1. Introduction

Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) elaborates on the Education for All goals and education-related Millennium Development Goals, emphasising the educational requirements of a sustainable society and urging the global community to 'ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all' (United Nations, 2015)[

1]. Since the dawn of human education, the evolution of information and communication technologies (ICT) has played a pivotal role in enhancing the sustainability of education, serving as a crucial catalyst for inclusivity, fairness, and sustainability[

2]. As human society enters the 21st century, information and communication technology (ICT) is developing acceleratedly. The genesis of innovation is rooted in human agency, with human capital within the workforce assuming a pivotal role[

3].In the contemporary knowledge economy, characterised by perpetual transformation, information and communication technologies (ICT) have emerged as pivotal drivers of organisational competitiveness and innovation. The integration of ICT into various facets of the education sector has been a gradual process, encompassing traditional textbook printing technologies, modern internet technologies, mobile devices, and the latest artificial intelligence-generated content (AIGC). These technological advancements have profoundly transformed knowledge acquisition, driving fundamental educational model changes. These developments underscore the imperative for academic institutions to prioritise sustainability and to continue nurturing and cultivating the growth of these transformative technologies.

The concept of Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) represents a captivating example of cutting-edge technological development. This technology enables the automated generation of content, including images, texts and videos, by users through the utilisation of artificial intelligence according to their specific requirements [

4]. With the emergence of ChatGPT developed by OpenAI, artificial intelligence has entered the AIGC era and is also profoundly changing the field of education[

5]. The advent of AIGC has the potential to bring about unprecedented opportunities for education, including automated assessment and Personalized learning path design. Furthermore, it can reshape how teachers and students interact, thereby inspiring students' creativity and critical thinking skills[

6]. For instance, natural language processing (NLP) enables AIGC technology to comprehend and respond to students' inquiries, offer instantaneous feedback, and facilitate the mastery of knowledge points. Concurrently, AIGC can adapt the content and complexity of instruction in real-time, contingent on students' learning behaviour data, thereby ensuring that each student receives a Personalized learning experience[

7].

The advent of advanced information technology, particularly the integration of artificial intelligence (AIGC) technology, has precipitated a paradigm shift in the realm of higher education reform in China. The Personalized learning paradigm, driven by these technological advancements, is emerging as a pivotal direction in the ongoing transformation of the educational landscape[

8]. Intelligent education platforms, exemplified by DeepSeek, are instrumental in evolving a novel paradigm that integrates classroom teaching and independent learning. This integration is facilitated by adaptive learning path planning and knowledge graph construction. The present study focuses on the student population in Chinese universities, exploring the role and challenges of utilising AIGC-driven Personalized learning in promoting educational sustainability. This sustainability encompasses educational inclusiveness, fairness and quality. The study examines students' attitudes towards using AIGC-driven Personalized learning, their expectations for the future of AIGC-driven Personalized learning, and the challenges that university students will face when using AIGC-driven Personalized learning.

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. AIGC Technology Overview

The development of artificial intelligence-generated content (AIGC) as a disruptive technology can be traced back to the 1950s when the concept of artificial intelligence was in its infancy[

9]. The accelerated evolution of AIGC technology experienced a notable surge during the early years of the 21st century, with substantial advancements achieved in the preceding decade[

10]. A considerable amount of investment in research and development has been directed towards exploring the potential of AIGC applications by research institutions and companies both domestically and internationally. Prominent technology companies, including Microsoft, Google, and Meta, and Chinese corporations such as Baidu, Tencent, Alibaba, and Huawei, are engaged in this field significantly [

11]. The advent of deep learning algorithms, most notably those embodied by generative adversarial networks (GANs), which have been proposed and iteratively updated since 2014, has precipitated a paradigm shift within the field[

12].

According to the Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) White Paper, published by the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, the ideal AIGC system must possess strong semantic understanding capabilities, the capacity to acquire logical knowledge and abstract learning, and a substantial language model that can be employed across a range of tasks. This will be of significant value to various cognitive applications[

13]. Concurrently, numerous documents underscore that AIGC has undergone a progression of incremental 'innovation', commencing with rudimentary 'emulation', mirroring artificial intelligence's evolution from 'simulation' to 'creation'[

14,

15,

16,

17]. Moreover, academic research into AIGC is expanding, encompassing the development of AIGC technology and exploring its social impact and ethical implications[

18].

In recent years, there has been a marked increase in the volume of research literature in AIGC[

19], indicating that this field is becoming one of the hotspots in academia. For example, there has been a surge in the number of annual preprints published on arXiv under the computer science>artificial intelligence (cs.AI) category[

20]; this is indicative of the elevated level of interest among researchers in this field of enquiry. Concurrently, research on AIGC is no longer confined to content generation in a single modality but is migrating towards multimodality.[

21],In essence, it integrates diverse forms of content, including text, images, audio, and video, to produce more sophisticated and varied content. Despite the significant advancements in AIGC technology, ensuring the authenticity and compliance of generated content and preventing disinformation and abuse remain crucial challenges that necessitate attention in future developments[

22].

As referenced in the preceding literature.[

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]A thorough review of the extant literature reveals that AIGC represents not merely a technological innovation but a paradigm shift in content creation. This transformation has not only altered the modus operandi of content production but has also profoundly influenced various facets of society. Nevertheless, as AIGC technology finds widespread application, related ethical and regulatory concerns are set to assume an increasingly prominent role. Consequently, there is an urgent need to enhance regulatory frameworks and technological mechanisms designed to ensure the optimal development of AIGC technology. Future research will continue to concentrate on improving the performance of AIGC systems, expanding application scenarios, and addressing ethical and social issues.

1.1.2. Educational Sustainability Research

Education sustainability, designated as the fourth sustainable development goal (SDG 4) in the United Nations 2030 Agenda, provides inclusive and equitable quality education and promotes lifelong learning opportunities for all[

1]. This goal underscores the significance of fundamental education, encompassing vocational, higher, and adult education, among other levels. It places a pronounced emphasis on the eradication of gender and wealth disparities. Despite some progress towards achieving SDG 4 globally, the pandemic has exerted an unparalleled impact on education systems, precipitating a substantial surge in the loss of educational resources across numerous countries. This phenomenon is particularly deleterious to already marginalised student demographics. To address these challenges, the international community must take more proactive and effective measures to accelerate the achievement of SDG 4. From a Chinese perspective, the country has responded positively to the global call, as evidenced by the 'Modernising Education in China 2035' initiative[

24]. The proposal clearly outlines the utilisation of teaching what is learned and lifelong benefits as pivotal criteria for evaluating the advancement of education. It demonstrates a commitment to establishing an educational system that can accompany individuals throughout their lives, providing diverse learning opportunities and high-quality educational resources. Furthermore, the Chinese government recognises the strategic importance of higher education for the country's and society's long-term development. Consequently, it is continually exploring ways to promote the sustainable development of higher education through optimising resource allocation and strengthening the construction of the teaching staff. The development of information technology has led to digital transformation becoming one of the key factors in promoting educational reform. This helps to overcome the limitations of time and space, allowing more people to access high-quality teaching services[

25].

Conversely, specific literary works have been observed to[

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]; higher education has been identified as indispensable in achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) and addressing broader global challenges. As the primary institutions for knowledge creation and dissemination, universities must actively resolve environmental issues, social inequality, and related difficulties [

31]. Nevertheless, it is necessary to cultivate a new generation of students who possess critical thinking skills and the capacity for innovation to respond to the demands of a rapidly changing world. However, this process is impeded by factors such as a paucity of financial resources and inadequate infrastructure. Particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, educational institutions frequently lack fundamental teaching facilities, including drinking water, electricity supplies, computer equipment and internet access[

32].

Chinese and international research has fully recognised the urgency and complexity of education sustainability. Future work should focus on the following areas: first, further improvement to the relevant policy framework to ensure that all children receive a good start in life[

33]; Secondly, more significant investment in teacher training is recommended to enhance their professionalism and service awareness[

34]; Thirdly, emerging technologies are being utilised to expand the boundaries of education, particularly in the development of Personalized solutions for the specific requirements of remote areas[

35]; Fourthly, the cross-departmental collaboration mechanism must be strengthened to establish a joint force that can promote improvements in education quality and social progress[

36].In summary, we can only make significant progress towards developing a more inclusive, equitable and productive education system through concerted action across all sectors of society.

1.1.3. Research on the Application of AIGC Technology in Educational Sustainability

Despite the remarkable progress of AIGC technology worldwide, the application of this technology in education, especially in promoting educational sustainability (e.g. Personalized learning to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4)), has been relatively understudied. Current research has paid little attention to how AIGC can narrow the educational gaps caused by geographical and economic differences and ensure that all students can benefit from high-quality educational resources. Moreover, extant research has been deficient in addressing potential negative ramifications of AIGC, including concerns regarding the authenticity of content and the diminution of students' capacity for independent thinking. Additionally, existing solutions are inadequate in comprehensively addressing salient issues pertinent to the educational implementation of AIGC, such as privacy protection and technology ethics.

Following the preceding background analysis, the role and challenges of AIGC-driven Personalized learning in promoting educational sustainability have become an issue worthy of in-depth research. Firstly, AIGC can support the goals of SDG 4 on multiple levels. For example, by providing customised learning recommendations and resources, AIGC helps meet each student's individual learning needs, thereby improving the quality of education[

10]. The generation of high-quality teaching content, such as e-textbooks and teaching videos, by AIGC, can enable more students to benefit from high-quality educational resources and narrow the academic gap caused by geographical location[

37]. The advent of AIGC technology has the potential to transform educational environments, facilitating the creation of more interactive and immersive learning experiences. This technological advancement can stimulate students' interest in learning and encourage them to actively explore knowledge[

38]. For adults, AIGC provides flexible learning programmes that facilitate the acquisition of new knowledge and skills and adapting to changes in their careers[

39]. Nevertheless, the implementation of AIGC is accompanied by specific challenges. Concerns have been raised regarding the accuracy and reliability of the generated content. If the content is inaccurate or biased, it can adversely affect students' learning outcomes[

40]. Conversely, excessive reliance on AIGC may diminish students' capacity for independent thinking, which is incompatible with cultivating fundamental literacy skills in innovation and problem-solving [

41]. Moreover, issues such as technology integration, data and privacy protection, the changing role of teachers, and uneven resource allocation also require attention[

42]. These issues concern not only the healthy development of AIGC technology itself but also broader social issues, such as the fairness and effectiveness of education.

This study conducted an extensive literature review to address the shortcomings identified and promote further development in this field. Utilising a questionnaire data analysis method based on SWOT analysis, we will systematically collect and analyse feedback from students and their teachers from diverse backgrounds on using AIGC tools. This will ensure authenticity and compliance, avoid the spread of false information, and assess the role and challenges of AIGC in promoting educational sustainability. The study will employ a quantitative analysis of student questionnaire data combined with the analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Furthermore, this study will propose effective strategies to address issues in the educational application of AIGC, such as privacy protection and technology ethics, to ensure the safety and effectiveness of technology applications. Combining the goals of China's education modernisation in 2035, we explore how AIGC technology can help build a lifelong learning system that provides individuals with diverse learning opportunities and high-quality educational resources, promotes educational system reform, and promotes educational sustainability.

1.2. AIGC-Driven Personalized Learning Mechanism

This paper explores how students utilise artificial intelligence to personalise their learning and to understand the mechanisms by which these two elements are coupled. The focus will be on the large language model (LLM) that underlies the currently more mainstream ChatGPT [

43]. It is imperative to delve into the intricacies of AIGC's generation logic to ascertain how students can utilise these tools to formulate Personalized learning experiences [

44]. This has a positive effect on the sustainability of education.

LLM (Large Language Model) is an AIGC (Artificial Intelligence Generative Model) system employed for modelling and processing human language[

44]. The appellation 'large' is attributed to the fact that these models generally comprise hundreds of millions or even billions of parameters that define the model's behaviour[

45]; these parameters are pre-trained using a substantial amount of text data[

46]. The underlying technology of LLM is known as the Transformer neural network, or simply Transformer[

44].

In 2017, researchers at Google proposed Transformers in the renowned paper 'Attention is All You Need'. This paper introduced a novel approach to natural language processing (NLP) tasks, achieving unparalleled accuracy and speed[

47].The unique functions of Transformers have resulted in a significant enhancement to the capabilities of LLM[

48].It can be posited that the current generative AIGC revolution would not have been possible in the absence of Transformers[

49].

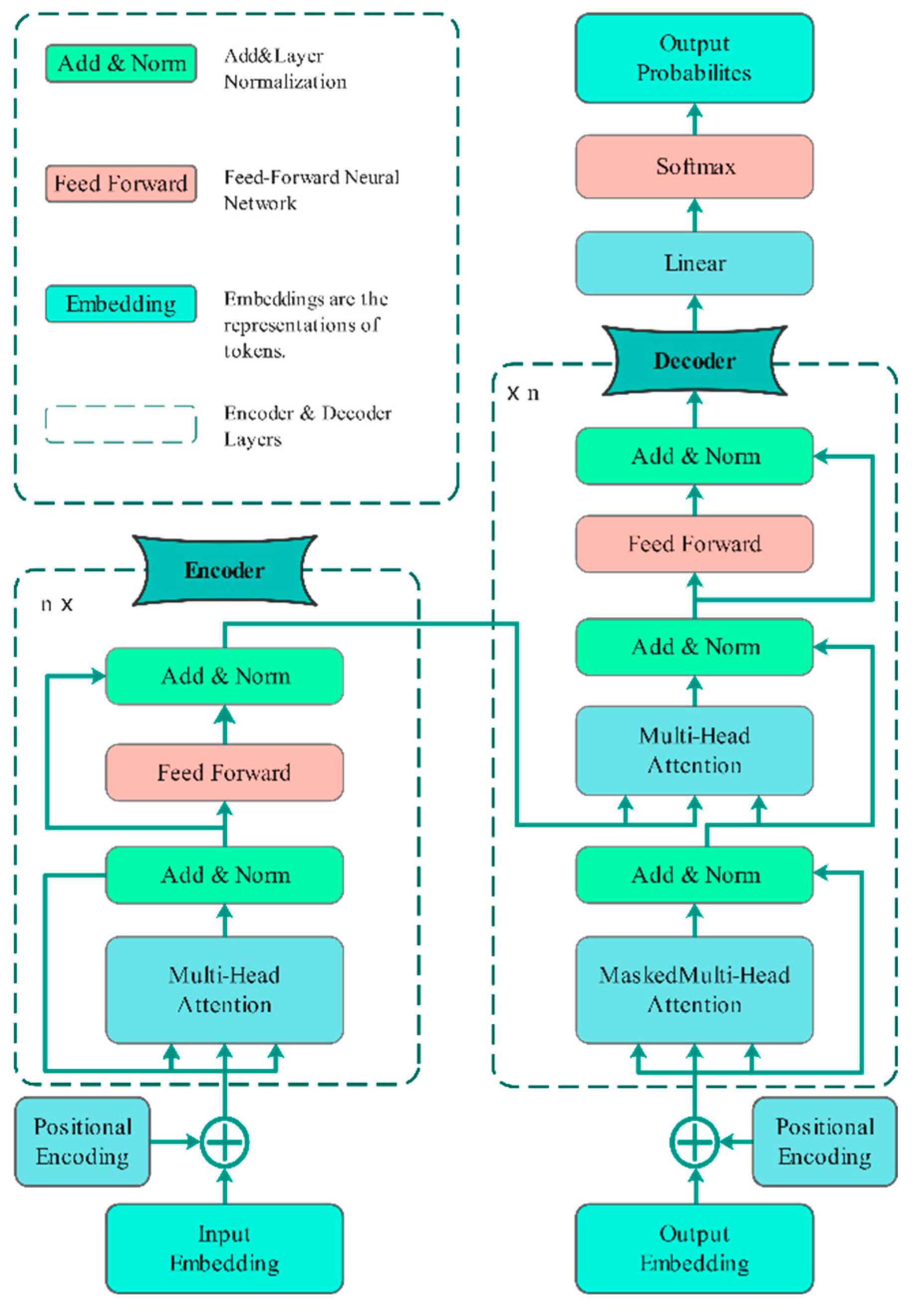

As illustrated in

Figure 1, the architecture of a Transformer-based Large Language Model (LLM) model consists of multiple components:

The comprehension of the architecture diagram of a large language model has been demonstrated to facilitate a more profound comprehension of the manner in which students utilise AIGC to facilitate Personalized learning. Input Embeddings: The input text will be marked into smaller units, such as words or subwords, and each mark will be embedded into a continuous vector representation[

50]. The purpose of this step is to capture both semantic and syntactic information about the input. Positional encoding: the positional information about the tags is added to the input embedding since the order of the tags is not naturally encoded by the converter[

51]. The purpose of this step is to capture both semantic and syntactic information about the input. Positional encoding: the positional information about the tags is added to the input embedding since the order of the tags is not naturally encoded by the converter[

52]. The Transformer architecture is predicated on utilising multiple encoder layers[

53]. The self-attention mechanism and the feed-forward neural network constitute the two fundamental subcomponents of each encoder layer[

54]. The Self-Attention Mechanism is a process which enables the model to measure the importance of different tokens in the input sequence by calculating an attention score[

55]. This approach allows models to consider the dependencies and relationships between different tokens context-awarely [

56]. Feed-forward neural networks are machine learning models that iteratively process data. Following the self-attention step, the feed-forward neural network is applied independently to each token[

57]. The network incorporates fully connected layers with non-linear activation functions, thereby enabling the model to capture intricate interactions between tokens[

58].In specific transformer-based models, an additional component known as a decoder is incorporated in addition to the encoder[

59]. The decoder layer facilitates autoregressive generation, whereby the model can generate sequential output by focusing on previously generated tokens[

60].Multi-Head Attention: Transformers typically utilise multiple heads, wherein the self-attention is executed concurrently with distinct learning attention weights[

61]. This facilitates the model's capacity to capture diverse relationships whilst concurrently attending to the entirety of the input sequence. Layer Normalisation: Layer normalisation is implemented after each subcomponent or layer within the Transformer architecture. This stabilises the learning process and enhances the model's aptitude for generalisation across disparate inputs[

62]. The number of output layers in a transformer model depends on the task.[

63]。In language modelling, for instance, a linear projection is frequently employed, followed by a SoftMax activation, to generate the probability distribution of the subsequent token[

64].

Based on the above, it is not difficult to understand that when students interact with large-scale model-based AIGC such as ChatGPT, they initiate a dynamically adapted learning loop system[

65].In this system, after a student starts asking a question to AIGC, ChatGPT will run based on a large language model (LLM) to provide initial answers and opinions[

66]. As this learning loop continues, ChatGPT will continue to collect feedback from students, both positive and negative[

67]; after processing this information using a large language model, ChatGPT will then continuously optimise the quality of the subsequent output content. At the same time, it will use a built-in reinforcement algorithm to output knowledge related to factors such as the student's feedback interests and learning progress, helping students to construct Personalized learning[

68].In short, AIGC, based on a large language model (LLM), can drive highly Personalized learning for students in education by integrating massive amounts of data after training[

69]. During the Personalized learning process driven by the AIGC, the AIGC acts as a transmitter of knowledge and a learning partner who can accompany students. By continuously collecting and analysing the learning behaviours provided by students, such as their learning interests, subjects and directions, AIGC constructs Personalized learning for each student[

70].

1.3. The Current Trend of Chinese College Students Using AIGC to Drive Personalized Learning

Among universities in China, there has been a significant increase in the trend of students using AIGC artificial intelligence to generate content for Personalized learning, especially in terms of usage and number of users[

17].

In terms of use, Personalized learning powered by AIGC has been widely used in many learning scenarios. For example, in essay writing, many students use AIGC to help them write essay reports, which improves efficiency, but also enhances the professionalism and logic of the writing[

71]. Second, for programming courses, AIGC can help students solve some of the difficulties in programming and provide timely feedback to help students understand and master complex programming knowledge. Finally, art students also use AIGC to generate ideas, such as image processing and animation production, which allows students with less drawing skills to create[

72].

The data shows a clear upward trend in the number of users. According to a survey of students nationwide initiated by the China Youth Daily, 84.8% of respondents have used AIGC[

73]. In another study by the National Business Daily, nearly 60% of students surveyed said they had used the popular AIGC model, based on 370 valid questionnaires collected from more than 10 universities over five months [

74]. Of these students, 26.76% are high-frequency users, using AIGC 1-2 times a week. And 5.95% of students use AIGC almost every day.

Not only that, but an article on the website The Economic Observer pointed out that almost all the students around them were using AIGC to help them with their homework. This widespread phenomenon is not limited to students in a particular year but extends throughout the university. Even first-year students who have just entered the university use AIGC to further their Personalized learning[

71].

However, we should also be aware that as more and more students use AIGC, it has raised some concerns. On the one hand, over-reliance on AIGC may lead to a decline in students' originality and critical thinking. On the other hand, students' integrity is called into question. For this reason, many Chinese universities have introduced policies to regulate the scope and proportion of AIGC use[

75]. For example, the Student User Guide for Artificial Intelligence Generated Content states that directly generated content should not exceed 20% of the full text[

76].

1.4. Research Framework and Research Questions

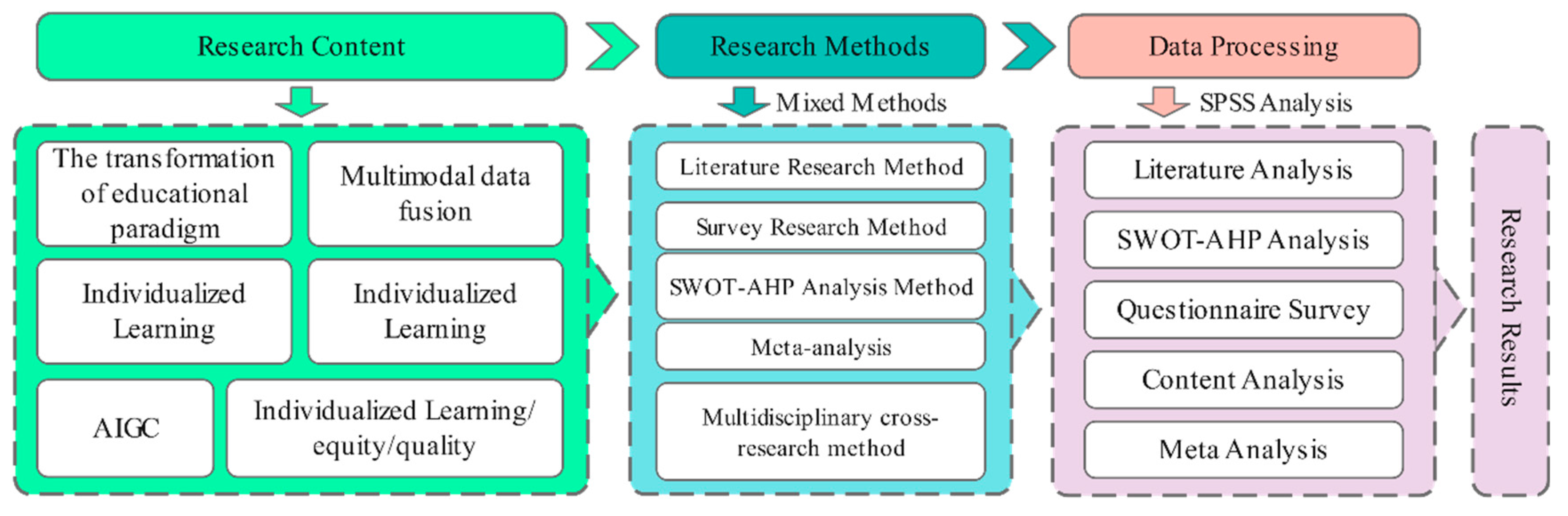

Based on the above discussion, we propose a research framework (see

Figure 2), based on which this study will start with the topic of the use of AIGC and students and focus on the content of the study, using mixed research methods[

77], Combined with the extensive literature review in the previous section[

39,

43,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94]and SWOT analysis[

95]questionnaires, collect and analyse data and conduct in-depth research into the role of AIGC-led Personalized learning in promoting educational sustainability and its impact on students' cognition, learning experience and long-term development.

This study aims to answer the following three key research questions.:

1. Are students aware of the contribution of AIGC-led Personalized learning to the sustainability of education?

2. From the students' perspective, what are the specific ways Personalized learning driven by the AIGC contributes to the sustainability of education?

3. What are the main challenges that AIGC-driven Personalized learning poses for the sustainability of education from the student's point of view?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Methodology

To thoroughly explore the role and challenges of Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC)-driven Personalized learning in promoting educational sustainability, this study decided to adopt a mixed research method of literature review and questionnaire survey (the questionnaire design is based on SWOT-AHP) to combine the advantages of these two research methods in the research design[

96]. This method provides a broad understanding from a macro perspective and explores the relationship between individual student experiences and behaviours from a micro perspective, providing more comprehensive and detailed data and results for the study as a whole[

97].

First, we will send more than 1,000 online questionnaires to students at Chinese universities. The questionnaire design will be based on the results of a preliminary literature review[

39,

43,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94]. The SWOT analysis framework was also used to ensure that the content of the questionnaire design covered several key areas of AIGC technology application, such as Personalized access to resources, the use of intelligent tutoring systems, and the changes in the quality of teaching and learning brought about by AIGC. At the same time, to ensure the quality and validity of the data, special attention was paid during the questionnaire design phase to avoid leading questions and to use different types of questions, such as multiple choice and scale questions, to improve the authenticity and completeness of the responses[

98].

Secondly, we will conduct a detailed data analysis of the collected data. We will use SPSS version 28 statistical software for detailed data analysis. First, we will ensure the reliability and credibility of the data through reliability and validity analysis[

99]. Secondly, descriptive statistical analysis is used to understand the essential characteristics of the sample[

100]. Thirdly, by analysing multiple response frequencies,[

100]To explore the attitudes and views of the Chinese university community towards the use of AIGC-supported Personalized learning and then to examine the specific contributions and challenges of AIGC-supported Personalized learning to educational sustainability through exploratory factor analysis and, fourth, through the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) combined with the four dimensions of SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats). The AHP analysis mainly uses the frequency and response rate of the options in the questionnaire to directly calculate the normalised weight, avoiding the complexity of the traditional pairwise comparison matrix and consistency testing steps to efficiently and accurately obtain the weight distribution[

101].

Finally, based on the results of the above data analysis and through specific discussions, we will answer the three questions investigated in this research and conclude. This part of the content is not just a simple report of the data we have collected but a combination of literature analysis and actual data analysis to draw our conclusions and point out recommendations with practical significance[

102]. For example, what is the specific attitude of the Chinese student group towards Personalized learning through AIGC? If AIGC-based Personalized learning helps improve students' learning efficiency, we will further explore the success factors. Conversely, suppose AIGC-based Personalized learning has opposing challenges and impacts students' learning. In that case, we need to analyse the underlying reasons and consider how to improve and overcome these challenges.

2.2. Research Samples

We conducted a study on the impact of Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC)-driven Personalized learning on educational sustainability among Chinese college students, for which a detailed online questionnaire was specially designed.This study aims to comprehensively understand college students' experiences and the effectiveness of AIGC technology in learning and explore the challenges and opportunities this emerging technology may bring.

To ensure that the sample was broadly representative, we used a snowball sampling technique[

103]; colleges and universities in different regions, levels and types across China were selected as sampling points, with a particular focus on the group of college students using Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC) technology in Chinese universities. Questionnaires were distributed to students at these schools via online and social media channels to students from different regions of China using AIGC. These users were then encouraged to recruit other students who met the research criteria to join their social networks. This strategy not only helped to reach a specific but widespread audience but also helped to improve the sample's diversity, coverage and representativeness [

104].

Upon completing the survey, we collected 928 valid questionnaires.This response reflects the participants' high awareness and support for this study and demonstrates the effectiveness of our questionnaire design and distribution strategy, which can provide a solid basis for subsequent data analysis. In the process of eliminating invalid questionnaires, we strictly screened according to pre-set criteria, including but not limited to checking whether the questionnaire was completed, whether there were logical inconsistencies, whether the time taken to complete the questionnaire was reasonable, etc., to ensure that each questionnaire entering the analysis stage had a high degree of authenticity and reliability. Specifically, we assessed the validity of the questionnaire based on the following points: Completeness: all required questions must be answered; for non-required questions, the importance is determined according to the project's needs. Submission time: Ensure the questionnaire submission time is within the official launch period, excluding early or late submissions. Response time: set a reasonable minimum and maximum response time, considering the length and complexity of the questionnaire. Response times that are too short or too long will be regarded as abnormal and eliminated[

105].

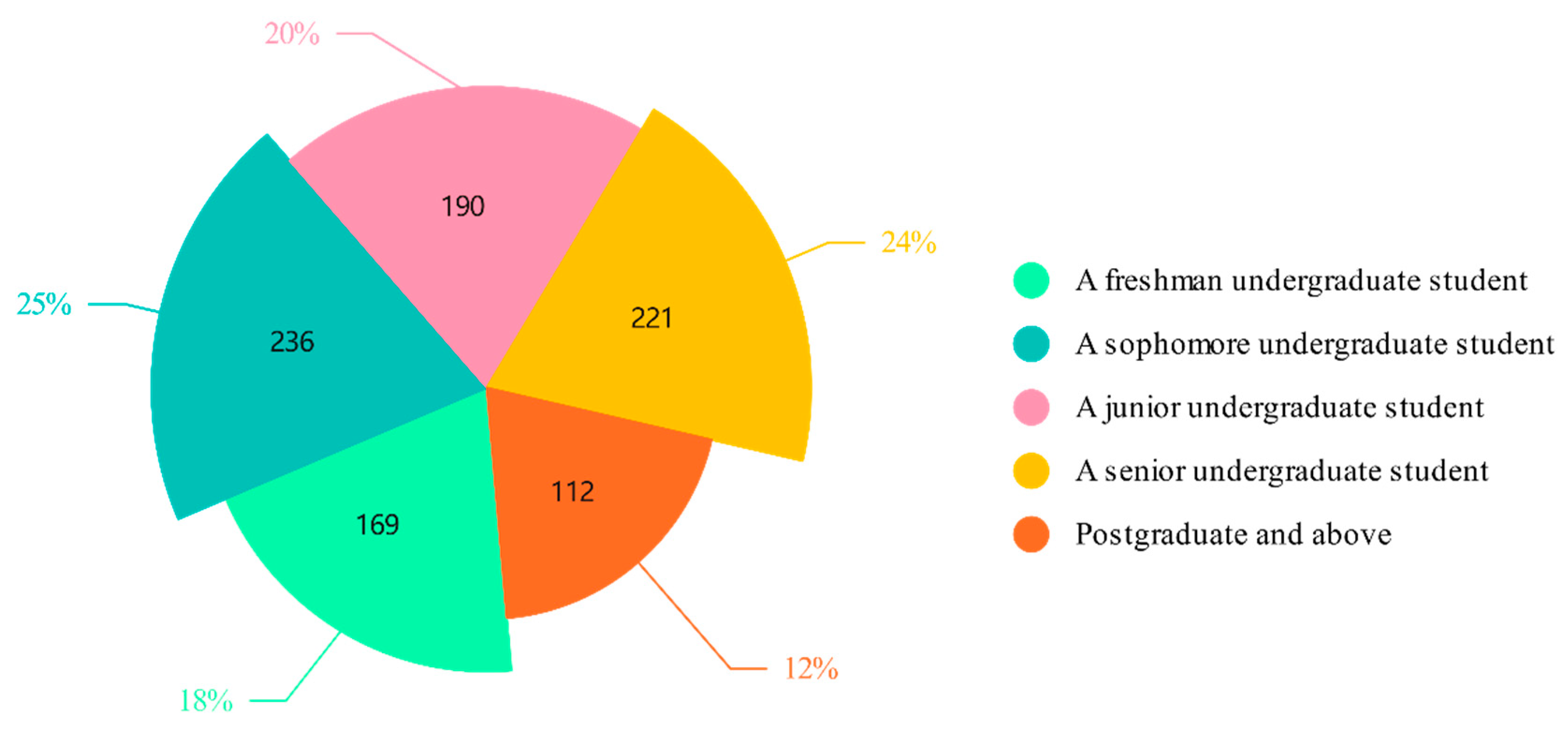

Next, a specific analysis of the grade composition of the participants who responded to the questionnaire is presented. From the valid questionnaires that were returned, the grade distribution of the participants shows specific characteristics that provide a valuable perspective for understanding the attitudes and use of AIGC technology among students in different grade levels (N = 928).

Figure 3 below shows the detailed grade distribution:

2.3. Questionnaire Design

This study designed a questionnaire based on a SWOT analysis [

106]to address existing research shortcomings and encourage further development. This methodology not only helped to achieve broader coverage of the target group but also saved time and money while ensuring that the sample size was large enough to support the validity of statistical inference and ensure the accuracy and reliability of subsequent data analysis. More importantly, we carefully designed the questionnaire's content through systematic literature review and analysis to ensure its scientific and targeted nature.

The design of the questionnaire was preceded by an extensive literature review covering the main theoretical and empirical findings on AIGC and its application in the field of education. This literature provided us with a solid theoretical foundation which helped us to define the specific dimensions of 'educational sustainability' - inclusiveness, equity and quality - and to establish operational definitions for these concepts. For example, inclusiveness is understood as the ability of AIGC to promote mutual understanding and cooperation between students from different cultural backgrounds; equity focuses on whether technology can reduce inequalities in educational opportunities due to various economic conditions; and quality refers to whether Personalized learning pathways can effectively meet individual learning needs. Based on an extensive literature review, we constructed a multi-dimensional questionnaire covering the technical characteristics of AIGC and user perceptions, usage experiences, and potential impacts. On this basis, we carefully selected or adapted a set of representative questions to ensure that they reflect current research hotspots and practical application scenarios' challenges.

The questionnaire for this study was designed in two parts. We started with the research questions for this study and designed the first part of the questionnaire accordingly. That is, the first three Likert scale questions in the questionnaire were developed based on the question of whether students recognise the contribution of AIGC-based Personalized learning to educational sustainability[

107](Five responses: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree, scored as 5, 4, 3, 2, 1 respectively). The second part aims to fully understand students' views on the contribution and challenges of AIGC-driven Personalized learning to educational sustainability. In the second part of the questionnaire, we introduced the SWOT analysis framework (see

Table 1) [

107]. Such a framework not only helps us identify what exactly is driving the business but also allows us to identify potential risks and opportunities for improvement. We have developed four questions from the SWOT analysis model: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats[

108], to Explore how students perceive the contribution and challenges of AIGC-led Personalized learning to educational sustainability.

The questionnaire for this study was designed using a two-stage methodology. Firstly, student attitudes were measured directly using carefully constructed scale questions, and secondly, a SWOT analysis framework was used for more detailed exploration. By creating a questionnaire structure in this way, the whole questionnaire is focused and flexible enough to respond to complex real-life situations, providing strong support for understanding and promoting AIGC-led Personalized learning. See

Table 2 for the specific questionnaire:

2.4. Questionnaire Feedback and Data Processing

After the survey was completed, we collected the questionnaires from the respondents and successfully recovered 928 valid questionnaires, giving an effective recovery rate of 92.8%. The data obtained were verified, confirmed and entered into SPSS software version 28. To ensure the quality of the data, we first verified and confirmed the questionnaires, eliminating any invalid samples that could affect the accuracy of the results.

The cleaned data were then imported into SPSS software version 25 for analysis. A reliability and validity analysis was first conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the questionnaire [

108], followed by a descriptive statistical analysis summarising the essential characteristics of the sample[

109]. This was followed by a descriptive statistical analysis summarising the crucial characteristics of the sample[

110]. A multiple response frequency and exploratory factor analysis were then carried out, showing the number of times each option was selected and its proportion, which helps to understand the differences between the different categories[

111]. Finally, an Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) calculation was performed to assess the relative importance of other options in the four dimensions of Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT).

2.4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

According to the Cronbach's alpha coefficient table data presented in

Table 3, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the scale is 0.735 both before and after standardisation, indicating that both meet the standard of good reliability.

A total of 928 valid questionnaires and a relatively large sample size helped improve the stability and reliability of the reliability assessment. The calculated Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.735 is already entirely satisfactory for a scale with only three questions.

We then performed a statistical summary of the deleted analysis items. According to

Table 4, the statistical summary of the deleted analysis items, we first observed the average value after each item was deleted. We can see that the mean values of the three items "sustainability of education" (7.694), "equity of sustainability of education" (7.633), and "quality of sustainability of education" (7.635) are all high and similar, indicating that the respondents' positive evaluation of AIGC-driven Personalized learning in each dimension of educational sustainability is relatively consistent. Secondly, the variance data (3.926 to 4.04) show that the variance of the scale fluctuates less after each item is deleted, indicating that the degree of dispersion or variation in the scale does not change after an item is deleted. This supports the stability and reliability of the scale in measuring the same.

We then interpret the total variance component (see

Table 5). The data presented in the interpretation of the total variance component of the validity analysis provide key information on the eigenvalues of the principal components, the percentage of variance explained and their cumulative percentage.

The variance interpretation ratio measures the extent to which each principal component contributes to the total. It indicates the magnitude of the role of the principal component when the data is varied. It then reflects the proportion of the total variance in the data that a principal component can explain, which helps determine the number of principal components to retain. When interpreting the eigenroot of Component 1, which is 1.96, its variance interpretation rate is as high as 65.337%, and the cumulative percentage is also 65.337%. This means that component 1 accounts for most of the data variation that can be explained in the dataset. The eigenvalues of component 3 are 0.530.9, their variance interpretation rates are 17.02% and 16.961%, respectively, and the cumulative percentages reach 83.039% and 100%, respectively. Although components 2 and 3 are not as important as component 1, they also play a significant role in explaining the variation in the data. Overall, these three principal components explain the dataset (with a cumulative percentage of 100%), indicating that factor analysis is adequate and that the extracted principal components reflect the information in the original data. In particular, the high variance explained by Component 1 indicates that it is the most critical factor in the data set and is worthy of further in-depth study.

Finally, the table of factor load coefficients is a tool for assessing validity (see

Table 6). By examining the factor load coefficients and the commonality (common factor variance) after rotation, we can gain an in-depth understanding of the loading of each observed variable on the potential factors, thereby verifying the rationality of the scale design and the stability of the factor structure.

Specifically, the rotated factor loadings reflect the strength of the association between the observed variables and their corresponding factors. In this example, factor 1 covers the three key aspects of educational sustainability: sustainability, equity and quality. The loadings of the observations are all high, at 0.809, 0.813 and 0.803, respectively, all above the commonly accepted threshold of 0.5. These variables have a substantial load on 1, i.e. they can effectively reflect the broad characteristics of educational sustainability represented by factor 1. The degree of commonality (common factor) indicates the extent to which the observations are explained by their potential factors. In this case, the commonalities are 0.654, 0.662 and 0.644, all close to or above 6, further confirming the power of Factor 1 on these observed variables. A high degree of commonality means that most of the information in the observed variables can be captured by their corresponding factors, indicating internal consistency and construct validity.

2.4.2. Descriptive Analysis

According to the descriptive statistics in

Table 7, a descriptive statistical analysis was conducted on the three variables 'inclusiveness of education for sustainability', 'equity of education for sustainability' and 'quality of education' in the study, using 928 sample data in the context of Personalized learning driven by motivation. The sample size for each variable is 928, ensuring the data analysis's adequacy and representativeness. The rating system uses a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to agree) covering the lowest to highest rating range firmly.

The mean scores for sustainability inclusiveness and fairness were 3.787 and 3.8846, respectively, close to the upper middle of the scale, indicating that the respondents rated AIGC-led Personalized learning positively regarding the different dimensions of educational sustainability. The standard deviations were 1.169, 1.159 and 1.145, respectively, indicating some dispersion in the distribution, but the degree of dispersion was relatively small, indicating that the respondents' evaluations were relatively concentrated and there were no extremes. 4 This further confirms the trend reflected in the mean, i.e. a higher rating by most respondents. The standard deviation reflects the degree of dispersion of the data. Its values (inclusiveness 1.368, fairness 1.344, quality 1.311) mirror the standard deviation results, indicating that the data distribution is relatively concentrated. The kurtosis values are -0.089, 0.136 and 0.066, respectively, all close to 0 and close to a normal distribution, with no apparent peaks or troughs. The skewness values are -0.873, -0.976 and -0.928, respectively, all of which are negative and have large absolute values, indicating that the data distribution is skewed to the left, with the frequency of low scores slightly higher than that of high scores but overall still within an acceptable range. The coefficients of variation (CV) are 0.309, 0.301 and 0.298, respectively, all of which are less than 0.5, indicating that the degree of dispersion of the data is relatively small compared to the mean and that the consistency of the ratings is high.

2.4.3. Multiple Response Frequency Analysis

Table 8 shows the Multiple Response Frequency Analysis table, which shows the frequency distribution of the options, including the number of cases, the response rate and penetration rate, and the significance P value. The response rate is the proportion of all options selected for each option in a multiple-choice question. For example, if 10 people answer a multiple choice question, but 36 options are chosen, of which 8 are option a, the response rate for a = 8/36. The popularity rate is the proportion of each option selected for the valid sample. For example, if 10 people answer a multiple choice question with 8 options, of which 8 are option a, the popularity rate for a = 8/10—both the response rate and the popularity rate focus on analysing the higher-order items.

First, there is a consensus among the dominant participants that AIGC-driven Personalized learning has apparent advantages in terms of efficient organisation and access to learning resources (63.47% penetration rate), content that is more in line with personal interests and needs (59.806% penetration rate), and significantly improved equity in education (60.022% penetration rate). These benefits are highly statistically significant (p<0.001), indicating recognition. In addition, better stimulation of interest in learning and creativity (55.388% penetration rate) and promotion of lifelong learning (48.707% penetration rate) are also essential benefits; although the penetration rates are slightly lower, they are also statistically significant.

In terms of disadvantages, interruptions in learning due to technical problems (45.797% prevalence) were the main challenge faced by participants, followed by difficulties in getting immediate help (54.634% prevalence) and insufficiently rich or updated learning content (57.759% prevalence). These disadvantages are also statistically significant and reflect some problems with the practical application of Driven Personalized Learning. In contrast, the lack of a sense of personal interaction (28.987% prevalence) and the high demands on students' ability to learn independently (28.879% prevalence) are also challenges, but the prevalence rates are relatively low, and the statistical significance may be weak.

Regarding opportunities, participants believe that strengthening integration with other educational technologies (69.289% penetration rate) is the most important direction for future AIGC-supported Personalized learning that integrates meaning. Providing more interdisciplinary learning resources (53.233% penetration rate) and increasing interactivity and social functions (51.616% penetration rate) are essential development directions. Although improving the level of intelligence of algorithms (38.4% penetration rate) and ensuring continuous updates (37.177% penetration rate) were also mentioned, the relatively low penetration rates may reflect the relatively low expectations of the participants or a certain level of satisfaction with the intelligence of the technology and the quality of the content.

Regarding threats, high technical costs and maintenance fees (59.052% prevalence) are the main factors hindering the widespread use of AIGC-based Personalized learning. In addition, privacy and data security issues (41.703% prevalence), teacher and student emotions (44.397% prevalence), lack of support and training resources (50.754% prevalence), and algorithmic bias and fairness issues (45.366% prevalence) are also essential threats. These statistically significant factors indicate barriers to adopting AIGC-based Personalized learning.

The results of the KMO test in

Table 9 show that the KMO value is 0.627. At the same time, the results of the Bartlett sphericity test show that the significance p-value is 0.000***, which is significant at this level. This rejects the null hypothesis; the variables are correlated, so the factor analysis is valid. The questionnaire's data structure is valid and can be used for the subsequent factor analysis.

Table 10 below shows the factor loadings, which can be used to analyse the importance of the hidden variables in each principal component. Suppose we have identified n factors. Factors i with significant factor loadings for a, b, c and d can be assigned to an element (which can be renamed for clarity).

In exploratory factor analysis, the rotated factor loadings table provides key information revealing the relationship between variables and potential factors. An in-depth study of this table provides an accurate interpretation and understanding of the AIGC-driven factor structure across the four dimensions of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats.

2.4.4. SWOT-AHP Analysis

To explore the role and challenges of AIGC-driven Personalized learning in promoting educational sustainability, this study conducted a SWOT-AHP analysis of questions 4 to 7 of the questionnaire. This study used a normalised weight instead of a comparison matrix, mainly based on data collection methods and computational efficiency considerations. The questionnaire directly provides the frequency and response rate of the options, which already reflects the relative importance of the options, so there is no need to make a subjective comparison by constructing a comparison matrix. Normalised weighting is more concise and efficient as it can directly generate weights based on response and prevalence rates. This avoids the computational complexity and consistency checking steps of the comparison matrix when there are many options, making it more suitable for processing large amounts of questionnaire data and deriving weighting results. The specific steps are:

(1)Internal factor weight calculation

For each option under each SWOT dimension (Strengths S, Weaknesses W, Opportunities O and Threats T), the relative weight is determined by standardisation based on popularity (i.e. the percentage of effective samples selecting that option):

Example: Option A has a popularity of 63.47% on the Advantages dimension and a total popularity of 287.40%. Its internal weight is:

(2)SWOT category weight calculation

The overall importance is determined based on the proportion of total responses in each dimension:

Example: The total number of responses for the benefit dimension is 2,667, and the total number of responses for the sample is 9,229. The weight of the main category is:

(3)Comprehensive priority ranking

Combine the internal weights with the category weights to calculate the global priority:

Example: The combined weight of opportunity A (technology integration) is:

(4)Results and analysis

Table 11.

Strengths

| options (as in computer software settings) |

Count (N) |

Penetration rate (%) |

Internal weighting (%) |

| A |

589 |

63.47 |

22.08 |

| B |

555 |

59.81 |

20.80 |

| C |

557 |

60.02 |

20.88 |

| D |

514 |

55.39 |

19.27 |

| E |

452 |

48.71 |

16.95 |

| (grand) total |

2,667 |

287.40 |

100.00 |

Table 12.

Weaknesses

| options (as in computer software settings) |

Count (N) |

Penetration rate (%) |

Internal weighting (%) |

| A |

425 |

45.80 |

21.20 |

| B |

269 |

28.99 |

13.42 |

| C |

507 |

54.63 |

25.28 |

| D |

536 |

57.76 |

26.74 |

| E |

268 |

28.88 |

13.37 |

| (grand) total |

2,005 |

216.06 |

100.00 |

Table 13.

Opportunities

| options (as in computer software settings) |

Count (N) |

Penetration rate (%) |

Internal weighting (%) |

| A |

643 |

69.29 |

27.73 |

| B |

494 |

53.23 |

21.30 |

| C |

479 |

51.62 |

20.65 |

| D |

357 |

38.47 |

15.40 |

| E |

345 |

37.18 |

14.88 |

| (grand) total |

2,318 |

249.79 |

100.00 |

Table 14.

Threats

| options (as in computer software settings) |

Count (N) |

Penetration rate (%) |

Internal weighting (%) |

| A |

387 |

41.70 |

17.28 |

| B |

548 |

59.05 |

24.47 |

| C |

412 |

44.40 |

18.42 |

| D |

471 |

50.75 |

21.02 |

| E |

421 |

45.37 |

18.80 |

| (grand) total |

2,239 |

241.27 |

100.00 |

Table 15.

SWOT Category Weight Table

Table 15.

SWOT Category Weight Table

| dimension (math.) |

Total number of responses (N) |

Weighting of broad categories (%) |

| Strengths (S) |

2,667 |

28.89 |

| Weaknesses (W) |

2,005 |

21.73 |

| Opportunities (O) |

2,318 |

25.11 |

| Threat (T) |

2,239 |

24.26 |

| (grand) total |

9,229 |

100.00 |

Table 16.

Comprehensive priority top 5 ranking table

Table 16.

Comprehensive priority top 5 ranking table

| rankings |

considerations |

SWOT dimension |

Weighting of broad categories (%) |

Internal weighting (%) |

Combined weight (%) |

| 1 |

Opportunity A (technology integration) |

O |

25.11 |

27.73 |

6.97 |

| 2 |

Strength A (efficient resources) |

S |

28.89 |

22.08 |

6.38 |

| 3 |

Strength C (Educational Equity) |

S |

28.89 |

20.88 |

6.03 |

| 4 |

Strength B (Not Specified) |

S |

28.89 |

20.80 |

6.01 |

| 5 |

Threat B (High Cost) |

T |

24.26 |

24.47 |

5.94 |

(5)Statistical validation

Chi-square test of the distribution of options for the dominant dimension The result of the significance test is:

Indicates that the difference in option choice is highly statistically significant. Consistency of weights: The sum of the weights within all dimensions is 100%, and the sum of the weights of the main categories is 100%. There is no cumulative error in the calculation process.

Verification of the response rate: The response rates for the high-weight options (e.g. Opportunity A, Advantage A) (69.29%, 63.47%) are significantly higher than the average, supporting the rationality of their priority.

3. Results

3.1. Are students Aware of the Contribution of AIGC-Led Personalized Learning to the Sustainability of Education?

According to the survey results, AIGC (artificial intelligence-generated content)-driven Personalized learning is widely perceived by students as conducive to educational sustainability. Specifically, in the reliability analysis, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.735, indicating that the scale has good internal consistency. This result not only reflects the effectiveness of the questionnaire design but also suggests that respondents have a high degree of recognition of the questionnaire's content. The descriptive statistical analysis shows that for the three dimensions of educational sustainability, inclusiveness, fairness and quality, the average scores given by the respondents were 3.787, 3.848 and 3.846, respectively (based on a 5-point Likert scale). These scores are close to the upper middle of the scale, indicating that respondents have a favourable view of AIGC-led Personalized learning in terms of the dimensions of educational sustainability.

According to the survey results, AIGC (artificial intelligence-generated content)-driven Personalized learning is widely perceived by students as conducive to educational sustainability. Specifically, in the reliability analysis, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.735, indicating that the scale has good internal consistency. This result not only reflects the effectiveness of the questionnaire design but also suggests that respondents have a high degree of recognition of the questionnaire's content. The descriptive statistical analysis shows that for the three dimensions of educational sustainability, inclusiveness, fairness and quality, the average scores given by the respondents were 3.787, 3.848 and 3.846, respectively (based on a 5-point Likert scale). These scores are close to the upper middle of the scale, indicating that respondents have a favourable view of AIGC-led Personalized learning in terms of the dimensions of educational sustainability.

3.2. From the Students' Perspective, What Are the Specific Ways Personalized Learning Driven by the AIGC Contributes to the Sustainability of Education?

According to the questionnaire survey on the strength dimension and the SWOT-AHP analysis, students believe that AIGC-led Personalized learning has promoted educational sustainability in the following aspects

The option "more efficient organisation and acquisition of learning resources" has a popularity rate of 63.47% and ranks high in internal weight (22.08%), indicating that students believe that technology can quickly integrate and present a wealth of learning resources, thereby improving learning efficiency.

The popularity of the option "Content that is more relevant to personal interests and needs" is regarding%, reflecting students' recognition of Personalized learning paths and content customisation, which they believe will help improve the learning experience and outcomes.

Significantly improve educational equity' received a popularity rate of 60.022%, indicating that students believe that AIGC can overcome the problem of uneven distribution of traditional educational resources, so that students from different families and backgrounds have more equal access to education.

Although the popularity rate is slightly lower (about 55.39%), it still shows that students positively evaluate AIGC in stimulating learning interest and creative thinking.

About 48.71% of the students believe that AIGC helps promote lifelong learning, which reflects the expectation of the future continuous learning model.

From the overall assessment of 'educational sustainability', the questionnaire reflects positive effects in the three dimensions of inclusiveness, fairness and quality, constituting the students' specific perception of Personalized learning promoting educational sustainability.

3.3. What Are the Main Challenges That AIGC-Driven Personalized Learning Poses for the Sustainability of Education from the Student's Point of View?

Questionnaires and SWOT-AHP analyses revealed the following key challenges for Personalized learning that may affect the further promotion of the AIGC driver and factors that negatively impact the sustainability of the training:

Interruptions in learning due to technical problems: The popularity rate was 45.80%, indicating that students encounter technical failures or instability during actual use, quickly interrupting learning. Difficulty getting immediate help: The prevalence rate was 54.63%, indicating that students do not receive timely and effective technical or teacher support when encountering problems.

The prevalence rate of the option "The learning content is not rich or updated promptly" was 57.76%, indicating that students have high demands for the diversity and timeliness of the content on the Personalized learning platform, which may also limit the improvement of the quality of education.

In the threat dimension, 'high technical costs and maintenance fees' received a popularity rating of 59.05% (internal weight of 24.47%), reflecting students' concerns that the economic pressures of technical investment and subsequent maintenance may limit the widespread use of Personalized learning.

Privacy and data security issues, teacher-student resistance and lack of adequate technical support and training resources each had a popularity rate of around 41% to 50%, indicating that students are concerned about data protection, interaction and technical training. In addition, algorithmic bias and fairness are also a concern for some students (with a popularity rate of around 45.37%), suggesting the potential risk of unfairness in Personalized recommendations and automated decision-making.

Students believe that while AI-driven Personalized learning offers convenience and efficiency, it still faces challenges regarding technical reliability, timely content updates, cost pressures, data security and support services. If these issues are not effectively addressed, they could hurt the sustainability of education.

4. Discussion

The data analysis of this study reveals that students have ambivalent attitudes towards AIGC technology-enhanced Personalized learning. The high mean scores on the inclusiveness (3.782), fairness (3.803) and quality (3.846) scales indicate that students generally recognise the potential value of technology for the sustainability of education, and in particular 'efficient access to educational resources' (63.47%) and 'improved educational equity' (60.02%) are seen as key benefits. This recognition may be due to the fact that technology directly addresses the pain points of traditional education - for example, reducing inequalities in educational opportunities due to geographical or economic conditions through Personalized distribution of resources. However, there is a clear disconnect between this optimism and actual experience: almost half of students (45.80%) have experienced learning disruptions due to technical failures, and more than half (57.76%) have indicated that content updates lag behind, reflecting the fact that the stability of technology implementation and content ecology have not yet met actual needs. This contradiction suggests that students' expectations of the potential of technology may have masked the current lack of maturity in its application, and that there is a need to guard against the risk of a decline in high recognition over time.

The data also reveal the complexity of technological empowerment. Although most students (60.02%) recognise that technology promotes fairness, there are also significant concerns about algorithmic bias (45.37%) and high costs (59.05%). This contradiction may be due to the practical limitations of technology implementation: while AIGC can break down individual barriers to access, if the underlying algorithmic training data implicitly contains historical biases (such as an over-reliance on the learning trajectories of urban student groups), it will instead entrench structural inequalities. Furthermore, factor analysis shows that inclusivity, equity and quality are highly clustered on a single principal component (loadings 0.803-0.813, variance explained 65.34%), suggesting that students' understanding of educational sustainability is highly dependent on technical efficacy. This cognitive tendency may lead to a systemic risk that 'technological failure means educational interruption', such as platform failure leading to a complete halt in learning activities, or an over-reliance on technology to the neglect of non-technological elements such as the role of the teacher and interpersonal interactions (only 28.99% mentioned 'lack of interaction').

Indications of group differentiation in the data need to be interpreted with caution. For example, the low popularity of 'excessive demands on self-directed learning skills' (28.88%) may indicate that this issue mainly affects specific groups (such as lower grade students), while highly self-directed learners have adapted to the technology-driven learning model. At the same time, the coexistence of 'high cost' (59.05%) as the main threat and the high recognition of 'improved equity' suggests that technology can partially compensate for economic differences, but cannot completely remove the threshold for resource investment.

5. Limitations

This study has made some contributions to the exploration of the mechanism and challenges of the impact of Personalized learning constructed with AIGC technology on the sustainability of education. However, the study is not without its limitations and deficiencies. Firstly, the data collection method of the questionnaire survey is subject to personal perception, memory bias and response tendency of the respondents, resulting in some biases in the data. Secondly, the study's reliance on quantitative analysis in the questionnaire survey, without complementing it with in-depth qualitative analysis, may limit the scope of investigation.Moreover, existing theories in educational technology and information science may not fully capture the complexities of the rapidly evolving AIGC technology field.Consequently, there is a need to develop a theoretical framework that is more adaptable to the emerging technological environment to provide a foundation for future research. Finally, the cross-sectional design of the study precludes the establishment of direct causal links, and the uneven distribution of educational resources across countries and regions, with significant variations even within countries, poses challenges to the application and promotion of research results.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study provides a valuable and important perspective for understanding the impact of AIGC technology-driven Personalized learning on educational sustainability, and lays a foundation for further exploration. However, the study has certain limitations in terms of data collection, data analysis, and theoretical framework, and future research should improve on these issues.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Through empirical analysis, this study reveals the complexity of the impact of AIGC technology-enhanced Personalized learning on educational sustainability. The data show that students have a high perception of the equity of technology-enabled education (mean 3.803/5), the efficiency of resource access (63.47%), and the quality of learning (mean 3.846), indicating that AIGC technology can effectively break through the resource allocation barriers in traditional education caused by geography and economic conditions. However, the coexistence of insufficient technological stability (45.80%), delayed content updates (57.76%) and the threat of high costs (59.05%) reveals a significant mismatch between idealised expectations and the actual operating state during the technology implementation process. Most notably, there is a structural contradiction between students' perception of educational fairness (60.02%) and their concerns about the risk of algorithmic bias (45.37%), suggesting that technology may only be able to alleviate apparent resource imbalances, but may reproduce hidden inequalities due to historical biases in training data or the intervention of commercial logic.

Further analysis shows that students' perceptions of educational sustainability are highly dependent on technology. Factor analysis results show that inclusiveness (load 0.803), fairness (0.809) and quality (0.813) are clustered on a single principal component (variance explained 65.34%), reflecting a tendency to simplify educational sustainability as a technical performance indicator. This perception can lead to systematic risks: on the one hand, an over-reliance on technology can make the educational ecology vulnerable, e.g. platform failures leading to disruptions of learning activities; on the other hand, the marginalisation of humanistic elements (e.g. only 28.99% are concerned about the lack of interaction) can deviate from the humanistic nature of education. The evidence of group differentiation implied by the data - for example, only 28.88% selected 'excessive demands on self-directed learning skills' - further suggests that there may be an implicit threshold for the extent of the benefits of technological empowerment, and that the actual plight of some groups (such as younger students or those with different cognitive styles) may be masked by the overall data.

Based on the above conclusions, this study proposes three systematic implications. First, technological optimisation needs to be promoted in parallel with a governance framework, including the establishment of algorithmic transparency tools (such as interpretable interfaces) to reduce fairness challenges caused by black-box decisions (45.37%) and the use of dynamic monitoring mechanisms to shorten the content update cycle (to address the 57.76% lag). Second, the implementation of educational fairness needs to go beyond a single technological path, for example by providing computing power subsidies through a 'government-school-business' collaborative model (to address the 59.05% high cost problem), and repositioning the role of teachers as algorithm correctors and emotional supporters. Finally, it is necessary to reconstruct the cognitive paradigm of educational sustainability, strengthen the cultivation of critical technical skills in curriculum design, and retain non-technical learning scenarios (such as offline collaboration) to avoid the erosion of the multidimensional value of education by efficiency orientation. Future research needs to track the impact of long-term exposure to technology on students' metacognitive skills and use longitudinal data to reveal the collaborative evolution of AIGC and the education system.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleagues, who distributed the questionnaires to students, and the students who took the time to complete the questionnaires online.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation, manuscript writing, or the decision to publish the results.

References

- SDG4. Available online: https://unric.org/en/sdg-4/ (accessed on December 2024).

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Hughes, L.; Ismagilova, E.; Aarts, G.; Coombs, C.; Crick, T.; Duan, Y.; Dwivedi, R.; Edwards, J.; Eirug, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence (AI): Multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. International Journal of Information Management 2021, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laar, E.; van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M.; de Haan, J. The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Computers in Human Behavior 2017, 72, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; He, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, S.; Liu, K.; Han, Q.-L.; Tang, Y. A Brief Overview of ChatGPT: The History, Status Quo and Potential Future Development. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica 2023, 10, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y. Human Creativity in the AIGC Era. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 2023, 9, 541–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lin, C. Changes in the way of learning under the influence of AIGC. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2024); 2024; pp. 641–650. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.-A.; Tzeng, J.-W.; Huang, N.-F.; Su, Y.-S. Prediction of student performance in massive open online courses using deep learning system based on learning behaviors. Educational Technology & Society 2021, 24, 130–146. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Ren, Y.; Nyagoga, L.M.; Stonier, F.; Wu, Z.; Yu, L. Future of education in the era of generative artificial intelligence: Consensus among Chinese scholars on applications of ChatGPT in schools. Future in Educational Research 2023, 1, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrat, J. Our final invention: Artificial intelligence and the end of the human era; Hachette UK: 2023.

- Chen, X.; Hu, Z.; Wang, C. Empowering education development through AIGC: A systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Digital enablers. In The Economic Value of Digital Disruption: A Holistic Assessment for CXOs; Springer: 2023; pp. 1-110.

- Liang, C.; Du, H.; Sun, Y.; Niyato, D.; Kang, J.; Zhao, D.; Imran, M.A. Generative AI-driven semantic communication networks: Architecture, technologies and applications. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Academy of Information and Communications Technology Releases White Paper on Artificial Intelligence Generated Content (AIGC). Available online: https://www.caict.ac.cn/kxyj/qwfb/bps/202209/P020220902534520798735.pdf (accessed on .

- Wu, J.; Gan, W.; Chen, Z.; Wan, S.; Lin, H. Ai-generated content (aigc): A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.06632, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, N.J. Artificial intelligence: a new synthesis; Morgan Kaufmann: 1998.

- Dai, C.-P.; Ke, F. Educational applications of artificial intelligence in simulation-based learning: A systematic mapping review. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2022, 3, 100087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Dai, Y.; Yu, P.S.; Sun, L. A comprehensive survey of ai-generated content (aigc): A history of generative ai from gan to chatgpt. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04226. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Qi, S.; Zhao, R.; Zhihua, X.; Weng, J. Security and privacy on generative data in aigc: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liang, X. Generative AI Research of Education from 2013 to 2023. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Computer Science and Technologies in Education (CSTE); 2024; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, T.R.; Susnjak, T.; Liu, T.; Watters, P.; Halgamuge, M.N. From google gemini to openai q*(q-star): A survey of reshaping the generative artificial intelligence (ai) research landscape. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10868, arXiv:2312.10868 2023. [CrossRef]

- Foo, L.G.; Rahmani, H.; Liu, J. Aigc for various data modalities: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.14177, arXiv:2308.14177 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Yan, M.; Su, Z.; Luan, T.H. A survey on ChatGPT: AI-generated contents, challenges, and solutions. IEEE Open Journal of the Computer Society 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospíšil, B.D. Artificial Intelligence in Global Management. Palacky University, Olomouc, 2018, 1-119.

- China's Education Modernization 2035. Available online: https://bksy.nxu.edu.cn/__local/1/F6/FB/6CDCB59498A8123885ED0687C23_5E22BC3E_660A0.pdf (accessed on .

- Gu, J.; Li, X.; Wang, L. Higher education in China; Springer: 2018.

- Ashida, A. The role of higher education in achieving the sustainable development goals. In Sustainable development disciplines for humanity: Breaking down the 5Ps—people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnerships; Springer: 2022; pp. 71-84. [CrossRef]

- Heleta, S.; Bagus, T. Sustainable development goals and higher education: leaving many behind. Higher Education 2021, 81, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žalėnienė, I.; Pereira, P. Higher education for sustainability: A global perspective. Geography and Sustainability 2021, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabalala, L.P.; Ngcwangu, S. Accelerating the implementation of SDG 4: stakeholder perceptions towards initiation of sustainable community engagement projects by higher education institutions. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2021, 22, 1573–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, I.; Saito, O.; Vaughter, P.; Whereat, J.; Kanie, N.; Takemoto, K. Higher education for sustainable development: Actioning the global goals in policy, curriculum and practice. Sustainability Science 2019, 14, 1621–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adomßent, M. Exploring universities' transformative potential for sustainability-bound learning in changing landscapes of knowledge communication. Journal of Cleaner Production 2013, 49, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, R.; Bain, R.; Cumming, O. A long way to go–Estimates of combined water, sanitation and hygiene coverage for 25 sub-Saharan African countries. PloS one 2017, 12, e0171783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolo, P.A.; Björck-Åkesson, E.; Giné, C.; Kyriazopoulou, M. Ensuring a strong start for all children: inclusive early childhood education and care. In Implementing inclusive education: Issues in bridging the policy-practice gap; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: 2016; pp. 19-35. [CrossRef]

- Abebe, W.; Woldehanna, T. Teacher training and development in Ethiopia: Improving education quality by developing teacher skills, attitudes and work conditions; Young Lives: 2013.

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and individual differences 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Zhou, H. Developing a synergistic approach to engineering education: China’s national policies on university–industry educational collaboration. Asia Pacific Education Review 2023, 24, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Qu, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y. From recorded to AI-generated instructional videos: A comparison of learning performance and experience. British Journal of Educational Technology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Wang, T.; Tong, Y. The effect of gamified project-based learning with AIGC in information literacy education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.-H.; Zhang, Y. Technology Acceptance and Innovation Diffusion: Are Users More Inclined Toward AIGC-Assisted Design? International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 2024, 1-15. [CrossRef]