Submitted:

06 February 2025

Posted:

06 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

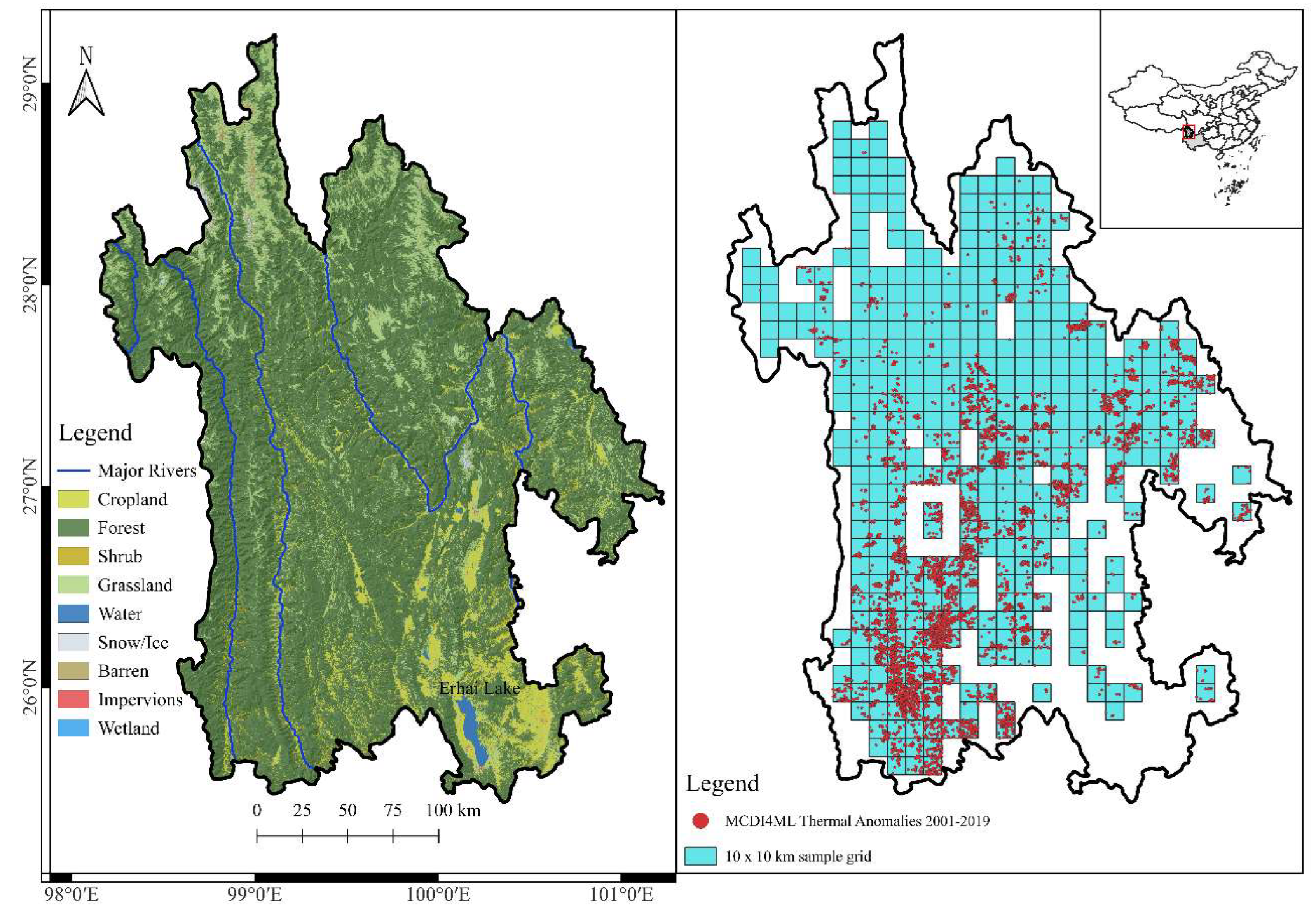

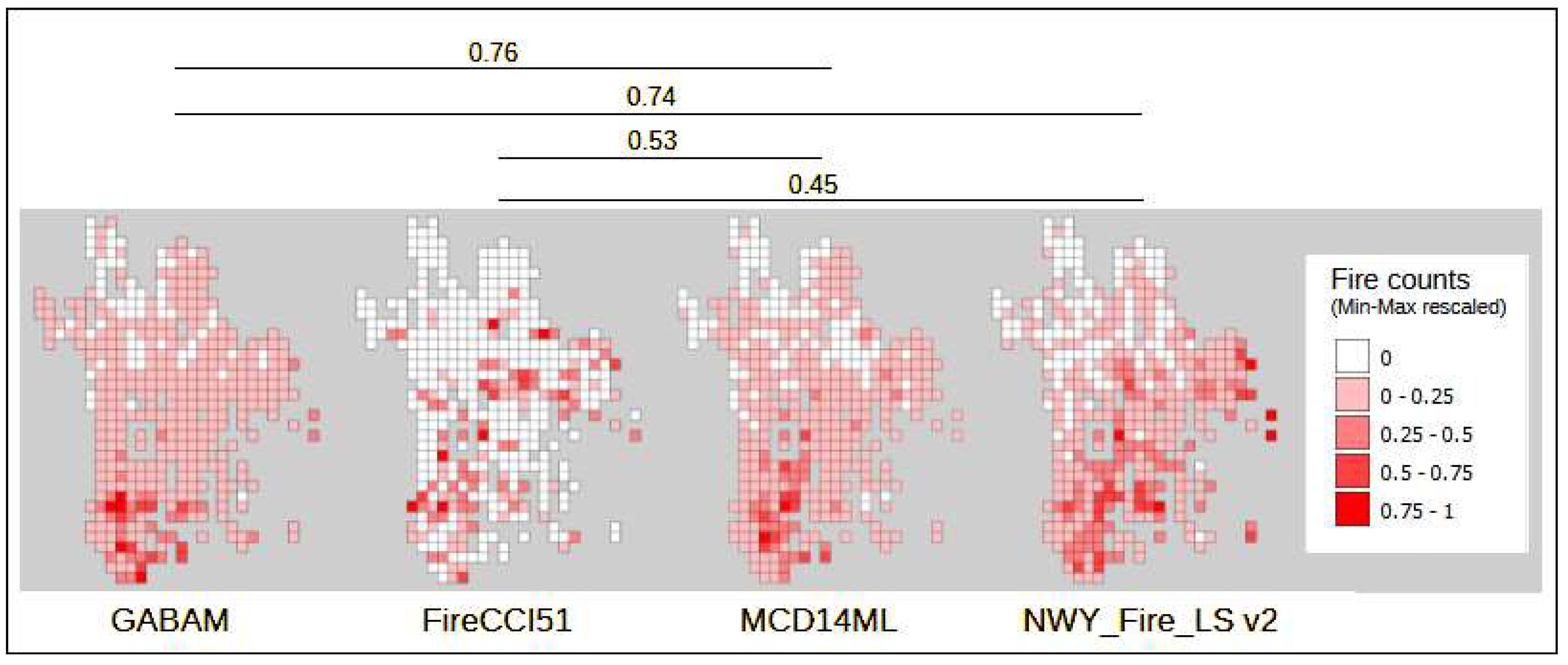

Despite advancements in satellite-derived fire analysis, reconstructing the past remains constrained by historical data limitations. Algorithms for extracting burned area information at the global scale continue to evolve, but complex landscapes and small fires are often excluded, mainly due to sensor spatial resolution. We evaluated the burned area detection capabilities of two recent global products, MODIS FireCCI51 and the Landsat-based GABAM, in a challenging mountainous region over the period 2001-2019. Overall, the spatio-temporal distribution of burn counts within 10 km mesh grid covering the study area correlated well for GABAM (Spearman R: 0.76 and 0.74) and discretely for FireCCI51 (R: 0.53 and 0.45) against two benchmark datasets. Fire event detection performance in the sampled squares in this specific landscape was limited for FireCCI51, despite its reported improvements globally (User’s Accuracy: 0.83, Producer’s Accuracy: 0.08). Conversely, GABAM exhibited relatively strong detection capabilities with reduced commission errors (User’s Accuracy: 0.85, Producer’s Accuracy: 0.68). This evaluation highlights the importance of Landsat-based approaches for global burned area assessments. Landsat's long, consistent time-series and higher spatial resolution offer significant advantages, as reported by the numerous local and regional applications. Yet, its potential for global assessments has been underutilized, hindered by difficulties in handling big amounts of data and the scarcity of analyzable images within a fire year. Nonetheless, the development of GABAM may serve as a proof of concept, demonstrating how the Landsat archive and powerful cloud computing can enhance global burned area mapping, improving accuracy, including small fires, and extending time-series. We encourage researchers to integrate Landsat into global fire extraction routines for comprehensive past fire history reconstruction.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Region

2.2. Dataset Selection and Processing

2.3. Validation Method

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions: The Invaluable Legacy of LANDSAT

- Coarse resolution data has limitations for burned area quantification and other potential applications, such as quantifying greenhouses emissions, due to their substantial underestimation of contributions from small fires.

- Despite several caveats, GABAM can be considered as a proof of concept demonstrating the feasibility of harnessing the Landsat archive to generate significantly improved global burned area assessments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, L.; Du, Z.; Peng, D.; Hao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, P. An overview of the applications of earth observation satellite data: impacts and future trends. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Salas, J.; García, M.; Yebra, M.; Oliva, P. Satellite remote sensing contributions to wildland fire science and management. Curr. For. Reports 2020, 6, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinari, M. L.; Lizundia-Loiola, J.; Khairoun, A.; Roteta, E.; Storm, T.; Boettcher, M.; Danne, O.; Brockmann, C.; Chuvieco, E. Global and continental burned area detection from remote sensing: the FireCCI products. In EGU General Assembly 2023; Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Chuvieco, E.; Mouillot, F.; van der Werf, G. R.; San Miguel, J.; Tanasse, M.; Koutsias, N.; García, M.; Yebra, M.; Padilla, M.; Gitas, I.; Heil, A.; Hawbaker, T. J.; Giglio, L. Historical background and current developments for mapping burned area from satellite Earth observation. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 225, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouillot, F.; Schultz, M. G.; Yue, C.; Cadule, P.; Tansey, K.; Ciais, P.; Chuvieco, E. Ten years of global burned area products from spaceborne remote sensing-A review: Analysis of user needs and recommendations for future developments. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2014, 26, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Velde, I. R.; van der Werf, G. R.; van Wees, D.; Schutgens, N. A. J.; Vernooij, R.; Houweling, S.; Tonucci, E.; Chuvieco, E.; Randerson, J. T.; Frey, M. M.; Borsdorff, T.; Aben, I. Small fires, big impact: evaluating fire emission estimates in southern Africa using new satellite imagery of burned area and carbon monoxide. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wees, D.; van der Werf, G. R.; Randerson, J. T.; Andela, N.; Chen, Y.; Morton, D. C. The role of fire in global forest loss dynamics. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 2377–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randerson, J. T.; Chen, Y.; Van der Werf, G. R.; Rogers, B. M.; Morton, D. C. Global burned area and biomass burning emissions from small fires. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2012, 117, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramo, R.; Roteta, E.; Bistinas, I.; van Wees, D.; Bastarrika, A.; Chuvieco, E.; van der Werf, G. R. African burned area and fire carbon emissions are strongly impacted by small fires undetected by coarse resolution satellite data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Mickley, L. J.; Marlier, M. E.; DeFries, R. S.; Khan, M. F.; Latif, M. T.; Karambelas, A. Diagnosing spatial biases and uncertainties in global fire emissions inventories: Indonesia as regional case study. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairoun, A.; Mouillot, F.; Chen, W.; Ciais, P.; Chuvieco, E. Coarse-resolution burned area datasets severely underestimate fire-related forest loss. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 920, 170599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otón, G.; Lizundia-Loiola, J.; Pettinari, M. L.; Chuvieco, E. Development of a consistent global long-term burned area product (1982–2018) based on AVHRR-LTDR data. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizundia-Loiola, J.; Otón, G.; Ramo, R.; Chuvieco, E. A spatio-temporal active-fire clustering approach for global burned area mapping at 250 m from MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C. M.; Z. Shimbo, J.; Rosa, M. R.; Parente, L. L.; A. Alencar, A.; Rudorff, B. F. T.; Hasenack, H.; Matsumoto, M.; G. Ferreira, L.; Souza-Filho, P. W. M.; de Oliveira, S. W.; Rocha, W. F.; Fonseca, A. V.; Marques, C. B.; Diniz, C. G.; Costa, D.; Monteiro, D.; Rosa, E. R.; Vélez-Martin, E.; Weber, E. J.; Lenti, F. E. B.; Paternost, F. F.; Pareyn, F. G. C.; Siqueira, J. V.; Viera, J. L.; Neto, L. C. F.; Saraiva, M. M.; Sales, M. H.; Salgado, M. P. G.; Vasconcelos, R.; Galano, S.; Mesquita, V. V.; Azevedo, T. Reconstructing three decades of land use and land cover changes in Brazilian biomes with Landsat archive and Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2735. [CrossRef]

- Hawbaker, T. J.; Vanderhoof, M. K.; Schmidt, G. L.; Beal, Y. J.; Picotte, J. J.; Takacs, J. D.; Falgout, J. T.; Dwyer, J. L. The Landsat Burned Area algorithm and products for the conterminous United States. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 244, 111801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidenshink, J.; Schwind, B.; Brewer, K.; Zhu, Z.; Quayle, B.; Howard, S. A project for Monitoring Trends in Burn Severity. Fire Ecol. Spec. Issue 2007, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, T.; Zhang, Z.; He, G.; Jiao, W.; Tang, C. 30 m Resolution global annual burned area mapping based on Landsat images and Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschetti, L.; Roy, D. P.; Hoffmann, A. A.; Humber, M. L. Collection 6 MODIS Burned Area product User’s guide - Version 1.0. User Guid. 2016, Version 1., 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, M.; Stehman, S. V.; Chuvieco, E. Validation of the 2008 MODIS-MCD45 global burned area product using stratified random sampling. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 144, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.; Olofsson, P.; Stehman, S. V.; Tansey, K.; Chuvieco, E. Stratification and sample allocation for reference burned area data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 203, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franquesa, M.; Vanderhoof, M. K.; Stavrakoudis, D. G.; Gitas, I. Z.; Roteta, E.; Padilla, M.; Chuvieco, E. Development of a standard database of reference sites for validating global burned area products. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 3229–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D. M.; Dinerstein, E.; Wikramanayake, E. D.; Burgess, N. D.; Powell, G. V. N.; Underwood, E. C.; D’Amico, J. A.; Itoua, I.; Strand, H. E.; Morrison, J. C.; Loucks, C. J.; Allnutt, T. F.; Ricketts, T. H.; Kura, Y.; Lamoreux, J. F.; Wettengel, W. W.; Hedao, P.; Kassem, K. R. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 2001, 51, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornacca, D.; Ren, G.; Xiao, W. Small fires, frequent clouds, rugged terrain and no training data: A methodology to reconstruct fire history in complex landscapes. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderbauer, S.; Zebisch, M.; Steurer, C. Applied Remote Sensing in Mountain Regions: A Workshop Organized by EURAC in the Core of the Alps. Mt. Res. Dev. 2007, 27, 286–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D. J.; Walsh, S. J. Remote Sensing of Mountain Environments. Geogr. Compass 2009, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, E.; Buytaert, W.; Peaver, L.; Wheater, H. Evaluation of precipitation products over complex mountainous terrain: A water resources perspective. Adv. Water Resour. 2011, 34, 1222–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C. Q.; Ohsawa, M. Ecology of subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests of Yunnan, southwestern China as compared to those of southwestern Japan. J. Plant Res. 2009, 122, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C. Q. The subtropical vegetation of southwestern China: Plant distribution, diversity and ecology; Plant and Vegetation; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2015; ISBN 978-94-017-9740-5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Long, T.; He, G.; Wei, M.; Tang, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.; She, W.; Zhang, X. Study on global burned forest areas based on landsat data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sensing 2020, 86, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J. G.; Su, W.; Luo, C.; Shen, Z. A shrubby resprouting pine with serotinous cones endemic to southwest China. Ecology 2021, 102, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Luo, X.; Liang, P.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Sun, H.; Pan, K.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Pang, X. Fire from policy, human interventions, or biophysical factors? Temporal–spatial patterns of forest fire in southwestern China. For. Ecol. Manage. 2020, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornacca, D.; Ren, G.; Xiao, W. Performance of Three MODIS Fire Products (MCD45A1, MCD64A1, MCD14ML), and ESA Fire_CCI in a Mountainous Area of Northwest Yunnan, China, Characterized by Frequent Small Fires. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Liao, A.; Cao, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, X.; He, C.; Han, G.; Peng, S.; Lu, M.; Zhang, W.; Tong, X.; Mills, J. Global land cover mapping at 30 m resolution: A POK-based operational approach. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2015, 103, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESA Land Cover CCI Product User Guide Version 2. Tech. Rep. 2017.

- Giglio, L.; Schroeder, W.; Justice, C. O. The collection 6 MODIS active fire detection algorithm and fire products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2016, 178, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katagis, T.; Gitas, I. Z. Assessing the accuracy of MODIS MCD64A1 C6 and FireCCI51 burned area products in Mediterranean ecosystems. Remote Sens. 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessôa, A. C. M.; Anderson, L. O.; Carvalho, N. S.; Campanharo, W. A.; Silva Junior, C. H. L.; Rosan, T. M.; Reis, J. B. C.; Pereira, F. R. S.; Assis, M.; Jacon, A. D.; Ometto, J. P.; Shimabukuro, Y. E.; Silva, C. V. J.; Pontes-Lopes, A.; Morello, T. F.; Aragão, L. E. O. C. Intercomparison of burned area products and its implication for carbon emission stimations in the Amazon. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornacca, D.; Ren, G.; Xiao, W. Evaluating the best spectral indices for the detection of burn scars at several post-fire dates in a mountainous region of northwest Yunnan, China. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; He, Y.; Tong, A. Evaluation of spectral indices for estimating burn severity in semiarid grasslands. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2016, 25, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubkova, M.; Lötter, M.; Bronkhorst, F.; Giglio, L. Assessment of the effectiveness of coarse resolution fire products in monitoring long-term changes in fire regime within protected areas in South Africa. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2024, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Long, T.; He, G.; Wei, M.; Tang, C.; Wang, W.; Wang, G.; She, W.; Zhang, X. Study on global burned forest areas based on landsat data. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sensing 2020, 86, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| FireCCI51 | GABAM | ||||||||||||

| Year |

Low - high threshold |

High frequency sample squares |

Reference fires |

TP | FN | FP | PA | UA | TP | FN | FP | PA | UA |

| 2001 | 2 | 23 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 6 | 2 | 5 | 0.75 | 0.55 |

| 2002 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| 2003 | 3 | 20 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0.08 | 1 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 0.54 | 0.64 |

| 2004 | 4 | 26 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0.8 | 0.73 |

| 2005 | 4 | 17 | 18 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2 | 16 | 0 | 0.11 | 1 |

| 2006 | 7 | 39 | 18 | 3 | 15 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.75 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 0.78 | 0.93 |

| 2007 | 6 | 34 | 15 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 14 | 1 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.93 |

| 2008 | 3 | 16 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 9 | 2 | 4 | 0.82 | 0.69 |

| 2009 | 6 | 41 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0.25 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0.88 | 1 |

| 2010 | 10 | 43 | 18 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0.06 | 1 | 14 | 4 | 0 | 0.78 | 1 |

| 2011 | 4 | 11 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0.9 | 1 |

| 2014 | 30 | 86 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.86 | 11 | 3 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| 2015 | 4 | 24 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.67 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| 2016 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0.71 | 1 |

| 2017 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 6 | 6 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.75 |

| 2018 | 2 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0.22 | 1 |

| 2019 | 3 | 14 | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | NaN | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0.67 | 1 |

| Overall study period | 198 | 15 | 183 | 3 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 135 | 63 | 23 | 0.68 | 0.85 | ||

|

BA < 25 ha (n = 41) |

BA 25-100 ha (n = 71) |

BA > 100 ha (n = 86) |

||||

| TP | PA | TP | PA | TP | PA | |

| GABAM | 26 | 0.63 | 42 | 0.59 | 67 | 0.78 |

| FireCCI51 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.06 | 11 | 0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).