Submitted:

31 January 2025

Posted:

31 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction leading to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) exhibits distinct molecular and immune signatures that are influenced by factors like gut microbiota. The gut microbiome interacts with the liver via a bidirectional relationship the gut-liver axis. The microbial metabolites, sirtuins and immune responses play a pivotal role in different metabolic diseases. This extensive review explores the complex and multifaceted interrelationship between sirtuins and gut microbiota, highlighting their importance in both health and disease, particularly in relation to metabolic dysfunction and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Sirtuins (SIRTs), classified as a group of NAD+-dependent deacetylases, serve as crucial modulators of a wide spectrum of cellular functions, including metabolic pathways, the inflammatory response, and the process of senescence. Their subcellular localization and diverse functions link them to various health conditions, including NAFLD and cancer. Concurrently, the gut microbiota, comprising diverse microorganisms, significantly influences host metabolism and immune responses. Recent findings indicate that sirtuins modulate gut microbiota composition and function, while the microbiota can affect sirtuin activity. This bidirectional relationship is particularly relevant in metabolic disorders, where dysbiosis contributes to disease progression. The review highlights recent findings on the roles of specific sirtuins in maintaining gut health and their implications in metabolic dysfunction and HCC development. Understanding these interactions offers potential therapeutic avenues for managing diseases linked to metabolic dysregulation and liver pathology.

Keywords:

1. Background

2. Overview of Sirtuins and Their Biological Functions

Sirtuins Classification and Subcellular Localization

1.2. Role of Sirtuins in Cellular Homeostasis and Metabolism

| Sirtuin | Class | Type of Activity | Acyl Substrates | Cellular Function | Target substrates | Metabolic role | Biological role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIRT1 | I | Strong deacytylase activity | Remove acetyl and long chain fatty acyl group from Lysine | Formation of facultative chromatin, Mitochondrial biogenesis, | p53, FOXO1/3, NF-κB, CRTC2, PGAM-1, PGC1α, SREBP, LXR, FXR, LKB1 |

Fatty acid oxidation, Regulation of cholesterol and bile acid homeostasis | Cell survival and lipid metabolism |

| SIRT2 | I | Both deacetylase and mono-ADP-ribosyl transferase activity |

Remove of acetyl, long-chain fatty acyl, 4-oxononanoyl, and benzoyl groups |

Cell cycle regulation, Tumor suppression/promotion Neurodegeneration |

α-Tubulin, FOXO1, FOXO3, p300 |

Promotion of lipolysis in adipocytes |

Regulation of cell cycle and cell motility |

| SIRT3 | I | Both deacetylase and mono-ADP-ribosyl transferase activity |

Remove acetyl and long-chain fatty acyl groups from lysine |

Regulation of mitochondrial activity Protection against oxidative stress Tumor suppression |

LCAD, ACS2, SOD2, IDH2, HMGCS, OTC, SOD2, subunits of the electron transport chain and ATP synthase |

Metabolism and thermogenesis | |

| SIRT4 | Class II | Mono-ADP-ribosyl transferase activity |

Remove lipoyl, biotinyl, methylglutaryl, hydroxymethylglutaryl, and 3-methylglutaconyl groups |

Tumor suppression |

IDE, ANT2, ANT3, GDH, MCD, PDH |

Glucose metabolism Amino acid catabolism |

Glucose metabolism and Insulin secretion |

| SIRT5 | Class III | Weak deacetylase activity |

Removes charged malonyl, succinyl, and glutaryl groups |

CPS1, UOX |

Urea cycle Fatty acid metabolism Amino acid metabolism |

Cellular energy Metabolism |

|

| SIRT6 | Class IV | Mono-ADP-ribosyl transferase activity |

Remove acetyl and long-chain fatty acyl groups |

Genomic stability/DNA repair |

HIF1α, PARP1, TNFα, GCN5 |

Glucose and lipid metabolism Inflammation |

DNA repair/Glucose homeostasis |

| SIRT7 | Class IV | Mono-ADP-ribosyl transferase activity |

Remove acetyl groups |

Ribosome biogenesis Tumor promotion |

RNA polymerase 1 |

Metabolism, rDNA transcription |

3. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Host Health and Disease

4. Interrelationship Between Sirtuins and Gut Microbiota: A Bidirectional Perspective

4.1. Influence of Sirtuins on Gut Microbiota Composition

| Sirtuin | Roles of Sirtuins in Gut Health | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| SIRT1 | Maintains intestinal epithelial barrier integrity, regulates inflammation, and modulates autophagy, potentially influencing gut microbiota composition and diversity. | [81,93,94,95] |

| SIRT2 | Regulates intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation, impacting the gut environment and reducing inflammation, facilitating better host-microbiota interactions. | [85,96,97] |

| SIRT3 | Enhances mitochondrial function in intestinal cells, regulates oxidative stress, and maintains gut barrier homeostasis; deficiency leads to microbial dysbiosis and impaired permeability. | [84,98,99] |

| SIRT4 | Modulates amino acid metabolism in intestinal cells, potentially influencing nutrient availability for gut microbiota. | [89,100] |

| SIRT5 | Regulates cellular homeostasis and various metabolic pathways in intestinal cells, potentially influencing nutrient availability for gut microbiota. | [101,102] |

| SIRT6 | Maintains intestinal epithelial barrier integrity, mitigates inflammation, and enhances favourable immune responses; may affect gut microbiota composition and diversity. | [103,104,105] |

| SIRT7 | Maintains intestinal homeostasis and modulates inflammation; potentially affecting gut microbiota composition. | [92,106] |

4.2. Impact of Gut Microbiota on Sirtuin Activity

5. Role of Sirtuins and Gut Microbiota in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD)

6. Role of Sirtuins and Gut Microbiota in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

| Disease | Composition Change | References | |

| Increase | Decrease | ||

| NAFLD |

Streptococcus, Megasphaera, Enterobacteriaceae, Streptococcus, Gallibacterium |

Bacillus and Lactococcus, Pseudomonas, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Catenibacterium, Rikenellaceae, Mogibacterium, Peptostreptococcaceae | [171] |

| Firmicutes (Streptococcus mitis and Roseburia inulinivorans) and Bacteroidetes (Barnesiella intestinihominis and Bacteroides uniformis) |

Bacteroidetes (Prevotella sp.CAG 520, Prevotella sp. AM42 24, Butyricimonas virosa, and Odoribacter splanchnicus), Proteobacteria (Escherichia coli), Lentisphaerae (Victivallis vadensis), and Firmicutes (Holdemanella biformis, Dorea longicatena, Allisonella histaminiformans, and Blautia obeum) |

[172] | |

| Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Bacteroides, Alistipes, Verrucomicrobia, Faecalibaculum, Helicobacter, Epsilonbacteraeota | Muribaculaceae, Lactobacillus | [173] | |

| HCC | Escherichia coli | [174] | |

| Proteobacteria, Desulfococcus, Enterobacter, Prevotella, Veillonella | Cetobacterium | [175] | |

| Bacteroides | Akkermansia, Bifidobacterium | [176] | |

| Neisseria, Enterobacteriaceae, Veillonella, Limnobacter | Enterococcus, Phyllobacterium, lostridium, Ruminococcus, Coprococcus | [177] | |

| Proteobacteria, Enterobacteriaceae, Bacteroides xylanisolvens, B. caecimuris, Ruminococcus gnavus, Clostridium bolteae, Veillonella parvula | Erysipelotrichaceae, Oscillospiraceae | [178] | |

|

Klebsiella, Haemophilus |

Alistipes, Phascolarctobacterium, Ruminococcus | [179] | |

7. Interventions Targeting Sirtuins and Gut Microbiota

a. Sirtuin Activators

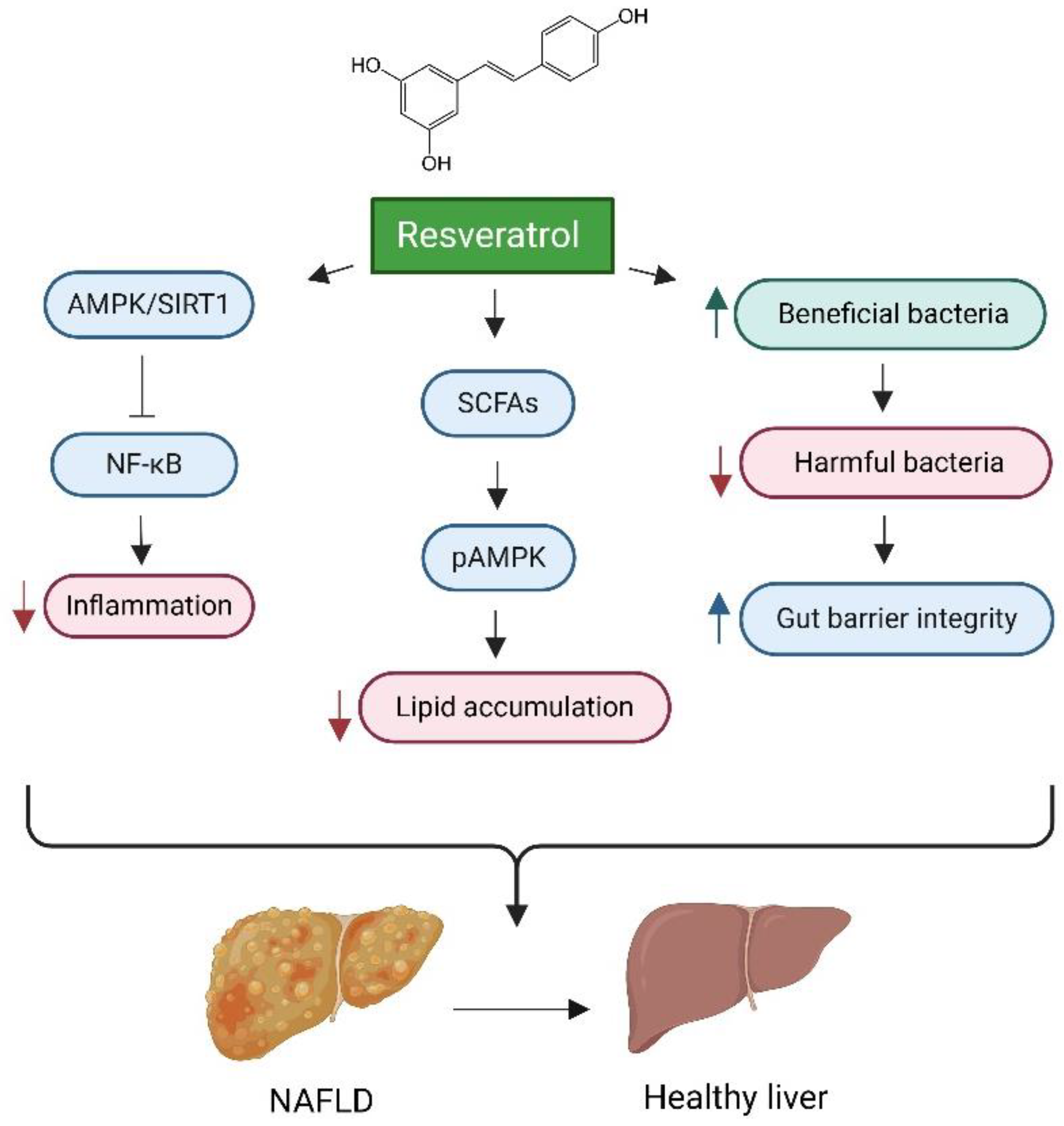

Resveratrol

Pterostilbene

E1231

Quercetin

Nicotinamide Riboside (NR)

Berberine

Yinchen Linggui Zhugan Decoction (YLZD)

The Tangshen Formula (TSF)

Curcumin

Dihydromyricetin

b. Sirtuin Inhibitors

AK-7

8. Gut Microbiota-Based Interventions: Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, Q.; Zhang, T.-N.; Chen, H.-h.; Yu, X.-F.; Lv, J.; Liu, Y.-y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.; Wei, Y.-F.; Guo, J.-y.; Liu, F.-H.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y., The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7.

- Bhatt, V.; Tiwari, A.K. Sirtuins, a key regulator of ageing and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Int. J. Neurosci. 2022, 133, 1167–1192. [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, M.P.; Quiroga, A.D.; Palma, N.F. Role of sirtuins in hepatocellular carcinoma progression and multidrug resistance: Mechanistical and pharmacological perspectives. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 212, 115573. [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Saeed, F.; Shah, Y.A.; Hussain, M.; Rabail, R.; Socol, C.T.; Hassoun, A.; Pateiro, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Rusu, A.V.; et al. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Seo, S.-U.; Kweon, M.-N. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites tune host homeostasis fate. Semin. Immunopathol. 2024, 46, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, Y.; Xue, C.; Kang, X.; Sun, C.; Peng, H.; Fang, L.; Han, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhao, C. SIRT2 Deficiency Aggravates Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through Modulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8970. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Mahur, P.; Muthukumaran, J.; Singh, A.K.; Jain, M. Shedding light on structure, function and regulation of human sirtuins: a comprehensive review. 3 Biotech 2022, 13, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, A.; Rehman, K.; Kamal, S.; Akash, M.S.H. Versatile role of sirtuins in metabolic disorders: From modulation of mitochondrial function to therapeutic interventions. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23047. [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, S.; Mele, E.; Di Filippo, F.; Viggiano, A.; Meccariello, R. Sirt1 Activity in the Brain: Simultaneous Effects on Energy Homeostasis and Reproduction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1243. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Long, X.; Ruan, X.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wo, L.; Huang, D.; Lin, L.; Wang, D.; Xia, L.; et al. SIRT2-mediated deacetylation and deubiquitination of C/EBPβ prevents ethanol-induced liver injury. Cell Discov. 2021, 7, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Lambona, C.; Zwergel, C.; Valente, S.; Mai, A. SIRT3 Activation a Promise in Drug Development? New Insights into SIRT3 Biology and Its Implications on the Drug Discovery Process. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 1662–1689. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Jin, Z.; Wu, J.; Cai, G.; Yu, X. Sirtuin family in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1186231. [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Ndiaye, M.A.; Singh, C.K.; Ahmad, N. Mitochondrial Sirtuins in Skin and Skin Cancers. Photochem. Photobiol. 2020, 96, 973–980. [CrossRef]

- Poljšak, B.; Kovač, V.; Špalj, S.; Milisav, I. The Central Role of the NAD+ Molecule in the Development of Aging and the Prevention of Chronic Age-Related Diseases: Strategies for NAD+ Modulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2959. [CrossRef]

- Kosciuk, T.; Wang, M.; Hong, J.Y.; Lin, H. Updates on the epigenetic roles of sirtuins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2019, 51, 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F.A. Current role of mammalian sirtuins in DNA repair. 2019, 80, 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Roos, W.P.; Krumm, A. The multifaceted influence of histone deacetylases on DNA damage signalling and DNA repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 10017–10030. [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.R.; Ferrer, C.M.; Mostoslavsky, R. SIRT6, a Mammalian Deacylase with Multitasking Abilities. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 145–169. [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.J.; Parsons, J.L. Base Excision Repair, a Pathway Regulated by Posttranslational Modifications. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016, 36, 1426–1437. [CrossRef]

- Alves-Fernandes, D.K.; Jasiulionis, M.G. The Role of SIRT1 on DNA Damage Response and Epigenetic Alterations in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3153. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Cao, N.; Fenech, M.; Wang, X. Role of Sirtuins in Maintenance of Genomic Stability: Relevance to Cancer and Healthy Aging. DNA Cell Biol. 2016, 35, 542–575. [CrossRef]

- O'Callaghan, C.; Vassilopoulos, A. Sirtuins at the crossroads of stemness, aging, and cancer. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 1208–1218. [CrossRef]

- Chojdak-Łukasiewicz, J.; Bizoń, A.; Waliszewska-Prosół, M.; Piwowar, A.; Budrewicz, S.; Pokryszko-Dragan, A. Role of Sirtuins in Physiology and Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2434. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y. A.; Kim, J. E.; Jo, M. J.; Ko, G. J., The Role of Sirtuins in Kidney Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21.

- Kumari, P.; Tarighi, S.; Braun, T.; Ianni, A. SIRT7 Acts as a Guardian of Cellular Integrity by Controlling Nucleolar and Extra-Nucleolar Functions. Genes 2021, 12, 1361. [CrossRef]

- Maissan, P.; Mooij, E.J.; Barberis, M. Sirtuins-Mediated System-Level Regulation of Mammalian Tissues at the Interface between Metabolism and Cell Cycle: A Systematic Review. Biology 2021, 10, 194. [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, B.N.; Vaquero, A.; Schindler, K. Sirtuins in female meiosis and in reproductive longevity. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2020, 87, 1175–1187. [CrossRef]

- Kratz, E.M.; Kokot, I.; Dymicka-Piekarska, V.; Piwowar, A. Sirtuins—The New Important Players in Women’s Gynecological Health. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 84. [CrossRef]

- Hamaidi, I.; Kim, S. Sirtuins are crucial regulators of T cell metabolism and functions. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Watroba, M.; Szukiewicz, D. Sirtuins at the Service of Healthy Longevity. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, E.; Hou, J.; Ke, X.; Abbas, M.N.; Kausar, S.; Zhang, L.; Cui, H. The Roles of Sirtuin Family Proteins in Cancer Progression. Cancers 2019, 11, 1949. [CrossRef]

- Carafa, V.; Altucci, L.; Nebbioso, A. Dual Tumor Suppressor and Tumor Promoter Action of Sirtuins in Determining Malignant Phenotype. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 38. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Dong, Z.; Ke, X.; Hou, J.; Zhao, E.; Zhang, K.; Wang, F.; Yang, L.; Xiang, Z.; Cui, H. The roles of sirtuins family in cell metabolism during tumor development. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2018, 57, 59–71. [CrossRef]

- Alves-Fernandes, D.K.; Jasiulionis, M.G. The Role of SIRT1 on DNA Damage Response and Epigenetic Alterations in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3153. [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.-Y.; Lu, X.-T.; Hou, M.-L.; Cao, T.; Tian, Z. Sirtuin1-p53: A potential axis for cancer therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 212, 115543. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Huang, P.; Hu, C. The role of SIRT2 in cancer: A novel therapeutic target. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 3297–3304. [CrossRef]

- Onyiba, C.I.; Scarlett, C.J.; Weidenhofer, J. The Mechanistic Roles of Sirtuins in Breast and Prostate Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5118. [CrossRef]

- George, J.; Ahmad, N. Mitochondrial Sirtuins in Cancer: Emerging Roles and Therapeutic Potential. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2500–2506. [CrossRef]

- Fiorentino, F.; Carafa, V.; Favale, G.; Altucci, L.; Mai, A.; Rotili, D. The Two-Faced Role of SIRT6 in Cancer. Cancers 2021, 13, 1156. [CrossRef]

- Karbasforooshan, H.; Hayes, A.W.; Mohammadzadeh, N.; Zirak, M.R.; Karimi, G. The possible role of Sirtuins and microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma therapy. Cell Cycle 2020, 19, 3209–3221. [CrossRef]

- Farcas, M.; Gavrea, A.-A.; Gulei, D.; Ionescu, C.; Irimie, A.; Catana, C.S.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. SIRT1 in the Development and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 148. [CrossRef]

- Matijašić, M.; Meštrović, T.; Čipčić Paljetak, H.; Perić, M.; Barešić, A.; Verbanac, D., Gut Microbiota beyond Bacteria—Mycobiome, Virome, Archaeome, and Eukaryotic Parasites in IBD. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21.

- Vemuri, R.; Shankar, E.M.; Chieppa, M.; Eri, R.; Kavanagh, K. Beyond Just Bacteria: Functional Biomes in the Gut Ecosystem Including Virome, Mycobiome, Archaeome and Helminths. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 483. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bonete, M.J.; Rajan, A.; Suriano, F.; Layunta, E. The Underrated Gut Microbiota Helminths, Bacteriophages, Fungi, and Archaea. Life 2023, 13, 1765. [CrossRef]

- Sasso, J.M.; Ammar, R.M.; Tenchov, R.; Lemmel, S.; Kelber, O.; Grieswelle, M.; Zhou, Q.A. Gut Microbiome–Brain Alliance: A Landscape View into Mental and Gastrointestinal Health and Disorders. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 1717–1763. [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L.; Giubilei, L.; Procopio, A.C.; Spagnuolo, R.; Luzza, F.; Boccuto, L.; Scarpellini, E. Gut Microbiota in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Complex Interplay. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5323. [CrossRef]

- Barko, P. C.; McMichael, M. A.; Swanson, K. S.; Williams, D. A., The Gastrointestinal Microbiome: A Review. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2017, 32, 9 - 25.

- Pickard, J.M.; Zeng, M.Y.; Caruso, R.; Núñez, G. Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 279, 70–89. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Prabhakar, M.R.; Mohanty, A.; Meena, S.S. Influence of gut microbiome on the human physiology. Syst. Microbiol. Biomanufacturing 2021, 2, 217–231. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Gutierrez, E.; Mayer, M.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Narbad, A. Gut microbiota as a source of novel antimicrobials. Gut Microbes 2018, 10, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- I, R.; G, G.; A, H.; K, S.; J, S.; I, T.; K, T., Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food compo nents. European Journal of Nutrition.

- Levy, M.; Blacher, E.; Elinav, E., Microbiome, metabolites and host immunity. Current opinion in microbiology 2017, 35, 8-15.

- Fung, T.C.; Olson, C.A.; Hsiao, E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat. Neurosci. 2017, 20, 145–155. [CrossRef]

- Gasaly, N.; de Vos, P.; Hermoso, M.A. Impact of Bacterial Metabolites on Gut Barrier Function and Host Immunity: A Focus on Bacterial Metabolism and Its Relevance for Intestinal Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 658354. [CrossRef]

- Postler, T.S.; Ghosh, S. Understanding the Holobiont: How Microbial Metabolites Affect Human Health and Shape the Immune System. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 110–130. [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Flint, H.J. Formation of propionate and butyrate by the human colonic microbiota. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 29–41. [CrossRef]

- Blaak, E.E.; Canfora, E.E.; Theis, S.; Frost, G.; Groen, A.K.; Mithieux, G.; Nauta, A.; Scott, K.; Stahl, B.; Van Harsselaar, J.; et al. Short chain fatty acids in human gut and metabolic health. Benef. Microbes 2020, 11, 411–455. [CrossRef]

- Parada Venegas, D.; De La Fuente, M.K.; Landskron, G.; González, M.J.; Quera, R.; Dijkstra, G.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Faber, K.N.; Hermoso, M.A. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-Mediated Gut Epithelial and Immune Regulation and Its Relevance for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 277. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Marinelli, L.; Blottière, H.M.; Larraufie, P.; Lapaque, N. SCFA: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2021, 80, 37–49. [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhang, P.; Shen, L.; Niu, L.; Tan, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Bai, L.; Hao, X.; Li, X.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Association with Signalling Pathways in Inflammation, Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6356. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Perez, O. L.; Cruz-Ramon, V. C.; Chinchilla-López, P.; Méndez-Sánchez, N., The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Bile Acid Metabolism. Annals of hepatology 2017, 16 Suppl. 1: s3-105., s15-s20.

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: Metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Oliphant, K.; Allen-Vercoe, E. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome: major fermentation by-products and their impact on host health. Microbiome 2019, 7, 91. [CrossRef]

- Moszak, M.; Szulińska, M.; Bogdański, P. You Are What You Eat—The Relationship between Diet, Microbiota, and Metabolic Disorders—A Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1096. [CrossRef]

- Anwar, H.; Iftikhar, A.; Muzaffar, H.; Almatroudi, A.; Allemailem, K.S.; Navaid, S.; Saleem, S.; Khurshid, M. Biodiversity of Gut Microbiota: Impact of Various Host and Environmental Factors. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rinninella, E.; Raoul, P.; Cintoni, M.; Franceschi, F.; Miggiano, G.A.D.; Gasbarrini, A.; Mele, M.C. What Is the Healthy Gut Microbiota Composition? A Changing Ecosystem across Age, Environment, Diet, and Diseases. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Chen, H.; Yang, F.; Huang, J.; Jiao, X.; Zhang, Y. Environmental factors and gut microbiota: Toward better conservation of deer species. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1136413. [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, D.; Weissbrod, O.; Barkan, E.; Kurilshikov, A.; Korem, T.; Zeevi, D.; Costea, P.I.; Godneva, A.; Kalka, I.N.; Bar, N.; et al. Environment dominates over host genetics in shaping human gut microbiota. Nature 2018, 555, 210–215. [CrossRef]

- Kurilshikov, A.; Wijmenga, C.; Fu, J.; Zhernakova, A. Host Genetics and Gut Microbiome: Challenges and Perspectives. Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 633–647. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S. Factors influencing development of the infant microbiota: from prenatal period to early infancy. Clin. Exp. Pediatr. 2021, 65, 438–447. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Yang, H. Factors affecting the composition of the gut microbiota, and its modulation. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7502. [CrossRef]

- Kriss, M.; Hazleton, K.Z.; Nusbacher, N.M.; Martin, C.G.; A Lozupone, C. Low diversity gut microbiota dysbiosis: drivers, functional implications and recovery. 2018, 44, 34–40. [CrossRef]

- Heravi, F.S. Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Diseases: Mechanisms, Treatment, Challenges, and Future Recommendations. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2024, 11, 18–33. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G.A.; Hennet, T. Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 2959–2977. [CrossRef]

- Willighagen, E., Defining Dysbiosis for a Cluster of Chronic Diseases. Scientific Reports 2019, 9.

- Jalandra, R.; Dhar, R.; Pethusamy, K.; Sharma, M.; Karmakar, S. Dysbiosis: Gut feeling. F1000Research 2022, 11, 911. [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J. B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Z. S., Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7.

- Kho, Z.Y.; Lal, S.K. The Human Gut Microbiome – A Potential Controller of Wellness and Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1835. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, G.; Cao, H.; Yu, D.; Fang, X.; Vos, W.M.; Wu, H. Gut dysbacteriosis and intestinal disease: mechanism and treatment. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 787–805. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.-L.; Zhou, M.; Kang, C.; Lang, H.-D.; Chen, M.-T.; Hui, S.-C.; Wang, B.; Mi, M.-T. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and Sirtuin-3 in colonic inflammation and tumorigenesis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018, 50, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Caron, A.Z.; He, X.; Mottawea, W.; Seifert, E.L.; Jardine, K.; Dewar-Darch, D.; Cron, G.O.; Harper, M.; Stintzi, A.; McBurney, M.W. The SIRT1 deacetylase protects mice against the symptoms of metabolic syndrome. FASEB J. 2013, 28, 1306–1316. [CrossRef]

- Vikram, A.; Kim, Y.-R.; Kumar, S.; Li, Q.; Kassan, M.; Jacobs, J.S.; Irani, K. Vascular microRNA-204 is remotely governed by the microbiome and impairs endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation by downregulating Sirtuin1. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12565. [CrossRef]

- Wellman, A.S.; Metukuri, M.R.; Kazgan, N.; Xu, X.; Xu, Q.; Ren, N.S.; Czopik, A.; Shanahan, M.T.; Kang, A.; Chen, W.; et al. Intestinal Epithelial Sirtuin 1 Regulates Intestinal Inflammation During Aging in Mice by Altering the Intestinal Microbiota. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 772–786. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, C.; Onose, G.; Poștaru, M.; Turnea, M.; Rotariu, M.; Galaction, A.I. Hydrogen Sulfide and Gut Microbiota: Their Synergistic Role in Modulating Sirtuin Activity and Potential Therapeutic Implications for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1480. [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Yu, T.; Lu, X.; Hong, J.Y.; Yang, M.; Zi, Y.; Ho, T.T.; Lin, H. Sirt2 inhibition improves gut epithelial barrier integrity and protects mice from colitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xie, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, T.; Sui, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.; Geng, X.; Xue, D.; et al. Gut microbiota-derived nicotinamide mononucleotide alleviates acute pancreatitis by activating pancreatic SIRT3 signalling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 180, 647–666. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Hui, S.; Lang, H.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, C.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yi, L.; Mi, M. SIRT3 Deficiency Promotes High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Correlation with Impaired Intestinal Permeability through Gut Microbial Dysbiosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 63, e1800612. [CrossRef]

- Knop, M.; Treitz, C.; Bettendorf, S.; Bossen, J.; von Frieling, J.; Doms, S.; Bruchhaus, I.; Kühnlein, R. P.; Baines, J. F.; Tholey, A.; Roeder, T., A mitochondrial sirtuin shapes the intestinal microbiota by controlling lysozyme expression. bioRxiv 2023.

- Tucker, S.A.; Hu, S.-H.; Vyas, S.; Park, A.; Joshi, S.; Inal, A.; Lam, T.; Tan, E.; Haigis, K.M.; Haigis, M.C. SIRT4 loss reprograms intestinal nucleotide metabolism to support proliferation following perturbation of homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113975. [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Zhang, Z.; Bao, R.; Guo, X.; Gu, Y.; Yang, W.; Wei, J.; Chen, X.; Tong, L.; Meng, J.; et al. Loss of SIRT5 promotes bile acid-induced immunosuppressive microenvironment and hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2022, 77, 453–466. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Low, V.; Cho, S.; Ping, L.; Peng, K.; Li, X.; Qiu, Y.; et al. Decreased Enterobacteriaceae translocation due to gut microbiota remodeling mediates the alleviation of premature aging by a high-fat diet. Aging Cell 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Byun, J.; Jung, S.; Kim, B.; Lee, K.; Jeon, H.; Lee, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, E.; Jeen, Y.; et al. Sirtuin 7 Inhibitor Attenuates Colonic Mucosal Immune Activation in Mice—Potential Therapeutic Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2693. [CrossRef]

- Caruso, R.; Marafini, I.; Franzè, E.; Stolfi, C.; Zorzi, F.; Monteleone, I.; Caprioli, F.; Colantoni, A.; Sarra, M.; Sedda, S.; et al. Defective expression of SIRT1 contributes to sustain inflammatory pathways in the gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2014, 7, 1467–1479. [CrossRef]

- Lytvynenko, A.; Voznesenskaya, T.; Janchij, R. SIRT1 IS A REGULATOR OF AUTOPHAGY IN INTESTINAL CELLS. Fiziolohichnyĭ zhurnal 2020, 66, 97–103. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, W.; Sun, L.; Yang, S.; Lu, D.; Liu, Y.; Yang, H. [Role of SIRT1 in the protection of intestinal epithelial barrier under hypoxia and its mechanism]. Zhonghua wei chang wai ke za zhi = Chinese journal of gastrointestinal surgery 2014, 17, 602–6.

- Li, C.; Zhou, Y.; Rychahou, P.; Weiss, H.L.; Lee, E.Y.; Perry, C.L.; Barrett, T.A.; Wang, Q.; Evers, B.M. SIRT2 Contributes to the Regulation of Intestinal Cell Proliferation and Differentiation. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 43–57. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.-J.; Zhang, T.-N.; Chen, H.-H.; Yu, X.-F.; Lv, J.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Liu, Y.-S.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, J.-Q.; Wei, Y.-F.; Guo, J.-Y.; Liu, F.-H.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Liu, C.-G.; Zhao, Y.-H., The sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, (1), 402.

- Chen, M.; Hui, S.; Lang, H.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, C.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yi, L.; Mi, M. SIRT3 Deficiency Promotes High-Fat Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Correlation with Impaired Intestinal Permeability through Gut Microbial Dysbiosis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 63, e1800612. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Cao, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Tu, J.; Zhou, W.; He, J.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Cai, R.; et al. SENP1-Sirt3 Signaling Controls Mitochondrial Protein Acetylation and Metabolism. Mol. Cell 2019, 75, 823–834.e5. [CrossRef]

- Nasrin, N.; Wu, X.; Fortier, E.; Feng, Y.; Bare', O.C.; Chen, S.; Ren, X.; Wu, Z.; Streeper, R.S.; Bordone, L. SIRT4 Regulates Fatty Acid Oxidation and Mitochondrial Gene Expression in Liver and Muscle Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31995–32002. [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizi, E.; Fiorentino, F.; Carafa, V.; Altucci, L.; Mai, A.; Rotili, D. Emerging Roles of SIRT5 in Metabolism, Cancer, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cells 2023, 12, 852. [CrossRef]

- Bringman-Rodenbarger, L.R.; Guo, A.H.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; Lombard, D.B. Emerging Roles for SIRT5 in Metabolism and Cancer. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 677–690. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Yang, C.; He, W.-Q.; Yu, J.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, R.; Ma, H.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; et al. Sirtuin 6 maintains epithelial STAT6 activity to support intestinal tuft cell development and type 2 immunity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Guo, Y.; Ping, L.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z. Protective Effects of SIRT6 Overexpression against DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice. Cells 2020, 9, 1513. [CrossRef]

- Lerrer, B.; Gertler, A.A.; Cohen, H.Y. The complex role of SIRT6 in carcinogenesis. Carcinog. 2015, 37, 108–118. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Chang, H.-C.; Tang, Y.-C. SIRT7 Facilitates CENP-A Nucleosome Assembly and Suppresses Intestinal Tumorigenesis. iScience 2020, 23, 101461. [CrossRef]

- Haslberger, A.; Lilja, S.; Bäck, H.; Stoll, C.; Mayer, A.; Pointner, A.; Hippe, B.; Krammer, U. Increased Sirtuin expression, senescence regulating miRNAs, mtDNA, and Bifidobateria correlate with wellbeing and skin appearance after Sirtuin- activating drink. Bioact. Compd. Heal. Dis. 2021, 4, 45. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Durán, P.; Díaz, M.P.; Chacín, M.; Santeliz, R.; Mengual, E.; Gutiérrez, E.; León, X.; Díaz, A.; Bernal, M.; et al. Exploring the Relationship between the Gut Microbiota and Ageing: A Possible Age Modulator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2023, 20, 5845. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.; Mach, N. The Crosstalk between the Gut Microbiota and Mitochondria during Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 319. [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.; Feng, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pan, M.; He, F.; Wu, R.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; et al. Gut microbiota accelerates cisplatin-induced acute liver injury associated with robust inflammation and oxidative stress in mice. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Chandrashekharappa, S.; Bodduluri, S.R.; Baby, B.V.; Hegde, B.; Kotla, N.G.; Hiwale, A.A.; Saiyed, T.; Patel, P.; Vijay-Kumar, M.; et al. Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Massad, K.; Kimchi, E.T.; Staveley-O’carroll, K.F.; Li, G. Gut microbiota and metabolite interface-mediated hepatic inflammation. Immunometabolism 2024, 6, e00037–e00037. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, X.; Lv, A.; Fan, S.; Zhang, J., Saccharomyces Boulardii Modulates Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Neonatal Mice by Regulating the Sirtuin 1/NF-κB Pathway and the Intestinal Microbiota. Molecular Medicine Reports 2020, 22, (2), 671-680.

- Estes, C.; Razavi, H.; Loomba, R.; Younossi, Z.; Sanyal, A.J. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 2018, 67, 123–133. [CrossRef]

- EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016, 64, (6), 1388-402.

- Tiniakos, D.G.; Vos, M.B.; Brunt, E.M. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Pathology and Pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2010, 5, 145–171. [CrossRef]

- Grander, C.; Grabherr, F.; Moschen, A.R.; Tilg, H. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Cause or Effect of Metabolic Syndrome. Visc. Med. 2016, 32, 329–334. [CrossRef]

- Paschos, P.; Paletas, K. Non alcoholic fatty liver disease two-hit process: multifactorial character of the second hit. Hippokratia 2009, 13, (2), 128.

- Jang, H.R.; Lee, H.-Y. Mechanisms linking gut microbial metabolites to insulin resistance. World J. Diabetes 2021, 12, 730–744. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Tang, X.; Chen, H.-Z. Sirtuins and Insulin Resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 748. [CrossRef]

- Caron, A.Z.; He, X.; Mottawea, W.; Seifert, E.L.; Jardine, K.; Dewar-Darch, D.; Cron, G.O.; Harper, M.; Stintzi, A.; McBurney, M.W. The SIRT1 deacetylase protects mice against the symptoms of metabolic syndrome. FASEB J. 2013, 28, 1306–1316. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Paneni, F.; Stein, S.; Matter, C.M. Modulating Sirtuin Biology and Nicotinamide Adenine Diphosphate Metabolism in Cardiovascular Disease—From Bench to Bedside. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Chandramowlishwaran, P.; Vijay, A.; Abraham, D.; Li, G.; Mwangi, S.M.; Srinivasan, S. Role of Sirtuins in Modulating Neurodegeneration of the Enteric Nervous System and Central Nervous System. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Liu, Y.-H.; Fu, Y.-C.; Liu, X.-M.; Zhou, X.-H. Direct evidence of sirtuin downregulation in the liver of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2014, 44, 410–418.

- Bruce, K.D.; Szczepankiewicz, D.; Sihota, K.K.; Ravindraanandan, M.; Thomas, H.; Lillycrop, K.A.; Burdge, G.C.; Hanson, M.A.; Byrne, C.D.; Cagampang, F.R. Altered cellular redox status, sirtuin abundance and clock gene expression in a mouse model of developmentally primed NASH. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2016, 1861, 584–593. [CrossRef]

- Canfora, E.E.; Meex, R.C.R.; Venema, K.; Blaak, E.E. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 261–273. [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Vigliotti, C.; Witjes, J.; Le, P.; Holleboom, A.G.; Verheij, J.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Clément, K. Gut microbiota and human NAFLD: disentangling microbial signatures from metabolic disorders. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 279–297. [CrossRef]

- Loo, T. M.; Kamachi, F.; Watanabe, Y.; Yoshimoto, S.; Kanda, H.; Arai, Y.; Nakajima-Takagi, Y.; Iwama, A.; Koga, T.; Sugimoto, Y., Gut microbiota promotes obesity-associated liver cancer through PGE2-mediated suppression of antitumor immunity. Cancer discovery 2017, 7, (5), 522-538.

- Bo, T.; Shao, S.; Wu, D.; Niu, S.; Zhao, J.; Gao, L. Relative variations of gut microbiota in disordered cholesterol metabolism caused by high-cholesterol diet and host genetics. Microbiologyopen 2017, 6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Coker, O.O.; Chu, E.S.; Fu, K.; Lau, H.C.H.; Wang, Y.-X.; Chan, A.W.H.; Wei, H.; Yang, X.; Sung, J.J.Y.; et al. Dietary cholesterol drives fatty liver-associated liver cancer by modulating gut microbiota and metabolites. Gut 2020, 70, 761–774. [CrossRef]

- Takaki, A.; Kawai, D.; Yamamoto, K. Multiple Hits, Including Oxidative Stress, as Pathogenesis and Treatment Target in Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 20704–20728. [CrossRef]

- Henao-Mejia, J.; Elinav, E.; Jin, C.; Hao, L.; Mehal, W.Z.; Strowig, T.; Thaiss, C.A.; Kau, A.L.; Eisenbarth, S.C.; Jurczak, M.J.; et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature 2012, 482, 179–185. [CrossRef]

- Wiest, R.; Albillos, A.; Trauner, M.; Bajaj, J. S.; Jalan, R., Targeting the gut-liver axis in liver disease. J Hepatol 2017, 67, (5), 1084-1103.

- Schnabl, B.; Brenner, D.A. Interactions Between the Intestinal Microbiome and Liver Diseases. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1513–1524. [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, J.K.; Waters, J.L.; Poole, A.C.; Sutter, J.L.; Koren, O.; Blekhman, R.; Beaumont, M.; Van Treuren, W.; Knight, R.; Bell, J.T.; et al. Human Genetics Shape the Gut Microbiome. Cell 2014, 159, 789–799. [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E.A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016, 65, 1038–1048. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Pan, Q.; Xin, F.-Z.; Zhang, R.-N.; He, C.-X.; Chen, G.-Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.-W.; Fan, J.-G. Sodium butyrate attenuates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice by improving gut microbiota and gastrointestinal barrier. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 60–75. [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Wang, B.; Kaliannan, K.; Wang, X.; Lang, H.; Hui, S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, M.; Chen, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Mediates the Protective Effects of Dietary Capsaicin against Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Associated Obesity Induced by High-Fat Diet. mBio 2017, 8, e00470-17. [CrossRef]

- Muccioli, G.G.; Naslain, D.; Bäckhed, F.; Reigstad, C.S.; Lambert, D.M.; Delzenne, N.M.; Cani, P.D. The endocannabinoid system links gut microbiota to adipogenesis. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010, 6, 392. [CrossRef]

- Lam, Y.Y.; Ha, C.W.Y.; Campbell, C.R.; Mitchell, A.J.; Dinudom, A.; Oscarsson, J.; Cook, D.I.; Hunt, N.H.; Caterson, I.D.; Holmes, A.J.; et al. Increased Gut Permeability and Microbiota Change Associate with Mesenteric Fat Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34233. [CrossRef]

- Everard, A.; Lazarevic, V.; Gaïa, N.; Johansson, M.; Ståhlman, M.; Bäckhed, F.; Delzenne, N.M.; Schrenzel, J.; Francois, P.; Cani, P.D. Microbiome of prebiotic-treated mice reveals novel targets involved in host response during obesity. ISME J. 2014, 8, 2116–2130. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A., Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019, 380, (15), 1450-1462.

- Akinyemiju, T.; Abera, S.; Ahmed, M.; Alam, N.; Alemayohu, M.A.; Allen, C.; Al-Raddadi, R.; Alvis-Guzman, N.; Amoako, Y.; Artaman, A.; et al. The Burden of Primary Liver Cancer and Underlying Etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the Global, Regional, and National Level: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1683–1691.

- Jindal, A.; Thadi, A.; Shailubhai, K. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Etiology and Current and Future Drugs. 2019, 9, 221–232. [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.J.; Cheung, R.; Ahmed, A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology 2014, 59, 2188–2195. [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Wirth, U.; Koch, D.; Schirren, M.; Drefs, M.; Koliogiannis, D.; Niess, H.; Andrassy, J.; Guba, M.; Bazhin, A.V.; et al. Metabolic Role of Autophagy in the Pathogenesis and Development of NAFLD. Metabolites 2023, 13, 101. [CrossRef]

- Itoh, M.; Suganami, T.; Nakagawa, N.; Tanaka, M.; Yamamoto, Y.; Kamei, Y.; Terai, S.; Sakaida, I.; Ogawa, Y. Melanocortin 4 Receptor–Deficient Mice as a Novel Mouse Model of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. American Journal of Pathology 2011, 179, 2454–2463. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xie, G., Bile Acid–microbiota Crosstalk in Gastrointestinal Inflammation and Carcinogenesis. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2017, 15, (2), 111-128.

- Milosevic, I.; Vujovic, A.; Barac, A.; Djelic, M.; Korac, M.; Radovanovic Spurnic, A.; Gmizic, I.; Stevanovic, O.; Djordjevic, V.; Lekic, N.; et al. Gut-Liver Axis, Gut Microbiota, and Its Modulation in the Management of Liver Diseases: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 395. [CrossRef]

- Farcas, M.; Gavrea, A.-A.; Gulei, D.; Ionescu, C.; Irimie, A.; Catana, C.S.; Berindan-Neagoe, I. SIRT1 in the Development and Treatment of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 148. [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Li, J.; Shan, Q.; Dai, H.; Lu, D.; Wen, X.; Song, P.; Xie, H.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J.; et al. USP22 mediates the multidrug resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma via the SIRT1/AKT/MRP1 signaling pathway. Mol. Oncol. 2017, 11, 682–695. [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.; Zhu, P.-X.; Yang, X.; Han, Z.-P.; Jiang, J.-H.; Zong, C.; Zhang, X.-G.; Liu, W.-T.; Zhao, Q.-D.; Fan, T.-T.; et al. Overexpression of SIRT1 promotes metastasis through epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 978. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, A.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, L.; Yu, Z.; Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Chen, X.; Shao, L.; Zhang, R.; et al. Gut microbiome analysis as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2018, 68, 1014–1023. [CrossRef]

- Pant, K.; Yadav, A. K.; Gupta, P.; Islam, R.; Saraya, A.; Venugopal, S. K., Butyrate induces ROS-mediated apoptosis by modulating miR-22/SIRT-1 pathway in hepatic cancer cells. Redox Biol 2017, 12, 340-349.

- Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, T.; Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Fu, S.; Wu, M.; Pan, Z.; Zhou, W. microRNA-22, downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and correlated with prognosis, suppresses cell proliferation and tumourigenicity. Br. J. Cancer 2010, 103, 1215–1220. [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, B.; Zhou, H.; Qiu, J.; Qin, L., MicroRNA-29 Regulates Tumor Progression and Survival Through miR-29a-SIRT1-Wnt/β-catenin Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. 2023.

- Wang, X.; Ling, S.; Wu, W.; Shan, Q.; Liu, P.; Wang, C.; Wei, X.; Ding, W.; Teng, X.; Xu, X., Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 22/Silent Information Regulator 1 Axis Plays a Pivotal Role in the Prognosis and 5-Fluorouracil Resistance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Digestive Diseases and Sciences 2019, 65, (4), 1064-1073.

- Xiong, H.; Ni, Z.; He, J.; Jiang, S.; Li, X.; Gong, W.; Zheng, L.; Chen, S.; Li, B.; Zhang, N.; et al. LncRNA HULC triggers autophagy via stabilizing Sirt1 and attenuates the chemosensitivity of HCC cells. Oncogene 2017, 36, 3528–3540. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-Q.; Guan, J.; Chen, S.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Z., Sirtuin 1 Protects the Mitochondria in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells via Suppressing Hypoxia-Induced Factor-1 Alpha Expression. 2022.

- Li, Y.; Xu, S.; Li, J.; Zheng, L.; Feng, M.; Wang, X.; Han, K.; Pi, H.; Li, M.; Huang, X.; et al. SIRT1 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by promoting PGC-1α-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 29255–29274. [CrossRef]

- Herranz, D.; Muñoz-Martin, M.; Cañamero, M.; Mulero, F.; Martinez-Pastor, B.; Fernandez-Capetillo, O.; Serrano, M. Sirt1 improves healthy ageing and protects from metabolic syndrome-associated cancer. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Jeng, Y.-M.; Yuan, R.-H.; Hsu, H.-C.; Chen, Y.-L. SIRT1 Promotes Tumorigenesis and Resistance to Chemotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma and its Expression Predicts Poor Prognosis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 19, 2011–2019. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, B.; Wong, N.; Lo, A. W.; To, K. F.; Chan, A. W.; Ng, M. H.; Ho, C. Y.; Cheng, S. H.; Lai, P. B.; Yu, J.; Ng, H. K.; Ling, M. T.; Huang, A. L.; Cai, X. F.; Ko, B. C., Sirtuin 1 is upregulated in a subset of hepatocellular carcinomas where it is essential for telomere maintenance and tumor cell growth. Cancer Res 2011, 71, (12), 4138-49.

- Tanos, B.; Rodriguez-Boulan, E. The epithelial polarity program: machineries involved and their hijacking by cancer. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6939–6957. [CrossRef]

- Portmann, S.; Fahrner, R.; Lechleiter, A.; Keogh, A.; Overney, S.; Laemmle, A.; Mikami, K.; Montani, M.; Tschan, M.P.; Candinas, D.; et al. Antitumor Effect of SIRT1 Inhibition in Human HCC Tumor Models In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2013, 12, 499–508. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chan, A.W.; To, K.-F.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, J.; Song, C.; Cheung, Y.-S.; Lai, P.B.; Cheng, S.-H.; et al. SIRT2 overexpression in hepatocellular carcinoma mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transition by protein kinase B/glycogen synthase kinase-3β/β-catenin signaling. Hepatology 2013, 57, 2287–2298. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Dorfman, R.G.; et al. Downregulation of SIRT2 Inhibits Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Inhibiting Energy Metabolism. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 10, 917–927. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Noh, J.H.; Jung, K.H.; Eun, J.W.; Bae, H.J.; Kim, M.G.; Chang, Y.G.; Shen, Q.; Park, W.S.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Sirtuin7 oncogenic potential in human hepatocellular carcinoma and its regulation by the tumor suppressors MiR-125a-5p and MiR-125b. Hepatology 2013, 57, 1055–1067. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Jung, K.-Y.; Kim, Y. H.; Xu, P.; Kang, B. E.; Jo, Y.; Pandit, N.; Kwon, J.; Gariani, K.; Gariani, J.; Lee, J.; Verbeek, J.; Nam, S.; Bae, S.-J.; Ha, K.-T.; Yi, H.-S.; Shong, M.; Kim, K.-H.; Kim, D.; Jung, H. J.; Lee, C.-W.; Kim, K. R.; Schoonjans, K.; Auwerx, J.; Ryu, D., Inhibition of SIRT7 Overcomes Sorafenib Acquired Resistance by Suppressing ERK1/2 Phosphorylation via the DDX3X-mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Drug Resistance Updates 2024, 73, 101054.

- Gu, Y.; Ding, C.; Yu, T.; Liu, B.; Tang, W.; Wang, Z.; Tang, X.; Liang, G.; Peng, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z., SIRT7 Promotes Hippo/YAP Activation and Cancer Cell Proliferation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Suppressing MST1. Cancer Science 2024, 115, (4), 1209-1223.

- Caussy, C.; Hsu, C.; Lo, M. T.; Liu, A.; Bettencourt, R.; Ajmera, V. H.; Bassirian, S.; Hooker, J.; Sy, E.; Richards, L.; Schork, N.; Schnabl, B.; Brenner, D. A.; Sirlin, C. B.; Chen, C. H.; Loomba, R., Link between gut-microbiome derived metabolite and shared gene-effects with hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in NAFLD. Hepatology 2018, 68, (3), 918-932.

- Zeybel, M.; Arif, M.; Li, X.; Altay, O.; Yang, H.; Shi, M.; Akyildiz, M.; Saglam, B.; Gonenli, M.G.; Yigit, B.; et al. Multiomics Analysis Reveals the Impact of Microbiota on Host Metabolism in Hepatic Steatosis. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104373. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Fu, Q.; Li, T.; Shao, K.; Zhu, X.; Cong, Y.; Zhao, X. Gut microbiota and butyrate contribute to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in premenopause due to estrogen deficiency. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0262855. [CrossRef]

- Grąt, M.; Wronka, K.; Krasnodębski, M.; Masior, Ł.; Lewandowski, Z.; Kosińska, I.; Grąt, K.; Stypułkowski, J.; Rejowski, S.; Wasilewicz, M.; et al. Profile of Gut Microbiota Associated With the Presence of Hepatocellular Cancer in Patients With Liver Cirrhosis. Transplant. Proc. 2016, 48, 1687–1691. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Huang, R.; Zhou, H.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Cao, P.; Zhong, K.; Ge, M.; Chen, X.; Hou, B.; et al. Analysis of the Relationship Between the Degree of Dysbiosis in Gut Microbiota and Prognosis at Different Stages of Primary Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1458. [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, F.R.; Bhoori, S.; Castelli, C.; Putignani, L.; Rivoltini, L.; Del Chierico, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Morelli, D.; Sterbini, F.P.; Petito, V.; et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Is Associated With Gut Microbiota Profile and Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2019, 69, 107–120. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, G.; Pang, Z.; Ran, N.; Gu, Y.; Guan, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zuo, X.; Pan, H.; Zheng, J.; et al. Liver cirrhosis contributes to the disorder of gut microbiota in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 4232–4250. [CrossRef]

- Behary, J.; Amorim, N.; Jiang, X.-T.; Raposo, A.; Gong, L.; McGovern, E.; Ibrahim, R.; Chu, F.; Stephens, C.; Jebeili, H.; et al. Gut microbiota impact on the peripheral immune response in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease related hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Li, A.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, L.; Yu, Z.; Lu, H.; Xie, H.; Chen, X.; Shao, L.; Zhang, R.; et al. Gut microbiome analysis as a tool towards targeted non-invasive biomarkers for early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut 2018, 68, 1014–1023. [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Sinclair, D.A.; Ellis, J.L.; Steegborn, C. Sirtuin activators and inhibitors: Promises, achievements, and challenges. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 188, 140–154. [CrossRef]

- Chandramowlishwaran, P.; Vijay, A.; Abraham, D.; Li, G.; Mwangi, S.M.; Srinivasan, S. Role of Sirtuins in Modulating Neurodegeneration of the Enteric Nervous System and Central Nervous System. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [CrossRef]

- Manjula, R.; Anuja, K.; Alcain, F.J. SIRT1 and SIRT2 Activity Control in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Du, Y.; Xue, C.; Kang, X.; Sun, C.; Peng, H.; Fang, L.; Han, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhao, C. SIRT2 Deficiency Aggravates Diet-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease through Modulating Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8970. [CrossRef]

- E Lakhan, S.; Kirchgessner, A. Gut microbiota and sirtuins in obesity-related inflammation and bowel dysfunction. J. Transl. Med. 2011, 9, 202–202. [CrossRef]

- Bayram, H.M.; Majoo, F.M.; Ozturkcan, A. Polyphenols in the prevention and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An update of preclinical and clinical studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2021, 44, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, J.; Li, D.; Ke, W.; Chen, F.; Hu, X. Targeting the gut microbiota with resveratrol: a demonstration of novel evidence for the management of hepatic steatosis. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2020, 81, 108363. [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Huang, R.; Lin, D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Huang, X.; Zheng, B.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Resveratrol Improves Liver Steatosis and Insulin Resistance in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Association With the Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, V.; Bose, C.; Sunilkumar, D.; Cherian, R.M.; Thomas, S.S.; Nair, B.G. Resveratrol as a Promising Nutraceutical: Implications in Gut Microbiota Modulation, Inflammatory Disorders, and Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3370. [CrossRef]

- Karabekir, S.C.; Ozgorgulu, A. Possible protective effects of resveratrol in hepatocellular carcinoma. 2020, 23, 71–78. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Xiao, X.; Zeng, J. Integrative evidence construction for resveratrol treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: preclinical and clinical meta-analyses. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1230783. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Li, D., Resveratrol supplement inhibited the NF-κB inflammation pathway through activating AMPKα-SIRT1 pathway in mice with fatty liver. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2016, 422, (1-2), 75-84.

- Wu, W.-Y.; Ding, X.-Q.; Gu, T.-T.; Guo, W.-J.; Jiao, R.-Q.; Song, L.; Sun, Y.; Pan, Y.; Kong, L.-D., Pterostilbene improves hepatic lipid accumulation via the MiR-34a/Sirt1/SREBP-1 pathway in fructose-fed rats. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2020, 68, (5), 1436-1446.

- Estrela, J. M.; Ortega, A.; Mena, S.; Rodriguez, M. L.; Asensi, M., Pterostilbene: biomedical applications. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences 2013, 50, (3), 65-78.

- Gómez-Zorita, S.; Fernández-Quintela, A.; Lasa, A.; Aguirre, L.; Rimando, A.M.; Portillo, M.P. Pterostilbene, a Dimethyl Ether Derivative of Resveratrol, Reduces Fat Accumulation in Rats Fed an Obesogenic Diet. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 8371–8378. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Sang, S. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of resveratrol and pterostilbene. BioFactors 2018, 44, 16–25. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; Jiang, X.; Liu, C.; Lei, L.; Li, Y.; Sheng, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; et al. SIRT1 Activator E1231 Alleviates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Regulating Lipid Metabolism. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 5052–5070. [CrossRef]

- Vidyashankar, S.; Varma, R.S.; Patki, P.S. Quercetin ameliorate insulin resistance and up-regulates cellular antioxidants during oleic acid induced hepatic steatosis in HepG2 cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2013, 27, 945–953. [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Sullivan, M.A.; Chen, W.; Jing, X.; Yu, H.; Li, F.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Quercetin ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) via the promotion of AMPK-mediated hepatic mitophagy. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2023, 120, 109414. [CrossRef]

- Ying, H.-Z.; Liu, Y.-H.; Yu, B.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Zang, J.-N.; Yu, C.-H. Dietary quercetin ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis induced by a high-fat diet in gerbils. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 52, 53–60. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, J.; Mei, G.; Chen, H.; Peng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Yao, P.; Tang, Y. Quercetin and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A review based on experimental data and bioinformatic analysis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 154, 112314. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.X.; Bae, M.; Kim, M.-B.; Lee, Y.; Hu, S.; Kang, H.; Park, Y.-K.; Lee, J.-Y. Nicotinamide riboside, an NAD+ precursor, attenuates the development of liver fibrosis in a diet-induced mouse model of liver fibrosis. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis. 2019, 1865, 2451–2463. [CrossRef]

- Longo, L.; de Castro, J.M.; Keingeski, M.B.; Rampelotto, P.H.; Stein, D.J.; Guerreiro, G.T.S.; de Souza, V.E.G.; Cerski, C.T.S.; Uribe-Cruz, C.; Torres, I.L.; et al. Nicotinamide riboside and dietary restriction effects on gut microbiota and liver inflammatory and morphologic markers in cafeteria diet–induced obesity in rats. Nutrition 2023, 110, 112019. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Bao, X.; Lou, Q.; Xie, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, S.; Guo, H.; Jiang, G.; Shi, Q. Nicotinamide riboside exerts protective effect against aging-induced NAFLD-like hepatic dysfunction in mice. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7568. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Sun, D.; Ma, Y.; Bai, Y.; Bai, X.; Liang, X.; Liang, H. Nicotinamide Riboside Ameliorates Fructose-Induced Lipid Metabolism Disorders in Mice by Activating Browning of WAT, and May Be Also Related to the Regulation of Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3920. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Chu, Y.; Nie, Q.; Zhang, J. Berberine prevents NAFLD and HCC by modulating metabolic disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 254, 108593. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, J.; Shen, T. The combination of berberine and evodiamine ameliorates high-fat diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated with modulation of gut microbiota in rats. Braz. J. Med Biol. Res. 2022, 55, e12096. [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Li, M.; Cao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhou, W.; Ji, G.; Zhang, L. Berberine Alleviates Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis Through Modulating Gut Microbiota Mediated Intestinal FXR Activation. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ionita-Radu, F.; Patoni, C.; Nancoff, A.S.; Marin, F.-S.; Gaman, L.; Bucurica, A.; Socol, C.; Jinga, M.; Dutu, M.; Bucurica, S. Berberine Effects in Pre-Fibrotic Stages of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease—Clinical and Pre-Clinical Overview and Systematic Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4201. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tian, G.; Zhuang, Z.; Chen, J.; You, N.; Zhuo, L.; Liang, B.; Song, Y.; Zang, S.; Liu, J.; et al. Berberine prevents non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-derived hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting inflammation and angiogenesis in mice. American journal of translational research 2019, 11, 2668–2682.

- Jiang, H.; Mao, T.; Sun, Z.; Shi, L.; Han, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Han, H.-X., Yinchen Linggui Zhugan decoction ameliorates high fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by modulation of SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway and gut microbiota. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13.

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Qi, H.; Gao, M.; Rong, J.; Liu, L.; Wan, Y.; et al. Tangshen formula targets the gut microbiota to treat non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in HFD mice: A 16S rRNA and non-targeted metabolomics analyses. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116405. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Li, N.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liang, Q.; Shao, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, T.; et al. Tangshen Formula Alleviates Hepatic Steatosis by Inducing Autophagy Through the AMPK/SIRT1 Pathway. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 494. [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Zhang, B.-X.; Zhang, H.-J.; Yan, M.-H.; Li, P. Experimental study of Tangshen formulain improved lipid metabolism and phenotypic switch of macrophage in db/db mice. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2014, 41, 1693–1698. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, S.; Asgary, S.; Askari, G.; Keshvari, M.; Hatamipour, M.; Feizi, A.; Sahebkar, A. Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease with Curcumin: A Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. Phytotherapy Res. 2016, 30, 1540–1548. [CrossRef]

- Amel Zabihi, N.; Pirro, M.; P Johnston, T.; Sahebkar, A., Is there a role for curcumin supplementation in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease? The data suggest yes. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2017, 23, (7), 969-982.

- Lee, D. E.; Lee, S. J.; Kim, S. J.; Lee, H.-S.; Kwon, O.-S., Curcumin ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through inhibition of O-GlcNAcylation. Nutrients 2019, 11, (11), 2702.

- Du, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, N.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, W.; Li, X. Curcumin alleviates hepatic steatosis by improving mitochondrial function in postnatal overfed rats and fatty L02 cells through the SIRT3 pathway. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 2155–2171. [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Xu, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, D. Molecular mechanism and therapeutic significance of dihydromyricetin in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 935, 175325. [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Ma, X.; Yu, F.; Xu, L.; Lang, L. Dihydromyricetin Alleviates Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Modulating Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Signaling Pathways. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 2637–2647. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yang, J.; Hu, O.; Huang, J.; Ran, L.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Dihydromyricetin Ameliorates Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease by Improving Mitochondrial Respiratory Capacity and Redox Homeostasis Through Modulation of SIRT3 Signaling. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2019, 30, 163–183. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Jin, J.; Zhan, W.; Han, T.; Wang, J. Dihydromyricetin ameliorates oleic acid-induced lipid accumulation in L02 and HepG2 cells by inhibiting lipogenesis and oxidative stress. Life Sci. 2016, 157, 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, D.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Dorfman, R.G.; et al. Downregulation of SIRT2 Inhibits Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Inhibiting Energy Metabolism. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 10, 917–927. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, Z.; Qi, B.; Bai, L. Recent Progress on the Discovery of Sirt2 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Various Cancers. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 1051–1058. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, S.G.; Eren, G. Selective inhibition of SIRT2: A disputable therapeutic approach in cancer therapy. Bioorganic Chem. 2023, 143, 107038. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, A.; Finger, C.; Morales-Scheihing, D.; Lee, J.; McCullough, L.D. Gut dysbiosis and age-related neurological diseases; an innovative approach for therapeutic interventions. Transl. Res. journal of laboratory and clinical medicine 2020, 226, 39–56. [CrossRef]

- Yamashiro, Y. Probiotics to Prebiotics and Their Clinical Use. Reference Module in Biomedical Sciences 2021.

- Manzoor, S.; Wani, S.M.; Mir, S.A.; Rizwan, D. Role of probiotics and prebiotics in mitigation of different diseases. Nutrition 2022, 96, 111602. [CrossRef]

- Upasana, Application of Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics in Maintaining Gut Health. The Indian Journal of Nutrition and Dietetics 2022.

- Yadav, M.K.; Kumari, I.; Singh, B.; Sharma, K.K.; Tiwari, S.K. Probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics: Safe options for next-generation therapeutics. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 505–521. [CrossRef]

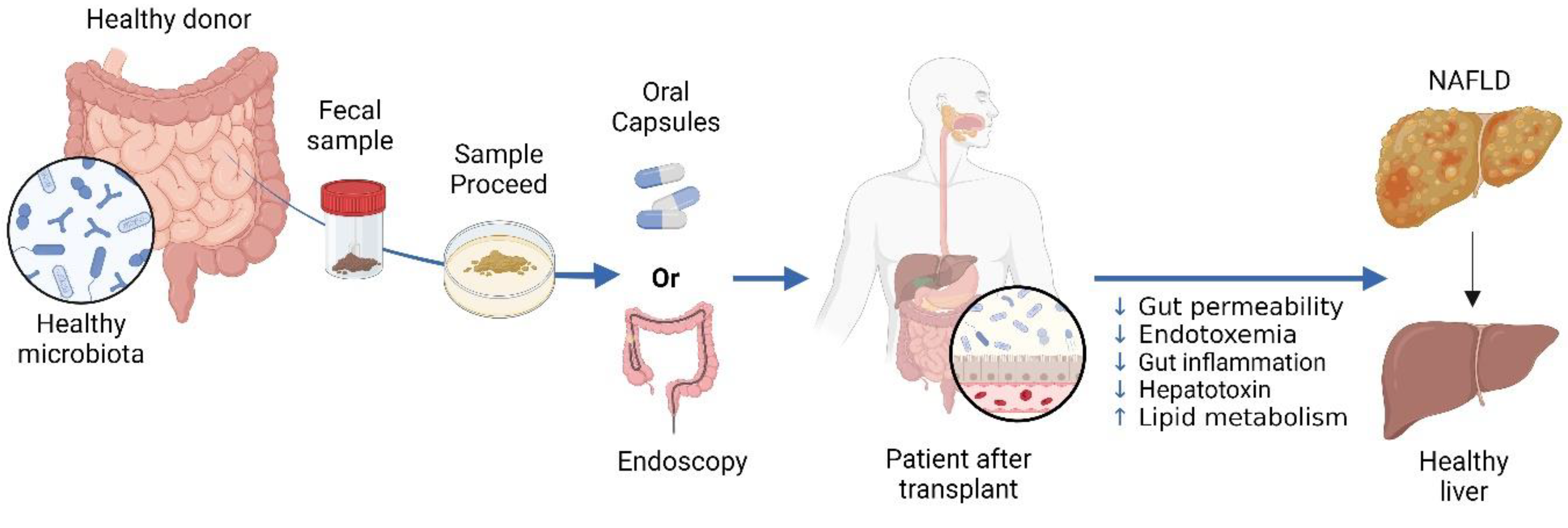

- Shao, T.; Hsu, R.; Hacein-Bey, C.; Zhang, W.; Gao, L.; Kurth, M.J.; Zhao, H.; Shuai, Z.; Leung, P.S.C. The Evolving Landscape of Fecal Microbial Transplantation. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2023, 65, 101–120. [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L.; Maurizi, V.; Rinninella, E.; Tack, J.; Di Berardino, A.; Santori, P.; Rasetti, C.; Procopio, A.C.; Boccuto, L.; Scarpellini, E. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in NAFLD Treatment. Medicina 2022, 58, 1559. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.-X.; Cheng, S.-L.; Liu, Y.-H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, N.-N.; Li, Z. Fecal microbiota transplantation for treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Mechanism, clinical evidence, and prospect. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 833–842. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).