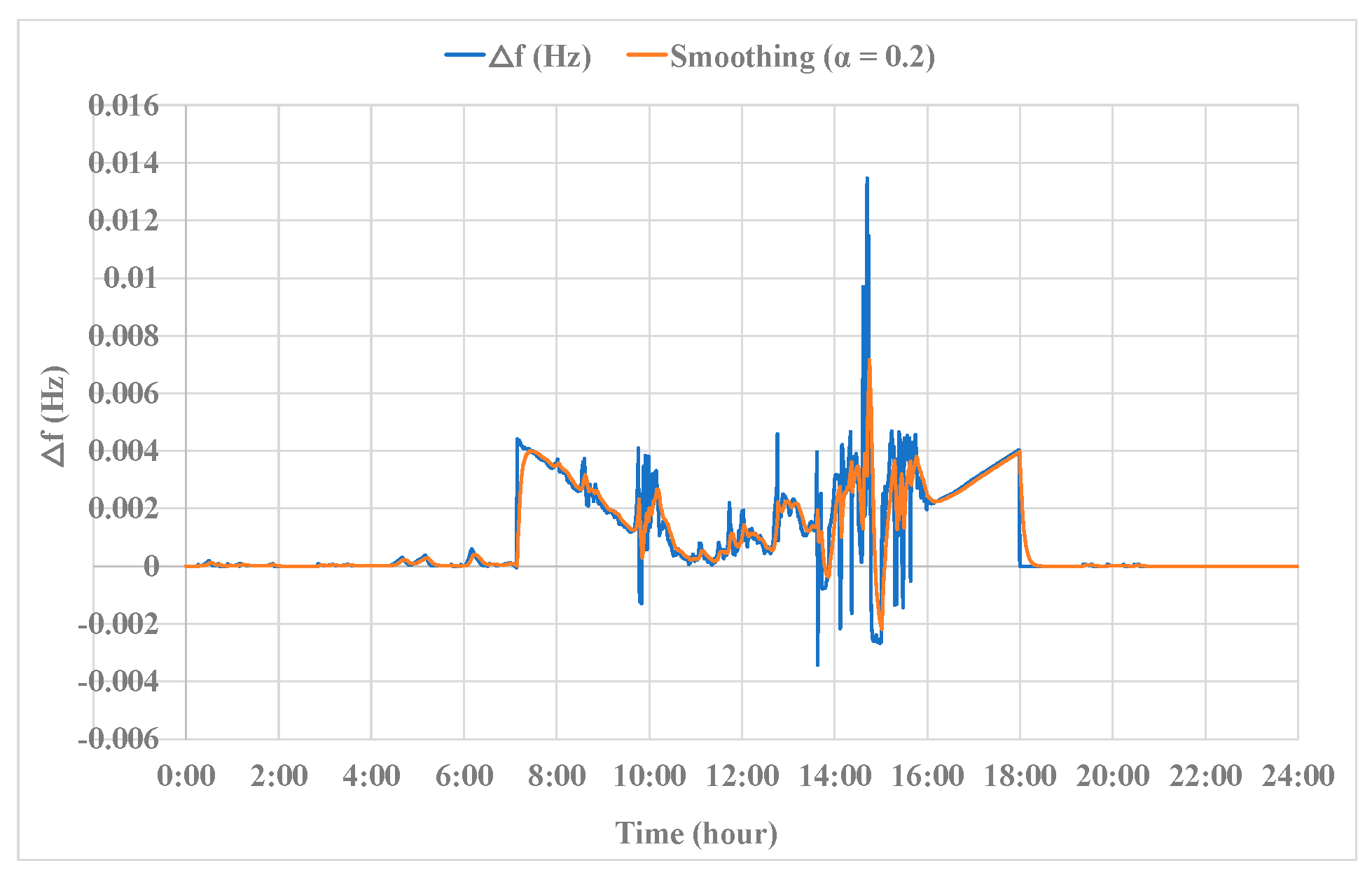

4.1. Simulation Results

4.2. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| PV | Solar photovoltaic; |

| HC | Hydropower capacity; |

| 6ARW | 6-minutes autoregressive wind speed prediction; |

| 6ARP | 6-minutes autoregressive PV power prediction; |

| 1HWF | 1-hour GPV wind farm; |

| 1HP | 1-hour NHK prediction; |

| WFA | Wind farm actual power; |

| PVE | Photovoltaic estimated power; |

| PSS | Power system stability; |

| FS | Frequency stability; |

| HPP | Hybrid power plant; |

| JMA | Japan Meteorological Agency; |

| CDF | NHK cloud distribution forecast; |

| SDG | Sustainable development goals; |

| WP | Wind power; |

| GPV | Grid Point Value; |

| NHK | Japan Broadcasting Corporation; |

| DERs | Distributed energy resources; |

| COP | Conference of the parties; |

| UN | United Nations; |

| VRE | Variable renewable energy. |

References

- International Energy Agency, “The Power of Transformation: Wind, Sun and the Economics of Flexible Power Systems,” IEA (2014) 10 160-179, 2014. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/b6a02e69-35c6-4367-b342-2acf14fc9b77/The_power_of_Transformation.pdf (accessed Dec. 27, 2024).

- V. Chayapathi, S. B, and G. S. Anitha, “Voltage Collapse Mitigation By Reactive Power Compensation At the Load Side,” International Journal of Research in Engineering and Technology, Vol. 02, No. 09, pp. 251–257, 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Sattar, S. Ghosh, Y. J. Isbeih, M. S. El Moursi, A. Al Durra, and T. H. M. El Fouly, “A predictive tool for power system operators to ensure frequency stability for power grids with renewable energy integration,” Applied Energy, Vol. 353, No. PB, p. 122226, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Hatziargyriou et al., “Definition and Classification of Power System Stability - Revisited & Extended,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, Vol. 36, No. 4, pp. 3271–3281, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Shair, H. Li, J. Hu, and X. Xie, “Power system stability issues, classifications and research prospects in the context of high-penetration of renewables and power electronics,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Vol. 145, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. Chandarahasan and E. S. Percis, “The accessible large-scale renewable energy potential and its projected influence on Tamil Nadu’s grid stability,” Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 609–616, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Qin, M. Wang, G. Zhang, and Z. Zhang, “Impact of renewable energy penetration rate on power system frequency stability,” Energy Reports, Vol. 8, pp. 997–1003, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Rahman, W. M. S.M., M. A.K.M., and X. Wang, “Does renewable energy proactively contribute to mitigating carbon emissions in major fossil fuels consuming countries?,” Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 452, pp. 1–16, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Yuping, S. Shenghu, A. K. Tiwari, S. Khan, and X. Zhao, “Impacts of renewable energy on climate risk: A global perspective for energy transition in a climate adaptation framework,” Applied Energy, Vol. 362, pp. 1–13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- HivePower, “Grid Stability Issues With Renewable Energy Sources: How They Can Be Solved,” https://www.hivepower.tech/blog/grid-stability-issues-with-renewable-energy-how-they-can-be-solved (accessed Dec. 06, 2024).

- International Energy Agency, “Net Zero by 2050 A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector.” https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/deebef5d-0c34-4539-9d0c-10b13d840027/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector_CORR.pdf (accessed Nov. 15, 2024).

- M. Arbabzadeh, R. Sioshansi, J. X. Johnson, and G. A. Keoleian, “The role of energy storage in deep decarbonization of electricity production,” Nature Communications, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 1–11, 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. P. Wei H, Xin L, “TYPES OF CO2 EMISSION REDUCTION TECHNOLOGIES AND FUTURE DEVELOPMENT TRENDS,” Engineering for Rural Development, Vol. 25, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Kosugi, K. Tokimatsu, and H. Yoshida, “Evaluating new CO2 reduction technologies in Japan up to 2030,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 72, No. 7. pp. 779–797, 2005. [CrossRef]

- KIZUNA, “Climate Transition Bonds Show Japan’s Commitment to Carbon Neutrality,” https://www.japan.go.jp/kizuna/2024/09/climate_transition_bonds.html (accessed Dec. 12, 2024).

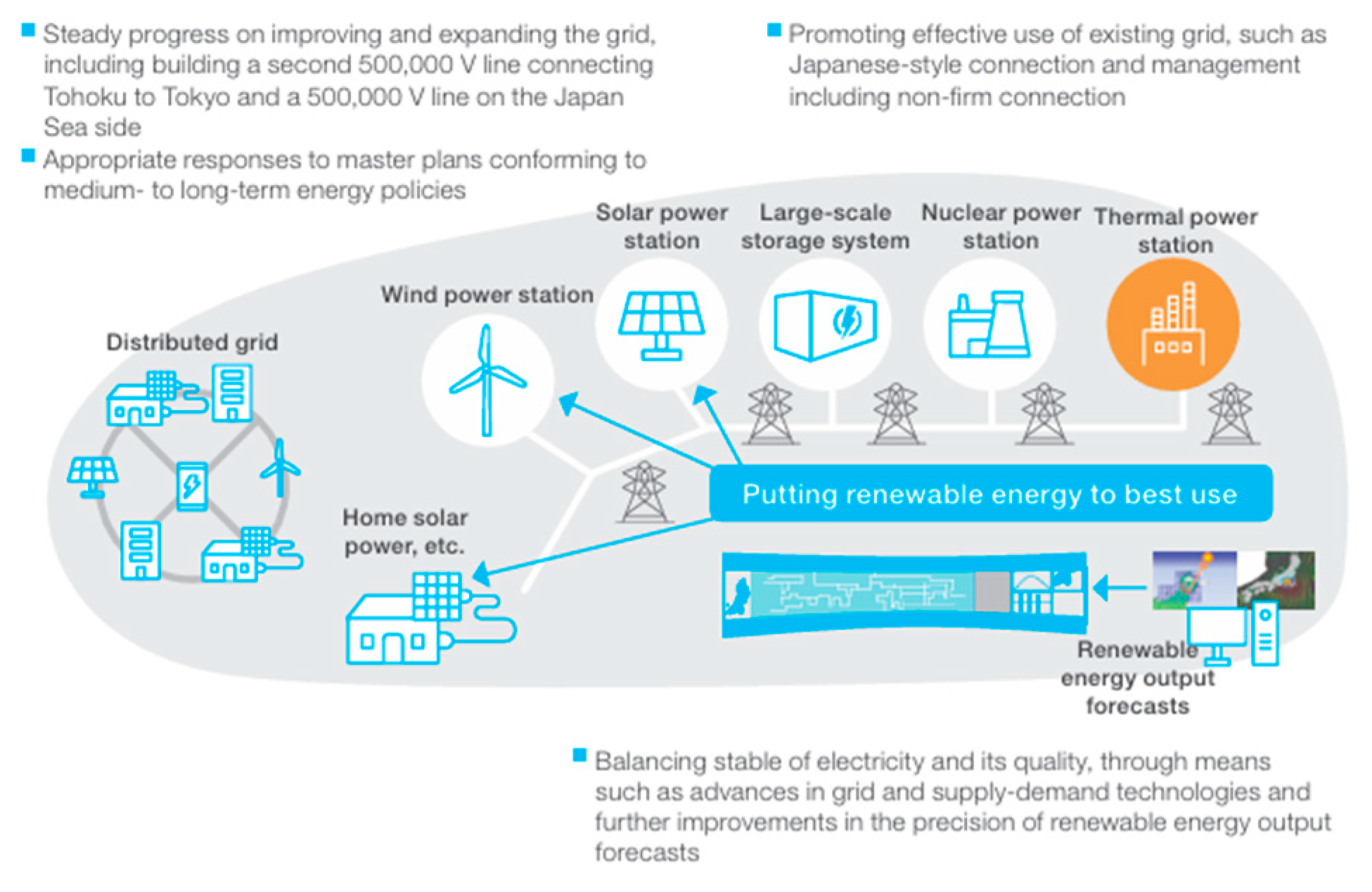

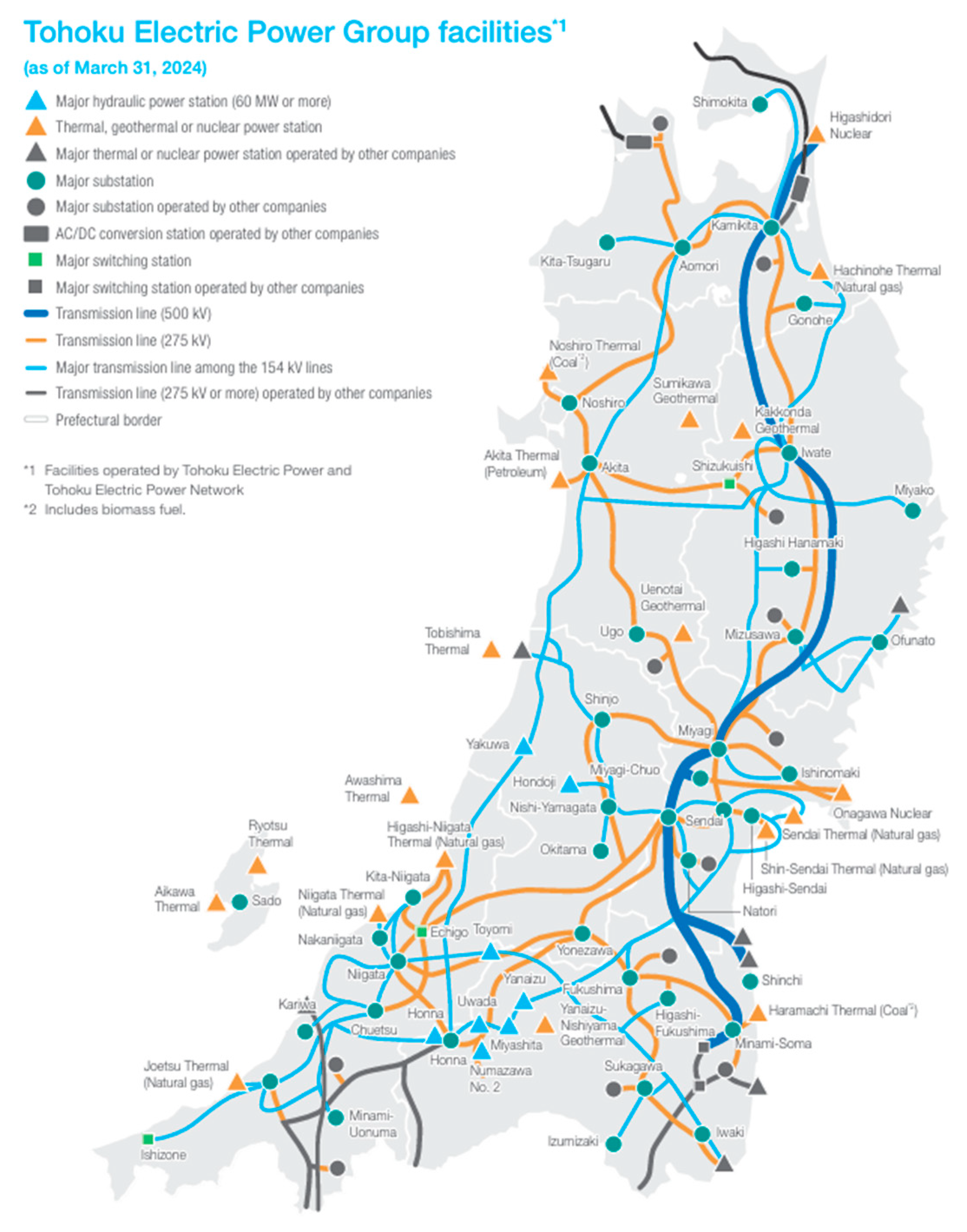

- Tohoku Electric Power Group, “Tohoku Electric Power Group Sustainability report 2023,” https://www.tohoku-epco.co.jp/ir/report/integrated_report/pdf/tohoku_sustainability2023en.pdf#page=15 (accessed Dec. 29, 2024).

- Tohoku Electric Power Network Co., “Feed-in Tariff Scheme for Renewable Energy.” https://nw.tohoku-epco.co.jp/consignment/renew/pdf/saisei.pdf (accessed Dec. 26, 2024), (in Japanese).

- E. Grant and C. E. Clark, “Hybrid power plants: An effective way ofdecreasing loss-of-load expectation,” Energy, Vol. 307, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Kim, James Hyungkwan Millstein, Dev Wiser, Ryan Mulvaney-Kemp, “Renewable-battery hybrid power plants in congested electricity markets: Implications for plant configuration,” Renewable Energy, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Denholm, J. Nunemaker, P. Gagnon, and W. Cole, “The potential for battery energy storage to provide peaking capacity in the United States,” Renewable Energy, Vol. 151, pp. 1269-1277, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Denholm and T. Mai, “Timescales of energy storage needed for reducing renewable energy curtailment,” Renewable Energy, Vol. 130, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Aziz, A. T. Oo, and A. Stojcevski, “Analysis of frequency sensitive wind plant penetration effect on load frequency control of hybrid power system,” Electrical Power and Energy Systems, Vol. 99, 2018. [CrossRef]

- W. Ji et al., “Applications offlywheel energy storage system on load frequency regulation combined with various power generations: A review,” Renewable Energy, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Kennedy, D. Bertram, and C. J. White, “Reviewing the UK’s exploited hydropower resource (onshore and offshore),” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Sample, N. Duncan, M. Ferguson, and S. Cooksley, “Scotland’s hydropower: Current capacity, future potential and the possible impacts of climate change,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Sarmiento-Vintimilla, D. M. Larruskain, E. Torres, and O. Abarrategi, “Assessment of the operational flexibility of virtual power plants to facilitate the integration of distributed energy resources and decision-making under uncertainty,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Karapici et al., “Opportunities of hidden hydropower technologies towards the energy transition,” Energy Reports, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhou, E. Doroodchi, and B. Moghtaderi, “Figure of Merit Analysis of a Hybrid Solar-Geothermal Power Plant,” Engineering, Vol. 5, No. 1, doi: doi:10.4236/eng.2013.51b005.

- TOHOKU ELECTRIC POWER GROUP, “Tohoku Electric Power Group Integrated Report 2024,” 2024. https://www.tohoku-epco.co.jp/ir/report/integrated_report/pdf/tohoku_integratedreport2024en.pdf (accessed Dec. 29, 2024).

- T. D. TCHOKOMANI MOUKAM, A. SUGAWARA, I. L. SHAWAPALA, Y. BELLO and Y. LI, Stabilization of Electricity by Mesh Method and Combination of Renewable Energy System, The International Council on Electrical Engineering Conference2024, 0-060,June 2024 Kitakyushu, Japan.

- “JMA/GPV Weather Maps,” 2024. https://www.basso-continuo.com/WeatherGPV/index_e.htm (accessed Dec. 30, 2024).

- Agora Energiewende, “Integrating renewables into the Japanese power grid by 2030,” 148/1-S-2019/EN. https://www.renewable-ei.org/pdfdownload/activities/REI_Agora_Japan_grid_study_FullReport_EN_WEB.pdf (accessed Jan. 30, 2025).

- NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation), “NHK News web,” 2024. https://www.nhk.or.jp/kishou-saigai/city/status/15100001510700/ (accessed Dec. 30, 2024).

- Vocabulary.com, “Mesh,” 2024. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/mesh (accessed Dec. 30, 2024).

- “Population of Cities in Japan 2024,” 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/japan%0A%0A (accessed Oct. 25, 2024).

- “Introduction to clouds.” https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/sky-watcher-cloud-chart-noaa-nasa-english-version.pdf (accessed Feb. 09, 2024).

- X. Zhu, J. Yan, and N. Lu, “A Graphical Performance-Based Energy Storage Capacity Sizing Method for High Solar Penetration Residential Feeders,” IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. P. S. U. Jeffrey Brownson, College of Earth and Mineral Sciences, “Clear Sky Model and Measured Irradiance Data,” 2023. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/eme810/node/698 (accessed Mar. 20, 2024).

- S. Sahebzadeh, A. Rezaeiha, and H. Montazeri, “Vertical-axis wind-turbine farm design: Impact ofrotor setting and relative arrangement on aerodynamic performance ofdouble rotor arrays,” Energy Reports, Vol. 8, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vestas, “Vestas V80-2.0 MW, Facts and figures,” 2011. https://www.ledsjovind.se/tolvmanstegen/Vestas V90-2MW.pdf (accessed Feb. 19, 2024).

- J. Chaudhari, “Understanding Autoregressive (AR) Models for Time Series Forecasting,” Jul 25, 2023, 2023. https://jaichaudhari.medium.com/understanding-autoregressive-ar-models-for-time-series-forecasting-508016498a1e (accessed Dec. 31, 2024).

- J. M. Agency, “JMA Height for Niigata (in Japanese),” 2024. https://www.jma-net.go.jp/niigata/gaikyo/geppo/kishou_ichiran.pdf.

- F. Bañuelos-Ruedas, C. Á. Camacho, and S. Rios-Marcuello, “Methodologies Used in the Extrapolation of Wind Speed Data at Different Heights and Its Impact in the Wind Energy Resource Assessment in a Region,” Wind Farm - Technical Regulations, Potential Estimation and Siting Assessment, p. 100, 2011. [CrossRef]

- A. Hiroshi, K. Yasutsugu, and I. Meng, “A method for estimating offshore winds using a three-dimensional wind model,” Japan Society of Civil Engineers (in Japanese), Vol. 54, p. 134, 2007, [Online]. Available: http://library.jsce.or.jp/jsce/open/00008/2007/54-0131.pdf, accessed date is october 13th, 2023.

- H. Glattfelder, L. Huser, P. Dörfler, and J. Steinbach, “Automatic Control for Hydroelectric Power Plants,” Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Vol. XVIII. [Online]. Available: https://www.eolss.net/Sample-Chapters/C18/E6-43-33-04.pdf (accessed Oct. 25, 2023).

| Coverage type | Amount | Generating power |

|---|---|---|

| Sunny | 0 | 1 |

| Cloudy | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| Rainy | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| Rainy with snow | 1 | 0 |

| Snowy | 1 | 0 |

| Rectangles (1-49) | Related land ratio | Land and cloud Impacts | Temporal clear sky power (Wp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-3, 8, 9, 15, 28, 35, 41-49 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0.17 | 0.04539 | 0 |

| 6 | 0.65 | 0.195 | 0 |

| 7 | 0.08 | 0.024 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.15 | 0.07875 | 0 |

| 11 | 0.7 | 0.21 | 3.139 |

| 12 | 1 | 0.3 | 9.202 |

| 13 | 1 | 0.3 | 15.327 |

| 14 | 0.4 | 0.12 | 20.884 |

| 16 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 25.402 |

| 17 | 0.95 | 0.6175 | 28.521 |

| 18 | 1 | 0.3 | 30 |

| 19 | 1 | 0.3 | 29.7254 |

| 20 | 0.8 | 0.24 | 27.72 |

| 21 | 0.2 | 0.06 | 24.132 |

| 22 | 0.4 | 0.34 | 19.25 |

| 23 | 1 | 1 | 13.46 |

| 24 | 1 | 0.65 | 7.273 |

| 25 | 1 | 0.3 | 1.463 |

| 26 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 |

| 27 | 0.27 | 0.081 | 0 |

| 29 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0 |

| 30 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0 |

| 31 | 1 | 0.65 | |

| 32 | 1 | 0.3 | |

| 33 | 0.8 | 0.24 | |

| 34 | 0.1 | 0.03 | |

| 36 | 0.21 | 0.21 | |

| 37 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |

| 38 | 0.56 | 0.364 | |

| 39 | 0.32 | 0.096 | |

| 40 | 0.08 | 0.024 | |

| 39.1 | |||

| Time since start-up operation (s) | |

|---|---|

| To the end of bypass valve opening | 21 |

| Until the end of the main valve opening | 156 |

| Waterwheel start-up | 160 |

| Up to excitation | 206 |

| Until the automatic synchronization system is activated |

233 |

| Up to synchronous parallelism | 245 |

| Up to a given load | 347 |

| Location | Ratio |

|---|---|

| On the sea | 0.60 |

| Low-lying Island | 0.55 |

| Coast on windward side, low land in the vicinity | 0.50 |

| Downwind side of the coast, low land, or sea in the vicinity | 0.40 |

| Open land with few obstructions | 0.40 |

| Shielded land and cities | 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).