Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

05 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

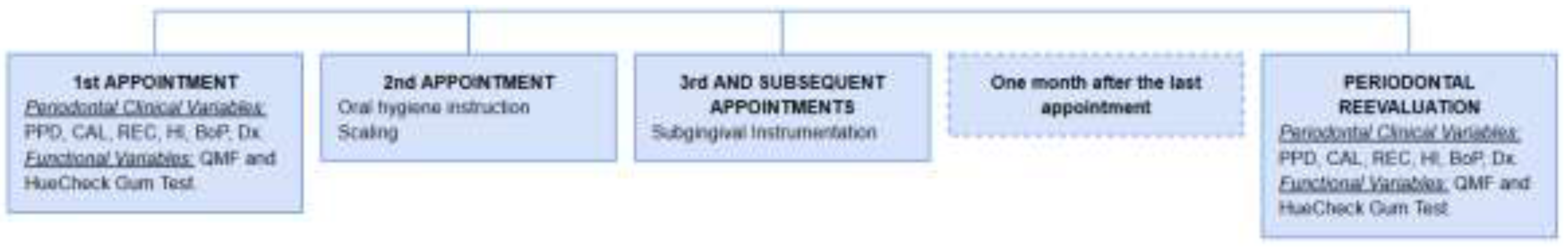

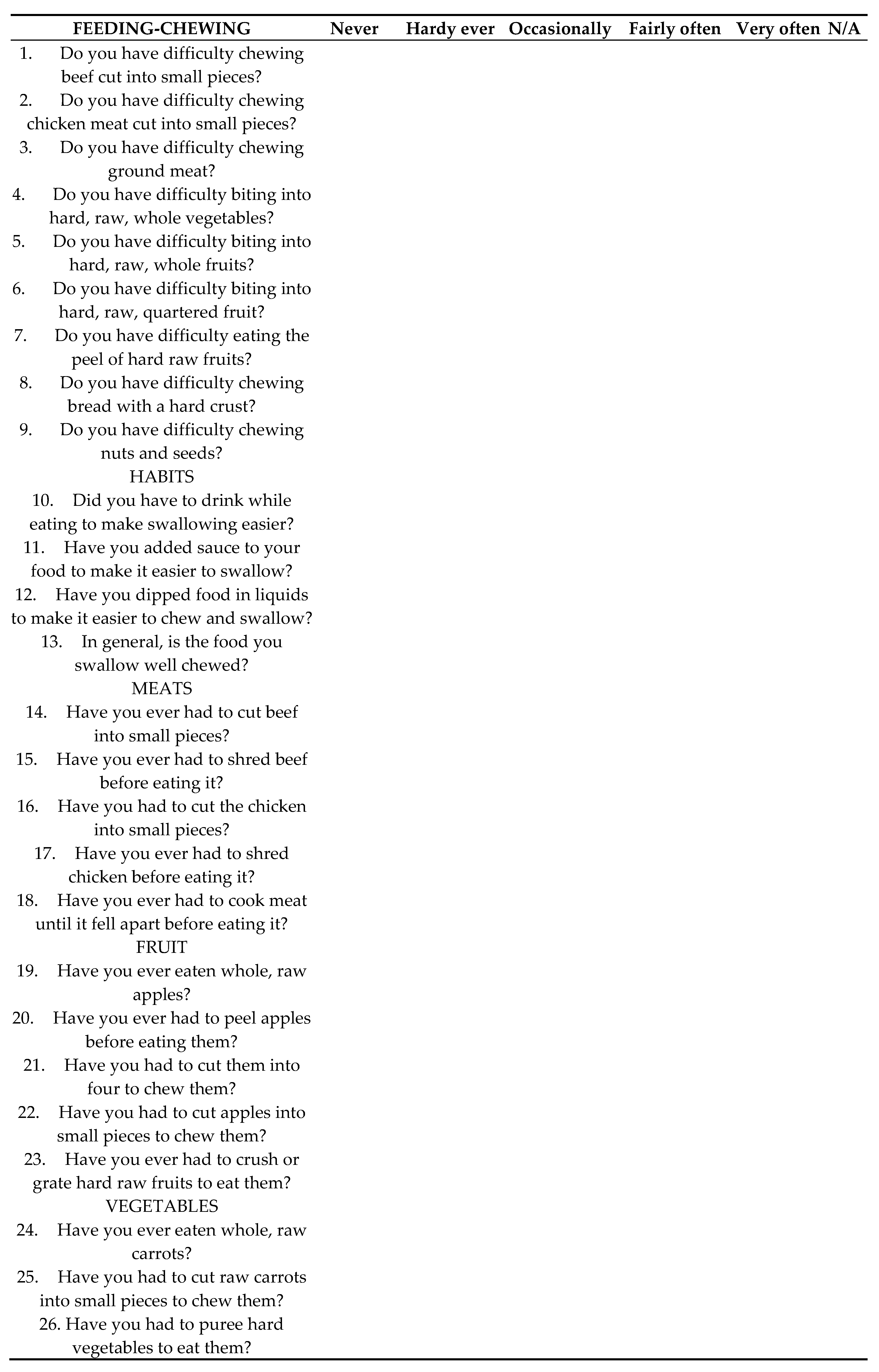

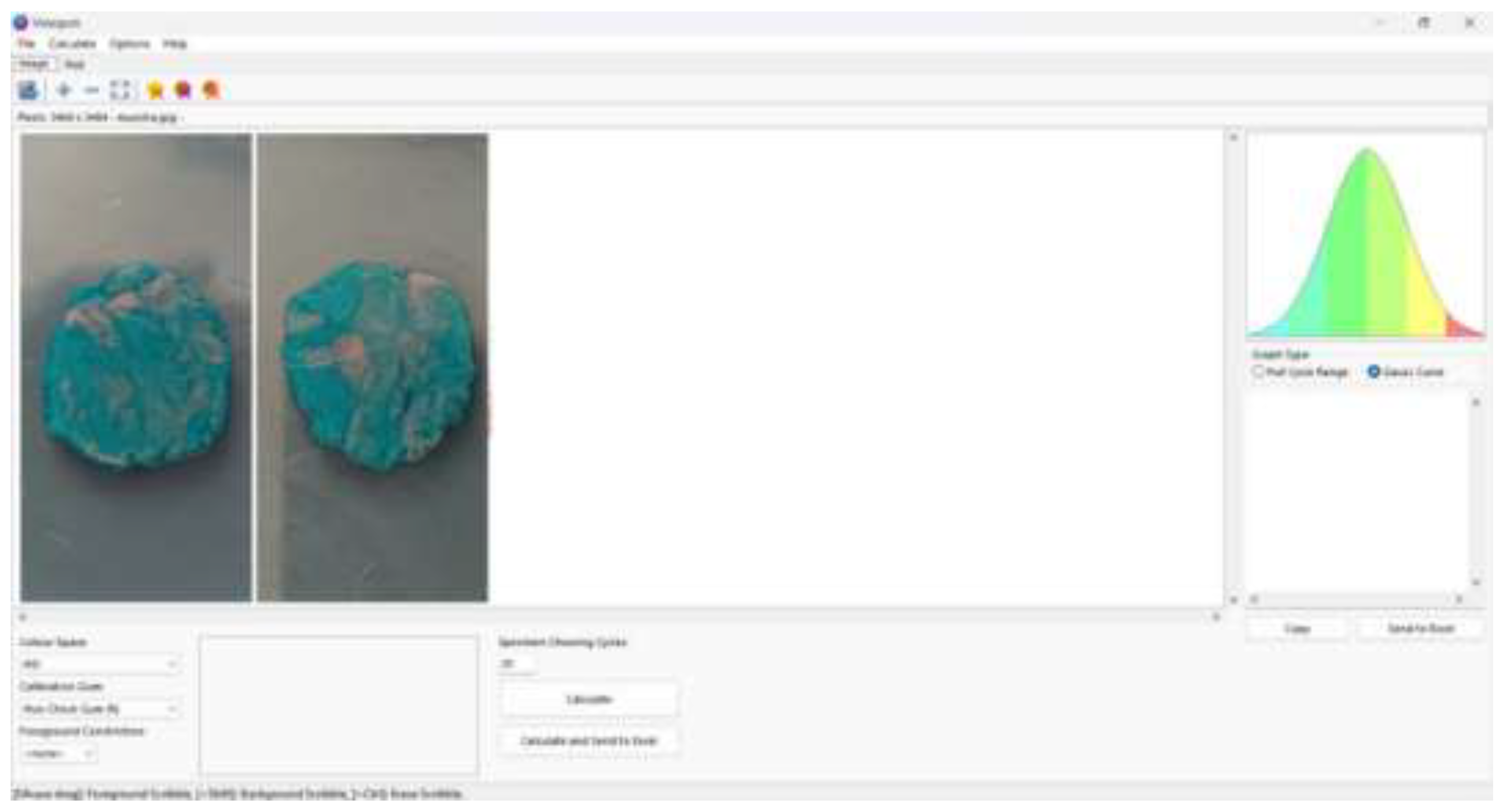

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of the sample before and after periodontal treatment.

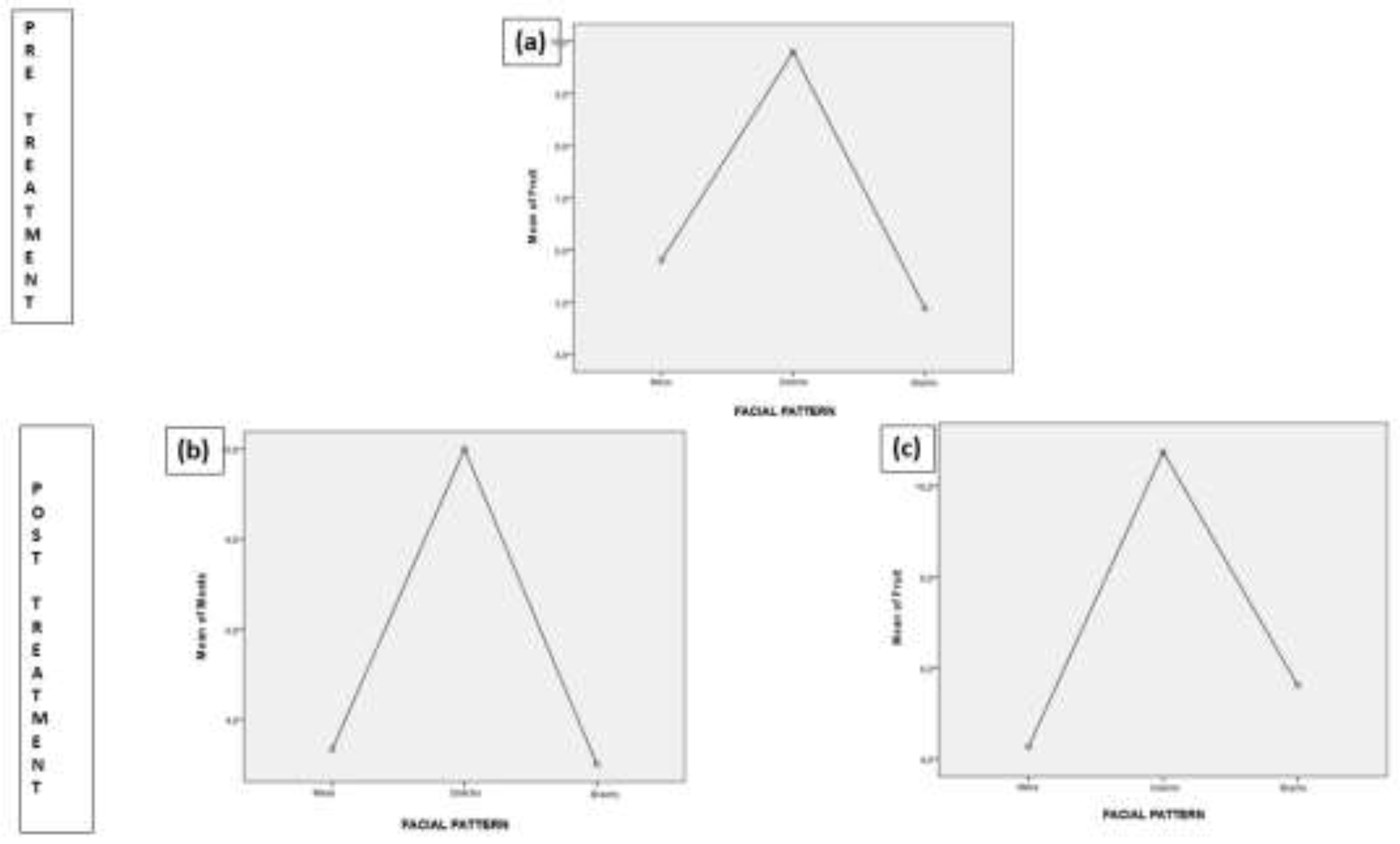

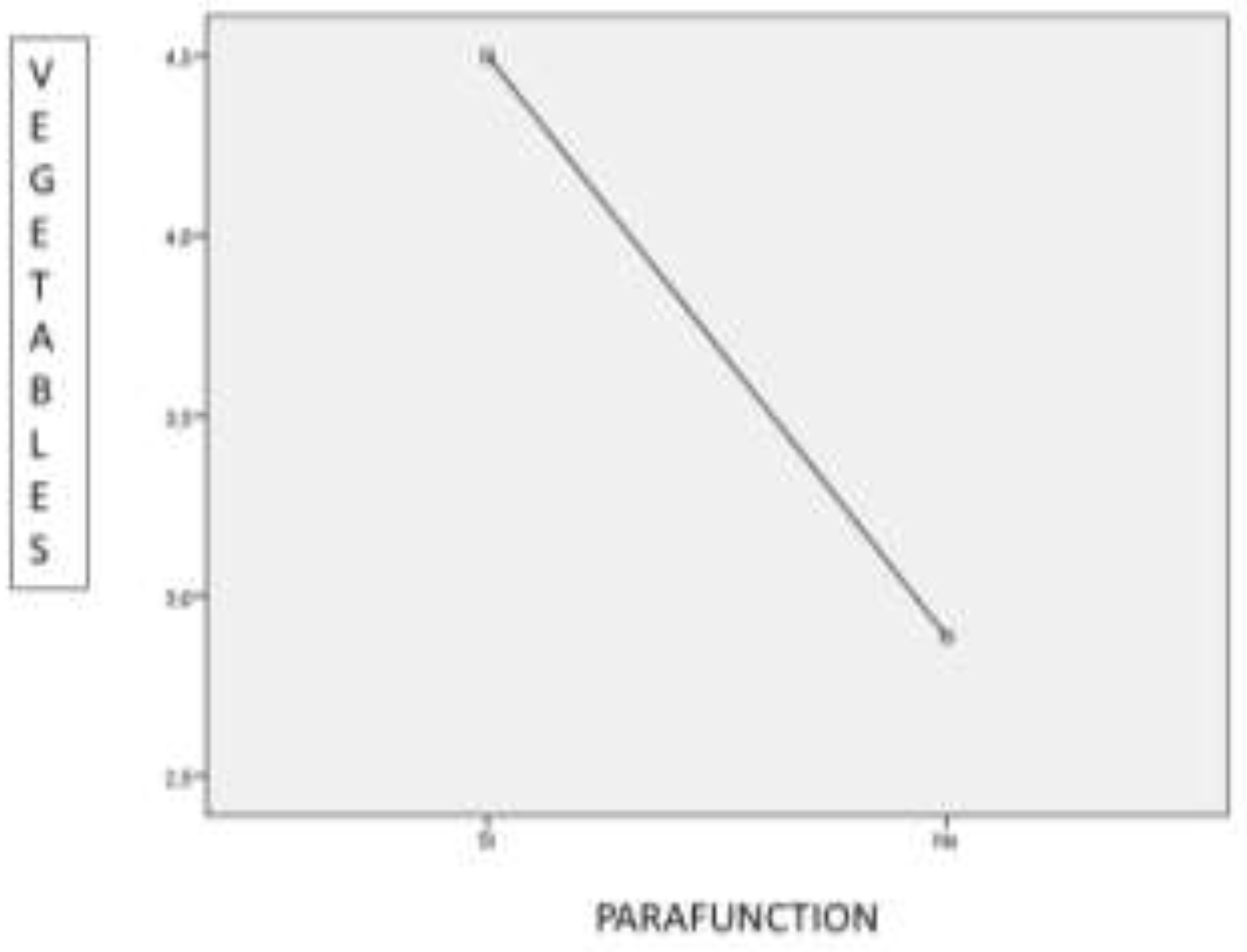

3.2. Behaviour of the variables “gender”, “facial pattern” and “parafunction” in the scores of QMFq and the HueCheck Gum test.

3.3. Correlation between the QMFq and the HueCheck Gum Test.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Caton, J.G.; Armitage, G.; Berglundh, T.; Chapple, I.L.; Jepsen, S.; Kornman, K.S.; Mealey, B.L.; Papapanou, P.N.; Sanz, M.; Tonetti, M.S.; et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions—Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89 (Suppl. 1), S1–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albandar, J.M.; Rams, T.E. Global epidemiology of periodontal diseases: an overview. Periodontology 2000 2002, 29, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, A.S.; Svensson, K.G.; Trulsson, M. Impaired Masticatory Behavior in Subjects With Reduced Periodontal Tissue Support. J. Periodontol. 2006, 77, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, T.d.F.; Regalo, S.C.; Taba, M.; Siéssere, S.; Mestriner, W.; Semprini, M. Changes in Masticatory Performance and Quality of Life in Individuals With Chronic Periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamba, A.K.; Tandon, S.; Faraz, F.; Garg, V.; Aggarwal, K.; Gaba, V. Effect of periodontal disease on electromyographic activity of muscles of mastication: A cross-sectional study. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2020, 47, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, M.; Borges, T.d.F.; Junior, M.T.; Monteiro, S.A.C.; Bottacin, F.S.; Mestriner-Junior, W.; Regalo, I.H.; Siessere, S.; Semprini, M.; Regalo, S.C.H. Alterations in masticatory cycle efficiency and bite force in individuals with periodontitis. Int. J. Health Sci. 2019, 13, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tada, A.; Miura, H. Systematic review of the association of mastication with food and nutrient intake in the independent elderly. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2014, 59, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossioni, A.E. The Association of Poor Oral Health Parameters with Malnutrition in Older Adults: A Review Considering the Potential Implications for Cognitive Impairment. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schott Börger S, Ocaranza Tapia D, Peric Cáceres K, Yévenes López I, Romo Ormazábal F, Schulz Rosales R, et al. Métodos de Evaluación del Rendimiento Masticatorio. Una Revisión. Rev Clínica Periodoncia Implantol Rehabil Oral [Internet]. abril de 2010 [citado 3 de noviembre de 2024];3(1):51-5. Disponible en: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0718539110700422.

- Palomares, T.; Montero, J.; Rosel, E.M.; Del-Castillo, R.; Rosales, J.I. Oral health-related quality of life and masticatory function after conventional prosthetic treatment: A cohort follow-up study. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, L.F.; Thomson, W.; Jokovic, A.; Locker, D. Validation of the Child Perceptions Questionnaire (CPQ11-14). J. Dent. Res. 2005, 84, 649–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, G.H.; Dominguez, B.; Schork, M.; Loesche, W.J. Functional units, chewing, swallowing, and food avoidance among the elderly. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1997, 77, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatch, J.; Shinkai, R.; Sakai, S.; Rugh, J.; Paunovich, E. Determinants of masticatory performance in dentate adults. Arch. Oral Biol. 2001, 46, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, S.; Buschang, P.H.; Throckmorton, G.S.; Palmer, L.; English, J. Masticatory performance and areas of occlusal contact and near contact in subjects with normal occlusion and malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2002, 121, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, T.S.; Tureli, M.C.M.; Gavião, M.B.D. Validity and reliability of the Child Perceptions Questionnaires applied in Brazilian children. BMC Oral Heal. 2009, 9, 13–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz M, Herrera D, Kebschull M, Chapple I, Jepsen S, Berglundh T, et al. Treatment of stage I–III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J Clin Periodontol [Internet]. julio de 2020 [citado 16 de septiembre de 2024];47(Suppl 22):4-60. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7891343/.

- Moya-Villaescusa, M.J.; Sánchez-Pérez, A.; Esparza-Marín, J.; Jornet-García, A.; Montoya-Carralero, J.M. Periodontal Disease and Nonsurgical Periodontal Therapy on the OHRQoL of the Patient: A Pilot Study of Case Series. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buser, R.; Ziltener, V.; Samietz, S.; Fontolliet, M.; Nef, T.; Schimmel, M. Validation of a purpose-built chewing gum and smartphone application to evaluate chewing efficiency. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2018, 45, 845–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, M.; Christou, P.; Herrmann, F.; Müller, F. A two-colour chewing gum test for masticatory efficiency: development of different assessment methods. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2007, 34, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halazonetis, D.J.; Schimmel, M.; Antonarakis, G.S.; Christou, P. Novel software for quantitative evaluation and graphical representation of masticatory efficiency. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2013, 40, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosaka, T.; Ono, T.; Yoshimuta, Y.; Kida, M.; Kikui, M.; Nokubi, T.; Maeda, Y.; Kokubo, Y.; Watanabe, M.; Miyamoto, Y. The effect of periodontal status and occlusal support on masticatory performance: the Suita study. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bilt, A.; van der Glas, H.; Mowlana, F.; Heath, M. A comparison between sieving and optical scanning for the determination of particle size distributions obtained by mastication in man. Arch. Oral Biol. 1993, 38, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmel, M.; Christou, P.; Miyazaki, H.; Halazonetis, D.; Herrmann, F.R.; Müller, F. A novel colourimetric technique to assess chewing function using two-coloured specimens: Validation and application. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 955–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbe, A.G.; Javadian, S.; Rott, T.; Scharfenberg, I.; Deutscher, H.C.D.; Noack, M.J.; Derman, S.H.M. Objective masticatory efficiency and subjective quality of masticatory function among patients with periodontal disease. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.C.; Nogueira, T.E.; Rios, L.F.; Schimmel, M.; Leles, C.R. Reliability of a two-colour chewing gum test to assess masticatory performance in complete denture wearers. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2018, 45, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapur KK, Soman SD. Masticatory performance and efficiency in denture wearers. 1964. J Prosthet Dent. junio de 2006;95(6):407-11.

- Mowlana, F.; Heath, M.; VAN DER Bilt, A.; VAN DER Glas, H. Assessment of chewing efficiency: a comparison of particle size distribution determined using optical scanning and sieving of almonds. J. Oral Rehabilitation 1994, 21, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R.; Furuya, J.; Suzuki, T. Videoendoscopic measurement of food bolus formation for quantitative evaluation of masticatory function. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2011, 55, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, K.; Morais, J.; Feine, J. Nutritional and anthropometric analysis of edentulous patients wearing implant overdentures or conventional dentures. Braz. Dent. J. 2008, 19, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilasaca-Mamani, M.; Barbosa, T.d.S.; Fegadolli, C.; Castelo, P.M. Validity and reliability of the quality of masticatory function questionnaire applied in Brazilian adolescents. CoDAS 2016, 28, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajappa, R.; Batra, M.; Sanadhya, S.; Daryani, H.; Ramesh, G. Oral impacts on daily performance: Validity, reliability and prevalence estimates among Indian adolescents. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 16, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamsson C, Henrikson T, Bondemark L, Ekberg E. Masticatory function in patients with dentofacial deformities before and after orthognathic treatment-a prospective, longitudinal, and controlled study. Eur J Orthod. febrero de 2015;37(1):67-72.

- Pero, A.C.; Scavassin, P.M.; Policastro, V.B.; Júnior, N.M.d.O.; Marin, D.O.M.; da Silva, M.D.D.; Cassiano, A.F.B.; Santana, T.d.S.; Compagnoni, M.A. Masticatory function in complete denture wearers varying degree of mandibular bone resorption and occlusion concept: canine-guided occlusion versus bilateral balanced occlusion in a cross-over trial. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2019, 63, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami S, Mealey BL, Mariotti A, Chapple ILC. Dental plaque-induced gingival conditions. J Periodontol. junio de 2018;89 Suppl 1:S17-27.

- Díaz BF, Pomarino SG. Reevaluación del paciente periodontal: intervalo de tiempo adecuado para reevaluar sus parámetros. Acta Odontológica Colomb [Internet]. 1 de julio de 2017 [citado 3 de noviembre de 2024];7(2):65-71. Disponible en: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actaodontocol/article/view/66373.

- Pereira, L.J.; Gazolla, C.M.; Magalhães, I.B.; Dominguete, M.H.L.; Vilela, G.R.; Castelo, P.M.; Marques, L.S.; Van Der Bilt, A. Influence of periodontal treatment on objective measurement of masticatory performance. J. Oral Sci. 2012, 54, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingervall, B.; Bitsanis, E. A pilot study of the effect of masticatory muscle training on facial growth in long-face children. Eur. J. Orthod. 1987, 9, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, S.G.F.; Custodio, W.; Faot, F.; Cury, A.A.D.B.; Garcia, R.C.M.R. Masticatory features, EMG activity and muscle effort of subjects with different facial patterns. J. Oral Rehabilitation 2010, 37, 813–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulino MR, Moreira VG, Lemos GA, Silva PLP da, Bonan PRF, Batista AUD. Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in college preparatory students: associations with emotional factors, parafunctional habits, and impact on quality of life. Cienc Saude Coletiva. enero de 2018;23(1):173-86.

- Sterenborg, B.A.; Kalaykova, S.I.; Loomans, B.A.; Huysmans, M.-C.D. Impact of tooth wear on masticatory performance. J. Dent. 2018, 76, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable. | Initial (Mean ± SD) | Final (Mean ± SD) | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HI | 30.1466 ± 32.70924 | 13.0962 ± 17.27574 | 0.0001 |

| PD | 2.4594 ± 0.67493 | 1.8806 ± 0.5332 | 0.0001 |

| CAL | 3.2647 ± 1.18767 | 2.505 ± 0.73897 | 0.0001 |

| Total score QMFq | 25.063 ± 18.4355 | 22.625 ± 14.2574 | 0.045 |

| Dependent Variable. | (I) FACIAL PATTERN | (J) FACIAL PATTERN | Mean Difference (I-J) | Standard Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| FRUIT | Dolichofacial | Mesofacial | 4 | 1,9111 | 0,129 | -0,781 | 8,781 |

| Brachyfacial | 4,9176* | 1,9445 | 0,047 | 0,053 | 9,782 | ||

| Dependent Variable | (I) FACIAL PATTERN | (J) FACIAL PATTERN | Mean Difference (I-J) | Standard Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| MEATS | Dolichofacial | Mesofacial | 6,6667 | 2,6298 | 0,051 | -0,015 | 13,349 |

| Brachyfacial | 7,0000* | 2,672 | 0,042 | 0,211 | 13,789 | ||

| FRUITS | Dolichofacial | Mesofacial | 6,4833* | 1,9459 | 0,007 | 1,539 | 11,428 |

| Brachyfacial | 5,1346* | 1,9771 | 0,044 | 0,111 | 10,158 | ||

| ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| VEGETABLES | Between Groups | 12,721 | 1 | 12,721 | 4,329 | 0,046 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).