Submitted:

07 February 2025

Posted:

07 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

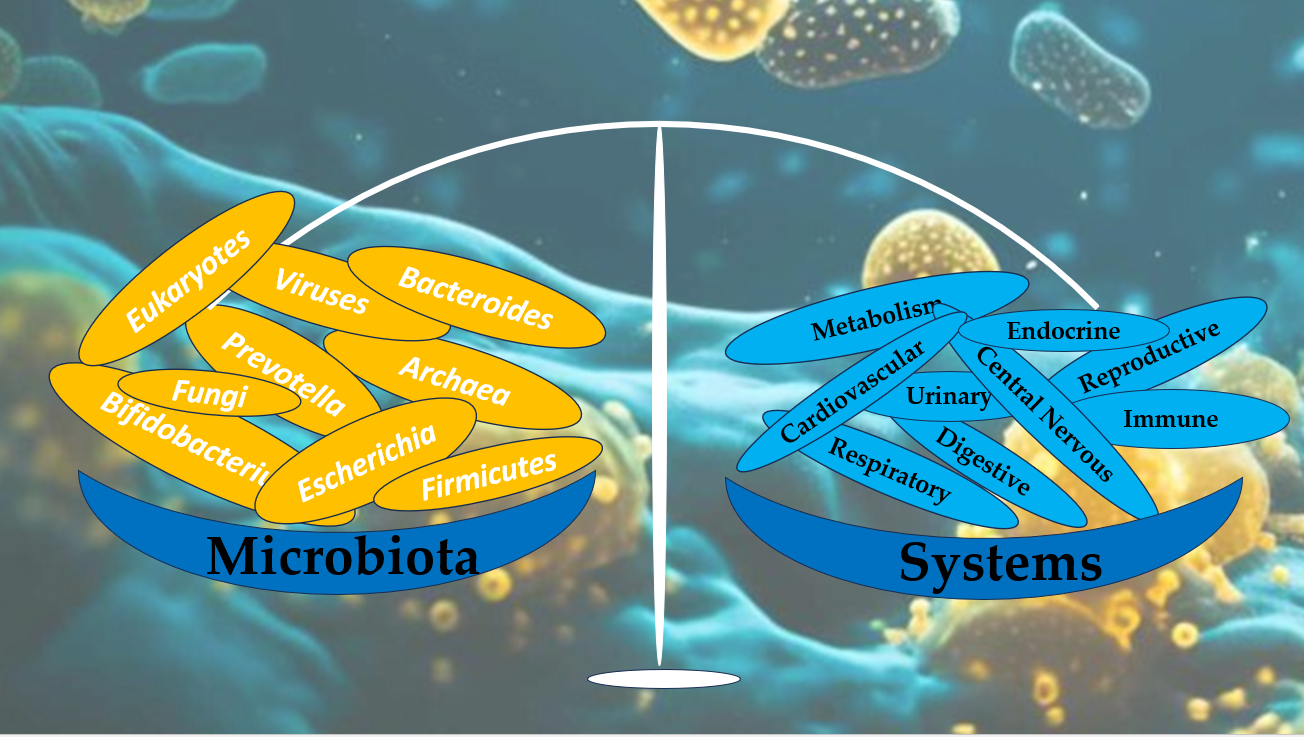

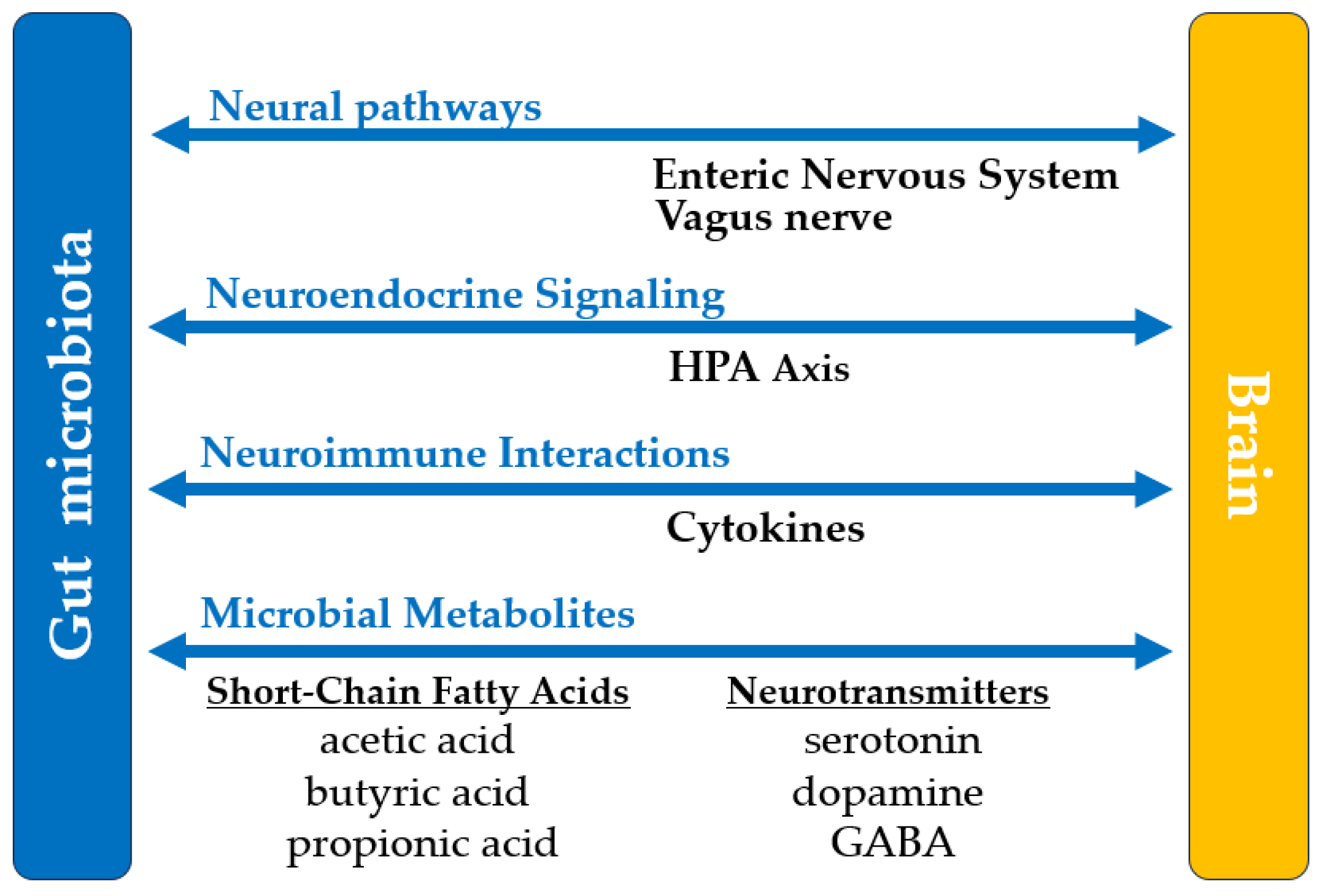

The human microbiota, consisting of trillions of microorganisms in various organ systems, plays a pivotal role in maintaining health and preventing disease. Recent research underscores the signif-icance of gut microbiome in processes such as metabolism, immune regulation, and neuroprotection. Methods: This review explores the multi-system impact of microbiota, emphasizing its roles in human health and its involvement in conditions affecting the digestive, immune, integumentary, respiratory, urinary, reproductive, and nervous systems. We synthesized findings from recent studies, including observational research, clinical trials, and meta-analyses, focusing on key areas such as the gut-brain axis, short-chain fatty acid metabolism, immune modulation, and microbial diversity across organ systems. Results: Our findings reveal that microbiota composition influences systemic health by enhancing gut barrier function, regulating immune homeostasis, and synthe-sizing essential nutrients. Dysbiosis is implicated in metabolic disorders, autoimmune diseases, or neurological conditions, including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Conclusions: Microbiota is a cornerstone of human health, with essential roles in maintaining physiological balance and mit-igating disease risk. Therapeutic interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation show promise for restoring microbial equilibrium and treating various conditions. However, further research is needed to elucidate specific mechanisms and optimize microbio-ta-based therapies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

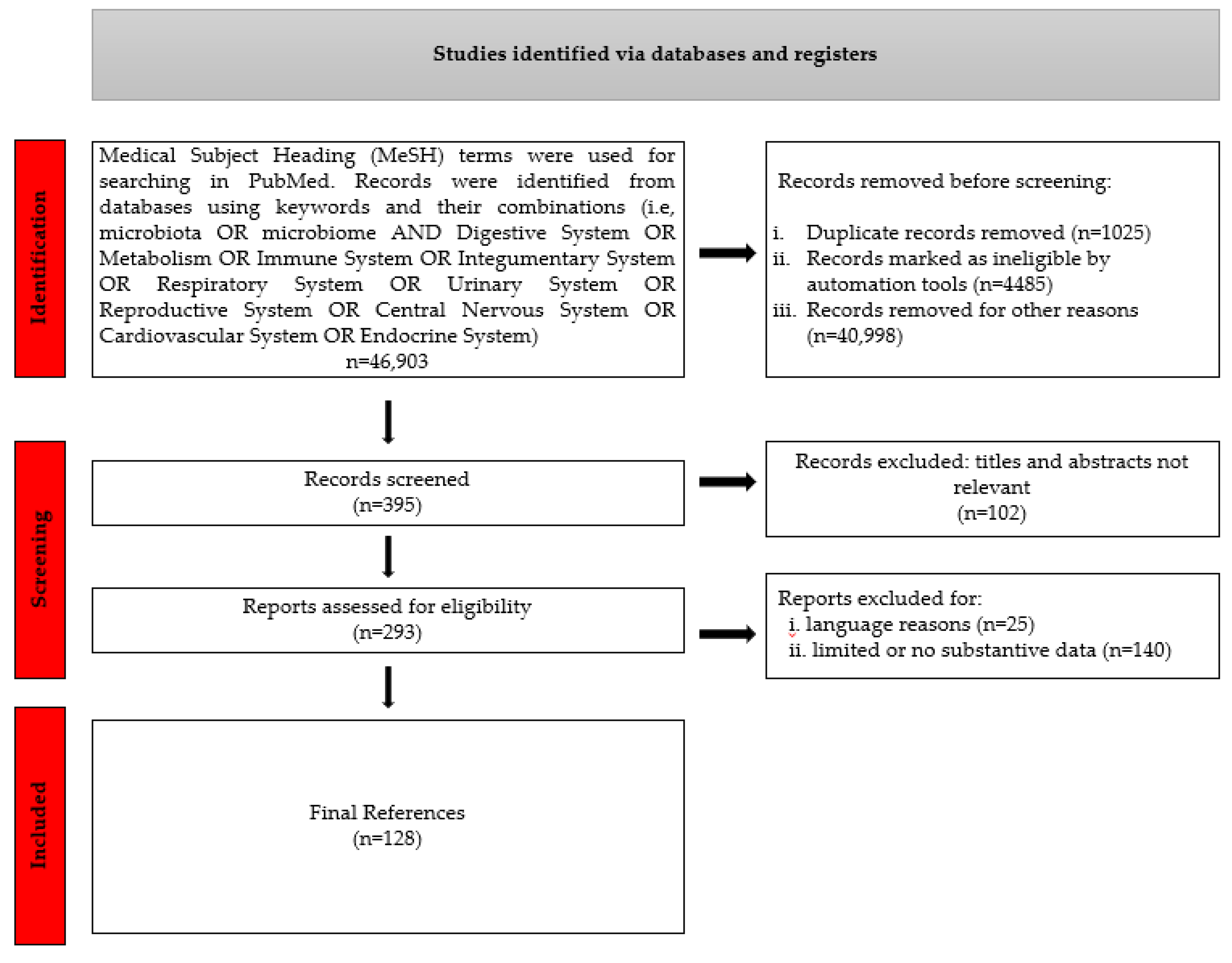

2. Materials and Methods

3. The Multisystem Impact of Microbiota.

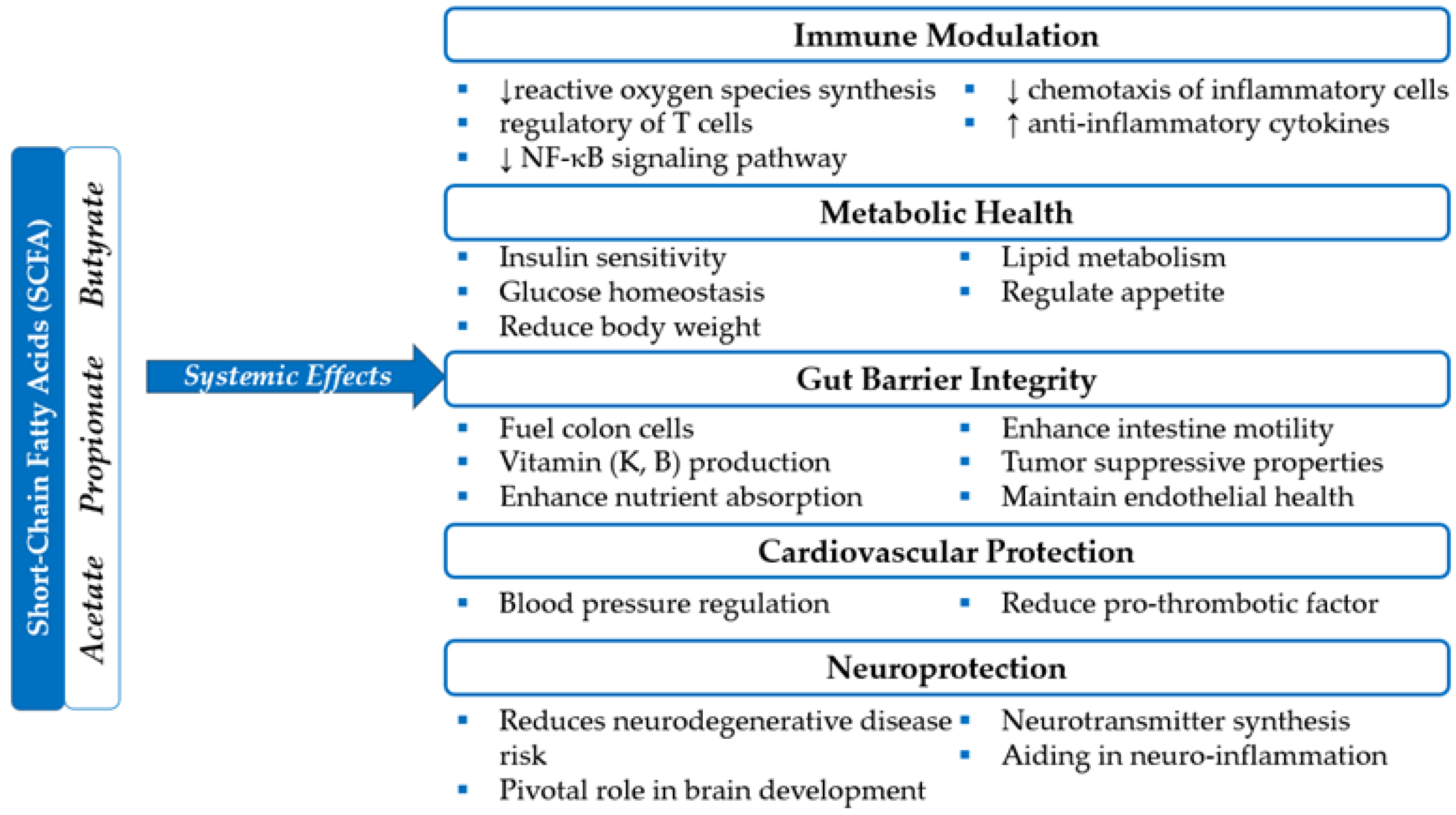

3.1. Digestive System And Metabolism

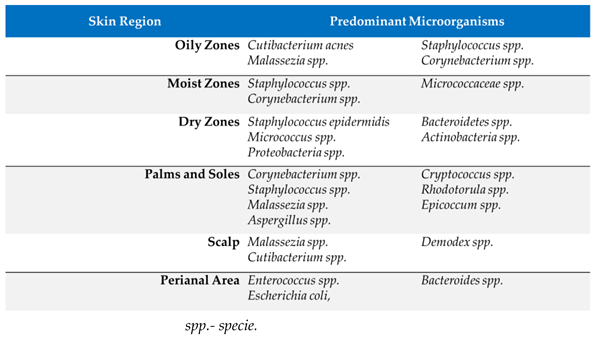

3.2. Integumentary System

|

3.3 Respiratory System

3.4 Urinary and Reproductive Systems

3.5 Central Nervous System

3.6 Cardiovascular System

3.7. Endocrine Function

3.8. Immune System

3.9. Microbiota - A New Frontier in Diagnosis and Treatment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shanahan, F.; Ghosh, T.S.; O'Toole, P.W. The Healthy Microbiome—What Is the Definition of a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 483–494. [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.; Aleya, L.; Kamel, M. Microbiota's Role in Health and Diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 36967–36983. [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Duffy, A. Factors Influencing the Gut Microbiota, Inflammation, and Type 2 Diabetes. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1468S–1475S. [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human Gut Microbiota/Microbiome in Health and Diseases: A Review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113, 2019–2040. [CrossRef]

- Man, W.H.; de Steenhuijsen Piters, W.A.; Bogaert, D. The Microbiota of the Respiratory Tract: Gatekeeper to Respiratory Health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 259–270. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, X. Gut Microbiota and Bone Metabolism. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21740. [CrossRef]

- Portincasa, P.; Bonfrate, L.; Vacca, M.; De Angelis, M.; Farella, I.; Lanza, E.; Khalil, M.; Wang, D.Q.; Sperandio, M.; Di Ciaula, A. Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1105. [CrossRef]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Nageshwar Reddy, D. Role of the Normal Gut Microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 8787–8803. [CrossRef]

- James, K.R.; Gomes, T.; Elmentaite, R.; Kumar, N.; Gulliver, E.L.; King, H.W.; Stares, M.D.; Bareham, B.R.; Ferdinand, J.R.; Petrova, V.N.; et al. Distinct Microbial and Immune Niches of the Human Colon. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 343–353. [CrossRef]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [CrossRef]

- Fusco, W.; Lorenzo, M.B.; Cintoni, M.; Porcari, S.; Rinninella, E.; Kaitsas, F.; Lener, E.; Mele, M.C.; Gasbarrini, A.; Collado, M.C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty-Acid-Producing Bacteria: Key Components of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, K.; El Abbar, F.; Dobranowski, P.; Manoogian, J.; Butcher, J.; Figeys, D.; Mack, D.; Stintzi, A. Butyrate’s role in human health and the current progress towards its clinical application to treat gastrointestinal disease. Clinical Nutrition 2023, 42, 61-75. [CrossRef]

- Louis, P.; Hold, G.L.; Flint, H.J. The Gut Microbiota, Bacterial Metabolites, and Colorectal Cancer. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 661–672. [CrossRef]

- Patrick, S. A tale of two habitats: Bacteroides fragilis, a lethal pathogen and resident in the human gastrointestinal microbiome. Microbiology 2022, 168. [CrossRef]

- Coletto, E.; Latousakis, D.; Pontifex, M.G.; Crost, E.H.; Vaux, L.; Perez Santamarina, E.; Goldson, A.; Brion, A.; Hajihosseini, M.K.; Vauzour, D.; et al. The role of the mucin-glycan foraging Ruminococcus gnavus in the communication between the gut and the brain. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2073784. [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.L.; Patterson, A.D. The Gut Microbiome: An Orchestrator of Xenobiotic Metabolism. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, A.; Kleiner, M. Dietary protein and the intestinal microbiota: An understudied relationship. iScience 2022, 25, 105313. [CrossRef]

- Tarracchini, C.; Lugli Gabriele, A.; Mancabelli, L.; van Sinderen, D.; Turroni, F.; Ventura, M.; Milani, C. Exploring the vitamin biosynthesis landscape of the human gut microbiota. mSystems 2024, 9, e00929-00924. [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Covián, D.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Margolles, A.; Gueimonde, M.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Salazar, N. Intestinal Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Their Link with Diet and Human Health. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 185. [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J.M.; Kang, D.J.; Hylemon, P.B. Bile salt biotransformations by human intestinal bacteria. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 47, 241–259. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sánchez, A.; Fuentes-Pananá, E.M. Human Viruses and Cancer. Viruses 2014, 6, 4048–4049.

- Brown, E.M.; Clardy, J.; Xavier, R.J. Gut microbiome lipid metabolism and its impact on host physiology. Cell Host & Microbe 2023, 31, 173-186. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Chiang, J.Y.L. Bile acid signaling in metabolic disease and drug therapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 948–983. [CrossRef]

- Arora, T.; Vanslette, A.M.; Hjorth, S.A.; Bäckhed, F. Microbial regulation of enteroendocrine cells. Med 2021, 2, 553-570. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sun, B.; Yu, D.; Zhu, C. Gut Microbiota: An Important Player in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 834485. [CrossRef]

- DeGruttola, A.K.; Low, D.; Mizoguchi, A.; Mizoguchi, E. Current Understanding of Dysbiosis in Disease in Human and Animal Models. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016, 22, 1137-1150. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, Q.; Qiu, H.; Ma, Y.; Hou, N.; Zhang, J.; Kan, C.; Han, F.; Sun, X.; Shi, J. The complex link between the gut microbiome and obesity-associated metabolic disorders: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37609. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimzadeh Leylabadlo, H.; Sanaie, S.; Sadeghpour Heravi, F.; Ahmadian, Z.; Ghotaslou, R. From role of gut microbiota to microbial-based therapies in type 2-diabetes. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 81, 104268. [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, J.L.; Bäckhed, F. Diet–microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 2016, 535, 56–64. [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, T.P.M.; Rampanelli, E.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Vallance, B.A.; Verchere, C.B.; van Raalte, D.H.; Herrema, H. Gut Microbiota as a Trigger for Metabolic Inflammation in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 571731. [CrossRef]

- Gebrayel, P.; Nicco, C.; Al Khodor, S.; Bilinski, J.; Caselli, E.; Comelli, E.M.; Egert, M.; Giaroni, C.; Karpinski, T.M.; Loniewski, I.; et al. Microbiota medicine: towards clinical revolution. J Transl Med 2022, 20, 111. [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.R.; Merenstein, D.J.; Pot, B.; Calder, P.C. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [CrossRef]

- Drwiega, E.N.; Nascimento, D.C. A Comparison of Currently Available and Investigational Fecal Microbiota Transplant Products for Recurrent Clostridioides difficile Infection. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 436. [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Cruz, S.; Orozco-Covarrubias, L.; Sáez-de-Ocariz, M. The Human Skin Microbiome in Selected Cutaneous Diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 834135. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Qu, L.; Mijakovic, I.; Wei, Y. Advances in the human skin microbiota and its roles in cutaneous diseases. Microbial Cell Factories 2022, 21, 176. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Byrd, A.L.; Park, M.; Kong, H.H.; Segre, J.A. Temporal Stability of the Human Skin Microbiome. Cell 2016, 165, 854–866. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Lin, G.; Ferenczi, K. The skin microbiome and the gut-skin axis. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 39, 829–839. [CrossRef]

- Kengmo Tchoupa, A.; Kretschmer, D.; Schittek, B.; Peschel, A. The epidermal lipid barrier in microbiome-skin interaction. Trends Microbiol 2023, 31, 723-734. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, M. Skin Barrier Function and the Microbiome. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Swaney, M.H.; Nelsen, A.; Sandstrom, S.; Kalan, L.R. Sweat and Sebum Preferences of the Human Skin Microbiota. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e0418022. [CrossRef]

- Smythe, P.; Wilkinson, H.N. The Skin Microbiome: Current Landscape and Future Opportunities. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Lunjani, N.; Ahearn-Ford, S.; Dube, F.S.; Hlela, C.; O’Mahony, L. Mechanisms of microbe-immune system dialogue within the skin. Genes & Immunity 2021, 22, 276-288. [CrossRef]

- Ying, S.; Zeng, D.N.; Chi, L.; Tan, Y.; Galzote, C.; Cardona, C.; Lax, S.; Gilbert, J.; Quan, Z.X. The Influence of Age and Gender on Skin-Associated Microbial Communities in Urban and Rural Human Populations. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0141842. [CrossRef]

- Boxberger, M.; Cenizo, V.; Cassir, N.; La Scola, B. Challenges in exploring and manipulating the human skin microbiome. Microbiome 2021, 9, 125. [CrossRef]

- Leung, M.H.Y.; Tong, X.; Lee, P.K.H. Indoor Microbiome and Airborne Pathogens. Comprehensive Biotechnology 2019, 31, 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Hayleeyesus, S.F.; Manaye, A.M. Microbiological quality of indoor air in university libraries. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2014, 4 Suppl 1, S312–S317.

- Flowers, L.; Grice, E.A. The Skin Microbiota: Balancing Risk and Reward. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 190-200. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, R.L. S. epidermidis influence on host immunity: more than skin deep. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 143-144. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, G.J.; Brüggemann, H. Bacterial skin commensals and their role as host guardians. Benef. Microbes 2014, 5, 201–215. [CrossRef]

- Severn, M.M.; Horswill, A.R. Staphylococcus epidermidis and its dual lifestyle in skin health and infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 97-111. [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, A.; Totino, V.; Cacciotti, F.; Iebba, V.; Neroni, B.; Bonfiglio, G.; Trancassini, M.; Passariello, C.; Pantanella, F.; Schippa, S. Rebuilding the Gut Microbiota Ecosystem. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018, 15. [CrossRef]

- Rozas, M.; Hart de Ruijter, A.; Fabrega, M.J.; Zorgani, A.; Guell, M.; Paetzold, B.; Brillet, F. From Dysbiosis to Healthy Skin: Major Contributions of Cutibacterium acnes to Skin Homeostasis. Microorganisms 2021, 9. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.E.; Fischbach, M.A.; Belkaid, Y. Skin microbiota-host interactions. Nature 2018, 553, 427-436. [CrossRef]

- Casciaro, B.; Loffredo, M.R.; Cappiello, F.; Verrusio, W.; Corleto, V.D.; Mangoni, M.L. Frog Skin-Derived Peptides Against Corynebacterium jeikeium: Correlation between Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activities. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics9080448 Grice, E.A.; Dawson, T.L.J. Host-microbe interactions: Malassezia and human skin. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 40, 81–87 . [CrossRef]

- Kanna, B.V.; Latha, R.; Kavitha, K.; Jeyakumari, D. Phenotypic Characterization of Malassezia spp. Isolated from Healthy Individuals. Res. J. Biotech. 2023, 18, 74–78. [CrossRef]

- Schmid, B.; Künstner, A.; Fähnrich, A.; Busch, H.; Glatz, M.; Bosshard, P.P. Longitudinal Characterization of the Fungal Skin Microbiota in Healthy Subjects Over a Period of 1 Year. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2022, 142, 2766-2772.e2768. [CrossRef]

- Silling, S.; Kreuter, A.; Gambichler, T.; Meyer, T.; Stockfleth, E.; Wieland, U. Epidemiology of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus Infection and Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 6176. [CrossRef]

- Harper, A.; Vijayakumar, V.; Ouwehand, A.C.; ter Haar, J.; Obis, D.; Espadaler, J.; Binda, S.; Desiraju, S.; Day, R. Viral Infections, the Microbiome, and Probiotics. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 10, 596166. [CrossRef]

- Willmott, T.; Campbell, P.M.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; O'Connor, C.; Bell, M.; Watson, R.E.B.; McBain, A.J.; Langton, A.K. Behaviour and sun exposure in holidaymakers alters skin microbiota composition and diversity. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1217635. [CrossRef]

- Grant, G.J.; Kohli, I.; Mohammad, T.F. A Narrative Review of the Impact of Ultraviolet Radiation and Sunscreen on the Skin Microbiome. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2024, 40, e12943. [CrossRef]

- Marrella, V.; Nicchiotti, F.; Cassani, B. Microbiota and immunity during respiratory infections: Lung and gut affair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4051. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhou, X. Lung microbiome: New insights into the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Fabbrizzi, A.; Amedei, A.; Lavorini, F.; Renda, T.; Fontana, G. The Lung Microbiome: Clinical and Therapeutic Implications. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2019, 14, 1241–1250. [CrossRef]

- Natalini, J.G.; Singh, S.; Segal, L.N. The dynamic lung microbiome in health and disease. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 21, 222-235. [CrossRef]

- Sommariva, M.; Le Noci, V.; Bianchi, F.; Camelliti, S.; Balsari, A.; Tagliabue, E.; Sfondrini, L. The lung microbiota: Role in maintaining pulmonary immune homeostasis and its implications in cancer development and therapy. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2739–2749. [CrossRef]

- Santacroce, L.; Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A.; Inchingolo, F.; Luperto, P.; De Nitto, E.; Topi, S. The Human Respiratory System and its Microbiome at a Glimpse. Biology 2020, 9, 318. [CrossRef]

- Prinzi, A. Normal respiratory microbiota in health and disease. Available online: https://asm.org/Articles/2020/February/Normal-Respiratory-Microbiota-in-Health-and-Diseas (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Wu, B.G.; Segal, L.N. Lung microbiota and its impact on the mucosal immune phenotype. Microbiol. Spectrum 2017, 5. [CrossRef]

- Whiteside, S.A.; McGinniss, J.E.; Collman, R.G. The Lung Microbiome: Progress and promise. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, T.; Ye, C.; Zhong, J.; Huang, J.-D.; Ke, Y.; Sun, H. The Lung Microbiome: A new frontier for lung and brain disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2170. [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Escribano-Vazquez, U.; Descamps, D.; Cherbuy, C.; Langella, P.; Riffault, S.; Remot, A.; Thomas, M. Paradigms of lung microbiota functions in health and disease, particularly in asthma. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Hérivaux, A.; Willis, J.R.; Mercier, T.; Lagrou, K.; Gonçalves, S.M.; Gonçales, R.A.; Maertens, J.; Carvalho, A.; Gabaldón, T.; Cunha, C. Lung microbiota predict invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and its outcome in immunocompromised patients. Thorax 2021, 77, 283–291. [CrossRef]

- Yagi, K.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Lukacs, N.W.; Asai, N. The Lung Microbiome during Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10872. [CrossRef]

- Huffnagle, G.B.; Dickson, R.P.; Lukacs, N.W. The Respiratory Tract Microbiome and Lung Inflammation: A Two-Way Street. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 299–306. [CrossRef]

- Dickson, R.P.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Martinez, F.J.; Huffnagle, G.B. The Microbiome and the Respiratory Tract. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2016, 78, 481–504. [CrossRef]

- Budden, K.F.; Gellatly, S.L.; Wood, D.L.; Cooper, M.A.; Morrison, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; Hansbro, P.M. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut–lung axis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 15, 55–63. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.D.; Barnett, C.; Sulaiman, I.A. A clinicians’ review of the respiratory microbiome. Breathe 2022, 18, 210161. [CrossRef]

- King, A. Exploring the lung microbiome’s role in disease. Nature 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ruane, D.; Chorny, A.; Lee, H.; Faith, J.; Pandey, G.; Shan, M.; Simchoni, N.; Rahman, A.; Garg, A.; Weinstein, E.G.; Oropallo, M.; Gaylord, M.; Ungaro, R.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Alexandropoulos, K.; Cerutti, A.; Mehandru, S.; Mucida, D.; Merad, M. Microbiota Regulate the Ability of Lung Dendritic Cells to Induce IgA Class-Switch Recombination and Generate Protective Gastrointestinal Immune Responses. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 53–73. [CrossRef]

- Khatiwada, S.; Subedi, A. Lung microbiome and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Possible link and implications. Human Microbiome Journal 2020, 17, 100073. [CrossRef]

- Mayo Clinic: The Gut-Lung Axis. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/pulmonary-medicine/news/the-gut-lung-axis-intestinal-microbiota-and-inflammatory-lung-disease/mqc-20483394 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Enaud, R.; Prevel, R.; Ciarlo, E.; Beaufils, F.; Wieërs, G.; Guery, B.; Delhaes, L. The gut-lung axis in health and respiratory diseases: A place for Inter-organ and inter-kingdom crosstalks. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10. [CrossRef]

- Dang, A.T.; Marsland, B.J. Microbes, metabolites, and the gut–lung axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12, 843–850. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S.; Mohanty, S.; Sharma, S.; Tripathi, P. Possible Role of Gut Microbes and Host’s Immune Response in Gut–Lung Homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 954339. [CrossRef]

- Perez-Carrasco, V.; Soriano-Lerma, A.; Soriano, M.; Gutiérrez-Fernández, J.; Garcia-Salcedo, J.A. Urinary Microbiome: Yin and Yang of the Urinary Tract. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 617002. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.M.; et al. The female urinary microbiome: A comparison of women with and without urgency urinary incontinence. mBio 2014, 5(4), e01283-14. [CrossRef]

- Robino, L.; Sauto, R.; Morales, C.; Navarro, N.; González, M.J.; Cruz, E.; Neffa, F.; Zeballos, J.; Scavone, P. Presence of intracellular bacterial communities in uroepithelial cells, a potential reservoir in symptomatic and non-symptomatic people. BMC Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, 590. [CrossRef]

- Modena, B.D.; et al. Changes in Urinary Microbiome Populations Correlate in Kidney Transplants With Interstitial Fibrosis and Tubular Atrophy Documented in Early Surveillance Biopsies. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 712–723. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M.M.; Hilt, E.E.; Rosenfeld, A.B.; Zilliox, M.J.; Thomas-White, K.; Fok, C.; Kliethermes, S.; Schreckenberger, P.C.; Brubaker, L.; Gai, X.; Wolfe, A.J. The Female Urinary Microbiome: A Comparison of Women with and without Urgency Urinary Incontinence. mBio 2014, 5, e01283-14.

- Onywera, H.; Williamson, A.-L.; Ponomarenko, J.; Meiring, T.L. The Penile Microbiota in Uncircumcised and Circumcised Men: Relationships With HIV and Human Papillomavirus Infections and Cervicovaginal Microbiota. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 383. [CrossRef]

- Gottschick, C.; Deng, Z.L.; Vital, M.; et al. The urinary microbiota of men and women and its changes in women during bacterial vaginosis and antibiotic treatment. Microbiome 2017, 5, 99. [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.L.; Fettweis, J.M.; Eaves, L.J.; Silberg, J.L.; Neale, M.C.; Serrano, M.G.; Jimenez, N.R.; Prom-Wormley, E.; Girerd, P.H.; Borzelleca, J.F.; et al. Vaginal microbiome Lactobacillus crispatus is heritable among European American women. Communications Biology 2021, 4, 872. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, H.G.; Groah, S.L.; Pérez-Losada, M.; Ljungberg, I.; Sprague, B.M.; Chandal, N.; Caldovic, L.; Hsieh, M. The Urine Microbiome of Healthy Men and Women Differs by Urine Collection Method. Int Neurourol J 2020, 24, 41-51. [CrossRef]

- Ng, Q.X.; Peters, C.; Venkatanarayanan, N.; Goh, Y.Y.; Ho, C.Y.X.; Yeo, W.-S. Use of Lactobacillus spp. to prevent recurrent urinary tract infections in females. Medical Hypotheses 2018, 114, 49-54. [CrossRef]

- Ghartey, J.P.; et al. Lactobacillus crispatus dominant vaginal microbiome is associated with inhibitory activity of female genital tract secretions against Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96659. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Si, S.; Huang, L.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y. Vaginal flora during pregnancy and subsequent risk of preterm birth or prelabor rupture of membranes: a nested case–control study from China. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2023, 23, 244. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.-H.; et al. Urogenital tract and rectal microbiota composition and its influence on reproductive outcomes in infertile patients. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1051437. [CrossRef]

- Souza, S.V.; Monteiro, P.B.; Moura, G.A.; Santos, N.O.; Fontanezi, C.T.B.; Gomes, I.A.; Teixeira, C.A. Vaginal microbioma and the presence of Lactobacillus spp. as interferences in female fertility: A review system. JBRA Assist Reprod 2023, 27, 496-506. [CrossRef]

- Morais, L.H.; Schreiber, H.L.; Mazmanian, S.K. The gut microbiota–brain axis in behaviour and brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 241–255. [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson's disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358. [CrossRef]

- Doroszkiewicz, J.; Groblewska, M.; Mroczko, B. The Role of Gut Microbiota and Gut–Brain Interplay in Selected Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10028. [CrossRef]

- Cekanaviciute, E.; et al. Gut bacteria from multiple sclerosis patients modulate human T cells and exacerbate symptoms in mouse models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 10713–10718. [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.J.; et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation therapy for Parkinson's disease: A preliminary study. Medicine 2020, 99, e22035. [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Asemi, Z.; Daneshvar Kakhaki, R.; Bahmani, F.; Kouchaki, E.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Taghizadeh, M. Effect of Probiotic Supplementation on Cognitive Function and Metabolic Status in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 256. [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; et al. Gut microbiota modulation: Another way to treat neurological diseases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 149, 181–197. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, C.; et al. Gut microbiota in Parkinson's disease: Preclinical and clinical evidence. Transl. Res. 2018, 204, 17–30. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Microbiota Implications in Endocrine-Related Diseases: From Development to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 221. [CrossRef]

- Lymperopoulos, A.; Suster, M.S.; Borges, J.I. Short-Chain Fatty Acid Receptors and Cardiovascular Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3303. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zong, B.; Ji, L.; Sun, P.; Jia, D.; Wang, R. Free Fatty Acids and Free Fatty Acid Receptors: Role in Regulating Arterial Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7853. [CrossRef]

- Robles-Vera, I.; Toral, M.; de la Visitación, N.; Aguilera-Sánchez, N.; Redondo, J.M.; Duarte, J. Protective Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids on Endothelial Dysfunction Induced by Angiotensin II. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 277. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Wilcox, J.; Webb, A.J.; O’Gallagher, K. Dysfunctional and Dysregulated Nitric Oxide Synthases in Cardiovascular Disease: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 15200.

- Shanmugham, M.; Bellanger, S.; Leo, C.H. Gut-Derived Metabolite, Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in Cardio-Metabolic Diseases: Detection, Mechanism, and Potential Therapeutics. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 504. [CrossRef]

- Nesci, A.; Carnuccio, C.; Ruggieri, V.; D’Alessandro, A.; Di Giorgio, A.; Santoro, L.; Gasbarrini, A.; Santoliquido, A.; Ponziani, F.R. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence on the Metabolic and Inflammatory Background of a Complex Relationship. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9087. [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, M.; Borràs, C.; Rotllan, N.; Tondo, M.; Escolà-Gil, J.C.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO: A Causal Factor Promoting Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1940. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hu, J. Unraveling the gut microbiota's role in salt-sensitive hypertension: current evidences and future directions. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024, 11, 1410623. [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, C.B.; Gabe, M.B.N.; Svendsen, B.; Dragsted, L.O.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Holst, J.J. The impact of short-chain fatty acids on GLP-1 and PYY secretion from the isolated perfused rat colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2018, 315, G53-g65. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meng, X.; Ma, Z.; Sun, Z.; Wang, Z. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Nutrient Intake, Ghrelin, and Adiponectin Concentrations in Diabetic Hemodialysis Patients. Altern Ther Health Med 2023, 29, 36-42.

- Hamamah, S.; Hajnal, A.; Covasa, M. Influence of Bariatric Surgery on Gut Microbiota Composition and Its Implication on Brain and Peripheral Targets. Nutrients 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- Canyelles, M.; Borràs, C.; Rotllan, N.; Tondo, M.; Escolà-Gil, J.C.; Blanco-Vaca, F. Gut Microbiota-Derived TMAO: A Causal Factor Promoting Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1940. [CrossRef]

- Rusch, J.A.; Layden, B.T.; Dugas, L.R. Signalling cognition: The gut microbiota and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1130689. [CrossRef]

- Vagnerová, K.; Vodička, M.; Hermanová, P.; Ergang, P.; Šrůtková, D.; Klusoňová, P.; Balounová, K.; Hudcovic, T.; Pácha, J. Interactions between gut microbiota and acute restraint stress in peripheral structures of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis and the intestine of male mice. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2655. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chen, D.; Zhao, C.; Jiang, L.; Mao, S.; Song, C.; Gao, F. Decreased abundance of Akkermansia after adrenocorticotropic hormone therapy in patients with West syndrome. BMC Microbiology 2021, 21, 126. [CrossRef]

- Shulhai, A.-M.; Rotondo, R.; Petraroli, M.; Patianna, V.; Predieri, B.; Iughetti, L.; Esposito, S.; Street, M.E. The Role of Nutrition on Thyroid Function. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2496. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Ding, Q.; Zhang, W.; Kang, M.; Ma, J.; Zhao, L. Gut microbial beta-glucuronidase: a vital regulator in female estrogen metabolism. Gut Microbes 2023, 15(1), 2156157. [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, J. The role of gut microbial β-glucuronidase in estrogen reactivation and breast cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 631552. [CrossRef]

- Choden, T.; Cohen, N.A. The gut microbiome and the immune system. Exploration of Medicine 2022, 3, 219-233. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Research 2020, 30, 492-506. [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Wang, X.; Fang, Z.; Li, L.; Wu, C.; Bi, D.; Li, N.; Chen, Q.; Qin, H. Fecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice: Present controversies and future prospects. hLife 2024, 2, 269-283. [CrossRef]

| System | Microbiota-system relationship |

|

1. Digestive System |

|

|

2. Integumentary System |

|

|

3. Respiratory System |

|

|

4. Urinary System |

|

|

5. Reproductive System |

|

| 6. Central Nervous System |

|

| 7. Cardiovascular System |

|

| 8. Endocrine System |

|

|

9. Immune system |

|

| System | Relevant Microorganisms | Products/Biomarkers |

| 1. Digestive System |

|

|

| 2. Integumentary System |

|

|

| 3. Respiratory System |

|

|

| 4. Urinary and Reproductive System |

|

|

| 5. Central Nervous System |

|

|

| 6. Cardiovascular System |

|

|

| 7. Endocrine System |

|

|

| 8.Immune System |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).