Submitted:

01 February 2025

Posted:

03 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Background. Shift workers are at increased risk for insomnia or shift work disorder. The standard treatment (cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia) is challenging for this group. Although there are new promising approaches, they are still considered inadequate. Aims and objectives. For this study, a tailored treatment was developed that replaces regularity interventions with methods from other disorders such as anxiety or depression. This approach is also intended to shift the focus away from disturbed sleep. Methods. A randomized controlled trial (RCT, completer analysis) was conducted. Therefore, linear mixed models were utilized to compare two active conditions (treatment as usual vs. tailored therapy) at three measurement points (pre-, post-treatment, 3-month follow-up). Primary outcomes are sleep quality, insomnia severity, sleep onset latency, and total sleep time. Secondary outcomes are anxiety, depression, tension, concern, emotional instability. Non-inferiority or equivalence tests were also performed. Results. The newly developed treatment approach is equivalent to standard care. Both resulted in significant and stable improvements in all variables. Thus, only the main effect across measurement points is significant, not the group or the interaction. Outlook. Attrition rates and compliance should be considered in further studies and the treatment should be revised according to these results. The approach of improving sleep with implicit interventions should be pursued further, as it seems well suited to shift workers and their specific needs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Method and Design

2.2. Sampling and Participants

2.3. Sampling and Procedure

2.4. Setting and Conditions of Implementation

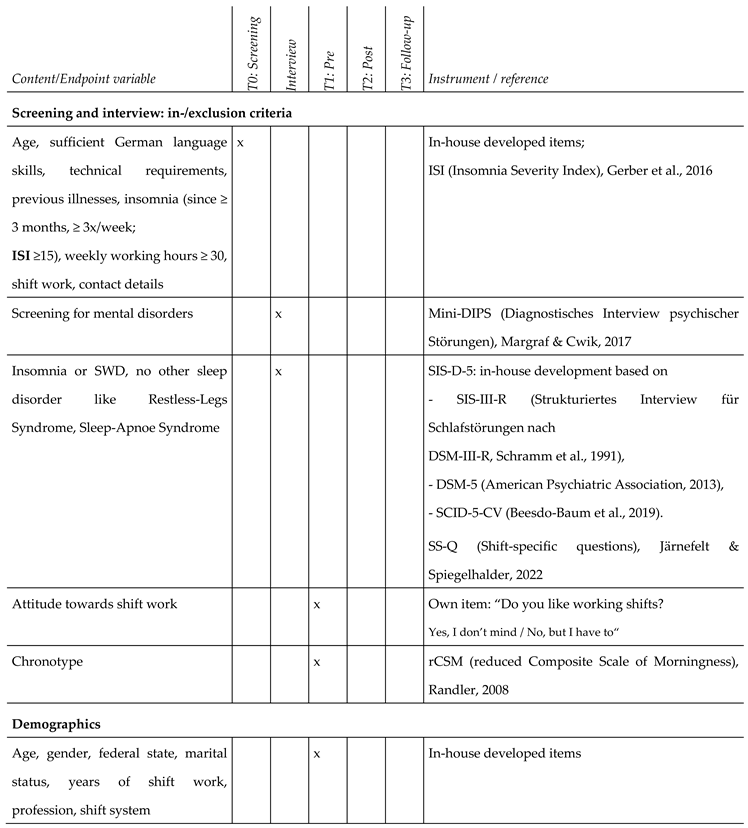

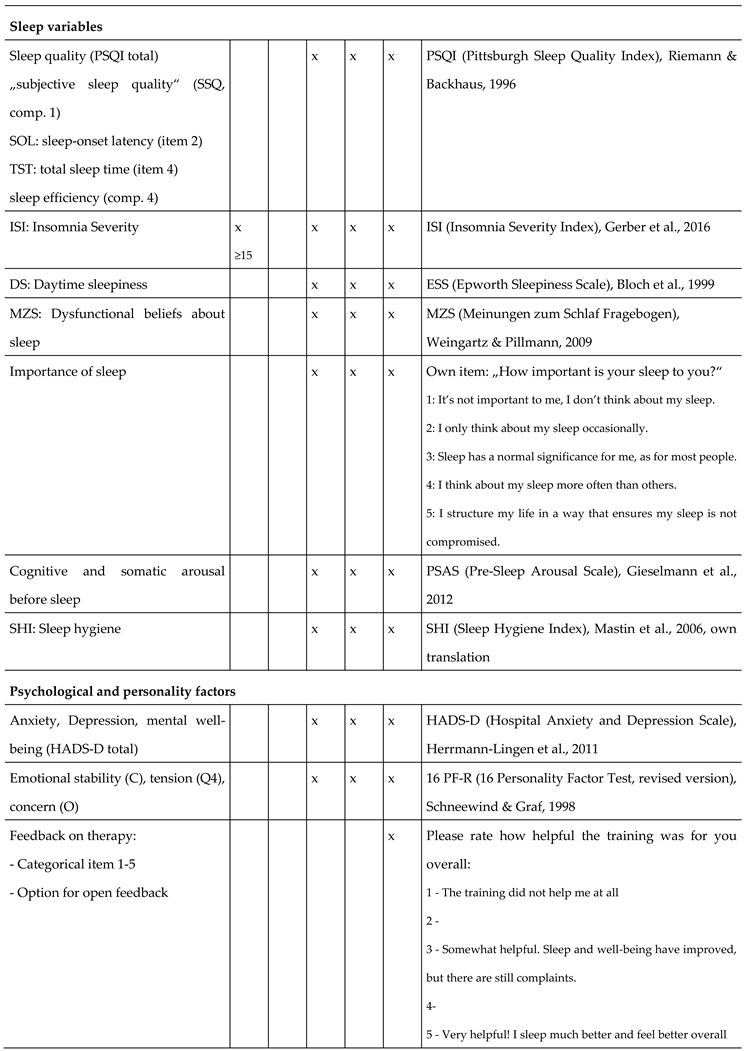

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Treatment Manuals

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

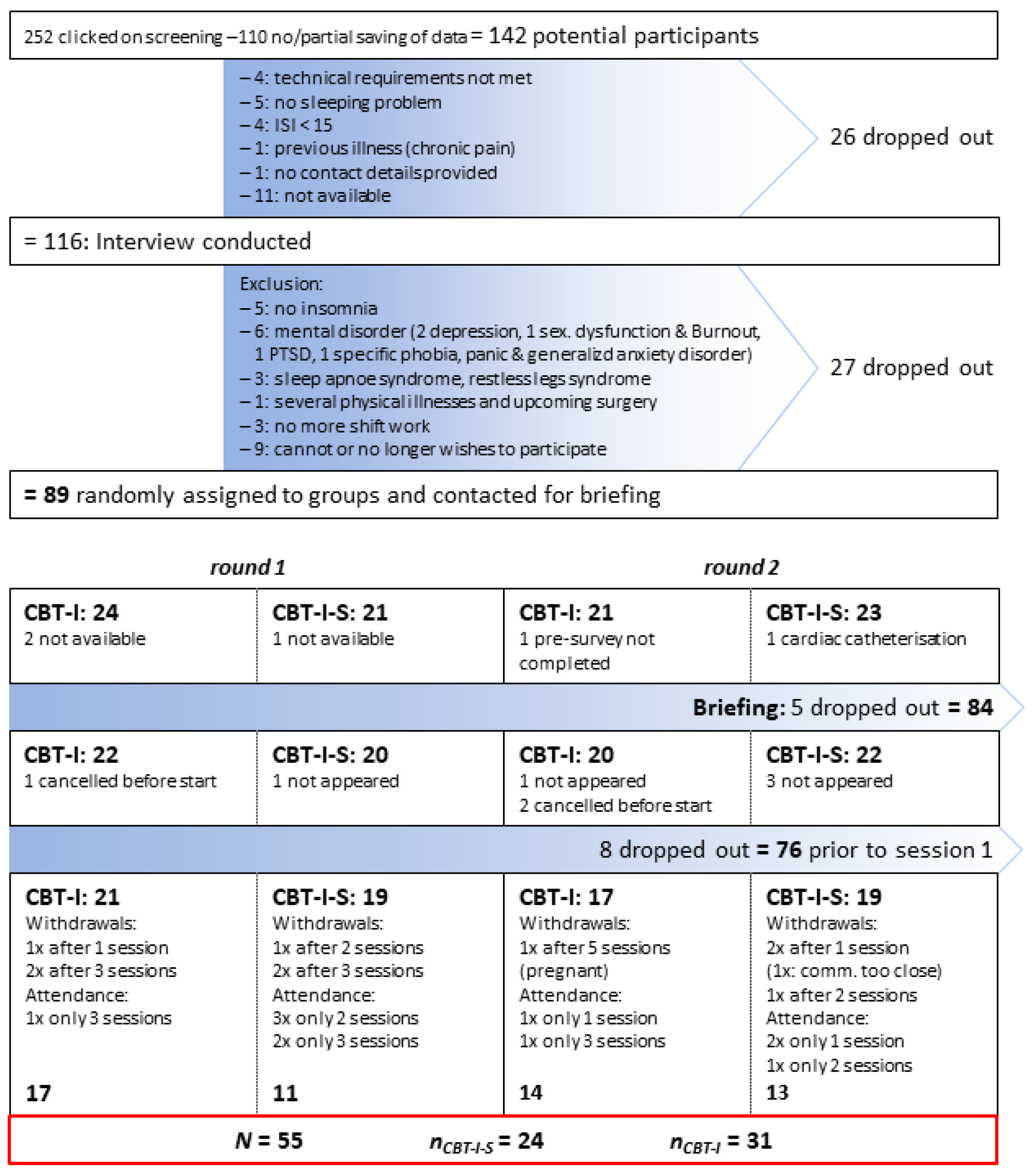

3.1. Sample

3.2. Power

3.3. A Priori Group Differences

3.4. Waiting List Control Group

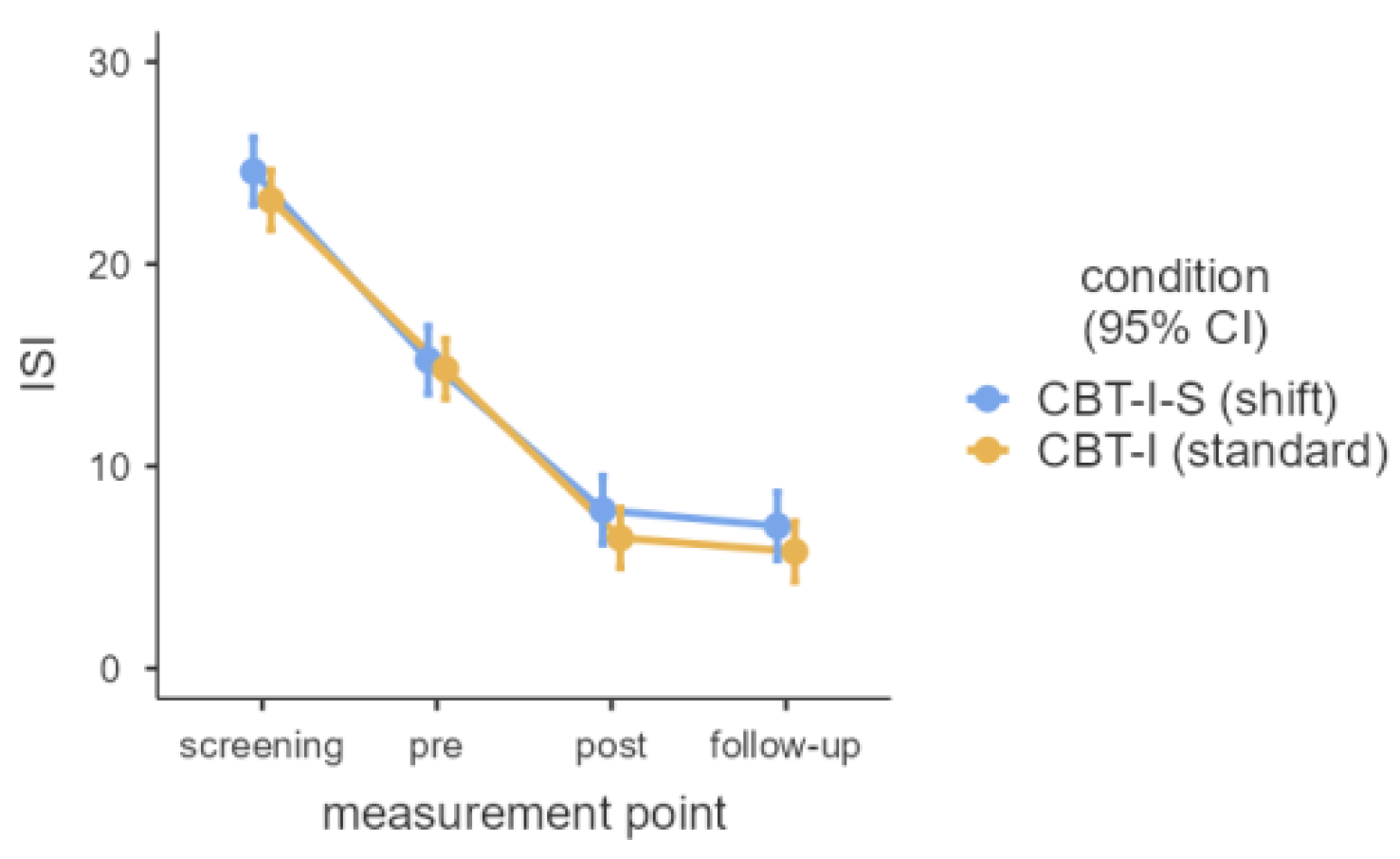

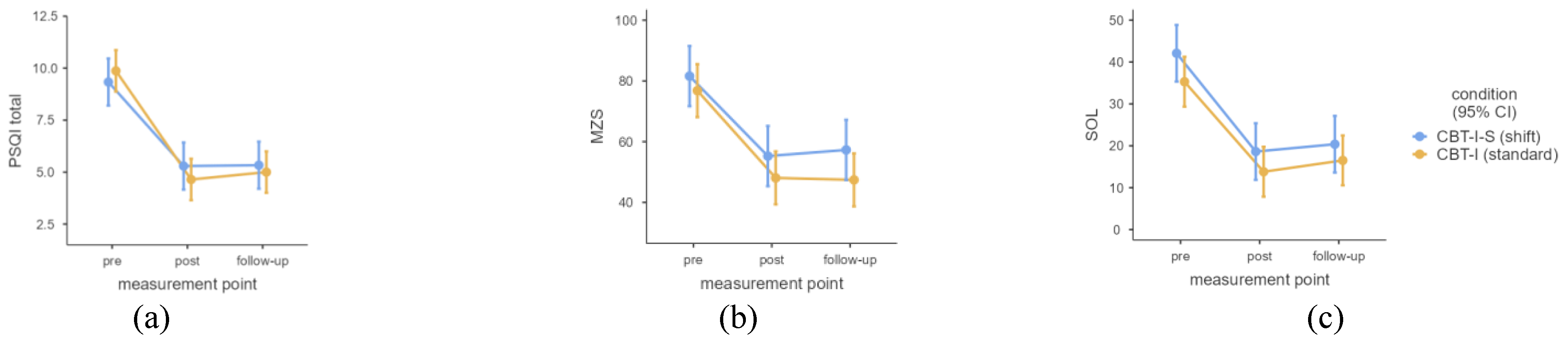

3.5. Linear Mixed Models

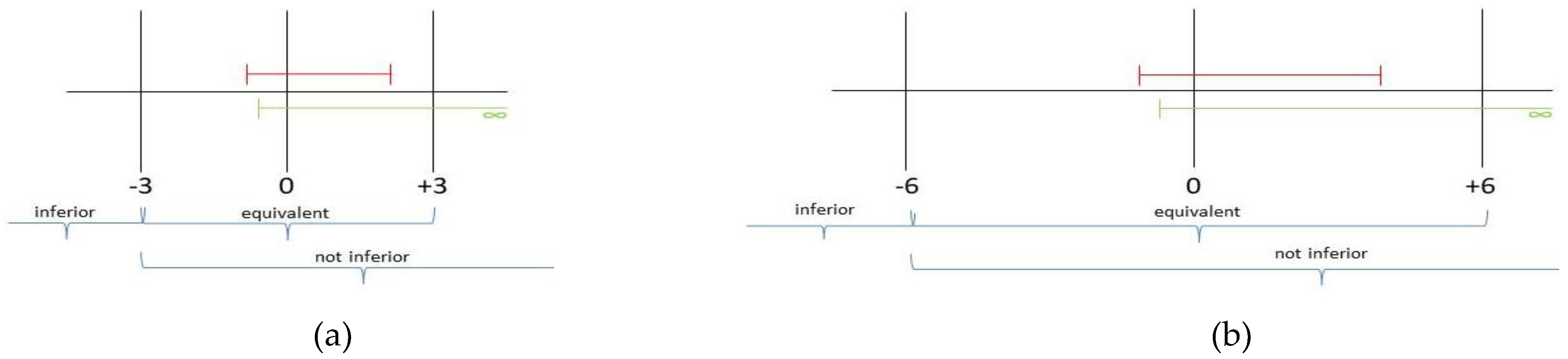

3.6. Non-Inferiority/Equivalence Tests

3.7. Remission Rates

3.8. Feedbacks

3.9. Dropout Rates

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Strengths

5. Conclusions

5.1. Outlook

Supplementary Materials

References

- Åkerstedt, T.; Sallinen, M.; Kecklund, G. Shiftworkers’ attitude to their work hours, positive or negative, and why? International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 2022, 95, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM, 2014). International Classification of Sleep Disorders, third edition (ICSD-3). American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA, 2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition, DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association.

- Axelsson, J.; Åkerstedt, T.; Kecklund, G.; Lowden, A. Tolerance to shift work—how does it relate to sleep and wakefulness? International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 2004, 77, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baglioni, C., Espie, C. A., & Riemann, D. (Eds.). (2022). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) across the life span. Guidelines and clinical protocols for health professionals. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Bastille-Denis, E.; Lemyre, A.; Pappathomas, A.; Roy, M.; Vallières, A. Are cognitive variables that maintain insomnia also involved in shift work disorder? Sleep Health 2020, 6, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, E., & Margraf, J. (2002). Generalisierte Angststörung. Ein Therapieprogramm. Beltz.

- Beesdo-Baum, K., Zaudig, M., & Wittchen, H.-U. (Eds.). (2019). SCID-5-CV. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-5R-Störungen – Klinische Version. Deutsche Bearbeitung des Stuctured Clinical Interview for CDM-5 R Disorders – Clinician Version von Michael B. First, Jane B. Williams, Rhonda S. Hogrefe.

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, R., Schöller, F., & Weeß, H.-G. (2020). Therapie-Tools Schlafstörungen. Beltz.

- Bloch, K.E.; Schoch, O.D.; Zhang, J.N.; Russi, E.W. German version of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases 1999, 66, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booker, L.A.; Sletten, T.L.; Barnes, M.; Alvaro, P.; Collins, A.; Chai-Coetzer, C.L.; McMahon, M.; Lockley, S.W.; Rajaratnam SM, W.; Howard, M.E. The effectiveness of an individualized sleep and shift work education and coaching program to manage shift work disorder in nurses: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of clinical sleep medicine 2022, 18, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S. , Xin, B., Yu, Y., Peng, C., Zhu, C., Deng, M., Gao, X., Chu, J., & Liu, T Improvement of sleep quality in isolated metastatic patients with spinal cord compression after surgery. World Journal of Surgical Oncology 2023, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Drake, C.L. Psychological impact of shift work. Current Sleep Medicine Reports 2018, 4, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Constantino, M. J. , Vîslă, A., Coyne, A. E., & Boswell, J. F. A meta-analysis of the association between patients’ early treatment outcome expectation and their posttreatment outcomes. Psychotherapy 2018, 55, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crönlein, T. (2013). Primäre Insomnie. Ein Gruppentherapieprogramm für den stationären Bereich. Hogrefe.

- Ell, J.; Brückner, H.A.; Johann, A.F.; Steinmetz, L.; Güth, L.J.; Feige, B.; Järnefelt, H.; Vallières, A.; Frase, L.; Domschke, K.; Riemann, D.; Lehr, D.; Spiegelhalder, K. Digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia reduces insomnia in nurses suffering from shift work disorder: A randomised-controlled pilot trial. Journal of Sleep Research 2024, 33, e14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espie CA (2022) Standard CBT-I protocol for the treatment of insomnia disorder In, C. Baglioni, C. A. Espie, D. Riemann (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioural therapy für insomnia (CBT-I) across the life span. Guidelines and clinical protocols for health professionals (pp. 19–41). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Espie, C.A.; Kyle, S.D.; Williams, C.; Ong, J.C.; Douglas, N.J.; Hames, P.; Brown JS, L. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep 2012, 35, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espie, C.A.; Broomfield, N.M.; MacMahon, K.M.; Macphee, L.M.; Taylor, L.M. The attention-intention-effort pathway in the development of psychophysiologic insomnia: a theoretical review. Sleep medicine reviews 2006, 10, 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F. , Buchner, A., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. G*Power3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 175–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Feld, A. & Rudy, J. M. (2017). Coaching der Positiven Psychologie. Manual für Coaches [Unpublished manual]. Paris-Lodron-Universität Salzburg.

- Frank, J. D. (1961). Persuasion and healing: A comparative study of psychotherapy. John Hopkins University Press.

- Gerber, M.; Lang, C.; Lemola, S.; Colledge, F.; Kalak, N.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Pühse, U.; Brand, S. Validation of the German version of the insomnia severity index in adolescents, young adults and adult workers: results from three cross-sectional studies. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieselmann, A.; de Jong-Mayer, R.; Pietrowsky, R. Kognitive und körperliche Erregung in der Phase vor dem Einschlafen. Die deutsche Version der Pre-Sleep Arousal Scale (PSAS). Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie 2012, 41, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünberger, T.; Höhn, C.; Schabus, M.; Laireiter, A.-R. Insomnia in Shift Workers: Which trait and state characteristics could serve as foundation for developing an innovative therapeutic approach? Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünberger, T.; Höhn, C.; Schabus, M.; Laireiter, A.-R. Efficacy study comparing a CBT-I developed for shift workers (CBT-I-S) to standard CBT-I (cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia) on sleep onset latency, total sleep time, subjective sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness: study protocol for a parallel group randomized controlled trial with online therapy groups of seven sessions each. Trials 2024, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, A.G. A cognitive model of insomnia. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2002, 40, 869–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmerich, W. (2016). StatistikGuru: Rechner zur Adjustierung des α-Niveaus. Retrieved from https://statistikguru.de/rechner/adjustierung-des-alphaniveaus.html.

- Herrmann-Lingen, C., Buss, U., & Snaith, R. P. (2011). Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Deutsche Version (HADS-D) (Vol. 3). Huber.

- IBM Corp (2023). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 29.0.2.0. IBM Corp.

- Järnefelt, H. ; Spiegelhalder K (2022) CBT-IProtocols for Shift Workers Health Operators In, C. Baglioni, C. A. Espie, & D. Riemann (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) across the life span. Guidelines and clinical protocols for health professionals (pp. 126–132). John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Järnefelt, H. , Härmä, M., Sallinen, M., Virkkala, J., Paajanen, T. Martimo, K.-P., & Hublin, C. Cognitive behavioural therapy interventions for insomnia among shift workers: RCT in an occupational health setting. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 2020, 93, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järnefelt, H.; Lagerstedt, R.; Kajaste, S.; Sallinen, M.; Savolainen, A.; Hublin, C. Cognitive behavioral therapy for shift workers with chronic insomnia. Sleep medicine 2012, 13, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E. H. , Hong, Y., Kim, Y., Lee, S., Ahn, Y., Jeong, K. S., Jang, T.-W., Lim, H., Jung, E., Shift Work Disorder Study Group, Chung, S., & Suh, S. The development of a sleep intervention for firefighters: The FIT-IN (Firefighter’s Therapy for Insomnia and Nightmares) Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 8738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanis, A.; Demolder, S.; Papadopoulos, D.; Testelmans, D.; Buyse, B. Recovery from shift work. Frontiers in Neurology 2023, 14, 1270043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhof, G.A. Shift work and sleep disorder comorbidity tend to go hand in hand. Chronobiology International 2018, 35, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margraf, J., & Cwik, J. C. (2017). Mini-DIPS Open Access: Diagnostisches Kurzinterview bei psychischen Störungen. Forschungs- und Behandlungszentrum für psychische Gesundheit, Ruhr-Universität Bochum. [CrossRef]

- Mastin, D.F.; Bryson, J.; Corwyn, R. Assessment of sleep hygiene using the Sleep Hygiene Index. Journal of behavioral medicine 2006, 29, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, T., & Paterok, B. (2010). Schlaftraining. Ein Therapiemanual zur Behandlung von Schlafstörungen (2., überarbeitete Auflage). Hogrefe.

- Pagano, R. R. (2010). Understanding statistics in the behavioral sciences (9th ed.). Thomson Wadsworth.

- Pitschel-Walz, G., Bäuml, J., & Kissling W. (2003). Psychoedukation bei Depressionen. Manual zur Leitung von Patienten- und Angehörigengruppen. Urban & Fischer Verlag.

- Pollmächer, T., Wetter, T. C., Bassetti, C. L. A., Högl, B., Randerath, W., Wiater, A. (Eds.). (2020). Handbuch Schlafmedizin. Elsevier.

- Randler, C. Psychometric properties of the German version of the Composite Scale of Morningness. Biological Rhythm Research 2008, 39, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, D.; Guiard, V. The robustness of parametric statistical methods. Psychology Science 2004, 46, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Reinberg, A.; Ashkenazi, I. Internal desynchronization of circadian rhythms and tolerance to shift work. Chronobiology International 2008, 25, 625–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.C.; Sweetman, A.; Crowther, M.E.; Paterson, J.L.; Scott, H.; Lechat, B.; Wanstall, S.E.; Brown, B.W.; Lovato, N.; Adams, R.J.; Eastwood, P.R. Is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi) efficacious for treating insomnia symptoms in shift workers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep medicine reviews 2023, 67, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemann, D., & Backhaus, J. (1996). Behandlung von Schlafstörungen. Psychologie Verlags Union.

- Saksvik, I.B.; Bjorvatn, B.; Hetland, H.; Sandal, G.M.; Pallesen, S. Individual differences in tolerance to shift work – a systematic review. Sleep medicine reviews 2011, 15, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharfenstein, A., & Basler, H.-D. (2004a). Schlafstörungen. Auf dem Weg zu einem besseren Schlaf. Schlaftagebuch. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Scharfenstein, A., & Basler, H.-D. (2004b). Schlafstörungen. Auf dem Weg zu einem besseren Schlaf. Trainerhandbuch. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Schaub, A., Roth, E., & Goldmann, U. (2013). Kognitiv-psychoedukative Therapie zur Bewältigung von Depression. Ein Therapiemanual (2. Aufl.). Hogrefe.

- Schneewind, K. A., & Graf, J. (1998). Der 16-Persönlichkeits-Faktoren-Test, revidierte Fassung. 16 PF-R – deutsche Ausgabe des 16 PF Fifth Edition – Testmanual. Hans Huber.

- Schramm, E., Hohagen, F., Graßhoff, U., & Berger, M. (1991). Strukturiertes Interview für Schlafstörungen nach DSM-III-R. Beltz Test GmbH.

- Shriane, A.E.; Rigney, G.; Ferguson, S.A.; Bin, Y.S.; Vincent, G.E. Healthy sleep practices for shift workers: consensus sleep hygiene guidelines using a Delphi methodology. Sleep 2023, 46, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegelhalder, K., Backhaus, J., & Riemann, D. (2011). Schlafstörungen (2. überarbeitete Auflage). Hogrefe.

- Takano, Y.; Ibata, R.; Machida, N.; Ubara, A.; Okajima, I. Effect of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Medicine Reviews 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teismann, T., Hanning, S., Brachel, R.v., & Willutzki, U. (2012). Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie depressiven Grübelns. Springer.

- The jamovi project (2022). jamovi. (Version 2.3). Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org.

- Tout, A. F., Tang, N. K. Y., Sletten, T. L., Toro, C. T., Kershaw, C., Meyer. C., Rajaratnam, S. M. W., & Moukhtarian, T. R. (2024). Current sleep interventions for shift workers: a mini review to shape a new preventative, multicomponent sleep management programme. Frontiers in Sleep 3. [CrossRef]

- Vallières, A.; Pappathomas, A.; Garnier, S.B.; Mérette, C.; Carrier, J.; Paquette, T.; Bastien, C.H. Behavioural therapy for shift work disorder improves shift workers’ sleep, sleepiness and mental health: A pilot randomised control trial. Journal of Sleep Research 2024, 33, e14162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanttola, P. , Puttonen, S., Karhula, K., Oksanen, T., & Härmä, M. Prevalence of shift work disorder among hospital personnel: A cross-sectional study using objective working hour data. Journal of sleep research 2020, 29, e12906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingartz, S.; Pillmann, F. Meinungen-zum-Schlaf-Fragebogen. Deutsche Version der DBAS-16 zur Erfassung dysfunktionaler Überzeugungen und Einstellungen zum Schlaf. Somnologie 2009, 13, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellek, S.; Blettner, M. Klinische Studien zum Nachweis von Äquivalenz oder Nichtunterlegenheit. Teil 20 der Serie zur Bewertung wissenschaftlicher Publikationen. [Establishing equivalence or non-inferiority in clinical trials—part 20 of a series on evaluation of scientific publications]. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2012, 109, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, R. R. (2012). Introduction to robust estimation and hypothesis testing (3rd ed.). Statistical modeling and decision science; Academic Press.

- Yang, M.; Morin, C.M.; Schaefer, K.; Wallenstein, G.V. Interpreting score differences in the Insomnia Severity Index: using health-related outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Current Medical Research and Opinion 2009, 25, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sessions | Contents | Quoted / based on / adapted from …: |

| After pre-survey | Sleep diary (to keep until the last session) | Scharfenstein & Basler, 2004a |

| 1. | Introduction to the programme, psycho education, implementation of relaxation method |

Binder et al., 2020, pp. 49–52, 75–78, 95–96; Espie, 2022; Crönlein, 2013 |

| 2. | Introduction to sleep restriction, calculation of the first sleep window |

Müller & Paterok, 2010, pp. 87–97 |

| 3. | Deepen sleep restriction, repeat relaxation | Müller & Paterok, 2010, pp. 101–103; Espie, 2022 |

| 4. | Stimulus control, adaptation of the sleep window, repeat relaxation |

Espie, 2022, pp. 22–25 |

| 5. | Sleep hygiene, sleep hygiene check; adaptation of the sleep window, repeat relaxation |

Binder, et al., 2020, pp. 135–141; Espie, 2022 |

| 6. | Cognitive restructuring of dysfunktional thoughts about sleep |

Binder et al., 2020, pp. 174–177 |

| 7. | Sharing experiences, reviewing sleep diaries, relapse prevention, goodbye |

Scharfenstein & Basler, 2004b, pp. 189–190 |

| Sessions | contents | Partly in-house development, partly quoted / based on / adapted from …: |

| After pre-survey | Reading material: Psychoeducation on healthy sleep, insomnia, and treatment options | AASM, 2014; Baglioni et al., 2022; Crönlein, 2013; Espie et al., 2006; Pollmächer et al., 2020; Müller & Paterok, 2010; Scharfenstein & Basler; 2004b; Kerkhof, 2018 |

| 1. | Introduction to therapy Discussion of the reading material Derivation of the therapeutic rationale Effects of attitudes towards shift work |

Crönlein, 2013; Harvey, 2002; Espie et al., 2006; Åkerstedt et al., 2022; Axelsson et al., 2004 |

| 2. | Presentation and discussion of the concept of „shift work tolerance“; Current recommendations for shift workers; positive activities (e.g., social, family, etc.); daily structure for each shift (early, late, night shift): recognize opportunities ‘despite shift work’; find an individual relaxation method |

Reinberg & Ashkenazi, 2008; Saksvik et al., 2011; Shriane et al., 2023; Järnefelt & Spiegelhalder, 2022; Schaub et al., 2013; Espie, 2022 |

| 3. | Central methodologies are employed: Systematic problem solving, acceptance, resource orientation. |

Teismann et al., 2012 |

| 4. | (Depressive) rumination: Gratitude-/Happiness-Diary; grumbling/worrying stop; relaxation picture |

Teismann et al., 2012; Feld & Rudy, 2017; Spiegelhalder et al., 2011 |

| 5. | Anxiety / concern: decatastrophising, reality check |

Becker & Margraf, 2002 |

| 6. | Mood: positive activities, success spoilers, ABC-scheme, cognitive restructuring of dysfunctional (depressive) thoughts |

Pitschel-Walz et al., 2003; Schaub et al., 2013 |

| 7. | Sharing experiences, emergency kit, relapse prevention, feedback and goodbye | Scharfenstein & Basler, 2004b |

| Variable | Measurement point | Condition | Measurement point * Condition | ||||||

| F(2, 106) | p | η2partial | F(1, 53) | p | η2partial | F(2, 106) | p | η2partial | |

| SSQ | 51.86 | .003 | 0.49 | 0.30 | .707 | - | 1.60 | .336 | - |

| SOL | 56.16 | .003 | 0.51 | 2.00 | .298 | 0.21 | .843 | ||

| TST | 39.04 | .003 | 0.42 | 0.18 | .742 | 1.33 | .408 | ||

| Sleep efficiency | 40.86 | .003 | 0.44 | 0.02 | .904 | 1.79 | .305 | ||

| PSQI total | 80.24 | .003 | 0.60 | 0.06 | .843 | 1.10 | .470 | ||

| Importance of sleep | 7.36 | .003 | 0.12 | 0.01 | .923 | 0.71 | .633 | ||

| MZS | 64.12 | .003 | 0.55 | 1.57 | .341 | 0.42 | .742 | ||

| ISI total (3t) | 135.02 | .003 | 0.72 | 1.18 | .414 | 0.39 | .742 | ||

| ISI total (4t) (df = 3/159 rsp. 1/53) | 399.96 | .003 | 0.88 | 1.68 | .336 | 0.32 | .843 | ||

| ESS | 25.87 | .003 | 0.33 | 0.25 | .712 | 2.54 | .174 | ||

| PSAS soma | 6.50 | .006 | 0.11 | 2.49 | .225 | 3.56 | .080 | ||

| PSAS cogn | 29.69 | .003 | 0.36 | 2.59 | .219 | 1.61 | .336 | ||

| PSAS total | 22.62 | .003 | 0.30 | 2.98 | .180 | 3.19 | .108 | ||

| SHI | 21.23 | .003 | 0.29 | 6.29 | .041 | 0.11 | 0.60 | .683 | |

| HADS-A | 20.10 | .003 | 0.28 | 0.27 | .711 | 2.55 | .174 | ||

| HADS-D | 15.91 | .003 | 0.23 | 0.59 | .592 | 3.00 | .125 | ||

| HADS total | 26.25 | .003 | 0.33 | 0.50 | .633 | 4.03 | .055 | ||

| 16-PF: C emo. Stab. | 7.29 | .003 | 0.12 | 1.11 | .424 | 1.03 | .492 | ||

| 16-PF: Q4 tension | 5.91 | .012 | 0.10 | 0.35 | .683 | 5.42 | .017 | 0.09 | |

| 16-PF: O concern | 8.81 | .003 | 0.14 | 1.23 | .408 | 2.58 | .174 | ||

| Screening (T0) | Pre (T1) | Post (T2) | Follow-up (T3) | |||

| ISI <15: subthreshold clinical insomnia | CBT-I-S (24) | 0 (0%) | 11 (45.83%) | 22 (91.67%) | 22 (91.67%) | |

| CBT-I (31) | 0 (0%) | 15 (48.39%) | 28 (90.32%) | 30 (96.77%) | ||

| ISI < 8: no clinically significant insomnia | CBT-I-S (24) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.17%) | 12 (50.00%) | 17 (70.83%) | |

| CBT-I (31) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.23%) | 22 (70.97%) | 22 (70.97%) | ||

| Difference ≥ 6 T0-T1 | CBT-I-S (24) | 21 (87.50%) | ||||

| CBT-I (31) | 26 (83.87%) | |||||

| Difference ≥ 6 T1-T2 | CBT-I-S (24) | 17 (70.83%) | ||||

| CBT-I (31) | 25 (80.65%) | |||||

| Difference ≥ 6 T2-T3 | CBT-I-S (24) | 2 (8.33%) | ||||

| CBT-I (31) | 2 (6.45%) | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).